- 1Department of Mathematics and Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 2Department of Mathematics, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

- 3Department of Mathematics, College of Science, Qassim University, Buraidah, Saudi Arabia

- 4Department of Industrial Engineering, OSTIM Technical University, Ankara, Türkiye

- 5Saveetha School of Engineering, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, SIMATS, Chennai, India

- 6Faculty of Data Science and Information Technology, INTI International University, Nilai, Malaysia

Introduction: This article highlights the applications of artificial intelligence in the flood dynamics analysis with its effects on the ecosystem with the help of mathematical modeling and simulations.

Problem Statement: Flood prediction with control remains critical for all walks of lives. Due to nonlinear hydrological mechanism and delayed responses within natural systems, the integer-order models often fail to capture memory effects.

Results: A FF-Flood dynamical system is developed with five variables to capture the dynamics of flood more precisely. The theoretical results of the model ensure the existence of solution, uniqueness of solution, and stability analysis. Ecosystem disruption is inferred through dynamic water level changes, surface runoff and water contamination.

Methodology: A novel FF-Flood dynamical system is constructed which is integrating the surface storage, runoff, river flow, water level and flood area. Existence and boundedness are analytically verified with reference of fixed-point theory, and time-domain simulations demonstrate sensitivity patterns. The results are affirmed by the help of AI deep learning analysis: as process innovation.

1 Introduction

Climate change is a critical environmental complex challenge of the 21st century which is disrupting ecosystems, altering weather dynamics, and transforming human-environment interactions across the globe (Trenberth, 2014; Yang et al., 2014; Gazi et al., 2025). One of the most prominent outcomes of climate change is its disruptive impact on the natural hydrological system, leading to changes in rainfall systems, temperature rise, and an enhancement in extreme events like flooding. The hydrological system, which manages the natural exchange of water between the atmosphere, land, and underground sources, is increasingly disrupted by floods. Enhanced evaporation rates, irregular rainfall distribution, and unpredictable surface runoff and groundwater have magnified the frequency and severity of floods, damaging drainage networks and disturbing the ecological systems and human infrastructure (Wu et al., 2012; Nan et al., 2011; Barry et al., 2025). These climatic disruption have been induced by several sources. The consistent rise in global temperatures due to greenhouse gas emissions has triggered profound disruptions in the Earth’s climate system. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that the average global temperature has increased by approximately

In the context of flooding, warmer air can retain greater moisture, significantly increasing the probability of heavy rainfall and storm-driven floods. Research indicates a consistent 2% rise per decade in annual precipitation across mid-latitude regions since the 1950s. Such patterns have resulted in devastating flood events-for instance, the catastrophic 2021 floods in Germany and Belgium, which inflicted over 40 billion in damages. Conversely, some regions face persistent water scarcity due to reduced snowpack, such as the southwestern United States, where the 2020–2022 megadrought marked the driest period in over a millennium (Janni et al., 2024; Ripple et al., 2024; Van Daalen et al., 2024).

These climatic changes place severe stress on water systems, agriculture, and disaster preparedness, amplifying the risks to human population and ecosystems together. The intersection of severe precipitation and outdated urban infrastructure often leads to overwhelmed drainage systems, urban floods, and loss of life and property. Addressing the threat of flood disasters necessitates urgent climate action-namely reducing emissions, enhancing resilient infrastructure, and implementing adaptive water governance. Sustained collaboration between scientists, policymakers, and communities is important to mitigating future impacts and ensuring resilience against worsening hydrological disruptions (Cai et al., 2024; Su and Ullah, 2024; Yaseen et al., 2024).

Floods are natural phenomenon that occur when water levels exceed the normal limits of rivers, lakes, or other water-bodies. The basic causes are including; heavy rainfall, rapid snowmelt, or dams failures. These events create a dynamic system where the balance between water volume, velocity, and the environment transfers dramatically (Wang et al., 2024; Rogers et al., 2025). The floods play dual role on ecosystems they are destructive for some regions while beneficial for others. On one hand, floods can disrupt habitats, affect wildlife, and cause soil erosion, causing to long-term biodiversity loss. On the other hand, floods also play a role in nutrient cycling by restructuring sediments and organic material, which can enhance soil fertility and improve the growth of plant species. The flood dynamic system is, therefore, a complex interaction between the natural forces and the resilience of the ecosystems it affects, highlighting the complex mechanism between environmental factors and the dependent organisms (Sun et al., 2024; Clarke et al., 2023; Badawy et al., 2024).

Floods are complex hydrological phenomenon influenced by a range of interacting natural and anthropogenic variables. Intense and/or prolonged rainfall, rapid snowmelt, topographic variations, and saturated soil factors often serve as basic natural flood resources (Salhi et al., 2024; Hamed et al., 2024; Darvishi Boloorani et al., 2024). Human activities such as urbanization, deforestation, and inadequate drainage mechanisms further implies flood risks by disrupting the natural flow and absorption of water. In flood dynamical systems, nonlinear feedback mechanisms between rainfall, runoff, river discharge, and land use jointly shape the intensity and duration of flooding dynaimcs (Gabr, 2023; Gebrael et al., 2024).

The repercussions of floods are far-reaching, extending beyond immediate property destruction. Financially, they cause significant costs on infrastructure repair, emergency response, and long-term economic recovery (Jonkman et al., 2024). Ecologically, floods can alter habitats, contaminate water, and lead to the transmission or death of wildlife. Prolonged overflow can also disrupt nutrient cycles and degrade agricultural land, dominating to food insecurity (Van Houtven, 2024; Terry et al., 2023). Therefore, the study of flood dynamical systems is important for developing predictive models and sustainability procedures to mitigate these downstream effects.

The Figure 1, highlights the floods and their financial and ecological impacts on Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. The evolution of flood-related financial and ecological impacts in Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco from 2015 to 2022. Financial losses are in million USD, showing a consistent growth in the graph in all countries. The Egypt is experiencing the most critical rise. Ecological loss, shown by a dimensionless index, also increases steadily, describing mounting environmental stress linked to recurrent flooding. Tunisia and Morocco have shown lower but gradually increasing impacts, whereas Algeria maintains a more moderate dynamics. This graph shows the growing effects of floods on both economic infrastructure and ecosystems across the MENA region, highlighting the need for significant flood management strategies (Gabr, 2023; Gebrael et al., 2024; Jonkman et al., 2024; Van Houtven, 2024; Terry et al., 2023; Kurniawan et al., 2024).

Figure 1. Subfigures present statistical data for the years 2015–2022: (a) financial impacts of floods (in million USD) and (b) ecological effects indices for Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco between 2015 and 2022.

1.1 Fractional order modeling of dynamical systems

Fractional differential equations (FDEs) suggest a pivotal extension of classical calculus. These are used to model systems with memory and hereditary aspects which make them more suitable for resilient real-world problems. In applied scientific field, FDEs have been successfully applied to viscoelastic materials, fluid dynamics, control theory, and biological problems. They capture anomalous diffusion and long-range temporal habits more precise than integer-order systems (Sabatier et al., 2007; Herrmann, 2011). Their viability gives accurate representations of dynamic intricate systems, especially where classical models are not well applicable (Caputo and Fabrizio, 2015; Bas et al., 2019). In the recent works, the readers can see a bridging role of FDEs between theoretical analysis and computational results in the works (Khan et al., 2025a; Khan et al., 2025b; Ahmad et al., 2024).

By incorporating fractal geometry into the idea of fractional derivatives, the fractal-fractional derivative is an expansion of the traditional fractional calculus. It simulates systems with long-range dependencies and irregular non-differentiable activities, which are prevalent of complex and natural phenomena. Fractal-fractional derivatives, in comparison to integer-order derivatives, are durable to capture anomalous diffusion and memory problems (Atangana, 2017; Atangana and Qureshi, 2019; Atangana and Araz, 2020). Due to these properties, they are applied in fields such as epidemiology for modeling of disease transmission including sophisticated time-dependent relationships. Additionally, they are used in biology, physics, and finance to explain phenomena like as anomalous diffusion, diffusion in porous media, and chaotic system behaviors, providing more realistic and realistic representations of dynamics in the real world. For more detail about the applications and usefulness of the fractional derivatives and their applications in the environmental sciences, we refer the readers to the works (Sekerci, 2020; Kha et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2021) and the references therein.

Definition 1.1. Assume that

Definition 1.2. Assume that

In the onward expressions, we will use

1.2 AI applications in science

Artificial Intelligence (AI) plays a vital role in analyzing systems by offering advanced techniques for modeling, forecasting, and optimization. In scenarios where system variables change over time, such as in dynamic environments, AI techniques including machine learning and neural networks efficiently handles at managing intricate and nonlinear patterns that conventional statistical methods often try to capture (Kumar and Mani, 1994; Böttcher et al., 2022). Artificial Intelligence (AI) plays a pivotal role in uncovering patterns from large datasets, capturing dynamical behaviors, and developing real-time forecasts. Techniques such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models are extensively applied for analyzing time-series data and anomalies recognitions. Additionally, AI contributes to solving inverse problems by finding system parameters from observed data. These methods also support automated model selection, parameter tuning, and error analysis, thereby enhancing the precision of dynamic simulations. Consequently, AI-driven approaches are increasingly adopted in domains like climate analysis, economic prediction, and engineering systems, where modeling complex and evolving phenomena is essential (Yuksel, 2024; Sharma et al., 2025; Khan et al., 2025c; Khan et al., 2025d).

1.2.1 FF-mathematical modeling of flood dynamical system

The dynamics of the presumed model is based on the excessive rainfall aiding to the flood demonstrated in the Figure 2. The excessive rainfall is raising to the water level in the rivers which are causing to the soil erosion and disrupting the natural water cycle which in severe cases causing to the floods. In this work, we assume the following as models’ variables; surface storage

Figure 2. Excessive rain fall raising to the water levels in rivers causing to the runoff of land structures and resulting to the floods and catastrophic situations.

Let

where

Each term models physical processes relevant to flood behavior:

1.4 Novelty statement

2 Mathematical analysis of the model

With the help of fixed point procedure, we check the existence of FF-Flood model (1.1). For this, we apply the FF-integral on the system (1.1) and get

For simplicity in Equation 2.1, we define kernels

The following assumption is critical for the qualitative analysis of the model (1.1).

Theorem 2.1. The Lipchitz conditions are fulfilled by all the kernals

Proof. To check the Lipschitz criteria for the kernel

where

Theorem 2.2. Assume that

Theorem 2.3. With the assertion

Theorem 2.4. With the assertion

Theorem 2.5. With the assumption of condition

Note: The proof of these theorems are omitted for the reason that the article is mainly focused on the artificial intelligence and computational results for the FF-flood dynamical system (1.1). For those readers who are interested in the mathematical proof of these results are referred to the works in (Khan et al., 2025a; Khan et al., 2025b; Ahmad et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2022).

3 Computational scheme

The computational scheme for the deep learning of FF-water cycle model (1.1) is described in this section. We start considering:

Taking help of the Riemann-Integral, we have

Taking the place of

Using two-step Lagrange Polynomial to integrate (3.3), we get

With the use of Equations 3.1–3.3, the following computational mechanism Equation 3.4 is developed:

In the Figure 3, the flood dynamical system (1.1) is analyzed for the effects analysis of the surface storage depletion rates

Figure 3. The river flow dynamics and surface runoff under the effects of the variation in the surface storage depletion rate of the FF-flood dynamical system (1.1) for the FF-orders 0.98. (a) The impact of surface storage depletion rate f2 over the river flow dynamics Qr of the FF-flood dynamical system (1.1). (b) The impact of surface storage depletion rate f2 over the surface runoff Qs of the FF-flood dynamical system (1.1).

3.1 Explanation of figures with correct soil moisture interpretation

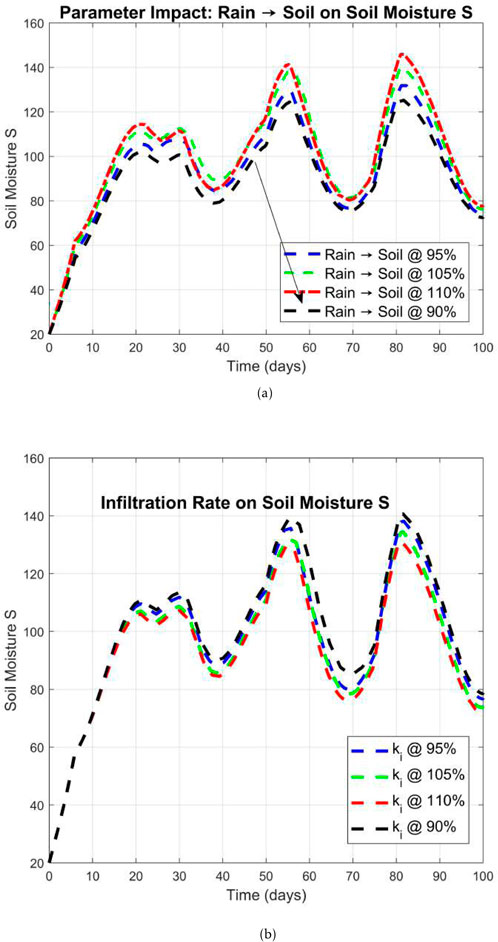

The Figure 4 shows the variation of soil moisture

Figure 4. Soil moisturization

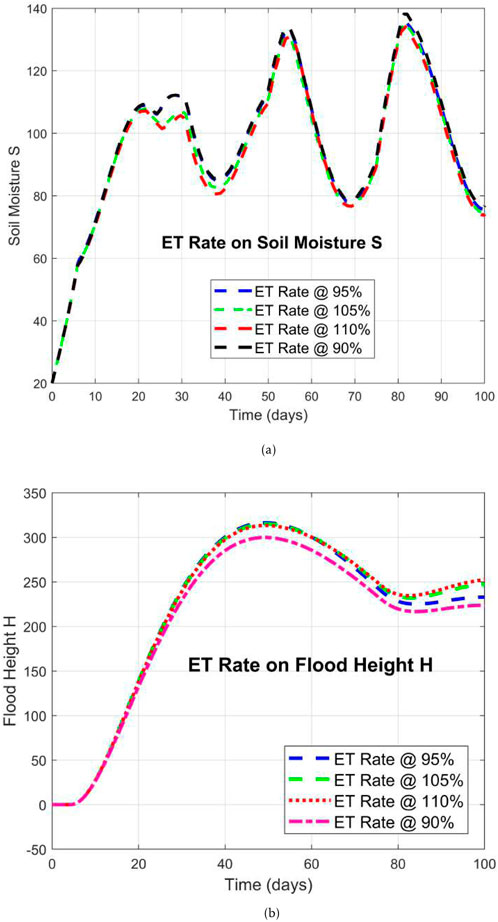

The Figure 5 shows the importance and effects of the

Figure 5. Flood raise and surface runoff caused by the rain fall with variation of the surface storage rates

The heatmap describes the flood height

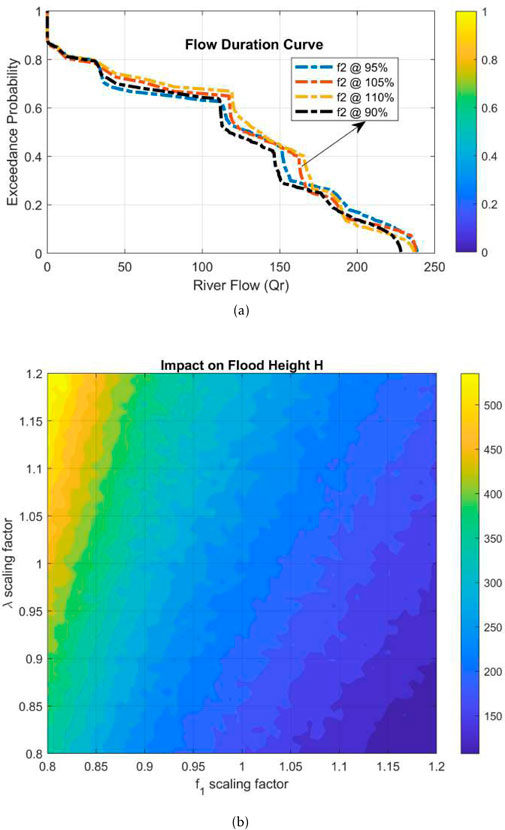

In Figures 6–8, surface runoff, and cumulative frequency distribution of flood height impacted with the help of the infiltration rates and river capacity of the FF-flood dynamical system (1.1) of FF-orders 0.98 are given. In Figure 7a, the flow duration curve (FDC) compares river flow rates

Figure 6. Surface runoff and flood height impacted with the help of the infiltration rates and river capacity of the FF-flood dynamical system (1.1) of FF-orders 0.98. (a) Infiltration rate on the surface runoff Qs under the influence of the ki. (b) nnn.

Figure 7.

Figure 8. Cumulative frequency distribution of water and flood heights analysis by the scaling parameters

In Figure 8b, the heatmap indicates the sensitivity of flood height

The impact of

Figure 9. The impact of

The Figure 10 describes the cumulative frequency distribution dynamics based on the variation in river flow

Figure 10. Cumulative probability for the frequency distribution over river flow

3.1.1 Table 1: impact of parameter variations scaled by 0.95

Table 2 highlights the role of reducing each hydrological parameter by 5% on five state variables: soil moisture

3.1.2 Table 2: impact of parameter variations scaled by 1.05

Table 2 evaluates the system’s response to a 5% increase in the same set of hydrological parameters. Increasing

3.1.3 Table 3: impact of parameter variations scaled by 1.10

Table 3 explores the influence of a 10% increase in each hydrological parameter. A sharp rise in

4 Deep learning analysis of flood dynamical system

Training an AI model for getting an optimal function

where, in Equation 4.1, the

The MSE is calculated by the following formula:

4.1 Mean square error

This section is dedicated to the AI based analysis for mean square error of the computational data driven from the FF-flood dynamical system (1.1). For this, 998 data points were considered. In this data, 499 points were assumed as the input data points while 499 points as the target data points. The data was trained under Levenberg-Marquardt principles given in the Figure 11. A gradient 0.00033837 was recorded for the epoch 987 with

where

Figure 11. Training the models data for the deep learning based analysis FF-flood dynamical system (1.1) with best validation performance

The Figure 12 is presenting error recognition and regression analysis of the data for the FF-Flood dynamical system (1.1). In the Figure 12a, the error histogram is showing the error around zero error for the validation, training, and testing data. The Figure 12b is describing the regression of the data which is shown as

Figure 12. Deep learning results for water cycle mechanism (1.1) for the FF-orders 0.98 by Levenberg-Marquardt techniques for regression and error estimations. (a) Error histogram with 20 bins representing the zero error, training data set, validation, and testing data for the FF-Flood dynamical system (1.1). (b) Regression in the training, validation and test data sets for FF-Flood dynamical system (1.1).

4.2 Regression of the data

The regression models are used to predict continuous values in corresponding to the input data points. We use linear and logistic regression for this analysis. The mathematical expression behind the linear regression is:

in Equation 4.2,

While the logistic regression generates the probability of a data and is based on the following relationship Equation 4.4:

This function, ensures output probabilities in between 0, and 1. An error histogram for the error distribution is computed as in Equation 4.5:

where,

In Figure 13, the neural networking is applied for the dynamical studies of the actual with the prediction data sets. It is observed that there is a very close similarity in the simulations for all the classes between the actual and the predicted data sets. The state 1 is showing the NN vs. actual comparison for the surface storage

Figure 13. Neural-network predictions vs. actual data sets of the variables of the FF-Flood dynamical system (1.1) for the FF-orders 0.98.

5 Conclusion

In this paper we considered a FF-flood dynamical system for the solution existence with stability results for the Hyers-Ulam type, numerical simulations and AI-based deep learning. The paper is structured for the computational results therefore the qualitative analysis is not given with their proofs. Although, we highlighted the related works from the available literature. In Section 2, the theoretical results are given related to the presumed model (1.1). In the Section 3, we have developed a numerical scheme based on the Lagrange’s interpolation polynomial for the simulations of the model. The scheme is then applied to an illustrative example for soil moisturization, water level raise and depletion affecting the flood dynamics. For lower

The Figure 12 is presenting error recognition and regression analysis of the data for the FF-Flood dynamical system (1.1). In the Figure 12a, the error histogram is showing the error around zero error for the validation, training, and testing data. The subfigure 12b is describing the regression of the data which is shown as

The study can be continued in a number of ways with consideration of more variables, parameters and different transmission rates for different regions. We highlight the following few points:

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

HK: Methodology, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. RA: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review and editing, Visualization. JA: Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. RT: Validation, Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, I., Bakar, A. A., Ahmad, H., Khan, A., and Abdeljawad, T. (2024). Investigating virus spread analysis in computer networks with Atangana–Baleanu fractional derivative models. Fractals 2440043, 17. doi:10.1142/S0218348X24400437

Amnuaylojaroen, T. (2023). Perspective on the era of global boiling: a future beyond global warming. Adv. Meteorology 2023 (1), 1–12. doi:10.1155/2023/5580606

An, R., Ji, M., and Zhang, S. (2018). Global warming and obesity: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. 19 (2), 150–163. doi:10.1111/obr.12624

Atangana, A. (2017). Fractal-fractional differentiation and integration: connecting fractal calculus and fractional calculus to predict complex system. Fractals 102, 396–406. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2017.04.027

Atangana, A., and Araz, S. I. (2020). Atangana–Seda numerical scheme for Labyrinth attractor with new differential and integral operators. Fractals 28 (08), 2040044. doi:10.1142/s0218348x20400447

Atangana, A., and Qureshi, S. (2019). Modeling attractors of chaotic dynamical systems with fractal–fractional operators. Chaos, Solit. and fractals 123, 320–337. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2019.04.020

Badawy, A., Sultan, M., Abdelmohsen, K., Yan, E., Elhaddad, H., Milewski, A., et al. (2024). Floods of Egypt’s Nile in the 21st century. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 27031. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-77002-8

Barry, S. M., Davies, G. R., Forton, J., Williams, S., Thomas, R., Paxton, P., et al. (2025). Trends in low global warming potential inhaler prescribing: a UK-wide cohort comparison from 2018-2024. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35 (1), 9. doi:10.1038/s41533-025-00415-z

Bas, E., Acay, B., and Ozarslan, R. (2019). Fractional models with singular and non-singular kernels for energy efficient buildings. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 29 (2), 023110. doi:10.1063/1.5082390

Böttcher, L., Antulov-Fantulin, N., and Asikis, T. (2022). AI Pontryagin or how artificial neural networks learn to control dynamical systems. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 333. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-27590-0

Cai, W., Zhang, C., Zhang, S., Bai, Y., Callaghan, M., Chang, N., et al. (2024). The 2024 China report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: launching a new low-carbon, healthy journey. Lancet Public Health 9 (12), e1070–e1088. doi:10.1016/s2468-2667(24)00241-x

Cao, M., Wang, F., Ma, S., Geng, H., and Sun, K. (2024). Recent advances on greenhouse gas emissions from wetlands: mechanism, global warming potential, and environmental drivers. Environ. Pollut. 355, 124204. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124204

Caputo, M., and Fabrizio, M. (2015). A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 1 (2), 73–85. doi:10.12785/pfda/010201

Clarke, R. H., Wescombe, N. J., Huq, S., Khan, M., Kramer, B., and Lombardi, D. (2023). Climate loss-and-damage funding: a mechanism to make it work. Nature 623 (7988), 689–692. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-03578-2

Darvishi Boloorani, A., Nasiri, N., Soleimani, M., Papi, R., Neysani Samany, N., Amiri, F., et al. (2024). “Climate change, dust storms, and air pollution in the MENA Region,” in Climate change and environmental degradation in the MENA Region 2024. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 327–343.

Gabr, M. E. (2023). Impact of climatic changes on future irrigation water requirement in the Middle East and North Africa’s region: a case study of upper Egypt. Appl. Water Sci. 13 (7), 158. doi:10.1007/s13201-023-01961-y

Gazi, M. A., Al Masud, A., Rahman, M. K., Amin, M. B., Emon, M., bin, S., et al. (2025). Sustainable embankment contribute to a sustainable economy: the impact of climate change on the economic disaster in coastal area. Environ. Dev. 55, 101208. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2025.101208

Gebrael, K., Mitri, G., and Kalantzi, O. I. (2024). Overview of nature-based solutions for climate resilience in the MENA region. Nature-Based Solutions 6, 100159. doi:10.1016/j.nbsj.2024.100159

Hamed, M. M., Sobh, M. T., Ali, Z., Nashwan, M. S., and Shahid, S. (2024). Aridity shifts in the MENA region under the Paris agreement climate change scenarios. Glob. Planet. Change 238, 104483. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2024.104483

Herrmann, R. (2011). Fractional calculus: an introduction for physicists. World Sci. doi:10.1142/9789814340250

Janni, M., Maestri, E., Gullì, M., Marmiroli, M., and Marmiroli, N. (2024). Plant responses to climate change, how global warming may impact on food security: a critical review. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1297569. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1297569

Jonkman, S. N., Curran, A., and Bouwer, L. M. (2024). Floods have become less deadly: an analysis of global flood fatalities 1975–2022. Nat. Hazards 120 (7), 6327–6342. doi:10.1007/s11069-024-06444-0

Khan, H., Aslam, M., Rajpar, A. H., Chu, Y. M., Etemad, S., Rezapour, S., et al. (2024). A new fractal-fractional hybrid model for studying climate change on coastal ecosystems from the mathematical point of view. Fractals 32 (02), 2440015. doi:10.1142/s0218348x24400152

Khan, A., Shah, K., Abdeljawad, T., and Alqudah, M. A. (2022). Existence of results and computational analysis of a fractional order two strain epidemic model. Results Phys. 39, 105649. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2022.105649

Khan, A., Abdeljawad, T., Abdel-Aty, M., and Almutairi, D. K. (2025a). Digital analysis of discrete fractional order cancer model by artificial intelligence. Alexandria Eng. J. 118, 115–124. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2025.01.036

Khan, A., Abdeljawad, T., and Alkhawar, H. M. (2025b). Digital analysis of discrete fractional order worms transmission in wireless sensor systems: performance validation by artificial intelligence. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 11 (1), 25. doi:10.1007/s40808-024-02237-3

Khan, H., Alzabut, J., Almutairi, D. K., and Alqurashi, W. K. (2025c). The use of artificial intelligence in data analysis with error recognitions in liver transplantation in HIV-AIDS patients using modified ABC fractional order operators. Fractal Fract. 9 (1), 16. doi:10.3390/fractalfract9010016

Khan, H., Alzabut, J., Tounsi, M., and Almutairi, D. K. (2025d). AI-Based data analysis of contaminant transportation with regression of oxygen and nutrients measurement. Fractal Fract. 9 (2), 125. doi:10.3390/fractalfract9020125

Kumar, V. R., and Mani, N. (1994). The application of artificial intelligence techniques for intelligent control of dynamical physical systems. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 8 (4), 379–392. doi:10.1002/acs.4480080407

Kumar, P., Erturk, V. S., Banerjee, R., Yavuz, M., and Govindaraj, V. (2021). Fractional modeling of plankton-oxygen dynamics under climate change by the application of a recent numerical algorithm. Phys. Scr. 96 (12), 124044. doi:10.1088/1402-4896/ac2da7

Kurniawan, T. A., Meidiana, C., Goh, H. H., Zhang, D., Jiang, M., Othman, M. H. D., et al. (2024). Social dimensions of climate-induced flooding in Jakarta (Indonesia): the role of non-point source pollution. Water Environ. Res. 96 (9), e11129. doi:10.1002/wer.11129

Nan, Y., Bao-hui, M., and Chun-Kun, L. (2011). Impact analysis of climate change on water resources. Procedia Eng. 24, 643–648. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2710

Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Gregg, J. W., Rockström, J., Mann, M. E., Oreskes, N., et al. (2024). The 2024 state of the climate report: perilous times on planet Earth. BioScience 74 (12), 812–824. doi:10.1093/biosci/biae087

Rogers, J. S., Maneta, M. M., Sain, S. R., Madaus, L. E., and Hacker, J. P. (2025). The role of climate and population change in global flood exposure and vulnerability. Nat. Commun. 16 (1), 1287. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-56654-8

Sabatier, J. A., Agrawal, O. P., and Machado, J. T. (2007). Advances in fractional calculus. Dordrecht: Springer.

Salhi, A., Benabdelouahab, S., and Heggy, E. (2024). Observation and geoinformation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observation Geoinformation 133 (10413), 2. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2024.104132

Sekerci, Y. (2020). Climate change effects on fractional order prey-predator model. Chaos, Solit. Fractals 134, 109690. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109690

Sharma, P., Khan, J. S., Radhika, K., Thatipudi, J. G., Sridevi, K., and Upadhyay, S. (2025). “Evolutionary intelligence: a hybrid neural framework for dynamic system innovation,” in 2025 international conference on electronics and renewable systems (ICEARS) (IEEE), 1743–1749.

Su, Y., and Ullah, K. (2024). Exploring the correlation between rising temperature and household electricity consumption: an empirical analysis in China. Heliyon 10 (10), e30130. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30130

Sun, H., Zhang, X., Ruan, X., Jiang, H., and Shou, W. (2024). Mapping compound flooding risks for urban resilience in coastal zones: a comprehensive methodological review. Remote Sens. 16 (2), 350. doi:10.3390/rs16020350

Terry, J. P., Al Ruheili, A., Almarzooqi, M. A., Almheiri, R. Y., and Alshehhi, A. K. (2023). The rain deluge and flash floods of summer 2022 in the United Arab Emirates: causes, analysis and perspectives on flood-risk reduction. J. Arid Environ. 215, 105013. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2023.105013

Trenberth, K. E. (2014). Water cycles and climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 31–37. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5784-4_30

Van Daalen, K. R., Tonne, C., Semenza, J. C., Rocklöv, J., Markandya, A., Dasandi, N., et al. (2024). The 2024 Europe report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: unprecedented warming demands unprecedented action. Lancet Public Health 9 (7), e495–e522. doi:10.1016/s2468-2667(24)00055-0

Van Houtven, G. (2024). Economic value of flood forecasts and early warning systems: a review. Nat. Hazards Rev. 25 (4), 03124002. doi:10.1061/nhrefo.nheng-2094

Wan-Arfah, N., Muzaimi, M., Naing, N. N., Subramaniyan, V., Wong, L. S., and Selvaraj, S. (2023). Prognostic factors of first-ever stroke patients in suburban Malaysia by comparing regression models. Electron. J. General Med. 20 (6), em545. doi:10.29333/ejgm/13717

Wang, Z., Leung, M., Mukhopadhyay, S., Sunkara, S. V., Steinschneider, S., Herman, J., et al. (2024). A hybrid statistical–dynamical framework for compound coastal flooding analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 20 (1), 014005. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ad96ce

Wu, Y., Liu, S., and Gallant, A. L. (2012). Predicting impacts of increased CO2 and climate change on the water cycle and water quality in the semiarid James River Basin of the Midwestern USA. Sci. Total Environ. 430, 150–160. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.04.058

Yang, K., Wu, H., Qin, J., Lin, C., Tang, W., and Chen, Y. (2014). Recent climate changes over the Tibetan Plateau and their impacts on energy and water cycle: a review. Glob. Planet. Change 112, 79–91. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.12.001

Yaseen, R. M., Ali, N. F., Mohsen, A. A., Khan, A., and Abdeljawad, T. (2024). The modeling and mathematical analysis of the fractional-order of Cholera disease: dynamical and simulation. Partial Differ. Equations Appl. Math. 12, 100978. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2024.100978

Keywords: flood dynamical system, simulations, artificial intelligence, probability, regression, as process innovation

Citation: Khan H, Alrebdi R, Alzabut J and Thinakaran R (2025) Cumulative probability and regression analysis of ecosystem disruption by an integrated mechanism of AI with FF-flood dynamical model. Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1630673. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1630673

Received: 18 May 2025; Accepted: 15 October 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Isa Ebtehaj, Laval University, CanadaReviewed by:

Giandomenico Foti, Mediterranean University of Reggio Calabria, ItalyPadam Jee Omar, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University, India

Copyright © 2025 Khan, Alrebdi, Alzabut and Thinakaran. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hasib Khan, aGtoYW5AcHN1LmVkdS5zYQ==; Reem Alrebdi, ci5yZWJkaUBxdS5lZHUuc2E=

†ORCID: Hasib Khan, orcid.org/0000-0002-7186-8435; Reem Alrebdi,orcid.org/0000-0003-1837-2120; Jehad Alzabut, orcid.org/0000-0002-5262-1138; Rajermani Thinakaran, orcid.org/0000-0002-9525-8471

Hasib Khan

Hasib Khan Reem Alrebdi

Reem Alrebdi Jehad Alzabut1,4,5†

Jehad Alzabut1,4,5†