- 1Department of Spatial Culture Design, Graduate School of Techno Design, Kookmin University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 2School of Computer and Data Science, Henan University of Urban Construction, Pingdingshan, China

As custodians of intangible cultural heritage and ecological knowledge systems, Chinese traditional villages face dual challenges, namely, rapidnew urbanization and the commodification of capital-driven spaces. Thus, the sustainability crisis within their living environments has become increasingly prominent. This study reviews Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space and the features of traditional villages through a literature review. It identifies six sustainable characteristics of traditional villages, grounded in the theory of the production of space. Case studies of four distinct traditional villages (Hongcun, Anhui; Yazhe Zaozu, Sichuan; Tianluokeng, Fujian; Dingcun, Shanxi) — representing diverse types and geographical contexts—were conducted to validate these characteristics. The results indicate the following: First, the sustainability of the living environment in traditional villages manifests not only in the persistence of physical spaces, but more fundamentally in the maintenance of social bonds and spiritual culture. Second, the holders of rights in traditional villages vary across regions and village types. Third, the sustainability of the living environments typically exhibits distinct local characteristics, rich experiential narratives, strong collective practices, considerable resilience, significant cultural symbolism, and close interconnectivity. These findings extend the applicability of the production of space in examining the sustainability of rural living environments, offering valuable theoretical insights and practical strategies for the conservation and sustainable development of Chinese traditional villages.

1 Introduction

Recognized as invaluable ancient villages, Chinese traditional villages are treasures of human civilization and crucial carriers of regional culture (Shan, 2008). Amid the rapid acceleration of new urbanization and the dual force of capital spatialization, these villages currently experience novel challenges (Dou et al., 2024). According to “China Urban-Rural Construction Statistical Yearbook”, China was home to 3.65 million natural villages in 2000; however, this number decreased to 2.71 million by 2010, which translates to a reduction of 26% (Feng, 2013). This significant decline underscores a sustainability crisis within the living environments of traditional villages, which fundamentally reflects a profound contradiction between the reconstruction of spatial power driven by globalization and the resistance of local culture. Therefore, it is imperative to address the sustainable development of living environments in traditional villages within the broader context of new urbanization.

In recent years, emphasis on the sustainable development of traditional villages has been increasing, resulting in substantial research output. The current study primarily focuses on the conservation and development, spatial distribution, cultural landscape, and rural tourism of traditional villages. For example, Shi et al. (2023) explored the holistic conservation of traditional villages from a socio-spatial interaction perspective, whereas Fan et al. (2023) analyzed the spatial distribution characteristics and tourism development patterns of Chinese traditional villages. Alternatively, Chen (2020) identified the unique landscape features of traditional villages from the perspectives of architecture, layout, culture, and environment, employing the concept of landscape genes. Oshan et al. (2019) employs Geographically Weighted Regression to examine spatial heterogeneity and multiscale effects. Elisabeth et al. (2020) investigates how place attachment forms in rural tourism by exploring sensory experiences and emotional connections. Alnaim (2022) explores the spatial and physicalorder of five traditional villages in central Saudi Arabia, uncovering the underlying socio-cultural dynamics. However, a systematic research on the sustainability of living environments in traditional villages from the perspective of the production of space remains lacking.

The Production of Space is a seminal work by French philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre, which was first published in 1974 and later translated into various languages. The book has become a crucial theoretical framework for scholars in philosophy, sociology, anthropology, architecture, and design (Lefebvre, 2012). Lefebvre introduced spatial dimensions into the analysis of social relations and established a triadic dialectics framework. The essence of spatial production lies in the restructuring of spaces through human social activities by utilizing diverse political, economic, and cultural forces. During this period, many spaces are reproduced, as they overlap and interpenetrate with one another (Shun and Zhou, 2014). This theory provides a crucial analytical tool for addressing the sustainability of living environments in Chinese traditional villages.

This study utilizes Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space, employing methods such as case analysis and literature review, to examine the sustainability of traditional village living environments. By analyzing cases from diverse regions, the study tests the applicability of identified characteristics and proposes corresponding sustainable development pathways. This cross-regional comparison highlights variations and commonalities in the space production processes of traditional villages across different areas, thereby offering empirical support for the theory’s broader applicability. First, the study analyzes the dialectical relationship and three dimensions within Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space to identify traditional village space production characteristics. Second, it examines the development and distribution of traditional villages in China. Through a literature review, the study identifies the value of these villages and derives their characteristics from this value framework. Finally, the research deduces the specific characteristics of sustainable living environments in traditional villages, grounded in the production of space. This deduction is tested using four highly representative cases from China’s eastern, western, southern, and northern regions to validate the sustainability of traditional villages. Based on these validated characteristics, the study further proposes pathways for sustainable development. This research provides theoretical support and practical guidance for the sustainable development of traditional villages in China, thereby expanding the application of the production of space within this context.

2 Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space

2.1 Theory of the production of space

Fifty years ago, Henri Lefebvre introduced The Production of Space, a seminal work that proposed the theory of the production of space. This theory is a crucial reference for philosophers, sociologists, architects, and urban and rural planners. After its publication, a notable shift was observed in research focus from the political analysis of the workplace to the exploration of urban environment and daily life. Moreover, urbanization was reinterpreted through the lens of spatial production (Wen and Huang, 2012). Lefebvre’s work initiated a spatial shift in sociological research, thus reaching its zenith. It offers scholars a valuable perspective for explaining social phenomena and is widely used in fields related to space such as urban planning and architectural and interior design. Chinese scholars’ engagement with the production of space began in the early 20th century, with Chen Zhong’s exploration facilitating its widespread application in China (Chen, 2010). Initially applied to urban contexts, the theory gained traction in rural studies as urbanization accelerated and national policies prioritized rural revitalization. Recent research includes Zhang’s analysis of rural spatial evolution (Zhang et al., 2016), Hu’s examination of tourism-driven cultural space evolution (Hu and Xie, 2022), and Han’s study on modernity challenges in Jingpo ethnic religious rituals’ space production to highlight the cultural characteristics of clan rituals (Han and Ming, 2020). This paper adopts the production of space as a framework to investigate protection and sustainable development strategies for traditional villages.

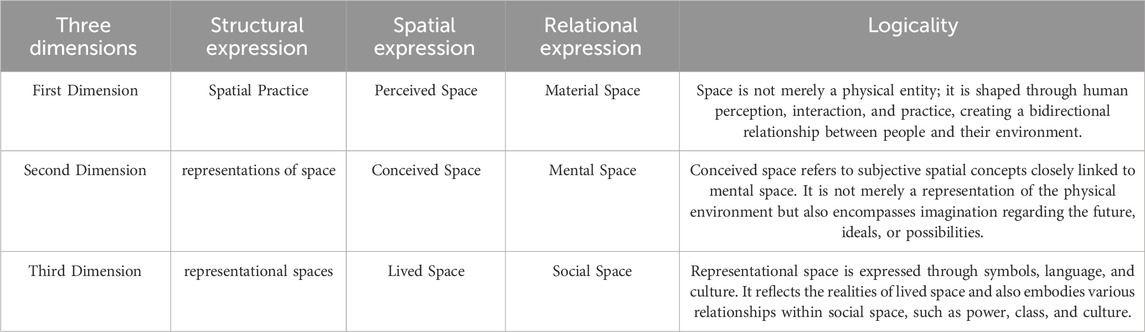

The production of space underscores that space is not a static physical entity but a dynamic one that is continually reshaped by social processes and interactions (Behnammorshedi et al., 2022). The core of this theory is the ternary space theory, which, as a structural framework, encompasses spatial practice, representation of space, and representational space. As an expression of space, it includes perceived, conceived, and lived spaces. When viewed as a relationship, this concept elucidates connections between material, mental, and social spaces. Thus, the ternary space theory is neither singular nor fixed (Ye, 2018) (Table 1).

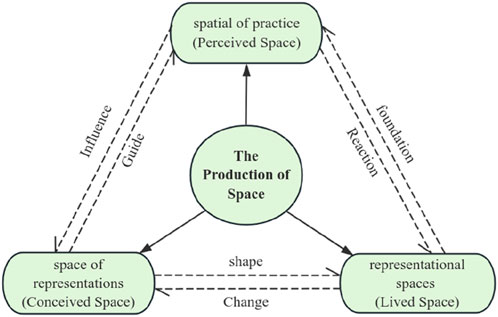

First, spatial practice underpins the production of space, thus shaping it through daily life and action (Watkins, 2005). This practice influences the representation of space, which, in turn, guides spatial practices. The representation of space involves abstract conceptualization and presentation of space, typically shaped by professionals like planners and designers. It serves not only as a conceptual framework for space but also shapes spatial practices. For example, planned roads direct people’s movements, demonstrating how spatial representation influences spatial practice. And as an abstract depiction of space, the representation of space can shape representational spaces, which may be redefined by significant historical events or cultural phenomena. Symbolic meanings and cultural values embedded in representational spaces influence people’s use of space, while spatial practice provides a foundation for representational spaces. For instance, the use of architecture provides material and context for the symbolic and cultural significance of space. On one hand, it is shaped and influenced by the representations of space. On the other hand, representational space is not static; it can change due to specific historical events or cultural phenomena. For instance, a historical building may acquire new symbolic meanings after experiencing significant historical events.

Thus, spatial practice, representation of space, and representational spaces are interconnected and mutually constitutive (Figure 1). Spatial practice provides the material foundation and practical support for the entire cycle. The representations of space act as a guiding and shaping force in between. Representational space, meanwhile, endows space with deeper cultural and symbolic meanings. The interaction among these three elements fully explains that space is not only a physical entity but also a multidimensional structure composed of social practices, symbolic meanings, and abstract representations.

2.2 Three dimensions of production of space

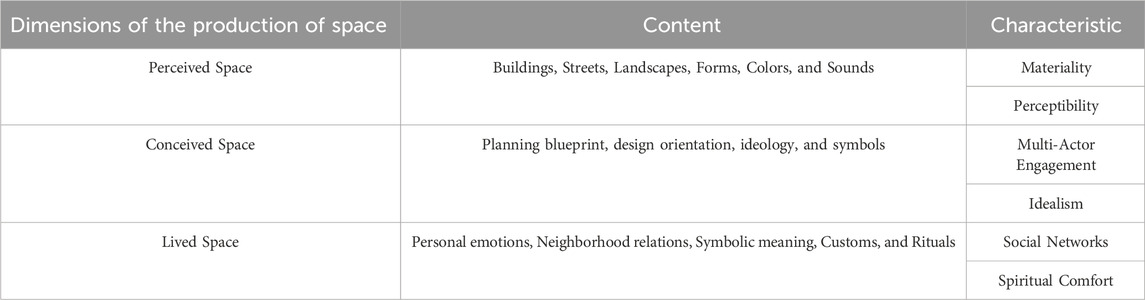

The production of space includes three core dimensions, namely, perceived, conceived, and lived spaces, each representing a different aspect of space. These concepts assist in analyzing the sustainability of living environments in Chinese traditional villages by illustrating the production of space at various levels.

2.2.1 Perceived space

According to the ternary space theory, perceived space is the spatial expression of spatial practices. It can be directly sensed and experienced through the senses such as sight, hearing, and touch. This dimension includes buildings, streets, landscapes, and transportation, which are concrete objects that exist in the material world (Pan, 2015). In traditional Chinese villages, people understand their social and cultural context by engaging with village streets, ancestral halls, temples, and farmland spaces.

2.2.2 Conceived space

Conceived space is a conceptual space envisioned through plans and designs by governments, architects, and planners, thus representing space as they perceive and experience it (Sun, 2015). In traditional villages, conceived space manifests in the planning and layout of a village, which are frequently designed based on a consideration of historical culture, religious belief, and land use (Zhang et al., 2020). Although external planners or village elders may shape its concrete form, a conceived space typically reflects needs for social structure, economic activities, and cultural identity. Traditional Chinese villages often feature squares, performance stages, or temple fair sites. This arrangement stems from historical demands for religious or social assemblies. It mirrors social order, religious convictions, and cultural norms of social interaction. In addition, the layout of traditional architecture, division of land among villagers, and design of public spaces embody elements of conceived space.

2.2.3 Lived space

Daily activities are conducted in a lived space—a social space in which residents live and operate (He, 2006). In traditional villages, lived space transcends the concept of being a physical space where people reside. More significantly, it is a spiritual space that carries emotions and memories, thus representing the experiences, identities, and interactions of individuals and communities within the space (Wang et al., 2017). The living space in traditional Chinese villages typically integrates residential areas, public spaces, and natural landscapes. For instance, streets, courtyards, and squares serve as places where villagers interact, communicate, and celebrate festivals. These interactions create distinctive spatial memories and cultural identities.

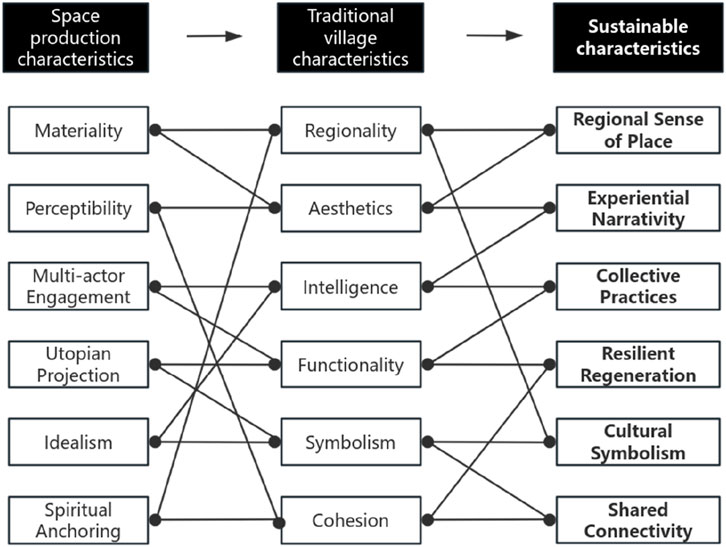

2.3 Characteristics of space production

Based on this discussion, the study identified six characteristics, namely, materiality, perceptibility, multi-participation, idealism, social networks, and spiritual sustenance (Table 2). First, Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space highlights that perceived space encompasses all elements accessible to the senses, including visual, auditory, olfactory, and tactile experiences. This includes buildings, streets, landscapes, shapes, colors, and sounds. The perceptibility of space is closely tied to its material components, leading to the identification of materiality and perceptibility as key characteristics of perceived space. Secondly, conceived space is developed by planners, architects, designers, engineers, and scientists, focusing on conceptual and abstract dimensions. It involves planning blueprints, design concepts, ideologies, and symbols. This process reflects the multi-actor engagement and idealism of perceived space. Finally, the third dimension, lived space, represents the direct experience of space. Lefebvre argues that lived space is not just a physical setting for activities but also a domain for social interactions, community engagement, emotional recollections, and symbolic significance. This results in the identification of social networks and spiritual sustenance as defining traits.

2.3.1 Materiality

As a physical entity, space encompasses a rich array of material elements such as roads, buildings, rivers, and decorations. Lefebvre argues that material space plays a decisive role in the production of space, which influences various aspects of social and economic production (Yang et al., 2024). Furthermore, although material space is relatively stable, it is continually transformed and reproduced in response to changes in society, economy, and technology.

2.3.2 Perceptibility

Space is cognizable through sensory experiences. Michel de Certeau’s theory of “walking practice” explores the perceptibility of space from multiple aspects, thereby emphasizing the central role of the body in spatial perception (Certeau, 1984). In the production of space, people interact with space through bodily senses such as observing the environment with the eyes, listening to surrounding sounds with the ears, smelling flowers and grass with the nose, and feeling the temperature of the air with the skin.

2.3.3 Multi-actor engagement

Space production involves multiple actors, including the government, capital entities, and villagers. As the primary authority, the government shapes the overall framework and direction of space production through top-level designs, such as planning and policy-making, which guide the macro layout and control of space (Shen and Ye, 2021). Driven by profit, capital entities invest in or redevelop spaces. Through daily practice, villagers shape and imbue spaces with meaning, which serve as micro-agents in space production.

2.3.4 Idealism

The idealism of space is not an abstract concept detached from society; rather, it is an ideal space co-constructed by social relations and power structures. This ideal world is a synthesis of material space, social relationship, and cultural imagination. In Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space, it exists not only as a physical entity but also as a spatial form that is constructed and reproduced by society (Zhang, 2025). Ideal space can embody either freedom and creativity or can be standardized.

2.3.5 Social network

Social networks are a significant characteristic of space production and primarily related to how social relations shape, maintain, and reproduce space (Zhao and Sun, 2017). Lefebvre posits that space serves as a medium for the reproduction of social relationships. In spatial contexts, social networks typically revolve around kinship, consanguinity, and geographical proximity-based relationships, among others, as the core, and these networks influence modes of space production.

2.3.6 Spiritual comfort

The production of space highlights that space is not only a physical carrier but also a convergence of meaning, memory, and ideology (Zhang and Deng, 2009). In space, spiritual sustenance is evoked through public buildings, such as churches, monuments, and ancestral halls, which stir emotions, memories, and cultural identity. In daily life, people form strong emotional attachments by participating in folk activities, such as festivals, weddings, and funerals, thereby gaining a sense of belonging and identity. In the context of globalization, spiritual sustenance typically exists as an invisible force, which counters homogenization. Moreover, spiritual sustenance is not static; it continually reproduces and renews relative to societal changes and life practices.

3 Sustainable characteristics of the living environments in traditional Chinese villages based on space production

3.1 Recognition process of Chinese traditional villages

The spatial dimension of traditional villages is richer than that of cities, as these villages encompass tangible cultural elements (e.g., architecture and landscapes) as well as intangible aspects (e.g., folk customs, ritual ceremonies, and traditional crafts). They represent a complex integration of material resource and cultural institutional spaces (Sun et al., 2020).

Amid the process of new urbanization, economic production efficiency has improved. However, the phenomenon of hollow villages owing to population loss remains prevalent. The hollowing out of traditional villages leads to wastage of land resources and industrial decline as well as the fragmentation and marginalization of rural culture and ecological spaces (Jiang, 2018), thereby impacting their sustainability.

Initiated by Feng Jicai and approved by the Chinese government, a multi-department joint survey and recognition of Chinese traditional villages was established in 2012. The first batch of 646 Chinese traditional villages was announced, thus marking the inclusion of traditional village conservation in national key projects. With the release of the sixth batch of Chinese traditional villages, a total of 8,115 villages have been recognized as Chinese traditional villages as of 2023.

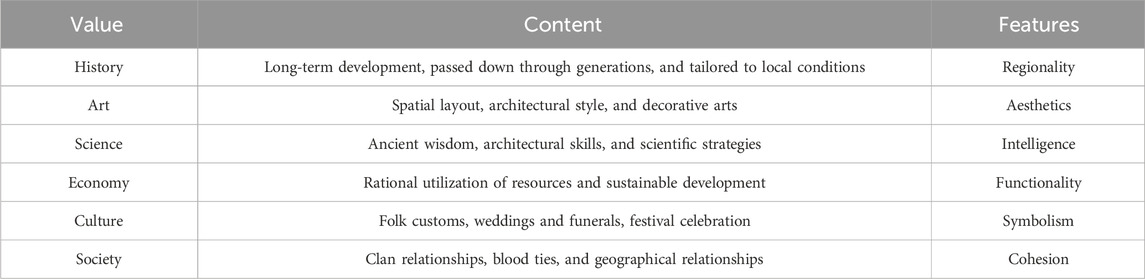

3.2 Value of traditional villages

In its “Notice on the Investigation of Traditional Villages,” which was issued on 16 April 2012, the State Council of China clearly defines traditional villages as those formed early with rich traditional resources and significant historical, cultural, scientific, artistic, social, and economic values, thus deserving protection. First, traditional villages have historical value. Traditional villages serve as essential spaces for human interaction, activities, and daily life, bearing witness to the passage of time, recording historical transformations, and carrying a wealth of historical and cultural knowledge. They act as living fossils for the study of history and ethnic culture (He and Jiao, 2023). Second, traditional villages have artistic value. Traditional villages embody significant artistic value through three interrelated dimensions: distinctive architectural styles, traditional craftsmanship, and folk art expressions (Fu et al., 2020). The built environment in these villages transcends mere functional requirements, with architectural decorations such as carved door-windows and mural paintings simultaneously manifesting regional cultural identities and aesthetic sensibilities. These artistic expressions not only reflect the aesthetic consciousness of successive generations of inhabitants but also encapsulate the craftsmanship and cultural heritage of artisans. Third, traditional villages have scientific value. Characterized by favorable natural environments, rich regional cultures, unique residential architecture, and sincere local inhabitants, traditional villages exhibit respect for nature, adaptation to local conditions, and scientific reasoning in the construction of buildings. The selection of village sites, architectural techniques, layout designs, and decorative carvings embody the crystallization of human wisdom (Shan, 2009). Fourth, traditional villages have economic value. The natural resources and landscape patterns of traditional villages have laid a solid foundation for agricultural and forestry irrigation. Meanwhile, the harmonious integration of lush green mountains, clear waters, farmlands, dwellings, and architecture creates a pastoral landscape that attracts global tourism, generating economic benefits and promoting the preservation and transmission of traditional culture (Liu and Wang, 2015). Fifth, traditional villages hold cultural value. As repositories of culture, they preserve rich historical memories and reflect local residents’ customs and lifestyles (Qin and Leung, 2021). Traditional villages serve as custodians of folk culture. By examining their festivals, rituals like weddings and funerals, and local customs, one can understand the region’s cultural context and values. Moreover, many traditional crafts and folk tales are preserved and passed on within these villages. Sixth, traditional villages possess social value. This value is multifaceted and involves various relationships, such as those based on clans, bloodlines, and geographical (Zhang and Zhang, 2021). Villagers in traditional villages reinforce their emotional bonds through mutual assistance and enhance community cohesion via ancestral halls. This strong community connection improves local stability and helps resist external conflict. Traditional villages preserve rich historical culture and customs, which aid in maintaining individual identity and fostering cultural confidence. They serve as a vital link connecting the past and the future.

3.3 Characteristics of Traditional Chinese Villages

Based on the “Notice on the Investigation of Traditional Villages,” which outlines the historical, cultural, scientific, artistic, social, and economic values of traditional villages, six features can be derived, namely, regional distinctiveness, aesthetic appeal, wisdom, functionality, symbolism, and cohesion (Table 3).

3.3.1 Regionality

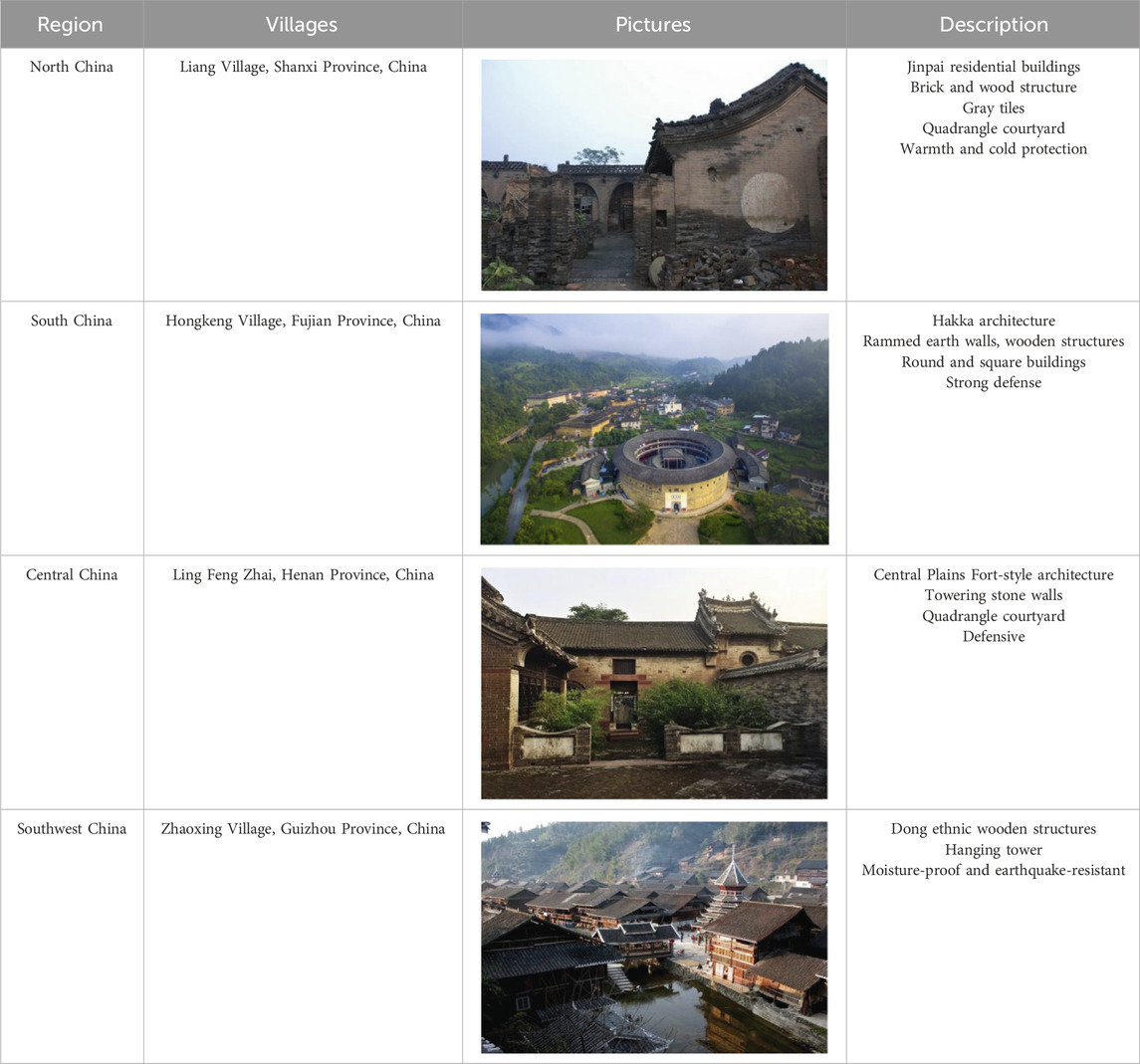

With histories typically spanning thousands of years, traditional Chinese villages serve as living fossils of historical evolution. Spatial layouts, architectural styles, folk cultures, and modes of production and lifestyle are passed down across generations, thus exhibiting strong regional characteristics (Lv, 2019). The traditional villages in each region possess distinct features due to variations in geographical environments, natural resources, and climatic conditions. Table 4 provides a list of traditional villages in the northern, eastern, southern, central, and southwestern regions of China, each showcasing unique characteristics. Shanxi Liang Village is one of the typical representatives of Jin-style vernacular architecture. Located on the Loess Plateau, the local topography directly influences its architectural style. The village features brick-walled courtyards with grey tiles, designed for insulation against cold weather. Anhui Chengkan Village is a prime example of Huizhou architecture. Its distinctive features—blue bricks, dark grey tiles, and horse-head walls—highlight a strong regional identity. Fujian Hongkeng Village represents Hakka architecture. Hakka Tulou typically houses hundreds of family members, embodying the extended family system characterized by communal living with financial independence. Moreover, these tulou serve not only as living spaces but also offer defensive capabilities, fire resistance, and seismic stability. Henan LinFengZhai, situated in central China, demonstrates its regional character through its unique red stone architecture, defensive systems, geomantic synthesis, and a blend of northern and southern architectural styles. Guizhou Zhaoxing Village is characterized by its mountainous terrain, abundant rainfall, and distinct seasons. Its stilt houses are built according to the natural contours of the mountains. The architectural style, layout, and materials of these houses are closely related to the local climate and topography.

3.3.2 Aesthetics

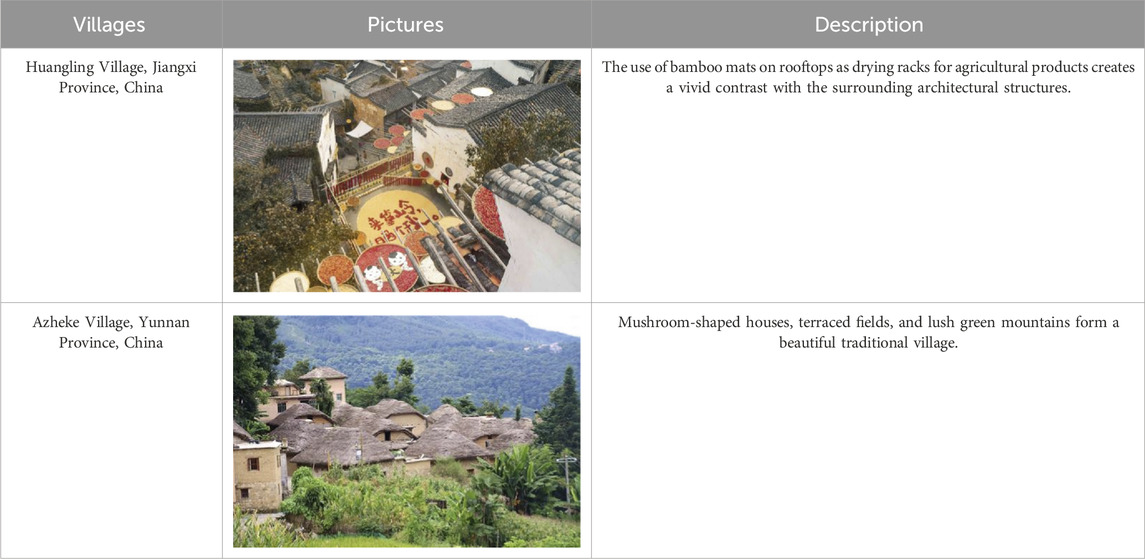

The natural landscapes and architectural styles of traditional Chinese villages possess high aesthetic value (Yang, 2017). For example, Huangling Village in Jiangxi is listed under the third batch in 2014 and known as one of China’s best tourist villages. It features a unique sight in which crops are dried on bamboo mats on rooftop frames, creating a striking contrast between the black and white Hui-style architecture and the vivid colors of the crops. Such a landscape leaves a lasting visual impression, exemplifying overwhelming natural beauty. Moreover, these customs convey a sense of peace and rhythm characteristic of traditional agricultural societies. The aesthetics of traditional villages are not merely static but can also be dynamic. Azheke Village in Yunnan is recognized as a beautiful leisure destination and as one of China’s best tourist villages. Collectively, the well-preserved village, terraced fields, forests, and water systems constitute a multi-tiered ecosystem that embodies the principle of “people-oriented, harmonious coexistence” and features picturesque aesthetic qualities (Table 5). Therefore, aesthetics are no longer limited to mere visual pleasure. They place greater emphasis on the influence of the natural environment on daily life, presenting a unique aesthetic perspective.

3.3.3 Intelligence

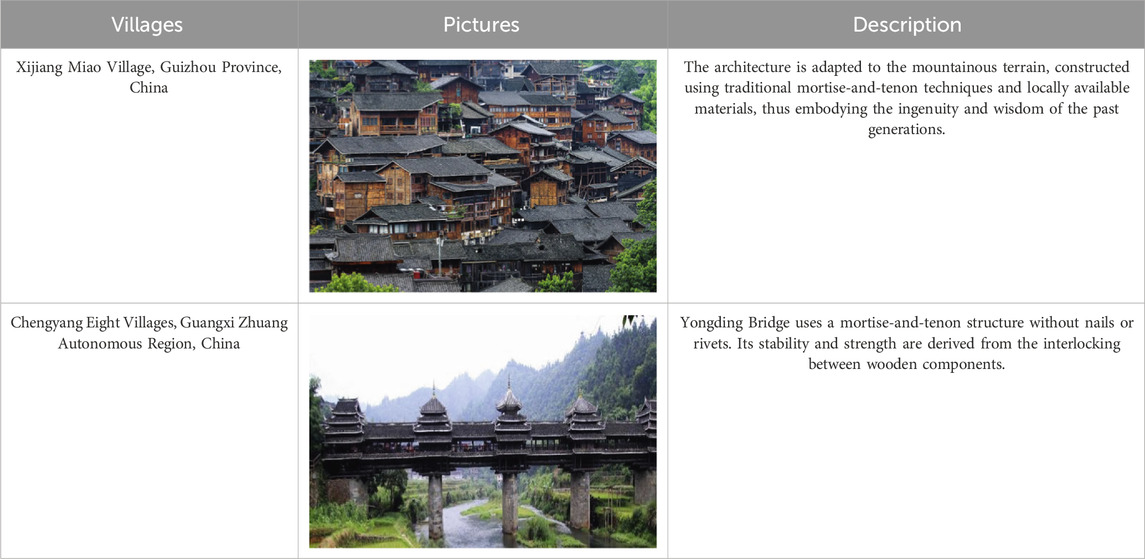

The site selection, layout, construction, defense, and ecological utilization of traditional villages exemplify the wisdom of past generations, reflecting a profound understanding and effective utilization of natural, social, and cultural resources (Li et al., 2017). The Xijiang Miao Village in Guizhou was constructed in accordance with the mountain terrain. Built with local wood, these structures demonstrate versatility and exceptional construction techniques. Not only do they reduce transportation costs for building materials, but they also help avoid damage to the ecological environment. The Chengyang Bazhai Scenic Area in Guangxi boasts over 2,000 stilted buildings, 13 drum towers, and 11 wind-and-rain bridges, with Yongding Bridge as the most representative. A typical Dong architectural marvel, Yongding Bridge was constructed without the use of nails or rivets, connected solely by mortise-and-tenon joints. Its entire structure interlaces longitudinally and transversely, thus integrating galleries, pavilions, and towers into one. It symbolizes the crystallization of the wisdom of the Dong people and serves as a masterpiece of Chinese wooden architecture. It was listed as a key cultural protection unit under the second batch (1982; Table 6). Stilted building use a elevated stilts design, which serves both to prevent dampness and to deter wild animal intrusions. The architecture of two traditional villages, Qianhu Miao Village in Guizhou and Chengyang Bazi Village in Guangxi, reflects the survival wisdom and cultural heritage of a people.

3.3.4 Functionality

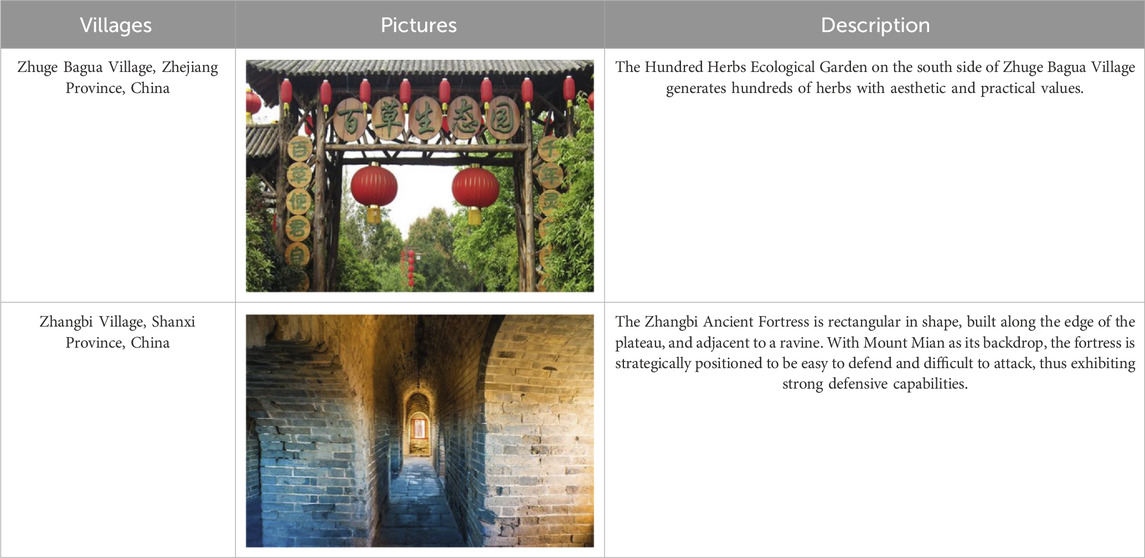

Traditional Chinese villages function as residential spaces as well as multifunctional areas for commerce, agriculture, and handicrafts (Hu et al., 2014). To achieve sustainable development, villages leverage their resource advantages to develop corresponding industries. Located in Lanxi City, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, the Zhuge Bagua Village includes the largest settlement of Zhuge Liang’s descendants, with its layout following the Bagua pattern. In 2013, it was listed as a Chinese traditional village under the second batch; in 2019, it was included under the first batch of national key rural tourist villages. The village is laid out according to the Bagua pattern. The design of the Bagua formation serves not only aesthetic purposes but also functions to regulate airflow, thereby achieving a balance in terms of feng shui. The Baicao Garden in the village, a herbal planting base, offers aesthetic and practical values. Zhangbi Village, located in Longfeng Town, was listed as a Chinese historical and cultural village under the second batch (2005), recognized as a national key cultural protection unit under the sixth batch (2006), and included under the first batch of national characteristic landscape tourist towns (villages; 2010). In 2012, it was listed as a Chinese traditional village under the first batch. Initially constructed during the period of the Sixteen Kingdoms of the Northern Dynasties, Zhangbi Ancient Fortress served as a military stronghold. The ancient city walls are connected to an underground tunnel system extending over 10,000 m, which historically functioned as a defensive structure and storage facility (Table 7). Zhangbi Village attracts a large number of tourists with its unique historical buildings. This influx not only creates jobs but also drives economic growth.

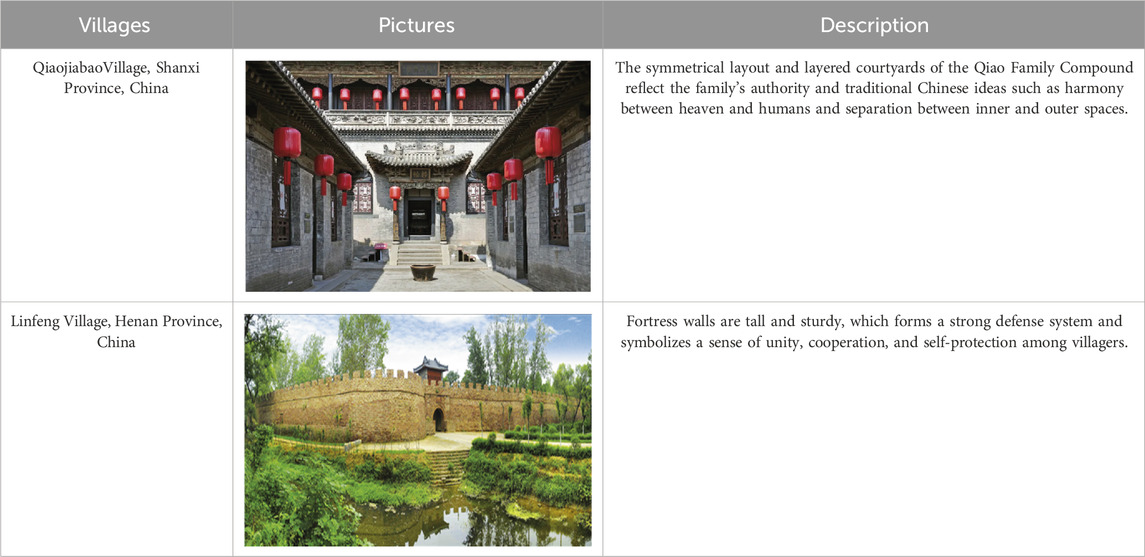

3.3.5 Symbolism

Embodying unique architectural styles, folk customs, dialects, and songs, traditional Chinese villages function as carriers of regional culture and symbols of regional identity (Zhai et al., 2017). Qiaojia Village in Shanxi is famous for the Qiao Family Compound, whose quadrangle layout embodies the family’s hierarchy and rules. The woodcarving craftsmanship in the quadrangle courtyard is exquisitely intricate, with motifs that predominantly feature the Eight Steeds, Three Stars of Fortune (i.e., Fulu, Shouxing, and Luxing), and God of Wealth, which symbolizes numerous children, blessings, and longevity. As a medium for cultural inheritance, Woodcarving displays masterful craftsmanship and strengthens cultural identity through symbolic representations. In Henan, the fortified Linfeng Village features walls that reach 6.6 m in height and extend across 1,100 m, forming a robust defense system that symbolizes the spirit of unity, cooperation, and self-protection among villagers (Table 8). Based on the analysis of these two villages, the architecture, streets, and environment of traditional villages are not mere physical entities. They are rather condensations of cultural identity, social value, and historical memory.

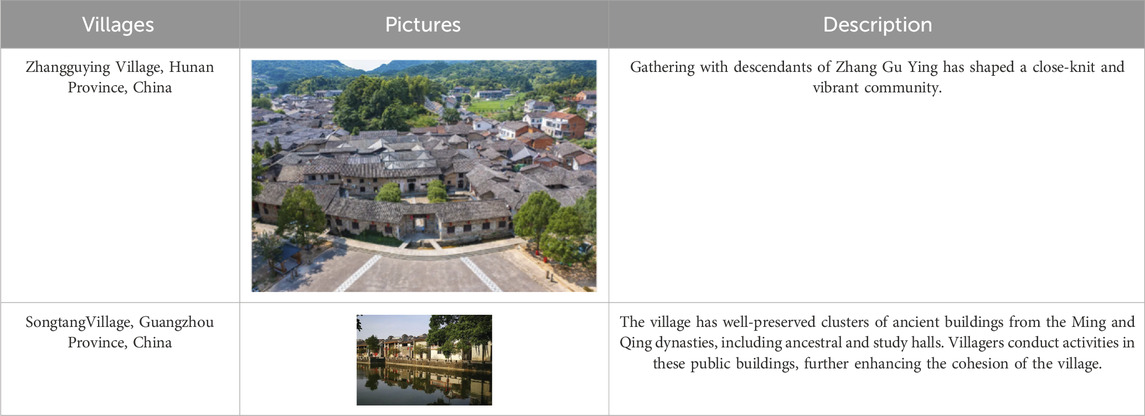

3.3.6 Cohesion

These villages tend to form stable network systems based on kinship, geographical proximity, and clan relationships. Moreover, they exhibit strong autonomy, as they are governed independently through local customs, clan rules, and village regulations. The Zhang Guying Village in Hunan, which is named after its ancestor Zhang Guying and dates back to over 500 years, consists of three major architectural complexes, namely, Dangda Men, Wangjia Du, and Xinshang Wu, with over 1,700 houses arranged in an orderly manner. Streets and alleys crisscross, thus housing more than 2,000 descendants of Zhang Guying and naturally forming a spatial structure of clan-based residence with strong clan cohesion. Songtang Village, located in Xiqiao Town, Nanhai District, Foshan City, Guangdong Province, was listed as a Chinese historical and cultural village in 2010, a Chinese traditional village in 2012, and a key village for national rural tourism under the second batch in 2020. Bound by clan ties, the village demonstrates strong cohesion. Representative buildings include the Qu Clan, Sixth Generation, Jianwu Dafu, Dongshan, and Qiaolu Ancestral Halls (Table 9). As a form of social organization, the clan relies not only on kinship but also forms a cultural community. Members are closely bound together by shared lineage history, cultural customs, and religious beliefs. This social structure achieves internal self-governance through village regulations and lineage rules.

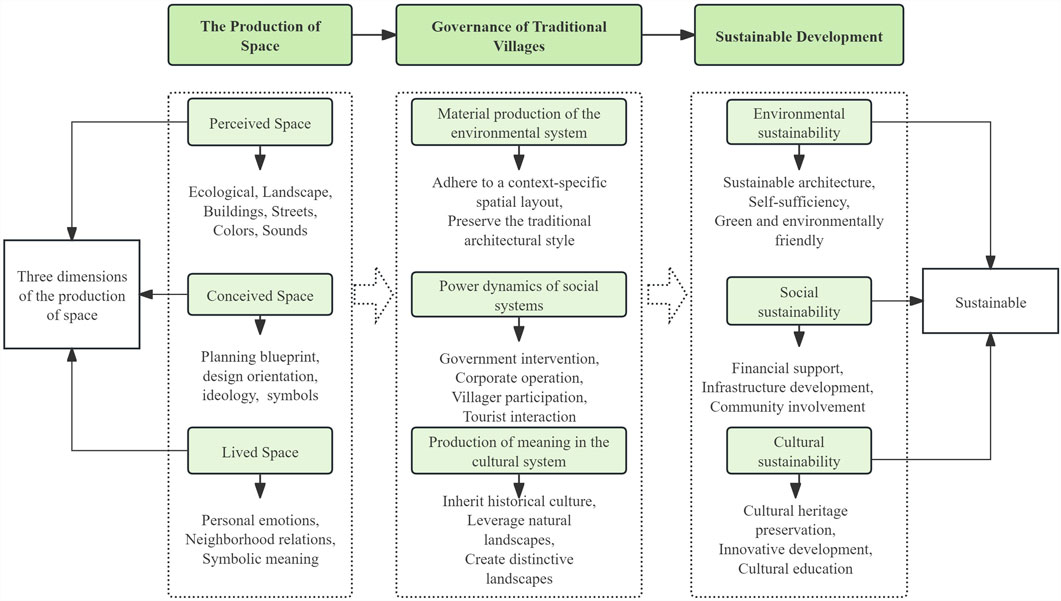

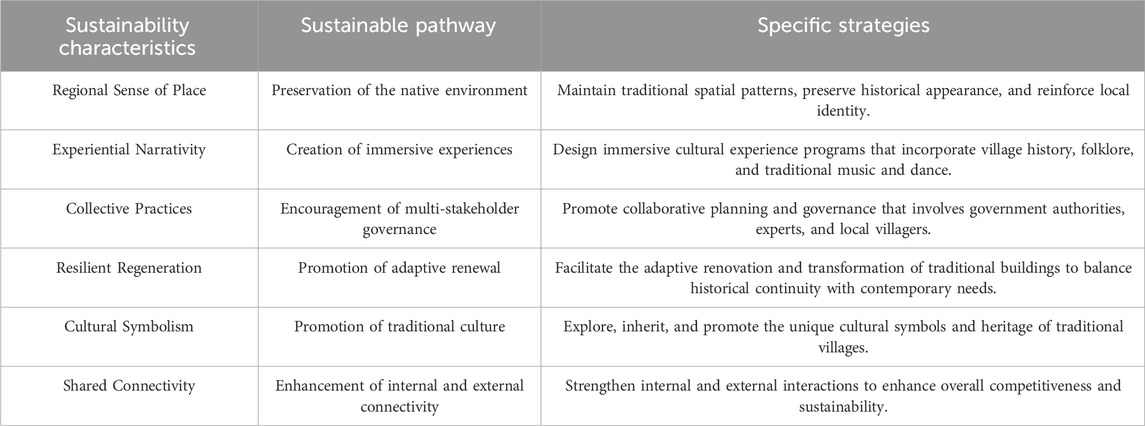

3.4 Sustainable characteristics of the living environments of Traditional Chinese Villages based on space production

Drawing from the six characteristics of the production of space (i.e., materiality, perceivability, multi-actor engagement, idealism, social networks, and spiritual anchoring) and the six characteristics of traditional Chinese villages (i.e., regionality, aesthetics, intelligence, functionality, symbolism, and cohesion; Section 3.3), we deduce six sustainable characteristics of traditional Chinese villages from the perspective of space production. These include regional sense of place, experiential narrativity, collective practices, resilient regeneration, cultural symbolism, and shared connectivity (Figure 2). Regional Sense of Place from the material dimension of the production of space. The material spatial is essential for the sense of place in traditional villages. Villages develop a strong sense of local identity through their reliance on the natural environment and the evolution of their unique culture. Experiential narrativity emerges from tangible and perceptible elements, integrating the aesthetic and wisdom inherent in traditional villages. This approach allows people to perceive narratives through direct experience, offering not just sensory engagement but also meaningful and memorable experiences. Collective practice arises from the participation of multiple individuals. Village space is not primarily for individual experience and modification, but serves as a setting for collective living and interaction. This space also reflects the wisdom and functionality inherent in traditional villages. Elastic regeneration refers to the design of public spaces. To adapt to societal development, villages gradually acquire certain functionalities. This is achieved through flexible spatial layouts, enabling cultural and ecological regeneration and adaptation. Cultural symbolism forms under the joint influence of idealistic and territorial factors during interactions and communications within social networks. It reflects group identity, values, and historical memory. Shared interconnectedness is crucial in space production. It constitutes an emotional bond based on shared perception, spiritual sustenance, and symbolic power. This bond promotes emotional identification, interaction, and cooperation among group members, thereby enhancing the group’s unity and connectivity.

Figure 2. Sustainability characteristics of the living environments of Chinese traditional villages based on the production of space.

4 Case study analysis

4.1 Criteria and rationale for case selection

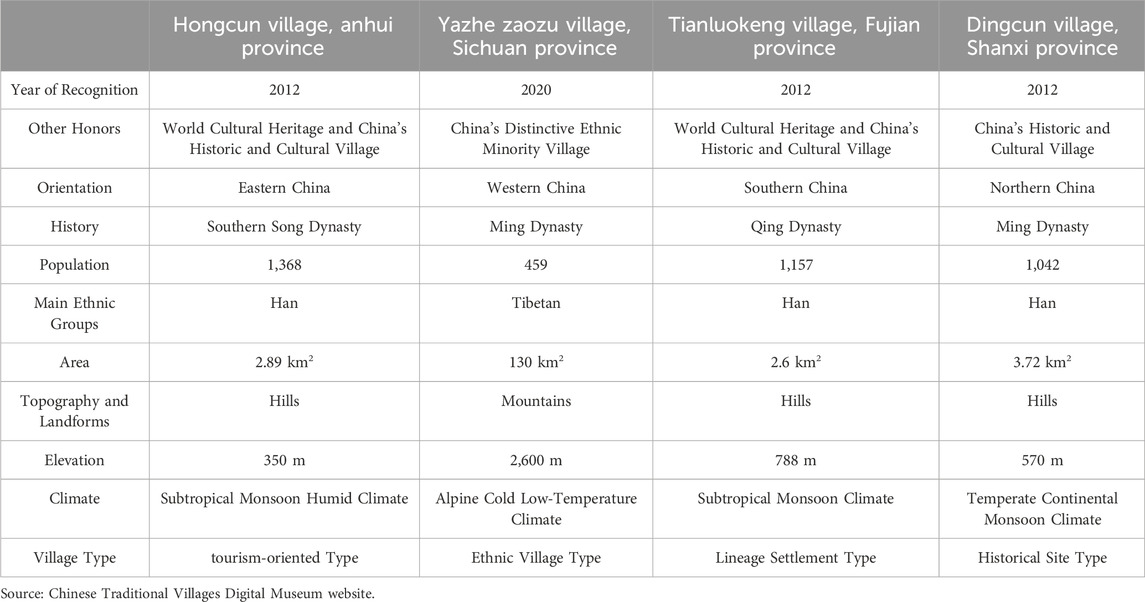

Cases are selected from four representative traditional villages in eastern, western, southern, and northern China (Table 10). The criteria for selection include inclusion in the list of Chinese traditional villages. Additionally, the villages should possess other world-class or national honors, such as World Cultural Heritage, Chinese Historical and Cultural Villages, and Chinese Ethnic Minority Characteristic Villages. Finally, they must exhibit a long history, strong regional characteristics, rich cultural heritage, well-preserved ancient buildings, and significant aesthetic values. Hongcun Village, serving as a quintessential example of Huizhou architectural typology within the space production framework, is renowned for its distinctive Huizhou architectural features and cultural heritage. Tourism functions as the primary economic engine that generates local income, upgrades infrastructure, creates employment opportunities, and facilitates cultural exchange. Therefore, Hongcun is a tourism-led traditional village. Yazhe Zaozu Village in Sichuan is a Tibetan settlement. Its songs, dances, language, cuisine, and customs exhibit distinct ethnic characteristics. Hence, Yazhe Zaozu Village is classified as a minority type of traditional village. The Hakka tulou in Tianluokeng Village are typically built by Hakka people of the same clan, who live together, forming a closed community centered on the lineage. Thus, Tianluokeng Village is a lineage-based settlement type of traditional village. Ding Village is known for its ancient built complex from the Ming and Qing dynasties and the Dingcun Archaeological Site. The site is not only listed as a first-class national key cultural relic protection unit but also selected as one of the “Top 100 Archaeological Discoveries of the Century” in China. It is categorized as a historical site type of traditional village.

4.2 Research methods and data sources

4.2.1 Research method

This study utilizes two primary research methods: literature review and case study analysis. The literature review involves examining Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space and related scholarship. This process establishes the research framework and theoretical foundation. Additionally, this study systematically synthesizes existing research on the space production mechanisms of traditional villages globally, thereby providing theoretical grounding for the case studies. The case study method examines four exemplary traditional villages, selected from different regions and listed in China’s national list of protected traditional villages. It carefully analyzes their space production mechanisms. Building on these analyses, the discussion section proposes pathways for the sustainable development of traditional villages.

4.2.2 Data sources

This study’s data is sourced from the Digital Museum of Traditional Chinese Villages and the datasets on traditional villages published by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development.

4.3 Case analysis

4.3.1 Hongcun Village, Anhui Province

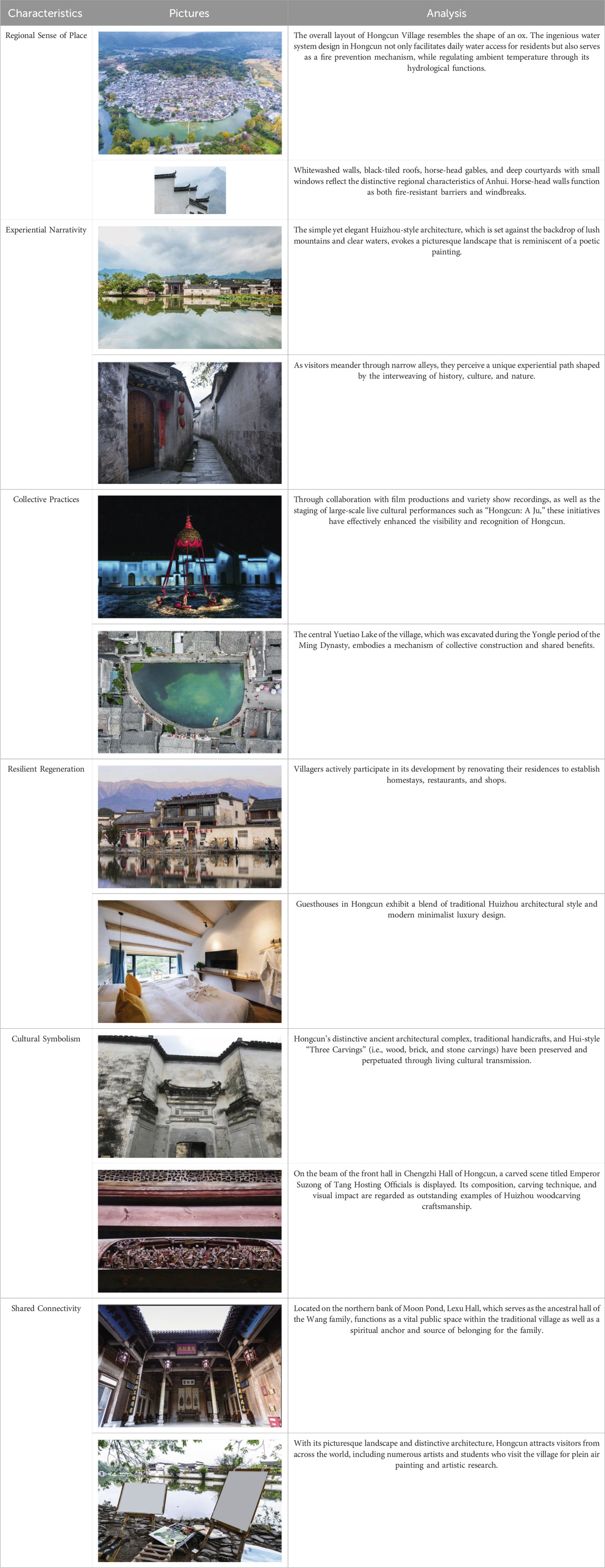

Hongcun Village, located in Hongcun Town, Yi County, Huangshan City, Anhui Province in the eastern region of China, experiences a subtropical monsoon humid climate with an annual average temperature of 7.8 °C. Situated in a low mountainous and hilly area of southern Anhui, the village is situated at an elevation of 350 m. In 2000, it was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List; in 2003, it was selected as one of the first batches of Chinese historical and cultural villages. In 2011, the China National Tourism Administration designated it as a National 5A-Class Tourist Attraction; in 2012, it was included in the first batch of Chinese traditional village listings. This village boasts a long history and rich cultural heritage. During the Shaoxing period of the Southern Song Dynasty (AD 1131), the ancestor Wang Yanji relocated his family to Hongcun after a fire. Since then, the village has flourished for over 800 years. As a typical representation of Huizhou’s traditional villages, Hongcun embodies the feudal ethics of Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism, patriarchal ethics of clan-based communal living, and geomantic culture of site selection. Furthermore, it encompasses an exquisitely crafted Huizhou-style architecture and a merchant lifestyle that values Confucianism (Fu and Li, 2022). These elements formed a unique physical space and cultural landscape that reflect the harmony between nature and humanity, encapsulating the essence of traditional rural life. Table 11 provides a detailed analysis of the six characteristics of Hongcun Village in Anhui Province.

Hongcun is situated against Leigang Mountain, facing Nanhu Lake, and positioned on a elevated plateau. Moon Pond (Yuezhao) serves as its central hub, connecting Front Street, Back Street, and the Upper Water Canal (Shangshui Zhen). The north-south streets, including Xixi Riverbank, Chahang Alley, and Zhongshan Road, contribute to a networked layout of street spaces. Streets connect residential and public buildings. They serve not only for transportation but also as key venues for daily social interaction. This distinctive social environment forms Hongcun’s unique social living space. It reflects the interconnected interpersonal relationships and community belonging characteristic of traditional villages.

The overall layout of Hongcun Village resembles the shape of an ox. The mountains serve as the ox’s head, trees as its horns, bridges as its hooves, and dwellings as its body. Fresh springs are diverted into ox-intestine-shaped channels. The water system flows through the village into the Yuezhao (ox stomach) before being filtered into the Nanhu Lake (ox abdomen). This ingenious hydraulic design provides three key functions: first, it ensures convenient daily water access for residents; second, it serves as a fire prevention system; and third, it regulates local temperature. Hongcun’s Wang Clan Ancestral Hall is located at the center of the village. It serves as a key gathering place for the Wang family and symbolizes Huizhou traditional culture, family values, and historical heritage. The Wang lineage dominates the spatial order through “ritual planning” and “resource control,” reflecting Confucian ethics and patriarchal power. The living space of Hongcun is organized around family units, with courtyards as the core, and ancestral halls and academies as important venues. Streets and alleys function as social spaces. This arrangement fosters an inward-oriented residential space that accommodates daily life requirements. Additionally, it provides spaces for rituals, scholarly activities, social interactions, and communal gatherings.

Hongcun has over 100 ancient buildings from the Ming and Qing dynasties. These buildings feature a unique Huizhou architectural style. They are characterized by gray bricks, black-tiled roofs, and horse-head walls. The irregular yet harmonious layout of village houses, closely packed in a staggered pattern, forms a unique spatial morphology. The unique ancient architectural complex of Hongcun is more than a physical residence. It serves as a witness to history. This architectural complex embodies the centuries-old vicissitudes of both the traditional village and the Wang clan, serving as a tangible witness to their historical rise and fall. It reflects the history, culture, economy, and living conditions of Hongcun. Lexu Hall, located on the northern shore of Moon Pond, serves as the Wang Clan Ancestral Hall. It functions not only as a public space in the traditional village but also as the spiritual anchor for the clan. The hall preserves extensive historical records. These documents trace the clan’s development. It embodies reverence for ancestors. It transmits valuable historical culture. Lexu Hall is a vital living space in Hongcun. Villagers use the ancestral hall as a bond. This strengthens clan identity and cohesion. The hall thus becomes a key space for cultural tradition and spiritual continuity. Nanhu Academy, as a former educational institution, has cultivated numerous talents across various fields. It provides significant impetus for Hongcun’s cultural development.

4.3.2 Yazhe Zaozu village, Sichuan Province

Yazhe Zaozu Village is located in the Baima Tibetan Township, Pingwu County, Mianyang City, Sichuan Province, in the western region of China. It is bordered by Jiuzhaigou to the east, Wanglang Nature Reserve to the west, Huanglong to the south, and Eli Village to the north. Nestled in lush forests, the village sits at an elevation of 2,300 m and experiences a typical high-cold and low-temperature ecological climate with an annual average temperature of 8 °C–12 °C, long sunshine hours, large temperature differences between day and night, and abundant precipitation. It was listed under the fourth batch of Chinese traditional villages (2018), under the third batch of Chinese Ethnic Minority Characteristic Villages (2019), and as one of the key villages for rural tourism in Sichuan Province (2020). Additionally, in 2013, the Baima “Tiao Cao Gai” was listed as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage. Yazhe Zaozu Village is one of the “Baima Eighteen Villages” and retains the most primitive cultural characteristics of the Baima Tibetans, thus boasting unique songs, dances, clothing, customs, and habits, with distinct ethnic features and rich cultural heritage. Table 12 provides a detailed analysis of the six characteristics of Yazhe Zaozu Village in Sichuan Province.

Yazhe Zaozu Village features a unique spatial layout due to its distinct geographical location. Its buildings are set against mountain backdrops. They concentrate in specific areas. The village regulates spatial order through the “Yihua Ping” system and clan authority. The “Yihua Ping” Institution in villages typically involved adult male villagers congregating in public plazas or open spaces to mediate communal affairs. These affairs include land allocation, dispute resolution, and major decisions. This system enables participation in villages governance through collective decision-making. The Baima Tibetan people typically practice Bon religion. They regulate village spatial order through religious rituals and guidance from religious leaders. The Baima Tibetans possess distinctive cultural elements. These include unique songs, dances, clothing, and customs. Key cultural features are the “Tiao Caogai” ritual, white felt hats, and rooster totem roof decorations. The “Tiao Caogai” is an ancient ritual for exorcism and blessing. During the first month of the lunar calendar, villagers perform an annual ritual to invoke favorable weather conditions and ensure communal health and wellbeing.

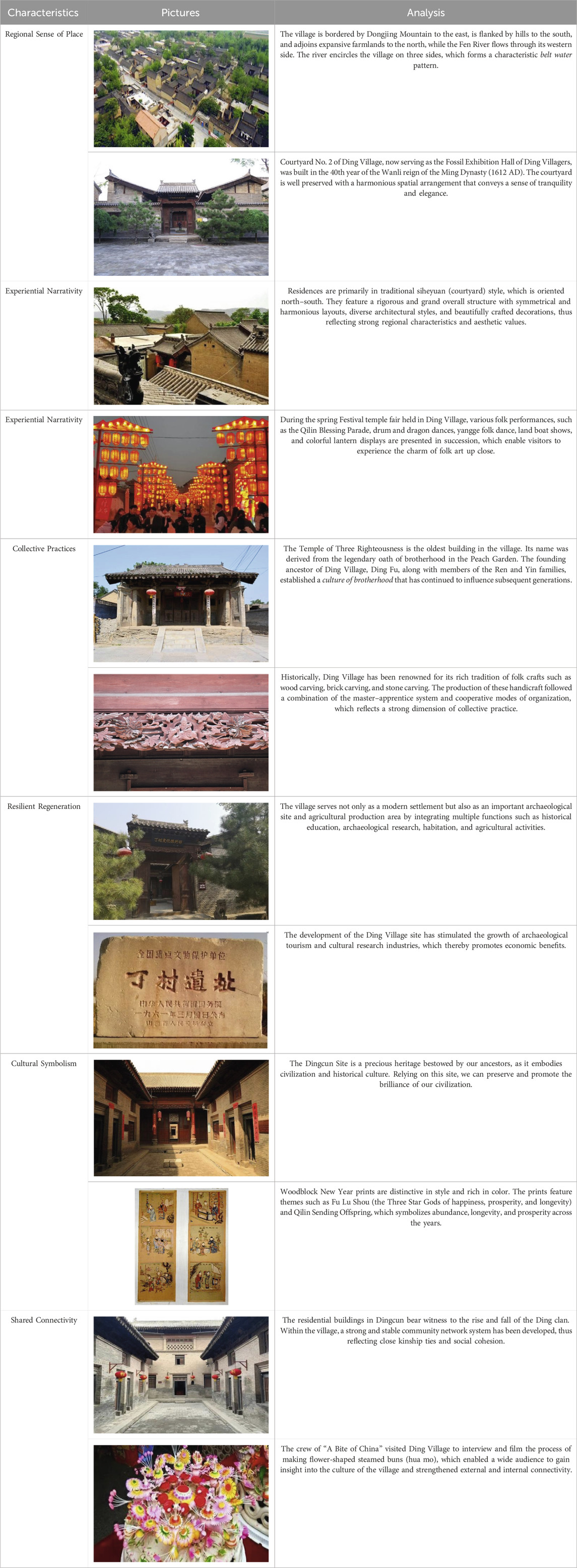

4.3.3 Tianluokeng Village, Fujian Province

Tianluokeng Village is a natural village administered by Shangbanliao Village, Shuyang Town, Nanjing County, Zhangzhou City, Fujian Province. The village is named after its terrain, which resembles the shape of a field snail, and its fertile land that yields abundant field snails. Located in southern China, it features a subtropical monsoon climate characterized by warm, humid weather and a generally pleasant atmosphere, and is surrounded by picturesque mountains. In 2003, it was listed under the first batch of Chinese historical and cultural villages; in 2008, it was included in the World Heritage List. In 2012, it was listed under the first batch of Chinese traditional villages. A quintessential Hakka Tulou settlement, Tianluokeng Village features robust earth walls with a thickness of 1.5 m, enabling effective thermal insulation, humidity regulation, and defense. The village comprises five distinct earth buildings, namely, the square Buyun Lou, circular Zhenchang Lou, Ruiyun Lou, Hechang Lou, and oval Wenchang Lou. Buyun and Hechang Lou were the first to be constructed in 1796 during the Jiaqing era of the Qing Dynasty followed by the other three buildings. The Tianluokeng Village establishes firm connections based on kinship ties and exhibits a strong sense of clan lineage. Its unfired-earth buildings, which combine economy, sturdiness, defensiveness, and aesthetic appeal, serve as a quintessential example of the Hakka earth buildings in Fujian. Table 13 presents the six distinctive traits of the Tianluokeng Village in Fujian.

Tulou buildings in Tianluokeng reflect their historical and cultural context. As symbols of Hakka culture, they serve not only as residences but also reflect clan relationships, power structures, and social order. The enclosed architectural form of Tulou not only reinforces familial cohesion within the Hakka clan but also embodies the authoritative entity’s spatial control. Room allocation mirrors resource distribution and social hierarchy within the village. Additionally, tulou architecture embodies residents’ cultural identity.

4.3.4 Ding Village, Shanxi Province

Ding Village is located in Xincheng Town, Xiangfen County, Linfen City, Shanxi Province, in the northern part of China. It belongs to the Loess Plateau region and experiences a temperate continental monsoon climate with distinct seasons. Ding Village is renowned for its distinctive characteristics, including “Ancient Land of Civilization,” “Waves of the Fenhe River,” “Ancient Post Station and Merchant Gang,” and “Covenant Culture.” It was included under the list of Chinese traditional villages (2012) and selected as one of the Sixth Batch of Famous Chinese Historical and Cultural Villages (2014). Moreover, it was listed under the Sixth Batch of National Civilized Villages and Towns (2020). The village features two national key cultural relics protection units, namely, Dingcun Folk Houses and the Dingcun Site. Dingcun Folk Houses, which were first built during the Ming Dynasty, feature a layout of courtyard houses. They are simple yet elegant and represent precious examples of northern courtyard–house architecture. The Dingcun Site is a Paleolithic-era site and fills the 500,000-year gap between the Peking Man and Upper Cave Man and represents an important cultural heritage left by ancestors. Table 14 present the six characteristics of Ding Village in Shanxi Province.

The Ding family residences face south with strict hierarchical arrangements. The Sanyi Temple in Ding Village derives its name from the story of the sworn brotherhood in the Peach Garden. Its culture of brotherhood continuously imparts moral principles to Ding descendants. Through the integration of merchant guild economy and ritualized spatial order, the Ding clan effectively governs village order. This maintains harmony and stability in the community. Additionally, Ding Village historically excelled in folk crafts. These include woodblock New Year paintings, printing plates, and wood carvings. The intergenerational transmission of these crafts, which has ensured their cultural continuity, forms the foundation of Ding Village’s distinctive architectural and folk cultural heritage.

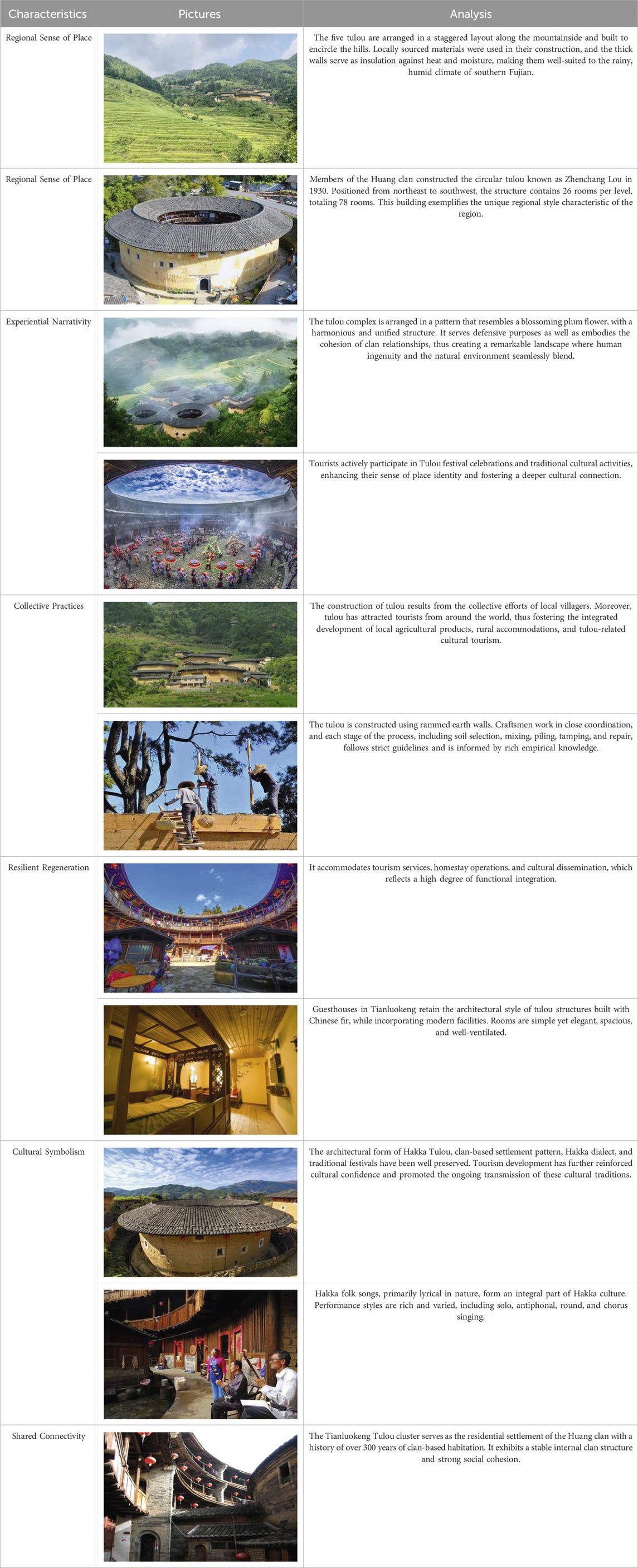

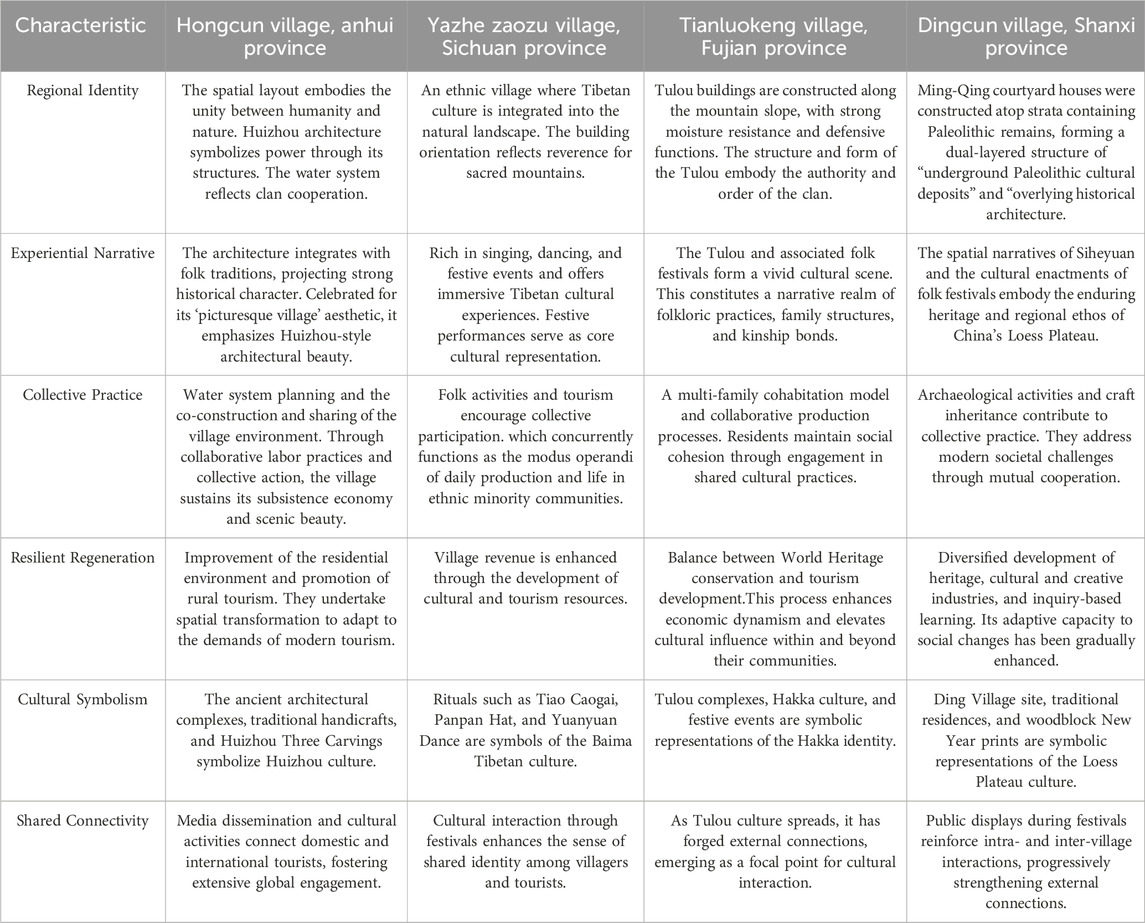

4.4 Case study synthesis

By analyzing four typical Chinese traditional villages in different regions, namely, Hongcun in Anhui, Yazhe Zaozu in Sichuan, Tianluokeng in Fujian, and Ding in Shanxi, the study identifies six characteristics, namely, regional specificity, experiential narrativity, collective practicality, resilient regeneration, cultural symbolism, and shared interconnectedness. The study found that the four villages exhibited these six characteristics, which showcase the regional, variety, and richness of Chinese traditional villages. Table 15 summarizes the six characteristics of the four traditional villages.

First, all four villages demonstrate the ecological wisdom of “unity between humanity and nature.” They construct sustainable environmental systems through adaptive designs that respond to topography, water systems, and climate. Hongcun exemplifies harmonious coexistence between humans and nature with its “ox-shaped” water system and Huizhou-style architecture. Yazhe Zaozu Village, an ethnic settlement in plateau forests, organically integrates Tibetan culture with nature. Its architectural layout preserves distinctive Tibetan cultural features. Second, all villages regulate social order through public spaces and institutional norms. However, their power subjects differ. Yazhe Zaozu Village relies on democratic deliberation at the village assembly square and clan authority. This reflects the self-governance of Tibetan tribal communities. Tianluokeng Village designates clans as power subjects. They manage land allocation, formulate clan rules, and handle clan affairs. Ding Village demonstrates Shanxi merchants’ familial authority through merchant guild economy and ritualized spatial order. Finally, all villages preserve and promote traditional culture through traditional architecture, folk customs, and ritual systems. This enhances community identity and cohesion. The ancestral halls, academies, and other public architectural spaces in Hongcun Village serve as critical nexuses for reinforcing clan identity within the Huizhou lineage system. Yazhe Zaozu Village preserves unique Tibetan traditions. These include the Tiao Caogai ritual, white felt hats, and Baima Tibetan songs. Dingcun features archaeological sites and woodblock New Year paintings. These highlight distinctive Shanxi merchant culture and craftsmanship.

4.5 Sustainable development framework for traditional villages

As mentioned previously, this study focuses on four main types of traditional villages: Tourism-oriented villages, Ethnic Minority villages, Lineage Settlement villages, and Historical Site villages. Tourism-oriented Type villages typically rely on tourism as their primary economic activity. The growth of rural tourism promotes local income, enhances infrastructure, creates jobs, and facilitates cultural exchange. It also contributes to regional economic development. However, over-tourism can damage traditional architectural styles and cause environmental pollution. Ethnic Village Type villages are typically inhabited by ethnic minorities and exhibit distinct cultural features, such as unique music, dance, language, cuisine, customs, and religious beliefs. Lineage Settlement Type traditional villages typically consist of communities formed by members of the same lineage or surname, bound by blood ties. The ancestral hall within these villages serves not only as a site for ancestral worship but also as a gathering place for family members, a forum for resolving disputes, and a venue for establishing family values. It symbolizes the family’s unity and the spirit of collectivism. Historical Site Type villages typically feature significant historical buildings and cultural heritage. They serve as witnesses to specific historical periods or events. Consequently, these villages often attract history enthusiasts, researchers, and students who visit to explore and study the site. Moreover, outstanding traditional villages in China also encompass Ecological Adaptation Type, exemplified by the Hani Terraced Field Villages in Yuanyang County, Yunnan Province; Agricultural Inheritance Type, represented by Huangling Historic Village in Wuyuan County, Jiangxi Province; and Red Memory Type, illustrated by Shaoshan Village in Xiangtan City, Hunan Province.

Based on the production of space, this study develops a sustainable framework for traditional villages (Figure 3). In the material production of traditional village environmental systems, adhering to locally adapted spatial layouts and preserving traditional architectural features contribute to environmental sustainability. In the power dynamics of traditional village social systems, strengthening top-level design leadership, introducing professional management teams, enhancing villager participation, and fostering tourist interaction collectively promote social sustainability. The production of meaning in cultural systems, preserving historical heritage and promoting cultural continuity, while strategically utilizing natural landscapes to create distinctive cultural spaces, enhances traditional villages’ cultural sustainability. Overall, the sustainable development of traditional villages can be achieved through the interplay of the three spatial dimensions.

5 Discussions

Drawing on the theoretical tenets of The Production of Space, this study formulated an analytical framework for assessing the sustainability of living environments in Chinese traditional villages, thereby elucidating six defining characteristics. The sustainable attributes of living environments have been empirically validated using case studies on four representative traditional villages situated in diverse geographical regions. Building on the summary of these characteristics and the results of such verification, this section further explores the paths for achieving sustainability in the living environments of traditional villages (Table 16).

5.1 Protecting the indigenous environment

Preserving the indigenous environment is crucial for the sustainable development of Chinese traditional villages. Historic site-based traditional villages, characterized by significant historical architecture and cultural heritage, serve as material witnesses to specific historical periods or events. These villages consistently attract amateur historians, researchers, and students for visitation and scholarly investigation. Preserving such villages requires, first, adherence to a spatial layout that adapts to local conditions. Chinese traditional villages are often situated in areas surrounded by mountains and water, which reflects the harmony between humanity and nature. For instance, Chengkan Village in Anhui Province is laid out in accordance with the Eight Trigrams (Bagua) pattern. Second, preserving traditional architectural aesthetics is crucial, including historical layouts, architectural styles, and unique streetscapes. Third, restoration projects should aim to restore old buildings to their original conditions using traditional techniques and materials. This approach, which involves minimal interference and focuses on authenticity, can ensure a harmonious relationship between the village and its natural surroundings. By safeguarding the indigenous environment of these villages, distinct regional identities can be enhanced, and a sense of local pride and belonging can be fostered.

5.2 Crafting immersive experiences

Immersive experiences are created through the engagement of multiple senses, dimensions, and participatory interactions, thus enabling visitors to delve into the histories, cultures, local customs, folk traditions, songs, and dances of traditional villages. First, immersive narrative spaces can be developed by preserving ancient buildings and streets and creating authentic landscapes that transport visitors back in time. Second, experiences that stimulate multiple senses can be designed. Vision is the most immediate sensory system. In ancient villages, modern technologies, such as lighting and projection, are used to create vibrant and colorful visual effects. In addition to visual enhancement, creating experiences that engage the other senses is essential. For instance, in Yvoire, France, visual, tactile, olfactory, auditory, and gustatory sensations are seamlessly integrated to create a multi-layered and multidimensional immersive experience. Third, genuine cultural customs can be incorporated by exploring traditional culture and preserving cultural heritage through handicraft reenactments, folk performances, and multimedia displays. Fourth, digital technologies, such as augmented and virtual reality, can be leveraged to enable visitors to participate in immersive interactions. Immersive experiences arouse interest as well as foster an in-depth understanding and appreciation of traditional culture.

5.3 Fostering multi-stakeholder engagement in governance

The conservation and advancement of Chinese traditional villages should be a collaborative effort that involves the government, experts, businesses, residents, and tourists. The first point is guidance using a top-level design or government intervention. As the main body of the local authority, the government should formulate corresponding protection and management measures. The local government of Hongcun has undertaken a holistic “Ancient Huizhou” initiative for the entire Huangshan region, establishing the “Ink-Wash Hongcun” brand identity. Correspondingly, it has promulgated normative documents including “Measures for the Protection and Management of World Cultural Heritage in Xidi and Hongcun Villages, Yi County” and its implementation rules, alongside the Interim Measures for the Maintenance and Repair of Heritage Site Buildings. Furthermore, the government has formulated and refined the Conservation Plan for the Ancient Villages of Xidi and Hongc. The second point is management conducted by professional teams or enterprise operation. Through various operations, management ensures that traditional villages maintain standardized management practices during development. The third point is the stimulation of grassroots vitality or villager participation. Indigenous residents, as crucial cultural custodians and historical witnesses, should be encouraged to participate in the management and planning of villages. In the French town of Yvoire, residents directly participate in the production of space, shaping the town’s spatial identity with their lifestyles and actions. Under governmental guidance and support, they engage in space production by adorning their homes with flowers. Residents cultivate diverse floral arrangements in courtyards, on windowsills, and at entranceways, transforming the town into the “Ville Fleurie” (Flowered Town). This approach not only enhances the aesthetic quality of residential spaces but also generates a distinctive touristic landscape that reinforces the town’s spatial uniqueness. The fourth point is the formation of tourism experiences or tourist interaction. Tourist involvement enhances internal and external communication and sharing, which fosters a deeper spatial identity among visitors. Multi-stakeholder engagement promotes mutual oversight, balanced interests, and information exchange, thus advancing the sustainable development of traditional villages.

The interaction among government, experts, villagers, and tourists not only facilitates the sharing of cultural resources but also fosters mutual supervision and collaboration, ensuring equitable benefit-sharing in traditional villages. The government assumes a regulatory role by controlling village planning, guiding development trajectories, and formulating policies to regulate utilization. Tourism developers, as key actors, place-making traditional villages through investment, operation, and promotion, attracting tourists to generate profits while driving space production and development. Meanwhile, villagers and tourists actively participate in distinct ways, collectively shaping the conceived space of the village.

5.4 Promoting adaptive renovation

Adaptive renovation in Chinese traditional villages refers to the modernization of certain spaces or organizations while preserving cultural heritage and historical features in an effort to promote sustainable development. First, infrastructure upgrade should be conducted without compromising historical aesthetics. Second, ecological landscape renovation should involve the restoration of green spaces, farmlands, and water bodies using landscape repair and ecological restoration techniques for enhancing the overall environment. Third, indoor space modernization can be achieved without altering architectural form by focusing on upgrading indoor facilities. Fourth, spatial function transformation should involve the conversion of certain ancient buildings into craft workshops, museums, or guesthouses. In this manner, historical elements can be preserved while meeting modern functional needs. Adaptive renovation stimulates village vitality and boosts the potential for sustainable development.

The burgeoning rural tourism not only boosts village revenue, enhances infrastructure, creates employment opportunities, and fosters external exchanges, but also stimulates regional economic growth. However, excessive tourism development may lead to the degradation of architectural integrity and ecological environments. For tourism-dependent traditional villages, three key strategies are imperative: Firstly, implementing precision governance by delineating core protection zones where modern construction or alteration of architectural landscapes is prohibited; Secondly, implementation of a visitor carrying capacity management system. Entry is managed via a registration-based reservation mechanism, with mandatory flow control measures activated upon exceeding regional carrying capacity thresholds; Thirdly, innovating benefit-sharing mechanisms via equitable distribution of ticket revenues, enabling indigenous residents to participate in co-creation, co-construction, and co-benefiting processes.

5.5 Promoting traditional culture

Traditional culture is the soul of Chinese traditional villages. The primary focus is to delve deeply into traditional culture, which can be achieved using approaches such as literature surveys and oral history studies to comprehensively explore traditional culture followed by systematic organization and classification. Another point is to organize festival celebrations, such as the Zhuang’s “San Yue San” and the Dai’s Water-Splashing Festival, which aid in establishing cultural brands. Furthermore, digital platforms can be leveraged, such as online museums, to facilitate the online dissemination of traditional culture. For example, the Dunhuang Mogao Caves have established an online exhibition hall for virtual tours. Promoting traditional culture fosters cultural confidence, local identity, and cohesion, which drives cultural and economic prosperity.

For Lineage Settlement villages, three key strategies are essential: first, formulating a sustainable tourism development plan that ensures the protection of cultural heritage while advancing tourism; second, implementing systematic conservation of cultural DNA, such as establishing an architectural gene bank to document blueprints and models of traditional structures and issuing traditional architecture renovation guidelines; third, creating dynamic preservation and transmission mechanisms, including adapting selected traditional buildings into museums, folklore centers, or cultural hubs.

5.6 Enhancing connectivity and interaction

Bound by blood ties, geographical proximity, and clan relations, Chinese traditional villages exhibit strong internal cohesion. First, internal connectivity should be strengthened by utilizing public spaces such as ancestral halls, academies, and streets. Second, connectivity between the village and the outside world should be enhanced using digital platforms and social media. Doing so enables external resources to participate in the protection and development of traditional villages. This two-pronged approach to internal and external interaction could overcome geographical barriers. This approach also enables efficient resource integration and promotes cooperation and sharing among the government, private capital, and residents. Consequently, it provides strong impetus for the sustainable development of traditional villages.

6 Conclusion

This study explores the sustainability of Chinese traditional villages through the lens of Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space. Theoretically, this study extends the application of Lefebvre’s the production of space to diverse contexts of traditional villages, enhancing its theoretical applicability and depth in this domain. Through analysis of the triadic dimensions—perceived, conceived, and lived spaces—it reveals the material production, social relations, and power structures underlying the sustainability of traditional villages, culminating in the identification of six distinctive characteristics of the production of space. Secondly, synthesizing policy backgrounds and prior research, six key features of traditional villages are distilled. Finally, the study develops a conceptual framework for sustainable human settlements in traditional villages based on the production of space, deriving six defining characteristics, which are empirically validated through case studies of four representative villages across different regions.

The study reveals that the sustainability of living environments in Chinese traditional villages is not only manifested in the preservation of physical space but, more profoundly, also in the maintenance of social relations and spiritual culture. The sustainable living environments of Chinese traditional villages typically exhibit distinct regional locality, rich experiential narrativity, strong collective practicality, good resilient regeneration, notable cultural symbolism, and closely shared connectivity. The power structures of traditional villages vary across regions: in Han communities, authority tends to be concentrated among family elites, whereas ethnic minority villages are more inclined toward deliberative consensus in collective decision-making. In addition, This study advances context-specific sustainability pathways for traditional villages, categorized by typological differentiation. These pathways not only establish an empirical foundation for sustainable development but also provide an actionable development framework for local governments and the scholarly community. They provide theoretical support and practical guidance for the sustainable protection and development of traditional villages.

The significance of this study is primarily reflected in two aspects. Theoretically, it enriches the applicability of the production of space, thus extending its scope from urban to rural spaces. Rural spaces exhibit distinctive characteristics that differentiate them from urban environments, encompassing folk customs, lineage systems, power structures, and social relations. The research demonstrates that this theory offers a robust framework for understanding the complexity of traditional villages, which provides a new perspective on their sustainability. Practically, by comparative analysis of sustainable characteristics across diverse typologies and regions, the study advances a novel analytical framework and innovative pathways for the conservation and development of traditional villages. Traditional villages confront the dual challenges of rapid urbanization and excessive commercialization, creating an urgent imperative to reconcile cultural preservation with sustainable development. By contextualizing Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space within the lived realities of traditional villages and proposing multidimensional pathways tailored to typological differentiation, this research aims to deliver actionable guidance for policymakers and practitioners. Traditional villages face dual challenges from rapid urbanization and commercialization pressures, necessitating the reconciliation of cultural preservation with sustainable development. This study contextualizes Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space within the socio-spatial realities of traditional villages and proposes multidimensional pathways tailored to the typological differentiation of traditional villages. The research seeks to provide actionable guidance for policymakers and practitioners.

Certainly, this study has its limitations. First, in terms of case selection, the study is constrained by its relatively limited sample size, focusing on only four traditional villages across four regions. The sample was limited in its geographical and typological coverage, as evidenced by the absence of sampling in the Northeast, Northwest, and Central China regions. Second, the research methodology primarily relies on qualitative case studies and lacks quantitative support and spatial data analysis. Although the in-depth analysis of four villages yields detailed contextual data, the limited sample size constrains both the statistical generalizability and scientific validity of the conclusions. Third, in applying Western the production of space to China’s rural context, the integration of indigenous philosophical concepts—such as clan ethics and harmony between humanity and nature lacks sufficient depth. Future research will broaden the scope of case studies. It will encompass traditional villages across diverse regions and types for in-depth analysis. Future research will integrate various methods, such as questionnaire surveys and GIS spatial analysis, to enhance the breadth and depth of the study. This approach could facilitate a more systematic understanding of the sustainability mechanisms of traditional villages.

In summary, this study innovatively applies the the production of space to systematically investigate the sustainability of living environments in Chinese traditional villages and proposes a forward-looking research framework alongside practical pathways. Theoretically, the study advances the in-depth interpretation and application of the theory within the Chinese context, thus enriching its use in rural studies. Practically, it offers actionable pathways for the conservation and sustainable development of traditional villages. More significantly, it provides new insights for the sustainable development of traditional villages as well as contributes to Chinese experience and academic wisdom in terms of the reconstruction of harmonious relationships between humans and space, tradition and modernity, and local and global contexts.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MS: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis. J-EK: Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2024S1A5C3A01042885).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alnaim, M. M. (2022). Discovering the integrative spatial and physical order in traditional Arab towns: a study of five traditional najdi settlements of Saudi Arabia. J. Archit. Plan. 34, 223–238. doi:10.33948/jap-ksu-34-2-5

Behnammorshedi, H., Gaed, R. S., Eftakhari, R., and Meshkini, A. (2022). The right to the city and the pattern of participatory planning, an analysis of the social production of urban spaces with emphasis on megamalls of Tehran metropolis. Geogr. Dev. 20, 1–34. doi:10.22111/J10.22111.2022.6690

Chen, Z. (2010). Fundamental innovations in space production, development ethics and contemporary social theory. Study Explor. 1, 1–5.

Chen, H. (2020). Analysis of landscape gene identification and its characteristics of traditional villages: a case study of Zhuge Bagua village. J. Landsc. Res. 12, 101–104. doi:10.16785/j.issn1943-989x.2020.3.021

Dou, Y., Li, Y., and Li, B. (2024). The action logic and realization path of the organic renewal of human settlement environment in traditional villages. J. Nat. Resour. 39, 1815–1834. doi:10.31497/zrzyxb.20240805

Elisabeth, K., Carlos, P. M., and Maria, J. C. (2020). Place attachment through sensory-rich, emotion-generating place experiences in rural tourism. J. Destination Mark. Manag. 17, 100455. doi:10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100455

Fan, L., Liu, Y., and Zhang, D. (2023). Spatial pattern of tourism development of Chinese traditional villages and its influencing factors. Econ. Geogr. 43, 203–214. doi:10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2023.07.020

Feng, J. (2013). The dilemma and the way out of traditional villages: traditional villages are another type of cultural Heritage. Folk. Cult. Forum 1, 7–12. doi:10.16814/j.cnki.1008-7214.2013.01.002

Fu, C., and Li, J. (2022). Productive logic and value return of traditional rural cultural space in the tourism field. Jianghan Trib. 10, 131–137.

Fu, J., Zhou, J., and Deng, Y. (2020). Heritage values of ancient vernacular residences in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China: spatial patterns and influencing factors. Build. Environ. 188, 107473. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107473

Han, L., and Ming, Q. (2020). Research on the modernistic dilemmaof Jingpo’s traditional religious ritual space production. Hum. Geogr. 35, 44–51. doi:10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2020.05.006

He, X. (2006). Spatial turn in social theories. Chin. J. Sociol. 2, 34–48. doi:10.15992/j.cnki.31-1123/c.2006.02.003

He, S., and Jiao, W. (2023). Conservation-compatible livelihoods: an approach to rural development in protected areas of developing countries. Environ. Dev. 45, 100797. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100797

Hu, J., and Xie, H. (2022). The evolution of rural cultural space driven by Tourism--based on the space production theory. J. Hubei Minzu Univ. Philosophy Soc. Sci. 40, 99–109. doi:10.13501/j.cnki.42-1328/c.2022.02.009

Hu, Y., Chen, S., Cao, W., and Cao, C. (2014). The concept and cultural connotation of traditional villages. Urban Dev. Stud. 21, 10–13.

Jiang, C. (2018). The accurate connotation,essence and planning quintessence of the rural revitalization strategy. DongYue Trib. 39, 25–33. doi:10.15981/j.cnki.dongyueluncong.2018.10.004

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 81–84.

Li, B., Liu, P., Dou, Y., Zeng, C., and Chen, C. (2017). Research progress on transformation development of traditional villages’ human settlement in China. Geogr. Res. 36, 1886–1900. doi:10.11821/dlyj201710006

Liu, X., and Wang, S. (2015). Difficulties and countermeasures of Chinese traditional villages conservation. Agric. Hist. China 34, 99–110.