- College of Humanities, Donghua University, Shanghai, China

Urban expansion in rapidly developing regions increasingly relies not merely on technical infrastructure but on symbolic spatial design as a means of identity construction. This study investigates how Shanghai’s regenerated waterscapes operate as symbolic infrastructures that shape public perceptions of governance and belonging. Drawing on 36 in-depth interviews and thematic analysis, the research examines citizens’ interpretations of revitalized canals, eco-corridors, and digital water systems. The findings indicate that three-quarters of participants (75.0%) embed biographical memory and local belonging into regenerated waterscapes, whereas an even larger share (80.6%) interprets governance through ritualized maintenance, signage, and visible responsiveness. This study concludes that these symbolic attachments enable water infrastructure to legitimize state authority and reinforce social cohesion in contemporary China.

1 Introduction

On a bright afternoon along Suzhou Creek, the scene is striking. Young residents lounge on the newly restored embankments, sipping coffee and posing for photos against the backdrop of minimalist bridges and red-brick warehouses—urban relics now curated as lifestyle icons. On social media platforms, images of the creek proliferate under hashtags such as #SuzhouCreek, tracing a digital map of civic pride and lifestyle aspiration. Nearby, elderly locals walk their dogs with unhurried steps, nodding toward camera-toting visitors—not with irritation, but with quiet satisfaction. To them, this transformation is not merely picturesque—it is personal. After all, they remember what this place once was: dark, fetid, and forsaken. The air reeked of decay, and the creek served as a dumping ground, hidden behind industrial facades. It was Shanghai’s back alley—unseen, unloved, unworthy of postcards. Once relegated to the margins of urban vision, Suzhou Creek has reemerged as a central symbol of environmental remediation, urban pride, and aspirational livability. On 22 August 2024, the Chinese official newspaper People’s Daily reported on the new greenway project along Suzhou Creek in Shanghai. The 11.2-km-long trail runs the inner and outer rings of the city while increasing routine interaction between residents and the city’s water bodies (Ji, 2024).

Yet beyond its functional achievements—improved water quality, expanded public space, architectural continuity—how does such a transformation signify? This paper contends that large-scale waterscape projects in Shanghai serve not only environmental and recreational purposes but also symbolic functions central to contemporary governance. Through the revitalization of Suzhou Creek, Xuhui Riverside, Qiantan Waterfront, Dianshan Lake, and numerous other waterscape projects, the city enacts what might be termed “soft power infrastructures”: spatial interventions that produce legitimacy, narrate futurity, and mediate citizen-state relations through affective landscapes. When residents describe these riverside zones as “civilized,” “livable,” or “finally ours,” they express more than material comfort—they articulate claims to symbolic inclusion, spatial belonging, and a vision of urban order. This study explores these dynamics, analyzing how ecological design, aesthetic curation, and public accessibility converge to project governance imaginaries, embodying Shanghai’s evolving socio-political aspirations through the language of landscape and the symbolism of water.

Urban political ecology (UPE) has increasingly drawn attention to the symbolic dimensions of water infrastructure, positioning it not merely as a technical system but as a medium of meaning-making, statecraft, and identity construction. Scholars such as Gandy (2021), Swyngedouw (2023), and Weatherford and Ingram (2022) have demonstrated how hydrological systems perform aesthetic and ideological functions in urban contexts, shaping political legitimacy and civic narratives. Boelens et al. (2023) and Shoko (2025) expand this view by exploring water-related infrastructures as affective and visual assemblages, embedded within broader ecopolitical imaginaries. Other contributions (Gandy, 2021; Hurst et al., 2022; Martinez, 2022; Alda-Vidal et al., 2023; Bhalla, 2024; Alvarado, 2025) have further emphasized the emotional and symbolic governance of infrastructures within the city. While studies by Kaika et al. (2023) and Swyngedouw (2023) interrogate how modernist water-related infrastructures reflect ideologies of control, such symbolic readings remain underdeveloped in Chinese scholarship. Existing Chinese studies (Chang and Zhu, 2020; Wang et al., 2022) largely adopt technical or institutional perspectives, with limited attention to symbolic capital or identity production. Even culturally oriented works (Yuan et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2025) rarely engage with the aesthetic and semiotic power of water governance. This literature gap calls for a renewed analytical focus on symbolic legitimacy, particularly in rapidly urbanizing contexts like Shanghai, where water infrastructure plays an integral yet under-theorized role in shaping state–citizen relations and urban imaginaries.

Rather than treating water infrastructures as neutral, technical systems, this study foregrounds their symbolic dimension, interrogating how they serve as vessels of collective meaning, civic identity, and political authority. Building on Kaika et al. (2023) call for a reimagining of urban political ecology and Swyngedouw (2023) critique of how capitalist natures are produced and naturalized through urbanization, the symbolic is here defined as the discursive, visual, and affective strategies through which waterscapes produce shared understandings of urban belonging and legitimacy. Following Gandy (2021), infrastructure is understood not merely as a material system but as a political-aesthetic assemblage shaping symbolic urban identity. This paper thus purports that symbolic infrastructure refers to the physical and spatial arrangements that convey metaphorical value and socio-political meaning; symbolic governance captures the intentional use of signs, rituals, and representations by the state to shape perception and legitimize power; and affective infrastructure emphasizes the sensory and emotional registers through which urban environments are experienced and politicized. In the Shanghai context, these symbolic forms are embedded in planning logics, design aesthetics, and narrative strategies, functioning to legitimate authority, construct subject positions, and mediate how water infrastructure is experienced as a site of meaning. Symbolism is thus not incidental but constitutive of governance systems—infusing everyday infrastructure with ideational weight and political imagination.

Rather than treating legitimacy as a stable attribute or top-down mandate, this study conceptualizes it as a mutual meaning-making process forged through symbolic interaction between the state and its citizens. In particular, it distinguishes and then reconnects two interdependent dimensions: projected legitimacy—which refers to the state’s intentional deployment of symbolic messages via infrastructure aesthetics, spatial design, and ritualized governance—and perceived legitimacy, which concerns how these symbolic cues are emotionally interpreted, internalized, and possibly contested by the public. Rather than treating these as analytically isolated, the study draws on theories of co-construction and iterative meaning loops (Wang et al., 2025) to argue that legitimacy is symbolically mediated and affectively received through interactions with both infrastructure and discourse. Methodologically, this is captured in a dual-sourced dataset that includes perspectives from both institutional actors (e.g., planners, frontline implementers) and public users of these water spaces. Analytically, the study tracks how legitimacy claims are translated, affirmed, or subverted across these groups. This research identifies a recursive dynamic in which projected and perceived legitimacy mutually reinforce one another, operating through both thematic narratives and symbolic infrastructures to build urban belonging and enhance governance visibility.

The significance of this research lies in its departure from technocratic or institutional accounts of water governance, instead treating infrastructure as an emotional and semiotic system embedded in symbolic politics. In doing so, the paper responds to a persistent gap in Chinese urban studies: the lack of attention to how water infrastructures shape, reflect, and reinforce symbolic legitimacy. By integrating perspectives from political ecology, urban design, and environmental communication, the study offers an interdisciplinary framework that expands current understandings of how water systems function not only administratively but symbolically. This approach is especially relevant in China, where governance increasingly relies on orchestrated visuality, spatial narratives, and emotional appeal to cultivate state legitimacy and social cohesion. In Shanghai, water infrastructure becomes a site of strategic meaning production—used to signal modernization, environmental responsibility, and civic unity. The emotional ties between citizens and state-curated waterscapes thus reveal underlying mechanisms of symbolic governance. By theorizing and empirically demonstrating this process, the study contributes new insights to global debates on infrastructure symbolism while offering a localized reading of symbolic power in China’s urban governance landscape.

2 Literature review

2.1 Symbolic power of urban water infrastructure: a globally recognized lens largely underexplored in Chinese contexts

While water infrastructure has long been studied for its technical and governance dimensions, a growing body of international scholarship has emphasized its symbolic power in shaping urban imaginaries, legitimacy, and socio-political control. This perspective, grounded in urban political ecology, understands water as not merely a resource but as a medium of power, meaning, and identity. For example, Gandy (2021) conceptualizes urban water systems as emblems of modernity, articulating their role in shaping the aesthetic and political values of the city. Swyngedouw (2023) deepens this view by linking the material circulation of water with the symbolic circulation of political authority, highlighting how infrastructural design becomes a performative act of control and legitimacy. Weatherford and Ingram (2022) point out that water infrastructure operates on both functional and symbolic fronts, shaping social order and cultural values. Perreault (2017) emphasizes the discursive struggles over water systems, suggesting that control over water flows is often symbolic of deeper political power arrangements. Calling for a “site multiple” methodology, Connolly (2019) proposes tracing everyday practices and lived experiences across dispersed sites to reveal how humans and non-humans jointly shape urban processes that extend beyond the city through metabolic and circulatory flows. Adams et al. (2020) bring water security into this political frame, exploring how conflict and governance interweave in urban water narratives. Hommes et al. (2019) likewise situate water governance as a security complex, shaped by equity claims, social justice debates, and symbolic framings of urban water crises.

However, in Chinese urban contexts, the symbolic dimensions of water infrastructure remain remarkably under-theorized. While Chinese philosophy and statecraft have historically endowed water with deep symbolic and cosmological significance (Li, 2018), contemporary empirical work has largely reduced water governance to environmental service provision and ecological restoration. For example, while Ricart et al. (2019) and Bischoff-Mattson et al. (2020) explore how water infrastructures are deployed in climate resilience and multifunctional land-use strategies in Europe and South Africa, respectively, similar symbolic and political analyses are missing from Chinese environmental planning literature. Although studies such as Yuan et al. (2024) provide valuable insights into the hidden symbolism of urban-mountain-water-land relations, and Meng et al. (2021) contextualize the rise of urban ecology in China, these works do not fully interrogate how water infrastructure serves as a performative vehicle of state legitimacy and urban identity. Zhang et al. (2021) discuss Shanghai’s ecological network governance but overlook symbolic dimensions. Similarly, Chang and Zhu (2020), Zhang et al. (2018), and Li et al. (2017) examine sustainability and resource demands, but their focus remains on policy efficiency rather than representational power. Thus, while symbolic water politics has become a recognized theme in global scholarship, especially under the banner of urban political ecology, Chinese cities like Shanghai remain marginal in these conversations.

2.2 Functional emphasis and technical governance in Chinese urban water studies: a blind spot on symbolic and legitimacy dimensions

Chinese urban water research has grown substantially in the last two decades, especially under the growing emphasis on eco-civilization, sustainable development, and resilience planning. However, these studies tend to focus on functional governance frameworks, often prioritizing planning integration, technological adaptation, and infrastructural efficiency. In doing so, they frequently under-theorize the symbolic roles that water infrastructure plays in shaping urban political legitimacy, identity, and authority. For example, studies like Chang and Zhu (2020), Wang et al. (2022), and Wang et al. (2025) examine integrated resource planning, civilian river chiefs, and urban waterscapes, reflecting a technocratic approach to water management. Similarly, Yuan et al. (2024) identify underlying cultural meanings in mountain–water–city relationships, but their analysis remains aesthetic and historical, with limited exploration of legitimacy performance. In Shanghai, Zhang et al. (2021) and Meng et al. (2021) have contributed early frameworks for understanding water-related urban transitions, yet these are rooted in governance structure and political economy, respectively. Feng and Yamamoto (2020) focus on the urban flood reduction function of Shanghai’s sponge city projects, while Liu and Zhang (2022) foreground spatial integration across water sectors, but both remain instrumentalist, avoiding representational analysis. The Suzhou Creek corridor, as analyzed by Jiang et al. (2016), reveals how urban ecological aesthetics increasingly serve as vehicles of image-building in the city, yet this study still stops short of interpreting how such projects foster symbolic governance or contribute to deeper political legitimacy.

Notably, although Shanghai is a global megacity with major ecological and infrastructural transformations (Feng and Yamamoto, 2020; Den Hartog, 2021), studies have seldom addressed how water systems serve as performative infrastructures, reflecting the symbolic authority of the state or municipal leadership. This gap persists even as the city embarks on ambitious projects like the Dianshan Lake ecological restoration and Sponge City initiatives, which carry immense symbolic and representational significance in media, public discourse, and policy staging. Consequently, although rich in planning, engineering, and ecological governance studies, the existing Chinese literature on urban water overwhelmingly emphasizes technocratic performance, leaving the discursive, symbolic, and legitimacy-producing functions of water infrastructure under-conceptualized.

2.3 Urban political ecology: a critical lens missing from Chinese symbolic water studies

Urban Political Ecology (UPE) has emerged as a transformative framework for understanding the politics of environmental planning, infrastructural systems, and the symbolic and material struggles embedded in urban landscapes. Rooted in Marxist geography and political economy, UPE emphasizes how urban environments are co-produced through social, political, and ecological processes, often reinforcing or contesting existing power structures and hegemonies (Connolly, 2019; Kaika et al., 2023; Swyngedouw, 2023). Crucially, UPE scholars have increasingly focused on infrastructural symbolism, where environmental projects (e.g., water restoration, green space design, and flood defenses) act as spectacles of statecraft, legitimacy, and urban branding. For instance, Gandy (2021) discusses the “urban metabolism” of water systems, linking water infrastructures to capital accumulation, social inequality, and aesthetic representation. Loftus (2019) analyzes how water management becomes a site of political contestation, while Swyngedouw (2023) frames hydro-social cycles as arenas for producing authority and exclusion. This critical perspective is particularly relevant to global cities where water infrastructures are highly visible and performative, such as Los Angeles (Joshua, 2020), London (Niranjana, 2022), and Jakarta (Ernstson and Swyngedouw, 2018). In these cases, water is not merely a resource but a political symbol, performing state capacity, modernity, or eco-consciousness.

However, the application of UPE in Chinese urban contexts remains scarce, especially in symbolic water-related planning. While some studies, such as Chen and Zang (2021), begin to explore eco-aesthetics in Chinese urban redevelopment, they often lack the critical edge of UPE—failing to interrogate how infrastructure conveys power, legitimacy, and ideological messaging. This gap is striking in a city like Shanghai, where water mega-projects such as Dianshan Lake ecological repair, Sponge City pilots, and Suzhou Creek Bay waterfront redevelopment are deeply tied to image-building, social governance, and urban visioning. Even when UPE is lightly referenced in Chinese studies, it is often instrumentalized, used to critique fragmentation or governance capacity (Liu and Zhang, 2022), rather than to expose the semiotics of state power embedded in ecological design. In short, symbolic water projects in China are fertile ground for political ecological analysis, yet the tools of UPE remain underapplied. Therefore, this research builds on UPE’s theoretical foundation to investigate how Shanghai’s water infrastructure functions as both an ecological system and a vehicle of symbolic governance and urban legitimacy—a gap left unaddressed in both Chinese water studies and global UPE literature.

2.4 Bridging symbolism, theory, and urban ecology in China’s water imaginaries

This study addresses key gaps in the existing literature. First, while international research increasingly acknowledges the symbolic, legitimizing, and affective dimensions of water infrastructure, such symbolic and cultural readings remain largely underexplored in the Chinese context, where water governance is still primarily treated as a functional and technical domain. Second, scholarship on China’s urban water governance has predominantly focused on institutional coordination, policy adaptation, and engineering frameworks but has yet to fully engage with how symbolic design, narrative framing, and aesthetic strategies contribute to public legitimacy and environmental subjectivity. Third, although Urban Political Ecology (UPE) offers a powerful lens for analyzing the interplay of power, infrastructure, and ideology, its application to symbolic infrastructure projects—especially in rapidly transforming Chinese megacities like Shanghai—remains scarce. To fill these gaps, this paper investigates the symbolic dimensions of water governance in Shanghai. Drawing on qualitative interviews with both citizens and grassroots implementers, the study examines how cultural identity, territorial belonging, and environmental meanings are embedded in the city’s hydrological planning processes. The research is guided by the following questions:

• RQ1: How do Shanghai residents engage with symbolic dimensions of urban water infrastructure as expressions of collective memory, identity, and governance visibility?

• RQ2: How do institutional actors employ visual design, technological display, and framing practices to construct legitimacy, responsiveness, and symbolic authority in Shanghai’s water governance?

• RQ3: How do symbolic strategies—through the integration of spatial design and discursive performance—mediate public trust, regulate civic perceptions, and negotiate state-society relations in Shanghai’s water planning?

Rather than emphasizing operational or technocratic aspects of water governance, this paper centers the lived, perceived, and enacted experiences of water symbolism in everyday urban life. While institutional actors are included in the analysis, the focus lies on how urban residents interact with and interpret the symbolic presence of water infrastructures in their immediate environment. In doing so, this research enriches both theoretical and empirical understandings of symbolic environmental planning and contributes to broader conversations on political ecology, infrastructure studies, and the urban aesthetics of sustainability in contemporary China.

3 Method and materials

3.1 Research design

This study adopts a qualitative research design to investigate the symbolic dimensions of water governance in urban Shanghai. The study analyzes institutional officials’ and everyday residents’ meaning-making processes regarding urban water infrastructure and governance instead of studying only water infrastructure and mechanisms. The research conducted interviews about the symbolic meaning acquisition of water-related spaces and projects and systems that leads to public perception of state legitimacy and spatial identity and state-people relationship and interaction perception. Shanghai plays a leading position in China’s state development initiatives. The study selects Shanghai as its exemplary case because the city has invested heavily in water infrastructure development, projects, and water rehabilitation programs, including hydraulic modernization, ecological restoration, and digital water platforms that combine functional and symbolic goals to showcase state ambitions of modern China showcase. Qualitative methodology was considered most appropriate for this study given the culturally embedded identity formations, emotionally charged, and discursively negotiated processes that needed to be examined through the nature of symbolic urban processes, water design, and urbanization. The research was conducted across key areas in Shanghai between February and July 2024. The data collection included areas along Suzhou Creek, Dianshan Lake, and several other newly updated water plazas and riverfront promenades (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Waterscape Sampling Sites and Representative Typologies in Shanghai. The three selected sites illustrate distinct modes of urban waterscape governance under Shanghai’s “One River, One Creek, One Lake” initiative. Site 1, Mengqing Garden, serves as the flagship demonstration park of the Suzhou Creek rehabilitation project. Site 2, situated along the Xuhui Riverside on the west bank of the Huangpu River, exemplifies large-scale riverfront revitalization and public space renewal. Site 3, located at the midsection of Dianshan Lake’s residential shoreline, represents the suburban and peri-urban interface between water environments and local communities. Collectively, these sites capture the spatial diversity and governance priorities of Shanghai’s contemporary waterscape management. Base map source: Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources (2025).

Given the profoundly symbolic character of urban waterscape governance, in-depth interviews were selected as the methodological tool to uncover the layered meanings, implicit intentions, and affective resonances that are often obscured in policy documents or surface-level design narratives. In the context of Shanghai’s riverfront redevelopment, symbolic constructs such as belonging, legitimacy, and identity frequently reside in everyday perceptions and tacit experiences—dimensions that are not easily accessible through observation or survey-based instruments. Furthermore, the underlying rationale and political intentions behind state-led water initiatives are rarely articulated in explicit terms, often emerging instead through metaphorical expressions or implicit cues in political rhetoric. In-depth interviews created a dialogic space where participants—both planners and residents—could reflect on and articulate their subjective engagement with the evolving riverscape. Notably, such symbolic insights often surfaced only after sustained dialogue, typically in the latter half of each interview, when participants felt relaxed and willing to share deeper, more personal reflections. Growth-role implementers, in particular, tended to initially recall scripted or official narratives before expressing their interpretive views. This method, therefore, aligns closely with the orientation of the study, enabling symbolic dimensions to surface organically through in-depth, situated dialogue and context-sensitive inquiry.

3.2 Participant and sampling rationale

The study collected data through 36 in-depth interviews distributed equally between institutional actors and local residents. Official participants in the study included municipal water officials, district-level officials, as well as state-employed engineers and urban planners who worked on public communication or water project design. The public side of the research involved resident interviews with three groups: elderly citizens who use water areas near rivers, shop owners along rivers, and younger users of waterfront spaces. A purposive sampling method selected participants to obtain diverse viewpoints which also maintained consistent thematic patterns. All interviews were conducted in Mandarin using voice recording devices with the informed consent of participants, lasting for 40–60 min.

This study’s qualitative sampling followed purposeful inclusion criteria grounded in methodological logic, prioritizing symbolic relevance over population representativeness. Rather than aiming for demographic saturation, participants were selected to ensure deep insight into meaning-making processes surrounding urban water governance. Within each stakeholder group, emphasis was placed on participants’ sustained interaction with symbolic water-related spaces. For example, the resident sample included long-term riverside dwellers, small business owners adjacent to revitalized waterways, and frequent users of redeveloped promenades—rather than randomly selected citizens. These individuals commonly engaged with iconic waterfront redevelopment zones such as Suzhou Creek Bay, Xuhui Riverside, Qiantan Waterfront, and Dianshan Lake, which are widely recognized as emblematic sites in Shanghai’s waterscape transformation. Institutional participants were selected based on their direct involvement in planning, design, implementation, or public-facing communication around water governance. This intentional sampling ensured inclusion of participants most familiar with both symbolic and functional aspects of Shanghai’s water infrastructure, thereby supporting theoretical saturation across the study’s core themes. As shown in Table 1, participants represented a diverse set of roles—including technical experts, government officials, academic scholars, and waterfront residents—offering varied yet experientially grounded perspectives on symbolic legitimacy, identity, and spatial belonging within the evolving waterscape. This strategy enabled the study to capture voices most attuned to the nuanced interplay between governance structures and public meaning-making in China’s urban water management context.

3.3 Interview protocol and data collection

The interview protocol was developed to facilitate in-depth, dialogic engagement. Rather than adhering to a rigid questionnaire, the interview guide encouraged open-ended, participant-led conversations that allowed individuals to express their subjective, lived experiences in their own terms. This flexibility was essential for uncovering the symbolic, emotional, and spatial meanings attached to water governance—meanings often invisible in official planning documents or inaccessible through observational techniques. Guided by core research interests such as belonging, identity, symbolic governance, durability, and spatial legitimacy, the interviews evolved iteratively as new themes emerged, consistent with principles of theoretical saturation and constant comparison. Participants were encouraged to reflect on their relationships with rivers or lakes, experiences with recent waterscape developments (e.g., promenades, flood control systems), and their interpretations of the symbolic and institutional permanence of state-led water governance. This dialogic approach was particularly valuable in environments where public narratives around planning rationales are often implicit or metaphorical and where the nuances of perceived belonging or disconnection are best surfaced through extended interpersonal engagement. All interviews were conducted face-to-face or via digital platforms. In accordance with ethical protocols, all interviews were anonymized and processed prior to analysis. Direct identifiers (names, contact info, and project titles) and indirect identifiers were removed to protect confidentiality. Emotional excess, irrelevant tangents, and non-analytical content were also filtered out to refine the corpus for interpretive coding. The cleaned transcripts were then prepared for qualitative analysis under the multi-coding structure informed by the study’s theoretical framework.

3.4 Coding and analytical procedure

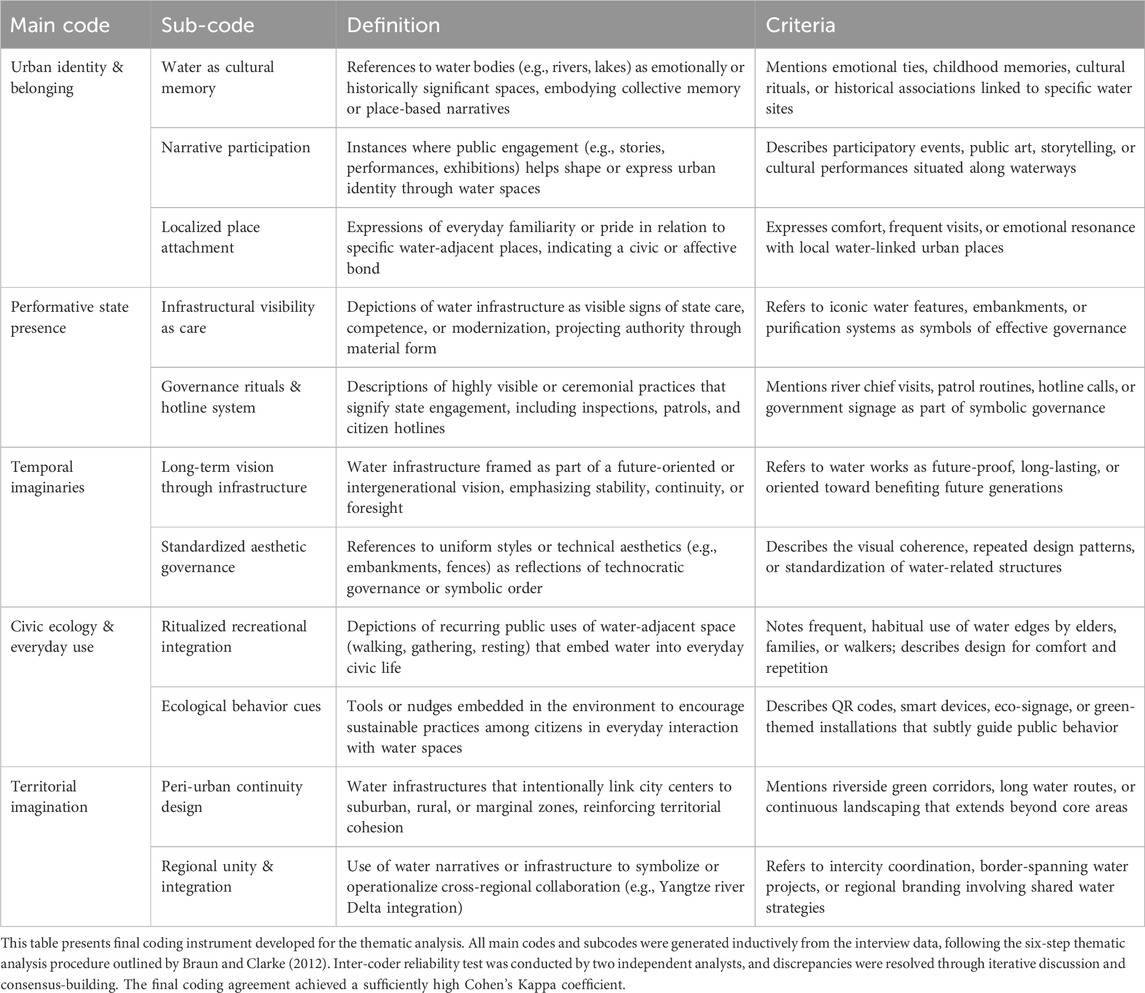

To analyze the interview data, multiple thematic codes were applied to capture the diverse and relevant content expressed by participants. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and fully anonymized to ensure confidentiality. Thematic analysis was conducted using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework: (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) final reporting (Braun and Clarke, 2012). This approach aligned with the study’s orientation and enabled the emergence of both surface-level and latent meanings from participant narratives. An inductive, thematic coding strategy was employed to allow themes to emerge directly from the empirical data, rather than from predefined theoretical constructs. In interpreting symbolic meanings, the researcher acted as an analyst rather than a passive observer. This role required the reflexive capacity to digest fragmented narratives and translate them into higher-order conceptual patterns. Through iterative coding and semantic refinement, narratives regarding subjective experiences were reorganized into analytically coherent categories that preserved their emotional texture while allowing for systematic interpretation. NVivo 14 software was used to manage and analyze the transcripts systematically. Each segment of data was coded using multi-assignment coding, allowing overlapping symbolic meanings to be captured across different themes. To ensure reliability, a second independent coder analyzed a subset of the data using the finalized coding scheme. The resulting Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was 0.83. The coding instrument underwent two rounds of revision before reaching its finalized version (see Table 2).

3.5 Institutional review board statement

This study was granted an exemption in accordance with the “Measures for Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans” (Article 32, Chapter 3) issued jointly by the Chinese Health Commission, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Science and Technology, and the Bureau of Traditional Chinese Medicine (see https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm, accessed on 2 June 2024). Specifically, this study qualifies for exemption condition (2), which applies to research conducted “using anonymized information data” (Guo and Jiao, 2023).

This research presents no more than minimal risk. All identifiers were removed, ensuring the data is fully anonymized and cannot be re-identified. This study was conducted in full accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

4 Result and discussion

The coding of interview data reveals a layered symbolic framework comprising five interrelated dimensions of waterscape symbolism: urban Identity & Belonging, Performative State Presence, Temporal Imaginaries, Civic Ecology & Everyday Use, and Territorial Imagination. As shown in Table 3, the dimension of Urban Identity & Belonging emerges as a dominant thematic cluster, with Water as Cultural Memory coded in 75.0% of cases, followed by Localized Place Attachment (66.7%) and Narrative Participation (55.6%). The second major dimension, Performative State Presence, is marked by high frequencies of Infrastructural Visibility as Care (80.6%) and Governance Rituals & Hotline System (50.0%), indicating how everyday signs of responsiveness contribute to perceptions of attentiveness and legitimacy. Additionally, the dimension of Territorial Imagination—reflected in Peri-Urban Continuity Design (52.8%) and Regional Unity & Integration (41.7%)—captures the emotional and symbolic integration of fringe water zones into the city’s core identity.

Figure 2 visualizes the symbolic system as an interactive circuit centered on the waterscape, mediating exchanges between the state and the public. Through propositional and performative forms of communication, citizens and governing bodies co-construct meanings of belonging and legitimacy. These processes converge around three key domains—Urban Identity, Territorial Imagination, and Performative State Presence—which continually interact and reinforce one another. Furthermore, Performative State Presence bridges short-term practices (e.g., civic ecology and everyday engagement) with long-term visions (e.g., temporal imaginaries of progress and sustainability). These dynamics show how Shanghai’s waterscapes operate as symbolic infrastructures where material design, emotion, and politics converge to shape perceptions of water governance.

Figure 2. Symbolic Dimensions of Water Governance in Shanghai. This conceptual framework depicts the waterscape as a mediating circuit linking governmental and civic actors through three interrelated domains—urban identity, territorial imagination, and Performative State Presence. Together, these domains illustrate how material, aesthetic, and emotional dimensions of infrastructure converge to shape collective perceptions of governance, belonging, and legitimacy in Shanghai’s urban context.

4.1 Urban identity through memory-embedded water infrastructure

Shanghai’s water infrastructure serves as both a utility and a symbolic landscape that continually reshapes urban identity through memory. Rather than serving solely top-down state-led beautification goals (Swyngedouw, 2023), this study reveals how residents reinterpret spaces such as Suzhou Creek and Dianshan Lake as mnemonic anchors, embedding personal and collective memory into the cityscape. These findings challenge binary frameworks that separate state infrastructure from citizen subjectivity (Swyngedouw, 2023) and align with Krause’s (2021) call to view water as a relational and discursive medium. The prevalence of coded themes—Water as Cultural Memory (75.0%), Localized Place Attachment (66.7%), and Narrative Participation (55.6%)—underscores this dynamic. Participants described water not in technocratic terms but as emotionally saturated sites that stabilized identity in a rapidly shifting urban context. These findings build on Pawlik (2020) by emphasizing water’s role in affective continuity and symbolic belonging, positioning it as both infrastructure and cultural interface. By examining how memory sedimentation occurs around these water bodies, this analysis foregrounds the co-production of infrastructure meaning between state and citizen in everyday spatial experience.

Residents’ narratives further illuminate how memory becomes materially embedded in the city through water. One participant shared, “This promenade makes me think of my childhood … the old trees remind me I belong here” (ID17), while another stated, “When I pass by the canal, I feel the city is still alive, still growing, and still remembering us” (ID12). These testimonies portray water not as passive backdrop but as active symbol of generational continuity. For many, infrastructural renewal was emotionally affirming: “When the river was cleaned, we felt the government finally saw our side of the city” (ID09). Memories of intergenerational routines (“It's where my grandparents used to walk after dinner,” ID04), pride in transformation (“I feel proud when I show my children this change,” ID18), and life narrative anchoring (“Every time I walk by, I remember different parts of my life,” ID19) illustrate the emotional-symbolic layering of these spaces. This resonates with Destrée (2022) and with Van Heur et al. (2023), who explore how infrastructure becomes a script of collective belonging. Citizens thus become co-authors of the city’s symbolic texts, transforming memory-laden water infrastructures into civic heritage.

Building on this, the study shows that symbolic legitimacy and emotional attachment are not passively inherited but actively constructed through lived interaction. While Zhang et al. (2025b) frame urban regeneration as a narrative strategy, this research demonstrates that such strategies gain traction only when citizens can infuse their own biographies into the city’s fabric. Participatory design researches demonstrate how the relationship between space and users affects collective identification (Bartomeu and Ventura, 2021; Bartomeu et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025). Rather than merely responding to spatial transformation, residents co-constitute it through memory, pride, and participation. This aligns with Li and Sun’s (2024) view of planning logics as cityscape-as-memory and extends Pastak and Kährik’s (2021) notion of emotional infrastructure by highlighting its bottom-up formation. The findings also engage Pawlik’s (2020) “light heritage,” showing how even mundane features—lamps, trees, railings—can trigger deep emotional ties. These insights foreground how everyday infrastructural interactions become stages for symbolic co-production, creating affective infrastructures that bind citizens to place. Ultimately, this study reframes water as a socio-symbolic medium through which urban identity, belonging, and legitimacy are materially and emotionally negotiated.

4.2 Performative governance through infrastructural visibility and affective functionality

This study reveals that Shanghai’s water infrastructure plays a crucial role in performing state care through visible, emotionalized routines. Rather than being merely technocratic, the infrastructure operates as a stage for subtle state presence—what Dicarlo (2024) termed “infrastructure as spectacle”—but here, the spectacle is affective rather than authoritarian. The prevalence of codes such as Infrastructural Visibility as Care (80.6%) and Governance Rituals & Hotline System (50.0%) indicates that routine acts—repair visibility, signage, park maintenance, or hotline responsiveness—are interpreted by residents as signs of attentiveness. This finding reorients the perception of Chinese infrastructure governance away from pure opacity (Dicarlo, 2024; Hu et al., 2024) toward a new paradigm of affective proximity. Through repeated micro-interventions, the state cultivates a soft aesthetic of presence, recognition, and care. Such practices transform infrastructure into a communicative device, an interface where citizens feel morally rewarded, seen, and included. These findings align with the theory of symbolic capital (Van Heur et al., 2023) and the concept of visual legitimacy (Dicarlo, 2024), while extending them by showing that emotional legitimacy emerges not from grandeur but from accumulated, small-scale, embodied gestures of care.

Interview data underscore this affective functionality of water governance, as residents frequently linked infrastructural visibility to emotional reassurance, interpreting clean canals, responsive hotlines, and informational signage as indicators of being heard and cared for. As one participant noted, “They put up signs to explain the project. It is not just concrete—it is like they want us to understand and be part of it” (ID12), framing signage as inclusive symbolism. Another stated, “We called the water hotline last summer and they came the next morning. It made me feel like someone out there actually listens” (ID30), emphasizing reciprocity and trust. These insights build on Nashirudin et al. (2025) emphasis on digital transparency by showing how the performance of responsiveness fosters emotional legitimacy. Rather than acting through policy documents or propaganda alone, the state materializes attentiveness through embodied acts that are mundane yet symbolically powerful. This subtle infrastructure of care embodies moral inclusion, fostering citizen trust beyond the reach of traditional governance models.

These findings advance urban governance theory by revealing how infrastructural aesthetics and symbolic interaction co-produce affective statehood. Drawing on Dobbin and Smith (2021), this study demonstrates that the performance of care via infrastructure reduces trust gaps by transforming governance into something seen, felt, and reciprocated. Rather than positioning the state as a distant planner or enforcer, infrastructural routines—cleaning, maintenance, signage—serve as visual dialogues through which the state communicates its presence. This builds on Lan et al. (2024) by shifting focus from policy rhetoric to infrastructure as a performative agent in the aestheticization of Chinese governance. The emotionally charged presence of late-night maintenance crews, water trucks, and hotline responses redefines infrastructure as affective interaction rather than mere public utility. This “micro-attentiveness,” expressed through repeated symbolic acts, constitutes a form of procedural legitimacy (Ruder and Woods, 2020), rendering governance experientially participatory even without formal channels. In turn, it broadens the political imaginary, where legitimacy arises not from outcomes or elections but from routine, embodied gestures of care embedded in the city’s material fabric.

4.3 Territorial Re-anchoring through peri-urban water symbolism

The third major analytical insight reveals how Shanghai’s water governance engages in a symbolic reframing of peri-urban landscapes, repositioning sites like Dianshan Lake not as functional peripheries but as emotionally significant zones of city identity. Statistical coding for Peri-Urban Continuity Design (52.8%) and Regional Unity & Integration (41.7%) points to an intentional emotional rescaling. This reframing moves beyond infrastructural inclusion to emotional integration, redefining Shanghai’s spatial limits through symbolic attachment. Rather than treating peri-urban areas as marginal overflow territories, the city incorporates them into a broader mnemonic and aesthetic order, aligning with the notion of “aesthetic governmentality” (He and Qian, 2023) but extending it laterally across space. Interviewees described these areas as more than leisure spaces—affective reflections of Shanghai’s evolving self-image, or “Shanghai’s little Europe,” as one participant noted (ID17). These accounts show that infrastructure functions as both connective and symbolic, generating soft pride and emotional continuity that reinforce governance legitimacy at the city’s periphery.

This symbolic integration reconfigures peri-urban areas from passive administrative boundaries into active mnemonic sites, where pride, memory, and emotional identification are mobilized for territorial cohesion. Participants described how water infrastructure in Qingpu or lakeside promenades around Dianshan Lake made them “feel part of the same story” (ID05), suggesting that spatial legitimacy is being cultivated through narrative and affect. Instead of relying solely on zoning or development plans, Shanghai’s strategy engages emotional geographies to foster long-term identity formation. This extends Mager and Wagner’s (2022) view on cultural infrastructure, emphasizing how place-making at the edges becomes a form of symbolic governance. It adds a lived sophistication to Dicarlo’s (2024) account of technocratic legitimacy by showing how visual-symbolic governance now targets peripheral zones to construct emotional inclusion. In doing so, the city reframes its periphery as internal, constructing a psychological map where formerly marginal zones become emotionally central to the urban imaginary.

This shift toward symbolic peri-urbanism adds critical nuance to theories of territorial restructuring by infusing them with emotional content. While Su (2022) emphasizes the administrative and strategic manipulation of space, this study foregrounds how water-related aesthetics, memory, and affect serve as technologies of symbolic anchoring. Residents’ expressions of pride in regional beautification or emotional return to childhood landscapes demonstrate that legitimacy is co-produced through spatial storytelling. These findings enrich Ruder and Woods (2020) discussion and connect to the warning that symbolic governance must be experientially grounded to avoid fragility. By foregrounding landscape design, memory cues, and emotional resonance, Shanghai’s governance transforms peripheral water bodies into civic rituals of belonging. Consistent with Sun (2025a); Sun (2025b) and Sun et al. (2025) and Zhang et al. (2025a), this approach reflects a broader shift toward emotional identification across spatial distances, where symbolic peripheries become legitimacy frontiers rather than governance voids. Through these practices, Shanghai advances not only spatial integration but also an affective re-territorialization of its urban future.

4.4 Between function and symbol: comparative analysis of Suzhou Creek and Dianshan Lake

Water infrastructure in Shanghai is more than a utility system; it anchors identity memory and shared urban belonging. Residents and water governance actors alike recall Suzhou Creek’s transformation from industrial degradation to ecological renewal as a symbolic journey. Official slogans such as “mother river” evoke a moral narrative of redemption, while residents ground such phrases in lived memory. This symbolic infrastructure operates as more than a restored landscape—it serves as a medium of emotional continuity, connecting past pollution to present pride. Through everyday uses—walking paths, bird-watching, or storytelling—citizens embed these changes within personal and collective histories. These memory-laden spaces sustain a place-based identity shaped by environmental transformation, echoing Cankurt Semiz and Özsoy (2024) notion of urban memory and Foucault’s idea of spatial inscription (Musa, 2025).

Governance visibility operates performatively, embedding power in both policy and the aesthetic-symbolic presence of infrastructure. Along Suzhou Creek, visual elements such as QR codes, slogans, and landscaped signage function as communicative devices. These reflect Leclercq-Vandelannoitte’s (2021) argument that visibility performs authority, especially when symbolic infrastructure becomes a site of staged responsiveness. State actors emphasized such visibility as essential to fulfilling service duties and building legitimacy. Meanwhile, residents interpreted it variably—as either accountability or image management—highlighting the polysemy of performative governance. This dual visibility reinforces symbolic legitimacy through a reciprocal loop: The state projects a caring presence, while the public receives, negotiates, and at times contests it. Echoing Aykut et al. (2021), this performativity anchors authority in both action and appearance.

These symbolic mechanisms are embedded within a broader territorial imagination that frames Shanghai’s waterscapes as representations of regional identity. Suzhou Creek is discursively imagined as Shanghai’s “living room,” emphasizing global competitiveness and urban integration. Through landscape design, thematic zoning, and public discourse, water infrastructure is re-situated as part of a collective vision of spatial centrality. This aligns with Zou (2022) notion of spatial fix and Afra and Justus (2024) concept of infrastructural imaginaries. In contrast, Dianshan Lake’s symbolism is more subdued—framed around ecological value, tourism, and peri-urban planning. Despite similar goals of ecological restoration, Suzhou Creek’s symbolic infrastructure is actively cultivated, while Dianshan Lake’s is still emergent. This differential symbolic loading reflects uneven urban centrality and political visibility. Both, however, contribute to Shanghai’s spatial narrative—one through consolidated spectacle, the other through latent potential.

A comparative analysis between Suzhou Creek and Dianshan Lake illustrates how symbolic and functional water governance diverge. Suzhou Creek spans 53 km through eight districts and completed a 42-km accessible riverfront by 2020. Each district emphasized distinct themes—heritage (Jingan), ecology (Minhang), sports (Putuo)—generating a corridor of symbolic infrastructure. Dianshan Lake, though Shanghai’s largest natural lake, remains governed solely by Qingpu District. As of 2022, only 13.3 of its 31-km shoreline had been opened, with its second restoration phase incomplete by 2025. Unlike Suzhou Creek, which emphasizes people-water intimacy and identity-making, Dianshan Lake’s restoration emphasizes ecological engineering, water quality, and habitat integrity. Yet, elements like the Rainbow Bridge and public signage suggest gradual symbolic integration. This contrast underscores different governance rhythms and territorial identities—central symbolic performance versus peri-urban ecological development—reflecting the distinction between place attachment and functional space (Smith and Aranha, 2022).

Underlying these dynamics is a tension between projected legitimacy—the state’s strategic symbolic efforts—and perceived legitimacy—the public’s reception of these symbols. Rather than viewing them as distinct, this study situates them within a single symbolic loop: the state projects authority and benevolence through slogans, signage, and design, while the public receives, interprets, and sometimes contests these signals. Interview narratives reveal both acceptance and skepticism toward visual cues like “People’s City for the People,” confirming the interplay of intentional projection and citizen decoding. This mirrors Paul and Pål (2025) insight that symbols are politically ambiguous and powerfully malleable. Our study thus contributes to the understanding of symbolic governance as a mutually constitutive process, where legitimacy is performed, read, and recirculated through the aesthetics and presence of infrastructure. This mechanism is captured in the proposed visual model (see Figure 2), which represents the cyclical interaction between symbolic projection and citizen perception. It shows how water infrastructure acts simultaneously as a policy tool, a communicative medium, and a symbolic site of legitimacy construction. The state’s thematic strategies—explicit policy texts and slogans—interact with more abstract symbolic strategies: metaphors, aesthetic cues, and territorial signifiers. These two modes reinforce each other, producing a layered communicative governance that enables the public to internalize and respond to urban visions. This clarifies that legitimacy in this paper refers to both projected and perceived legitimacy—not as binary opposites but as co-produced facets of symbolic urban governance.

4.5 Counter-narratives and the limits of symbolic governance

Despite the appeal of symbolic infrastructure in constructing collective identity, performative legitimacy, and territorial imagination, its critiques must be addressed. Scholars have long cautioned against the reliance on symbolic politics that prioritize spectacle over substance. As Boussaguet and Faucher (2020) observed, symbolic actions often provide reassurance without delivering material benefits. Ramoglou et al. (2024) further argue that such policies tend to be performative, articulating grand ambitions without ensuring the means to realize them. In the context of urban ecological planning, this critique resonates with concerns over whether water infrastructure truly facilitates sustainable transformation or simply projects an illusion of it. Dzhurova (2020) similarly frames symbolic governance as discursive substitution—a form of meaning-making that replaces genuine deliberation with strategic performativity. These critiques underscore the risk that symbolic water projects may serve more as political theater than substantive governance.

Such skepticism is especially pronounced in environmental governance, where symbolic strategies often serve to appease international audiences or satisfy domestic stakeholders, rather than drive transformative change. These symbolic gestures, while rhetorically powerful, may fall short when evaluated against their operational outcomes—posing a critical challenge to governance legitimacy. Truong et al. (2021) highlight that symbolic environmental actions negatively affect reputation, while substantive actions improve a firm’s reputation. Nawaz et al. (2025) note that symbolic efforts heighten perceptions of organizational hypocrisy, while substantive ones bolster perceptions of leader integrity. While the aestheticization and storytelling of water infrastructure may foster belonging or pride, they risk masking unresolved structural and ecological problems, especially when designed to divert attention from institutional inaction.

Yet, citizens may derive psychological satisfaction from symbolic interventions because they fulfill a need to believe that problems are being addressed—even when material results are lacking (Aliza and Itai, 2024). The symbolic policy, as Boussaguet and Faucher (2025) argue, is not intrinsically superficial but becomes problematic when it displaces meaningful action. This highlights a paradox: even as symbolic governance is critiqued for its superficiality, it continues to function because it satisfies latent societal desires for reassurance and cohesion in uncertain times. Foucault reminds us that space is never neutral; it is both the medium and message of governance (Musa, 2025).

Recognizing these counter-narratives does not negate the value of symbolic infrastructure—rather, it strengthens the rationale for studying it. This research does not seek to isolate symbolic governance as either effective or deceptive. Instead, it situates symbolic water infrastructure within a continuum that includes both projected legitimacy (from the state) and perceived legitimacy (from the public), acknowledging the tensions and mutual feedback between them. By incorporating frontline implementers’ experiences alongside residents’ narratives, this study engages how state-led water projects are interpreted or appropriated at the symbolic level. The coexistence of aesthetic design and ecological utility, ritual performance and community identity, makes water governance an ideal site to understand the layered interplay between politics, affect, and spatial imaginaries. Even amid critique, these projects remain significant because they continue to shape how urban communities understand nature, governance, and themselves.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that water infrastructure in Shanghai operates far beyond its technical or aesthetic roles; it functions as a deeply symbolic medium through which urban identity, governance legitimacy, and territorial cohesion are constructed, experienced, and emotionally negotiated. Grounded in 36 in-depth interviews and systematic thematic coding following Braun and Clarke’s framework, the analysis provides robust qualitative evidence—supported by quantitative prevalence indicators—that symbolic infrastructures profoundly shape how residents understand and perceive the presence of the state. First, 75.0% of participants described embedding biographical memory and collective belonging into regenerated rivers, lakes, and canals. These waterscapes therefore serve as mnemonic anchors that stabilize identity amid rapid urban transformation, showing that citizens do not passively receive infrastructure but actively interpret and internalize it. Second, 80.6% of interviewees emphasized the materialized visibility of governance—expressed through maintenance rituals, signage, inspection routines, and hotline responsiveness—as a performative aesthetic of care. These emotionally resonant gestures reinforce state authority not through coercion but through symbolic attentiveness, extending current theories of affective governance. Third, 52.8% of the participants highlighted how formerly peripheral water zones have become emotionally internalized as part of Shanghai’s symbolic core. This re-territorialization reflects a shift from functional management to spatially distributed symbolic governance, illustrating how peri-urban landscapes are reimagined as integral to city identity.

Together, these findings underscore that water infrastructure in Shanghai may operate simultaneously as a material system, a cultural signifier, and a political instrument. As a material system, water infrastructure includes canals, pipelines, eco-corridors, and digital networks that physically regulate flow, drainage, and ecological stability; these technical functions provide the baseline through which residents encounter the state’s capacity to manage urban life. As a cultural signifier, regenerated waterscapes carry symbolic weight by encoding local memory, collective identity, and aesthetic meaning: residents attach personal histories to familiar riverbanks, interpret maintenance rituals as cues of civic care, and view restored waterways as visual narratives of Shanghai’s modernity. As a political instrument, water infrastructure becomes a medium through which the state performs attentiveness and competence—ritualized cleaning routines, signage, and responsiveness to hotline requests operate as low-intensity but emotionally resonant gestures that materialize governance within everyday environments. These functions are co-produced through continuous interaction between state strategies—including ecological restoration, territorial branding, and maintenance regimes—and citizen subjectivity, as individuals interpret these interventions through personal memory, aesthetic preference, and emotional responses to space. This interplay reveals how legitimacy emerges from official narrative while additionally from how residents perceive and experience infrastructural care in their daily routines. By demonstrating this dynamic, the study advances debates in political ecology interrogating increasingly how environmental infrastructures encapsulate power relations, as well as urban design questioning fundamentally how spatial aesthetics are mobilized to cultivate public consent. This study illuminates that legitimacy in contemporary China is not anchored solely in institutional propaganda but is constructed through emotionally charged, symbolically layered, and spatially embedded practices that allow the state to become experientially present in citizens’ everyday lives.

Despite the study’s methodological rigor, limitations must be acknowledged to clarify the analytical boundaries. First, although the qualitative sampling included a diverse mix of residents, frontline water-management personnel, and individuals with varying degrees of proximity to Shanghai’s waterfronts, the overall sample size remains modest (n = 36) and geographically concentrated. Because the interviews were conducted in specific regenerated waterfront sites—rather than across the full spectrum of Shanghai’s urban, suburban, and exurban hydrological zones—the symbolic interpretations captured reflect localized forms of meaning-making shaped by the cultural, aesthetic, and historical specificities of these sites. This creates a depth–breadth trade-off: while the qualitative approach provides rich insight into how individuals embed memory, perceive governance, and emotionally territorialize waterscapes, the findings cannot be generalized statistically to the entire metropolitan region. Second, this spatial concentration limits the applicability of the results to the broader Chinese context. Shanghai, as a megacity with advanced ecological restoration programs, strong institutional capacity, and high public visibility of water-related governance, may not represent the conditions of smaller cities, resource-constrained municipalities, or rural catchments, where infrastructural symbolism and state–citizen interactions may be structured by different sociopolitical ecologies. These contextual limits suggest the need for comparative, cross-scalar research across China’s diverse water governance landscapes. Future studies could investigate how symbolic water governance operates across urban, peri-urban, and rural settings, exploring whether infrastructural visibility and symbolic territorialization function similarly or diverge across socio-spatial contexts.

A further limitation concerns the scope of voices captured in the dataset. While the study includes residents and implementers directly engaged with the water system, it does not systematically incorporate marginalized perspectives—such as the urban poor or rural migrants. These groups may articulate alternative symbolic interpretations or challenge state-led aesthetic narratives, offering critical insights into the contested dimensions of water governance. A second area for development involves the temporal dynamics of symbolic meaning: because the study relies on interviews conducted at a single moment, it cannot fully track how perceptions evolve as infrastructure ages, policies shift, or ecological interventions undergo public scrutiny. Integrating media analysis, digital ethnography, and long-term public opinion data would allow future research to trace how symbolic meanings circulate, stabilize, or fracture within public discourse. Those future directions would help illuminate the broader socio-political ecology of water governance and deepen understanding of how symbolic infrastructures shape legitimacy, identity, and everyday urban experience across China.

Nevertheless, this study advances existing scholarship by demonstrating how water infrastructure in Shanghai moves beyond its material and ecological roles to become a central medium through which identity, legitimacy, and governance are co-produced. It shows how residents embed biographical memory and place attachment into regenerated waterscapes, turning restored riverbanks and canals into emotional anchors that stabilize personal identity amid rapid urban change. It further explains how governance legitimacy is cultivated through symbolic practices—such as ritualized maintenance, visible inspection routines, and hotline responsiveness—that allow citizens to feel state care as an everyday, embodied experience rather than merely hear it through official discourse. By connecting political ecology with urban design and governance studies, the research illustrates why affective narratives, public rituals, and infrastructure aesthetics function as a dialogical interface: they create repeated moments of encounter where citizens interpret state presence through sensory cues, emotional responses, and perceived attentiveness, thereby transforming infrastructure into a lived communicative process. Besides, this study provides concrete value for urban governance and environmental policy. For water authorities, the findings clarify which specific practices—e.g., consistent maintenance visibility and aesthetic coherence in design—most effectively build public trust. For planners, the results demonstrate why integrating symbolic and affective elements into waterfront redevelopment strengthens civic attachment and fosters long-term stewardship. For cultural-environmental policymakers, the study highlights how infrastructure aesthetics and public rituals operate as soft governance tools, subtly shaping political legitimacy without explicit propaganda. Together, these contributions offer a precise, actionable understanding of how symbolic infrastructures influence urban experience and state–society relations in contemporary China.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Chinese Health Commission, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Science and Technology, and the Bureau of Traditional Chinese Medicine (see (https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm), accessed on 2 June 2024). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. PH: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research is funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (25CXW025).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2025.1666629/full#supplementary-material

References

Adams, E. A., Zulu, L., and Ouellette-Kray, Q. (2020). Community water governance for urban water security in the global south: status, lessons, and prospects. WIREs Water 7 (5), e1466. doi:10.1002/wat2.1466

Afra, F., and Justus, U. (2024). The politics of drains: everyday negotiations of infrastructure imaginaries in Accra. Urban Stud. 61 (11), 2099–2117. doi:10.1177/00420980241230432

Alda-Vidal, C., Lawhon, M., Iossifova, D., and Browne, A. L. (2023). Living with fragile infrastructure: the gendered labour of preventing, responding to and being impacted by sanitation failures. Geoforum 141, 103724. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2023.103724

Aliza, F.-R., and Itai, B. (2024). Descriptive and symbolic: the connection between political representation and citizen satisfaction with municipal public services. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 54 (1), 3–18. doi:10.1177/02750740231187539

Alvarado, N. A. (2025). Urban infrastructure and migrant citizenships: notes towards migrant-state relations in the urban peripheries. Environ. Plan. C Polit. Space 43 (6), 1053–1069. doi:10.1177/23996544241312886

Aykut, S. C., Morena, E., and Foyer, J. (2021). ‘Incantatory’ governance: global climate politics’ performative turn and its wider significance for global politics. Int. Polit. 58 (4), 519–540. doi:10.1057/s41311-020-00250-8

Bartomeu, E., and Ventura, O. (2021). Participatory practices for co-designing a multipurpose family space in a children's hospital. Des. Health 5 (1), 26–38. doi:10.1080/24735132.2021.1908654

Bartomeu, E., Oliva, R., Huertas, S., Soriano, D., Steegmann, D., and Ventura, O. (2022). Espacio-plataforma: creación de espacios para nuevas colectividades: interacciones entre usuarios y entorno. Available online at: https://diposit.eina.cat/handle/20.500.12082/1084

Bhalla, S. (2024). How water sector reforms institutionalised domination and repression in Tunisia’s authoritarian regimes. Environ. Plan. C Polit. Space 43 (4), 746–764. doi:10.1177/23996544241285647

Bischoff-Mattson, Z., Maree, G., Vogel, C., Lynch, A., Olivier, D., and Terblanche, D. (2020). Shape of a water crisis: practitioner perspectives on urban water scarcity and ‘Day Zero’ in South Africa. Water Policy 22 (2), 193–210. doi:10.2166/wp.2020.233

Boelens, R., Escobar, A., Bakker, K., Hommes, L., Swyngedouw, E., Hogenboom, B., et al. (2023). Riverhood: political ecologies of socionature commoning and translocal struggles for water justice. J. Peasant Stud. 50 (3), 1125–1156. doi:10.1080/03066150.2022.2120810

Boussaguet, L., and Faucher, F. (2020). Beyond a “gesture”: the treatment of the symbolic in public policy analysis. Fr. Polit. 18 (1), 189–205. doi:10.1057/s41253-020-00107-9

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic analysis,” in APA handbook of research methods in psychology, vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. (Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association), 57–71.

Cankurt Semiz, S. N., and Özsoy, F. A. (2024). Transmission of spatial experience in the context of sustainability of urban memory. Sustainability 16 (22), 9910. doi:10.3390/su16229910

Chang, Y.-J., and Zhu, D. (2020). Urban water security of China’s municipalities: Comparison, features and challenges. J. Hydrology 587, 125023. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125023

Chen, T., and Zang, T. (2021). Countermeasures and prospects for the development of urban design in China in the period of new urbanization. Eco Cities 2, 11. doi:10.54517/ec.v2i2.1859

Connolly, C. (2019). Urban political ecology beyond methodological cityism. Int. J. Urban Regional Res. 43 (1), 63–75. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12710

Den Hartog, H. (2021). Engineering an ecological civilization along Shanghai’s main waterfront and coastline: evaluating ongoing efforts to construct an urban eco-network. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 639739. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.639739

Destrée, P. (2022). Contentious connections: infrastructure, dignity, and collective life in Accra, Ghana. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 28 (1), 92–113. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.13654

DiCarlo, J. (2024). “Behind the spectacle of the belt and road initiative: corridor perspectives, In/visibility, and a politics of sight,” in Seeing China's belt and road (Oxford University Press).

Dobbin, K. B., and Smith, D. W. (2021). Bridging social capital theory and practice: evidence from community-managed water treatment plants in Honduras. J. Rural Stud. 88, 181–191. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.10.002

Dzhurova, A. (2020). Symbolic politics and government response to a national emergency: narrating the COVID-19 crisis. Adm. Theory & Praxis 42 (4), 571–587. doi:10.1080/10841806.2020.1816787

Ernstson, H., and Swyngedouw, E. (2018). Urban political ecology in the anthropo-obscene: interruptions and possibilities. London: Routledge.

Feng, S., and Yamamoto, T. (2020). Preliminary research on sponge city concept for urban flood reduction: a case study on ten sponge city pilot projects in Shanghai, China. Disaster Prev. Manag. 29 (6), 961–985. doi:10.1108/DPM-01-2020-0019

Gandy, M. (2021). Urban political ecology: a critical reconfiguration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 46 (1), 21–43. doi:10.1177/03091325211040553

Guo, W. K., and Jiao, F. (2023). Notice on issuing the measures for ethical review of life science and medical research involving human subjects. Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm.

He, S., and Qian, J. (2023). Police and politics in aesthetics-based urban governance: redevelopment and grassroots struggles in Enninglu, Guangzhou, China. Antipode 55 (3), 853–876. doi:10.1111/anti.12919

Hommes, L., Rutgerd, B. M. H. L., and Veldwisch, G. J. (2019). Rural–urban water struggles: urbanizing hydrosocial territories and evolving connections, discourses and identities. Water Int. 44(2), 81–94. doi:10.1080/02508060.2019.1583311

Hu, Z., Wu, G., Wang, H., and Qiang, G. (2024). Dynamics in network governance of infrastructure public-private partnerships: evidence from four municipalities of China. Public Manag. Rev. 26 (11), 3126–3150. doi:10.1080/14719037.2023.2206844

Hurst, E., Ellis, R., and Karippal, A. B. (2022). Lively water infrastructure: constructed wetlands in more-than-human waterscapes. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 8 (1), 77–99. doi:10.1177/25148486221113712

Ji, J. (2024). Shanghai's changning district has improved the landscape along the Suzhou Creek, creating a pedestrian walkway that stretches for over ten kilometers. Beijing, China: People's Daily.

Jiang, Y., Shi, T., and Gu, X. (2016). Healthy urban streams: the ecological continuity study of the Suzhou creek corridor in Shanghai. Cities 59, 80–94. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.06.002

Joshua, J. C. (2020). Malleable infrastructures: crisis and the engineering of political ecologies in Southern California. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 3 (3), 927–949. doi:10.1177/2514848619893208

Kaika, M., Keil, R., Mandler, T., and Tzaninis, Y. (2023). Turning up the heat: urban political ecology for a climate emergency. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press.

Lan, X., Ku, H. B., and Zhan, Y. (2024). Aesthetic governance and China's rural toilet revolution. Dev. Change 55 (2), 219–243. doi:10.1111/dech.12823

Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, A. (2021). “Seeing to be seen”: the manager’s political economy of visibility in new ways of working. Eur. Manag. J. 39 (5), 605–616. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2020.11.005

Li, B. (2018). Water and the history of China. Soc. Sci. China 39 (1), 120–131. doi:10.1080/02529203.2018.1414413

Li, H., and Sun, S. (2024). Exploration of the European agrivoltaics landscape in the context of global climate change. E3S Web Conf. 520, 02013. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202452002013

Li, M., Finlayson, B., Webber, M., Barnett, J., Webber, S., Rogers, S., et al. (2017). Estimating urban water demand under conditions of rapid growth: the case of Shanghai. Reg. Environ. Change 17 (4), 1153–1161. doi:10.1007/s10113-016-1100-6

Li, H., Sun, S., Bartomeu-Magaña, E., and Wei, X. (2025). Determinants of community-based home care service demand among urban older adults in Shanxi, China: a cross-sectional psychological perspective. Front. Public Health 13, 1645632. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2025.1645632

Liu, G., and Zhang, F. (2022). Inequality of household water footprint consumption in China. J. Hydrology 612, 128241. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128241

Loftus, A. (2019). Political ecology III: who are ‘the people. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 44 (5), 981–990. doi:10.1177/0309132519884632

Mager, C., and Wagner, M. (2022). Kulturelle Infrastrukturen in deutschen Klein-und Mittelstädten. Eine Typisierung der Standortgemeinschaften von Einrichtungen der kulturellen Daseinsvorsorge. Raumforschung und Raumordnung | Spatial Res. Plan. 80 (4), 379–396. doi:10.14512/rur.92

Martinez, R. (2022). Urban water governance as policy boosterism: seoul’s legitimation at the local and global scale. Urban Stud. 60 (2), 325–342. doi:10.1177/00420980221097500

Meng, F., Guo, J., Guo, Z., Lee, J. C., Liu, G., and Wang, N. (2021). Urban ecological transition: the practice of ecological civilization construction in China. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142633. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142633

Musa, M. (2025). Space in Michel Foucault’s work and its intersection with Henry Lefebvre’s production of space. HBRC J. 21 (1), 353–375. doi:10.1080/16874048.2025.2503525

Nashirudin, M., Razali, R., and Ulfah, A. K. (2025). Modernizing zakat and Waqf management in Indonesia: a legal and governance perspective. Mazahib 24 (1), 198–220. doi:10.21093/mj.v24i1.9419

Nawaz, A., Soomro, S. A., and Talpur, Q.-u.-a. (2025). Environmental actions and leadership integrity: unpacking symbolic and substantive pro-environmental behavior impact on organizational perception. Bus. Ethics, Environ. & Responsib., beer.12777. doi:10.1111/beer.12777

Niranjana, R. (2022). An experiment with the minor geographies of major cities: infrastructural relations among the fragments. Urban Stud. 59 (8), 1556–1574. doi:10.1177/00420980221084260

Pastak, I., and Kährik, A. (2021). Symbolic displacement revisited: place-making narratives in gentrifying neighbourhoods of Tallinn. Int. J. Urban Regional Res. 45 (5), 814–834. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.13054

Paul, B., and Pål, R. (2025). Status symbols in world politics. Coop. Confl. 60 (1), 3–26. doi:10.1177/00108367241311072

Pawlik, K. (2020). Illuminating Shanghai: light, heritage, power. Pol. Political Sci. Yearb. 49, 54–74. doi:10.15804/ppsy2020304

Perreault, T. (2017). “What kind of governance for what kind of equity? Towards a theorization of justice in water governance,” in Hydrosocial territories and water equity. Editors R. Boelens, B. Crow, J. Hoogesteger, F. E. Lu, E. Swyngedouw, and J. Vos 1st Edition (London: Routledge), 13.

Ramoglou, S., Jayasekera, R., and Soobaroyen, T. (2024). Do policymakers mean what they say? Symbolic pressures and the subtle dynamics of the institutional game. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 39 (2), 290–311. doi:10.5465/amp.2023.0030

Ricart, S., Kirk, N., and Ribas, A. (2019). Ecosystem services and multifunctional agriculture: unravelling informal stakeholders' perceptions and water governance in three European irrigation systems. Environ. Policy Gov. 29 (1), 23–34. doi:10.1002/eet.1831

Ruder, A. I., and Woods, N. D. (2020). Procedural fairness and the legitimacy of agency rulemaking. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 30 (3), 400–414. doi:10.1093/jopart/muz017