- 1Jiangxi Institute of Red Soil and Germplasm Resources, Nanchang, China

- 2Soil and Fertilizer Research Institute, Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences/Key Laboratory of Nutrient Cycling and Resource Environment of Anhui Province, Hefei, China

- 3State Grid Shaanxi Electric Power Co., Ltd., Xi’an, China

- 4Beijing Jingneng International Holdings Co., Ltd., Hohhot, China

Climate change is significantly increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events (EWEs), including severe storms, catastrophic floods, prolonged heatwaves, and extended droughts. These events have significant impacts on hydrological systems, microbial ecosystems, and public health. Therefore, this detailed review was carried out to explore the impact of climate change induced extreme weather events on microbial contamination and public health. The detailed search revealed that EWEs can lead to increased microbial contamination in water sources, potentially causing outbreaks of waterborne diseases. In addition, EWE can also disrupt nutrient cycles and alter microbial community structures, affecting ecosystem stability and resilience. Moreover, EWEs can mobilize pollutants such as microplastics, antibiotic-resistant genes, and PFAS, further degrading water quality. Despite these challenges, microbial communities can play a crucial role in mitigating the impacts of EWEs by degrading pollutants and stabilizing nutrient cycles. In addition, we found that real-time monitoring techniques, such as environmental DNA (eDNA) profiling, can help identify contamination sources and inform targeted interventions. At last, we observed that integrating microbial insights into ecosystem management and public health strategies is essential for developing resilient and adaptive approaches to address the escalating impacts of climate change on water quality and public health. Therefore, this study is particularly important in highlighting its contribution to the development of more effective and resilient management practices in the face of increasing climate variability.

1 Introduction

Climate change is significantly increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events (EWEs), including droughts, floods, heatwaves, and extreme rainfall. These events profoundly impact both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, leading to cascading effects across different trophic levels (Table 1) (Anufriieva and Shadrin, 2018; Klatt et al., 2022; Sim et al., 2025). The intensified effects of climate change are particularly evident in altered precipitation patterns and increasing temperatures, which significantly affect the health and stability of various ecosystems (Alonso and Clark, 2015; Fuhrer, 2006; Garg et al., 2025). Understanding the intricate relationship between climate change and extreme weather events is crucial for predicting and mitigating their impacts on ecological systems (Furtak and Wolińska, 2023).

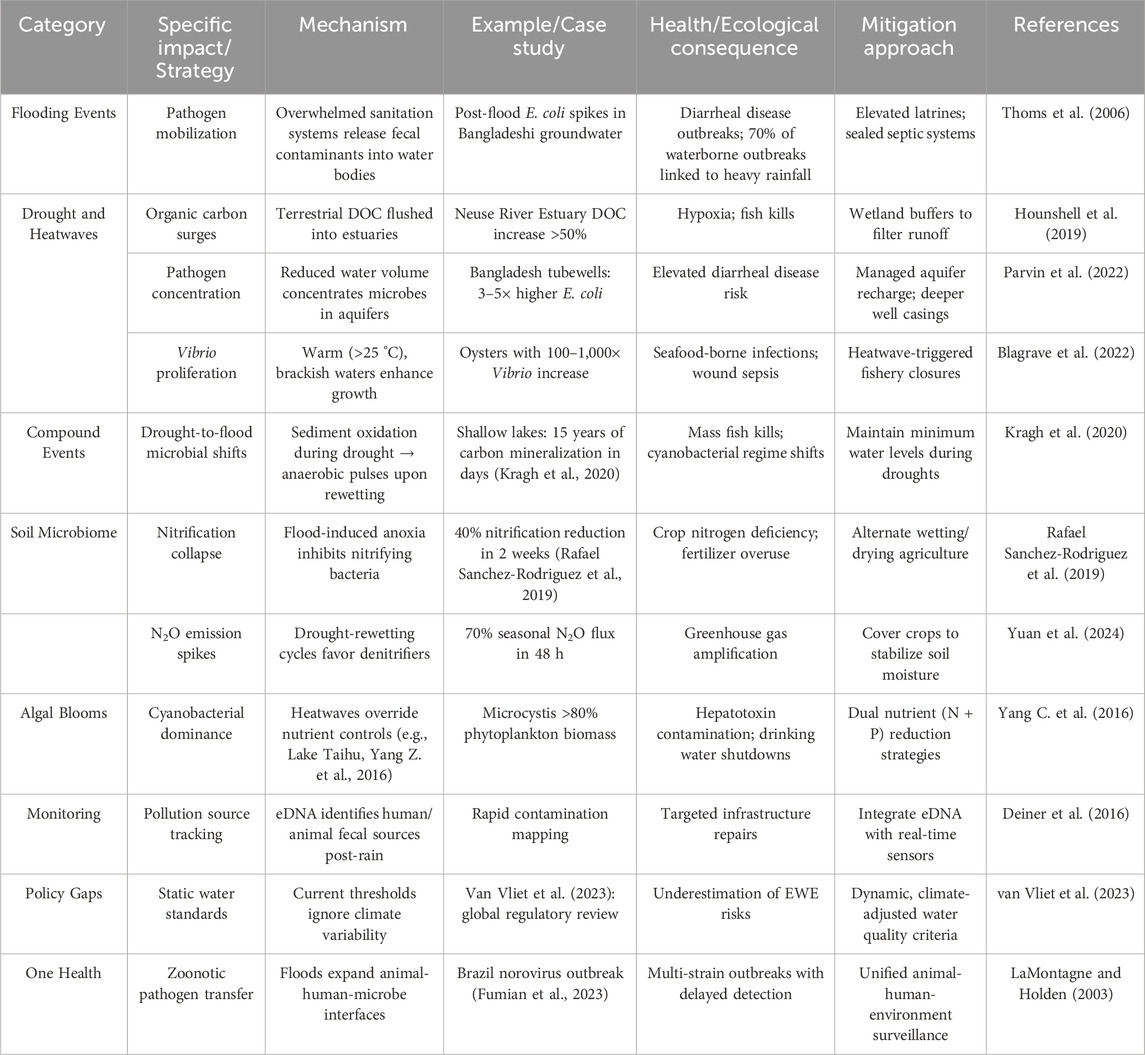

Table 1. Summarizing the extreme events, their potential impact and mechanisms as well as the mitigation approaches.

In ecological ecosystems, microbial communities play a pivotal role in mediating ecosystem responses to EWE (Das et al., 2019; Muhammad et al., 2024). Ecological functional microorganisms are essential for nutrient cycling, decomposition, and maintaining soil and water quality (Hallsworth, 2022; Krueger et al., 2021). EWE can cause changes in these microbial composition and activity, and can significantly influence the biogeochemical processes that govern ecosystem functions. For instance, several studies reported that EWE can alter soil moisture and temperature, leading to shifts in microbial community structure and function, which in turn affects carbon and nitrogen cycling (Ahmad et al., 2022; Das et al., 2019; Muhammad et al., 2024). These alterations can either enhance or diminish the resilience of ecosystems to further disturbances. Therefore, a deeper understanding of these microbial dynamics is crucial for predicting and managing the ecological consequences of EWE.

Besides the impact of EWE on microbial ecosystems, EWE can also pose significant challenges to human health and wellbeing, particularly in vulnerable regions (Agache et al., 2025; Hartig, 2021). These events can compromise water quality and sanitation systems, leading to increased risks of waterborne disease outbreaks (Death et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2013). For instance, various studies reported that changes in temperature and precipitation patterns can affect the survival, reproduction, and distribution of waterborne pathogens, causing severe human health consequences (Dupke et al., 2023; Noyer et al., 2020). Moreover, warmer temperatures may promote the growth of harmful bacteria and algae in aquatic ecosystems, increasing the likelihood of human exposure through contaminated water sources. Similalry, altered rainfall patterns can lead to the contamination of drinking water supplies with pathogens from agricultural runoff and sewage (Meisner and de Boer, 2018; Piazzi et al., 2021; Yotsuyanagi et al., 2024). Therefore, understanding the interplay between climate change, extreme weather events, microbial responses, and associated human-health is essential for developing effective public health strategies to protect communities from waterborne diseases.

Keeping the above points in view, this review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of climate change induced extreme weather events on microbial communities and water quality, highlighting the critical gaps in current knowledge underlying the impact of EWE on microbial ecosystems and human health, and identifying potential mitigation strategies. We aim to explore the mechanisms through which EWE alter microbial dynamics, the resulting impacts on ecosystem health and human wellbeing, and the role of microbial communities in enhancing ecosystem resilience. Additionally, we discuss the integration of microbial insights into broader ecosystem management and public health strategies, emphasizing the need for adaptive and resilient approaches to address the escalating feedback loop between climate extremes, ecological destabilization, and public health crises.

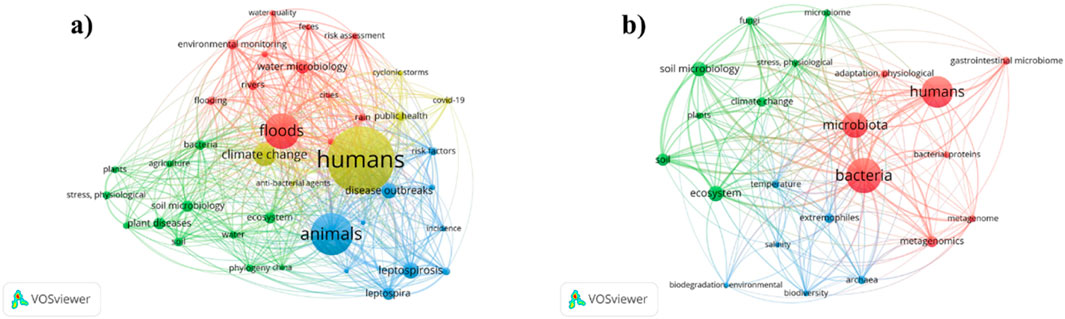

2 Detailed methodology to conduct the study

Prior to start writing regarding this study, we first conducted a detailed search on different sites, including Web of Science, google scholar, PubMed, Scopus, and ScienceDirect with the keywords extreme weather events, climate change, microbes and water quality. The detailed analysis of the searched studies has been provided in the PRISMA flowchart (Supplementary Figure S1). All the articles were downloaded and the review articles were deleted from them in an RIF file. On overall Around 141 keywords were extracted from about 1,976 major key words used in the study, and an VOSviewer figure was drawn as shown in Figure 1a. Following the search, each research article was read carefully and a summary was made based on the outcomes of each article. After that, another RIF file was drawn and a new keyword list was extracted through VOSviewer as shown in Figure 1b. During the first search, around 4 different clusters were prepared, including floods, water microbiology, environmental monitoring, feces, and risk assessment were kept in the first cluster, followed by soil microbiomes, plants, diseases, agriculture, and ecosystem in the second cluster. Similarly, cluster three was comprised disease outbreaks, animals, Leptospira, and incidence, and cluster four was consisted of humans, climate change, public health, storms, and COVID-19. Similarly, after refining the keywords to around 25 keywords, three distinct and clear clusters were prepared in Figure 1b. Here, 1st cluster was comprised of bacteria, microbiota, humans, adaptation, metagenomics, and the second cluster were comprised of climate change, soil microbial communities, fungi, plants, and ecosystems, and the 3rd cluster was consisted of biodegradation, temperature, archaea, biodiversity, and extremophiles. Through this detailed methodological co-occurrence and PRISMA (inclusion and exclusion), this detailed review was drawn.

Figure 1. Bibliographic study for the detailed search to conduct this study using various site. (a) Represents the keywords, climate change, human, flooding, animals, environmental monitoring, microbiome, and (b) represent microbes, bacteria, pathogens, ecological functions.

3 Impact of climate-change on extreme weather events

Climate change significantly exacerbates the frequency, intensity, and duration of extreme weather events, posing substantial challenges to ecosystems, infrastructure, and public health. Rising global temperatures, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels, have led to increased greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. This warming affects the water cycle, shifts weather patterns, and melts land ice, all of which can intensify extreme weather events (Cologna et al., 2025). For instance, record-breaking heatwaves, severe floods, prolonged droughts, and extreme wildfires are becoming more frequent and more intense. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), human-induced climate change has increased the frequency and intensity of these events (Cianconi et al., 2020). NASA’s satellite missions also provide vital data for monitoring and responding to these extreme weather events.

Moreover, climate change impacts on extreme weather events are not limited to direct physical effects; they also have cascading ecological consequences. For example, extreme heatwaves and droughts can lead to significant losses in biodiversity, as many species struggle to adapt to rapidly changing environmental conditions (Cianconi et al., 2020; Cologna et al., 2025). In aquatic ecosystems, these events can cause oxygen depletion, leading to mass fish kills and the proliferation of harmful algal blooms, which further degrade water quality and threaten aquatic life (Cianconi et al., 2020). Similarly, in terrestrial ecosystems, extreme weather events can lead to soil erosion, nutrient depletion, and the disruption of microbial communities that are crucial for maintaining soil health and fertility. These ecological disruptions can have long-term impacts on ecosystem services, including water purification, carbon sequestration, and the provision of food and other resources, thereby highlighting the urgent need for adaptive and resilient strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change on both natural and human systems.

4 Extreme weather events and microbial contamination

Microbial contamination is exacerbated by extreme weather events, posing significant risks to public health. These events, which are increasing in frequency and intensity due to climate change, disrupt environmental conditions and infrastructure, leading to the spread of pathogens and the emergence of infectious diseases.

4.1 Floods and storms and their association with pathogens spread and nutrients loading

Floods and storms in a growing climate change scenarios significantly impact pathogen spread, causing spikes in microbial groundwater contamination and increased fecal coliform levels in coastal waters (Marinova-Petkova et al., 2019; Noyer et al., 2020; Ruszkiewicz et al., 2019). These extreme weather events can overwhelm septic systems, leading to overflows that contaminate groundwater sources (McMichael, 2015; Meisner and de Boer, 2018). Positive storm surges can cause flooding and stagnant water, facilitating vertical and lateral contaminant transport in coastal aquifer systems (Bailey and Secor, 2016; Paerl et al., 2014). Surface contaminants and groundwater pumping can exacerbate these issues, potentially leading to health risks. Coastal groundwater vulnerability is influenced by factors such as cyclone speed, storm surge type and height, and rainfall during cyclones (Cardoso et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2020). Secondary factors, including cyclone frequency, sea-level rise, the condition of septic systems, and pre-existing contaminants, also play a role.

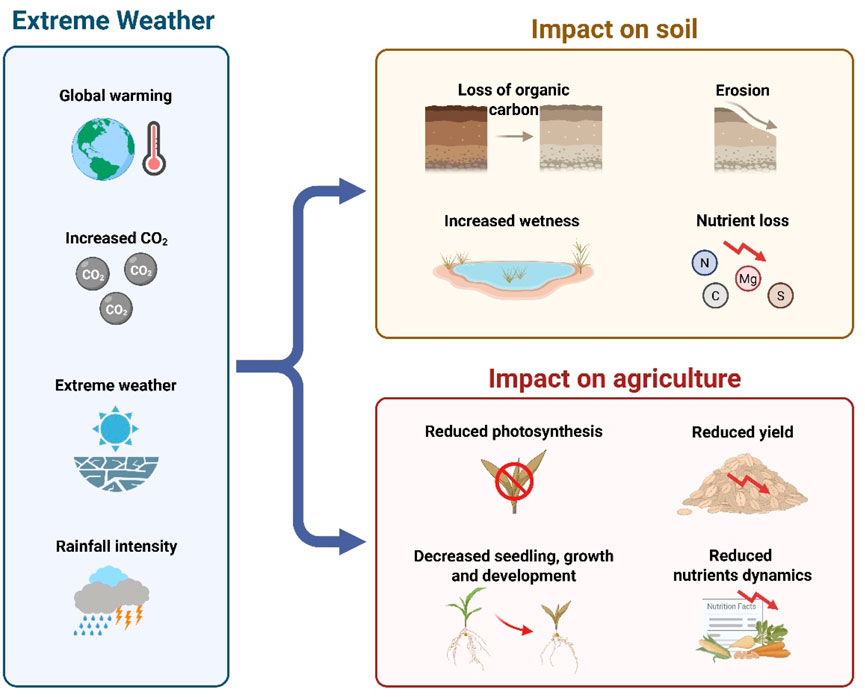

Extreme precipitation events can lead to compound flooding, where rainfall combines with storm surges to create severe flooding (Cruz-Martínez et al., 2009; Fang et al., 2023). Urbanization and anthropogenic emissions can exacerbate these events, while large-scale circulation patterns and land-atmosphere feedback contribute to internal variability in the climate system (Biswas and Karmegam, 2023; Cruz-Martínez et al., 2009). Climate change-induced extreme weather patterns, including increased frequency and intensity of tropical storms, can lead to storm surges and coastal flooding, increasing human mortality. Floods and storms can also alter microbial communities, destroy ecosystems, and cause landslides and soil erosion (Figure 2) (Brauko et al., 2020). To mitigate these risks, it is important to implement strategies to enhance resilience to extreme weather events, focusing on vulnerable populations and equitable planning. This includes managing soil health, livestock, crop farming, and fisheries. Additionally, efforts to reduce and prevent climate change are essential in breaking the cycle of climate-related weather events and disease transmission.

Figure 2. Impact of extreme weather events on environmental ecosystems, including soil and agriculture leading to reduce economic sustainability. Conceptual diagram illustrating the physical and biological pathways through which floods, droughts, and storms disrupt soil health and agricultural productivity. Key processes include: (1) soil erosion and loss of topsoil due to heavy rainfall; (2) waterlogging and anoxia in root zones from flooding, inhibiting plant growth (3) nutrient leaching (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus); from saturated soils; (4) salinization of soils in coastal areas from storm surges; and (5) altered microbial community structure and function, impacting decomposition and nutrient cycling. These disruptions collectively lead to reduced crop yields, economic losses, and long-term land degradation, threatening food security. Figure based on synthesis from Brauko et al. (2020) and Yuan et al. (2024).

Flooding events can lead to the contamination of agricultural soils with fecal wastes from municipal wastewater and livestock operations, increasing the risk of human exposure to pathogenic microorganisms through consumption of contaminated crops and water (Ahmad et al., 2022; Hallsworth, 2022; Yuan et al., 2024). Stormwater runoff in urban areas also carries microbial contaminants that can negatively impact public health.

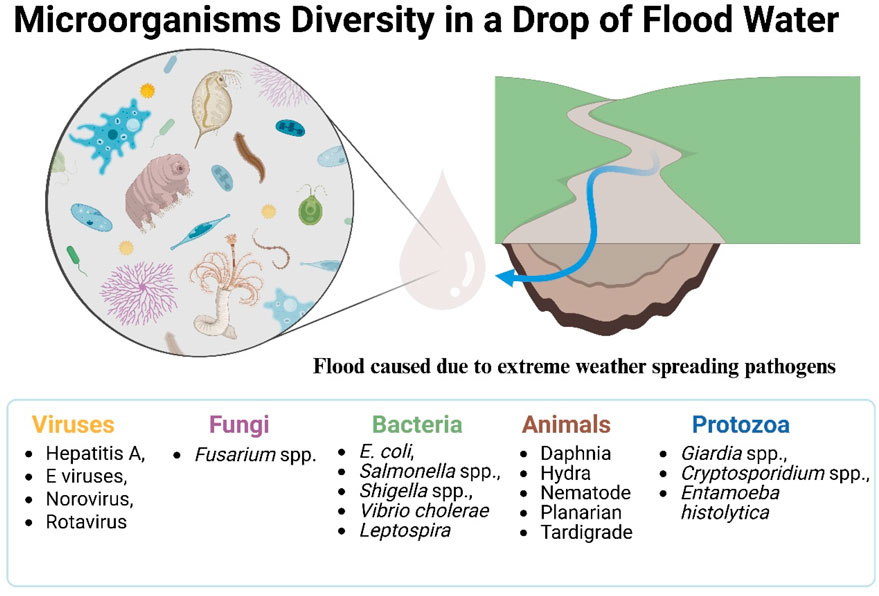

Several types of pathogens are commonly spread through floods and storms (Figure 3):

• Bacteria: Floods and storms facilitate the spread of various bacterial pathogens, including Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Vibrio cholerae, and Leptospira species. Fecal contamination of water sources is a primary concern, as it can lead to outbreaks of gastrointestinal illnesses.

• Viruses: Viral pathogens such as Hepatitis A and E viruses, Norovirus, and Rotavirus can be transmitted through contaminated water following floods and storms. These viruses often cause waterborne illnesses with symptoms ranging from mild gastroenteritis to severe liver damage.

• Protozoa: Protozoan pathogens like Giardia spp., Cryptosporidium spp., and Entamoeba histolytica can contaminate water supplies during flooding events. These parasites can cause diarrheal diseases and other gastrointestinal problems, especially in areas with inadequate water treatment facilities.

• Fungi: Flooding can lead to the growth and spread of fungi, including Fusarium spp. and other opportunistic fungal pathogens. Exposure to these fungi can result in various infections, particularly in individuals with compromised immune systems.

• Parasitic Worms: In flood-prone regions, parasitic worms such as Schistosoma species and other helminths can pose a significant health risk. Flooding can contaminate water sources with worm eggs and larvae, leading to infections upon contact or ingestion.

Figure 3. Pathogenic microorganisms present in a single drop of floodwater, highlighting the potential health risks associated with extreme weather-induced flooding. Conceptual illustration depicting the major classes of pathogenic microorganisms commonly found and concentrated in floodwaters, representing a significant public health hazard. Key groups include: Bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, Leptospira spp.); Viruses (e.g., Norovirus, Hepatitis A and E viruses, Rotavirus); Protozoa (e.g., Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia spp.); Fungi (e.g., Fusarium spp.); and Parasitic Helminths (e.g., Schistosoma spp.). These pathogens originate from overwhelmed sewage systems, agricultural runoff, and compromised sanitation infrastructure, and their transmission is facilitated by the widespread distribution of floodwater. Figure created based on mechanisms described by Thomas et al. (2006) and Fumian et al. (2023).

The risk of infectious diseases after weather or flood-related natural disasters depends on factors such as the endemicity of specific pathogens in the affected region, the extent of infrastructure damage, and population density. Climate change, with its associated increase in extreme precipitation events, is expected to further exacerbate the problem of waterborne pathogen transmission (Noyer et al., 2020). Extreme rainfall events can significantly alter estuarine carbon dynamics through multiple interconnected mechanisms. As demonstrated by (Hounshell et al., 2019) reported that in the Neuse River Estuary, intense precipitation events trigger a cascade of processes beginning with the rapid mobilization of terrestrial organic matter. When heavy rains saturate soils, they flush out dissolved organic carbon (DOC) from multiple sources including upland soils, decaying vegetation, and agricultural/urban runoff (Yotsuyanagi et al., 2024). This pulse of organic carbon enters the estuary through surface runoff and river discharge, often increasing DOC concentrations by 50% or more within hours to days after the storm. The sudden influx of DOC dramatically reshapes microbial community metabolism and function (Li et al., 2024; Yan et al., 2020). Initially, fast-growing heterotrophic bacteria like Pseudomonas and Bacteroidetes respond rapidly to the newly available labile carbon compounds such as simple sugars and amino acids (Hounshell et al., 2019). This microbial feeding frenzy leads to a spike in respiration rates, which can increase by 70% or more. However, this burst of aerobic decomposition comes at a cost, the accelerated oxygen consumption frequently depletes dissolved oxygen to hypoxic levels (<2 mg/L). As oxygen levels drop, the microbial community undergoes a fundamental shift, with fermentative bacteria and methanogens becoming dominant in the now-low-oxygen environment.

These microbial metabolic shifts have cascading effects throughout the estuary ecosystem. The development of hypoxic conditions can stress or kill oxygen-sensitive organisms like fish and shellfish, while simultaneously favoring anaerobic microbial processes such as denitrification and methanogenesis (Hounshell et al., 2019; Noyer et al., 2020). The carbon itself follows multiple fates, while some is respired as CO2, other portions may be buried in sediments or transported further downstream. Critically, these events are not isolated occurrences; as climate change increases the frequency of extreme rainfall, estuaries may face repeated DOC pulses that could fundamentally alter their carbon cycling capacity and ecological health over time. These search highlights how these weather-driven perturbations can overwhelm an estuary’s natural buffering capacity, with implications for water quality management and ecosystem resilience in a changing climate.

4.2 Droughts and heatwaves causing water scarcity and pathogen concentration and cyanobacterial blooms

Drought conditions and extreme heat significantly influence pathogen dynamics in aquatic systems, often exacerbating health risks through distinct but interconnected mechanisms (Ferreira et al., 2022; Paerl et al., 2020). During droughts, reduced water availability leads to groundwater drawdown, concentrating microbial contaminants in shrinking water supplies (Parvin et al., 2022). demonstrated this in Bangladesh, where declining water tables during dry seasons increased fecal contamination in tubewells. As groundwater levels drop, two key processes occur: (1) subsurface fecal pathogens from latrines, septic systems, or animal waste become concentrated in the reduced water volume, and (2) hydrostatic pressure changes can draw contaminated surface water or shallow groundwater into deeper aquifers through cracks or poorly sealed wells (Parvin et al., 2022). Parvin et al. (2022) found that drought-affected tubewells had 3–5 times higher concentrations of E. coli compared to wet seasons, directly linking water scarcity to elevated diarrheal disease risks in communities reliant on groundwater. Heatwaves, on the other hand, create favorable conditions for thermophilic pathogens like Vibrio spp., which thrive in warm, brackish waters (Blagrave et al., 2022; Polazzo et al., 2022; Brauko et al., 2020; Jeppesen et al., 2021) showed that prolonged heatwaves in estuaries increased Vibrio abundance by 2–3 orders of magnitude through multiple pathways: (1) accelerated growth rates at elevated temperatures (optimal growth: 25 °C–35 °C), (2) enhanced survival due to reduced host immunity in heat-stressed shellfish, and (3) stratification-driven hypoxia, which suppresses competing microbes while favoring Vibrio’s metabolic flexibility. These changes raised seafood safety concerns, as filter-feeding oysters and clams bioaccumulated pathogenic strains (V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus), increasing risks of gastroenteritis or wound infections for consumers.

Chen et al. (2020) and Liu et al. (2023) provides a critical examination of how extreme weather events can undermine nutrient reduction efforts in freshwater ecosystems, using China’s Lake Taihu as a case study (Chen et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2023). This large, shallow lake has experienced severe cyanobacterial blooms for decades, prompting significant nutrient control measures. However, the research revealed a troubling paradox: while phosphorus and nitrogen inputs were successfully reduced, heatwaves counteracted these improvements by creating ideal conditions for cyanobacteria dominance. The mechanisms behind this phenomenon involve several interconnected factors. First, cyanobacteria such as Microcystis possess distinct physiological advantages in warm water, including higher growth rates at elevated temperatures (25 °C–30 °C) compared to other phytoplankton. During heatwaves, the lake’s shallow depth facilitated rapid warming of the entire water column, eliminating thermal stratification that might otherwise limit cyanobacterial distribution. Additionally, warmer temperatures enhanced the buoyancy regulation of Microcystis colonies, allowing them to outcompete other algae by maintaining optimal positioning in the water column for both light harvesting and nutrient uptake.

Nutrient dynamics during heatwaves further exacerbated the problem (Iskin et al., 2020; Jeppesen et al., 2021). While total nutrient loads decreased due to management efforts, the higher water temperatures increased the release of legacy phosphorus from sediments through enhanced microbial mineralization (Yuan et al., 2024). This internal loading created temporary nutrient pulses that cyanobacteria were uniquely equipped to exploit. The researchers also noted that heatwaves altered the nitrogen cycle, favoring species like Microcystis that can fix atmospheric nitrogen when dissolved inorganic nitrogen becomes limited. The ecological consequences were severe. Despite reduced external nutrient loading, the lake experienced blooms of similar or greater magnitude during hot years, with Microcystis accounting for over 80% of phytoplankton biomass. These blooms led to hypoxic conditions, fish kills, and the release of hepatotoxins that threatened drinking water supplies (Yuan et al., 2024). These studies reveled that climate variables can override the benefits of nutrient management, has profound implications for water quality policies worldwide, suggesting that bloom mitigation strategies must now account for both nutrient inputs and climate-driven thermal changes in aquatic systems.

4.3 Compound events

Krueger et al. (2021) provides critical insights into how abrupt transitions from drought to flood conditions can trigger catastrophic ecological shifts in shallow lake systems (Krueger et al., 2021). Their research demonstrates that these compound climatic events create a perfect storm of conditions that rapidly degrade water quality and aquatic habitats through interconnected physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms. During prolonged drought periods, the gradual drying of shallow lakes sets the stage for subsequent ecosystem disruption (Bartolai et al., 2015; Stockwell et al., 2020). As water levels recede, large areas of sediment become exposed to atmospheric oxygen, accelerating the breakdown of accumulated organic matter. This oxidative process mineralizes nutrients and converts previously stable carbon stores into more labile forms (Canisares et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024). Simultaneously, terrestrial vegetation colonizes the exposed lakebed, creating new biomass that will later become fuel for microbial respiration. The drought phase essentially “charges” the system with reactive compounds that remain dormant until water returns. The ecological consequences become dramatically apparent when heavy rains finally break the drought (Golcher, 2020). The sudden influx of water creates a violent flushing effect, mobilizing and transporting the drought-processed organic matter and nutrients into the water column. This creates an intense pulse of dissolved organic carbon that acts like an algal bloom in reverse, instead of photosynthesis producing oxygen, microbial decomposition consumes it (Ferreira et al., 2022; Paerl et al., 2020). The system rapidly becomes oxygen-depleted as heterotrophic bacteria metabolize the carbon influx, often leading to complete anoxia within 24–48 h. These conditions trigger a cascade of secondary effects that fundamentally alter ecosystem function. The anoxic water column favors anaerobic microbial processes, including sulfate reduction that produces toxic hydrogen sulfide. Redox-sensitive metals like iron and manganese dissolve from sediments, potentially reaching concentrations harmful to aquatic life. The combination of oxygen deprivation, toxic compounds, and pH shifts creates lethal conditions for fish and other aerobic organisms, often resulting in mass mortality events.

Perhaps most significantly, some studies found that these drought-flood transitions can cause long-term ecological regime shifts. The sudden nutrient release and elimination of grazing fish populations often leads to dominance by toxin-producing cyanobacteria, establishing a new, less desirable stable state (Bailey and Secor, 2016; Rolls et al., 2017). Their calculations showed that a single such event could mineralize carbon equivalent to 15 years of normal accumulation, demonstrating how climate extremes can compress decades of ecological change into just days or weeks. These findings have profound implications for water resource management in a changing climate. Traditional approaches focused on gradual changes may be inadequate to address the nonlinear, threshold responses observed during compound events (Rolls et al., 2017). Rolls et al. (2017) highlights the need for adaptive management strategies that account for both extreme droughts and the subsequent flood risks, including maintaining minimum water levels during dry periods to prevent sediment oxidation and developing rapid response protocols for oxygen depletion events. As climate change increases the frequency and intensity of both droughts and extreme rainfall events, understanding these compound impacts becomes increasingly critical for protecting vulnerable aquatic ecosystems.

5 Ecological and health impacts

5.1 Soil microbiome shifts

Extreme weather events, particularly flooding and drought-rewetting cycles, are dramatically reshaping soil microbial communities and their critical ecosystem functions, with significant consequences for agriculture and climate regulation (Adekanmbi et al., 2025; dos Santos Custódio, 2023; Rafael Sanchez-Rodriguez et al., 2019; Bastida et al., 2021; Louca et al., 2018).

5.1.1 Microbiome shift during flooding

When soils become waterlogged due to prolonged flooding, the rapid depletion of oxygen forces a fundamental restructuring of microbial populations. Aerobic nitrifying bacteria like Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira, which normally convert ammonium to nitrate in well-oxygenated soils, are particularly vulnerable to these anoxic conditions. As a result, nitrification rates can be reduced by up to 40% within just 2 weeks, creating a nitrogen crisis for crops dependent on nitrate uptake (Rafael Sanchez-Rodriguez et al., 2019). This shift towards anaerobic conditions leads to the dominance of facultative anaerobes and obligate anaerobes like Clostridium and Geobacter, which drive the system towards fermentation and methanogenesis. Chemical transformations, such as the reduction of iron and manganese compounds, release ions that are toxic to many nitrifying bacteria, creating a negative feedback loop that prolongs the impacts even after floodwaters recede.

The agricultural consequences of these microbial disruptions are severe and multifaceted. The loss of nitrification capacity creates an immediate nitrogen deficiency for crops, particularly affecting high-demand plants like wheat and maize during critical growth stages. Farmers may respond by increasing fertilizer applications, but in waterlogged soils, this can lead to increased ammonia volatilization or denitrification losses, further reducing nitrogen use efficiency. The shift towards anaerobic microbial communities also alters soil structure, reducing water infiltration capacity and increasing erosion risk when floods recur (Furtak and Wolińska, 2023; Harvey et al., 2019). Repeated flooding events may lead to long-term changes in soil microbial ecology, potentially creating soils that are less resilient to future climate extremes (Chen and Zhang, 2015; Fuhrer, 2006).

5.1.2 Microbiome shift during drought-rewetting cycles

Conversely, drought-rewetting cycles also cause significant microbial disruptions. When severely dried soils are suddenly rehydrated, the rapid reactivation of microbial metabolism creates a pulse of denitrification activity that disproportionately increases nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than CO2 (Bastida et al., 2021; Louca et al., 2018). This occurs because drought stress kills many soil microbes, leaving behind large pools of labile organic compounds from lysed cells (Adekanmbi et al., 2025; Li et al., 2023). When water returns, surviving denitrifiers like Pseudomonas and Paracoccus exploit these nutrients in oxygen-depleted microsites, rapidly converting nitrate to N2O before complete aerobic conditions can be restored. The first rewetting event after drought can release up to 70% of the total seasonal N2O flux in just 24–48 h (Hammerl et al., 2019). These microbial responses create troubling feedback loops in the climate system, potentially amplifying agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and necessitating increased fertilizer use, which can lead to water quality issues through nitrate leaching.

Collectively, these studies highlight the critical role of soil microbiomes in mediating the impacts of climate extremes on agricultural productivity and greenhouse gas emissions. Developing management strategies that protect or restore beneficial microbial communities may be essential for building resilient agroecosystems in a changing climate.

5.1.3 Microbial ecological mechanisms underlying shifts in microbial communities during extreme events

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is a critical mechanism through which microbes adapt to changing environmental conditions. During extreme weather events, HGT can facilitate the spread of genes encoding for traits such as antibiotic resistance and the ability to degrade pollutants. For example, genes encoding nitrogenase enzymes can be transferred among bacteria, enhancing their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, as shown by Yu (2025). This process is particularly important in environments where nutrient availability is altered by EWEs. HGT can also spread antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) among microbial communities, contributing to the persistence and spread of antibiotic-resistant pathogens in contaminated environments (Bashawri et al., 2020; LaMontagne et al., 2022). Microbial communities often undergo succession following extreme weather events, with different species dominating at different stages of recovery. For example, after a drought, the sudden influx of water can mobilize organic matter and nutrients, leading to a pulse of microbial activity. This initial burst of activity is often dominated by fast-growing heterotrophic bacteria like Pseudomonas and Bacteroidetes, which rapidly consume labile carbon compounds (Hounshell et al., 2019). As oxygen levels drop due to increased respiration, the community shifts towards anaerobic processes, with fermentative bacteria and methanogens becoming dominant. This succession can lead to long-term changes in microbial community structure, affecting ecosystem resilience and recovery. Studies have shown that repeated disturbances, such as frequent drought-flood cycles, can lead to permanent shifts in microbiome function, such as nitrogen cycling (Krueger et al., 2021).

Biofilm formation is another key mechanism through which microbes adapt to extreme weather events. Biofilms provide a protective matrix that can shield microbes from environmental stressors and enhance nutrient uptake. In aquatic environments, biofilms can stabilize sediments and reduce erosion, while in soils, they can improve soil structure and water infiltration capacity. For example, Pseudomonas species are known to form biofilms that can immobilize nutrients and pollutants, reducing their movement through the soil profile (Fang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2024). Biofilms can also facilitate microbial interactions, such as syntrophy, where different species cooperate to degrade complex organic matter. This can enhance the overall efficiency of nutrient cycling and pollutant degradation in disturbed environments. Extreme weather events often lead to significant changes in temperature and pH, which can alter microbial community dynamics. For instance, heatwaves can increase water temperatures, favor thermophilic microorganisms and potentially lead to harmful algal blooms dominated by cyanobacteria like Microcystis (Paerl et al., 2020). These blooms can produce toxins that threaten water quality and public health. Additionally, changes in pH due to acid rain or the release of acidic compounds from soils can select for acid-tolerant microbial species, further altering community composition. For example, acidification can lead to the dominance of acidophilic bacteria, which can outcompete other species and affect nutrient cycling processes (Yotsuyanagi et al., 2024).

5.2 Human health risks

5.2.1 Waterborne diseases

Extreme weather events are increasingly recognized as major drivers of waterborne disease outbreaks, with heavy rainfall and flooding posing particularly severe risks to public health. Thomas et al. (2006) revealed a striking pattern in Canada, where 70% of waterborne disease outbreaks were preceded by heavy precipitation events (Thomas et al., 2006). This connection stems from multiple pathways of pathogen transmission that intensify during wet weather. Overwhelmed sewer systems release untreated wastewater into surface waters, while storm runoff carries pathogens from agricultural fields, urban areas, and compromised septic systems into drinking water sources. The research found that smaller, rural water systems were especially vulnerable to these contamination events, as they often lack the advanced treatment technologies needed to handle sudden influxes of microbial pollutants. These findings highlight how climate-driven increases in extreme precipitation may escalate waterborne disease risks, particularly in communities with aging or inadequate water infrastructure.

The complex interplay between extreme weather and disease transmission was further illustrated by Fumian et al. (2023) investigation of a norovirus outbreak in Brazil following torrential rains. This study documented how floodwaters mixed with raw sewage to create a perfect storm of viral contamination, affecting multiple exposure routes simultaneously. Recreational waters, drinking water supplies, and shellfish harvesting areas all became vehicles for norovirus transmission, with genetic analysis revealing an unusual diversity of viral strains in circulation. The outbreak’s temporal dynamics were particularly noteworthy, while the triggering rainfall event was obvious, the resulting illness surge only became apparent after a 2–3-week delay, corresponding to the pathogen’s incubation period and the time required for secondary transmission to amplify the initial environmental exposure. This lag effect can obscure the connection between extreme weather and disease outbreaks, potentially delaying public health responses.

These studies collectively demonstrate that waterborne pathogens exploit multiple vulnerabilities exposed by extreme weather events. Physical infrastructure failures allow direct contamination of water supplies, while the hydrological effects of heavy rainfall facilitate widespread pathogen dispersal through surface and groundwater systems (Dupke et al., 2023; Thomas et al., 2006). The public health consequences are magnified in communities lacking resilient water systems, where compromised sanitation infrastructure and limited healthcare access create conditions for rapid disease spread. As climate change increases the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events globally, these findings underscore the urgent need for climate-adaptive water management strategies. Investments in upgraded treatment systems, real-time water quality monitoring, and early warning systems could help mitigate the growing threat of weather-driven waterborne disease outbreaks, particularly in vulnerable communities where the health impacts are most severe.

5.2.2 Respiratory and immune effects

Faurie et al. (2022) and Li et al. (2025) revealed a concerning link between heatwaves and increased respiratory health risks through multiple interconnected mechanisms (Faurie et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025). As urban areas experience more frequent and intense heatwaves, the combination of elevated temperatures and air pollution creates ideal conditions for the persistence and transmission of respiratory pathogens (Li et al., 2025). Li et al. (2025) found that heatwaves alter urban aerosol composition in three significant ways: First, higher temperatures increase the volatility of organic compounds in airborne particles, changing their physical properties in ways that may enhance pathogen survival. Many respiratory viruses, including influenza and rhinoviruses, demonstrate greater stability in warm, dry conditions typical of heatwaves. Second, heat-stressed urban populations tend to increase their use of air conditioning, leading to more indoor crowding where airborne transmission is facilitated. Third, they identified that particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations often spike during heatwaves due to increased energy demand and thermal inversion events, providing additional surfaces for pathogens to adhere to and potentially extending their atmospheric residence time (Faurie et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025). The immunological impacts compound these exposure risks. Heat stress has been shown to suppress normal immune function in several ways: by reducing mucociliary clearance in the respiratory tract, decreasing neutrophil activity, and altering cytokine production patterns (Cantet et al., 2021; Koch et al., 2019). This creates a double burden, not only are people exposed to higher concentrations of respiratory pathogens during heatwaves, but their bodies are less equipped to fight these infections (Li et al., 2025). Li et al. (2025) particularly highlighted risks for outdoor workers, elderly populations, and those with pre-existing respiratory conditions, who showed increased hospitalization rates for respiratory infections following heatwave events. These findings have important implications for public health planning in a warming climate and suggested that heatwave preparedness plans should incorporate respiratory infection surveillance and that urban air quality management needs to consider both traditional pollutants and biological aerosols. These studies underscore the need for integrated early warning systems that combine heat alerts with air quality and respiratory disease monitoring, particularly in urban areas where the heat island effect magnifies these risks.

6 Extreme weather events and their impact on environmental contamination

6.1 Extreme weather events impact on microplastics and nanoplastics

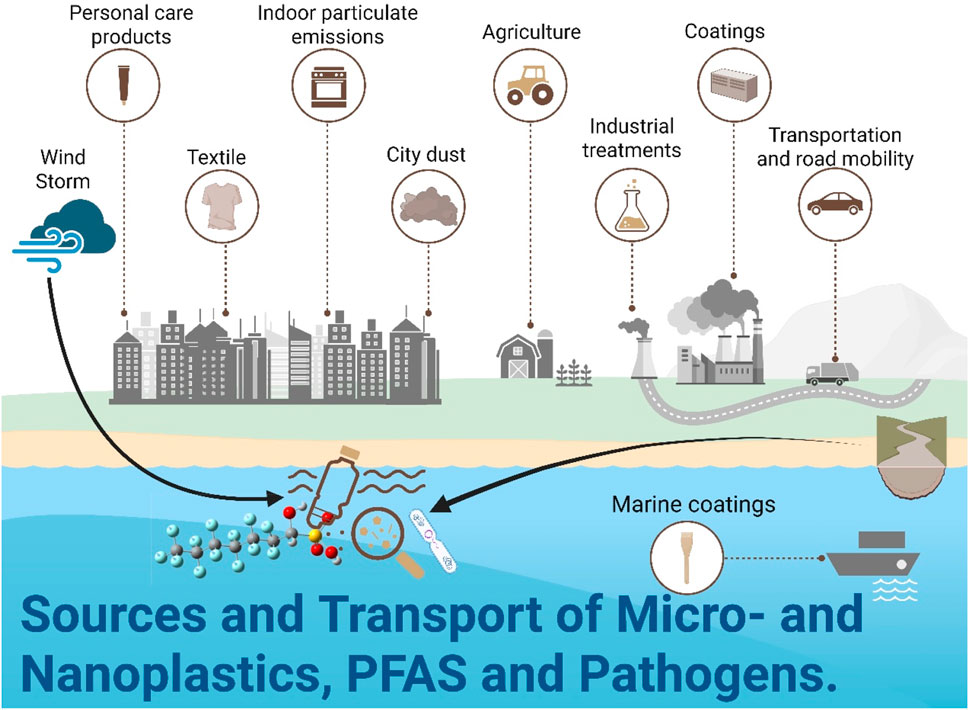

Extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfall, floods, and storms, significantly influence the fate of microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment (Table 2) (Quadroni et al., 2024; Ridall and Ingels, 2022). These events can mobilize microplastics from various sources, including urban areas, industrial sites, and landfills (Figure 4). Heavy rainfall and flooding can wash these particles into water bodies, where they are transported by currents and can be deposited in different ecosystems. The increased water flow during floods can carry microplastics over long distances, spreading them across larger areas. Additionally, high winds associated with storms can lift microplastics into the atmosphere, leading to their deposition in remote areas (Parvin et al., 2022). This widespread distribution can lead to increased bioaccumulation in aquatic organisms, posing significant risks to both wildlife and human health through the food chain. The mechanisms through which extreme weather events impact microplastics include mobilization, transport, and deposition. Mobilization occurs when heavy rainfall and flooding dislodge microplastics from soil and urban surfaces, carrying them into water bodies (Quadroni et al., 2024). Transport is facilitated by storm surges and strong currents, which can carry these particles over long distances. Deposition can occur in various environments, including rivers, lakes, and oceans, where microplastics can accumulate and be ingested by aquatic organisms. This bioaccumulation can lead to physical damage to tissues, disrupt normal physiological functions, and cause chronic health issues in affected organisms (Ridall and Ingels, 2022). The widespread presence of microplastics in the environment and their ability to bioaccumulate in the food chain highlight the urgent need for regulatory measures and public awareness campaigns to mitigate their impacts.

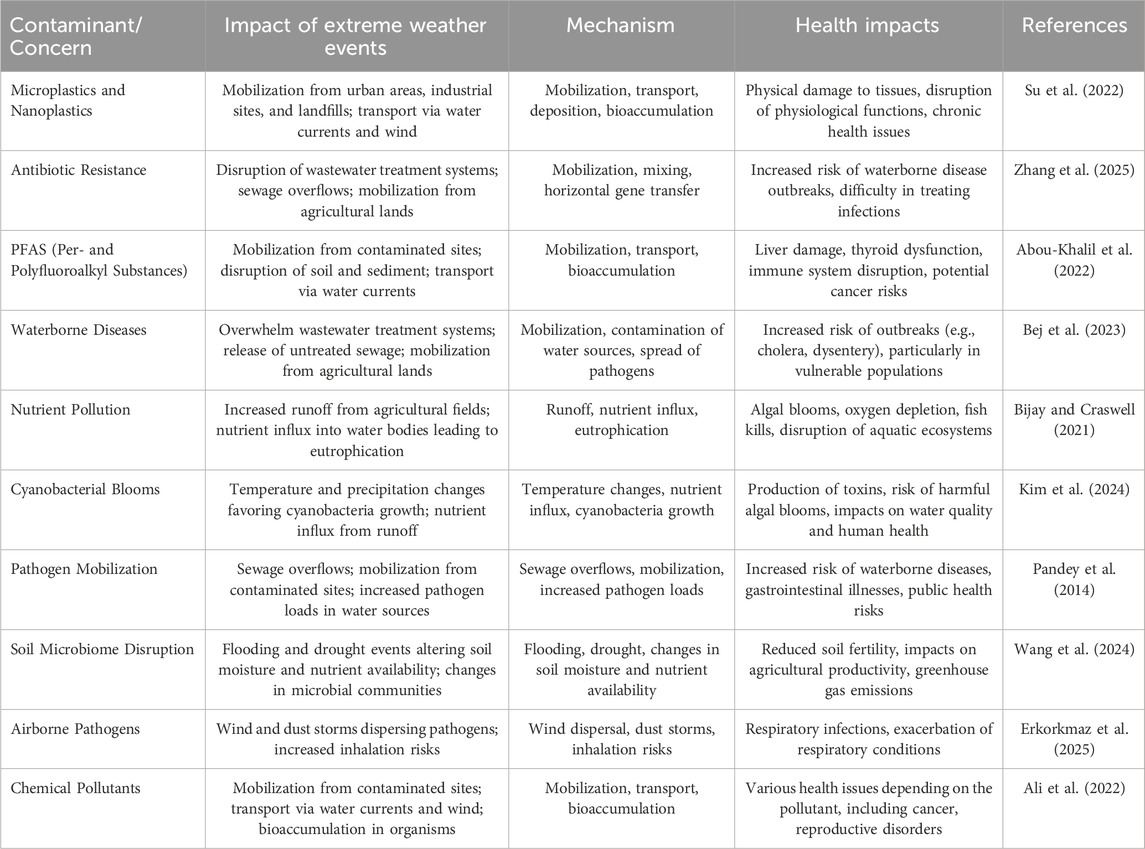

Table 2. Summarizing the impact of extreme weather events on the fate of various contaminants and emerging concerns, along with their mechanisms and potential health impacts.

Figure 4. Sources and transport of microplastics, nanoplastics, PFAS, and pathogens due to extreme weather events. Conceptual model showing how floods and storms act as distribution vectors for modern pollutants. Processes include: (1) Mobilization: Heavy rainfall dislodges microplastics from urban debris and landfills, flushes antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARBs) and genes (ARGs) from agricultural soils amended with manure, and remobilizes per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from contaminated industrial sites and sediments. (2) Transport: Stormwater runoff and river discharge carry contaminants into aquatic ecosystems. (3) Deposition and Bioaccumulation: Contaminants settle in sediments or are ingested by aquatic organisms, entering the food web. This widespread distribution exacerbates ecological and human health risks. Figure synthesized from Quadroni et al. (2024), Bashawri et al. (2020), and Abou-Khalil et al. (2022).

6.2 Extreme weather events impact on antibiotic resistant bacteria

Extreme weather events can exacerbate the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria by disrupting wastewater treatment systems and causing sewage overflows (Parvin et al., 2022). Heavy rainfall and flooding can overwhelm these systems, leading to the release of untreated wastewater into water bodies. This contamination can introduce antibiotic-resistant bacteria into drinking water sources and recreational waters, increasing the risk of waterborne disease outbreaks (Kumar et al., 2016). Additionally, heavy rainfall can mobilize antibiotic-resistant bacteria from agricultural lands, where they may have been introduced through the use of manure as fertilizer (Gray, 2021; Mirani, 2022). The mixing of contaminated water with clean water sources can facilitate the spread of these bacteria, leading to increased pathogen loads in the environment (Bashawri et al., 2020). The mechanisms through which extreme weather events impact antibiotic resistance include mobilization, mixing, and horizontal gene transfer. Mobilization occurs when heavy rainfall and flooding wash antibiotic-resistant bacteria from agricultural fields and urban areas into water bodies (Bashawri et al., 2020; LaMontagne et al., 2022). Mixing of contaminated water with clean water sources can facilitate the spread of these bacteria. Horizontal gene transfer allows antibiotic-resistant bacteria to exchange resistance genes with other bacteria in the environment, further spreading resistance. This can lead to outbreaks of waterborne diseases that are difficult to treat with conventional antibiotics, posing significant health risks to vulnerable populations. Addressing this issue requires enhanced surveillance, improved wastewater treatment, and public health measures to prevent and mitigate outbreaks of waterborne diseases.

6.3 Extreme weather events impact on PFAS

Extreme weather events can lead to the mobilization and spread of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from contaminated sites (Lan et al., 2025). PFAS are highly persistent and mobile contaminants that pose significant challenges for remediation due to their strong carbon-fluorine bonds and resistance to degradation. The transport and partitioning of PFAS in the environment are influenced by their chemical structure, particularly the length and configuration of the perfluoroalkyl chain (Ding et al., 2024; Tang et al., 2022). PFAS compounds with longer chains tend to sorb more strongly to soil and sediment, while shorter-chain PFAS are more mobile in groundwater and surface water. This partitioning behavior affects the effectiveness of remediation strategies, with longer-chain PFAS being more challenging to remove through conventional methods. PFAS partitioning involves hydrophobic and lipophobic effects, electrostatic interactions, and interfacial behaviors. The hydrophobic tail of PFAS molecules drives their association with organic carbon in soils, while the polar head groups interact with water and other media. Sorption and retardation generally increase with the length of the perfluoroalkyl tail, meaning that short-chain PFAS are more mobile and less likely to be retained in soil or sediment. This mobility makes short-chain PFAS more challenging to capture and treat, as they can travel significant distances in water systems. Bioremediation of PFAS is a promising but challenging area of research. While PFAS are highly resistant to biodegradation, some studies have shown potential for microbial degradation under specific conditions (Tang et al., 2024). For example, a recent study explored the use of a biomimetic nano-framework derived from plants, known as RAPIMER, which combines efficient adsorption with fungal biotransformation to degrade PFAS (Li et al., 2022). This approach demonstrated high adsorption rates and effective in-situ biodegradation using the fungus Irpex lacteus. However, such methods are still in the experimental phase and require further research to optimize their effectiveness and scalability. Despite these advancements, the bioremediation of PFAS remains limited compared to other contaminants. The strong carbon-fluorine bonds in PFAS make them highly resistant to microbial degradation, and effective bioremediation strategies are still under development. Future research should focus on identifying and optimizing microbial strains and conditions that can effectively degrade PFAS, as well as exploring advanced technologies such as bio-electrochemical systems and photocatalytic degradation.

Heavy rainfall and flooding can wash PFAS from industrial sites, landfills, and other sources into water bodies, contaminating drinking water sources and ecosystems. Additionally, these events can disrupt soil and sediment, releasing PFAS that were previously bound to particles. Once in water bodies, PFAS can be transported by currents and can bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms, leading to potential health risks for both wildlife and humans through the food chain (Chou et al., 2025). The mechanisms through which extreme weather events impact PFAS include mobilization, transport, and bioaccumulation. Mobilization occurs when heavy rainfall and flooding dislodge PFAS from soil and sediment, carrying them into water bodies. Transport is facilitated by storm surges and strong currents, which can carry these chemicals over long distances (Lan et al., 2025; Liao et al., 2025). Bioaccumulation can occur when PFAS are ingested by aquatic organisms, leading to increased concentrations in their tissues. This bioaccumulation can cause various health issues, including liver damage, thyroid dysfunction, and immune system disruption. The widespread presence of PFAS in the environment and their persistence highlight the need for regulatory measures to limit their use and release, as well as the development of effective remediation technologies to address existing contamination.

7 Microbial role in mitigating the impact of EWEs

7.1 Role of adapted microbes post-EWEs

Extreme weather events (EWEs) such as floods, droughts, and heatwaves significantly disrupt ecosystems, leading to changes in nutrient cycles, soil health, and water quality. Microbial communities, which play a crucial role in maintaining ecosystem functions, are particularly affected by these events (LaMontagne et al., 2022; Viergutz et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2023). However, recent studies have shown that microbial communities can adapt to repeated EWEs, potentially enhancing ecosystem resilience. This section examines how adapted microbial communities contribute to stabilizing nutrient cycles, enhancing soil health, and improving water quality following EWEs (Agache et al., 2025; Chou et al., 2025; Koren and Butler, 2004). Microbial communities are central to nutrient cycling processes such as nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification. EWEs can disrupt these processes, leading to nutrient imbalances and reduced ecosystem productivity. For instance, flooding can create anoxic conditions that inhibit nitrifying bacteria, while droughts can reduce microbial activity and nutrient availability. Rafael Sanchez-Rodriguez et al. (2019) demonstrated that prolonged flooding reduced nitrification rates by 40% within 2 weeks, leading to nitrogen deficiency in crops (Rafael Sanchez-Rodriguez et al., 2019). However, they also highlighted that certain microbial communities adapted to these conditions by shifting towards anaerobic processes like denitrification. Similarly, Fuchslueger et al. (2019), Lee, (2015) and Qu et al. (2023) showed that drought-rewetting cycles led to spikes in nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, a potent greenhouse gas, due to increased denitrification activity (Fuchslueger et al., 2019; Lee, 2015; Qu et al., 2023). This suggests that microbial adaptation to EWEs can have both positive and negative environmental impacts.

There are two main mechanisms through which microbes can help in mitigating EWEs, including Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) and community shifts (Braun et al., 2018). Microbes can acquire new genetic material through HGT, allowing them to adapt to changing environmental conditions. For example, genes encoding for nitrogenase enzymes can be transferred among bacteria, enhancing their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen (Yu, 2025). Microbial communities can shift towards species that are more tolerant of EWEs. For instance, facultative anaerobes like Geobacter can thrive in anoxic conditions, maintaining nutrient cycling functions. Kragh et al. (2020) found that drought-flood transitions in shallow lakes led to significant changes in sediment microbial communities. The sudden influx of water after a drought mobilized organic matter and nutrients, leading to anoxic conditions and mass fish kills. However, certain microbial communities adapted to these conditions, potentially stabilizing nutrient cycling and reducing long-term impacts. Hounshell et al. (2019) demonstrated that heavy rainfall events in the Neuse River Estuary led to increased dissolved organic carbon (DOC) levels, which in turn altered microbial community structure and function. Adapted microbial communities could help mitigate the negative impacts of such events by stabilizing carbon cycling. Microbes can form biofilms that protect them from environmental stressors and enhance nutrient uptake. Biofilms can also stabilize soil particles, reducing erosion (Fang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2024). Adapted microbial communities can break down complex organic matter more efficiently, releasing nutrients and improving soil fertility. Yang C. et al. (2016) showed that heatwaves in Lake Taihu counteracted nutrient reduction efforts by creating ideal conditions for cyanobacterial blooms (Yang C. et al., 2016). However, the study also highlighted the importance of dual nutrient (N + P) reduction strategies to mitigate these impacts. Deiner et al. (2017) and Pont et al. (2018) demonstrated the effectiveness of environmental DNA (eDNA) profiling in tracing fecal pollution sources after extreme rainfall (Deiner, Kristy et al., 2017; Pont et al., 2018). Real-time monitoring and targeted interventions can help reduce pathogen loads and improve water quality. Microbes can degrade pollutants and remove excess nutrients, improving water quality. For example, certain bacteria can break down hydrocarbons and heavy metals (Ali et al., 2022). Adapted microbial communities can outcompete or inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria, reducing the risk of waterborne diseases.

7.2 Bioremediation and nutrient sequestration to mitigate EWEs

Bioremediation is a process that leverages the metabolic capabilities of microorganisms to degrade environmental pollutants into less harmful substances (Chen et al., 2025; Dong, 2007). This process is particularly effective in mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events (EWEs), which often lead to the mobilization and spread of pollutants. The primary mechanisms of bioremediation include bioaugmentation, biostimulation, and biosorption (Table 3). Bioaugmentation involves the introduction of specific pollutant-degrading microorganisms to contaminated sites to enhance degradation processes (AlKaabi et al., 2020; Vallalar et al., 2019). For example, AlKaabi et al. (2020) reported that Bacillus sonorensis was successfully used to degrade weathered oil hydrocarbons in soil, achieving significant removal efficiencies. Biostimulation, on the other hand, involves the addition of nutrients or electron donors/acceptors to stimulate the metabolic activity of indigenous microorganisms, thereby enhancing their ability to degrade pollutants (Ali et al., 2023a). Biosorption and bioaccumulation involve the adsorption and accumulation of heavy metals and other pollutants by microorganisms, which can be particularly useful in remediating contaminated water sources (AlKaabi et al., 2020; Lenart et al., 2024; Toubali et al., 2022). Nutrient sequestration refers to the process by which microorganisms capture and store nutrients, preventing their loss through leaching or runoff (Ali et al., 2023b; Ali et al., 2024a). This is crucial for maintaining soil fertility and ecosystem health, especially after EWEs. Microbial decomposition of organic matter releases nutrients into the soil, enhancing fertility and sequestering carbon. Additionally, biofilm formation by microorganisms can immobilize nutrients and pollutants, preventing their movement through the soil profile and reducing the risk of nutrient loss.

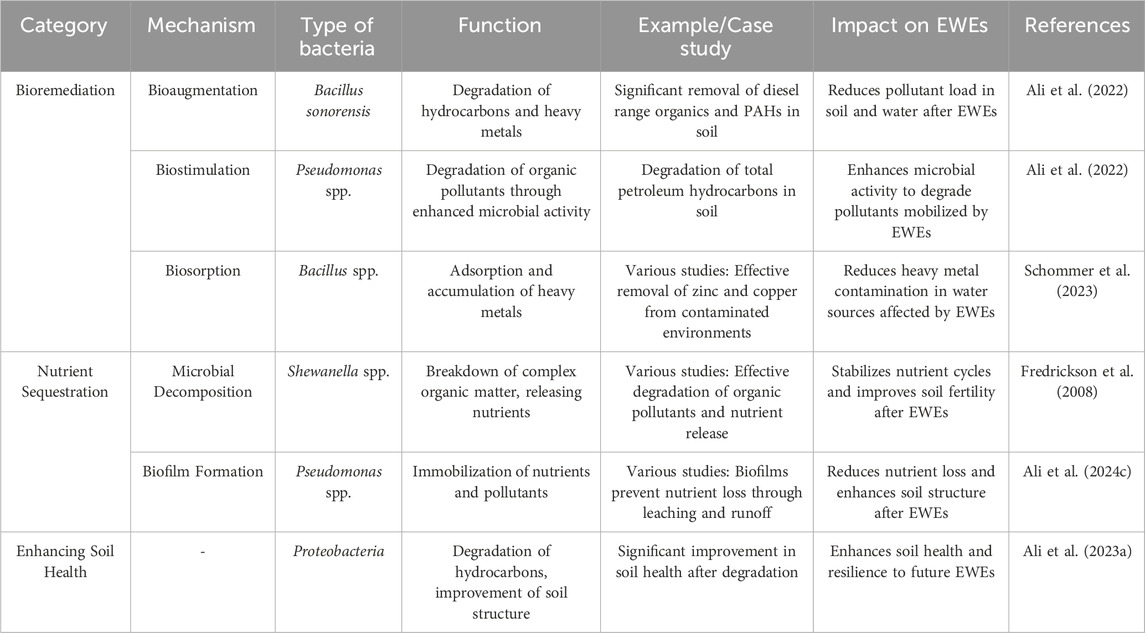

Table 3. Summarizing the key aspects of bioremediation and nutrient sequestration for mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events (EWEs).

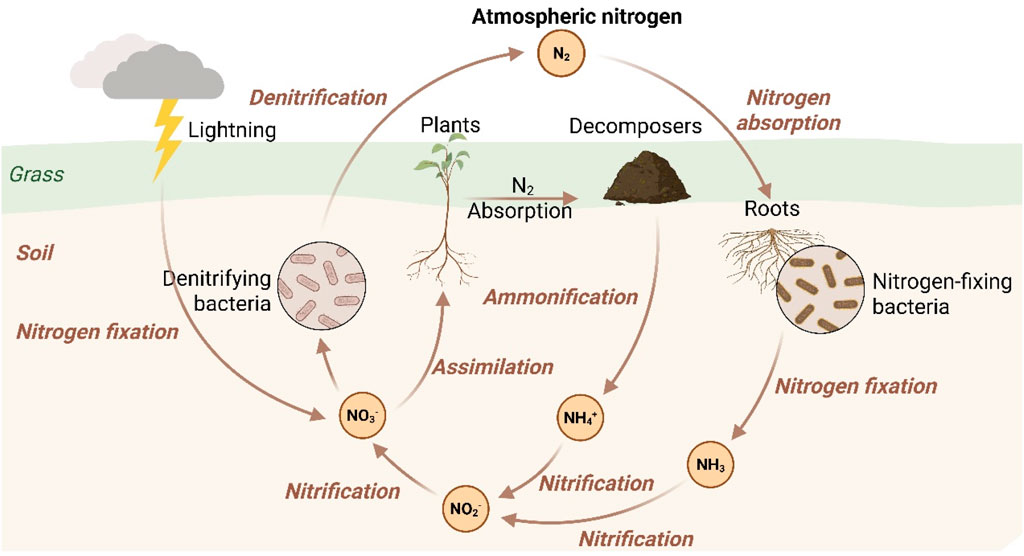

Microorganisms, particularly bacteria, play a pivotal role in bioremediation and nutrient sequestration. Pseudomonas species are known for their ability to degrade a wide range of organic pollutants, including hydrocarbons and heavy metals. These bacteria produce enzymes like laccases and peroxidases that break down complex compounds (Ali et al., 2023a; Ali et al., 2024b). Bacillus species are also versatile and can degrade hydrocarbons and heavy metals (Hosseini et al., 2025). They are known for their ability to produce biofilms that immobilize pollutants, enhancing soil health and reducing erosion. Shewanella species are capable of reducing metals and degrading organic pollutants, participating in the anaerobic degradation of hydrocarbons. These bacteria can help mitigate the impacts of EWEs by stabilizing nutrient cycles, nitrogen cycling (Figure 5), and reducing the availability of pollutants in the environment.

Figure 5. Nitrogen cycle owing to the stabilized microbes carrying the potential under extreme weather events. Conceptual diagram illustrating how key nitrogen transformation processes are disrupted or enhanced by EWEs. Flooding (left) creates anoxic conditions, suppressing nitrification (NH4+ to NO3−) by bacteria like Nitrosomonas and promoting denitrification (NO3− to N2O/N2) by bacteria like Pseudomonas, leading to nitrogen loss and greenhouse gas emissions. Drought-Rewetting (right) causes microbial cell lysis, releasing organic nitrogen (Org-N), and upon rewetting, triggers a pulse of denitrification and N2O emission. Adapted microbial communities can stabilize the cycle by maintaining ammonia oxidation and completing denitrification to N2. Figure based on experimental results from Rafael Sanchez-Rodriguez et al. (2019) and Palmer et al. (2016).

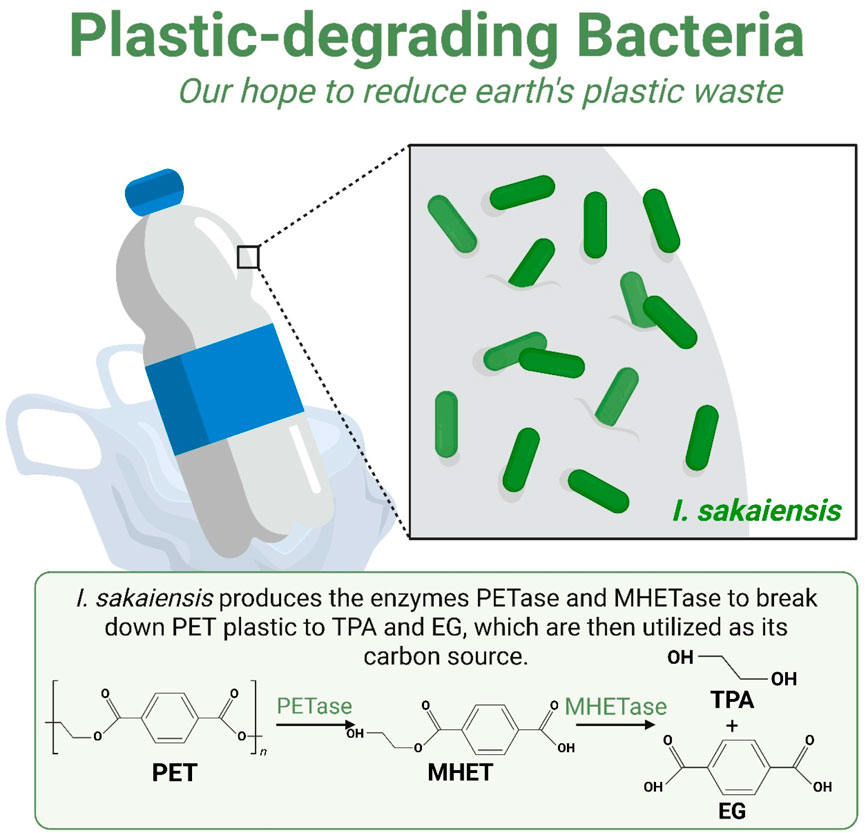

Bioremediation techniques such as bioaugmentation and biostimulation can be effectively used to degrade pollutants mobilized during EWEs. For instance, introducing pollutant-degrading bacteria like Pseudomonas and Bacillus can accelerate the breakdown of hydrocarbons and heavy metals. A study by Oualha et al. (2019) demonstrated that bioaugmentation with Bacillus sonorensis achieved significant removal efficiencies of diesel range organics and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in weathered oil-contaminated soil. Nutrient sequestration through microbial decomposition and biofilm formation can prevent nutrient loss through leaching or runoff, which is particularly important after EWEs that can lead to nutrient depletion in soils. The use of microbial consortia, such as Flavobacterium johnsoniae and Shewanella baltica, has been shown to achieve high degradation efficiencies of PAHs in contaminated soil, thereby sequestering nutrients and improving soil health. Enhancing soil health through microbial activity is crucial for maintaining ecosystem resilience after EWEs. A study by (Chaudhary et al., 2021) demonstrated that a bacterial consortium comprising Proteobacteria could degrade total petroleum hydrocarbons in diesel-contaminated soil within 60 days, significantly improving soil health. The biodegradation of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) is a complex process primarily facilitated by specific microbes and their enzymes during the extreme weather conditions. One of the most well-known PET-degrading microbes is Ideonella sakaiensis, which secretes PETase, an enzyme that breaks down PET into smaller molecules like MHET (mono-(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate) and BHET (bis-(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate) (Palm et al., 2019) (Figure 6). Another enzyme, MHETase, further hydrolyzes MHET into terephthalic acid (TPA) and ethylene glycol (EG), which can then be metabolized by the microbe. Other microbes, such as Rhodococcus pyridinivorans P23, also play a significant role in PET degradation. This marine bacterium uses a membrane-anchored PET esterase to convert PET into MHET and BHET, which are subsequently broken down into TPA and EG (Gao et al., 2024). Additionally, Thermobifida fusca, a thermophilic bacterium, can degrade PET efficiently at higher temperatures using cutinase enzymes. These enzymes hydrolyze PET into TPA and EG, making T. fusca a valuable candidate for industrial applications due to its ability to operate at elevated temperatures (Yip et al., 2024). The discovery and study of these microbes and their enzymes have significant implications for environmental sustainability, as they offer potential biotechnological solutions for PET waste management. Future research may focus on optimizing degradation conditions, engineering microbes with enhanced capabilities, and integrating these processes into industrial waste management systems to effectively reduce plastic pollution.

Figure 6. Extreme weather conditions and the resistant microbes helping in the biodegradation of microplastics and nanoplastics. Mechanistic diagram depicting the enzymatic breakdown of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastics, a process that can be influenced by environmental stressors like heatwaves. Key steps include: (1) Attachment: Bacteria like Ideonella sakaiensis and Rhodococcus pyridinivorans P23 colonize the plastic surface (2) Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Secreted enzymes (e.g., PETase, MHETase). break down PET polymers into monomeric units like mono (2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalic acid (MHET) and terephthalic acid (TPA). (3) Assimilation: These breakdown products are transported into the cell and metabolized as carbon and energy sources. This figure highlights the potential for bioremediation of microplastic pollution, even in a changing climate. Model based on the discovery by Palm et al. (2019) and recent studies by Gao et al. (2024) and Yip et al. (2024).

Bioremediation and nutrient sequestration by adapted microbial communities offer promising strategies for mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events (EWEs). By degrading pollutants, stabilizing nutrient cycles, and enhancing soil health, these mechanisms can improve ecosystem resilience and reduce the negative effects of EWEs. Future research should focus on identifying and optimizing the most effective microbial strains and consortia for specific contaminants and environmental conditions. Integrating bioremediation with other ecosystem management practices can further enhance the resilience of ecosystems to EWEs, ensuring long-term environmental stability and sustainability.

8 Infrastructure resilience, eDNA, and sustainable policies as mitigation and adaptation strategies

Three major mitigation and adaptation strategies have been well-documented, including infrastructure resilience, environmental DNA, and sustainable policies. Extreme weather events (EWEs) significantly threaten water quality and public health by exacerbating microbial contamination, but targeted mitigation and adaptation strategies can reduce these risks. One critical approach is enhancing infrastructure resilience (Table 4). For example, Luby et al. (2018) demonstrated that upgrading sanitation systems in Bangladesh, such as sealing septic tanks and elevating latrines, reduced post-flood E. coli contamination in drinking water (Luby et al., 2018). Similar measures, including reinforcing wastewater treatment plants to handle overflow and promoting decentralized systems like constructed wetlands, can prevent pathogen spread during floods. Additionally, protecting groundwater supplies through raised well casings and managed aquifer recharge (MAR) can mitigate drought-related water scarcity and contamination.

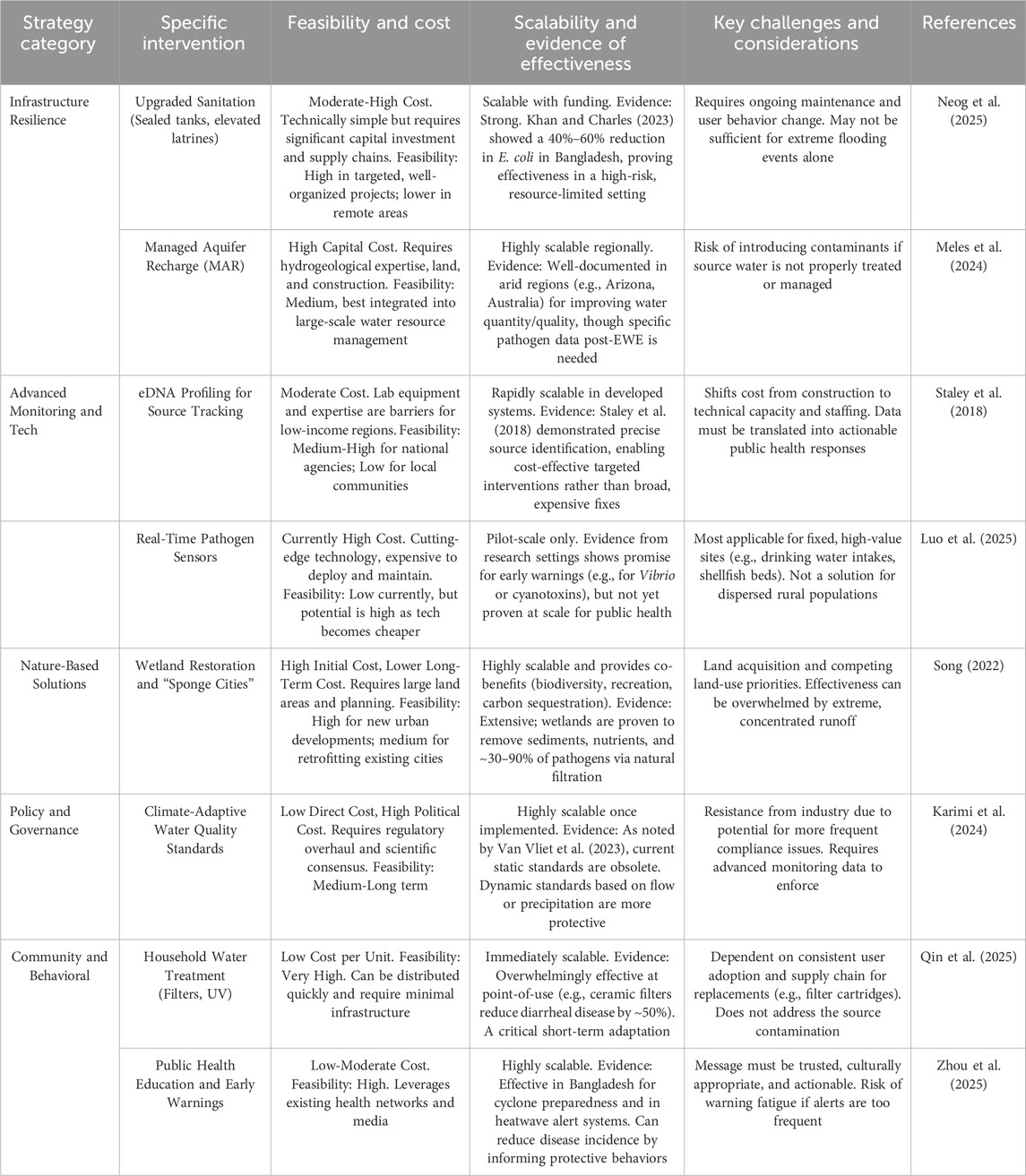

Table 4. Extreme weather events mitigation strategies and feasibility, cost, scalability, and key challenges need for consideration.

Advanced monitoring tools are equally vital for timely responses to EWEs. Deiner et al. (2017) showcased the effectiveness of environmental DNA (eDNA) profiling in tracing fecal pollution sources after extreme rainfall, enabling rapid identification of contamination hotspots (Deiner et al., 2017). Real-time sensors for pathogens like Vibrio or Cryptosporidium could further enhance early warning systems, particularly in vulnerable estuaries or urban watersheds. These technologies, combined with predictive modeling, allow communities to anticipate risks and implement preventive measures before waterborne disease outbreaks occur. Policy reforms must also address gaps in current water quality standards.

van Vliet et al. (2023) emphasized that global regulations often fail to account for climate-driven fluctuations in contamination levels (van Vliet et al., 2023). Developing adaptive thresholds for pathogens and nutrients, linked to weather forecasts and historical EWE data, could improve compliance and enforcement. Urban planning should integrate climate resilience, such as designing “sponge cities” with permeable surfaces to absorb floodwaters or restoring wetlands to filter agricultural runoff. Such nature-based solutions not only reduce microbial hazards but also enhance ecosystem stability. Community engagement is another cornerstone of effective adaptation. Educating vulnerable populations about household water treatment methods, such as using ceramic filters or UV disinfection during droughts, empowers individuals to safeguard their health. Training programs on safe water storage and hygiene practices can further minimize exposure to pathogens after floods. Local partnerships with governments and NGOs are essential to ensure equitable access to these resources, particularly in low-income regions disproportionately affected by EWEs. Ultimately, a multidisciplinary strategy, combining infrastructure upgrades, technological innovation, policy adjustments, and public education, is necessary to mitigate the microbial risks amplified by extreme weather. By prioritizing proactive measures and climate-resilient designs, societies can better protect water security and public health in an era of increasing climate variability. While technological and ecological solutions exist to mitigate the microbial risks from Extreme Weather Events (EWEs), their real-world effectiveness is heavily dependent on economic, logistical, and social factors as discussed in Table 4.

Despite its comprehensive scope, this review is subject to several important limitations that reflect broader challenges within the field. Firstly, the available literature exhibits a significant geographical bias, with a preponderance of studies from North America, Europe, and parts of Asia, thereby constraining our understanding of context-specific vulnerabilities and microbial responses in the most data-poor yet highly vulnerable regions of Africa and South America. Secondly, the temporal scale of most existing research captures only immediate or short-term microbial shifts following extreme weather events (EWEs), creating a critical knowledge gap regarding long-term microbial community recovery, adaptation, and the potential for permanent ecological regime shifts. Furthermore, a methodological constraint persists across many studies, which often document changes in microbial taxonomy or pathogen abundance without quantitatively linking these shifts to measured functional outcomes, such as alterations in nutrient cycling rates, greenhouse gas flux, or direct human health risk. Finally, as a synthesis of existing work, this review is inherently constrained by the scope and quality of the primary literature; the discussions on emerging contaminants like PFAS and microplastics are based on a rapidly evolving but still nascent field of study, and the proposed mitigation strategies, while theoretically sound, often lack extensive empirical validation regarding their cost-effectiveness, scalability, and practicality across diverse socioeconomic and infrastructural contexts. Addressing these limitations is paramount for future research to progress from documenting impacts to forecasting outcomes and implementing robust, equitable, and effective solutions.

9 Future research directions

As climate change intensifies extreme weather events (EWEs), critical knowledge gaps remain in understanding their long-term impacts on microbial ecosystems and public health. Three key research priorities emerge:

9.1 Long-term microbial adaptation to repeated EWEs

A pressing question is how recurrent floods, droughts, and heatwaves influence the evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in environmental microbes. Studies should investigate whether EWEs:

• Selection for “super-adapted” pathogens through repeated stress exposure

• Accelerate horizontal gene transfer between bacteria in flooded soils or warming waters

• Create reservoirs of ARGs in sediments or biofilms that persist between events

9.2 Ecosystem recovery and microbial succession

The timeline and trajectory of post-flood microbial communities in estuaries and other sensitive ecosystems remain poorly understood. Priority areas include:

• Quantifying how long pathogen loads remain elevated after floodwaters recede

• Identifying “indicator species” that signal ecosystem recovery or degradation

• Assessing whether repeated disturbances lead to permanent shifts in microbiome function (e.g., nitrogen cycling)

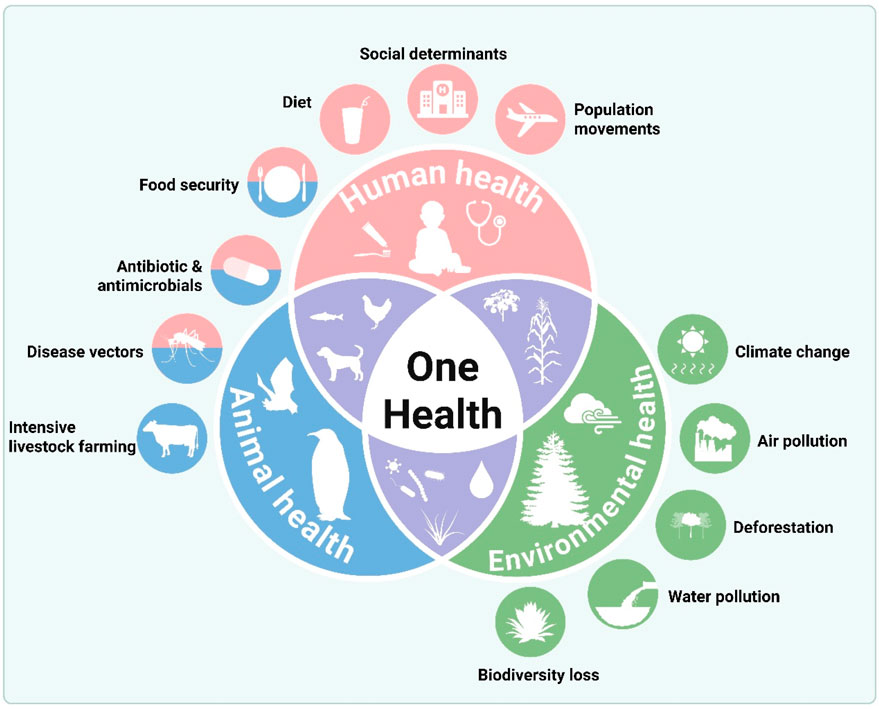

9.3 One health integration

A unified approach connecting human, animal, and environmental microbiomes could reveal (Figure 7):

• How zoonotic pathogens (e.g., Leptospira, Vibrio) exploit EWEs to cross species barriers

• Whether wildlife microbiomes serve as early warning systems for emerging diseases

• How agricultural practices during droughts/floods alter microbiome interactions across the food chain.

Figure 7. A unified one-health approach connecting human, animal, and environmental health. Conceptual model illustrating the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health in the context of climate-driven EWEs. The model shows how a stressor like a flood (center) directly impacts all three domains: contaminating human water supplies and spreading disease, altering animal habitats and promoting zoonotic pathogen transmission, and disrupting environmental balance by changing microbial ecology and mobilizing pollutants. The arrows demonstrate the continuous feedback loops between these domains, emphasizing that effective mitigation and adaptation strategies (outer ring), such as integrated surveillance, resilient infrastructure, and protected ecosystems, must be interdisciplinary to build overall system resilience.

10 Conclusion

This review has comprehensively analyzed the impacts of extreme weather events (EWEs) on microbial communities and water quality, highlighting the critical role of microbes in mediating ecosystem responses and the significant challenges posed by climate change. Our analysis underscores the need for a deeper understanding of microbial dynamics and their interactions with environmental conditions to predict and manage the ecological consequences of EWEs. Despite substantial research, significant gaps remain in our knowledge of how extreme weather events alter microbial functions and the long-term impacts on ecosystem health and human wellbeing. The review identifies several key limitations, including the complexity of microbial interactions, the scarcity of long-term studies, and the underdevelopment of integrated microbial insights into ecosystem management and public health strategies. To address these challenges, we recommend enhancing monitoring and data collection through real-time systems like environmental DNA (eDNA) profiling, developing adaptive management strategies that account for the variability of EWEs, promoting interdisciplinary research to foster collaboration between hydrologists, microbiologists, and public health experts, and strengthening policy and regulation to ensure dynamic and adaptive water quality standards. By prioritizing these recommendations, we can build more resilient and sustainable ecosystems, better equipped to withstand the escalating impacts of climate change on water quality and public health. Future research should focus on long-term microbial adaptation, ecosystem recovery, and the integration of a unified One Health approach to address the complex interplay between climate extremes, microbial dynamics, and human health.

Author contributions

SH: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Resources. FJ: Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration, Validation, Funding acquisition, Resources. QD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. KF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. SH: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Plan of China (2023YFD1900205-01), the Central Guidance for Local Science and Technology Development Plan (2024ZY0033), the Jinggang Shan Agricultural Hi-tech District Project (20222-051261), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42267055), and the scientific research team project of Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2025YL055).

Conflict of interest

Author QD was employed by State Grid Shaanxi Electric Power Co., Ltd. Authors JY, KF, ZW, SH, and YQ were employed by Beijing Jingneng International Holdings Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2025.1674490/full#supplementary-material

References

Abou-Khalil, C., Sarkar, D., Braykaa, P., and Boufadel, M. C. (2022). Mobilization of Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in soils: a review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 8 (4), 422–444. doi:10.1007/s40726-022-00241-8

Adekanmbi, A. A., Zou, Y., Shu, X., Pietramellara, G., Pathan, S. I., Todman, L., et al. (2025). Legacy of warming and cover crops on the response of soil microbial function to repeated drying and rewetting cycles. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 76 (1), e70044. doi:10.1111/ejss.70044

Agache, I., Hernandez, M. L., Radbel, J. M., Renz, H., and Akdis, C. A. (2025). An overview of climate changes and its effects on health: from mechanisms to one health. J. Allergy Clin. Immunology-in Pract. 13 (2), 253–264. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2024.12.025

Ahmad, H. A., Ahmad, S., Cui, Q., Wang, Z., Wei, H., Chen, X., et al. (2022). The environmental distribution and removal of emerging pollutants, highlighting the importance of using microbes as a potential degrader: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 809, 151926. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151926

Ali, M., Song, X., Ding, D., Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., and Tang, Z. (2022). Bioremediation of PAHs and heavy metals co-contaminated soils: challenges and enhancement strategies. Environ. Pollut. 295, 118686. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118686

Ali, M., Song, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., Che, J., Chen, X., et al. (2023a). Mechanisms of biostimulant-enhanced biodegradation of PAHs and BTEX mixed contaminants in soil by native microbial consortium. Environ. Pollut. 318, 120831. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120831

Ali, M., Song, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., Zhang, M., Chen, X., et al. (2023b). Thermally enhanced biodegradation of benzo[a]pyrene and benzene co-contaminated soil: bioavailability and generation of ROS. J. Hazard. Mater. 455, 131494. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131494

Ali, M., Song, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., Zhang, M., Ma, M., et al. (2024a). Effects of short and long-term thermal exposure on microbial compositions in soils contaminated with mixed benzene and benzo[a]pyrene: a short communication. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 168862. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168862

Ali, M., Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., Chen, X., Ma, M., Tang, Z., et al. (2024b). Mechanisms of benzene and benzo[a]pyrene biodegradation in the individually and mixed contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 347, 123710. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123710

Ali, M., Xu, D., Yang, X., and Hu, J. (2024c). Microplastics and PAHs mixed contamination: an in-depth review on the sources, co-occurrence, and fate in marine ecosystems. Water Res. 257, 121622. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2024.121622

AlKaabi, N., Al-Ghouti, M. A., Jaoua, S., and Zouari, N. (2020). Potential for native hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria to remediate highly weathered oil-polluted soils in Qatar through self-purification and bioaugmentation in biopiles. Biotechnol. Reports Amst. Neth. 28, e00543. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00543