- 1School of Economics and Management, Taiyuan University of Science and Technology, Taiyuan, China

- 2School of Economics and Management, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China

The global water crisis is intensifying, and scarce water resources have become a critical strategic factor in achieving sustainable development—an issue particularly pressing for China. Existing research on water resource policies predominantly examines the effects of common green innovation among water-intensive enterprises, whereas studies focusing specifically on sustained green innovation remain limited. However, easing water resource pressures and promoting green, high-quality development depend on enterprises’ long-term commitment to green innovation. Therefore, this study employs a Difference-in-Differences (DID) approach to empirically investigate the impact of China’s water resources tax reform on sustained green innovation among water-intensive firms listed on the A-share market from 2012 to 2022, as well as the underlying mechanisms. The empirical results reveal three key findings. First, the water resource tax significantly increases the level of sustained green innovation within these enterprises. Second, the tax promotes continuous innovation by alleviating financing constraints and attracting green investment, and managerial environmental awareness further strengthen this positive effect. Third, state-owned enterprises, large firms, enterprises located in eastern regions, and high-tech firms exhibit more pronounced improvements in sustained green innovation. By uncovering the behavioral responses of enterprises under water resources tax constraints, this study contributes new perspectives to theoretical research on water conservation, emissions reduction, and sustained green innovation. It also provides important policy implications for optimizing green tax instruments to promote sustainable green development and enhance innovation persistence.

1 Introduction

According to the World Meteorological Organization’s State of the World’s Water Resources Report (2023), global river levels have exhibited a continuous decline over the past 5 years, with 2023 recording the lowest average river flows in more than 3 decades. This severe global water situation suggests that freshwater resources are becoming increasingly scarce and critical for sustainable development. Although China ranks among the world’s leading nations in total water resources, its per capita water availability is approximately one-third of the global average, and nearly two-thirds of its cities experience varying degrees of water scarcity. Water scarcity has thus emerged as a critical bottleneck restricting China’s pursuit of high-quality development (Yao and Li, 2023). According to the World Bank, industrial water use in China constitutes approximately 17%–23% of total water consumption,1 underscoring the sector’s vital role in the national economy and its substantial water demand. The country’s water stress levels consistently exceed 40%, categorizing China as a region experiencing high water stress. The imbalance between water supply and demand is pronounced, posing significant challenges to long-term sustainability. As illustrated in Figure 1, although China’s water productivity has gradually improved, it remains relatively low overall and lags significantly behind that of developed countries. This indicates that China’s current economic growth remains heavily dependent on intensive water consumption, underscoring the urgent need to enhance the quality and technological sophistication of its development. China faces a severe challenge characterized by “high pressure and low efficiency” in water resource utilization, tightening water constraints coupled with low economic returns on water use, which poses risks to long-term sustainable development. Countries such as Germany and the Netherlands, which adopted water resource taxation earlier, have leveraged technological and managerial advancements to effectively mitigate water stress while sustaining industrial competitiveness. This demonstrates that China continues to lag behind developed economies in industrial water conservation, pollution reduction, and technological advancement, rendering water resources an increasingly strategic and scarce asset.

Figure 1. Water productivity in some countries (Sources: World Development Indicators of the World Bank).

Since the reform and opening-up, China’s traditional resource-intensive industrial development model has imposed substantial pressure on the nation’s water resources. To address the escalating challenges of water environment management, China’s 14th Five-Year Plan explicitly emphasizes the comprehensive advancement of a water-saving society. Industrial water conservation efforts must adhere to the principle of “water-based production planning” to promote water efficiency and pollution reduction within the industrial sector (Xu L. et al., 2024). Water-intensive industrial enterprises act as key drivers of rapid economic growth; however, they are also major contributors to water-related environmental problems due to their substantial consumption of industrial water resources. Resource-based theory posits that the effective utilization of scarce resources enhances corporate competitive advantage (Barney, 1991), whereas green innovation is widely recognized as a crucial strategic pathway for optimizing resource allocation and improving efficiency (Chen, 2008). At present, industrial enterprises are undergoing a pivotal transition toward high-quality development, necessitating green innovation strategies to improve water resource efficiency. However, one-time innovation investments are insufficient to establish sustainable competitive advantages. Achieving substantial environmental improvements requires continuous, long-term green innovation practices, which constitute the core driving force of a sustainable green economy (Liu L. et al., 2025). Nevertheless, sunk costs and financial constraints frequently compel enterprises to adhere to outdated technological trajectories, thereby impeding continuous innovation (Song et al., 2025). Therefore, guiding and supporting water-intensive industrial enterprises in sustained green innovation is essential for transforming water resource utilization from extensive to efficient and intensive models.

To balance water resource constraints with sustained economic growth and to promote green production and lifestyles, the Ministry of Finance, the State Taxation Administration, and the Ministry of Water Resources jointly issued the Interim Measures for the Pilot Reform of the Water Resources Tax (Cai Shui [2016] No. 55) in 2016. The pilot program was initially launched in Hebei Province in July 2016 and was subsequently extended to nine additional provinces in the following year. Existing research indicates that the water resource tax reform has become an effective policy instrument for promoting intensive and efficient water use and advancing water ecological civilization in China (Xi, 2018; Zhao et al., 2024). Corporate green and sustainable innovation represents an inevitable pathway toward achieving long-term sustainable economic development. Accordingly, several critical research questions warrant urgent investigation: Can the water resource tax reform incentivize water-intensive enterprises to engage in sustainable green innovation? Can it simultaneously promote water conservation and enterprise development? Through what mechanisms does this policy influence the green innovation behavior of water-intensive enterprises? Addressing these questions carries significant theoretical and practical implications, particularly for elucidating the policy’s impact pathways at the enterprise level.

2 Literature review

2.1 Green taxation and water

2.1.1 Water resources tax

In 1920, British economist Arthur Pigou first introduced the concept of the “Pigouvian tax” in his seminal work The Economics of Welfare. He argued that governments could internalize negative externalities by imposing taxes proportional to the degree of environmental damage (Pigou, 1920). Water resource taxation constitutes a practical application of this theory within the domains of environmental and water resource management. Existing research on water resource tax can be broadly classified into two primary directions.

The first stream comprises qualitative assessments of institutional frameworks at the theoretical level, including discussions of tax reform objectives (Jiang et al., 2021), evaluation criteria (Wang et al., 2020), institutional deficiencies (Ye and Zhang, 2021), and policy improvement recommendations (Zhang B., 2022). The second stream focuses on empirical analyses of the policy’s practical outcomes. (1) Water Conservation Effects. Numerous studies have shown that water resource taxes effectively regulate water use. For example, early empirical studies found that water resource taxes promoted residential water conservation in Sweden and industrial water conservation in the Netherlands (Clinch et al., 2006; Höglund, 1999; Kraemer, 2003), while also improving water use efficiency in developing regions such as Uganda and the Dniester River Basin (Bacal and Boboc, 2015; Kilimani et al., 2015). Recent studies have further confirmed the policy’s positive impact on regional water conservation, significantly enhancing water use efficiency and reducing water intensity in pilot regions (He and Chen, 2021; Luo et al., 2022; Ouyang et al., 2024; Tian et al., 2021; Zhang J., 2022). (2) Environmental Benefits. Water resource taxes facilitate the market exit of “high-water-consuming and high-polluting” enterprises through more efficient resource allocation, while encouraging existing firms to reduce wastewater discharge (Li et al., 2024; Li and Wang, 2023). Moreover, the policy enhances firms’ ESG-related environmental performance (Liu, 2023; Wang Q. et al., 2025; Wen et al., 2025), with its effectiveness closely associated with the applied tax rate level (Wei, 2023). (3) Dual Dividend Effect. Prior studies have confirmed that the policy yields a “dual dividend” by simultaneously improving water use efficiency and promoting technological innovation (Liu et al., 2022).

2.1.2 Other taxation

Researchers have found that other environmental policies have also played a beneficial role in improving water resource utilization efficiency and reducing industrial water pollution. Environmental fees incentivize industrial water conservation, decreasing Spain’s industrial water demand (Vallés-Giménez and Zárate-Marco, 2013). Moreover, Environmental protection taxes effectively curb industrial water pollution, as evidenced by reductions in chemical oxygen demand (COD) and ammonia nitrogen emissions (Zhang Y. et al., 2023). Sun et al. (2021) demonstrated, using input–output modeling, that carbon taxes reduce total water footprints and improve water use efficiency. Production taxes curb the expansion of water-intensive industries, while subsidies can redirect production factors toward water-efficient sectors (Wang et al., 2025b). Mulyanti et al. (2024) proposed that groundwater tax revenues should be specifically allocated to water resource conservation initiatives in Indonesia. It is evident that existing research on green taxation and water resources primarily focuses on direct improvements in water efficiency or wastewater reduction, with limited attention to water resource utilization efficiency within the context of sustained green innovation.

2.2 Corporate sustainable green innovation

Technological innovation refers to activities aimed at developing new or improved products, processes, or services, with the primary objective of enhancing economic performance. Green innovation specifically denotes technological advancements that substantially reduce environmental pollution and conserve resource consumption. The concept of sustainable innovation, introduced by scholars such as Malerba and Geroski in the 1990s, highlights the continuous nature of firms’ innovation processes, encompassing implementation, capability enhancement, and benefit realization (Clausen et al., 2012). Sustainable innovation reflects the long-term accumulation of knowledge and technological progress within enterprises, typically manifested through R&D investments, product development, and process improvement (Kamaruddeen et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2024; Xiang, 2006). Unlike conventional green innovation, sustainable green innovation is characterized by two core features: the continuity of innovation activities and the dynamic accumulation of outcomes (Pan et al., 2024). This innovation model plays a pivotal role in fostering high-quality economic development and has therefore attracted considerable scholarly attention. Existing research in this field primarily unfolds along two dimensions.

The first stream of research focuses on assessing firms’ sustainable green innovation performance. This typically entails evaluating indicators such as innovation outputs and R&D investments before and after the implementation of green initiatives (Liu L. et al., 2025; Liu M. et al., 2025; Triguero and Córcoles, 2013). The second stream examines the key drivers of sustainable green innovation, encompassing both macro-level institutional environments and micro-level organizational factors. At the macro level, the digital economy promotes green innovation primarily through two mechanisms: enhancing resource allocation efficiency and alleviating financial constraints (Zhang and Yu, 2024).

At the meso and micro levels, various factors positively influence sustainable green innovation, including CEO openness, digital transformation, supply chain digitalization (Jiang et al., 2025), ESG performance (Sun et al., 2024), and dividend distribution policies. Moreover, sustainable green innovation is positively correlated with CEO openness, primarily through the channels of digitalization and CEO equity ownership (Liu L. et al., 2025). Digital transformation further enhances firms’ innovation capabilities, with employee and executive compensation structures serving as positive moderating factors (Liu M. et al., 2025). Additionally, the influence of dividend distribution on sustainable green innovation becomes more pronounced when agency costs rise and knowledge management capabilities improve (Li and Luo, 2024). In energy-intensive industries, studies indicate that the risks associated with sustainable green innovation primarily propagate upstream along the supply chain (Zhao and Li, 2024).

2.3 Environmental policy and corporate green innovation

Existing research on the relationship between environmental policy and corporate green innovation primarily explores three key dimensions.

1. The Porter Hypothesis posits that environmental tax policies can significantly enhance firms’ green technological innovation capabilities. Goulder and Schneider (1999) employed a general equilibrium framework to illustrate how carbon taxes redirect research resources toward emission-reduction technologies. Acemoglu et al. (2012) subsequently developed a two-sector endogenous growth model integrating environmental and polluting technologies, revealing synergistic effects when environmental taxes are implemented in conjunction with R&D incentive policies. Numerous empirical studies offer robust support for this theoretical framework. For instance, Calel and Dechezleprêtre (2016) found that under the EU Emissions Trading System, firms’ low-carbon innovation rates increased by 10%. Sharif et al. (2023) confirmed a positive relationship between environmental fiscal policies and ecological technological progress in ASEAN countries. Recent studies employing dual machine learning approaches revealed that transitioning from water resource fees to taxes significantly stimulated firms’ green innovation vitality (Xu C. et al., 2024; Zhu and Zhang, 2024), manifesting in both mission-driven green technological innovation and energy-saving management practices (Kang et al., 2024). Furthermore, the degree of marketization and the evolution of financial technologies further strengthened this causal relationship (Kang et al., 2024).

In examining sustained corporate green innovation, Acemoglu et al. (2016) constructed a dual-sector model of clean and pollution-intensive technologies based on endogenous growth theory. This framework demonstrates how well-designed environmental taxes and R&D incentives can effectively steer corporate innovation toward sustainable technological pathways. Recently, Rastegar et al. (2024) revealed a marked growth trend in sustainable energy innovation within developed economies. Concurrently, Liu et al. (2024) show that combining green financial instruments with stringent environmental regulations effectively promotes firms’ sustainable green innovation. For example, policies in national big data pilot zones support continuous green innovation through financial, talent, and industrial channels.

2. The Inhibition Hypothesis posits that environmental policies impose additional cost burdens on firms, crowding out green investments and consequently suppressing green innovation. Palmer et al. (1995) challenged the Porter Hypothesis, emphasizing that regulatory compliance requirements impose substantial pressure on firms’ innovation capacity. Through a systematic literature review, Jaffe et al. (2005) revealed that market failures can cause environmental taxes to hinder rather than promote innovation. Hall and Lerner (2010) emphasized that innovation funding depends heavily on firms’ internal financial resources, implying that compliance obligations may constrain corporate innovation processes. Dechezleprêtre and Sato (2017) examined the direct economic effects of environmental policies on resource-intensive industries, while Stucki et al. (2018) confirmed, based on analyses of Chinese and European enterprises, that regulatory constraints may hinder the development of environmentally friendly products.

3. The Uncertainty Hypothesis proposes a nonlinear relationship between environmental regulation and corporate green innovation, typically manifesting as U-shaped, inverted U-shaped, or threshold effects (Wang et al., 2021).

The existing literature provides a solid foundation for examining the micro-level effects of water resource tax policies; however, several gaps remain. First, from a research perspective, limited attention has been paid to the impact of water resource tax policies on firms’ sustainable green innovation, as most studies focus on general green innovation. Second, research on the mechanisms underlying policy impacts remains insufficient. Current studies tend to emphasize internal transmission channels—particularly financial pressure, while overlooking the role of external sustainable development resources. Third, the analysis of firms’ behavioral responses to such policies remains limited. Existing studies primarily examine external moderating factors such as marketization and fintech development, but fail to capture firms’ internal behavioral responses, particularly changes in managerial environmental awareness.

Compared with prior research, this study makes three major contributions. First, by introducing a green taxation perspective, it expands the theoretical framework of sustainable green innovation and offers a novel lens for analyzing how water resource tax reforms influence the sustainable innovation behavior of water-intensive industrial enterprises. Second, it delineates the impact mechanisms of water resource taxes through two mediating pathways—alleviating external financing constraints and attracting green investors—thereby laying a theoretical foundation for evaluating policy effectiveness. Third, it emphasizes the moderating role of managerial environmental awareness in shaping the relationship between policy implementation and sustainable green innovation. By confirming its positive moderating effect, the study addresses an important gap in understanding firms’ behavioral responses to green tax policies.

3 Institutional context and theoretical analysis

3.1 Institutional context

As China’s industrialization continues to accelerate, it has become imperative to transition from a resource-intensive growth model to a new paradigm of industrial water use centered on green and sustainable development. Achieving industrial restructuring and high-quality green growth requires the widespread adoption of water-saving technologies to improve resource efficiency. Given the current state of water resource utilization in China, upgrading water-saving equipment, modernizing water treatment facilities, and transforming production processes through green technological innovation remain long-term challenges that demand sustained commitment and investment.

To strengthen water resource management, China launched a pilot water resource tax program in Hebei Province in July 2016. The following year, the policy was expanded to Beijing and nine additional provinces and autonomous regions. The water resource tax follows the core principle of “tax-fee conversion,” ensuring a smooth transition from fee-based management to a tax-based system. This reform is characterized by three key features. First, the pilot regions encompass eastern, central, and western China, ensuring balanced representation and broad applicability. Second, the reform achieves unified tax administration: previously administered by the water resources fees were managed by three departments that included the Ministry of Water Resources, the Ministry of Finance, and the Price Department; water fees are now collected uniformly by tax authorities and remitted directly to the national treasury. This mandatory collection mechanism effectively curtails interdepartmental rent-seeking behavior. Finally, the reform standardizes both collection methods and tax rates. The system has shifted from the former “pay-as-you-go” principle to a “fixed-rate levy” model. In addition, higher tax rates apply to groundwater extraction (particularly in overexploited areas), special industrial water use, and consumption exceeding established quotas. For water-intensive industries, ad valorem taxation and higher rates more accurately internalize water resource costs, thereby heightening industry sensitivity to price fluctuations. This mechanism incentivizes firms to enhance unit water efficiency and mitigate the negative externalities associated with water extraction and consumption (Pigou, 1920).

In summary, the transition from water resource fees to a tax-based system, the implementation of differentiated tax rates reflecting regional and industrial characteristics, the enhancement of water conservation and wastewater reuse capacity in water-intensive sectors, and the promotion of a shift from extensive to intensive, water-saving practices collectively contribute to the high-quality development of China’s green industry.

3.2 Theoretical analysis

Research in environmental economics indicates that, as a policy instrument, the water resource tax achieves cost internalization by incorporating external water costs into firms’ operating expenditures. This mechanism is particularly effective in water-intensive industries, where higher tax rates amplify environmental cost pressures and incentivize firms to engage in sustainable green innovation (Zhang J. et al., 2023). Furthermore, from the perspectives of legitimacy theory and institutional change, the water resource tax represents a critical component of environmental resource legislation. It reshapes corporate perceptions of environmental protection and facilitates the implementation of sustainable green innovation. In addition, firms that comply with legal and regulatory requirements gain improved access to external resources such as government subsidies and bank financing (Liu, 2023). Consequently, the legitimate implementation of this policy opens new financing channels for continuous green innovation, thereby alleviating firms’ financial constraints. Under these conditions, water-intensive firms—constrained by environmental policies and motivated to maintain corporate reputation while fulfilling social and environmental responsibilities—are compelled to proactively advance internal innovation. This process gradually promotes the adoption of green production methods and sustainable water-use practices, thereby continuously enhancing firms’ sustainability capacity through ongoing green innovation.

From the perspective of tax theory, the water resource tax system reinforces the legitimacy of environmental governance by imposing higher tax burdens on energy-intensive and highly polluting firms (Xu and Li, 2024). This compels water-intensive industrial firms to reduce compliance costs through the upgrading of water-saving equipment, the improvement of wastewater treatment systems, and investments in technological innovation. Conversely, from the perspective of tax incentives, the policy enables governments to support firms through subsidies for water-saving technologies, green investments, and technological upgrades. Such incentives not only stimulate corporate technological innovation but also discourage inefficient water-use practices, preventing the implementation of measures that do not improve water efficiency. Collectively, these measures promote “voluntary water conservation and management.” Although some firms may experience increased costs and financing constraints when pursuing continuous green innovation, government tax incentives and related measures can strengthen their green development reputation and enhance their attractiveness to social investors.

Porter and Linde (1995) argue that well-designed environmental regulations can stimulate technological innovation, thereby enhancing production efficiency and reducing compliance costs. In other words, although the short-term innovation pressures associated with water resource taxation may temporarily increase corporate costs, sustained long-term green innovation strengthens firms’ sustainable development capacity, optimizes growth quality, and enhances overall industry competitiveness.

Hypothesis 1. Water resource taxation promotes sustainable green innovation among water-intensive industrial firms.

Innovation theory posits that sustained technological advancement necessitates stable and sufficient financial support. However, because of uncertain returns and information asymmetry, firms often struggle to sustain innovation momentum, leading to high compliance costs and limited access to external financing (Liu L. et al., 2025). According to signaling theory, firms that fulfill environmental and social responsibilities not only cultivate a positive corporate reputation but also transmit favorable signals to stakeholders, capital markets, and social investors. Such signaling conveys operational stability and enhances firms’ capacity to obtain financial support and attract the fiscal and social resources required for continuous innovation, thereby strengthening their long-term sustainability capability (Wang Q. et al., 2025). Furthermore, financial institutions actively respond to government directives by collaborating with water-intensive industries engaged in continuous green innovation. Through financing mechanisms such as credit facilities and bond issuance, these institutions provide financial support that alleviates firms’ funding constraints and mitigates financial pressures.

Moreover, the participation of green investors provides strong external support for firms to undertake long-term and stable innovation activities. Green investment is widely recognized as a key driver of energy conservation and emission reduction, thereby advancing corporate green development (Tang et al., 2024). Such investments also enhance resource efficiency and improve overall environmental quality. According to stakeholder theory, under the influence of green investors, firms are more likely to raise environmental standards in their management practices, thereby promoting engagement in green innovation (Cao, 2025). The participation of green investors also signals a firm’s long-term commitment to sustainable development (Yu and Zhang, 2025). This deep engagement not only mitigates the risks associated with sustained green innovation but also enhances the likelihood of success by facilitating access to critical resources, technologies, and market opportunities (Tang et al., 2024). Driven by stakeholder environmental demands, firms actively adopt water-saving management practices, develop energy- and water-efficient products, and reduce wastewater discharge. By integrating resource optimization with dynamic R&D strategies supported by green financing, firms can overcome the limitations of traditional high-energy-consumption and high-pollution models, thereby enhancing their capacity for sustained green innovation and competitiveness in sustainable development.

Hypothesis 2. Water resource taxation promotes sustainable green innovation in water-intensive industrial firms by alleviating financing constraints and fostering green investor participation.

Drawing on upper echelons theory and cognitive management theory, the characteristics and cognitive orientations of senior managers exert a profound influence on organizational behavior (Hambrick and Mason, 1984). Senior managers interpret and respond to environmental changes according to their distinct values, attitudes, developmental experiences, and cognitive frameworks (Liu L. et al., 2025). The attention-based view posits that corporate behavior is shaped by the focal points of managerial attention. Managers with forward-looking environmental cognition tend to formulate proactive environmental visions and strategic objectives for their organizations. Firms exhibiting such foresight typically allocate budgets for green R&D, eco-friendly equipment, and employee sustainability training, perceiving these investments as essential foundations for developing future green dynamic capabilities and sustainable competitive advantages—that is, the organizational capacity to focus attention on sustainability-oriented activities.

Managers filter information according to their perceptions of the environmental context. Environmentally oriented managers guide corporate intelligence systems to monitor external environments for changes in green policies, technological opportunities, and consumer preferences, thereby informing strategic decisions related to sustained green innovation under the water resource taxation policy. Consequently, corporate environmental awareness constitutes the core component of environmental orientation and serves as a critical driver of sustainable green innovation. Executive-level environmental concern directly influences a firm’s ability to mobilize resources effectively for green development, thereby ensuring the orderly advancement of sustained green innovation initiatives.

Hypothesis 3. Water resource taxation promotes sustainable green innovation in water-intensive industrial firms, with managerial environmental awareness serving as a positive moderator of this relationship.

Figure 2 presents the core theoretical framework of this study. In this framework, OIP represents sustainable green innovation within water-intensive industrial enterprises.

4 Research design

4.1 Sample and data sources

To examine the impact of the water resource tax reform on sustainable green innovation among water-intensive industrial enterprises, this study employed A-share listed companies from 2012 to 2022 as the research sample. The sample selection process proceeded as follows: (1) firms designated as ST, ST*, or PT in any year were excluded; (2) financial institutions were removed to retain only industrial listed firms; (3) firms listed for less than 1 year or with debt ratios exceeding 100% were excluded; and (4) firms with substantial missing data were also eliminated. Firm-level financial data and green patent information were obtained from the CSMAR and the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) database, respectively. Following the 2012 revision of the Guidelines for Industry Classification of Listed Companies and prior literature, 25 high-water-consumption industries were identified based on industry codes, including B06–B09, B11, C13–C15, C17–C19, C22–C26, C28–C33, C38, and D44–D45. All continuous variables were winsorized at the 1% and 99% percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers on estimation results.

4.2 Model design

This study employs a Difference-in-Differences (DID) approach to investigate the effect of water tax policies on sustainable green innovation among enterprises. The baseline regression model is specified as follows:

In Equation 1, the subscripts t and i represent the year and the firm, respectively. OIPit denotes the firm’s level of continuous green innovation in a given year; didit is defined as the interaction between the treatment-group indicator (treati) and the post-policy dummy variable (postt), capturing the effect of the water resource tax reform. Xit represents a vector of control variables, while yeart and Indi denote the year and industry fixed effects, respectively. The key coefficient β1 captures the policy’s effect on firms’ sustainable green innovation, whereas εit represents the random error term.

4.3 Variable measurement

1. Explanatory Variable (OIP). Enterprises promote technological progress through consistent and stable R&D investment, which not only enhances green innovation capacity but also fosters economic growth. Due to data limitations in accessing comprehensive R&D expenditure information for listed firms, this study adopts the number of green patent applications as a proxy for green innovation performance. The number of patent applications is widely regarded as a timely and reliable indicator of corporate innovation output. Following prior research (Liu L. et al., 2025; Liu M. et al., 2025), this study examines trends in green patent applications before and after the policy intervention to capture the persistence of green innovation. To avoid zero values in the calculations, 1 is added to each observation before taking the natural logarithm.

In this Equation 2, OIPit represents the enterprise’s annual level of sustainable green innovation, while OINt, OINt−1, and OINt−2 denote green patent applications for the current, previous, and two preceding years, respectively.

2. Core explanatory variable (did). The core explanatory variable, did, is a dummy indicator representing the implementation of the water resource tax policy. Specifically, treati equals 1 if a firm is located in a pilot region implementing the policy, and 0 otherwise. Similarly, postt is a time dummy variable that equals 1 for 2017 and subsequent years—when the respective province implemented the policy—and 0 otherwise.

3. Mechanism Variables: ① Financing Constraints (WW). This study employs the WW index, constructed from five financial indicators—operating cash flow, cash dividends, long-term debt, total assets, and revenue growth rate—to measure firms’ financing constraints. Higher WW index values correspond to greater financing constraints. ② Green Investor Participation (Green). If a company’s investment portfolio includes green investment funds, it is classified as having green investors. The variable Green is defined as a dummy variable: if a company has one or more green investors in a given year, the value of Green is set to 1; otherwise, it is set to 0.

4. Moderating Variables: Management Environmental Awareness (MEA). MEA reflects a firm’s commitment to environmental responsibility and is evaluated based on multiple criteria. Specifically, these criteria include disclosure of the firm’s environmental philosophy, establishment of environmental targets, implementation of environmental management systems, and organization of environmental education and training programs. Furthermore, MEA covers the adoption of special environmental measures, establishment of emergency response mechanisms for environmental incidents, receipt of environmental honors and awards, and compliance with the “three-simultaneities” system. Each element is assigned a value of one point, yielding a maximum total score of eight points.

5. Control Variables. Drawing on prior research, this study includes a set of control variables that may affect organizational innovation performance (OIP) in water-intensive industrial enterprises. The control variables comprise Asset, representing asset growth, calculated as the annual growth rate of total assets; Age, measured as the natural logarithm of the number of years since the firm’s establishment; Top1, representing ownership concentration, measured as the shareholding proportion of the largest shareholder; Board, indicating board size, measured as the natural logarithm of the total number of board members; Dlcr, the long-term capital debt ratio, calculated as the ratio of non-current liabilities to total capital (including shareholders’ equity); Dual, a binary variable equal to 1 if the roles of board chairperson and general manager are concurrently held by the same individual, and 0 otherwise; Indep, denoting board independence, measured by the proportion of independent directors on the board; Growth, defined as the annual percentage change in revenue relative to the preceding year; HHI(Industry Competition Intensity), measured by the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, calculated as the sum of the squares of each firm’s proportion of main business revenue relative to the industry’s total; Rd (R&D Intensity), measured as the ratio of corporate R&D expenditures to operating revenue. Furthermore, time and industry fixed effects are incorporated to control for unobserved heterogeneity.

5 Empirical analysis

5.1 Descriptive statistics

As shown in Table 1, the mean value of sustainable green innovation among enterprises is 0.705, with a standard deviation of 1.213. The minimum and maximum values are 0 and 4.812, respectively. These statistics suggest that the overall level of sustainable green innovation among water-intensive industrial enterprises is relatively low, with considerable variation across firms. Notably, all correlation coefficients are below 0.8. Specifically, the correlation coefficient between the water resource tax policy and sustainable green innovation is 0.080 and statistically significant at the 1% level, providing preliminary evidence of a positive association between the two. Furthermore, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all variables range from 1.030 to 1.480, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a major concern. Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for the key variables.

5.2 Benchmark regression analysis

Table 2 presents the results of three regression models. Column (1) reports the OLS estimates, whereas Columns (2) and (3) present the results from fixed-effects estimations. Column (2) includes time fixed effects, while Column (3) incorporates both industry and time fixed effects. At the 1% significance level, the regression coefficients in Columns (1) and (3) are statistically significant at 0.229 and 0.219, respectively. At the 5% significance level, the interaction term in Column (2) also shows a significantly positive relationship. These findings indicate that the water resource tax effectively encourages firms to engage in green innovation, thereby providing empirical support for Hypothesis 1. As a regulatory instrument, the water resource tax compels firms to internalize external environmental costs. Moreover, higher tax rates raise water-related expenditures for water-intensive firms. To reduce compliance costs, firms tend to adjust their green innovation strategies, which may lead to long-term cost savings and operational efficiencies. Consequently, water-intensive industrial firms derive greater benefits from green innovation, which in turn drives them toward higher levels of sustainable green innovation.

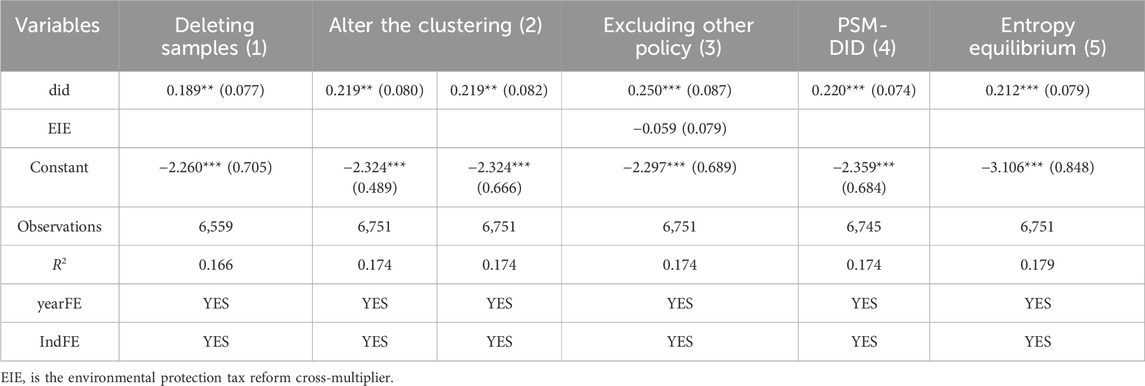

5.3 Robustness tests

5.3.1 Parallel trends test

The validity of the DID approach depends on the parallel trends assumption, which requires that, before policy implementation, the trends in sustainable green innovation between water-intensive enterprises in pilot and non-pilot regions follow similar trajectories. Figure 3 illustrates the results of the parallel trends test. This study adopts an event study approach to track the dynamic evolution of sustainable green innovation between the treatment and control groups by introducing dummy variables for the 5 years preceding and following policy implementation, as well as for the year of implementation itself (Beck et al., 2010). As shown in Figure 3, all coefficients are statistically insignificant before policy implementation, indicating that there were no significant differences in sustainable green innovation between the treatment and control groups before the policy was enacted. This finding confirms that the parallel trends assumption holds. Furthermore, a joint significance test of the pre-policy coefficients yields an insignificant result (p = 0.5191), further supporting the validity of this assumption.

5.3.2 Other robustness tests

5.3.2.1 Placebo test

To eliminate random noise and enhance the credibility of causal inference, this study conducts a placebo test using randomly generated treatment groups. Pseudo-treatment groups are constructed by randomly selecting enterprises from the full sample to match the actual pilot group in size, while maintaining consistent policy implementation periods. This random assignment and estimation process is repeated 500 times (Xu and Li, 2024), and in each iteration, the interaction term regression is estimated for the variable “postt.” As shown in Figure 4, the distribution of regression coefficients estimated from the random samples is symmetric around zero and closely follows a normal distribution, in stark contrast to the distribution of the actual observed coefficients. Additional significance tests indicate that most p-values exceed 0.1, suggesting that these regression coefficients are statistically insignificant at the 10% level. This result confirms that the study’s main findings are not driven by random chance.

5.3.2.2 Deleting samples

Hebei Province first implemented the water resource tax pilot program in 2016, and the policy was subsequently expanded to nine additional provinces, one autonomous region, and several municipalities directly under the central government in 2017. To mitigate potential sample selection bias and enhance the robustness of the empirical results, this study re-estimates the model after excluding the Hebei sample (Wang Q. et al., 2025). The regression results are reported in Table 3. After incorporating time and industry fixed effects (Column 1), the interaction term remains significantly positive at the 5% level. These findings suggest that the water resource tax continues to significantly promote firms’ sustainable development through green innovation. The results are consistent with the benchmark regression estimates, further validating the study’s conclusions.

5.3.2.3 Changing the clustering approach

This study relaxes the regression assumptions by clustering standard errors at higher hierarchical levels. Given that local governments in China exert considerable influence over regional policies and economic environments, the error terms may exhibit serial correlation at both the region–firm and industry–firm levels. Following the two-way clustering approach proposed by Cameron et al. (2011), this study further adjusts the clustering hierarchy by conducting robustness tests on cluster-robust standard errors at the industry and regional levels. As shown in Table 3, the benchmark results remain robust after calculating cluster-robust standard errors at different hierarchical levels.

5.3.2.4 Excluding other policy

Although the environmental protection tax has effectively stimulated technological innovation among enterprises, its impact on sustained green innovation remains uncertain. As the environmental protection tax and the water resource tax were implemented during roughly the same period and both fall under the broader environmental policy framework, it is reasonable to suspect that the former may confound the policy effects of the latter. To control for potential confounding effects arising from environmental tax reform, we constructed Equations 3, 4 as follows:

In the policy treatment dummy variable Treati, regions with increased pollutant tax rates are assigned a value of 1, while others are assigned 0. The time dummy variable Tt equals 1 for 2018 and subsequent years, and 0 otherwise. The regression results are reported in Table 3. As shown in Column (4), the coefficients of the primary policy dummy variables are all significantly positive. However, the interaction term associated with environmental tax reform is statistically insignificant. This suggests that the observed positive effect on sustained green innovation among water-intensive industrial enterprises is not driven by the environmental protection tax.

5.3.2.5 PSM-DID

Because the selection of water resource tax pilot regions was non-random, selection bias may introduce endogeneity concerns. To address this issue, the study applies the propensity score matching (PSM) approach to mitigate endogeneity arising from selection bias and to obtain more robust estimation results. A 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching strategy is implemented, incorporating all predefined control variables as covariates (Wang Q. et al., 2025). Table 4 reports the results of the balance test. The results show that after PSM adjustment, the absolute standardized deviations of all covariates fall below 5%. Furthermore, the comparison of kernel density curves indicates that covariate differences between the treatment and control groups are substantially reduced, thereby satisfying the balance test criteria. The PSM-DID estimation results reported in Column (4) of Table 3 show that the coefficient of the core explanatory variable is significantly positive at the 1% level. This finding demonstrates that the water resource tax policy exerts a robust and statistically significant positive effect on firms’ sustained green innovation, thereby enhancing the validity and reliability of the research conclusions.

5.4 Endogeneity treatment

Although the preceding sections have confirmed the robustness of the empirical results through multiple approaches, potential endogeneity issues may still introduce bias into the estimation results. To further address potential endogeneity concerns—such as sample selection bias, omitted variables, and model specification errors—this study adopts the following approaches based on prior research: (1) entropy balancing matching; (2) Heckman two-stage model; and (3) regression discontinuity design. These methods effectively mitigate the influence of endogeneity on the empirical results, and the main conclusions remain consistent.

5.4.1 Entropy balancing matching method

Following (Hainmueller, 2012), this study employs the entropy balancing method to adjust the mean, variance, and skewness of third-order moments for each sample’s characteristic covariates. After this adjustment, weighted regression is performed to achieve the closest possible balance across sample covariates. The regression results are reported in Column (5) of Table 3. The marginal effect of the water resource tax implementation remains significantly positive at the 1% level, reinforcing the conclusions of the benchmark regression.

5.4.2 Heckman test

This study employs a Heckman two-stage model to control for potential sample selection bias, as described below. The instrumental variable for the treati is defined as the average proportion of groundwater supply to total water supply in pilot regions during the 5 years preceding policy implementation. The rationale is that regions with higher groundwater supply ratios are more likely to attract government attention and be designated as pilot areas for water resource taxation, thereby satisfying the “relevance” condition of the IV. Furthermore, groundwater availability—being an exogenous natural characteristic—is not influenced by individual firm behavior, thereby satisfying the exogeneity condition of the IV (Wang Q. et al., 2025; Yao et al., 2023). Specifically, in the first-stage probit model of the Heckman two-stage approach, did is specified as the dependent variable. The inverse Mills ratio (IMRi,t) is derived from the first-stage regression and subsequently included as a correction term in the second-stage model. Table 5 reports the estimation results of the Heckman two-stage model. Column (1) reports the first-stage results, showing that the IV coefficient is significantly positive, indicating that regions with higher groundwater supply ratios are more likely to be designated as pilot areas for water resource taxation. Column (2) shows that the results remain robust after controlling for sample selection bias through the inclusion of the inverse Mills ratio (IMR).

5.4.3 Regression discontinuity design

Since not all regions with high groundwater supply shares were actually subject to treatment, this study employs a regression discontinuity (RRD) design to further address potential endogeneity issues. A fuzzy regression discontinuity (FRD) framework is adopted and estimated using the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method. In this context, Lc denotes the driving variable, standardized by subtracting the average groundwater supply share across all regions from that of the pilot regions during the 5 years preceding the implementation of the water resource tax. The variable being processed is water. Figure 5 illustrates a distinct discontinuity in corporate sustainable green innovation at the cutoff point, providing preliminary evidence that regions implementing water resource taxes exhibit higher levels of sustainable green innovation.

The specific RDD estimation results are reported in Table 6. Parts 1 and 2 present the first-stage regression results. After controlling for relevant variables and incorporating firm- and time-fixed effects, the first-stage results indicate that firms located in regions implementing water resource taxes supply approximately 1% less water than those in regions without such taxes, significant at the 1% level. Moreover, a higher level of water supply is associated with a lower level of sustained green innovation among enterprises. The second-stage estimation results, presented in Part 3, indicate that the implementation of water resource taxes has a statistically significant positive effect on firms’ sustained green innovation. These findings further validate the robustness of the estimation results.

6 Further analysis

6.1 Path analysis

This study employs the classic three-step mediation analysis to investigate whether corporate financing constraints (WW) and green investor participation (Green) mediate the relationship between water resource tax reform and sustained green innovation in enterprises. Specifically, the following model is specified:

In Equations 5, 6, Mit denotes the set of mediating variables. Equation 1 represents the first stage of the mediation analysis. The regression results from the mediation analysis are reported in columns (1)–(4) of Table 7. The data in columns (1) and (3) show that the dummy variable for the water resource tax policy has a significantly negative coefficient at the 1% level and a significantly positive coefficient at the 5% level, respectively. This suggests that the policy effectively alleviates financing constraints for water-intensive industrial enterprises and attracts green investors. Columns (2) and (4) reveal that financing constraints and green investor participation are significantly negatively and positively correlated, respectively, with firms’ continuous green innovation. Additionally, the coefficients of the policy variable in the second-stage regression decrease relative to the first stage, indicating that the two mediating variables partially mediate the effect of the water resource tax on continuous green innovation.

This study also validates the significance of the indirect effects through Sobel tests and bootstrap resampling procedures. Moreover, the mediation analysis results based on SEM reveal that financing constraints exert partial mediating effects (Wang et al., 2025c), thus providing strong support for Hypothesis 2.

6.2 Moderation effect analysis

To examine the moderating effect of water resource taxes on enterprises’ sustained green innovation, we specify the following model:

Building on Equations 1, 7 introduces the moderator variable M1it (MEA) and its interaction term with the core explanatory variable. The regression analysis results in Table 7 (item 5) show that the coefficient of the didit variable is significantly positive at the 1% level. Furthermore, managerial environmental awareness has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between water resource tax reform and continuous green innovation, as indicated by the significant positive interaction coefficient. In other words, under the constraints of the water resource tax, enterprises with higher environmental awareness demonstrate greater continuous green innovation capabilities. Moreover, the moderation effect diagram in Figure 6 shows that the slope of the dotted line representing high managerial environmental awareness is steeper than the slope of the solid line representing low managerial environmental awareness, providing strong support for Hypothesis 3.

6.3 Heterogeneity analysis

6.3.1 Individual characteristics: ownership and size

Based on Hypothesis 1, this section investigates how differences in firm characteristics—specifically ownership structure and firm size—affect sustained green innovation. We performed grouped regression analyses for each subsample. As shown in Column (1) of Table 8, after controlling for time variables and industry fixed effects, the water resource tax reform significantly impacts continuous green innovation in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) at the 5% significance level. In contrast, the corresponding coefficient for non-state-owned enterprises is statistically insignificant. This suggests that the policy has a stronger impact on the OIP of SOEs.

As shown in Column (3) of Table 8, the coefficient for the core explanatory variable is significantly positive at the 5% significance level for large enterprises. This suggests that water resource tax reform significantly promotes green innovation in larger SOEs but has no significant effect on small enterprises. A plausible explanation is that SOEs, due to their strategic importance, face less market pressure and benefit from political advantages. Large enterprises, benefiting from superior resource endowments, are better positioned to invest in green innovation. In contrast, small enterprises often face constraints in R&D resources and capabilities, which can lead to technology spillover effects and path dependency, especially in high-tech and policy-intensive sectors.

6.3.2 Regional characteristics

Given regional differences in resource endowments and economic development, this study further divides the sample into eastern and non-eastern regions for grouped regression analysis. This approach facilitates examining the heterogeneous effects of water resource tax reform on continuous green innovation (OIP) across regions. As shown in Table 9, water resource tax reform significantly promotes continuous green innovation among enterprises in eastern regions, while the effect in non-eastern regions is comparatively weaker. This may be attributed to the first-mover advantages in capital, technology, and talent in eastern regions, which enhance their capacity to foster continuous green innovation capabilities among enterprises.

6.3.3 Industry characteristics: high-tech industry

In accordance with the CSRC (2012) industry classification standards and the National Key Supported High-Tech Fields, firms identified as belonging to high-tech industries are assigned a value of 1, while all others are assigned a value of 0. This classification criterion is used to categorize the sample. As shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 9, the implementation of the water resource tax has a significant and sustained effect on promoting green innovation among high-tech enterprises, whereas its impact on enhancing the persistent innovation levels of non-high-tech enterprises is not statistically significant. This disparity can be attributed to the fact that policies associated with the water resource tax provide stronger incentives and support to high-tech firms, such as fiscal subsidies, tax incentives, and grants for water-saving technological upgrades, thereby fostering greater enthusiasm and persistence in innovation. In contrast, non-high-tech enterprises often face more intense market competition and financial constraints, which may reduce their investment in green initiatives and weaken their motivation for sustained green innovation.

7 Conclusions and policy implications

7.1 Conclusions

As industrialization progresses, the extensive production practices of water-intensive industries place significant pressure on natural resources and the ecological environment. Issues such as inefficient water management and underdeveloped institutions have prevented enterprises from fully internalizing the costs of water use and pollution discharge, thus hindering the development of efficient and sustainable water resource management models. These challenges have exacerbated water scarcity. Therefore, an urgent priority is to promote green and low-carbon production and water use patterns in water-intensive industries, facilitating their transformation into water-efficient and innovative enterprises. This shift will significantly contribute to high-quality economic development, aligning with the construction of a “water ecological civilization” and relevant national strategic objectives.

This empirical study uses panel data from water-intensive enterprises listed on China’s A-share market between 2012 and 2022 to systematically examine the effects of water resource tax reform on sustained green innovation. Using a difference-in-differences (DID) model to create a quasi-natural experiment, the study finds the following: First, water resource tax reform significantly stimulates sustained green innovation in water-intensive industries; second, the mechanism analysis shows that the reform effectively promotes ongoing innovation for sustainability (OIP) by alleviating financing constraints and encouraging green investor participation; third, managerial environmental awareness positively moderates the relationship between policy and corporate OIP. Finally, the positive policy effects of the water resource tax are more pronounced among state-owned enterprises, large firms, enterprises located in eastern regions, and high-tech firms, which tend to exhibit relatively weaker intrinsic motivation to pursue OIP.

7.2 Policy recommendations

The following policy recommendations emerge from the findings of this study:

1. Continuously advance water conservation and pollution reduction strategies while refining water resource tax policies. First, optimize tax incentives for investments in water-saving technologies and dynamically adjust subsidies based on the evolving water resource tax policies. Second, strictly enforce entry requirements for water-efficient enterprises and impose market access restrictions on non-compliant entities. High-water-consumption and heavily polluting enterprises must adopt comprehensive water-saving and pollution-reduction measures across the entire process, from source control to end-of-pipe treatment. This can be achieved through compensation mechanisms and leveraging the first-mover advantage of sustained green innovation. In other words, the design and management of water resource taxes should fully account for the constraints imposed by sustained green innovation. Furthermore, in pilot provinces prioritized for tax reform, water-intensive enterprises should serve as benchmarks to promote the widespread adoption and scaling of water resource tax policies, transforming local successes into broader applications.

2. Tailor policies to address enterprise and industry differences, abandoning a one-size-fits-all approach. Given the varying impacts of water resource taxes on the sustainability of green innovation across enterprises, differentiated support policies should be implemented. For instance, governments should increase support for non-owned, small-scale, and water-intensive enterprises in central and western regions. Through multi-dimensional measures such as talent recruitment, financial support, and resource allocation, they should foster a more favorable financing environment for green innovation enterprises. For non-high-tech enterprises, governments should coordinate multiple environmental policies and apply pressure through strict oversight to drive sustained green innovation.

Optimize external resources and enhance internal environmental focus. Policymakers and enterprises must guard against financing constraints and external green investment injections while prioritizing efficient allocation of internal resources. Governments should alleviate corporate financing pressures through innovation subsidies, streamlined financing channels, and supporting policies—measures designed to drive continuous innovation for improved water efficiency and green development. Concurrently, enterprises must avoid short-termism by leveraging external investor oversight mechanisms to foster long-term sustainability. Furthermore, heightened environmental awareness will incentivize enterprises to prioritize green investments in water conservation, consumption reduction, and wastewater treatment, thereby boosting production efficiency. Ultimately, these initiatives will foster a virtuous cycle of “survival of the fittest,” comprehensively elevating industry competitiveness.

7.3 Research limitations

Due to data constraints, this paper still has several shortcomings. First, the measurement of indicators remains limited. This study relies exclusively on patent data to measure sustained green innovation, which restricts the ability to conduct a multidimensional assessment of corporate green innovation practices. Moreover, future analyses could incorporate policy implementation intensity or regional tax rate variables as core explanatory factors. Second, the sample period requires extension. Given recent advancements in enterprises’ sustainable green innovation, extending the sample observation period in future research would yield more current and representative results. Finally, the classification of influence pathways remains overly simplistic. The current research focuses exclusively on the impact mechanisms associated with external financial constraints and regulatory supervision. Future studies could incorporate a more comprehensive set of tertiary indicators—including those related to finance, human resources, and other dimensions—to systematically examine the channels through which water resource taxes affect the sustainable green innovation of water-intensive enterprises. This would offer more comprehensive policy insights to inform government decision-making.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

XX: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. HT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JL: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 24CJY077), Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation (Grant No. 23YJC790160), and Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Project for Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi Province (Grant No. W20231037), Special Program for Enhancing Research Capabilities of Young Faculty at Inner Mongolia Agricultural University (Grant No. BR220205).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., Bursztyn, L., and Hemous, D. (2012). The environment and directed technical change. Am. Economic Review 102 (1), 131–166. doi:10.1257/aer.102.1.131

Acemoglu, D., Akcigit, U., Hanley, D., and Kerr, W. (2016). Transition to clean technology. J. Political Economy 124 (1), 52–104. doi:10.1086/684511

Bacal, P., and Boboc, N. (2015). Economic and financial aspects of water management in the Dniester basin (the sector of the Republic of Moldova). Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 9 (1), 33–45. doi:10.1515/pesd-2015-0002

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Management 17 (1), 99–120. doi:10.1177/014920639101700108

Beck, T., Levine, R., and Levkov, A. (2010). Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. Journal Finance 65 (5), 1637–1667. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01589.x

Calel, R., and Dechezleprêtre, A. (2016). Environmental policy and directed technological change: evidence from the European carbon market. Rev. Economics Statistics 98 (1), 173–191. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00470

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., and Miller, D. L. (2011). Robust inference with multiway clustering. J. Bus. Econ. Statistics 29 (2), 238–249. doi:10.1198/jbes.2010.07136

Cao, D. (2025). The impact of green investor entry into buyer firms on supplier green innovation. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 103, 104517. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2025.104517

Chen, Y.-S. (2008). The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Business Ethics 81, 531–543. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9522-1

Clausen, T., Pohjola, M., Sapprasert, K., and Verspagen, B. (2012). Innovation strategies as a source of persistent innovation. Industrial Corp. Change 21 (3), 553–585. doi:10.1093/icc/dtr051

Clinch, J. P., Dunne, L., and Dresner, S. (2006). Environmental and wider implications of political impediments to environmental tax reform. Energy Policy 34 (8), 960–970. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2004.08.048

Dechezleprêtre, A., and Sato, M. (2017). The impacts of environmental regulations on competitiveness. Rev. Environmental Economics Policy. doi:10.1093/reep/rex013

Goulder, L. H., and Schneider, S. H. (1999). Induced technological change and the attractiveness of CO2 abatement policies. Resour. Energy Economics 21 (3-4), 211–253. doi:10.1016/s0928-7655(99)00004-4

Hainmueller, J. (2012). Entropy balancing for causal effects: a multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Polit. Analysis 20 (1), 25–46. doi:10.1093/pan/mpr025

Hall, B. H., and Lerner, J. (2010). “The financing of R&D and innovation,” in Handbook of the economics of innovation. Elsevier, 609–639.

Hambrick, D. C., and Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Management Review 9 (2), 193–206. doi:10.2307/258434

He, L., and Chen, K. (2021). Can China’s “tax-for-fee” reform improve water performance–evidence from Hebei Province. Sustainability 13 (24), 13854. doi:10.3390/su132413854

Höglund, L. (1999). Household demand for water in Sweden with implications of a potential tax on water use. Water Resour. Res. 35 (12), 3853–3863. doi:10.1029/1999WR900219

Jaffe, A. B., Newell, R. G., and Stavins, R. N. (2005). A tale of two market failures: technology and environmental policy. Ecol. Economics 54 (2-3), 164–174. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.12.027

Jiang, X., Tong, J., and Wang, S. (2021). Evaluation of the effectiveness of the water resources tax reform pilot program and the implementation path for full-scale rollout. Local Finance Res. (11), 66–74.

Jiang, G., Peng, J., Liang, X., and Pan, J. (2025). Supply chain digitization and continuous green innovation: evidence from China. Energy Econ. 142, 108158. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2024.108158

Kamaruddeen, A. M., Yusof, N. A., and Said, I. (2010). Innovation and innovativeness: difference and antecedent relationship. Icfai Univ. J. Archit. 2 (1), 66–78.

Kang, L., Lv, J., and Zhang, H. (2024). Can the water resource fee-to-tax reform promote the “Three-Wheel Drive” of corporate green energy-saving innovations? Quasi-natural experimental evidence from China. Energies 17 (12), 2866. doi:10.3390/en17122866

Kilimani, N., Van Heerden, J., and Bohlmann, H. (2015). Water taxation and the double dividend hypothesis. Water Resour. Econ. 10, 68–91. doi:10.1016/j.wre.2015.03.001

Kraemer, P. E. (2003). Orogenic shortening and the origin of the Patagonian orocline (56 S. Lat). J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 15 (7), 731–748. doi:10.1016/S0895-9811(02)00132-3

Li, T., and Luo, N. (2024). Dividend payments and persistence of firms’ green innovation: evidence from China. Sustainability 16 (18), 7975. doi:10.3390/su16187975

Li, J., and Wang, Z. (2023). A study on the effects of water resource tax reform from the dual perspectives of water conservation and emission reduction: evidence from micro-level industrial enterprises. Ind. Econ. Rev. (06), 117–134. doi:10.19313/j.cnki.cn10-1223/f.20230605.001

Li, J., Ding, T., and Liang, L. (2024). Does water resource fee to tax policy help reduce water pollution in China? Water Econ. Policy 10 (01), 2350007. doi:10.1142/S2382624X23500078

Liu, C. (2023). Can water resource tax reform improve the environmental performance of enterprises? Evidence from China’s high water-consuming enterprises. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1155237. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2023.1155237

Liu, Y., Huang, S., and Huang, Z. (2022). Can water resource tax reform achieve a double dividend effect? Tax Res. (09), 55–63. doi:10.19376/j.cnki.cn11-1011/f.2022.09.021

Liu, R., Hou, M., Jing, R., Bauer, A., and Wu, M. (2024). The impact of national big data pilot zones on the persistence of green innovation: a moderating perspective based on green finance. Sustainability 16 (21), 9570. doi:10.3390/su16219570

Liu, L., Hu, W., Wang, F., and Yang, L. (2025a). Making sustained green innovation in firms happen: the role of CEO openness. Sustainability 17 (11), 5098. doi:10.3390/su17115098

Liu, M., Zhao, J., and Liu, H. (2025b). Digital transformation, employee and executive compensation, and sustained green innovation. Int. Rev. Financial Analysis 97, 103873. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2024.103873

Luo, Y., Wu, C., and Lu, Z. (2022). Analysis of the effectiveness of water resource tax pilot policies: evidence from Hebei Province. Arid Zone Resour. Environ. 36 (06), 47–55. doi:10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2022.146

Mulyanti, D., Perwira, I., Muttaqin, Z., and Sugiharti, D. K. (2024). The legal policy role of groundwater tax on water resources conservation in Indonesia. J. Law Sustain. Dev. 12 (2), e1673. doi:10.55908/sdgs.v12i2.1673

Ouyang, R., Mu, E., Yu, Y., Chen, Y., Hu, J., Tong, H., et al. (2024). Assessing the effectiveness and function of the water resources tax policy pilot in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26 (1), 2637–2653. doi:10.1007/s10668-022-02667-y

Palmer, K., Oates, W. E., and Portney, P. R. (1995). Tightening environmental standards: the benefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? J. Economic Perspectives 9 (4), 119–132. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.119

Pan, J., Bao, H., Cifuentes-Faura, J., and Liu, X. (2024). CEO’s IT background and continuous green innovation of enterprises: evidence from China. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 15 (4), 807–832. doi:10.1108/SAMPJ-07-2023-0497

Porter, M. E., and Linde, C. V. D. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Economic Perspectives 9 (4), 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Rastegar, H., Eweje, G., and Sajjad, A. (2024). The impact of environmental policy on renewable energy innovation: a systematic literature review and research directions. Sustain. Dev. 32 (4), 3859–3876. doi:10.1002/sd.2884

Sharif, A., Kocak, S., Khan, H. H. A., Uzuner, G., and Tiwari, S. (2023). Demystifying the links between green technology innovation, economic growth, and environmental tax in ASEAN-6 countries: the dynamic role of green energy and green investment. Gondwana Res. 115, 98–106. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2022.11.010

Song, Y., Gao, W., and Lee, C.-C. (2025). Does China's green credit interest subsidies policy promote enterprises' green technology innovation quality? Based on the perspective of financial and fiscal coordination. J. Environ. Manag. 390, 126366. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.126366

Stucki, T., Woerter, M., Arvanitis, S., Peneder, M., and Rammer, C. (2018). How different policy instruments affect green product innovation: a differentiated perspective. Energy Policy 114, 245–261. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.11.049

Sun, Y., Zhi, Y., and Zhao, Y. (2021). Indirect effects of carbon taxes on water conservation: a water footprint analysis for China. J. Environ. Manag. 279, 111747. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111747

Sun, H., Bai, T., Fan, Y., and Liu, Z. (2024). Environmental, social, and governance performance and enterprise sustainable green innovation: evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 31 (4), 3633–3650. doi:10.1002/csr.2761

Tang, H., Tong, M., and Chen, Y. (2024). Green investor behavior and corporate green innovation: evidence from Chinese listed companies. J. Environ. Manag. 366, 121691. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121691

Tian, G.-L., Wu, Z., and Hu, Y.-C. (2021). Calculation of optimal tax rate of water resources and analysis of social welfare based on CGE model: a case study in Hebei Province, China. Water Policy 23 (1), 96–113. doi:10.2166/wp.2020.118

Triguero, A., and Córcoles, D. (2013). Understanding innovation: an analysis of persistence for Spanish manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 42 (2), 340–352. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2012.08.003

Vallés-Giménez, J., and Zárate-Marco, A. (2013). Environmental taxation and industrial water use in Spain. Investigaciones Regionales-J. Regional Res. (25), 133–162.

Wang, X., Liu, C., and Chen, G. (2020). Research on China's unified water resources tax rate system. J. Northwest Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 50 (01), 49–56. doi:10.16152/j.cnki.xdxbzr.2020-01-007

Wang, Z., Cao, Y., and Lin, S. (2021). The characteristics and heterogeneity of environmental regulation's impact on enterprises' green technology innovation——based on green patent data of listed firms in China. Sci. Stud. 39 (05), 909–919+929. doi:10.16192/j.cnki.1003-2053.20200916.001

Wang, Q., Shimada, K., and Yuan, J. (2025a). Water resource tax policy and micro environmental performance improvement in China's water-intensive industries. Water Resour. Econ. 49, 100258. doi:10.1016/j.wre.2025.100258

Wang, Y., Lin, X., and Ni, H. (2025b). Impact of production tax policy on water resource and economy: a case study of wenling city. Sustainability 17 (18), 8117. doi:10.3390/su17188117

Wang, Y., Shi, M., Zhao, Z., Liu, J., and Zhang, S. (2025c). How does green finance improve the total factor energy efficiency? Capturing the mediating role of green management innovation and embodied technological progress. Energy Econ. 142, 108157. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2024.108157

Wei, M. (2023). Analysis of the water ecological environment protection effects of water resources tax and environmental protection tax: an analysis based on wastewater reduction effects. Tax Res. (05), 112–119. doi:10.19376/j.cnki.cn11-1011/f.2023.05.019

Wen, J., Ji, X., and Wu, X. (2025). The impact of water resources tax reform on corporate ESG performance: patent evidence from China. Water 17 (7), 959. doi:10.3390/w17070959

Xi, W. (2018). The origin and development of China’s water resources tax based on the research of foreign taxation experience. Eur. J. Bus. Econ. Account. 6 (3), 32–33.

Xu, W., and Li, M. (2024). Green tax system and corporate carbon emissions – a quasi-natural experiment based on the environmental protection tax law. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 68, 2092–2122. doi:10.1080/09640568.2024.2307524

Xu, C., Gao, Y., Hua, W., and Feng, B. (2024a). Does the water resource tax reform bring positive effects to green innovation and productivity in high water-consuming enterprises? Water 16 (5), 725. doi:10.3390/w16050725

Xu, L., Li, Z., Fang, J., He, Z., and Zhang, X. (2024b). Can the water resources tax promote the water-saving innovation performance of high water consumption companies? Empirical analysis from the pilot provinces in China. J. Clean. Prod. 451, 141888. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141888

Yao, P., and Li, J. (2023). Determining industry by water: fee to tax of water resources and industrial transformation and upgrading. J. Stat. Res. 40 (08), 135–148. doi:10.19343/j.cnki.11-1302/c.2023.08.011

Yao, P., You, W., and Sun, J. (2023). How does the water resource ‘fee-to-tax' policy affect the over-investment of high water-consuming enterprises? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 33 (06), 105–115.

Ye, J., and Zhang, X. (2021). Water resources tax reform: evaluation of pilot texts and proposals for unified legislation. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 31 (08), 121–136. doi:10.12062/cpre.20210433

Yu, H., and Zhang, J. (2025). Do green investors empower companies to develop sustainably? A study based on the perspective of innovation investment and corporate governance levels. Finance Res. Lett. 79, 107263. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2025.107263

Zhang, B. (2022a). On the institutional optimization of water resource tax for public water supply. Tax Res. (05), 47–53. doi:10.19376/j.cnki.cn11-1011/f.2022.05.013