- 1Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Jammu, Jammu, India

- 2Department of Environmental Studies, Shyam Lal College (Evening), University of Delhi, Delhi, India

Globally, plastic waste generation has reached approximately 300 million tons annually, accounting for more than 10% of municipal solid waste, with over half of this waste ultimately disposed of in landfills. Landfilling, as the most common waste management practice worldwide, is estimated to store 21%–42% of all plastics produced globally. Landfills represent dynamic environments where plastics undergo fragmentation and degradation via physical, chemical, and biological processes, leading to the formation of more complex pollutants known as microplastics (MPs). MPs are categorized as follows: “primary MPs,” deliberately produced small plastic particles, and “secondary MPs,” which are formed as a result of breaking down of larger plastic materials. Consequently, landfills act not only as sinks for plastic waste but also as significant sources and continuous emitters of MP pollution. MPs, composed of different polymers such as polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), are present in landfills and in their leachate. MPs are persistent, nonbiodegradable pollutants and often act as the carriers of other contaminants. Due to the uneven surface and coarse texture, MPs strongly adsorb and transport a range of other hazardous micropollutants, including heavy metals, antibiotics, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and persistent organic pollutants. Such interactions considerably increase the ecological threat of landfill leachates to terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. In this review, we consolidate current scientific evidence on the sources, origin, formation, polymeric compositions, and environmental behaviors of MPs in landfill environments and also highlight the influence of landfill age on MP abundance, diversity, and physicochemical properties. Additionally, in the review, we examine the emerging ecological and human health risks associated with landfill-derived MPs, including their role as vectors of toxic chemicals and pathogens. Despite increasing awareness of MP contamination, literature specifically addressing landfills as active origins of MPs remains scarce. By synthesizing available knowledge, in this study, we underscore that landfills function as both reservoirs and significant emission sources of MPs, contributing to broader challenges of global plastic pollution. The findings highlight the critical need for systematic monitoring, advanced leachate treatment technologies, and integration of circular economy principles to mitigate risks associated with landfill-derived MPs and to ensure sustainable waste management strategies.

1 Introduction

Plastic undeniably remains a necessary element in contemporary daily life. Its evolution has seen an exponential growth, particularly since the 1950s. Records indicate that the yearly global production of plastics exceeds 335 million tons, firmly solidifying its position as an essential component of modern life (He et al., 2021). Recent findings indicate that global plastic consumption is projected to increase from 464 million tons in 2020 to 884 million tons by 2050 (Dokl et al., 2024). A considerable proportion of plastics, approximately 50%, are utilized solely for disposable purposes, contributing to the massive accumulation of abandoned plastics in the environment and consequently resulting in severe environmental repercussions (Hopewell et al., 2009).

Roughly 300 million tons of plastic waste, comprising more than 10% of the yearly generated municipal solid waste (MSW), is produced on a global scale, with more than half of it ending up in landfills (Huang et al., 2022). According to the World Bank UN report (2022), approximately 2.01 billion tons of MSW is generated annually. Out of the total MSW, the plastic waste fraction is 12% at the global level (Singh et al., 2023). Gourmelon (2015) reported that in Asia, plastic use is 20 kg/capita/year, whereas in Western Europe and North America, the average plastic use is 100 kg/capita/year.

Developed countries commonly opt for sanitary landfill for waste management, whereas developing countries resort to open dumping. Despite efforts to reduce its usage, plastic remains a popular choice due to its portability, durability, and affordability. In the environment, plastics undergo degradation through various processes, including physical, chemical, and biological means such as hydrolysis, photodegradation, thermal oxidation, mechanical abrasion, and biodegradation (Andrady, 2015). Within landfills, plastic waste undergoes degradation, resulting in the formation of more complex pollutants known as microplastics (MPs). As plastics undergo degradation, their size decreases, giving rise to the formation of MPs and nanoplastics (NPs). These minuscule particles pose a more insidious threat due to their inconspicuous nature. MPs are defined as plastic pieces measuring less than 5 mm, whereas NPs refer to plastics with sizes in the submicron scale. The pioneering detection of MPs was made in the vast expanse of oceans (Kilponen, 2016). These emerging pollutants, MPs, have been extensively found in both marine and terrestrial ecosystems (Su et al., 2019).

MP particles can be categorized into two types: “primary microplastics,” deliberately produced small plastic particles, and “secondary microplastics,” which are formed as a result of larger plastic materials breaking down through chemical, physical, and biological actions (Arthur et al., 2009). It is estimated that a staggering 5 trillion MP particles, weighing in at approximately 243,000 tons, are currently floating in our oceans due to the gradual degradation and deposition of these particles. This poses a significant threat to marine life (Eriksen et al., 2014). Furthermore, additional research has uncovered the presence of NPs in marine environments (Piccardo et al., 2020). It is not only the ocean that is affected by the abundance of MPs but also other environmental mediums such as wastewater, drinking water, surface water, and even landfills (He et al., 2021; Eriksen et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2021; Nizzetto et al., 2016).

Amid the litter of plastic waste, MPs raise grave concerns owing to their extended lifespan in the environment, small particulate size, expansive surface area, and ability to infiltrate cells and cause harmful consequences. Both primary and secondary MPs pose a threat to human health, as highlighted by Wang et al. (2021). These minuscule plastic particles can be introduced into our surroundings through various means, including leaching, aerosolization, and landfill mining, as reported in studies by Afrin et al. (2020), He et al. (2019), and Yadav et al. (2020). Unregulated and poor handling of plastic waste would undoubtedly heighten the likelihood of MP leakage, as elucidated in a study by Huang et al. (2022). Secondary MPs are used in agriculture and industries after entering the environment. The degradation of such large plastic particles in the environment is caused by the weathering process or through high temperature, which are then decomposed into secondary plastic particles (Rillig et al., 2017).

The landfills used for waste disposal play a critical role in managing the global production of plastic waste, storing approximately 21%–42% of the total amount (Nizzetto et al., 2016). The process of dumping waste in these landfills and the development of industrial, agricultural, and technological processes all contribute to the release of primary and secondary MPs. These MPs then enter the terrestrial environment through material and energy flows (Afrin et al., 2020).

According to theoretical speculation, landfills serve as a significant repository for MPs. These MPs include minuscule plastic granules typically used in cosmetics and small fragments resulting from the degradation of larger plastic materials. Through airborne pathways, such as the dispersal caused by wind, these particles and fibers can travel from landfills to surrounding environments (Rillig et al., 2017). Leachate generated from MSW landfills is also a potential source for surface and groundwater contamination (Gupta et al., 2022; Gupta et al., 2024a; Gupta et al., 2024b).

Notably, landfill leachate is a vital source of secondary MPs that can enter sediments, air, and water resources (Singh et al., 2023). In fact, research workers such as Imhof et al. (2013) suggest that landfills may be a significant source of MPs in lakes. In Norway, experts in the fields of landfilling and hazardous substances have also expressed concerns about potential MP leakage from landfills (Sundt et al., 2014).

Two types of pollution sources can be identified in the generation of terrestrial MPs: point source and nonpoint source contamination (Horton et al., 2017). Point source pollution can be triggered by sewage sludge treatment, where primary MPs infiltrate the sewage and industrial wastewater, and then they enter the soil environment through sewage discharge (Horton et al., 2017; Zubris and Richards, 2005). Even though a significant percentage of MPs (ranging from 40% to 99.9%) are usually eliminated by wastewater treatment facilities during the secondary treatment process, numerous African nations suffer from inadequate wastewater infrastructure (Yang et al., 2022). On the other hand, nonpoint source pollution is predominantly caused by landfills, agriculture, and garbage settlements. Among the most substantial contributors to MPs in the ecosystem is the application of mulch in agriculture (Roy et al., 2011; Steinmetz et al., 2016). Activities such as landfill and surface deposits can produce particles that can be carried through the air by atmospheric displacement (Rillig et al., 2017). MPs possess the capability to adsorb persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals, subsequently transporting these contaminants or accumulating them in biota, thereby posing significant impacts on both human health and ecosystems (Bouwmeester et al., 2015).

Primary and secondary MPs originating from different primary and secondary sources enter the landfills. In addition to these, several other pollutants are also present in landfills, and MPs have the capability of adsorbing those pollutants. MPs from landfills might infiltrate leachate through rainwater. If the landfill is not properly engineered, then the MPs may migrate to groundwater sources in the vicinity of the landfill or other terrestrial locations. It has also been identified that landfills act as a source of input of MPs to the marine environment (Li et al., 2018).

Despite landfilling being the most common method for disposal of solid waste, landfills as a contamination source and hotspot of MPs have not been explored much. The present article focuses on reviewing landfills as sources of MPs and on understanding various processes in landfills that lead to the formation of MPs. This article has an overview of the polymer composition of MPs found in landfills and has reviewed the available scientific literature on MP occurrence patterns across landfills of different ages. The authors have also thrown light on MPs as vectors for various disease-causing pathogens and adsorbing other pollutants, thereby exacerbating the problem. To enhance understanding, the environmental risks and toxic effects of MPs on ecosystems, animals, and humans are discussed. This article provides new insights indicating that landfills are not only the ultimate sink for plastic waste but also significant sources of MPs.

2 Landfill as a source and origin of microplastics

Landfilling, the most common method used worldwide for waste management, is responsible for storing approximately 21%–42% of the total global production of plastic waste (He et al., 2019). The disposal of waste into landfills is a long-term process, spanning several decades. Buried in landfills, plastic waste undergoes extreme environmental conditions, such as varying leachate pH levels (ranging from 4.5 to 9), oxygen content, high salinity, fluctuating temperature, gas generation (CO2 and CH4), physical stress, and microbial degradation. These factors contribute to possible fragmentation of plastic into MPs, with small plastic debris carried away by leachate discharge (He et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019). The waste undergoes a multitude of processes within landfills: an initial aerobic biodegradation, a shift from aerobic to anaerobic conditions, acid formation and hydrolysis, the generation of methane through methanogenesis, and finally, maturation and stabilization (Enfrin et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2021). Each of these stages hastens the breakage of plastic and leads to the formation of secondary MPs (Ghosh et al., 2017). In addition, the presence of oxygen, light, and elevated temperatures during the early stages of landfill operation catalyzes the transformation of macroplastic fragments into MPs; thus, landfills contain both primary and secondary MPs (Singh et al., 2023). Primary MPs are micro-sized plastic particles that serve as integral components for various commercial purposes, acting as raw materials for production and as pellets in various industries (Cole et al., 2011). These essential particles can be found in a multitude of products, including cosmetics, toothpaste, hand wash, kitchen scrubs, kitchen foam, cleaners, and even biomedical products (Wang C. et al., 2021). In addition, synthetic fibers from clothing, polymer manufacturing and processing industries, and personal-care products (PCPs) also contribute to the presence of primary MPs (Browne et al., 2011; Lechner and Ramler, 2015). On the other hand, secondary MPs are the products of plastic debris breaking down, as highlighted by Song et al. (2017) and Su et al. (2019) (Figure 1). A large amount of plastic is buried in landfills. Landfills are the ultimate sink for plastic waste in the terrestrial ecosystem. The fragmentation of landfilled MPs will continue despite the absence of light and oxygen as a consequence of varying pH (4.5–9), temperatures (60 °C–90 °C), microbiota, compaction, and physical stress (Dehal et al., 2024) (Figure 2).

It is commonly hypothesized that landfills serve as a significant storage site for MPs, encompassing both minuscule plastic beads utilized in beauty products and minute plastic fragments resulting from the disintegration of larger plastics. These tiny particles of fibers can disperse from landfills into neighboring and surrounding environments through an airborne route (Su et al., 2019).

The main sources of MPs are the degradation of large-sized plastics, cosmetic products, textile fibers, and fish nets (Singh et al., 2023). Additionally, an array of human activities connected to the large-scale production of MPs, such as the microbeads found in pharmaceuticals and personal-care products (PPCPs) or specific MPs produced for targeted uses, frequently find their way into landfills. This waste, stemming from specialized industries and facilities that handle these items, can consequently introduce primary MPs into the leachate of landfills (Kabir et al., 2023). The deposition of MPs is heavily influenced by the age of the landfill, as evidenced by the distinct patterns exhibited by various types. The abundance and size distributions of MPs in both refuse and leachate also vary with the age of the landfill (He et al., 2019). As a result, macroplastics are the main contaminants in landfills, playing a key role in determining the levels of MPs present over varying landfill ages (Su et al., 2019). The issue of MP pollution has become a pressing concern on a global scale, particularly when compared to larger plastic particles (Su et al., 2019). These minuscule particles pose a more significant threat, as they have the ability to adsorb harmful substances from the leachate and can also be transported within organisms due to the leakage of leachate (Liu P. et al., 2019). It is widely recognized that the improper management of waste and human behavior are the primary sources of increased MP contamination in the environment (He et al., 2019). Various studies have reported the severe consequences of MP exposure on the growth and reproduction of organisms and even the health of humans (Wang et al., 2023).

According to the research by Dehal et al. (2024), the production, buildup, and discharge of MPs from landfills are part of a long-term process and occur over an extended period. These findings serve as the initial proof that landfills do not serve as the final destination for plastic waste; rather, they serve as potential origins for MPs.

2.1 Formation of MPs in landfills

The transformation of macroplastic waste into MPs within landfill sites is caused by a complex combination of biological, physical, and chemical processes. Initially, abiotic degradation breaks down the long chains of plastic into smaller chains. Subsequently, these abiotically degraded products undergo further degradation through biotic processes. The impact of oxygen, natural light, and elevated temperatures in the early stages of landfill activity leads to the breakdown of macroplastic fragments into MPs, as observed by Silva et al. (2021).

According to Shen et al. (2021), the combustion of large plastic materials serves as a significant contributor to the presence of MPs. Inside the bottom ash from MSW incineration facilities, 171 particles of MPs were obtained per kilogram of dry weight. Furthermore, it is important to note that the disposal of bottom ash in landfills can directly contribute to the presence of MPs in the environment. The high-energy UV-A and UV-B rays from sunlight are the primary driving force behind the photodegradation of plastic, as stated by Zhang et al. (2020).

MPs can arise after the disintegration of macroplastics within landfills. These environments function as repositories for the accumulation of plastic waste, which vary in size from macro to micro. Another significant contributor of MPs in landfills is wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). PCPs and pharmaceuticals act as the primary sources of MPs, which are purposefully incorporated into these products for a diverse range of uses (e.g., microbeads in cosmetics, toothpaste, capsules, paints, glitters, and cleaning agents). An unparalleled surge in the consumption of disposable masks during the COVID-19 pandemic era (2020–2022) has further intensified the presence of MPs in the environment (Jiang et al., 2023). A single disposable mask can release up to 6.4 × 108 MP fibers through natural weathering (Orona-Návar et al., 2022).

The sludge from WWTP contains a substantial quantity of MPs that are typically discarded in either landfills or open dumps (Dehal et al., 2024). According to Hou et al. (2021), the rise in humidity and heat during the aerobic stage can facilitate the development of breaks and fissures in plastics, ultimately resulting in the production of MPs. The toxic effect of wastewater is well documented in studies carried out by Verma et al. (2022a). The largest source of the cumulative genotoxic burden on ecosystems is urban waste. Among the micropollutants present in wastewater are pharmaceuticals, endocrine disruptors (EDCs), and heavy metals that can enter the body and have detrimental effects at cytotoxic and genotoxic levels (Verma et al., 2022b; Verma et al., 2023).

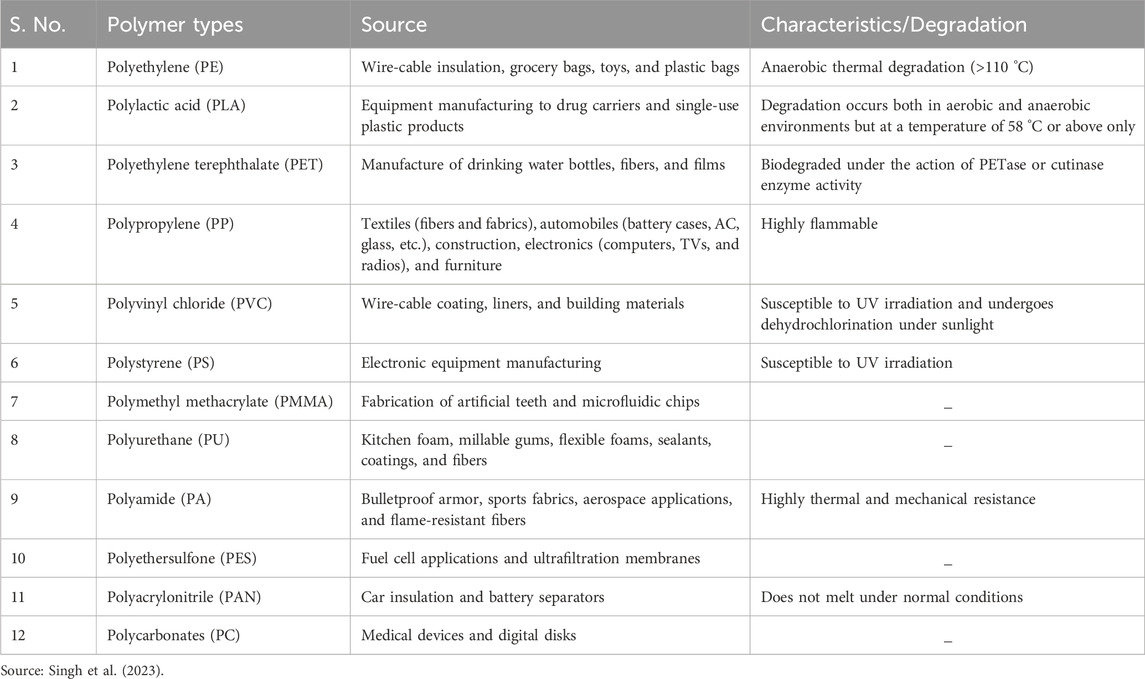

A wide variety of macroplastics composed of different polymers, each with its own unique degradation pathway, are present in the environment and landfills (Table 1). Among these, polyethylene (PE) is the most prevalent and resilient polymer, with a strong resistance to photooxidative degradation. This is due to the absence of light-absorbing molecules, known as chromophores, in its composition, making it impervious to the photodegradation process, as observed by Singh et al. (2023).

Another polymer, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), is a type of polyester polymer that undergoes degradation when exposed to sunlight. However, in landfills, where the lower layers of waste are not exposed to sunlight, photodegradation is not possible. Instead, thermal (>200 °C) oxidation and hydrolysis lead to the breakdown of macro-PET into smaller MPs, which eventually leach out into the environment (Chamas et al., 2020). The acidic pH found in landfills greatly accelerates the hydrolysis of PET. Alongside abiotic degradation processes such as thermal oxidation, photodegradation, and hydrolysis, PET in landfills can also undergo biotic degradation (Zhang et al., 2021), resulting in the formation of hydrolyzable polymers. These hydrolyzable polymers further promote biodegradation. Polylactic acid (PLA) is a burgeoning biologically sourced polyester that undergoes photooxidative or thermal-oxidative degradation. This process can occur in aerobic or anaerobic surroundings. Notably, PLA is a hydrolyzable polymer that is susceptible to biotic degradation, as evidenced by the findings of Zhang et al. (2021). Polypropylene (PP) is a cost-effective polymer that has found wide applications in various industries. However, compared to its counterpart PE, PP is less stable due to the presence of tertiary carbon. This tertiary carbon is highly vulnerable to oxidative attack, as pointed out by Gijsman and Sampers (1997). This chemical reaction occurs in landfills, where the C–H bond in PP breaks down and forms polystyrene radicals in anaerobic conditions, as observed in studies by Singh et al. (2023).

A remarkably lightweight polymer existing in both solid and foam forms as a type of plastic polymer is polystyrene (PS). However, due to the inclusion of a phenyl ring, it is prone to the process of photodegradation, as discovered by Zhang et al. (2021). This degradation is further exacerbated in the anaerobic conditions commonly found in landfills, where the C–H bond in polystyrene is cleaved, resulting in the production of a polystyle radical.

Li et al. (2021) reported 40 varied forms of plastics, such as PP, PE, PS, PET, and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), in the leachate. As the utilization of plastic goods has burgeoned in recent times, an escalating amount of plastic waste has been entering landfills. The specific type of MPs present serves as a crucial factor in determining their origin. For instance, PET arises from the decomposition of plastic bottles (Westerhoff et al., 2008), whereas high-density polyethylene (HDPE) results from cleaning products, and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) is sourced from discarded plastic packaging (Sogancioglu et al., 2017). The type of MPs detected in the leachate reveals the plastic product consumption patterns, with PP being strongly linked to the automotive industry, medical applications, and consumer goods. The increased adoption of personal protective equipment (PPE) will inevitably lead to a higher concentration of PET in the environment (Wang et al., 2023).

2.2 Types of microplastic polymers found in landfill leachate

The polymer composition of MPs varies based on the composition of MSW and the environmental conditions in a given region. The type of polymers in landfill leachate also varies based on the stages (young/old and active/closed) of the landfill. Variations in polymer types in landfill leachate show the consumption pattern of plastic products (Kabir et al., 2023). Several studies have reported MP polymer composition. Su et al. (2016) detected and identified the polymer types using µ-FTIR, which included PE, cellophane, ethylene–propylene copolymer (EPM), PET, PP, PVC, polyamide (PA), polystyrene (PS), and other polymers.

Su et al. (2019) had earlier reported that among the identified MPs in leachate samples, the dominant class of MPs detected included cellophane (45.12%), followed by PE, PP, and PS, which accounted for 9.76%, 8.54%, and 8.54%, respectively. Su et al. (2016), in another study, also found that the most common type of MPs in the sediments of Taihu Lake was cellophane. Cellophane has been defined as MPs in a UNEP report and recent studies, is a typical semi-synthetic material, and is the most popular material for packaging a variety of food items, batteries, and cigars (Su et al., 2016; UNEP and Lessons, 2016; Yang et al., 2015).

According to the findings revealed by Huang et al. (2022), only three types of polymers, namely, PE, PP, and PS, accounted for a substantial 70% of the overall polymers found in MPs within a landfill located in Shanghai, China. Additionally, Nayahi et al. (2022) revealed that in a landfill in Thailand, these polymers (PE, PP, and PS) accounted for significant proportions of 16.16%, 19.36%, and 12.41%, respectively, in the overall composition. For refuse samples, the highest abundance in terms of MP number was represented by PE; and PE, polyether urethane (PEUR), PS, EPM, and PP polymers constituted >60% of all MPs identified in refuse. The main sources of PE MPs are packaging, containers, and PCPs (such as body and facial scrubs). PE is the most commonly used plastic in the world, accounting for 34% of the total plastics market (Geyer et al., 2017). Additionally, PP, PS, PVC, and PET are also the most widely used plastics in industrial activities and daily life. Therefore, these are important contributors to MPs in landfills. The plastic waste in landfills is primarily derived from household and industrial sources. The composition of MPs (i.e., PE, PP, PS, PVC, PU, PA, and PET) plays a vital role in their deposition, suspension in the water column, and the ability to float. PE materials usually sink below the upper-surface water, whereas materials such as plastic films, polyester resin, and soft drink bottles tend to sink at the ocean’s floor (Rakesh et al., 2021).

Apart from frequently identified polymers in freshwater bodies, such as rivers and sediments, and also in coastal waters, such as PE, PP, and PS (Klein et al., 2015; Song et al., 2018), copolymers were also detected in landfills. EPM, a class of synthetic rubber produced by copolymerizing ethylene and propylene, is used to produce products used in automotive engines, electrical wiring, and construction. EPM was observed to account for 9.09% of the total MPs in waste but was detected at lower levels in rivers and oceanic environments (Hu et al., 2018; Tanaka and Takada, 2016; Vianello et al., 2013). Ethylene–vinyl acetate copolymer (EVA), a copolymer of ethylene and vinyl acetate, is widely used as a thermoplastic and elastomeric material in melt adhesives and coatings, photovoltaic modules, and agricultural films (Carraher, 2017; Czanderna and Pern, 1996). In a study by Su et al. (2019), EVA was detected with an abundance of 1–4 items/g in waste. Therefore, the abundances of MPs and polymer composition in the landfills directly reflect the consumption and current situation of plastic products.

2.3 Various forms of microplastics

Typically, MPs exhibited various forms, including, but not limited to, granules, fibers, films, rods, and fragments, among environmental samples (Vianello et al., 2013) (Figure 3). Su et al. (2019) have substantiated that the MPs preserved in the leachate primarily took on the shape of fibers, granules, and fragments, with the main share being accounted for by fibers at approximately 60%, trailed by granules and fragments at 24.62% and 15.38%, correspondingly. In addition, it was also established that fibers constituted the ultimate form of MPs across sludge and wastewater, primarily emanating from garment washing and the discharge of the fiber production industry (Li et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2016).

As observed in the study conducted by Fernandes et al. (2022), the most common shape found in sediment samples was fragments (39%), followed by fibers (34%) and pellets (21%). Among all the research studies carried out on the beaches along Latin America, fragments and pellets were the most common shapes found. Whereas fibers and fragments were the most dominant MPs in Asia, Europe, and the Americas, African lakes were dominated by pellets (Yang et al., 2022). Extensive small-scale fishing activities in African lakes perhaps contributed to the dominance of pellets as beads and fishing lines are a major source of pellets (Oni et al., 2020).

The comprehensive review by Orona-Návar et al. (2022) revealed that MPs were abundantly found in beach and marine sediments and in freshwater across the region. The dominant forms of MPs in Latin America and the Caribbean countries include fibers (49%), fragments (29%), pellets (17%), and films (5%). Fragments, which are irregular-shaped particles, are typically derived from the breakdown of larger plastic items; fibers are released mainly from synthetic textiles and fishing gear; films and foams also appeared in minor proportions and are frequently associated with packaging and containers. Camargo et al. (2022) have shown sediment MP concentrations averaged at 576.8 ± 577.8 items/m2, with fragments and fibers being the most dominant forms. The fragments typically originated from larger consumer plastics degraded by environmental factors, whereas fibers predominantly originated from synthetic clothing and urban runoff.

According to Kabir et al. (2023), more than 28 kinds of polymers were identified in the leachates of different landfills. Among all types of polymers, studies indicate that LDPE, HDPE, PS, PP, PVC, and PET are the most abundant plastic polymers in landfill leachate worldwide (Table 2). Due to their unique properties and cost-effectiveness, the polymers mentioned above are extensively used for various short-term-use products such as shopping bags (PE), water bottles (PET), and disposable drinking cups (PS), among others. Due to its high flexibility, PVC is widely used in different sectors such as construction, waterproofing, medical equipment, clothing, toys, and other sports supplies (Allsopp and Vianello, 2000; Thornton, 2002).

Table 2. Range, size variation, polymers, detection methods, and forms of microplastics (MPs) detected across the globe.

Geyer et al. (2017) reported that global production of PP and PE accounts for 15% and 25% of the entire plastic production, respectively. It may be another reason for such a high concentration of PP and PE polymers in landfill leachate. PE polymers are also used to control seepage in landfills, and the release of PE polymer from the seepage control films also contributes to the high concentration of PE in the leachate (Sun et al., 2021).

The major polymers were PP, PA, and rayon and constituted 40%, 36%, and 18% fractions of total MPs, respectively (Xu E. G. et al., 2020). In a study in the Guangdong province of China, Wan et al. (2022) also reported PE and PP as the major polymer types in the leachate.

3 Microplastics as vectors in landfills

Ongoing research being conducted across varying regions has unveiled that the presence of MPs in landfill leachate results in irregular shapes and an uneven surface texture, caused by the breakdown of plastic materials within the landfill setting (Sun et al., 2021; Narevski et al., 2021). This surface texture plays a vital role in determining the potential environmental risks. The coarse texture has the potential to increase the absorption of hazardous substances, such as heavy metals and organic pollutants, thereby escalating the environmental hazards associated with leachate disposal (Figure 4). Moreover, the surface roughness also affects the rate of removal through different treatment processes. For instance, in the case of smooth textures, fibers and pellets were comparatively less likely to be trapped by mechanical methods (Long et al., 2019).

Due to the large specific surface area, MPs readily adsorb other pollutants, such as heavy metals, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, antibiotics, and other POPs (Figure 4). Therefore, MPs act as carriers of these pollutants and then alter their environmental transportation patterns and effects (Su et al., 2021). Liu X. et al. (2019) found that MPs served as both a sink and a source of bisphenol A, and the sorption/desorption behaviors were determined by MP surface properties and water chemistry conditions.

MPs potentially carried by leachate may act as vectors of other contaminants and exacerbate the adverse effects on surrounding environments with leachate discharge. MPs have the potential to adsorb persistent organic contaminants and heavy metals and then transport these contaminants or enrich them in biota, thus causing major impacts on human health and ecosystems (Su et al., 2019). Leachate contained abundant pollutants, including heavy metals, persistent organic contaminants, and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) (Shi et al., 2021). The chemical substances contained in MPs can be released and cause harm to organisms (Natesan et al., 2021). MPs can colonize microorganisms on their surface (plastisphere). This small ecosystem serves as a vector for pathogens and possesses a different microbial consortium or structure compared to its surroundings (Qian et al., 2022). Literature also highlighted that MPs could enhance the spread of pathogen ARGs (Liu et al., 2021).

4 Occurrence patterns of microplastics across different landfill ages

The landfill is a vital repository for plastic waste, with the norm being an anaerobic environment that aids in the degradation of MPs (Mahon et al., 2017). As such, assessing the possibility of degradation of MPs in the constantly changing conditions of the long-term landfill process is crucial for the effective control of MP pollution. The assessment of whether MPs degradation occurs in the long-term landfill process with dynamic conditions holds immense importance for controlling MP pollution. On a larger scale, landfills are containers that remain stationary and relatively mild, yet they have a complex and intense reaction to plastics. During the initial stage, plastic polymers maintain their stability, making it challenging for MPs to form. However, various environmental factors, such as aerobic or anaerobic oxidation, leachate erosion, physical pressure, high temperatures, and microbial activities, directly or indirectly deteriorate the physicochemical structure of plastic polymers and promote the fragility of macroplastics (Hao et al., 2017; Kjeldsen et al., 2002; Mahon et al., 2017). The long-term stabilization processes in landfills render plastic waste more delicate and susceptible to disintegration, leading to a significant rise in the production of MPs (Huang et al., 2022).

The presence of MPs in landfills was predominantly influenced by the rise in plastic waste volume, longevity of plastic goods, and degradation of polymers. In young and medium landfills, the average number of MPs detected was eight and 10 items per liter, respectively. However, a lower concentration of four items per liter was found in leachate from an old landfill (Su et al., 2019). In their publication, Zhou et al. (2014) revealed that plastic waste accounted for 2.95%–21.76% of solid waste in landfills, with a higher percentage in near-term landfills than in long-term ones.

In realistic environments, MPs would have a prolonged lifespan and naturally undergo the effects of aging and weathering. Additionally, external forces such as solar radiation, wind, and waves can alter their physicochemical properties. UV and advanced oxidation treatment also impact the surface charge and hydrophobicity of MPs, increasing their ability to mobilize contaminants (Liu J. et al., 2019). Furthermore, exposure to light causes environmentally persistent free radicals to form on the surface of MPs, expediting changes in their surface properties (Zhu et al., 2019).

The natural progression of aging of landfills has been observed to lead to enhanced specific surface area, rough surface morphology, and the development of hydrophilic groups. These alterations significantly impact the environmental behavior of MPs and alter their interactions with other contaminants, such as bisphenol A and polychlorinated biphenyl (Liu J. et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018).

Leachate from old landfills contained fewer cellophane MPs than that from younger and medium landfills. In old landfills, MP polymers such as PP, PE, and PET were either less abundant or undetectable in old landfills. The overall distribution of MPs by size was not influenced by landfill age. However, cellophane MPs in class C (1 mm–5 mm) did show a decrease in their average size as the landfill age increased. Landfill age had a significant impact on the occurrence of MPs in refuse compared to that in leachate. Young and medium landfills had higher levels of MPs, and the variety of polymer types also decreased as the landfill age increased. These results can be attributed to two possible reasons: 1) the increased production and usage of plastics and 2) the potential fragmentation or degradation process of MPs in landfills. This suggests that the increased disposal of plastic waste may be responsible for the elevated levels of MPs in short-term landfills, whereas the usage and lifetimes of plastic products determine the occurrence patterns of individual MPs in landfills of varying ages. The dominant shape and polymer type of MPs detected in leachate were fibers and cellophane, respectively. Meanwhile, fragments and PE became the dominant shape and polymer type in refuse (Su et al., 2019).

Unlike PE and PP, PEUR was more abundant in younger landfills than in the older ones. In contrast, PEUR was undetected in samples from older landfill leachate. This finding might be attributed to the change in application fields and the lifetime of various plastic products. Due to good mechanical and fiber-producing ability, the use of PEUR is increasing every year. PEUR is primarily used in the transportation and construction sector and has a longer lifespan (up to 35 years) than traditional packaging polymers such as PE and PET (0.5 years) (Geyer et al., 2017).

5 Environmental risks of MPs in landfill

Notably, a substantial amount of MPs have accumulated in landfills and have subsequently found their way into the surrounding environment through wind, surface runoff, leachate, and landfill mining (Canopoli et al., 2018; Yadav et al., 2020), and their leakage has been found in the nearby environments of landfills, according to studies conducted by Natesan et al. (2021) and Kazour et al. (2019).

With the added quality of hydrophilicity, MPs have the capacity to adsorb contaminants and redistribute hazardous substances into the environment, as evidenced by research conducted by Wang et al. (2018).

The inadvertent ingestion of MPs may result in physical harm to both animals and humans (Chu et al., 2021; Xu Z. et al., 2020). With the detrimental impact of MPs continually increasing, the burden on the environment appears inevitable. The exponential growth of MPs will only add to this burden in the years to come. Whether through excavation and screening or the dispersal of fine particles through soil application, the release of MPs into the environment from deposited materials in landfills is a real concern (Huang et al., 2022).

Due to their high absorption capability, MPs not only infiltrate the soil but also assimilate organic pollutants (Beckingham and Ghosh, 2017). Furthermore, they possess the ability to act as a catalyst for increasing the bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil (Hodson et al., 2017). As a result, these concentrated MPs in the soil can be absorbed by soil organisms. The unique physical and chemical properties of MPs make them more detrimental to the environment than larger plastic waste (Leed and Smithson, 2019). In turn, this can lead to modifications in the physical and chemical properties of the soil, negatively impacting the biodiversity and integral soil processes, including the breakdown of organic matter (Rillig et al., 2017). A recent analysis conducted by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature and the University of Newcastle revealed that on an average, an individual consumes approximately 5 g of plastic per week via food and water consumption. However, depending on one’s dietary habits, this figure can reach a staggering 1,769 particles from drinking water, 182 from crustaceans, 10 from beer, and 11 from salt (WWF, 2019). Such findings shed light on the severity of MP intake and its potential impact on human health.

One of the major origins of MP contamination stems from the abrasion of tires as they are abundant compared to other plastic particle types. Breaking down these plastic particles leads to the formation of fibers and fragments. These primary MPs can significantly impact terrestrial ecosystems by permeating the environment (Ng et al., 2018). The presence of MPs can greatly affect soil properties and, consequently, the performance of plants. The transfer of landfill soils into agricultural land further exacerbates the issue. Thus, it is no surprise that there is a notable presence of MPs in soils that can detrimentally affect plant growth and various soil functions (Afrin et al., 2020). Furthermore, a study conducted in Mauritius revealed the presence of 230 kg of MPs per hectare in agricultural soils near a landfill, with 96% of these pollutants being found in the deeper layers of soil (Ragoobur et al., 2021). These findings serve as evidence of the involvement of land-based activities, such as agriculture (involving the use of plastics in mulching, equipment packaging, and greenhouses) and landfills (used for disposal purposes), in the release of MPs on African landscapes (Deme et al., 2022).

6 Toxicity of MPs to ecosystems, animals, and humans

The presence of MPs has been observed worldwide, spanning a wide range of environments from freshwater to seawater, urban to remote areas, and sandy shores to deep-sea sediment (Hirai et al., 2011; Claessens et al., 2011). With growing concerns about the negative effects of MPs on aquatic organisms, many research workers have studied their detrimental impacts. For instance, aquatic animals have been found to suffer from starvation as a result of ingesting MPs (Cole et al., 2011). Plastic particles have also been reported in the stomachs of seabirds such as fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis) and flesh-footed shearwaters (Ardenna carneipes) (Charlton-Howard et al., 2023; Van Franeker and Law, 2015). Charlton-Howard et al. (2023) reported the sublethal “hidden” impacts of plastic ingestion by the flesh-footed shearwaters (Ardenna carneipes). For the first time, “plasticosis,” which is a fibrotic disease developed in response to plastic exposure, was found in seabird stomach tissue. According to research by Richard et al. (2021), the consumption of plastic affects the mortality rate of birds, such as condors and vultures. This is due to the indiscriminate ingestion of these anthropogenic materials.

Additionally, studies have shown evidence of transfer of MPs to various trophic levels (Farrell and Nelson, 2013), making it a potential path for ingestion in the species (Santana et al., 2017). Furthermore, MPs have been found to release toxic compounds such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), and these MPs can also accumulate pharmaceuticals, POPs, antibiotics, and heavy metals such as copper (Cu), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), Cr, nickel (Ni), and mercury (Hg) (Fu et al., 2021; Wang H. et al., 2021) due to their high surface area and hydrophobicity, making them more susceptible to adsorption.

The adverse health impacts of MPs on aquatic organisms have also been well documented. Literature has shown that the accumulation of MPs can lead to growth retardation, neurotoxicity, genotoxicity, and metabolic disorders in aquatic organisms (Hou et al., 2021; Brun et al., 2019; Eltemsah and Bøhn, 2019). Additionally, MPs have been found to promote the spread of pathogens and ARGs. The profiles of ARGs have been shown to be greatly influenced by the community structure, with exposure to PVC and MPs resulting in bacterial enrichment and transmission of ARGs. Furthermore, microorganisms have been found to trigger a greater frequency of horizontal gene transfer in the plastisphere, making the impact of MPs on aquatic environments and organisms even more concerning (Dehal et al., 2024).

The potential health repercussions posed by MPs to humans are substantial, whether through direct contact or ingestion of contaminated food and water (Figure 5). One of the major concerns is the presence of toxic chemicals such as POPs and heavy metals in MPs, which have the ability to accumulate in human tissues and lead to chronic diseases such as cancer, neurological disorders, and hormonal imbalances. Moreover, MPs have been linked to immune system dysfunction and endocrine disruption, resulting in an array of health issues, including autoimmune diseases, allergies, reproductive problems, and developmental toxicity. The toxicity of MPs has been documented in various studies by Kutralam-Muniasamy et al. (2023), Kumar et al. (2024), Sangkham et al. (2022), and Rana and Nautiyal, (2023). Furthermore, there is evidence that the transfer of MPs through the food chain and food web is detrimental to human health, as observed in studies by Pironti et al. (2021). MPs from commonly consumed items, such as drinking water, table salt, and food, can be ingested and absorbed in small organs/lipids, leading to toxicity, as demonstrated by Zhang et al. (2020). In a comprehensive review, Sangkham et al. (2022) examined the cytotoxic, neurotoxic, reproductive, immunotoxic, DNA-damaging, oxidative stress, and other severe effects of MPs and NPs on animals and humans.

7 Conclusion

The absence of efficient plastic waste management systems remains a primary driver of the adverse environmental consequences associated with plastic pollution. Current research addressing the environmental behavior of MPs in landfills and leachate is still in its nascent stages, thereby limiting our ability to develop effective mitigation strategies due to insufficient knowledge. To comprehensively assess the risks posed by MPs, it is crucial to investigate their potential role as vectors of pollutants and pathogens, which may amplify their ecological and human health impacts. Expanding research in these emerging areas is, therefore, essential. Significant reductions in MP-related problems can be achieved through advancements in WWTPs and landfill leachate treatment systems, enabling more efficient removal of MPs along with the associated pollutants and pathogens. Moreover, mitigating MP pollution requires the stringent enforcement of regulatory policies, continuous monitoring, and the adoption of innovative cleanup technologies. The integration of sustainable waste management strategies, prioritizing source reduction, reusing, recycling, and waste-to-energy conversion, can minimize plastic inputs into landfills, which should remain the least preferable disposal option. Finally, there is an urgent need to promote the development and adoption of eco-friendly materials, sustainable packaging solutions, and technologies such as microfiber filtration, which collectively offer promising avenues for addressing the growing challenge of MP pollution.

Public awareness campaigns encouraging behavioral change, particularly the avoidance of single-use plastics (SUPs), are also critical. In this regard, interventions from governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including stringent policies such as bans on SUPs and nonbiodegradable plastic bags, along with the implementation of extended producer responsibility (EPR), can play a transformative role. Adopting a circular economy (CE) framework offers a sustainable pathway for plastic waste management by fostering recycling, reusing, and responsible product design, thereby reducing both environmental impacts and resource consumption. Additionally, novel approaches such as landfill mining, including the recovery of plastic fractions from abandoned industrial sites, could provide viable solutions for addressing MP pollution originating from legacy plastic waste in landfills.

Author contributions

AG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. RA: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afrin, S., Uddin, M. K., and Rahman, M. M. (2020). Microplastics contamination in the soil from urban landfill site, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Heliyon 6 (11), e05572. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05572

Allsopp, M. W., and Vianello, G. (2000). Poly (vinyl chloride). Ullmann’s Encycl. industrial Chem. 10 (1435600). a21–a717. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_717

Anderson, P. J., Warrack, S., Langen, V., Challis, J. K., Hanson, M. L., and Rennie, M. D. (2017). Microplastic contamination in lake Winnipeg, Canada. Environ. Pollut. 225, 223–231. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.072

Arthur, C., Baker, J. E., and Bamford, H. A. (2009). Proceedings of the international research workshop on the occurrence, effects, and fate of microplastic marine debris, September 9-11, 2008. USA: university of Washington tacoma, tacoma, wa.

Beckingham, B., and Ghosh, U. J. E. P. (2017). Differential bioavailability of polychlorinated biphenyls associated with environmental particles: microplastic in comparison to wood, coal and biochar. Environ. Pollut. 220, 150–158. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.033

Blair, R. M., Waldron, S., and Gauchotte-Lindsay, C. (2019). Average daily flow of microplastics through a tertiary wastewater treatment plant over a ten-month period. Water Res. 163, 114909. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2019.114909

Bouwmeester, H., Hollman, P. C., and Peters, R. J. (2015). Potential health impact of environmentally released micro-and nanoplastics in the human food production chain: experiences from nanotoxicology. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 49 (15), 8932–8947. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b01090

Browne, M. A., Crump, P., Niven, S. J., Teuten, E., Tonkin, A., Galloway, T., et al. (2011). Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines woldwide: sources and sinks. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 45 (21), 9175–9179. doi:10.1021/es201811s

Brun, N. R., Van Hage, P., Hunting, E. R., Haramis, A. P. G., Vink, S. C., Vijver, M. G., et al. (2019). Polystyrene nanoplastics disrupt glucose metabolism and cortisol levels with a possible link to behavioural changes in larval zebrafish. Commun. Biol. 2 (1), 382. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0629-6

Camargo, A. L. G., Girard, P., Sanz-Lazaro, C., Silva, A. C. M., De Faria, É., Figueiredo, B. R. S., et al. (2022). Microplastics in sediments of the pantanal wetlands, Brazil. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1017480. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.1017480

Canopoli, L., Fidalgo, B., Coulon, F., and Wagland, S. T. (2018). Physico-chemical properties of excavated plastic from landfill mining and current recycling routes. Waste Manag. 76, 55–67. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2018.03.043

Chamas, A., Moon, H., Zheng, J., Qiu, Y., Tabassum, T., Jang, J. H., et al. (2020). Degradation rates of plastics in the environment. ACS Sustain. Chem. and Eng. 8 (9), 3494–3511. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b06635

Charlton-Howard, H. S., Bond, A. L., Rivers-Auty, J., and Lavers, J. L. (2023). Plasticosis’: characterising macro-and microplastic-associated fibrosis in seabird tissues. J. Hazard. Mater. 450, 131090. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131090

Cheng, Y. L., Kim, J. G., Kim, H. B., Choi, J. H., Tsang, Y. F., and Baek, K. (2021). Occurrence and removal of microplastics in wastewater treatment plants and drinking water purification facilities: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 410, 128381. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.128381

Chu, J., Liu, H., and Salvo, A. (2021). Air pollution as a determinant of food delivery and related plastic waste. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 (2), 212–220. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-00961-1

Claessens, M., De Meester, S., Van Landuyt, L., De Clerck, K., and Janssen, C. R. (2011). Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in marine sediments along the Belgian coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62 (10), 2199–2204. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.06.030

Cole, M., Lindeque, P., Halsband, C., and Galloway, T. S. (2011). Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: a review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62 (12), 2588–2597. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.09.025

Czanderna, A. W., and Pern, F. J. (1996). Encapsulation of PV modules using ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer as a pottant: a critical review. Sol. energy Mater. Sol. cells 43 (2), 101–181. doi:10.1016/0927-0248(95)00150-6

Dehal, A., Prajapati, A., P. Patil, M., and Kumar, A. R. (2024). A review on microplastics in landfill leachate: formation, occurrence, detection, and removal techniques. Chem. Ecol. 40 (1), 65–101. doi:10.1080/02757540.2023.2290183

Deme, G. G., Ewusi-Mensah, D., Olagbaju, O. A., Okeke, E. S., Okoye, C. O., Odii, E. C., et al. (2022). Macro problems from microplastics: toward a sustainable policy framework for managing microplastic waste in Africa. Sci. total Environ. 804, 150170. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150170

Dokl, M., Copot, A., Krajnc, D., Van Fan, Y., Vujanović, A., Aviso, K. B., et al. (2024). Global projections of plastic use, end-of-life fate and potential changes in consumption, reduction, recycling and replacement with bioplastics to 2050. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 51, 498–518. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2024.09.025

Eltemsah, Y. S., and Bøhn, T. (2019). Acute and chronic effects of polystyrene microplastics on juvenile and adult Daphnia magna. Environ. Pollut. 254, 112919. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.07.087

Enfrin, M., Lee, J., Le-Clech, P., and Dumee, L. F. (2020). Kinetic and mechanistic aspects of ultrafiltration membrane fouling by nano-and microplastics. J. Membr. Sci. 601, 117890. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2020.117890

Eriksen, M., Lebreton, L. C., Carson, H. S., Thiel, M., Moore, C. J., Borerro, J. C., et al. (2014). Plastic pollution in the world's oceans: more than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PloS one 9 (12), e111913. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111913

Esiukova, E. (2017). Plastic pollution on the Baltic beaches of Kaliningrad region, Russia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 114 (2), 1072–1080. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.10.001

Farrell, P., and Nelson, K. (2013). Trophic level transfer of microplastic: mytilus edulis (L.) to carcinus maenas (L.). Environ. Pollut. 177, 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2013.01.046

Ferguson, L., Awe, A., and Sparks, C. (2024). Microplastic concentrations and risk assessment in water, sediment and invertebrates from Simon's town, South Africa. Heliyon 10 (7), e28514. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28514

Fernandes, A. N., Bertoldi, C., Lara, L. Z., Stival, J., Alves, N. M., Cabrera, P. M., et al. (2022). Microplastics in Latin America ecosystems: a critical review of the current stage and research needs. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 33, 303–326. doi:10.21577/0103-5053.20220018

Fu, L., Li, J., Wang, G., Luan, Y., and Dai, W. (2021). Adsorption behavior of organic pollutants on microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 217, 112207. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112207

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., and Law, K. L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3 (7), e1700782. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782

Ghosh, P., Thakur, I. S., and Kaushik, A. (2017). Bioassays for toxicological risk assessment of landfill leachate: a review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 141, 259–270. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.03.023

Gijsman, P., and Sampers, J. (1997). The influence of oxygen pressure and temperature on the UV-degradation chemistry of polyethylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 58 (1-2), 55–59. doi:10.1016/s0141-3910(97)00012-8

Guerranti, C., Cannas, S., Scopetani, C., Fastelli, P., Cincinelli, A., and Renzi, M. (2017). Plastic litter in aquatic environments of maremma regional park (tyrrhenian sea, Italy): contribution by the ombrone river and levels in marine sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 117 (1-2), 366–370. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.02.021

Gupta, A., Gaharwar, U. S., Verma, A., and Rajamani, P. (2022). Municipal solid waste landfill leachate induced cytotoxicity in root tips of vicia faba: environmental risk posed by non-engineered landfill. Indian J. Biochem. Biophysics (IJBB) 59 (11), 1113–1125. doi:10.56042/ijbb.v59i11.66982

Gupta, A., Verma, A., and Rajamani, P. (2024a). Impact of landfill leachate on ground water quality: a review of landfill leachate: characterization leachate environment impacts and sustainable treatment methods.93–107.

Gupta, A., Verma, A., and Rajamani, P. (2024b). Municipal solid waste landfill leachate treatment: a review. Landfill Leachate Treat. Tech., 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-63157-3_1

Hao, Z., Sun, M., Ducoste, J. J., Benson, C. H., Luettich, S., Castaldi, M. J., et al. (2017). Heat generation and accumulation in municipal solid waste landfills. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 51 (21), 12434–12442. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b01844

He, P., Chen, L., Shao, L., Zhang, H., and Lü, F. (2019). Municipal solid waste (MSW) landfill: a source of microplastics? evidence of microplastics in landfill leachate. Water Res. 159, 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2019.04.060

He, Z. W., Yang, W. J., Ren, Y. X., Jin, H. Y., Tang, C. C., Liu, W. Z., et al. (2021). Occurrence, effect, and fate of residual microplastics in anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge: a state-of-the-art review. Bioresour. Technol. 331, 125035. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125035

Hirai, H., Takada, H., Ogata, Y., Yamashita, R., Mizukawa, K., Saha, M., et al. (2011). Organic micropollutants in marine plastics debris from the open ocean and remote and urban beaches. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62 (8), 1683–1692. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.06.004

Hodson, M. E., Duffus-Hodson, C. A., Clark, A., Prendergast-Miller, M. T., and Thorpe, K. L. (2017). Plastic bag derived-microplastics as a vector for metal exposure in terrestrial invertebrates. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 51 (8), 4714–4721. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b00635

Hopewell, J., Dvorak, R., and Kosior, E. (2009). Plastics recycling: challenges and opportunities. Philosophical Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 364 (1526), 2115–2126. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0311

Horton, A. A., Walton, A., Spurgeon, D. J., Lahive, E., and Svendsen, C. (2017). Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. total Environ. 586, 127–141. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.190

Hou, L., Kumar, D., Yoo, C. G., Gitsov, I., and Majumder, E. L. W. (2021). Conversion and removal strategies for microplastics in wastewater treatment plants and landfills. Chem. Eng. J. 406, 126715. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126715

Hu, L., Chernick, M., Hinton, D. E., and Shi, H. (2018). Microplastics in small waterbodies and tadpoles from yangtze river Delta, China. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 52 (15), 8885–8893. doi:10.1021/acs.est.8b02279

Huang, Q., Cheng, Z., Yang, C., Wang, H., Zhu, N., Cao, X., et al. (2022). Booming microplastics generation in landfill: an exponential evolution process under temporal pattern. Water Res. 223, 119035. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2022.119035

Imhof, H. K., Ivleva, N. P., Schmid, J., Niessner, R., and Laforsch, C. (2013). Contamination of beach sediments of a subalpine lake with microplastic particles. Curr. Biol. 23 (19), R867–R868. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.001

Jiang, H., Luo, D., Wang, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, H., and Wang, C. (2023). A review of disposable facemasks during the COVID-19 pandemic: a focus on microplastics release. Chemosphere 312, 137178. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137178

Kabir, M. S., Wang, H., Luster-Teasley, S., Zhang, L., and Zhao, R. (2023). Microplastics in landfill leachate: sources, detection, occurrence, and removal. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 16, 100256. doi:10.1016/j.ese.2023.100256

Kazour, M., Terki, S., Rabhi, K., Jemaa, S., Khalaf, G., and Amara, R. (2019). Sources of microplastics pollution in the marine environment: importance of wastewater treatment plant and coastal landfill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 146, 608–618. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.06.066

Kilponen, J. (2016). Microplastics and harmful substances in urban runoffs and landfill leachates: possible emission sources to marine environment.

Kjeldsen, P., Barlaz, M. A., Rooker, A. P., Baun, A., Ledin, A., and Christensen, T. H. (2002). Present and long-term composition of MSW landfill leachate: a review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32 (4), 297–336. doi:10.1080/10643380290813462

Klein, S., Worch, E., and Knepper, T. P. (2015). Occurrence and spatial distribution of microplastics in river shore sediments of the rhine-main area in Germany. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 49 (10), 6070–6076. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b00492

Kumar, A., Shabnam, A. A., and Khan, S. A. (2024). Accounting on silk for reducing microplastic pollution from textile sector: a viewpoint. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31 (27), 38751–38755. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-23170-x

Kutralam-Muniasamy, G., Shruti, V. C., Pérez-Guevara, F., and Roy, P. D. (2023). Microplastic diagnostics in humans:“The 3Ps” progress, problems, and prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 856, 159164. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159164

Lechner, A., and Ramler, D. (2015). The discharge of certain amounts of industrial microplastic from a production plant into the river danube is permitted by the Austrian legislation. Environ. Pollut. 200, 159–160. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.02.019

Leed, R., and Smithson, M. (2019). Ecological effects of soil microplastic pollution. Leed, Rogers and Smithson, Moore,'Ecological Eff. Soil Microplastic Pollution', Sci. Insights 30, 70–84. doi:10.15354/si.19.re102

Li, J., Liu, H., and Chen, J. P. (2018). Microplastics in freshwater systems: a review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 137, 362–374. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2017.12.056

Li, P., Wang, X., Su, M., Zou, X., Duan, L., and Zhang, H. (2021). Characteristics of plastic pollution in the environment: a review. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 107 (4), 577–584. doi:10.1007/s00128-020-02820-1

Liu, Y., Liu, W., Yang, X., Wang, J., Lin, H., and Yang, Y. (2021). Microplastics are a hotspot for antibiotic resistance genes: progress and perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 773, 145643. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145643

Liu, J., Zhang, T., Tian, L., Liu, X., Qi, Z., Ma, Y., et al. (2019). Aging significantly affects mobility and contaminant-mobilizing ability of nanoplastics in saturated loamy sand. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 53 (10), 5805–5815. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b00787

Liu, P., Qian, L., Wang, H., Zhan, X., Lu, K., Gu, C., et al. (2019). New insights into the aging behavior of microplastics accelerated by advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 53 (7), 3579–3588. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b00493

Liu, X., Shi, H., Xie, B., Dionysiou, D. D., and Zhao, Y. (2019). Microplastics as both a sink and a source of bisphenol A in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 53 (17), 10188–10196. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b02834

Long, Z., Pan, Z., Wang, W., Ren, J., Yu, X., Lin, L., et al. (2019). Microplastic abundance, characteristics, and removal in wastewater treatment plants in a coastal city of China. Water Res. 155, 255–265. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2019.02.028

Mahon, A. M., O’Connell, B., Healy, M. G., O’Connor, I., Officer, R., Nash, R., et al. (2017). Microplastics in sewage sludge: effects of treatment. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 51 (2), 810–818. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b04048

Miller, M. E., Kroon, F. J., and Motti, C. A. (2017). Recovering microplastics from marine samples: a review of current practices. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 123 (1-2), 6–18. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.08.058

Mohammadi, A., Dobaradaran, S., Schmidt, T. C., Malakootian, M., and Spitz, J. (2022). Emerging contaminants migration from pipes used in drinking water distribution systems: a review of the scientific literature. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (50), 75134–75160. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-23085-7

Murphy, F., Ewins, C., Carbonnier, F., and Quinn, B. (2016). Wastewater treatment works (WwTW) as a source of microplastics in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 50 (11), 5800–5808. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b05416

Narevski, A. C., Novaković, M. I., Petrović, M. Z., Mihajlović, I. J., Maoduš, N. B., and Vujić, G. V. (2021). Occurrence of bisphenol A and microplastics in landfill leachate: lessons from south east Europe. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28 (31), 42196–42203. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13705-z

Natesan, U., Vaikunth, R., Kumar, P., Ruthra, R., Srinivasalu, S., and S, S. (2021). Spatial distribution of microplastic concentration around landfill sites and its potential risk on groundwater. Chemosphere 277, 130263. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130263

Nayahi, N. T., Ou, B., Liu, Y., and Janjaroen, D. (2022). Municipal solid waste sanitary and open landfills: contrasting sources of microplastics and its fate in their respective treatment systems. J. Clean. Prod. 380, 135095. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135095

Ng, E. L., Lwanga, E. H., Eldridge, S. M., Johnston, P., Hu, H. W., Geissen, V., et al. (2018). An overview of microplastic and nanoplastic pollution in agroecosystems. Sci. total Environ. 627, 1377–1388. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.341

Nizzetto, L., Futter, M., and Langaas, S. (2016). Are agricultural soils dumps for microplastics of urban origin? Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 10777–10779. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b04140

Oni, B. A., Ayeni, A. O., Agboola, O., Oguntade, T., and Obanla, O. (2020). Comparing microplastics contaminants in (dry and raining) seasons for Ox-Bow Lake in yenagoa, Nigeria. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 198, 110656. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110656

Orona-Návar, C., García-Morales, R., Loge, F. J., Mahlknecht, J., Aguilar-Hernández, I., and Ornelas-Soto, N. (2022). Microplastics in Latin America and the Caribbean: a review on current status and perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 309, 114698. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114698

Parvin, F., Jannat, S., and Tareq, S. M. (2021). Abundance, characteristics and variation of microplastics in different freshwater fish species from Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 784, 147137. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147137

Piccardo, M., Renzi, M., and Terlizzi, A. (2020). Nanoplastics in the oceans: theory, experimental evidence and real world. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 157, 111317. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111317

Pironti, C., Ricciardi, M., Motta, O., Miele, Y., Proto, A., and Montano, L. (2021). Microplastics in the environment: intake through the food web, human exposure and toxicological effects. Toxics 9 (9), 224. doi:10.3390/toxics9090224

Praagh, M. V., Hartman, C., and Brandmyr, E. (2018). Microplastics in landfill leachates in the nordic countries.

Puthcharoen, A., and Leungprasert, S. (2019). Determination of microplastics in soil and leachate from the landfills. Thai Environ. Eng. J. 33 (3), 39–46.

Qian, P. Y., Cheng, A., Wang, R., and Zhang, R. (2022). Marine biofilms: diversity, interactions and biofouling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20 (11), 671–684. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00744-7

Ragoobur, D., Huerta-Lwanga, E., and Somaroo, G. D. (2021). Microplastics in agricultural soils, wastewater effluents and sewage sludge in Mauritius. Sci. Total Environ. 798, 149326. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149326

Rakesh, S., Davamani, V., Murugaragavan, R., Ramesh, P., and Shrirangasami, S. (2021). Microplastics contamination in the environment. Pharma Innov. J. 10 (8), 1412–1417.

Rana, S. K., and Nautiyal, S. (2023). Current state of plastic use and available alternatives in the himalaya: challenges and way forward. Int. J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 49 (7), 91–103. doi:10.55863/ijees.2023.3001

Richard, E., Zapata, D. I. C., and Angeoletto, F. (2021). Consumo incidental de plástico y otros materiales antropogénicos por parte de Coragyps atratus (Bechstein, 1793) en un vertedero de basura de Ecuador. Peruvian J. Biol. 28 (4), e21627. doi:10.15381/rpb.v28i4.21627

Rillig, M. C., Ingraffia, R., and de Souza Machado, A. A. (2017). Microplastic incorporation into soil in agroecosystems. Front. plant Sci. 8, 1805. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.01805

Roy, P. K., Hakkarainen, M., Varma, I. K., and Albertsson, A. C. (2011). Degradable polyethylene: fantasy or reality. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 45 (10), 4217–4227. doi:10.1021/es104042f

Sangkham, S., Faikhaw, O., Munkong, N., Sakunkoo, P., Arunlertaree, C., Chavali, M., et al. (2022). A review on microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment: their occurrence, exposure routes, toxic studies, and potential effects on human health. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 181, 113832. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113832

Santana, M.F.M., Moreira, F. T., and Turra, A. (2017). Trophic transference of microplastics under a low exposure scenario: insights on the likelihood of particle cascading along marine food-webs. Marine pollution bulletin 121 (1-2), 154–159.

Shen, M., Hu, T., Huang, W., Song, B., Zeng, G., and Zhang, Y. (2021). Removal of microplastics from wastewater with aluminosilicate filter media and their surfactant-modified products: performance, mechanism and utilization. Chem. Eng. J. 421, 129918. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.129918

Shi, J., Wu, D., Su, Y., and Xie, B. (2021). Selective enrichment of antibiotic resistance genes and pathogens on polystyrene microplastics in landfill leachate. Sci. Total Environ. 765, 142775. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142775

Silva, A. L., Prata, J. C., Duarte, A. C., Soares, A. M., Barceló, D., and Rocha-Santos, T. (2021). Microplastics in landfill leachates: the need for reconnaissance studies and remediation technologies. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 3, 100072. doi:10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100072

Singh, S., Malyan, S. K., Maithani, C., Kashyap, S., Tyagi, V. K., Singh, R., et al. (2023). Microplastics in landfill leachate: occurrence, health concerns, and removal strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 342, 118220. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118220

Sogancioglu, M., Yel, E., and Ahmetli, G. (2017). Pyrolysis of waste high density polyethylene (HDPE) and low density polyethylene (LDPE) plastics and production of epoxy composites with their pyrolysis chars. J. Clean. Prod. 165, 369–381. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.157

Song, Y. K., Hong, S. H., Jang, M., Han, G. M., Jung, S. W., and Shim, W. J. (2017). Combined effects of UV exposure duration and mechanical abrasion on microplastic fragmentation by polymer type. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 51 (8), 4368–4376. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b06155

Song, Y. K., Hong, S. H., Eo, S., Jang, M., Han, G. M., Isobe, A., et al. (2018). Horizontal and vertical distribution of microplastics in Korean coastal waters. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 52 (21), 12188–12197. doi:10.1021/acs.est.8b04032

Steinmetz, Z., Wollmann, C., Schaefer, M., Buchmann, C., David, J., Tröger, J., et al. (2016). Plastic mulching in agriculture. Trading short-term agronomic benefits for long-term soil degradation? Sci. total Environ. 550, 690–705. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.153

Su, L., Xue, Y., Li, L., Yang, D., Kolandhasamy, P., Li, D., et al. (2016). Microplastics in taihu lake, China. Environ. Pollut. 216, 711–719. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.06.036

Su, Y., Zhang, Z., Wu, D., Zhan, L., Shi, H., and Xie, B. (2019). Occurrence of microplastics in landfill systems and their fate with landfill age. Water Res. 164, 114968. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2019.114968

Su, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhu, J., Shi, J., Wei, H., Xie, B., et al. (2021). Microplastics act as vectors for antibiotic resistance genes in landfill leachate: the enhanced roles of the long-term aging process. Environ. Pollut. 270, 116278. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116278

Sun, J., Zhu, Z. R., Li, W. H., Yan, X., Wang, L. K., Zhang, L., et al. (2021). Revisiting microplastics in landfill leachate: unnoticed tiny microplastics and their fate in treatment works. Water Res. 190, 116784. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2020.116784

Sundt, P., Schulze, P.-E., and Syversen, F. (2014). Sources of microplastic pollution to the marine environment. Report No: M-321-2015 (Asker: Mepex).

Tanaka, K., and Takada, H. (2016). Microplastic fragments and microbeads in digestive tracts of planktivorous fish from urban coastal waters. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 34351. doi:10.1038/srep34351

Thornton, J. (2002). “Environmental impacts of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) building materials,”. Washington, DC: Healthy Building Network.

UN report (2022). United nations report on world populations prospects. Available online at: https://population.un.org/wpp/.

UNEP, M. P. D., and Lessons, M. G. (2016). Research to inspire action and guide policy change. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, 179.

Van Franeker, J. A., and Law, K. L. (2015). Seabirds, gyres and global trends in plastic pollution. Environ. Pollut. 203, 89–96. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.02.034

Verma, A., Gaharwar, U. S., Priyadarshini, E., and Rajamani, P. (2022a). Metal accumulation and health risk assessment in wastewater used for irrigation around the agra canal in faridabad, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (6), 8623–8637. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16088-3

Verma, A., Gaharwar, U. S., Maurya, A., and Rajamani, P. (2022b). Cytotoxic and genotoxic assessment of wastewater on HEK293 cell line. Indian J. Biochem. Biophysics (IJBB) 59 (5), 558–564. doi:10.56042/ijbb.v59i5.61276

Verma, A., Gupta, A., and Rajamani, P. (2023). “Application of wastewater in agriculture: benefits and detriments,” in River conservation and water resource management (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 53–75.

Vianello, A., Boldrin, A., Guerriero, P., Moschino, V., Rella, R., Sturaro, A., et al. (2013). Microplastic particles in sediments of lagoon of venice, Italy: first observations on occurrence, spatial patterns and identification. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 130, 54–61. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2013.03.022

Wan, Y., Chen, X., Liu, Q., Hu, H., Wu, C., and Xue, Q. (2022). Informal landfill contributes to the pollution of microplastics in the surrounding environment. Environ. Pollut. 293, 118586. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118586

Wang, C., Zhao, J., and Xing, B. (2021). Environmental source, fate, and toxicity of microplastics. J. Hazard. Mater. 407, 124357. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124357

Wang, F., Wong, C. S., Chen, D., Lu, X., Wang, F., and Zeng, E. Y. (2018). Interaction of toxic chemicals with microplastics: a critical review. Water Res. 139, 208–219. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2018.04.003

Wang, L., Wang, H., Huang, Q., Yang, C., Wang, L., Lou, Z., et al. (2023). Microplastics in landfill leachate: a comprehensive review on characteristics, detection, and their fates during advanced oxidation processes. Water 15 (2), 252. doi:10.3390/w15020252

Wang, H., Li, W., Zhu, C., and Tang, X. (2021). Analysis of heavy metal pollution in cultivated land of different quality grades in yangtze river Delta of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (18), 9876. doi:10.3390/ijerph18189876

Westerhoff, P., Prapaipong, P., Shock, E., and Hillaireau, A. (2008). Antimony leaching from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic used for bottled drinking water. Water Res. 42 (3), 551–556. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2007.07.048

WWF (2019). Evaluacion ´ de la ingestion ´ humana de pl´ asticos presentes en la naturaleza. World Wide Fund for Nature,Gland. Available online at: https://wwflac.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/evaluacion_de_la_ingestion_humana_de_plasticos_presentes_en_la_naturaleza_1_1.pdf.

Xu, E. G., Cheong, R. S., Liu, L., Hernandez, L. M., Azimzada, A., Bayen, S., et al. (2020). Primary and secondary plastic particles exhibit limited acute toxicity but chronic effects on Daphnia magna. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 54 (11), 6859–6868. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c00245

Xu, Z., Sui, Q., Li, A., Sun, M., Zhang, L., Lyu, S., et al. (2020). How to detect small microplastics (20–100 μm) in freshwater, municipal wastewaters and landfill leachates? A trial from sampling to identification. Sci. Total Environ. 733, 139218. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139218

Yadav, V., Sherly, M. A., Ranjan, P., Tinoco, R. O., Boldrin, A., Damgaard, A., et al. (2020). Framework for quantifying environmental losses of plastics from landfills. Resour. Conservation Recycl. 161, 104914. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104914

Yang, D., Shi, H., Li, L., Li, J., Jabeen, K., and Kolandhasamy, P. (2015). Microplastic pollution in table salts from China. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 49 (22), 13622–13627. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b03163

Yang, S., Zhou, M., Chen, X., Hu, L., Xu, Y., Fu, W., et al. (2022). A comparative review of microplastics in lake systems from different countries and regions. Chemosphere 286, 131806. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131806

Zhang, Q., Xu, E. G., Li, J., Chen, Q., Ma, L., Zeng, E. Y., et al. (2020). A review of microplastics in table salt, drinking water, and air: direct human exposure. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 54 (7), 3740–3751. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b04535

Zhang, Z., Su, Y., Zhu, J., Shi, J., Huang, H., and Xie, B. (2021). Distribution and removal characteristics of microplastics in different processes of the leachate treatment system. Waste Manag. 120, 240–247. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2020.11.025

Zhou, C., Fang, W., Xu, W., Cao, A., and Wang, R. (2014). Characteristics and the recovery potential of plastic wastes obtained from landfill mining. J. Clean. Prod. 80, 80–86. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.05.083