- 1Faculty of Biology, Plovdiv University, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

- 2Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) initiated an extensive survey of European surface waters and their biological communities. In Bulgaria, aquatic macrophytes were included in the ecological status assessment for the first time in 2009 through the adaptation of the Reference Index, which reflects the influence of multiple stressors. Aquatic bryophytes constitute a significant component of the indicator taxa, with the genus Fontinalis, being the most widespread. Two species of the genus, F. antipyretica and F. hypnoides, have been assigned to different ecological groups: the former to indifferent (group B), and the later to reference indicators (group A). The distribution, abiotic and biotic preferences of these two species were studied in order to refine the macrophyte-based Reference Index and broaden the knowledge on the ecology of the species. Three datasets were used: 421 detailed field survey records conducted between 2009 and 2024, 21 literature sources with 73 records, and 43 herbarium records. Only field survey data were used to compare percent distribution and conduct ecological analyses, as literature and herbarium records are not directly comparable due to differing sampling methods and temporal coverage. Fontinalis antipyretica records appeared to be 11% from the field survey database, while F. hypnoides had distribution at only four river sites (1%). Fontinalis antipyretica exhibits greater ecological amplitude, including tolerance for higher elevations and broader flow conditions. It also exhibits a broader distribution in physico-chemical characteristics of the river water: conductivity (31.3–4,380 μS cm-1) and total nitrogen (TN, 0.07–3.3 mg L-1), consistent with its ecological generalism. Fontinalis hypnoides, although based on fewer samples, displays narrower distributions, particularly in pH and TN (<1 mg L-1) - supporting its sensitivity to physico-chemical parameters. This finding is promising regarding its allocation as an indicator of reference conditions. The overlap in co-existing species indicates a certain degree of ecological similarity between the two Fontinalis species, reflecting their preference for similar aquatic macrophyte assemblage types.

1 Introduction

The Water Framework Directive (Council of the European Communities, 2000) initiated an extensive survey of European surface waters and their biological communities (Birk et al., 2012). In the context of the Water Framework Directive, river types refer to groups of rivers sharing similar hydromorphological and ecological characteristics, while reference conditions describe the state of minimal or no human impact, representing the natural baseline against which ecological status is assessed. As a biological quality element, aquatic macrophytes stand out for their high ability to persist compared to other groups of organisms, which allows for a highly integrative bioindication assessment (Tremp and Kohler, 1995). Accurate evaluation of ecological status can be achieved through proper mapping of macrophyte indicators in running waters.

A new assessment system for macrophytes in German rivers was developed in line with the EU Water Framework Directive, defining river types and reference conditions based on biological, chemical, and hydromorphological data from over 200 sites. Deviation from reference vegetation was used to assess degradation, and new metrics were proposed for classification into five ecological status classes (Schaumburg et al., 2004). This approach was later applied in Bulgaria in 2009 through the adaptation of the Reference Index to the conditions of Bulgarian running waters (Gecheva et al., 2013). In the following years, the biological dataset expanded alongside key abiotic characteristics (flow velocity, substrate type, shading and mean depth, and water chemistry parameters).

Aquatic bryophytes are dominant in the vegetation composition of mountain reference rivers and constitute a significant component of the indicator taxa as their presence in watercourses is negatively affected by reduction in flow velocity, clarity, substratum size, and by the deterioration of chemical status (Ceschin et al., 2012). Several biotic indices are based on the presence and abundance of aquatic macrophytes, including bryophytes: e.g. Mean Trophic Rank (MTR) for assessing the trophic status of rivers (Dawson et al., 1999), IBMR system (L’Indice Biologique Macrophytique en Rivière) for assessing water trophy and organic pollution (Haury et al., 2006), River Macrophyte Nutrient Index (RMNI) along with related metrics like the River Macrophyte Hydraulic Index (RMHI) as part of a multimetric approach (Willby et al., 2012), and Macrophyte Index for Rivers (MIR) developed in Poland (Szoszkiewicz et al., 2019). The majority of bryophytes used in these indices are recognized as good indicators, as they typically exhibit narrow ecological tolerance and a preference for oligotrophic to mesotrophic waters.

Fontinalis Hedw. is the most widespread moss genus in lotic habitats. Members of the genus Fontinalis are obligate aquatic species (Glime, 2017a). These mosses form large pseudocarps with long, sympodially branched stems. Fontinalis spp. are restricted to stable substrates and are negatively affected by periodic and rapid flow fluctuations as well as by overall habitat degradation (Gecheva et al., 2021). In general, upland streams, usually dominated by bryophyte vegetation, are known to lose their rheophilous bryophyte communities when influenced by multiple stressors such as hydromorphological and chemical disturbance. Nutrient pollution can often lead to the disappearance of bryophytes because the stimulated growth of periphyton on their surfaces causes competition for light and CO2 (Glime, 2017b). Elevated nutrient levels, particularly nitrogen, may promote tracheophyte dominance over bryophytes through competitive interactions and can also shift bryophyte community composition. Nevertheless, in the compilation of Ellenberg N values for Central European bryophytes (Simmel et al., 2021), both species are assigned a value of 6, indicating comparatively high nutrient availability in their habitats.

In contrast, inorganic pollutants are commonly monitored using bryophytes due to their high bioaccumulation capacity. Fontinalis antipyretica Hedw. has historically been used to indicate metal deposits and is now among the most widely applied and well-established biomonitors in European freshwaters (Gecheva et al., 2023). Recent studies have also reported the bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Carrieri et al., 2021) and pharmaceuticals (Alaoui et al., 2021) in F. antipyretica.

Two species of this genus have been assigned to different ecological groups within the framework of the Reference Index following the concept of positive, negative and indifferent indicator species. Fontinalis hypnoides C. Hartm. represents reference taxa group, indicating “good” status, while F. antipyretica is among species without preferences for reference or other specific conditions. The main goal of this study was to determine whether the two representatives of the genus should indeed be regarded as belonging to different indicator groups, and, if necessary, to re-evaluate their indicator potential and their assignment to the established groups based on new comprehensive data collected during macrophyte surveys conducted in Bulgaria within the implementation of the Reference Index between 2009 and 2024. For this purpose, hydromorphological (mean width, substrate, flow velocity, shading), physico-chemical (pH, electrical conductivity, total nitrogen, BOD), and biotic (abundance, co-occurring taxa) parameters obtained during the field surveys were analyzed. In addition, existing herbarium and literature records were included to explore the geographical and altitudinal distribution of the genus in Bulgaria.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area and sampling

The majority of literature and herbarium data (Figure 1; Supplementary Material 1,2) come from Western Balkan Mts. (Papp et al., 2006; Ganeva et al., 2008), Rila Mt. (Podpéra, 1911; Ganeva, 1997; Ganeva, 2000; Ganeva and Düll, 1999; Papp et al., 2006), and Vitosha Mt. (Podpéra, 1911; Hájek et al., 2005; Papp et al., 2006). probably because these mountains have always been of bryological interest. Mountain rivers and streams there are important habitats for bryophytes. Additional records have been reported from the Mesta and Maritsa rivers in Southern Bulgaria (Gecheva et al., 2010), and from Strandzha Mt. (Papp et al., 2011) in the SE Bulgaria.

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of sampling localities for Fontinalis species. Legend: red - F. antipyretica, black - F. hypnoides, circle–literature and herbarium data; triangle - detailed field survey records.

The study area covers the entire territory of Bulgaria, with sampling sites selected from the national monitoring network and representing all defined river types. The sites were studied during national monitoring and research projects conducted in Bulgaria between 2009 and 2024.

Aquatic macrophytes were recorded along up to 100 m long section following a zigzag pattern. The nomenclature followed Hill et al. (2006) for mosses, Euro + Med for vascular plants. The species abundance was recorded using a five-level scale (Kohler, 1978): 1 = very rare, 2 = infrequent, 3 = common, 4 = frequent, 5 = abundant, predominant.

Additionally, four abiotic hydromorphological parameters were recorded: flow velocity, shading, substrate type and mean depth. These were determined semi-quantitatively using class scales to allow fast and straightforward field assessment, following Schaumburg et al. (2004). Shading was evaluated on a five-point scale (1 = completely sunny, 2 = sunny, 3 = partly overcast, 4 = half shaded, 5 = completely shaded). Flow velocity was assessed using a six-point scale: I = not visible, II = barely visible, III = slowly running, IV = rapidly running (moderate turbulences), V = rapidly running (turbulently running), VI = torrential. Substrate composition at each sampling site was estimated in 5% increments across a seven-point scale: % mud, % clay/oam, % fine and coarse sand, % gravel, % stones and % boulders. Mean depth was categorized into three classes (I = 0–30 cm, II = 30–100 cm, III >100 cm).

In situ measurements of acidity (pH) and electrical conductivity (EC, µS cm-1) of river water were done using calibrated WTW pH/Conductivity meter. Biochemical oxygen demand and total nitrogen were analyzed following adopted standards (EN 1899-2:2004; EN ISO 11905-1:2001) in accredited laboratories.

2.2 Data collection

Three datasets were used: (i) 421 detailed field survey records which represent available aquatic macrophyte survey records collected during national monitoring and research projects conducted in Bulgaria between 2009 and 2024. Sampling followed the EU standard EN 14184. The geographic coordinates and altitude of each site were recorded on site using a handheld GPS unit. The field protocols included hydromorphological (river mean width, substrate composition, flow velocity, shading), physico-chemical (pH, electrical conductivity, total nitrogen, BOD), and biotic (abundance, co-occurring taxa) parameters of watercourses where Fontinalis species were recorded, which were used in subsequent analyses; (ii) 21 literature sources from the period 1902-2019 – a total of 73 records (Supplementary Material 1); and (iii) 43 herbarium records at SOM from the period 1902-2025 (Supplementary Material 2). Five records that appeared in both the literature and herbarium datasets were excluded from the former. For the latter two datasets, only altitude, longitude, and latitude were extracted, as other information was either missing or provided in non-standard formats. Older records without geographic coordinates but with well described localities were georeferenced using topographic maps and satellite images. The elevation for these records was extracted from a digital elevation model (DEM) at a resolution of 20 m. Although this elevation information is less precise, it was retained in order to ensure that valuable historical data were included.

2.3 Data analysis

Ordination analysis (PCA) in CANOCO 5 (Ter Braak and Smilauer, 2002) was applied to examine linear patterns in accompanying macrophyte species within habitats occupied by F. antipyretica. The analysis was based on presence - absence data for all recorded taxa. Preliminary Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) indicated a negligible gradient length, confirming the appropriateness of a linear ordination method. Environmental variables were included as supplementary variables to aid interpretation of the ordination gradients. The dominant substrate type was coded numerically according to the relative shares of the following categories: mud (1), clay/loam (2), fine sand (3), coarse sand (4), gravel (5), stones (6), and rocks (7). Multiple regression was applied to evaluate the effect of physico-chemical variables on species abundance using Statistica 12 software (StatSoft Inc, 2013). The dataset satisfied the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity. Diagnostic checks and visualizations were performed in Python 3.10 (Python Software Foundation, 2023) using the pandas (McKinney, 2010) and Matplotlib libraries (Hunter, 2007). Maps were created with Esri ArcMap 10.2.2.

3 Results

A total of 116 records of Fontinalis species were compiled from literature sources and herbarium data. F. antipyretica was represented by 68 literature records and 40 herbarium specimens, among them F. antipyretica subsp. gracilis was recorded in 3 literature sources and 4 herbarium specimens. Fontinalis hypnoides was represented by 5 literature records and 3 herbarium specimens (including F. hypnoides var. duriaei). Detailed information on all records and specimens is provided in Supplementary Material 1,2, respectively.

Field surveys documenting Fontinalis species were conducted at 44 sites along 37 rivers in Bulgaria (Supplementary Material 3). Most of the surveyed sites were classified as alpine (n = 5), mountain (n = 27), or semi-mountain (n = 12); the remaining seven sites were lowland rivers, located within Ecoregion 7 (Eastern Balkans) and Ecoregion 12 (Pontic province). The sites were natural with only two designated as highly modified water bodies, and several are considered potentially undisturbed. Fontinalis antipyretica records appeared to be 11% from the field survey database, while F. hypnoides had distribution at only four river sites.

3.1 Abiotic parameters: hydromorphological and physico-chemical

Fontinalis antipyretica is primarily associated with mountain rivers, but it has also been registered in alpine, semi-mountainous, small and medium-sized lowland rivers free from hydromorphological pressure (Figure 1). Thus, it has a broad altitudinal gradient, ranging from the sea level to at least 2,400 m a.s.l., with a median of 794 m. It typically inhabits medium-shaded sites with moderate to fast flow velocity, and prefers coarse substrates. Fontinalis hypnoides had a much narrower altitudinal range in Bulgaria: 17–692 m a.s.l. (median 262 m) and occupied moderately shaded sites with slower current velocity and similar substrate preference.

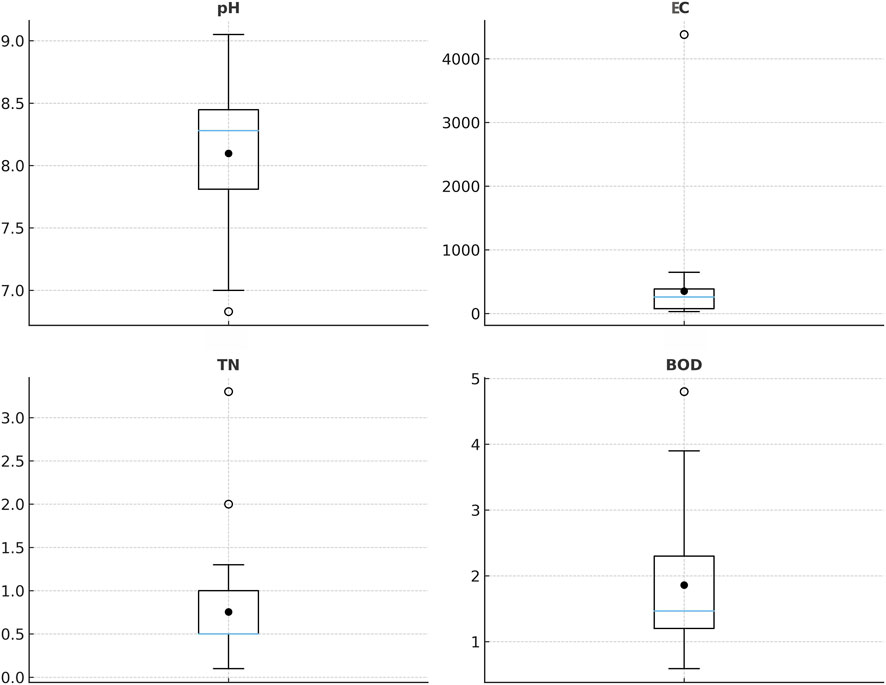

Fontinalis antipyretica also exhibits a broader distribution in physico-chemical characteristics of the river water (Figure 2): pH (6.83–9.05), electrical conductivity (31.3–4,380 μS cm-1), total nitrogen (0.07–3.3 mg L-1) and BOD (0.59–4.8 mg L-1).

Figure 2. Boxplots of pH, conductivity (C µS cm-1), total nitrogen (TN mg L-1), and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD mg L-1) across sites with F. antipyrectica records. (Boxes = interquartile ranges, blue horizontal lines = medians, black circles = means.)

Fontinalis hypnoides was recorded under near-neutral to moderately alkaline conditions (pH 7.57–8.3, median 8.08), with moderately mineralized waters (conductivity 384–459 μS cm-1, median 399), total nitrogen concentrations below 1 mg L-1 (median 0.37 mg L-1), and BOD values between 1.5 and 2.5 mg L-1 (median 1.63 mg L-1).

Fontinalis antipyretica showed weak, statistically non-significant correlations (R2 = 0.064, p = 0.715) with pH (b = −0.08), electrical conductivity (b = 0.092), total nitrogen (b = 0.194), and BOD (b = −0.01), indicating no clear environmental preference. Similarly, F. hypnoides exhibited a negative but non-significant relationship with total nitrogen (R2 = 0.922, b = −0.96, p = 0.131). Although the relationships were not statistically significant, the data suggest that F. antipyretica may tolerate a broad range of environmental conditions, while F. hypnoides tended to decrease in abundance with increasing total nitrogen.

3.2 Biotic parameters

Seventeen accompanying taxa were recorded in aquatic macrophyte assemblages (Table 1). The most frequently co-occurring taxa with F. antipyretica were Platyhypnidium riparioides (28%), Brachythecium rivulare (11%), Myriophyllum spicatum, Potamogeton nodosus, Leptodictyum riparium (8.5% each), Ranunculus trichophyllus and Chara spp. also appeared several times (>4%). For F. hypnoides, fewer records were available, but the same species (P. riparioides, Chara spp., M. spicatum) were noted. In half of the cases, F. antipyretica dominated aquatic macrophyte communities, primarily forming monodominant associations. In several instances, it is the dominant species in communities consisting only of bryophytes (e.g., P. riparioides, B. rivulare), and in two cases, it dominated alongside vascular plants (M. spicatum, P. nodosus).

Table 1. List of recorded accompanying taxa and their abbreviations (Nomenclature after Hill et al., 2006 and EuroMed PlantBase, 2006).

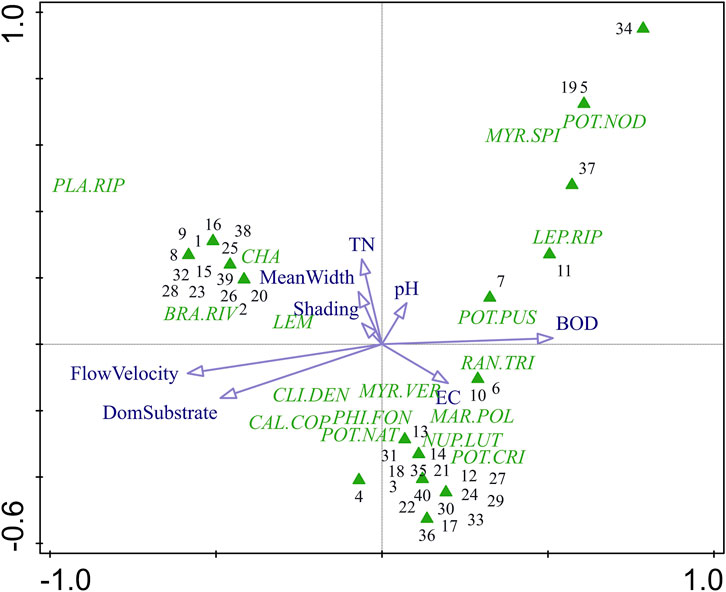

The PCA ordination of macrophyte communities (Figure 3) showed clear separation of sampling sites along the first two axes, which together explained 44.6% of the total variation in species composition (Axis 1: 29.8%, Axis 2: 14.8%). Axis 1 represented a gradient from fast-flowing sites with coarse substrate to slow-flowing, finer-substrate sites associated with higher BOD, pH, and EC values. Axis 2 was mainly related to total nitrogen (TN) and, to a lesser extent, mean river width and shading, distinguishing wider and more nutrient-enriched sites from narrower, less enriched ones. Species such as P. nodosus, M. spicatum and L. riparium were positioned towards the nutrient-rich, slow-flowing end of the gradients, whereas P. riparioides, B. rivulare and Chara spp. were associated with faster current, coarse substrate and nutrient poor conditions.

Figure 3. PCA ordination diagram showing relationships between macrophyte species (green labels), sampling sites (green triangles), and supplementary environmental variables (blue arrows) across sites occupied by F. antipyretica. For abbreviations see Table 1. Numbers correspond to sampling sites as listed in Supplementary Material 3.

4 Discussion

Fontinalis hypnoides is generally much rarer across the studied area–it accounted for about 7% of the literature and herbarium datasets. Its occurrence at only four sites during the field surveys was consistent with its overall scarcity. The reasons for this remained unclear, given that all Fontinalis species benefit from downstream dispersal in running waters through efficient vegetative propagation (Glime, 2020). For example, F. antipyretica is capable of regenerating from nearly any part of the gametophyte and produces gemmae that may form in response to declining water levels (Ares et al., 2014). Our findings for F. hypnoides, which has consistently been observed in a sterile state - while sporophytes have been recorded only twice in F. antipyretica - support this pattern. Another trait reported to give F. antipyretica an advantage that enables it to thrive in contrasting habitats, and which may also apply to F. hypnoides, is its streamer growth form, allowing survival in both relatively fast-flowing and nearly stagnant waters (Glime, 2020). A possible factor limiting the wider distribution of F. hypnoides could be water temperature, as the moss showed reduced vitality at temperatures above 15 °C (Glime, 1982).

The field dataset compiled of the records of the two Fontinalis species from Bulgarian rivers was used to determine whether spatial patterns in their distribution follow their indicator status within the context of the Reference Index. The physico-chemical conditions recorded across sites reflect a broad ecological spectrum of F. antipyretica, from near-pristine to moderately impacted waters. The measured pH values (6.83–9.05) indicate conditions ranging from near neutral to moderately alkaline, which are typical for hardwater streams influenced by carbonate geology. Such conditions are generally favorable for aquatic bryophytes, as most species tolerate neutral to alkaline waters (Kaijser et al., 2022). Median conductivity (258 μS cm-1) indicates that most sites are moderately mineralized, consistent with the prevalence of carbonate geology in the region, whereas the extreme maximum (4,380 μS cm-1) was restricted to a transitional river type. Such variation in ionic strength can directly influence bryophyte distribution, since many aquatic mosses are tolerant of moderate mineralization but are progressively excluded at very high conductivities. Previous research in Croatian watercourses found that the abundance of F. antipyretica increased continuously with conductivity, reaching a maximum at values above 900 μS cm-1, indicating a preference for relatively high conductivity levels (Rimac et al., 2022). Alkaline (8.3–8.6) waters with moderate conductivity (330–440 μS cm-1) were reported to favor the species in mountain streams in Italy (Ceschin et al., 2015).

Total nitrogen concentrations (median 0.5 mg L-1) point to generally oligotrophic to mesotrophic conditions, although the upper range (from 2 to 3.3 mg L-1; Figure 2) suggests local nutrient enrichment that may favor tracheophytes and algae at the expense of bryophytes. Similar nitrogen maximum range between 2 and 3 mg L-1 was recently reported (Rimac et al., 2022). Similarly, BOD values (median 1.5 mg L-1) indicate good oxygen status at most sites, with occasional elevations (>3–4 mg L-1) reflecting moderate organic loading. Overall, F. antipyretica exhibits broad ecological variability, occurring across a wide altitudinal range and along diverse environmental gradients.

At the studied locations, F. hypnoides was consistently associated with near-neutral to moderately alkaline waters of moderate conductivity. The species is neutrophilous to basophilous and is associated with naturally or anthropogenically reduced flows (Vieira et al., 2014). The relatively low nutrient and organic load at studied sites suggest that F. hypnoides may be more restricted to stable, less enriched habitats compared to the broader ecological amplitude observed for F. antipyretica. This confirmed its allocation as an indicator of reference conditions. However, given the small sample size, further records are needed to confirm whether this reflects the species’ true ecological preferences or local habitat availability.

Our observations show that F. antipyretica usually forms monodominant stands; when other macrophytes are present, their number is typically limited to about two accompanying species. This pattern is consistent with previous reports describing monocultures of F. antipyretica or communities dominated by this species with only one or two associates (Lang and Murphy, 2012). The most frequently co-occurring taxon with both Fontinalis species was another obligate-aquatic moss P. riparioides, which is commonly found together with F. antipyretica (Scarlett and O’Hare, 2006; Lang and Murphy, 2012). Among vascular macrophytes, M. spicatum was the most frequently associated species for both mosses. The overlap in co-occurring species suggests a degree of ecological similarity between the two Fontinalis species and the macrophyte communities with which they are associated.

The PCA (Figure 3), which explains 44.6% of the total variation in species composition, indicates that the separation of sites occupied by F. antipyretica is largely associated with hydromorphological and physico-chemical gradients, as shown by the orientation and strength of the environmental vectors. Sites grouped on the left of the diagram (e.g. sampling sites 8, 9, 15, 23, 25, 28, 32, and 38) were characterized by higher flow velocity and coarser substrates, conditions that favored rheophilic taxa such as P. riparioides, B. rivulare, and Chara spp. These macrophyte assemblages indicate oligotrophic environments typical of upper and mid-reach river sections. In contrast, sites positioned on the right and upper parts of the ordination (e.g. 5, 7, 11, 19, 34, and 37) corresponded to slower-flowing, finer-substrate, and more nutrient-enriched habitats with elevated BOD, pH, EC, and TN values. These sites supported species such as P. nodosus, M. spicatum, L. riparium, and P. pusillus, which are typical of lowland, depositional environments. Intermediate sites (e.g. 10, 13, 18, 21, and 30) showed moderate current velocity and conductivity, hosting mixed communities that included R. trichophyllus, P. natans, and Callitriche spp. This pattern suggests a gradual transition from high-energy, coarse-bed habitats to low-energy, macrophyte-dominated reaches. Overall, F. antipyretica tends to coexist with rheophilic and shade-tolerant macrophytes in cooler, fast-flowing sections of rivers, with coarse substrates, typical of mountain and semi-mountain streams. Such river stretches are usually subject to low anthropogenic impact, which correlates with the fact that the species is characteristic of the so-called “moss zone” of shallow mountain brooks with coarse substrate, high flow velocities, and low alkalinity and total phosphorus concentrations (Kaijser et al., 2022). Nevertheless, its occurrence with high abundance also in lowland rivers, within open reaches dominated by vascular macrophytes such as Myriophyllum, highlights the species’ broad ecological tolerance to both abiotic and biotic variability. The PCA results therefore support the classification of F. antipyretica as a representative of indifferent indicator group in Bulgarian rivers. Such broad ecological tolerance regarding the environmental gradients and intermediate behavior was reported from France (Vanderpoorten et al., 1999), Italy (Ceschin et al., 2012) and Croatia (Rimac et al., 2022). Moreover, due to its easy recognition and broad distribution F. antipyretica has been used as a target species in numerous in situ and ex situ biomonitoring studies and its presence in both low- and highly impacted environments is well documented (e.g. Vázquez et al., 2020; Alaoui et al., 2021; Rajala et al., 2025).

Our study confirms that F. antipyretica and F. hypnoides belong to different indicator groups - the former being not closely associated with specific conditions and therefore classified as an indifferent taxon, and the latter as an indicator taxon for “good” ecological status.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

GG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. RN: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AG: Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article is financed by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project BG-RRP-2.004-0001-C01. The field survey database was created with support from the following projects: Development of a classification system for assessment of the ecological status and ecological potential of surface water types in Bulgaria (MoEW, BG); Defining reference conditions and maximum ecological potential for the surface water types in Bulgaria (MoEW, BG); Intercalibration of the methods for analysis of biological quality elements (BQE) for the types of surface waters on the territory of Bulgaria (C-33-27/26.11.2013); Validation of the typology and classification system in Bulgaria for assessment of the ecological status of surface water bodies of categories “river,” “lake,” and “transitional waters (Grant No. 7195735/17.4.2020, DICON-UBA); National Roadmap for Research Infrastructure 2020-2027 (MoES, BG, Agreement No DO1-163/28.07.2022 LTER-BG).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of scientists on aquatic bryophytes, whose efforts made these databases possible. We warmly thank the reviewers of this manuscript, whose insights and suggestions helped us improve it and present it in its current form.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2025.1715526/full#supplementary-material

References

Alaoui, K. S., Tychon, B., Joachim, S., Geffard, A., Nott, K., Ronkart, S., et al. (2021). Toxic effects of a mixture of five pharmaceutical drugs assessed using Fontinalis antipyretica hedw. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 225, 112727. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112727

Ares, A., Duckett, J. G., and Pressel, S. (2014). Asexual reproduction and protonemal development in vitro in Fontinalis antipyretica hedw. J. Bryol. 36, 122–133. doi:10.1179/1743282014y.0000000099

Birk, S., Bonne, W., Borja, A., Brucet, S., Courrat, A., Poikane, S., et al. (2012). Three hundred ways to assess Europe's surface waters: an almost complete overview of biological methods to implement the Water Framework Directive. Ecol. Ind. 18, 31–41. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.10.009

Carrieri, V., Fernández, J. Á., Aboal, J. R., Picariello, E., and De Nicola, F. (2021). Accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the devitalized aquatic moss Fontinalis antipyretica: from laboratory to field conditions. J. Environ. Qual. 50 (5), 1196–1206. doi:10.1002/jeq2.20267

Ceschin, S., Aleffi, M., Bisceglie, S., Savo, V., and Zuccarello, V. (2012). Aquatic bryophytes as ecological indicators of the water quality status in the Tiber River basin (Italy). Ecol. Ind. 14 (1), 74–81. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.08.020

Ceschin, S., Minciardi, M. R., Spada, C. D., and Abati, S. (2015). Bryophytes of alpine and apennine Mountain streams: floristic features and ecological notes. Cryptogam. Bryol. 36 (3), 267–283. doi:10.7872/cryb/v36.iss3.2015.267

Council of the European Communities (2000). Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. OJEC L327 43, 1–73.

Dawson, F., Newman, J. R., Gravelle, M. J., Rouen, K. J., and Henville, P. (1999). Assessment of the trophic status of Rivers using macrophytes. Bristol, UK: Environmental Agency.

EuroMed PlantBase (2006). Euro+Med PlantBase. Midlothian, UK: EuroMed PlantBase. Available online at: https://europlusmed.org/(Accessed September 20, 2025).

Ganeva, A. (1997). Bryophyte flora of the Parangalitza Biosphere Reserve, Rila Mountain. Ann. Univ. Sofia 89 (2), 35–47.

Ganeva, A. (2000). “Biodiversity of Bryophytes in Rila National Park” in: biological diversity of the Rila National Park, part I”. In: M. Sakalian, editor. Plant biodiversity of the central balkan national park. Species and coenotic levels. Arlington, VA: USAID. p. 117–136.

Ganeva, A., and Düll, R. (1999). A contribution to the Bulgarian bryoflora. Checklist of Bulgarian bryophytes. In: R. Düll, A. Ganeva, A. Martincic, and Z. Pavletic, editors. Contributions to the bryoflora of former yugoslavia and Bulgaria. 1st edn. Bad Münstereifel, Germany: IDH-Verlag. p. 111–199.

Ganeva, A., Papp, B., and Natcheva, R. (2008). Contribution to the bryophyte flora of the NW Bulgaria. Phytol. Balcan. 14 (3), 327–333.

Gecheva, G., Yurukova, L., Cheshmedjiev, S., and Ganeva, A. (2010). Distribution and bioindication role of aquatic bryophytes in Bulgarian Rivers. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. Spec. Edition/Online 24, 164–170. doi:10.1080/13102818.2010.10817833

Gecheva, G., Dimitrova-Dyugerova, I., and Cheshmedjiev, S. (2013). Macrophytes. In: D. Belkinova, and G. Gecheva, editors. Biological analysis and ecological assessment of the surface water types in Bulgaria. Plovdiv, Bulgaria: Plovdiv University Press. p. 127–146.

Gecheva, G., Pall, K., Todorov, M., Traykov, I., Gribacheva, N., Stankova, S., et al. (2021). Anthropogenic stressors in upland Rivers: aquatic macrophyte responses. A case study from Bulgaria. Plants 10 (12), 2708. doi:10.3390/plants10122708

Gecheva, G., Stankova, S., Varbanova, E., Kaynarova, L., Georgieva, D., and Stefanova, V. (2023). Macrophyte-based assessment of upland Rivers: bioindicators and biomonitors. Plants 12 (6), 1366. doi:10.3390/plants12061366

Glime, J. M. (1982). Response of Fontinalis hypnoides to seasonal temperature variations. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 53, 181–190.

Glime, J. M. (2017a). Water relations: habitats. Chaps. 7-8. In: J. M. Glime, editor. Bryophyte ecology. Houghton, MI: Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Available online at: http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/(Accessed September 27, 2025).

Glime, J. M. (2017b). Nutrient relations: requirements and sources. Chapt. 8-1.In: B. Ecology, and J. M. Glime, editors. Physiological ecology. Houghton, MI: Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Available online at: http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/(Accessed September 27, 2025).

Glime, J. M. (2020). Streams: life and growth forms and life strategies. Chaps. 2-5. In: J. M. Glime, editor. Bryophyte ecology. Houghton, MI: Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Available online at: http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/ (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Hájek, M., Tzonev, R. T., Hájková, P., Ganeva, A. S., and Apostolova, I. (2005). Plant communities of the subalpine mires and springs in the vitosha Mt. Phytol. Balcan. 11 (2), 193–205.

Haury, J., Peltre, M.-C., Trémolières, M., Barbe, J., Thiébaut, G., Bernez, I., et al. (2006). A new method to assess water trophy and organic pollution - the macrophytes biological index for Rivers (IBMR): its application to different types of river and pollution. Hydrobiol 570, 153–158. doi:10.1007/s10750-006-0175-3

Hill, M. O., Bell, N., Bruggeman-Nannenga, M. A., Brugués, M., Cano, M. J., Enroth, J., et al. (2006). An annotated checklist of the mosses of Europe and Macaronesia. J. Bryol. 28, 198–267. doi:10.1179/174328206X119998

Hunter, J. D. (2007). Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. CiSE 9 (3), 90–95. doi:10.1109/mcse.2007.55

Kaijser, W., Birk, S., and Hering, D. (2022). Environmental ranges discriminating between macrophytes groups in European rivers. PLoS ONE 17 (6), e0269744. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0269744

Kohler, A. (1978). Methoden der Kartierung von Flora und Vegetation von Süßwasserbiotopen. Landschaft Stadt 10, 73–85.

Lang, P., and Murphy, K. J. (2012). Environmental drivers, life strategies and bioindicator capacity of bryophyte communities in high-latitude headwater streams. Hydrobiol 679, 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10750-011-0838-6

McKinney, W. (2010). Data structures for statistical computing in Python. In: Proceedings of the 9th python in science conference. p. 51–56.

Papp, B., Ganeva, A., and Natcheva, R. (2006). Bryophyte vegetation of Iskur River and its main tributaries. Phytol. Balcan. 12 (2), 181–189.

Papp, B., Natcheva, R., and Ganeva, A. (2011). The bryophyte flora of Northern Mt Strandzha. Phytol. Balcan. 17 (1), 21–32.

Podpéra, J. (1911). Ein Beitrag zu der Kryptogamenflora der bulgarischen Hochgebirge. Beih. Bot. Cent. 28 (2), 173–224.

Python Software Foundation (2023). Python Language Reference, version 3.10. Beaverton, OR: Python Software Foundation. Available online at: https://www.python.org/.

Rajala, S., Estlander, S., Nurminen, L., and Horppila, J. (2025). Investigating tools for biomonitoring browning in streams: chlorophyll content of Fontinalis antipyretica. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 426, 16. doi:10.1051/kmae/2025013

Rimac, A., Alegro, A., Šegota, V., Vukovi ́c, N., and Koleti ́c, N. (2022). Ecological preferences and indication potential of freshwater bryophytes - insights from Croatian watercourses. Plants 11, 3451. doi:10.3390/plants11243451

Scarlett, P., and O’Hare, M. (2006). Community structure of In-Stream bryophytes in English and Welsh Rivers. Hydrobiol 553, 143–152. doi:10.1007/s10750-005-1078-4

Schaumburg, J., Schranz, C., Foerster, J., Gutowski, A., Hofmann, G., Meilinger, P., et al. (2004). Ecological classification of macrophytes and phytobenthos for rivers in Germany according to the Water Framework Directive. Limnol 34, 283–301. doi:10.1016/S0075-9511(04)80002-1

Simmel, J., Ahrens, M., and Poschlod, P. (2021). Ellenberg N values of bryophytes in Central Europe. J. Veg. Sci. 32 (1), e12957. doi:10.1111/jvs.12957

StatSoft Inc (2013). STATISTICA (data analysis software system). Tulsa, OK: StatSoft Inc. version 12.

Szoszkiewicz, K., Jusik, S., Kowalkowski, T., and Gebler, D. (2019). The macrophyte index for Rivers (MIR) as an advantageous approach to running water assessment in local geographical conditions. Water 12 (1), 108. doi:10.3390/w12010108

Ter Braak, C. J. F., and Smilauer, P. (2002). CANOCO reference manual and CanoDraw for Windows user's guide: software for canonical community ordination. Ithaca: Microcomputer Power. version 4.5.

Tremp, H., and Kohler, A. (1995). The usefulness of macrophyte Monitoring-Systems, exemplified on eutrophication and acidification of running waters. Acta Bot. Gall. 142, 541–550. doi:10.1080/12538078.1995.10515277

Vanderpoorten, A., Klein, J. P., Stieperaere, H., and Trémolières, M. (1999). Variations of aquatic bryophyte assemblages in the rhine rift related toWater quality. 1. The Alsatian rhine floodplain. J. Bryol. 21, 17–23. doi:10.1179/jbr.1999.21.1.17

Vázquez, M. D., Real, C., and Villares, R. (2020). Optimization of the biomonitoring technique with the aquatic moss Fontinalis antipyretica hedw.: selection of shoot segment length for determining trace element concentrations. Water 12 (9), 2389. doi:10.3390/w12092389

Vieira, C., Aguiar, F. C., and Ferreira, M. T. (2014). The relevance of bryophytes in the macrophyte-based reference conditions in Portuguese Rivers. Hydrobiol 737, 245–264. doi:10.1007/s10750-013-1784-2

Keywords: Fontinalis antipyretica, Fontinalis hypnoides, aquatic moss, indicator, reference condition

Citation: Gecheva G, Natcheva R and Ganeva A (2025) Ecological patterns of Fontinalis antipyretica and Fontinalis hypnoides distribution in Bulgarian rivers, and relevance to ecological status assessment. Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1715526. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1715526

Received: 29 September 2025; Accepted: 20 November 2025;

Published: 28 November 2025.

Edited by:

Dragana Vukov, University of Novi Sad, SerbiaReviewed by:

Dragana Jenačković Gocić, University of Niš, SerbiaAnja Rimac, University of Zagreb, Croatia

Katarina Misikova, Comenius University, Slovakia

Copyright © 2025 Gecheva, Natcheva and Ganeva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gana Gecheva, Z2dlY2hldmFAbWFpbC5iZw==

Gana Gecheva

Gana Gecheva Rayna Natcheva2

Rayna Natcheva2 Anna Ganeva

Anna Ganeva