- 1Gansu Key Laboratory of Groundwater Engineering and Geothermal Resources, Lanzhou, China

- 2Gansu Geological Environment Monitoring Institute, Lanzhou, China

- 3School of Earth Sciences and Engineering, Hohai University, Nanjing, China

- 4Gansu Hydrological and Water Resources Survey Center, Wuwei, China

Introduction: Jinchang City, an arid inland city in Northwest China, is among the country’s 110 most water-stressed cities with a per capita water resource of 1,173 m3—far below provincial and national averages. Rapid agricultural land expansion and large-scale groundwater exploitation have led to continuous groundwater level decline, threatening regional ecology, production, and livelihoods. However, the impact of groundwater dynamics on hydrochemistry and the key drivers of water level decline in this region remain insufficiently elucidated. This study aims to address these gaps to provide insights for targeted groundwater management.

Methods: We utilized two core datasets: hydrochemical data from 13 national monitoring wells (collected in September 2023) and monthly groundwater level data spanning 2017–2023. Multiple analytical tools were integrated, including statistical analysis (SPSS 20.0), hydrochemical graphing (Origin 2021), spatial interpolation (Surfer), and an optimized random forest model (R software, ntree = 50, mtry = 2) with model performance metrics of R2 = 0.83 and RMSE = 0.19 m. These methods were combined to analyze hydrochemical characteristics and identify drivers of groundwater level changes.

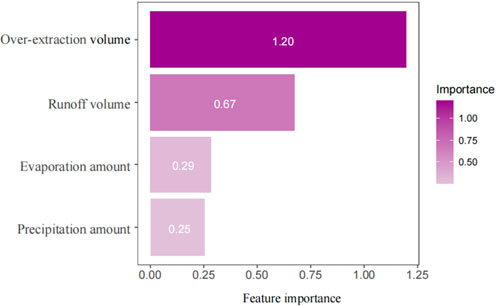

Results: (1) Groundwater in the study area is slightly alkaline, with a pH range of 7.50–7.90 (average 7.73). Total hardness (TH) varies from 229 to 1720 mg/L (average 569.62 mg/L) and total dissolved solids (TDS) from 334 to 2,420 mg/L (average 905.92 mg/L). Dominant cations follow the order Ca2+ > Na+ > Mg2+ > K+, and dominant anions SO42− > HCO3− > Cl− > NO3−, with Ca-SO4 as the main hydrochemical type. (2) Hydrochemical evolution is jointly controlled by silicate weathering, carbonate dissolution, and evaporite dissolution: Ca2+ and Mg2+ derive from carbonates and silicates; Na+ mainly comes from halite dissolution (with minor silicate contribution); SO42− and Cl− primarily originate from carbonates supplemented by evaporites. (3) Groundwater level dropped by 2.26 m from 2017 to 2023, with an average annual decline of 0.38 m. Random forest analysis identified over-exploitation (importance index = 1.2) and reduced runoff (0.67) as the primary driving factors. (4) Level decline was associated with increased ion concentrations (with SO42− and NO3− exceeding standards), exacerbated pollution accumulation, and destabilized hydrochemical types.

Discussion: These findings clarify the coupling relationship between groundwater dynamics and hydrochemistry in arid inland areas, filling the local research gap in systematic hydrogeochemical analysis. The identification of over-exploitation and reduced runoff as key drivers aligns with the region’s agricultural development and water resource management context. Practically, the results provide a scientific basis for groundwater sustainability in Jinchang City: they support targeted measures for managers (e.g., controlling over-exploitation in central agricultural areas, optimizing upstream water diversion, and promoting water-saving irrigation) and help raise community awareness of water scarcity for rational water use. Future research could expand monitoring density to refine driver analysis across smaller spatial scales.

1 Introduction

Groundwater is a vital resource for sustaining ecosystems, agricultural irrigation, and socioeconomic development in arid and semi-arid regions (Jasechko et al., 2017). This is particularly true for the inland river basins of Northwest China, where water scarcity is exacerbated by low precipitation, high evaporation, and increasing human demands (Li et al., 2020). In these fragile environments, the over-exploitation of groundwater has triggered a series of ecological and environmental problems, including continuous water-level decline, water quality deterioration, and land desertification (Min et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2014). The originally fragile natural environment together with the predatory use of ecological resources has disturbed the initial hydro-ecological balance, which poses a great challenge for sustainable watershed management (Ye et al., 2011).

The Shiyang River Basin, a typical inland basin in the Hexi Corridor, exemplifies this water crisis. Extensive research has been conducted within this basin to understand its hydrological and hydrogeochemical processes. Previous studies have primarily focused on: (1) Hydrochemical characteristics and ion sources in the upper reaches (Zhang et al., 2021); (2) Spatiotemporal patterns of hydrochemistry across the basin (Yang et al., 2018); (3) Long-term trends in groundwater levels and the quantification of driving factors using statistical methods like linear trend analysis and multiple general linear models (Min et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2014). Furthermore, the application of machine learning (ML) techniques, such as the Random Forest (RF) model, has shown great promise in identifying key drivers of groundwater dynamics in other regions, demonstrating superiority over traditional statistical methods (Tyralis et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2024). Recent regional-scale studies have further advanced this field by integrating hydrochemistry and ML for groundwater quality assessment (e.g., Al-Mashreki et al., 2023; Gad and EL Osta, 2020; Hfaiedh et al., 2025a), while some have emphasized the need for long-term monitoring to capture dynamic hydrogeochemical responses to environmental changes. For instance, Gad et al. (2023) highlighted that arid-region groundwater research requires coupling long-term level data with hydrochemical tracing to disentangle natural and anthropogenic impacts, a framework that has not yet been applied to Jinchang. Similarly, studies on other arid basins have underscored the value of integrating RF models with hydrochemical analysis to quantify drivers of groundwater evolution, but such integrated approaches remain absent at the local scale of Jinchang. Naghibi et al. (2017) also compared the application of support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and genetic algorithm optimized random forest (RFGA) in groundwater potential assessment, analyzing the contribution of variables such as climate, geology, and land use.

However, a significant research gap persists at the local scale, specifically for Jinchang City, which is a key and highly stressed node within the lower reaches of the Shiyang River Basin. Existing research on Jinchang’s groundwater is relatively limited. The seminal work by Ma et al. (2010) utilized isotopes and hydrogeochemistry to investigate recharge sources and geochemical evolution, but a comprehensive study integrating long-term groundwater level dynamics with hydrochemical evolution is still lacking. Furthermore, While recent studies have advanced integrated hydrochemical-ML frameworks for arid-region groundwater research (e.g., Hfaiedh et al., 2025b), these have focused on regional-scale assessments or other arid basins, failing to address the unique hydrological pressures (e.g., intensive agricultural exploitation, upstream dam construction) faced by Jinchang. Crucially, the following aspects remain unaddressed:

1. A systematic analysis of the quantitative relationship between the declining groundwater level (2017–2023) and the evolution of hydrochemical characteristics in Jinchang, which is essential to understand quality deterioration mechanisms in this water-stressed city;

2. A machine-learning driven quantification of the relative importance of factors (e.g., over-exploitation, runoff reduction, climate) controlling the water-level decline, moving beyond the qualitative or regional-scale assessments of previous studies (e.g., El Osta et al., 2022);

3. A clear elucidation of the feedbacks and mechanisms through which groundwater depletion impacts water-rock interactions and pollutant accumulation, which has been highlighted as a priority for arid-region groundwater management (Gad et al., 2023) but not yet explored for Jinchang.

To bridge these gaps, this study aims to achieve the following specific objectives: To systematically characterize the hydrochemical properties and evolution mechanisms of groundwater in Jinchang City; To analyze the spatiotemporal dynamics of the groundwater level from 2017 to 2023 and identify its intra-annual and inter-annual variation patterns; To employ the Random Forest algorithm to quantify the relative importance of key influencing factors (e.g., over-exploitation, runoff, precipitation, evaporation) on the groundwater level decline; To elucidate the potential impacts of groundwater level decline on hydrochemical processes, including ion concentration and water type stability. This study innovatively integrates long-term groundwater level monitoring (2017–2023), modern hydrochemical data (2023), and RF machine learning for Jinchang specifically—an approach that advances beyond regional-scale studies (e.g., Yang et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2024) and fills the local-scale gap in integrated hydrological-hydrochemical-ML research. Given the gradual decline of groundwater levels in Jinchang City in recent years, and considering that groundwater, as a guaranteed natural resource and strategic economic resource in arid regions, plays a pivotal role in maintaining regional ecological balance, supporting industrial and agricultural production, and ensuring people’s livelihoods, the implementation of this study holds significant practical significance and scientific value.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

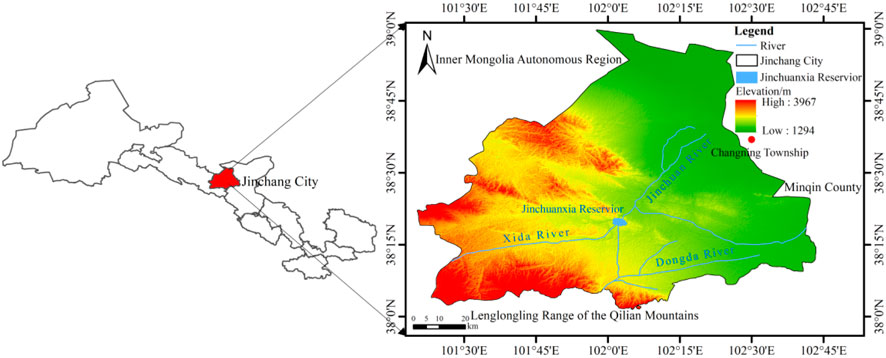

Jinchang City is located in the northwestern part of Gansu Province. It is a key node on the ancient Silk Road and an important city in the eastern Hexi Corridor. As shown in Figure 1, it is situated on the northern slope of the Qilian Mountains and the southern edge of the Alxa Plateau, between 37°47′10″N-39°00′30″N and 101°04′35″E−102°43′40″E. The city features a unique geographical layout, bordered by distinct administrative regions. To the northeast, it borders Minqin County; to the southwest, it adjoins Menyuan Hui Autonomous County of Qinghai Province; to the northwest, it borders the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Chang et al., 2023). The city stretches about 145 km from east to west and about 135 km from north to south, with a total boundary length of 486 km. It is one of the 110 most water stressed cities in China, with per capita water resources only 1,173 m3, far lower than that of provincial and national average. The city has a typical temperate continental climate with dryness all year round and little precipitation, leading to especially harsh natural environmental conditions. Surface water and groundwater resources in Jinchang mainly come from natural precipitation, glacier melting water and snow melting water in the southern Qilian Mountains, forming surface runoff and recharging groundwater through infiltration. The main rivers in the study area, including the Jinchuan River, Dongda River and Xida River, all originate from the Lenglongling Range of the Qilian Mountains, and they belong to the Shiyang River watershed system.

2.2 Regional hydrogeological conditions

The plain area of Jinchang city in the Shiyang River Basin contains five hydrogeological basins, four in the middle reaches (all in Yongchang county) and one in the lower reaches (in Jinchuan district). The four middle reach basins are the Wuwei Basin, Hongshanyao-Yueyahu Basin, Maobula Basin and Yongchang Basin, whilst the northern (lower reach) basin is the Jinchang-Changning Basin (Stallard and Edmond, 1983). Due to the limited variability in hydrogeological conditions between the basins, the Changning Basin represents the most typical hydrogeological unit in Jinchang city. It covers the lower western part of the Shiyang River Basin in the central-western plains, covering the southwestern part of Minqin county and the central-southern part of Jinchuan district administratively, which includes the full geographical extent of the basin itself.

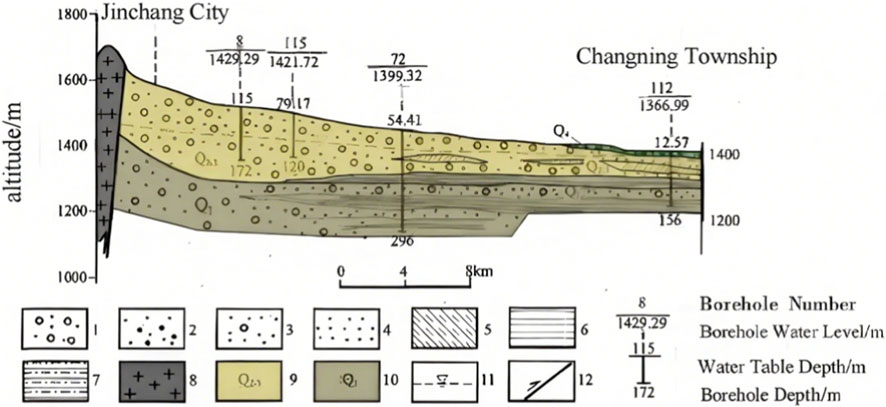

The basic hydrogeology of the study area is used for groundwater zoning. To the east of the study area is the Minqin Basin, the Longshou Mountains form the western and southern boundary, and to the north is the Chaoshuidong Basin. The groundwater system mainly consists of Quaternary unconsolidated porous aquifers with local recharge to karst-fracture water. The Changning Basin is located in the western downstream part of the Shiyang River Basin, and is part of the Xida River terminal area (Jiang et al., 2018). The basin is surrounded by the Longshou Mountain range in the south, north and west, and connects to the Minqin Basin in the east. The Quaternary deposits in the basin vary in thickness from 80 to 300 m, gradually thinning from west to east. As shown in Figure 2, lithologically, the western part (from Jinchang City to Xiafen region) is mainly gravel-pebble and sandy gravel formation, and most other parts are interbedded layers of sandy gravel, sand, and clay. Well yield ranges from 1,000 to 5,000 m3/day, and the total dissolved solids are generally 0.49–2.64 g/L (localities >5 g/L). Monitoring data from the Changshengtoujingzi observation wells in the northeast of the basin show that the groundwater level has fallen by 14.72 m over the last 2 decades, which is equivalent to an average annual reduction of 0.51 m. The groundwater system is mainly recharged by the mountain-front lateral inflow and the river channel infiltration. The flow pattern is similar to the Minqin Basin, converging radially from the periphery to the center of the basin. Evaporation and human extraction are the main discharge in this area (Liu et al., 2001).

Figure 2. Hydrogeological cross-section of the Changning Basin. 1. Gravel stratum; 2. Sandy gravel; 3. Gravelly sand; 4. Sand; 5. Cohesive soil; 6. Mudstone; 7. Sandy mudstone and argillaceous sandstone; 8. Granite; 9. Middle-Upper Pleistocene aquifer system; 10. Lower Pleistocene aquifer system; 11. Phreatic surface; 12. Fault.

2.3 Data and methods

2.3.1 Groundwater level monitoring data

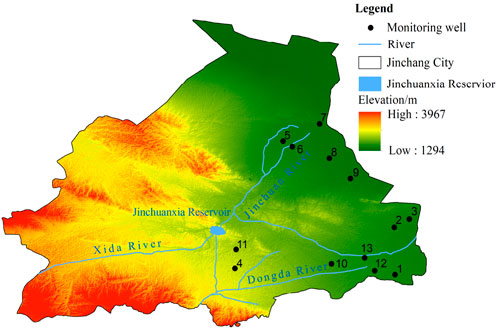

This study collected 1,092 groundwater depth data from 13 national-level monitoring sites in Jinchang City covering monthly observations from 2017 to 2023, and hydrochemical data of each well in September 2023, the distribution map of groundwater monitoring wells is shown in Figure 3 below. Follow strictly the Technical Specifications for Groundwater Environmental Monitoring (HJ 164–2020) for sampling, storage and transportation. The main testing indicators of hydrochemistry are pH value, total hardness, TDS, Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Na+, Fe3+, Mn2+, Cl−, SO42-, HCO3−, NO3− content, etc. The pH value is measured in situ, and the other testing indicators are finished by the Testing Center of Key Laboratory of Groundwater Engineering and Geothermal Resources in Gansu Province.

2.3.2 Research method

Statistical analysis of water quality data in this study was completed in SPSS 20.0. Ionic ratio analysis and the creation of Piper trilinear and Gibbs diagrams were accomplished in Origin 2021. Annual variation in the groundwater level in Jinchang City from 2017 to 2023 was statistically analyzed. Surfer software was used for Kriging interpolation to create maps of the groundwater depth contour, illustrating the dynamic changes and spatial distribution characteristics of the groundwater level. In order to analyze the relative importance of factors affecting the water level variation, a random forest model was built by randomForest package in R. Hyperparameters were tuned by cross-validation and grid search through the train function to find the optimal number of randomly selected features (mtry), and the optimal number of trees (ntree) was determined by minimizing the out-of-bag (OOB) error rate (Wen et al., 2025). The Gini index was computed to evaluate the importance of precipitation, runoff, and groundwater extraction on the decline of the groundwater level in Jinchang City from 2017 to 2023. After training and tuning, the OOB error rate was minimized at ntree = 50 and mtry = 2. The model achieved a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.83 and a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.19 m. These values indicate that the model explains 83% of the variation in groundwater level depth and has a low prediction error, confirming its reliability for identifying key influencing factors.

The random forest algorithm is a Bagging ensemble method based on CART decision trees, which is a very flexible machine learning technique for accurate regression and classification tasks on large data sets (Breiman, 1996). During the training process, the algorithm builds multiple classification trees based on the acquired sample set, where each tree includes independent feature attributes as decision inputs. The main parameters of the model are the number of decision tree classifiers and the number of randomly selected predictor variables for each tree, which can effectively avoid over-fitting and show better performance in dealing with complex classification problems (Breiman, 2001). Hastie et al. (2009) provided a comprehensive statistical foundation for such ensemble methods, while Kuhn and Johnson (2013) emphasized the importance of hyperparameter tuning in maximizing model performance, as implemented in our study.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Groundwater hydrochemical characteristics

3.1.1 Main chemical component characteristic statistics

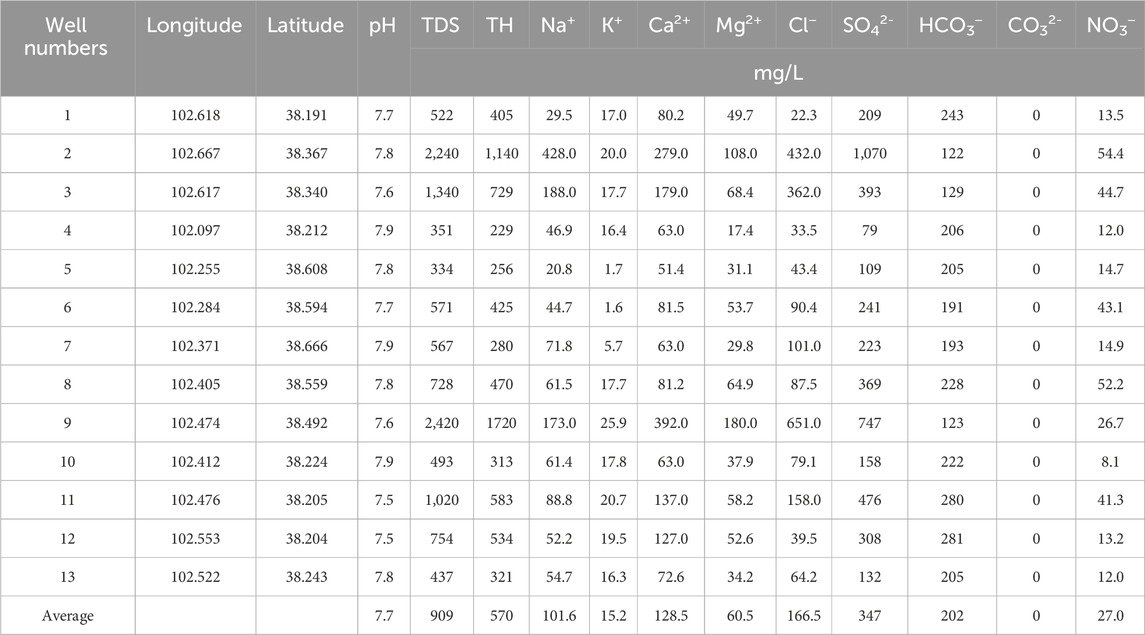

The statistical results of hydrochemical characteristics of groundwater in Jinchang City are shown in Table 1. The pH of groundwater in Jinchang City ranged from 7.50 to 7.90, with an average value of 7.73, indicating slightly alkaline conditions. The total hardness (TH) of groundwater ranged from 229 to 1720 mg/L, with a mean value of 569.62 mg/L. The proportion of samples classified as hard water (150 mg/L < TH < 450 mg/L) and very hard water (TH > 450 mg/L) was 54% and 46%, respectively (i.e., 7 out of 13 samples belonged to hard water and 6 out of 13 samples belonged to very hard water). Respectively. The total dissolved solids (TDS) of groundwater ranged from 334 to 2,420 mg/L, with a mean value of 905.92 mg/L. The proportion of fresh water (TDS <1,000 mg/L) and brackish water (1,000 mg/L < TDS <3,000 mg/L) was 69% and 31%, respectively (i.e., 9 out of 13 samples belonged to fresh water and 4 out of 13 samples belonged to brackish water). The main cations followed the order Ca2+ > Na+ > Mg2+ > K+, and the main anions followed the order SO42- > HCO3− > Cl− > NO3−. The predominant anion and cation were SO42- and Ca2+, respectively. It is worth noting that the average concentrations of SO42-, NO3− and TH exceeded Class III standards of the “Quality Standard for Groundwater” (GB/T 14,848–2017) and the “Standards for Drinking Water Quality” (GB 5749–2022). This suggests that the quality of groundwater in Jinchang City may have been affected by human activities.

3.1.2 Hydrochemical type

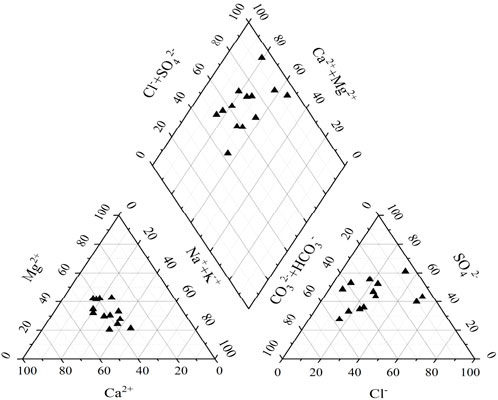

The Piper trilinear diagram is a powerful analytical instrument for studying the evolution patterns of groundwater chemical composition, extensively used for hydrochemical components analysis, with the obvious benefit of removing subjective human interference and clearly presenting the proportion of different ions (Piper, 1944). Piper trilinear diagrams of groundwater chemistry in the study area were constructed using Origin software to analyze hydrochemical types and features systematically. All sampling points are located in the mixed zone and Ca2+ end-member zone in the cation plot, whereas most sampling points are concentrated in the mixed zone and SO42- end-member zone in the anion plot (Figure 4). Based on the Shukarev method, the dominant hydrochemical type of Jinchangs groundwater is Ca-SO4 (accounting for 69% of samples), followed by mixed types (23%).

Based on Langguth’s (1966) classification, which relies on percentage of milligram equivalent of major cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na++K+) and anions (HCO3−, SO42-, Cl−), the hydrochemical types of the 13 wells are analyzed as follows (Table 2): Consistent with the Piper diagram, most samples are dominated by Ca2+-Mg2+ mixed cations and HCO3−-SO42- mixed or SO42- dominant anions, reflecting control by carbonate-silicate weathering and sulfate-rich sources. The dominance of Ca2+ and SO42- ions in regional groundwater suggests that aquifer chemistry is jointly controlled by various hydrogeochemical processes and anthropogenic activities.

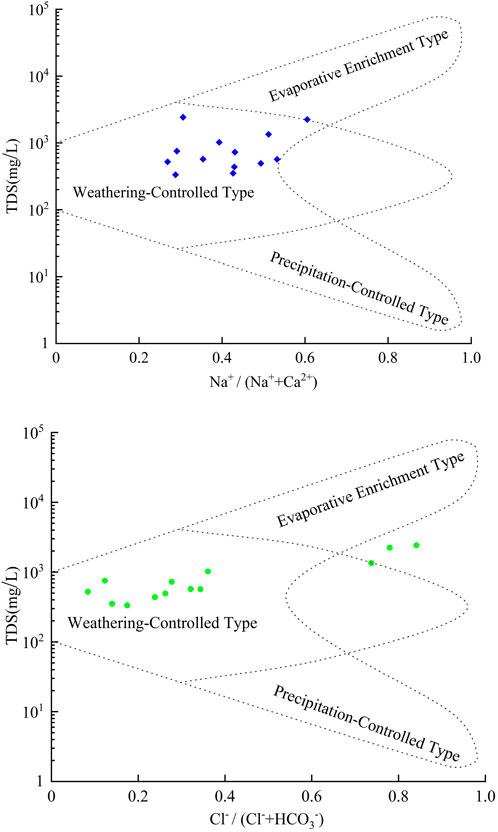

3.1.3 Analysis of the genesis of hydrochemical characteristics of groundwater

The Gibbs diagram is extensively utilized to elucidate hydrochemical formation mechanisms by classifying natural water controlling factors into three distinct categories: precipitation dominance, rock weathering dominance, and evaporation-crystallization dominance. The primary mechanism governing hydrochemical characteristics can be determined through analyzing the spatial distribution of sample points within the diagram (Gibbs, 1970). Given the study area’s arid climate with limited precipitation, combined with intensive groundwater extraction which alters natural flow paths, the Na+/(Na++Ca2+) and Cl−/(Cl− + HCO3−) ratios in the groundwater samples of the research area are almost all less than 0.5 or close to 0.5, which falls within the control range of rock weathering (Figure 5), indicating that rock weathering serves as the predominant control factor for major ion sources across various aquifers. Some sampling points deviate from these three primary domains, potentially influenced by ion exchange processes or anthropogenic activities. Singh et al. (2021) also observed such deviations in arid alluvial aquifers, attributing them to localized anthropogenic inputs or complex weathering sequences.

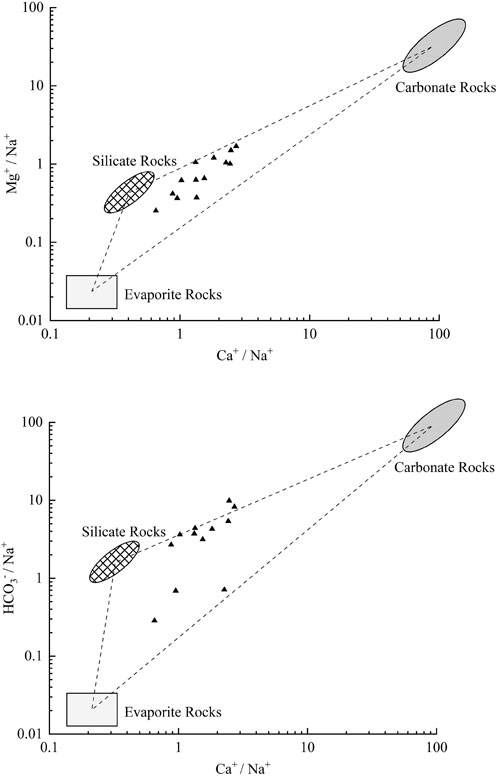

The different combinations of parent rock types (such as carbonates, silicates, and evaporites) in river catchments result in variations in the cation and anion compositions among different rivers (Chen et al., 2002). For instance, Ca2+ and Mg2+ originate from the weathering or dissolution of carbonates, silicates, and evaporites; Na+ and K+ come from evaporites or the weathering of silicates; HCO3− is derived from carbonates and silicates. Ca2+/Na+, Mg2+/Na+, and HCO3−/Na+ are not affected by flow rate, dilution and evaporation, and their relationship can reveal the hydrochemical origin, that is, the dissolution of which minerals the main ions come from (Thomas et al., 2015). As shown in Figure 6, most sampling points cluster between the silicate and carbonate rock fields, with a larger number in the silicate field, indicating that silicate weathering has the dominant effect on groundwater chemistry, followed by carbonate dissolution. All sampling points are located far away from the evaporite weathering field, suggesting negligible evaporite dissolution contribution to groundwater solutes in the study area.

3.1.4 Main ion sources

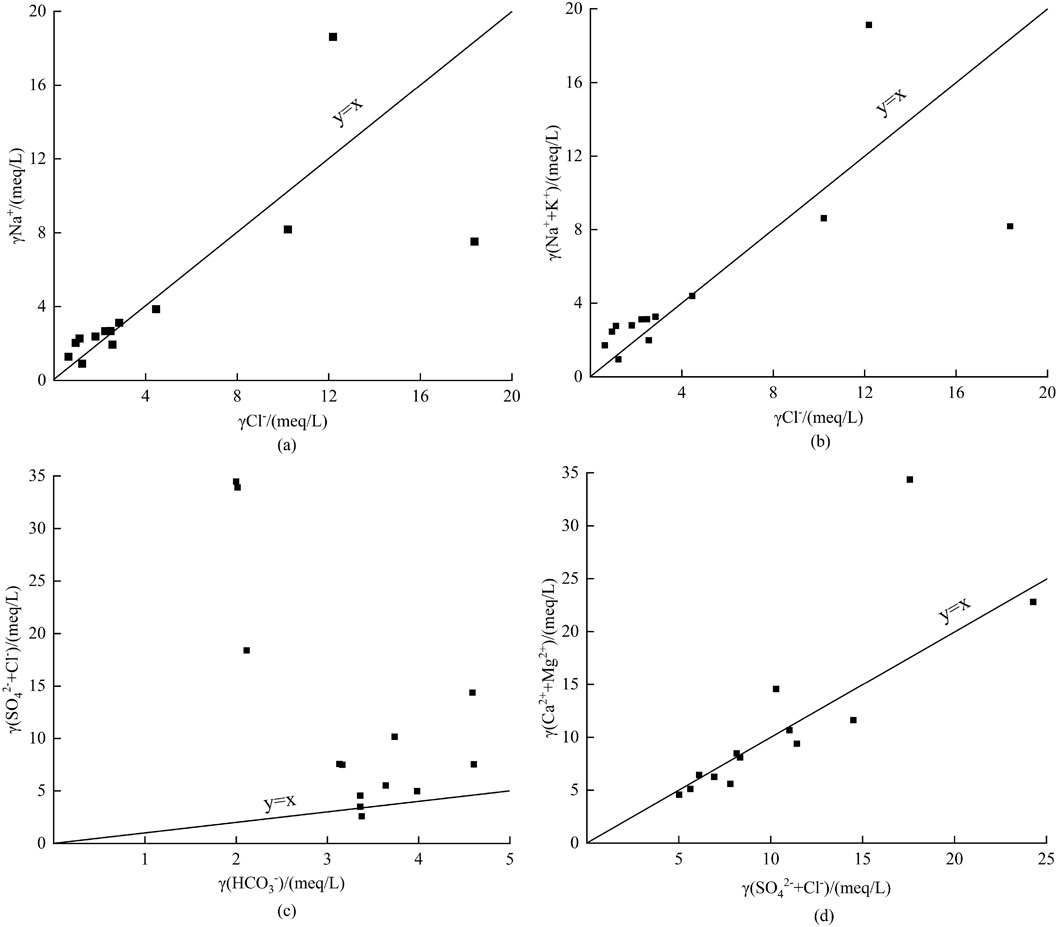

The ratio of Na+ to Cl− in milliequivalent concentration (γ) is a useful indicator of the sources of these ions in groundwater. In the absence of anthropogenic influence, Na+ to Cl− in groundwater are mainly derived from halite dissolution (Zhang et al., 2025). Most of the ground water samples from the study area plot close to but slightly above the y = x line suggesting that the Na+ concentration is slightly higher than Cl− concentration and therefore halite dissolution is the major source of Na+, with a minor contribution from silicate weathering or cation exchange (Figure 7a).

Figure 7. Hydrochemical ionic ratio relationships in groundwater. (a) Relationship between γNa+ and γCl−. (b) Relationship between γ(Na++K+) and γCl−. (c) Relationship between γ(SO42−+Cl−) and γ(HCO3−). (d) Relationship between (Ca2+ + Mg2+) and γ(SO42−+Cl−).

The γ(Na++K+)/γCl− ratio offers additional indication for recognizing possible aluminosilicate mineral dissolution (Gibbs, 1970). Most samples group close to and above the y = x line in the γ(Na++K+) versus γCl− plot (Figure 7b), confirming that both halite dissolution and aluminosilicate weathering play a role in the groundwater chemistry. Scanlon et al. (2005) found comparable ionic relationships in the Hexi Corridor, reinforcing the regional significance of silicate weathering. The relationship between γHCO3- and γ(SO42- + Cl−) helps to identify the main sources of SO42- and Cl− (Goldberg, 2006). Most samples plot above the y = x line in the γHCO3- versus γ(SO42- + Cl−) diagram (Figure 7c), with a few below, showing that carbonate dissolution is the dominant source of SO42- and Cl−, whereas evaporite dissolution contributes partially.

The sources of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in groundwater, mainly derived from carbonate, silicate or evaporite dissolution, can be assessed by the milliequivalent ratio of (Ca2+ + Mg2+) to (HCO3− + SO42-) (Umar and Absar, 2003). Most samples in Figure 7d plot along the y = x line, suggesting that carbonate and silicate dissolution are the main sources of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the groundwater of the study area.

3.2 Characteristics of dynamic changes in groundwater

3.2.1 Dynamic changes within the year

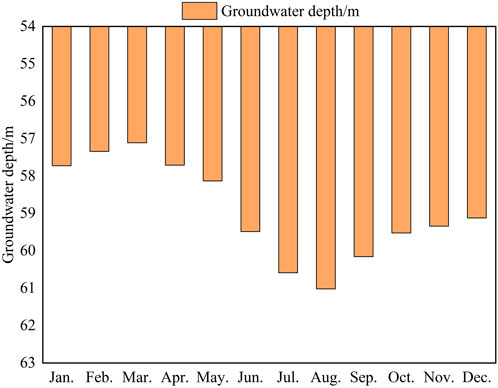

The groundwater level in Jinchang City fluctuates greatly within a year, mainly controlled by the East Asian continental climate pattern, which leads to concentrated and abundant precipitation in the flood season, scarce and unstable rainfall in spring, and extremely low snowfall in winter. Taking the 2022 monthly variation of groundwater depth as an example (Figure 8), three hydrological stages can be identified: the January-March period has the least precipitation but the lowest agricultural extraction, resulting in the recovery of groundwater, and the minimum groundwater depth usually appears in February or March; the April-August period has obvious groundwater depletion due to intensive irrigation pumping and over-exploitation, and the maximum groundwater depth is usually observed in July or August; the September-October period has significant groundwater recharge caused by abundant monsoon rainfall, and the water level gradually recovers; the November-December period has relatively stable groundwater level because the agricultural water consumption decreases significantly.

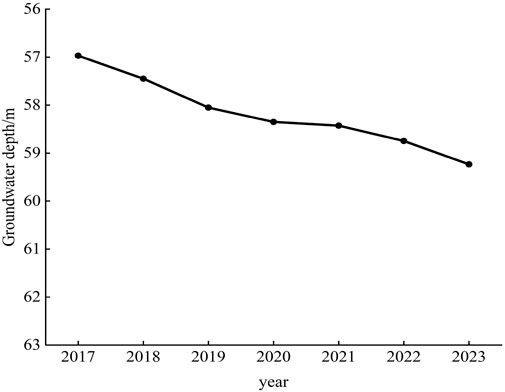

3.2.2 Interannual dynamic variation

The period between 2017 and 2020 saw a large expansion of agricultural production that directly caused a significant increase in groundwater extraction, resulting in continuous decline of the groundwater level with a total decline of 1.38 m (average 0.46 m/a). Between 2020 and 2023, although there were regulations on irrigation, the groundwater level kept declining (total decline 0.88 m, average 0.29 m/a) mainly because the surface runoff was greatly reduced due to the construction of the upstream Hanjaxia Dam in 2020, which led to a reduction in surface water infiltration recharge (Figure 9).

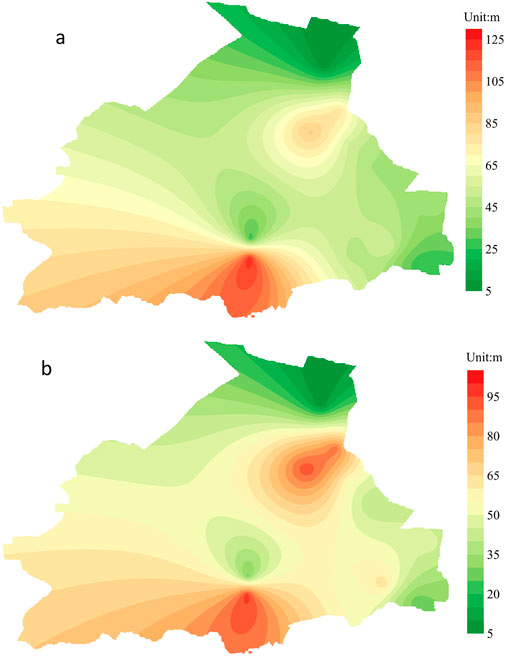

Comparative analysis of the 2017 and 2023 groundwater depth contour maps (Figure 10) reveals that the most pronounced increases in groundwater depth occurred predominantly in central Jinchang areas characterized by intensive human activities and substantial groundwater extraction, clearly demonstrating the dominant anthropogenic influence on groundwater level variations in the region.

3.2.3 Mechanisms linking groundwater level decline to hydrochemical evolution

The continuous decline of the groundwater table in Jinchang City initiates a series of interconnected hydrogeochemical processes that fundamentally alter groundwater quality, moving beyond simple concentration effects to changes in dominant geochemical pathways.

1. Altered Flow Paths, Prolonged Residence Times, and Enhanced Water-Rock Interactions: The lowering of the groundwater table increases the vadose zone thickness and alters groundwater flow paths. Groundwater must now traverse a longer and more complex path through the aquifer matrix to reach extraction points. This significantly prolongs the hydraulic residence time, thereby facilitating more thorough and extensive water-rock interactions (Scanlon et al., 2005). The prolonged contact facilitates the continued dissolution of silicate and carbonate minerals (e.g., calcite, dolomite, gypsum), leading to a systematic increase in the concentrations of major ions such as Ca2+, Mg2+, SO42-, and HCO3−. This process is a primary contributor to the observed high Total Hardness (avg. 569.62 mg/L) and the prevalence of Ca-SO4 type water.

2. Reduction in Recharge and the Weakening of the Dilution Effect: As the groundwater table deepens, the volume of active groundwater circulation is reduced. More critically, the reduced hydraulic head gradient diminishes the influx of fresher, modern recharge water. This weakens the natural dilution capacity of the aquifer system. Consequently, pollutants introduced from agricultural activities, particularly nitrate (NO3−), are no longer effectively diluted. This leads to their accumulation and elevated concentrations, explaining why NO3− levels frequently exceed regulatory standards. Similarly, ions derived from natural sources (e.g., SO42-, Cl−) become more concentrated due to this reduced dilution.

3. Shift in Redox Conditions and Mobilization of Pollutants: A deeper groundwater table can modify redox conditions within the aquifer. The extended flow path and longer residence time can consume dissolved oxygen, shifting the environment from oxic to sub-oxic or even anoxic. While this study focused on major ions, such a shift could potentially mobilize other redox-sensitive contaminants like arsenic (As) or manganese (Mn) in the future, if they are present in the aquifer sediments (Fendorf et al., 2010). Furthermore, the concentration effect from reduced recharge can shift the saturation indices of minerals, potentially leading to the secondary precipitation of some phases (e.g., carbonates) while enhancing the dissolution of others (e.g., sulfates), thereby destabilizing the existing hydrochemical facies.

In summary, the decline in the groundwater level is not merely a hydraulic issue but a trigger for a cascade of geochemical feedbacks. It systemically enhances mineral dissolution, weakens contaminant dilution, and can potentially alter the biogeochemical environment, collectively leading to the observed deterioration in groundwater quality and the evolution towards more mineralized Ca-SO4 type waters.

3.3 Analysis of influencing factors

3.3.1 Changes in rainfall and evaporation

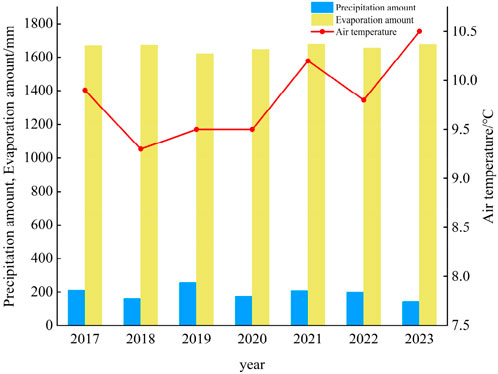

The rainfall in Jinchang City has obvious intra-annual variation and significant interannual fluctuation. In 2017–2023, the annual average rainfall was 193 mm, the maximum annual rainfall of 255 mm occurred in 2019, and the minimum annual rainfall of 143 mm occurred in 2023. The annual evaporation was 1,659.0 mm (about 9 times the rainfall) on average, with the highest value of 1,677.2 mm occurring in 2021 and the lowest value of 1,620.6 mm occurring in 2019 during this period (Figure 11). Although there were significant interannual variations in recent years, the long-term trends of rainfall and evaporation were relatively stable without significant directional changes. As mentioned above, the groundwater level in Jinchang City has been continuously decreasing in recent years, which suggests that the variations in rainfall and evaporation have little or no impact on the groundwater level fluctuations.

Figure 11. Variations in precipitation, evapotranspiration and air temperature in Jinchang City from 2017 to 2023.

3.3.2 Runoff change

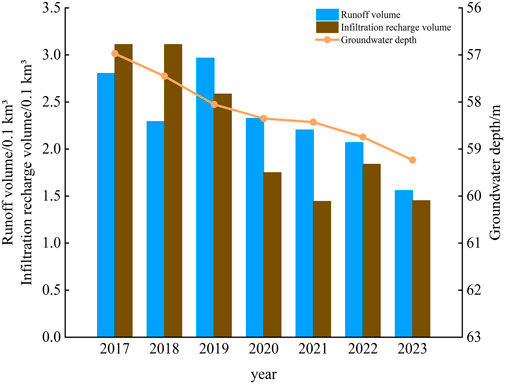

Figure 12 shows the relationship between the runoff, surface water infiltration recharge and groundwater depth in Jinchang city during 2017–2023. Runoff continued to decrease after 2020 due to the completion of the upstream Hanjaxia Dam in 2020, which greatly intercepted the surface water from the upper reach to the lower reach. The sharp reduction in runoff resulted in reduced surface water infiltration recharge, leading to a rising groundwater depth in the whole study area.

Figure 12. Comparative analysis of runoff, surface water infiltration recharge, and groundwater depth in Jinchang City from 2017 to 2023.

3.3.3 Groundwater exploitation change

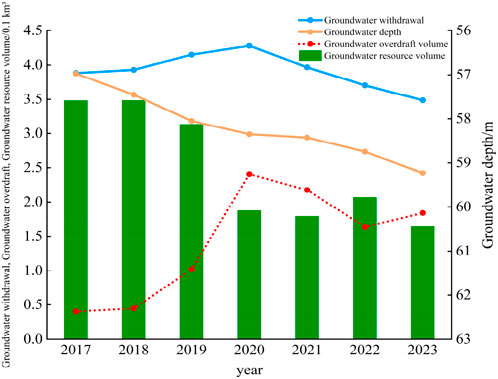

Before the 1970s, the main water source for Jinchang City was surface water. With the rapid development of agriculture, large-scale exploitation of groundwater began to fill the increasing gap between water supply and demand. Total groundwater extraction has consistently exceeded renewable recharge, resulting in a long-term negative groundwater balance and sustained depletion of regional aquifer resources. To quantify this imbalance, we calculated the annual groundwater overdraft, defined as the difference between the annual actual extraction volume and the annual renewable groundwater resources. The multi-year average renewable groundwater resources of Jinchang is 250 million m3. As shown in Figure 13, from 2017 to 2023, the actual extraction volume continuously exceeded this threshold, resulting in consecutive years of overdraft. In 2017, the overdraft reached 40 million m3, with an overdraft rate (overdraft/resource) of 12%. In 2023, the overdraft reached 175 million m3, with an overdraft rate (overdraft/resource) of 109%. Between 2017 and 2023, the agricultural irrigation area increased by 11.3%, and so did the corresponding water demand. Although there was stricter government control on agricultural water use after 2020, the greatly reduced surface water recharge caused by the construction of upstream dams further exacerbated the shortage of groundwater resources, maintaining the increasing trend of overdraft. The temporal dynamics of the groundwater overdraft and the groundwater depth show a high degree of synchronicity (Figure 13), providing preliminary evidence of a direct causal relationship.

Figure 13. Comparative analysis of groundwater abstraction, renewable resources, overdraft, and groundwater depth in Jinchang City from 2017 to 2023.

3.4 Analysis of contribution rate of influencing factors based on random forest algorithm

The “randomForest” package in the R software was used to build a random forest model in this study, The random forest model was trained on a panel dataset constructed from the 13 monitoring wells over the 84-month period (2017–2023). This resulted in a total of 1,092 theoretical data points (13 wells × 84 months). For each well and each month, the target variable was the groundwater depth, and the predictor variables included the corresponding monthly values (or annual aggregates where applicable) of groundwater extraction, surface runoff, precipitation, and evaporation. This structure allowed the model to learn from both the spatial variability across the wells and the temporal dynamics over the 7-year study period. The hyperparameter tuning was applied to obtain the feature importance scores of over-extraction, runoff, evaporation, and precipitation factors on the variation of the groundwater depth in Jinchang City from 2017 to 2023. The results show that groundwater over-extraction had the greatest impact on the groundwater table decline during the study period, with a feature importance index of 1.2, followed by runoff (index of 0.67), as shown in Figure 14. Despite the large interannual variability in precipitation and evaporation, their overall stable temporal trends led to minor effects on the changes in groundwater level.

The Random Forest model applied in this study also has certain limitations and uncertainties: First, its performance depends on the completeness of input variables—although we incorporated core influencing factors of groundwater level variation, including groundwater over-extraction, runoff, precipitation, and evaporation, unmonitored variables such as spatial heterogeneity of soil texture and local geological fractures in the study area may introduce some uncertainties into the model results, as these factors can indirectly affect groundwater recharge, runoff, and storage processes but were not quantified due to data availability constraints. Second, in the arid hydrological context of Jinchang City, extreme events (e.g., rare heavy rainfall that exceeds the range of historical precipitation data, or sudden large-scale adjustments in agricultural irrigation intensity due to policy changes or extreme droughts) may temporarily reduce the model’s prediction accuracy, since the model is trained on historical monitoring data within a specific variability range and lacks sufficient samples to capture the impacts of such abnormal events.

Furthermore, while the random forest model quantified the relatively minor long-term influence of precipitation and evaporation compared to anthropogenic factors and runoff reduction, it is important to acknowledge their potential role in short-term groundwater dynamics. The high interannual variability of precipitation, as observed in the data (e.g., 255 mm in 2019 vs. 143 mm in 2023), could lead to transient periods of groundwater level recovery during anomalously wet years or exacerbate the rate of decline during prolonged droughts, despite the absence of a significant long-term trend. Similarly, periods of extremely high evaporation might intensify water loss, particularly in shallow aquifer zones. These short-term fluctuations, although subordinate to the dominant drivers identified, contribute to the interannual variability of the groundwater system and should be considered in operational water resource management.

4 Conclusions and recommendations

This study integrated hydrochemical analysis, long-term groundwater level monitoring, and machine learning modeling to systematically investigate the groundwater hydrochemical characteristics, dynamic evolution, and driving mechanisms in the arid inland city of Jinchang. The main conclusions and scientific contributions are summarized as follows: (1) The groundwater in Jinchang is slightly alkaline, with high total hardness (avg. 569.62 mg/L) and total dissolved solids (avg. 905.92 mg/L). The dominant hydrochemical type is Ca-SO4, accounting for 69% of samples. The chemical composition is primarily controlled by rock weathering, especially silicate and carbonate dissolution, with minor contributions from evaporites. Notably, elevated concentrations of SO42- and NO3− exceed national standards, indicating significant influence from anthropogenic activities such as agricultural fertilization and intensive irrigation. (2) From 2017 to 2023, the groundwater level in Jinchang declined continuously by 2.26 m, at an average rate of 0.38 m/year. The Random Forest model effectively quantified the relative importance of influencing factors, revealing that groundwater over-exploitation (importance index = 1.2) and reduced surface runoff (0.67) were the dominant drivers. In contrast, precipitation and evaporation showed limited long-term impact due to their stable trends, despite high interannual variability. (3) The sustained decline in groundwater level has triggered a series of hydrogeochemical feedbacks: prolonged residence times enhance water-rock interactions, leading to increased ion concentrations; reduced recharge weakens the dilution capacity, exacerbating the accumulation of pollutants such as nitrate; and potential shifts in redox conditions may mobilize other contaminants in the future. These processes collectively contribute to the deterioration of groundwater quality and the instability of hydrochemical facies.

This research provides a novel integration of long-term dynamic data, hydrochemical tracing, and machine learning to quantify the drivers and mechanisms of groundwater evolution in a typical arid city. The methodology and findings offer a replicable framework for similar regions facing groundwater depletion. Practically, the results support targeted management strategies, including strict control of over-exploitation in central agricultural zones, optimization of upstream water allocation to mitigate runoff reduction, and promotion of water-saving irrigation technologies. For local communities, the study underscores the urgency of sustainable groundwater use and provides a scientific basis for public awareness and policy-making.

5 Future perspectives

Against the background of global climate change and intensified human activities, Jinchang City’s groundwater system—highly dependent on Qilian Mountain snowmelt and limited precipitation—will face long-term challenges. Combining recent research findings, this section discusses key future trends and research directions to support sustainable water resource management:

1. The impact of climate vegetation on groundwater recharge: Two core processes will reshape groundwater recharge: Firstly, Mohammed et al., (2019) predict a significant decrease in snowmelt in the Northern Hemisphere, which will reduce surface runoff (the main source of recharge for the Jinchang Quaternary aquifer) and exacerbate the recharge and exploitation gap. Secondly, global greening (Zan et al., 2024) will promote vegetation evapotranspiration and reduce the proportion of precipitation/runoff infiltrating underground. This “double squeeze” may accelerate the decline of groundwater levels beyond the current 0.38 meters per year, especially in the central regions where mining is concentrated.

2. Uncertainties from Precipitation and Human Adaptation: future precipitation (Tokarska et al., 2020) may bring more extreme events, but there will not be significant annual growth - short-term supply pulses cannot offset long-term scarcity and may exacerbate agricultural non-point source pollution. At the same time, local measures such as irrigation control after 2020 may be affected by upstream dams (such as Hanjiaxia Dam) and reduced snowmelt. As pointed out by Immerzeel et al. (2010), arid basins in Asia are facing the problem of slow growth in water resource availability, which means that 40% of Jinchang’s groundwater overexploitation cannot rely on the expansion of natural resources.

3. Key Future Research: Subsequent studies should focus on: 1. Coupling snowmelt-vegetation-groundwater models to quantify recharge changes; 2. Simulating groundwater responses under scenarios (e.g., “snowmelt reduction + water-saving irrigation”) to define sustainable extraction thresholds; 3. Employing more frequent sampling, isotope tracing, and monitoring of hydrochemical-ecological feedbacks to better capture temporal variations and pollutant pathways, thereby helping to balance water use and conservation.

In summary, proactive adaptation (optimizing upstream water allocation, promoting efficient irrigation) is essential to mitigate depletion, requiring ongoing research to reduce climate-hydrology uncertainties.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JS: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. SL: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. QG: Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. YJ: Data curation, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Development Project Fund of Key Laboratory of Groundwater Engineering and Geothermal Resources of Gansu Province (Grant No. 2024PT02); the Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Groundwater Engineering and Geothermal Resources of Gansu Province (Grant No. 202409) and the Study on the Coordinated Development of Water Resources, Economic Development and Ecological Environment in Jinchang City (Grant No. 25GSLK087) by the Water Conservancy Department of Gansu Province.

Acknowledgments

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank all the participants who devoted their free time to participate in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-Mashreki, M. H., Eid, M. H., Saeed, O., Székács, A., Szűcs, P., Gad, M., et al. (2023). Integration of geochemical modeling, multivariate analysis, and irrigation indices for assessing groundwater quality in the Al-Jawf basin, Yemen. Water 15 (8), 1496. doi:10.3390/w15081496

Breiman, L. (1996). Bagging predictors machine learning. Mach. Learn. 24, 0885–6125. doi:10.1023/A:1018054314350

Chang, G., Liu, H., Yin, Z., Wang, J., Li, K., and Gao, T. (2023). Agricultural production can be a carbon sink: a case study of jinchang city. Sustainability 15, 12872. doi:10.3390/su151712872

Chen, J., Wang, F., Xia, X., and Zhang, L. (2002). Major element chemistry of the changjiang (yangtze river). Chem. Geol. 187, 231–255. doi:10.1016/s0009-2541(02)00032-3

El Osta, M., Masoud, M., Alqarawy, A., Elsayed, S., and Gad, M. (2022). Groundwater suitability for drinking and irrigation using water quality indices and multivariate modeling in makkah Al-Mukarramah province, Saudi Arabia. Water 14 (3), 483. doi:10.3390/w14030483

Fendorf, S., Michael, H. A., and Van Geen, A. (2010). Spatial and temporal variations of groundwater arsenic in south and southeast Asia. Science 328 (5982), 1123–1127. doi:10.1126/science.1172974

Gad, M., and El Osta, M. (2020). Geochemical controlling mechanisms and quality of the groundwater resources in El fayoum depression, Egypt. Arabian J. Geosciences 13, 861. doi:10.1007/s12517-020-05882-x

Gad, M., Gaagai, A., Eid, M. H., Szűcs, P., Hussein, H., Elsherbiny, O., et al. (2023). Groundwater quality and health risk assessment using indexing approaches, multivariate statistical analysis, artificial neural networks, and GIS techniques in El kharga oasis, Egypt. Water 15 (6), 1216. doi:10.3390/w15061216

Gibbs, R. J. (1970). Mechanisms controlling world water chemistry. Science 170, 1088–1090. doi:10.1126/science.170.3962.1088

Goldberg, S. (2006). Geochemistry, groundwater and pollution. Vadose Zone J. 5 (1), 510. doi:10.2136/vzj2005.1110br

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., and Friedman, J. (2009). The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction. Springer.

Hfaiedh, E., Gaagai, A., Moussa, A. B., Petitta, M., Mlayah, A., Elsayed, S., et al. (2025a). An innovative ML and GIS-integrated approach for predicting irrigation water quality in coastal aquifers. Earth Syst. Environ. doi:10.1007/s41748-025-00851-4

Hfaiedh, E., Gaagai, A., Petitta, M., Moussa, A. B., Mlayah, A., Eid, M. H., et al. (2025b). Hydrogeochemical characterization and water quality evaluation associated with toxic elements using indexing approaches, multivariate analysis, and artificial neural networks in morang, Tunisia. Environ Earth Sci. 84, 361. doi:10.1007/s12665-025-12165-9

Immerzeel, W. W., Ludovicus, P. H., and Marc, F. P. (2010). Climate change will affect the asian water towers. Sci. 328, 1382–1385. doi:10.1126/science.1183188

Jasechko, S., Perrone, D., Befus, K. M., Cardenas, M. B., Ferguson, G., Gleeson, T., et al. (2017). Global aquifers dominated by fossil groundwaters but Wells vulnerable to modern contamination. Nat. Geosci. 10 (6), 425–429. doi:10.1038/ngeo2943

Jiang, Y., Lin, L., Chen, L., Ni, H., Ge, W., Cheng, H., et al. (2018). An overview of the resources and environment conditions and major geological problems in the yangtze River economic zone, China. China Geol. 1 (3), 434–448. doi:10.31035/cg2018040

Langguth, H. R. (1966). “Groundwater Characteristics in Bereiech Des Velberter Sattles,” in North rhine-westphalia: ministry of agricultural and land management research düsseldorf, 127.

Li, P., Wu, J., and Qian, H. (2020). Hydrochemical appraisal of groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation purposes and the major influencing factors: a case study in and around hua county, China. Arabian J. Geosciences 13 (19), 1–16. doi:10.1007/s12517-015-2059-1

Liu, H., Zhong, H., and Gu, Y. (2001). Water resources development and oasis evolution in inland river basin of arid zone of northwest China - a case study: Minqin basin of Shiyang River. Hohai Univ. 12 (3), 378–384.

Ma, J., Pan, F., Chen, L., Edmunds, W. M., Ding, Z., He, J., et al. (2010). Isotopic and geochemical evidence of recharge sources and water quality in the Quaternary aquifer beneath jinchang city, NW China. Appl. Geochem. 25 (7), 996–1007. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2010.04.006

Min, L., Nie, Z., Cao, L., Wang, L., Lu, H., Wang, Z., et al. (2021). Comprehensive evaluation on the ecological function of groundwater in the Shiyang River watershed. J. Groundw. Sci. Eng. 9 (4), 362–340. doi:10.19637/j.cnki.2305-7068.2021.04.006

Min, L., Nie, Z., Liu, X., Wang, L., and Cao, L. (2024). Change in groundwater table depth caused by natural change and human activities during the past 40 years in the Shiyang River Basin, northwest China. Sci. total Environ. 906, 167722. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167722

Mohammed, A. A., Pavlovskii, L., Cey, E. E., and Hayashi, M. (2019). Effects of preferential flow on snowmelt partitioning and groundwater recharge in frozen soils. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 23. doi:10.5194/hess-23-5017-2019

Naghibi, S., Ahmadi, K., and Daneshi, A. (2017). Application of support vector machine, random forest, and genetic algorithm optimized random forest models in groundwater potential mapping. Water Resour. Manag. 31 (9), 2761–2775. doi:10.1007/s11269-017-1660-3

Piper, A. M. (1944). A graphic procedure in the geochemical interpretation of water-analyses. Trans-Am. Geophys. Union 25 (6), 914–923. doi:10.1029/TR025i006p00914

Scanlon, B. R., Reedy, R. C., Stonestrom, D. A., Prudic, D. E., and Dennehy, K. F. (2005). Impact of land use and land cover change on groundwater recharge and quality in the southwestern US. Glob. Chang. Biol. 11, 1577–1593. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01026.x

Singh, C. K., Kumar, A., Shashtri, S., Kumar, A., Kumar, P., and Mallick, J. (2021). Multivariate statistical analysis and geochemical modeling for geochemical assessment of groundwater of Delhi, India. J. Geochem. Explor. 227, 106795. doi:10.1016/j.gexplo.2017.01.001

Stallard, R. F., and Edmond, J. M. (1983). Geochemistry of the Amazon 2. The influence of geology and weathering environment on the dissolved load. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 88 (14), 9671–9688. doi:10.1029/jc088ic14p09671

Thomas, J., Joseph, S., and Thrivikramji, K. P. (2015). Hydrochemical variations of a tropical Mountain river system in a rain shadow region of the southern Western ghats, Kerala, India. Appl. Geochem. 63, 456–471. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2015.03.018

Tyralis, H., Papacharalampous, G., and Langousis, A. (2019). A brief review of random forests for water scientists and practitioners and their recent history in water resources. Water 11 (5), 910. doi:10.3390/w11050910

Umar, R., and Absar, A. (2003). Chemical characteristics of groundwater in parts of the gambhir river basin, bharatpur district, Rajasthan, India. Environ. Geol. 44 (5), 535–544. doi:10.1007/s00254-003-0789-y

Wang, L., Yue, L., Tang, Z., and Zhang, X. (2014). Influence of climate change and agricultural development on groundwater level in Shiyang River Basin. Nongye Jixie Xuebao Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 45 (1), 121–128. doi:10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2014.01.020

Wen, J., He, Y., Yang, L., Wan, P., Gu, Z., and Wang, Y. (2025). A two-step downscaling model for modis land surface temperature based on random forests. Atmosphere 16 (4), 424. doi:10.3390/atmos16040424

Xu, L., Cui, X., Bian, J., Wang, Y., and Wu, J. (2024). Dynamic change and driving response of shallow groundwater level based on random forest in southwest songnen plain. J. Hydrology Regional Stud. 53, 101800. doi:10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.101800

Yang, L., Zhu, G., Shi, P., Li, J., Liu, Y., Tong, H., et al. (2018). Spatiotemporal characteristics of hydrochemistry in Asian arid inland basin-a case study of shiyang river Basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 25 (3), 2293–2302. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-0504-2

Ye, H., Ma, Y., and Dong, L. (2011). Land ecological security assessment for Bai autonomous prefecture of dali based using PSR Model—With data in 2009 as case. Energy Procedia 5, 2172–2177. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2011.03.375

Zhang, Z., Jia, W., Zhu, G., Shi, Y., Yang, L., Xiong, H., et al. (2021). Hydrochemical characteristics and ion sources of river water in the upstream of the Shiyang River, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 80 (18), 614. doi:10.1007/s12665-021-09793-2

Zhang, H., Gao, W., Shi, M., Hou, Z., Yang, R., and Gao, Z. (2025). Evolution of groundwater hydrochemical characteristics and origin analysis in Yimeng revolutionary old district. Water Resourses 52 (2), 332–341. doi:10.1134/s0097807824605065

Keywords: arid zone groundwater process, hydrochemical evolution mechanism, groundwater depth, influencing factors, machine learning application

Citation: Shang J, Liu S, Guo Q and Jiang Y (2025) Research on the hydrochemical characteristics of groundwater and dynamic changes in water level depth in Jinchang City. Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1725591. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1725591

Received: 15 October 2025; Accepted: 13 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Mamadou Adama Sarr, Gaston Berger University, SenegalReviewed by:

Yuanfang Chai, Zhejiang Normal University, ChinaMohamed Gad, University of Sadat City, Egypt

Copyright © 2025 Shang, Liu, Guo and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiaona Guo, Z3VvcWlhb25hMjAxMEBoaHUuZWR1LmNu

Jinyu Shang

Jinyu Shang Shengwen Liu

Shengwen Liu Qiaona Guo

Qiaona Guo Yajun Jiang

Yajun Jiang