- 1Jilin Economic Research Center, Jilin University of Finance and Economics, Changchun, China

- 2School of Finance, Jilin University of Finance and Economics, Changchun, China

- 3College of Economics and Management, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China

This study takes the implementation of the “Guiding Opinions on Launching Pilot Programs for Mandatory green Insurance” in 2013 as a quasi-natural experiment. Based on the panel data of A-share listed companies from 2008 to 2023, it systematically examines the impact of the green insurance policy on the performance of heavy-polluting enterprises by using the difference-in-differences (DID) method. The research findings show that the green insurance policy significantly improves the performance level of heavy-polluting enterprises. Mechanism tests indicate that the green insurance promotes the improvement of corporate performance through two paths: incentivizing enterprises’ technological innovation and enhancing their short-term debt financing capacity. Further heterogeneity analysis reveals that the policy has a more prominent role in improving the performance of enterprises with lower environmental investment levels, non-state-owned nature, and less financing constraints. The test of moderating effects finds that the board size negatively moderates the promoting effect of the green insurance on corporate performance, while the proportion of independent directors exerts a positive moderating effect. This study provides theoretical support and empirical evidence for the optimal design of the green insurance policy and the green and low-carbon transformation of heavy-polluting enterprises, and has important implications for improving the green insurance system and serving the high-quality development of the economy.

1 Introduction

Green development is the crucial feature of high-quality development and the essential pathway to achieving the “Dual Carbon” goals. While China’s rapid economic growth and long-term social stability have laid a relatively solid material foundation, they have also been accompanied by severe challenges of resource consumption and environmental pollution, accumulating numerous deep-seated ecological and environmental issues (Yuan and Liu, 2024). Enterprises, as primary participants in economic activities and major resource consumers, directly impact regional environmental quality and public safety through their environmental behaviors, particularly the operational activities of heavy-polluting enterprises (Yu et al., 2025).

Environmental pollution exhibits typical externality characteristics, making it difficult to resolve effectively through market mechanisms alone. Consequently, government regulation plays a crucial role in environmental governance, essentially internalizing external costs through institutional design to correct resource misallocation (Fan et al., 2022; Wang L.-J. et al., 2024). Green insurance, which covers enterprises’ liability for environmental damage to third parties, serves the dual functions of risk transfer and social management (Lu et al., 2024). Its implementation logic aligns closely with the concept of a “Pigouvian tax,” representing a significant market-based instrument for internalizing environmental externalities (Yang et al., 2020; Zhang and Wei, 2024). Furthermore, according to the “Porter Hypothesis,” environmental regulation can stimulate technological innovation and optimize resource allocation, thereby enhancing corporate economic performance (Porter and van der Linde, 1995; Guo et al., 2023; Liang et al., 2023; Wang Y. et al., 2024). As a market-based regulatory tool incorporating both incentives and constraints, the implementation effects and transmission mechanisms of green insurance have increasingly become a focus of academic research.

As an important component of green finance, green insurance has been addressed in existing studies that explore the policy effects of green finance from multiple dimensions, encompassing corporate innovation (Wang Y. et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2025), green transformation (Zhang S. et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025), investment efficiency (Wang and Zhao, 2022), ESG performance (Xie, 2024), financing behavior (Zhang, 2023; Zhang G. et al., 2023), energy consumption structure (Zhang Z. et al., 2023), and environmental information disclosure (Fan et al., 2025; He et al., 2025). However, performance is the primary objective for enterprise survival and development, and the ultimate reflection of their response to environmental regulation. Whether enterprises can achieve stable or improved performance while effectively managing environmental risks through purchasing green insurance is key to determining their willingness to adopt it, and constitutes the micro-foundation for the successful promotion of green insurance policies. Nevertheless, existing literature predominantly focuses on the impact of green insurance on specific corporate behaviors or aspects of performance, lacking systematic investigation into its direct effect on comprehensive corporate performance and a comprehensive analysis of the underlying logic. Moreover, prevalent empirical methods often rely on fixed-effects models, failing to fully exploit the exogenous nature of policy shocks.

In practice, China’s green insurance policy has evolved from regional exploration to national pilots, transitioning from active guidance to mandatory requirements, and now towards high-quality advancement. As early as 1991, China initiated green insurance pilots in cities like Dalian and Shenyang. However, due to factors like low claim ratios and limited coverage, the scale of green insurance gradually shrank until it exited the market. Building on earlier regional experience, China formally launched a national green insurance pilot program in December 2007, with the core objective of guiding enterprises in key industries and regions to voluntarily purchase green insurance. After 5 years of piloting, in 2013, the former Ministry of Environmental Protection and the former China Insurance Regulatory Commission jointly issued the “Guiding Opinions on Launching Pilot Programs for Mandatory green Insurance”, which requires launching pilot projects of green insurance in high environmental risk industries. The document specifies the “mandatory insurance” requirements for specific high-risk enterprises, marking a policy shift from “guidance” to “constraint”. Subsequently, the government issued a series of documents to gradually refine the institutional framework. In 2024, China further proposed “encouraging localities to establish and improve green insurance systems” and “enhancing environmental risk coverage levels in enterprise production, storage, transportation, and other processes,” emphasizing the integration of green insurance with enterprise-wide environmental risk management and signaling an entry into a stage of high-quality advancement.

Despite this, green insurance still faces the practical dilemma of “weak supply and demand.” Shenzhen, a pioneer in comprehensive reform pilots for the green insurance system, witnessed a significant increase in its average annual green insurance coverage to RMB 2.801 billion from 2020 to 2024, a 4.2-fold growth compared to 2019, with an average annual premium of RMB 19.24 million. However, despite the substantial growth in coverage, the premium volume still accounts for less than 0.05% of the property insurance market share, and the number of insured enterprises represents only about 0.5% of the total industrial enterprises. The key to resolving this dilemma lies in enhancing corporate willingness to purchase insurance, which largely depends on whether enterprises can achieve stable or improved performance while controlling environmental risks. However, existing research has inadequately addressed this practical challenge. Facing the “weak supply and demand” predicament, current studies have not sufficiently analyzed how the policy can stimulate insurance uptake by improving corporate performance–a core concern for enterprises–resulting in limited theoretical guidance for practice.

Based on this, this paper utilizes the 2013 mandatory pilot policy for high environmental risk industries as a quasi-natural experiment. Employing a Difference-in-Differences (DID) model with data from A-share listed companies from 2008 to 2023, it systematically examines the impact of green insurance on the performance of heavy-polluting enterprises and its underlying mechanisms. This policy’s mandatory and industry-specific nature, rather than universal coverage, allows for constructing plausible treatment and control groups. The marginal contributions of this paper are: First, focusing on the core indicator of corporate performance, it provides direct evidence for evaluating the economic consequences of green insurance policies, supplementing the insufficient discussion on this aspect in existing literature. Second, it reveals the mediating pathways through which green insurance affects corporate performance from the dimensions of technological innovation and financing capacity, enriching the theoretical chain of “environmental regulation–corporate behavior–economic performance”. Third, it conducts heterogeneity analyses considering factors such as corporate environmental investment, ownership nature, and financing constraints, offering an empirical basis for precisely optimizing green insurance policies and resolving the “weak supply and demand” dilemma. Fourth, it further identifies the moderating roles of board size and the proportion of independent directors in the relationship between green insurance and corporate performance from a corporate governance perspective, providing theoretical references for improving the synergy between corporate governance and insurance mechanisms.

2 Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

Against the strategic backdrop of the “Dual Carbon” goals and green development, the traditional industrial system characterized by heavy pollution and high emissions is increasingly incompatible with the requirements of China’s high-quality economic development, necessitating a transition towards a green economic development model with lighter pollution and lower emissions. Green financial instruments, represented by green insurance, are considered vital means to address the pollution risks of heavy-polluting enterprises and enhance their sustainable development capacity. Purchasing green insurance not only helps heavy-polluting enterprises cope with potential environmental liabilities but can also influence their operational performance through multiple pathways.

2.1 Direct impact of green insurance on the performance of heavy-polluting enterprises

As a market-based and socialized environmental risk management tool, the core function of green insurance is to transform enterprises’ uncertain, potentially massive environmental risks into certain, manageable premium costs through insurance contracts, thereby internalizing environmental external costs. For heavy-polluting enterprises, purchasing green insurance is not merely a response to regulatory compliance but also a strategic risk management behavior that may directly enhance corporate performance through two theoretical pathways: the loss compensation mechanism and the risk supervision mechanism.

On one hand, green insurance acts as a “financial stabilizer” through the loss compensation mechanism. Environmental pollution incidents are often characterized by sudden onset, severe consequences, and high remediation costs (Zhang X. et al., 2024). Once an incident occurs, enterprises may face substantial compensation payouts, administrative penalties, or even production suspension, severely impacting their operational continuity and financial stability. Green insurance converts the uncertain, potentially enormous risk of environmental liability for heavy polluters into a certain and limited insurance premium expenditure, thereby smoothing corporate financial volatility. When an accident occurs, timely payouts from insurers cover part or all of the environmental remediation and liability costs, effectively alleviating corporate cash flow pressure and avoiding asset impairment or financial distress triggered by sudden environmental events (Bucheli et al., 2023). From a financial management perspective, this mechanism helps improve the stability of asset returns for heavy-polluting enterprises, reduces profit volatility, enhances investor and creditor confidence, and consequently positively impacts market value and financing capacity (Yu et al., 2021). Although purchasing green insurance entails additional cost outlays, as a government-supported green insurance category, many regions offer premium subsidy policies. For instance, several cities in Guangdong Province provide subsidies covering 30% of the premium, while Jiangsu Province offers subsidies up to 40% of the actual premium paid. These subsidy policies reduce the financial burden on enterprises, mitigating the financial pressure associated with insurance purchase.

On the other hand, green insurance introduces external governance forces through the supervision and service mechanism, promoting improved environmental management standards. To control underwriting risks, insurers typically conduct environmental risk assessments, hazard identification, and provide guidance on loss prevention for enterprises. This external supervision imposes hard constraints on corporate environmental management behaviors. Taking Shenzhen as an example, in 2021, insurance institutions in Shenzhen were required to allocate no less than 25% of the annual green insurance premium income to provide risk supervision services for insured enterprises, including environmental risk early warning, assessment, hazard screening, and environmental protection training. From 2021 to 2024, insurers in Shenzhen spent nearly RMB 20 million on environmental risk prevention and control services, achieving 100% coverage in environmental risk hazard screenings and issuing over 1,000 risk assessment rectification suggestions, effectively reducing the probability of environmental pollution incidents. This third-party supervision led by insurers not only compensates for deficiencies in corporate environmental management capabilities but also incentivizes enterprises through differentiated premium rate designs to improve production processes and enhance resource utilization efficiency, thereby optimizing operational performance (Wu et al., 2022). Accordingly, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Green insurance enhances the stability of asset returns for heavy-polluting enterprises by functioning as a “stabilizer” through the loss compensation mechanism, reducing operational volatility and asset impairment risk.

Hypothesis 2. Green insurance promotes operational efficiency in heavy-polluting enterprises by exerting a “governance enhancement” effect through the risk supervision mechanism, incentivizing improvements in environmental risk management and optimization of production processes.

2.2 Mediating mechanisms of green insurance’s impact on heavy-polluting enterprise performance

The performance-enhancing effect of green insurance may not only manifest directly through risk protection and governance enhancement but also indirectly through mediating pathways such as alleviating financing constraints and incentivizing technological innovation.

First, green insurance can enhance corporate financing capacity. Heavy-polluting enterprises often face credit rationing and higher financing costs from financial institutions due to their elevated environmental risks (Zhou et al., 2021). A green insurance policy, serving as a risk mitigation tool, can send a positive signal to banks about the enterprise’s strong environmental risk management capabilities, reducing information asymmetry and thereby improving financing conditions (Liu et al., 2023). As early as 2016, China explicitly incorporated green insurance into the green financial system. Green insurance policies possess certain credit enhancement and collateralization functions, facilitating access to more favorable credit resources and providing funding support for environmental upgrades and technological advancements. Simultaneously, insurance funds, as typical “patient capital,” can offer stable, long-term financial support for the green transformation projects of heavy-polluting enterprises. In 2023 alone, the total green investment by the five major listed A-share insurers reached RMB 906.664 billion, primarily supporting green transformation projects in enterprises like those in photovoltaic and wind power sectors, through green bond investments, asset management product investments, etc., alleviating long-term funding gaps for corporate green transformation.

Second, green insurance can stimulate corporate green technological innovation. According to the “Porter Hypothesis,” appropriate environmental regulation can spur technological innovation (Porter and van der Linde, 1995). Regulatory measures can compel or incentivize enterprises to increase R&D investment to enhance pollution control capabilities and product technological content, promoting green technological innovation and generating an “innovation offset” effect (Shi and Zhou, 2024), ultimately reflected in operational cost control, optimized production resource allocation, and improved business performance (Yu et al., 2023; Chen and Xie, 2024). As a typical environmental regulation tool, the introduction of green insurance creates favorable conditions for heavy-polluting enterprises to implement green technological innovation (Wang et al., 2017). On one hand, the intensified and normalized pressure for ecological and environmental governance–for instance, Beijing alone investigated nearly 22,300 cases of ecological environmental violations and imposed administrative penalties of RMB 147 million in 2021–clearly signals compliance requirements to the market, effectively compelling heavy-polluting enterprises to abandon short-term opportunistic mindsets of “pollute first, clean up later,” and instead view green technology R&D as a long-term investment to reduce environmental risks and ensure sustainable operation. On the other hand, insurers, by setting differentiated premiums linked to environmental performance, pressure enterprises to increase R&D investment and promote green technology upgrades. Concurrently, the risk assessments and rectification suggestions provided by insurers help enterprises identify technological shortcomings, guiding them towards cleaner production and efficient pollution control, thereby enhancing long-term performance through technological progress. Accordingly, this paper proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3. Green insurance enhances enterprises’ financing capacity, alleviates their financing constraints, and thereby improves corporate performance.

Hypothesis 4. Green insurance enhances corporate performance by incentivizing green technological innovation, which optimizes production processes and pollution control efficiency.

2.3 Moderating role of corporate governance structure

Under the pressure of environmental liability, managers of heavy-polluting enterprises exhibit an increasingly evident tendency towards risk aversion (Reijnders, 2003). Green insurance serves as a managerial incentive tool. By purchasing green insurance, heavy-polluting enterprises can conduct ex-ante control and ex-post sharing of project-induced environmental risks, significantly reducing managers’ perception of project environmental risk, increasing their willingness to undertake risks, incentivizing them to make more efficient investment decisions, and consequently enhancing corporate operational performance. However, whether an enterprise purchases green insurance and the extent of its policy effects are influenced, to some degree, by its internal governance structure (Ning et al., 2023). The board of directors, as the core decision-making body, may moderate the relationship between green insurance and corporate performance through its size and independence. On one hand, while a larger board size can help expand the enterprise’s information resource network, it may also lead to longer decision-making chains, increased coordination costs, and reduced communication efficiency, potentially dampening the willingness to purchase green insurance, especially high-coverage policies, thereby weakening the policy’s implementation effect. On the other hand, independent directors, as crucial components of the internal supervision mechanism, possess strong professional expertise and objective standing, enabling them to better fulfill their advisory and monitoring roles vis-à-vis management. Existing research shows that independent directors can exert supervisory effects during corporate crises, enhancing firm value (Calderón et al., 2020). Further studies indicate that firms with a higher proportion of independent directors often have stronger monitoring mechanisms and transparency (Shaukat and Trojanowski, 2018), and are more responsive to national environmental regulations, optimizing resource allocation. Therefore, firms with a high proportion of independent directors tend to place greater emphasis on long-term risk governance and sustainable development, making them more likely to enhance environmental management capacity through green insurance purchase, thereby strengthening its positive impact on corporate performance. Accordingly, this paper proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5. Board size negatively moderates the relationship between green insurance and corporate performance.

Hypothesis 6. The proportion of independent directors positively moderates the relationship between green insurance and corporate performance.

3 Research design

3.1 Model specification

To examine the impact of the green insurance policy on enterprise performance, this paper regards the release of the “Guiding Opinions on Carrying out Pilot Work of Compulsory green Insurance” in 2013 as a quasi-natural experiment. The policy’s mandatory nature is not applicable to all enterprises but is implemented in an orderly manner by regions in accordance with policy requirements for specific heavily polluting and high environmental risk industries. This exogenous policy shock at the industry level provides a good identification condition for the application of the difference-in-differences method (DID) in this paper. The specific model is set as follows Equation 1:

In Equation 1, the subscripts i and t represent enterprises and years respectively, the dependent variable

3.2 Variable selection and measurement methods

3.2.1 Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this paper is corporate performance, measured by the annual return on assets (Roa) and return on equity (Roe) of the enterprises.

3.2.2 Core independent variable

The core independent variable in this paper is the dummy variable of the green insurance policy, specifically the interaction term Post × Treat. The policy shock point is set at 2013. For the division of the experimental group and the control group, this paper strictly follows the “Industry Classification Management List for Environmental Protection Verification of Listed enterprises” issued by the Ministry of Environmental Protection in 2008 and the “Guidelines for Environmental Information Disclosure of Listed enterprises” in 2010. Meanwhile, in accordance with the 2012 version of the Industry Classification issued by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), enterprises in the heavily polluting industries specified therein are classified into the experimental group, with the rest assigned to the control group. This classification method ensures the exogeneity and authority of the definition of the treatment variable, effectively avoiding the potential selection bias caused by grouping based on endogenous variables such as the pollution level of the enterprises themselves.

3.2.3 Control variables

Debt-to-asset ratio (Lev) represented by the proportion of total liabilities to total assets of the enterprise, controlling for the potential impact of corporate capital structure on profitability. Enterprise age (Age) represented by the natural logarithm of the current year minus the year of the enterprise’s listing, controlling for performance differences caused by the enterprise’s life cycle stage. Fixed asset ratio (Fix) represented by the proportion of net fixed assets to total assets of the enterprise, controlling for differences in corporate profit models resulting from capital intensity. Equity concentration (Top1) represented by the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder of the enterprise, controlling for the impact of ownership structure on corporate decision-making and performance. Management expense ratio (Mfe) represented by the ratio of management expenses to operating income, controlling for the influence of internal operational efficiency on corporate performance. Cash holding (Cash) is represented by the ratio of the sum of monetary funds and trading financial assets to total assets, controlling for the effect of liquidity levels on corporate investment and risk resistance capabilities. Capital intensity (Capital) represented by the ratio of total assets to operating income, controlling for the impact of asset utilization efficiency on corporate profit margins.

3.2.4 Mechanism variables

Previous literature research results show that the improvement of enterprise technological innovation level and financing ability can significantly enhance enterprise performance. Therefore, they are taken as mechanism variables for subsequent analysis. Of these, technological innovation (Tec) is measured by the logarithm of the number of patents obtained by the enterprise in the current year. As for investment and financing capacity (Ability), it is proxied by total asset turnover—an indicator whose increase signals improved operational efficiency and accelerated capital recovery, which in turn strengthens internal cash flow accumulation and boosts financial institutions’ credit confidence, thereby indirectly enhancing enterprises’ financing availability.

3.2.5 Moderating variables

Board size (Board) represented by the natural logarithm of the number of board members. Proportion of independent directors (Indep) represented by the ratio of independent directors to the total number of directors.

3.3 Data sources and descriptive statistics

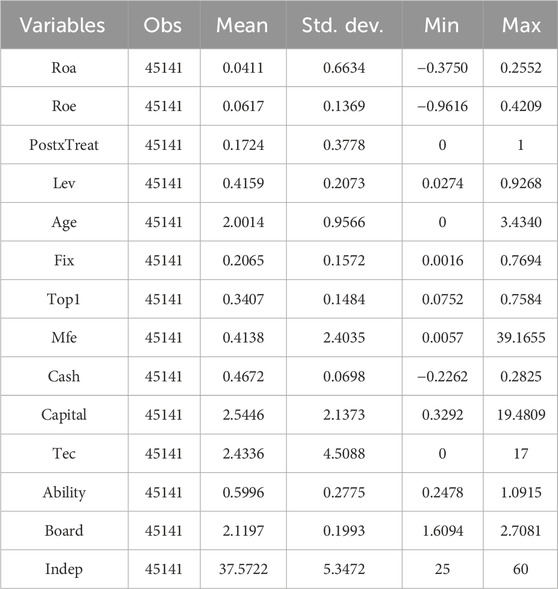

This paper selects A-share listed enterprises from 2008 to 2023 as the research sample. The initial data is sourced from the CSMAR database, with listed enterprises in the financial industry and those under special treatment by stock exchanges (including ST, *ST, and PT enterprises) excluded. At the same time, to avoid the interference of outliers on the estimation results, all continuous variables are trimmed by 2% at both ends. The descriptive statistics of the variables are shown in Table 1.

4 Empirical findings and analysis

4.1 Benchmark analysis

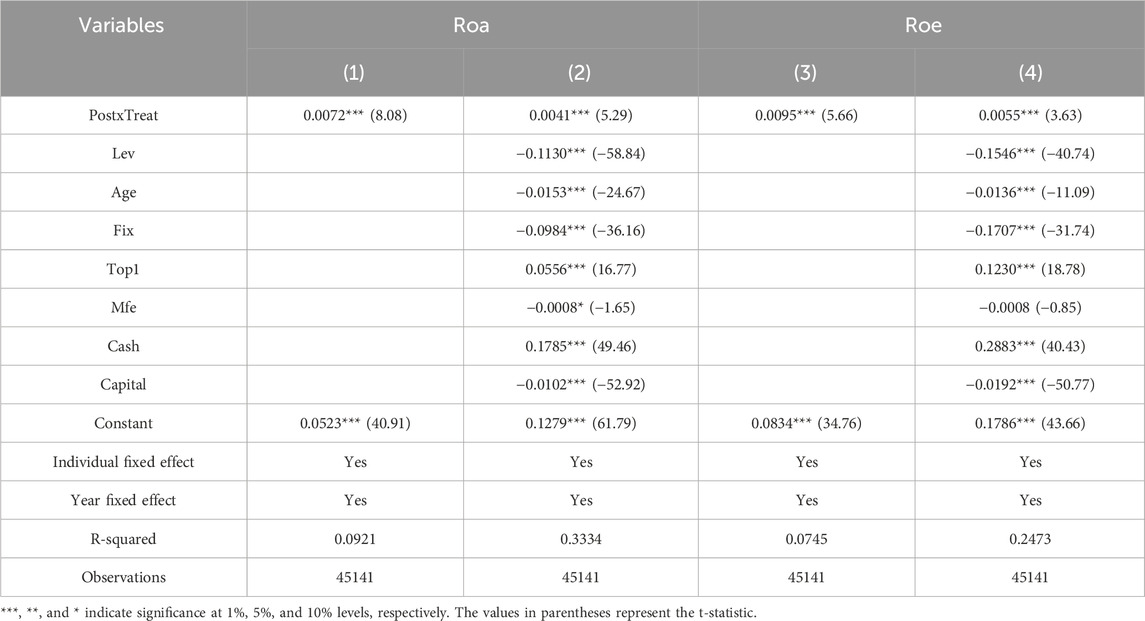

The benchmark regression results in Table 2 show that columns (1) and (3) present the regression results with fixed effects but without control variables. The results indicate that the regression coefficient of the green insurance policy dummy variable on Roa is 0.0072 and is positively significant at the 1% level, while the regression coefficient on Roe is 0.0095 and is positively significant at the 1% level. Columns (2) and (4) present regression results incorporating control variables and fixed effects. The results show that the dummy variable for green insurance policies has a regression coefficient of 0.0041 for Roa, which is positively significant at the 1% level, and a regression coefficient of 0.0055 for Roe, which is positively significant at the 1% level.

Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 proposed in this study are empirically difficult to completely disentangle. They inherently exhibit synergistic relevance in practice: loss compensation provides financial security for enterprises to address environmental risks, while risk regulation proactively reduces risk probability, forming a complementary logic of “protection and standardization”. The positive results from the benchmark regression essentially reflect the combined effect of these two paths. Theoretically, loss compensation alleviates enterprises’ risk concerns and lays the foundation for their acceptance of regulation. Meanwhile, regulation optimizes operational decisions and further improves compensation efficiency, with the two mutually supporting each other. Therefore, the empirical results have verified the inherent rationality of their synergistic effect, providing empirical support for the theoretical logic of green insurance’s dual functions. Based on this, Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 are confirmed.

4.2 Robustness tests

4.2.1 Parallel trends test

The benchmark conclusion in Table 2 relies on a critical underlying assumption: no significant performance differences existed between experimental and control group enterprises prior to policy implementation. This study employs an event study approach for parallel trends testing, with the model defined as follows Equation 2:

In Equation 2

Figure 1. Roa’s parallel trend test. The dashed lines perpendicular to the horizontal axis represent the 99% confidence intervals; “current” denotes the base period, namely 2013.

Figure 2. Roe’s parallel trend test. The dashed lines perpendicular to the horizontal axis represent the 99% confidence intervals; “current” denotes the base period, namely 2013.

4.2.2 PSM-DID

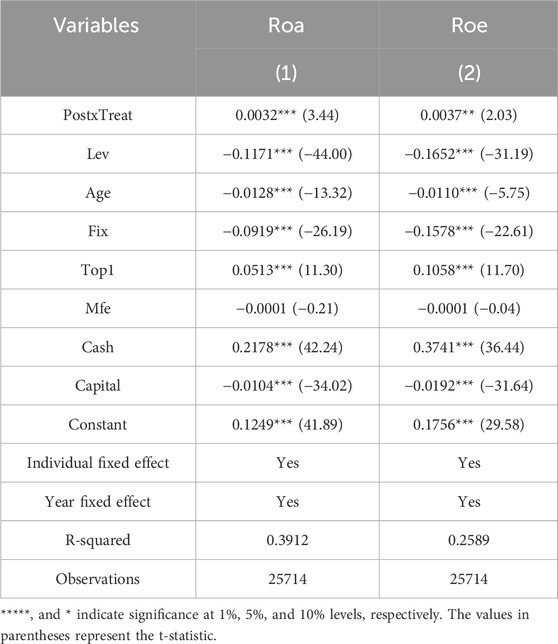

Benchmark regression may suffer from selection bias due to inherent differences between experimental and control group enterprises. To address this endogeneity issue, this study employs propensity score matching (PSM). The control variables from the benchmark regression are used as matching variables for 1:4 nearest-neighbor matching. The matched samples are then re-estimated using a double difference model. Table 3 shows that the estimated coefficient of the policy dummy variable remains significantly positive at the 1% and 5% significance levels, which further confirms that the benchmark findings remain robust after controlling for observable characteristics.

4.2.3 Excluding municipalities directly under central government

Considering that the four municipalities directly under the central government may differ significantly from other provinces due to their special development characteristics, potentially affecting empirical results. Therefore, we re-estimated the model after excluding enterprises located in these municipalities. The regression results in Table 4 show that the dummy variable for green insurance policy remains significantly positive at the 1% level for both Roa and Roe, validating the robustness of the benchmark regression.

4.2.4 Test for excluding interference from major environmental policies

The Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan issued and implemented by the State Council in 2013 is regarded as the most stringent environmental regulation in history. This policy may impact emissions from heavily polluting enterprises. To eliminate potential interference from this environmental policy on the benchmark conclusions of this study, we re-ran the regression after excluding the sample of enterprises located in the 57 high-target cities designated under the 2013 “Ten-Point Plan for Air Pollution Prevention and Control”. The regression results in Table 5 show that the dummy variable for green insurance policy remains significantly positive at the 1% level for both Roa and Roe, validating the robustness of the regression results.

4.2.5 Placebo test

To exclude potential interference from unobservable factors and further validate the robustness of the benchmark results, a placebo test was conducted. Specifically, enterprises were randomly selected from the sample to form a fictitious experimental group, and this process was repeated 1000 times to generate a distribution of estimated coefficients. If the estimated results after random sampling indicated significant interaction terms, it would suggest identification bias in the model specification. The results are presented in Figures 3, 4. The figures reveal that the mean of the regression coefficients approaches zero, with the benchmark regression coefficient clearly appearing as an outlier. This outcome aligns with the falsification logic of the placebo test, thereby confirming the reliability of the benchmark regression conclusions.

5 Further analysis

5.1 Heterogeneity analysis

5.1.1 Heterogeneity in environmental investment

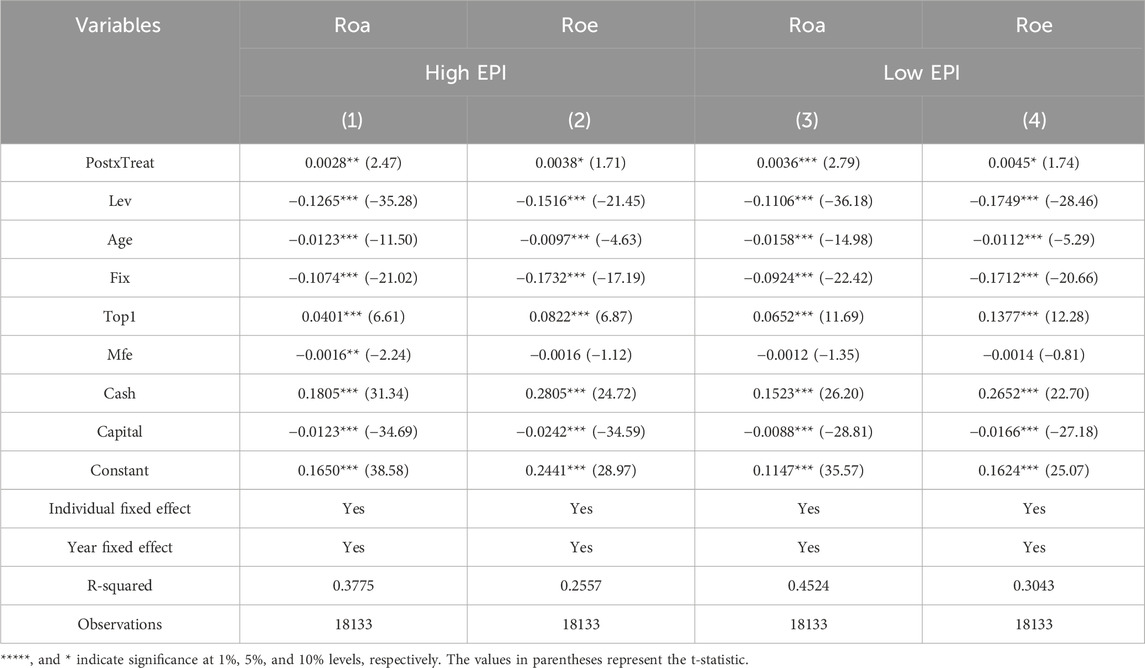

To identify the heterogeneity in the impact of green insurance policies on the performance of enterprises with different levels of environmental investment, this study categorizes the sample into high environmental investment enterprises and low environmental investment enterprises based on the median environmental investment level. The results of the grouped regression are shown in Table 6. The results indicate that the regression coefficients of the green insurance policy dummy variable for Roa and Roe are significantly positive across enterprises with different levels of environmental investment. However, the coefficients are larger for enterprises with lower levels of environmental investment. This suggests that green insurance has a more pronounced effect on improving the performance of enterprises with weaker environmental awareness and lower levels of environmental investment.

5.1.2 Ownership heterogeneity

To identify the heterogeneity in the impact of green insurance policies on the performance of enterprises with different ownership structures, this study divides the research sample into state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises. The results of the grouped regression are presented in Table 7. The findings indicate that the regression coefficients for the green insurance policy dummy variable are significantly positive for both Roa and Roe in non-state-owned enterprises. However, these coefficients exhibit lower significance and magnitude in the state-owned enterprise sample. This suggests that green insurance has a more pronounced performance-enhancing effect on non-state-owned enterprises compared to state-owned enterprises.

5.1.3 Heterogeneity in financing constraints

To identify the heterogeneity in the impact of green insurance policies on corporate performance across enterprises with differing levels of financing constraints, this study categorizes the sample into high-constraint and low-constraint enterprises based on the median SA index. The results of the grouped regression are presented in Table 8. The results show that the regression coefficients of the green insurance policy dummy variable on Roa and Roe are significantly positive for both highly and lowly financially constrained enterprises. However, the regression coefficient is larger in the lowly financially constrained sample. This indicates that, compared to highly financially constrained enterprises, green insurance has a more pronounced effect on improving the performance of lowly financially constrained enterprises.

5.2 Mechanism analysis

This study employs a two-step approach to examine the mechanism, with technological innovation (Tec) and financing capacity (Ability) serving as the mechanism variables. The benchmark regression results from the first step are presented in Table 2 and are not repeated here. Specific findings from the mechanism test are shown in Table 9.

5.2.1 Technological innovation mechanism

Column (1) results indicate that the regression coefficient for the green insurance policy dummy variable on the number of patents obtained by enterprises is significantly positive at the 1% level. Combined with the preceding theoretical analysis on technological innovation’s impact on heavily polluting enterprises’ performance, this indicates that Hypothesis 4 holds true: the implementation of green insurance policies enhances enterprise performance in heavily polluting industries by promoting technological innovation mechanisms.

5.2.2 Financing capacity mechanism

Column (2) results indicate that the regression coefficient for the green insurance policy dummy variable on the proportion of short-term debt is significantly positive at the 5% level. Combined with the preceding theoretical analysis on how financing capacity affects the performance of heavily polluting enterprises, this conenterprises Hypothesis 3: the implementation of green insurance policies enhances the performance of heavily polluting enterprises by promoting their investment and financing mechanisms.

5.3 Analysis of mediating pathways

To further investigate whether green insurance influences the performance of heavily polluting enterprises through specific pathways, after centering the relevant variables, an interaction term approach was employed to analyze the effects of board size (Board) and independent director proportion (Indep) on the performance of heavily polluting enterprises. The specific results are presented in Tables 10 and 11.

5.3.1 Board size

For Roa in columns (1) and (2) of Table 10, regression coefficients were significantly positive at the 1% level before adding the interaction term. After adding it, only its coefficient was significantly negative. This indicates that board size negatively moderates the impact of green insurance on the performance of heavily polluting enterprises, larger boards are less conducive to improving such enterprises’ performance. For Roe in columns (3) and (4), the conclusions align with those for Roa both before and after adding the interaction term. Thus, Hypothesis 5 holds: board size may exert a negative moderating effect on the impact of green insurance policies on the performance of heavily polluting enterprises.

5.3.2 Proportion of independent directors

For Roa in columns (5) and (6) of Table 11, the regression coefficients were both significantly positive at the 1% level before including the interaction term. After adding it, its coefficient remained significantly positive. This indicates that the proportion of independent directors positively moderates the impact of green insurance on the performance of heavily polluting enterprises. A higher proportion of independent directors is more conducive to improving the performance of heavily polluting enterprises. For Roe in columns (7) and (8), the conclusions align with those for Roa both before and after adding the interaction term. Therefore, Hypothesis 6 holds: the proportion of independent directors may exert a positive moderating effect on the process by which green insurance policy implementation influences the performance of heavily polluting enterprises.

6 Research findings and policy implications

Against the backdrop of deepening progress toward the “dual carbon” strategic goals, the policy impact of green insurance as a market-based environmental governance tool has drawn significant attention. This study employs the 2013 implementation of the “Guiding Opinions on Launching Pilot Programs for Mandatory green Insurance” targeting high-environmental-risk industries as a quasi-natural experiment. Using data from A-share listed enterprises between 2008 and 2023, it systematically evaluates the effects of green insurance policy on the performance of heavily polluting enterprises through a difference-in-differences method. The findings reveal: (1) The implementation of the green insurance policy significantly improved the performance levels of heavily polluting enterprises. This conclusion remains robust after undergoing a series of stability tests, including parallel trend tests, PSM-DID analysis, exclusion of municipal samples, elimination of major policy interference and placebo tests. (2) Heterogeneity analysis reveals structural differences in the policy effects of green insurance, with its performance-enhancing impact being more pronounced for enterprises with lower environmental investment levels, non-state-owned attributes, and lighter financing constraints. (3) Mechanism tests reveal that green insurance primarily improves corporate performance through two pathways: incentivizing technological innovation and enhancing short-term debt financing capacity. (4) Further analysis indicates that corporate governance structures play a crucial moderating role. Larger board sizes weaken the performance-enhancing effects of green insurance, while a higher proportion of independent directors amplifies these positive impacts. Besides, the empirical results of this study confirm that green insurance exerts a performance-enhancing effect, which provides critical micro-level evidence for addressing the dilemma of “weak supply and demand”. Given that insurance participation improves corporate performance, the crux of “weak demand” should no longer be simply attributed to the pure cost theory. Instead, it may stem from enterprises’ insufficient awareness of this performance-enhancing effect, or the failure of existing insurance products to effectively convert policy dividends into perceptible benefits for enterprises. Therefore, the above findings offer the following policy implications:

First, strengthen legislative safeguards and institutional frameworks to transition green insurance from “pilot exploration” to “standardized operation.” Studies have confirmed that green insurance effectively enhances corporate performance, primarily through mediating mechanisms such as influencing corporate investment and financing activities and technological innovation behaviors. Therefore, substantially advancing the pilot program in both breadth and depth is a crucial measure for accelerating the green transformation of development patterns and improving the modern environmental governance system. The primary follow-up task should focus on refining the institutional framework for green insurance. The absence of legislation is the core factor hindering the effectiveness of current pilot programs. It is recommended to summarize the experience from comprehensive reform pilots of mandatory green insurance in Shenzhen and other regions, clearly defining the mandatory coverage scope, insurance liabilities and compensation standards for high-risk enterprises, thereby providing a legal basis for the comprehensive implementation of green insurance. Simultaneously, regulatory mechanisms for green insurance should be streamlined. The division of responsibilities between the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and the National Financial Regulatory Administration in overseeing green insurance operations should be clarified. In collaboration with insurance enterprises, detailed guidelines for risk assessment and premium rate determination should be established to enhance the standardization and transparency of policy terms, reduce transaction costs and improve market efficiency.

Second, optimize policy incentives and promotional guidance to precisely stimulate non-state-owned enterprises’ intrinsic motivation for insurance coverage. Studies indicate that green insurance significantly enhances the performance of non-state-owned enterprises, yet their willingness to purchase coverage remains relatively low. Therefore, differentiated incentives should be implemented at a policy level: First, non-state-owned enterprises, especially small and medium-sized private enterprises, should be identified as the key target groups for green insurance policy promotion and fiscal subsidies. Second, further increase the premium subsidy ratio for non-state-owned enterprises, or explore linking green insurance coverage to policies such as tax incentives and green project approvals. Third, insurance institutions should strengthen promotion of performance enhancement case studies for green insurance. Through white papers, industry forums and other channels, they should clearly articulate the comprehensive value of green insurance in risk protection, financing credit enhancement and technological innovation to corporate managers, thereby shifting their perception of green insurance as merely a “compliance cost”.

Third, deepen the insurance and service model to highlight the core role of insurance institutions in risk mitigation management, while implementing targeted measures based on the results of heterogeneity analysis. The value of green insurance extends beyond post-incident compensation to proactive risk prevention and differentiated support. Through mandatory requirements or incentive policies, insurance companies should be promoted to allocate a designated portion of premium income to uniformly provide specialized services such as environmental risk assessment, hazard identification and eco-technology consulting for insured enterprises, thereby solidifying and deepening risk mitigation management. On this basis, differentiated supporting countermeasures should be implemented for different types of enterprises: for enterprises with low environmental investment, a bundled scheme of premium subsidies and technical support should be simultaneously promoted. For enterprises facing severe financing constraints, a linkage mechanism of green insurance and green credit should be established. For enterprises with sound governance structures, value-added insurance products should be developed. Regulators can incorporate the coverage, quality of specialized services and the effectiveness of differentiated countermeasures into insurance institutions’ performance evaluation systems, elevating green insurance from a simple financial risk transfer tool to a collaborative governance partner and targeted support platform in corporate environmental risk management.

Fourth, innovate the green insurance and green finance synergy mechanism to broaden financing channels for corporate transformation. Green insurance indirectly promotes performance improvement by enhancing corporate financing capabilities. Efforts should focus on establishing a linkage between insurance and credit markets. Financial institutions should be encouraged to recognize the credit enhancement and collateral functions of green insurance policies, developing structured financing products such as “green insurance and green credit” and “green insurance and green bonds.” Regulatory authorities should establish guidelines clarifying the recognition standards for green insurance policies in bank credit ratings and risk mitigation. This would systematically ease financing constraints of heavily polluting enterprises, particularly small and medium-sized businesses, thereby providing adequate capital support for their technological innovation and green transition.

Finally, the optimization of corporate governance structure should be incorporated into the incentive mechanism for green insurance to guide enterprises in improving their internal decision-making and supervision systems. Studies have confirmed that sound corporate governance can effectively strengthen the positive impact of green insurance in promoting corporate performance. Therefore, it is recommended that regulatory authorities and insurance enterprises collaborate to make corporate governance structures a key reference factor for adjusting green insurance premium rates. Regulators may incorporate the optimization of board structures into enterprises’ environmental credit evaluation systems or encourage insurance companies to offer premium discounts to enterprises with sound governance structures—for instance, enterprises with well-structured boards and effective oversight by independent directors may receive such preferential treatment to create positive incentives. Meanwhile, listed companies should improve the functions and accountability mechanisms of independent directors in environmental risk management and control. Regulators may consider requiring the boards of heavily polluting enterprises to solicit special opinions from independent directors when making decisions on environmental risk issues such as green insurance. Besides, heavily polluting enterprises should focus on strengthening their internal capabilities, enhancing management’s environmental governance skills and increasing corporate attention and application efficiency for green insurance tools from the decision-making source.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LX-G: Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization. ZS-Z: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. WW-Y: Writing – original draft, Investigation. WY-D: Validation, Writing – review and editing. CN-N: Writing – review and editing, Supervision.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. National Social Science Fund of China Project, “Research on the Construction and Policy Options of a Modern Agricultural Investment and Financing Mechanism Coupled and Coordinated by Multiple Agents and Channels” (Grant No. 22BJL014).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bucheli, J., Conrad, N., Wimmer, S., Dalhaus, T., and Finger, R. (2023). Weather insurance in European crop and horticulture production. Clim. Risk Manag. 41, 100525. doi:10.1016/j.crm.2023.100525

Calderón, R., Piñero, R., and Redín, D. M. (2020). Understanding Independence: board of directors and CSR. Front. Psychol. 11, 552152. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.552152

Chen, Y., and Xie, Y. (2024). Environmental liability insurance, green innovation, and mediation effect study. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1363199. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2024.1363199

Fan, W., Yan, L., Chen, B., Ding, W., and Wang, P. (2022). Environmental governance effects of local environmental protection expenditure in China. Resour. Policy 77, 102760. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102760

Fan, M., Liu, W., and Yao, D. (2025). The impact of green finance reform and innovation pilot zones on corporate pollution and carbon reduction: from the perspective of dual objective constraints. J. Environ. Manag. 389, 126110. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.126110

Guo, M., Wang, H., and Kuai, Y. (2023). Environmental regulation and green innovation: evidence from heavily polluting firms in China. Finance Res. Lett. 53, 103624. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2022.103624

He, Y., Zhang, Y., and Zhang, X. (2025). How does voluntary environmental information disclosure affect corporate green financing capability? Evidence from Chinese heavy polluting industries. J. Environ. Manag. 373, 123495. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123495

Liang, H., Wang, Z., and Niu, R. (2023). Does environmental regulations promote the green transformation of high polluters? Appl. Econ. Lett. 30, 927–931. doi:10.1080/13504851.2022.2030034

Liu, H., Liu, Z., Zhang, C., and Li, T. (2023). Transformational insurance and green credit incentive policies as financial mechanisms for green energy transitions and low-carbon economic development. Energy Econ. 126, 107016. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2023.107016

Liu, P., Lin, B., Zhou, H., Li, X., and Papachristos, G. (2025). Effect of green finance on the green transformation of China’s building sector: a system dynamics assessment for targeted financing instruments and policies. Energy 334, 137845. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.137845

Lu, J., Li, H., and Yang, R. (2024). Effects of environmental liability insurance on illegal pollutant discharge of heavy polluting enterprises: emission reduction incentives or pollution protector? Socio-Economic Plan. Sci. 92, 101830. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2024.101830

Ning, J., Yuan, Z., Shi, F., and Yin, S. (2023). Environmental pollution liability insurance and green innovation of enterprises: incentive tools or self-interest means? Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1077128. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2023.1077128

Porter, M. E., and van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9, 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Reijnders, L. (2003). Policies influencing cleaner production: the role of prices and regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 11, 333–338. doi:10.1016/S0959-6526(02)00027-6

Shaukat, A., and Trojanowski, G. (2018). Board governance and corporate performance. J. Bus. Finance and Account. 45, 184–208. doi:10.1111/jbfa.12271

Shi, H., and Zhou, Q. (2024). Government R&D subsidies, environmental regulation and corporate green innovation performance. Finance Res. Lett. 69, 106088. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2024.106088

Wang, B., and Zhao, W. (2022). Interplay of renewable energy investment efficiency, shareholder control and green financial development in China. Renew. Energy 199, 192–203. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.08.122

Wang, C., Nie, P., Peng, D., and Li, Z. (2017). Green insurance subsidy for promoting clean production innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 148, 111–117. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.145

Wang, L.-J., Lin, Z.-H., and Yang, P.-L. (2024a). Decoding the impact of fiscal decentralization on urban pollution intensity in China: a spatial econometric analysis. Heliyon 10, e30131. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30131

Wang, Y., Feng, J., Shinwari, R., and Bouri, E. (2024b). Do green finance and green innovation affect corporate credit rating performance? Evidence from machine learning approach. J. Environ. Manag. 360, 121212. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121212

Wu, W., Zhang, P., Zhu, D., Jiang, X., and Jakovljevic, M. (2022). Environmental pollution liability insurance of health risk and corporate environmental performance: evidence from China. Front. Public Health 10, 897386. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.897386

Wu, S., Cai, D., Wang, X., and Chen, H. (2025). Does the Chinese new diversified green finance affect corporate employee demand? J. Environ. Manag. 387, 125810. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.125810

Xie, Y. (2024). The interactive impact of green finance, ESG performance, and carbon neutrality. J. Clean. Prod. 456, 142269. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142269

Yang, Y., Liu, H., Guo, Q., and Jia, X. (2020). Environmental pollution liability insurance to promote environmental risk management in chemical industrial parks. Resour. Conservation Recycl. 152, 104511. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104511

Yu, J., Shi, X., Guo, D., and Yang, L. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and firm carbon emissions: evidence using a China provincial EPU index. Energy Econ. 94, 105071. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2020.105071

Yu, J., Liu, P., Shi, X., and Ai, X. (2023). China’s emissions trading scheme, firms’ R&D investment and emissions reduction. Econ. Analysis Policy 80, 1021–1037. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2023.09.039

Yu, J., Cai, X., Ji, X., Liang, L., and Yang, J. (2025). Promoting urban energy transitions: lessons from interpretable machine learning with evidence from China. Energy 334, 137812. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.137812

Yuan, J., and Liu, S. (2024). A double machine learning model for measuring the impact of the made in China 2025 strategy on green economic growth. Sci. Rep. 14, 12026. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-62916-0

Zhang, T. (2023). Can green finance policies affect corporate financing? Evidence from China’s green finance innovation and reform pilot zones. J. Clean. Prod. 419, 138289. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138289

Zhang, H., and Wei, S. (2024). Green finance improves enterprises’ environmental, social and governance performance: a two-dimensional perspective based on external financing capability and internal technological innovation. PLOS ONE 19, e0302198. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0302198

Zhang, G., Guo, B., and Lin, J. (2023a). The impact of green finance on enterprise investment and financing. Finance Res. Lett. 58, 104578. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2023.104578

Zhang, Z., Fu, H., Xie, S., Cifuentes-Faura, J., and Urinov, B. (2023b). Role of green finance and regional environmental efficiency in China. Renew. Energy 214, 407–415. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2023.05.076

Zhang, S., Dou, W., Ji, R., Afthanorhan, A., and Hao, Y. (2024a). Can green finance promote the low-carbon transformation of the energy system? New evidence from city-level data in China. J. Environ. Manag. 365, 121577. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121577

Zhang, X., Chen, J., Yu, C., Wang, Q., and Ding, T. (2024b). Emergency risk assessment of sudden water pollution in south-to-north water diversion project in China based on driving force–pressure–state–impact–response (DPSIR) model and variable fuzzy set. Environ. Dev. Sustain 26, 20233–20253. doi:10.1007/s10668-023-03468-7

Keywords: green insurance, heavy-polluting enterprises, corporate performance, difference-in-differences method, technological innovation, investment and financing capacity

Citation: Xin-Guang L, Shi-Zheng Z, Wen-Yu W, Yu-Dong W and Nan-Nan C (2025) How does the green insurance policy affect the performance of heavy-polluting enterprises: an empirical study based on Chinese listed companies. Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1735658. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1735658

Received: 30 October 2025; Accepted: 26 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Jian Yu, Central University of Finance and Economics, ChinaReviewed by:

Wu Junqian, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, ChinaZhao Hongdan, Jilin Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Xin-Guang, Shi-Zheng, Wen-Yu, Yu-Dong and Nan-Nan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cao Nan-Nan, Y2Fvbm5hbkAxNjMuY29t

Li Xin-Guang1

Li Xin-Guang1 Wang Wen-Yu

Wang Wen-Yu Cao Nan-Nan

Cao Nan-Nan