- 1Faculty of Foreign Studies, Beijing Language and Culture University, Beijing, China

- 2School of Music, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China

- 3School of Statistics and Data Science, Qufu Normal University, Qufu, China

To comprehensively advance the construction of a Beautiful China and achieve harmonious coexistence between humans and nature, the Ministry of Water Resources issued a pilot policy for the development of aquatic ecological civilization cities in 2013, expanding the pilot scope in 2014. This paper investigates whether this policy can promote green technological innovation in enterprises and explores the underlying mechanisms. Utilizing green patent data from listed Chinese enterprises between 2010 and 2018, empirical analysis is conducted through a multi-period difference-in-differences model. The research findings indicate that the construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities significantly enhances green technological innovation among enterprises. Robustness tests confirm the validity of these conclusions. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that that the policy is particularly effective in water pollution intensive industries, state-owned enterprises and eastern regions. Mechanism analysis illustrates that the construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities fosters green technological innovation by reinforcing environmental regulations and alleviating financial constraints on enterprises. The paper recommends a comprehensive implementation of the aquatic ecological civilization city policy, emphasizing enterprise green technological innovation to establish a solid foundation for China’s green economic development.

Highlights

First, this study investigates the impact of constructing aquatic ecological civilization cities from the perspective of enterprise green technology innovation, discussing the interplay between ecological civilization development and green technology advancement. Second, by considering differences in enterprise endowments, the paper examines how the construction of water ecological civilization cities affects water pollution intensity and ownership structures across various industries, thereby strengthening the causal relationship and expanding the research framework. Third, by analyzing policy root causes and considering both the intensity of environmental regulations and corporate financing constraints, the paper elucidates the internal logic of government intervention in the construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities as it pertains to corporate green technology innovation, proposing research hypotheses and offering empirical insights at the micro level.

1 Introduction

With the continuous aggravation of global environmental problems, water resource protection and sustainable utilization have become major challenges commonly faced by all countries. As the world’s largest developing country, China has encountered a series of prominent problems such as water shortage, degradation of water ecosystems and water environmental pollution during its rapid industrialization and urbanization process. Water pollution not only intensifies the shortage of water resources and the frequency of sudden pollution incidents, but also has a severe impact on industrial production and agricultural growth, causing significant economic losses and negative social effects. It has become a key bottleneck restricting sustainable development and directly threatens human health and survival safety. According to the national surface water quality monitoring data, only 32.2% of the river sections meet the requirements of Class I and Class II water quality in the “Surface Water Environmental Quality Standards”, 28.9% of the river sections are of Class III water quality, while as many as 38.9% of the river sections are of Class IV and V water quality1. Meanwhile, about two-thirds of cities in our country have long been facing water shortages, among which 110 cities are in a state of extreme water shortage2. The extensive development model has further exacerbated the deterioration of the water ecological environment. Over 60% of urban groundwater quality fails to meet standards, and more than 30% of rivers have severely degraded their ecological functions3. They not only lose their drinking value but are even no longer suitable for direct contact. Among various environmental pollution incidents, water pollution accidents account for as high as 60%, and the economic losses they cause far exceed those of other types of pollution, highlighting the urgency and complexity of water pollution control.

The water environment has typical attributes of public goods, which can easily lead to “free-riding” and “opportunistic” behaviors, exacerbating externality problems. Meanwhile, as public assets, water resources have ambiguous property rights boundaries, making them highly prone to the “tragedy of the Commons”, which leads to the continuous deterioration of water environment quality and quantity. To alleviate this predicament, it is urgent for the government to internalize negative externalities through scientific and effective environmental regulations, thereby promoting the efficient utilization and sustainable protection of water resources. The report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China clearly states that we should “promote the building of a beautiful China, further advance the prevention and control of environmental pollution, and continuously and deeply fight the battle for clear waters”, and emphasizes “coordinating the governance of water resources, water environment and water ecology”. Under this strategic guidance, the Chinese government has put forward the goal of building water ecological civilization cities, aiming to achieve coordinated development of the economy, society and ecological protection by strengthening water resource management, improving water environment quality and enhancing ecosystem services. Environmental regulatory policies play a crucial role in promoting sustainable development, facilitating high-quality growth, and fostering a circular and green economy (Zhao et al., 2025). In 2013, the Ministry of Water Resources issued the “Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of Water Ecological Civilization”, marking the official launch of the pilot policy for the construction of water ecological civilization cities. This policy takes the strictest water resources management system as its core, adheres to the water management concept of “prioritizing water conservation, achieving spatial balance, implementing systematic governance, and exerting efforts from both government and market”, and its key goals include optimizing water resources allocation, strengthening water environmental protection and promoting comprehensive governance. It also takes green technological innovation as an important engine for policy drive. From 2012 to 2014, the Ministry of Water Resources identified a total of 105 pilot areas for water ecological civilization city construction. By 2018 to 2019, 99 pilot regions had passed the acceptance inspection.

As policies are gradually implemented, enterprises play a key role in the construction of water ecological civilization cities. The construction of a water ecological civilization elevates environmental issues to the “civilization” level, transforming the government-led approach to water pollution control and achieving a dynamic balance between economic growth, environmental protection, and social welfare (Zhao et al., 2025). In this process, green technological innovation of enterprises is regarded as an important path that takes into account both environmental and economic benefits. Green technology innovation serves as a vital catalyst for enterprises to expand market share, strengthen core competitiveness, and ensure long-term survival (Takalo et al., 2021). Through green research and development and technological application, enterprises can reduce resource consumption and pollution emissions, and enhance ecological performance and economic efficiency. This is not only a necessary condition for achieving the goal of water ecological civilization construction, but also a strategic choice for enterprises to respond to environmental regulations, enhance competitive advantages and achieve sustainable development. Under the joint influence of policy guidance and market demand, an increasing number of enterprises are increasing their investment in green research and development, promoting the development and application of low-energy consumption, low-pollution and high-efficiency technologies and products, providing strong support for the improvement of urban water environment and the recycling of resources. Previous studies have found that this policy has promoted technological innovation in water conservation, sewage treatment and resource recycling by enterprises, reduced water resource consumption and pollution emissions, and significantly improved the water resource utilization efficiency and water quality compliance rate in the pilot areas (Pei et al., 2021). It can be seen from this that the construction of water ecological civilization cities has profound significance for promoting the high-quality development of China’s economy and society, and demonstrates important practical value in enhancing the green technological innovation capabilities of enterprises. However, the existing literature on the construction of water ecological civilization cities is predominantly limited to qualitative studies (Zhang et al., 2018; Minatour et al., 2016). There remains a lack of systematic evaluation of this policy’s effectiveness in driving green technological innovation among enterprises, leaving ample room for future research.

Based on this, this paper regards the pilot policy for water ecological civilization city construction as a quasi-natural experiment. By combining the green patent data of Chinese listed companies from 2010 to 2018 and using a multi-period difference-in-differences model, it systematically assesses the impact of this policy on the green technological innovation of enterprises and its mechanism of action. By empirically testing the two key pathways of “strengthening environmental regulation” and “relieving corporate financing constraints”, the study aims to uncover the “black box” of how policies influence corporate innovation decisions. Meanwhile, it conducts an in-depth analysis of the heterogeneity of policy effects, focusing on whether they exhibit more significant promoting effects in water pollution-intensive industries and state-owned enterprises, to clarify the boundary conditions and key groups for policy effectiveness, laying a micro-foundation for the green transformation and development of China’s economy.

The contributions of this article are mainly reflected in the following three aspects: First, from the perspective of enterprise green technological innovation, it assesses the policy effects of water ecological civilization city construction, and combines the research context of ecological civilization construction and green innovation to expand the understanding of the relationship between environmental policies and enterprise innovation. Second, based on the heterogeneity of enterprises, the intensity of water pollution in different industries and the differences in policy responses among enterprises of different ownerships should be examined to enhance the rigor of causal identification and expand the scope of research. Thirdly, on the basis of sorting out the root causes of policies, reveal the mechanism of policy action from the dual perspectives of environmental regulation intensity and enterprise financing constraints, put forward theoretical hypotheses, and provide empirical evidence at the micro level, thereby enriching the research framework of environmental regulation and enterprise green innovation.

2 Policy background and theoretical analysis

2.1 Policy background

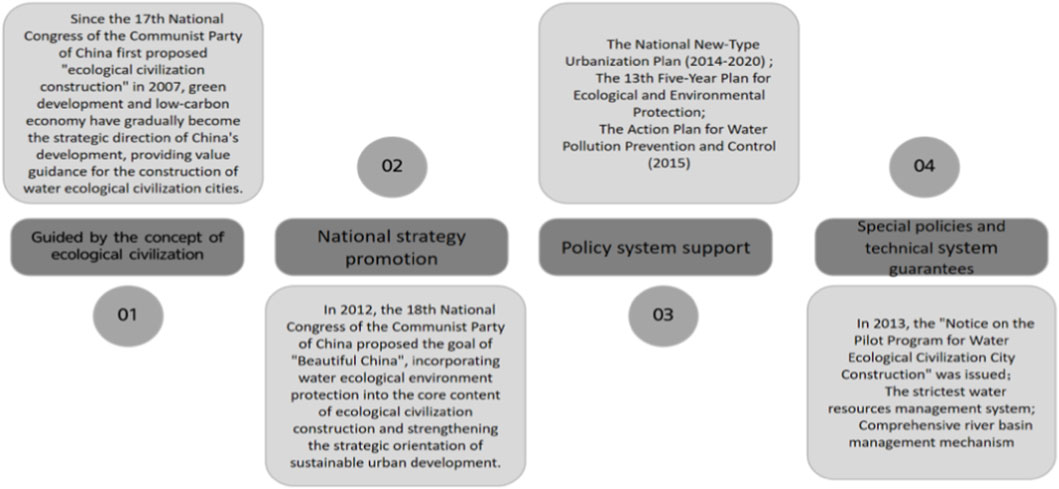

The construction of water ecological civilization cities, a significant component of China’s ecological civilization development, is underpinned by a policy framework that has evolved since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. Following this congress, the strategic importance of ecological and environmental protection has been steadily reinforced by both the Party and the state. The release of the “Action Plan for Water Pollution Prevention and Control” in 2015 marked a pivotal moment, ushering in a new phase of systematic and institutional approaches to water ecological governance. This plan explicitly called for the promotion of urban water ecological civilization construction and the establishment of a “safe, clean, healthy, and beautiful” water environment system.

Subsequent documents, including the “Technical Guidelines for the Construction of National Water Ecological Civilization Cities” and the “14th Five-Year Plan for Ecological and Environmental Protection,” have further elaborated on relevant goals and pathways. These initiatives emphasize the coordinated governance of water resources, water environments, and water ecology, advocating for a basin-based approach while promoting the green and low-carbon transformation of cities. The ongoing advancements at the policy level have not only provided a robust institutional guarantee for the construction of water ecological civilization cities but also offered strategic guidance for practical exploration and effectiveness evaluation. This is illustrated in the empirical data presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The policy background of water ecological civilization city construction. Information sourced from China’s 11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th Five Year Plans.

As early as the “11th Five-Year Plan” period, China began to prioritize the comprehensive management of the urban water environment, recognizing the importance of coordinating water resource protection with pollution prevention and control (Yang et al., 2022). During the “12th Five-Year Plan” period, the concept of water ecological civilization was gradually integrated into the national development strategy4. In 2013, the Ministry of Water Resources initiated the first batch of pilot projects for constructing water ecological civilization cities, marking the beginning of systematic construction efforts.

Since the “13th Five-Year Plan”, the pilot program has been expanded on a larger scale, shifting the focus of construction from infrastructure development to ecosystem restoration and the innovation of institutional mechanisms5. In the “14th Five-Year Plan” period, the construction of water ecological civilization cities was incorporated into the broader framework of national ecological civilization initiatives6. This integration emphasizes coordinated governance of river basins, a green and low-carbon transformation, and the pursuit of high-quality development. The overall trend reflects a progressive enhancement of governance systems and a continuous innovation in governance methods. This evolution illustrates a significant transformation in water ecological governance in our country, moving from isolated rectifications to systematic coordination and shifting from engineering-focused governance to institutional governance. The detailed development process is illustrated in the accompanying Figure 2.

Figure 2. The development process of policies for water ecological civilization cities. Information sourced from China’s 11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th Five Year Plans.

As illustrated in Figure 3, there was a significant increase in Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) and the total volume of wastewater discharge between 2015 and 2018, peaking in 2018 before declining rapidly to maintain a relatively low level thereafter. This trend suggests that the construction of water ecological civilization cities has likely played a pivotal role in fostering green technological innovation among enterprises.

Figure 3. COD and wastewater discharge volume. The data is sourced from the Guotai An database, with units of tons.

With the promotion of the water ecological civilization concept, the government has intensified the enforcement of water environment governance policies within the region, compelling enterprises to accelerate their green transformation through stricter environmental standards and oversight (Su et al., 2021). In response to the requirements for ecological civilization construction, many companies have invested in green technological transformation and innovation, effectively reducing pollutant emissions (Sun and Fei, 2021). Particularly after 2018, a number of cities successfully completed the establishment of water ecological civilization cities, markedly curtailing the discharge of organic pollutants into water bodies7. This indicates that the institutional framework and management practices associated with water ecological civilization cities have exerted pressure and motivation on enterprises to innovate technologically, facilitating their transition to greener operations and leading to significant improvements in regional water quality.

2.2 Theoretical analysis

2.2.1 Construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities and enterprise green technological innovation

The pilot policy for the construction of water ecological civilization cities, as a command and control environmental regulation policy, has the core feature of forming rigid constraints through the strictest water resource management system. Unlike general environmental regulations, this policy establishes more precise constraint indicators and assessment systems for water resource utilization and protection, providing a unique policy environment for green technology innovation in enterprises. As the largest social production entity, enterprises’ production and operation activities directly affect the safety of the ecological environment. Whether it is possible to control pollutant emissions while creating economic profits is related to the sustainable development of society. The construction of water ecological civilization cities is led by the government and implemented by enterprises as the main body of policies. In the context of GDP driven political competition, local officials are promoting economic growth and environmental protection while also seeking promotion opportunities. Faced with strict water resource constraints, the “layered reinforcement” management model from the central to local and then to enterprises has become the choice for water environment governance (Muhammad et al., 2025).

The policy of water ecological civilization cities directly affects enterprise production decisions through specific measures such as water resource utilization intensity control, water efficiency red lines, and total pollutant discharge restrictions. When facing strict water resource constraints, enterprises must seek technological innovation to adapt to the new regulatory environment in order to maintain legal production and market competitiveness. The implementation of pilot policies for the construction of water ecological civilization cities can help improve industrial water efficiency, reduce water pollution emissions, and promote the transformation of industries towards green environmental protection, comprehensively improving the water ecological environment. At the same time, technological innovation in enterprises has been developed in this process, promoting the construction of water ecological civilization by enhancing existing technologies and researching new green technologies. While achieving the goal of water environment governance, it also promotes economic growth, which is a re examination of the Porter hypothesis - appropriately designed environmental regulations can stimulate corporate innovation, partially or completely offset environmental costs, and generate innovation compensation effects (Porter and Van der Linde, 1995).

Although this policy is a command and control environmental regulation policy, the regulatory intensity varies. Each pilot city formulates water environment governance policies based on its own economic, technological, and industrial advantages, which leads to differences in environmental regulation schemes among different cities, and thus different levels of incentives for green technology innovation in enterprises (Tang et al., 2024; Nie et al., 2023). Therefore, the construction of water ecological civilization cities strives to achieve the goal of overall water environment governance in China by integrating various policy advantages.

In conclusion, we propose Hypothesis H1: The construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities can effectively promote enterprise green technological innovation.

As a strict environmental policy, the pilot policy for the construction of water ecological civilization cities promotes the improvement of urban environmental regulation level through the strictest water resource management system; On the other hand, the introduction of social capital enhances trust and alleviates financing constraints for enterprises, forming a joint force to promote green technology innovation in enterprises.

2.2.2 Stringency of environmental regulation and enterprise green technological innovation

Environmental regulation serves as the primary mechanism through which the government coordinates environmental protection with economic development. In the context of fiscal decentralization, while environmental policies are established by the central government, local governments retain a degree of discretion. To excel in evaluations, local officials actively engage in the construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities, enhancing the rigor of environmental regulations to minimize policy deviations. This collaboration facilitates a partnership between local governments and enterprises in environmental governance, striving for a win-win scenario that benefits both the environment and the economy.

The construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities can precisely improve the standards of urban environmental supervision, and the core of this mechanism lies in the policy design of classified regulation and differentiated incentives. In the institutional context of fiscal decentralization and political promotion incentives coexisting, local governments have the motivation to strictly implement water environment governance policies in order to gain a competitive advantage in the official assessment system. Effective environmental protection measures can stimulate enterprise green technological innovation, leading to synergistic efficiency between economic growth and environmental sustainability (Guo et al., 2025). When water environmental governance becomes part of the performance assessment system for party and government officials, those under promotional pressure are likely to prioritize the construction of aquatic ecological civilization. However, enterprises typically focus on maximizing profits, which may lead them to seek advantages through pollutant emissions. In situations where government and enterprise interests conflict, the government intervenes in enterprise operations to encourage green technological innovation or restrict the entry of highly polluting companies. Under the strictest water resource management system, governments at all levels impose limits on total pollutant emissions and intensify efforts in water pollution prevention and control. Recognizing the government’s commitment and policy direction in water environmental governance, rational economic entities—namely, enterprises—are encouraged to improve water quality and optimize resource use through green technological innovation, reduced wastewater discharge, enhanced pollution control capabilities, and improved water efficiency, thereby advancing the construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities (Yang et al., 2021).

Lastly, resolving conflicts of interest between environmental regulations and various stakeholders is essential for achieving economic growth (Lou et al., 2020). Environmental regulation can enhance enterprise production efficiency, improve overall performance, and ultimately stimulate regional economic development. The objective of environmental regulation is to achieve a balance between environmental governance and economic growth, primarily by optimizing resource allocation and promoting the transformation and upgrading of industrial structures. As an environmental regulatory policy, the pilot initiative for constructing aquatic ecological civilization cities imposes constraints on water resources for enterprises, compelling them to engage in green technological innovation, improve water resource efficiency, and shift high-water-consuming, high-polluting industries toward low-emission, high-efficiency development models, thereby fostering economic growth. Additionally, the effect of innovation compensation enhances enterprise production efficiency. Strict environmental regulations increase operational pressures on enterprises, driving them to pursue technological innovations, undergo green transformations, improve total factor productivity, and effectively showcase the roles of pilot cities.

In conclusion, we propose Hypothesis H2: The construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities promotes enterprise green technological innovation by enhancing the stringency of environmental regulation.

2.2.3 Enterprise financial constraints and enterprise green technological innovation

The construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities creates opportunities for social capital participation, helping to alleviate financing challenges for enterprises. When companies pursue research and development innovations, investors may be reluctant to invest due to a lack of understanding of the technological projects and difficulties in estimating potential returns, leading to low investment interest. Furthermore, to prevent competitors from replicating their technologies, enterprises may not fully disclose project information, resulting in information asymmetry that increases financing difficulties. By introducing social capital, trust in the enterprise community can be enhanced, encouraging more investors to invest with confidence. The construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities focuses on multi-level governance, integrating government, enterprises, and the public into a “social governance” model, with “social trust” being a prerequisite for its success. The incorporation of social capital effectively addresses information asymmetry, strengthens investor confidence in innovative enterprises, reduces financing pressures, and promotes green technological innovation among these businesses (Liu et al., 2024).

In addition to enhancing trust and alleviating financing constraints through the introduction of social capital, pilot areas have developed a series of green economic policies, including green credit, green bonds, green stock indices, green development funds, and green insurance tools. These initiatives, such as specialized funds for water environmental governance, subsidies for water pollution-intensive industries, financing incentives, and tax reductions, significantly ease the financing difficulties faced by enterprises. On one hand, more lenient financing policies enable enterprises to leverage external funding to share the costs and risks associated with environmental investments, thereby alleviating cash flow pressures. Instead of reducing production, increasing investments in environmental governance allows enterprises to more effectively decrease pollution emissions, comply smoothly with government regulations, and mitigate the negative impacts of pollution discharge fees. On the other hand, strict financing constraints can hinder enterprises from securing adequate external funds necessary for environmental governance, making it challenging to manage the high costs and risks associated with technological investments. This scenario can lead to a preference for production reduction to lower emissions rather than pursuing pollution control measures.

Pilot areas strategically utilize green economic policies to optimize fund allocation across industries and decrease investments in polluting projects. Local governments, through the induced effect of environmental protection fiscal expenditures, can redirect funds toward green industries and water environmental governance, alleviating financing challenges and fostering enterprise green technological innovation.

In conclusion, we propose Hypothesis H3: The construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities promotes enterprise green technological innovation by alleviating financial constraints faced by enterprises.

3 Research design

3.1 Model setting

This section is based on the quasi-natural experiment of the pilot policy for constructing aquatic ecological civilization cities implemented in China in 2013 and 2014. It employs a multi-period difference-in-differences model to identify the actual effects of aquatic ecological civilization city construction on enterprise green technological innovation. The pilot list published by the Ministry of Water Resources was searched and organized, with the cities and county-level enterprises included in the first two batches of the pilot program designated as the treatment group, while enterprises from other cities and counties were considered the control group. The specific model:

In Equation 1, the subscripts “i” and “t” represent a certain listed company i and the t-th year, respectively.

Following Chen and Chen (2021); Kimura (2024), the explanatory variable GP_appit is set as the enterprise’s green technological innovation capability, measured by the number of green patent applications. It can effectively capture the output of green technology innovation activities of enterprises, and is the official certification of a certain quality of innovation achievements.

The core explanatory variable is the interaction term of aquatic ecological civilization city construction, represented as DIDit = Policyi × Postt, where the explanatory variable Policyi is a dummy variable for the pilot area. If the city or county is part of the first two batches of pilot areas established by the policy, it is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is 0. Postt is a dummy variable for pre and post-policy pilot periods. Considering the temporal differences in policy implementation, the variable takes a value of 1 during the pilot period and 0 otherwise. For the first batch of pilot cities, Postt = 1 when t ≥ 2013, and 0 otherwise. Similarly, for the second batch of pilot cities, Postt = 1 when t ≥ 2014, and 0 otherwise. The enterprise is the treatment group (DIDit = 1) only when an enterprise is located in a pilot city (Postt = 1) and in the year following policy implementation (Postt). In all other cases—including the years before policy implementation for the treatment group and all years for the control group—it is the control group.

The coefficient β1 signifies the impact of the policy on enterprise green technological innovation. Xit represents control variables at the listed company level influencing technological innovation. μi denotes enterprise fixed effects, λt represents year fixed effects, and εit is the error term.

3.2 Variable descriptions

3.2.1 Environmental regulation intensity variables

Following Yong and Jianmin, 2015, the environmental protection investment ratio (Eri1) is used to measure the intensity of environmental regulation. Eri1 = Environmental Governance Investment/Main Business Income. A higher value indicates stronger environmental regulation impact on the enterprise. Referring to García (2007), the environmental regulation intensity is assessed using the environmental information disclosure quality related to chemical oxygen demand from listed companies’ social responsibility reports (Eri2). The measurement method for Eri2 is as follows: 2 points for disclosing quantified information, 1 point for disclosing qualitative information, and 0 points for no disclosure. A higher disclosure quality indicates stronger environmental regulation intensity.

3.2.2 Enterprise financial constraint variables

Referencing Kim and Park. (2017), Equation 2 is used to calculate the enterprise financing constraint SA index (Cfc1). Drawing from Whited and Wu. (2005), Equation 3 is employed to assess the robustness of the enterprise financing constraint WW index (Cfc2). Enterprise size (lnSize) is represented by the logarithm of total asset size, while enterprise operating years (Age) are indicated by the difference between the observation year and the establishment year of the enterprise. The cash flow ratio (CF) is the ratio of net cash flows from operating activities to total assets. The cash dividend payment dummy variable (CDP) is set to 1 if cash dividends are distributed in the observation year and 0 otherwise. The enterprise total debt ratio (ALR) is the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. ISG and SG represent the average sales growth rate of the industry to which the enterprise belongs and the sales revenue growth rate of the enterprise, respectively. Based on Equations 2, 3, the financing constraint SA index (Cfc1) and WW index (Cfc2) are derived. A higher index value indicates a more severe degree of financial constraint on the enterprise.

3.2.3 Control variables

The Tobin’s Q value (ln_TobinQ) is represented by the logarithm of the ratio of enterprise market value to asset replacement cost. It reflects the company’s growth potential and future investment opportunities. The enterprises with high growth rate are more likely to carry out technological innovation and respond to the government’s green policy to shape a good image, so it is necessary to control the growth rate of enterprises to separate the pure effect of the policy itself.

Enterprise debt (ln_Debts) is represented by the logarithm of the ratio of the current year’s loan amount to total assets. It measures the leverage level and financial risk of enterprises, and enterprises with high debt level may be unable to respond to the policy requirements for green innovation. If debt is not controlled, the policy’s role in promoting green innovation may be overshadowed by companies unable to innovate due to high debt.

Capital intensity (Cap_ int) is represented by the ratio of total assets to operating income. It reflects the nature of the production function of enterprises. Capital intensity may systematically influence the ability and willingness of an industry or enterprise to carry out green technology innovation, and it must be controlled.

The proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder (Lar_ sha) is represented by the ratio of the shareholding of the largest shareholder to the total share capital. The proportion of independent directors (Ind_dir) is represented by the ratio of the number of independent directors to the total number of board members. They are all the core corporate governance factors that influence the innovation decision-making of enterprises. The better the governance structure of an enterprise, the stronger the internal motivation of the enterprise to respond to environmental policies and to carry out green innovation.

The return on total assets (ROTA) is represented by the ratio of net profit to total assets. Strong profitability is the foundation for enterprises to carry out any form of innovation. We must control for this to ensure that observed policy effects are not driven simply by the correlation that more profitable firms are more willing to innovate.

3.3 Data sources and processing

3.3.1 Construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities

From 2012 to 2014, the Ministry of Water Resources established 105 pilot cities, including 79 prefecture-level cities, 16 county-level cities, and 10 districts (counties). This study focuses on enterprises at the prefecture-level city level, excluding counties and autonomous regions with missing data. Additionally, since Jinan became a pilot city in October 2012, it is included in the 2013 pilot phase. Therefore, the policy implementation period is 2013 and 2014.

3.3.2 Enterprise green technological innovation

This study selects patent data from A-share listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets in China from 2010 to 2018 as the research object (Yang et al., 2021).8 To accurately identify green patents of listed companies, this study adopts a comprehensive retrieval strategy that combines International Patent Classification (IPC) with keywords. The specific steps are as follows: Firstly, preliminary screening is conducted based on the IPC classification number. We strictly follow the “International Patent Classification and Green Technology List” published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in 2010, extract all IPC group codes corresponding to the seven major green technology fields (i.e., transportation, waste management, energy conservation, alternative energy production, administrative regulation and design, agriculture and nuclear power), and retrieve potential green patents from the total number of patents of listed companies. Secondly, refine keywords based on patent text information. To address the potential noise or omissions in relying solely on IPC classification, we have constructed a Chinese English keyword library covering various green technology fields based on the preliminary results mentioned above (such as “energy conservation”, “emission reduction”, “photovoltaics”, “wastewater treatment”, “renewable energy”, “carbon capture”, etc.), and conducted secondary searches and manual checks in the title and abstract fields of patents. Ultimately, a patent is only recognized as a green patent if it meets the IPC criteria and its textual information clearly points to the theme of green technology. In terms of patent types, Chinese patent applications are divided into three categories: invention type, utility type, and design type. Given that invention patents and utility patents better reflect substantive technological innovation, this article mainly selects green invention patents and green utility patents for calculation and analysis, and adds them up to obtain the total number of green patent applications for each company in each year as the core explanatory variable.

3.4 Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics of the main variables are shown in Table 1. It can be observed that the average values of the total number of green patent applications, green invention patent applications, and green utility model patent applications are 2.979, 1.742, and 1.236 respectively. The standard deviations are 20.026, 12.882, and 8.132, indicating significant variations in the number of green patent applications among different enterprises, reflecting diverse levels of green innovation within the sample.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Baseline regression results

In this section, the dependent variables are successively set as the total number of green patent applications (GP_app), the number of green invention patent applications (GIP_app), and the number of green utility model patent applications (GUP_app). A multi-period difference-in-differences model is used to test the impact of aquatic ecological civilization city construction on enterprise green technological innovation. The baseline regression results are shown in Table 2. Regression analyses are adjusted for clustered standard errors at the city level. When control variables are not included, the coefficients in columns (1) and (3) are significantly positive at the 1% level, and the coefficient in column (5) is significantly positive at the 5% level. After including control variables, the coefficients in columns (2) and (4) remain significantly positive at the 1% level, and the coefficient in column (6) is significantly positive at the 5% level. The impact of aquatic ecological civilization city construction on green utility model patents is relatively weaker, while the incentive effect on green invention patents is more pronounced. In the long run, increasing investment in green invention patents with higher technological levels is crucial for transitioning pollution-intensive enterprises into environmentally friendly enterprises. Additionally, the estimated coefficients in different regressions show improvement compared to the results without control variables, indicating the necessity of including control variables for a precise analysis of policy effects. In conclusion, research hypothesis H1 is supported.

4.2 Parallel trends test

The prerequisite for ensuring the consistency of estimates in the multi-period difference-in-differences model is that the treatment group and the control group adhere to the parallel trends assumption. Referring to the event study method by Li et al.(2016), we examine the parallel trends and dynamic effects of aquatic ecological civilization city construction. In Equation 4, Dit represents the dummy variable for the pilot policy implementation in 2013 and 2014, where θ-τ signifies the impact on enterprise green technological innovation before policy implementation, and θ+τ denotes the impact after policy implementation. As indicated in Figure 4, before policy implementation, there is no significant difference in the effects of enterprise green technological innovation between the treatment group and the control group. And the estimates before policy implementation are not significant, indicating no influence on enterprise green technological innovation, thus suggesting that the parallel trends assumption before policy implementation is valid.

Figure 4. Parallel Trends Test. The horizontal axis represents the relative year of policy implementation, the vertical axis represents the regression coefficient, which is the dynamic effect of the policy, and the vertical line interval represents the 95% confidence interval.

4.3 Placebo test

To eliminate the interference of random factors and omitted variables, we conducted a placebo test following the references of Shen and Jin (2018) and Yu et al.(2023). In 2013 and 2014, 39 and 40 prefecture-level cities respectively served as pilot cities for the construction of aquatic ecological civilization. We randomly selected 2 years as pilot years from 2010 to 2018. The first random selection involved 39 politically affected prefecture-level cities without replacement, and the second selection included 40 cities, ensuring that the virtual experimental group resembled the actual data structure. This process was repeated 500 times. As shown in Figure 5, the estimated coefficients after regression are distributed evenly on both sides of the coefficient of 0, while the baseline regression coefficient of 1.6620 is significantly far from the probability density curve indicated by the vertical dashed line. Thus, there is a significant difference between the distribution of regression coefficients from the 500 repetitions of random experiments and the baseline regression coefficient, indicating that the treatment effect of the policy is not caused by random factors.

Figure 5. Placebo Test. The horizontal axis represents the relative year of policy implementation, the vertical axis represents the regression coefficient, which is the dynamic effect of the policy, and the vertical line interval represents the 95% confidence interval.

4.4 Robustness test

This paper conducted robustness tests in four aspects:

First, using the Propensity Score Matching with Difference-in-Differences (PSM-DID) method. The selection of aquatic ecological civilization city pilots may not be random but determined based on regional economic and water resource conditions. This could lead to differences between the treatment and control groups. To avoid sample self-selection bias, this paper employed the propensity score matching method to match the treatment and control groups based on similar characteristics. Considering the policy’s multi-period nature, three methods—nearest neighbor matching, radius matching, and kernel matching—were used to annually match the treatment and control groups based on the characteristics of listed companies. As shown in Table 3, the regression results remain robust.

Second, using the method of replacing the dependent variable. Referring to Fang and Li (2024), the number of green patent applications was replaced with the number of green patent grants (GP_aut). Table 4 indicates that the coefficient is significantly positive at the 5% level. Although the significance level has decreased, this could be attributed to China’s strict patent application process, which takes one to 2 years from application to grant.

Third, excluding other policy interferences. Other policies during the process of aquatic ecological civilization city construction may affect enterprise green technological innovation. To eliminate these influences and ensure the persuasiveness of the regression results, this paper excluded the interference of low-carbon city policies. The low-carbon city pilot policy starting in 2010 may impact the regression results. Therefore, interaction terms of low-carbon city pilot and time dummy variables were added in Equation 1 for multi-period difference-in-differences regression. As shown in Table 5, the regression results remain robust.

Fourth, excluding data from directly governed cities. The economic conditions and policy resources of directly governed cities differ significantly from other prefecture-level cities. Directly governed cities have more economic policy and technological resources support, and the central government enforces stricter environmental regulations on them, potentially making them more prone to stimulate green technological innovation. Hence, pilot construction data from directly governed cities were excluded to avoid influencing the research results. As shown in Table 6, the regression results remain robust.

In conclusion, the empirical test results are consistent with the baseline regression results, indicating that the construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities indeed promotes enterprise green technological innovation, and the robustness of the baseline conclusion has been verified.

4.5 Heterogeneity analysis

4.5.1 Industry water pollution intensity

Although the construction of water ecological civilization cities will regulate both water-polluting intensive and non-intensive industries, these two types of industries have significant differences in technological composition and pollution emissions. This paper believes that the main target of regulation in the construction of water ecological civilization cities is the water-polluting intensive industries. The production costs and emission reduction costs of this industry will increase with the improvement of policy requirements. It is urgent to grasp the direction of technological change to enhance corporate innovation and avoid being eliminated by strict regulatory requirements. In addition, the production costs and emission reduction costs of non-water-polluting intensive industries are not greatly affected by the increase in regulatory intensity, and the policy’s promotion effect on green technology innovation in this type of industry is relatively weak. Based on the numerical values of chemical oxygen demand emissions in various industries as reported in the “First National Pollutant Source Census Bulletin”, the industries are categorized into water-polluting intensive industries and non-intensive industries9. Table 7 shows that in water-polluting intensive industries, the construction of water ecological civilization cities has a significant promoting effect on corporate green technology innovation, with the coefficient being significantly positive at the 1% level; however, the promotion effect of policies on green technology innovation in non-water-polluting intensive industries is not significant.

4.5.2 Ownership of enterprises

The promotion effect of water ecological civilization city construction on corporate green technology innovation may vary depending on the type of enterprise ownership. Non-state-owned enterprises, mainly private enterprises, focus more on market competition and usually do not adjust their R&D strategies promptly due to policy changes. They may reduce environmental regulatory costs by relocating to areas with relaxed environmental policies. On the other hand, state-owned enterprises respond quickly to new environmental policies and strive for long-term maximization of economic benefits. Due to their large fixed assets, the relocation costs of state-owned enterprises far exceed R&D costs, so they are more inclined to increase R&D investment for green technology innovation. Overall, state-owned enterprises need to balance economic, environmental, and social benefits, while non-state-owned enterprises primarily focus on economic benefits. Therefore, the promotion effect of water ecological civilization city construction on green technology innovation in state-owned enterprises may be more significant. Publicly listed companies are classified into state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises based on the nature of equity. Table 8 shows that in state-owned enterprises, the construction of water ecological civilization cities significantly promotes corporate green technology innovation, with a positive significant level of 1%; however, the promotion effect on non-state-owned enterprises is not significant.

4.5.3 Regional heterogeneity

The promotion effect of water ecological civilization city construction on corporate green technology innovation may vary depending on the type of the East, Central, and Western Region. The differences are mainly due to the imparities of water resources endowment, economic development foundation, policy implementation and industrial agglomeration level in different regions. The eastern region has better resource endowment and more perfect market mechanism. At the same time, it has gathered the top universities, research institutes and talents in China, which can provide strong knowledge and technology spillover effect for enterprises’ green innovation. The central region is in the middle and late stages of industrialization. It has received industrial transfers from the east and is also under great pressure to upgrade traditional industries. The construction of water ecological civilization cities provides a clear signal and standard for its transformation, compelling enterprises to break away from the old path of high energy consumption and high pollution through green technological innovation and enhance their competitiveness. However, many enterprises in the western regions are small in scale and have thin profits. Survival is the top priority. The construction of water ecological civilization cities means strict environmental protection standards, expensive investment in sewage treatment facilities, and higher operating costs. This directly increases their production and compliance costs, squeezing out the limited funds that could have been used for production expansion or general technological innovation. This thus suppressed its technological innovation capacity in the short term. Table 9 shows that in the eastern and central regions, the construction of water ecological civilization cities has significantly promoted the green technological innovation of enterprises, with a positive significant level of 1%, but the impact on the eastern region is greater. However, in the western regions, the construction of water ecological civilization cities has significantly restrained the green technological innovation of enterprises.

5 Mechanism analysis

5.1 Strengthening environmental regulatory strength

Referencing Yang et al. (2021), a model is constructed to analyze the impact of water ecological civilization city construction on the strength of environmental regulations. In Equation 5, the dependent variable Eriit represents the strength of environmental regulations, measured using two methods. Table 10 reports the regression results of Equation 5. The coefficient in the first column is significantly positive at the 1% level, and in the second column, it is significantly positive at the 10% level. After the policy implementation, both enterprise’s investment in environmental governance and their social responsibility for environmental governance have significantly increased. This is because the environmental regulatory strength imposed on enterprises has become stricter, leading to increased attention to water environmental governance by enterprises, increased environmental protection investment, and ultimately promoting green technology innovation in enterprises. In conclusion, research hypothesis H2 is supported.

5.2 Alleviating corporate financing constraints

Referring to Yu et al. (2021), a model is constructed to analyze the impact of water ecological civilization city construction on corporate financing constraints. In Equation 6, the dependent variable Cfcit represents corporate financing constraints, measured using two methods. Table 10 reports the regression results of Equation 6. The coefficient in the first column is significantly negative at the 1% level, and in the second column, it is significantly negative at the 5% level. After the policy implementation, both the SA index and WW index calculations show a significant decrease in the level of corporate financing constraints. This is because with increased external social capital support, the pressure of financing constraints on enterprises is greatly reduced, allowing for more funds to be allocated to research and development innovation, ultimately promoting green technology innovation in enterprises. In conclusion, research hypothesis H3 is supported.

6 Conclusion and policy recommendations

During the crucial period of promoting Chinese-style modernization and achieving green development, enhancing green technological innovation in enterprises has become a key focus of both policy and academic attention (Zhao et al., 2025). The Chinese government promotes green technological innovation through environmental regulations to achieve the strategic goal of ecological civilization construction. With the continuous depletion of water resources and the deterioration of water ecosystems, water environment governance and water ecological protection have become extremely urgent. This article regards the pilot policy for the construction of water ecological civilization cities as a quasi-natural experiment and takes the green technological innovation of enterprises as the research object. Based on the panel data of green patents of Chinese listed companies from 2010 to 2018, this paper, on the basis of theoretical analysis and empirical testing, adopts a multi-period difference-in-differences model to identify the impact and mechanism of this policy on the green technological innovation of enterprises.

The research results show that: Firstly, the construction of water ecological civilization cities has significantly promoted the green technological innovation of enterprises. The significance of the research conclusion was verified based on a series of robustness tests, including parallel trend tests, placebo tests, propensity score matching method, replacement of explained variables, exclusion of other policy interferences, and exclusion of municipalities directly under the Central Government. Secondly, from the dual perspectives of the concentration of water pollution in industries and the ownership of enterprises, it is found that the construction of water ecological civilization cities has a more significant promoting effect on water-intensive industries and state-owned enterprises. Finally, from the dual perspectives of the intensity of environmental regulation and the financing constraints of enterprises, it is found that strengthening the intensity of environmental regulation and alleviating the financing constraints of enterprises are important channels for the construction of water ecological civilization cities to influence the green technological innovation of enterprises. Based on the research conclusions, the following policy suggestions are put forward:

First, expand the scope of pilot projects for water ecological civilization city construction and promote the institutionalization and normalization of experience. Pilot experience shows that the construction of water ecological civilization cities can effectively promote green technological innovation in enterprises, thereby facilitating the coordinated development of ecological civilization construction and green economic growth. Under the premise of clarifying the pilot goals and implementation paths, power should be moderately delegated to grant local governments greater autonomy, enabling them to formulate differentiated plans in light of local resource endowments and industrial structures. Policymakers should promptly summarize typical cases, distill replicable and scalable institutional experiences, and promote the regular operation of water ecological civilization city construction on a larger scale, providing institutional support for achieving the goal of a “Beautiful China”.

Second, optimize industry regulatory policies and promote the green transformation and upgrading of highly polluting industries. We find that the effect of water ecological civilization city construction is more significant in water pollution intensive industries and state-owned enterprises. For industries with a high concentration of water pollution, more targeted guidance plans for clean production and green innovation should be formulated to encourage enterprises to increase investment in original and inventive patents and achieve breakthroughs in core technologies. While promoting the green transformation of state-owned enterprises, more attention should be paid to the issue of clean technology upgrading of non-state-owned enterprises to prevent them from making a passive choice of “exit” rather than “transformation” under the pressure of environmental regulations. By improving the water resources management system, raising the industry entry threshold and strictly implementing the pollutant discharge permit system, a long-term mechanism for the green transformation of highly polluting industries will be gradually formed.

Third, strengthen green incentives and financing support to form a policy synergy. We find that the construction of water ecological civilization city promotes green technology innovation by strengthening environmental regulation and alleviating the financing constraints of enterprises. Local governments should, while strictly enforcing environmental regulations, increase positive incentive measures such as fiscal subsidies, tax reductions and exemptions, and green credit, extend the cycle of enterprises’ green R&D investment, and enhance their motivation for continuous innovation. In particular, it is necessary to enhance financing support for non-state-owned enterprises, reduce their financial constraints during the green transformation process, and prevent insufficient green technological innovation due to financing difficulties. Meanwhile, efforts should be made to promote the formation of a diversified green investment system with government guidance, enterprises as the main body and active participation of social capital, and give full play to the multiplier effect of policy tools in stimulating enterprises’ green innovation.

Fourth, improve the green evaluation and assessment mechanism to ensure the long-term effectiveness of policies. The paper finds that the policy of water ecological civilization city construction is a core engine that can accurately stimulate market vitality, effectively allocate financial resources, and ultimately drive high-quality economic development. To prevent the implementation of policies from being merely a formality, a performance evaluation system for green technological innovation should be established and improved. Indicators such as the output of green patents by enterprises, the effectiveness of emission reduction, and the efficiency of resource utilization should be incorporated into the assessment framework for local governments and enterprises. Through information disclosure and social supervision mechanisms, enhance the external constraints and reputation incentives for enterprises’ green innovation, and form a market-oriented and law-based long-term mechanism, thereby ensuring the coordinated advancement of water ecological civilization city construction and enterprises’ green technological innovation.

Although the study reveals the impact of water ecological civilization policy on green technological innovation for enterprises, it still has limitations. Future research can be conducted from three directions: Firstly, the research sample is limited to listed companies, which are larger in scale, richer in resources and more under regulatory attention, and cannot represent the majority of small, medium and micro enterprises. The scope of research can be further expanded in the future. Secondly, the data in this paper is up to 2018 and does not observe the long-term dynamic effects of the policy. The short-term incentive effect and long-term guiding effect of green technology innovation may be different. We can further investigate the long-term effects of the policy after the full implementation of the policy in 2018. Furthermore, the paper analyzes the synergistic effects of water ecological civilization policy with other major green policies, such as “dual carbon” strategy, circular economy demonstration city and zero waste city.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. ZW: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. HZ: Formal Analysis, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research project is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Beijing Language and Culture University (24SZ03) is Ruixuan Gao’ s project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Chen, A., and Chen, H. (2021). Decomposition analysis of green technology innovation from green patents in China. Math. Problems Eng. 1, 6672656. doi:10.1155/2021/6672656

Fang, L., and Li, Z. (2024). Corporate digitalization and green innovation: evidence from textual analysis of firm annual reports and corporate green patent data in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 33 (5), 3936–3964. doi:10.1002/bse.3677

García, J. (2007). Essays on asymmetric information and environmental regulation through disclosure. Gothenburg, Sweden: Göteborg University.

Guo, B., Hu, P., and Lin, J. (2025). A study on the impact of water resource tax on urban water ecological resilience. Water Econ. Policy 11 (03), 2440003. doi:10.1142/s2382624x24400034

Haoyi, W., Huanxiu, G., Bing, Z., and Maoliang, B. (2017). Westward movement of new polluting firms in China:Pollution reduction mandates and location choice. J. Comp. Econ. 45 (45), 119–138. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2016.01.001

Kim, J., and Park, J. (2017). How do financial constraint and distress measures compare. Invest. Management and Financial Innovations 12, 41–50.

Kimura, Y. (2024). Market-based patent value of green transformation technologies. Finance Res. Lett. 68 (2024), 106004. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2024.106004

Li, P., Lu, Y., and Wang, J. (2016). Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 123, 18–37. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.07.002

Liu, D., Wang, K., and Liu, J. (2024). Can social trust foster green innovation? Finance Res. Lett. 66 (2024), 105644. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2024.105644

Lou, Y., Tian, Y., and Tang, X. (2020). Does environmental regulation improve an enterprise’s productivity? evidence from China’s carbon reduction policy. Sustainability 12 (17), 6742. doi:10.3390/su12176742

Minatour, Y., Bonakdari, H., and Aliakbarkhani, Z. S. (2016). Extension of fuzzy Delphi AHP based on interval-valued fuzzy sets and its application in water resource rating problems. Water Resour. Manage 30, 3123–3141. doi:10.1007/s11269-016-1335-5

Muhammad, S., Hoffmann, C., and Müsgens, F. (2025). Assessing energy security risks: implications for household electricity prices in the EU. Energy 327, 136201. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.136201

Nie, C., Li, R., Feng, Y., and Chen, Z. (2023). The impact of China’s energy saving and emission reduction demonstration city policy on urban green technology innovation. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 15168. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-42520-4

Pei, T., Huaqing, W., Tiantian, Y., Faliang, J., Wenjie, Z., Zhanliang, Z., et al. (2021). Evaluation of urban water ecological civilization: a case study of three urban agglomerations in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Ecol. Indic. 123 (4), 107351. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107351

Porter, M. E., and van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9 (4), 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Shen, K., and Jin, G. (2018). The policy effects of environmental governance by local governments in China: a study based on the evolution of the “river chief system”. Chin. Soc. Sci. (05), 92–115+206. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dzw7IdLhHkGD8tAJXa74VVu6YdPKybUnn40dr_YESXKyqcWomtKwgfqtstnyEHn60B1296F-eQIZczSNDI36xfi_zynViADQcBiGNKy16jly4bK22nLZzoNVi8r-zwE0PbAsHELtNjTKAJqdZcg1MupYis5QvKsSZw4lJURjCd-MhoU9h9ld-g==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

Su, C., Deng, Z., Li, L., Wen, J. x., and Cao, Y. f. (2021). Spatial pattern evolution and convergence of water eco-civilization development index in China. J. Nat. Resour. 36 (05), 1282–1301. doi:10.31497/zrzyxb.20210515

Sun, Y., and Fei, J. (2021). Measurement, sources of differences, and causes of green production efficiency in heavily polluting enterprises. China population. Resour. Environ. 31 (11), 102–109. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dzw7IdLhHkG9FiUKXYgmD0RAv_9JOP1U55wKSADXNOa8KWacCCnwtyUxc5UbpKWAWjpBsx_D5yivLfAty1FYQg5HkRK5EUPAtJSttN8KjL1SxIVrK0kRkRgUMfrVzHfFTB8izxL_8UUPaA5nslPoWLIfvEimuQAYq67oiczRzlRMTve3hzCbGQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

Takalo, S. K., Tooranloo, H. S., and Shahabaldini Parizi, Z. (2021). Green innovation: a systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod., 279:122474, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122474

Tang, X., Zhang, Q., Li, C., Zhang, H., and Xu, H. (2024). Can civilized City construction promote enterprise green innovation? Sustainability 16 (8), 3496. doi:10.3390/su16083496

Whited, T., and Wu, G. (2006). Financial constraints risk. Review Financial Studies 19 (2), 531–559. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhj012

Yang, Q., Gao, D., Song, D., and Li, Y. (2021). Environmental regulation, pollution reduction and green innovation: the case of the Chinese Water Ecological Civilization City Pilot policy. Econ. Syst. 45 (4), 100911. doi:10.1016/j.ecosys.2021.100911

Yang, Q., Xu, Q., and Chen, X. (2022). Regional disparities and convergence test of green productivity of total factor water resources in China. Finance Trade Res. 33 (05), 15–30. doi:10.19337/j.cnki.34-1093/f.2022.05.002

Yong, W., and Jianmin, L. (2015). Measurement of environmental regulation Intensity, Potential problems and its correction. Collect. Essays Finance Econ. 31 (5), 98. doi:10.13762/j.cnki.cjlc.2015.05.013

Yu, J., Shi, X., Guo, D., and Yang, L. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and firm carbon emissions: evidence using a China provincial EPU index. Energy Econ. 94, 105071. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2020.105071

Yu, J., Liu, P., Shi, X., and Ai, X. (2023). China’s emissions trading scheme, firms’ R&D investment and emissions reduction. Econ. Analysis Policy 80, 1021–1037. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2023.09.039

Zhang, M., Liu, Y., Wu, J., and Wang, T. (2018). Index system of urban resource and environment carrying capacity based on ecological civilization. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 68, 90–97. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2017.11.002

Keywords: construction of aquatic ecological civilization cities, enterprise financial constraints, enterprise green technological innovation, stringency of environmental regulations, water-smart food production

Citation: Gao R, Wang Z and Zhao H (2025) Aquatic ecological civilization in cities and green technological innovation for enterprises. Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1737166. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1737166

Received: 03 November 2025; Accepted: 26 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Nils Ekelund, Malmö University, SwedenReviewed by:

Bingnan Guo, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, ChinaSulaman Muhammad, Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg, Germany

Yuanyu Guo, Guangzhou College of Commerce, China

Copyright © 2025 Gao, Wang and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zenan Wang, d2FuZ3poZWxhbjExMjBAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Ruixuan Gao1

Ruixuan Gao1 Zenan Wang

Zenan Wang Haifeng Zhao

Haifeng Zhao