Abstract

Forest ecosystems play a crucial role as natural carbon (C) sinks, and preserving this function is key to mitigating climate change. However, the forest C dynamics, particularly those related to the production and turnover of fine roots (<2 mm in diameter), remain largely unclear. Here, we examined the age of C in fine roots in a cool-temperate Japanese beech forest by measuring the natural abundance of radiocarbon (14C). Root samples were collected and categorized by diameter size class and live/dead status. Newly emerged roots were also obtained using an ingrowth mesh bag method. The mean ages of C in existing fine roots were estimated to be 5–23 years for live roots and 1–34 years for dead roots, respectively. In contrast, the 14C signatures of newly emerged roots indicated the use of current-year photosynthetic products for new root production. Given the negligible time lag between photosynthetic C fixation and the use of the fixed C for new root production, the observed ages for live fine root C suggest that plants use current-year photosynthetic products to produce new roots but utilize older (14C-enriched) internally stored C to support subsequent root growth, and/or that some fine roots live for many years. The age of live fine root C increased with diameter size class and branch order in branching root systems, supporting both of these processes. Our results provide a piece of knowledge to comprehensively understand belowground C allocation processes in plants and highlight that tracking changes in the 14C signature of fine roots, as well as root biomass, in relation to root development stages would be beneficial for separating these processes and quantifying the heterogeneity of fine root dynamics, encompassing both ephemeral and long-lived roots.

1 Introduction

Forest ecosystems, the largest terrestrial reservoir of carbon (C) in the global C cycle, are crucial in regulating the Earth’s climate (Pan et al., 2011; IPCC, 2022). Forest ecosystems absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere through primary production and store the absorbed C as live (plant biomass) and dead (soil) organic material over extended periods (Binkley and Fisher, 2020). The global gross C sink of forests is 3.6 Pg C y−1 (Pan et al., 2024), which represents roughly half of the annual global CO2 emission from fossil fuel combustion (Harris et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2024). As climate change risks escalate due to human activities, the potential of forest ecosystems to mitigate climate change through C offsets has gained significant global attention (van Kooten and Johnston, 2016). However, this potential of forest C sequestration remains highly uncertain, mainly due to a lack of quantitative evaluation of C dynamics in forest ecosystems (Pugh et al., 2020). An improved understanding of these C dynamics is essential for maintaining and enhancing the C sink function of forests as a nature-based solution for mitigating climate change.

Plant biomass produced through net primary production (NPP) is allocated to both aboveground (stem, branches, and leaves) and belowground (root crown and lateral roots) biomass. This biomass allocation is a key factor in assessing the C sequestration potential of forest ecosystems. Although biomass allocation patterns reflect plant growth, survival, and adaptation strategies, and are largely influenced by climatic, ecological, and nutrient conditions (Qi et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2022), studies have consistently shown that plants allocate a significant proportion (>30%) of NPP to the production and growth of fine roots (diameter: <2 mm) belowground (Jackson et al., 1997; Matamala et al., 2003; Fernandez-Tschieder et al., 2024). Fine roots, being a dynamic component of the plant root system, play a crucial role in the forest C dynamics through belowground C input, cycling, and the formation of soil organic matter (SOM) (Trumbore and Gaudinski, 2003). However, knowledge about belowground biomass dynamics is still lacking because unlike aboveground processes, belowground processes are hidden and thus difficult to observe directly.

Many studies based on direct observation have used ingrowth cores, sequential soil coring, minirhizotrons, and litter bags to establish fine root dynamics (biomass and neuromas as well as rates of production, turnover, and decomposition after death) in various forest ecosystems (Gill and Jackson, 2000). Fine root lifetimes vary from days to years (Eissenstat and Yanai, 1997; McCormack et al., 2012; Ding et al., 2019), depending on factors such as soil depth (Burton et al., 2000), root diameter size class (Gill and Jackson, 2000), root branch order (Eissenstat et al., 2000; McCormack et al., 2015), and environmental conditions (Kwatcho Kengdo et al., 2023; Conroy et al., 2025). Fine root lifetimes of a few years are typically estimated based on conventional steady-state mass balance calculations (i.e., by dividing the biomass of fine live roots by the annual rate of fine root production determined through direct observation) (Gill and Jackson, 2000; Tierney and Fahey, 2002; Noguchi et al., 2007). While soil microbes rapidly decompose a significant portion of dead fine roots within months, the remainder is decomposed slowly over years (Sun et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2022). However, because of methodological limitations, these direct observation approaches primarily focus on the most dynamic part of fine roots (i.e., typically apical, ephemeral first-order roots) and struggle to capture the full picture of fine root dynamics, especially for larger, more highly branched fine roots (Guo et al., 2008; Pritchard and Strand, 2008). A key limitation is the difficulty in achieving long-term, continuous, in situ monitoring of root growth and death for the whole root system.

Isotopic approaches, utilizing radiocarbon (14C) measurements of fine root tissues, offer a valuable tool for evaluating the belowground C allocation processes in plants (Gaudinski et al., 2001; Trumbore and Gaudinski, 2003; Pritchard and Strand, 2008). The 14C content of CO2 in the atmosphere nearly doubled in the early 1960s due to the production of 14C (bomb 14C) from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing and has declined gradually since the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963 (Hua et al., 2022). Given this temporal change in the 14C content of atmospheric CO2, the 14C content of roots provides an estimate of how long C has been retained in the plant since the photosynthetic fixation of CO2 from the atmosphere (Gaudinski et al., 2001). Studies based on 14C measurements have revealed that the presence of C in fine roots exceeding 10 years in age (Gaudinski et al., 2001; Trumbore and Gaudinski, 2003; Trumbore et al., 2006; Solly et al., 2018).

Applying only 14C measurements to live fine roots potentially overestimates fine root lifetimes because of two reasons. First, trees can utilize stored C to produce and grow roots (Matamala et al., 2003; Vargas et al., 2009; Sah et al., 2011). Second, isotopic approaches, in contrast to direct observation approaches, tend to focus on larger, higher-branch-order roots, which are more readily collected from soil samples for analysis (Guo et al., 2008; Pritchard and Strand, 2008). Consequently, despite employing various approaches, the dynamics of fine roots—particularly the heterogeneity of the fine root population and its lifetime—remains poorly understood (Gaudinski et al., 2010), representing a significant uncertainty in quantifying forest C dynamics (Pugh et al., 2020; Fernandez-Tschieder et al., 2024). A combination of isotope, ingrowth methods, and fine root classification (Joslin et al., 2006; Solly et al., 2018) can provide a more comprehensive and robust assessment (Gaudinski et al., 2009; Sah et al., 2011).

This study aimed to evaluate the age of C in fine roots using a 14C-based approach to existing fine roots and newly emerged roots. We collected samples of fine root, including branching fine root systems, in a cool-temperate deciduous broadleaved forest in Japan. The root samples were categorized according to diameter size class (linking with branch order) and live/dead status. Additionally, we captured newly emerged fine roots using ingrowth mesh bags installed in the soil for approximately 3 months during the growing season. The root samples were analyzed for 14C content to estimate the age of C in fine roots with different morphological properties.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study site

This study was conducted at the Appi forest meteorological research site (40.00°N, 140.56°E; 825 m above sea level), an Asia Flux observation site in Iwate prefecture, Japan. The forest is dominated by 70–80-year-old Japanese beech (Fagus crenata) with no understory vegetation (Koarashi et al., 2009), and is located in a cool-temperate zone. Permission to collect plant samples was obtained from the Forestry Agency of Japan. Fagus crenata was identified by KN and voucher specimens were deposited at the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (Voucher ID: JAEA-APP001). New leaves of Japanese beech begin expanding in May, and leaf fall occurs in November (Atarashi-Andoh et al., 2012). Mean annual temperature and precipitation are 6.1 °C and 1,207 mm, respectively (Ishizuka et al., 2006). Snow cover occurs from November to May, with a maximum depth of 2 m. The soil is classified as Andosol (Ishizuka et al., 2006) and stores ~11 kg C m−2 of C as soil organic C in the upper 20 cm of mineral soil (Koarashi et al., 2009). Plant roots are mostly present in the upper 25 cm of the soil (Nakanishi et al., 2012).

Annual net ecosystem production (NEP) and heterotrophic respiration (CO2 emission through microbial decomposition of SOM) at the Appi forest site have been reported as 312 ± 64 g C m−2 y−1 (Yasuda et al., 2012) and 497 g C m−2 y−1 (Atarashi-Andoh et al., 2012), respectively, which were measured in 2000–2006 using the eddy covariance method and in 2007–2008 using the closed chamber method with 14C-based source partitioning, respectively. Hence, at this site, NPP can be estimated to be ~810 g C m−2 y−1. The fine root production rate of 233 ± 35 g m−2 y−1 (N = 12) was evaluated for the upper 20 cm soil layer using a net sheet method from October 2012 to October 2013 (Noguchi et al., unpublished data).

2.2 Root sampling

Root samples were collected using the following three investigations to assess depth-, diameter-, live/dead statist-, and age-related variations in fine-root 14C signatures. The first investigation was conducted in July 2005 to determine the mass and 14C signatures of fine roots (<2 mm in diameter) by depth. After the litter layer was removed, two soil cores were obtained from the mineral soil surface using a core sampler (5 cm in diameter and 20 cm in length) (Koarashi et al., 2009). The soil cores were frozen and divided into 2-cm-thick layers in the laboratory, and soil samples were dried at 50 °C. All visible fine roots in the soil samples were collected using tweezers. The root samples were processed via ultrasonic washing in ultrapure water to remove adherent soil particles, dried at 50 °C, and weighed. The root samples collected in this investigation were not classified into live and dead roots but were considered bulk (mixed live and dead) root samples.

Building on the depth profiles obtained in the first investigation (see section of Results), the second investigation was conducted in May 2007 to explore potential influences of diameter-size classes and live/dead status of roots on 14C signatures. This investigation aimed to determine the mass and 14C signatures of roots by diameter size class and live/dead status. A soil core was obtained in the same manner as that in the first investigation, but a larger core sampler (9.5 cm in diameter and 25 cm in length) was used because it has the advantage of collecting intact branching root systems. The soil core was frozen and divided into five layers at a 5-cm depth interval in the laboratory. Soil samples were defrosted, immersed, and dispersed in water trays. All visible roots were collected and sorted based on the diameter size class (<0.5, 0.5–1, 1–2, and 2–5 mm in diameter) and live/dead status of roots. Root diameter was measured using a ruler. Live and dead roots were distinguished based on color, density, tensile strength, and surface texture (Joslin et al., 2006; Vargas et al., 2009).

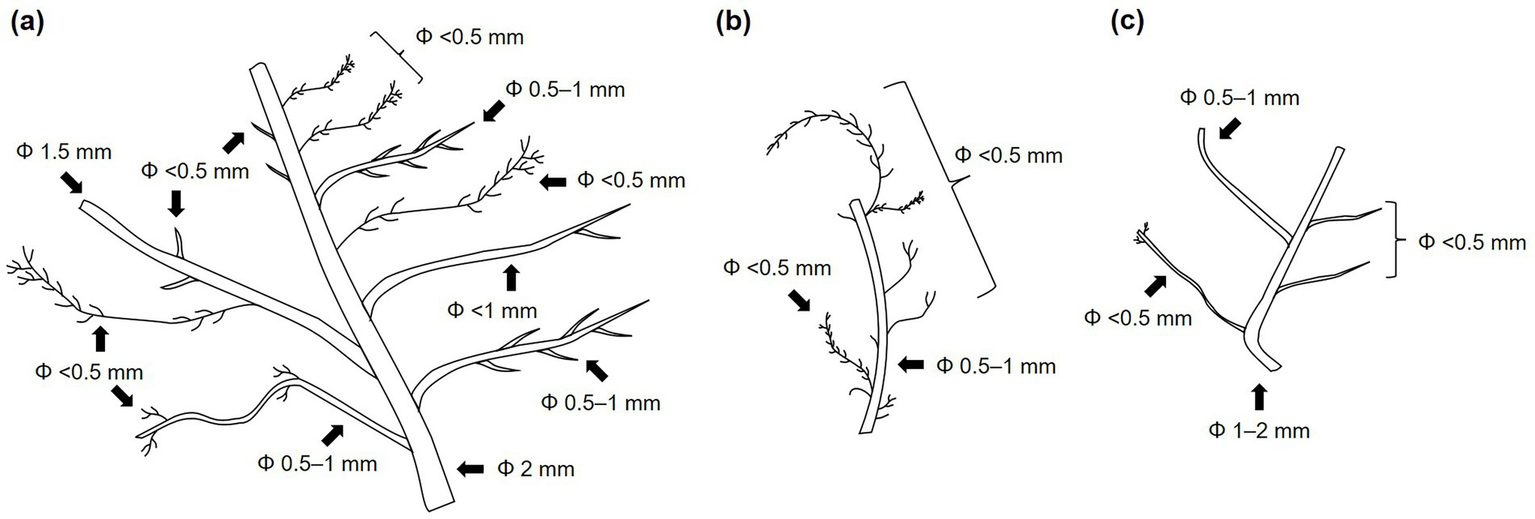

In the second investigation, we collected four and five portions of branching fine root systems from 0 to 5- and 5–10-cm layers of the soil core, respectively. Three examples of branching fine root systems are illustrated in Figure 1. For 14C analysis of live roots, we used samples from fine root systems, as these roots are living and enable the evaluation of 14C results by linking diameter size class with the branch order of roots in a live-root system. Roots were collected separately according to the diameter size class from each root system. However, obtaining a sufficient amount of root samples for 14C analysis for each diameter size class from a single branching root system was challenging. Therefore, root samples from multiple root systems were mixed to make a composite sample for each diameter size class. Roots separated into <0.5-, 0.5–1-, and 1–2-mm diameter size classes comprised first- and second-order roots, second- and third-order roots, and third- and fourth-order roots, respectively. The root samples were ultrasonically washed, dried, and weighed as previously described.

Figure 1

Illustrations showing branching of live fine-root systems excavated from the 0–5-cm (a) and 5–10-cm (b,c) soil layers.

The third investigation was conducted in 2008 using ingrowth mesh bags to trap newly emerged fine roots and determine their 14C signatures. Six ingrowth mesh bags were prepared, of which three were filled with root-free sand, two with perlite (an amorphous volcanic glass), and one with fine-glass beads. The ingrowth mesh bag measured roughly 5 cm in diameter and 40 cm in length. The bags were placed between the litter and mineral soil layers on July 30 and retrieved on November 6 (99 days after installation). Only roots (or root segments) located inside the bags were collected, ultrasonically washed, and dried in the laboratory.

2.3 Radiocarbon analysis

The 14C content of root samples was measured following the method described by Koarashi et al. (2009). Briefly, root samples were combusted with copper oxide under vacuum, generating CO2. The CO2 was then purified using liquid nitrogen and liquid nitrogen–ethanol slush traps in a vacuum line and subsequently converted into graphite through catalytic reduction with hydrogen gas. The resulting graphite was analyzed for 14C content using an accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) at JAEA-AMS-MUTSU. The measured values of 14C are reported as Δ14C, the per mil (‰) deviation of the 14C/12C ratio of the sample from that of the absolute 14C standard in 1950, with correction for mass-dependent isotopic fractionation to a common δ13C value of −25‰ (Stuiver and Polach, 1977). In the AMS-14C measurement, the analytical uncertainty of the Δ14C value was 4–7‰ (at one standard deviation). Soil samples collected in July 2005 were also analyzed for 14C content using the same method.

2.4 Estimating the mean C age of the roots

The mean C age of the roots was estimated based on the 14C signature using two approaches proposed by Gaudinski et al. (2001). The first approach assumes that no new C is supplied to the roots (or root segments) once they are produced. Under this assumption, the mean C age of the roots can be estimated simply by comparing the Δ14C value of roots with the record of Δ14C value of atmospheric CO2 (Gaudinski et al., 2001; Vargas et al., 2009; Sah et al., 2011). 14C data reported by Hua et al. (2022) for the northern hemisphere (zone 2) were used as the record of the Δ14C value of atmospheric CO2 at the study site.

The second approach assumes that roots consist of multiple roots (or root segments) produced over years, with each segment turning over at the same rate (i.e., they have the same production and mortality rates). Under this assumption, the mean C age of the roots can be estimated using a time-dependent, steady-state, single-pool model (Gaudinski et al., 2001; Trumbore et al., 2006; Solly et al., 2013) as follows:where Froot(t) is the fraction modern of C (FMC; equivalent to Δ14C/1,000 + 1) in root C at year t; Fatm(t) is the FMC in CO2 in the atmosphere at year t, Froot(t − 1) is the FMC in root C at year t − 1, k is the turnover time (y−1) for root C, and λ is the radioactive decay constant for 14C (1.21 × 10−4 y−1). In this model, the atmospheric Δ14C record of CO2 reported by Hua et al. (2022) was used as Fatm(t) values for the period 1950–2007.

Hence, the relationships between the mean age and Δ14C value of root C were derived based on the two approaches, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). The estimates of the C age of the roots in 2007 were consistent between the two approaches for age <16 years, as reported by other studies (Gaudinski et al., 2001; Trumbore et al., 2006; Fröberg, 2012). The second approach (Equation 1) did not provide a unique solution for Δ14C values greater than 161‰ and could not estimate the C age of the roots for these samples. For live roots, the mean C age of the roots estimated using this approach reflects the time elapsed since C was fixed from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, including the period that C was stored in the plant before root production and the time C spent in the live root (Gaudinski et al., 2001). For dead roots, the estimated age also includes the time C resided in the soil after root death. For bulk (mixed live and dead) roots, age may represent the mean turnover time for the C pool of bulk roots (Gaudinski et al., 2001).

3 Results

3.1 Fine root inventory

Two soil cores were collected in July 2005 to determine the depth distribution of bulk fine (<2 mm in diameter) roots (Supplementary Table S1). The total mass of fine roots in the uppermost 20 cm of soil was 1,280–1,490 g m−2, with 55–63% of this mass concentrated within the top 6 cm.

In May 2007, roots were collected from a soil core and sorted based on the diameter size class and live/dead status (Supplementary Figure S2; Supplementary Table S2 for numerical data). The total root mass was measured at 1,175 g m−2 (685 g m−2 for fine roots). Approximately 75% of the total root mass was found within the upper 10 cm of soil. Roots > 2 mm in diameter constituted a significant proportion (42–67%) of total root mass in soil layers from 5 to 20 cm deep. Across all depths, live-root mass consistently surpassed dead root mass, representing approximately 72% (76% for fine roots) of bulk root mass in the soil profile. Among the live fine roots, those 1–2 mm in diameter were the most prevalent, accounting for 42–74% of the mass at all depths. The diameter size distribution of dead fine roots, however, exhibited inconsistent patterns throughout the soil profile. Overall, live roots of <0.5-, 0.5–1-, and 1–2-mm diameter and dead roots of <0.5-, 0.5–1-, and 1–2-mm diameter collectively represented 16, 19, 40, 12, 7, and 5% of the total fine root mass in the whole-soil profile, respectively.

3.2 Age of C in bulk fine roots

For the bulk fine roots excavated in July 2005, Δ14C values were 77–237‰ with the exception of a low Δ14C value of 4‰ for roots from the 4–6-cm layer of soil core 2 (Table 1). These Δ14C values were remarkably higher than the Δ14C value (59‰) for atmospheric CO2 in 2005 (Hua et al., 2022), indicating the influence of bomb 14C. While root Δ14C values were relatively low in the topmost soil layer, they did not show a consistent depth-related trend. This contrasted with SOC Δ14C values, which decreased with depth, reaching negative values (corresponding to the C age of more than several 100 years) below 10 cm (Table 1). Using 14C signatures and two modeling approaches, the mean ages of C in bulk fine roots were estimated to range from 4 to 25 years, except for one sample showing a very old age of >50 years with a low Δ14C value.

Table 1

| Depth (cm) | Soil core 1 | Soil core 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root Δ14C(‰)a | Age of root C (y) | SOC Δ14C (‰)a | Root Δ14C (‰)a | Age of root C (y) | SOC Δ14C (‰)a,b | |

| 0–2 | 77 | 5 [4]c | 126 | 79 | 6 [5]c | 125 |

| 2–4 | 229 | 24 [nad] | 118 | 87 | 7 [6] | 149 |

| 4–6 | 203 | 22 [na] | 49 | 4 | >50 [>50] | 154 |

| 6–8 | 183 | 20 [na] | 16 | 120 | 13 [10] | 68 |

| 8–10 | 209 | 23 [na] | −7 | 136 | 15 [12] | 26 |

| 10–12 | 237 | 25 [na] | −28 | NDe | ND | −23 |

| 12–14 | 234 | 24 [na] | −56 | ND | ND | −44 |

| 14–16 | —f | — | — | ND | ND | −66 |

| 16–18 | — | — | — | ND | ND | −95 |

| 18–20 | — | — | — | ND | ND | −136 |

Δ14C values for bulk (live + dead) fine roots and soil organic carbon (SOC), and age of root carbon in July 2005.

Analytical uncertainty for the Δ14C value was 4–7‰.

Data of SOC Δ14C for soil core 2 are from Koarashi et al. (2009) study.

Mean ages estimated based on Δ14C values using approaches 1 and 2 (in brackets).

na: Not available because of no unique solution to explain the Δ14C value in approach 2.

ND: Not determined because of an insufficient quantity of root sample for AMS-14C measurement.

Soil samples were not collected.

3.3 Age of C in live and dead roots with different size classes

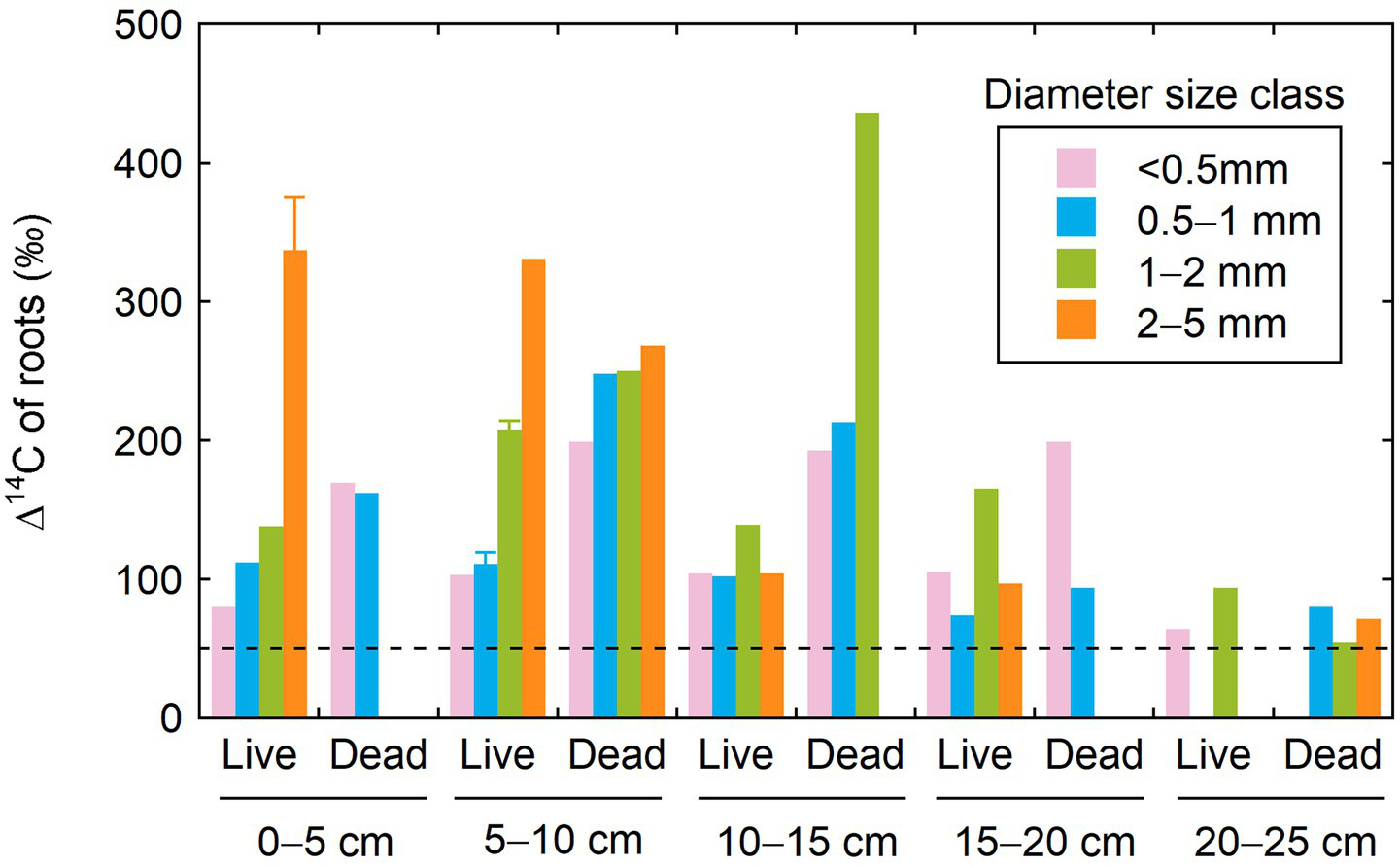

The Δ14C values for live and dead roots, excavated by depth in May 2007 and categorized by diameter size class, ranged from 74 to 436‰ for a depth interval of 0–20 cm (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S3). These Δ14C values were notably higher than the Δ14C value (51‰) for atmospheric CO2 in 2007 (Hua et al., 2022). Both live and dead roots in soil layers >20-cm deep showed lower Δ14C values (54–94‰) compared to those in the upper soil layers. Consistent with the results of 2005 (Table 1), no consistent trend was observed with depth in root Δ14C values for both live and dead roots.

Figure 2

Radiocarbon signatures of roots by depth, diameter size class, and live/dead status in May 2007. Error bars represent standard deviation when replicate samples are available.

Regarding the difference due to the live/dead status, dead roots exhibited higher Δ14C values than live roots (Figure 2). Regarding the difference due to diameter size class, Δ14C value increased with size class for live roots in the surface (0–5 and 5–10 cm) soil layers. This observation should be noted in relation to the root sampling method, as only live roots obtained from branching fine root systems were selected for 14C analysis in these layers (see section of Materials and methods and Figure 1). Such a relationship between the Δ14C value and size class was not found for live roots in other soil layers and for dead roots at all depths.

The mean ages of C in live and dead roots sampled at depths of 0–20 cm were estimated to be 5–32 and 8–34 years, respectively (Table 2) and were generally higher in dead roots (by 3–19 years) than in live roots when compared at the same depth and diameter size class. For the live roots configuring branching fine root systems in 0–10-cm deep surface soil, differences in age between diameter size classes were apparent with larger-sized roots consisting of older C. In contrast, the trend of increasing C age with diameter size class was unclear for live roots from deeper soil layers, which were collected and analyzed as a mixture of root pieces. In the soil layer below a depth of 20 cm, the estimated mean ages of C ranged from 1 to 8 years for live and dead roots.

Table 2

| Depth (cm) | Live roots | Dead roots | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 mm | 0.5–1 mm | 1–2 mm | 2–5 mm | <0.5 mm | 0.5–1 mm | 1–2 mm | 2–5 mm | |

| 0–5 cm | 6 [6]a | 12 [11] | 15 [15] | 28–32 [nab] | 19 [na] | 18 [na] | NDc | —d |

| 5–10 cm | 10 [9] | 10–13 [9–12] | 22–23 [na] | 29 [na] | 21 [na] | 25 [na] | 25 [na] | 26 [na] |

| 10–15 cm | 10 [10] | 10 [9] | 15 [15] | 10 [10] | 21 [na] | 23 [na] | 34 [na] | — |

| 15–20 cm | 11 [10] | 5 [5] | 18 [na] | 9 [9] | 22 [na] | 8 [8] | ND | — |

| 20–25 cm | 3 [4] | ND | 8 [8] | — | ND | 6 [6] | 1 [2] | 4 [5] |

Mean ages of carbon in roots by depth, diameter size class, and live/dead status in May 2007.

Mean ages estimated based on Δ14C values using approaches 1 and 2 (in brackets).

na: Not available because of no unique solution to explain the Δ14C value in approach 2.

nd: Not determined either because of an insufficient quantity of root sample for 14C analysis or because sample preparation for 14C analysis failed.

Root samples were not collected.

3.4 Age of C in newly emerged roots

All fine roots grown in ingrowth mesh bags within a 99-day growing season (July 30, 2008 to November 6, 2008) were observed to be primary roots with less pigmentation (Supplementary Figure S3). Six samples were prepared for 14C analysis (Table 3). Three of the six samples were root samples collected from different filling materials (root-free sand, perlite, and glass beads) in ingrowth mesh bags and generally consisted of a mixture of root pieces from some branching fine root systems. Because a sufficient quantity of roots was obtained from the ingrowth mesh bags of sand, the 14C content was also measured for a single fine live-root system and roots with different diameter size classes (<0.5 and 0.5–1 mm) from some fine live-root systems.

Table 3

| Filling material of ingrowth mesh bag | Root Δ14C (‰)a | Sample details |

|---|---|---|

| Root-free sand | 46 | A mixture of some live fine-root systems |

| 44 | A single live fine-root system | |

| 48 | Live roots with diameter size class of <0.5 mm | |

| 44 | Live roots with diameter size class of 0.5–1 mm | |

| Perlite | 44 | A mixture of some live fine-root systems |

| Glass beads | 45 | A mixture of some live fine-root systems |

Δ14C values for fine roots grown in ingrowth mesh bags from July 30 to November 6, 2008.

Analytical uncertainty for the Δ14C value was approximately 5‰.

Despite the different characteristics of root samples, Δ14C values obtained for the roots were less variable (range: 44–48‰, mean ± standard deviation: 45‰ ± 2‰, Table 3) and similar to the Δ14C value (48‰) for atmospheric CO2 in 2008 (Hua et al., 2022). The 14C signatures indicated that roots growing in the ingrowth mesh bags consisted of C fixed within the year (i.e., mean C age of the roots was <1 year), which matched the age of roots deduced from the duration of the ingrowth bag experiment.

4 Discussion

The global 14C spike resulting from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing, which peaked in the early 1960s, provides a valuable tool for assessing the mean age of root C. The Δ14C values of existing fine roots in the Japanese beech forest consistently exceeded those of contemporary atmospheric CO2 (Table 1; Figure 2), indicating that the roots were formed mainly from old (noncurrent-year) photosynthetic products. Using the 14C signatures and modeling approaches, the mean ages of C in fine roots were estimated to be 5–23, 1–34, and 4–25 years (with an occasional value exceeding 50 years) for live, dead, and bulk roots, respectively (Tables 1, 2). These 14C-derived estimates of fine root C ages align with findings across biomes and plant types. Gaudinski et al. (2001) reported mean ages of 3–18, 10–18, and 3–18 years for live, dead, and bulk fine roots, respectively, in United States temperate forests. Fine root C ages have also been reported as <1 to >40 years in Amazonian tropical forests (Trumbore et al., 2006), 3–12 years in boreal and hemi boreal pine and spruce forests (Sah et al., 2013), and 3–23 years in European temperate, boreal, and subarctic forests (Solly et al., 2018). Recent work by Kwatcho Kengdo et al. (2023) indicates approximately 6-year turnover times for bulk fine roots in the Austrian Alps. Our observation showed no consistent trend with depth in root C ages. This pattern contrasts with other studies showing an increase in root C age with depth (Gaudinski et al., 2001; Joslin et al., 2006). This is likely due to the characteristics of the Appi forest soil (Andosol) where soil bulk density, clay content, organic matter content are uniformly distributed in the upper 20 cm (Koarashi et al., 2009).

In contrast to the C age observed in the standing stock of fine roots, newly produced (99-day-old) fine roots exhibited a Δ14C value similar to that of contemporary atmospheric CO2 (Table 3). This indicates that current-year photosynthetic products are used in the production of new roots in the Japanese beech forest, although the reliance of plants on stored C reserves (e.g., nonstructural carbohydrates) for root production is widely recognized. While Gaudinski et al. (2009) suggested that the production of new roots primarily utilizes stored C, their study of a temperate deciduous oak forest indicated reserves less than 1 year old. Our results align with observations from temperate and tropical forests, where newly emerged roots typically comprise photosynthetic products of age <1–2 years (Gaudinski et al., 2001; Tierney and Fahey, 2002; Trumbore et al., 2006; Vargas et al., 2009; Sah et al., 2011). The use of C reserves in the production of new roots also may depend on the season; in this study, the root collection was conducted in the second half of the growing season (July 30 to November 6), a time when freshly assimilated C reserves are potentially abundant in the tree body (Hilman et al., 2024).

Given the negligible time lag observed between photosynthetic C assimilation and its utilization for root production in the Japanese beech forest, the estimated ages of C in fine roots suggest the following two processes of fine root dynamics. First, plants use current-year photosynthetic products to produce new roots but use older (14C-enriched) internally stored organic compounds to support root growth throughout their lifespan. Second, some fine roots live for many years. Both of these processes could explain why live fine roots exhibited a higher Δ14C value than newly emerged roots.

Regarding the first process, individual roots of woody species undergo primary and secondary growth after emergence. During primary root growth, the primary vascular system and cortex develop, forming a structure largely composed of living parenchyma cells that store starch (Hishi, 2007; Gaudinski et al., 2009). Subsequently, secondary growth leads to the development of the secondary vascular system and cork cambium, resulting in a root structure dominated by structural secondary tissues, such as sclerenchyma, rich in lignin and subring (Hishi, 2007). This shift in root tissue composition raises the hypothesis that trees utilize older C reserves during later root development. The observed increase in 14C-derived age of root C with diameter size class (branch order) in branching root systems (Figure 1 and Table 2) may support this. However, the significant difference in 14C signature between existing and newly emerged root C implies a disproportionally large allocation of old C reserves after root emergence. Monitoring changes in both 14C signature and biomass of fine roots throughout the root lifespan is needed to fully understand this allocation. Solly et al. (2018) have recently reported older 14C ages than chronological (based on annual growth rings) ages of fine roots. In addition, other studies, in contrast to our results, have documented higher C ages even in newly produced roots (up to 10 years), especially for larger-diameter fine roots (Matamala et al., 2003; Sah et al., 2011; Hilman et al., 2024) and those produced following forest disturbance (Vargas et al., 2009). Richardson et al. (2013) identified both rapidly cycling (<1 year) and decade-old nonstructural carbohydrate reserves in temperate forest trees of the northeastern United States. These findings illustrate the capacity of plants to allocate older stored C to root production and growth, especially under specific environmental conditions.

The second process relies on the assumption that plants do not use older stored C for root growth after emergence. If this assumption holds true, the 14C-derived ages of root C would primarily reflect root lifetimes, suggesting that a proportion of existing fine roots are long-lived. For the Appi forest, the 14C method estimates fine root turnover times of over 5 years, significantly longer than approximately 1.9 years estimated by a conventional steady-state mass balance calculation using the fine root biomass (438 g m−2 measured in this study) and production rate (233 ± 35 g m−2 y−1 evaluated during 2012–2013; Noguchi et al. unpublished data). The apparent discrepancy in fine root lifetime could arise from differences in the fine root populations being assessed between the methods (Trumbore and Gaudinski, 2003; Guo et al., 2008; Pritchard and Strand, 2008; Strand et al., 2008). The 14C method relies on a mass-based measure (i.e., mean residence time of fine root mass) and can be skewed by the larger, higher-order fine roots, which contain more C and tend to persist longer than smaller, lower-order fine roots. The difficulty in extracting the most ephemeral components of the fine root system from soil samples could also contribute to this bias (Strand et al., 2008). Conversely, the minirhizotron and ingrowth core methods rely on a number-based measure (growing of individual fine roots) and can be biased by the smaller, apical first-order fine roots, which are more numerous and ephemeral (i.e., short-lived) but contain less C compared to higher-order fine roots. Inherent heterogeneity in root longevity has been documented (Tierney and Fahey, 2002; Guo et al., 2008; Gaudinski et al., 2010; Ahrens et al., 2014), likely due to variations in mortality rates and life cycles across different positions on branching root systems (King et al., 2002; Hishi, 2007). Our observation of increasing 14C-derived age of root C with branch order in branching root systems (Figure 1 and Table 2) may also reflect this inherent variation in root lifespan. Consequently, the 14C method could tend to overestimate the actual lifetime of fine roots, whereas the minirhizotron and ingrowth core methods could substantially underestimate the actual lifetime (Guo et al., 2008). A conventional steady-state mass balance calculation assuming a 1-year lifetime for the standing stock of live fine roots (equivalent to ~260 g C m−2) estimates a belowground NPP share of approximately 32% at the Appi forest. However, this may probably overestimate the belowground C allocation, and consequently, the transfer of C into the soil through fine root dynamics. Again, tracking 14C signatures of roots throughout root development is crucial to definitely verify the assumption and belowground C allocation processes.

Other processes that could potentially influence the 14C signature of roots include the uptake of C by roots from organic C sources in the soil (Jones et al., 2009; Näsholm et al., 2009; Solly et al., 2018) and the transfer of plant-fixed C to mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with the roots (Solly et al., 2018; Hawkins et al., 2023). Regarding the uptake of C by roots, however, the Δ14C values and their depth distribution for fine roots did not match those observed in SOM (Table 1). At the Appi forest site, Δ14C values for water-extractable organic C (WEOC) in the surface soil were measured in 2009 (102‰, 77‰, and 6‰ at depths of 0–5, 5–10, and 10–15 cm, respectively; Nakanishi et al., 2012). The Δ14C values for live roots <1 mm in diameter (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S3) showed a similarity to those for WEOC in the uppermost 10 cm of the soil profile, but diverged in the 10–15 cm layer. The high Δ14C values for live roots >1 mm in diameter did not correspond to the Δ14C values for WEOC, suggesting a limited contribution of organic C sources in the soil to root growth. Regarding the transfer of C to mycorrhizal fungi, mycorrhizal fungi are estimated to receive 4–20% of total NPP (Hawkins et al., 2023) and can constitute up to 40% of the biomass of ectomycorrhizal roots (Harley and McCready, 1952; Satomura et al., 2003). However, research by Hobbie et al. (2002) demonstrated that mycorrhizal fungi incorporated recent photosynthetic, with an estimated age of 0–2 years, using four fungal species in a mature Douglas-fir forest in the United States.

Root morphology and chemical composition vary depending on diameter size and branching position (Hishi, 2007), which also affects their decomposition rate in soils after deposition (Sun et al., 2013; Zhang and Wang, 2015; Wu et al., 2022). The observed difference (3–19 years, with no discernible trends related to depth or diameter class, Table 2) in the mean C age between live and dead roots could reflect the time required for root decomposition in soils before root C returns to the atmosphere, a process to be quantified for accurately assessing the role of roots in soil C cycling, and ultimately, forest C dynamics. Zhang and Wang (2015) found faster decomposition of fine roots compared to course roots in middle latitude areas. Conversely Sun et al. (2013), reported slower decomposition of very fine roots (<0.5 mm in diameter) compared to 0.5–2.0 mm roots in a temperate forest in northeastern China. Goebel et al. (2011) noted that root decomposition can be influenced by root pigmentation and root order; pigmented first- and second-order roots decompose more slowly than higher-order roots. These findings suggest that root decomposition can be complicated depending on morphological traits such as diameter-size class and branch order, which may result in the inconsistent difference in 14C signature between live and dead roots. Many studies rely on buried root techniques and laboratory incubation experiments, potentially misrepresenting actual root decomposition processes (Wu et al., 2022). Root decomposition rates are still controversial, necessitating variable approaches, including 14C methods, for comprehensive assessment.

Overall, our results provide a piece of knowledge about belowground C allocation processes in plants and suggest a further hypothesis. However, the fine root dynamics—encompassing both ephemeral and long-lived roots—remains a critical knowledge gap. Innovative research methods are still needed to reveal the heterogeneity of fine root dynamics in situ. Future studies should include tracking changes in 14C signatures of fine roots and their nonstructural C pools throughout their development, for example in combination with direct monitoring techniques such as minirhizotrons and flatbed scanners, to fully elucidate the role of plants in C dynamics and sequestration within forest ecosystems.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JK: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization. MA-A: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SI: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. KN: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AK: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MN: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant numbers 19510024 and 20710016).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank G. Katata, T. Tsuduki, T. Kobayashi, S. Otosaka, and H. Terada of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) for support with the fieldwork; T. Tanaka and the rest of the staff at the Aomori Research and Development Center of JAEA for the AMS-14C measurements; and S. Miura, T. Saito, T. Hashimoto, Y. Yasuda, K. Ono, and D. Hoshino of the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute (FFPRI) for valuable discussions. The authors also thank the Iwatehokubu District Forest Office and the Forestry Agency’s Tohoku Regional Forest Office for providing permission to use the Appi forest site. This work was performed according to the JAEA-FFPRI Cooperation Research Scheme.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2025.1654883/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Ahrens B. Hansson K. Solly E. F. Schrumpf M. (2014). Reconcilable differences: a joint calibration of fine-root turnover times with radiocarbon and minirhizotrons. New Phytol.204, 932–942. doi: 10.1111/nph.12979

2

Atarashi-Andoh M. Koarashi J. Ishizuka S. Hirai K. (2012). Seasonal patterns and control factors of CO2 effluxes from surface litter, soil organic carbon, and root-derived carbon estimated using radiocarbon signatures. Agric. For. Meteorol.152, 149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.09.015

3

Binkley D. Fisher R. F. (2020). Ecology and management of forest soils. 5th Edn. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

4

Burton A. J. Pregitzer K. S. Hendrick R. L. (2000). Relationships between fine root dynamics and nitrogen availability in Michigan northern hardwood forests. Oecologia125, 389–399. doi: 10.1007/s004420000455

5

Conroy B. M. Kelleway J. J. Rogers K. (2025). Toot productivity contributes to carbon storage and surface elevation adjustments in coastal wetlands. Plant. Soil513, 605–631. doi: 10.1007/s11104-025-07204-0

6

Ding Y. Leppälammi-Kujansuu J. Helmisaari H.-S. (2019). Fine root longevity and below- and aboveground litter production in a boreal Betula pendula forest. For. Ecol. Manag.431, 17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.039

7

Eissenstat D. M. Wells C. E. Yanai R. D. Whitbeck J. L. (2000). Building roots in a changing environment; implications for root longevity. New Phytol.147, 33–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00686.x

8

Eissenstat D. M. Yanai R. D. (1997). The ecology of root life span. Adv. Ecol. Res.27, 1–62. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60005-7

9

Fernandez-Tschieder E. Marshall J. Binkley D. (2024). Carbon budget at the individual-tree scale: dominant Eucalyptus trees partition less carbon belowground. New Phytol.242, 1932–1943. doi: 10.1111/nph.19764

10

Fröberg M. (2012). Residence time of fine-root carbon using radiocarbon measurements of samples collected from a soil archive. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci.175, 46–48. doi: 10.1002/jpln.201100072

11

Gaudinski J. B. Torn M. S. Riley W. J. Dawson T. E. Joslin J. D. Majdi H. (2010). Measuring and modeling the spectrum of fine-root turnover times in three forests using isotopes, minirhizotrons, and the Radix model. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles24:GB3029. doi: 10.1029/2009GB003649

12

Gaudinski J. B. Torn M. S. Riley W. J. Swanston C. Trumbore S. E. Joslin J. D. et al . (2009). Use of stored carbon reserves in growth of temperate tree roots and leaf buds: analyses using radiocarbon measurements and modeling. Glob. Change Biol.15, 992–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01736.x

13

Gaudinski J. B. Trumbore S. E. Daidson E. A. Cook A. C. Markewitz D. Richter D. D. (2001). The age of fine-root carbon in three forests of the eastern United States measured by radiocarbon. Oecologia129, 420–429. doi: 10.1007/s004420100746

14

Gill R. A. Jackson R. B. (2000). Global patterns of root turnover for terrestrial ecosystems. New Phytol.147, 13–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00681.x

15

Goebel M. Hobbie S. E. Bulaj B. Zadworny M. Archibald D. D. Oleksyn J. et al . (2011). Decomposition of the finest root branching orders: linking belowground dynamics to fine-root function and structure. Ecol. Monogr.81, 89–102. doi: 10.1890/09-2390.1

16

Guo D. Li H. Mitchell R. J. Han W. Hendricks J. J. Fahey T. J. et al . (2008). Fine root heterogeneity by branch order: exploring the discrepancy in root turnover estimates between minirhizotron and carbon isotopic methods. New Phytol.177, 443–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02242.x

17

Harley J. L. McCready C. C. (1952). The uptake of phosphate by excised mycorrhizal roots of the beech. III. The effect of the fungal sheath on the availability of phosphate to the core. New Phytol.51, 342–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1952.tb06141.x

18

Harris N. L. Gibbs D. A. Baccini A. Birdsey R. A. de Bruin S. Farina M. et al . (2021). Global maps of twenty-first century forest carbon fluxes. Nat. Clim. Chang.11, 234–240. doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-00976-6

19

Hawkins H.-J. Cargill R. I. M. Van Nuland M. E. Hagen S. C. Field K. J. Sheldrake M. et al . (2023). Mycorrhizal mycelium as a global carbon pool. Curr. Biol.33, R560–R573. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.027

20

Hilman B. Solly E. F. Hagedon F. Kuhlman I. Herrera-Ramírez D. Trumbore S. (2024). 14C-age of carbon used to grow fine roots reflects tree carbon status. Plant Cell Environ. 1–15. doi: 10.1111/pce.70154

21

Hishi T. (2007). Heterogeneity of individual roots within the fine root architecture: causal links between physiological and ecosystem functions. J. For. Res.12, 126–133. doi: 10.1007/s10310-006-0260-5

22

Hobbie E. A. Weber N. S. Trappe J. M. van Klinken G. J. (2002). Using radiocarbon to determine the mycorrhizal status of fungi. New Phytol.156, 129–136. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00496.x

23

Hua Q. Turnbull J. C. Santos G. M. Rakowski A. Z. Ancapichún S. De Pol-Holz R. et al . (2022). Atmospheric radiocarbon for the period 1950–2019. Radiocarbon64, 723–745. doi: 10.1017/RDC.2021.95

24

IPCC (2022). “Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability” in Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. eds. PörtnerH. O.et al. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

25

Ishizuka S. Sakata T. Sawata S. Ikeda S. Takenaka C. Tamai N. et al . (2006). High potential for increase in CO2 flux from forest soil surface due to global warming in cooler areas of Japan. Ann. For. Sci.63, 537–546. doi: 10.1051/forest:2006036

26

Jackson R. B. Mooney H. A. Schulze E.-D. (1997). A global budget for fine root biomass, surface area, and nutrient contents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA94, 7362–7366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7362

27

Jones D. L. Nguyen C. Finley R. D. (2009). Carbon flow in the rhizosphere: carbon trading at the soil–root interface. Plant Soil321, 5–33. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-9925-0

28

Joslin J. D. Gaudinski J. B. Torn M. S. Riley W. J. Hanson P. J. (2006). Fine-root turnover patterns and their relationship to root diameter and soil depth in a 14C-labeled hardwood forest. New Phytol.172, 523–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01847.x

29

King J. S. Albaugh T. J. Allen H. L. Buford M. Strain B. R. Dougherty P. (2002). Below-ground carbon input to soil is controlled by nutrient availability and fine root dynamics in loblolly pine. New Phytol.154, 389–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00393.x

30

Koarashi J. Atarashi-Andoh M. Ishizuka S. Miura S. Saito T. Hirai K. (2009). Quantitative aspects of heterogeneity in soil organic matter dynamics in a cool-temperate Japanese beech forest: a radiocarbon-based approach. Glob. Change Biol.15, 631–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01745.x

31

Kwatcho Kengdo S. Ahrens B. Tian Y. Heinzle J. Wanek W. Schindlbacher A. et al . (2023). Increase in carbon input by enhanced fine root turnover in a long-term warmed forest soil. Sci. Total Environ.855:158800. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158800

32

Matamala R. Gonzàlez-Meler M. A. Jastrow J. D. Norby R. J. Schlesinger W. H. (2003). Impacts of fine root turnover on forest NPP and soil C sequestration potential. Science302, 1385–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1089543

33

McCormack M. L. Adams T. S. Smithwick E. A. H. Eissenstat D. M. (2012). Predicting fine root lifespan from plant functional traits in temperate trees. New Phytol.195, 823–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04198.x

34

McCormack M. L. Dickie I. A. Eissenstat D. M. Fahey T. J. Fernandez C. W. Guo D. et al . (2015). Redefining fine roots improves understanding of below-ground contributions to terrestrial biosphere processes. New Phytol.207, 505–518. doi: 10.1111/nph.13363

35

Nakanishi T. Atarashi-Andoh M. Koarashi J. Saito-Kokubu Y. Hirai K. (2012). Carbon isotopes of water-extractable organic carbon in a depth profile of forest soil imply a dynamic relationship with soil carbon. Eur. J. Soil Sci.63, 495–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2389.2012.01465.x

36

Näsholm T. Kielland K. Ganeteg U. (2009). Uptake of organic nitrogen by plants. New Phytol.182, 31–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02751.x

37

Noguchi K. Konôpka B. Satomura T. Kaneko S. Takahashi M. (2007). Biomass and production of fine roots in Japanese forests. J. For. Res.12, 83–95. doi: 10.1007/s10310-006-0262-3

38

Pan Y. Birdsey R. A. Fang J. Houghron R. Kauppi P. E. Kurz W. A. et al . (2011). A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science333, 988–993. doi: 10.1126/science.1201609

39

Pan Y. Birdsey R. A. Phillips O. L. Houghton R. A. Fang J. Kauppi P. E. et al . (2024). The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature631, 563–569. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07602-x

40

Pritchard S. G. Strand A. E. (2008). Can you believe what you see? Reconciling minirhizotron and isotopically derived estimates of fine root longevity. New Phytol.177, 278–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02335.x

41

Pugh T. A. M. Rademacher T. Shafer S. L. Steinkamp J. Barichivich J. Beckage B. et al . (2020). Understanding the uncertainty in global forest carbon turnover. Bio. Geosci17, 3961–3989. doi: 10.5194/bg-17-3961-2020

42

Qi Y. Wei W. Chen C. Chen L. (2019). Plant root-shoot biomass allocation over diverse biomes: a global synthesis. Glob. Ecol. Conserv.18:e00606. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00606

43

Richardson A. D. Carbone M. S. Keenan T. F. Czimczik C. I. Hollinger D. Y. Murakami P. et al . (2013). Seasonal dynamics and age of stemwood nonstructural carbohydrates in temperate forest trees. New Phytol.197, 850–861. doi: 10.1111/nph.12042

44

Sah S. P. Bryant C. L. Leppälammi-Kujansuu J. Lõhmus K. Ostonen I. Helmisaari H.-S. (2013). Variation of carbon age of fine roots in boreal forests determined from 14C measurements. Plant Soil363, 77–86. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1294-4

45

Sah S. P. Jungner H. Oinonen M. Kukkola M. Helmisaari H.-S. (2011). Does the age of fine root carbon indicate the age of fine roots in boreal forests?Biogeochemistry104, 91–102. doi: 10.1007/s10533-010-9485-7

46

Satomura T. Nakatsubo T. Horikoshi T. (2003). Estimation of the biomass of fine roots and mycorrhizal fungi: a case study in a Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora) stand. J. For. Res.8, 221–225. doi: 10.1007/s10310-002-0023-x

47

Solly E. F. Brunner I. Helmisaari H.-S. Herzog C. Leppälammi-Kujansuu J. Schöning I. et al . (2018). Unravelling the age of fine roots of temperate and boreal forests. Nat. Commun.9:3006. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05460-6

48

Solly E. Schöning I. Boch S. Müller J. Socher S. A. Trumbore S. E. et al . (2013). Mean age of carbon in fine roots from temperate forests and grasslands with different management. Bio. Geosci10, 4833–4843. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-4833-2013

49

Strand A. E. Pritchard S. G. McCormack M. L. Davis M. A. Oren R. (2008). Irreconcilable differences: fine-root life spans and soil carbon persistence. Science319, 456–458. doi: 10.1126/science.1151382

50

Stuiver M. Polach H. A. (1977). Reporting of 14C data. Radiocarbon19, 355–363. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200003672

51

Sun T. Mao Z. Han Y. (2013). Slow decomposition of very fine roots and some factors controlling the process: a 4-year experiment in four temperate tree species. Plant Soil372, 445–458. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1755-4

52

Tierney G. L. Fahey T. J. (2002). Fine root turnover in a northern hardwood forest: a direct comparison of the radiocarbon and minirhizotron methods. Can. J. For. Res.32, 1692–1697. doi: 10.1139/x02-123

53

Trumbore S. Da Costa E. S. Nepstad D. C. De Camargo P. B. Martinelli L. A. Ray D. et al . (2006). Dynamics of fine root carbon in Amazonian tropical ecosystems and the contribution of roots to soil respiration. Glob. Change Biol.12, 217–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01063.x

54

Trumbore S. E. Gaudinski J. B. (2003). The secret lives of roots. Science302, 1344–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1091841

55

van Kooten G. C. Johnston C. M. T. (2016). The economics of forest carbon offsets. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ.8, 227–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-resource-100815-095548

56

Vargas R. Trumbore S. E. Allen M. F. (2009). Evidence of old carbon used to grow new fine roots in a tropical forest. New Phytol.182, 710–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02789.x

57

Wu Y. Zhang M. Cheng Z. Wang F. Cui X. (2022). Root-order-associated variations in fine-root decomposition and their effects on soil in a subtropical evergreen forest. Ecol. Process.11:48. doi: 10.1186/s13717-022-00393-x

58

Yasuda Y. Saito T. Hoshino D. Ono K. Ohtani Y. Mizoguchi Y. et al . (2012). Carbon balance in a cool-temperate deciduous forest in northern Japan: seasonal and interannual variations, and environmental controls of its annual balance. J. For. Res.17, 253–267. doi: 10.1007/s10310-011-0298-x

59

Zhang X. Wang W. (2015). The decomposition of fine and coarse roots: their global patterns and controlling factors. Sci. Rep.5:09940. doi: 10.1038/srep09940

60

Zhou L. Zhou X. He Y. Fu Y. Du Z. Lu M. et al . (2022). Global systematic review with meta-analysis shows that warming effects on terrestrial plant biomass allocation are influenced by precipitation and mycorrhizal association. Nat. Commun.13:4914. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32671-9

Summary

Keywords

fine root turnover, age of carbon in fine roots, radiocarbon (14C) signature, diameter size class, belowground allocation processes, forest carbon dynamics

Citation

Koarashi J, Atarashi-Andoh M, Ishizuka S, Noguchi K, Kadono A and Nakayama M (2025) Radiocarbon-derived ages of carbon in live, dead, and newly emerged fine roots in a cool-temperate Japanese beech forest. Front. For. Glob. Change 8:1654883. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2025.1654883

Received

27 June 2025

Accepted

23 October 2025

Published

20 November 2025

Volume

8 - 2025

Edited by

Yunting Fang, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), China

Reviewed by

Sun Tao, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), China

Tõnu Oja, University of Tartu, Estonia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Koarashi, Atarashi-Andoh, Ishizuka, Noguchi, Kadono and Nakayama.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun Koarashi, koarashi.jun@jaea.go.jp

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.