Abstract

Introduction:

The widespread decline of forests across many countries has prompted governments to implement various measures aimed at conserving forest resources. In the Bontioli Total and Partial Wildlife Reserves, however, effective forest conservation remains a challenge, despite the state’s promotion of participatory management approaches.

Methods:

This study employed a diachronic analysis of satellite imagery spanning from 1991 to 2024 to assess land use dynamics, complemented by a qualitative survey involving 150 participants, comprising 26 institutional stakeholders and 124 community members, selected through a combination of random and purposive sampling across four villages. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions and analyzed using mixed thematic coding (both inductive and deductive) with NVivo 14 software.

Results:

Spatial analysis revealed a steady pattern of deforestation, marked by significant agricultural expansion and a reduction in natural vegetation, primarily driven by human activities. Stakeholder perceptions indicated broad awareness of deforestation and its ecological consequences. However, the study also highlighted notable divergences between local communities and authorities in their understanding of concepts such as deforestation and conservation. While community members acknowledged their contribution to environmental degradation, they largely attributed responsibility to external actors and the weakening of traditional authority structures. They also expressed a need for greater institutional recognition and support to align conservation efforts with local development priorities.

Discussion:

The study concludes by recommending inclusive governance models grounded in sociocultural values, along with the development of economically viable alternatives to foster stronger community participation in conservation. Nevertheless, as these findings pertain specifically to the Bontioli forest, further research should be conducted in other classified forest areas to support broader and more comparative analyses.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, the accelerated degradation of forest resources has prompted many governments to adopt restoration and conservation policies (Lapola et al., 2023). In Burkina Faso, forests, particularly those classified by the state, continue to experience sustained degradation (Dimobe et al., 2015; Yameogo et al., 2019). According to the Rapport sur l’état de l’environnement au Burkina Faso [REEB - 5] (2024), the average annual deforestation rate in Burkina Faso is estimated at 1.15%. This situation arises from a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors, including climate change, agricultural expansion, extensive livestock grazing, illegal logging, forest fires, and the excessive use of pesticides (Belem et al., 2018; Ouattara et al., 2022). Forest cover (% of land area) in Burkina Faso was estimated at 31.6% in 2022 (World Bank, 2022). In terms of loss, Burkina Faso lost nearly half of its forests in a 30-year period (1992–2014) (World Bank, 2022). In response to this alarming loss of forest cover, the government has intensified its efforts to safeguard forest resources by promoting participatory management policies in several forest areas, aimed at involving local populations in forest governance (Coulibaly-Lingani, 2011). This approach seeks to align local livelihood needs with forest conservation objectives (Coulibaly-Lingani, 2011; Ouedraogo, 2018; Sibiri et al., 2024). To enhance forest protection, initiatives such as the redefinition of protected area boundaries and the establishment of monitoring and surveillance mechanisms have been implemented to maintain forest ecosystem services (PACO/IUCN, 2009). Despite these measures, unsustainable practices, including the overexploitation of timber and artisanal gold mining, continue to undermine long-term forest management efforts (Yelkouni, 2004; PACO/IUCN, 2009; Traoré, 2019).

A significant body of research has highlighted the strong dependence of local communities on natural forest resources in Burkina Faso, emphasizing the vital ecosystem services forests provide in sustaining rural livelihoods (Devineau et al., 2009; Paré et al., 2010). At the same time, several studies have reported the rapid degradation of forested landscapes, attributing this trend to multiple drivers and underscoring the substantial ecological, social, and economic implications across the country’s forest zones (Kiribou et al., 2024). Among the most critical threats identified are climate change and the overharvesting of certain plant species, which jeopardize the long-term sustainability of forest ecosystems (Gaisberger et al., 2017; Adjognon et al., 2019). This creates a fundamental tension between the short-term survival needs of local populations and the broader imperative of ecological preservation.

In this context, Michon (2003) offers a more nuanced interpretation by arguing that deforestation should not be viewed solely as an act of environmental destruction. The author posits that concepts such as “forest,” “deforestation,” and “conservation” are inherently subjective, and that these conceptual ambiguities shape both how forest issues are perceived and how conservation is implemented, ultimately complicating forest governance. Faced with this complexity, a crucial question arises: in a context like that of Burkina Faso, where forest reserves are essential to the survival of rural populations, what are the main transitions and evolutions of land cover in the Bontioli protected areas (partial and total) between 1991 and 2024? More precisely, how do different local communities (stakeholders) perceive the state, determining factors and conservation measures of the forest? And how do local perceptions agree or diverge with the observed spatial dynamics of the forest?

While numerous studies have explored forest management challenges (Bouda et al., 2011), local perceptions of forest degradation (Etongo et al., 2018), drivers of forest loss (Dimobe et al., 2015), the effectiveness of joint forest management (Ouattara et al., 2022), and forest policy frameworks (Wong et al., 2024), the present study offers a broader analytical perspective. Its primary scientific contribution lies in its integrative methodological approach, which combines spatial and socio-institutional analyses. Specifically, the study employs cartographic and remote sensing techniques to examine long-term land-use changes in the Bontioli forest (1991–2024), while also investigating how local communities (farmers, herders, village committee representatives, traditional authorities, local institutional actors including youth, elders and women) and state actors perceive and interact with forest conservation efforts.

By linking spatial analysis with social representations of the Bontioli forest, this research provides a more comprehensive understanding of its transformation over time. It further highlights the roles, perspectives, and potential contributions of local communities in the conservation of rural forest ecosystems. The findings offer valuable insights into shaping sustainable forest management strategies, particularly in protected areas facing intense anthropogenic pressures (Dimobe et al., 2015).

2 Empirical, theoretical and analytical framework of the study

2.1 Empirical framework

2.1.1 Dependence of local communities on forests

Across much of Africa, rural communities maintain a deep and essential connection with forests, which constitute a vital foundation for their livelihoods (Somorin, 2011; Akomaning et al., 2023; Ampadu and Yang, 2024). Indeed, the concept of “non-timber forest products,” although there is no real consensus on its definition, has been used for several years to group together a wide range of products, such as leaves, fruits, bark, bulbs, caterpillars (Smith-Hall and Chamberlain, 2023). In addition to these resources, there are woody resources, including firewood and construction materials (Aleru et al., 2025). These woody and non-woody forest products serve both subsistence and commercial functions, contributing directly to household income and food security (Amusa et al., 2024). Beyond their material contributions, forests play a critical role in regulating the climate, conserving soil, and maintaining biodiversity, thereby strengthening the ecological and economic resilience of rural landscapes (Ouedraogo et al., 2013). This reliance is particularly pronounced in West African rural societies, where non-timber forest products (NTFPs) hold a central place in cultural traditions, diets, and local economies (Amusa et al., 2024). Women are central to the collection, processing, and commercialization of these products, making vital contributions to both the social cohesion and economic well-being of their households and communities (Ouedraogo et al., 2013).

Burkina Faso exemplifies the multifaceted nature of forest dependence. Whether in rural or urban contexts, forest resources are critical not only for food but also for essential ecological services such as shading, erosion control, and microclimate regulation (Cissé et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2020). Forests supply deadwood for household energy needs, edible wild plants, and a rich variety of medicinal species used in traditional medicine to treat approximately twenty different health conditions (Ouedraogo et al., 2013; Zizka et al., 2015; Cissé et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2020).

This increasing dependence, however, raises serious concerns, as forest resources face growing degradation due to intensifying anthropogenic pressures (Etongo et al., 2018). Considering this, it is essential to reassess and update our understanding of the dynamics of forest degradation and the nature of the pressures exerted on these ecosystems. Addressing this need constitutes the first objective of the present study: to conduct a spatio-temporal analysis of the Bontioli forest, a vital ecological resource for surrounding communities. Updating this knowledge is critical for evaluating the current intensity of human-induced pressures on the forest and informing efforts aimed at its sustainable conservation.

2.1.2 Concern about forests in Burkina-Faso

Beyond the visible reduction in forest cover, forests in Burkina Faso are increasingly affected by more insidious yet equally alarming forms of degradation (Gaisberger et al., 2017; Adjognon et al., 2019). This is evidenced by the gradual deterioration in the structure, functioning, and species composition of forest ecosystems, processes largely driven by human activities such as selective logging, excessive fuelwood collection, overgrazing, and uncontrolled bushfires (Thompson et al., 2013; Ghazoul et al., 2015; Vásquez-Grandón et al., 2018). Such degradation compromises the capacity of forests to provide essential ecosystem services, including climate regulation, biodiversity conservation, and soil fertility, thereby increasing the vulnerability of the communities that depend on them. In many cases, primary forests have been replaced by secondary growth, which is typically less species-diverse and more ecologically fragile (Chokkalingam and Jong, 2001).

The challenge of sustainable forest management is further complicated by the diversity of interests and perceptions surrounding forest ecosystems. While the scientific community often views deforestation and degradation as urgent threats linked to biodiversity loss, climate change, and the destabilization of socio-ecological systems (Aleixandre-Benavent et al., 2018; Baruah and Barua, 2019; Mammadova et al., 2022), local populations may regard forests primarily as sources of livelihood, spaces of cultural identity, or avenues for development (Michon, 2003; Michon et al., 2003). These divergent viewpoints, shaped by distinct patterns of use, cultural beliefs, and land tenure arrangements, complicate efforts to develop conservation strategies that are broadly accepted and locally applicable (Fox, 2000; Michon, 2003; Fernández-Montes de Oca et al., 2021).

Consequently, forest degradation should not be understood solely as an ecological issue; rather, it must be seen as the outcome of complex and evolving relationships between human societies and forest ecosystems. This recognition calls for integrated and inclusive approaches to forest governance (Neaman, 1994; Michon et al., 2003; Williams, 2006). In this context, there is an urgent need to reassess the effectiveness of existing forest management systems and to critically examine the actual impact of conservation measures implemented across different regions.

2.2 Theoretical model of management of common goods: case of forest resources

Common goods are typically defined as resources collectively utilized by a community of users (Combes et al., 2016). These resources are not privately owned but are instead governed under shared sovereignty arrangements (Walker et al., 2022). Forest resources exemplify this category of common goods. One of the central challenges associated with such resources is the tendency toward overuse and degradation, as observed in numerous forest ecosystems (Thompson et al., 2013; Ghazoul et al., 2015; Vásquez-Grandón et al., 2018). In response, forest conservation is often conceptualized as the protection of forest ecosystems to preserve their ecosystem services for both current and future generations (Soni, 2023). However, this conservationist framing frequently remains disconnected from the everyday realities of local communities, whose primary concerns revolve around securing immediate access to energy, food, and income. For instance, in Myanmar’s Bago Yoma region, conservation is understood by local residents primarily through the lens of food and energy security, with their participation in conservation efforts depending largely on the economic benefits received, such as opportunities for income generation (Soe and Yeo-Chang, 2019). A similar pattern is observed in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Burkina Faso, where rural populations often prioritize agricultural land over forested areas, thereby limiting their engagement with conventional conservation strategies (Pouliot et al., 2012).

This divergence in priorities underscores the importance of integrating local perceptions into forest management frameworks. Participatory governance, which promotes the active involvement of diverse stakeholders, including local communities, in the stewardship of natural resources, has emerged as a critical strategy for ensuring the success of conservation initiatives. In this context, community forest management (CFM) has gained increasing prominence worldwide over recent decades as a model aimed at aligning conservation goals with local development needs (Friman, 2024).

Despite their promise, CFM schemes have often failed to meet expectations in terms of both reducing forest degradation and improving local livelihoods (Galvin et al., 2018). Although originally intended to harmonize forest conservation with the equitable distribution of benefits, numerous studies have highlighted the limitations of CFM in practice (Friman, 2024). In many settings, CFM has led to unintended outcomes such as heightened social inequalities, intra-community conflict, and perceptions of injustice in rural areas (Shackleton et al., 2010; Chomba et al., 2015; Hajjar et al., 2021). These shortcomings often stem from a failure to consider local socio-political dynamics, asymmetric power relations, identity-based claims, and entrenched gender inequalities (Galvin et al., 2018; Karambiri and Brockhaus, 2019; Friman, 2024).

Consequently, forest governance cannot rely on standardized or externally designed models that neglect the sociocultural and political particularities of each context. As Friedman et al. (2020) emphasize, the mixed outcomes of participatory approaches underscore the need for context-sensitive analyses that incorporate customary governance systems, indigenous knowledge, and localized power structures. In this regard, place-based studies, such as the present research conducted in the areas surrounding the Bontioli classified forest, are essential to identifying the enabling factors, barriers, and perceptions that shape community–forest relationships. These localized insights are critical for designing adaptive management frameworks that are both socially acceptable and ecologically sustainable in the long term. This imperative forms the foundation of the present study.

2.3 Analytical framework

Figure 1 illustrates the analytical framework of this study, highlighting the interactions among its core components. The research adopts a dual and complementary approach that combines environmental assessment with social analysis. The first component involves a spatio-temporal analysis of land use changes in the Bontioli forest, aimed at quantifying anthropogenic pressures and assessing the degree of ecosystem degradation. This phase provides a robust empirical foundation for understanding environmental transformations over more than three decades. The second component consists of a qualitative investigation into local perceptions, examining how both community members and political actors interpret these environmental changes. This analysis explores stakeholders’ views on the current condition of the forest, their understanding of conservation challenges, and the motivations driving intensive resource use. It also captures the level of environmental awareness among local actors and documents the adaptation strategies they have adopted in response to emerging ecological constraints.

FIGURE 1

Analytical framework of the study. Perceptions on: current situation of the forest, understanding of conservation issues, motivations for intensive farming.

By engaging both local communities and policymakers, the study is anchored in a framework of polycentric and participatory governance, aligning with contemporary paradigms of forest resource management. Ultimately, the integration of ecological data and social perceptions enables the identification of practical, context-specific pathways for the sustainable and inclusive management of the Bontioli forest.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Description of the study area

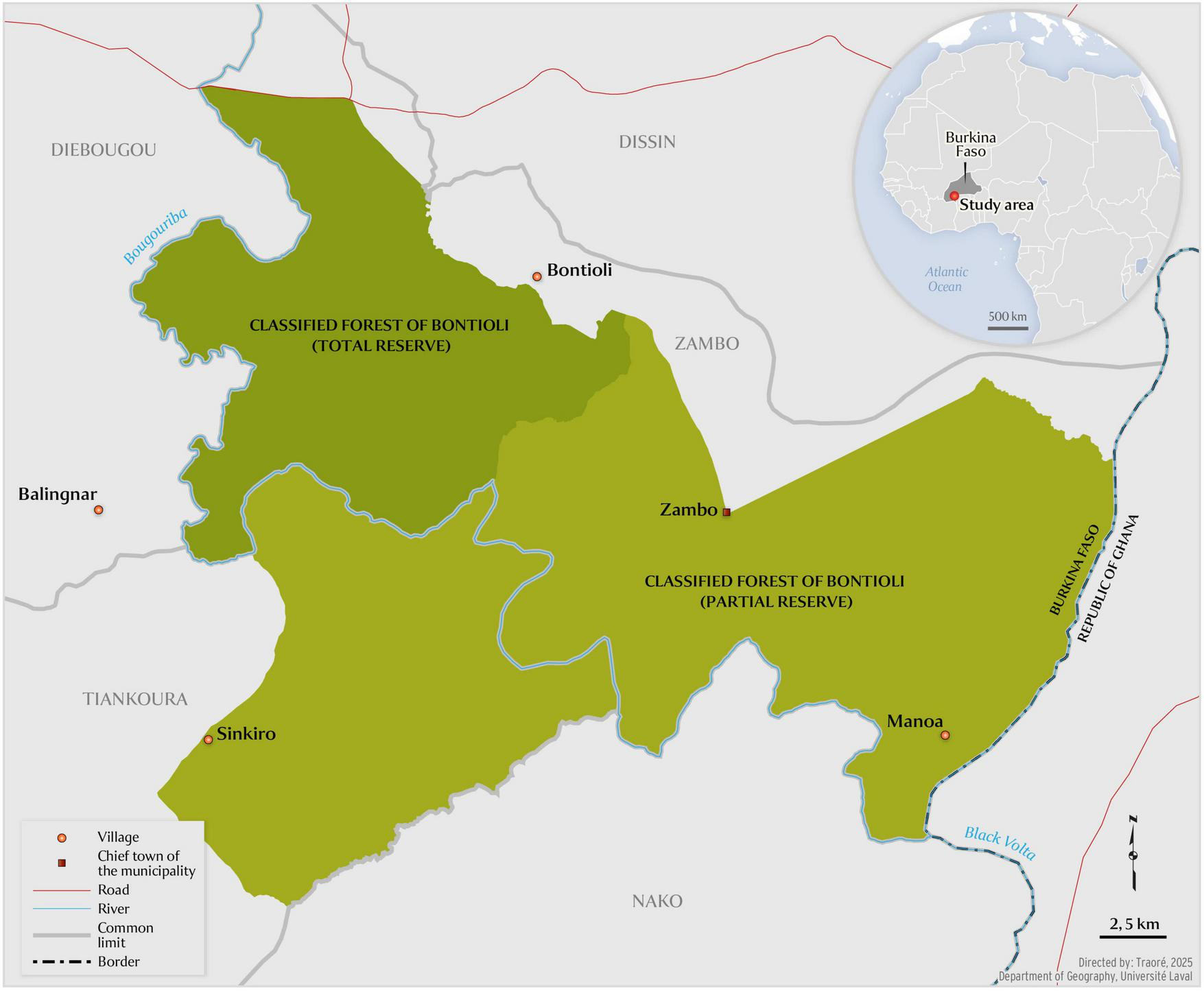

The Bontioli forest, located in the southwest of Burkina Faso (Figure 2), lies between latitudes 10°40′ N and 10°56′ N and longitudes 2°53′ W and 3°09′ W. This tropical forest receives up to 1,100 mm of annual rainfall and encompasses two wildlife reserves: a partial reserve covering approximately 29,500 hectares and a total reserve spanning around 12,700 hectares (Governor General of French West Africa, 1957). Despite its designation as a protected area, the forest is heavily impacted by human activity, with several villages established within its boundaries. Administratively, it falls under the jurisdiction of the rural commune of Zambo, where it occupies a substantial portion of the territory. Although classified as a wildlife reserve due to its ecological significance, the Bontioli forest is subject to considerable anthropogenic pressures, resulting in the progressive degradation of its vegetation cover (Dimobe et al., 2015; Lapola et al., 2023).

FIGURE 2

Map locating the study area.

A large proportion of the population in surrounding villages depends on agriculture, livestock rearing, and the exploitation of forest resources for their livelihoods (Gomgnimbou et al., 2010; Dimobe et al., 2015). The Bontioli Wildlife Reserves encompass 31 peripheral villages with an estimated population of 28,332 inhabitants as of 2017. These communities are closely tied to the use of natural resources, particularly land, water, and non-timber forest products (NTFPs) (Somé et al., 2024). Among these, plant-based NTFPs, such as the seeds of Parkia biglobosa (locally known as soumbala), play a central role in local diets, contributing to the nutritional intake of approximately 43.4% of rural households in Burkina Faso, while also serving as a source of income (Shackleton et al., 2010). These products are often processed locally, especially by women, into food items, traditional medicines, and natural dyes. Their collection is authorized within the partial reserve, in accordance with the provisions of the official classification order (Somé et al., 2024).

Over the past several decades, the region has witnessed the intensification of activities deemed illegal by the state, including uncontrolled land clearing, charcoal production, poaching, human-induced forest fires, and more recently, artisanal gold mining (National Institute of Statistics and Demography, 2022). These mounting pressures are partly attributed to rapid population growth, reflected in a crude birth rate of 37.9 per thousand in the region (National Institute of Statistics and Demography, 2022), as well as in-migration by communities seeking more fertile lands and pasture. In this context, managing the Bontioli forest presents a significant challenge in terms of both conservation and governance. Striking a balance between the preservation of this ecologically critical ecosystem and the subsistence needs of local populations remains a pressing concern for stakeholders involved in forest management.

3.2 Ethical procedures and authorizations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Human Subjects at Université Laval (approval no. 2022-020 A-1 / 08-08-2022).

3.3 Collection methods

3.3.1 Analysis of land use dynamics in the Bontioli forest

To gain a better understanding of long-term environmental changes, this study utilized satellite imagery. Landsat TM (1991), ETM+ (2001 and 2011), and OLI (2024) images of the study area were obtained from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) website. To optimize vegetation visibility, scenes captured between October and November were selected, as recommended by Gansaonré (2018). Indeed, the choice of this period (October and November) is associated with the fact that it corresponds to the period when the cloud cover rate remains very low with a good expression of vegetation linked to the recent end of the rainy season (Gansaonré, 2018; Zoungrana et al., 2015). Gansaonré (2018) also adds that this is particularly the ideal period to avoid episodes of bushfires which generally begin between the third decade of November and the first decade of December. The selection of a 10-year interval (1991, 2001, 2011, 2024) aligns with the official national land cover datasets of Burkina Faso, which are produced every decade (e.g., 1992, 2002, 2012). Aligning our temporal intervals with these national references enhances the comparability of our findings with existing datasets commonly used by national stakeholders. Moreover, the decadal scale allows for the detection of significant and interpretable trends in land cover dynamics, while maintaining a balance between analytical depth and processing feasibility.

The processing and analysis of these satellite images enabled the assessment of land cover changes over time and the extraction of quantitative data to measure these transformations. This digital image processing was performed using specialized software to manipulate and interpret the imagery. A supervised classification method was employed, relying on the identification of land cover categories based on spectral signatures in the satellite images (Mehmood et al., 2022), and was conducted using QGIS version 3.30 (QGIS Development Team, 2024). The land cover classification was based on a Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) typology adapted from the national land cover reference system (BDOT). Ten classes were defined to reflect the major landscape units observed in the study area: agricultural land, gallery forest, water bodies, built land, tree plantation, wooded savanna, shrubland savanna, grassy savanna, orchard, and bare soil. Color composites were applied to enhance visual interpretation: Landsat TM (1991) and ETM+ (2001 and 2011) images were displayed using a 4-3-2 band combination, while the 2024 OLI image used a 5-4-3 band combination to better highlight vegetation patterns. The accuracy of the land cover classifications produced using the maximum likelihood algorithm was assessed through confusion matrices based on reference points obtained from visual interpretation of high-resolution imagery and field knowledge. Overall accuracy and the Kappa coefficient were calculated for each classified year to evaluate the reliability of the results. The classifications achieved strong performance: 96% (Kappa = 0.92) for 1991, 88% (Kappa = 0.88) for 2001, 76% (Kappa = 0.76) for 2011, and 98% (Kappa = 0.96) for 2024. While the 2011 classification yielded a slightly lower accuracy (Kappa = 0.76) compared to other years, it still falls within an acceptable range for remote sensing applications. This drop in accuracy may be attributed to lower image quality and greater spectral confusion between land cover classes during that year. A post-classification filtering process was applied to enhance the spatial consistency of the results. The detailed confusion matrices for all classified years are provided in the Supplementary Appendices.

Displaying the images simultaneously in multiple views facilitated the identification of land cover classes and their temporal evolution. For classification, the supervised method using the maximum likelihood algorithm was selected, as it yielded the most accurate results. The classified raster outputs were subsequently vectorized in ArcGIS version 10.8 to generate land cover maps. Vectorization, the process of converting raster data (where information is stored as pixels) into vector format (represented as points, lines, and polygons), was conducted following the procedures outlined by Yao et al. (2024).

3.3.2 Analysis of the perceptions of local communities involved in the management and conservation of the Bontioli forest

3.3.2.1 Sampling

A total of 150 participants, comprising 26 institutional actors and 124 community members, were selected to reflect the diversity of stakeholders involved in the management of the Bontioli forest. The institutional actors included representatives from both local (n = 14) and state (n = 12) institutions, such as members of forest management groups (FMGs) and monitoring committees, leaders of village development committees (VDCs), traditional authorities, and public administration officials. The latter included forestry agents, provincial directors of agriculture and environment, chairpersons of special delegations, and coordinators of government programs such as the Forest Investment Program (FIP).

Community participants represented a broad demographic spectrum, including elders and youth, with deliberate attention to gender (i.e., 82 men and 42 women overall). Institutional actors were selected through purposive sampling, following the methodology described by Campbell et al. (2020), who recommend targeting key informants based on their strategic role in forest governance. In contrast, a random sampling technique was used to select community members. Four villages were included in the study, chosen based on their accessibility and spatial relationship to the forest: Sinkiro, Bontioli and Manoa (located within the forest boundaries), and Balingnar (approximately five kilometers away). Table 1 presents the distribution of respondents by stakeholder category and village.

TABLE 1

| Actors | Villages | Total | |||

| Sinkiro | Bontioli | Balingnar | Manoa | ||

| Institutional local | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 14 |

| Community | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 124 |

| Government institutions | – | – | – | – | 12 |

| Total | 37 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 150 |

Distribution of local and community institutional actors interviewed by area.

3.3.2.2 Data collected, collection tools and transcription methods

To assess stakeholder perceptions, data collection focused on several key dimensions: respondents’ views on the current level of deforestation in the Bontioli forest, the challenges related to existing conservation policies, and the adaptation strategies developed to reconcile resource use with environmental protection. Additional themes included stakeholders’ understanding of the socio-economic implications of conservation, perceptions of responsibility for forest degradation, traditional values that support preservation, and the motivations underlying intensive forest exploitation.

Two primary qualitative methods were employed: semi-structured individual interviews and focus group discussions. Individual interviews were conducted with the 26 institutional actors, selected based on their direct involvement in forest governance. In parallel, 12 focus group discussions were held with community members, organized by socio-cultural categories (elders, young men, and women) across the four selected villages. Each focus group consisted of 6 to 12 participants, in accordance with the recommendations of Nyumba et al. (2018). The duration of each interview or discussion ranged from 45 to 120 min.

3.4 Analysis method

The data collected were analyzed using a qualitative content analysis approach that combined both inductive and deductive reasoning. Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim using the online tool “TurboScribe” and subsequently coded in NVivo 14 to identify recurring themes during the inductive phase. Sentences and paragraphs were treated as meaningful units, each eligible for the assignment of one or more codes. The coding process followed the method outlined by Saldaña (2013), in which codes act as concise labels that support the organization of qualitative data into broader analytical categories.

In this study, the initial coding framework was informed by the study’s analytical model. Predefined categories, such as perceptions of deforestation, conservation challenges, and adaptation practices, constituted the deductive phase of the analysis. These categories provided a structured foundation for interpreting the qualitative material, while the iterative coding process allowed for the incorporation of emergent themes, ensuring analytical flexibility and depth.

4 Results

4.1 Land use dynamics and main drivers of deforestation

Forest decline is a widely acknowledged phenomenon in the Bontioli forest, with consensus among all stakeholders, including both local communities and state authorities, regarding the degradation of forest potential. While local communities do not distinguish clearly between different types of vegetation cover, they tend to perceive the forest as an area densely populated with plant species and not yet converted to agricultural use. This perception closely aligns with the scientific definition of a forest. From the perspective of forest officials, the act of tree felling is synonymous with deforestation and forest degradation and is therefore strictly prohibited and considered legally unacceptable. In contrast, local populations interpret tree felling through a different lens: it is viewed as a survival necessity, particularly for expanding agricultural land in the absence of viable livelihood alternatives (FJ1, FV1, FJ3). This necessity often compels them to clear new forest areas to ensure food security. These behaviors, rooted in local socio-economic realities, have a direct and tangible impact on the dynamics of forest degradation.

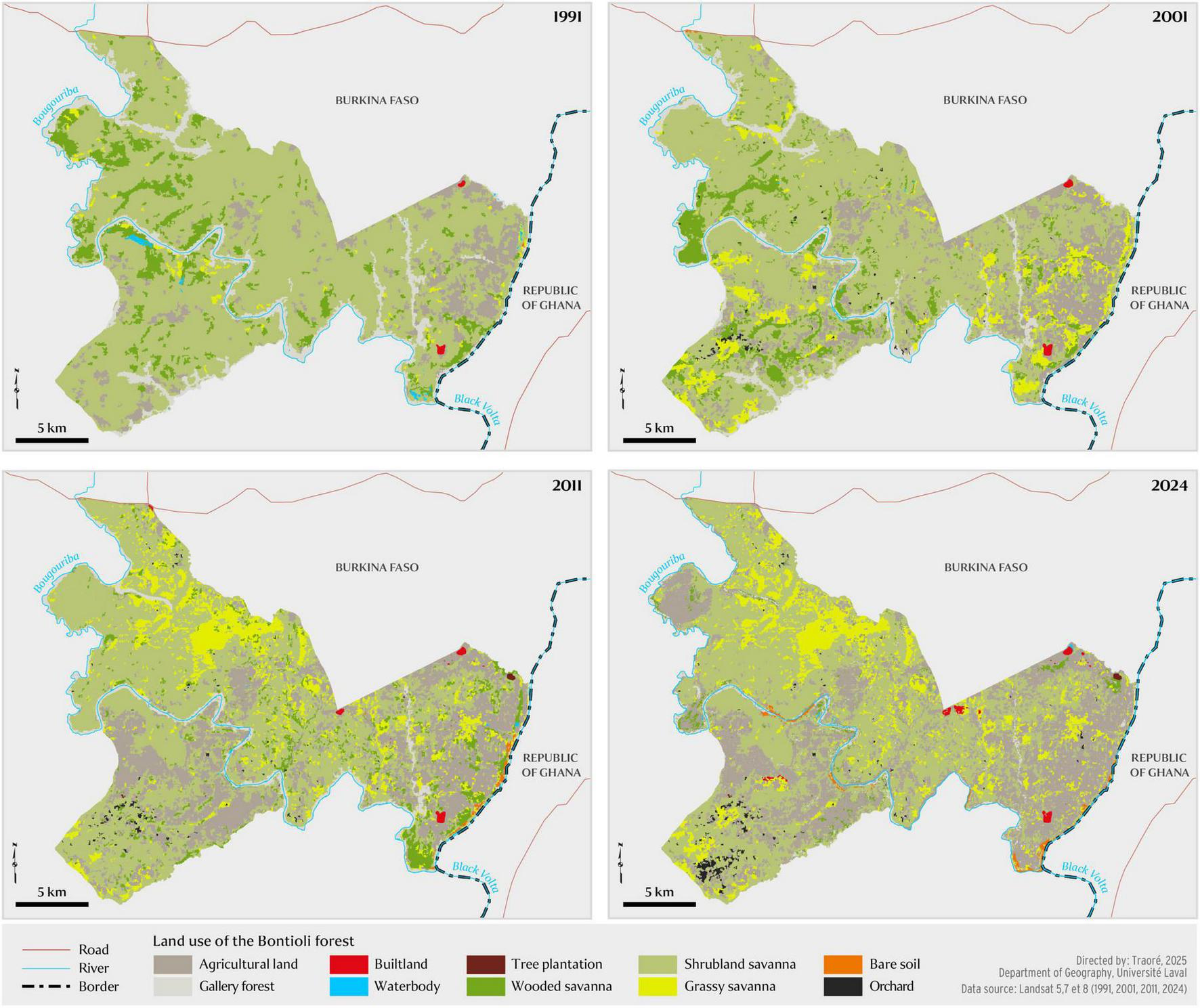

Figure 3 presents the evolution of land use units in the Bontioli Forest across four time points: 1991, 2001, 2011, and 2024. The figure highlights significant changes in land use categories, including the decline of gallery forests, wooded savannahs, and shrub savannahs, alongside the expansion of agricultural land, grassland savannahs, and human settlements. These transformations reflect a gradual deforestation process primarily driven by agricultural expansion and increasing human pressure, such as fuelwood collection, artisanal logging for housing, and village expansion.

FIGURE 3

Land use dynamics in the Bontioli forest.

The observed increase in bare soils and built-up areas further indicates intensified human activity, which may adversely affect the region’s biodiversity and ecological resilience. Additionally, the emergence and expansion of orchards, primarily composed of cashew trees, was noted during this period. The table below details the quantitative changes in the surface areas corresponding to each land use and land cover category.

Between 1991 and 2024, the area occupied by agricultural land (represented by the light gray-brown category on the map) increased substantially, rising from 3,905.52 ha to 14,738.51 ha. This rapid expansion contributed significantly to the loss of natural vegetation cover. Concurrently, land cover units such as gallery forests, wooded savannahs, and shrub savannahs experienced marked declines. Gallery forests diminished from 4,236.46 ha in 1991 to 1,089.48 ha in 2024, while wooded savannahs declined from 4,208.47 ha to 949.48 ha over the same period. The area of shrub savannahs fell from 33,634.66 ha to 22,841.20 ha, representing a loss of more than 10,000 ha (see Table 2). Beyond these visible changes, several less apparent factors have also contributed to vegetation loss. These include the expansion of artisanal gold mining, encroachment by nomadic herders, and the increased incidence of bushfires. A supplementary analysis, presented in the form of a horizontal bar graph (Figure 4), illustrates the percentage change in land use and land cover units. These percentages were calculated in relation to the total land area across all land use categories.

TABLE 2

| Land use classes | Surface area in 1991 (ha) | Surface area in 2001 (ha) | Surface area in 2011 (ha) | Surface area in 2024 (ha) |

| Agricultural land | 3905,521326 | 6583,940253 | 11028,74907 | 14738,51253 |

| Gallery forest | 4236,462009 | 3537,756733 | 1945,626024 | 1089,480611 |

| Builtland | 48,66864012 | 74,175645 | 105,6775593 | 157,3045371 |

| Waterbody | 133,9152239 | 89,5918927 | 148,0899477 | 121,8634527 |

| Tree plantation | 0 | 0 | 26,78150984 | 26,78150984 |

| Wooded savanna | 4208,468648 | 3822,791115 | 2616,649216 | 949,4809178 |

| Shrubland savanna | 33634,65666 | 28899,78845 | 24783,30012 | 22841,19632 |

| Grassy savanna | 591,7732635 | 3621,070874 | 5772,270389 | 6112,78997 |

| Bare soil | 4,77472583 | 8,320391474 | 134,87017 | 295,3485362 |

| Orchard | 0 | 126,788229 | 202,2095748 | 431,6402658 |

| Grand total | 46764,24049 | 46764,22359 | 46764,22358 | 46764,39865 |

Changes in land use and occupation units between 1991 and 2024.

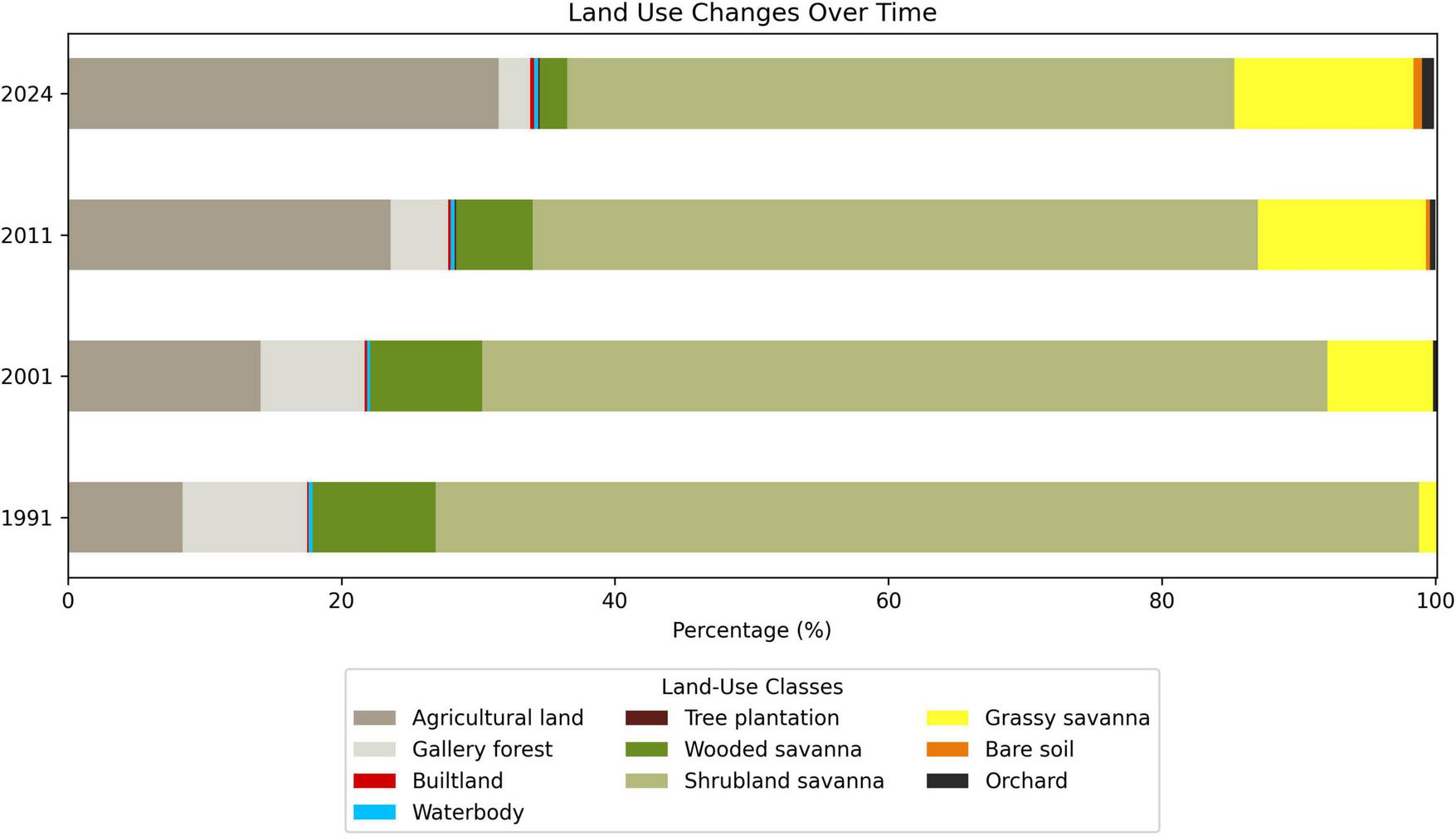

FIGURE 4

Graph showing trends in the evolution of land use areas.

The graph highlights the rapid transformation of forest landscapes into a mosaic increasingly dominated by agricultural land and degraded savannahs. The observed decline in forest cover and wooded savannahs reflects growing pressure on natural resources. Specifically, the graph shows a marked increase in agricultural land (light gray-brown) and grassy savannahs (yellow), while wooded savannahs (green) and shrub savannahs (light green) have gradually diminished. The expansion of built-up areas (red) further illustrates ongoing population growth, although this land use category remains relatively limited to a spatial extent. These land cover dynamics carry significant implications for biodiversity conservation and the ecological resilience of the region.

According to a provincial director of the environment, one of the forestry administration’s current objectives is to achieve “zero deforestation” within conservation areas (DP1), a goal that entails a strict prohibition of agricultural expansion into forest zones. To this end, policies and programs such as the Forest Investment Program (FIP) and PROGEREF (Sustainable Management Project for Forest Resources in the Southwest, Center-East, and East Regions) have been introduced to strengthen conservation efforts and halt the forest’s regressive trajectory.

Nonetheless, in a context characterized by limited access to arable land, and insufficient financial and material resources, many individuals have developed avoidance and adaptation strategies to circumvent forestry controls. These strategies enable them to continue clearing forested plots despite the legal risks and potential penalties (DP1). For numerous communities, particularly those residing within the forest, the abandonment of this land-use dynamic remains infeasible. Their limited access to agricultural inputs hinders the transition toward more intensive farming systems, thereby reinforcing reliance on extensive agricultural practices that continue to drive deforestation.

4.2 Different perceptions of deforestation and triangulation of results

4.2.1 Perception of deforestation

The rapid deforestation of the Bontioli forest has raised concerns among state authorities, who increasingly adopt a strict conservationist approach aimed at preventing all forms of forest degradation. In contrast, local communities tend to embrace a more flexible and pragmatic perspective on conservation, rooted in the direct utility of plant species for meeting their daily needs. These communities place particular importance on preserving species that hold clear economic or sociocultural value. While a strict conservationist framework emphasizes the intrinsic ecological importance of all plant species, local populations, who maintain long-standing historical ties to the forest, tend to prioritize those species that offer tangible, immediate benefits.

Perceptions of the forest and deforestation in the Bontioli region are thus shaped by the divergent interests and worldviews of different stakeholder groups. For example, several male participants justified forest clearing as a necessary measure to expand agricultural land and ensure household food security. In contrast, a group of women (FF1) expressed both an emotional and economic attachment to the forest, highlighting its centrality to their livelihoods:

“The forest is everything to us. It’s our sorghum, our millet, our sauce. Everything we have comes from the forest. Seeing it disappear like this saddens us deeply. We collect non-timber forest products (NTFPs), and we also harvest wood, which is our main source of energy. The forest must be preserved.”

This testimony underscores not only the apparent gendered divergence in forest perceptions but also the broader diversity of relationships that different social groups maintain with forest ecosystems. Local populations are caught in a paradoxical situation: on the one hand, agricultural expansion is seen as essential for food security; on the other, the forest’s legal classification as public domain imposes restrictions on land use that significantly constrain their livelihoods.

Within this context, strict conservation policies are often perceived as burdensome constraints. While communities frequently see themselves as victims of these policies, state authorities view them as primary agents of deforestation and thus hold them accountable. This divergence in perception complicates the implementation and effectiveness of conservation efforts, particularly when local populations perceive that the principal drivers of forest loss are external actors, such as recent settlers. Although these communities acknowledge their share of responsibility in forest degradation, they frequently attribute their actions to what they see as inadequate governmental enforcement against outside incursions. Furthermore, local actors assert that they contribute to forest preservation through informal resource-management practices that aim to respect existing norms (FJ1, FV1, FJ3, FV3, E14, E17). A group composed primarily of farmers (FV1) explained:

“During awareness sessions, agricultural officers recommend preserving 20 fruit trees per hectare of cultivated land. But as soon as we find useful trees, such as fruit trees, we systematically preserve them. Sometimes, we even keep more than the recommended number.”

Similar perspectives highlight intentional vegetation management (FV1):

“We don’t cut down trees haphazardly. We generally remove old trees that are no longer very useful. If a tree casts too much shade, we cut it down because it affects agricultural yields. So, we don’t act lightly. In fact, fruit trees are more productive on cultivated land than on uncultivated land.”

These comments illustrate the bold but responsible resource management practices adopted by some producers. In this context, rigid conservation, understood in its strictest form, emerges as a potential threat to local food security. Faced with rapid population growth, communities increasingly view the expansion of agricultural land not as an option, but as a survival imperative.

4.2.2 Triangulation of qualitative results and spatial data

The spatial analysis reveals a significant transformation of vegetation cover within the Bontioli forest. This shift is marked by the considerable expansion of agricultural land, built-up areas, and grassy savannahs, occurring at the expense of gallery forests, wooded savannahs, and shrublands. These patterns are strongly corroborated by local stakeholder perceptions, which consistently acknowledge the progressive depletion of forest resources. Community members explicitly identify the drivers of this degradation, attributing it both to immediate subsistence needs and to perceived governmental inaction. Testimonies also reflect a dual awareness: a clear recognition of ongoing ecological degradation, alongside continued efforts to selectively preserve economically and culturally valuable tree species, highlighting a pragmatic, albeit informal, approach to conservation.

The convergence between remote sensing findings and community narratives not only validates the observed environmental changes but also sheds light on the socio-economic logics underpinning forest resource use. This alignment allows for a more contextualized and nuanced understanding of deforestation processes, an essential foundation for designing conservation strategies that are both ecologically effective and socially inclusive.

4.3 Toward local forms of adaptation

In response to the constraints imposed by conservation policies, local populations have developed adaptation strategies aimed at reconciling resource use with environmental preservation. One notable strategy is the establishment of orchards, in which plant species deemed less useful are replaced with those of higher economic value. This trend has been reinforced by the return of migrants from neighboring countries with strong agroforestry traditions, such as Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Their efforts to introduce new practices have contributed to the expansion of cashew plantations in and around the Bontioli forest. For local communities, these plantations are viewed as a viable means of offsetting forest losses while generating income (FJ1, FJ2, E12, DP2).

However, the widespread adoption of this practice remains limited by several factors: the scarcity of available land, the recurrence of bushfires, and damage caused by free-roaming livestock. Additionally, due to financial and material constraints, cashew cultivation is often perceived as an option reserved for the wealthier members of the community (FJ1, FJ2, FJ3, FV3, E17).

The ecological and economic relevance of cashew cultivation was also emphasized by a provincial environmental director, who noted:

”Thanks to their dense foliage, cashew trees play an important role in carbon sequestration. They also contribute to the restoration of severely degraded land.”

4.4 Implications of forest conservation for socio-economic development

Studies have documented a widespread sense of socioeconomic marginalization among forest-dwelling communities, a sentiment openly expressed by residents of the Bontioli forest. While these communities recognize the critical importance of the forest in providing ecosystem services, they simultaneously express strong aspirations for socioeconomic development. From their perspective, however, these aspirations are hindered by the near-total absence of basic infrastructure, such as schools, health centers, and roads, which are deemed essential for improving local living conditions.

Government authorities consider the construction of such infrastructure within forested areas incompatible with conservation objectives, as it would require further deforestation. Although significant efforts have been made to develop infrastructure in rural zones, forest-dwelling communities perceive these efforts as disproportionately benefiting villages located outside protected areas. As a result, residents within the forest feel their access to essential public services is severely limited. In this context, forest conservation is perceived not only as an ecological priority but also as a constraint that contributes to delayed school enrolment and persistently low literacy rates. The demand for socioeconomic infrastructure is thus prioritized by these communities, sometimes even over forest preservation, despite their awareness of its ecological value. For many, residing within a classified forest reserve is equated with injustice and a denial of access to basic rights.

A government representative (P1), who has participated in several community meetings, argued that residents are not fully assuming their role in conservation. He emphasized that, despite limited resources, the government has demonstrated a willingness to support forest observers, community members charged with forest protection, through the provision of mopeds and bicycles for patrols, mobile phones for alerts, and other equipment intended to enhance forest surveillance and individual well-being. Nevertheless, the inability to meet basic infrastructure needs due to conservation restrictions continues to fuel feelings of marginalization among forest-dependent populations (FJ1, FJ3, FJ4, FV1, FV3, FV4, FF1, FF4). This perception further complicates conservation efforts, as frustration occasionally manifests in opportunistic behaviors in which individuals exploit forest resources for personal gain, often without regard for long-term sustainability. In response, several government officials have acknowledged the need for more robust support and meaningful engagement with local communities. Such efforts are increasingly viewed as critical for aligning conservation goals with the legitimate socioeconomic needs of forest-dependent populations.

4.5 Attribution of responsibility for the degradation of forest resources

Beyond natural factors associated with climate change, the degradation of the Bontioli forest is primarily attributed to human activity. However, the widespread assumption that resident communities are chiefly responsible for this degradation is strongly contested by these same populations. Many community members express a sense of helplessness in the face of repeated incursions by external actors, often originating from distant regions. They specifically identify gold miners, frequently regarded as “outsiders,” and Fulani herders, who are accused of invading the forest and intensively exploiting its resources for livestock fodder (FJ3, FF3, FF1). These herders are also reported to initiate forest fires to clear pathways for their animals in densely vegetated areas, a practice that contributes significantly to the destruction of plant species essential to both the forest’s ecological balance and the livelihoods of local residents.

In addition, a group of women (FF1) voiced concerns about increasing competition from nomadic herders, whose animals often consume non-timber forest products (NTFPs), thereby reducing access to resources critical to women’s subsistence activities. A youth representative (E14) further emphasized that most agricultural fields established within the total reserve are owned by individuals from distant villages. He acknowledged that only a small proportion of his own village’s residents are present in the forest, primarily within the partial reserve, and attributed this dynamic to the authorities’ lack of action in regulating external settlements.

While state representatives acknowledge the environmental damage caused by these exogenous groups, they often express skepticism toward the claims made by local populations, which they view as lacking in good faith (P1, P2, DP1, E5). Local residents, for their part, do not deny their own contribution to forest degradation. Many acknowledge that agricultural expansion within the forest is often a necessity, driven by limited access to arable land, population growth, and the rising cost of agricultural inputs (FJ1, FV1, FF1, FJ3, FV3, FJ4, FF4, DP3). As such, while they do not claim complete innocence, they reject the disproportionate blame frequently placed upon them.

Nevertheless, the constant accusations directed at them by forestry authorities generate deep frustration in some communities. This sense of injustice has, in certain cases, led to retaliatory behaviors, whereby individuals engage in forest exploitation with little regard for long-term conservation, further complicating efforts to preserve the ecosystem.

4.6 Loss of traditional values and conservation of forests

The research findings reveal that various traditional practices have historically contributed to the preservation of ecosystems, a point acknowledged by all stakeholders interviewed. These practices include the sacralization of specific forest areas or plant species, the customary regulation of hunting, and traditional systems of land management. According to local accounts, traditional chiefs played a central role in environmental stewardship by designating specific areas each year for agricultural and pastoral use, while reserving others as off-limits to any human activity. These customary governance systems were strictly enforced, and rule violations were rare due to the fear of severe social sanctions. Many respondents emphasized the effectiveness of these ancestral management systems in discouraging practices now commonly observed, such as the felling of tree species that were once protected. However, they also lamented the weakening influence of traditional authorities, particularly land chiefs, which has made it increasingly difficult to regulate deforestation (FJ3, FV3, FJ2, FV2).

The important role of traditional authorities is also recognized by the State, as confirmed by several institutional actors. Nonetheless, some officials highlighted the ambivalent role that these local leaders can play, particularly when they impede the enforcement of sanctions against members of their own communities (P1, DP1). In an effort to preserve social cohesion and local cooperation, forest agents have at times been compelled to show leniency toward certain offenders (P1), a practice that ultimately undermines forest governance and conservation objectives.

4.7 A contrasting vision of the opportunities offered to local populations

Land degradation, frequently cited by local populations as a justification for clearing new forest areas, is a global challenge. In the Bontioli region, although this rationale is commonly invoked by community members, several other factors contribute to the divergence in perspectives between local residents and forestry authorities. For instance, a local forestry station chief (E9) acknowledged that rising agricultural input costs are part of a broader global trend, particularly affecting countries like Burkina Faso that rely heavily on imports. However, he argued that communities living in and around the Bontioli forest continue to benefit from relatively favorable environmental conditions, including fertile soils and adequate rainfall, factors that, in his view, reduce the need for external inputs such as fertilizers to ensure good yields. This perception, grounded in a conservationist framework of forest management, partially explains the rigidity of some forestry officers regarding newly cleared plots and their limited tolerance toward local agricultural practices.

Nevertheless, despite the threat of sanctions, the persistence and scale of forest encroachment reflect the intensity of local food security challenges and broader socioeconomic needs. This is accompanied by an increasing reliance on intensive agriculture based on the continued expansion of cultivated areas, based on the belief that yields are more closely linked to land area than to the intensity of inputs.

This situation highlights the urgent need for increased state support aimed at enhancing access to agricultural inputs and promoting sustainable intensification practices. However, the success of such interventions depends not only on the physical availability of inputs like chemical fertilizers, but also on farmers’ awareness and capacity to use them responsibly (DP3). According to a provincial director of agriculture (DP3), while chemical fertilizers can support intensification on smaller plots, their misuse has contributed to declining soil fertility and the contamination of surface water in the region. As a result, resource-constrained populations, lacking both the means and the knowledge to shift to more sustainable systems, continue to expand their agricultural activities into forested areas, thereby exacerbating deforestation and environmental degradation.

5 Discussion

The spatial analysis conducted in this study reveals a significant decline in forest cover within the Bontioli reserve between 1991 and 2024, with a notable acceleration in deforestation over the past two decades. This trend is closely associated with the intensification of anthropogenic activities, particularly the expansion of agricultural land and urban settlements. These findings are consistent with those of Kiribou et al. (2024), who documented ongoing vegetation loss between 2000 and 2022. Furthermore, this pattern reflects a broader phenomenon observed across forested regions in sub-Saharan Africa, where increasing human pressure continues to undermine forest ecosystems (Ordway et al., 2017; Olorunfemi et al., 2021; Bissonnette et al., 2024). The Bontioli case exemplifies this regional dynamic, characterized by the progressive fragmentation of vegetative cover, which erodes ecological connectivity and threatens the delivery of essential ecosystem services.

Beyond documenting land-use changes, the study raises critical questions about the sustainability of current development trajectories. Qualitative findings indicate that, for many local communities, deforestation is driven by a logic of survival, rooted in rapid population growth, widespread poverty, limited access to fertile land, and constrained livelihood opportunities. These observations are aligned with the conclusions of Chomini et al. (2022), who emphasize poverty as a central driver of unsustainable resource use in Nigeria. However, the findings also caution against a deterministic interpretation of poverty as the sole cause of deforestation. Local narratives reveal a strong awareness of both the ecological and economic importance of forest ecosystems. Yet, persistent structural constraints, such as the absence of affordable alternatives, continue to limit the adoption of sustainable land-use practices. Thus, deforestation in the Bontioli region cannot be reduced to ignorance or indifference; it reflects a deeper tension between immediate subsistence needs and long-term conservation goals, posing significant challenges to environmental governance and social justice.

This context gives rise to complex and multifaceted conflicts over forest resources. These include not only tensions between resident and non-resident groups but also intra-community disputes among pastoralists, farmers, and women, particularly regarding access to grazing areas and non-timber forest products (NTFPs). Such findings echo Brottem (2016), who observed that environmental degradation and climate change in West Africa have exacerbated disputes between sedentary farmers and nomadic herders. Alusiola et al. (2021) further argue that perceptions of injustice, especially regarding resource access, can act as catalysts for community-level conflict.

The study also highlights that resident communities strongly contest the notion that they are the primary drivers of forest degradation. These findings suggest that conflicts in the Bontioli forest are not solely rooted in resource competition but are symptomatic of broader governance failures and widespread dissatisfaction with existing conservation mechanisms (Galvin et al., 2018; Friman, 2024). Respondents frequently described state conservation policies as repressive and disconnected from their lived socio-economic realities, further eroding trust and undermining the legitimacy of these initiatives (Galvin et al., 2018; Friman, 2024). These dynamics underscore the urgent need for more inclusive governance frameworks that meaningfully incorporate local perspectives into conservation planning. A more equitable, context-sensitive approach could help reduce social tensions and foster conservation strategies that are both ecologically sound and socially legitimate.

The analysis of stakeholder perceptions reveals that while local communities are indeed concerned about deforestation, they do not necessarily view it as a singular environmental crisis. Rather, deforestation is framed as a condition to be managed in relation to survival imperatives. Practices such as selective logging and agricultural expansion are not perceived as inherently destructive but as rational responses to livelihood constraints, strategies shaped by local ecological knowledge and necessity. In contrast, policymakers often interpret these activities through a conservationist lens, viewing them primarily as drivers of environmental degradation, a view consistent with dominant scientific narratives (Aleixandre-Benavent et al., 2018; Baruah and Barua, 2019). These divergent interpretations support the insights of Michon (2003), who argues that perspectives on forest conservation are shaped by the social positions, needs, and experiences of different groups. Similarly, Soe and Yeo-Chang (2019) show that local communities frequently evaluate conservation efforts through the lens of food and energy security. These findings highlight a pragmatic conservation ethic grounded in utility and embedded in long-standing ecological knowledge.

Although frequently misaligned with centralized conservation frameworks, such local perspectives offer important opportunities for policy innovation. A critical reading of the findings suggests that resistance to conservation does not reflect a rejection of conservation principles per se, but rather a response to how these policies are designed and implemented. As Sunderland and Vasquez (2020) argue, conservation strategies must be explicitly integrated with food security objectives to gain lasting local support. Similarly, Chomba et al. (2015) and Ece et al. (2017) emphasize that policy misalignment and the exclusion of communities from decision-making processes only serve to intensify tensions. As such, effective forest management must prioritize the rights, voices, and needs of local populations, ensuring that global conservation objectives are firmly rooted in the principles of sustainable development (Erbaugh et al., 2020).

6 Limitations and directions for future studies

Despite the significance of the findings, this study presents certain limitations that warrant consideration. Methodologically, the analysis relies primarily on qualitative interviews, which, although well-suited for capturing local perceptions and socio-environmental dynamics, limits the generalizability of the results beyond the specific study context. A collection of quantitative data (share of income from forest products and NTFPs over the years, area of land exploited per year, rate of access to basic infrastructure, rate of access to financial services, number of forest offenses recorded per area, etc.) could make it possible to better quantify the socio-economic pressures exerted on forest resources, evaluate conservation measures and guide more appropriate policies. Furthermore, the geographic focus on communities situated within or near the Bontioli forest confines the applicability of the findings, restricting their relevance to other forested regions of Burkina Faso. To address these limitations, future research could adopt a mixed-methods approach, integrating both qualitative and quantitative data to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the socio-environmental dynamics at play. Additionally, expanding the scope of the study to include other classified forests across the country would allow for comparative analysis, thereby enhancing the generalizability and policy relevance of the findings.

7 Conclusion

The findings of this study reveal a significant decline in forest cover and underscore the influence of divergent perceptions on forest resource conservation. For state actors, conservation is primarily framed as the protection of forest ecosystems to preserve their services for present and future generations, while deforestation is viewed as the destruction of vital ecological capital. This perspective is partially shared by local communities; however, when conservation policies impose restrictions on access to essential resources such as agricultural land, these measures are often met with resistance. In the case of the Bontioli forest, despite various initiatives, most notably through programs such as PROGEREF and the Forest Investment Program (FIP), substantial challenges remain. These include limited community participation in decision-making processes, a lack of viable economic alternatives, the marginalization of traditional authorities, and the persistent absence of socio-economic infrastructure within the forest zone.

Considering these findings, several strategic directions emerge. First, there is a need to enhance the involvement of local communities and their traditional leaders in the formulation and implementation of forest conservation policies. This involves clarifying the roles of customary authorities to regulate local practices more effectively and ensure governance systems that are grounded in the sociocultural realities of the region. Second, promoting sustainable economic alternatives such as agroforestry systems and high-value plantation crops, may help alleviate pressure on natural forest resources. The implementation of such measures is likely to improve community buy-in and ultimately increase the effectiveness and social acceptability of conservation efforts in the Bontioli forest.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Human Subjects of Université Laval (approval number 2022-020 A-1 / 08-08-2022). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MT: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Resources, Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation. J-FB: Methodology, Validation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. KD: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), project number: 430-2021-01031.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for supporting us by funding our field research. We also extend our heartfelt thanks to the local communities of the Bontioli forest, and all the participants in our research, for their openness and support. Without their assistance, this study would not have been possible. We also express our deep gratitude to the local authorities who facilitated our contact with the research participants. We cannot conclude without expressing our gratitude to Louise Marcoux, Evariste Meda, Raymond Kabo, Denis Blouin, Salifou Sanogo, Fulgence Talaridia Idani, and Rachid Addou for their multifaceted support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2025.1658611/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Adjognon G. S. Rivera-Ballesteros A. Van Soest D. (2019). Satellite-based tree cover mapping for forest conservation in the drylands of Sub Saharan Africa (SSA): Application to Burkina Faso gazetted forests.Dev. Eng.4:100039. 10.1016/j.deveng.2018.100039

2

Akomaning Y. O. Darkwah S. A. Živělová I. Hlaváčková P. (2023). Achieving sustainable development goals in ghana: The contribution of non-timber forest products towards economic development in the eastern region.Land12:635. 10.3390/land12030635

3

Aleixandre-Benavent R. Aleixandré-Tudo J. L. Castelló-Cogollos L. Aleixandre J. L. (2018). Trends in global research in deforestation. A bibliometric analysis.Land Use Policy72293–302. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.12.060

4

Aleru K. K. Agbugba I. K. Taremwa N. K. (2025). The bioeconomic profitability of non-timber forest products in the national building: A review.Rwanda J. Agricultural Sci.4169–202.

5

Alusiola R. Schilling J. Klär P. (2021). REDD+ conflict: Understanding The pathways between forest projects and social conflict.Forests12:748. 10.3390/f12060748

6

Ampadu P. B. Yang J. (2024). The impact of forestry management practices on regional economic benefits and livelihood of the rural communities in Ghana: A case study of three forest reserves in the Ashanti region.Front. For. Global Change7:1366615. 10.3389/ffgc.2024.1366615

7

Amusa T. O. Avana-Tientcheu M. L. Awazi N. P. Chirwa P. W. (2024). “The role of non-timber forest products for sustainable livelihoods in African multifunctional landscapes,” in Trees in a sub-saharan multi-functional landscape: Research, management, and policy, edsChirwaP. W.SyampunganiS.MwambaT. M. (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 153–178.

8

Baruah M. B. Barua R. (2019). Effects of deforestation on environment: Special reference to assam.Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev.3791–794. 10.31142/ijtsrd21470

9

Belem M. Zoungrana M. Moumouni N. (2018). Les effets combinés du climat et des pressions anthropiques sur la forêt classée de Toéssin, Burkina Faso. [The combined effects of climate and anthropogenic pressures on the Toéssin classified forest, Burkina Faso], Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci.12:2186. French. 10.4314/ijbcs.v12i5.20

10

Bissonnette J.-F. Dossa K. F. Nsangou C. A. Satchie Y. A. Moussa H. Miassi Y. E. et al (2024). What occurs within the mangrove ecosystems of the douala region in cameroon? Exploring the challenging governance of readily available woody resources in the wouri estuary.Environments11:121. 10.3390/environments11060121

11

Bouda H.-N. L. Savadogo P. Tiveau D. Ouedraogo B. (2011). State, forest and community: Challenges of democratically decentralizing forest management in the Centre-West Region of Burkina Faso.Sustainable Dev.19275–288. 10.1002/sd.444

12

Brottem L. (2016). Environmental change and farmer-herder conflict in agro-pastoral West Africa.Hum. Ecol.44547–563. 10.1007/s10745-016-9846-5

13

Campbell S. Greenwood M. Prior S. J. Shearer T. Walkem K. Young S. et al (2020). Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples.J. Res. Nurs.25652–661. 10.1177/1744987120927206

14

Chokkalingam U. Jong W. D. (2001). Secondary forest: A working definition and typology.Int. For. Rev.319–26.

15

Chomba S. Nathan I. Minang P. Sinclair F. (2015). Illusions of empowerment? questioning policy and practice of community forestry in Kenya.Ecol. Soc.20:2. 10.5751/ES-07741-200302

16

Chomini E. Imoh J. Ameh M. Henry M. Ademiluyi I. Mbah J. et al (2022). Forestry resource exploitation by rural household, their pathways out of poverty and its implications on the environment. a case study of toro LGA of Bauchi State, Nigeria.J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag.261851–1854. 10.4314/jasem.v26i11.17

17

Cissé M. Bationo B. A. Traoré S. Boussim I. J. (2018). Perception d’espèces agroforestières et de leurs services écosystémiques par trois groupes ethniques du bassin ver-sant de Boura, zone soudanienne du Burkina Faso. [Perception of agroforestry species and their ecosystem services by three ethnic groups in the Boura watershed, Sudanian zone of Burkina Faso], Bois For. Trop.33829–42. French. 10.19182/bft2018.338.a31680

18

Combes J.-L. Combes-Motel P. Schwartz S. (2016). Un survol de la théorie des biens communs. [An overview of the theory of commons], Rev. d’écon. Dév.2455–83. French. 10.3917/edd.303.0055

19

Coulibaly-Lingani P. (2011). Appraisal of the participatory forest management program in southern Burkina Faso.Sweden: Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre.

20

Devineau J.-L. Fournier A. Nignan S. (2009). “Ordinary biodiversity” in western Burkina Faso (West Africa): What vegetation do the state forests conserve?Biodiversity Conserv.182075–2099. 10.1007/s10531-008-9574-2

21

Dimobe K. Ouédraogo A. Soma S. Goetze D. Porembski S. Thiombiano A. (2015). Identification of driving factors of land degradation and deforestation in the Wildlife Reserve of Bontioli (Burkina Faso, West Africa).Global Ecol. Conserv.4559–571. 10.1016/j.gecco.2015.10.006

22

Ece M. Murombedzi J. Ribot J. (2017). Disempowering democracy: Local representation in community and carbon forestry in Africa.Conserv. Soc.15357–370. 10.4103/cs.cs_16_103

23

Erbaugh J. Pradhan N. Adams J. Oldekop J. Agrawal A. Brockington D. et al (2020). Global forest restoration and the importance of prioritizing local communities.Nat. Ecol. Evol.41472–1476. 10.1038/s41559-020-01282-2

24

Etongo D. Kanninen M. Epule T. E. Fobissie K. (2018). Assessing the effectiveness of joint forest management in Southern Burkina Faso: A SWOT-AHP analysis.For. Pol. Econ.9031–38. 10.1016/j.forpol.2018.01.008

25

Fernández-Montes de Oca A. Gallardo-Cruz J. A. Ghilardi A. Kauffer E. Solórzano J. V. Sánchez-Cordero V. (2021). An integrated framework for harmonizing definitions of deforestation.Environ. Sci. Pol.11571–78. 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.10.007

26

Fox J. (2000). How blaming’slash and burn’farmers is deforesting mainland Southeast Asia.Honolulu, HI: The East-West Center.

27

Friedman R. Rhodes J. R. Dean A. J. Law E. A. Santika T. Budiharta S. et al (2020). Analyzing procedural equity in government-led community-based forest management. Ecol. Soc. 25:16. 10.5751/ES-11710-250316

28

Friman J. (2024). Community forestry management implementation in Burkina Faso.Int. J. Commons18444–455.

29

Gaisberger H. Kindt R. Loo J. Schmidt M. Bognounou F. Da S. S. et al (2017). Spatially explicit multi-threat assessment of food tree species in Burkina Faso: A fine-scale approach.PLoS One12:e0184457. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184457

30

Galvin K. A. Beeton T. A. Luizza M. W. (2018). African community-based conservation: A systematic review of social and ecological outcomes.Ecol. Soc.23:39. 10.5751/ES-10217-230339

31

Gansaonré R. N. (2018). Dynamique du couvert végétal et implications socio-environnementales à la périphérie du parc W/Burkina Faso. [Dynamics of vegetation cover and socio-environmental implications on the periphery of the W/Burkina Faso park], Vertigo - Revue Électron. Sci. L’environ.18:1. French. 10.4000/vertigo.20249

32

Ghazoul J. Buřivalová Z. García-Ulloa J. King L. (2015). Conceptualizing forest degradation.Trends Ecol. Evol.30622–632. 10.1016/j.tree.2015.08.001

33

Gomgnimbou A. Savadogo P. Nianogo A. Millogo-Rasolodimby J. (2010). Pratiques agricoles et perceptions paysannes des impacts environnementaux de la cotonculture dans la province de la KOMPIENGA (Burkina Faso). [Agricultural practices and peasant perceptions of the environmental impacts of cotton cultivation in the province of KOMPIENGA (Burkina Faso)], Sci. Nat.7165–175. French. 10.4314/scinat.v7i2.59960

34

Governor General of French West Africa (1957). Arrêté conjoint portant délimitation et classement de le forêt et réserve totale de faune de Bontioli, portant délimitation et fixant le régime de la réserve partielle de faune de Bontioli-Cercle de Diébougou. [Joint decree delimiting and classifying the Bontioli forest and total wildlife reserve, delimiting and establishing the regime of the Bontioli-Diébougou Circle partial wildlife reserve].French: Governor General of French West Africa. French.

35

Hajjar R. Oldekop J. Cronkleton P. Newton P. Russell A. Zhou W. (2021). A global analysis of the social and environmental outcomes of community forests.Nat. Sustainabil.4216–224. 10.1038/s41893-020-00633-y

36

Karambiri M. Brockhaus M. (2019). Leading rural land conflict as citizens and leaving it as denizens: Inside forest conservation politics in Burkina Faso.J. Rural Stud.6522–31. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.011

37

Kiribou R. Dimobe K. Yameogo L. Yang H. Santika T. Dejene S. (2024). Two decades of land cover change and anthropogenic pressure around Bontioli nature reserve in Burkina Faso.Environ. Challenges17:101025. 10.1016/j.envc.2024.101025

38

Lapola D. Pinho P. Barlow J. Aragão L. Berenguer E. Carmenta R. et al (2023). The drivers and impacts of Amazon forest degradation.Science379:eab8622. 10.1126/science.abp8622

39

Mammadova A. Behagel J. H. Masiero M. Pettenella D. M. (2022). Deforestation as a systemic risk. the case of brazilian bovine leather.Forests13:233. 10.3390/f13020233

40

Mehmood M. Shahzad A. Zafar B. Shabbir A. Ali N. (2022). Remote sensing image classification: A comprehensive review and applications.Mathemat. Problems Eng.2022:5880959. 10.1155/2022/5880959

41

Michon G. (2003). Ma forêt, ta forêt, leur forêt. Perceptions et enjeux autour de l’espace forestier. [My forest, your forest, their forest. Perceptions and issues surrounding the forest space].Bois For. Des Trop.278215–224. French. 10.19182/bft2003.278.a20174

42

Michon G. Moizo B. Verdeaux F. De Foresta H. Aumeeruddy Y. Gely A. et al (2003). Perceptions et usages de la forêt en pays bara (Madagascar). [Perceptions and uses of the forest in Bara country (Madagascar)], Bois For. Des Trop.27815–24. French. 10.19182/bft2003.278.a20175

43

National Institute of Statistics and Demography (2022). Cinquième récensement général de la population et de l’habitation : Monographie de la région du Sud-Ouest. [Fifth General Population and Housing Census: Monograph of the Southwest Region].New Delhi: National Institute of Statistics and Demography. French.

44

Neaman J. S. (1994). Forests: The shadow of civilization. Robert Pogue Harrison.Speculum69158–160. 10.2307/2864820

45

Nyumba T. O. Wilson K. A. Derrick C. J. Mukherjee N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation.Methods Ecol. Evol.920–32. 10.1111/2041-210X.12860

46

Olorunfemi I. E. Olufayo A. A. Fasinmirin J. T. Komolafe A. A. (2021). Dynamics of land use land cover and its impact on carbon stocks in Sub-Saharan Africa: An overview.Environ. Dev. Sustainabil.2440–76. 10.1007/s10668-021-01484-z

47

Ordway E. Asner G. Lambin E. (2017). Deforestation risk due to commodity crop expansion in Sub-Saharan Africa.Environ. Res. Lett.12:044015. 10.1088/1748-9326/aa6509

48

Ouattara B. Sanou L. Koala J. Hien M. (2022). Perceptions locales de la dégradation des ressources naturelles du corridor forestier de la Boucle du Mouhoun au Burkina Faso.Bois For. Trop.35243–60. 10.19182/bft2022.352.a36935

49

Ouedraogo B. (2018). Forest policies and forest fringe Households’ resilience against poverty in participatory forest management sites in Burkina Faso.Environ. Manag. Sustainable Dev.793–114. 10.5296/emsd.v7i1.12523

50

Ouedraogo I. Sambare O. Savadogo S. Thiombiano A. (2020). Local perceptions of ecosystem services in protected areas in Eastern Burkina Faso.Ethnobotany Res. Appl.201–18.

51

Ouedraogo M. Ouédraogo D. Thiombiano T. Hien M. Lykke A. M. (2013). Dépendance économique aux produits forestiers non ligneux: Cas des ménages riverains des forêts de Boulon et de Koflandé, au Sud-Ouest du Burkina Faso. [Economic dependence on non-timber forest products: The case of households living near the Boulon and Koflandé forests in southwest Burkina Faso], J. Agriculture Environ. Int. Dev.10745–72. French. 10.12895/jaeid.20131.98

52

PACO/IUCN (2009). Évaluation de l’efficacité de la gestion des aires protégées : Parcs et réserves du Burkina Faso.Ouagadougou: IUCN.

53

Paré S. Savadogo P. Tigabu M. Ouadba J. M. Odén P. C. (2010). Consumptive values and local perception of dry forest decline in Burkina Faso, West Africa.Environ. Dev. Sustainabil.12277–295. 10.1007/s10668-009-9194-3

54

Pouliot M. Treue T. Obiri B. Ouédraogo B. (2012). Deforestation and the limited contribution of forests to rural livelihoods in West Africa: Evidence from Burkina Faso and Ghana.AMBIO41738–750. 10.1007/s13280-012-0292-3

55