Abstract

Forest therapy represents a key component of China’s ecological industry and plays a significant role in the rural revitalization strategy. Understanding the economic benefits accrued by local farmers through participation in forest therapy base development is essential for promoting sustainable rural development. Using survey data from 795 non-migrant farmers residing near forest therapy bases, this study examines the impact of forest therapy base development on household income, with distance to the bases serving as the instrumental variable. Control variables include individual characteristics, household attributes, farm types, and regional factors. The Endogenous Switching Regression Model (ESRM) is employed to estimate the causal impact of participation, while quantile regression is used to assess heterogeneity across participation types, farmer categories, and regions, followed by mechanism validation. The results reveal three key findings: (1) The Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) of employment participation is 0.3676, indicating a significant income boost for participating households. Compared to the counterfactual scenario, participation reduces income variability by 6.44%, suggesting higher and more stable household income, especially among new participants. (2) Heterogeneity analysis shows an inverted U-shaped impact: Forest therapy-based development participation most benefits middle-income farmers (QR_50). For agriculture-priority farmers, the impact is significant only among high-income groups (QR_75). Regionally, in western China, participation significantly raises income for low-income farmers (QR_25), while in eastern China, the largest gains are observed among middle (QR_50) and high-income (QR_75) farmers. Employment participation has a statistically significant effect on low-income (QR_25), middle-income (QR_50), and high-income (QR_75) households. In terms of the magnitude of the effect, government support has the strongest impact on low-income (QR_25) households. In the group with lower government support, employment participation has a significant effect on low-income (QR_25) and middle-income (QR_50) households, but the effect on high-income (QR_75) households is not significant. (3) Mechanism analysis indicates that both social network reinforcement (38.80% mediation) and ecological behavioral change (27.05% mediation) serve as significant partial mediators, the mechanisms of income enhancement operate through dual pathways. In conclusion, this study reveals that the income effects are characterized by two salient features: pronounced heterogeneity in benefit distribution among farmer groups, and divergent functioning of mediation pathways across regions. These findings underscore the need for targeted, context-specific policies to maximize the equitable and sustainable development of the forest therapy industry within the rural revitalization framework.

1 Introduction

With the deepening implementation of China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy and the widespread adoption of the concept that “lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets,” the forest therapy industry—a novel sector integrating ecological resources, health services, and tourism—has emerged as a key pathway for advancing green development in rural areas and enhancing farmers’ income. This study examines the disparities in rural disposable income between Inner Mongolia and developed coastal provinces in China, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable income growth in the region. Despite ranking 12th among China’s 31 provinces in terms of per capita disposable income for rural and pastoral residents, Inner Mongolia’s income level remains significantly lower than that of eastern coastal provinces. For instance, the rural disposable income in Shanghai is double that of Inner Mongolia, while in Zhejiang Province, it is 1.9 times higher. This underscores the critical challenge of achieving common prosperity in the region.

Inner Mongolia boasts abundant forest resources, with 408 million mu of forest area, representing the largest forest coverage in China and a forest coverage rate of 23.0%. Additionally, the region has 99 million mu of artificial forest area, ranking third nationally, and a forest stock volume of 1.6 billion cubic meters, ranking fifth nationwide. These forest resources serve as a “green bank” for stable income growth among rural households, demonstrating significant ecological benefits for poverty alleviation.

According to data from China’s National Forestry and Grassland Administration, by the end of 2020, forest resources had contributed to increasing the incomes of over 20 million impoverished people, achieving a “dual win” of poverty alleviation and ecological conservation. During the “13th Five-Year Plan” period, 1.102 million ecological rangers were selected from registered impoverished populations, helping more than 3 million people escape poverty. Furthermore, the development of ecological industries such as woody oil crops (e.g., camellia oleifera), ecotourism, forest wellness, and the forest economy helped lift over 16 million people out of poverty.

Data from the Office of the National Greening Committee further indicates that in 2020 alone, the forestry and grassland industry facilitated poverty alleviation and income growth for 16.16 million registered impoverished individuals. Specifically, 460,000 registered impoverished households, comprising 1.475 million people, achieved an average annual household income increase of approximately 5,500 RMB by leveraging forest resources.

Existing research indicates that the development of the forest therapy industry optimizes the social, economic, and ecological benefits of the forestry sector. It is gradually becoming a major direction and important driving force for social development, as well as a key pathway for structural reform and quality enhancement in China’s forestry production (Zheng et al., 2019). The future development of forest therapy is intertwined with rural revitalization, leveraging the natural environmental advantages of rural areas to boost tourism economies (Li et al., 2022). While returning to nature, people can protect and cultivate endangered flora and fauna, simultaneously advancing the strategy of rural revitalization, promoting farmer employment and income growth, and improving farmers’ quality of life (Chen and Shi, 2020). As a new industrial tool for promoting comprehensive rural revitalization, forest therapy must focus on resolving the issue of the lack of farmer agency in industrial development. It is essential to enhance farmers’ sense of presence, belonging, competitiveness, and resonance from an endogenous dynamics perspective, fully unleashing the boosting effect of forest therapy development on comprehensive rural revitalization (Hu and Pan, 2022). This aims to promote employment for forest area farmers, achieve prosperity through forestry, accelerate supply-side structural reform, enhance farmer well-being, and further realize the goal of Beautiful China. Therefore, the forest therapy industry plays a certain role in enhancing farmer well-being economically, socially, and ecologically. An indicator system has been constructed based on seven latent variables—development status, construction content, development planning, impact effects, economic well-being, social well-being, and ecological well-being—and 30 measurable variables. Using a structural equation model, the factors influencing the impact of the forest therapy industry on farmer well-being are identified, and pathways to enhance farmer well-being are proposed accordingly (Li M. et al., 2021). Driven by forestry-based poverty alleviation, the issuance of forest tenure certificates, agritainment, and forest tourism have significantly positive impacts on the income of impoverished forest households, promoting income growth (Li et al., 2018). This underscores the importance of targeted poverty alleviation through forestry and industrial poverty reduction, emphasizing the need to combine economic and ecological benefits during the process (Wang et al., 2018). Farmer participation in new forestry management entities significantly promotes household income growth, broadens income channels, and reduces wealth disparities in mountainous areas (Wu et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2024). Meanwhile, as an effective carrier of the “Two Mountains” theory, understory economic activities create both economic and ecological value. Active promotion and scientifically effective management can achieve synergistic growth of economic and environmental effects (Wu et al., 2023).

Therefore, based on the above research, it is evident that the forest therapy industry, as a crucial lever for rural revitalization, significantly enhances farmer income by activating the diversified value of forestry resources and synergistically broadening income channels.

Notably, rigorous causal inference on income effects is lacking, limiting evidence-based policy development (Wu et al., 2023). Most regression analysis studies on forest therapy’s impact on farmer income rely on Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimations (Chen et al., 2024), which does not adequately address endogeneity. Although Polish scholars applied the Endogenous Switching Regression Model (ESRM) to estimate the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) of farmer participation (Baltic et al., 2023), such applications are rare in Asian contexts.

Existing studies in China predominantly examine income effects stemming from traditional under-forest economies (Wu et al., 2023) or emerging forestry management entities (Wu et al., 2022), with limited or no dedicated analysis of forest therapy. Current research often emphasizes micro-level behavioral industrial mechanisms—such as social network restructuring or shifts in ecological awareness—those mediate outcomes. Methodologically, many studies are constrained by sample selection bias and endogeneity (Wang L. et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2024).

This raises several critical questions: (1) How can a theoretical framework of “employment participation in forest therapy bases—farmer income” be constructed to explain the income-increasing pathways? (2) Does farmer participation in forest therapy employment significantly increase income? What is the Average Treatment Effect (ATT) and the Counterfactual Effect (ATU)? (3) What mediating roles do social networks and ecological behaviors play in the “employment-income” chain? (4) What are the differential impact patterns across heterogeneous groups and regions?

To address these questions, this study focuses on the perspective of how the forest therapy industry promotes farmer income growth. It employs an Endogenous Switching Regression Model (ESRM) to empirically test the impact of farmer participation in forest therapy employment on income, utilizes quantile regression to analyze heterogeneity across different farmer types and regions, and validates the underlying mechanisms. This study aims to supplement the micro-level mechanisms of income increase for farmers engaged in forest therapy, provide an empirical basis for “mechanism-refined” rural revitalization policy design, and promote the industry’s transition from “scale expansion” to “pro-poor efficiency enhancement.”

2 Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

2.1 Theoretical analysis

This study develops a “Sustainable Livelihoods–Behavioral Response” framework by integrating the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) and Farm Household Behavior Theory. The sustainable livelihoods theory emphasizes that households achieve income growth through the combination and transformation of various livelihood capitals, such as natural capital, human capital, and social capital (Li et al., 2020). Forest therapy reconstructs rural household income structures through a triple-path mechanism—optimizing labor resource allocation, changing ecological behaviors, and strengthening social networks.

2.1.1 Optimization of labor resource allocation

Based on the theory of factor allocation, this study examines how rural households optimize their labor resource allocation through participation in forest wellness tourism bases, thereby influencing household income. In traditional agricultural production, labor inputs are subject to the phenomenon of diminishing marginal returns (Liu Y. et al., 2022). This implies that when excessive labor is allocated to limited land resources, the additional income generated by each incremental unit of labor gradually decreases. Employment in forest wellness tourism bases presents a new alternative for rural households. They can reallocate a portion of their labor force from traditional agriculture to the operation of forest wellness bases, thereby gaining new wage income.

Consequently, total household income is no longer solely dependent on traditional agriculture but comprises both agricultural income and income from forest wellness base employment. The core focus of this paper is to investigate how rural households optimize their overall labor allocation by adjusting labor participation in wellness bases, thereby circumventing the “diminishing marginal returns” constraint of traditional agriculture and achieving an increase in total household income.

2.1.2 Ecological behavioral change

Employment in forest therapy bases enables farmers to actively serve visitors while progressively enhancing their ecological awareness through environmental education as the number of tourists increases, leading to voluntary adoption of pro-environmental practices (Chen et al., 2025). This transformation in environmental cognition motivates behavioral shifts toward ecological conservation, which in turn generates positive environmental feedback. Beyond direct wage income from forest therapy employment, farmers benefit from improved ecological conditions that attract more visitors, creating additional revenue streams (Chen et al., 2024). Field surveys reveal that many farmers supplement wage income by selling local agricultural products, demonstrating how elevated ecological cognition drives behavioral changes that ultimately enhance earnings. Essentially, ecological behavioral transformation facilitates a shift from resource extraction to ecological stewardship, thereby increasing household income through sustainable practices.

2.1.3 Social network reinforcement

The embeddedness of the forest therapy industry expands farmers’ information acquisition and collaboration channels to varying degrees. When employed at forest therapy bases, farmers enter resource utilization networks where communication with tourists and enterprises establishes new connections that broaden information channels and strengthen social networks. This enhancement of previously weak social ties increases access to non-agricultural employment opportunities, thereby reinforcing participation in forest therapy employment and generating income effects.

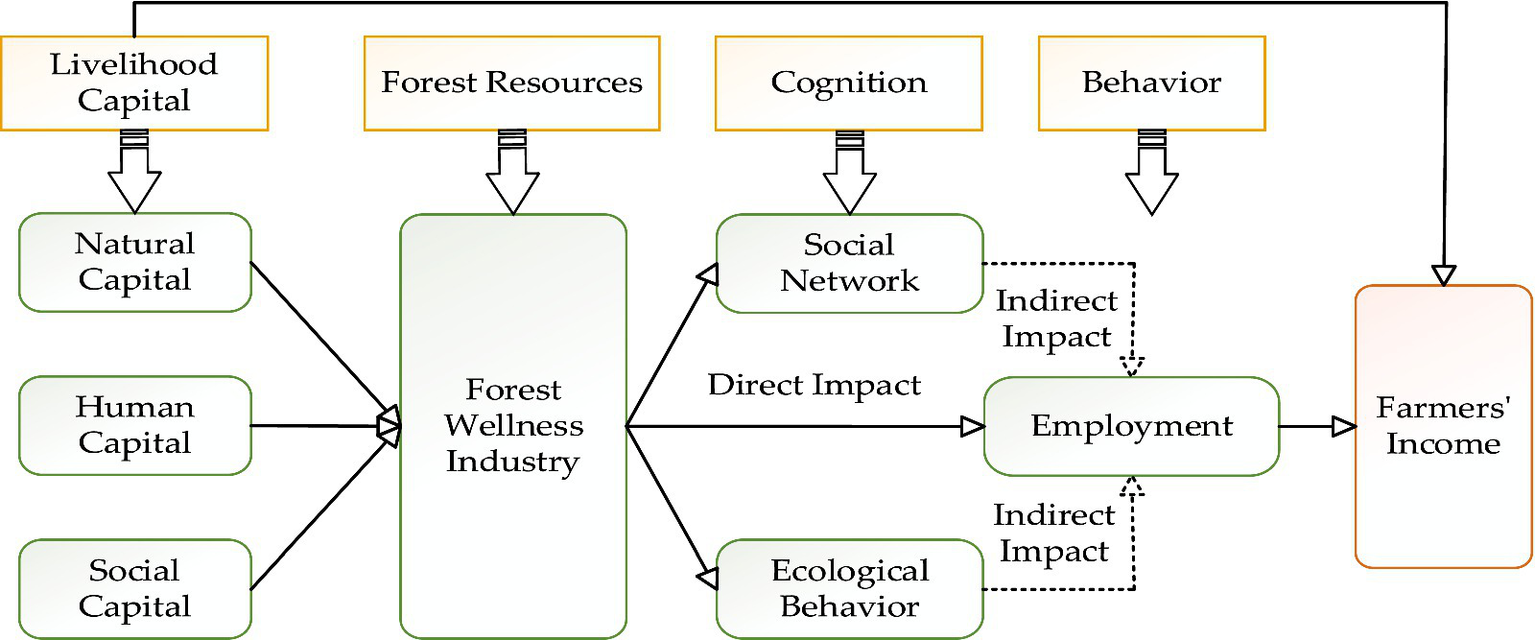

Based on this analysis, we construct a theoretical framework (Figure 1) highlighting three pathways: first, the direct impact of forest therapy employment on income; second, the indirect effect mediated through ecological behavioral change; third, the indirect effect mediated through social network reinforcement.

Figure 1

Theoretical analysis framework.  represents the corresponding relationship between the upper layer and the next layer,

represents the corresponding relationship between the upper layer and the next layer,  represents the progressive relationship between the layers,

represents the progressive relationship between the layers,  represents indirect impact,

represents indirect impact,  represents the upper level and

represents the upper level and  represents the next level.

represents the next level.

2.2 Research hypotheses

According to the aforementioned theoretical analysis, when farmers participate in forest therapy bases through employment, it essentially represents a cross-sectoral mobility of labor resources from traditional agriculture to the service industry. Furthermore, forest therapy bases establish close benefit linkage mechanisms with local rural households, promoting employment of surplus labor (Li, 2023). Labor quantity and service quality are identified as key driving factors for the high-quality development of forest therapy bases (Song et al., 2023). This mobility not only broadens non-agricultural employment channels for farmers but also enhances their unit labor remuneration through human capital appreciation effects. Based on this, we propose Hypothesis H1.

H1: Participation in forest therapy employment significantly increases farmer income.

According to the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach, farmers’ investment in social capital plays a promotive role in their income. The forest therapy industry expands farmers’ information channels through tourist demand and opportunities for cooperation with therapy bases, and diversified information channels strengthen their social networks. Empirical studies demonstrate that the reinforcement of social networks can significantly enhance farmers’ participation in non-agricultural employment and income levels (Wu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2018), markedly improving their bargaining power and income in forest therapy employment (Zhang and Li, 2016). Based on this, we propose Hypothesis H2.

H2: Participation in forest therapy employment inhibits income growth through the social network.

Sustainable livelihoods theory also posits that forest therapy employment strengthens ecological awareness—a key dimension of human capital, which can drive the adoption of high-value practices. This “cognition-to-behavior” transformation enables income enhancement through premium product mechanisms, thereby improving both operational and property-based income streams (Ohe, 2024; Jones et al., 2023). Sustainable livelihoods theory also posits that forest therapy employment strengthens ecological awareness—a key dimension of human capital, which can drive the adoption of high-value practices. This “cognition-to-behavior” transformation enables income enhancement through premium product mechanisms, thereby improving both operational and property-based income streams (Ohe, 2024; Jones et al., 2023). We draw on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and value chain analysis (Kaplinsky and Morris, 2001) to argue that enhanced ecological awareness catalyzes specific, high-value ecological behaviors—such as organic farming or participation in carbon sink projects—that generate income through premium markets and payments for ecosystem services. This “cognition–behavior–income” pathway enables farmers to capture additional value from ecological quality and differentiation (Muradian and Rival, 2012), thereby improving income through both operational and property-based streams.

When employed at forest therapy bases, farmers actively serve visitors and, with the increasing number of wellness tourists, further enhance their ecological awareness through environmental education, thereby strengthening their environmental conservation consciousness and proactively adopting pro-environmental practices (Chen et al., 2025). As farmers’ ecological cognition continuously transforms, their ecological conservation behaviors change accordingly, leading to positive environmental feedback. In addition to earning direct wage income from forest therapy employment, farmers benefit from the improving ecological environment, which attracts more visitors and generates additional revenue streams (Chen et al., 2024). Field surveys reveal that some farmers not only receive wages from forest therapy employment but also earn extra income by selling local agricultural products. This fully demonstrates that enhanced ecological cognition among farmers leads to changes in ecological behavior, thereby resulting in income growth. Specifically, the shift in farmers’ ecological behavior transforms them from resource extractors to ecological stewards, ultimately enhancing their income through behavioral change.

Critically, while employment generally raises income as a mechanism is neither obvious nor trivial. It reflects a distinctive feature of green employment in the forest therapy sector and aligns with the concept of “green skills” and “pro-environmental income” discussed in contemporary sustainable development literature (International Labour Organization [ILO], 2019). Thus, we propose Hypothesis H3:

H3: Participation in forest therapy employment promotes income growth through ecological behavioral change.

3 Analysis of variance in farmer income

3.1 Data sources

This study utilizes data collected through field surveys conducted from July to September 2024 among farmer households residing near forest therapy bases in selected leagues and cities of Inner Mongolia. The survey specifically targeted non-migrant households, a non-immigrant household refers to a rural household whose members have no experience of working outside the local area in the past year, the household income mainly depends on the income obtained locally. This focus was justified for two primary reasons:

First, the primary objective of this study is to estimate the local income effects of employment in the forest therapy sector. Non-migrant households, whose livelihoods are predominantly derived from local sources, constitute the core labor pool for this emerging industry (Wen and Ju, 2021). Their income structure is more directly tied to local economic conditions, making them a suitable group for identifying the intended treatment effect (Ren and Jin, 2022).

Second, if the study includes migrants (defined here as individuals who leave their household registration area to work in other regions), their income would primarily originate from non-local sources. Since this study focuses on the impact of employment in forest therapy bases on farmers’ income—which mainly includes agricultural land income and wages from forest therapy employment—the inclusion of migrant workers would introduce confounding factors. Their income is significantly influenced by off-farm migration earnings, making it difficult to isolate the net income contribution of forest therapy employment.

We acknowledge that this sampling strategy may affect the generalizability of our findings. Our results are most representative of households with a pre-existing preference or constraint to pursue local livelihood strategies. The income effects we identify may not be generalizable to migrant households, who likely have different risk perceptions, skill sets, and income portfolios. Consequently, the estimated treatment effects should be interpreted as applicable to the population of local, non-migrant households engaged in or eligible for forest therapy employment, rather than to the entire rural population indiscriminately.

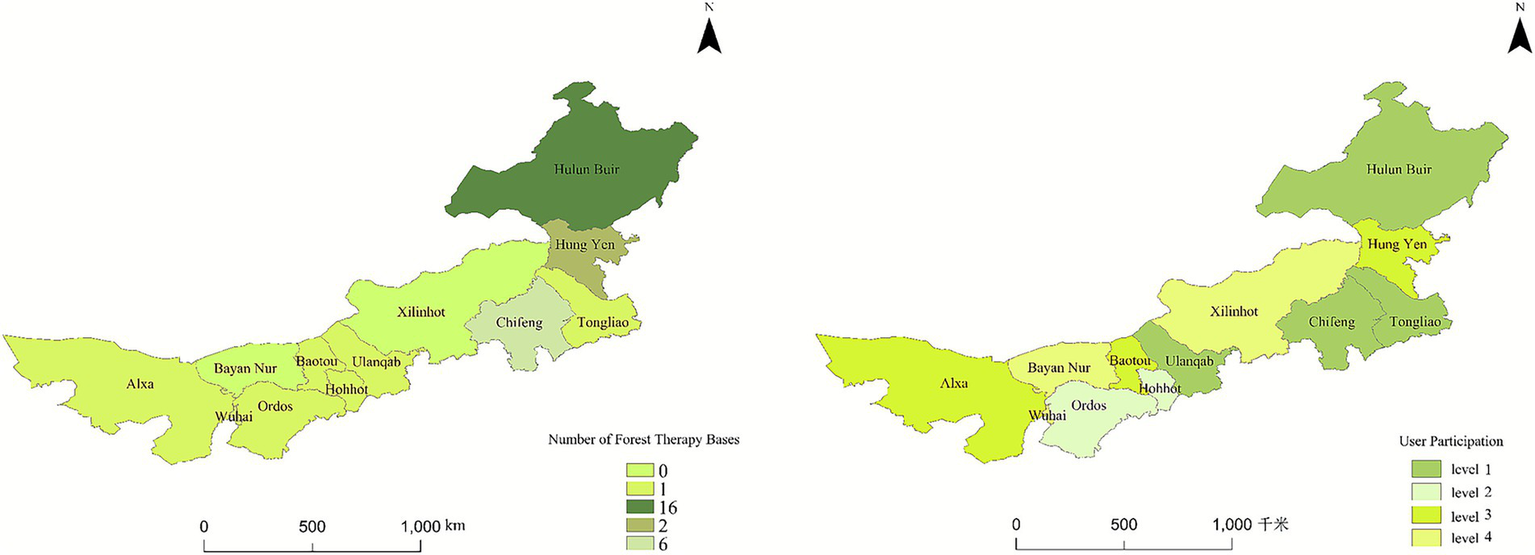

Based on the distribution of national forest therapy bases across leagues/cities in Inner Mongolia, their geographical locations, the number of demonstration bases per league/city, and farmer participation levels (Figure 2), this study selected six cities in eastern Inner Mongolia (Hulunbuir, Chifeng, and Tongliao) and western Inner Mongolia (Ulanqab, Hohhot, and Ordos) as research sites. These cities host national forest therapy base construction units, ensuring regional representation for mechanism validation.

Figure 2

The number of forest therapy bases and the participation of farmers in Inner Mongolia.

Subsequently, based on operational status, approval batches, and infrastructure development, between one and three nationally certified forest therapy demonstration bases were selected per municipality. Nearby households were then randomly sampled for face-to-face questionnaires and interviews examining income structures.

From 885 distributed questionnaires, 795 valid responses were obtained, yielding an 89.83% validity rate. As shown in Figure 3, the distribution of forest therapy bases across Inner Mongolia is highly heterogeneous. Consequently, the number of eligible households varied significantly by region. Our survey sample size per region (Table 1) is a direct reflection of this underlying distribution, with larger samples drawn from core clusters of forest therapy activity (e.g., Chifeng) and smaller samples from regions with fewer bases (e.g., Hohhot). This sampling approach ensures that our data accurately captures the realities of the industry’s development. As shown in Table 1, 57.11% of surveyed households participated in forest therapy employment, significantly exceeding non-participants (42.89%), which indicates high local industry engagement.

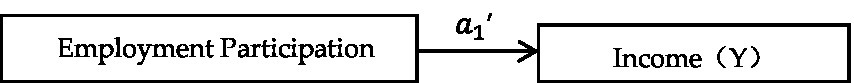

Figure 3

The total effect of farmers’ participation in forest health base on income.

Table 1

| Region | Sample size | Employed | Non-employed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 795 | 454 | 341 |

| Ulanqab | 79 | 60 | 19 |

| Hohhot | 19 | 10 | 9 |

| Ordos | 42 | 39 | 3 |

| Chifeng | 487 | 241 | 246 |

| Tongliao | 120 | 67 | 53 |

| Hulunbuir | 48 | 37 | 11 |

Sample distribution by survey region.

3.2 Variable specification and explanation

3.2.1 Dependent variable

Following established methodologies (Wang Y. C. et al., 2021; Gao and Qiao, 2024; Pan et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2021), annual household income averaged over 3 years serves as the primary income indicator. This variable is log-transformed to mitigate skewness and is used as the dependent variable in econometric models. This measure captures mid-term economic well-being and is less susceptible to annual fluctuations than a single-year snapshot.

3.2.2 Core explanatory variable

The binary variable forest therapy employment participation (1 = employed at forest therapy bases, 0 = otherwise) constitutes the core explanatory variable, reflecting labor allocation decisions within local production systems. It directly measures the treatment effect of primary interest in this study.

3.2.3 Identification variable

To ensure model identification, the distance to the nearest forest therapy base is selected as the exclusion restriction variable. This approach is consistent with the widespread use of geographic instruments in rural labour and development economics (Chen et al., 2023; Fafchamps and Shilpi, 2013). Physical distance is a strong predictor of program participation or market access. At the same time, it remains plausibly exogenous to household-level outcomes once regional controls are included. It directly influences participation decisions and exhibits strong exogeneity to household income (Yu et al., 2021). The validity of this instrument is further confirmed by formal endogeneity tests in subsequent analyses. It directly measures the treatment effect of primary interest in this study.

3.2.4 Mediation variables

Building on established theoretical frameworks (Zhang and Li, 2016; Lu and Xie, 2017; Ma and Zhang, 2019; Zhang and Xu, 2023; Zhang et al., 2016; Xie and Chen, 2020; Li F. D. et al., 2021), this study examines two mediation pathways: social network reinforcement (measured by information channel diversity index) and ecological behavioral change (assessed through adoption of organic farming and carbon sink projects), which operationalize the mechanisms through which forest therapy employment influences income outcomes. Among them, the social network reinforcement is represented by the convenience of farmers’ access to market information channels (very low = 1; relatively low = 2; average = 3; relatively high = 4; very high = 5), and the ecological behavior change is represented by the frequency of farmers’ participation in environmental protection activities each year.

3.2.5 Control variables

Four categories of control variables are included to account for potential confounding effects (Sun and Gao, 2022; Wang et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2020; Liu S. C. et al., 2022) and isolate the net effect of forest therapy employment:

3.2.5.1 Individual characteristics

Individual characteristics controls for human capital endowment. This study assigned values to personal characteristic variables as follows: gender was coded as male = 1 and female = 2; age was categorized into six groups: 25 years and below (=1), 26–35 years (=2), 36–45 years (=3), 46–55 years (=4), 55–60 years (=5), and above 60 years (=6); self-rated health status was classified into five levels: very healthy (=1), healthy (=2), fair (=3), unhealthy (=4), and very unhealthy (=5); marital status was divided into married (=1), unmarried (=2), and divorced (=3); type of social security participation was classified into five categories: enrolled only in endowment insurance (=1), only in medical insurance (=2), only in commercial insurance (=3), both endowment and medical insurance (=4), and all three types including commercial insurance (=5); housing area was measured as the actual built-up area (in square meters); availability of elderly care institutions in the area was classified as available but scarce (=1) or not available (=2).

3.2.5.2 Household attributes

Household attributes controls for household wealth and productive capacity. Regarding household characteristics, household size refers to the total number of actual co-residing members; the number of children and the number of elderly represent the actual count of minors and elderly individuals in the household, respectively; annual household expenditure is the average total consumption expenditure calculated based on the past 3 years; per capita cultivated/forest land area was derived by dividing the total household cultivated or forest land area by the total number of household members (unit: mu/hectare); household loan and savings status are binary variables indicating the presence of loans (no = 1, yes = 2) or savings (no = 1, yes = 2); annual household telephone expense was recorded as the actual amount spent; both self-rated family social status and self-rated family social connections were assessed using five-point Likert scales, ranging from very poor (=1) to very high (=5) for social status, and from very low (=1) to very high (=5) for social connections.

3.2.5.3 Farmer typology

Farmer typology controls for pre-existing livelihood strategies that may influence both participation decisions and income levels (Ke et al., 2022). Three household type dummy variables were constructed to reflect different livelihood strategies: the “agriculture priority type” was coded as 1 if the household fell into that category and 0 otherwise; similarly, the “forestry dependent type” was assigned a value of 1 for relevant households and 0 for others; likewise, the “non-agricultural non-forestry dominant type” was set to 1 for applicable households and 0 otherwise.

3.2.5.4 Regional dummies

To control for regional heterogeneity, six regional dummy variables were introduced: for instance, “Ordos” was coded as 1 if the household was located in Ordos City and 0 otherwise; the same coding scheme was applied to variables for Hohhot, Hulunbuir, Tongliao, Chifeng, and Ulanqab, with all other regions serving as the reference group.

Finally, the definitions and measurements for all variables are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Variable type | Variable name and explanation | Mean | Std. dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Annual household income | 61,067 | 58,118 | |

| Core explanatory variable | Employment (Yes = 1, No = 0) | 0.5711 | 0.4949 | |

| Identification variable | Distance to forest health base (km) | 6.7747 | 12.3671 | |

| Mediating variables | Social network strengthening (1–5) | 3.3082 | 1.1107 | |

| Ecological behavior change (Times) | 2.4126 | 0.8654 | ||

| Control variables | Individual characteristics | Gender (1 = M, 2 = F) | 1.3899 | 0.4880 |

| Age | 4.0767 | 1.1032 | ||

| Personal health status (1–5) | 2.1472 | 0.7610 | ||

| Marital status (Yes = 1, No = 2, divorced = 3) | 1.1283 | 0.4557 | ||

| Personal life security (1–5) | 3.4742 | 0.9564 | ||

| Residential area (m2) | 77.81 | 23.02 | ||

| Presence of elderly care facilities (Yes = 1, No = 2) | 1.6931 | 0.4615 | ||

| Household characteristics | Number of household members | 3.1371 | 1.1972 | |

| Number of children | 2.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Number of elderly | 0.8526 | 0.9204 | ||

| Annual household expenditure (RMB Yuan) | 23,565 | 13,023 | ||

| Per Capita cultivated/forest land area (Mu) | 6.3892 | 13.3314 | ||

| Presence of household loans (No = 1, Yes = 2) | 1.0478 | 0.2135 | ||

| Presence of household savings (No = 1, Yes = 2) | 2.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| Household telephone expenses (RMB Yuan) | 1862 | 1,508 | ||

| Household social status (1–5) | 3.0931 | 0.8481 | ||

| Household social relations status (1–5) | 3.3157 | 0.9320 | ||

| Type dummy variables | Agriculture priority type (0/1) | 0.4717 | 0.4995 | |

| Forestry dependent type (0/1) | 0.1358 | 0.3428 | ||

| Non-agricultural non-forestry dominant type (0/1) | 0.3950 | 0.4892 | ||

| Regional dummy variables | Hohhot (0/1) | 0.0239 | 0.1528 | |

| Ordos (0/1) | 0.0516 | 0.2213 | ||

| Hulunbuir (0/1) | 0.0604 | 0.2383 | ||

| Chifeng (0/1) | 0.6126 | 0.4875 | ||

| Tongliao (0/1) | 0.1509 | 0.3582 | ||

| Ulanqab (0/1) | 0.0994 | 0.2993 | ||

Descriptive statistical analysis of variables.

Reference groups for dummy variables: for Farmer Typology-“Others”; for Regional Dummies-“Other regions”.

3.3 Descriptive statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 2. The average distance to forest therapy bases was 6.77 km, supporting employment accessibility. Personal characteristics reveal a male-dominated sample (61%), with respondents primarily between the ages of 36–55. Mean health status (2.15) and housing conditions (77.81 m2) indicate favorable living standards, while 92% were married. Social security metrics (mean = 3.4) reflect prevalent dual enrollment in pension and medical insurance.

Household attributes show family sizes at 3.14 members, with low elderly dependency (0.85 seniors/household). Annual expenditures averaged ¥23,565, while per capita landholding was 6.39 mu (0.43 ha). Notably, 60.9% of households held savings (mostly ≤¥30,000), while only 4.7% carried loans. Social capital indicators demonstrate moderate perceived status (3.09) and strong community ties (3.32).

Farmer typology distribution was as follows: agriculture-oriented (47.2%), non-agricultural/non-forestry (39.5%), and forestry-dependent (13.5%). Regionally, Chifeng accounted for the largest share of the sample (n = 487, 61.3%) due to its high concentration of forest therapy bases, followed by Tongliao (15.1%) and Hulunbuir (12.6%), with other regions comprising less than 10% each.

4 Methodology and model specification

4.1 Endogenous switching regression model (ESRM)

Preliminary analysis confirms significant income effects from forest therapy employment participation. To address selection bias, endogeneity, and confounding effects from both observed and unobserved variables—while enabling counterfactual estimation, we adopt the ESRM by Lokshin and Sajaia (2004) and Qi et al. (2024). This approach jointly estimates participation decisions and income equations through maximum likelihood, correcting for self-selection via correlated error structures between the selection and outcome (Equation 1):

In the model, represents the annual average household income. denotes a set of factors influencing household employment participation decisions, including individual characteristics, household attributes, household typology, and regional factors. is a binary decision variable for household i, where = 1 if the household participates in employment and = 0 otherwise. represents the parameters to be estimated, quantifying the magnitude of the income effects associated with all control variables. denotes the parameters capturing the effect of employment participation on income. denotes the stochastic error term.

Following the estimation framework of the ESRM, the regression model for household income effects is constructed in two stages:

Stage 1: Employing Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation, we conduct regression analysis on households’ employment participation decisions. This stage simultaneously estimates both the selection equation (capturing employment participation behavior) and the outcome (Equation 2):

In the model, denotes the vector of factors influencing household employment participation, including individual characteristics, household attributes, typology factors, and regional factors. represents the vector of parameters to be estimated corresponding to these factor categories. is the error term in the behavioral decision equation for employment participation.

In Equations 5, 6, denotes the annual average household income for non-participants in employment. denotes the annual average household income for households participating in employment. represents the vector of factors influencing employment participation (individual characteristics, household attributes, typology factors, and regional factors). and are the parameters to be estimated for the non-participation and participation regimes, respectively. and are the error terms of the outcome equations.

Stage 2: To address estimation bias from unobserved heterogeneity, we incorporate the inverse Mills ratios and computed in Stage 1, along with vectors and . These components are integrated into Equations 3, 4 above, yielding the modified specification:

Parameters and correct for selectivity bias arising from unobserved variables in the non-participation and participation regimes, respectively. Terms and satisfy the zero-mean assumption. We then apply FIML estimation to jointly estimate the above equations, yielding the final simultaneous model (Equation 7):

4.2 Mediation effect model

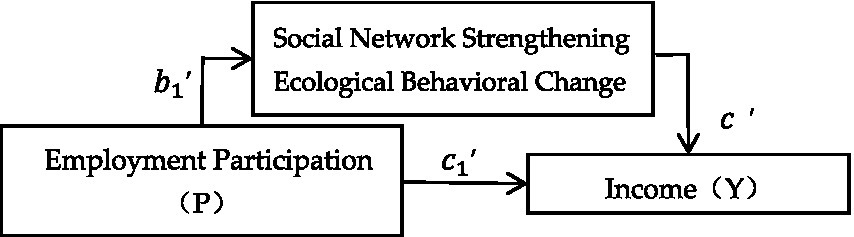

Based on the theoretical postulates presented above, rural households’ off-farm employment participation may influence household income through two underlying pathways: the strengthening of social networks and the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors. To empirically test the mediating effects of social network strengthening and pro-environmental behavior adoption, we conduct mediation analysis on the selected variables (Hayes, 2009; Hayes and Scharkow, 2013). Following the established procedure by Baron and Kenny (1986), the following mediation effect models are constructed:

In this model, denotes the dependent variable (household income), represents the core explanatory variable (off-farm employment participation), signifies the mediator variables (social network strengthening and pro-environmental behavior adoption), and comprises control variables. Equation 8 estimates coefficient , capturing the total effect of employment participation on household income. Equation 9 estimates coefficient , measuring the effect of employment participation on the mediators. In Equation 10, coefficient quantifies the effect of the mediators on household income, while coefficient represents the direct effect. Substituting Equation 9 into Equation 10 yields the mediating effect , the indirect effect reflects how employment participation influences income through the dual pathways of social network strengthening and pro-environmental behavior adoption. Coefficients correspond to control variables, and denotes the stochastic disturbance term.

The path diagrams for testing mediation effects are presented in Figures 3, 4.

Figure 4

The mediating effect of social network strengthening and ecological behavioral change on income. Figure 3 provides a schematic representation without mediators, while figure demonstrates the model incorporating mediating variables.

5 Model estimation results

5.1 Endogeneity testing

Theoretical analysis suggests potential endogeneity arising from selection bias, omitted variables, and reverse causality in income effect models. We therefore employ a Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) approach to test for endogeneity before ESRM estimation, requiring the identification variable to be strongly correlated with the endogenous regressor but orthogonal to the error term. Given that this study employs a single instrumental variable for a single endogenous variable, resulting in an exactly identified model, overidentification tests are not applicable. The identification of the model relies entirely on the exogeneity assumption of this instrumental variable (Wooldridge, 2016; Joshua and Jörn-Steffen, 2010). As presented in Table 3 (Model 1), the first-stage regression yields an F-statistic of 11.13 for joint significance, rejecting the null hypothesis of exogeneity at the 1% level (p < 0.01). Meanwhile, the identification variable-distance to the nearest forest therapy base-significantly predicts employment participation at the 1% level, confirming both instrument relevance and the presence of endogeneity in the core explanatory variable.

Table 3

| Variable | Model 1 (employment, n = 795) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First stage regression | Second stage regression | |||

| Employment | Annual household income | |||

| Coefficient | t-value | Coefficient | t-value | |

| Participation behavior | – | – | −0.6389 | −1.53 |

| Distance to forest health base | 0.0032*** | 3.34 | – | – |

| Control variables | Controlled | Controlled | ||

| F-value | 11.13 | – | ||

Model endogeneity test.

*, **, and *** indicate significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

5.2 Model estimation results

Empirical analysis was conducted using Stata 22.0. Before model estimation, we assessed potential multicollinearity through variance inflation factors (VIF) to prevent estimation bias from high inter-variable correlations. The mean VIF values for the selection equation (employment participation decision) and outcome equation (income effect) were 1.88 and 1.94, respectively, significantly below the threshold of 5, indicating no multicollinearity concerns.

The ESRM estimates for income effects are presented in Table 4 (Model 2). This specification treats forest therapy employment participation as the selection equation outcome and annual household income as the outcome equation dependent variable. Key diagnostics confirm model validity: a statistically significant Wald test statistic of 558.88 (p < 0.01) rejects the null hypothesis of independence between selection and outcome equations, while the log-likelihood value (−649.42) indicates good model fit. The significant non-zero estimates for lnσ₁ and lnσ₀ (both p < 0.01) demonstrate that unobserved variables jointly influence both participation decisions and income outcomes, necessitating selection bias correction through ESRM. This result, coupled with prior endogeneity confirmation (Section 5.1), substantiates ESRM’s appropriateness for causal inference.

Table 4

| Variable Name | Model 2 (Employment, n = 795) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision equation | Outcome equation | ||

| Participated | Not participated | ||

| Gender | 0.6569*** (0.1424) | −0.0312 (0.0440) | 0.0416 (0.0529) |

| Age | 0.1254 (0.0772) | −0.0219 (0.0218) | −0.0189 (0.0268) |

| Personal health status | −0.2453** (0.0984) | 0.0309 (0.0308) | −0.0360 (0.0369) |

| Marital status | 0.4954*** (0.1545) | −0.1314** (0.0445) | −0.0206 (0.0717) |

| Personal life security | −0.1077 (0.0774) | −0.0104 (0.0214) | −0.0129 (0.0338) |

| Residential area | −1.6181*** (0.2201) | −0.0543 (0.0582) | 0.1190 (0.1238) |

| Presence of elderly care facilities | −0.0292 (0.1635) | 0.0665 (0.0507) | −0.1344** (0.0621) |

| Number of household members | −0.2207** (0.0812) | 0.0811*** (0.0244) | 0.0779** (0.0327) |

| Number of children | 0.2811** (0.1138) | −0.0477 (0.0341) | −0.0287 (0.0416) |

| Number of elderly | 0.1883** (0.0838) | −0.0547** (0.0244) | −0.0120 (0.0319) |

| Annual household expenditure | 0.2214 (0.1499) | 0.3803*** (0.0483) | 0.3085*** (0.0511) |

| Per Capita cultivated/forest land area | −0.0508*** (0.0150) | 0.0225*** (0.0046) | 0.0016 (0.0012) |

| Presence of household loans | 0.4452 (0.3009) | −0.1692* (0.0877) | 0.2285 (0.1493) |

| Presence of household savings | 0.2195 (0.1523) | 0.2535*** (0.0514) | 0.1294** (0.0523) |

| Household telephone expenses | 1.0508*** (0.1119) | 0.0683* (0.0401) | 0.2415*** (0.0731) |

| Household social status | −0.5858*** (0.1043) | −0.2146*** (0.0329) | −0.2192*** (0.0407) |

| Household social relations status | 0.0062 (0.0843) | 0.0434* (0.0243) | −0.0001 (0.0279) |

| Agriculture priority type | −1.0515*** (0.2981) | −0.2752*** (0.0777) | −0.5034*** (0.1562) |

| Non-agricultural non-forestry dominant type | −0.2067 (0.3023) | −0.0490 (0.0756) | −0.1366 (0.1509) |

| Hohhot | 1.7298*** (0.5369) | 0.2458 (0.1537) | 0.5993** (0.1979) |

| Ordos | −0.9681** (0.4154) | 0.1946* (0.1052) | −0.2928 (0.3386) |

| Hulunbuir | 0.6141** (0.2718) | −0.0654 (0.1010) | 0.0959 (0.1933) |

| Chifeng | 1.1548*** (0.3364) | 0.0724 (0.0687) | 0.3918*** (0.1202) |

| Tongliao | 0.1160 (0.4763) | 0.0970 (0.0833) | 0.5094*** (0.1363) |

| Distance to forest health base | 0.0270** (0.0092) | – | – |

| Constant | −2.1733 (1.9772) | 7.0771*** (0.6270) | 5.8622*** (0.8693) |

| lns1 | – | −0.8827*** (0.0334) | – |

| r1 | – | −0.0867 (0.1574) | – |

| lns2 | – | – | −0.9033*** (0.0388) |

| r2 | – | – | 0.0945 (0.1709) |

| Log likelihood | −649.4204 | ||

| Wald chi2 | 558.88*** | ||

ESRM model estimation results.

*, **, and *** indicate significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively; non-farming and non-forestry dominant is the control group for the dummy variable for type of farm household, and Ulaanbaatar City is the control group for the dummy variable for regional characteristics. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

5.2.1 Analysis of factors influencing farmer employment participation

Model 2 results indicate that distance to forest therapy bases exerts a significantly negative influence on employment participation decisions at the 1% significance level; among individual characteristics, gender (male) and marital status (married) have significant positive effects at the 1% level, while health status negatively impacts participation at 5% significance and housing area shows negative effects at 1% significance; regarding household attributes, family size negatively influences participation at 5% significance, whereas number of children and elderly dependents both have positive effects at 5% significance; per capita landholding negatively affects participation at 1% significance, communication expenditure demonstrates positive effects at 1% significance, perceived social status reduces participation likelihood at 1% significance, and social capital enhances employment engagement with positive effects.

5.2.2 Analysis of income effect determinants

Model 2 reveals substantial heterogeneity in income determinants between employed and non-employed households: while marital status significantly influences income only for forest therapy employees, gender, age, health status, social security, and log-transformed housing area show no significant effects for both groups; notably, proximity to elderly care institutions reduces income significantly for non-participants (p < 0.05) but shows no effect for employed households. Household attributes demonstrate differential impacts: family size exerts significant positive effects on both employed and non-employed households at 1% significance (β = 0.0811), though the effect magnitude is 0.0032 higher for employed households; number of elderly members reduces income significantly only for employed households, reflecting expenditure pressures despite higher baseline earnings; annual household expenditure positively influences both groups (1% level) but shows 0.0718 stronger effects for employed households; per capita arable land benefits only employed households (1% level), while household loans negatively impact solely employed participants; savings ownership and log-communication expenditure exhibit positive effects for both groups (1%/10% levels), with savings generating larger income gains for employed households and communication expenditure more impactful for non-employed households; perceived social status negatively affects both cohorts (1% level), with stronger effects among employed households; social capital enhances income for employed households at 10% significance, indicating superior network utilization in formal employment contexts.

5.2.3 Average treatment effects of employment participation

Counterfactual estimation based on the ESRM reveals that forest therapy employment generates an ATT of 0.3676 (p < 0.01), signifying a 36.76% increase in income for participating households. Simultaneously, the ATU of 0.6699 indicates non-participating households would achieve 66.99% higher income if they were employed, which represents a 6.44% income loss in their counterfactual scenario (Table 5). This confirms that employment participation significantly boosts household income, with disproportionately larger marginal gains among non-participants due to stable wage income from forest therapy bases and expanding job opportunities driven by the industry’s sustained rapid development, thereby empirically validating Hypothesis H1.

Table 5

| Employment participation | Sample size | Participation behavior | Treatment effect | Change rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participated | Not participated | ATT | ATU | |||

| Participated | 454 | 11.0334 | 10.6657 | 0.3676*** | – | 0.0345 |

| Non-participated | 341 | 11.0657 | 10.3957 | – | 0.6699*** | 0.0644 |

Average treatment effect of the impact of employment Participation on the average annual household income.

*, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5% and 1 percent levels, respectively, and the rate of change is the change in income generated by participating farmers compared to non-participating farmers.

5.3 Robustness checks

To ensure our ESRM results are not unduly influenced by extreme values or the choice of income measure, we conducted two robustness checks.

5.3.1 Winsorization treatment

Following established approaches (Li et al., 2024; Siéwé et al., 2024), all continuous variables excluding binaries were winsorized at the 5th and 95th percentiles to mitigate outlier influence. Re-estimated ESRM results in Table 6 confirm robustness: both the winsorized ATT of 0.4454 and ATU of 0.5701 remain statistically significant at the 1% level, with effect magnitudes consistent with baseline estimates; this affirms the stability of our causal inferences.

Table 6

| Employment participation | Participation behavior | Tail processing | Change rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participated | Not participated | ATT | ATU | ||

| Participated | 11.0096 | 10.5642 | 0.4454*** | – | 0.0422 |

| Non-participated | 10.9776 | 10.4075 | – | 0.5701*** | 0.0548 |

Estimation results of tailed processing model.

*, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5% and 1 percent levels, respectively, and the rate of change is the change in income generated by participating farmers compared to non-participating farmers.

5.3.2 Dependent variable replacement

Consistent with robustness (Rosenfeld et al., 2024; Kong et al., 2024), substituting the dependent variable from annual household income to per capita income yields statistically significant ESRM estimates (Table 7): the ATT is 0.1608 (p < 0.01) and the ATU is 0.3600 (p < 0.01). These results confirm directional consistency with baseline results despite expected magnitude variations, since per capita metrics inherently attenuate income effects by controlling for household size heterogeneity, yet the sustained 1% significance validates the core finding that forest therapy employment generates robust income gains across measurement approaches.

Table 7

| Employment participation | Participation behavior | Replacing explained variables | Change rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participated | Not participated | ATT | ATU | ||

| Participated | 9.8853 | 9.7245 | 0.1608*** | – | 1.65% |

| Non-participated | 9.8050 | 9.4450 | – | 0.3600*** | 3.81% |

Replaces the model estimates for the explained variables.

*, **, and ***, respectively, indicate significance at the levels of 10%, 5% and 1%, and the change rate is the income change brought by the participating farmers compared with the non-participating farmers.

Based on the two robustness checks described above, we found that: First, we winsorized all continuous variables at the 5th and 95th percentiles. The persistence of significant treatment effects (Table 7) indicates that our core findings are robust to potential outliers. Second, we substituted total household income with per capita income. The continued positive and significant effects (Table 8) demonstrate that the benefits of employment are evident even after controlling for household size, reinforcing the validity of our main results.

Table 8

| Variable | Participation in employment (n = 795) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| QR_25 | QR_50 | QR_75 | |

| Intensity of government support (above the mean) | 0.3807*** (0.0557) | 0.3644*** (0.0426) | 0.2895*** (0.0698) |

| Intensity of government support (below the mean) | 0.2696*** (0.0925) | 0.2548** (0.1126) | 0.1527 (0.1253) |

| Control variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

QR results of the influence of different institutional factors on the average annual income of rural households.

*, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. The figures in parentheses are robust standard errors.

5.4 Heterogeneity analysis

Given significant disparities in income effects across farmer typologies and regions identified in prior analyses, we employ quantile regression (QR) proposed by Koenker and Bassett Yuan (2023) to examine heterogeneity at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of annual household income.

5.4.1 Farmer typology heterogeneity

In Table 9, results reveal typology-dependent heterogeneity: for agriculture-oriented households, employment participation significantly boosts income only at the high-income quantile (QR_75, p < 0.05), with no significant effects at median (QR_50) or low-income (QR_25) levels; conversely, for forestry-dependent and non-agricultural/non-forestry-oriented households, participation shows statistically insignificant effects across all income quantiles, demonstrating divergent impacts of farmer typologies on income distribution. The underlying reason may lie in the varying resource endowments, risk tolerance, and market participation levels among different livelihood typologies. Agriculture-oriented households, being more dependent on land and agricultural income, experience significant income enhancement effects from wage employment—particularly pronounced among middle and high-income cohorts. Conversely, forestry-dependent and non-agricultural/non-forestry-oriented households exhibit limited responsiveness to seasonal employment due to unstable income streams or lower land dependency, resulting in statistically insignificant effects.

Table 9

| Variable | Participation in employment (n = 795) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| QR_25 | QR_50 | QR_75 | |

| Agriculture priority type | 0.1477 (0.0938) | 0.1021 (0.1023) | 0.1889* (0.1083) |

| Forestry dependent type | −0.0490 (0.1793) | −0.0339 (0.0636) | −0.0061 (0.1561) |

| Non-agricultural non-forestry dominant type | 0.1754 (0.1307) | 0.1158 (0.0933) | 0.0085 (0.1743) |

| Control variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

QR results of the impact of different types of farmers on the average annual household income of farmers.

*, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. The figures in parentheses are robust standard errors.

5.4.2 Regional heterogeneity

Results demonstrate considerable regional heterogeneity in employment participation effects on household income (Table 10). In western regions, participation significantly boosts income for low-income households (QR_25, β = 0.4491, p < 0.01), indicating that each unit increase in employment raises income by 0.4491 units, while showing no significant effects on median (QR_50) or high-income (QR_75) households. Conversely, in eastern regions, participation exerts significant positive effects on both median (QR_50, β = 0.2094, p < 0.01) and high-income (QR_75, β = 0.1890, p < 0.05) households, with the strongest impact observed at the median income level—exceeding the high-income quantile effect by 2.04 percentage points. The underlying mechanism may stem from divergent income structures and risk tolerance across regional household types. Higher-income households tend to prioritize non-forest therapy employment for capital accumulation and scale operations, whereas lower-income households rely more heavily on stable local jobs. Consequently, regional income disparities further amplify the heterogeneity of policy impacts.

Table 10

| Variable | Participation in employment (n = 795) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| QR_25 | QR_50 | QR_75 | |

| Western region | 0.4991*** (0.1548) | 0.3566 (0.2207) | 0.1022 (0.2774) |

| Eastern region | 0.0863 (0.0635) | 0.2094*** (0.0542) | 0.1890*** (0.0655) |

| Control variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

QR results of the impact of different types of farmers on the average annual household income of farmers.

*, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. The figures in parentheses are robust standard errors.

5.4.3 Institutional factors heterogeneity

From an institutional perspective, as shown in Table 8, the impact of employment participation on annual household income is significantly influenced by institutional factors (government support). Government support was selected as the measurement indicator for the institutional factor. It was operationalized using the level of satisfaction with the construction of infrastructure surrounding forest therapy bases. The variable was assigned values based on a five-point Likert scale: very satisfied = 5, satisfied = 4, neutral = 3, dissatisfied = 2, and very dissatisfied = 1. Heterogeneity analysis was conducted by dividing the sample into two groups: those with government support above the mean (1.8478) and those below the mean (1.8478).

In the group with higher government support, employment participation has a statistically significant effect on low-income (QR_25), middle-income (QR_50), and high-income (QR_75) households at the 1% level. In terms of the magnitude of the effect, government support has the strongest impact on low-income (QR_25) households. In the group with lower government support, employment participation has a significant effect on low-income (QR_25) and middle-income (QR_50) households at the 1 and 5% levels, respectively, but the effect on high-income (QR_75) households is not significant. The possible reasons are as follows:

First, institutional support effectively lowers the participation threshold for low-income groups. Areas with higher government support typically feature well-developed infrastructure (e.g., roads, communication, water, and electricity supply) and better public services (e.g., skills training, market information dissemination). These supporting measures significantly reduce the fixed costs and information barriers for low-income households to participate in forest therapy employment, enabling them to engage more easily and benefit from it. For high-income groups, they may already possess certain capital and social resources to overcome these barriers, so the marginal effect of institutional support is relatively lower.

Second, high-income households have more diversified income sources and thus rely less on a single institutional factor. High-income households typically have a more diversified income portfolio (e.g., agricultural operations, business investments, migrant work, etc.), and forest therapy employment is only one of their income sources. Therefore, even in areas with lower government support, they may compensate for income fluctuations through other channels, leading to non-significant estimated results. In contrast, low-income households have more singular livelihood strategies and higher dependence on local employment opportunities, making them more susceptible to the institutional environment.

5.5 Mechanism analysis

5.5.1 Mediating effect of social network reinforcement

Model 3 (Table 11) establishes a significant positive effect of employment participation on income. Model 4 reveals a significant negative impact of participation on social network reinforcement. In Model 5, introducing the mediating variable shows a Sobel test p-value < 0.05 for the pathway participation → social network strengthening → income, with a mediation effect proportion of 38.80%. This confirms that social network reinforcement functions as a partial positive mediation. This indicates employment participation indirectly enhances household income through strengthened social networks, thereby validating the operational logic of this pathway, where employment participation ultimately improves income through social network reinforcement. These results empirically validate Hypothesis H2.

Table 11

| Transmission path | Participation behavior | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Sobel test (p-value) | Mediating effect proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Social network strengthening | Income | ||||

| Employment → Social network Strengthening → Income | Employment | 0.0930** (0.0457) | −0.1426** (0.0660) | 0.0569 (0.0427) | 0.0361 (0.0340) | 38.80% |

| Social network strengthening | – | – | −0.2531*** (0.0233) | |||

| Control variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | |||

| Constant | 5.7496*** (0.7421) | 5.8330*** (1.0708) | 7.2257*** (0.7046) |

Sobel test on the mediating effect of social network strengthening.

*, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

5.5.2 Mediating effect of ecological behavioral change

Model 6 (Table 12) establishes a significant positive effect of employment participation on income. Model 7 reveals a significant positive impact of participation on ecological behavioral change. In Model 8, introducing the mediating variable shows a Sobel test p-value = 0.0117 for the pathway participation → ecological behavior change → income, with a mediation effect proportion of 27.05%. This confirms that ecological behavioral change functions as a positive mediator and exhibits a partial mediating role: participation enhances ecological practices, thereby amplifying direct income benefits. These results empirically validate Hypothesis H3.

Table 12

| Transmission Path | Participation behavior | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Sobel test (p-value) | Mediating effect proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Ecological behavioral change | Income | ||||

| Employment → Ecological behavior change → Income | Employment | 0.0930** (0.0457) | −0.4501*** (0.0839) | 0.1182*** (0.0463) | −0.0251 (0.0117) | 27.05% |

| Ecological Behavior Change | – | – | 0.0559*** (0.0196) | |||

| Control Variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | |||

| Constant | 5.7496*** (0.7421) | 0.1939 (1.3626) | 5.7387*** (0.7387) |

Sobel test results of mediating effects of ecological behavior change.

*, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

6 Discussion and policy implications

6.1 Key findings and theoretical interpretation

This analysis reveals a complex landscape of income effects generated by forest therapy employment, characterized by two core structural tensions.

First, we identify a pronounced heterogeneity in benefits. While the average treatment effect is significantly positive (ATT = 0.3676), the gains are not uniformly distributed. The fact that agriculture-oriented households only experience significant income increases at the highest quantile (QR_75) suggests the existence of firm occupational mismatch barriers. This finding aligns with human capital theory, which posits that low-skilled or elderly laborers often lack the specific skills (e.g., hospitality, healthcare) required by the service-oriented forest therapy sector (Tang et al., 2024). Consequently, they may be relegated to lower-paying, temporary roles, limiting their income upside. This finding contrasts with the existing literature, which predominantly focuses on the general income-boosting effect of tourism on farmers, but fails to analyze the differential impacts of employment in forest therapy bases on farmers with different income levels. Conversely, the high income elasticity for low-income households in western regions (β = 0.4491 at QR_25) underscores the role of employment as a critical income safeguard in less developed areas. This supports the theory of spatial poverty traps, wherein localized employment opportunities can effectively reduce vulnerability by lowering transaction costs and providing stable wage income (Wu et al., 2023). This finding strongly aligns with studies on pro-poor tourism (Wang W. et al., 2021), confirming the potential of localized eco-industries to serve as a safety net in marginalized regions.

Second, we observe a divergent functioning of mediation pathways across regions. The positive mediating role of ecological behavior (27.05%) confirms that environmental education and practice can translate into economic value. However, the stark regional divergence—with eastern regions leveraging certification premiums and western regions hindered by technical constraints—echoes the concept of “capability deprivation” advanced by Sen (Li F. D. et al., 2021). Eastern households, likely endowed with better market access, knowledge, and capital, can convert pro-environmental actions into premium prices. Western households, despite similar engagement, lack the technical and institutional support to achieve the same conversion efficiency, leading to a potential reinforcement of regional inequalities. Conventional literature often examines the heterogeneity of farmers’ income from a regional perspective (Lu et al., 2017). In doing so, we delve into the mechanism through which forest therapy employment influences farmers’ income, rather than merely identifying regional disparities.

6.2 Policy implications

To address these challenges, three targeted strategies are proposed. The practical implications of this research are primarily intended for policymakers and rural development practitioners seeking to leverage green industries for sustainable revitalization. The findings directly benefit the following key group: low-income and agriculture-oriented households in western China, for whom forest therapy employment can serve as a vital income safeguard. First, Subject Capacity Reengineering through a “Skill Binding Program” that provides youth with forest therapy certification training alongside three-year local employment contracts to reduce outmigration rates, while establishing digital linkage platforms to distribute homestay partnerships and organic orders, thereby converting social networks into income channels. Second, enact Regionally Coordinated Interventions by introducing a “Public Welfare Forest Ranger Positions + Direct Carbon Sink Payments” bundle for western low-income groups to cover elderly and low-skill laborers, while piloting “Carbon Sink Revenue Rights Pledge Loans” in eastern regions to support family farms’ understory economies. Third, Industrial System Innovation via a “Green Points-Forest Therapy Voucher” exchange system, incentivizing eco-behaviors, promoting the “Sanming Forest Share” model, distributing carbon revenues based on participation, deepening collective forest tenure reforms through digital forest rights certification to reduce land transfer costs.

7 Research conclusions and prospects

7.1 Research conclusions

This study empirically examines the income effects of farmer employment participation in forest therapy bases using ESRM based on survey data from 795 non-migrant households surrounding forest therapy bases. With employment participation as the explanatory variable, annual household income as the dependent variable, distance to forest therapy bases as the identification variable, and individual/household/typological/regional characteristics as control variables. The analysis yields three central conclusions:

First, forest therapy employment generates a significant and positive income effect. The Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) of 0.3676 confirms that participation significantly increases household income. Furthermore, the substantial potential gain for non-participants (Average Treatment Effect on the Untreated – ATU) highlights the industry’s untapped potential for poverty alleviation.

Second, the benefits are characterized by pronounced heterogeneity. The impact follows an inverted U-shaped curve, peaking at median income quantiles (QR_50). Agriculture-oriented households benefit primarily at high-income levels (QR_75), suggesting skill-based barriers for others. Geographically, western regions show strong effects for low-income households (QR_25), functioning as an income safeguard, while eastern regions see the strongest impacts at median income levels (QR_50), indicative of more mature market integration. In the group with higher government support, employment participation has a statistically significant effect on low-income (QR_25), middle-income (QR_50), and high-income (QR_75) households at the 1% level. In terms of the magnitude of the effect, government support has the strongest impact on low-income (QR_25) households. In the group with lower government support, employment participation has a significant effect on low-income (QR_25) and middle-income (QR_50) households at the 1 and 5% levels, respectively, but the effect on high-income (QR_75) households is not significant.

Third, the mechanisms of income enhancement operate through dual pathways. Mediation analysis confirms that both social network reinforcement (38.80% mediation) and ecological behavioral change (27.05% mediation) serve as significant partial mediators. This indicates that employment boosts income not only directly through wages but also indirectly by strengthening social capital and incentivizing pro-environmental practices that carry economic value.

Most importantly, this study moves beyond merely establishing a correlation to unpack the ‘how’ and ‘for whom’ of income effects in forest therapy. Our primary contribution lies in empirically validating and quantifying the dual mediation pathways of social networks and ecological behavior—a mechanism often hypothesized but rarely tested in this context. Furthermore, by revealing the significant heterogeneity across household types and regions, we challenge one-size-fits-all approaches to green employment and provide a nuanced evidence base for targeted policymaking. The key practical implication is that maximizing the benefits of forest therapy requires not only creating jobs but also fostering complementary capabilities tailored to different segments of the rural population.

7.2 Research limitations and future prospects

Despite the study’s contributions, several limitations remain. First, the theoretical framework inadequately incorporates spatial-institutional interactions, failing to explain the threshold effects of base density on income growth. Second, cross-sectional data constraints preclude capturing dynamic “participation-income” evolution across industry cycles. Third, regional heterogeneity neglects differential gains in ecological behavior transformation between arid/semi-arid zones and humid zones; Fourth, certain variables may be subject to measurement errors. For instance, constructs such as farmers’ social status and trust level were measured using 5-point Likert scales, without fully accounting for potential measurement inaccuracies and resultant biases.

Building on these findings and limitations, we propose the following concrete pathways for future research:

First, to address spatial-institutional interactions, future studies should employ spatial econometric models to quantify the spillover effects and optimal density thresholds of forest therapy bases. Research could investigate how specific policies, such as subsidies or infrastructure investments, interact with geographic clustering to influence income outcomes.

Second, to overcome the constraints of cross-sectional data, a longitudinal cohort study tracking the same households over 3–5 years is essential. This design would capture how income effects evolve as the industry matures, distinguishing between short-term boosts and sustainable long-term lifts, and clarifying the dynamic causal pathways.

Third, regarding regional ecological heterogeneity, future work should conduct comparative case studies between arid and humid zones, integrating remote sensing data on ecological quality with household surveys. This would help quantify the “green premium” for eco-products in different regions.

Finally, to mitigate measurement error, subsequent research should adopt mixed-methods approaches. For perceptual variables, validated multi-item scales and triangulation with behavioral data can enhance reliability. For key outcomes like income, combining surveys with financial diaries or official records would improve accuracy.

Furthermore, to directly address the limited generalizability of this study to migrant households, future research should explicitly incorporate and compare both migrant and non-migrant households within a unified framework. Such a design would test whether forest therapy employment generates differential income effects across migration status and help identify specific barriers that may limit participation or benefits for migrant families. A comparative approach could offer practical insights into how to extend the poverty-reduction potential of forest therapy to more diverse rural populations.

By pursuing these targeted research agendas, scholars can build a more robust and dynamic understanding of the forest therapy industry’s role in rural sustainable development, ultimately leading to more precise and effective policy interventions.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

HL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MA: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. HM: Writing – original draft. YT: Visualization, Writing – original draft. QB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft. JZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. CX: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. LZ: Validation, Writing – review & editing. YG: Writing – original draft. ZF: Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the following funding sources: (1) The Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Grant no. 2023MS07004), which provided financial support for data collection and analysis; (2) The Fundamental Research Funds for the Directly Affiliated Universities of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China (Grant no. BR231301), which supported the research activities of the Innovation Team for Forest-Grass Resource Economics and Ecological Security, as well as the publication expenses (APC) of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/ffgc.2026.1784360.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ajzen I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process.50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

2

Baltic R. Kowalski J. Nowak A. (2023). Income effects of forest therapy participation: evidence from Poland using ESRM. Forests14:1321. doi: 10.3390/f14071321

3

Baron R. M. Kenny D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173,

4

Chen M. Y. Huang S. X. Zhang F. Dang J. J. Xia K. Y. Chen Z. et al . (2021). Research on the impact effect of agricultural green production technology adoption on farmers' income. J. Ecol. Rural Environ.37, 1310–1317. doi: 10.19741/j.issn.1673-4831.2021.0175

5

Chen Y. Liu D. J. Wang W. Tang H. (2023). Study on the accessibility and influencing factors of forest therapy bases in Sichuan Province. J. Green Sci. Technol.25, 172–178. doi: 10.16663/j.cnki.lskj.2023.15.016

6