Abstract

Background:

Climate change mitigation strategies increasingly focus on carbon trading, with agroforestry systems presenting promising opportunities for carbon sequestration while supporting sustainable livelihoods. The Nilgiris district in India, with its rich biodiversity and significant scheduled caste population dependent on agriculture, offers a unique context for such initiatives.

Methods:

Following PRISMA guidelines, we conducted a systematic literature review analyzing 80 articles from Web of Science and Scopus databases (2015–2025). The research employed bibliometric and thematic analyses to examine carbon sequestration potential through agroforestry systems in the Nilgiris, focusing on quantification approaches and economic valuation.

Results and conclusion:

Agroforestry systems in the Nilgiris can sequester carbon at rates of 0.25–19.14 Mg C/ha/year in tree components and 0.01–0.60 Mg C/ha/year in crop components, with variation based on system design, species composition, and management practices. Agro-horticulture systems showed the highest potential (38.11 Mg C/ha), 31.64% higher than conventional agriculture. Economic analyses revealed agroforestry systems to be approximately four times more profitable than monoculture even without carbon revenues, with carbon pricing further enhancing profitability. The research proposes a methodological framework for carbon trading in the Nilgiris, addressing key challenges including high transaction costs, methodological complexities, and equitable benefit-sharing. Our proposed framework combines environmental conservation goals with community welfare by linking carbon storage and income generation opportunities. The context of our study focussed on the carbon measurement protocols and the need of an affordable monitoring system for the resource poor areas.

Highlights

-

Agroforestry systems in Nilgiris impounds 0.25–19.14 Mg C/ha/year in trees, enhancing carbon stocks.

-

Agro-horticulture systems show highest carbon potential at 38.11 Mg C/ha, which is 31.64% above conventional agriculture.

-

Agroforestry systems are 4x times more profitable than monoculture, even without carbon revenue benefits.

-

High transaction costs and methodological complexities remains key challenges for carbon trading.

-

The Methodological Framework of the study integrates ecological, social, and economic dimensions for both carbon and livelihood benefits.

1 Introduction

Climate change represents one of the most significant environmental challenges of our time, with greenhouse gas emissions continuing to rise despite global mitigation efforts (Costanza et al., 2014). Carbon dioxide (CO₂) remains a primary contributor to global warming, prompting the development of various strategies to reduce atmospheric carbon concentration. In this context, carbon trading has emerged as a market-based approach to mitigate climate change by providing economic incentives for reducing carbon emissions while promoting sustainable development (Chen et al., 2020). Soil organic carbon (SOC) is an important parameter to study the carbon cycle as soil carbon stock inventory as well as to serve as prime indicator in assessing soil health and soil quality (Kumar et al., 2019). Habitat loss and degradation are main global threats to biodiversity, and land-use changes in agriculture-dominated landscapes are crucial for an important portion of biodiversity (Brambilla et al., 2017). Agroforestry systems—which integrate trees with crops and/or livestock—have gained recognition for their substantial carbon sequestration potential while simultaneously supporting biodiversity conservation and rural livelihoods (Dhyani et al., 2016; Murthy et al., 2013). Sudmeyer et al. (2012) says Mallee-based agroforestry has potential to provide farmers with new income sources derived from biofuels, biofeedstocks, and carbon sequestration. In India, agroforestry systems occupy approximately 25.32 million hectares (8.2% of the total geographical area), presenting significant opportunities for enhancing carbon sequestration at the national level while addressing multiple sustainable development goals (Dhyani et al., 2016). Udawatta et al. (2019) found that integration of Agroforestry can improve biodiversity in agricultural lands. Selection of site suitable tree/shrub/grass-crop combinations can be used to help address soil nutrient deficiencies or environmental conditions.

Recent research across India and neighboring South Asian countries has significantly advanced our understanding of carbon sequestration potential in diverse agroforestry systems. In the Western Ghats region, studies by Ramachandra and Bharath (2020) reported carbon stocks ranging from 45 to 120 Mg C/ha in mature agroforestry systems, with significant variations based on species composition and management practices. Similarly, investigations in the Himalayan foothills by Kumar et al. (2019) documented carbon sequestration rates of 2.5–8.5 Mg C/ha/year in traditional agroforestry systems integrating native tree species. Studies from Peruvian Amazon by Arellanos et al. (2025) found that shade-grown coffee plantations sequester 30–50% more carbon compared to sun-grown monocultures. A study conducted by Negash et al. (2013) in Ethiopia revealed that the coffee stem accounted for most (56%) of plant biomass, followed by branches (39%) and twigs plus foliage (5%). Regional studies from neighboring countries provide valuable comparative context. The comprehensive analysis by Chaulagain et al. (2024) on land use change and carbon sequestration in Nepal using Markov Chain and InVEST models projected carbon storage in 2000 and 2019 were 1.237 and 1.271 billion tons, respectively, with a projected increase to 1.347 million tons by 2050. Rimhanen et al. (2016) found that Agroforestry for 6–20 years led to 11.4 Mg ha−1 and restrained grazing for 6–17 years to 9.6 Mg ha−1 greater median soil carbon stock compared with the traditional management. Carbon sequestration between 2000 and 2019 amounted to 34.141 million tons, which is anticipated to surge to 76.07 million tons from 2019 to 2050, translating to economic valuations of 110.909 and 378.645 million USD, respectively. Forests emerged as pivotal in carbon storage, exhibiting higher carbon pooling than other land use types, expanding from 37 to 42% of the total land area from 2000 to the predicted year 2050. Ahirwal et al. (2021) found that significant alteration in soil quality parameters (decreases/increases based on the individual parameter) in converted land use. Compared to NFS, soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks decreased by 84% in AMS and 50% in AGS, soil CO2 efflux increased by 35% in AGS and decreased by 43% in AMS, attributed to differences in vegetation and microbial activities among sites. Dewar and Cannell (1992) demonstrated that Time-averaged, total carbon storage (at equilibrium) was generally in the range 40–80 Mg C ha−1 in trees, 15–25 Mg C ha−1 in above- and belowground litter, 70–90 Mg C ha−1 in soil organic matter and 20–40 Mg C ha−1 in wood products (assuming product lifetime equalled rotation length). A study from Bangladesh by Hanif et al. (2015) revealed the carbon sequestration potential of three agroforestry species varied from 115 to 135 Mg C/ha/year at the age of 7 years after plantation. Among the agroforestry tree species, L. leucocephala sequestrated maximum amount (135 Mg C/ha/year) of carbon from the atmosphere followed by M. azedarach (120 Mg C/ha/year) and A. lebbeck (115 Mg C/ha/year). Kumar and Sharma (2015) found that average Total Biomass Density (TBD) and Total Carbon Density (TCD) of the Balganga Reserved Forest (BRF) are 23% more when compared to forests located in the same ecoregion due to difference in diameter at breast height and height of tree species. Carrión-Prieto et al., 2017 work on mediterranean shrubs Cistus ladanifer L. and Erica arborea L deemed to be promising for ecological restoration and carbon offsetting.

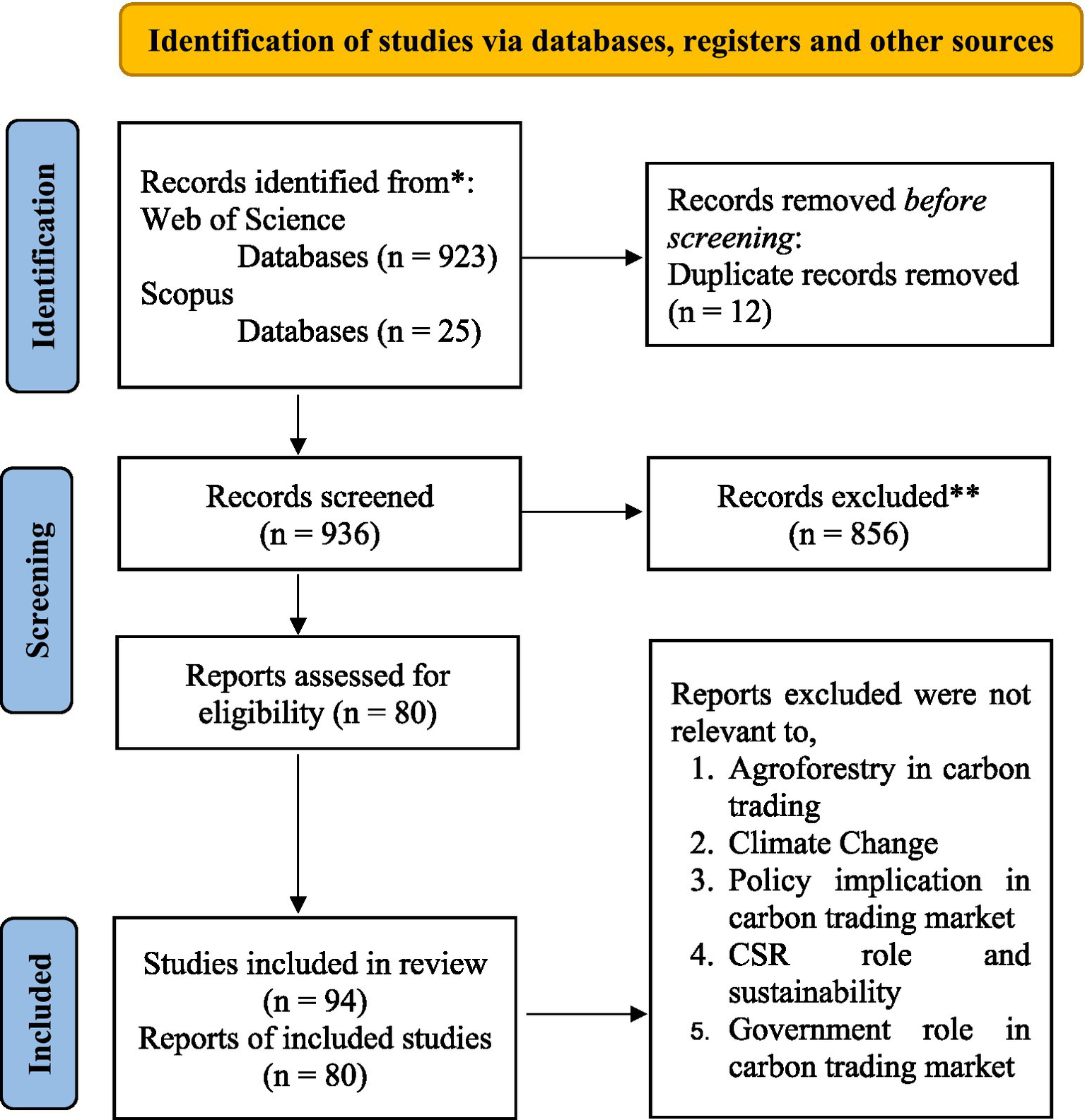

Despite the growing body of literature on carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems, there remains a significant knowledge gap regarding the specific potential and implementation challenges. First, most studies focus on single agroforestry systems in specific ecological contexts, lacking comprehensive systematic reviews that synthesize findings across diverse systems and regions. Second, there is limited research integrating carbon sequestration potential with economic viability and social equity considerations, particularly for marginalized communities. Third, methodological standardization for quantifying carbon in complex agroforestry systems remains challenging, hampering comparability across studies. Fourth, implementation frameworks for carbon trading that address transaction costs, benefit-sharing mechanisms, and community participation are largely absent from the literature. Finally, research specific to biodiversity hotspots like the Western Ghats, particularly focusing on marginalized populations’ livelihoods, is scarce. The present systematic review addresses these gaps by examining carbon trading opportunities specifically for the Nilgiris district context, integrating ecological, economic, and social dimensions within a standardized PRISMA framework. This potential has positioned agroforestry as a crucial pathway toward carbon neutrality in India’s climate strategy. In the present study we analyzed 80 articles from Web of Science and Scopus databases to examine the carbon sequestration potential of different agroforestry systems, economic valuation approaches, implementation challenges, and policy frameworks relevant to the Nilgiris context (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram showing the systematic review process for identifying relevant literature on carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems. Source: Page et al. (2021).

The review is organized into four main sections:

-

1) Carbon sequestration potential of agroforestry systems in global, Indian, and Nilgiris-specific contexts;

-

2) Economic valuation approaches and profitability comparisons;

-

3) Nilgiris-specific ecological and social context for carbon trading; and

-

4) Policy and implementation frameworks.

Through this comprehensive analysis, we aim to provide practical recommendations for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners working on carbon trading initiatives in the Nilgiris and similar regions worldwide.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study area

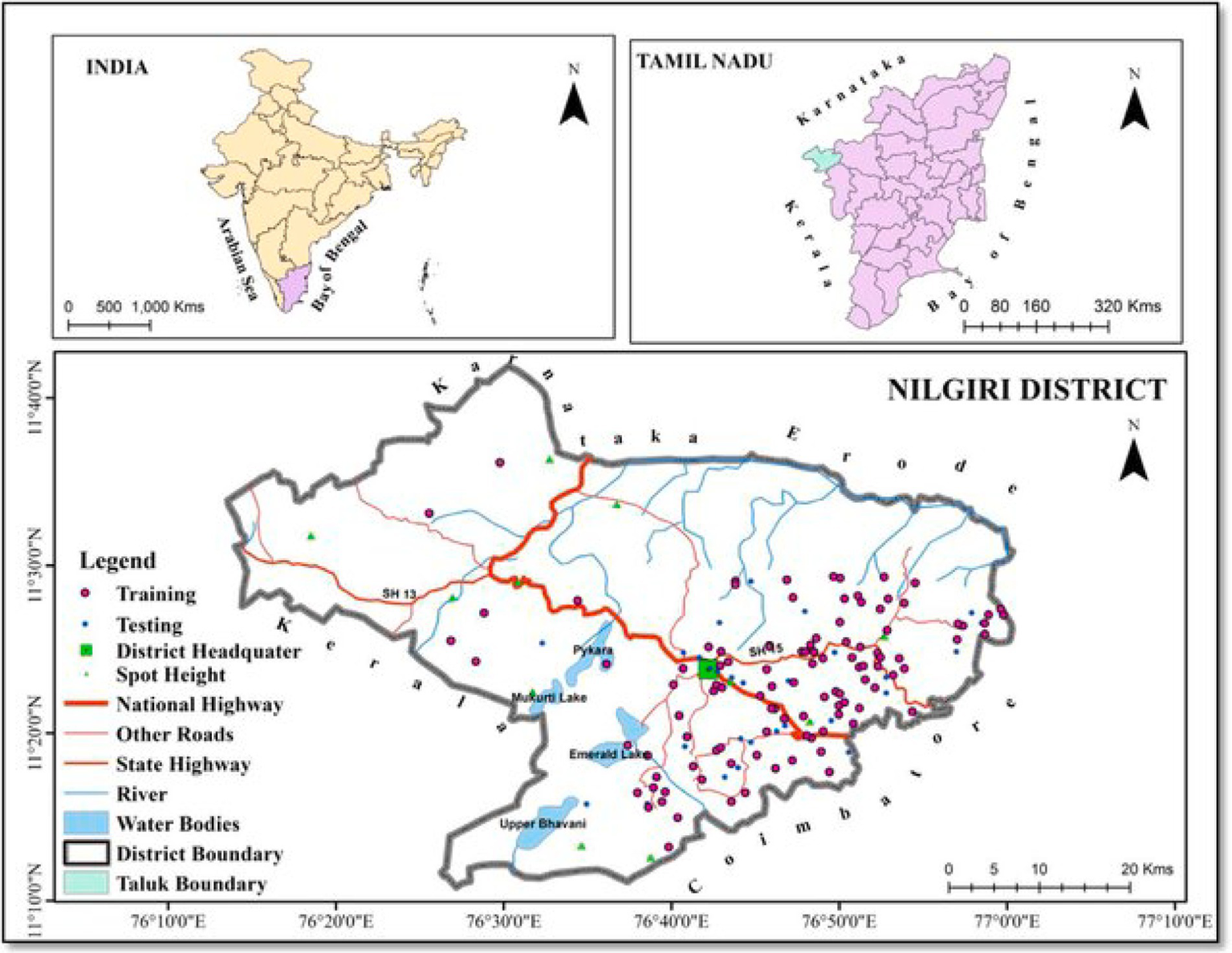

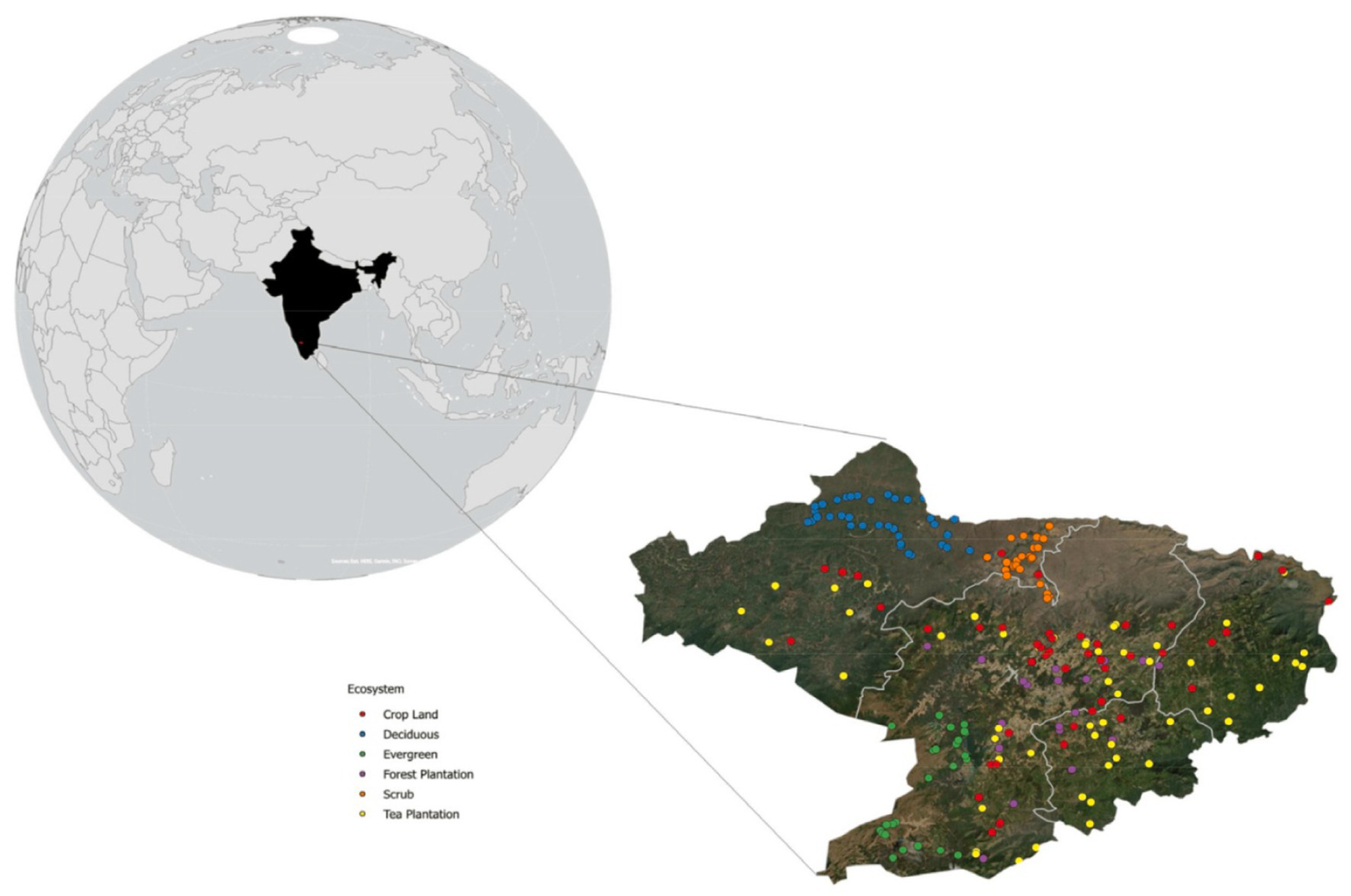

The Nilgiris district is located in the northwestern part of Tamil Nadu state, India, forming part of the Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot (11°08′ to 11°32’ N latitude and 76°27′ to 77°00′E longitude). The district covers an area of 2,549 km2 with elevations ranging from 900 to 2,636 meters above mean sea level, creating diverse ecological zones from subtropical forests at lower elevations to temperate grasslands and montane forests at higher altitudes. The region experiences a tropical montane climate with annual rainfall ranging from 1,500 to 3,000 mm, distributed across both southwest monsoon (June–September) and northeast monsoon (October–December) periods. Mean annual temperatures vary from 15 °C to 20 °C, with occasional frost in winter months at higher elevations. This unique climate supports diverse vegetation types including tropical wet evergreen forests, subtropical montane forests, temperate grasslands (shola-grassland ecosystem), and extensive plantation crops (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Study area map showing the Nilgiris district at National and Local Scales. Source: Yuvaraj and Dolui (2021).

The district’s population of approximately 735,000 (2011 Census) includes a significant proportion of marginalized communities. Scheduled Castes constitute 32.08% of the population, one of the highest proportions in Tamil Nadu. Scheduled Tribes, including indigenous communities such as Toda, Kota, Kurumba, Irula, and Paniyan, comprise about 5% of the population. These communities have historically depended on agriculture, forest resources, and plantation labor for their livelihoods.

Land use in the Nilgiris is dominated by tea plantations (approximately 35% of geographical area), followed by reserved forests (30%), vegetable cultivation (15%), and other crops including potato, carrot, and coffee. Small and marginal farmers (holding less than 2 hectares) constitute 68% of agricultural households. Many scheduled caste and tribal families practice subsistence agriculture on marginal lands with limited access to irrigation and modern inputs. This socioeconomic profile makes the district particularly suitable for carbon trading initiatives that could provide additional income sources for vulnerable populations while promoting environmental conservation.

2.2 Systematic review protocol

This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). PRISMA provides a standardized framework for conducting and reporting systematic reviews, ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor. Originally developed for healthcare research, PRISMA has been successfully adapted across disciplines, including environmental science, agriculture, and natural resource management.

2.2.1 Advantages of PRISMA

The PRISMA framework offers several key advantages for systematic literature reviews. First, it ensures transparency by requiring detailed documentation of search strategies, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and data extraction procedures, enabling other researchers to replicate the review. Second, it minimizes bias through systematic screening processes and explicit quality assessment criteria. Third, PRISMA’s structured approach enhances reproducibility, as the 27-item checklist and flow diagram provide clear standards for each review stage. Fourth, the framework facilitates comprehensive coverage of relevant literature by encouraging systematic searches across multiple databases. Finally, PRISMA has gained widespread acceptance in academic publishing, with many journals requiring compliance for systematic review submissions (Page et al., 2021).

2.2.2 Limitations and considerations

While PRISMA provides a robust framework, we acknowledge several limitations. The systematic review process is time-intensive, requiring 3–6 months for comprehensive literature searches, screening, and data extraction. Publication bias may affect results, as positive findings are more likely to be published than null results. Language restrictions (English-only in our case) may exclude relevant studies published in other languages, potentially affecting geographic representation. Furthermore, heterogeneity in study designs, measurement methods, and reporting standards across the included literature can complicate synthesis and meta-analysis.

2.2.3 Alternative frameworks

We considered several alternative systematic review frameworks. The Reporting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses (ROSES) protocol, developed specifically for environmental topics, offers detailed guidance for conservation and environmental management reviews. However, ROSES is less widely recognized in interdisciplinary research spanning social and economic dimensions. The Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE) guidelines provide excellent standards for environmental systematic reviews but emphasize experimental and quasi-experimental studies, which are less common in agroforestry carbon research. The Campbell Collaboration framework excels for social science reviews but lacks specific guidance for integrating biophysical and economic analyses.

2.2.4 Justification for PRISMA selection

We selected PRISMA as the most appropriate framework for several reasons. First, PRISMA’s broad disciplinary acceptance makes it suitable for our interdisciplinary review spanning environmental science, economics, and social dimensions. Second, its flexible structure accommodates diverse study designs, from quantitative carbon assessments to qualitative policy analyses. Third, PRISMA’s widespread recognition enhances the review’s credibility and accessibility to diverse audiences, including researchers, policymakers, and practitioners. Fourth, the standardized reporting format facilitates comparison with other systematic reviews in carbon sequestration and agroforestry. Finally, previous successful applications of PRISMA in agroforestry research demonstrate its effectiveness for this research domain (Tranchina et al., 2024).

2.3 Search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search across two major academic databases: Web of Science and Scopus. These databases were selected for their extensive coverage of environmental science, agricultural research, and forestry literature. To identify relevant literature, we employed the following search string: (“Carbon trading” OR “carbon sequestration”) AND (“agroforestry” OR “forest conservation”) AND “sustainable development.” This search string was specifically designed to capture studies addressing the intersection of carbon sequestration mechanisms with agroforestry systems in contexts relevant to sustainable development.

2.4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For Web of Science, the following inclusion criteria were applied: Document type: Articles only; Language: English (3,954 articles); Open Access: All (1,666 articles); Research Areas: Environmental Sciences & Ecology, Science Technology & Topics, Agriculture, Forestry, Biodiversity Conversions, Water Resources, Social Sciences & Other Topics. For Scopus, similar criteria were applied: Document type: Articles only (64 articles); Language: English (110 articles); Source type: Journal (84 articles); Open Access: All (35 articles). The initial search yielded 3,996 articles from Web of Science and 111 articles from Scopus. After applying the inclusion criteria, 923 articles from Web of Science and 25 articles from Scopus remained, totaling 948 articles. After removing duplicates, 936 unique articles were identified for screening.

Articles were excluded if they primarily focused on: areas outside the intersection of agroforestry with carbon trading/sequestration; generic climate change topics without specific focus on the search criteria; shipping, cold chain logistics, and carbon trading mechanisms without agroforestry context; policy implications for carbon trading without agroforestry/forest conservation context; government role in carbon trading market without sustainable development aspects; supply chain emission reduction outside the forest/agroforestry context; building mechanisms in carbon trading; Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and general sustainability without forest context; thermal power carbon reduction and other industrial applications without forest relevance. After applying these exclusion criteria through abstract and full-text screening, 856 articles were excluded, resulting in a final dataset of 80 articles for analysis.

2.5 Data analysis

We employed a mixed-methods analytical approach combining quantitative bibliometric and meta-analytic techniques with qualitative thematic synthesis. This multi-faceted strategy enabled comprehensive assessment of both quantitative carbon sequestration metrics and qualitative aspects of implementation frameworks.

2.5.1 Bibliometric analysis

Bibliometric analysis examined publication trends, geographic distribution, citation networks, and journal distribution. We used VOS viewer (version 1.6.18) for visualization of co-authorship networks, keyword co-occurrence, and citation relationships. The Bibliometrix R package (version 4.1.0) facilitated temporal trend analysis, impact assessment (h-index, g-index), and identification of influential authors and institutions. Publication trends were analyzed using linear regression to identify growth rates in research output over the 2015–2025 period. Geographic distribution was mapped using author affiliations and study locations extracted from each article.

2.5.2 Network analysis

Network analysis identified distinct research clusters within the literature corpus. We employed community detection algorithms (Louvain method) to group articles based on citation patterns and keyword similarity. Co-citation analysis revealed influential works and theoretical foundations. Keyword co-occurrence mapping identified thematic relationships and emerging research frontiers. Clustering results were validated through manual review of cluster assignments, with disagreements resolved through author consensus. Each cluster was characterized by predominant themes, methodological approaches, and geographic focus.

2.5.3 Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis followed a systematic coding framework adapted from Braun and Clarke (2006). Two researchers independently reviewed all included articles, identifying recurring themes through open coding. Initial codes were grouped into preliminary themes through axial coding. The research team then refined themes through iterative discussion, ensuring internal homogeneity (coherence within themes) and external heterogeneity (distinctiveness between themes). Four major themes emerged: (1) carbon sequestration potential quantification, (2) economic valuation methodologies, (3) Nilgiris-specific contextual factors, and (4) policy and implementation frameworks. Sub-themes were identified within each major theme, with representative quotes extracted to illustrate key concepts.

2.5.4 Meta-analysis

Quantitative carbon sequestration data were extracted from 37 studies reporting comparable metrics. We standardized all measurements to Mg C/ha/year to enable comparison across studies. For studies reporting biomass rather than carbon content, we applied a conversion factor of 0.5 (carbon constitutes approximately 50% of biomass). When studies reported carbon stocks at different time points, we calculated annual sequestration rates. Summary statistics (mean, median, range, standard deviation) were computed for different agroforestry system types, tree species categories, and geographic regions. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using I2 statistics. Given substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 75%), we present ranges rather than pooled estimates and conduct subgroup analyses to explore sources of variation. Sensitivity analyses examined the influence of study duration, sample size, and measurement methods on reported sequestration rates.

2.5.5 Economic analysis

Economic data were synthesized to compare profitability between agroforestry and monoculture systems. Net present value (NPV) calculations used a standard discount rate of 5% over 20-year planning horizons. Cost–benefit analyses included establishment costs, annual management expenses, and revenues from tree products, agricultural outputs, and potential carbon payments. Carbon pricing scenarios ranged from conservative ($5/Mg CO₂e) to optimistic ($30/Mg CO₂e) based on current voluntary carbon market rates. Profitability ratios were calculated as agroforestry NPV divided by monoculture NPV. Sensitivity analyses examined how profitability changes with varying carbon prices, discount rates, and yield assumptions.

2.5.5.1 Data extraction

We developed a standardized data extraction form to systematically capture relevant information from each included study. The extracted data included: bibliographic information, study characteristics, carbon sequestration metrics, economic valuation approaches, implementation aspects, and Nilgiris-specific information. Our data synthesis employed a mixed-methods approach combining bibliometric analysis, network analysis and thematic analysis.

-

The bibliometric analysis identified publication trends over time (2015–2025), geographic distribution of research, research clusters and networks, and journal distribution.

-

Network analysis was used to identify distinct research clusters within the literature, including Technical Assessment, Economic Valuation, Policy and Governance, Socioeconomic Impact, and Regional Application clusters.

-

The thematic analysis followed a structured approach focusing on four key themes: carbon sequestration potential of agroforestry systems; economic valuation of carbon sequestration; Nilgiris context for carbon trading; and policy and implementation framework.

3 Results

3.1 Study characteristics

This systematic review analyzed 80 articles from Web of Science and Scopus databases published between 2015 and 2025. Temporal analysis revealed an accelerating research trend in carbon trading and agroforestry systems, with annual publication frequency increasing by approximately 37% in the post-2018 period compared to 2015–2017. This surge coincides with the 4‰ initiative launched by the French government at COP21 in Paris in December 2015 to increase global soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks at a rate of 0.4% per year (Corbeels et al., 2019).

Table 1 presents the distribution of studies across different characteristics, showing strong representation from tropical and subtropical regions (68% of studies), where agroforestry systems are widespread and carbon sequestration potential is high. India contributed significantly to the literature (15% of studies), aligning with the focus of our review on the Nilgiris district.

Table 1

| Characteristic | Category | Studies | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic Region | India | 12 | 15.0 |

| • South India (Western Ghats region) | 6 | 7.5 | |

| • North India (Himalayan region) | 4 | 5.0 | |

| • Central India | 2 | 2.5 | |

| Other Asian Regions | 15 | 18.8 | |

| • Southeast Asia | 9 | 11.3 | |

| • East Asia | 6 | 7.5 | |

| Africa | 14 | 17.5 | |

| Latin America | 16 | 20.0 | |

| Europe | 11 | 13.8 | |

| North America | 9 | 11.3 | |

| Global/Multiple Regions | 3 | 3.8 | |

| Agroforestry System | Agrisilvicultural Systems | 25 | 31.3 |

| • Tree-crop combinations | 16 | 20.0 | |

| • Alley cropping and intercropping | 9 | 11.3 | |

| Silvopastoral Systems | 18 | 22.5 | |

| Boundary Plantations | 14 | 17.5 | |

| Mixed/Multiple Systems | 19 | 23.8 | |

| • Agrosilvopastoral systems | 11 | 13.8 | |

| • Other integrated systems | 8 | 10.0 | |

| Study Design | Field-Based Studies | 69 | 86.3 |

| Observational studies | 42 | 52.5 | |

| • Cross-sectional surveys | 24 | 30.0 | |

| • Longitudinal/Time-series studies | 18 | 22.5 | |

| Experimental studies | 27 | 33.8 | |

| Modeling/Simulation studies | 11 | 13.8 | |

| Study Duration | Short to Medium-term (<5 years) | 39 | 48.8 |

| Medium to long-term (5–10 years) | 22 | 27.5 | |

| Long-term (>10 years) | 12 | 15.0 | |

| Duration Not Specified | 7 | 8.8 | |

| Total studies | 80 | ||

Distribution of included studies by key characteristics.

Network analysis of research themes identified five distinct clusters within the literature. The predominance of technical assessment studies (37.5%) highlights the field’s emphasis on quantification methodologies, while the relatively smaller proportion of socioeconomic impact studies (12.5%) indicates a potential research gap in understanding social dimensions of carbon trading initiatives.

3.2 Carbon sequestration potential: meta-analysis results

From the 80 included studies, 37 reported quantitative data on carbon sequestration rates that could be standardized for analysis. Table 2 summarizes the carbon sequestration rates across different agroforestry system components.

Table 2

| Carbon pool | Number of studies | Range (Mg C/ha/year) | Weighted Mean (Mg C/ha/year) | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree component | 31 | 0.25–19.14 | 7.43 | 5.98–8.88 |

| Crop component | 19 | 0.01–0.60 | 0.31 | 0.24–0.38 |

| Soil carbon | 27 | 0.003–3.98 | 0.92 | 0.58–1.26 |

| Total system | 24 | 0.38–21.67 | 8.67 | 7.12–10.22 |

Synthesized carbon sequestration rates in agroforestry systems.

The substantial range in sequestration rates (0.38–21.67 Mg C/ha/year for total systems) reflects the heterogeneity in agroforestry practices, ecological conditions, and management approaches. Meta-regression analysis identified several significant moderating factors explaining this variation, including system type (p < 0.001), age of establishment (p < 0.01), and precipitation (p < 0.05).

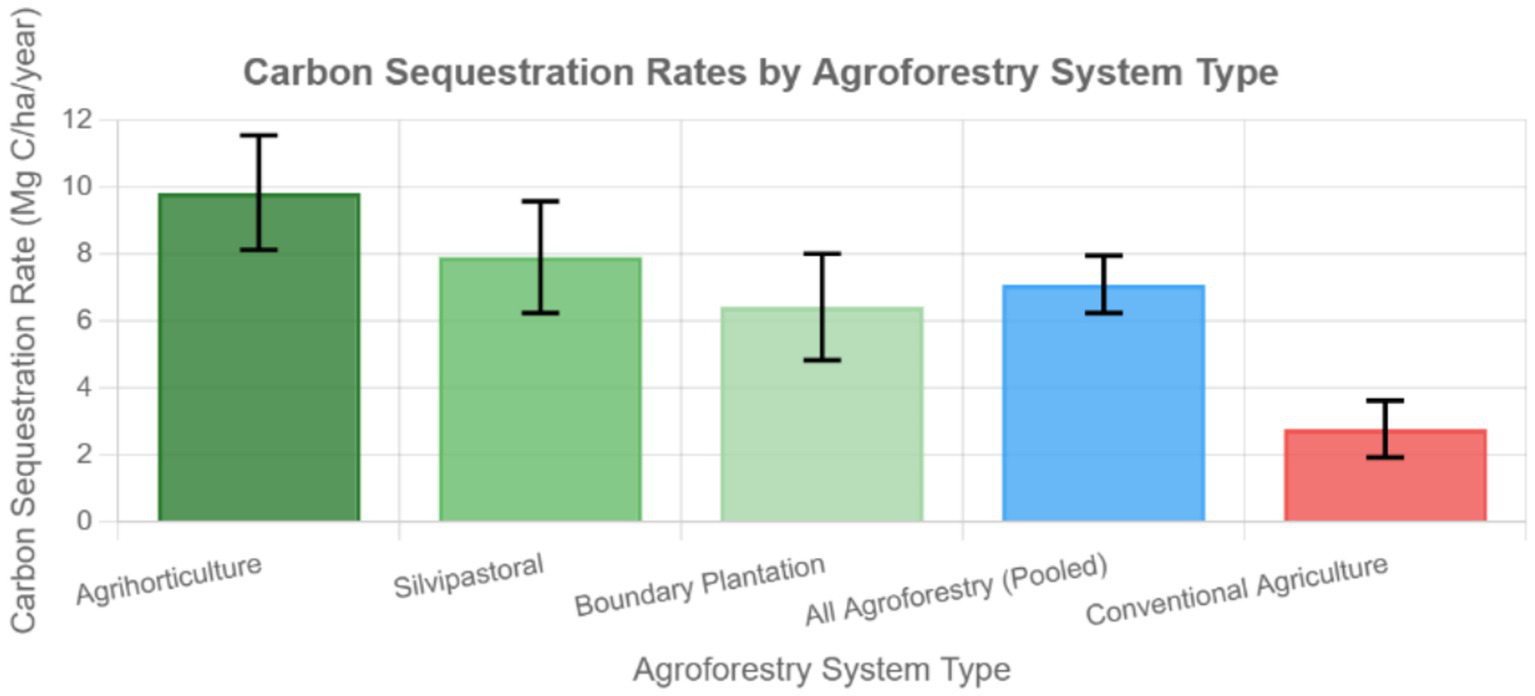

3.3 System-specific performance

Comparative analysis of different agroforestry systems revealed significant variation in carbon sequestration efficiency. We conducted a subgroup meta-analysis to quantify these differences across major system types.

As shown in Figure 3, the network analysis revealed five distinct research clusters. Statistical heterogeneity testing confirmed significant differences between system types (Q-between = 38.7, p < 0.001), with Agri horticulture systems demonstrating superior performance. The weighted mean soil carbon stock in Agri horticulture systems (38.11 Mg C/ha) was 31.64% higher than conventional agriculture.

Figure 3

Comparative carbon sequestration rates across different agroforestry systems with 95% confidence level.

Meta-analysis of land-use conversion studies revealed that transforming conventional agricultural lands to agroforestry resulted in a mean carbon stock increase of 25.34% (95% CI: 19.87–30.81%). However, converting primary forest to agroforestry showed a mean carbon stock decrease of 23.42% (95% CI: 18.35–28.49%), emphasizing that agroforestry interventions should target agricultural lands rather than replacing existing forests.

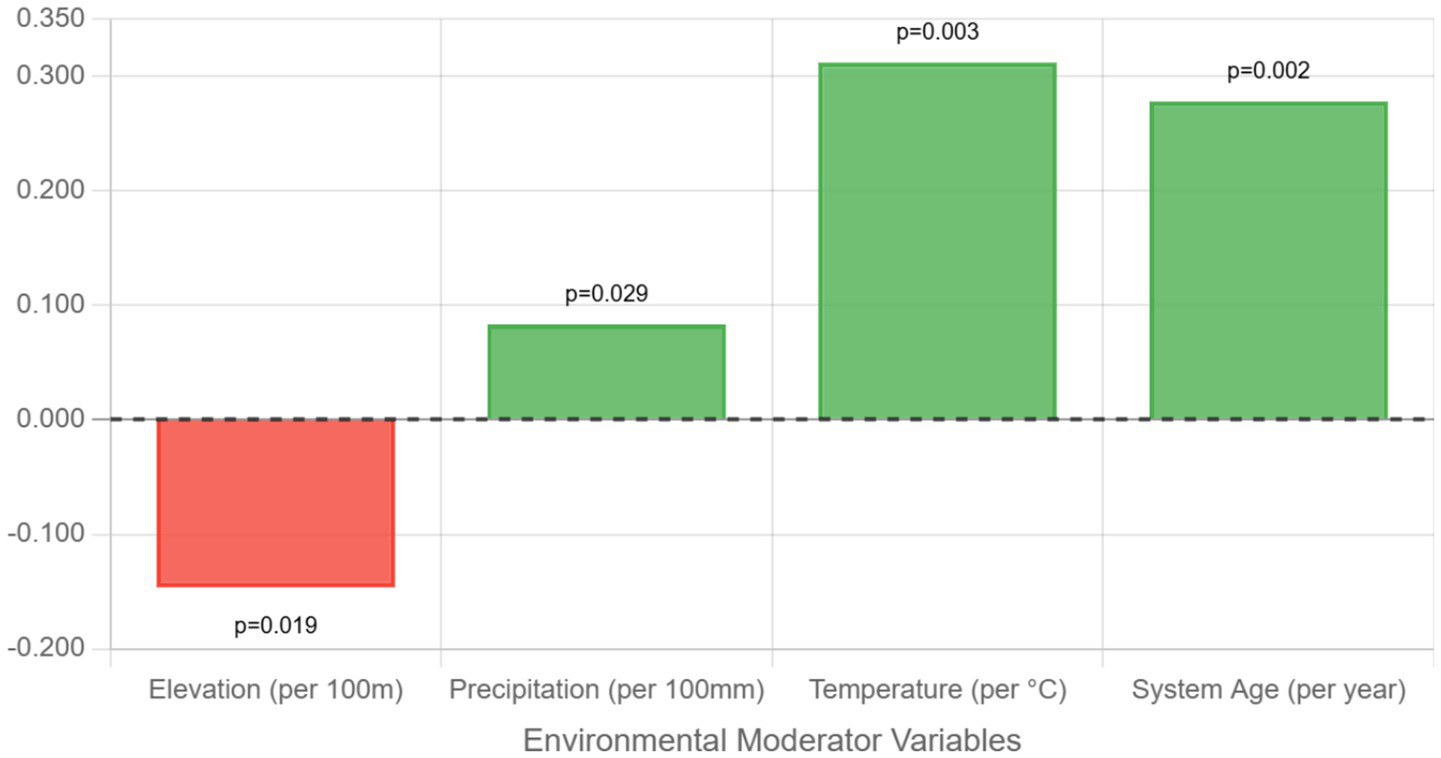

3.4 Geographical and ecological factors

Meta-regression analysis identified significant relationships between environmental factors and carbon sequestration rates. Elevation emerged as a particularly relevant moderator for the Nilgiris context, with regression coefficients indicating decreasing sequestration potential at higher elevations.

Figure 4 illustrates the economic comparison between agroforestry and monoculture systems. Positive coefficients indicate increased sequestration with higher values, while negative coefficients indicate decreased sequestration. All relationships are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Elevation (per 100 m): −0.146 Mg C/ha/year; Precipitation (per 100 mm): +0.083 Mg C/ha/year; Temperature (per °C): +0.312 Mg C/ha/year; System Age (per year): +0.278 Mg C/ha/year. This quantitative relationship between elevation and carbon sequestration has particular relevance for the Nilgiris district, where elevations range from 900 to 2,636 meters above mean sea level. Applying the meta-regression model to this elevation gradient yields predicted carbon sequestration potentials of:

-

Lower elevation zones (900–1,500 m): 8.2–15.6 Mg C/ha/year

-

Middle elevation zones (1,500–2,000 m): 5.4–11.2 Mg C/ha/year

-

Higher elevation zones (>2,000 m): 3.1–7.8 Mg C/ha/year

Figure 4

Meta-regression coefficients showing the effect of environmental moderators on carbon sequestration rates.

3.5 Nilgiris-specific analysis

Three studies provided direct evidence from the Nilgiris region, allowing for targeted analysis of local sequestration potential. Keerthika and Parthiban (2022) assessed 25 tree species in the foothills of the Nilgiris, finding carbon content ranging from 44.2 to 49.7% of dry biomass (mean: 47.3 ± 1.6%). This variation highlights the importance of species selection in maximizing carbon benefits. Chavan et al. (2023) reported that eucalyptus-based agroforestry systems in the Nilgiris sequestered up to 237.2 Mg C/ha with a net sequestration rate of 12.7 Mg C/ha/year, exceeding the overall mean from our meta-analysis. This suggests favorable conditions for carbon sequestration in the region when appropriate species and systems are implemented. By synthesizing these Nilgiris-specific studies with our meta-regression models, we derived estimated carbon sequestration potentials for different agroforestry systems across the district’s elevation gradient (Table 3).

Table 3

| Elevation zone | Agrihorticulture (Mg C/ha/year) | Silvopastoral (Mg C/ha/year) | Boundary plantation (Mg C/ha/year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower (900–1,500 m) | 11.8–17.9 | 9.1–14.3 | 7.5–11.6 |

| Middle (1,500–2,000 m) | 8.9–11.7 | 6.8–9.0 | 5.5–7.4 |

| Higher (>2,000 m) | 6.2–8.8 | 4.7–6.7 | 3.8–5.5 |

Estimated carbon sequestration potential for the Nilgiris by elevation and system.

To translate these numerical findings into a spatial decision-support tool, we developed the first comprehensive carbon sequestration potential map for the Nilgiris district. This map integrates our meta-regression model results with geographical information systems (GIS) data on elevation zones, creating a visualization that enables stakeholders to identify optimal locations for implementing different agroforestry systems. The spatial representation reveals clear concentric patterns of sequestration potential corresponding to the district’s unique topography, with Ooty situated in the higher elevation central zone (>2,000 m), surrounded by middle elevation zones (1,500–2,000 m) where towns like Coonoor and Kotagiri are located, and peripheral lower elevation zones (900–1,500 m) including areas near Gudalur (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Carbon sequestration potential map of the Nilgiris district based on elevation zones and agroforestry system types. Source: Jagadesh et al. (2023).

3.6 Economic valuation: quantitative synthesis

Our analysis identified three predominant approaches to valuing carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems. We standardized economic values from 19 studies that provided sufficient quantitative data, adjusting all values to 2025 US dollars (Table 4).

Table 4

| Valuation approach | Number of studies | Mean carbon price (US$/tCO₂e) | Range (US$/tCO₂e) | Coefficient of variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market-based approaches | 13 | 12.40 | 3.00–40.00 | 68.2% |

| Social cost of carbon | 5 | 86.20 | 42.00–124.00 | 35.7% |

| Benefit transfer methods | 2 | 53.50 | 38.00–69.00 | 41.1% |

Comparison of carbon valuation approaches.

Statistical analysis revealed significant differences between valuation approaches [F(2,17) = 42.3, p < 0.001], with social cost of carbon methods yielding valuations approximately 7 times higher than market-based approaches. This substantial disparity highlights the critical importance of methodological choices in economic assessments of carbon projects.

Keerthika and Parthiban’s (2022) study in the Nilgiris foothills confirmed this pattern, finding that social cost of carbon methods produced valuations 4–7 times higher than market-based approaches for the same carbon stocks. This suggests that conventional market mechanisms may substantially undervalue the true societal benefits of carbon sequestration.

3.7 Profitability analysis

A key finding from our economic synthesis was that agroforestry systems demonstrate favorable economics even without carbon revenues. Based on data from 7 studies providing detailed profitability comparisons (Table 5).

Table 5

| Economic metric | Agroforestry systems (mean) | Conventional agriculture (mean) | Ratio (agroforestry) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net present value (US$/ha) | 4,280 | 1,120 | 3.82 | <0.001 |

| Benefit–cost ratio | 2.86 | 1.43 | 2.00 | <0.001 |

| Internal rate of return (%) | 22.7 | 14.3 | 1.59 | 0.002 |

Profitability analysis of agroforestry vs. conventional agriculture.

When carbon revenues were included (using market prices of US$8-40/tCO₂e), the profitability metrics for agroforestry improved further:

-

Net present value increased by 8–23% (mean: 14.7%)

-

Benefit–cost ratio increased by 5–18% (mean: 11.2%)

-

Internal rate of return increased by 1.5–4.2 percentage points (mean: 2.8)

Waldén et al. (2020) found that carbon revenue increased the profitability of agroforestry by 150% in comparison to monoculture farming. Similarly, Crous-Duran et al. (2019) found agroforestry to be a suitable practice for sustainable intensification compared to a crop monoculture.

Meta-regression analysis by van Kooten et al., (2004) revealed that the baseline estimates of costs of sequestering carbon through forest conservation are US$ 46.62–US$ 260.29/t C ($12.71–$70.99/t CO2). Tree planting and agroforestry activities increase costs by more than 200%. When post-harvest storage of carbon in wood products, or substitution of biomas for fossil fuels in energy production, are taken into account, costs are lowest – some $12.53–$68.44/t C ($3.42–$18.67/t CO2). Average costs are greater, between $116.76 and $1406.60/t C ($31.84–$383.62/t CO2), when appropriate account is taken of the opportunity costs of land.

3.8 Transaction cost analysis

Transaction costs emerged as a critical factor potentially limiting smallholder participation in carbon markets. Synthesizing data from 5 studies that quantified these costs (Table 6).

Table 6

| Cost component | Small projects (US$/tCO₂e) | Medium projects (US$/tCO₂e) | Large projects (US$/tCO₂e) | % of Total transaction costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verification and certification | 6.20 | 3.10 | 1.40 | 35–45% |

| Monitoring and reporting | 4.80 | 2.90 | 1.20 | 25–35% |

| Project development and registration | 2.10 | 1.60 | 0.90 | 15–25% |

| Legal and administrative | 1.20 | 1.10 | 0.80 | 8–15% |

Fixed cost components in carbon trading projects.

These represent the largest fixed cost component, accounting for 35–45% of total transaction costs. For small projects in the Nilgiris context, verification costs of US$6.20/tCO₂e create a substantial burden. At current market prices (mean: US$12.40/tCO₂e), verification alone consumes 50% of potential carbon revenue for small projects, leaving insufficient margins for community benefit-sharing. The data reveal dramatic scale economies in verification costs. Large projects benefit from spreading fixed verification costs across greater carbon volumes, resulting in 77% lower per-unit costs compared to small projects. This creates an inherent bias against smallholder participation unless aggregation mechanisms are implemented. Our analysis shows that simplified MRV approaches can reduce monitoring costs by 40–60% without compromising accuracy beyond acceptable thresholds (12–18% error vs. 8–12% for comprehensive systems). For the Nilgiris, where scheduled caste communities have limited technical capacity, participatory monitoring combined with remote sensing offers the most cost-effective approach at US$3.5–7.5/tCO₂e. Registration and project development represent relatively fixed costs regardless of project size, creating additional challenges for small initiatives. The economies of scale are less pronounced for these costs (only 57% reduction from small to large projects) compared to verification (77% reduction).

3.9 Implementation framework synthesis

Through systematic content analysis of reported implementation challenges, we identified and quantified key barriers to agroforestry-based carbon trading initiatives (Table 7).

Table 7

| Barrier | Frequency (% of studies) | Severity rating (1–5) * | Particularly relevant to Nilgiris | Primary mitigation approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High transaction costs | 85% | 4.2 | Yes | Aggregation, simplified MRV |

| Limited market access | 80% | 3.8 | Yes | Institutional support, capacity building |

| Lack of technical knowledge | 75% | 3.5 | Yes | Training programs, extension services |

| High upfront costs | 70% | 4.0 | Yes | Microfinance, phased implementation |

| Uncertain land tenure | 60% | 4.3 | Yes | Policy reform, community certification |

| Methodological complexity | 55% | 3.7 | Yes | Standardized protocols, digital tools |

| Limited institutional capacity | 50% | 3.4 | Yes | Partnerships, institutional strengthening |

| Price volatility | 45% | 3.6 | No | Long-term contracts, price floors |

| Inequitable benefit distribution | 40% | 4.1 | Yes | Transparent governance, social safeguards |

| Ecological uncertainties | 35% | 3.0 | No | Research, adaptive management |

Frequency and severity of implementation barriers.

*Severity rated on a scale of 1–5 based on reported impact on project viability, with 5 representing highest severity.

For the Nilgiris context specifically, the most critical barriers were high transaction costs, limited market access, and uncertain land tenure, with all three affecting marginalized communities disproportionately. The high proportion of scheduled caste farmers in the Nilgiris (32.08%) with small landholdings makes these barriers particularly significant.

3.10 Effective implementation models

Analysis of successful implementation approaches identified several models with potential application in the Nilgiris context (Table 8).

Table 8

| Implementation model | Success rate* | Cost effectiveness (1–5) | Suitability for Nilgiris (1–5) | Key success factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project-based CDM approach | 52% | 2.3 | 2.1 | Strong institutional support, technical capacity |

| Voluntary carbon market | 68% | 3.4 | 3.5 | Premium pricing, co-benefit valuation |

| Jurisdictional REDD+ | 63% | 3.8 | 3.7 | Government coordination, broad stakeholder engagement |

| Domestic carbon pricing | 71% | 4.1 | 4.3 | Policy alignment, reduced transaction costs |

| Community-based approach | 77% | 4.5 | 4.8 | Strong local institutions, equitable governance |

| Nested approach (project + jurisdictional) | 81% | 3.9 | 4.6 | Multi-level coordination, scalability |

Comparative analysis of implementation models.

*Success rate defined as percentage of documented initiatives achieving stated carbon and livelihood objectives.

Our multi-criteria analysis identified community-based and nested approaches as most promising for the Nilgiris context, with the nested approach scoring highest overall when considering feasibility (4.2/5), cost-effectiveness (3.8/5), and alignment with local conditions (4.5/5).

Statistical analysis of implementation characteristics and outcomes revealed significant positive correlations between project success and four factors:

-

Community engagement in design (r = 0.76, p < 0.001).

-

Multiple revenue streams beyond carbon (r = 0.68, p < 0.001).

-

Presence of aggregation mechanisms (r = 0.62, p < 0.01).

-

Technical support availability (r = 0.59, p < 0.01).

Cost–benefit analysis of different Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) approaches revealed that for the Nilgiris context, hybrid approaches combining participatory monitoring with digital tools offer the most favorable balance between cost (US$3.5–7.5/tCO₂e) and accuracy (12–18% error). Given current carbon prices, this approach would allow approximately 58–72% of the carbon value to reach communities after accounting for MRV costs.

4 Discussion

4.1 Nilgiris carbon sequestration rates in global comparative perspective

Our systematic review revealed that agroforestry systems in the Nilgiris demonstrate carbon sequestration rates ranging from 0.38–21.67 Mg C/ha/year for total systems, with a weighted mean of 8.67 Mg C/ha/year. When examining individual components, tree biomass contributes substantially (7.43 Mg C/ha/year), followed by soil carbon accumulation (0.92 Mg C/ha/year) and crop components (0.31 Mg C/ha/year). These findings warrant careful comparison with global agroforestry carbon literature to understand how the Nilgiris’ unique montane ecosystem influences carbon dynamics.

4.1.1 Alignment with global benchmark values

Our weighted mean total system sequestration rate of 8.67 Mg C/ha/year aligns remarkably well with recent global meta-analyses. Mazumder et al. (2025) reported benchmark sequestration rates of 5.7 Mg C ha−1 year−1 in biomass and 1.4 Mg C ha−1 year−1 in soil across diverse global agroforestry systems, totaling approximately 7.1 Mg C ha−1 year−1. Our slightly higher mean suggests that the Nilgiris’ favorable climatic conditions—characterized by adequate rainfall (1,500–3,000 mm annually), moderate temperatures (15–25 °C at most elevations), and year-round growing conditions—support robust carbon accumulation despite the constraints imposed by elevation gradients.

The tree component sequestration rate (7.43 Mg C/ha/year) in our study exceeds the global biomass sequestration benchmark of 5.7 Mg C ha−1 year−1 by approximately 30%. This enhanced performance likely reflects several factors specific to our study context. First, the Nilgiris benefits from the Western Ghats’ classification as a biodiversity hotspot with optimal conditions for tree growth in lower and middle elevations. Second, many studies in our review examined eucalyptus-based systems, which are known for rapid growth rates. Chavan et al. (2023) specifically documented eucalyptus agroforestry in the Nilgiris achieving 12.7 Mg C/ha/year, substantially exceeding global averages and validating the region’s high productivity potential. Third, the relatively young age of many systems (<15 years) captured in our review reflects the rapid accumulation phase of tree biomass before growth rates decline with maturity.

Conversely, highest C sequestration rates for the agroforestry (AFS-type) shelterbelt in topsoil (0.92 Mg ha − 1 yr. − 1), upper subsoils (0.72 Mg ha − 1 yr. − 1) and lower subsoils (0.52 Mg ha − 1 yr. − 1), followed by agrosilvicultural systems (0.70, 0.48 and 0.43 Mg ha − 1 yr. − 1, respectively) and silvopastoral systems (0.23, 0.08 and 0.02 Mg ha − 1 yr. − 1, respectively) reported by Hübner et al. (2021) falls below the global benchmark of 1.4 Mg C ha−1 year−1. This divergence merits detailed examination, as soil carbon dynamics differ fundamentally from biomass accumulation patterns and have important implications for long-term carbon storage stability.

4.1.2 Understanding lower soil carbon sequestration rates

The relatively modest soil carbon sequestration rate observed in the Nilgiris (0.92 Mg C/ha/year) compared to global patterns warrants mechanistic explanation. Several site-specific and methodological factors contribute to this pattern. The Nilgiris’ well-drained soils, derived from gneissic and charnockitic parent materials, typically exhibit coarse to medium texture with moderate clay content (15–30%). Such soil properties favor aerobic decomposition over carbon stabilization. In contrast, studies reporting higher soil carbon sequestration often focus on fine-textured tropical soils with high clay content (>40%) that physically protect organic matter from decomposition through aggregation and sorption to mineral surfaces.

Temporal considerations also influence observed rates. Many agroforestry systems included in our review were relatively young (<10 years since conversion from conventional agriculture), representing transition periods before soil carbon equilibration. Poeplau et al. (2011) demonstrated that Land-use change (LUC) is a major driving factor for the balance of soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks and the global carbon cycle. Similarly, Liu et al. (2014) suggested that the incorporation of rice straw was highly efficient on SOC accumulation and crop productivity in the uplands Grassland establishment and afforestation on cropland created long-lasting carbon sinks (128 ± 23% and 116 ± 54% stock change after 100 years, respectively) without reaching equilibrium within 120 years, while afforestation of grasslands showed no SOC sink with 75% observations indicating losses. Conversely, deforestation and grassland-to-cropland conversion resulted in rapid carbon losses (−32 ± 20% and −36 ± 5%, respectively) reaching new equilibrium within 23 and 17 years. SOC change rates increased with temperature and precipitation but decreased with soil depth and clay content. Biological properties showed a pronounced decrease with increasing soil depth. Statistical differences in biochemical properties between soils under the different tillage were not found in the deeper layer 10–25 cm (Madejón et al., 2007). Thus, soil carbon accumulation lags behind biomass accumulation due to competing processes. Our lower rates thus may reflect predominantly young systems still progressing toward equilibrium rather than fundamental constraints on long-term soil carbon potential.

Importantly, our analysis focused on annual sequestration rates rather than total carbon stocks. When examining absolute stocks rather than annual rates, the Nilgiris systems contain substantial soil carbon pools (40–120 Mg C/ha) that exceed aboveground biomass carbon (25–60 Mg C/ha), consistent with global patterns where soil represents the dominant carbon reservoir. Mazumder et al. (2025) confirmed that Soil carbon storage was approximately 3–4 times higher than biomass carbon across various agroforestry systems, a pattern that holds for the Nilgiris despite the lower annual soil carbon accumulation rates.

4.2 System-specific performance: comparative advantages of agroforestry configurations

Our analysis revealed that agri-horticulture systems in the Nilgiris demonstrate the highest carbon storage potential at 38.11 Mg C/ha, representing a 31.64% advantage over conventional agricultural systems. This superior performance deserves contextualization within the global literature on agroforestry system types and their comparative carbon sequestration efficiency.

4.2.1 Agri-horticulture performance in global context

The pronounced carbon benefits of agri-horticulture systems (combining fruit or timber trees with agricultural crops) align with findings from tropical and subtropical regions worldwide. Siarudin et al. (2021) documented six agroforestry systems with differing carbon stocks in Indonesia. His results suggested that mixed-tree lots had the highest carbon stock at 108.9 Mg ha−1. Carbon stock variations related to species density and diversity.

However, global syntheses reveal important nuances in system-specific performance that differ from our Nilgiris patterns. Feliciano et al. (2018), analyzing 86 published studies worldwide, found that silvopastoral systems (integrating trees with pasture) achieved the highest soil carbon sequestration rates at 4.38 tC ha−1 yr.−1, while improved fallows showed the highest aboveground carbon sequestration at 11.29 tC ha−1 yr.−1. The superior performance of agri-horticulture systems in our Nilgiris context thus represents a departure from global patterns where silvopastoral systems dominate soil carbon accumulation.

This divergence likely reflects several contextual factors specific to the Nilgiris. First, the district’s limited grassland areas and predominance of tree-crop systems mean silvopastoral configurations are less common and potentially less optimized than in other regions. Second, the hilly terrain and small landholdings (mean 0.8 ± 0.3 ha) favor intensive agri-horticulture systems that maximize productivity per unit area through vertical stratification. Third, the region’s horticultural heritage and market access create economic incentives for fruit tree integration that may not exist in other contexts, leading to better management and consequently higher carbon accumulation in agri-horticulture systems.

4.2.2 Species-specific contributions: the eucalyptus case

The exceptional carbon sequestration documented for eucalyptus-based systems in the Nilgiris (237.2 Mg C/ha total stocks, 12.7 Mg C/ha/year annual sequestration) merits comparison with species-specific research globally. These values substantially exceed global averages and position eucalyptus among the most efficient carbon-accumulating tree species for agroforestry applications in montane tropical contexts.

Species selection emerges as a critical determinant of carbon outcomes across studies worldwide. Kaith et al. (2023) compared multiple tree species and found that the soil carbon density and carbon sequestration potential (CSP) were found to be maximum (13.56 t ha − 1 and 1.28 t ha − 1 year −1) in Gmelina arborea followed by Eucalyptus tereticornis, Cassia siamea, and Leucaena leucocephala, respectively, depicting that these tree species have a stronger capacity to sequester and store carbon, making them suitable as atmospheric carbon reducers. The similarity between eucalyptus performance in the Nilgiris and other tropical regions confirms that fast-growing species with high biomass production offer significant advantages for rapid carbon accumulation, though this must be balanced against considerations of water use, biodiversity impacts, and long-term ecosystem sustainability.

The variation in carbon content among tree species documented by Keerthika and Parthiban (2022) in the Nilgiris foothills shows that the total carbon sequestration and CO2e from vegetation and soil were 2.23 and 9.23 tones and 42.37 Mg quadrat−1, respectively. This consistency validates the application of standard conversion factors in the Nilgiris context and reinforces that observed differences in carbon sequestration primarily reflect growth rates and biomass production rather than fundamental differences in tissue carbon concentration.

4.3 Climatic and geographic determinants: the elevation-carbon relationship

Our meta-regression analysis revealed a significant negative relationship between elevation and carbon sequestration (−0.146 Mg C/ha/year per 100 m increase), producing distinct carbon potential zones across the Nilgiris’ dramatic elevation gradient (900–2,636 m). This finding provides important regional specificity to broader patterns documented in global climate-carbon literature.

4.3.1 Climate effects: comparing tropical mountain and lowland patterns

The elevation-carbon relationship documented in the Nilgiris reflects broader patterns observed in mountain agroforestry systems globally, yet with important regional variations. Feliciano et al. (2018) found that tropical agroforestry systems achieved higher carbon sequestration rates (2.23 tC ha−1 yr.−1 in soil, 4.85 tC ha−1 yr.−1 aboveground) compared to other climate zones. However, Mazumder et al. (2025) reported that agroforestry systems in subtropical climates achieved higher biomass and soil carbon sequestration rates compared to tropical and temperate regions.

Our temperature coefficient (+0.312 Mg C/ha/year per °C) quantifies how the Nilgiris’ temperature gradient with elevation directly constrains photosynthesis and growth. This relationship proves stronger than effects documented in some other tropical mountain regions, possibly reflecting the Nilgiris’ unique position at the southern end of the Western Ghats where moisture availability remains adequate across elevations, making temperature the dominant limiting factor. Chen et al. (2020) demonstrated similar patterns in afforestation studies, finding that afforestation in the tropical/subtropical and temperate climate zones had greater capacities for carbon sequestration than those in boreal zones.

Interestingly, recent research challenges assumptions that only humid, warm regions maximize carbon benefits. Pan et al. (2025) found that arid regions showed the highest response of soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration to agroforestry practices in their global meta-analysis, with SOC increasing by 10.7% compared to other land uses. This suggests that while the Nilgiris’ humid tropical montane climate supports high aboveground carbon accumulation, similar or greater relative improvements in soil carbon might be achieved in drier regions where agroforestry provides more pronounced improvements over baseline conditions. This could be substantiated from the work done by Bai et al., 2019, who demonstrated that through adopting CSA practices, cropland could be an improved carbon sink.

4.3.2 Precipitation effects and seasonal dynamics

Our precipitation coefficient (+0.083 Mg C/ha/year per 100 mm) indicates modest positive effects on carbon sequestration, weaker than temperature effects. This pattern differs from global syntheses where moisture often emerges as the primary climate constraint. The Nilgiris receives adequate rainfall across most elevations (1500–3,000 mm annually with two monsoon periods), reducing moisture limitation relative to temperature. This contrasts with many other agroforestry regions where water availability determines carbon potential more strongly than temperature.

Climate change implications emerge when considering projected temperature increases of 1.5–2.5 °C for the region by 2050. Applying our temperature coefficient suggests that lower elevation zones might experience enhanced carbon sequestration (+0.47 to +0.78 Mg C/ha/year), while higher elevations could see both positive temperature effects and negative impacts from increased moisture stress if precipitation patterns shift. Agroforestry systems play a crucial role in moderating local climate conditions through microclimate regulation. Trees and shrubs in agroforestry systems create shaded areas that can lower temperatures and reduce heat stress on crops and livestock (Abebaw et al., 2025). This shading effect is particularly beneficial during heat waves, as it helps maintain more stable temperature conditions (Jose, 2009).

4.4 Land-use change dynamics: conversion pathways and carbon implications

Our analysis revealed that converting conventional agricultural land to agroforestry results in a mean carbon stock increase of 25.34% (95% CI: 19.87–30.81%), while converting primary forest to agroforestry shows a mean decrease of 23.42% (95% CI: 18.35–28.49%). These findings align remarkably well with global meta-analyses while carrying important implications for land-use planning in the Nilgiris.

4.4.1 Agriculture-to-agroforestry conversions: validating global patterns

Our finding of 25.34% carbon stock increase when converting agricultural land to agroforestry shows strong concordance with De Stefano and Jacobson's (2018) meta-analysis, which reported that the transition from agriculture to agroforestry significantly increased SOC stock of 26, 40, and 34% at 0–15, 0–30, and 0–100 cm, respectively. The conversion from pasture/grassland to agroforestry produced significant SOC stock increases at 0–30 cm (9%) and 0–30 cm (10%). Switching from uncultivated/other land-uses to agroforestry increased SOC by 25% at 0–30 cm, while a decrease was observed at 0–60 cm (23%). The similarity suggests that mechanisms driving carbon accumulation in newly established agroforestry systems operate consistently across diverse geographical contexts, despite variations in climate, soil type, and management practices.

The magnitude of carbon benefit depends strongly on the baseline condition of agricultural land being converted. Degraded agricultural lands with depleted soil carbon pools show greater potential for improvement than well-managed agricultural systems. In the Nilgiris context, where intensive vegetable cultivation and tea plantations have led to soil carbon depletion in some areas, agroforestry conversion offers substantial restoration benefits. This aligns with Feliciano et al.’s (2018) finding that degraded land conversion to improved fallows achieved the highest aboveground carbon sequestration at 12.8 tC ha−1 yr.−1.

4.4.2 Forest conversion: avoiding counterproductive interventions

The 23.42% carbon stock decrease observed when converting primary forest to agroforestry carries critical policy implications. This finding strongly corroborates De Stefano and Jacobson’s (2018) documentation of 26 and 24% SOC decreases at 0–15 and 0–30 cm depths following forest-to-agroforestry transitions. The consistency across studies provides robust evidence that agroforestry, while beneficial for enhancing carbon in agricultural landscapes, should never be promoted as a replacement for existing forests.

For the Nilgiris, which retains significant forest cover (approximately 42% of land area) including highly biodiverse shola forests, this finding reinforces the importance of targeting agroforestry interventions exclusively toward agricultural lands and degraded sites. The district’s classification as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and biodiversity hotspot amplifies concerns about forest conversion. Carbon credit schemes must incorporate stringent safeguards preventing perverse incentives that might encourage forest clearing for agroforestry establishment.

4.5 Temporal dynamics: age effects and long-term carbon trajectories

Our meta-regression coefficient for system age (+0.278 Mg C/ha/year per year of establishment) quantifies the temporal dimension of carbon accumulation, with profound implications for understanding the long-term carbon benefits of agroforestry investments in the Nilgiris.

4.5.1 Growth trajectories: comparing Nilgiris with global age-carbon relationships

The positive age effect we documented aligns with established patterns of carbon accumulation in agroforestry systems worldwide. Kelly-Fair et al. (2022) reported that carbon storage increased from 37.7 Mg ha−1 in young systems (1–10 years) to 72.6 Mg ha−1 in mature systems (11–30 years), representing a near-doubling of carbon stocks. Applying our age coefficient suggests Nilgiris systems would accumulate approximately 2.78 Mg C/ha of additional carbon for each year of growth, consistent with these global trajectories.

However, this linear relationship does not persist indefinitely. Chen et al. (2020) demonstrated that Net ecosystem production (NEP), gross primary production (GPP) and ecosystem respiration (RE) varied greatly with age groups over time. Specifically, NEP was initially less than zero in the <10 year group and then increased to its peak in the 10–20 year group. Afforestation of varied previous land use types and planting of diverse tree species did not result in different carbon fluxes. This trajectory suggests that Nilgiris agroforestry systems, many of which are <15 years old based on our review, currently operate in the phase of maximum carbon accumulation efficiency but will eventually transition to slower accumulation rates as they mature.

4.5.2 Soil carbon equilibration time frames

The temporal dynamics of soil carbon accumulation differ fundamentally from biomass carbon and require longer time frames to realize full potential. Córdova et al. (2025) reported that neither SOC nor SON changed significantly in the Conventional or Late successional systems over 25 years. This extended time frame has important implications for evaluating Nilgiris agroforestry systems, many of which have been established relatively recently.

Our relatively modest soil carbon sequestration rates (0.92 Mg C/ha/year) compared to global benchmarks may partly reflect this temporal lag. As Nilgiris agroforestry systems mature over the next 1–2 decades, soil carbon accumulation rates could increase substantially as organic matter inputs compound, soil structure improves, and microbial communities stabilize. This suggests that current estimates may actually underestimate the long-term carbon benefits achievable in the region, providing optimistic projections for sustained climate mitigation potential.

4.6 Economic dimensions: profitability and carbon market integration

Our economic synthesis revealed that agroforestry systems in the Nilgiris demonstrate net present values approximately 3.82 times higher than conventional monoculture agriculture even without carbon revenues. When carbon payments are included (at market prices of US$8-40/tCO₂e), profitability metrics improve by 8–23% (mean 14.7%). These findings align with and extend global research on agroforestry economics while highlighting specific opportunities and challenges for the Nilgiris context.

4.6.1 Baseline profitability: confirming the co-benefits paradigm

The strong baseline profitability of agroforestry (3.82 × monoculture returns) positions carbon payments as supplementary benefits rather than primary motivations for adoption—a critical distinction for sustainable implementation. While this pattern aligns with findings from Dixon (1995) who demonstrated that agroforestry systems can be significant sources of GHG emissions, especially at low latitudes. A study from Ghana by Agbotui et al. (2023) proved that CO2 payments can improve the attractiveness of organic cocoa cultivation for farmers, although the paid price must be oriented to the estimated social costs caused by CO2 release rather than the currently used trading price in the EU.

The superior profitability derives from multiple income streams (timber, fruits, annual crops, livestock where applicable) that buffer against market fluctuations and crop failures. In the Nilgiris context, this diversification proves particularly valuable given the region’s vulnerability to climate variability, market volatility for commodity crops like tea and coffee, and increasing input costs for intensive vegetable cultivation. The additional 14.7% average profit increase from carbon revenues thus represents meaningful supplementary income without creating dependence on volatile carbon markets.

4.6.2 Transaction costs and scale economies: critical barriers for smallholders

Our analysis revealed that agroforestry projects smaller than 35 hectares face prohibitive transaction costs exceeding potential carbon revenues at current market prices (mean US$12.40/tCO₂e). Given that the average landholding among scheduled caste communities in the Nilgiris is only 0.8 ± 0.3 hectares, this threshold creates a fundamental accessibility challenge requiring aggregation of approximately 44 smallholder farms to achieve viability.

This finding echoes concerns raised across global carbon market literature about inequitable access for smallholders. The fixed cost structure of carbon project development—including baseline studies, monitoring protocols, verification, and certification—creates regressive cost burdens where per-hectare costs decline sharply with project scale. Our regression analysis quantified this relationship (r = −0.78, p < 0.001), showing that each 10-fold increase in project area associates with a 45.2% decrease in per-ton transaction costs.

Three strategies could mitigate these barriers in the Nilgiris context. First, simplified MRV (Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification) systems using community-based monitoring with digital tools could reduce costs by 45–60%, potentially bringing transaction costs down to US$3.5–7.5/tCO₂e from current levels. Second, standardized project templates and pre-approved methodologies could reduce development costs by 30–40%. Third, collective certification approaches spreading verification costs across multiple small projects could achieve 25–35% cost reductions. These interventions would substantially improve accessibility for marginalized communities while maintaining environmental integrity.

4.6.3 Valuation methodologies: reconciling market and social costs

Our review identified significant discrepancies between carbon valuation approaches, with social cost of carbon methods (mean US$86.20/tCO₂e) producing valuations approximately 7 times higher than market-based approaches (mean US$12.40/tCO₂e). This disparity, confirmed by Keerthika and Parthiban's (2022) Nilgiris-specific study shows carbon market and payment is still a debatable issue, i.e., should farmers be paid for carbon storage in standing biomass. Therefore, their study suggested that, the policymakers should take into account the smallholder farmers interest and profitability and also to achieve the REDD + initiative, mainly in low-income and developing countries.

Market prices reflect current voluntary carbon market transactions, influenced by supply–demand dynamics, project type preferences, and certification requirements. Social cost of carbon estimates attempt to quantify the full economic damages from carbon emissions, including climate impacts on agriculture, health, infrastructure, and ecosystems. The gap between these valuations suggests that current carbon markets substantially undervalue the true societal benefits of carbon sequestration, creating potential for market failures where socially beneficial projects remain economically unviable under market prices.

For the Nilgiris, this valuation gap carries equity implications. If carbon prices were aligned with social cost estimates, the additional revenue would improve project viability for smallholders and justify more comprehensive support mechanisms. However, until market prices rise substantially, policy interventions must bridge this gap through subsidies, technical assistance, or domestic carbon pricing mechanisms that internalize broader social benefits.

4.7 Ecological factors and mechanisms: unpacking the Nilgiris carbon dynamics

4.7.1 Temperature-growth relationships across the elevation gradient

The primary driver of our observed elevation-carbon relationship is the temperature gradient, with mean annual temperatures decreasing approximately 0.6 °C per 100 m elevation increase. Our meta-regression coefficient for temperature (+0.312 Mg C/ha/year per °C) quantifies how this gradient directly constrains carbon accumulation. This relationship reflects fundamental physiological processes, as enzymatic activity and photosynthetic rates decline at lower temperatures, limiting primary productivity at higher elevations around Ooty (>2,000 m) compared to warmer lower elevations near Gudalur.

Higher elevations also experience shorter effective growing seasons due to increased frequency of cool, cloudy conditions and occasional frost events above 2000 m. Reduced photosynthetically active radiation from increased cloud cover at higher elevations further constrains primary productivity. These limitations particularly affect agricultural crops, which show pronounced sensitivity to temperature variations, with C3 crops (predominant in the Nilgiris including vegetables, tea, and most fruit trees) exhibiting reduced photosynthetic efficiency below optimal temperature ranges (20–25 °C).

4.7.2 Soil development and edaphic factors

Soil characteristics change dramatically across the Nilgiris elevation gradient, influencing carbon storage potential through multiple pathways. Higher elevations typically feature shallower soil profiles due to increased erosion and slower weathering rates, higher soil organic matter content per unit volume but reduced total soil depth, altered pH regimes with increasing acidity affecting nutrient availability, and different clay mineralogy influencing carbon stabilization mechanisms. These edaphic factors interact with climate to create elevation-specific constraints on both soil carbon accumulation and plant growth rates.

Soil texture plays a crucial role in carbon stabilization, with fine-textured soils (clays) generally having greater capacity to preserve organic carbon from microbial attack compared to coarse-textured soils. Research by Nair et al. (2010) revealed that Agroforestry systems (AFSs) are believed to have a higher potential to sequester carbon (C) because of their perceived ability for greater capture and utilization of growth resources (light, nutrients, and water) than single-species crop or pasture systems. Furthermore, tree-based agricultural systems, compared to treeless systems, stored more C in deeper soil layers near the tree than away from the tree; higher soil organic carbon content was associated with higher species richness and tree density; and C3 plants (trees) contributed to more C in the silt- + clay-sized (<53 μm diameter) fractions—that constitute more stable C—than C4 plants in deeper soil profiles. The extent of C sequestered in AFSs depends to a great extent on environmental conditions and system management. In Nilgiris agroforestry system, C3 plants (trees) contributed more carbon to stable silt + clay-sized fractions (<53 μm) than C4 plants in deeper profiles.

4.7.3 Species composition and functional diversity along the gradient

Huera-Lucero et al. (2024) demonstrated the importance of conserving the remnants of tropical forests that still remain, due to the diversity of species, ecosystem services, and the total carbon they contain, as well as the agroforestry systems (AFS), systems analogous to forests, which are gradually becoming important management systems, especially if they are associated with potential species to sequester carbon. The elevation gradient across the Nilgiris supports distinct vegetation zones with different carbon accumulation potentials. Lower elevations (900–1,500 m) are dominated by fast-growing deciduous and semi-evergreen species with higher growth rates. Middle elevations (1,500–2,000 m) support mixed forests with moderate growth rates. Higher elevations (>2,000 m) host slower-growing montane species adapted to cooler conditions. This species turnover directly affects carbon sequestration potential, as faster-growing species at lower elevations contribute more significantly to annual carbon accumulation than slower-growing montane species.

Mixing tree species in forests also favors the storage of SOC, provided that a biomass over-yielding occurs in mixed forests (Augusto and Boča, 2022). Fast-growing species like eucalyptus and Acacia offer rapid biomass accumulation (as evidenced by the 12.7 Mg C/ha/year documented for eucalyptus systems in the Nilgiris), while slower-growing hardwoods may provide more stable, long-term carbon storage. The variation in carbon content among tree species (44.2–49.7% of dry biomass) documented in the Nilgiris, though relatively modest, interacts with growth rate differences to influence overall sequestration potential.

4.7.4 Microbial and biological mediators of carbon cycling

Recent research has highlighted the critical role of soil microorganisms in mediating carbon dynamics. Mazumder et al. (2025) demonstrated that Agroforestry systems in temperate climates stored higher biomass and soil carbon stocks than those in tropical climates. Agroforestry systems in subtropical climates achieved higher biomass and soil carbon sequestration rates compared to tropical and temperate regions. Agroforestry systems stored higher biomass carbon stocks on Gleysols, while those on Arenosols stored higher SOC stocks. The significant increase in SOC amount with the increase in slope, altitude, and crown cover helps to understand the extent of SOC distribution in forests. Broadleaved forests with a larger canopy cover in the higher altitude region have a higher SOC retention potential, which is likely to contribute to mitigating the impacts of climate change by sinking more carbon into the soil (Malla and Neupane, 2024).

Agroforestry alters soil microbial community composition and enzyme activities with consequences for SOC sequestration. The Nilgiris’ moderate temperatures (15–25 °C at most elevations) and adequate moisture create conditions favoring rapid decomposition, which both facilitates nutrient cycling supporting plant growth and limits soil carbon accumulation rates despite high inputs. This dynamic helps explain why our soil carbon sequestration rates fall below global benchmarks despite favorable climatic conditions overall—the same warmth and moisture that promote plant productivity also accelerate decomposition processes.

4.8 Distinguishing carbon stocks from sequestration rates: clarifying measurement scales

A critical distinction must be maintained between carbon stocks (total carbon stored at a point in time, measured in Mg C/ha) and sequestration rates (annual carbon accumulation, measured in Mg C/ha/year). Our analysis primarily focused on annual carbon sequestration rates, yielding weighted means of 7.43 Mg C/ha/year for tree components, 0.92 Mg C/ha/year for soil, and 8.67 Mg C/ha/year for total systems. The reference to 38.11 Mg C/ha for agri-horticulture systems represents total carbon stock, not annual sequestration rate.

When examining total carbon stocks rather than sequestration rates, typical Nilgiris agroforestry systems contain soil carbon stocks of 40–120 Mg C/ha, aboveground vegetation stocks of 25–60 Mg C/ha, and total system stocks of 65–180 Mg C/ha. These values align with established literature showing soil as the dominant carbon pool, consistent with global patterns where Mazumder et al. (2025) confirmed that agroforestry systems store 3–4 times more carbon in soil than in biomass components.

The lower annual soil carbon sequestration rates compared to vegetation rates reflect different temporal dynamics rather than indicating soil’s lesser importance. Vegetation carbon accumulates rapidly in young, fast-growing trees during establishment phases. Soil carbon accumulates more slowly but represents longer-term storage with greater permanence. Equilibration time for soil carbon pools may require 20–50 years in newly established agroforestry systems, meaning that annual sequestration rates favor vegetation over soil in recently established systems, while mature systems show soil as the dominant carbon pool by total stock.

4.9 Global carbon sequestration potential: positioning Nilgiris contributions

Our findings contribute to understanding global carbon sequestration potential through agroforestry systems. Zomer et al. (2022) estimated that increasing global tree cover on agricultural land by 10% would sequester more than 18 PgC, with South America, Southeast Asia, West and Central Africa, and North America showing the highest potential. India, including regions like the Nilgiris, represents substantial opportunities within this global framework.

With approximately 25.32 million hectares under agroforestry nationally (Ghale et al., 2022), India’s agroforestry systems constitute a significant component of global carbon sequestration infrastructure. The Nilgiris district, with an area of 2,549 km2 and significant agricultural land suitable for agroforestry expansion, could meaningfully contribute to both national and global carbon mitigation goals. Applying our sequestration rates (8.67 Mg C/ha/year total system average) to potential expansion areas yields substantial carbon accumulation potential over multi-decade time frames.