Abstract

Balancing multiple forest management objectives requires integrating ecological, economic, and social priorities among diverse stakeholders with conflicting interests. Despite advances in optimization and participatory approaches, limited attention has been given to combining stakeholder-informed multi-criteria decision analysis with linear programming (LP) optimization to evaluate landscape-level forest management scenarios. To address this gap, this study aims to evaluate and rank landscape-level management planning scenarios in Vale do Sousa, a region in northwestern Portugal. The evaluation is based on stakeholders’ preferences using a hybrid decision-support framework that combines optimization and participatory approaches. Five management scenarios were developed using LP, each maximizing or minimizing a single ecosystem service. Stakeholder preferences were elicited through an Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) survey, in which 25 participants weighed stand-level forest management models and associated ecosystem services. These weights were incorporated into a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) implemented in Criterium Decision Plus (CDP). The results show that stakeholders’ preferences strongly influence the ranking of landscape-level scenarios. The scenario maximizing timber production ranked highest under stakeholder-weight evaluations, whereas maximizing wildfire resistance emerged as the top-ranked under equal weighting conditions. These findings demonstrate the value of integrating stakeholder-informed preferences with optimization-based scenario evaluation. This study is among the first to integrate AHP-based stakeholder preferences with LP optimization to rank landscape scenarios.

1 Introduction

Forest ecosystem management involves addressing a range of economic, social, and ecological objectives, often involving multiple stakeholders with conflicting interests (Varma et al., 2000; Kangas and Kangas, 2005; Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2014). Over the past decade, natural resource management, particularly forestry, has evolved significantly. Forests are managed for multiple purposes, such as generating revenue while simultaneously promoting conservation and recreational use (Kangas and Kangas, 2005). This shift demands the evaluation of the impact of management decisions on a broad range of forest attributes related to biodiversity, timber production, carbon storage, and other ecosystem services (Seely et al., 2004). However, decision-making among a wide range of competing forest management objectives is one of the most important challenges for forest managers (Ager et al., 2021; Palaiologou et al., 2020). Various optimization techniques, such as linear programming (LP), integer programming, dynamic programming, and mixed-integer programming, are available to address the issue of forest management planning with multiple objectives (Marques et al., 2020; Diaz-Balteiro and Romero, 2008), and to provide a range of feasible solutions for decision-making (Mohammadi et al., 2017).

LP is a mathematical optimization technique used to find the best possible solution to a problem defined by a set of linear equations and constraints. It has long been applied to forest planning for harvest scheduling, resource allocation, and long-term scenario analysis (Jamnick, 1990; Weintraub and Romero, 2006; Baskent and Küçüker, 2010; Bettinger et al., 2016; Borges et al., 2014; Marques et al., 2020). Recent applications (Li et al., 2021; Amiri and Mohammadi Limaei, 2024; Abate et al., 2025) further extend LP to balance ecological and economic goals using single and multi-objective frameworks.

To address the complexities of forest management, decision support systems (DSSs) have emerged as essential tools. These systems integrate diverse data, models, and methods to guide informed decision-making (Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2014; Garcia-Gonzalo and Borges, 2019). DSSs have been further enhanced by incorporating advanced approaches like Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) methods, which facilitate and improve the decision-making process (Uhde et al., 2015). Belton and Stewart (2002) defined MCDA as “an umbrella term to describe a collection of formal approaches which seek to take explicit account of multiple criteria in helping individuals or groups explore decisions that matter.” It serves as a powerful framework for prioritizing and evaluating alternatives that align with stakeholders’ interests and preferences, even when agreement among stakeholders is not reached (Uhde et al., 2015). Numerous research articles (e.g., Nordström et al., 2010; Acosta and Corral, 2017; Başkent and Balci, 2024) and scientific reviews (e.g., Kangas and Kangas, 2005; Mendoza and Martins, 2006; Uhde et al., 2015; Blagojević et al., 2019) have been published on the application of MCDA in natural resources management. Among the various MCDA techniques, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) has been recognized as a valid tool for participatory forest planning as it accommodates conflicting management objectives and also enhances the transparency and credibility of the decision-making process (Ananda, 2007).

The evolution of MCDA methods has also been characterized by combining different MCDA methods and their integration with other approaches, i.e., Hybrid methods (Mardani et al., 2017; Uhde et al., 2015). Previous studies (e.g., Kangas et al., 2000; Huth et al., 2004; Díaz-Balteiro et al., 2009; Nordström et al., 2013; Marques et al., 2021b) have demonstrated the effectiveness of the combination of MCDA with other approaches in forest management planning. For instance, Grazhdani (2024) combined Fuzzy AHP, goal programming, and participatory surveys to rank forest-management scenarios, while Çağlayan et al. (2021) integrated Sustainable Development Goal targets and ecosystem-service suitability values with MCDA and integer programming. These examples demonstrate the flexibility of hybrid MCDA methods to combine stakeholder input with quantitative analysis.

In MCDA applications, Criterium Decision Plus (CDP) has been increasingly adopted due to its structured hierarchical framework and its capability to integrate criterion weights derived from the AHP (Lakićević et al., 2019). CDP has been applied in various forest-related contexts, such as identifying preferred forest management models (Marques et al., 2021b), recommending optimal combinations of management alternatives (Marto et al., 2018), and evaluating environmental quality outcomes (Abelson et al., 2021). It has also been used to rank forest use suitability alternatives based on ecosystem service metrics (Krsnik et al., 2024b), prioritize areas for fire suppression (Gonzalez-Olabarria et al., 2019), and support abbreviated AHP comparisons (Lakićević et al., 2019).

Building on these applications, recent studies have emphasized the importance of integrating decision-making approaches across planning scales. Marto et al. (2018) highlighted the potential for combining decision-making approaches to address stakeholders’ preferences when designing landscapes, while Botequim et al. (2021) discussed the relevance of stand-level management models as key pieces of the landscape mosaic. Some authors (e.g., Tóth and McDill, 2009; Borges et al., 2017) have applied a posteriori preference modeling approaches (e.g., Pareto Frontier methods) to acknowledge stakeholders’ objectives in landscape-level management planning. These hard-operation research techniques efficiently explore trade-offs among objectives, but generally offer limited integration of stakeholder preferences. In contrast, more recent studies have focused on participatory and multi-criteria approaches rooted in soft operations research (Li et al., 2024). Casados et al. (2025) and Rodríguez-Fernández et al. (2025) applied such approaches to forest restoration and wildfire prevention, respectively. Although these studies successfully engaged stakeholders, they did not combine participatory evaluation with optimization-based scenario analysis. This study bridges these paradigms by integrating hard operations research (LP optimization) with soft operations research (stakeholder-informed multi-criteria analysis) to rank landscape-level management planning scenarios derived from optimization results. Therefore, the central research question guiding this study is:

How do stakeholder priorities regarding stand-level forest management models and associated ecosystem services influence the ranking of LP-optimized landscape-level management planning scenarios?

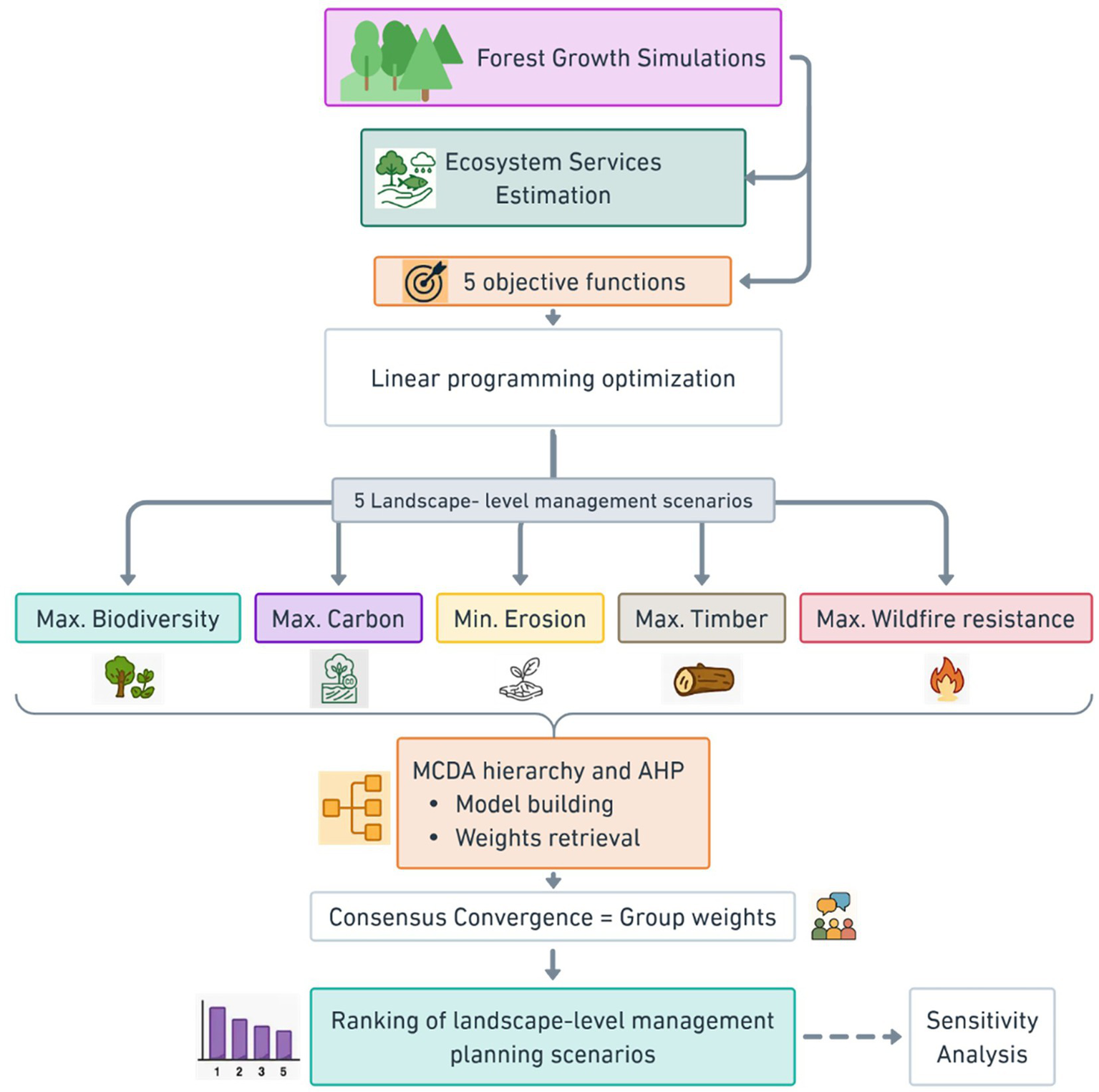

To address this question, the study aims to evaluate how stakeholder preferences shape the prioritization of landscape-level management planning scenarios. Specifically, it seeks to (i) assess how stakeholders value different stand-level management models and the provision of several ecosystem services associated with them, (ii) derive consensus-based weights that represent these preferences, and (iii) use these weights within a multi-criteria decision analysis framework to rank five LP-optimized management scenarios (Figure 1). The decision framework is structured around stand-level forest management models (criteria) and five key ecosystem service indicators (sub-criteria). A control framework in which all stand-level management models and ecosystem services are assigned equal weights is also included for comparison. By linking stakeholder values regarding the relative importance of landscape mosaic pieces (criteria) and of the ecosystem services to be provided (sub-criteria) by the mosaics with model-based outcomes, the study provides the basis for identifying the landscape management scenario that is more aligned with local priorities.

Figure 1

Methodological workflow.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Case study area

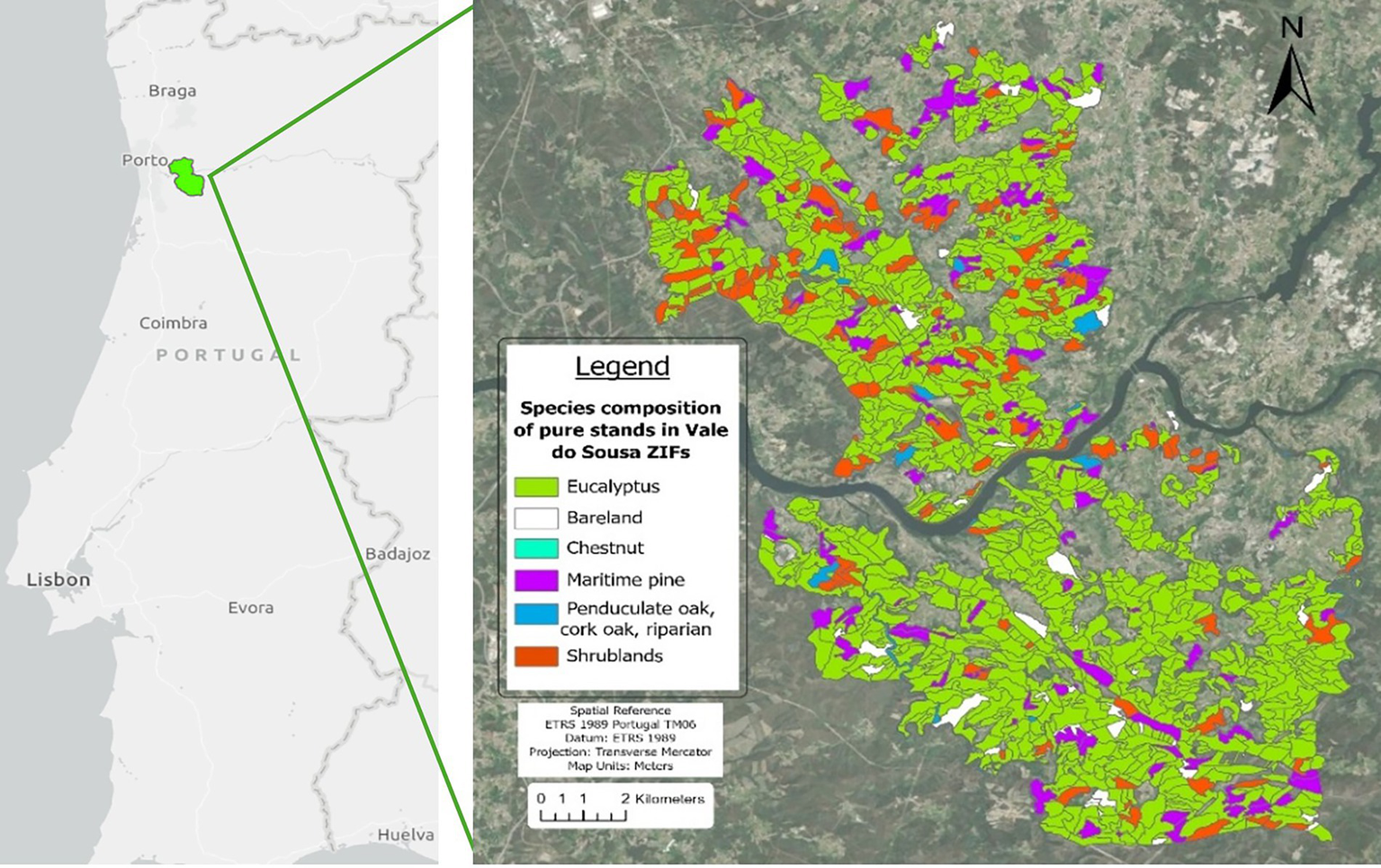

Vale do Sousa (Figure 2), situated 50 km east of Porto, represents the forestry scenarios of northwestern Portugal, particularly in terms of species composition and ownership structure (Novais and Canadas, 2010; ICNF, 2013). It covers an area of approximately 13,104 hectares and is divided into 1,300 management units (MUs). Moreover, the area considered for this study is delineated into two distinct ZIF areas (joint collaborative management areas) that are separated by the Douro River: Entre-Douro-e-Sousa (North of the Douro River) and Paiva (South of the Douro River). A local forest owners’ association, Associação Florestal de Vale do Sousa (AFVS), is the primary entity responsible for developing joint management strategies for ZIF areas within this region.

Figure 2

Case study area (Vale do Sousa).

Current stand-level forest management models (cFMMs) in the case study area include Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus Labill, cFMM1) and maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aiton, cFMM2), which are the predominant species of the landscape, while a minimal fraction is occupied by hardwood, mainly chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) stands (Figure 2). Furthermore, alternative forest management models (aFMMs) have been proposed to address the challenges of wildfire risk and to ensure the sustainable provision of ecosystem services (Agestam et al., 2018; Marques et al., 2020a; Marques et al., 2020b). These include a transition toward lower-density maritime pine plantations, cork oak (Quercus suber L., aFMM4), and the introduction of pure stands of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L., aFMM5). The silvicultural prescriptions considered under each cFMMs and aFMMs are explained in Annex A.

2.2 Forest growth simulations

The growth and yield simulations were done using the StandsSIM.md tool (Barreiro et al., 2016), available in the sIMfLOR platform, which was developed to encompass the main timber-producing species in Portugal. Understanding how the stand will grow and assessing the impact of silvicultural operations on its growth are essential components of future management planning (Burkhart and Tomé, 2012). Thus, the standsSIM.md tool was used to project stand growth along the rotation age of each species, based on the predefined set of forest management prescriptions. The forest management prescriptions for all species considered in this study were consistent with those described by Botequim et al. (2021) (Annex A).

Eucalyptus globulus L. and Pinus pinaster A. growth was projected using the Globulus 3.0 and Pinaster models, both incorporated within the standsSim-MD module (Barreiro et al., 2016). For Quercus suber, the SUBER v5.0 model (Paulo et al., 2011), also integrated into the same platform, was employed for the growth projection. Additionally, the SimGaliza simulator (Gómez-García et al., 2016), designed for Quercus robur stands in Galicia (Spain), was used, considering the similar soil and climatic conditions of that region alongside our case study area. The yield tables provided by Patrício (2006) and Filipe (2019) were used as references for Castanea sativa M. A total of 77,592 prescriptions were generated by combining the management scenarios with the land units over a 50-year planning horizon. This duration is consistent with landscape-level planning in Portugal (e.g., Borges et al., 2017; Cabral et al., 2022; Abate et al., 2024) and spans one or more silvicultural cycles for short- and medium-rotation species common in the study area (e.g., Eucalyptus globulus, Pinus pinaster, Castanea sativa). In addition, during preliminary discussions, stakeholders expressed that planning horizons of 100 years were too distant to meaningfully assess, demanding a shorter planning horizon to be able to have sensitivity while analyzing the results. Moreover, shorter horizons would not adequately capture the development of ecosystem services. Although regional forest management plans in Portugal operate on administrative cycles of up to 20 years, these do not reflect ecological rotation lengths or the temporal scale at which ecosystem service outcomes materialize. Therefore, the 50-year horizon was adopted as a balanced analytical timeframe that reflects both ecological processes and stakeholder decision relevance.

2.3 Estimation of ecosystem services

The study considers five ecosystem services or indicators: biodiversity, carbon stock, wildfire resistance, timber production, and soil erosion. These ecosystem services were selected because (i) they represent priority management goals identified in prior regional planning and stakeholder engagement processes (e.g., Marto et al., 2018; Marques et al., 2021a), and (ii) they are supported by available and comparable biophysical indicators derived from forest growth, fuel, and site condition data. Various methods were applied to estimate the provision of these ecosystem services. Growth models and simulation tools, mentioned above (2.2), were used to quantify wood production and carbon stocks. The estimation of fire resistance was conducted using the indicator formulated by Ferreira et al. (2015), which integrates wildfire occurrence and damage models specifically developed for the predominant forest species in Portugal. It incorporates further spatial information, such as the configuration of the stand and spatial context. The values associated with this indicator originally range between 0 and 1. These values are then converted into classes (from 1 to 5) based on percentiles, where a score of 5 indicates the highest resistance. For the estimation of soil erosion, the approach proposed by Rodrigues et al. (2021) was adopted, wherein the authors employed the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE: Renard et al., 1991) to estimate potential annual loss. The biodiversity value was estimated using the methodology developed by Botequim et al. (2021). This indicator encompasses species composition, forest structure/age, and shrub biomass. The biodiversity index ranges from 0 to 8, where 8 represents the highest level of biodiversity.

2.4 The optimization model building

Five landscape-level management planning scenarios were generated by solving five LP problems, each maximizing a different ecosystem service: (i) biodiversity, (ii) carbon stock, (iii) timber supply, (iv) wildfire resistance, and (v) minimize soil erosion. For that purpose, the five problems were formulated based on Model I (Johnson and Scheurman, 1977), with a continuous decision variable Xij, representing the area (ha) of management unit i allocated to the stand-level management prescription j.

The general structure of the optimization model was:

Where:

-

is the area of management unit i assigned to prescription j (decision variable).

-

is Performance value of unit i under prescription j for the ecosystem service being optimized (e.g., carbon stock, timber volume).

-

Z is the Objective function value.

Subject to:

-

1. Total area constraint (every management unit must be allocated to a prescription)

-

2. Non-negativity

The equations used to define the optimization problem for ecosystem services, carbon stock, wildfire resistance, timber production, and soil erosion, in this study, are consistent with those presented by Marques et al. (2024). In addition, biodiversity was considered as one of the additional ecosystem services in this study. A complete description of the decision variables, objective function, and constraints of all ecosystem services is provided in Annex B. For further details regarding the formulation of this optimization model for these ecosystem services, readers are encouraged to refer to the work of Marques et al. (2024).

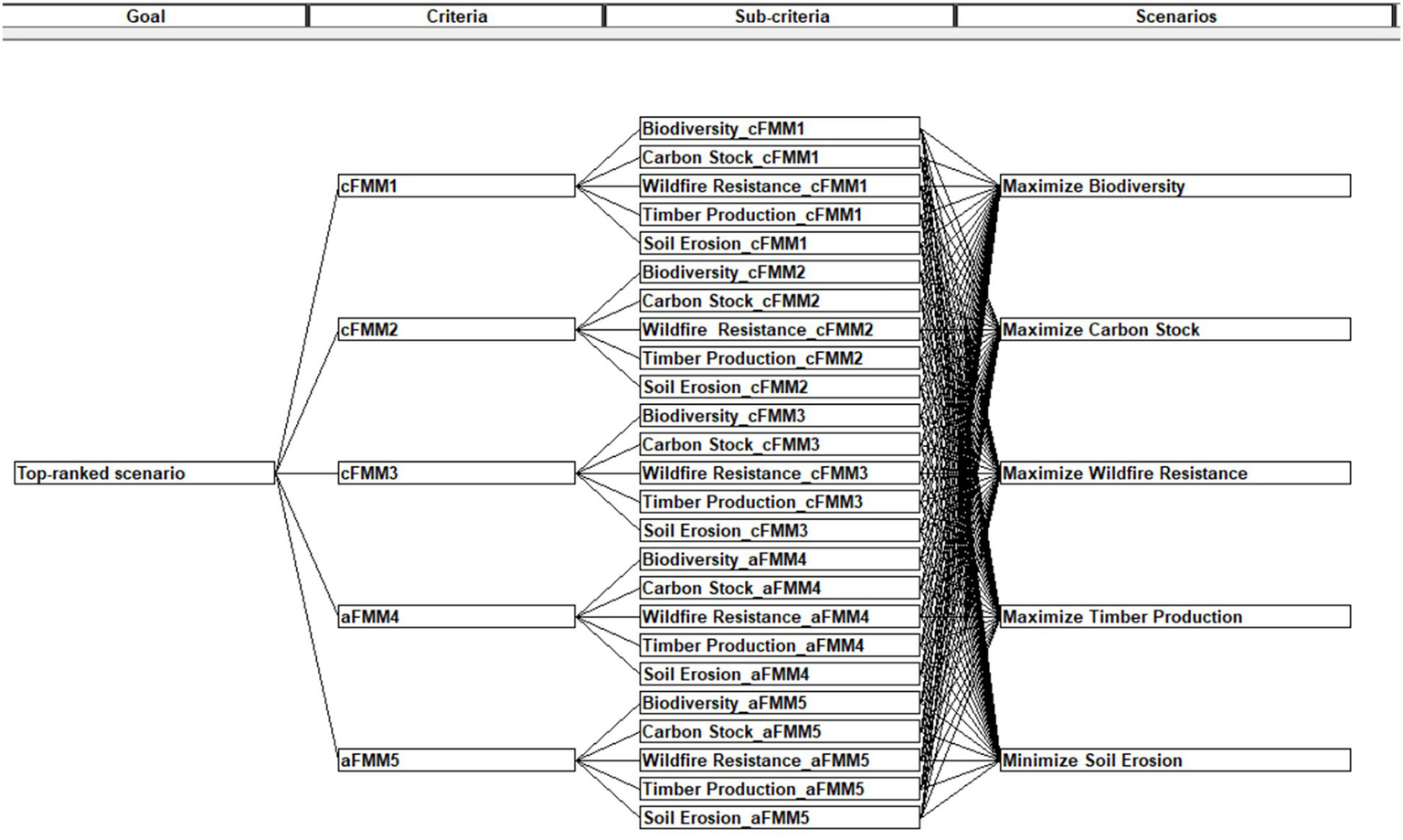

2.5 Decision hierarchy and stakeholder questionnaire

A decision hierarchy (Figure 3) was built using the CDP software (Murphy, 2014) to define the model for evaluating the landscape-level management planning scenarios. The hierarchy was structured into three levels: five stand-level forest management models represented the criteria, five ecosystem services were defined as sub-criteria (replicated under each management model), and the final level comprised the five landscape-level scenarios to be ranked. Five stand-level forest management models, eucalyptus, maritime pine, chestnut, pedunculate oak, and cork oak, were selected as criteria for this study to represent both current and alternative forest management models (Annex A). In addition, five ecosystem services were chosen as sub-criteria, based on stakeholder preferences reported by Marques et al. (2021a) and Marto et al. (2018). The set includes wood production, biodiversity conservation, erosion control, carbon storage, and wildfire resistance.

Figure 3

Decision hierarchy built using CDP. cFMMl, cFMM2, cFMM3, aFMM4, and aFMM5 account for stand-level management models for Eucalyptus, Maritime pine, Chestnut, Cork oak, and Pedunculate oak, respectively.

Following the development of the hierarchy, a questionnaire survey was designed to assess the relative importance stakeholders assign to each criterion and sub-criterion. To streamline the comparison of criteria and sub-criteria, the abbreviated pairwise comparison technique within CDP was used, which reduces the number of necessary comparisons while maintaining accuracy (Marques et al., 2021b). The questionnaire was created using Google Forms and distributed via email.

A total of 57 stakeholders were selected for the survey based on a list recommended by AFVS. The selection focused on individuals involved in forestry and capable of influencing forest management, either directly or indirectly. The goal was to ensure representation across groups with different roles and interests in the landscape. Four stakeholder categories were represented: 20 representatives from civil society, 11 forest owners, 13 market agents, and 13 from the public administration. For the criteria, stakeholders were asked to assign the relative importance of each stand-level forest management model in comparison to others. For the sub-criteria, they were asked to compare the relative importance of the five ecosystem services within each criteria group. The questionnaire used for this purpose is presented in Annex C. A 9-point scale was provided, with numerical values ranging from 1 (equally relevant) to 9 (extremely relevant), along with corresponding verbal descriptions to guide their assessments.

2.6 Consensus convergence model

After collecting the survey responses, the consensus convergence model (Annex D) was used to assess the level of agreement among individuals within a group based on the weights they assign to decision criteria. Typically, this model includes two components: (1) the criterion weights provided by each participant, which reflect their views on the importance of each criterion, and (2) the weights of respect, where each participant rates how much they value or trust the opinions of other members in the group. These respect weights are then used to adjust how individual judgments influence the group consensus (Regan et al., 2006). However, the use of respect weights poses several practical limitations. It requires each participant to assess all other members, which is time-consuming and may lead to biased or strategic responses. Moreover, assigning numerical values to interpersonal respect can be abstract, uncomfortable, and potentially disruptive to group dynamics (Regan et al., 2006). In this study, a simplified version of the consensus convergence model that relies solely on the criterion weights provided by each participant was adopted. This approach estimates consensus based on the degree of similarity in the importance assigned to criteria across individuals within each interest group.

The consensus aggregation proceeds iteratively as follows. For a given group of stakeholders and criterion k, an influence matrix W is constructed:

where and represent the weights assigned to criterion k by stakeholders i and j. Higher similarity results in greater mutual influence.

An initial weight vector is randomly generated and updated iteratively as:

until convergence when:

The final consensus vector is then normalized:

The resulting vector P represents the consensus weight for criterion k. This process is repeated for each criterion, producing a full consensus weight vector. Finally, the consensus weights are normalized so that they sum to 1. The resulting weights from this process served as the foundation for the MCDA model implemented in CDP.

2.7 Evaluation of landscape-level management planning scenarios

After deriving the consensus weights described in Section 2.6, these were inserted into the CDP software to evaluate the landscape-level management planning scenarios (Approach 1). This process combined the aggregated stakeholder preferences for both criteria and sub-criteria with the performance data obtained from the LP optimization. In parallel, a second model was run, allocating equal weights to all criteria and sub-criteria (Approach 2), serving as a control scenario for comparison.

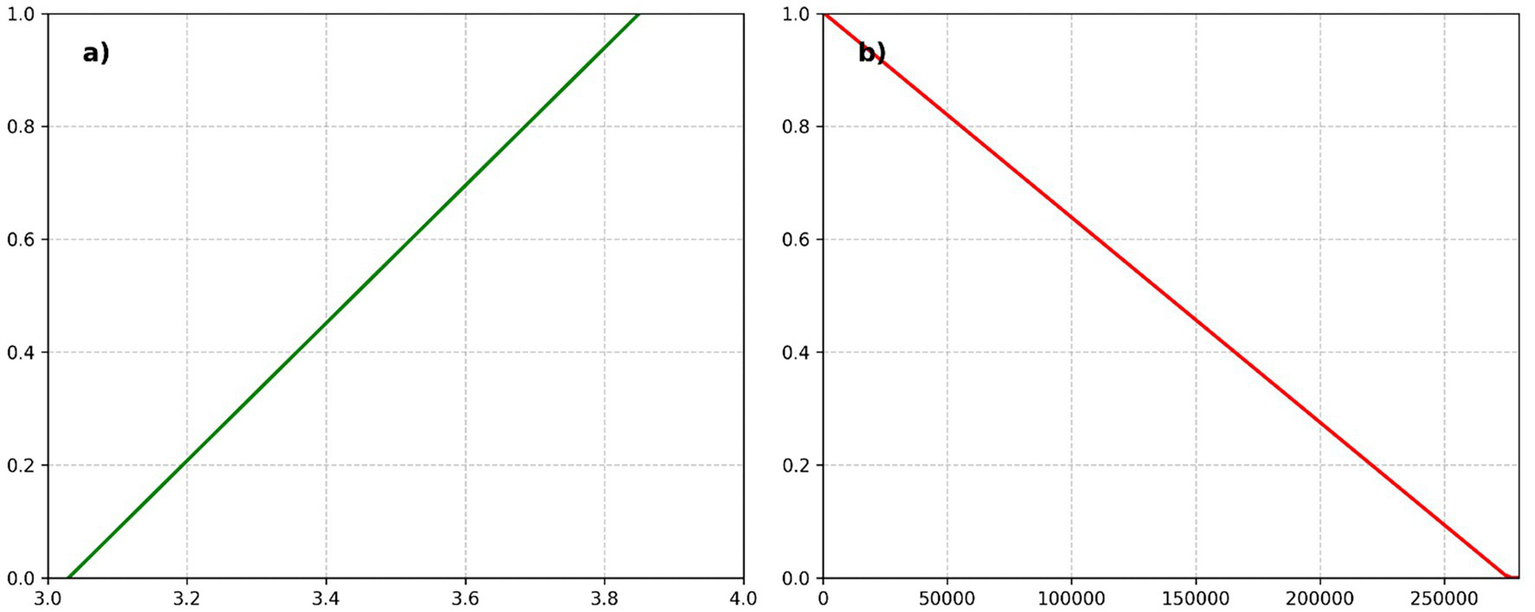

The data extracted from LP solutions had varying units and scales (e.g., carbon stock in tons and timber production in m3). However, within the CDP framework, the rating technique addresses this disparity through normalization, wherein all scales are converted to a common internal scale that ranges between 0 and 1. For instance, the graph (Figure 4a) illustrates a positive linear utility function, where a biodiversity value of 3.03 represents utility 0, indicating the least preferred condition. Conversely, a score of 3.85 corresponds to utility 1, meaning the most desirable value. In contrast, the graph (Figure 4b) depicts a negative linear utility function, where a higher soil erosion value represents utility 0, reflecting the least preferred condition, whereas lower erosion values correspond to utility 1.

Figure 4

Linear utility functions for biodiversity (a) and soil erosion (b). Biodiversity is normalized positively (higher values = higher utility), while soil erosion is normalized inversely (lower values = higher utility).

Finally, the decision scores for each scenario were calculated to determine the top-ranked landscape-level management planning scenario. These scores represent an aggregate of all the ratings that were entered into the model.

2.7.1 Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was then conducted to evaluate the robustness of the model in prioritizing the landscape-level management planning scenario. CDP provides a sensitivity analysis technique that involves altering a single weight at a time and subsequently estimating the magnitude of change (criticality) required for the existing top-ranking scenario to be replaced by another (Murphy, 2014). The criticality score serves as an indicator of model sensitivity, providing a metric that describes the extent to which the model is influenced by attribute weighing. Here, lower criticality values signify high sensitivity to the corresponding attribute, whereas higher values indicate the greater robustness of the model. A criticality value of ±10% of the most sensitive criterion is a widely accepted heuristic to evaluate robustness, as proposed by Saaty (1996). Thus, our study considered the model robust if the most sensitive attribute had a critical value of ±10%.

3 Results

3.1 Determination of the contribution of ecosystem services

The linear programming models were solved using CPLEX Interactive Optimizer 12.6.3.0, on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i7 and 12 GB RAM, to find the contribution of each landscape-level management planning scenario to the targeted ecosystem services (Annex E). To help with the visualization and interpretation of the results, relative performance classes (Highest, High, Moderate, Low, Lowest) were derived by comparing the landscape-level values of each ecosystem service across the five management objectives. The highest and lowest values for each service define the scale, and all other objectives were ranked according to their relative position within that range (Table 1).

Table 1

| Landscape objective | Biodiversity | Carbon stock | Fire resistance | Timber volume | Soil erosion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max biodiversity | Highest | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Max carbon stock | Moderate | Highest | Moderate | High | High/very high |

| Max fire resistance | Moderate | Moderate | Highest | Moderate | Moderate |

| Max timber volume | Moderate | High | Moderate | Highest | Very high |

| Min soil erosion | Moderate | Low–moderate | Low–moderate | Low–moderate | Lowest |

Relative performance of ecosystem services under each management objective at the landscape scale.

Full quantitative values are reported in Annex E. Green color indicates consistency between each scenario’s objective and the corresponding ecosystem service outcome.

3.2 Stakeholder participation and weighing of criteria and sub-criteria

Out of the 57 stakeholders contacted, a total of 25 stakeholders responded to the AHP survey. These included nine representatives from civil society, four forest owners, seven market agents, and five representatives from the public administration. These stakeholders assigned weights to the criteria and sub-criteria that were used as input in the CDP model to identify the top-ranked landscape-level management planning scenario.

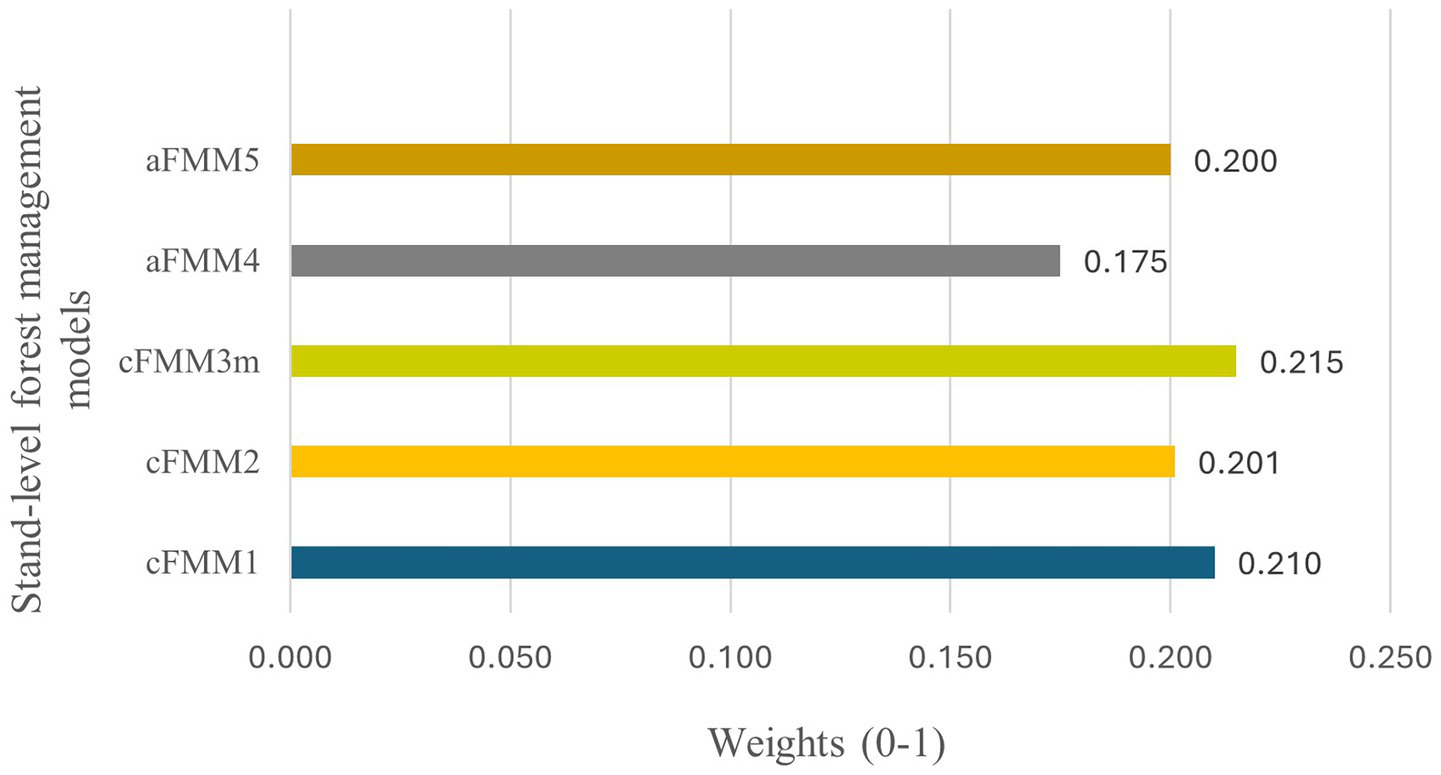

In the case of criteria (Figure 5), cFMM3 received the highest weight (0.215), followed closely by cFMM1 (0.210), while aFMM5 was assigned the lowest weight (0.175). However, the difference in weights between the top two stand-level management models was relatively small.

Figure 5

Stakeholders aggregated weights to criteria.

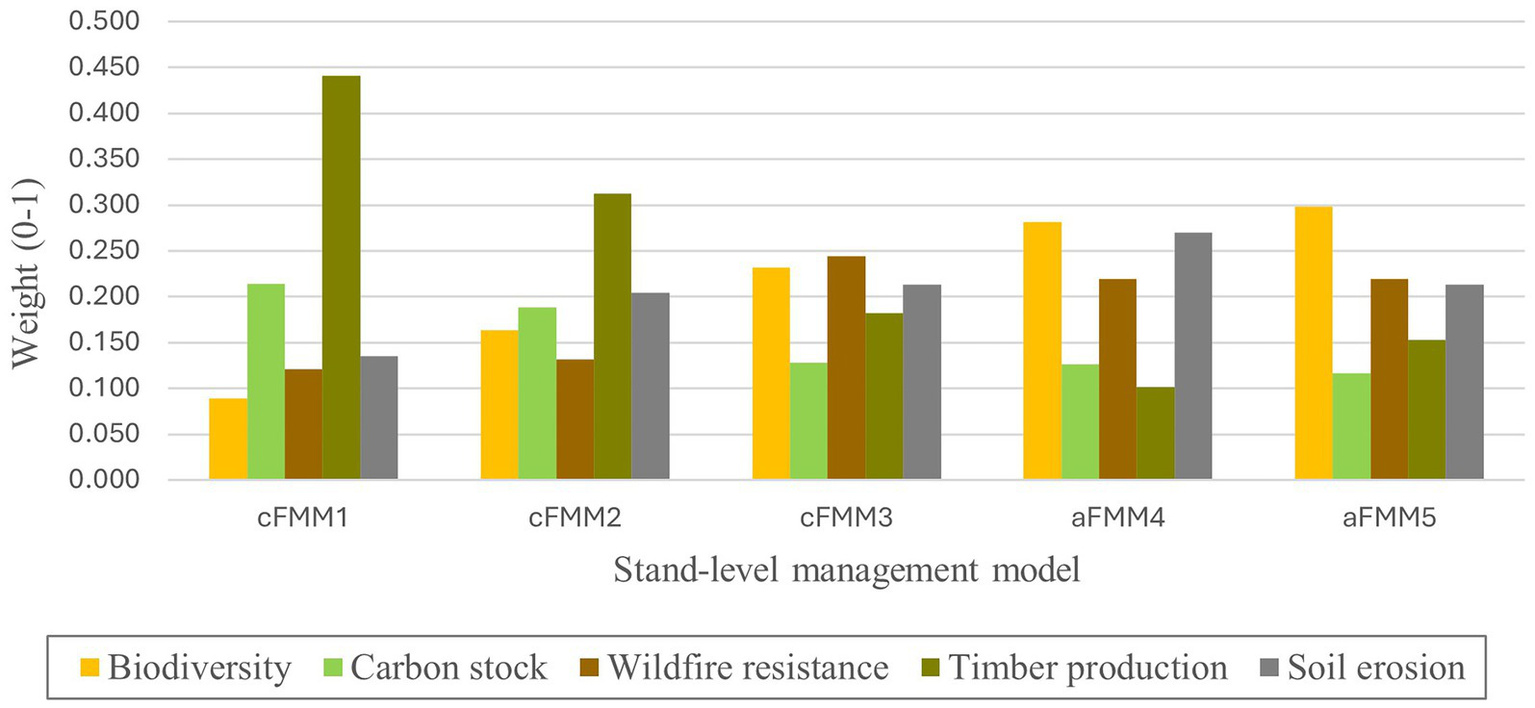

In the case of sub-criteria (Figure 6), cFMM3 was assigned the highest weight to address wildfire resistance (0.244). Similarly, cFMM2 and cFMM1 were preferred for timber production, with weights of 0.312 and 0.441, respectively. In contrast, for aFMM5 and aFMM4, the biodiversity sub-criterion was given the most weight, with weights of 0.298 and 0.282, respectively.

Figure 6

Stakeholders aggregated weights to sub criteria.

3.3 Evaluation of landscape-level management planning scenarios

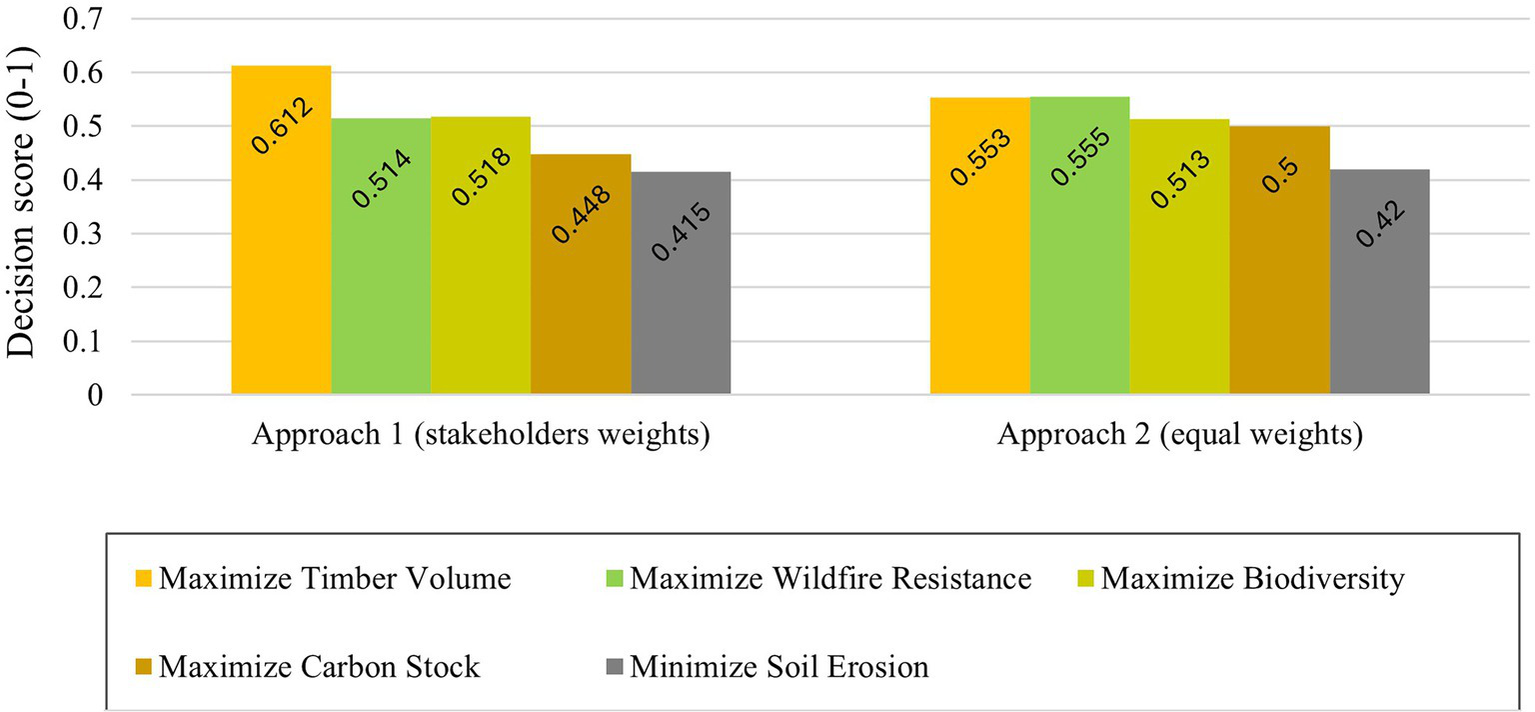

After completing all steps necessary to develop the MCDA model (designing the hierarchy, AHP survey, eliciting weights, and rating landscape-level management planning scenarios against the lowest-level criteria), the decision scores for each scenario and for each interest group were calculated using CDP (Figure 7) for both approaches.

Figure 7

Decision score to landscape-level management planning scenarios.

When stakeholders assigned weights (Figure 7, Approach 1) to criteria and sub-criteria, maximizing timber production achieved the highest decision score (0.612), followed by maximizing wildfire resistance (0.541), while minimizing soil erosion had the lowest score (0.415). However, when equal weights were assigned (Figure 7, Approach 2) to the criteria and sub-criteria, maximizing wildfire resistance (0.555) became the highest-ranked scenario, followed by maximizing timber production (0.553), and minimizing soil erosion remained the least preferred (0.420). However, the variation in decision scores under equal weighting was minimal. The differences in decision scores between the two weighting approaches were relatively small, ranging approximately from 1 to 10%. The largest relative change (~10%) was observed for the timber production scenario, followed by wildfire resistance (~3%), indicating that these objectives were more sensitive to stakeholder-derived weighting assumptions.

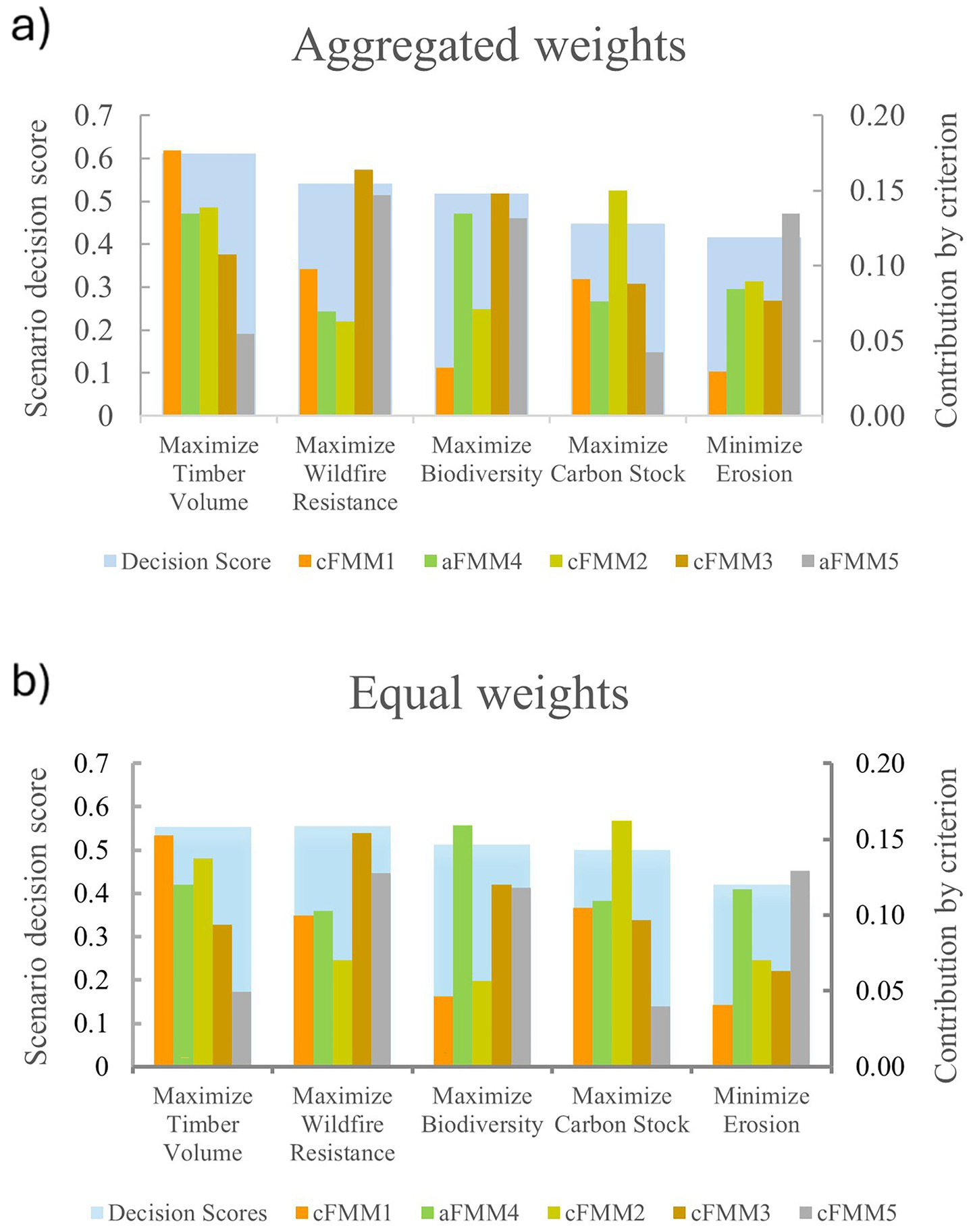

3.4 Analysis of contribution by criteria

To gain deeper insight into the assessment of landscape-level management planning scenarios, the contribution of each criterion to its decision scores was examined. This analysis aimed to identify which criteria had the greatest influence and which played a lesser role in the decision score of the top-ranked planning scenario.

When stakeholders’ assigned weight was considered (Figure 8a), maximizing timber production remained the top-ranked scenario, with cFMM1 (0.177), cFMM2 (0.139), and aFMM4 (0.135) providing the highest contributions. Under the equal weighting approach (Figure 8b), where maximizing wildfire resistance emerged as the most preferred scenario, the leading contributing criteria were cFMM1 (0.153), cFMM2 (0.137), and aFMM4 (0.120), while the remaining two stand-level models (cFMM3 and aFMM5) had a lower influence.

Figure 8

Contribution of criteria to the decision scores: (a) when stakeholder-assigned weights were considered, and (b) when equal weights were considered. The contribution of each management model to the final scenario score reflects its aggregated performance across all ecosystem service indicators, not only the service being maximized in the LP formulation.

3.5 Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis evaluates the robustness of a decision model by determining the extent to which the weight of a sub-criterion must change, referred to as the criticality or crossover value, for the top-ranked management scenario to be replaced by another (Marques et al., 2021b). In this study, a model is considered robust when the criticality of the most sensitive sub-criterion exceeds ±10%. The model, which considered the stakeholders’ assigned weight, showed robustness with a crossover value of 11%. This indicates that the priority score of the second-ranked scenario, i.e., maximize wildfire resistance, would need to increase by 11% to become the top-ranked scenario. In contrast, the model based on equal weights was not robust, as its crossover value did not surpass the threshold.

4 Discussion

Forests are increasingly managed for multiple and often conflicting objectives, such as timber production, biodiversity conservation, wildfire mitigation, and carbon storage, within landscapes (Stenger et al., 2009; Couture et al., 2021). Achieving these objectives requires navigating landscapes where stakeholders hold diverse and often conflicting management priorities and interests (Mendoza and Martins, 2006), which adds considerable complexity to forest decision-making. This study addressed this challenge by utilizing a hybrid decision-support framework that combines LP and MCDA approaches to support decision-making in complex forest landscapes. A stakeholder-informed decision-making approach was implemented, using the AHP, which collected stakeholder preferences through a structured questionnaire.

To briefly summarize the analytical steps applied in this research, five linear optimization models were initially developed, each designed to maximize or minimize a targeted ecosystem service (biodiversity, carbon stock, timber production, wildfire resistance, or soil erosion). Next, the outputs of these models were structured into a hierarchical MCDA framework within CDP, where stakeholders assigned weights to stand-level management models (criteria) and ecosystem services (sub-criteria). The methodological foundation of this research builds on prior applications of LP, which have been widely used for resource allocation and scenario analysis in forestry (Gustafson et al., 2006; Fiorentin et al., 2017; Mohammadi et al., 2017). Likewise, MCDA, particularly the AHP, has proven valuable for incorporating stakeholder values in forest management planning (Maroto et al., 2012; Marques et al., 2021b).

Compared to previous applications of MCDA combined with participatory planning in Portugal, our hybrid LP-MCDA framework introduces a distinct sequencing of optimization and stakeholder evaluation. Borges et al. (2017) relied on participatory workshops integrated with MCDA to negotiate targets for ecosystem services, while Marques et al. (2021b) applied MCDA with stakeholder weights (0–100) in a group decision-making setting, without an optimization step. de Sousa Xavier et al. (2015) advanced further by integrating compromise programming and extended goal programming to derive consensus weights for wildfire risk mitigation in southern Portugal. In contrast, our study employs linear programming to generate a set of optimized landscape-level scenarios, each maximizing or minimizing a single ecosystem service independently. These scenarios were then evaluated with MCDA using AHP-derived stakeholder weights. This sequencing ensures that the scenarios reflect clear and objective-specific outcomes from the optimization process. Their final prioritization then captures the value judgments of stakeholders, offering a transparent and generalizable decision-support framework for fragmented forest landscapes. Such a methodological distinction provides the basis for interpreting how stakeholder preferences influenced the prioritization of landscape-level management scenarios in our case study. This became particularly evident when comparing results under stakeholder-assigned versus equal weighting schemes.

When considering contexts with multiple stakeholder groups, such as Vale do Sousa, differences in the relative importance assigned to ecosystem services led to different prioritization outcomes. In our study, the stakeholder-weighted model ranked the scenario that maximizes timber production highest, whereas the equal-weight model favored the maximizing wildfire resistance. The qualitative trade-off summary (Table 1) helps interpret these shifts. The maximize timber scenario provides the highest wood production and high carbon stock, but it also results in very high soil erosion, representing a substantial environmental cost. In contrast, the maximize wildfire resistance scenario shows more balanced outcomes, with moderate provision of wood and carbon and substantially lower erosion impacts, reflecting a more precautionary landscape configuration. The weighting exercise revealed that local actors attribute substantial value to timber-related economic benefits. Integrating these consensus-based weights into the MCDA framework, therefore, not only ranked the LP-optimized scenarios but also made explicit the trade-offs that stakeholders are implicitly accepting, in this case, higher erosion risks in exchange for higher timber revenues. This shift in ranking illustrates how stakeholder preferences shape landscape-level decisions, consistent with findings by Krsnik et al. (2024a).

Examining the contribution of each stand-level management model to the decision scores provides further insight. Under stakeholder-weighted preferences, Eucalyptus globulus L. (cFMM1) and Pinus pinaster A. (cFMM5) contributed most strongly to the top-ranked scenario, reflecting their relevance in the regional forest-based economy. Notably, Quercus suber L. (aFMM4) also played a meaningful role, not because of its timber production, but because cork oak provides balanced co-benefits across ecosystem services, particularly carbon storage, biodiversity, and fire resistance. This demonstrates that the “maximize timber” scenario should not be interpreted as promoting timber in isolation; rather, it represents the scenario offering the highest overall ecosystem service performance once stakeholder priorities are taken into account. In contrast, under equal weighting, ecosystem services were treated uniformly, resulting in maximizing wildfire resistance as the preferred scenario, with less differentiation among stand-level management contributions. This shows that stakeholder values influence not only which landscape-level scenarios are preferred, but also which stand-level forest management models become central to shaping the landscape mosaic.

To better contextualize these outcomes, it is important to consider the economic role of forests in Portugal. Forests cover approximately 36% of the mainland, and the national economy is strongly linked to forest-based products, particularly the pulp and paper industry, which significantly contributes to employment and exports (ICNF, 2019; Pra et al., 2019; Nunes et al., 2019). This economic importance may help explain why stakeholder-weighted preferences in our study prioritized timber production over other management scenarios. Similar trends have been observed in Sweden, where forest owners and officials often emphasize production-oriented practices, such as clear felling, over biodiversity protection (Nordén et al., 2017). By contrast, other studies in Mediterranean contexts highlight stronger preferences for environmental and social services over purely economic returns (Maroto et al., 2012; Martins et al., 2014). In the Vale do Sousa region, the prominence of timber-related economic benefits therefore appears to influence stakeholder valuations, resulting in timber production ranking highest under stakeholder-weighted scenarios.

These results speak directly to the objectives of the study: first, the weighting exercise revealed how stakeholders value the five stand-level management models and their associated ecosystem services; second, the consensus convergence procedure reduced variation in individual judgments, generating a stable shared representation of group preferences; and third, integrating these consensus-based weights into the MCDA framework allowed us to rank the LP-optimized scenarios according to stakeholder priorities.

Lastly, the sensitivity analysis was done to examine how variations in the weights of sub-criteria could influence the ranking of landscape-level management planning scenarios. Following the ±10% criticality threshold recommended by Saaty (1990), the analysis determined the extent to which a weight would need to shift to alter the preferred outcome. While Marto et al. (2018) and Abelson et al. (2022) also adopted a 10% threshold, Marques et al. (2021b) considered a decision model robust if the criticality exceeded 5%. In this study, the stakeholder-weighted model exceeded the threshold with an 11% score, which indicates a stable and robust top-ranked scenario when broader perspectives are incorporated. In contrast, the equal-weight model did not meet the criticality threshold; hence, the resulting model is sensitive to identifying maximizing wildfire resistance as the top-ranked scenario when stakeholders’ preferences are not taken into account.

Overall, this study reinforces the growing evidence that participatory decision-support frameworks enhance both the credibility and acceptance of forest management planning. As argued by Ortiz-Urbina et al. (2022), including diverse stakeholder groups strengthens the legitimacy of management outcomes and facilitates the alignment of ecosystem service priorities with collective goals. By integrating optimization with stakeholder-informed evaluation, the framework provides a transparent tool for balancing different ecosystem services and aligning management actions with multiple stakeholder priorities. While the current application was limited to five stand-level management models and five ecosystem services associated with them, the approach is readily adaptable to broader ecological, social, and economic dimensions, offering a practical pathway for supporting more balanced and widely accepted forest landscape management strategies.

5 Limitations

Despite the strengths of this approach, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the indicator to compute wildfire resistance presents some limitations. While the stand-level indicator reliably captures the resistance of individual stands, the landscape-level indicator accounts for the influence of neighboring stands without ensuring that they share the same land use or species composition. As a result, the wildfire resistance attributed to a given FMM does not fully represent its own contribution, since the resistance of each stand is also influenced by neighboring stands, which may belong to other FMMs. Additionally, the study did not account for spatial configuration, implementation costs, or climate-driven related risks, factors that are increasingly relevant in landscape-level decision-making. However, the selection of a particular landscape-level management planning scenario inherently influences the area allocated to each stand-level management model within that scenario. Stakeholder engagement was limited to a single round, without opportunities for iterative feedback or dialogue. The stakeholder sample, although diverse, was uneven across groups and reflects preferences at a specific point in time, which may evolve with changes in forest policy, market conditions, or wildfire risk perception. Although participation covered multiple stakeholder types, the response rate (25 out of 57) was relatively low, which means the results may not fully represent the range of perspectives in the region. The study considered a simplified set of five ecosystem services, which only partially captures the ecological and social complexity of the region. Finally, the optimization generated single-objective “extreme” scenarios; future work could explore multi-objective or goal programming approaches to directly integrate stakeholder preferences into the optimization stage itself.

6 Conclusion

This study applied an integrated approach combining LP with MCDA to prioritize landscape-level management planning scenarios in Vale do Sousa, Portugal. The objective was to support decision-making in a complex landscape characterized by fragmented ownership and diverse stakeholders concerning timber production, wildfire resistance, biodiversity, carbon storage, and soil protection. The findings highlight the significant influence of stakeholder preferences on management priorities. Under stakeholder-weighted scenarios, maximizing timber production ranked as the top priority, whereas under equal-weight conditions, wildfire resistance emerged as the leading scenario. The results provide a transparent and inclusive framework for selecting landscape-level management planning scenarios that reflect local priorities and collective involvement in decision making. This aligns with resilience-oriented planning pathways promoted under current Portuguese forest policy, European Union’s initiatives as EU Forest Strategy or the ones by the FIRE-RES project, and advances progress toward SDG 15 – sustainable forest management. On the other hand, future research should expand upon this work by incorporating spatial prioritization, dynamic ecological modeling, different climatic scenarios, and cost-effectiveness analysis. Enhancing the process through iterative stakeholder engagement and integrating additional ecosystem services, such as provisioning services (e.g., cork from Quercus suber L. and chestnut fruits from Castanea sativa M.), cultural values, and water regulation, would strengthen the model’s applicability and robustness for real-world forest management challenges.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

SP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SR-F: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KR: Conceptualization, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by two key projects: H2020-LCGD-2020-3/101037419, titled “FIRE-RES -Innovative technologies and socio-ecological economic solutions for fire resilient territories in Europe,” funded by the EU Horizon 2020 -Research and Innovation Framework Programme; and H2020-MSCA-RISE-2020/101007950, titled “DecisionES -Decision Support for the Supply of Ecosystem Services under Global Change,” funded by the Marie Curie International Staff Exchange Scheme.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I. P., through the projects UID/00239/2025 (DOI: 10.54499/UID/00239/2025) and UID/PRR/00239/2025 (DOI: 10.54499/UID/PRR/00239/2025) of the Forest Research Centre, and TERRA Associate Laboratory LA/P/0092/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0092/2020). We are grateful to Jose G. Borges for his invaluable guidance throughout this study. We sincerely like to thank the Associação Florestal de Vale do Sousa (AFVS), particularly Sandra Pinto, for her coordination and the recommendation of the list of stakeholders. We also acknowledge InfoHarvest for providing the CDP software, with special thanks to Philip Murphy for his assistance. Finally, we extend our heartfelt gratitude to all individuals who supported and contributed to this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT (OpenAI) to support the refinement of text segments, including clarity and language editing. After using this tool, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2025.1707550/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AHP, Analytic Hierarchy Process; AFVS, Associação Florestal de Vale do Sousa; CDP, Criterium DecisionPlus (Decision-support software); DSS, Decision Support System; FMM, Forest Management Model (stand-level management model); aFMM4, alternative Forest Management Model including Quercus suber L.; aFMM5, alternative Forest Management Model including Quercus robur L.; cFMM1, current Forest Management Model including Euclayptus globulus L.; cFMM2, current Forest Management Model including Pinus pinaster A.; cFMM3, current Forest Management Model including Castanea sativa M.; ICNF, Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas (Portuguese Forest Authority); LP, Linear Programming; MCDA, Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis; MU, Management Unit; ZIF, Zona de Intervenção Florestal.

References

1

Abate D. Botequim B. Marques S. Lagoa C. Hernández J. G. Hengeveld G. et al . (2025). Recreational and aesthetic values of forest landscapes (RAFL): quantifying management impacts and trade-offs with provisioning and regulatory ecosystem services. For. Ecosyst.13:100318. doi: 10.1016/j.fecs.2025.100318

2

Abate D. Marques S. Bushenkov V. Riffo J. Weintraub A. Constantino M. et al . (2024). Assessment of tradeoffs between ecosystem services in large spatially constrained forest management planning problems. Front. For. Glob. Change7:1368608.

3

Abelson E. S. Reynolds K. M. White A. M. Long J. W. Maxwell C. Manley P. N. (2021). Promoting long-term forest landscape resilience in the Lake Tahoe basin. bioRxiv 2021-06.

4

Abelson E. Reynolds K. White A. Long J. Maxwell C. Manley P. (2022). Evaluating pathways to social and ecological landscape resilience. Ecol. Soc.27:8.

5

Acosta M. Corral S. (2017). Multicriteria decision analysis and participatory decision support systems in forest management. Forests8:116. doi: 10.3390/f8040116

6

Ager A. A. Evers C. R. Day M. A. Alcasena F. J. Houtman R. (2021). Planning for future fire: scenario analysis of an accelerated fuel reduction plan for the western United States. Landsc. Urban Plann.215:104212. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104212

7

Agestam E. Wallertz K. Nilsson U. (2018). Alternative forest management models for ten case study areas in Europe (deliverable 1.2). ALTERFOR - alternative models and robust decision-making for future forest management. Available online at: https://alterfor-project.eu/files/alterfor/download/Results/D1.2._Alternative%20Forest%20Management%20Models%20for%20ten%20Case%20Study%20Areas%20in%20Europe.pdf (Accessed July 21, 2020)

8

Amiri N. Mohammadi Limaei S. (2024). Optimizing forest management: balancing environmental and economic goals using game theory and multi-objective approaches. Forests15:2044. doi: 10.3390/f15112044

9

Ananda J. (2007). Implementing participatory decision making in forest planning. Environmental management, 39, 534–544.

10

Barreiro S. Rua J. Tomé M. (2016). Standssim-md: a management driven forest simulator. For. Syst.25:eRC07-eRC07. doi: 10.5424/fs/2016252-08916

11

Başkent E. Z. Balci H. (2024). A priory allocation of ecosystem services to forest stands in a forest management context considering scientific suitability, stakeholder engagement and sustainability concept with multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) technique: a case study in Turkey. J. Environ. Manag.369:122230. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122230,

12

Baskent E. Z. Küçüker D. M. (2010). Incorporating water production and carbon sequestration into forest management planning: a case study in Yalnızçcam planning unit. For. Syst.19, 98–111. doi: 10.5424/fs/2010191-01171

13

Belton V. Stewart T. J. (2002). Multiple criteria decision analysis: An integrated approach. Springer.doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1495-4

14

Bettinger P. Boston K. Siry J. P. Grebner D. L. (2016). Forest management and planning. Cambridge: Academic Press, 141–161.

15

Blagojević B. Jonsson R. Björheden R. Nordström E. M. Lindroos O. (2019). Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) in forest operations–an introductional review. Croat. J. For. Eng. J. Theory Appl. For. Eng.40, 191–2015.

16

Borges J. G. Garcia-Gonzalo J. Bushenkov V. McDill M. E. Marques S. Oliveira M. M. (2014). Addressing multicriteria forest management with pareto frontier methods: an application in Portugal. For. Sci.60, 63–72. doi: 10.5849/forsci.12-100

17

Borges J. G. Marques S. Garcia-Gonzalo J. Rahman A. U. Bushenkov V. Sottomayor M. et al . (2017). A multiple criteria approach for negotiating ecosystem services supply targets and forest owners' programs. For. Sci.63, 49–61. doi: 10.5849/FS-2016-035

18

Botequim B. Bugalho M. N. Rodrigues A. R. Marques S. Marto M. Borges J. G. (2021). Combining tree species composition and understory coverage indicators with optimization techniques to address concerns with landscape-level biodiversity. Land10:126. doi: 10.3390/land10020126

19

Burkhart H. E. Tomé M. (2012). “Modeling response to silvicultural treatments” in Modeling forest trees and stands, eds. Burkhart, H. E., and Tomé, M. (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 363–403.

20

Cabral M. Fonseca T. F. Cerveira A. (2022). Optimization of forest management in large areas arising from grouping of several management bodies: an application in northern Portugal. Forests13:471. doi: 10.3390/f13030471

21

Çağlayan İ. Yeşil A. Kabak Ö. Bettinger P. (2021). A decision-making approach for assignment of ecosystem services to forest management units: a case study in Northwest Turkey. Ecol. Indic.121:107056. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107056

22

Casados S. M. Rodríguez-Fernández S. Marques S. Cuartas A. M. M. de Frutos S. Coll L. et al . (2025). A participatory multi-criteria approach to select areas for post-fire restoration after extreme wildfire events. Forests16:1090. doi: 10.3390/f16071090

23

Couture S. Cros M. J. Sabbadin R. (2021). Multi-objective sequential forest management under risk using a Markov decision process-pareto frontier approach. Environ. Model. Assess.26, 125–141. doi: 10.1007/s10666-020-09736-4

24

de Sousa Xavier A. M. Freitas M. D. B. C. de Sousa Fragoso R. M. (2015). Management of mediterranean forests—a compromise programming approach considering different stakeholders and different objectives. Forest Policy Econ.57, 38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2015.03.012

25

Díaz-Balteiro L. González-Pachón J. Romero C. (2009). Forest management with multiple criteria and multiple stakeholders: an application to two public forests in Spain. Scand. J. For. Res.24, 87–93. doi: 10.1080/02827580802687440

26

Diaz-Balteiro L. Romero C. (2008). Making forestry decisions with multiple criteria: a review and an assessment. For. Ecol. Manag.255, 3222–3241. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2008.01.038

27

Ferreira L. Constantino M. F. Borges J. G. Garcia-Gonzalo J. (2015). Addressing wildfire risk in a landscape-level scheduling model: an application in Portugal. For. Sci.61, 266–277. doi: 10.5849/forsci.13-104

28

Filipe A. F. L. (2019). Implementation of a growth model for chestnut in the StandsSIM.Md forest simulator (master’s thesis). Lisboa, Portugal: Universidade de Lisboa (in Portuguese).

29

Fiorentin L. D. Arce J. E. Pelissari A. L. David H. C. da Silva P. H. B. M. Stang M. B. et al . (2017). Strategies for regulating timber volume in forest stands. Sci. For.45, 717–726. doi: 10.18671/scifor.v45n116.12

30

Garcia-Gonzalo J. Borges J. G. (2019). Models and tools for integrated forest management and forest policy analysis: an editorial. Forest Policy Econ.103, 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2019.04.006

31

Garcia-Gonzalo J. Bushenkov V. McDill M. E. Borges J. G. (2014). A decision support system for assessing trade-offs between ecosystem management goals: an application in Portugal. Forests6, 65–87. doi: 10.3390/f6010065

32

Gómez-García E. Diéguez-Aranda U. Cunha M. Rodríguez-Soalleiro R. (2016). Comparison of harvest-related removal of aboveground biomass, carbon and nutrients in pedunculate oak stands and in fast-growing tree stands in NW Spain. For. Ecol. Manag.365, 119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.01.021

33

Gonzalez-Olabarria J. R. Reynolds K. M. Larrañaga A. Garcia-Gonzalo J. Busquets E. Pique M. (2019). Strategic and tactical planning to improve suppression efforts against large forest fires in the Catalonia region of Spain. Forest ecology and management432, 612–622.

34

Grazhdani D. (2024). Fuzzy analytical hierarchy process evaluation of stakeholder groups involvement in forest management situations. J. Environ. Manag. Tour.15, 435–448.

35

Gustafson E. J. Roberts L. J. Leefers L. A. (2006). Linking linear programming and spatial simulation models to predict landscape effects of forest management alternatives. J. Environ. Manag.81, 339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.11.009,

36

Huth A. Drechsler M. Köhler P. (2004). Multicriteria evaluation of simulated logging scenarios in a tropical rain forest. J. Environ. Manag.71, 321–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.03.008,

37

ICNF . (2013). IFN6-Áreas dos usos do solo e das espécies florestais de Portugal continental. Resultados preliminares (v1.0). Lisboa: ICNF. Available online at: https://www.scribd.com/document/125083449/IFN6-Result-Prelim-v1

38

ICNF. (2019). IFN6 – Principais resultados – relatório sumário (v 1.0). Lisboa: ICNF. Available online at:https://www.fc.up.pt/pessoas/mccunha/Silvicultura/Aulas/estatisticas/IFN6-Principais-resultados-Jun2019.pdf

39

Jamnick M. S. (1990). A comparison of FORMAN and linear programming approaches to timber harvest scheduling. Can. J. For. Res.20, 1351–1360. doi: 10.1139/x90-179

40

Johnson K. N. Scheurman H. L. (1977). Techniques for prescribing optimal timber harvest and investment under different objectives: Discussion and synthesis. Forest Science, 18, 31–42.

41

Kangas J. Kangas A. (2005). Multiple criteria decision support in forest management—the approach, methods applied, and experiences gained. For. Ecol. Manag.207, 133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2004.10.023

42

Kangas J. Store R. Leskinen P. Mehtätalo L. (2000). Improving the quality of landscape ecological forest planning by utilising advanced decision-support tools. For. Ecol. Manag.132, 157–171. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00221-2

43

Krsnik G. Reynolds K. M. Aquilué N. Mola-Yudego B. Pecurul-Botines M. Garcia-Gonzalo J. et al (2024a). Assessing the dynamics of forest ecosystem services to define forest use suitability: a case study of Pinus sylvestris in Spain. Environmental Sciences Europe36:128.

44

Krsnik G. Olivé E. B. Nicolau M. P. Larrañaga A. Terés J. Á. Garcia-Gonzalo J. et al . (2024b). Spatial multi-criteria analysis for prioritising forest management zones to prevent large forest fires in Catalonia (NE Spain). Environmental Challenges15: 100959.

45

Lakićević M. D. Reynolds K. M. Srđević B. M. (2019). Assessing landscape plans with abbreviated pair-wise comparisons in the AHP (Analitic Hierarchy Process). Zbornik Matice srpske za prirodne nauke, 136, 183–194.

46

Li M. Li H. Fu Q. Liu D. Yu L. Li T. (2021). Approach for optimizing the water-land-food-energy nexus in agroforestry systems under climate change. Agric. Syst.192:103201. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103201

47

Li Y. Abu Bakar N. A. Ismail N. A. Mohd Ariffin N. F. Mundher R. (2024). Stakeholder involvement and preferences in landscape protection decision-making: A systematic literature review. Front Commun.9:1340026.

48

Mardani A. Zavadskas E. K. Khalifah Z. Zakuan N. Jusoh A. Nor K. M. et al . (2017). A review of multi-criteria decision-making applications to solve energy management problems: two decades from 1995 to 2015. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.71, 216–256. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.053

49

Maroto C. Segura M. Ginestar C. Uriol J. Segura B. (2012). Aggregation of stakeholder preferences in sustainable Forest management using AHP. In ICORES. 100–107.

50

Marques S. Bushenkov V. A. Lotov A. V. Marto M. Borges J. G. (2020). Bi-level participatory forest management planning supported by pareto frontier visualization. For. Sci.66, 490–500. doi: 10.1093/forsci/fxz014

51

Marques M. Juerges N. Borges J. G. (2020a). Appraisal framework for actor interest and power analysis in forest management-insights from northern Portugal. For. Policy Econ.111:102049. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2019.102049

52

Marques M. Oliveira M. Borges J. G. (2020b). An approach to assess actors’ preferences and social learning to enhance participatory forest management planning. Trees For. People2:100026. doi: 10.1016/j.tfp.2020.100026

53

Marques M. Reynolds K. M. Marques S. Marto M. Paplanus S. Borges J. G. (2021a). A participatory and spatial multicriteria decision approach to prioritize the allocation of ecosystem services to management units. Land10:747. doi: 10.3390/land10070747

54

Marques M. Reynolds K. M. Marto M. Lakicevic M. Caldas C. Murphy P. J. et al . (2021b). Multicriteria decision analysis and group decision-making to select stand-level forest management models and support landscape-level collaborative planning. Forests12:399. doi: 10.3390/f12040399

55

Marques S. Rodrigues A. R. Paulo J. A. Botequim B. Borges J. G. (2024). Addressing carbon storage in forested landscape management planning—An optimization approach and application in Northwest Portugal. Forests15:408.

56

Martins M. D. B. Xavier A. Fragoso R. (2014). A bioeconomic forest management model for the Mediterranean forests: a multicriteria approach. J. Multicrit. Decis. Anal.21, 101–111. doi: 10.1002/mcda.1495

57

Maroto C. Segura M. Ginestar C. Uriol, J. Segura B. (2012). February). Aggregation of Stakeholder Preferences in Sustainable Forest Management using AHP. In ICORES, 100–107.

58

Marto M. Reynolds K. M. Borges J. G. Bushenkov V. A. Marques S. (2018). Combining decision support approaches for optimizing the selection of bundles of ecosystem services. Forests9:438. doi: 10.3390/f9070438

59

Mendoza G. A. Martins H. (2006). Multi-criteria decision analysis in natural resource management: a critical review of methods and new modelling paradigms. For. Ecol. Manag.230, 1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2006.03.023

60

Mohammadi Z. Limaei S. M. Shahraji T. R. (2017). Linear programming approach for optimal forest plantation. J. For. Res.28, 299–307. doi: 10.1007/s11676-016-0318-y

61

Murphy P. J. (2014). “Criterium DecisionPlus” in Making transparent environmental management decisions: applications of the ecosystem management decision support system. eds. BourgeronP. S.HessburgP. F.ReynoldsK. M. (Berlin: Springer), 35–60.

62

Nordén A. Coria J. Jönsson A. M. Lagergren F. Lehsten V. (2017). Divergence in stakeholders' preferences: evidence from a choice experiment on forest landscapes preferences in Sweden. Ecol. Econ.132, 179–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.09.032

63

Nordström E. M. Eriksson L. O. Öhman K. (2010). Integrating multiple criteria decision analysis in participatory forest planning: experience from a case study in northern Sweden. For. Policy Econ.12, 562–574. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2010.07.006

64

Nordström E. M. Holmström H. Öhman K. (2013). Evaluating continuous cover forestry based on the forest owner’s objectives by combining scenario analysis and multiple criteria decision analysis. Silva Fenn.47. doi: 10.14214/sf.1046

65

Novais A. Canadas M. J. (2010). Understanding the management logic of private forest owners: a new approach. Forest Policy Econ.12, 173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2009.09.010

66

Nunes L. J. R. Meireles C. I. R. Pinto Gomes C. J. de Almeida Ribeiro N. M. C. (2019). Socioeconomic aspects of the forests in Portugal: recent evolution and perspectives of sustainability of the resource. Forests10:361. doi: 10.3390/f10050361

67

Ortiz-Urbina E. Diaz-Balteiro L. Pardos M. González-Pachón J. (2022). Representative group decision-making in forest management: a compromise approach. Forests13:606. doi: 10.3390/f13040606

68

Palaiologou P. Kalabokidis K. Ager A. A. Day M. A. (2020). Development of comprehensive fuel management strategies for reducing wildfire risk in Greece. Forests11:789. doi: 10.3390/f11080789

69

Patrício M. S. (2006). Analysis of the productive potential of chestnut in Portugal (Ph.D. thesis). Lisboa, Portugal: Universidade Técnica de Lisboa (in Portuguese).

70

Paulo J. A. Tomé J. Tomé M. (2011). Nonlinear fixed and random generalized height–diameter models for Portuguese cork oak stands. Ann. For. Sci.68, 295–309. doi: 10.1007/s13595-011-0041-y

71

Pra A. Masiero M. Barreiro S. Tomé M. De Arano I. M. Orradre G. et al . (2019). Forest plantations in southwestern Europe: a comparative trend analysis on investment returns, markets and policies. For. Policy Econ.109:102000. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2019.102000

72

Regan H. M. Colyvan M. Markovchick-Nicholls L. (2006). A formal model for consensus and negotiation in environmental management. J. Environ. Manag.80, 167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.09.004,

73

Renard K. G. Foster G. R. Weesies G. A. Porter J. P. (1991). RUSLE: revised universal soil loss equation. Soil Water Conserv.46, 30–33.

74

Rodrigues A. R. Marques S. Botequim B. Marto M. Borges J. G. (2021). Forest management for optimizing soil protection: a landscape-level approach. For. Ecosyst.8, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40663-021-00324-w,

75

Rodríguez-Fernández S. Murphy P. J. Reynolds K. M. Poudel S. Borges J. G. González-Olabarria J. R. (2025). Participatory multi-criteria decision analysis to prioritize management areas that help suppress wildfires. Front. For. Glob. Change8:1654107. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2025.1654107

76

Saaty T. L. (1990). How to make a decision: the analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res.48, 9–26. doi: 10.1016/0377-2217(90)90057-I

77

Saaty T. L. (1996). Multicriteria decision making: the analytic hierarchy process. Pittsburg: RWS Publications.

78

Seely B. Nelson J. Wells R. Peter B. Meitner M. Anderson A. et al . (2004). The application of a hierarchical, decision-support system to evaluate multi-objective forest management strategies: a case study in northeastern British Columbia, Canada. For. Ecol. Manag.199, 283–305. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2004.05.048

79

Stenger A. Harou P. Navrud S. (2009). Valuing environmental goods and services derived from the forests. J. For. Econ.15, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jfe.2008.03.001

80

Tóth S. F. McDill M. E. (2009). Finding efficient harvest schedules under three conflicting objectives. For. Sci.55, 117–131. doi: 10.1093/forestscience/55.2.117

81

Uhde B. Andreas Hahn W. Griess V. C. Knoke T. (2015). Hybrid MCDA methods to integrate multiple ecosystem services in forest management planning: a critical review. Environ. Manag.56, 373–388. doi: 10.1007/s00267-015-0503-3,

82

Varma V. K. Ferguson I. Wild I. (2000). Decision support system for the sustainable forest management. For. Ecol. Manag.128, 49–55. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00271-6

83

Weintraub A. Romero C. (2006). Operations research models and the management of agricultural and forestry resources: a review and comparison. Interfaces36, 446–457. doi: 10.1287/inte.1060.0222,

Summary

Keywords

forest decision support systems, participatory modeling, strategic forest planning, optimization-based evaluation, analytical hierarchy process, multi-criteria decision analysis

Citation

Poudel S, Rodríguez-Fernández S, Reynolds KM and Marques S (2026) Ranking landscape-level management planning scenarios based on stakeholders’ interests and ecosystem services performance. Front. For. Glob. Change 8:1707550. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2025.1707550

Received

17 September 2025

Revised

15 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

07 January 2026

Volume

8 - 2025

Edited by

Yashwant Singh Rawat, Federal Technical and Vocational Education and Training Institute (FTVETI), Ethiopia

Reviewed by

Nataliya Stryamets, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Sweden

Patrice Kpadé, Universite du Quebec en Abitibi-Temiscamingue Unite de recherche et de developpement en agroalimentaire en Abitibi-Temiscamingue, Canada

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Poudel, Rodríguez-Fernández, Reynolds and Marques.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Srijana Poudel, srijanapoudel@isa.ulisboa.pt; poudel.srijana11@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.