Abstract

Soil scarification, which involves the disruption of the top layer of soil, is a common method utilized to promote the regeneration of tree species on clear-cut and calamity areas. In the context of adapting forests to become climate-resilient mixed species forests, this method could also be used to promote tree regeneration under intact canopies, either exclusively or in combination with direct seeding. However, evidence on the impact of this method on the composition of forest floor vegetation, including bryophytes, is lacking and needs to be investigated. This is of importance because the forest floor vegetation significantly contributes to species richness in temperate forests. To address how and to what extent soil scarification affects the forest floor species composition, we conducted a space-for-time-substitution study, creating a chronosequence spanning a 13-year period, to investigate the effect of soil scarification on forest floor vegetation in Norway spruce (Picea abies) stands in a lower montane forest in central Germany. Our results showed that soil scarifications were quickly recolonized by bryophyte species, whereas herbaceous species cover took around a decade to reach a similar level of establishment as the undisturbed forest floor. Species composition initially shifted in favor of early successional species. In the long term, however, the species composition converged back to the undisturbed state. Tree regeneration diversity especially benefitted from scarification, making it a viable method for intact forest stands, particularly given that it does not appear to exert any adverse effect on forest floor vegetation.

1 Introduction

Soil scarification involves the disruption of the uppermost soil layer, thereby creating a more uneven surface and exposing the mineral soil through manual or mechanical means. It is a long-standing practice in forest management, where it is used to enhance reforestation. The combination of several advantageous factors has been demonstrated to improve microsite conditions for the establishment of trees. These factors include reduced competition for resources for the desired tree species (Nilsson and Örlander, 1999; Karlsson et al., 2002), increased nutrient mineralization rates (Stenger et al., 1995; Kristensen et al., 2000), and increased soil water availability and soil temperatures (Johansson et al., 2005; Hansson et al., 2018). Scarification is often used in conjunction with direct seeding as a soil preparation method before sowing (Grossnickle and Ivetić, 2017). This alternative to tree plantings is increasingly employed by forest management in central Europe for artificial regeneration and the introduction of new or underrepresented tree species to increase the climate-resilience of forests (Huth et al., 2017; Löf et al., 2019; Pardos et al., 2021).

The application of direct seeding has been examined for various tree species in temperate European forests (Ammer et al., 2002; Huth et al., 2017; Löf et al., 2019; Willoughby et al., 2019). Similarly, the positive effects of soil scarification on the regeneration of various tree species have been investigated (Karlsson et al., 2002; Dassot and Collet, 2015; Fløistad et al., 2018). However, the consequences for herbaceous and bryophyte species have received comparatively less attention. In temperate forests, the herbaceous and bryophyte layers exhibit the highest biodiversity among the various strata and deliver a substantial variety of environmental services (Gilliam, 2007; Eldridge et al., 2023). In the context of reforestation and adaptation to climate change, the herb and bryophyte layers play a particularly important role in the water and nutrient cycle (Porada et al., 2018; Thrippleton et al., 2016; Thrippleton et al., 2018). Consequently, it is crucial to examine the effect of small-scale disturbances, such as scarification, on the composition and structure of these ecosystem compartments.

Several studies have examined the effects of scarification on the biodiversity of herbaceous and bryophyte species in clear-cut and shelterwood cutting areas (Pykälä, 2004; Bergstedt et al., 2008; Hébert et al., 2016; Tullus et al., 2019). These studies suggest that scarification has the capability to alter the species distribution in these ecosystems, by disrupting the existing dominant vegetation and humus layer, allowing other species the opportunity to colonize these newly established microsites. In such rather open environments, scarification often results in the proliferation of ruderal, fast-growing and highly competitive species, which can lead to a long-term decline in overall species richness (Bergstedt et al., 2008). Still, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the effects of scarification on the species composition and cover of herbaceous and bryophyte vegetation under an intact canopy. Assessing these effects is important considering the increasing need for artificial rejuvenation within closed forest stands.

With scarification increasingly applied for this purpose, it is crucial to understand the recolonization dynamics of herbaceous and bryophyte vegetation in terms of cover development and species composition to evaluate potential impacts. However, medium- to long-term observation sites in commercially used forests employing these techniques are scarce, making such observations challenging. In order to still infer temporal vegetation cover development, a space-for-time substitution approach was employed to investigate these dynamics. This approach entails the substitution of long-term monitoring of disturbed sites with the investigation of geographically separated sites with disturbances from different years within the same forest area. Thus, a 13-year chronosequence (2011–2023) was created to evaluate the progression of cover development and species composition in a lower montane acidophilous conifer forest in central Germany dominated by Norway spruce (Picea abies H.Karst.). As the herbaceous and bryophyte species composition of temperate forests is largely driven by microsite environmental characteristics, additional measurements were taken to assess microclimatic conditions, including light availability, soil moisture, and topographic features (Gilliam, 2007; Müller et al., 2019; Tinya et al., 2009). The objective of this study was to address the following research questions:

-

How long after scarification for direct seeding does it take for herbaceous and bryophyte cover to fully enclose the disturbance?

-

Does scarification facilitate the establishment of species that contribute minimally or not at all to the cover of the undisturbed forest floor, thereby changing the species composition?

-

Which environmental factors mediate establishment and species composition after scarification, and are these factors general or species-specific?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study site and design

The study was conducted in southern Thuringia, Germany, in the Hildburghausen municipal forest (50°27’N 10°47′E). The forest’s topography ranges from 430 to 565 m a.s.l. with mainly south-facing slopes. The forest’s soil, predominantly brown and podzolized brown soils, is characterized by acidic ≈ pH 3 (measured in KCl) and nutrient-poor soil conditions due to its underlying bedrock (Bundsandstone) and the historical forest use, causing additional nutrient removal through litter and firewood collection (TLUBN, 2024). The mean annual temperature is 8.5 °C, and the mean annual precipitation is 800 mm (DWD weather station Veilsdorf). The forest, primarily managed for timber production, is largely comprised of conifers, accounting for 86% of the stand volume. Of these P. abies makes up 64%, along with smaller amounts of Pinus sylvestris L. and Betula pendula Roth. Since 2011, the municipal forestry service has employed direct seeding in conjunction with soil scarification as a strategy to transform predominantly single-species stands into multi-species, uneven-aged ones. A key aspect of this strategy has been the reintroduction of Abies alba Mill., a conifer species considered as exhibiting greater adaptation potential to climate change compared to P. abies (Vitasse et al., 2019).

The comparable long-standing practice of direct seeding in this forest allows for the survey of artificial rejuvenation sites from up to 13 years ago (2011–2023). A space-for-time approach was adopted to evaluate the impact of scarification through continuous line disk trenching on the forest floor vegetation for more than one decade. To create a comprehensive chronosequence of the development of the herbaceous and bryophyte layer after scarification, a series of survey sites was established. To include soil water characteristics in the site selection, as it potentially affects species composition, larger-scale hydrology was considered in the site pre-selection process. Before in situ selection, potential sites were evaluated based on the available data on the water balance classes derived from the forest site mapping of Thuringia (FFK Gotha, 2022), using QGIS (v3.24) (QGIS Development Team, 2022). These classes provide a rough estimate of the water availability and are based on the usable field capacity and topographic features that determine aspects such as water table height and potential duration of waterlogging. The aim was to pre-select sites within one year with the most contrasting water balance classes available (e.g., moderately wet vs. moderately dry) to incorporate a higher heterogeneity of general water availability. After the preselection process, the forest sites underwent in situ evaluation. The evaluation parameters included site size with a minimum of 0.25 ha and the availability and identifiability of seeding rows. Based on the aforementioned criteria, two sites per year were selected, with the exception of 2016 and 2017, were only one site was available each, and 2015 and 2022, during which no sowing took place. If more than two sites were suitable based on the aforementioned criteria, the sites of the most contrasting water balance classes were chosen, and in cases of no difference between these classes, the larger site was selected. This resulted in a total of 20 sites, representing 11 years of the 13-year chronosequence. As the aim was to select sites with an intact canopy, it is to note that over the course of the sampling year, four sites saw their canopy partially removed due to bark beetle (Ips typographus) salvage logging, while others saw changes in the canopy cover of adjacent sites.

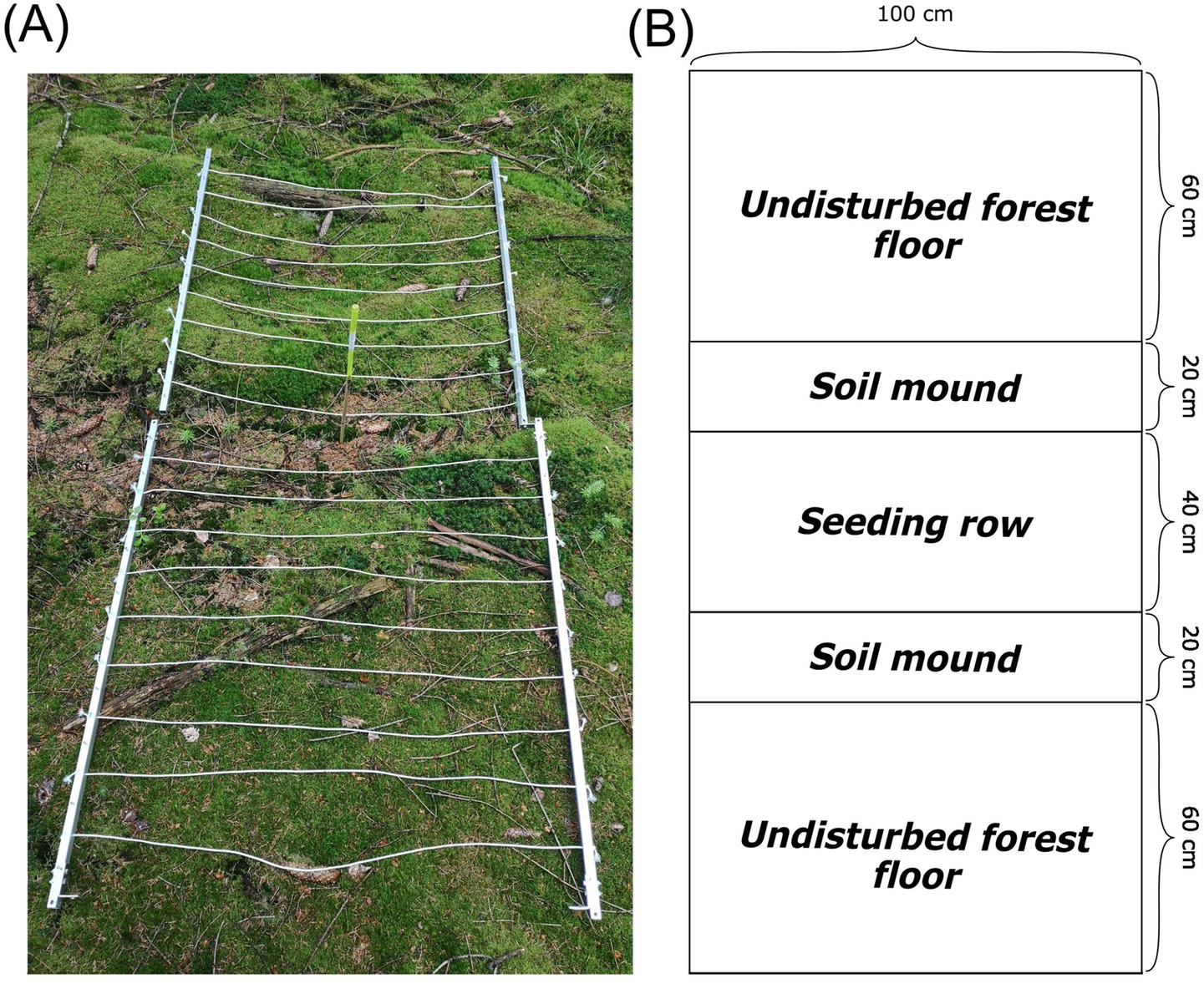

At each site, 10 survey plots (n = 200) were distributed along the longest possible diagonal within-site to account for site heterogeneity. In instances where the positioning of the plots along a single diagonal was not viable due to inadequate distance (< 5 m) between plots, a secondary diagonal, perpendicular and overlapping the first one, was used to further distribute the plots. In general, plots were established with a distance of 15 m between them, with the distance varying on average by ±2 m due to the distance between seeding rows. The survey plots were established on the seeding rows. They extended one meter outward from the seeding row in both directions and one meter along the seed row, resulting in a 2×1 m plot (Figure 1). The plots were then subdivided into three subsections: a 40-centimeter-wide seed row whose width was predetermined by the disc trenching tool used; two 20-centimeter-wide mounds (40 cm total) whose total width was the same as the seeding row as they were comprised of the displaced soil from the disc trenching; and two 60-centimeter-wide strips of undisturbed forest floor (120 cm total, hereafter referred to as “forest floor”) (Figure 1). The larger width of the forest floor subplot was intentionally chosen to be wider compared to the other two, in order to potentially record a larger pool of species, allowing us to better trace whether species recolonized the disturbance out of the proximity of the seeding row or from further away. Due to the generally species-poor conditions of the surveyed forest, this greater width increased the probability of detecting said species. Since we used vegetation layer and species cover percentage as the main variables of the statistical analysis, which are area unspecific, we believe that no bias was introduced to the analysis of the total cover of the herbaceous and bryophyte layer, despite this uneven design. The chosen uneven design could potentially have affected the selection of the species considered for species-specific testing by increasing the likeliness of detection due to the larger area covered. While in situ observations did confirm the chosen most common species to be a sound selection, this selection bias can’t be fully ruled out. The same potential bias also applies to the indicator species analysis. The vegetation inventory was performed from 27.05.2024 to 05.06.2024, surveying the bryophyte, herbaceous (< 1.5 m), shrub (1.5–6 m), and tree layer. Vegetation cover within the plots was estimated using a slightly modified scale by Pfadenhauer et al. (1986): r (one Individual), + (<1%), 1a (1–3%), 1b (4–5%), 2a (5–10%), 2b (10–25%), 3 (25–50%), 4 (50–75%), and 5 (75–100%). General cover of each vegetation layer was estimated on the plot level, and species-specific cover by subplots. The mean value of these cover classes was used as the basis for the subsequent analysis. Species nomenclature was used according to Euro+Med PlantBase (2025).

Figure 1

(A) Example of a survey plot (6 years since scarification) and (B) schematic representation of the survey plot design used during the vegetation survey.

The soil moisture content was measured in each plot using an FDR probe (ML3-Theta probe) connected to a HH2 moisture meter (Delta-T Devices Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Three measurements were taken in the mineral soil at a depth of 6 cm, along a 40 cm line covering all three subplots. The measurements were then averaged to obtain a single measurement, representing a snapshot of each plot’s microsite conditions. The measurements took place on the 04.08.24, four days after a rain event (Table 1). Photosynthetically active radiation was measured simultaneously with the soil moisture, in the center of the seeding row and on both sides in the center of the forest floor subplot at a height of one meter using a LI-COR LI-190R quantum sensor coupled to a Li-COR LI-1500 light sensor logger. Three measurements were obtained and averaged (Table 1). Open field reference values were obtained from adjacent calamity areas within the forest. Due to the weather prerequisites of a rain event followed by dry days and uniformly overcast skies, the measurements could not be obtained right after the vegetation survey. However, as no change to the overstory occurred during this time period, we believe no bias was introduced by this delay. The digital elevation model (DEM10 1x1m Grid) of Thuringia (GDI-Th, 2025) was used to determine plot aspect using QGIS. Additionally, the topographic wetness index (TWI) was calculated for each plot. The index describes an estimate of the likelihood of water accumulation within a specified area (grid cells) and is calculated as:

Where α describes the catchment area and β the slope (Beven and Kirkby, 1979). TWI values were derived from the DEM using SAGA GIS (Conrad et al., 2015) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variable | Abbreviation | Unit | Description | Min. | Mean | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation cover | % | Normalized ratio of variable (Fv) to maximum fluorescence (Fm) | ||||

| Soil moisture | SWC | vol % | Averaged soil moisture content based on three single measurements per plot | 13.80 | 27.18 | 59.43 |

| Topographic wetness index | TWI | Index estimating the likelyhood of water accumulation based on the terrains slope derived from the DEM | 1.81 | 3.62 | 6.12 | |

| Photosynthetically active radiation | PAR | % | Percentage of photosynthetically active radiation within the forest stands, referenced to an open site measurement | 10.54 | 43.31 | 100 |

| Aspect | Degree ° | 8.46 | 159.37 | 355.42 |

The surveyed environmental variables with abbreviations, units, and a brief description.

2.2 Statistical analysis

The development of the overall cover over time, including all species, was analyzed using Generalized Additive Models (GAM) (Hastie and Tibshirani, 2017), with separate analyses conducted for the herbaceous and the bryophyte layer. GAMs were used for the modeling of cover development as they allow to account for the expected, non-linear cover development over time, caused by differences in species distribution speed and growth. To minimize the influence of overall cover differences between the plots on the model, the log ratio of the difference between the forest floor and the seeding row and the soil mounds was calculated as:

This allowed for a simplified interpretation of the seeding row and mounds cover, as negative log ratios indicate lower cover in the scarification area compared to the forest floor, while positive values indicate higher cover. Zero represents no cover changes. Before calculating the log ratio, a pseudo count of 10−6 was added to all cover values to avoid infinity issues when the cover value equaled zero. This approach enabled the retention of all plots for analysis. Subsequently, the log ratio was modeled as the dependent variable and the two scarification subplot types as explanatory variables, with zero as a fixed intercept and the years since scarification as a smoothing term using thin plate regression splines with 4 basis functions (cover log ratio ~ 0 + subplot type + s(years_since)). Zero was used as a fixed intercept to allow for the comparison of the scarification subplots to the forest floor baseline. To account for the nesting of the subplots within the plots, both plot and subplot were included as random factors in the model. Model fitting was done using the Student’s t distribution with an identity link to account for the data structure and improved handling of extreme observations. Model robustness was assessed using visual diagnostic tests. Post hoc analysis of the fitted models was performed using estimated marginal means (EMMs). Contrasts were calculated for each individual year, testing log-ratio cover values of the seeding row and soil mound for significant differences toward zero.

In the GAM analysis of total cover exclusively, the cover of A. alba, as the target species of the direct seeding operations, was excluded from the seeding rows and mounds, as the focus of the study was on the naturally occurring species. However, A. alba was sporadically present within the canopy of forest sites adjacent to the survey sites and naturally regenerating, leading to the assumption that all individuals on the forest floor originated from natural regeneration. Consequently, the presence of A. alba cover within the forest floor was documented (in total, 10 out of 200 plots exhibited A. alba presence on the forest floor). While it’s possible that seeds were transported by animals from the seeding rows onto the forest floor, the presence of fruiting A. alba stands near the excluded plots suggests that the seeds are falling directly to the forest floor. This is supported by observing the age differences between the seedlings in the seeding rows and those on the forest floor. While this also poses the potential of individuals in the seeding row originating from this seed rain, the age difference between individuals in the seeding row and those on the forest floor, combined with the very low number of individuals observed outside the row, makes this highly unlikely. In subsequent species-specific modeling, A. alba was included, serving as a reference for the development as the direct seeding target species.

To identify species that could serve as potential indicators of different stages of development after scarification, we divided the timeline into three phases. The initial phase: the “pioneer” phase, comprises the first four years after scarification (including year 2 for which no sites were available). The second phase: the “intermediate” phase, lasts from years five to eight. Year 9 was left out as no sites from this year were available, and it was situated between the four-year brackets. The third phase: the “climax” phase, consists of the final four years of the observed timespan. This division was based on the results of the analysis of overall cover development. An indicator species analysis (ISA) was conducted for each subplot individually.

In addition to examining overall cover development, we analyzed species-specific cover for the 24 most abundant species with more than 20 observations. This threshold was selected to maintain sufficient statistical power for the models and because the number of observations below this value declined strongly, compromising the reliability and interpretability of statistical results. These species were categorized into three groups: tree regeneration, herbaceous plants, and bryophytes. For the tree regeneration, the cover values from individuals recorded in the shrub layer were added to those in the herbaceous layer using the following formula by Fischer (2015) to account for potential overlaps:

This was done to include tree seedlings in the seeding rows and mounds that originated from natural regeneration, which however, had grown beyond the height threshold of the herbaceous layer. This was specifically the case for A. alba, B. pendula, P. abies, and P. sylvestris. Later, in the model selection, the shrub layer cover was not considered for the four aforementioned species to not include these values twice. Species-specific cover development over time was also analyzed via GAMs. The same GAM-model structure as for overall cover development was used.

To explore species assemblage in relation to the different subplot types and environmental factors, a Distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) was used, where years since scarification was used as the constraining factor. Only factors that exhibited significant correlations were retained for further analysis. The dbRDA was performed using the cover values of all recorded species.

The influence of environmental factors on cover development was also analyzed using GAMs. To identify the most influential environmental factors (Table 1) for each species, a model selection process was conducted to arrive at the most parsimonious model. Prior to model selection, environmental factors were tested for correlations. Tree layer cover and PAR were found to be highly correlated (−0.6). As both variables in this case carry similar information, only PAR was retained for offering a finer data gradient. In the further selection process, all possible combinations of non-correlated explanatory variables were fitted and comparatively evaluated based on their AIC values. Environmental factors were scaled to a zero-mean, unit-variance. The final model contained all the environmental factors as explanatory variables from the models with a ΔAIC < 2.

All statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.4.1 (R Core Team, 2024) using the mgcv package (Wood, 2017) for GAM modelling. Post hoc analysis of the GAMs was performed using the emmeans package (Lenth and Piaskowski, 2025). The vegan package (Oksanen et al., 2025) was used for the ordination and the indicspecies package (de Cáceres and Legendre, 2009) for the indicator species analysis. The package tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019) was used for general coding and plotting.

3 Results

A total of 84 species were documented within the survey plots, including 57 phanerogams (29 herbs, 13 grasses, and 15 trees) and 27 cryptogams (25 mosses and 2 ferns).

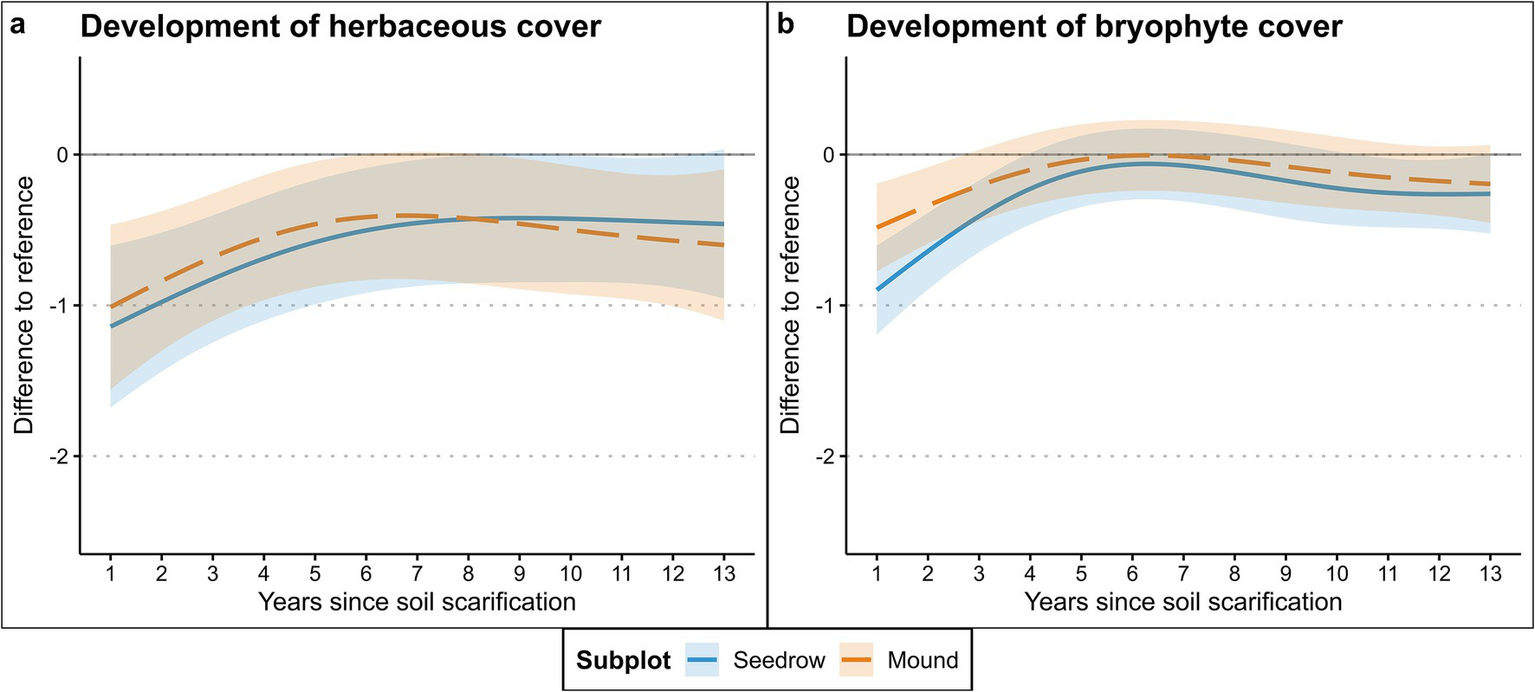

3.1 Cover development over time

In general, both herbaceous and bryophyte cover in the seeding rows and on the soil mounds appeared to differ significantly from the forest floor. However, the models only explained 1.79 and 7.2% of the variance within and between years (Table 2), respectively. This indicates that the development of cover was influenced by factors other than time alone (Table 2). Post-hoc analysis of the modeled herbaceous cover revealed a consistent increase in cover within the seeding rows over time. By the tenth year following scarification, the cover exhibited no significant difference compared to the forest floor, tough differences became significant again in year eleven and twelve (Figure 2a; Appendix 1). The herbaceous layer on the soil mounds showed a faster development compared to the seeding row, as differences to the forest floor disappeared by year six (Figure 2a; Appendix 1). However, starting by year ten differences reappeared with significantly lower cover on the soil mounds. Bryophyte cover increased comparatively faster, with differences toward the forest floor disappearing for both seeding row and mounds by year four (Figure 2b; Appendix 2). Afterwards, values slightly decreased, with cover in the seeding rows becoming significantly lower compared to the forest floor by year eleven and twelve, though by year thirteen the differences again subsided (Figure 2b; Appendix 2).

Table 2

| Layer | Treatment | Estimate | Std. error | T-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herbaceous | Deviance explained = 1.79% | ||||

| Seeding row | −0.595 | 0.192 | −3.103 | 0.002 | |

| Mound | −0.574 | 0.192 | −2.994 | 0.003 | |

| Bryophyte | Deviance explained = 7.2% | ||||

| Seeding row | −0.281 | 0.109 | −2.570 | 0.01 | |

| Mound | −0.150 | 0.109 | −1.376 | 0.169 | |

Summary statistics of the generalized additive models (GAM) of herbaceous and terricolous bryophyte cover.

Bold numbers indicate significance (α < 0.05).

Figure 2

Cover development of the (a) herbaceous vegetation and (b) terricolous bryophytes after soil scarification modeled via GAMs (Table 2). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence interval.

3.2 Indicator species

Of the 84 species, in total, twenty species were identified as indicators across all subplots and developmental phases (Table 3). In the pioneer phase (1–4 years following scarification), Dicranella heteromalla and Digitalis purpurea were both identified as indicator species within the seeding rows and mounds, while Carex pilulifera and Impatiens parviflora were identified as additional indicator species of the seeding rows. Thus, acrocarpous mosses and hemicryptophytes were the predominant life forms in these subplot types regarding indicator species. On the forest floor, Rubus idaeus and Epilobium angustifolium were identified as indicators. In the intermediate phase (5–8 years since scarification), the identified indicator species overlapped among all subplot types, including Taraxacum sect. Ruderalia as a shared indicator between the seeding row and forest floor (Table 3). Eurhynchium angustirete was a shared indicator species between the seeding rows and the mounds, while Melampyrum sylvaticum was a prevalent indicator species between the mounds and the forest floor. During the climax phase (10–13 years following scarification), the indicator species exhibited a persistent increase in similarity between subplots (Table 3). Leucobryum glaucum and Eurhynchium striatum were identified in all three subplot types. A greater number of tree species were identified as indicators here, including Quercus petraea and Pinus sylvestris, which served as indicators for the seeding rows and the forest floor. Bazzania trilobata was the sole liverwort species identified as an indicator in both mounds and the forest floor. In this development phase, pleurocarpous mosses and phanerophytes were the most dominant life form types. In addition to the identified indicator species, an average of six species unique to the scarification subplots were found within the first 10 years after the scarification; however, the number of individuals was low. During this timeframe, 12 herbaceous species were identified as being unique to the disturbance, however, no terricolous bryophytes were observed (Supplementary Materials).

Table 3

| Subplot | Species | Development phase | Stat | p-value | Lifeform type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seeding row | Dicranella heteromalla | Pioneer | 0.737 | 0.001 | Acrocarpous moss |

| Carex pilulifera | Pioneer | 0.51 | 0.001 | Perennial hemicryptophyte | |

| Digitalis purpurea | Pioneer | 0.365 | 0.001 | Monocarpic hemicryptophyte | |

| Impatiens parviflora | Pioneer | 0.224 | 0.05 | Therophyte | |

| Eurhynchium angustirete | Intermediate | 0.282 | 0.031 | Pleurocarpous moss | |

| Taraxacum sect. Ruderalia | Intermediate | 0.258 | 0.014 | Perennial hemicryptophyte | |

| Betula pubescens | Intermediate | 0.224 | 0.042 | Phanerophyte | |

| Leucobryum glaucum | Climax | 0.482 | 0.001 | Acrocarpous moss | |

| Pinus sylvestris | Climax | 0.352 | 0.011 | Phanerophyte | |

| Eurhynchium striatum | Climax | 0.333 | 0.015 | Pleurocarpous moss | |

| Quercus petraea | Climax | 0.291 | 0.013 | Phanerophyte | |

| Quercus robur | Climax | 0.274 | 0.043 | Phanerophyte | |

| Mound | Dicranella heteromalla | Pioneer | 0.71 | 0.001 | Acrocarpous moss |

| Digitalis purpurea | Pioneer | 0.258 | 0.013 | Monocarpic hemicryptophyte | |

| Melampyrum sylvaticum | Intermediate | 0.338 | 0.005 | Therophyte | |

| Eurhynchium angustirete | Intermediate | 0.288 | 0.004 | Pleurocarpous moss | |

| Mycelis muralis | Intermediate | 0.253 | 0.04 | Perennial hemicryptophyte | |

| Pseudotsuga_menziesii | Intermediate | 0.224 | 0.041 | Phanerophyte | |

| Leucobryum glaucum | Climax | 0.544 | 0.001 | Acrocarpous moss | |

| Eurhynchium striatum | Climax | 0.316 | 0.008 | Pleurocarpous moss | |

| Bazzania trilobata | Climax | 0.25 | 0.03 | Jungermanniales liverwort | |

| Hypnum cupressiforme var. filiforme | Climax | 0.224 | 0.031 | Pleurocarpous moss | |

| Forest floor | Rubus idaeus | Pioneer | 0.36 | 0.003 | Nanophanerophyte |

| Epilobium angustifolium | Pioneer | 0.258 | 0.016 | Perennial hemicryptophyte | |

| Melampyrum sylvaticum | Intermediate | 0.32 | 0.012 | Therophyte | |

| Frangula alnus | Intermediate | 0.258 | 0.019 | Phanerophyte | |

| Taraxacum sect. Ruderalia | Intermediate | 0.224 | 0.045 | Perennial hemicryptophyte | |

| Leucobryum glaucum | Climax | 0.601 | 0.001 | Acrocarpous moss | |

| Pinus sylvestris | Climax | 0.412 | 0.001 | Phanerophyte | |

| Eurhynchium striatum | Climax | 0.332 | 0.004 | Pleurocarpous moss | |

| Quercus petraea | Climax | 0.327 | 0.014 | Phanerophyte | |

| Bazzania trilobata | Climax | 0.243 | 0.043 | Jungermanniales liverwort | |

| Hypnum cupressiforme var. filiforme | Climax | 0.224 | 0.035 | Pleurocarpous moss |

Indicator species divided into the three subplots and development phases.

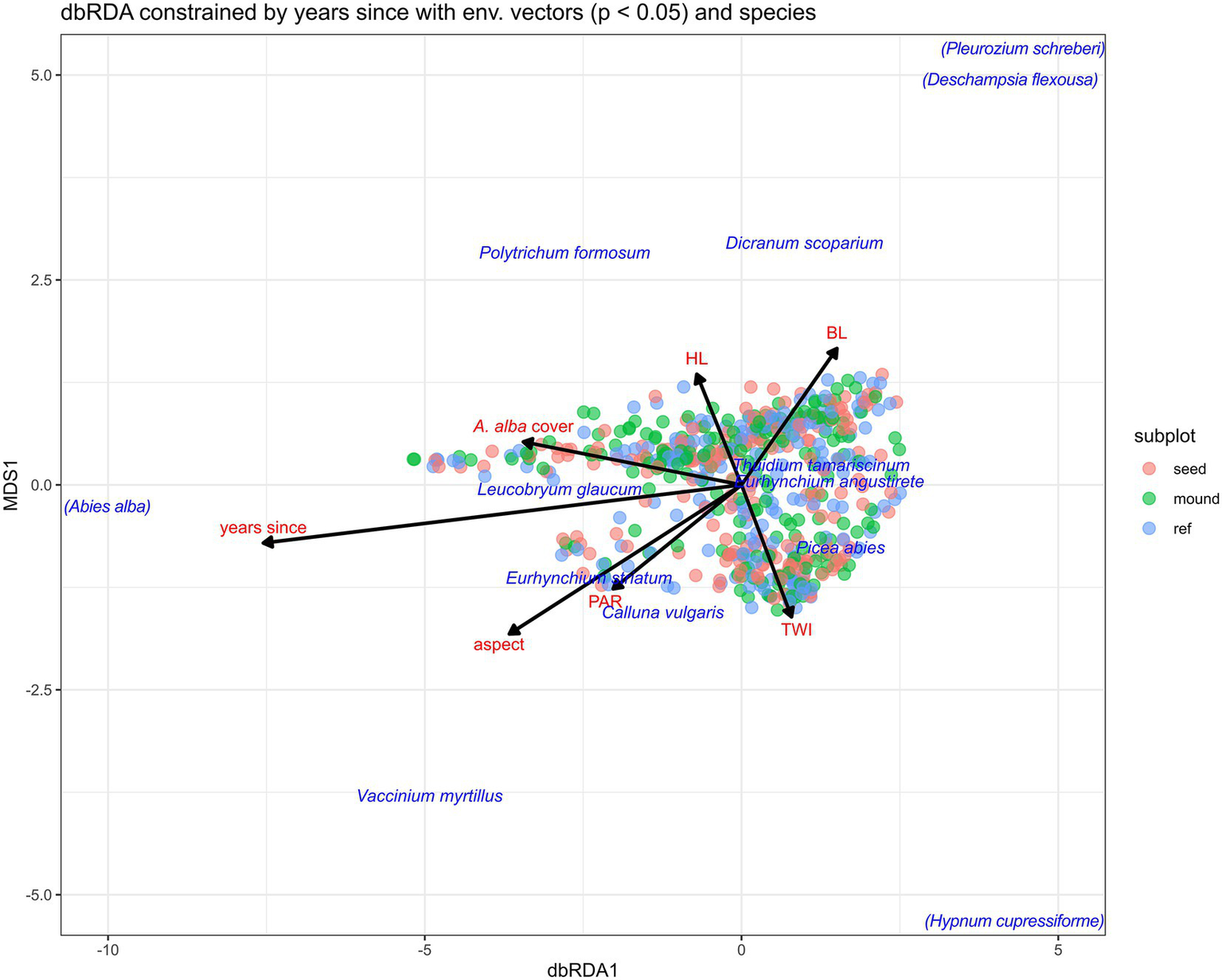

3.3 Ordination

The first axis (eigenvalue 4.768) of the dbRDA, constrained by the years since scarification, explained only 2.5% of the variation showing that time since scarification only had a minor influence. The second, unconstrained axis (eigenvalue 38.1663) explained 20.2% of the variation with herbaceous and bryophyte cover as well as TWI showing the stronger differentiation along the measured environmental factors. Permutation testing confirmed the significance of the model (p = 0.001). This result was to be expected due to the homogenous species composition throughout the survey sites. No distinct clustering of the subplot types (seeding row, soil mounds, and forest floor) was observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Ordination of environmental vectors (BL = bryophyte cover; HL = herbaceous cover) (Appendix 3) with a p < 0.05 in relation to the 24 most abundant species and the 200 surveyed plots constrained by the years since scarification. Eigenvalue of first, constrained axis 4.768, explaining 2.36% of the total variance of the data. Eigenvalue of second, unconstrained axis 38.1663, explaining 20.2% of the total variance. Only species with a distance >1 on Axis 1 shown. Species in brackets had their distance reduced to 1/3 of the original to improve plot comprehensibility.

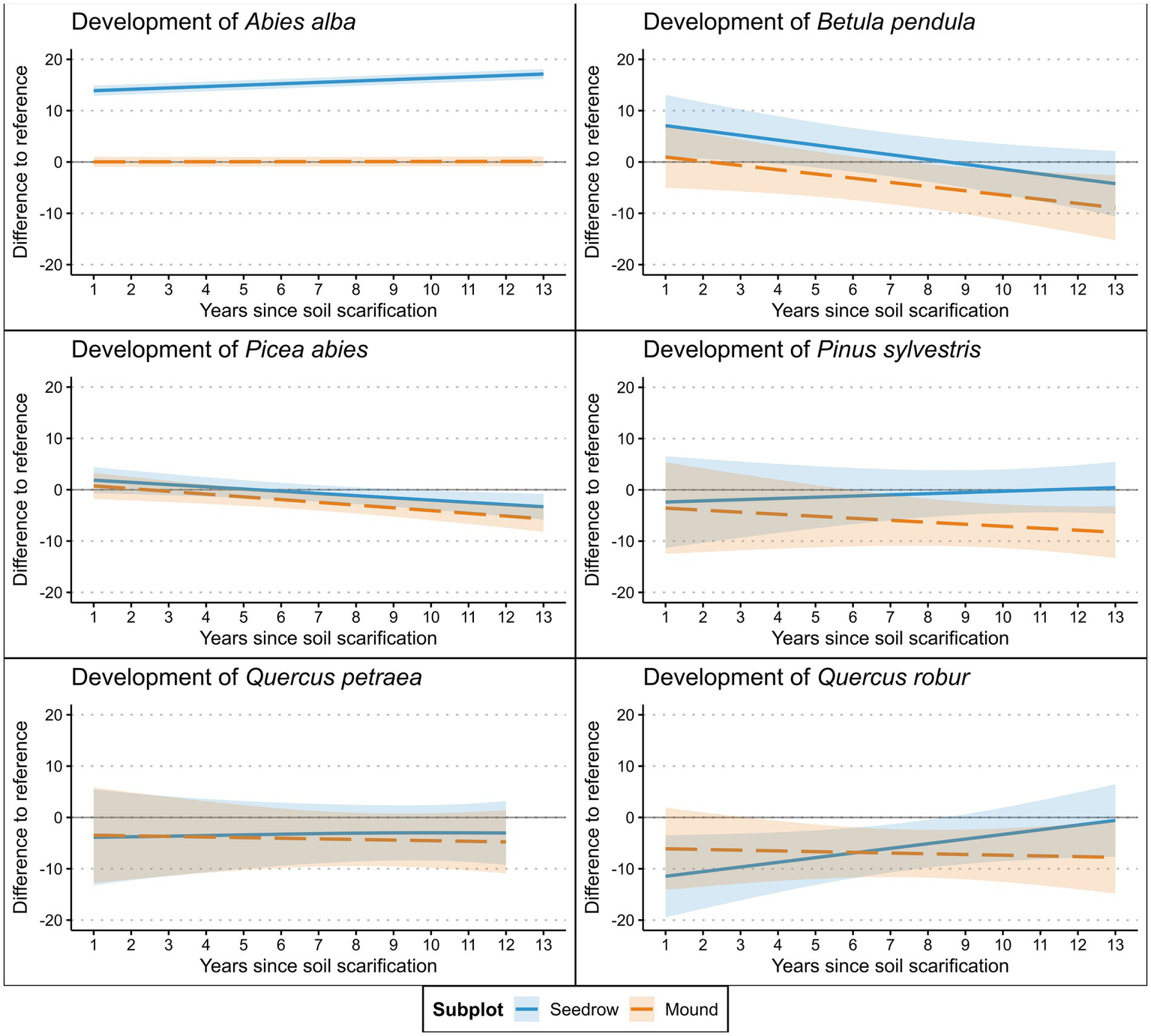

3.4 Species-specific developments

3.4.1 Tree regeneration

Of the five naturally occurring tree species in the regeneration, B. pendula exhibited higher cover in the seeding row, though only within the first two years after scarification, while Quercus robur demonstrated significantly lower cover (Table 4). P. abies, P. sylvestris, and Q. robur exhibited significantly lower cover on the soil mounds (Figure 4). Photogenically active radiation (PAR) positively impacted the cover of Q. robur but was negatively associated with the cover of A. alba. P. sylvestris exhibited a negative response to higher cover proportions of sown A. alba, whereas P. abies appeared to benefit from it. Additionally, B. pendula cover was negatively influenced by TWI, which indicates higher potential water availability. Q. petraea cover was negatively influenced by bryophyte presence.

Table 4

| Years since scarification | Environmental variables | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Factor | Estimate | SE | t-value | p-value | Predictor | Estimate | SE | t-value | p-value |

| Abies alba | R2 (adjusted) = 0.483 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.354 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | 15.669 | 0.474 | 33.020 | < 0.001 | (Intercept) | 15.156 | 1.043 | 14.533 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | 0.076 | 0.474 | 0.160 | 0.873 | PAR | −5.843 | 1.162 | −5.028 | < 0.001 | |

| Betula pendula | R2 (adjusted) = 0.671 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.210 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | 1.732 | 2.153 | 0.804 | 0.421 | (Intercept) | 4.462 | 1.357 | 3.289 | 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −3.707 | 2.153 | −1.722 | 0.085 | TWI | −3.371 | 1.330 | −2.534 | 0.011 | |

| Picea abies | R2 (adjusted) = 0.581 | R2 (adjusted) = −0.011 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −0.738 | 0.822 | −0.898 | 0.369 | (Intercept) | 4.215 | 0.448 | 9.400 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −2.468 | 0.822 | −3.004 | 0.003 | A. alba cover | 1.134 | 0.558 | 2.031 | 0.042 | |

| Pinus sylvestris | R2 (adjusted) = 0.725 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.184 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −0.292 | 2.174 | −0.134 | 0.893 | (Intercept) | 13.470 | 2.536 | 5.312 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −7.064 | 2.174 | −3.249 | 0.001 | A. alba cover | −5.595 | 2.598 | −2.154 | 0.031 | |

| Quercus petraea | R2 (adjusted) = 0.497 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.101 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −3.206 | 2.621 | −1.223 | 0.221 | (Intercept) | 2.032 | 0.730 | 2.783 | 0.005 | |

| Mounds | −4.366 | 2.621 | −1.666 | 0.095 | Bryophyte cover | −1.978 | 0.661 | −2.991 | 0.003 | |

| Quercus robur | R2 (adjusted) = 0.791 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.294 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −5.474 | 2.372 | −2.308 | 0.021 | (Intercept) | 1.682 | 0.424 | 3.972 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −7.024 | 2.372 | −2.961 | 0.003 | PAR | 1.668 | 0.483 | 3.452 | 0.001 | |

Shortened version of summary statistics of the generalized additive models (GAM) of the tree regeneration species with the cover development after scarification and environmental variables after model simplification.

Only significant factors (α < 0.05) and intercepts are displayed, for full version see Appendix 4.

Figure 4

Cover development of tree regeneration species identified at the surveyed plots after soil scarification modeled via GAM’s (Table 3). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence interval.

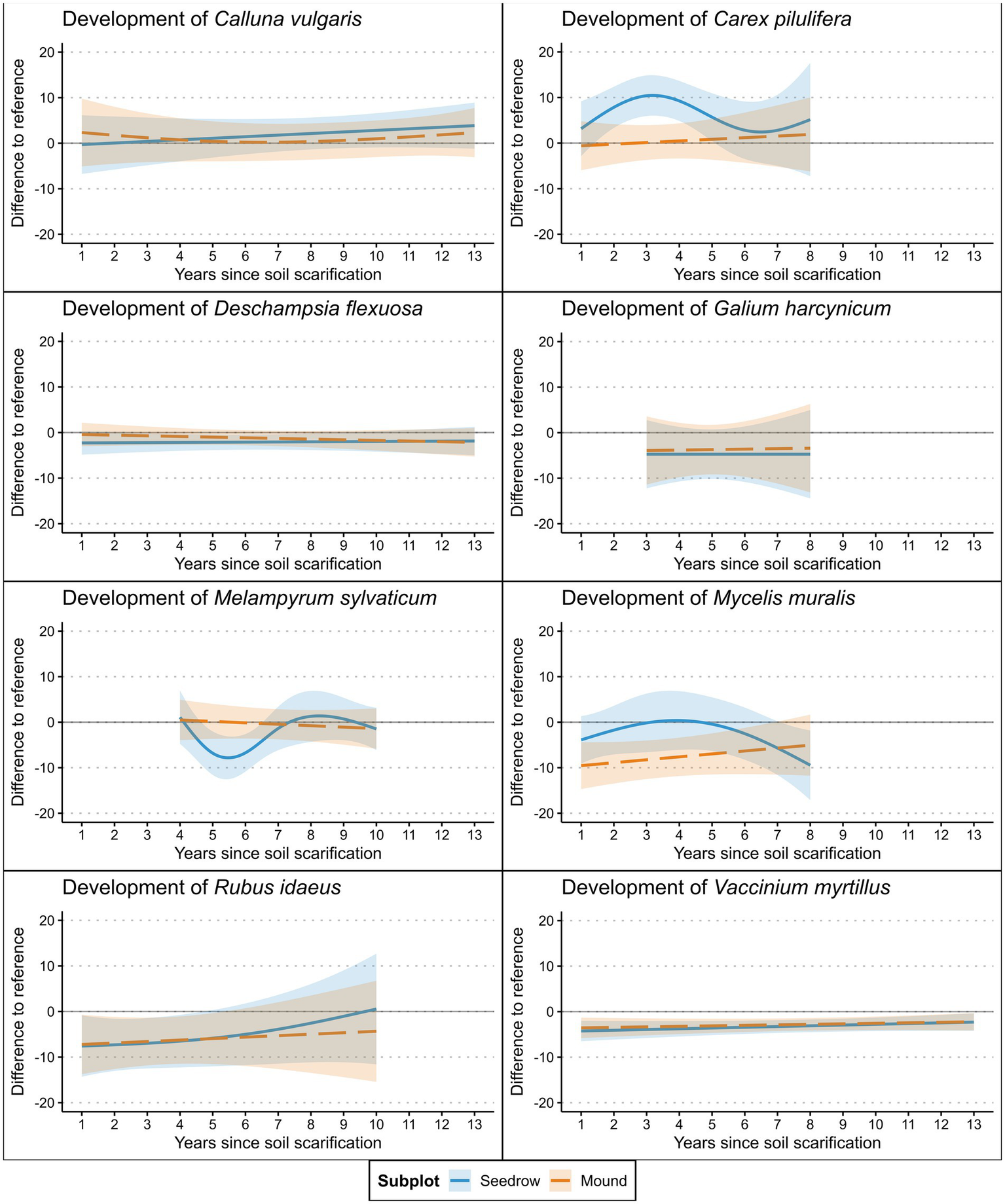

3.4.2 Herbaceous species

Of the examined herbaceous species, Rubus idaeus and Vaccinium myrtillus showed a significantly lower cover in both the seeding rows and mounds compared to the forest floor (Table 4). However, R. idaeus was not recorded in plots older than 10 years, a factor that may have influenced this finding (Table 5). Deschampsia flexousa showed significantly lower cover only in the seeding rows, while Carex pilulifera cover was significantly increased, though the species was only recorded in the first eight years of the timeframe surveyed (Figure 5). Mycelis muralis differed only in the soil mounds from the forest floor, with significantly lower cover values. Individual herbaceous species profited from a generally higher cover of herbaceous species (C. vulgaris, D. flexousa, G. harcynicum, V. myrtillus). M. muralis appeared to benefit from a higher shrub cover, while for V. myrtillus higher shrub cover exerted a negative effect. A contrasting effect was found for aspect, suggesting a positive effect of more south-facing slopes for V. myrtillus. The model also suggested that a denser bryophyte cover positively influenced V. myrtillus, while an additional positive effect of higher PAR availability was found for R. idaeus.

Table 5

| Years since scarification | Environmental variables | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Factor | Estimate | SE | t-value | p-value | Predictor | Estimate | SE | t-value | p-value |

| Calluna vulgaris | R2 (adjusted) = 0.653 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.048 | ||||||||

| seeding row | 2.184 | 1.787 | 1.222 | 0.222 | (Intercept) | 17.824 | 3.233 | 5.514 | < 0.001 | |

| mounds | 1.183 | 1.787 | 0.662 | 0.508 | Herb. cover | 6.498 | 3.152 | 2.061 | 0.039 | |

| Carex pilulifera | R2 (adjusted) = 0.650 | R2 (adjusted) = −0.067 | ||||||||

| seeding row | 6.925 | 1.917 | 3.613 | < 0.001 | (Intercept) | 2.811 | 0.636 | 4.418 | < 0.001 | |

| mounds | 0.281 | 1.917 | 0.147 | 0.883 | ||||||

| Deschampsia flexuosa | R2 (adjusted) = 0.567 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.207 | ||||||||

| seeding row | −2.094 | 0.843 | −2.483 | 0.013 | (Intercept) | 37.082 | 4.824 | 7.688 | < 0.001 | |

| mounds | −1.159 | 0.843 | −1.374 | 0.170 | Herb. cover | 25.215 | 5.093 | 4.951 | < 0.001 | |

| Galium harcynicum | R2 (adjusted) = 0.809 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.198 | ||||||||

| seeding row | −4.727 | 2.776 | −1.703 | 0.089 | (Intercept) | 4.407 | 3.786 | 1.164 | 0.244 | |

| mounds | −3.717 | 2.776 | −1.339 | 0.181 | Herb. cover | 7.471 | 3.616 | 2.066 | 0.039 | |

| Melampyrum sylvaticum | R2 (adjusted) = 0.100 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.191 | ||||||||

| seeding row | −2.976 | 1.691 | −1.760 | 0.078 | (Intercept) | 10.181 | 2.321 | 4.386 | < 0.001 | |

| mounds | −0.461 | 1.691 | −0.273 | 0.785 | ||||||

| Mycelis muralis | R2 (adjusted) = 0.686 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.625 | ||||||||

| seeding row | −3.985 | 2.136 | −1.866 | 0.062 | (Intercept) | 19.993 | 1.248 | 16.019 | < 0.001 | |

| mounds | −7.907 | 2.136 | −3.702 | < 0.001 | Shrub cover | 81.834 | 5.382 | 15.205 | < 0.001 | |

| Rubus idaeus | R2 (adjusted) = 0.468 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.551 | ||||||||

| seeding row | −6.066 | 2.634 | −2.303 | 0.021 | (Intercept) | −3.823 | 7.709 | −0.496 | 0.620 | |

| mounds | −6.391 | 2.634 | −2.426 | 0.015 | PAR | 5.989 | 1.753 | 3.418 | 0.001 | |

| Vaccinium myrtillus | R2 (adjusted) = 0.287 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.417 | ||||||||

| seeding row | −3.131 | 0.706 | −4.434 | < 0.001 | (Intercept) | 46.598 | 4.562 | 10.215 | < 0.001 | |

| mounds | −2.794 | 0.706 | −3.957 | < 0.001 | Aspect | 10.690 | 4.569 | 2.340 | 0.019 | |

| Herb. cover | 40.387 | 4.783 | 8.444 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Bryophyte cover | 10.667 | 4.731 | 2.255 | 0.024 | ||||||

| A. alba cover | −11.169 | 5.483 | −2.037 | 0.042 | ||||||

Shortened version of summary statistics of the generalized additive models (GAM) of the most common herbaceous species with the cover development after scarification and environmental variables after model simplification.

Only significant factors (α < 0.05) and intercepts are displayed, for full version see Appendix 5.

Figure 5

Cover development of the most common herbaceous species identified at the surveyed plots after soil scarification modeled via GAM’s (Table 4). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence interval.

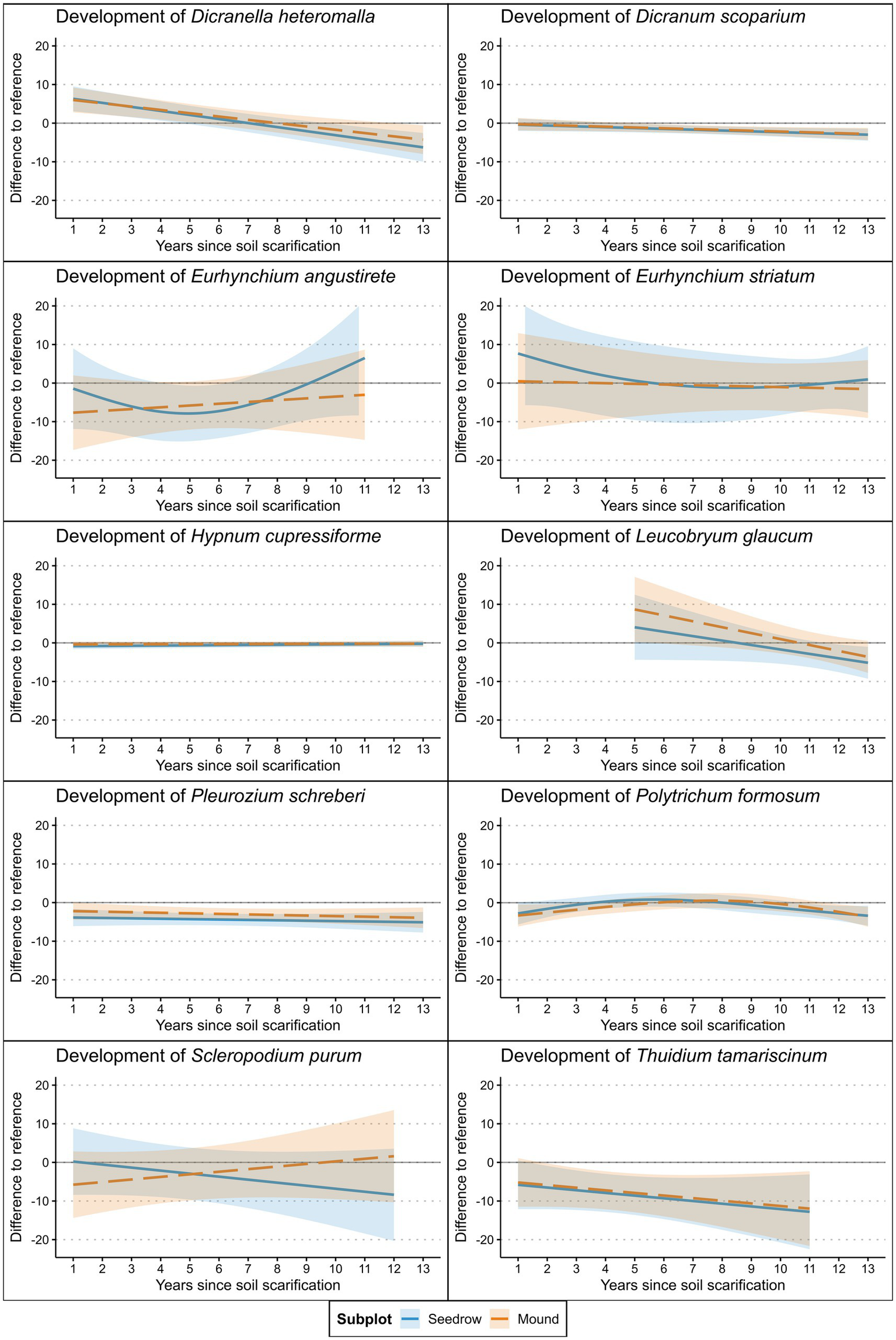

3.4.3 Bryophyte species

The cover of Dicranum scoparium, Pleurozium schreberi, and Thuidium tamariscinum on the forest floor was generally higher than on the other two subplot types (Table 6; Figure 6). These species were among the most prevalent, forming large continuous patches on the forest floor. No differences were observed for the other species compared to the forest floor. In the case of D. heteromalla and L. glaucum, this resulted from a higher cover in the scarification early in the surveyed timeframe, which gradually decreased, thereby diminishing any statistically significant differences. A similar trend was observed for E. striatum and Scerlopodium purum, though only with regard to the seeding rows. Of the environmental variables, aspect, in the sense of more south-facing slopes and high proportions of herbaceous cover, had a negative effect on the occurrence of D. scoparium (Table 6). High occurrences of A. alba had a negative effect on Hypnum cupressiforme, while higher bryophyte cover affected its cover positively. The positive effect of higher bryophyte cover was also found for E. angustirete, while high SWC negatively affected T. tamariscinum.

Table 6

| Years since scarification | Environmental variables | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Factor | Estimate | SE | t-value | p-value | Predictor | Estimate | SE | t-value | p-value |

| Dicranella heteromalla | R2 (adjusted) = 0.733 | R2 (adjusted) = −0.072 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | 0.883 | 1.192 | 0.740 | 0.459 | (Intercept) | 7.664 | 1.545 | 4.962 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | 1.563 | 1.192 | 1.310 | 0.190 | ||||||

| Dicranum scoparium | R2 (adjusted) = 0.254 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.056 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −1.727 | 0.524 | −3.299 | 0.001 | (Intercept) | 15.942 | 1.387 | 11.493 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −1.567 | 0.524 | −2.993 | 0.003 | Aspect | −3.517 | 1.452 | −2.422 | 0.015 | |

| Herb. cover | −3.782 | 1.480 | −2.556 | 0.011 | ||||||

| Eurhynchium angustirete | R2 (adjusted) = 0.756 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.161 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −4.180 | 3.168 | −1.319 | 0.187 | (Intercept) | 8.621 | 30.587 | 0.282 | 0.778 | |

| Mounds | −5.689 | 3.168 | −1.795 | 0.073 | Bryophyte cover | 23.104 | 11.437 | 2.020 | 0.043 | |

| Eurhynchium striatum | R2 (adjusted) = 0.645 | R2 (adjusted) = −0.0994 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | 1.012 | 3.116 | 0.325 | 0.745 | (Intercept) | −6.808 | 62.905 | −0.108 | 0.914 | |

| Mounds | −0.977 | 3.116 | −0.313 | 0.754 | ||||||

| Hypnum cupressiforme | R2 (adjusted) = −0.002 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.320 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −0.531 | 0.331 | −1.604 | 0.109 | (Intercept) | 68.846 | 4.540 | 15.164 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −0.290 | 0.331 | −0.877 | 0.380 | Bryophyte cover | 30.601 | 5.138 | 5.956 | < 0.001 | |

| A. alba cover | −16.111 | 5.812 | −2.772 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Leucobryum glaucum | R2 (adjusted) = 0.494 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.0169 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −3.033 | 1.753 | −1.730 | 0.084 | (Intercept) | 9.460 | 2.608 | 3.627 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −0.788 | 1.753 | −0.449 | 0.653 | ||||||

| Pleurozium schreberi | R2 (adjusted) = 0.601 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.055 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −4.395 | 0.771 | −5.704 | < 0.001 | (Intercept) | 32.068 | 4.112 | 7.799 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −2.948 | 0.771 | −3.826 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Polytrichum formosum | R2 (adjusted) = 0.601 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.003 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −1.111 | 0.691 | −1.608 | 0.108 | (Intercept) | 12.015 | 1.313 | 9.154 | < 0.001 | |

| Mounds | −1.404 | 0.691 | −2.033 | 0.042 | ||||||

| Scleropodium purum | R2 (adjusted) = 0.569 | R2 (adjusted) = −0.248 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −2.815 | 3.441 | −0.818 | 0.413 | (Intercept) | 6.457 | 2.118 | 3.049 | 0.002 | |

| Mounds | −3.172 | 3.441 | −0.922 | 0.357 | ||||||

| Thuidium tamariscinum | R2 (adjusted) = 0.778 | R2 (adjusted) = 0.045 | ||||||||

| Seeding row | −8.048 | 2.506 | −3.211 | 0.001 | (Intercept) | −22.857 | 37.965 | −0.602 | 0.547 | |

| Mounds | −7.365 | 2.506 | −2.939 | 0.003 | SWC | −40.586 | 16.988 | −2.389 | 0.017 | |

Shortened version of summary statistics of the generalized additive models (GAM) of the most common terricolous bryophytes with the cover development after scarification and environmental variables after model simplification.

Only significant factors (α < 0.05) and intercepts are displayed, for full version see Appendix 6.

Figure 6

Cover development of the most common terricolous bryophyte species identified at the surveyed plots after soil scarification modeled via GAM’s (Table 5). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence interval.

4 Discussion

4.1 Cover development after scarification

Although time alone was not the strongest predictor of cover development in the disturbed areas of the seeding rows and mounds, the results offer a robust estimate of the approximate timeline of recolonization following disturbance by scarification. Herbaceous species regeneration within the seeding rows took about ten years, likely due to a combination of the limited species pool and shaded conditions, making the sites unfavorable for more light-demanding, ruderal species.

On clear-cut sites, scarification can result in a closure of herbaceous species within two years, as reported by Pykälä (2004). However, the implementation of a closed or moderately open canopy through shelterwood or selection cutting management has been observed to extend the recolonization time (Nilsson et al., 2006; Löf et al., 2012). This delay hinders the enhancement of herbaceous diversity on the forest floor, but it facilitates the establishment of tree species by reducing competition from herbaceous species, which in clear-cut and calamity areas negatively affects tree regeneration (Nilsson et al., 2006; Fløistad et al., 2018).

The lower overall cover of seeding rows and mounds may have been, to an extent, mediated by the presence of A. alba as the target species of direct seeding, due to shading and providing a physical barrier for the establishment of other species. However, excluding A. alba already during the initial setup and plot selection would have posed a significant challenge, as bryophyte-covered seeding rows, particularly in older sites, were only identifiable through A. alba individuals. The decline in herbaceous cover on the soil mounds over time can be attributed to their composition, which consists of a mixture of an overturned bryophyte layer, organic material, and mineral soil. This facilitated the rapid settlement of overturned bryophytes, thereby hindering the ability of herbaceous species to establish themselves as well as outcompeting the remaining herbaceous species. The differences between the subplots are further exemplified by the indicator species of the pioneer phase. While multiple herbaceous species were identified within the seeding rows, only D. purpurea was found as an indicator species on the soil mounds. This species is known to possess a resilient seed bank that benefits from disturbance, likely explaining its presence (Sletvold and Rydgren, 2007).

Conversely, the recolonization rate of bryophytes in the seeding rows was comparatively faster. After four years, it had reached the level of the forest floor. The greater abundance of bryophyte species on the forest floor facilitated species’ dispersal into the seeding rows via clonal encroachment, propagules, or spores from the soil seed bank, consolidating their presence in all subplot types (Heinken and Zippel, 2004). This rapid recolonization may have constrained the settlement of herbaceous species and tree regeneration because these species require mineral soil for successful establishment. This most likely reduced overall herbaceous cover (Soudzilovskaia et al., 2011). The observed decline in bryophyte cover in both subplot types after a decade is likely due to the substantial shading caused by A. alba saplings and the subsequent rain interception. This led to a decline in light- and water-demanding bryophyte species (Tinya et al., 2009).

4.2 Effect on species composition

Scarification applied in the context of direct seeding was found to positively affect the recruitment of other tree species during the pioneer phase of the observed timeframe. Sometimes employed to facilitate and augment natural regeneration in clear-cut areas, the success of this technique has also been observed within the context of shelterwood cutting (Nilsson et al., 2006; Bergstedt et al., 2008). The present findings on the efficiency of this method under a closed canopy further emphasize the usefulness of this method. Light-seeded species, including B. pendula and P. abies exhibited a discernible positive impact from scarification. This finding is consistent with those reported by Karlsson and Nilsson (2005). In contrast to earlier studies, no evidence for a positive effect of scarification was found for P. sylvestris, another early successional species. However, in situ observations showed that the species benefited strongly from scarification when present as adult trees in the canopy (Figure 7). Unfortunately, as the number of sites with P. sylvestris canopy was highly limited, this could not be tested statistically. The two oak species did not profit from the scarification, as their dispersal is modulated by other factors, for example, the abundance of European jay (Garrulus glandarius L.), for which the scarification might not be attractive for seed storage (Mosandl and Kleinert, 1998). The impact on tree regeneration was also evident, with certain tree species identified as indicator species in the climax phase.

Figure 7

Natural regeneration of Pinus sylvestris intermixed with artificially regenerated Abies alba resulting from soil scarification for direct seeding.

In herbaceous vegetation, scarification led to a modest but mostly temporary change in the species composition, consistent with previous studies (Uotila and Kouki, 2005). This increase was most noticeable during the early successional phase. While numerous species were observed to emerge exclusively from scarification, they were limited to a small number of individuals that persisted over time and failed to propagate further. These species were not documented on the forest floor, but they were not rare in the surveyed forest in general. As the changes in the species composition were found to be rather slow, they lagged behind levels seen in clear- or shelterwood-cutting practices (Pykälä, 2004; Tullus et al., 2019). Of the more prevalent species, only C. pilulifera directly benefited from the scarification process, while species such as C. vulgaris, D. flexuosa, and M. muralis, which typically rapidly colonize disturbed sites, did not (van der Veken et al., 2007).

Generally, bryophytes demonstrated greater consistency in terms of species composition compared to herbaceous species. Among the bryophyte species, none were distinct to the disturbance; recruitment mostly occurred from the surrounding undisturbed forest floor (Heinken and Zippel, 2004). Early colonizer species, including D. heteromalla, E. striatum, and P. formosum, were found to rapidly establish themselves in the seeding row. In contrast, P. schreberi and H. cupressiforme, which were predominant on the forest floor, exhibited a decline in cover (Bergstedt et al., 2008). However, the initially colonizing species declined over time and were replaced by the more predominant species, especially H. cupressiforme, with cover proportions reaching that of the undisturbed forest floor (Hébert et al., 2016). These results align with studies conducted on open sites, which demonstrate that bryophyte species composition is largely determined by the pre-existing community before scarification, provided that there is no canopy disturbance (Fenton and Frego, 2005). Furthermore, the distribution of cover for individual species approached that of the undisturbed forest floor (Hébert et al., 2016). The convergence of the disturbance toward the undisturbed forest floor was also evident in the indicator species of the climax phase, which exhibited substantial overlap among the three subplots. For example, H. cupressiforme showed the prevalence of a few competitive bryophyte species generally found on the forest floor (Mills and Macdonald, 2004).

4.3 Environmental factors modulating species assemblage

Due to the limited number of tested environmental factors and their range, only minor influences on the recolonization dynamics of the tree species were found. Only photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) appeared to influence some species’ presence, with A. alba negatively and Q. robur positively affected, consistent with their typical regeneration niches (Dusan et al., 2007; Götmark et al., 2011). Consequently, the absence of a direct reaction from B. pendula or P. sylvestris to elevated light availability was unexpected, given their higher light demand and previous observations (Karlsson et al., 2002; Leuschner and Ellenberg, 2018). In general, the regeneration of B. pendula and P. sylvestris was largely unaffected by measured environmental factors, consistent with their generally low site requirements beyond light availability (Leuschner and Ellenberg, 2018). One exception was the topographic wetness index (TWI) which affected B. pendula abundance negatively, indicating that the species did suffer from potential waterlogging (Wang et al., 2017). Mineral soil availability was observed to be the most important environmental factor influencing the regeneration of B. pendula and P. abies, as evidenced by the cover development between the subplots and the in situ observations of P. sylvestris (Dassot and Collet, 2015). Although the effect on the species was less pronounced in our study, others found a strong relationship between their establishment success and the presence of exposed mineral soil, with this effect persisting for several years after scarification (Jäärats et al., 2012; Saursaunet et al., 2018). However, other studies demonstrated that P. abies exhibits a high degree of substrate indifference with respect to its germination behavior, with our results falling in between these contrasting observations (Oleskog and Sahlén, 2000).

The substantial impact of a well-developed herbaceous layer found on the present herbaceous species can be attributed to facilitation among these, likely resulting from enhanced microclimatic conditions (Brooker et al., 2008). Despite the absence of a discernible adverse impact of bryophyte cover on the establishment of herbaceous species, recruitment may have been impeded. This suggests that the extent of herbaceous species coverage has the potential to influence the species distribution (Tullus et al., 2019; Soudzilovskaia et al., 2011). Furthermore, the herbaceous species under consideration predominantly relied on mineral soil for generative expansion. The presence of a greater proportion of species with higher levels of cover, such as D. flexuosa or V. myrtillus, may have facilitated the settlement of other herbaceous species on the available mineral soil. While this effect may also stem from a certain degree of circularity inherent in the analysis, as the dependent species cover, which was not excluded from general cover, we hypothesize that this is not the case, as both cover-intensive and sparse-covering species were affected. Contrary to earlier findings, our research revealed only a limited impact of light availability on the herbaceous cover, affecting only V. myrtillus and R. idaeus (Hébert et al., 2016). In clear-cuts, increased light availability has been demonstrated to modify species composition, enabling the encroachment of ruderal species (Löf et al., 2012). In closed forest stands, however, while light remains an important factor in species assemblage, especially bryophytes were found to strongly depend on the site’s soil conditions (Tinya et al., 2009; Löf et al., 2012; Tullus et al., 2019). Including these factors to a greater extent would likely provide a more comprehensive explanation of the observed species’ composition and cover.

The presence of H. cupressiforme, as one of the most common bryophyte species, was primarily shaped by general bryophyte cover, as a widespread presence of bryophytes created a diverse range of microsites, supporting the establishment of this late successional species (Mills and Macdonald, 2004). Contrary to our expectations, no direct effect of light availability was found for pioneering and light-demanding species, such as D. heteromalla, D. scoparium and P. formosum was observed, with only D. scoparium showing a negative reaction to shrub cover, which can be interpreted as shading (Márialigeti et al., 2009; Tinya et al., 2009). Of the late successional species H. cupressiforme reacted negatively to substantial A. alba cover, with the shading provided by the seedlings potentially influencing the species colonization dynamics. In the absence of canopy disturbance, scarified areas are rapidly colonized by already dominant late successional species, which suppresses the establishment of other species and prevents changes in the species composition (Mills and Macdonald, 2004; Müller et al., 2019). In addition to the light regime, the availability of mineral soil emerged as a pivotal factor, influencing bryophyte species composition, by increasing the presence of pioneer species, which were otherwise absent or only minimally present. However, as is the case with herbaceous species, this effect is short-term only (Newmaster et al., 2007; Oheimb et al., 2007; Tullus et al., 2019).

Using space-for-time substitution to infer the temporal development in the succession following scarification is subject to certain limitations, as it assumes that time is the sole factor influencing succession (Kreyling, 2025). Although the observed species composition and cover development in this study are influenced by heterogeneity among different sites and plots, which cannot be accounted for due to the lack of comprehensive temporal data on these factors, we consider the general patterns observed in this study to be reliable. In our opinion, the modest geographic constraint of the surveyed area, together with the relatively stable canopy conditions of the surveyed sites since their respective scarification, has served to mitigate some of the uncertainties of the methodology. While four of the plots saw partial canopy removal during the year of the vegetation survey, as well as canopy removal in areas adjacent to the survey sites, we believe this had no effect on the results, as the sites showed no unusual deviations in terms of their species composition. The correspondence between our findings and those of related studies involving space-for-time substitution and long-term monitoring substantiates the validity of our results (Uotila and Kouki, 2005; Bergstedt et al., 2008; Jäärats et al., 2012; Tullus et al., 2019). While long-term studies have advantages over space-for-time approaches, studies on forest floor vegetation are rare. This underscores the necessity of alternative approaches, such as space-for-time substitution, as a means to study forest floor vegetation dynamics.

5 Conclusion

The soil scarification conducted under the intact spruce canopy did not result in long-lasting effects on the forest floor vegetation. The recolonization of herbaceous species took around a decade, with bryophytes settling comparatively faster. There was a noticeable short-term effect on the species composition through the increased microsite heterogeneity. This was particularly evident during the early successional phase. However, this effect was found to be not long-lasting, ultimately converging back to a species composition comparable to the undisturbed state. The settlement of species was mainly influenced by the availability of mineral soil. This was especially evident for tree species, underscoring the potential of the technique in fostering natural tree regeneration. This, in turn, would facilitate the transition of intact stands from even-aged forests dominated by single tree species to diverse, climate-tolerant forests. Additionally, several species could be identified as indicators of the different development stages. Overall, the results indicate that the species composition of acidophilic coniferous forests remains stable under an unaltered canopy following scarification, with tree regeneration being particularly enhanced.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization. AT: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources. BM: Writing – review & editing, Resources. KW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MB-R: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Forest Climate Fonds “Waldklimafonds” (funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection and by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture; administrated by Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe e.V.), within the project IntegSaat: Integration von Totholz in Verfahren der Direktsaat von Weißtanne (Abies alba) und Stiel-Eiche (Quercus robur) zur Begründung stabiler, klimatoleranter Mischwaldökosysteme im Stadtwald Hildburghausen (Funding Nr. 2220WK65X4).

Acknowledgments

We thank Pauline Macholdt for her support during the vegetation survey, and the vegetation ecology group of the Institute of Biodiversity, Ecology and Evolution, Friedrich Schiller University Jena for fruitful discussions about the topic of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2025.1708997/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Ammer Christian Mosandl Reinhard Kateb Hany El 2002 Direct seeding of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst.) stands—effects of canopy density and fine root biomass on seed germination For. Ecol. Manag. 159 59–72 doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00710-1

2

Bergstedt J. Hagner M. Milberg P. (2008). Effects on vegetation composition of a modified forest harvesting and propagation method compared with clear-cutting, scarification and planting. Appl. Veg. Sci.11, 159–168. doi: 10.3170/2007-7-18343

3

Beven K. J. Kirkby M. J. (1979). A physically based, variable contributing area model of basin hydrology / Un modèle à base physique de zone d'appel variable de l'hydrologie du bassin versant. Hydrol. Sci. Bull.24, 43–69. doi: 10.1080/02626667909491834

4

Brooker R. W. Maestre F. T. Callaway R. M. Lortie C. L. Cavieres L. A. Kunstler G. et al . (2008). Facilitation in plant communities: the past, the present, and the future. J. Ecol.96, 18–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01295.x

5

Conrad O. Bechtel B. Bock M. Dietrich H. Fischer E. Gerlitz L. et al . (2015). System for automated geoscientific analyses (SAGA) v. 2.1.4. Geosci. Model Dev.8, 1991–2007. doi: 10.5194/gmd-8-1991-2015

6

Dassot M. Collet C. (2015). Manipulating seed availability, plant competition and litter accumulation by soil preparation and canopy opening to ensure regeneration success in temperate low-mountain forest stands. Eur. J. Forest Res.134, 247–259. doi: 10.1007/s10342-014-0847-x

7

Cáceres Miquel de Legendre Pierre 2009 Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference Ecology 90 3566–3574 doi: 10.1890/08-1823.1

8

Dusan R. Stjepan M. Igor A. Jurij D. (2007). Gap regeneration patterns in relationship to light heterogeneity in two old-growth beech fir forest reserves in South East Europe. Forestry80, 431–443. doi: 10.1093/forestry/cpm037

9

Eldridge D. J. Guirado E. Reich P. B. Ochoa-Hueso R. Berdugo M. Sáez-Sandino T. et al . (2023). The global contribution of soil mosses to ecosystem services. Nat. Geosci.16:430, –438. doi: 10.1038/s41561-023-01170-x

10

Euro+Med PlantBase (2025). The information resource for Euro-Mediterranean plant diversity. Available online at http://www.europlusmed.org (accessed June 26, 2025).

11

Fenton N. J. Frego K. A. (2005). Bryophyte (moss and liverwort) conservation under remnant canopy in managed forests. Biol. Conserv.122, 417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2004.09.003

12

FFK Gotha . (2022). Forstliche Standortkartierung: ThüringenForst AöR, Forstliches Forschungs- und Kompetenzzentrum. Available online at https://geomis.geoportal-th.de/geonetwork/srv/api/records/98024be1-7c82-463e-b358-46e24918d100 (accessed May 26, 2025).

13

Fischer H. S. (2015). On the combination of species cover values from different vegetation layers. Appl. Veg. Sci.18, 169–170. doi: 10.1111/avsc.12130

14

Fløistad I. S. Hylen G. Hanssen K. H. Granhus A. (2018). Germination and seedling establishment of Norway spruce (Picea abies) after clear-cutting is affected by timing of soil scarification. New For.49, 231–247. doi: 10.1007/s11056-017-9616-2

15

GDI-Th (2025). DGM - Höhendaten des Thüringer Landesamtes für Bodenmanagement und Geoinformation in 1x1km Kacheln. Erfurt: Kompetenzzentrum Geodateninfrastruktur Thüringen (GDI-Th).

16

Gilliam F. S. (2007). The ecological significance of the herbaceous layer in temperate forest ecosystems. Bioscience57, 845–858. doi: 10.1641/B571007

17

Götmark F. Schott K. M. Jensen A. M. (2011). Factors influencing presence–absence of oak (Quercus spp.) seedlings after conservation-oriented partial cutting of high forests in Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res.26, 136–145. doi: 10.1080/02827581.2010.536570

18

Grossnickle S. Ivetić V. (2017). Direct seeding in reforestation – a field performance review. REFOR4, 94–142. doi: 10.21750/REFOR.4.07.46

19

Hansson L. J. Ring E. Franko M. A. Gärdenäs A. I. (2018). Soil temperature and water content dynamics after disc trenching a sub-xeric Scots pine clearcut in central Sweden. Geoderma327, 85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.04.023

20

Hastie T. J. Tibshirani R. J. (2017). Monographs on statistics and applied probability. London: Routledge.

21

Hébert F. Bachand M. Thiffault N. Paré D. Gagné P. (2016). Recovery of plant community functional traits following severe soil perturbation in plantations: a case-study. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag.12, 116–127. doi: 10.1080/21513732.2016.1146334

22

Heinken T. Zippel E. (2004). Natural re-colonization of experimental gaps by terricolous bryophytes in Central European pine forests. Nova Hedwigia79, 329–351. doi: 10.1127/0029-5035/2004/0079-0329

23

Huth F. Wehnert A. Tiebel K. Wagner S. (2017). Direct seeding of silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) to convert Norway spruce (Picea abies L.) forests in Europe: a review. For. Ecol. Manag.403, 61–78. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2017.08.017

24

Jäärats A. Sims A. Seemen H. (2012). The effect of soil scarification on natural regeneration in forest microsites in Estonia. Balt. For.18, 133–143.

25

Johansson K. Söderbergh I. Nilsson U. Lee Allen H. (2005). Effects of scarification and mulch on establishment and growth of six different clones of Picea abies. Scand. J. For. Res.20, 421–430. doi: 10.1080/02827580500292121

26

Karlsson M. Nilsson U. (2005). The effects of scarification and shelterwood treatments on naturally regenerated seedlings in southern Sweden. For. Ecol. Manag.205, 183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2004.10.046

27

Karlsson M. Nilsson U. Örlander G. (2002). Natural regeneration in clear-cuts: effects of scarification, slash removal and clear-cut age. Scand. J. For. Res.17, 131–138. doi: 10.1080/028275802753626773

28

Kreyling J. (2025). Space-for-time substitution misleads projections of plant community and stand-structure development after disturbance in a slow-growing environment. J. Ecol.113, 68–80. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.14438

29

Kristensen H. L. McCarty G. W. Meisinger J. J. (2000). Effects of soil structure disturbance on mineralization of organic soil nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. Amer J.64, 371–378. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2000.641371x

30

Lenth R. V. Piaskowski J. (2025). emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. Available online at: https://rvlenth.github.io/emmeans/ (Accessed January 09 2025).

31

Leuschner C. Ellenberg H. (2018). Vegetation ecology of Central Europe. Cham: Springer.

32

Löf M. Castro J. Engman M. Leverkus A. B. Madsen P. Reque J. A. et al . (2019). Tamm review: Direct seeding to restore oak (Quercus spp.) forests and woodlands. For. Ecol. Manag.448, 474–489. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2019.06.032

33

Löf M. Dey D. C. Navarro R. M. Jacobs D. F. (2012). Mechanical site preparation for forest restoration. New For.43, 825–848. doi: 10.1007/s11056-012-9332-x

34

Márialigeti S. Németh B. Tinya F. Ódor P. (2009). The effects of stand structure on ground-floor bryophyte assemblages in temperate mixed forests. Biodivers. Conserv.18, 2223–2241. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9586-6

35

Mills S. E. Macdonald S. E. (2004). Predictors of moss and liverwort species diversity of microsites in conifer-dominated boreal forest. J. Veg. Sci.15, 189–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2004.tb02254.x

36

Mosandl R. Kleinert A. (1998). Development of oaks (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) emerged from bird-dispersed seeds under old-growth pine (Pinus silvestris L.) stands. For. Ecol. Manag.106, 35–44. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(97)00237-5

37

Müller J. Boch S. Prati D. Socher S. A. Pommer U. Hessenmöller D. et al . (2019). Effects of forest management on bryophyte species richness in Central European forests. For. Ecol. Manag.432, 850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.10.019

38

Newmaster S. G. Parker W. C. Bell F. W. Paterson J. M. (2007). Effects of forest floor disturbances by mechanical site preparation on floristic diversity in a central Ontario clearcut. For. Ecol. Manag.246, 196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2007.03.058

39

Nilsson U. Örlander G. (1999). Vegetation management on grass-dominated clearcuts planted with Norway spruce in southern Sweden. Can. J. For. Res.29, 1015–1026. doi: 10.1139/x99-071

40

Nilsson U. Örlander G. Karlsson M. (2006). Establishing mixed forests in Sweden by combining planting and natural regeneration—effects of shelterwoods and scarification. For. Ecol. Manag.237, 301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2006.09.053

41

Oheimb G. Friedel A. Bertsch A. Härdtle W. (2007). The effects of windthrow on plant species richness in a Central European beech forest. Plant Ecol.191, 47–65. doi: 10.1007/s11258-006-9213-5

42

Oksanen J. Simpson G. L. Blanchet F. G. Kindt R. Legendre P. Minchin P. R. (2025). vegan: Community Ecology Package (Version 2.6–10). Cham: Springer.

43

Oleskog G. Sahlén K. (2000). Effects of seedbed substrate on moisture conditions and germination of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) seeds in a mixed conifer stand. New For.20, 119–133. doi: 10.1023/A:1006783900412

44

Pardos M. Del Río M. Pretzsch H. Jactel H. Bielak K. Bravo F. et al . (2021). The greater resilience of mixed forests to drought mainly depends on their composition: Analysis along a climate gradient across Europe. Forest Ecol. Manage.481:118687. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118687

45

Pfadenhauer J. Poschlod P. Buchwald R. (1986). Überlegungen zu einem Konzept geobotanischer Dauerbeobachtungsflächen für Bayern. Teil I. Methodik der Anlage und Aufnahme. Ber. Bayer. Akad. Naturschutz Landschaftspflege10, 41–60.

46

Porada P. van Stan J. T. Kleidon A. (2018). Significant contribution of non-vascular vegetation to global rainfall interception. Nat. Geosci.11, 563–567. doi: 10.1038/s41561-018-0176-7

47

Pykälä J. (2004). Immediate increase in plant species richness after clear-cutting of boreal herb-rich forests. Appl. Veg. Sci.7, 29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-109X.2004.tb00592.x

48

QGIS Development Team (2022). QGIS Geographic Information System: QGIS Association. Geneva: QGIS Development Team.

49

R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

50

Saursaunet M. Mathisen K. M. Skarpe C. (2018). Effects of increased soil scarification intensity on natural regeneration of Scots pine Pinus sylvestris L. and birch Betula spp. L.Forests9:262. doi: 10.3390/f9050262

51

Sletvold N. Rydgren K. (2007). Population dynamics in Digitalis purpurea: the interaction of disturbance and seed bank dynamics. J. Ecol.95, 1346–1359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01287.x

52

Soudzilovskaia N. A. Graae B. J. Douma J. C. Grau O. Milbau A. Shevtsova A. et al . (2011). How do bryophytes govern generative recruitment of vascular plants?New Phytol.190, 1019–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03644.x

53

Stenger R. Priesack E. Beese F. (1995). Rates of net nitrogen mineralization in disturbed and undisturbed soils. Plant Soil171, 323–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00010288

54

Thrippleton T. Bugmann H. Folini M. Snell R. S. (2018). Overstorey–understorey interactions intensify after drought-induced forest die-off: long-term effects for forest structure and composition. Ecosystems21, 723–739. doi: 10.1007/s10021-017-0181-5

55

Thrippleton T. Bugmann H. Kramer-Priewasser K. Snell R. S. (2016). Herbaceous understorey: an overlooked player in forest landscape dynamics?Ecosystems19, 1240–1254. doi: 10.1007/s10021-016-9999-5

56

Tinya F. Márialigeti S. Király I. Németh B. Ódor P. (2009). The effect of light conditions on herbs, bryophytes and seedlings of temperate mixed forests in Őrség, Western Hungary. Plant Ecol.204, 69–81. doi: 10.1007/s11258-008-9566-z

57

TLUBN (2024). Digitale Bodenübersichtskarte von Thüringen 1:400.000 (BÜK400). Jena: Thüringer Landesamt für Umwelt, Bergbau und Naturschutz (TLUBN).

58

Tullus T. Tishler M. Rosenvald R. Tullus A. Lutter R. Tullus H. (2019). Early responses of vascular plant and bryophyte communities to uniform shelterwood cutting in hemiboreal Scots pine forests. For. Ecol. Manag.440, 70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2019.03.009

59

Uotila A. Kouki J. (2005). Understorey vegetation in spruce-dominated forests in eastern Finland and Russian Karelia: successional patterns after anthropogenic and natural disturbances. For. Ecol. Manag.215, 113–137. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2005.05.008

60

van der Veken S. Bellemare J. Verheyen K. Hermy M. (2007). Life-history traits are correlated with geographical distribution patterns of western European forest herb species. J. Biogeogr.34, 1723–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01738.x

61

Vitasse Y. Bottero A. Cailleret M. Bigler C. Fonti P. Gessler A. et al . (2019). Contrasting resistance and resilience to extreme drought and late spring frost in five major European tree species. Glob. Change Biol.25, 3781–3792. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14803

62

Wang A.-F. Roitto M. Lehto T. Sutinen S. Heinonen J. Zhang G. et al . (2017). Photosynthesis, nutrient accumulation and growth of two Betula species exposed to waterlogging in late dormancy and in the early growing season. Tree Physiol.37, 767–778. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx021

63

Wickham H. Averick M. Bryan J. Chang W. McGowan L. François R. et al . (2019). Welcome to the tidyverse. JOSS4:1686. doi: 10.21105/joss.01686

64

Willoughby I. H. Jinks R. L. Forster J. (2019). Direct seeding of birch, rowan and alder can be a viable technique for the restoration of upland native woodland in the UK. Forestry92, 324–338. doi: 10.1093/forestry/cpz018

65

Wood S. N. (2017). Generalized additive models. An introduction with R. Second Edn. Boca Raton: CRC Press (Chapman & Hall/CRC texts in statistical science series).

Summary

Keywords

direct seeding, forest conversion, canopy cover, biodiversity, bryophytes, herbaceous vegetation, tree regeneration

Citation

Medicus T, Tischer A, Michalzik B, Wagner K and Bernhardt-Römermann M (2025) Soil scarification does not affect the medium-term species composition of Norway spruce stands. Front. For. Glob. Change 8:1708997. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2025.1708997

Received

19 September 2025

Revised

19 November 2025

Accepted

20 November 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

8 - 2025

Edited by

Chang-Bae Lee, Kookmin University, Republic of Korea

Reviewed by

Alexander Seliger, University of Applied Sciences and Arts (HAWK), Germany

Fidele Bognounou, Natural Resources Canada, Canada

Krzysztof Turczański, Poznan University of Life Sciences, Poland

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Medicus, Tischer, Michalzik, Wagner and Bernhardt-Römermann.