- 1Department of Neonatology, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Department of Vascular Surgery, Deutsches Rotes Kreuz Kliniken Berlin Köpenick, Berlin, Germany

- 3Department of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 4Private Practice Dipl. Med. Trebuth, Beelitz, Germany

- 5Department of Pediatric Pulmonology, Immunology and Intensive Care, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Objective: To investigate and compare nurses' perceived care-related distress and experiences in end-of-life situations in neonatal and pediatric intensive care units.

Study design: Single-center, cross-sectional survey. Administration of an anonymous self-report questionnaire survey to nurses of two tertiary neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), and two tertiary pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) in Berlin, Germany.

Results: Seventy-three (73/227, response rate 32.2%) nurses completed surveys. Both, NICU (32/49; 65.3%) and PICU (24/24; 100.0%) nurses, reported “staffing shortages” to be the most frequent source of distress in end-of-life situations. However, when asked for the most distressing factor, the most common response by NICU nurses (17/49) was “lack of clearly defined and agreed upon therapeutic goals”, while for PICU nurses (12/24) it was “insufficient time and staffing”. No significant differences were found in reported distress-related symptoms in NICU and PICU nurses. The interventions rated by NICU nurses as most helpful for coping were: “discussion time before the patient's death” (89.6%), “team support” (87.5%), and “discussion time after the patient's death” (87.5%). PICU nurses identified “compassion” (98.8%), “team support”, “personal/private life (family, friends, hobbies)”, and “discussion time after the patient's death” (all 87.5%) as most helpful.

Conclusions: Distress-related symptoms as a result of end-of-life care were commonly reported by NICU and PICU nurses. The most frequent and distressing factors in end-of-life situations might be reduced by improving institutional/organizational factors. Addressing the consequences of redirection of care, however, seems to be a more relevant issue for the relief of distress associated with end-of-life situations in NICU, as compared to PICU nurses.

Introduction

Most childhood deaths within the hospital, whether anticipated or unexpected, occur in settings primarily designed to provide acute, high-tech medicine intended for aggressive, often invasive, life-extending care: the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Although palliative care services for children are becoming an accepted element of comprehensive, family-centered care (1, 2), the current nature of NICU and PICU setting presents special challenges to medical staff providing end-of-life care. Integrating psychosocial, spiritual, emotional, and practical support for families in addition to holistic treatment for the child might thus be perceived as representing merely another of many challenges.

Studies have shown that quality of patient care is reduced by increasing distress in nurses (3, 4). In caring for highly vulnerable intensive care unit (ICU) patients in end-of-life situations it is essential to evaluate specific factors of distress in nursing staff. Such evaluations have the potential to provide data necessary for (i) protecting ICU-nursing staff from emotional, psychological and physical harm by optimizing institutional support, and (ii) optimizing the quality of care of the dying ICU-patient.

Studies evaluating distress in medical staff caring for patients in end-of-life situations have been almost exclusively focused on adult (5–10), pediatric (11–18) or neonatal patients (19–28). There are only a very limited number of cross-sectional surveys (29–32) and almost all of them are directed specifically to “moral distress.”

Today, there exists a paucity of reliable information regarding nursing staff experiences with end-of-life care in German neonatal and pediatric intensive care units. As medical health care systems are different, results and conclusions from studies of other countries cannot be automatically applied to the local setting. The aim of the present work is to investigate and compare nurses' perceived care-related distress and experiences in end-of-life situations in tertiary neonatal and pediatric intensive care units of a German university hospital.

Methods

Setting

The survey was conducted at the Charité University Medical Center Berlin, Germany and comprised two tertiary neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), and two pediatric intensive care units (PICUs), a medical-surgical and a hematological/oncological, respectively. Eligible participants included all nurses involved in direct clinical care with at least 6 months of critical care experience.

Questionnaire

A self-administered standardized questionnaire was used in order to (1) allow efficient collection of information from a large number of respondents; (2) eliminate interviewer-related errors and acquiescence bias; (3) allow the collection of a wide range of information; (4) allow participants to answer sensitive questions in private, and (5) permit ease of administration.

The questionnaire was written in German and contained four types of questions: (i) yes/no questions; (ii) multiple choice questions which allowed participants to select one or more answers; (iii) scaled questions featuring items to be rated using a five-point Likert scale with options such as “always” and “never” as the two extremes; and (iv) open ended questions.

The 18 questions used for this survey were adapted from previous reports (17, 33–35) or were newly written for the purposes of the present study. The face validity of the questionnaire was assessed by a four-person expert panel which consisted of one NICU nurse, one physician working in pediatric oncology, one member of a parents' psychological counseling team, and one psychologist with expertise in survey methodology. The panel reviewed all items for accuracy of content, comprehensiveness, and relevance to the aim of the present study. All panel members agreed that the content of the questionnaire was consistent with the objectives of the present work.

A preliminary version of the questionnaire was piloted with 26 participants of a multiprofessional panel composed of nurses, physicians and psychologists during a 4 week pediatric palliative care course at the Department of Children's Pain Therapy and Pediatric Palliative Care (Witten/Herdecke University, Faculty of Health–School of Medicine, Datteln, Germany), and questions were further revised based on the feedback.

The questionnaire acquired information on the following three topics:

1. Frequency and sources of distress perceived in end-of-life care situations.

2. Personal responses and coping mechanisms related to distress in end-of-life care situations.

3. Factors enabling staff to function effectively and cope with distress in end-of-life care.

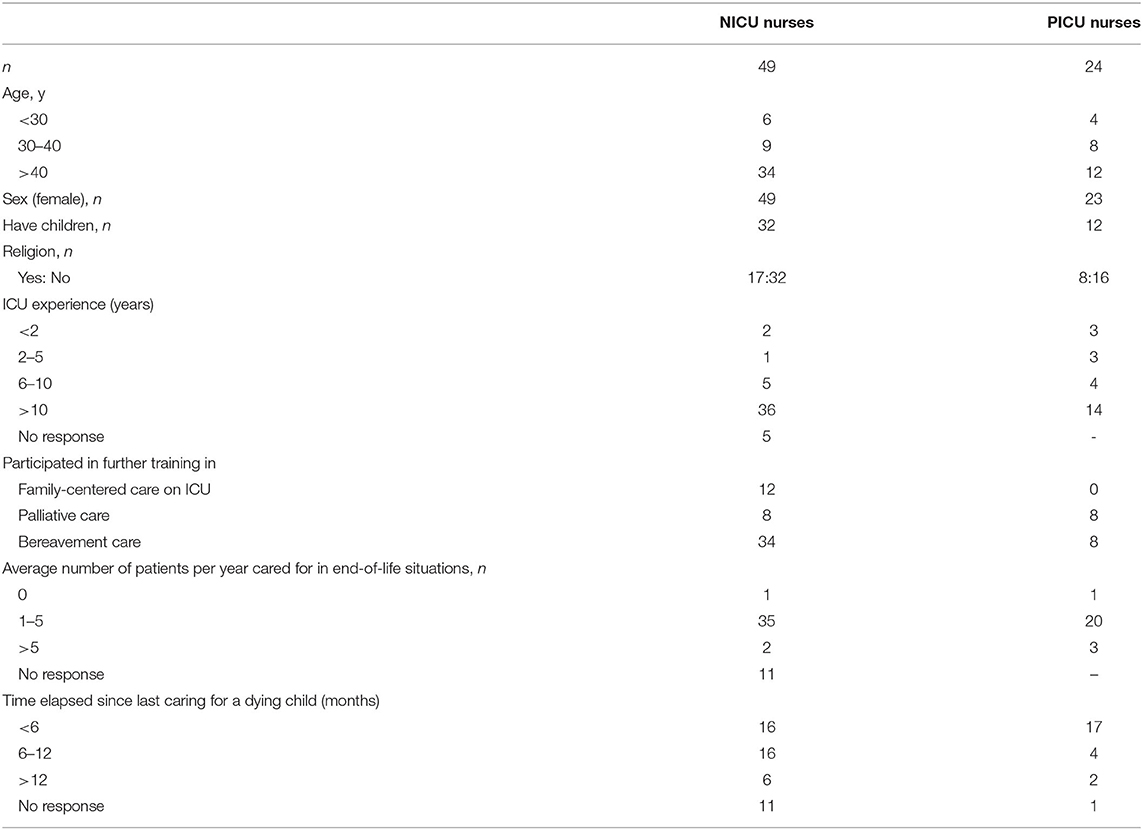

All participants were also asked to provide basic sociodemographic information including age, gender, parental status, religion, years in intensive care, primary professional field (NICU or PICU), number of patients cared for in end-of-life situations, as well as experience with specialized training in palliative care, bereavement support and pain management/symptom control.

The data were collected in a manner that made it impossible to link a respondent to his or her response or to distinguish respondents from non-respondents.

Data Collection

Nurses of the participating units were informed about the study via short lectures one month before being contacted by mail and asked to anonymously complete a posted paper version of the questionnaire. Eight weeks after posting the questionnaires a second appeal to participate in the study was sent by mail to all nurses. Inclusion of subsequently received questionnaires was limited to four additional weeks.

Approval by Ethics Committee

The study was approved by the local institutional review board (Ethikkommission der Charité, #EA2/060/14).

Statistical Analysis

All data were categorical in nature. The descriptive statistic used was the frequency distribution of each variable. The chi-square test was used to analyse proportions. All statistical calculations were made with the aid of SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The data from the three open-ended questions used in the survey were subjectively analyzed.

Results

Demographic Data

A total of 75/227 completed surveys were returned (2 were excluded for incomplete data), for a response rate of 32.2%. Of the remaining 73 surveys, 49 were from the NICU (response rate 36.6%, 49/134) and 24 were from the PICU (response rate 25.8%, 24/93). Respondents were predominately female (72 of 73, 98.6%), most were older than 40 years (46 of 73, 63.0%), and had more than 10 years of experience in critical care (50 of 73, 68.5 %). Sociodemographic data of all participating nurses are summarized in Table 1.

Frequency and Sources of Distress

Self-Reported Most Frequent Sources of Distress in End-of-Life Care Situations

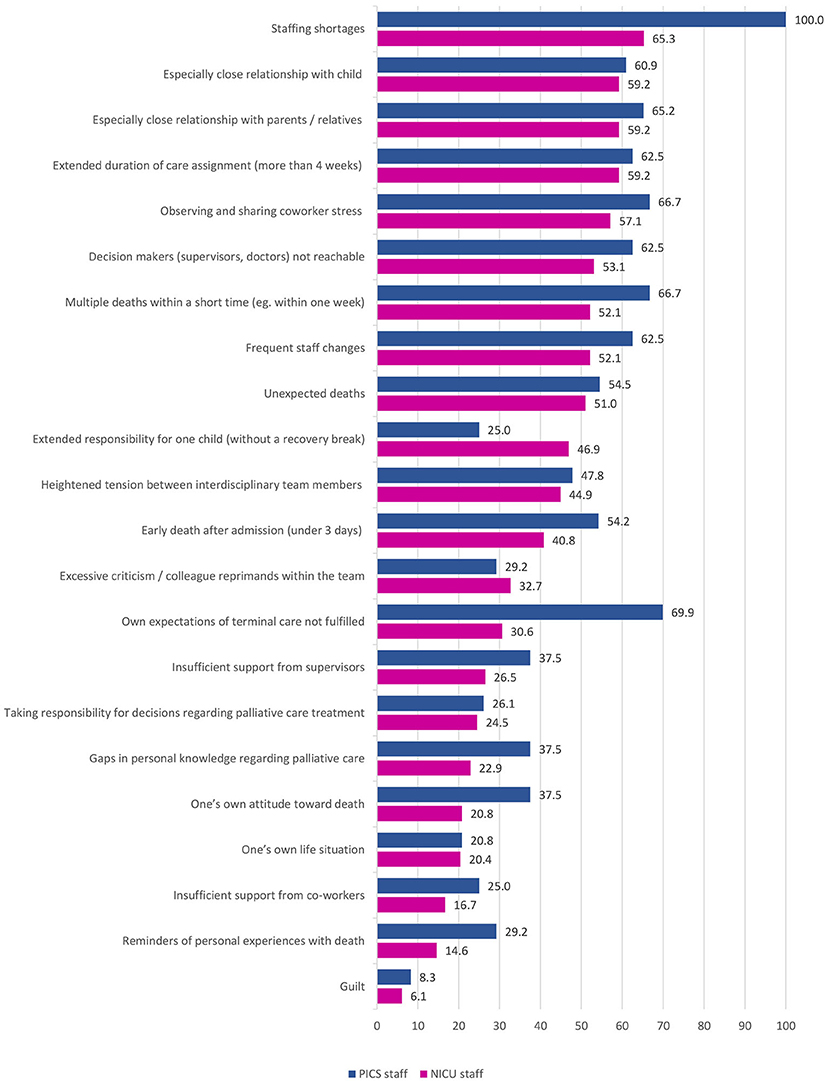

A list of 22 potential sources of distress in end-of-life care situations was presented and participants were asked to rate the frequency of each item using a five-point Likert scale with options “always” and “never” as the two extremes (scaled question). Both, NICU (65.3%) and PICU (100.0%) nurses, reported “staffing shortages” to be the most frequent source of distress in end-of-life situations. Additional distressing factors frequently reported by NICU nurses included “especially close relationship with the child”, “especially close relationship with parents/relatives”, and “extended duration of care assignment (more than 4 weeks)”, all at identical rates of 59.2%. PICU nurses also rated “own expectations of terminal care not fulfilled” (69.6%), “multiple deaths within a short time (e.g. within one week)”, and “observing coworkers being in distress”, the latter two in 66.7% of respondents, as very frequent sources of distress. Self-reported most frequent sources of distress in end-of-life care situations by NICU und PICU staff are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Self-reported most frequent (rated as “often,” “very often,” or “always”) sources of distress in end-of-life care situations as self-reported by NICU und PICU staff (%).

Self-Reported Most Distressing Factors in End-of-Life Care Situations

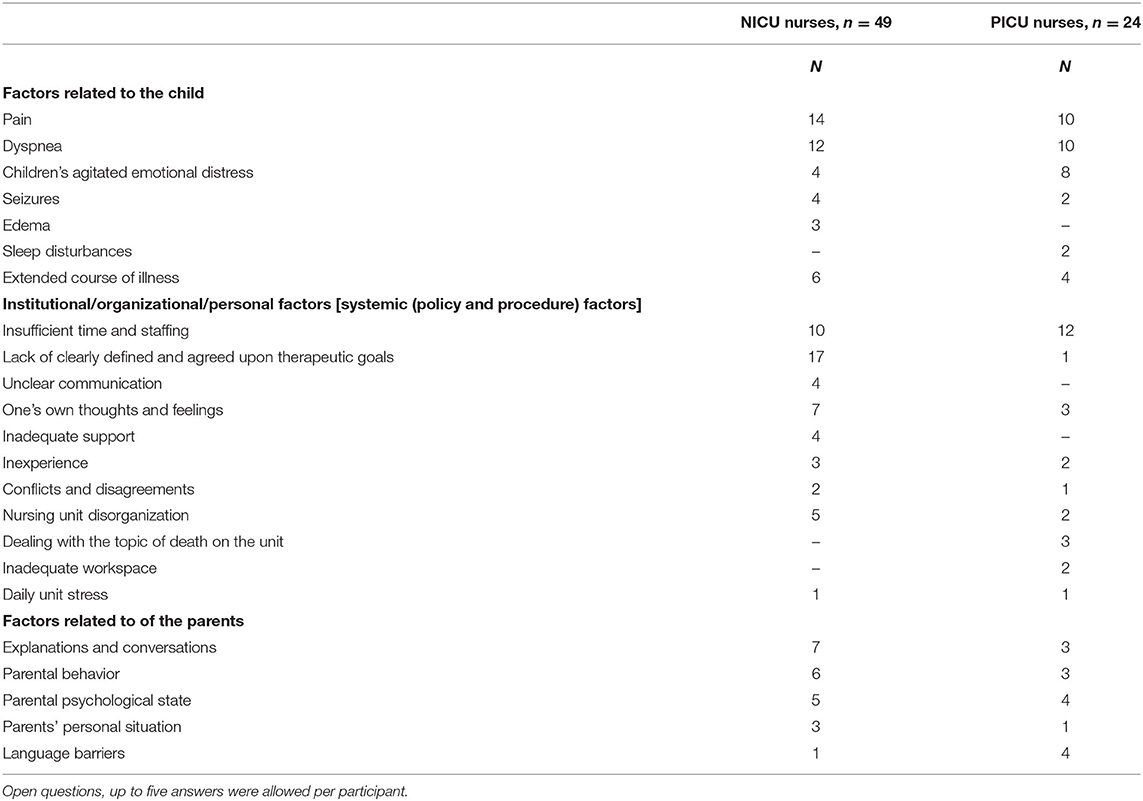

When openly asked for the most distressing factors in end-of-life situations with a maximum of 5 answers allowed, the answers of NICU and PICU nurses divided into three main groups: distress related to (i) the dying child, (ii) institutional/organizational factors, and (iii) the parents.

The three most frequently reported distressing factors were “lack of clearly defined and agreed upon therapeutic goals” (17/49), “pain” (14/49), and “dyspnea” (12/49) for NICU nurses, and “insufficient time and staffing” (12/24), “pain” (10/24), and “dyspnea” (10/24) for PICU nurses, respectively. Self-reported most distressing sources of distress in end-of-life care situations by NICU und PICU staff are summarize in Table 2.

Table 2. Self-reported most distressing sources of distress in end-of-life care situations by NICU and PICU staff.

Self-Reported Distress-Related Symptoms and Coping Mechanisms

Self-Reported Distress-Related Symptoms as a Result of End-of-Life Care

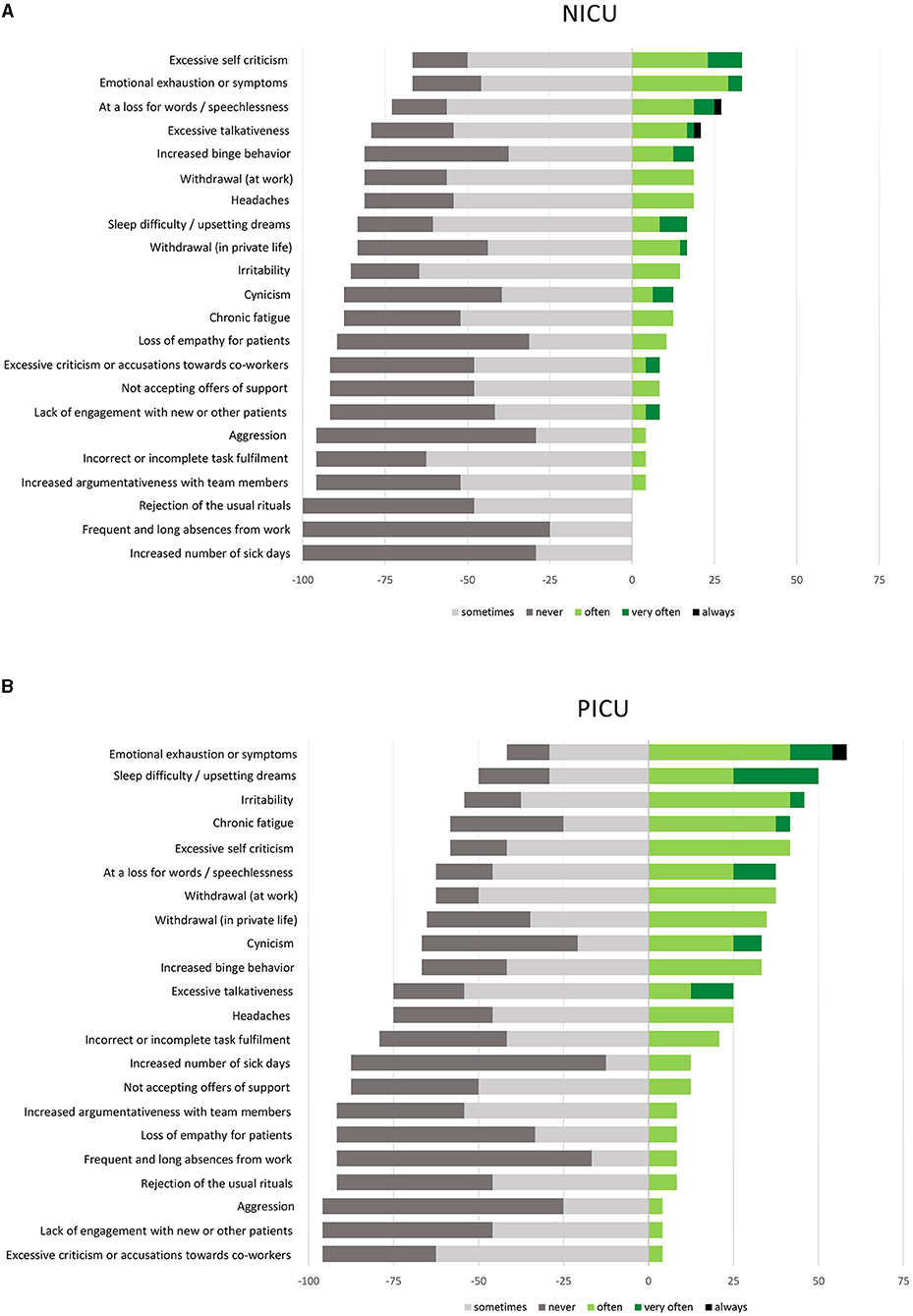

A list of 22 distress-related reactions or symptoms was presented and participants were asked to rate the frequency of each item using a five-point Likert scale with options “always” and “never” as the two extremes. The most frequent (rated as “often,” “very often,” or “always”) distress-related reactions or symptoms reported by NICU nurses were: (i) “Excessive self-criticism” (33.3%), (ii) “Emotional exhaustion or symptoms” (33.3%), and (iii) “Speechlessness” (27.2%). PICU nurses identified “Emotional exhaustion or symptoms” (58.4%), “Sleep difficulty/upsetting dreams” (50.0%), and “Irritability” (both 45.9%) as most frequent distress-related reactions or symptoms. No significant differences in frequency of self-reported distress-related symptoms as a result of end-of-life care were found.

Self-reported most frequent distress-related reactions or symptoms as a result of end-of-life care by NICU und PICU staff are summarize in Figures 2A,B.

Figure 2. Most frequent distress-related reactions or symptoms as self reported by (A) NICU staff and by (B) PICU staff (%). All questions to be rated by using a five-point Likert Scale.

Coping Mechanisms in End-of-Life Care

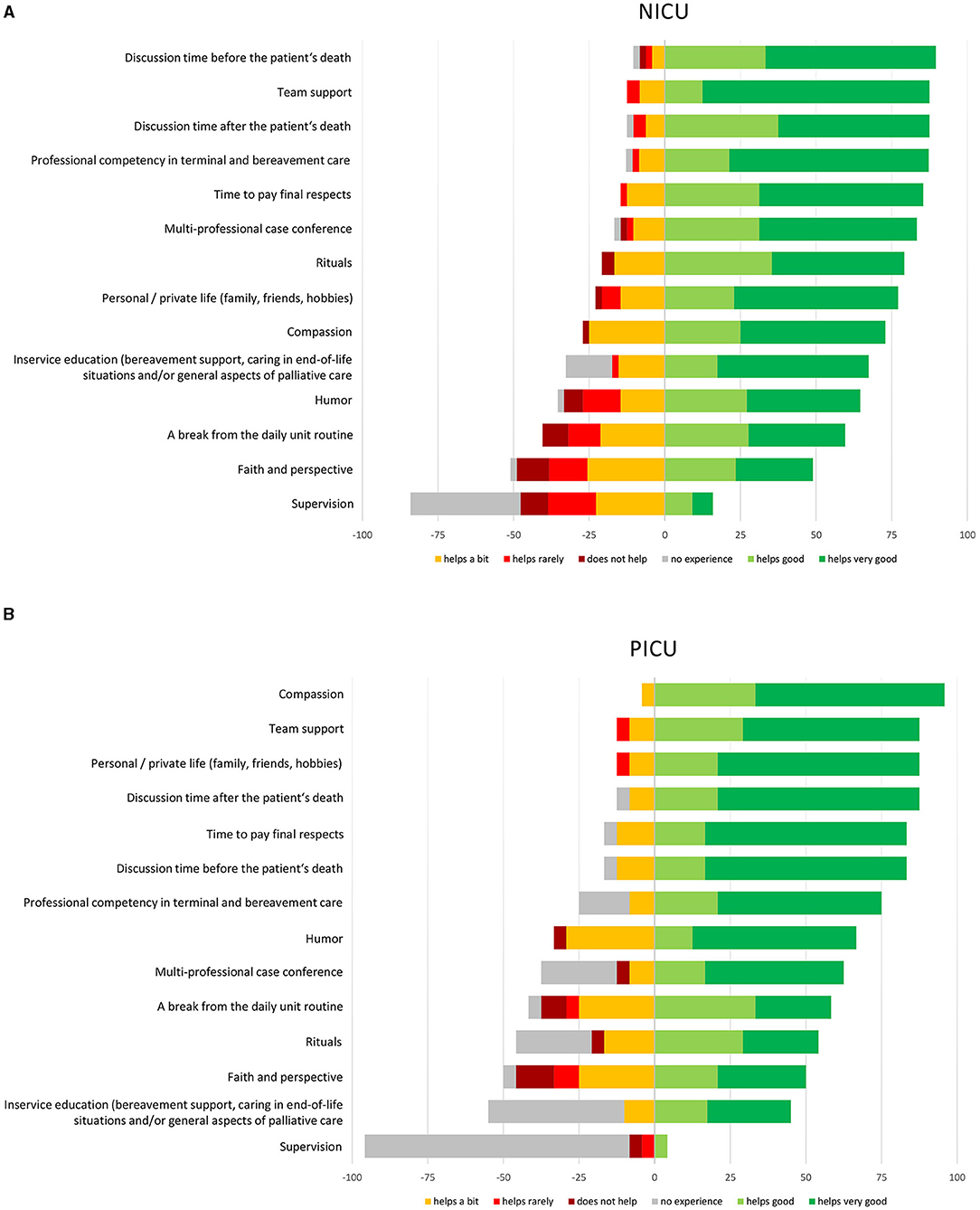

A list of 15 helpful mechanisms for coping in or after end-of-life care situations was presented and participants were asked to rate the efficacy of each item using a five-point Likert scale with options “helps very well” and “never helps” as the two extremes. In addition, also “not available/no experience” was an optional answer.

The mechanisms rated as most helpful (rated as “helps good” or “helps very good”) for coping in or after end-of-life care situations reported by NICU nurses were: “discussion time before the patient's death” (89.6%), “team support” (87.5%), and “discussion time after the patient's death” (87.5%). PICU nurses identified “compassion” (98.8%), “team support”, “personal/private life (family, friends, hobbies)”, and “discussion time after the patient's death” (all 87.5%) as the most helpful coping mechanisms. Self-reported most helpful coping mechanisms in or after end-of-life care situations by NICU und PICU staff are shown in detail in Figures 3A,B.

Figure 3. Coping mechanisms in end-of-life care as self reported by (A) NICU staff and by (B) PICU staff (%). All questions to be rated by using a six-point Likert Scale.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first cross-sectional survey in tertiary neonatal and pediatric intensive care units in Germany investigating and comparing nurses' perceived care-related distress and experiences in end-of-life situations.

There was no difference in the distress factors to which the nurses felt most frequently exposed. Both neonatal and pediatric nurses identified “staff shortages” as the most prominent factor. The nurses at the PICUs additionally identified this as the source of their greatest personal distress. The NICU nurses, however, ranked “lack of staff and time” as fourth among the “self-reported most distressing factors in end-of-life care situations”.

The NICU nurses, however, felt the greatest personal distress when the precise treatment goal for the patients they cared for had not been clearly defined, for example, due to the unclear prognosis.

In contrast, this factor was only named by one PICU nurse. The issue of changing therapeutic goals during the process of inpatient intensive care thus seems to be NICU-specific. In a previous study (36), we found that 4/5 neonatal palliative patients investigated (n = 149) were initially treated with a curative therapeutic goal. Only in the course of treatment did the therapeutic goal change from curative to palliative. In comparison, the proportion of pediatric patients converting from an initially curative treatment approach to a subsequent palliative therapeutic goal as a proportion of the total pediatric palliative population lies at ~25–33% (37, 38).

With regard to symptoms in childhood end-of-life care situations no differences could be found in the personal distress assessment by the nurses. Inadequately treated pain and dyspnea were named as most distressing factors in end-of-life care situations by both NICU and PICU nurses.

Distress-related personal symptoms as a result of end-of-life care were commonly reported by German NICU and PICU nurses. The overall frequency of self-reported symptoms was not significantly different in both groups. Coping with distress in end-of-life situations was best facilitated by having enough time for communication with parents and within the team, and by receiving collegial support and empathy from coworkers or family/friends. When available, in-service education was rated as helpful or very helpful by nearly all NICU and PICU nurses. In nursing education, information on psychological distress related to children's deaths and bereavement care should be conveyed from the early stage.

There are two main limitations to this questionnaire study. First, reporting bias is difficult to totally prevent or estimate. Second, we present data from a single center and cannot be sure that our findings are applicable to the entire population outside of our institution.

In conclusion, distress-related personal symptoms as a result of end-of-life care were commonly reported by German NICU and PICU nurses. The most frequent and distressing factors in end-of-life situations might be reduced by improving institutional/organizational factors (e.g., appropriate levels of staffing and provision of sufficient time for communication). However, addressing the specific professional, moral and emotional consequences of redirection of care seems to be a more relevant issue for the relief of distress associated end-of-life situations in the NICU compared to the PICU.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be provided to researchers with a project approved by an institutional review board after consultation with the data protection officer.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board (Ethikkommission der Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, #EA2/060/14). By voluntarily sending the anonymous self-report questionnaire survey back to the research group the participants provided consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

LG, AD, and CB conceptualized the study and analyzed the data. LG, AD, TR, and AP collected the data. LG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and critically reviewed and contributed to the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin. LG is participant in the BIH-Charité Clinical Fellows Program funded by the Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the nurses of the participating NICUs and PICUs for their help and cooperation in this research. We would like to thank Stephanie Scileppi for language editing and Boris Metze for statistical advice.

Abbreviations

NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PICU, pediatric intensive care; ICU, intensive care.

References

1. Kenner C, Press J, Ryan D. Recommendations for palliative and bereavement care in the NICU: a family-centered integrative approach. J Perinatol. (2015) 35 (Suppl. 1):S19–23. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.145

2. Carter BS. Pediatric palliative care in infants and neonates. Children. (2018) 5:21. doi: 10.3390/children5020021

3. Copanitsanou P, Fotos N, Brokalaki H. Effects of work environment on patient and nurse outcomes. Br J Nurs. (2017) 26:172–6. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2017.26.3.172

4. Kunaviktikul W, Wichaikhum O, Nantsupawat A, Nantsupawat R, Chontawan R, Klunklin A, et al. Nurses' extended work hours: patient, nurse and organizational outcomes. Int Nurs Rev. (2015) 62:386–93. doi: 10.1111/inr.12195

5. McClendon H, Buckner EB. Distressing situations in the intensive care unit: a descriptive study of nurses' responses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. (2007) 26:199–206. doi: 10.1097/01.DCC.0000286824.11861.74

6. Whitehead PB, Herbertson RK, Hamric AB, Epstein EG, Fisher JM. Moral distress among healthcare professionals: report of an institution-wide survey. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2015) 47:117–25. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12115

7. Price DM, Strodtman L, Montagnini M, Smith HM, Miller J, Zybert J, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care education needs of nurses across inpatient care settings. J Contin Educ Nurs. (2017) 48:329–36. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20170616-10

8. Altaker KW, Howie-Esquivel J, Cataldo JK. Relationships among palliative care, ethical climate, empowerment, and moral distress in intensive care unit nurses. Am J Crit Care. (2018) 27:295–302. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2018252

9. Vachon ML. Staff stress in hospice/palliative care: a review. Palliat Med. (1995) 9:91–122. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900202

10. Hawkins AC, Howard RA, Oyebode JR. Stress and coping in hospice nursing staff. The impact of attachment styles. Psychooncology. (2007) 16:563–72. doi: 10.1002/pon.1064

11. Burns JP, Mitchell C, Griffith JL, Truog RD. End-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: attitudes and practices of pediatric critical care physicians and nurses. Crit Care Med. (2001) 29:658–64. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00036

12. Carter BS, Howenstein M, Gilmer MJ, Throop P, France D, Whitlock JA. Circumstances surrounding the deaths of hospitalized children: opportunities for pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. (2004) 114:e361–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0654-F

13. Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen HJ. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. (2004) 114:1248–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0857-L

14. Doorenbos A, Lindhorst T, Starks H, Aisenberg E, Curtis JR, Hays R. Palliative care in the pediatric ICU: challenges and opportunities for family-centered practice. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. (2012) 8:297–315. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2012.732461

15. Garros D, Rosychuk RJ, Cox PN. Circumstances surrounding end of life in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. (2003) 112:e371. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.e371

16. Lee KJ, Dupree CY. Staff experiences with end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Palliat Med. (2008) 11:986–90. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0283

17. McCluggage H-L. Symptoms suffered by life-limited children that cause anxiety to UK children's hospice staff. Int J Palliat Nurs. (2006) 12:254–8. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2006.12.6.21450

18. Rodríguez-Rey R, Palacios A, Alonso-Tapia J, Pérez E, Álvarez E, Coca A, et al. Burnout and posttraumatic stress in paediatric critical care personnel: prediction from resilience and coping styles. Aust Crit Care. (2019) 32:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2018.02.003

19. Cavaliere TA, Daly B, Dowling D, Montgomery K. Moral distress in neonatal intensive care unit RNs. Adv Neonatal Care. (2010) 10:145–56. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e3181dd6c48

20. Cavinder C. The relationship between providing neonatal palliative care and nurses' moral distress: an integrative review. Adv Neonatal Care. (2014) 14:322–8. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000100

21. Cortezzo DE, Sanders MR, Brownell EA, Moss K. End-of-life care in the neonatal intensive care unit: experiences of staff and parents. Am J Perinatol. (2015) 32:713–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1395475

22. Dombrecht L, Cohen J, Cools F, Deliens L, Goossens L, Naulaers G, et al. Psychological support in end-of-life decision-making in neonatal intensive care units: Full population survey among neonatologists and neonatal nurses. Palliat Med. (2020) 34:430–4. doi: 10.1177/0269216319888986

23. Fortney CA, Pratt M, Dunnells ZDO, Rausch JR, Clark OE, Baughcum AE, et al. perceived infant well-being and self-reported distress in neonatal nurses. Nurs Res. (2020) 69:127–32. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000419

24. Kain VJ. Moral distress and providing care to dying babies in neonatal nursing. Int J Palliat Nurs. (2007) 13:243–8. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2007.13.5.23495

25. Kim S, Savage TA, Song M-K, Vincent C, Park CG, Ferrans CE, et al. Nurses' roles and challenges in providing end-of-life care in neonatal intensive care units in South Korea. Appl Nurs Res. (2019) 50:151204. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151204

26. Klein SD, Bucher HU, Hendriks MJ, Baumann-Hölzle R, Streuli JC, Berger TM, et al. Sources of distress for physicians and nurses working in Swiss neonatal intensive care units. Swiss Med Wkly. (2017) 147:w14477. doi: 10.4414/smw.2017.14477

27. Lewis SL. Exploring NICU nurses' affective responses to end-of-life care. Adv Neonatal Care. (2017) 17:96–105. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000355

28. Sannino P, Giannì ML, Re LG, Lusignani M. Moral distress in the neonatal intensive care unit: an Italian study. J Perinatol. (2015) 35:214–7. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.182

29. Dryden-Palmer K, Moore G, McNeil C, Larson CP, Tomlinson G, Roumeliotis N, et al. Moral distress of clinicians in canadian pediatric and neonatal ICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2020) 21:314–23. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002189

30. Larson CP, Dryden-Palmer KD, Gibbons C, Parshuram CS. Moral distress in PICU and neonatal ICU practitioners: a cross-sectional evaluation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2017) 18:e318–26. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001219

31. Field D, Deeming J, Smith LK. Moral distress: an inevitable part of neonatal and paediatric intensive care? Arch Dis Child. (2016) 101:686–7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310268

32. Prentice T, Janvier A, Gillam L, Davis PG. Moral distress within neonatal and paediatric intensive care units: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. (2016) 101:701–8. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309410

33. Barnes K. Staff stress in the children's hospice: causes, effects and coping strategies. Int J Palliat Nurs. (2001) 7:248–54. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2001.7.5.12638

34. Downey V, Bengiamin M, Heuer L, Juhl N. Dying babies and associated stress in NICU nurses. Neonatal Netw. (1995) 14:41–6.

35. Müller, M, Pfister, D. (2014). [Wie Viel Tod Verträgt das Team?: Belastungs- und Schutzfaktoren in Hospizarbeit und Palliativmedizin] - in German. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Germany.

36. Garten L, Ohlig S, Metze B, Bührer C. Prevalence and characteristics of neonatal comfort care patients: a single-center, 5-year, retrospective, observational study. Front Pediatr. (2018) 6:221. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00221

37. Bender HU, Riester MB, Borasio GD, Führer M. Let's bring her home first. Patient characteristics and place of death in specialized pediatric palliative home care. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2017) 54:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.006

Keywords: palliative care, newborn, children, intensive care unit, nurse, stress

Citation: Garten L, Danke A, Reindl T, Prass A and Bührer C (2021) End-of-Life Care Related Distress in the PICU and NICU: A Cross-Sectional Survey in a German Tertiary Center. Front. Pediatr. 9:709649. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.709649

Received: 14 May 2021; Accepted: 27 August 2021;

Published: 24 September 2021.

Edited by:

Quen Mok, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust, United KingdomReviewed by:

Pavla Pokorna, Charles University, CzechiaRuth Gottstein, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT), United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Garten, Danke, Reindl, Prass and Bührer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lars Garten, bGFycy5nYXJ0ZW5AY2hhcml0ZS5kZQ==

Lars Garten

Lars Garten Andrea Danke1,2

Andrea Danke1,2 Christoph Bührer

Christoph Bührer