Abstract

Background:

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a rare inheritable disorder characterized by bone marrow failure and mucocutaneous triad (reticular skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and oral leukoplakia). Dyskeratosis congenita 1 (DKC1) is responsible for 4.6% of the DC with an X-linked inheritance pattern. Almost 70 DKC1 variations causing DC have been reported in the Human Gene Mutation Database.

Results:

Here we described a 14-year-old boy in a Chinese family with a phenotype of abnormal skin pigmentation on the neck, oral leukoplakia, and nail dysplasia in his hands and feet. Genetic analysis and sequencing revealed hemizygosity for a recurrent missense mutation c.1156G > A (p.Ala386Thr) in DKC1 gene. The heterozygous mutation (c.1156G > A) from his mother and wild-type sequence from his father were obtained in the same site of DKC1. This mutation was determined as disease causing based on silico software, but the pathological phenotypes of the proband were milder than previously reported at this position (HGMDCM060959). Homology modeling revealed that the altered amino acid was located near the PUA domain, which might affect the affinity for RNA binding.

Conclusion:

This DKC1 mutation (c.1156G > A, p.Ala386Thr) was first reported in a Chinese family with mucocutaneous triad phenotype. Our study reveals the pathogenesis of DKC1 c.1156G > A mutation to DC with a benign phenotype, which expands the disease variation database, the understanding of genotype–phenotype correlations, and facilitates the clinical diagnosis of DC in China.

Introduction

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a rare inheritable disorder characterized by bone marrow failure and mucocutaneous triad (skin pigmentation, dystrophy nails, oral leukoplakia) (1). So far, several genes have been identified to be associated with DC, including dyskeratosis congenita 1 (DKC1), CTS telomere maintenance complex component 1 (CTC1), regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1 (RTEL1), TERF 1-interacting nuclear factor 2 (TINF2), telomerase RNA component (TERC), telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), adrenocortical dysplasia homolog (ACD), NHP2 ribonucleoprotein (NHP2), NOP 10 ribonucleoprotein (NOP10), poly(A)-specific ribonuclease (PARN), nuclear assembly factor 1 (NAF1), and WD repeat containing antisense to TP53 (TCAB1), and DKC1 is responsible for 4.6% of the DC (2, 3). Almost 70 dyskeratosis congenita 1 (DKC1) variations causing DC have been reported in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD1); the gene encoding a nucleolar protein is called dyskerin, which is involved in both ribosome biogenesis (4) and telomere maintenance (5). Here, we found a DC patient in a Chinese family. The clinical data of the patient and literature review of DC are described.

Case Presentation

Clinical Manifestations and Family History

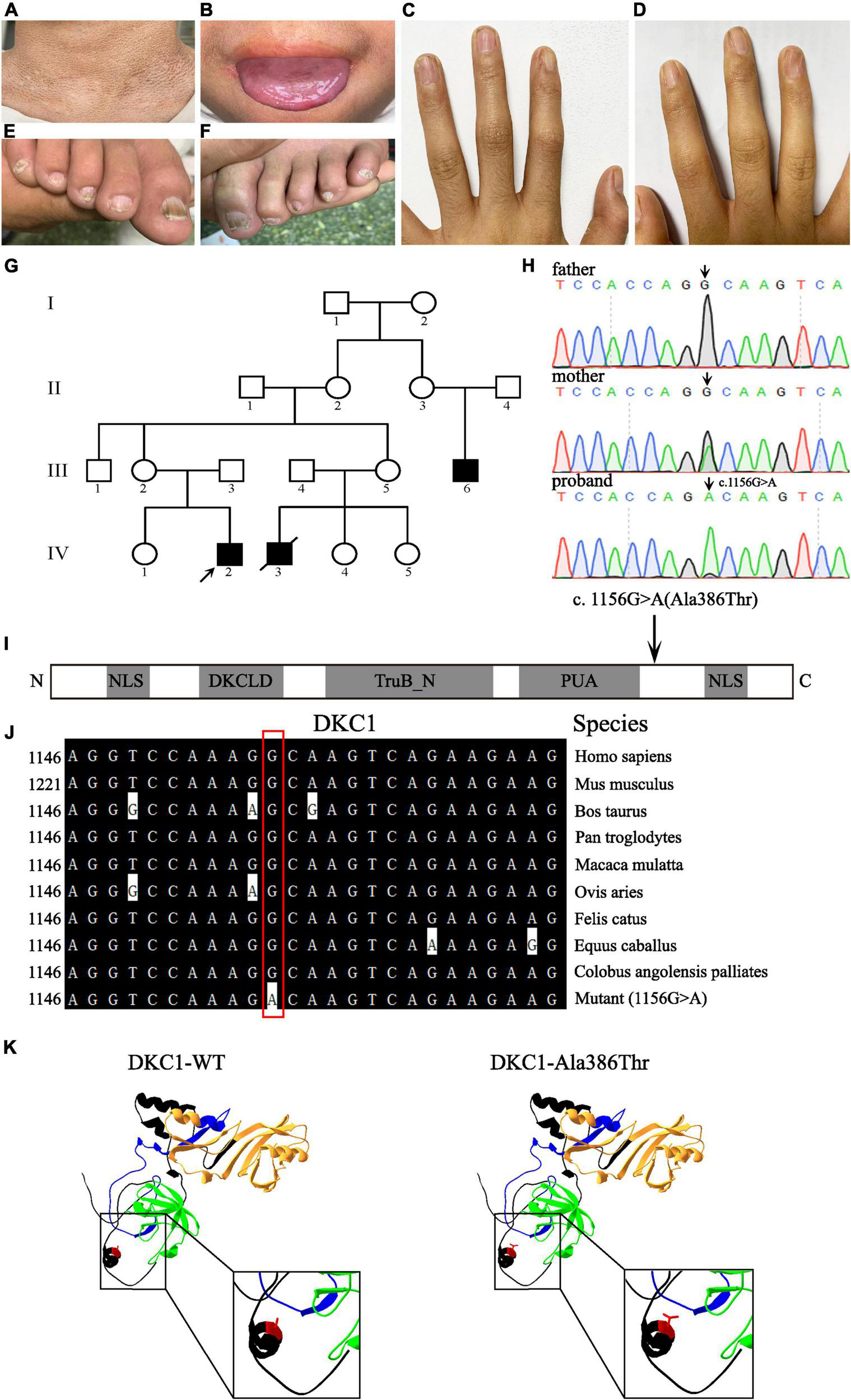

Three affected males (III-6, IV-2, and IV-3) and 14 unaffected individuals are involved in this family and are recruited from Shanxi Province, China (Figure 1G). The proband IV-2 is a 14-year-old boy with abnormal skin pigmentation on the neck (Figure 1A), oral leukoplakia (Figure 1B), and nail dysplasia on his hands and feet (Figures 1C–F). III-6 presents with similar phenotypes. II-2, II-3, III-2, and III-5 are mutation carriers without any mild signs of congenital dyskeratosis.

FIGURE 1

Clinical features of the proband and pedigree, sequencing analysis, and DKC1 mutation investigations. Pigmentation on the neck (A), mucosal leukoplakia on the tongue (B), finger nail ridging, toenail ridging, and longitudinal splitting (C–F) in the proband. (G) The pedigree of the family. The arrow indicates the proband. (H) Sequencing chromatograms show the proband with a hemizygous mutation DKC1 c.1156G > A, the proband’s mother with the same heterozygous mutation; the black arrow indicates the position of the nucleotide mutation. (I) A linear representation of the DKC1 protein shows the location of the N-terminal nuclear localization signals (NLS), DKCLD, TruB_N, and PUA domains. The black arrow shows the positions of the amino acid substitutions. (J) The mutant site (c.1156G > A) of DKC1 is highly conserved phylogenetically among the indicated species. (K) The mutant proteins were structured by the Swiss-Model online software and compared with the wild type. Ribbon representation of the human DKC1 and map of the studied variant localization obtained by homology modeling analysis. The wild-type and mutant monomers are shown in black; DKCLD, TruB_N, and PUA domains are shown in blue, orange, and green, respectively. Amino acid Ala386 is shown as red.

Sequencing Analysis of the Patient and His Family

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) data were functionally annotated and filtered using cloud-based rare disease NGS analysis platform,2 based on the Ensembl (GRCh37/hg19), dbSNP, EVS, 1000 genome, ExAC, and GnomAD databases. Exonic sequence alterations and intronic variants at exon–intron boundaries, with unknown frequency or minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1% and not present in the homozygous state in those databases, were retained. Filtering was performed for variants in genes associated with DC. Then the only DC-related gene mutation DKC1 mutation (c.1156G > A, p.Ala386Thr) was identified.

Peripheral blood samples were collected from this family, which includes three individuals (III-2, III-3, and IV-2); a recurrent DKC1 hemizygous mutation (c.1156G > A) in exon 12 was confirmed in the proband (IV-2) by using Sanger sequencing (Figure 1H). Furthermore, a heterozygous mutation (c.1156G > A) in his mother (III-2) and a wild-type sequence in his father (III-3) were obtained on the same site of DKC1 (Figure 1H). The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. These data can be found here: ClinVar Wizard Submission ID: SUB11097305; Accession: SCV002097631.

Pathogenicity Prediction of Variant

The effect of the missense variant was computationally analyzed by four prediction programs: Mutation Taster, SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and PROVEAN. The outcomes are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Mutation prediction | Prediction score values |

|||

| Tool | Mutation Taster | SIFT | PolyPhen-2 | PROVEAN |

| c.1156G > A | D (0.99) | D (0.02) | B (0.122) | D (−3.121) |

Bioinformatics prediction of a pathogenic variant.

Mutation Taster: D, disease causing; P, polymorphism.

SIFT: D, damaging; T, tolerated.

PolyPhen-2: D, probably damaging; P, possibly damaging; B, benign.

PROVEAN: D, deleterious; N, neutral.

Molecular Analysis

Evolutionary conservation of amino acid residue showed that the impaired amino acid residues Ala386 were highly conserved in different species (Figure 1J). The eukaryotic DKC1 protein presents three well-characterized domains: DKCLD (amino acids 49–106), TruB_N (amino acids 107–247), and PUA (amino acids 297–371) besides nuclear and nucleolar localization signals (amino acids 11–20; 446–458) (6, 7). Bioinformatic and biochemical assessment on the effect of the altered amino acid on the functions of DKC1 shows that the missense mutation was concentrated near the PUA domain (Figures 1I,K), which is crucial for the RNA binding of telomerase (7). DKC1 mutations concentrated in or near the PUA domain decrease the affinity for RNA binding (6). In conclusion, the recurrent DKC1 pathogenic variant was identified by WES and Sanger sequencing in a Chinese DC family.

Discussion

Here, we report a case of DC in a Chinese pedigree with a mutation c.1156G > A (p.Ala386Thr) in DKC1. The affected amino acids are located near the PUA kinase domain from the linear structure, indicating that the mutation might result in defect on the affinity for RNA binding (6). Evolutionary conservation analysis of amino acid residue showed that the amino acid residue Ala386 is highly conserved among DKC1 protein from different species, indicating that the mutation is likely pathological.

We have reviewed articles describing cases of DC using the Human Gene Mutation Database and NCBI—PubMed, with the search term “dyskeratosis congenita” from January 1998 to November 2021 (Table 2). Among the studies, we identified 74 variations in DKC1 with 85 individuals for analysis. Most publications were case reports so that the clinical data were not comprehensive. There were 87.5% male patients, 12.5% female patients, and 29 patients without gender description in the patients, indicating that males were the dominant patients of DC.

TABLE 2

| Mutation on cDNA/protein | Ethnic origin | Gender | Age (years) | Mucocutaneous triad | Bone marrow failure | Anemia | Thrombocytopenia | Telomere shortening | Pulmonary fibrosis | References |

| 5C > T/A2V | Egyptian | Male | 40 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | + | (8) |

| 29C > T/P10L | - | - | - | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| 91C > A/Q31K | Japan | Male | 11 | + | NT | NT | + | NT | NT | (9) |

| 91C > G/Q31E | United States | Male | 33 | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | (10) |

| 106T > G/F36Y | Belgian | Male | 30 | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | (11) |

| 113T > C/I38T | Italy | Male | 0.75 | + | + | + | NT | NT | NT | (11) |

| 114C > G/I38M | United Kingdom | - | - | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (12) |

| 115A > G/K39E | United Kingdom | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| 119C > G/P40R | United Kingdom | Male | 14 | + | NT | NT | NT | - | - | (14) |

| 121G > A/E41K | Turkey | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| 127A > G/K43E | Germany | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (15) |

| 146C > T/T49M | United Kingdom | Male | 3 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (16) |

| 2.6 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (16) | |||

| 5 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (16) | |||

| 145A > T/T49S | United States | Male | 49 | NT | + | + | + | + | + | (1) |

| Female | 25 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (1) | ||

| 160C > G/L54V | United States | Female | 65 | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | (17) |

| Female | 65 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (17) | ||

| Male | 45 | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | (17) | ||

| 166_167invCT/L56S | Russian | Male | 14 | + | NT | + | + | NT | NT | (18) |

| 189T > G/N63K | Canada | Male | 24 | + | + | + | + | + | + | (19) |

| 194G > A/R65K | Japan | Male | 46 | + | + | NT | NT | + | + | (20) |

| 194G > C/R65T | Germany | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| 198A > G/T66A | United States | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| 200C > T/T67I | - | - | - | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| 204C > A/H68Q | - | - | - | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| 203A > G/H68R | Spain | Male | 36 | + | NT | + | + | NT | NT | (21) |

| 202C > T/H68Y | United States | Male | - | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (12) |

| 209C > T/T70I | United States | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (22) |

| 214C > T/L72F | China | Male | 7 | + | + | + | + | NT | NT | (23) |

| 227C > T/S76L | United States | - | - | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (12) |

| 361A > G/S121G | United Kingdom | Male | 1.5 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (16) |

| 247C > T/R158W | United States | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (24) |

| 838A > C/S280R | United States | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (24) |

| 911G > A/S304N | United States | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (25) |

| 941A > G/K314R | - | - | - | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| 942G > A/K314K | United States | Male | 65 | NT | + | NT | + | + | + | (26) |

| 949C > G/L317V | United States | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (25) |

| 949C > T/L317F | Germany | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (27) |

| 961C > A/L321I | China | Male | 4.3 | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | (28) |

| 961C > G/L321V | Italy | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| 965G > A/R322Q | Germany | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (27) |

| 1049T > C/M350T | United Kingdom | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| 1050G > A/M350I | Austria | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| 1050G > C/M350I | Germany | Male | 40 | + | NT | + | + | NT | NT | (29) |

| 1051A > G/T351A | - | Male | 7 | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | (30) |

| 1054A > G/T352A | - | Male | 31 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (3) |

| 1058C > T/A353V | Brazil | Male | 3 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | (31) |

| India | Male | 12 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (32) | |

| 1066T > C/S356P | Portugal | Male | 15 | + | NT | NT | + | NT | NT | (33) |

| 10 | + | + | NT | + | NT | NT | (33) | |||

| 1069A > G/T357A | Japan | Male | 10 | + | + | + | + | NT | NT | (9) |

| 1072T > G/C358G | Germany | Male | 0.6 | + | NT | NT | + | NT | NT | (34) |

| 1075G > A/D359N | - | - | - | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| 1133G > A/R378Q | United States | - | - | NT | + | NT | NT | + | NT | (12) |

| 1151C > T/P384L | United States | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (24) |

| 1156G > A/A386T | - | - | - | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| 1186G > A/K390Q | United States | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (22) |

| 1177A > T/I393F | India | Male | 21 | + | NT | + | NT | + | NT | (35) |

| 1193T > C/L398P | Japan | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (36) |

| 1204G > A/G402R | India | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| 1205G > A/G402E | United States | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (37) |

| 1213A > G/T405A | United States | Male | 65 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | + | (38) |

| 69 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | + | (38) | |||

| 1223C > T/T408I | - | - | - | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| 1226C > G/P409R | United States | Male | 46 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (1) |

| Male | 40 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (1) | ||

| Female | 16 | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | (1) | ||

| Female | 16 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (1) | ||

| Female | 8 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (1) | ||

| China | Male | 24 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (7) | |

| 20 | + | NT | NT | + | NT | NT | (7) | |||

| 1226C > TP409L | China | Male | 20 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (39) |

| IVS1 ds592C_G | Belgium | Male | 30 | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | (24) |

| 10 | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT | (24) | |||

| 56 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | + | (24) | |||

| IVS2 as-15 T-C | China | Male | 8 | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (40) |

| IVS2 as-5 C-G | Spain | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (13) |

| IVS12 ds + 1 G-A/A386fsX1 | Italy | Male | 0.3 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (41) |

| IVS14 as-2 A-G | - | - | - | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| -141C > G | Spanish | Male | 13 | NT | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | (24, 42) |

| -141C > G | United States | - | 2 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | + | (22) |

| 103_105delGAA/E35del | United States | Female | 10 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (17) |

| 106_108delCTT/L36del | Caucasian | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (37) |

| 1168_1170delAAG/K390del | Spanish | Male | 32 | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (21) |

| 1495_1497delAAG/K499del | United Kingdom | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (43) |

| 112_116delATCAAinsTCAAC/ T38SfsX31 |

Canada | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (44) |

| 14_215CT > TA/L72Y | United Kingdom | Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (37) |

| 1258,1259AG > TA/S420Y | - | - | - | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4) |

| Duplication of ∼14 kb (described at genomic DNA level) | United States | Male | - | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (45) |

| 1493A > G/S485G | Germany | - | - | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | (46) |

Main clinical features of dyskeratosis congenita (DC) patients in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD)/literature.

+, presents positive expression; NT, presents negative expression; -, presents not in detail.

We find that the clinical symptoms of these DC patients are varied, but skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, mucosal leukoplakia, and bone marrow failure are the most classic symptoms in patients. In this analysis, the incidence of skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and mucosal leucoplakia are nearly 86.58, 78.048, and 64.63%, respectively. Moreover, apart from the mucocutaneous triad, anemia can be another routine clinical sign of DC. Missense mutation is the most common mutation type among all the variations and shows higher incidence of the typical clinical symptoms of DC, but only one patient with c.194G > C (p.R65K) had mild symptoms such as pulmonary symptoms (20). The patient with mutation of small indel (c.166_167invCT) only suffer from thrombocytopenia and anemia (18). The patients with mutations of regulatory (c.-142C > G or c.-141C > G) only suffer from short telomere or pulmonary fibrosis (22, 24).

We also found 13 variants of DKC1 in Asia with 100% male (7, 9, 13, 20, 23, 28, 32, 35, 36, 40), 52 variants in non-Asia with 84.8% male (1, 8, 10–14, 16–19, 21, 24–26, 29, 31, 33, 34, 37, 38, 41, 42, 44, 45), and 10 variants with unknown nationality (3, 4, 30). Asians develop DC at a younger age than non-Asians, between 4.3 and 46 years old (1, 7–12, 14, 16–24, 26, 28, 29, 31–35, 38–42). The incidence of the mucocutaneous triad (skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and mucosal leukoplakia), bone marrow failure, thrombocytopenia, and telomere shortening in Asia are similar to that of non-Asia (Table 3; 1, 3, 4, 7–12, 14, 16–24, 26, 28–35, 38–42, 45, 46). However, the DC-Asians are more likely to develop anemia instead of pulmonary fibrosis than non-Asians apart from the mucocutaneous triad (Table 3; 1, 3, 4, 7–12, 14, 16–24, 26, 28–35, 38–42, 45, 46). Unfortunately, the patient involved in our study did not present with anemia; the reason could be due to the lower incidence (35.7%) of anemia in Asian DC population.

TABLE 3

| Mutation percent | Age (year) | Male | Mucocutaneous triad | Bone marrow failure | Anemia | Thrombocytopenia | Telomere shortening | Pulmonary fibrosis |

| Asian (19.07%) | 4.3–46 | 100% | 78.57% | 35.7% | 35.7% | 28.57% | 14.28% | 7.17% |

| Outside Asian (81.11%) | 0.3–69 | 84.09% | 70.59% | 37.5% | 19.6% | 27.45% | 13.72% | 23.53% |

The Asian and outside Asian variations and the main clinical phenotypes.

The DKC1 variation of c.1156G > A (p.Ala386Thr) was also reported from a DCR216-family in 2006 (4). The patient presents both the features of classic DC and Hoyeraal Hreidarsson (HH) syndrome, including intrauterine growth retardation, developmental delay, microcephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia, immunodeficiency, or bone marrow failure (4). However, the patient involved in our study only presents with benign phenotype of the mucocutaneous triad without any other abnormality, which provides more information on the mutation phenotype spectrum of DC. A similar case occurs for the DKC1 c.1226C > G (p.P409R) mutation. This mutation was first identified in the patient with the features of liver cirrhosis, frequent caries, low platelets, gray hair, and tongue cancer in 2013 (1). However, the patient with the same mutation was reported from China in 2020 presenting fewer symptoms of reticulate interspersed pigmentation with hypopigmented macules on the neck, fingernail ridging and longitudinal splitting, and mucosal leukoplakia on the tongue (7). Those results demonstrate that there is no specific relationship between the genotype and phenotype.

Our findings indicate DKC1 missense mutation c.1156G > A leads to a benign phenotype, which expands the disease variation database, the understanding of genotype–phenotype correlations, and facilitates the clinical diagnosis of DC in China. However, the mechanism of DKC1 mutation resulting in DC should be investigated further.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: Clinvar [accession: SCV002097631].

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Shanxi University (SXULL2021080). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LW wrote the manuscript and performed the practical work. JL collected patients’ data. PL and QX analyzed the patients’ data. PL designed the study. Y-AZ, PL, and CW conceived the study and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (82070691), Fund Program for the Scientific Activities of Selected Returned Overseas Professionals in Shanxi Province (20210034), and the Central Guidance on Local Science and Technology Development Fund of Shanxi Province (YDZJSX2021B001).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

Alder JK Parry EM Yegnasubramanian S Wagner CL Lieblich LM Auerbach R et al Telomere phenotypes in females with heterozygous mutations in the dyskeratosis congenita 1 (DKC1) gene. Hum Mutat. (2013) 34:1481–5. 10.1002/humu.22397

2.

AlSabbagh MM. Dyskeratosis congenita: a literature review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2020) 18:943–67. 10.1111/ddg.14268

3.

Ratnasamy V Navaneethakrishnan S Sirisena ND Grüning NM Brandau O Thirunavukarasu K et al Dyskeratosis congenita with a novel genetic variant in the DKC1 gene: a case report. BMC Med Genet. (2018) 19:85. 10.1186/s12881-018-0584-y

4.

Vulliamy TJ Marrone A Knight SW Walne A Mason PJ Dokal I. Mutations in dyskeratosis congenita: their impact on telomere length and the diversity of clinical presentation. Blood. (2006) 107:2680–5. 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2622

5.

Mitchell JR Cheng J Collins K. A box H/ACA small nucleolar RNA-like domain at the human telomerase RNA 3’ end. Mol Cell Biol. (1999) 19:567–76. 10.1128/mcb.19.1.567

6.

Cerrudo CS Mengual Gómez DL Gómez DE Ghiringhelli PD. Novel insights into the evolution and structural characterization of dyskerin using comprehensive bioinformatics analysis. J Proteome Res. (2015) 14:874–87. 10.1021/pr500956k

7.

Zhao XY Zhong WL Zhang J Ma G Hu H Yu B. Dyskeratosis congenita with DKC1 mutation: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. (2020) 65:426–7. 10.4103/ijd.IJD_716_18

8.

Safa WF Lestringant GG Frossard PM. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita: restrictive pulmonary disease and a novel mutation. Thorax. (2001) 56:891–4. 10.1136/thorax.56.11.891

9.

Kanegane H Kasahara Y Okamura J Hongo T Tanaka R Nomura K et al Identification of DKC1 gene mutations in Japanese patients with X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. Br J Haematol. (2005) 129:432–4. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05473.x

10.

Wong JM Kyasa MJ Hutchins L Collins K. Telomerase RNA deficiency in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. Hum Genet. (2004) 115:448–55. 10.1007/s00439-004-1178-7

11.

Devriendt K Matthijs G Legius E Schollen E Blockmans D van Geet C et al Skewed X-chromosome inactivation in female carriers of dyskeratosis congenita. Am J Hum Genet. (1997) 60:581–7.

12.

Vulliamy TJ Kirwan MJ Beswick R Hossain U Baqai C Ratcliffe A et al Differences in disease severity but similar telomere lengths in genetic subgroups of patients with telomerase and shelterin mutations. PLoS One. (2011) 6:e24383. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024383

13.

Knight SW Heiss NS Vulliamy TJ Greschner S Stavrides G Pai GS et al X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is predominantly caused by missense mutations in the DKC1 gene. Am J Hum Genet. (1999) 65:50–8. 10.1086/302446

14.

Connor JM Gatherer D Gray FC Pirrit LA Affara NA. Assignment of the gene for dyskeratosis congenita to Xq28. Hum Genet. (1986) 72:348–51. 10.1007/bf00290963

15.

Heiss NS Mégarbané A Klauck SM Kreuz FR Makhoul E Majewski F et al One novel and two recurrent missense DKC1 mutations in patients with dyskeratosis congenita (DKC). Genet Couns. (2001) 12:129–36.

16.

Knight SW Heiss NS Vulliamy TJ Aalfs CM McMahon C Richmond P et al Unexplained aplastic anaemia, immunodeficiency, and cerebellar hypoplasia (Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome) due to mutations in the dyskeratosis congenita gene, DKC1. Br J Haematol. (1999) 107:335–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01690.x

17.

Xu J Khincha PP Giri N Alter BP Savage SA Wong JM. Investigation of chromosome X inactivation and clinical phenotypes in female carriers of DKC1 mutations. Am J Hematol. (2016) 91:1215–20. 10.1002/ajh.24545

18.

Kurnikova M Shagina I Khachatryan L Schagina O Maschan M Shagin D. Identification of a novel mutation in DKC1 in dyskeratosis congenita. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2009) 52:135–7. 10.1002/pbc.21733

19.

Dvorak LA Vassallo R Kirmani S Johnson G Hartman TE Tazelaar HD et al Pulmonary fibrosis in dyskeratosis congenita: report of 2 cases. Hum Pathol. (2015) 46:147–52. 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.10.003

20.

Hisata S Sakaguchi H Kanegane H Hidaka T Shiihara J Ichinose M et al A novel missense mutation of DKC1 in dyskeratosis congenita with pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. (2013) 30:221–5.

21.

Carrillo J Martínez P Solera J Moratilla C González A Manguán-García C et al High resolution melting analysis for the identification of novel mutations in DKC1 and TERT genes in patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood Cells Mol Dis. (2012) 49:140–6. 10.1016/j.bcmd.2012.05.008

22.

Bellodi C McMahon M Contreras A Juliano D Kopmar N Nakamura T et al H/ACA small RNA dysfunctions in disease reveal key roles for noncoding RNA modifications in hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Cell Rep. (2013) 3:1493–502. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.030

23.

Hamidah A Rashid RA Jamal R Zhao M Kanegane H. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita in Malaysia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2008) 50:432. 10.1002/pbc.21203

24.

Knight SW Vulliamy TJ Morgan B Devriendt K Mason PJ Dokal I. Identification of novel DKC1 mutations in patients with dyskeratosis congenita: implications for pathophysiology and diagnosis. Hum Genet. (2001) 108:299–303. 10.1007/s004390100494

25.

Du HY Pumbo E Ivanovich J An P Maziarz RT Reiss UM et al TERC and TERT gene mutations in patients with bone marrow failure and the significance of telomere length measurements. Blood. (2009) 113:309–16. 10.1182/blood-2008-07-166421

26.

Gaysinskaya V Stanley SE Adam S Armanios M. Synonymous mutation in DKC1 causes telomerase RNA insufficiency manifesting as familial pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. (2020) 158:2449–57. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.025

27.

Rostamiani K Klauck SM Heiss N Poustka A Khaleghi M Rosales R et al Novel mutations of the DKC1 gene in individuals affected with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood Cells Mol Dis. (2010) 44:88. 10.1016/j.bcmd.2009.10.005

28.

Wan Y An WB Zhang JY Zhang JL Zhang RR Zhu S et al Clinical and genetic features of dyskeratosis congenital with bone marrow failure in eight patients. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. (2016) 37:216–20. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2016.03.008

29.

Kraemer DM Goebeler M. Missense mutation in a patient with X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. Haematologica. (2003) 88:Ecr11.

30.

Zeng T Lv G Chen X Yang L Zhou L Dou Y et al CD8(+) T-cell senescence and skewed lymphocyte subsets in young dyskeratosis congenita patients with PARN and DKC1 mutations. J Clin Lab Anal. (2020) 34:e23375. 10.1002/jcla.23375

31.

Donaires FS Alves-Paiva RM Gutierrez-Rodrigues F da Silva FB Tellechea MF Moreira LF et al Telomere dynamics and hematopoietic differentiation of human DKC1-mutant induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. (2019) 40:101540. 10.1016/j.scr.2019.101540

32.

Tamhankar PM Zhao M Kanegane H Phadke SR. Identification of DKC1 gene mutation in an Indian patient. Indian J Pediatr. (2010) 77:310–2. 10.1007/s12098-009-0300-1

33.

Coelho JD Lestre S Kay T Lopes MJ Fiadeiro T Apetato M. Dyskeratosis congenita–two siblings with a new missense mutation in the DKC1 gene. Pediatr Dermatol. (2011) 28:464–6. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01299.x

34.

Dehmel M Brenner S Suttorp M Hahn G Schützle H Dinger J et al Novel mutation in the DKC1 gene: neonatal Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome as a rare differential diagnosis in pontocerebellar hypoplasia, primary microcephaly, and progressive bone marrow failure. Neuropediatrics. (2016) 47:182–6. 10.1055/s-0036-1578799

35.

Mohanty P Jadhav P Shanmukhaiah C Kumar S Vundinti BR. A novel DKC1 gene mutation c.1177 A>T (p.I393F) in a case of dyskeratosis congenita with severe telomere shortening. Int J Dermatol. (2019) 58:1468–71. 10.1111/ijd.14424

36.

Yamaguchi H Sakaguchi H Yoshida K Yabe M Yabe H Okuno Y et al Clinical and genetic features of dyskeratosis congenita, cryptic dyskeratosis congenita, and Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome in Japan. Int J Hematol. (2015) 102:544–52. 10.1007/s12185-015-1861-6

37.

Heiss NS Knight SW Vulliamy TJ Klauck SM Wiemann S Mason PJ et al X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in a highly conserved gene with putative nucleolar functions. Nat Genet. (1998) 19:32–8. 10.1038/ng0598-32

38.

Kropski JA Mitchell DB Markin C Polosukhin VV Choi L Johnson JE et al A novel dyskerin (DKC1) mutation is associated with familial interstitial pneumonia. Chest. (2014) 146:e1–7. 10.1378/chest.13-2224

39.

Ding YG Zhu TS Jiang W Yang Y Bu DF Tu P et al Identification of a novel mutation and a de novo mutation in DKC1 in two Chinese pedigrees with dyskeratosis congenita. J Invest Dermatol. (2004) 123:470–3. 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23228.x

40.

Yuan SS Lu YD Wu CL Li HP Ge H Zhang YM. Clinical features and genotype analysis in a case of dyskeratosis congenita. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. (2015) 35:553–6.

41.

Pearson T Curtis F Al-Eyadhy A Al-Tamemi S Mazer B Dror Y et al An intronic mutation in DKC1 in an infant with Høyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. (2008) 146A:2159–61. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32412

42.

Del Brío Castillo R Bleesing J McCormick T Squires JE Mazariegos GV Squires J et al Successful liver transplantation in short telomere syndromes without bone marrow failure due to DKC1 mutation. Pediatr Transplant. (2020) 24:e13695. 10.1111/petr.13695

43.

van Schouwenburg PA Davenport EE Kienzler AK Marwah I Wright B Lucas M et al Application of whole genome and RNA sequencing to investigate the genomic landscape of common variable immunodeficiency disorders. Clin Immunol. (2015) 160:301–14. 10.1016/j.clim.2015.05.020

44.

Tsangaris E Klaassen R Fernandez CV Yanofsky R Shereck E Champagne J et al Genetic analysis of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes from one prospective, comprehensive and population-based cohort and identification of novel mutations. J Med Genet. (2011) 48:618–28. 10.1136/jmg.2011.089821

45.

Stray-Pedersen A Sorte HS Samarakoon P Gambin T Chinn IK Coban Akdemir ZH et al Primary immunodeficiency diseases: genomic approaches delineate heterogeneous mendelian disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2017) 139:232–45. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.042

46.

Bellodi C Krasnykh O Haynes N Theodoropoulou M Peng G Montanaro L et al Loss of function of the tumor suppressor DKC1 perturbs p27 translation control and contributes to pituitary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. (2010) 70:6026–35. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-09-4730

Summary

Keywords

dyskeratosis congenita syndrome, DKC1 , missense mutation, c.1156G > A, p.Ala386Thr

Citation

Wang L, Li J, Xiong Q, Zhou Y-A, Li P and Wu C (2022) Case Report: A Missense Mutation in Dyskeratosis Congenita 1 Leads to a Benign Form of Dyskeratosis Congenita Syndrome With the Mucocutaneous Triad. Front. Pediatr. 10:834268. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.834268

Received

13 December 2021

Accepted

25 February 2022

Published

06 April 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

Wei Hsum Yap, Taylor’s University, Malaysia

Reviewed by

Mikhail Kostik, Saint Petersburg State Pediatric Medical University, Russia; Hui-Yin Yow, Taylor’s University, Malaysia

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Wang, Li, Xiong, Zhou, Li and Wu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yong-An Zhou, zya655903@163.comPing Li, pingli@sxu.edu.cnChangxin Wu, cxw20@sxu.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Genetics of Common and Rare Diseases, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pediatrics

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.