Abstract

Background:

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction (pFOE) measured with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in combination with venous occlusion is of increasing interest in term and preterm neonates.

Objective:

The aim was to perform a systematic qualitative review of literature on the clinical use of pFOE in term and preterm neonates and on the changes in pFOE values over time.

Methods:

A systematic search of PubMed, Embase and Medline was performed using following terms: newborn, infant, neonate, preterm, term, near-infrared spectroscopy, NIRS, oximetry, spectroscopy, tissue, muscle, peripheral, arm, calf, pFOE, OE, oxygen extraction, fractional oxygen extraction, peripheral perfusion and peripheral oxygenation. Additional articles were identified by manual search of cited references. Only studies in human neonates were included.

Results:

Nineteen studies were identified describing pFOE measured with NIRS in combination with venous occlusion. Nine studies described pFOE measured on the forearm and calf at different time points after birth, both in stable preterm and term neonates without medical/respiratory support or any pathological findings. Nine studies described pFOE measured at different time points in sick preterm and term neonates presenting with signs of infection/inflammation, anemia, arterial hypotension, patent ductus arteriosus, asphyxia or prenatal tobacco exposure. One study described pFOE both, in neonates with and without pathological findings.

Conclusion:

This systematic review demonstrates that pFOE may provide additional insight into peripheral perfusion and oxygenation, as well as into disturbances of microcirculation caused by centralization in preterm and term neonates with different pathological findings.

Systematic review registration:

[https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/], identifier [CRD42021249235].

Introduction

Peripheral muscle oxygenation measured with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has gained increasing interest both in experimental research and for clinical use in preterm and term neonates. It has the potential and advantage to recognize early stages of sepsis and shock due to disturbances in muscular tissue microcirculation (1). An important parameter of peripheral muscle NIRS measurements is peripheral fractional oxygen extraction (pFOE). This measure is assumed to provide important additional information in regard to infection or inflammation and anemia (2, 3). pFOE is measured with NIRS in combination with the venous occlusion method. The NIRS technology uses near-infrared light that propagates through tissues where it is differently absorbed by oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (deoxy-Hb). Relative changes in HbO2 and deoxy-Hb in a tissue can be calculated from changes in the attenuation of light (4, 5). This calculated measure provides the tissue oxygenation index (TOI) or regional tissue oxygen saturation (rSO2), depending on the NIRS monitor used, and calculated by the equation HbO2/(HbO2+ deoxy-Hb). TOI/rSO2 reflect mean hemoglobin oxygenation in venous (70%), capillary (20%), and arteriolar (10%) compartments (6, 7), but the relative distribution might change with different pathological conditions causing disturbances in microcirculation (8).

Peripheral muscle NIRS measurements can be performed on the one hand in combination with venous or arterial occlusion, or on the other hand without occlusion. The occlusion is performed using a pneumatic cuff placed around the upper arm or thigh and a NIRS optode on the lower arm or calf. During venous occlusion the pneumatic cuff is inflated to a pressure, which is above the venous pressure and below the diastolic arterial pressure. Therefore, venous outflow is interrupted and arterial inflow to the extremity is undisturbed. Changes in HbO2, deoxy-Hb and total hemoglobin (Hbtot) during the venous occlusion are caused by arterial inflow and the oxygen consumption of the measured tissue. This enables the calculation of blood-flow, venous-oxygen-saturation (SvO2) and pFOE. During arterial occlusion the cuff is inflated to a pressure above the systolic arterial pressure, and changes of HbO2 and deoxy-Hb are only due to oxygen consumption. Due to better feasibility, less discomfort and higher reliability due to less influence of movement artifacts, the venous occlusion method has become the preferred method when compared to the arterial occlusion method (2, 7, 9–13). Quality criteria to increase the reproducibility of peripheral muscle NIRS measurements in combination with venous occlusion have already been published (7).

Peripheral muscle NIRS measurements are mainly performed with devices able to display information of different hemoglobin fractions [peripheral HbO2 (pHbO2) and deoxy-Hb (p-deoxy-Hb)] in short time intervals (14). By combining peripheral NIRS measurements with venous occlusion, important information about oxygenation, perfusion, tissue supply, and demand of oxygen can be obtained.

All calculations in peripheral muscle NIRS are based on ΔpHbO2 and Δp-deoxy-Hb during the venous occlusion: pFOE (11, 15) is calculated as a ratio of peripheral muscle oxygen consumption (pVO2) and peripheral muscle oxygen delivery (pDO2): pVO2/pDO2. Therefore, pFOE reflects the regional oxygen extraction, calculated from oxygen delivery and consumption for the measured organ. pVO2 is calculated out of peripheral muscle hemoglobin flow (pHbflow/min), arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) and peripheral muscle mixed venous saturation (pSvO2) using the following equation (pHbflow/min) × 4 × (SpO2/100-pSvO2) and pDO2 is calculated as: (pHbflow/min) × 4 × (SpO2/100) (7, 16, 17).

The peripheral muscle hemoglobin flow (pHbflow/min) represents the increase in total hemoglobin (ΔpHbtot)—the sum of Δp-deoxy-Hb and ΔpHbO2, during venous occlusion within 1 min (7, 16, 17). pSvO2 is calculated as the ratio of ΔpHbO2 and ΔpHbtot: ΔpHbO2p/ΔHbtot and represents mainly the venous compartment (7).

In contrast to the pFOE, which represents the relative difference/extraction from arterial to venous compartment, the peripheral fractional tissue oxygen extraction (pFTOE) is calculated from the tissue oxygenation (widely described as TOI) and SpO2. The measure represents the relative difference/extraction from arterial to tissue compartment, thus including smaller venous and arterial vessels and capillaries: (SpO2-TOI)/SpO2 (18).

Peripheral muscle oxygen extraction (pOE) can be calculated out of the difference of SpO2-SvO2.

The aim of the present review was to perform a systematic qualitative review of literature on pFOE and pOE measured with NIRS in combination with the venous occlusion method in preterm and term neonates. We wanted to define normal values of stable neonates, and also evaluate the use of pFOE and pOE in clinical practice by including sick neonates or neonates with pathological findings.

Methods

Articles were identified using the stepwise approach specified in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement (19). This systematic review was approved and registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021249235).

Search strategy

A systematic review was performed using the electronic databases PubMed, Embase and Ovid Medline to identify articles using a predefined algorithm (Appendix), with the search terms: newborn, infant, neonate, preterm, term, near-infrared spectroscopy, NIRS, oximetry, spectroscopy, tissue, muscle, peripheral, arm, calf, pFOE, pOE, FOE, OE, oxygen extraction, fractional oxygen extraction, tissue oxygen extraction, peripheral perfusion and peripheral oxygenation. Additional published reports were identified through a manual search of references in the retrieved original papers and review articles. No language restrictions were applied. The search was performed from January 1974 through April 2022.

We included original research of only human studies providing peripheral muscle oxygen extraction measured on the forearm or calf with NIRS and the venous occlusion method in term and preterm neonates.

Study selection

Two authors (C.W. and G.P.) independently evaluated the articles identified following the literature review for eligibility, by assessing the title and abstract of the studies. The full texts were reviewed if uncertainty remained regarding eligibility for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus between the two authors (C.W. and G.P.), who critically appraised the full text and assessed the methodological quality of the included studies. The data were analyzed qualitatively. Data extraction included study design, patients’ characteristics, study aim, device used in the study, position of the measurement, interoptode distance (cm), venous occlusion, age at assessment and duration of measurements. Furthermore, the values described in each of the included studies were analyzed qualitatively and sorted according to the mean/median gestation of the neonate (preterm and term neonates), the mean/median time point of measurement and the position of measurement (forearm, calf). The infants described in each of the included studies were divided into two groups: (I) stable infants without medical/respiratory support and without pathological findings (control groups) (II) sick infants, infants with need for medical/respiratory support, infants with pathological findings (e.g., prenatal tobacco exposure, patent ductus arteriosus).

Results

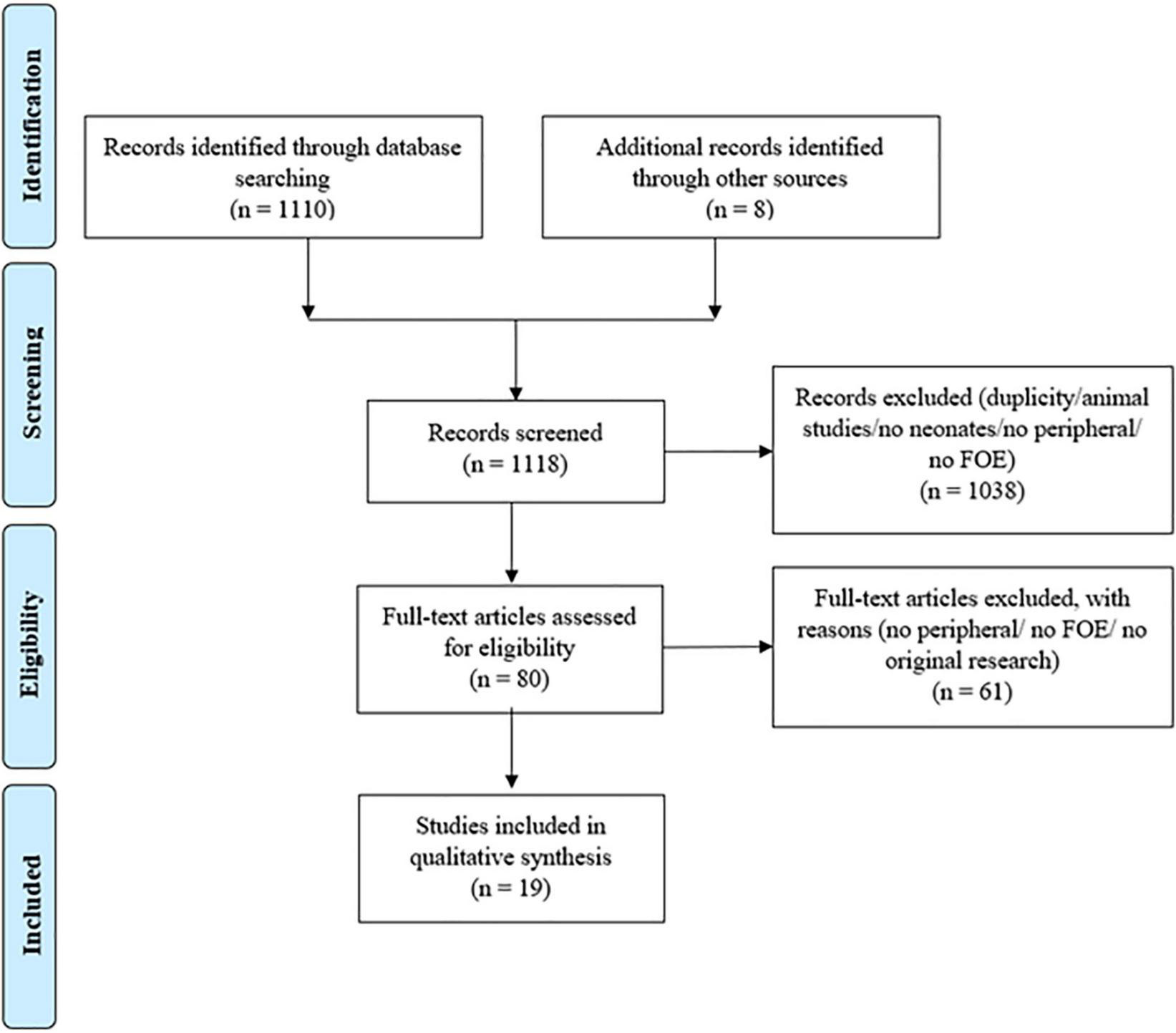

Through the primary search 1,118 articles were identified; 542 articles were identified in PubMed, 352 articles in EMBASE, 216 articles in Ovid and eight articles through other sources. After removal of duplicates and exclusion: no human studies, no neonates, peripheral NIRS measurements of body parts other than extremities and missing calculation of pFOE, 80 relevant studies were assessed and 19 finally fulfilled our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Characteristics of the included 19 studies, giving an overview of the basic data, are presented in Table 1. Reported pFOE and/or pOE values are displayed in Table 2. 16 studies described values of pFOE or pOE and three studies described pFOE (20, 21) and pOE (22) for each patient in case series that were not comparable to the other included studies or they did not provide the exact values.

FIGURE 1

PRISMA flow chart.

TABLE 1

| References | Study design | Neonates (n) | Patients | Study aim | Device | Position | Calculated value | Interoptode distance (cm) | Type of occlusion | Age at assessment | Duration of measurements |

| Bay-Hansen et al. (22) | Observational study | 14 | Preterm and term neonates | Possible relationship between peripheral and central venous saturation and co-oxymetrie | (Radiometer, Denmark | Lower leg | pOE | 2.3 cm | Venous | 1–17 weeks after birth | n.a. |

| Binder and Urlesberger (31) | Observational study | 180 | Preterm and term neonates | Association between leukocyte counts and peripheral tissue oxygenation | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Left calf | pFOE | 3.0 cm | Venous | Within the first 2 months after birth (0–1,392 h after birth) | n.a. |

| Bravo et al. (20) | Prospective uncontrolled case series study | 16 | Neonates with congenital heart defects | Effects of rescue therapy with levosimendan on cerebral and peripheral perfusion and oxygenation | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Thigh | pFOE | 4.0 cm | None | n.a. | 7–19 h |

| Kissack and Weindling (13) | Observational study | 24 | Preterm neonates | Relationship between MABP and peripheral blood flow, pFOE in sick, ventilated babies | NIRO500 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Right forearm | pFOE | 1.0, 1.5 cm | Venous | <12 h after birth | n.a. |

| Mileder et al. (24) | Observational study | 28 | Preterm neonates | Influence of open DA on peripheral muscle oxygenation | NIRO200NX (Hamamatsu, Japan) |

Lateral calf | pFOE | 2.0 and 4.0 cm | Venous | 1st and 3rd day after birth | n.a. |

| Pellicer et al. (21) | Phase I, randomized blinded study | 20 | Neonates undergoing cardiovascular surgery | Efficacy of milrinone and levosimendan in newborns undergoing cardiovascular surgery | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Thigh | pFOE | 4.0 cm | None | 6–21 days after birth | During first postoperative day, 4 h at 48 and 96 h after surgery |

| Pichler et al. (12) | Observational study | 50 | Term neonates | Analyses of changes in peripheral oxygenation with postnatal age | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Left forearm | pFOE | 3.5 cm | Venous | Within the first week after birth | n.a. |

| Pichler et al. (27) | Observational study | 20 | Term neonates | Compare NIRS measurements on forearm and calf | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Left forearm, left calf | pFOE | 3.5 cm | Venous | Within the first 3 days after birth | n.a. |

| Pichler et al. (26) | Cohort observational study | 15 | Term neonates | Smoking during pregnancy and influence on peripheral tissue oxygenation | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Left forearm | pFOE | 3.5 cm | Venous | Within 2 days after birth | n.a. |

| Pichler et al. (7) | Prospective cohort observational study | 40 | Preterm and term neonates | To increase reproducibility, accuracy of peripheral muscle NIRS (quality criteria) | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Lateral calf | pFOE, pOE | 3.0 cm | Venous | 13 ± 15 days after birth | Reapplication |

| Pichler et al. (25) | Observational cohort study | 116 | Preterm and term neonates | To analyze parameters potentially influencing peripheral oxygenation and perfusion | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Left lateral calf | pFOE | 3.0 cm | Venous | 106 (2–1,392) days after birth | n.a. |

| Pichler et al. (3) | Observational study | 66 | Preterm and term neonates | Peripheral muscle oxygenation measurement in neonates with elevated CRP value | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Left lateral calf | pFOE | 3.0 cm | Venous | Within the 1st week after birth | n.a. |

| Tax et al. (32) | Observational study | 38 | Preterm and term neonates | Influence of perinatal asphyxia on peripheral oxygenation | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Left lateral calf | pFOE | 3.0 cm | Venous | <48 h after birth | n.a. |

| Wardle et al. (2) | Observational cohort-control study | 94 | Preterm neonates | Measurement of tissue oxygenation as a marker of need transfusion, normal range for forearm FOE | NIRO500 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Upper forearm | pFOE | 1.5–2.5 cm | Venous | 9–37 days after birth | 8 h |

| Wardle et al. (17) | Observational cohort-control study | 30 | Ventilated preterm neonates | Hypotension and influence on peripheral oxygenation | NIRO500 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Forearm | pFOE | 1.5–2.5 cm | Venous | 3.5–19.0 h after birth | n.a. |

| Wardle (30) | Randomized controlled trial | 74 | Preterm neonates | Use of pFOE to guide need for blood transfusion | n.a. | Upper forearm | pFOE (calculated out of SvO2) | n.a. | Partial venous | 3–8 days after birth | n.a. |

| Wolfsberger et al. (23) | Observational study | 100 | Preterm neonates | Peripheral muscle NIRS during the first 24 h in stable preterm neonates | NIRO200NX (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Right forearm | pFOE (VO2/DO2) | 2.0 and 3.5 cm | Venous | <24 h after birth | n.a. |

| Zaramella et al. (28) | Observational study | 43 | Term neonates | Evaluate relationship between foot PI and NIRS measures | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | calf | pFOE | 3.5 cm | Venous and arterial | 1–5 days after birth | n.a. |

| Zaramella et al. (29) | Observational case-control study | 22 | Term neonates | Clamping time and affection on limb perfusion and heart hemodynamics | NIRO300 (Hamamatsu, Japan) | Calf | pFOE | n.a. | Venous | 72 h after birth | n.a. |

Characteristics of the included studies in preterm and term neonates, listed alphabetically according to the last name of the first author.

cm, centimeters; CRP, C-reactive protein; d, days; DA, ductus arteriosus; DO2, oxygen delivery; g, grams; h, hours; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; n.a., not available; NIRS, near-infrared spectroscopy; OE, oxygen extraction; pFOE, peripheral fractional oxygen extraction; SvO2, mixed venous oxygenation; VO2, oxygen consumption.

TABLE 2

| Time point | Device | Gestational age (weeks) | References | Values | Intervention/condition |

| Forearm pFOE in stable preterm neonates | |||||

| 0–6 h after birth | NIRO200 | 33.5 (32.5–34.1) | Wolfsberger et al. (23) | 0.35 (0.29–0.40) | Stable, no intervention |

| 7–12 h after birth | NIRO200 | 33.7 (33.1–34.3) | Wolfsberger et al. (23) | 0.29 (0.25–0.33) | Stable, no intervention |

| 13–18 h after birth | NIRO200 | 34.1 (33.2–34.6) | Wolfsberger et al. (23) | 0.27 (0.23–0.29) | Stable, no intervention |

| 19–24 h after birth | NIRO200 | 33.8 (32.6–34.6) | Wolfsberger et al. (23) | 0.29 (0.22–0.34) | Stable, no intervention |

| 18 (9–36) days after birth | NIRO500 | 29 (28–31.5) | Wardle et al. (2) | 0.35 ± 0.06 | None |

| 21 (11–35) days after birth | NIRO500 | 26 (25–28) | Wardle et al. (2) | 0.33 ± 0.05 | Asymptomatic, anemic, after transfusion |

| Forearm pFOE in stable term neonates | |||||

| 14.0 (0–24) h after birth | NIRO300 | 39 ± 1 | Pichler et al. (26) | 0.30 ± 0.04 | Non-smoking |

| 20.7 ± 9.6 h after birth | NIRO300 | 39.5 ± 1.1 | Pichler et al. (12) | 0.32 ± 0.13 | None |

| 25.6 (24–48) h after birth | NIRO300 | 39 ± 1 | Pichler et al. (26) | 0.35 ± 0.04 | Non-smoking |

| 38.7 ± 27.0 h after birth | NIRO300 | 39.5 ± 0.7 | Pichler et al. (27) | 0.32 ± 0.07 | None |

| 82.9 ± 20.9 h after birth | NIRO300 | 39.5 ± 1.1 | Pichler et al. (12) | 0.38 ± 0.08 | None |

| Calf pFOE in stable preterm neonates | |||||

| 12.5 (1.0–74.0) h after birth | NIRO200NX | 34.5 ± 1.3 | Mileder et al. (24) | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) | Closed ductus arteriosus |

| 106 ± 221 h after birth | NIRO300 | 35.5 ± 2.9 | Pichler et al. (25) | 0.30 ± 0.07 | None |

| Calf pFOE in stable term neonates | |||||

| 38.7 ± 27.0 h after birth | NIRO300 | 39.5 ± 0.7 | Pichler et al. (27) | 0.32 ± 0.07 | None |

| 41 ± 28 h after birth | NIRO300 | 37.5 ± 2.8 | Pichler et al. (3) | 0.28 ± 0.05 | No CRP elevation |

| 2.6 ± 0.9 days after birth | NIRO300 | 39.1 ± 1.4 | Zaramella et al. (28) | 0.4 ± 0.1 | None |

| 72 (61–74) h after birth | NIRO300 | 39 (37–42) | Zaramella et al. (29) | 0.48 (0.30–0.55) | Early cord clamping time |

| 72 (52–74) h after birth | NIRO300 | 40 (37–41) | Zaramella et al. (29) | 0.52 (0.36–0.57) | Late cord clamping time |

| Forearm pFOE in sick preterm neonates/preterm neonates with pathological findings | |||||

| 7.5 (3.5–10.3) h after birth | NIRO500 | 27 (27–29) | Wardle et al. (17) | 0.31 (0.25–0.34) | Normotensive |

| 8 (2–12) h after birth | NIRO500 | 26 (23–29) | Kissack and Weindling (13) | 0.27 ± 0.06 | None |

| 16.5 (8.5–19.0) h after birth | NIRO500 | 27 (26–29) | Wardle et al. (17) | 0.33 (0.28–0.37) | Hypotensive |

| 12 (6–21) days after birth | n.a | 29 (27–31) | Wardle (30) | 0.35 ± 0.09 | At transfusion |

| 25 (13–40) days after birth | n.a | 30 (27–32) | Wardle (30) | 0.43 ± 0.08 | At transfusion |

| 21 (11–35) days after birth | NIRO500 | 26 (25–28) | Wardle et al. (2) | 0.33 ± 0.05 | Asymptomatic, anemic, before transfusion |

| 23 (16–37) days after birth | NIRO500 | 28 (26.5–29.5) | Wardle et al. (2) | 0.43 ± 0.06 | Symptomatic, anemic, before transfusion |

| 23 (16–37) days after birth | NIRO500 | 28 (26.5–29.5) | Wardle et al. (2) | 0.37 ± 0.06 | Symptomatic, anemic, after transfusion |

| Forearm pFOE in sick term neonates/term neonates with pathological findings | |||||

| 14.0 (0–24) h after birth | NIRO300 | 39 ± 1 | Pichler et al. (26) | 0.37 ± 0.04 | Smoking |

| 26.0 (24–48) h after birth | NIRO300 | 40 ± 1 | Pichler et al. (26) | 0.34 ± 0.08 | Smoking |

| Calf pFOE in sick preterm neonates/preterm neonates with pathological findings | |||||

| 12.5 (1.0–74.0) h after birth | NIRO200NX | 33.1 ± 1.3 | Mileder et al. (24) | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) | Open ductus arteriosus |

| 53 (0–1,392) h after birth | NIRO300 | 35.5 (24.4–42.0) | Binder and Urlesberger (31) | 0.29 (0.15–0.50) | None |

| 13.0 ± 15.6 days after birth | NIRO300 | 35.0 ± 3.1 | Pichler et al. (7) | 0.37 ± 0.09 | None |

| 13.3 ± 15.7 days after birth | NIRO300 | 35.0 ± 3.2 | Pichler et al. (7) | 0.34 ± 0.07 | None |

| Calf pOE in sick term neonates/term neonates with pathological findings | |||||

| 106 ± 221 h after birth | NIRO300 | 35.5 ± 2.9 | Pichler et al. (25) | 26.1 ± 6.7 | None |

| Calf pFOE in sick term neonates/term neonates with pathological findings | |||||

| 19.0 ± 13.0 h after birth | NIRO300 | 38.1 ± 1.2 | Tax et al. (32) | 0.33 ± 0.05 | Asphyxiated neonates |

| 20.6 ± 11.7 h after birth | NIRO300 | 39.2 ± 1.3 | Tax et al. (32) | 0.28 ± 0.06 | No asphyxia |

| 41 ± 25 h after birth | NIRO300 | 37.7 ± 2.9 | Pichler et al. (3) | 0.30 ± 0.08 | CRP elevation |

pFOE and pOE in preterm and term neonates with peripheral muscle NIRS measurements on the forearm and calf, sorted according to the mean/median time point after birth when NIRS measurements were performed.

Stable is defined as no respiratory and medical support without pathological findings/conditions. CRP, C-reactive protein; pFOE, peripheral fractional oxygen extraction; pOE, peripheral oxygen extraction.

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction in stable preterm and term neonates

In stable preterm neonates one study (23) described pFOE measured on the forearm 0–12 h after birth and 12–24 h after birth and one study (2) after the seventh postnatal day. Calf pFOE measurements in preterm neonates have been described in one study 12–24 h after birth (24) and in another one between day 3 and 7 (25). In stable term neonates without medical/respiratory support and/or pathological finding, pFOE measured on the forearm between 12 and 24 h after birth and 24 and 48 h after birth has been described in three studies (12, 26, 27), whereas one study measured pFOE between the third and seventh day after birth (12). Calf pFOE was measured in term neonates in two studies 24–48 h after birth (3, 27), in one study between 48 and 72 h after birth (28) and in one study between the third and seventh day after birth (29). For specification of the values see Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Age at time of the study (mean/median) | Forearm | Calf | ||

|

|

|

|||

| Preterm | Term | Preterm | Term | |

| 15 min after birth | ||||

| 0–12 h after birth | 0.35 (0.29–0.40) | |||

| (Wolfsberger et al., 2020) | ||||

| 0.29 (0.25–0.33) | ||||

| (Wolfsberger et al., 2020) | ||||

| 12–24 h after birth | 0.27 (0.23–0.29) | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) | |

| (Wolfsberger et al., 2020) | (Pichler et al., 2008) | (Mileder et al., 2018) | ||

| 0.29 (0.22–0.34) | 0.32 ± 0.13 | |||

| (Wolfsberger et al., 2020) | (Pichler et al., 2007a) | |||

| 24–48 h after birth | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | ||

| (Pichler et al., 2008) | (Pichler et al., 2007b) | |||

| 0.32 ± 0.07 | 0.28 ± 0.05 | |||

| (Pichler et al., 2007b) | (Pichler et al., 2012) | |||

| 48–72 h after birth | 0.4 ± 0.1 | |||

| (Zaramella et al., 2005) | ||||

| >72 h–7 days after birth | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.48 (0.30–0.55) | |

| (Pichler et al., 2007a) | (Pichler et al., 2011) | (Zaramella et al., 2008) | ||

| 0.52 (0.36–0.57) | ||||

| (Zaramella et al., 2008) | ||||

| >7 days after birth | 0.35 ± 0.06 | |||

| (Wardle, 1998) | ||||

| 0.33 ± 0.05 | ||||

| (Wardle, 1998) | ||||

pFOE in stable preterm and term neonates sorted according to the time point of measurement after birth.

If different pFOE values of the same study are listed more than once in one time period, the study provided more than one pFOE value within this defined period. pFOE are display in different colors, according to the used NIRS monitor ( ). CRP, C-reactive protein; NIRS, near-infrared spectroscopy; pFOE, peripheral fractional oxygen extraction.

). CRP, C-reactive protein; NIRS, near-infrared spectroscopy; pFOE, peripheral fractional oxygen extraction.

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction in preterm and term neonates with pathological findings

Concerning preterm neonates, two studies (13, 17) described pFOE measured on the forearm within 0–12 h after birth in sick, very low birth weight neonates and hypotensive neonates. One study (17) measured pFOE between 12 and 24 h in hypotensive neonates. Two studies included pFOE measurements on the forearm of preterm neonates with anemia after the seventh day after birth (2, 30). pFOE measurements on the calf were described in preterm neonates with patent ductus arteriosus between 12 and 24 h (24) and in neonates with leukocytosis between 48 and 72 h (31) after birth.

One study of term neonates of mothers who had smoked tobacco during pregnancy described pFOE measurements on the forearm 12–24 h and 24–48 h after birth (26). In one study calf pFOE measurements in different sick term neonates have been described (7). Further, two studies described calf pFOE in term neonates with asphyxia 12–24 h after birth (32) and in term neonates with elevated CRP 48–72 h after birth (3). For the specification of the values see Table 4.

TABLE 4

| Age at time of the study (mean/median) | Forearm | Calf | ||

|

|

|

|||

| Preterm | Term | Preterm | Term | |

| 15 min after birth | ||||

| 0–12 h after birth | 0.31 (0.25–0.34) (hypotension) |

|||

| (Wardle et al., 1999) | ||||

| 0.27 ± 0.06 (sick, ventilated neonates) | ||||

| (Kissack and Weindling, 2009) | ||||

| 12–24 h after birth | 0.33 (0.28–0.37) (hypotension) |

0.37 ± 0.04 (smoking) | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) (open ductus) | 0.33 ± 0.05 (asphyxia) |

| (Wardle et al., 1999) | (Pichler et al., 2008) | (Mileder et al., 2018) | (Tax et al., 2013) | |

| 0.28 ± 0.06 (asphyxia) | ||||

| (Tax et al., 2013) | ||||

| 24–48 h after birth | 0.34 ± 0.08 (smoking) | |||

| (Pichler et al., 2008) | ||||

| 48–72 h after birth | 0.29 (0.15–0.50) (elevated leukocytes) | 0.30 ± 0.08 (elevated CRP) | ||

| (Binder and Urlesberger, 2013) | (Pichler et al., 2012) | |||

| >72 h–7 days after birth | ||||

| >7 days after birth | ||||

| 0.35 ± 0.09 (anemia) | ||||

| (Wardle, 2002) | ||||

| 0.43 ± 0.08 (anemia) | ||||

| (Wardle, 2002) | ||||

| 0.33 ± 0.05 (anemia, transfusion) | 0.37 ± 0.09 (sick neonates) | |||

| (Wardle et al., 1998) | (Pichler et al., 2009) | |||

| 0.43 ± 0.06 (anemia, transfusion) | 0.34 ± 0.07 (sick neonates) | |||

| (Wardle et al. 1998) | (Pichler et al., 2009) | |||

| 0.37 ± 0.06 (anemia, transfusion) | ||||

| (Wardle et al. 1998) | ||||

pFOE in preterm and term neonates with pathological findings/conditions sorted according to the time point of measurement after birth.

If different pFOE values of the same study are listed more than once in one time period, the study provided more than one pFOE value within this defined period. pFOE are display in different colors, according to the used NIRS monitor ( , monitor not mentioned). CRP, C-reactive protein; NIRS, near-infrared spectroscopy; pFOE, peripheral fractional oxygen extraction.

, monitor not mentioned). CRP, C-reactive protein; NIRS, near-infrared spectroscopy; pFOE, peripheral fractional oxygen extraction.

Peripheral muscle oxygen extraction in preterm and term neonates

One study defining quality criteria of peripheral muscle measurements calculated pOE (7), but not providing exact values. Further, one study (22) described pOE for each patient in case series.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review focusing on pFOE and pOE in clinical use in stable preterm and term neonates and in sick neonates or in neonates with pathological findings, whereby we were able to identify and include 19 studies.

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction in stable preterm and term neonates

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction is an important measure which provides information about oxygen extraction of the peripheral muscle on calf or forearm. pFOE has been described in 10 studies in stable preterm and term neonates without medical and/or respiratory support and without pathological findings. Therefore, this could be interpreted as normal values/reference ranges for the specified time period. However, only one study described normal values for pFOE with a sufficient sample size. Wolfsberger et al. (23) published normal values for peripheral muscle tissue oxygenation on the forearm with the NIRO200 monitor in combination with venous occlusion, in stable preterm infants within the first 24 h after birth. In this observational study they described a decrease in pFOE from 0–6 h after birth to 12–18 h after birth (23). Thereafter, a slight increase in pFOE was observed. Comparing pFOE measured within the first 6 h after birth (23) with pFOE in preterm neonates after seventh days after birth (day 9–37 after birth) (2) reveals similar values. Wolfsberger et al. (23) published values over a time period of 24 h. It may be assumed, that beside the absolute value of pFOE, changes from a baseline during a prolonged monitoring time period may provide also important information about pathological conditions.

Measurements of pFOE on the calf of preterm neonates were performed in two studies (24, 25). pFOE was similar when measured within 12–24 h (24) and between the third and seventh day after birth (25). Nevertheless, the second decimal place was not specified in one study (24), which would have provided more precise information. pFOE of calf (24) were similar when compared to forearm pFOE (23) within similar time periods.

In studies on term neonates with measurements at a specified time point or period, pFOE on the forearm (12, 26, 27) and pFOE of the calf (3, 27–29) increased from the first 12–24 h to >72 h after birth. Higher values were observed in measurements on the calf compared to the forearm. The highest pFOE values were observed in term neonates with measurements on the calf 72 h after birth (29). These studies are in accordance with the study by Pichler et al. (25) that studied preterm and term neonates. They demonstrated a significant increase of pFOE with increasing postnatal age (25). It was suggested that the changes in pFOE might be a result of changes in the muscle tone. In the latter study, in addition, a significant negative correlation between gestational age and pFOE was described (25). Other included studies do not suggest a difference in pFOE between preterm and term neonates. However, the studies report on neonates with different gestational age which could have influenced on the discrepancy in findings of gestational age impact on pFOE.

In addition to postnatal age and gestational age Pichler et al. (25) investigated potential factors influencing peripheral muscle NIRS measurements. pFOE correlated positively with birth weight, actual weight and diameter of the calf, suggesting a potential influence of the tissue composition. Furthermore, higher pFOE values correlated significantly positively with higher SpO2 values. Peripheral temperature and hemoglobin concentration, correlated negatively with pFOE.

Comparison forearm and calf peripheral fractional oxygen extraction

Forearm and calf NIRS measurements have been compared in healthy term neonates with a postnatal age of 38.7 ± 27.0 h (27). No difference in pFOE measured on forearm and on calf could be observed (27). When comparing different studies where pFOE was measured between the third and seventh day after birth, there seems to be a difference between forearm and calf. Pichler et al. described a mean pFOE of 0.38 at a mean age of 82.9 ± 20.9 h, whereas Zaramella et al. (29) described a median pFOE of 0.48–0.52 with a median age of 72 h after birth. The comparison however is difficult, since one study described mean pFOE and the other the median pFOE. Moreover, Zaramella et al. (29) did not describe the thickness of subcutaneous fat and/or the circumference of the measured limb, which might have had an influence on peripheral NIRS measurements.

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction in preterm and term neonates with pathological findings

In preterm neonates peripheral muscle NIRS measurements have been demonstrated to provide useful information in case of anemia (2, 30) and hypotension (13, 17), as well as in a potential influence of patent ductus arteriosus (24) and elevated leukocyte counts (31). In term neonates peripheral muscle NIRS measurements may provide additional information on exposure to certain risk factors, including maternal smoking during pregnancy (26), perinatal asphyxia (32) and elevated C reactive protein (CRP) values (3).

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction and inflammation/infection

At early stages of inflammation when other routine vital parameters are still within normal ranges, pFOE has been demonstrated to provide useful information (1, 33). Binder et al. (31) examined associations between leukocyte counts and peripheral tissue oxygenation in preterm and term neonates within the first 2 months after birth. Peripheral tissue oxygen consumption decreased and vascular resistance increased with higher leukocyte counts, but no association between pFOE and leukocyte counts could be observed. Regarding CRP, Pichler et al. (3) demonstrated an impaired peripheral oxygenation and perfusion in cardio-circulatory stable preterm and term neonates with CRP elevations >10 mg/L. TOI, SvO2, DO2, and VO2 were significantly lower in neonates with elevated CRP levels. However, no difference in pFOE was observed in neonates with CRP >10 mg/L, compared to the control group with no CRP elevation. They assumed that a more pronounced difference could have been demonstrated if unstable cardio-circulatory neonates had been included. Furthermore, CRP elevations are seen in a variety of inflammatory conditions, which also might have influenced the results (34). Ongoing now, is a prospective trial (the pFTOE trial; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04818762) observing a potential difference in pFTOE within the first 6 h after birth, and comparing preterm and term neonates with and without infection.

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction and anemia

Blood transfusion in preterm neonates is guided by total hemoglobin and hematocrit values as well as clinical signs of anemia, even though the indications are not particularly well-defined. An observational study in preterm neonates showed that pFOE was higher in neonates with symptomatic anemia and decreased after transfusion (2). Wardle et al. (30) performed a randomized controlled trial to investigate the use of pFOE to guide need for blood transfusion in preterm neonates. For this purpose, two groups were compared where the conventional group received transfusion according to the hemoglobin value and clinical symptoms of anemia, whereby the NIRS group received transfusion when forearm pFOE was ≥0.47, or if significant clinical concerns occurred. In the NIRS group, fewer transfusions were given to the preterm neonates compared to the conventional group. However, Wardle et al. stated that pFOE failed to identify many neonates that required blood transfusion. They assumed that these results were due to the fact, that the clinicians relied on conventional indicators of transfusion or that pFOE of 0.47 as a single parameter was not sensitive enough to predict the need for transfusion.

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction and arterial hypotension

Arterial hypotension is a condition that can be observed in about 20% of preterm neonates and can be associated with several neonatal morbidities (35). Early stages of shock, with signs of centralization and microcirculatory dysfunction may manifest with impaired peripheral tissue oxygenation and circulation, which might be measured by NIRS. Wardle et al. (17) observed differences in peripheral tissue oxygenation in preterm neonates with and without arterial hypotension. VO2 and DO2 were lower in hypotensive preterm neonates compared to normotensive neonates. No difference in pFOE was shown between the two groups. Another trial investigated peripheral muscle oxygenation in hypotensive preterm neonates, however, the authors only examined the TOI and not pFOE (36).

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction and ductus arteriosus

Mileder et al. (24) demonstrated higher pFOE values in preterm neonates with patent ductus arteriosus compared to those with a closed ductus arteriosus. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation between pFOE and diameter of the ductus arteriosus was observed. They assumed that an increase in pFOE occurred as a result of reduced peripheral oxygen delivery, due to a steal phenomenon.

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction and asphyxia

The influence of perinatal asphyxia on peripheral oxygenation and perfusion has been investigated by Tax et al. (32). NIRS parameters differ significantly between neonates with and without perinatal asphyxia, with higher pFOE values in asphyxiated neonates. Furthermore, pFOE increased with decreasing umbilical artery pH.

Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction and congenital heart disease

Bravo et al. (20) investigated the effect of levosimendan (reduces acute and decompensated heart failure by increasing minute volume) on hemodynamics in critically ill infants with low cardiac output. Application of seven doses of levosimendan was investigated in neonates with congenital heart defects who underwent medical or surgical cardiovascular interventions. They observed an improvement of the hemodynamic situation and a beneficial effect on cerebral and peripheral perfusion with a tendency of decreasing pFOE due to a positive balance of oxygen delivery and oxygen extraction. The positive hemodynamic effects of milrinone and levosimendan in 20 neonates undergoing cardiovascular surgery, using NIRS measurements for assessment of changes in cerebral and peripheral perfusion and oxygenation, were also observed by Pellicer et al. (21).

Limitations

This review has some limitations. First of all, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity in study populations, study aims, devices used and neonates’ age at assessment. Secondly, there is no clear/uniform nomenclature for peripheral oxygen extraction in the different publications. Fractional oxygen extraction (FOE), fractional tissue oxygen extraction (FTOE), tissue oxygen extraction (TOE), and oxygen extraction index (OEI) were used in different studies in part synonymously. However, there are large differences between these values. FOE describes the fractional oxygen extraction calculated out of DO2, VO2, and/or SvO2, all measures obtained from NIRS measurements in combination with venous occlusion. FTOE or OEI describe the fractional tissue oxygen extraction obtained without the venous occlusion method, using SpO2 and TOI for calculations. In contrast, TOE is calculated by using the difference of SpO2 and TOI without calculating a ratio to SpO2, like it is done for FOE and FTOE. Thirdly, different NIRS monitors were used for measurements of pFOE in different studies. The pFOE values described in the present review were mainly obtained with the different generations of the NIRO device. Hyttel-Sorensen et al. (37) showed already that the NIRO 200NX and NIRO 300, which were mainly used for pFOE measurements, differ in their absolute values, which might further influence pFOE. They described higher TOI values measured with the NIRO 200NX compared to the NIRO 300, and therefore, lower pFOE values were obtained with the NIRO 200NX. Therefore, comparison of pFOE values measured by different NIRS devices should be performed with caution and published differences should be taken into account. Fourthly, one problem of peripheral NIRS measurements is reproducibility. Recommendations to increase the validity and comparability of peripheral NIRS measurements was published in 2009 (38). Especially studies done before that publication were not performed in a standardized way, which makes the comparison difficult.

Conclusion

Peripheral muscle NIRS measurement and especially pFOE obtained in combination with venous occlusion is a method that provides information on peripheral oxygenation and perfusion in preterm and term neonates. This review demonstrates that peripheral NIRS measurements including pFOE, both in preterm and term neonates, have the potential of providing additional information in different pathological conditions such as anemia, inflammation/infection, arterial hypotension or patent ductus arteriosus. Thus, peripheral NIRS measurements and pFOE might provide a tool of future monitoring of peripheral perfusion and oxygenation that was not routinely available until now. Furthermore, changes of pFOE from a baseline value during a prolonged monitoring, especially in conditions of cardio-circulatory failure, anemia or sepsis, might give important further information. However, an improvement in the monitoring technique, a standardized application/nomenclature and establishment of normal values for the different time points and gestational ages are needed before a routine clinical application can be introduced.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CW and GP conceived the research idea and evaluated the articles. CW, GP, NH, ES, BS, BN, and BU analyzed the data, and contributed to interpretation of the results, drafting, and finalizing the manuscript. CW wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Crookes BA Cohn SM Bloch S Amortegui J Manning R Li P et al Can near-infrared spectroscopy identify the severity of shock in trauma patients? J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. (2005) 58:806–16. 10.1097/01.ta.0000158269.68409.1c

2.

Wardle SP Yoxall CW Crawley E Weindling AM . Peripheral oxygenation and anemia in preterm babies.Pediatr Res. (1998) 44:125–31.

3.

Pichler G Pocivalnik M Riedl R Pichler-Stachl E Zotter H Müller W et al C reactive protein: impact on peripheral tissue oxygenation and perfusion in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2012) 97:F444–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300578

4.

Wolfberg AJ du Plessis AJ . Near-infrared spectroscopy in the fetus and neonate.Clin Perinatol. (2006) 33:707–28. 10.1016/j.clp.2006.06.010

5.

Wolf M Greisen G . Advances in near-infrared spectroscopy to study the brain of the preterm and term neonate.Clin Perinatol. (2009) 36:807–34. 10.1016/j.clp.2009.07.007

6.

Boushel R Langberg H Olesen J Gonzales-Alonzo J Bülow J Kjaer M . Monitoring tissue oxygen availability with near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in health and disease.Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2001) 11:213–22. 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2001.110404.x

7.

Pichler G Grossauer K Peichl E Gaster A Berghold A Schwantzer G et al Combination of different noninvasive measuring techniques: a new approach to increase accuracy of peripheral near infrared spectroscopy. J Biomed Opt. (2009) 14:014014. 10.1117/1.3076193

8.

De Backer D Orbegozo Cortes D Donadello K Vincent J-L . Pathophysiology of microcirculatory dysfunction and the pathogenesis of septic shock.Virulence. (2014) 5:73–9. 10.4161/viru.26482

9.

Hassan IA-A . Effect of limb cooling on peripheral and global oxygen consumption in neonates.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2003) 88:139F–42F. 10.1136/fn.88.2.F139

10.

Hassan IA-A . Effect of a change in global metabolic rate on peripheral oxygen consumption in neonates.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2003) 88:143F–6F. 10.1136/fn.88.2.F143

11.

Yoxall CW Weindling AM . The measurement of peripheral venous oxyhemoglobin saturation in newborn infants by near infrared spectroscopy with venous occlusion.Pediatr Res. (1996) 39:1103–6. 10.1203/00006450-199606000-00028

12.

Pichler G Grossauer K Klaritsch P Kutschera J Zotter H Muller W et al Peripheral oxygenation in term neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2007) 92:F51–2. 10.1136/adc.2005.089037

13.

Kissack CM Weindling AM . Peripheral blood flow and oxygen extraction in the sick, newborn very low birth weight infant shortly after birth.Pediatr Res. (2009) 65:462–7. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181991e01

14.

Höller N Urlesberger B Mileder L Baik N Schwaberger B Pichler G . Peripheral muscle near-infrared spectroscopy in neonates: ready for clinical use? a systematic qualitative review of the literature.Neonatology. (2015) 108:233–45. 10.1159/000433515

15.

Yoxall CW Weindling AM . Measurement of venous oxyhaemoglobin saturation in the adult human forearm by near infrared spectroscopy with venous occlusion.Med Biol Eng Comput. (1997) 35:331–6. 10.1007/BF02534086

16.

Weindling AM . Peripheral oxygenation and management in the perinatal period.Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. (2010) 15:208–15. 10.1016/j.siny.2010.03.005

17.

Wardle SP Yoxall CW Weindling AM . Peripheral oxygenation in hypotensive preterm babies.Pediatr Res. (1999) 45:343–9. 10.1203/00006450-199903000-00009

18.

Naulaers G Meyns B Miserez M Leunens V Van Huffel S Casaer P et al Use of tissue oxygenation index and fractional tissue oxygen extraction as non-invasive parameters for cerebral oxygenation. Neonatology. (2007) 92:120–6. 10.1159/000101063

19.

Liberati A Altman DG Tetzlaff J Mulrow C Gotzsche PC Ioannidis JPA et al The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2700–2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700

20.

Bravo MC López P Cabañas F Pérez-Rodríguez J Pérez-Fernández E Quero J et al Acute effects of levosimendan on cerebral and systemic perfusion and oxygenation in newborns: an observational study. Neonatology. (2011) 99:217–23. 10.1159/000314955

21.

Pellicer A Riera J Lopez-Ortego P Bravo MC Madero R Perez-Rodriguez J et al Phase 1 study of two inodilators in neonates undergoing cardiovascular surgery. Pediatr Res. (2013) 73:95–103. 10.1038/pr.2012.154

22.

Bay-Hansen R Elfving B Greisen G . Use of near infrared spectroscopy for estimation of peripheral venous saturation in newborns: comparison with co-oximetry of central venous blood.Neonatology. (2002) 82:1–8. 10.1159/000064145

23.

Wolfsberger C Baik-Schneditz N Schwaberger B Binder-Heschl C Nina H Mileder L et al Changes in peripheral muscle oxygenation measured with near-infrared spectroscopy in preterm neonates within the first 24 h after birth. Physiol Meas. (2020) 41:075003. 10.1088/1361-6579/ab998b

24.

Mileder LP Müller T Baik-Schneditz N Pansy J Schwaberger B Binder-Heschl C et al Influence of ductus arteriosus on peripheral muscle oxygenation and perfusion in neonates. Physiol Meas. (2017) 39:015003. 10.1088/1361-6579/aa9c3b

25.

Pichler G Pocivalnik M Riedl R Pichler-Stachl E Morris N Zotter H et al ‘Multi-associations’: predisposed to misinterpretation of peripheral tissue oxygenation and circulation in neonates. Physiol Meas. (2011) 32:1025–34. 10.1088/0967-3334/32/8/003

26.

Pichler G Heinzinger J Klaritsch P Zotter H Müller W Urlesberger B . Impact of smoking during pregnancy on peripheral tissue oxygenation in term neonates.Neonatology. (2008) 93:132–7. 10.1159/000108408

27.

Pichler G Heinzinger J Kutschera J Zotter H Müller W Urlesberger B . Forearm and calf tissue oxygenation in term neonates measured with near-infrared spectroscopy.J Physiol Sci. (2007) 57:317–9. 10.2170/physiolsci.SC004407

28.

Zaramella P Freato F Quaresima V Ferrari M Vianello A Giongo D et al Foot pulse oximeter perfusion index correlates with calf muscle perfusion measured by near-infrared spectroscopy in healthy neonates. J Perinatol. (2005) 25:417–22. 10.1038/sj.jp.7211328

29.

Zaramella P Freato F Quaresima V Secchieri S Milan A Grisafi D et al Early versus late cord clamping: effects on peripheral blood flow and cardiac function in term infants. Early Hum Dev. (2008) 84:195–200. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.04.003

30.

Wardle SP . A pilot randomised controlled trial of peripheral fractional oxygen extraction to guide blood transfusions in preterm infants.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2002) 86:22F–7F. 10.1136/fn.86.1.F22

31.

Binder C Urlesberger B . Leukocytes influence peripheral tissue oxygenation and perfusion in neonates.Signa Vitae. (2013) 8:20. 10.22514/SV82.102013.3

32.

Tax N Urlesberger B Binder C Pocivalnik M Morris N Pichler G . The influence of perinatal asphyxia on peripheral oxygenation and perfusion in neonates.Early Hum Dev. (2013) 89:483–6. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.03.011

33.

Ikossi DG Knudson MM Morabito DJ Cohen MJ Wan JJ Khaw L et al Continuous muscle tissue oxygenation in critically injured patients: a prospective observational study. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. (2006) 61:780–90. 10.1097/01.ta.0000239500.71419.58

34.

Hofer N Müller W Resch B . Non-infectious conditions and gestational age influence C-reactive protein values in newborns during the first 3 days of life.Clin Chem Lab Med. (2011) 49:48. 10.1515/CCLM.2011.048

35.

Barrington KJ Dempsey EM . Cardiovascular support in the preterm: treatments in search of indications.J Pediatr. (2006) 148:289–91. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.056

36.

Pichler G Höller N Baik-Schneditz N Schwaberger B Mileder L Stadler J et al Avoiding Arterial Hypotension in Preterm Neonates (AHIP)—A single center randomised controlled study investigating simultaneous near infrared spectroscopy measurements of cerebral and peripheral regional tissue oxygenation and dedicated interventions. Front Pediatr. (2018) 6:15. 10.3389/fped.2018.00015

37.

Hyttel-Sorensen S Sorensen LC Riera J Greisen G . Tissue oximetry: a comparison of mean values of regional tissue saturation, reproducibility and dynamic range of four NIRS-instruments on the human forearm.Biomed Opt Express. (2011) 2:3047. 10.1364/BOE.2.003047

38.

Pichler G Wolf M Roll C Weindling MA Greisen G Wardle SP et al Recommendations to increase the validity and comparability of peripheral measurements by near infrared spectroscopy in neonates. Neonatology. (2008) 94:320–2. 10.1159/000151655

Appendix

-

Search strategies used for the systematic review

-

#1 newborn* OR infant* OR neonate* OR preterm* OR term*

-

#2 near-infrared spectroscopy* OR NIRS* OR oximetry* OR spectroscopy*

-

#3 tissue* OR muscle* OR peripheral* OR arm* OR calf*

-

#4 pFOE* OR pOE* OR FOE* OR OE* OR oxygen extraction* OR fractional oxygen extraction* OR tissue oxygen extraction* OR peripheral perfusion* OR peripheral oxygenation*

-

Search strategy: #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4

-

Search strategy for PubMed: last performed on 28/04/2022

Summary

Keywords

peripheral fractional oxygen extraction, pFOE, pOE, peripheral muscle oxygenation, near-infrared spectroscopy, microcirculation, disturbances in microcirculation

Citation

Wolfsberger CH, Hoeller N, Suppan E, Schwaberger B, Urlesberger B, Nakstad B and Pichler G (2022) Peripheral fractional oxygen extraction measured with near-infrared spectroscopy in neonates—A systematic qualitative review. Front. Pediatr. 10:940915. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.940915

Received

10 May 2022

Accepted

18 July 2022

Published

23 August 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

Frank Van Bel, University Medical Center Utrecht, Netherlands

Reviewed by

Simone Pratesi, Careggi University Hospital, Italy; Peter Krcho, Louis Pasteur University Hospital Košice, Slovakia

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Wolfsberger, Hoeller, Suppan, Schwaberger, Urlesberger, Nakstad and Pichler.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gerhard Pichler, Gerhard.pichler@medunigraz.at

This article was submitted to Neonatology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pediatrics

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.