- 1Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 2Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, St Mary’s Maternity Hospital, Manchester Foundation Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Paediatrics, Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool, United Kingdom

- 4Maternity Services, St Mary's Maternity Hospital, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom

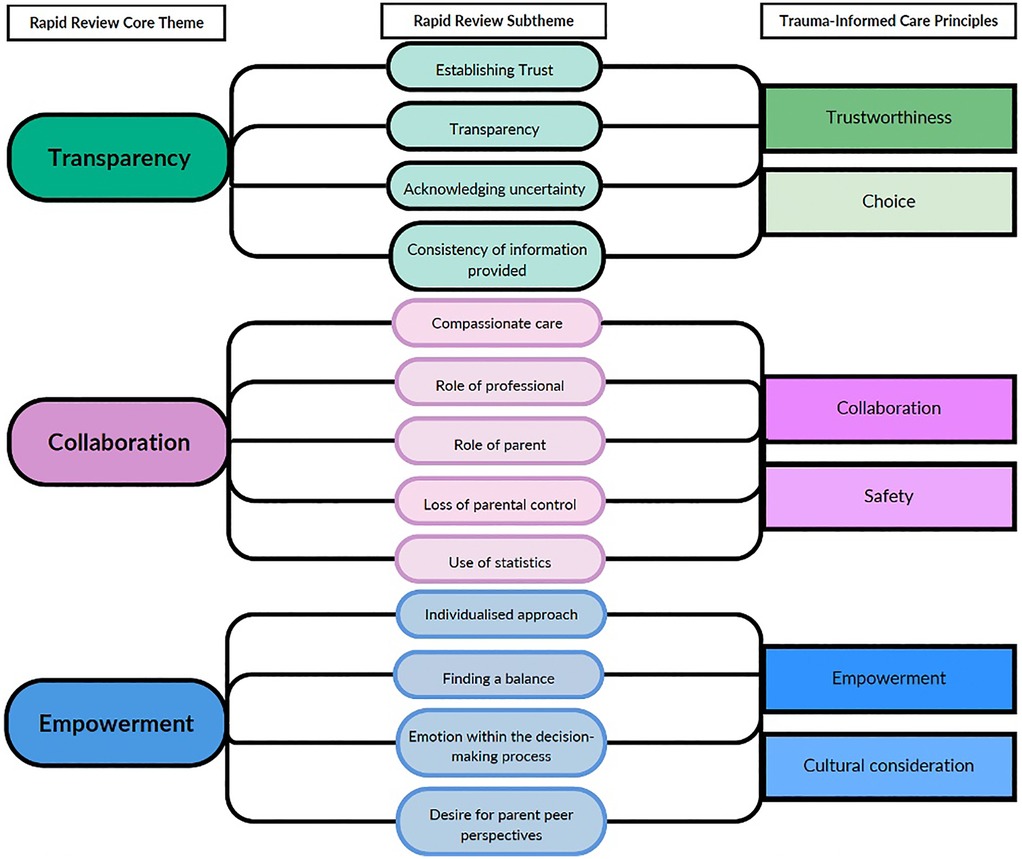

Given the risks of mortality and morbidity for infants born in the periviable period, a decision is made between parents and professionals prior to the birth as to whether survival-focused or comfort care is most appropriate at delivery. Medical information should be shared with parents and parental perspectives and priorities in relation to this information should be explored and integrated into the decision-making process. Conducting these conversations is complex and nuanced. This rapid review conducted a systematic search of the available literature relating to the approaches to and content of the pre-birth periviable conversation and identified three core themes: Transparency, Collaboration and Empowerment. In brief, these themes demonstrate that the information provided to parents should consistently outline all available care options relevant to their baby, including compassionately delivered, but honest and descriptive accounts of emotive options, such as comfort care. Information should be individualised to the specific circumstances and risk factors of that individual family. Perinatal professionals should seek to incorporate discussion of topics key to the ‘good parent belief’ to empower parents within their role. Avoiding or omitting discussion of uncertainty and dismissal of hope within these conversations was associated with parental distrust and impaired communication. The themes identified within this rapid review align with the principles of trauma-informed care and provide a structure for further research and service development focused on improving the quality and experience of pre-birth periviable conversations for future parents.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42022300099, PROSPERO identifier CRD4202230009.

1 Introduction

Neonatal medicine is a rapidly evolving field which has seen tremendous advances in care for infants born with a range of conditions over the last 60 years (1). Throughout that time optimising care of the preterm infant has been a priority and high yield area. As knowledge and technologies have progressed, the ‘periviable’ period (the point in a pregnancy where survival outside the womb is possible, even if improbable) has been continually adjusted (2) (3). Perinatal centres around the world are now able to provide care to infants from 22 weeks gestation with increasing chances of survival (4). Provision of survival-focused care to these infants requires a prolonged period of hospitalisation and all the inherent burdens that come with intensive care—for the infant, their parents, siblings and wider families. There are significant risks of death and disability for infants born in the periviable period, alongside lifelong physical health consequences and increased mental health impacts for families (5, 6). This is not to say that survival-focused care should not be provided to periviable infants. Rather - as is increasingly encouraged by professional frameworks—where possible, a holistic assessment of the individual infant should be made prior to delivery and a nuanced and honest conversation had between perinatal professionals and parents about whether survival-focused care or comfort care would be most appropriate (3). Conducting these conversations is complex and carries an emotional and moral burden for those involved (7). Professional frameworks, whilst encouraging shared decision-making approaches, may lack detail on how to navigate these conversations and meaningfully explore and facilitate incorporation of parental perspectives.

The periviable infant is now a topic of increasing research focus and funding. This has been seen through the expanding number of publications (Supplementary File S1) and incorporation of this topic within perinatal conferences (8–10). Our aim with this review is to succinctly outline the key findings from the currently available literature pertaining to information sharing practices between perinatal professionals and parents facing periviable birth and identify knowledge gaps for future research in this rapidly expanding field.

2 Methods

2.1 Why was a rapid review approach selected?

With the proliferation in academic and clinical interest in optimising care for periviable infants it is important that current research findings are distilled and summarised to enable practising clinicians to remain up to date with best practice management for the dilemmas encountered in managing periviable birth. Additionally, there is a need to provide systematic summaries to streamline identification of key knowledge gaps and provide areas of focus for future research. A rapid review approach was selected for this review to match the pace at which the area of periviable research is expanding, whilst retaining the rigor and transparency of a systematic review process, thus allowing perinatal professionals to have confidence in the review findings (11–13).

This review focuses on literature published from 2021 onwards. This date range was determined in several ways, through acknowledging significant changes in professional guidance, such as the updated framework from the British Association of Perinatal Medicine released in October 2019, an acknowledgement of the potential for COVID-specific publications in 2020 and, crucially, the notable expansion in publications related to periviable birth from 2021 onwards (Supplementary File S1). Given these factors and the need for this review to reflect up to date knowledge regarding information sharing practices with which to make recommendations, this review summarises literature published between 1st January 2021 to the date the search was conducted (29th July 2024).

The study protocol was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) process (15). The study protocol was pre-registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022300099) (14).

2.2 Patient and public involvement

This rapid review has been conducted as part of a wider mixed methods study exploring information sharing practices between perinatal professionals and parents facing periviable birth [PeriviAble DeLiveries: ALIgning PArental aNd PhysiCian PrioritiEs (ALLIANCE)]. The Alliance study has received full approval and support from the Spoons Parental Advisory Group (PAG) who provide support to parents across the North West. When designing this study, members of our research team met with the PAG to gather their perspectives on the issue of periviable communication practices. This topic resonated with multiple parents who articulately outlined their own lived experiences citing numerous situations where they had been given either vague or directly conflicting information from perinatal professionals during their pre-delivery extremely preterm labours. Parents described how information was often either presented with a distressing inaccuracy and lack of empathy (“you're 22 weeks so there's nothing we can do”1), or, with such callously changing variability that parents lost confidence that the team were taking the life of their unborn child seriously. All parents in the PAG meeting agreed that the current level of variation in information provided to parents in labour is unacceptable and improving this should a priority issue for neonatal research agendas. This rapid review forms the first step in tackling this issue by reviewing the existing literature available to perinatal professionals and identifying key gaps and strategies to address these.

2.3 Ethical consideration

This study is a rapid review of previously published data and therefore, did not require formal ethics approval. All included studies had ethical approval in place and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.4 Search strategy

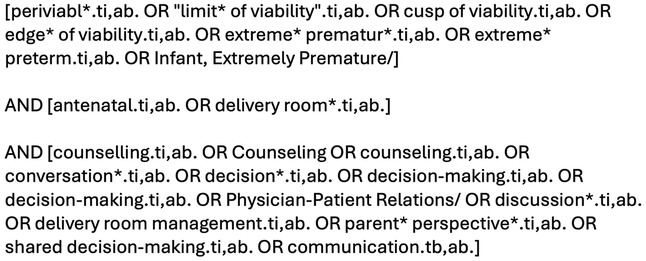

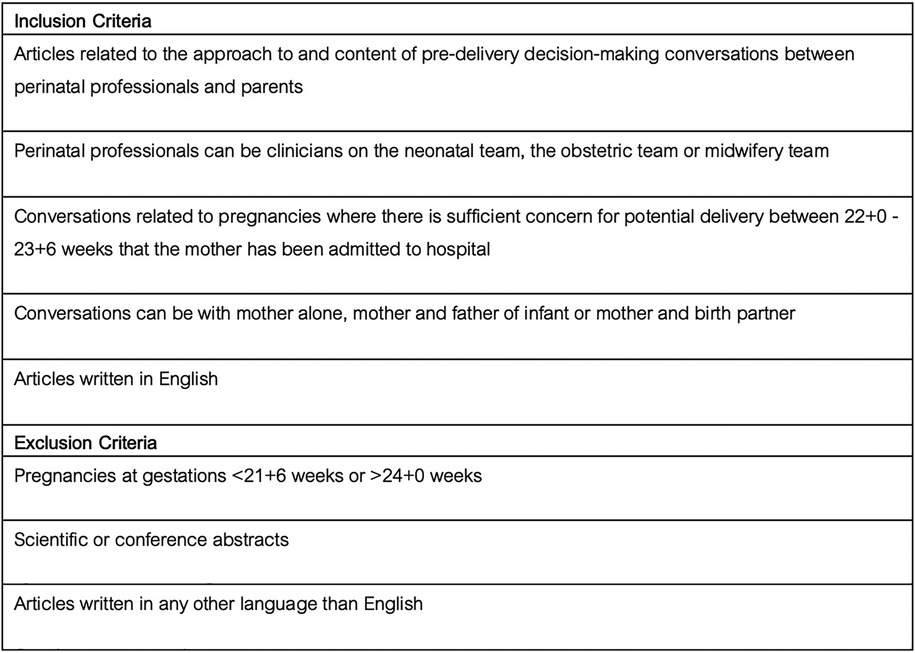

The SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention/phenomenon of Interest, Comparison, Evaluation) framework was used as a conceptualizing framework to formulate the review questions, keywords and search process (15, 16). The SPICE elements were outlined: Setting = Pregnancies at risk of delivery at periviable gestation (22 + 0 to 23 + 6 weeks); Perspective = Perinatal professionals involved in pre-delivery periviable delivery conversations with parents; Intervention (Phenomenon of interest) = The pre-delivery decision-making conversation; Comparison = No comparison; Evaluation = The approach to and the information topics included in pre-delivery decision-making conversations. Boolean operators were utilised to combine keywords and blocks. Additionally, the authors’ used the databases’ specific thesauri, truncation, and phrase searches to ensure the search was as comprehensive as possible. The search strategy was developed by JP and DMS with expert support from the hospital medical librarian. The search strategy (Figure 1) and inclusion/exclusion criteria (Figure 2) were agreed prior to conducting the search. The MEDLINE® (OVID) and Embase™ (OVID) databases were searched using the pre-agreed search strategy. Publications in English were eligible. Funding was not available for translation of articles published in other languages. The search was performed on 29th July 2024.

2.5 Study selection and critical appraisal

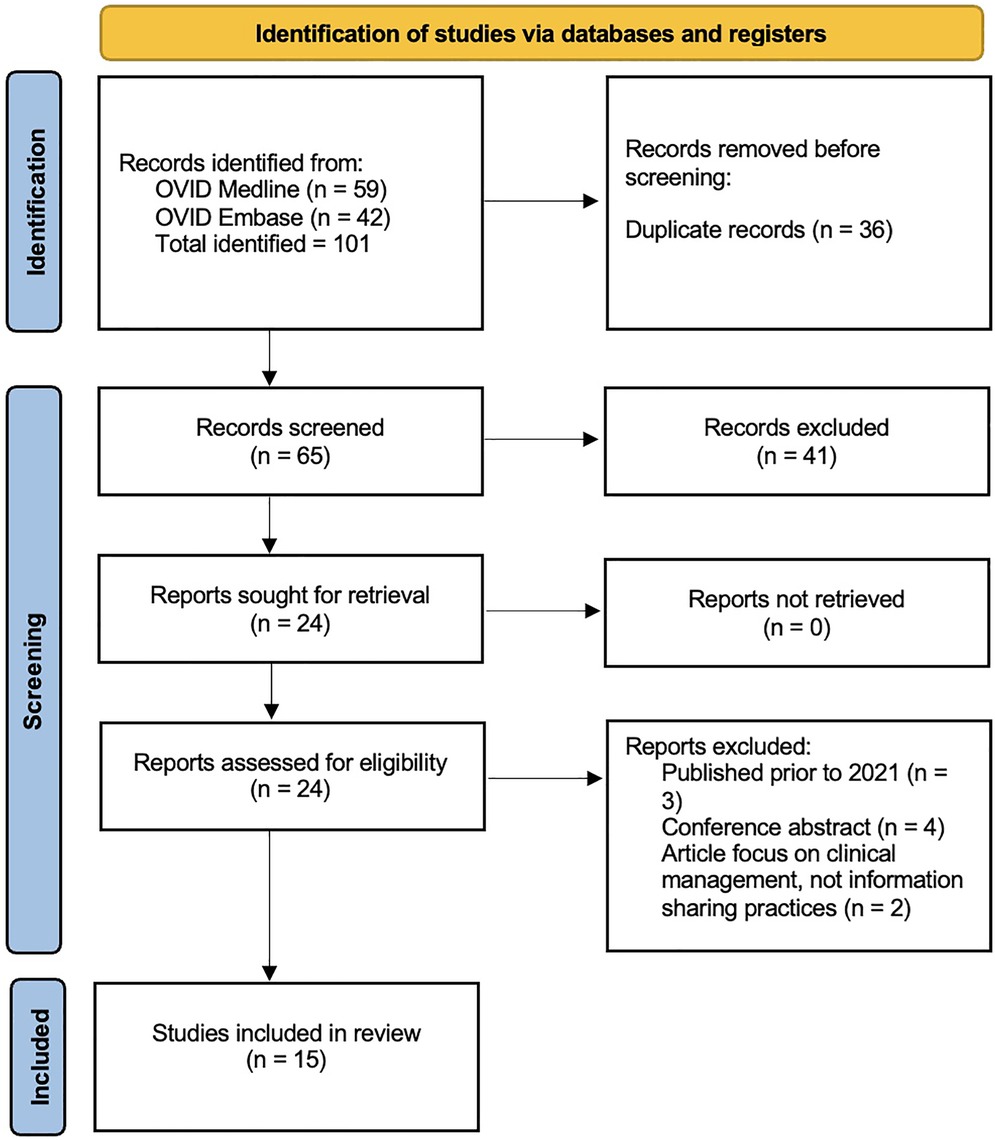

All articles identified by the initial search were screened for duplicates. The resultant collated list of articles had the title and abstract independently screened by J Peterson and C Graham. Those articles not relevant to the research question were excluded. This process was cross-checked using an inter-reliability assessment tool (Kappa) to assess the inclusion/exclusion decision-making for all studies identified in the initial search. This resulted in a list of articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria from the title and abstract. These articles were then retrieved and reviewed in full, with another Kappa assessment being conducted on all full articles reviewed. Reasons for exclusion of studies following full text review are provided in Supplementary File S2. The study selection process is summarised in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 3). A third reviewer (DM Smith) was available in the event of any disagreements.

Once the included articles were identified, data were extracted by J Peterson and C Graham. Data on study setting, sample size, country study was conducted, study design, outcome measures, findings, conclusions were collected using an electronic form. Analysis of the extracted data was performed using a thematic synthesis approach.

2.6 Quality assessment

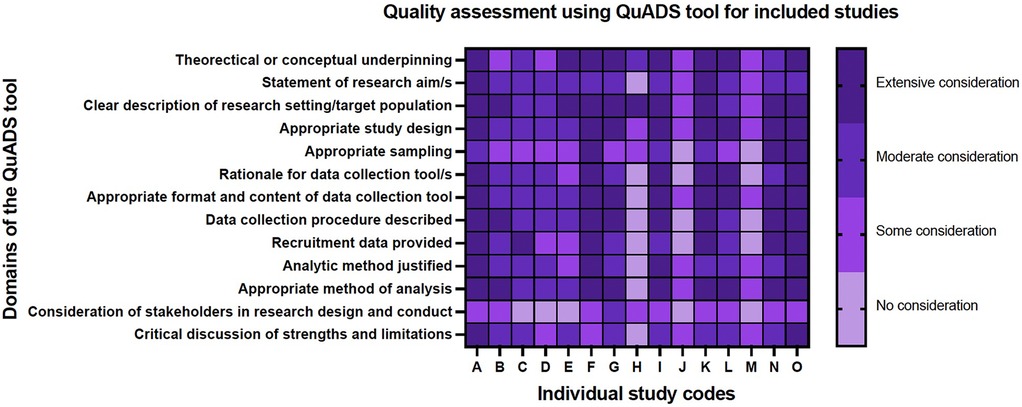

All studies included received a quality score as determined by two study team members (JP and CG) using the Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS) tool. The QuADS tool can be used to determine the methodological and reporting quality across a range of mixed- and multi-methods studies in health services research (17). A QuADS score was independently assessed by two reviewers (JP and CG). A Kappa score was calculated for the QuADS scores to ensure inter-rater reliability with regard to how quality is being assessed by the reviewers.

2.7 The analysis process

The included studies were read in full by JP and CG. Included studies underwent line by line analysis to identify key concepts for coding. Once all the included studies were coded, the data was reviewed to inductively identify themes and sub-themes around what information and how information is being shared between perinatal professionals and parents. The final written report provides a narrative evaluation and interpretation of the identified themes, outlining current strengths and weaknesses. Identification of the weaknesses in current periviable discussions will guide development of further future research for how to improve these important pre-birth conversations between perinatal professionals and parents. The final report has been written in accordance with PRISMA guidelines.

3 Results

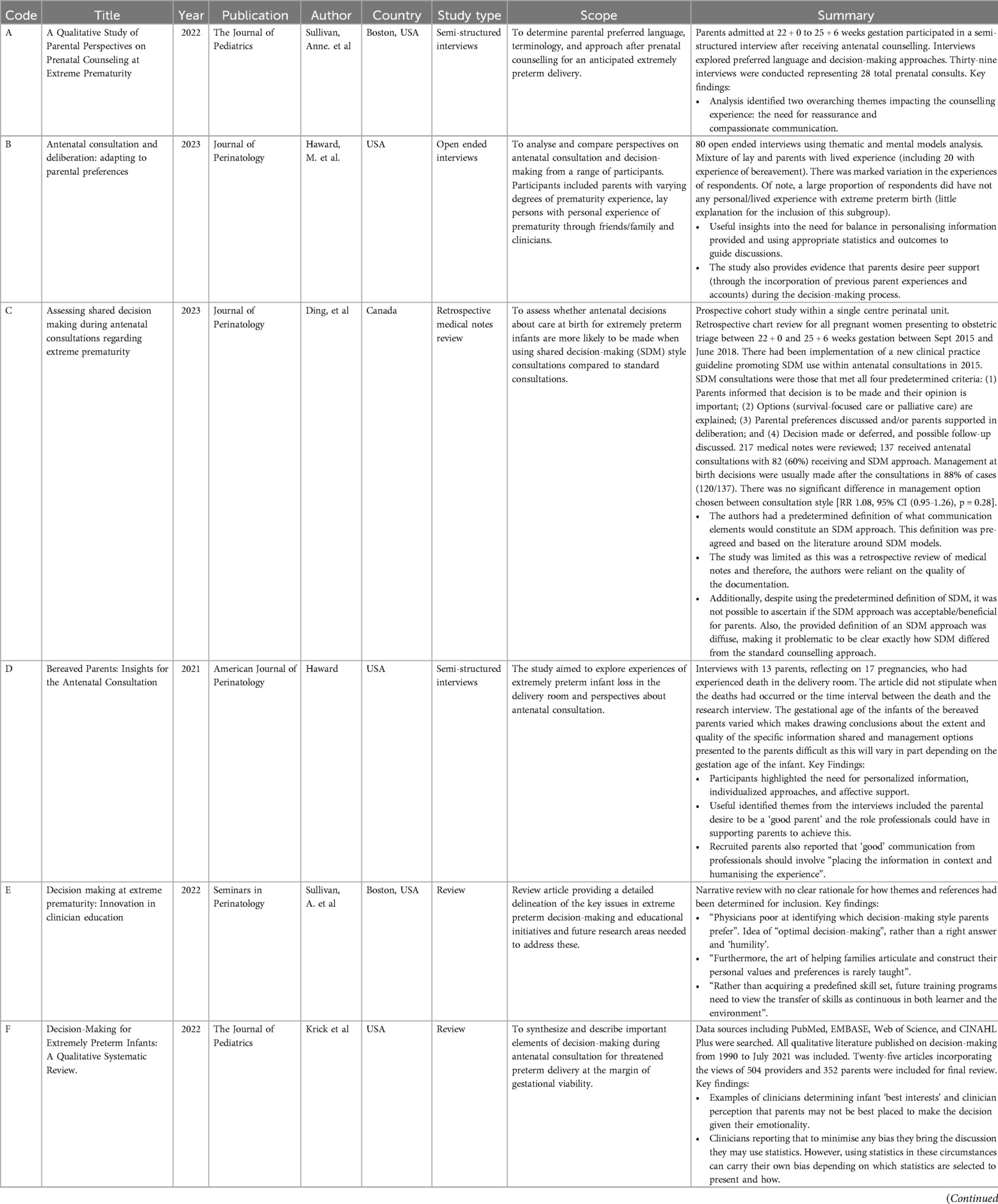

The initial search identified 101 articles (Figure 3). Following removal of duplicates and screening against the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 24 articles were identified for full-text review. Of these 24 articles, nine were excluded after full-text reading as they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria [published prior to 2021 (3 articles); conference abstract (4 articles); article focus on clinical management, not information sharing practices (2 articles)]. All excluded articles and reasons for exclusion can be viewed in Supplementary File S2. This resulted in 15 articles being included in the final review (Figure 3). Within the included articles there are three articles with the same first author (Table 1; Haward et al. (18–20). For clarity in the remainder of this review, the article code from Table 1 will be provided in brackets in cases where an article by Haward is discussed.

For quality assurance, all articles were screened by both JP and CG at each stage of the review process. There was substantial agreement between the two screening authors (JP and CG) with a Cohen's K score of 0.91 indicating 91% agreement when screening the titles and abstracts and 100% agreement after reviewing the full text articles. Any disagreement was resolved following discussion. The third author (DMS) was not required to resolve any disagreements.

3.1 Quality assessment

Overall, the included studies were of reasonable quality (Figure 4). Most studies provided appropriate background and context for their study and had selected an appropriate methodology with which to address their research question. Several studies contained minimal information about their sampling methods, for example, the Arzuaga parent survey study (21) the authors describe using convenience sampling from social media sites with no further discussion of why convenience sampling was chosen, or in the case of some of the summary review articles, whilst the article was referenced throughout, it was unclear how the topics discussed in their reviews had been determined (22, 23). The QuADS assessment also highlights the lack of stakeholder input into the design and conduct of these studies (Figure 4).

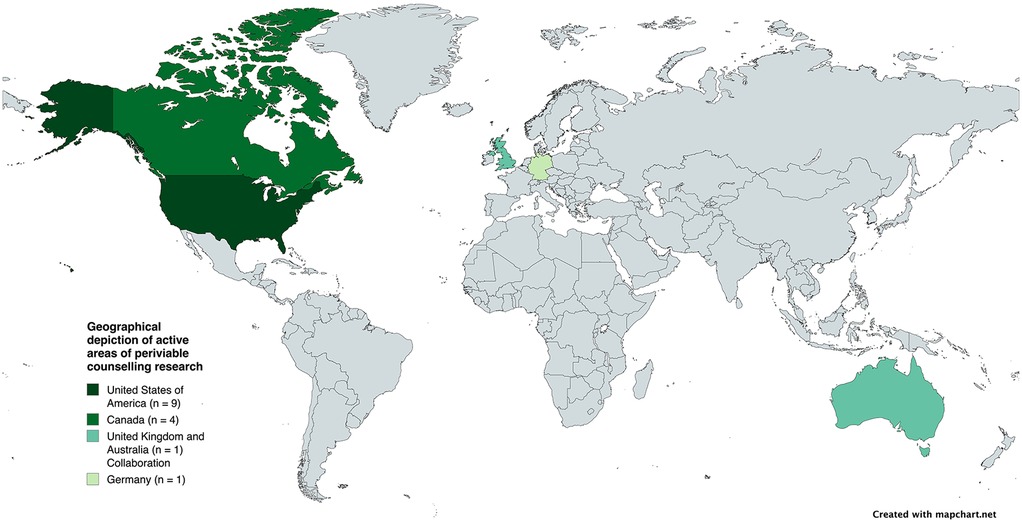

The 15 included articles comprised a range of qualitative methods (Table 1). These included interviews with parents (four studies), review articles (four studies), online surveys (three studies), discourse analyses of conversations between perinatal professionals and parents (two studies) and one retrospective review of medical notes. The included articles were all conducted in a small number of high-income countries (Figure 5). The majority were conducted in the United States of America (nine studies) and Canada (four studies). Only two of the included studies were conducted outside North America; one from Germany (an online survey of professionals) and one publication which was a collaboration between authors in United Kingdom and Australia (‘Best Practice’ review article).

The included articles provided perspectives from a range of perinatal medical professionals and parents with varied experiences of periviable birth—including parents of surviving children and parents whose babies died. There was minimal inclusion of the perspectives of midwifery or neonatal nurses or advanced neonatal nurse practitioners. Additionally, the views of siblings, the wider family or wider clinical teams (such as general paediatricians, community paediatricians or adult physicians specialising in the long-term management of adults born extremely preterm) were not represented in the available literature.

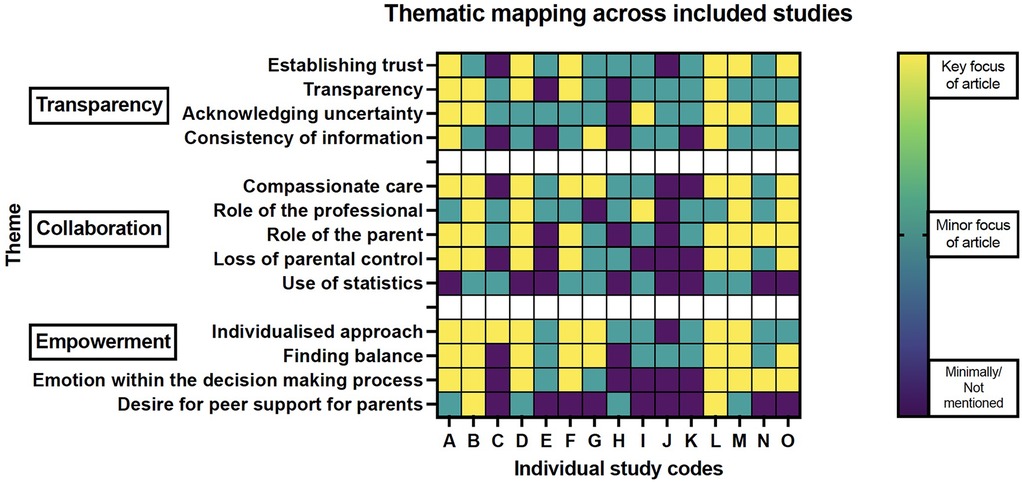

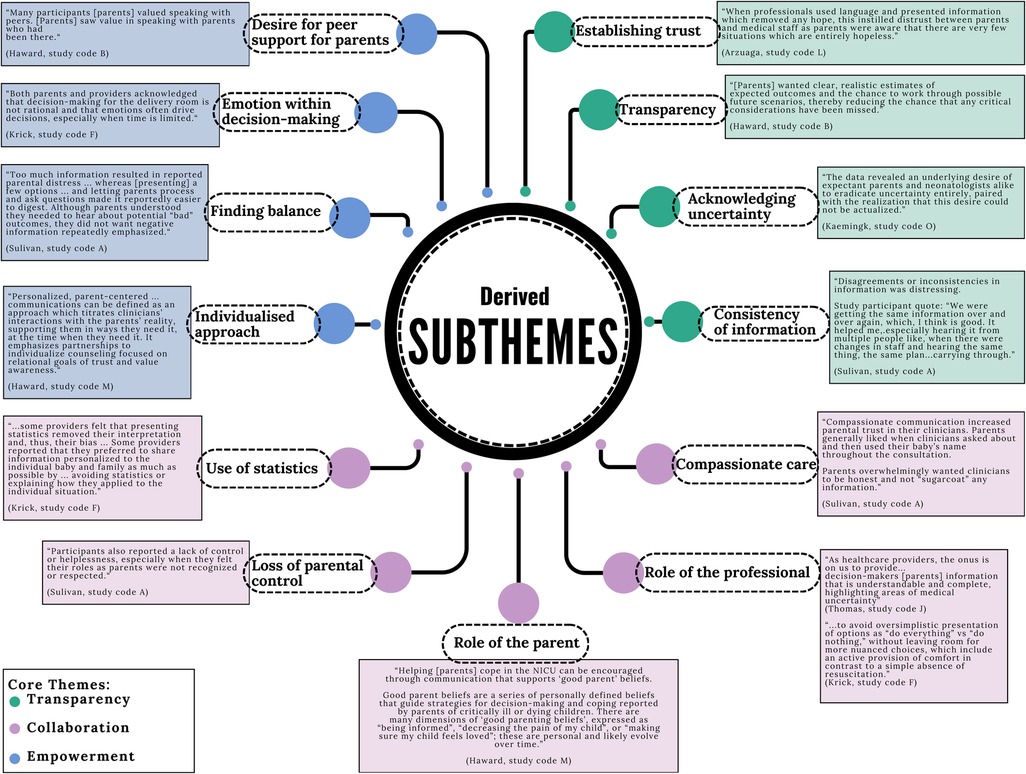

The diversity of qualitative methods used by the included studies allowed exploration of information sharing approaches and practices from multiple angles and provides additional strength for the subsequent core themes identified across these studies. There were three core themes identified: Transparency, Collaboration and Empowerment. Within these themes, there were thirteen subthemes as shown in Figures 6, 7.

3.2 Theme one: transparency

The theme of transparency was strongly prevalent throughout all the included studies (Figure 6). This core theme was established with each study finding data illustrative of multiple facets that make up the concept of transparency; which is, to be straightforwardly perceived. In the case of transparent communication this would allude to communication which does not seek to hide, or leave out certain, relevant pieces of information. Transparent communication allows for all pertinent elements of a topic to be laid out, discussed and considered and for trust to be built between those involved in the communication. The articles in the review presented data which supported various communication tools important in creating transparency within the pre-birth periviable conversation. For example, studies reported that parents valued access to information and to feel that this information was being consistently relayed by different members of the perinatal professional team (24). This consistency increased parental confidence that the team were being open and honest with them, and this built trust (19). The data also showed that parents appreciated the need for professionals to balance the information provided and to supply this information at a pace that matched the individual parent and circumstance (24). Parents desired reassurance that when professionals were discussing different considerations of the periviable birth journey with them (such as different management options at birth), that professionals were presenting all relevant information and options to them with an open conversation about what those options could look like and what the potential implications were likely to be (23). There was an acknowledgement that this was not merely a case of presenting all information and data to the parents, as this would have the potential to result in information overload. Rather, the studies illustrate a desire from parents for information to presented in alignment with their individual circumstances and an ability to humanise the information; for example, referring to their baby's name, being aware that their baby and themselves as parents exist within a wider family and social structure, detecting and responding to the prompts and priorities of the parent in the moment, rather than a predetermined agenda set by the professional.

“Acknowledging and sharing their hope assures parents that clinicians are on their side. Multiple domains of hope can co-exist, appear contradictory, and evolve as new knowledge is learned. Hope, however, does not prevent honesty…. reconciliation of hope and honesty requires skillful management of multiple co-existing hopes”.

- Haward, et al. (study code M)

A crucial element within the theme of transparency was for professionals to acknowledge the inherent uncertainty that comes with periviable birth (25). It remains difficult pre-birth for professionals to predict with any accuracy which periviable infants will survive and which will die (26). The data show that professional communication which attempts to remove hope from the conversation was associated with parental distrust of the professional as parents were aware there is evidence that some periviable infants can survive and therefore, there are very few periviable birth situations which are entirely devoid of hope (21). Instead, an acknowledgement of the uncertainty by the professional was conducive to creating a balanced discussion of the clinical information and the parents’ views and values; both key elements of achieving shared decision-making (20).

Discussion of uncertainty can be difficult for perinatal professionals. The Kaemingk, et al. article (study code O) (27) conducted discourse analysis of 25 recorded pre-birth periviable conversations between neonatologists and parents. Their analysis provides evidence that uncertainty within these conversations is actively managed by professionals using a variety of strategies. Some neonatologists attempted to manage the issue of uncertainty through increased blocks of information provision within the conversation. The effect of this was for the neonatologist's voice to dominate the conversation with little to no interaction from the parents, indicating potential overwhelm or disengagement. Conversely, professionals who addressed the uncertainty through acknowledging the limits of medical knowledge, accepting the presence of uncertainty in these periviable cases and holding hope with the parents were able to demonstrate transparency and build trust, aiding the process of meaningful involvement of parents in the decision-making process.

3.3 Theme two: collaboration

“As healthcare providers, the onus is on us to provide.. decision-makers [parents] information that is understandable and complete, highlighting areas of medical uncertainty”

- Thomas, study code J

The second theme identified clearly across the included studies was that of the role that the professional and the parent occupy within the pre-birth periviable conversation and how the interaction between these roles is enacted.

For perinatal professionals their perception of their role centred on the provision of clear information to the parents about the medical components of periviable birth needed to inform the decision-making process; such as, medical information regarding mortality and the short- and long-term medical consequences of being born in the periviable period. Across the included studies perinatal professionals reported that they had the role of ensuring the rational elements of the decision-making process were being considered (19, 27, 28). Studies demonstrated that perinatal professionals report that the heightened emotional state of the parents would influence their decision-making process and prevent them from making a rational decision (29). In order to adopt this more ‘rational’ stance within the conversation, some professionals relied on a variety of techniques, such as, avoidance of the topic of uncertainty, use of statistics and avoidance of nuance within the conversation (24, 27, 29). This was demonstrated through professionals presenting management options to parents as a dichotomy, rather than a spectrum of options; for example, presenting survival focused care as ‘doing everything’ and being in opposition with comfort care which is then the necessary opposite and becomes the ‘do nothing’ option (29). This is problematic as to have an in-depth discussion of the details and relative benefits and risks of each approach requires that the clinician can give a clear explanation of the process of comfort care at delivery in order that parents are able to picture what this would involve. Full descriptions of comfort care enable parents to name and discuss what this process could look like for them and their baby. Provision of high-quality comfort care at birth is an active process that requires senior perinatal professionals with experience in bereavement and compassionate care practices: it should not be constructed as a ‘do nothing’ approach. Additionally, presenting options as a dichotomy of ‘do everything’ or ‘do nothing’ can restrict the parents access to developing an individualised care plan for delivery room management. Rather than constructing this dichotomy, it may be beneficial for some parents to discuss the options for a stepwise progression of care for their baby. This could involve relatively simple supportive interventions after birth, such as intubation and surfactant, and continuation of intensive care is assessed continuously over the following days of their neonatal journey with provision of palliative care along that process (a ‘trial of life’ approach) with the professional and parental understanding that if the infant is not responding to intensive care and the burden of care is becoming excessive that care may be reorientated; such as in the case of severe respiratory failure or, severe morbidity concerns, for example, significant bilateral intraventricular haemorrhages (29, 30). Parents need perinatal professionals to be able to move away from dichotomous presentation of options and to be able to navigate uncertainty and nuance within the pre-birth conversation, in order to develop more detailed individualised birth plans for their baby.

Professionals expressed a potential for them to experience their own biases based on their previous clinical experiences of managing other periviable infants (28). Several of the included studies showed that perinatal professionals attempted to use statistics to overcome that bias with the justification utilising statistics removed their own personal interpretation of the situation, thus providing the parents with less biased information (28, 29). The use of statistics within periviable pre-birth discussions is complex (26). Data can vary depending on the source, the denominator and the framing. For example, survival rates can vary significantly depending on if local, national or international data is selected. Therefore, the selection of which specific statistics are presented to the parents has its own potential for introducing bias and may serve to have varied impacts on the decision-making process for both professionals and parents.

Professionals acknowledged their role in supporting parents through the decision-making process. Several studies demonstrated that some professionals aim to occupy a protective role and have concerns about causing increased parental distress through the provision of ‘false hope’ (24, 29). Studies reported that professionals could find it challenging to allow room for holding hope with parents and often felt that the by emphasising the risks of being born at periviability, that this could serve to minimise any false hope (29). The issue of false hope was not one that was echoed by the parents involved in the studies in this review. Parents understood that clinicians needed to provide them with a full picture of information and that some elements of this information would be distressing to hear. However, there was a consistent finding across the studies that parents valued honest and direct information which was not “sugar coated” (24). Parents also valued practitioners who were able to discuss the more distressing pieces of information without excessive emphasis or repetition.

Parents generally expressed that their role as parent placed them in a position of decision making authority for their baby and that they viewed the clinician as a facilitator to enable the consideration of medical information alongside helping the parents work through their reflections and reactions to the medical information, allowing supported time for the parents to incorporate this new information within their personal value systems and reach the best decision for their baby and their family (18, 21, 31). Parents valued having informed and experienced professionals who were able to have an established evidence base for the information that was being shared with them but preferred that the information was personalised and specific, as much as possible, to their individual baby and family circumstances, rather than a vague or generic use of statistics (19, 27).

The experience of having a periviable birth can be an unexpected and disorientating experience for many parents. Within the included studies parents reported experiencing a sense of loss of control or a feeling of helplessness (24). Perinatal professionals can hold an important role in ensuring that their periviable counselling approach takes into consideration the strong parental desire to be a ‘good parent’ (19, 20). Research shows that for parents of critically ill or dying children and there are several dimensions which constitute the role of the ‘good parent’. These are that parents desire to be informed about their child's condition, to be able to participate in decisions around their child's care, to be able to reduce any pain their child may experience and to ensure that their child feels loved (20). The extent to which these different components are expressed at any given point in time will differ depending on the parent and the circumstances. These constituent elements of the good parent role can be actualized through the pre-birth conversation provided professionals are cognizant of the importance of these elements to parents. Clear acknowledgement of their role as parent and specific descriptions of what parents can do with their baby that address those components of the ‘good parent’ should be included in pre-birth conversations (19). These could include descriptors of how parental contact with their baby can be facilitated at delivery, importance of parental touch and voice on the neonatal unit, bonding squares, parental updates and involvement in decisions around feeding and cares. Inclusion of detailed descriptions of ensuring comfort, avoiding pain and enabling the parent to provide love to their baby can all be integrated in the pre-birth conversation and can be included whether survival-focused or comfort care approach is deemed most appropriate.

3.4 Theme three: empowerment

“A common mistake physicians make is to assume that information is all that is needed to guide decision-making.”

- Kaemingk, et al. (study code O)

The third theme identified within this review was that of empowerment. This theme brings together four subthemes centred around different aspects of the power differential between parents and professionals within these conversations. These components are: (i) the need for an individualised approach, (ii) the need for balance within these conversations, (iii) an appreciation of the role that emotion holds within the decision-making process and iv. the desire from parents for peer support during this decision-making process. Several of the studies included in the review emphasised the importance for parents that the communication they received from their professional team had been personalised to their specific circumstances (Figure 6). This made engagement with that information more accessible and established a sense of partnership between parents and professionals. This is necessary to promote trust and to facilitate discussion of the parent's values and priorities pertinent to making a decision about management at birth. Knowledge of the individuality of the parent can additionally serve to distil them in the mind of the professional as an individual autonomous person within the conversation (32).

Many of the studies commented on the need for balance within these pre-birth conversations (Figure 6). The need for balance existed across multiple levels within the conversation. This included balance within the content of the information discussed, ensuring that all relevant management options were outlined and fully discussed with parents, including options for comfort care (24, 27). As stated, the need for balancing hope alongside provision of realistic information was important to parents across the studies. Where professionals were unable to navigate this balance, there was distrust and disengagement from parents (21).

The included studies also supported the need for balance in the value placed on the respective roles of parent and professional within the conversation. Given the ethical complexity of periviable birth management decisions, it is important that parents are given facilitated time and opportunity to explore their moral values and priorities in relation to the individualised medical information provided by professionals. Within these pre-birth conversations professionals should dedicate time to facilitate exploration of the parental perspective, rather than allowing the pre-birth conversation to be dominated only with the provision of the factual medical information (20).

Six of the included studies also contained reference to a desire from parents for peer support (18–22, 24). This was generally expressed as expectant parents wishing that they had been able to access the experiences and reflections of other parents who had been through a similar periviable birth (21). It was felt that hearing from parents who have experienced periviable birth could provide expectant parents with reassurance that the overwhelm and uncertainty about the decisions that they were facing was something that had been experienced by other parents. Peer support also had the potential to provide more comprehensive information about what different periviable journeys may look like, particularly around options and elements of care that professionals can find difficult to articulate, such as the specifics of comfort care and the dying process (24).

Along these lines several of the studies commented on the role that emotion occupies within the decision-making process (Figure 6). There was an acknowledgement that professionals may feel that the heightened emotional state of the parents undermines or precludes the parent from being able to make a rational decision (28). Other studies within the review highlighted the necessary role that emotion has when making significant decisions and that emotion is a useful method through which to explore the various issues and considerations relevant to that decision (19, 24, 29). By acknowledging and discussing the emotions being expressed by the parent the concerns and hopes held by that parent and family can be better delineated and incorporation of these can result in a more individualised care plan being determined.

4 Discussion

This review has outlined three core themes of transparency, collaboration and empowerment that should be integrated within pre-birth periviable conversations between perinatal professionals and parents to improve the quality and impact of these discussions. This review has demonstrated that parents value clear, accurate and realistic information from perinatal professionals. There was an acceptance that parts of this information pertaining to periviable birth will be distressing and difficult to hear, but that being provided with all pertinent information was important to enabling parents to understand all management options available to them; for example, professionals providing the option for and detail about comfort care, rather than avoiding or omitting this. Parents desired accurate information tailored to their circumstances and delivered in an individualised and compassionate way. Whilst perinatal professional may not endeavour to conduct insensitive discussions with parents, some of the communication techniques described in the studies (removing hope, not acknowledging or empowering the role of the ‘good parent’, avoiding uncertainty and emotions within decision-making) which are used by professionals could prevent effective information sharing and serve to compound the trauma already being experienced by parents facing periviable birth (33).

The findings indicate that whilst these pre-birth periviable conversations are complex, there is scope to improve them through modifications to counselling approaches and professional educational strategies. These include providing professionals with techniques to be able to talk about and navigate uncertainty with parents, acknowledging the limits of medical knowledge and being able to engage with and hold space for hope within these discussions. Healthcare professional education programmes have approaches and appraisal methods which focus on the student providing the one ‘right’ answer. However, clinical medicine involves a myriad of grey-scale decisions and whilst there is professional awareness of the need for shared decision-making, this cannot be actualised without educational strategies to increase perinatal professionals’ empathy, compassion and the ability to sit with uncertainty. The evolving body of research around narrative medicine education sessions and programmes speaks to the increasing understanding and appreciation for these skills within clinical medicine (34–36). Narrative medicine is an approach which utilises art, music, poetry and writing to increase skills of listening, reflection, empathy and human connection within clinical medicine (37–39). These skills are needed to deliver individualised, compassionate care to patients and align well with the three core themes identified in this review.

Periviable birth can be a trauma-inducing experience for parents due to the significant uncertainty and loss of control that it confers over their immediate circumstances and imagined future. After presenting to hospital in threatened or confirmed periviable labour, parents encounter numerous perinatal professionals who are providing information on an evolving and uncertain labour and delivery process. Trauma can occur where there is “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individuals functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional or spiritual wellbeing” (40) (pg 7). Periviable birth certainly sits within this definition. A trauma-informed approach to communication aims to recognise situations which may be traumatising, work to avoid exacerbating or retraumatising and instead to promote psychological safety, choice and control (40, 41). The findings of this review align and overlap with the six principles of trauma-informed care (Figure 8). This indicates the role that trauma-informed care approaches could have in improving the quality and experience of pre-birth periviable conversations for parents by empowering them to have access to information (control), have their perspectives and views on the information discussed and incorporated into decisions (choice) and transparency and compassion in the way the conversation is conducted (psychological safety). The need for trauma-informed care to be integrated within perinatal services is being increasingly recognised and called for (33, 42, 43). Specific guidance on trauma-informed practice from the United Kingdom's Office for Health Improvements and Disparities outlines that using this approach in clinical practice is “a means for reducing the negative impact of trauma experiences and supporting mental and physical health outcomes” (41). To successfully instil the themes identified within this review, and trauma-informed principles more generally, into perinatal clinical practice there are numerous considerations for service provision design and future research. Service provision changes may include coordination of midwifery, obstetric and neonatal team approaches to ensure clear, individualised and consistent information is conveyed to parents from each team. Services could consider co-creation of information sources for parents which include accounts from previous parents who have experienced periviable birth. This would work toward acknowledging the peer support that was desired by parents within the included studies. Services should aim to have support for perinatal professionals to prevent and address issues of burnout, compassionate stress and secondary traumatic stress that can occur through providing care to periviable infants and their families (40). Future research is needed to determine effective educational methods for ensuring perinatal professionals can navigate conceptually complex topics, such as uncertainty, within conversations with parents.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The results of this review are strengthened through the systematic methods which were used to search and screen the literature. Additionally, by using a recent date range for inclusion (2021–2024) this review has focused on the latest approaches to periviable pre-birth conversations. Therefore, the findings reflect contemporary practice and increase the relevance to perinatal professionals.

This review is limited by the restricted geographical areas and cultures that the research was conducted in. All studies were conducted in Western societies, with the majority being conducted in the USA and Canada. Some of the individual studies also acknowledged that individuals who agreed to participate in the study were from a fairly homogenous ethnic and economic grouping (Caucasian, college educated, mothers) (21). The results of this review may, therefore, not represent the views and priorities of parents and practitioners from other areas of the World working within different cultures and societies and varied healthcare systems. Additionally, many of the articles included in the review included a wide gestational age range (22 + 0 to 25 + 6 weeks) in their definition of ‘extremely preterm’ (or periviable). When considering survival and morbidity risks, this creates a starkly heterogenous group of infants and outcomes. This variation in survival and morbidity outcomes would be expected to impact the pre-birth conversation. The reasons for the wide gestational age ranges are poorly described in the included studies. One explanation could be that international professional frameworks differ in their definitions and recommended approaches to periviable birth. Professional guidance from the American Association of Paediatrics recommends an individualised, holistic assessment of the infant, even at 24 + 6 weeks gestation (44). Whereas the British Association of Perinatal Medicine recommends survival-focused care from 24 + 0 weeks (3). Given that the majority of the included articles were conducted in the USA, this may account for the broad gestational age ranges within the included studies.

5 Conclusion

This review focused on the information sharing and communication practices for the pre-birth discussion (or ‘counselling’) between perinatal professionals and parents facing periviable birth. From the available literature, three core themes have been identified that were present across the included studies and have been demonstrated to map onto the six principles of trauma-informed care. The pre-birth periviable conversation occurs in, often unexpected, trauma-inducing circumstances for parents. Perinatal professionals involved in these conversations hold a critical role in how the narrative develops for parents around their understanding of periviable birth, what they potentially will face as a family, what their options are and what level of connection and compassion they can expect to receive from their perinatal team. Perinatal professionals need to be better equipped psychologically and educationally to understand and incorporate a trauma-informed approach to their counselling practices and the core themes identified in this review should form the basis for future research into these pivotal and nuanced conversations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EJ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DS: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study received funding from the Peter Mount Pump Prime award administered through Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and from the North West Neonatal Operational Divisional Network. The funders were not involved in the running of the study or in writing or approval of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Olivia Schaff, Medical Librarian for her expert knowledge and support in defining and performing the search strategy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction Note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fped.2025.1640856.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2025.1553040/full#supplementary-material

Footnote

1. ^This is clinically not accurate information. Intervention can be offered. The risks and benefits in each individual case should be discussed with the parents. It is not true that nothing can be offered at this gestation.

References

1. Manley B, Doyle L, Davies M, Davis P. Fifty years in neonatology. J Paediatr Child Health. (2015) 51:118–21. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12798

2. British Association of Perinatal Medicine. The management of babies born extremely preterm at less than 26 weeks of gestation (2008). Available at: https://www.bapm.org/resources/16-the-management-of-babies-born-extremely-preterm-atless-than-26-weeks-of-gestation (Accessed October 23, 2024).

3. British Association of Perinatal Medicine. Perinatal management of extreme preterm birth before 27 weeks of gestation (2019). Available at: https://www.bapm.org/resources/80-perinatal-management-of-extreme-preterm-birthbefore-27-weeksof-gestation-2019 (Accessed October 23, 2024).

4. Dagle JM, Rysavy MA, Hunter SK, Colaizy TT, Elgin TG, Giesinger RE, et al. Cardiorespiratory management of infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation: the Iowa approach. Semin Perinatol. (2022) 46:151545. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151545

5. Janvier A, Bourque CJ, Pearce R, Thivierge E, Duquette LA, Jaworski M, et al. Fragility and resilience: parental and family perspectives on the impacts of extreme prematurity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2023) 108:575–80. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2022-325011

6. Dance A. Survival of the littlest: the long-term impacts of being born extremely early. Nature. (2020) 582:20–3. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01517-z

7. Mills M, Cortezzo D. Moral distress in the neonatal intensive care unit: what is it, why it happens, and how we can address it. Front Pediatr. (2020) 8:581. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00581

8. European Academy of Paediatric Societies (EAPS). Conference Programme (Agenda 19 October 2024) (2024). Available at: https://eaps2024.kenes.com/programme-at-a-glance/ (Accessed October 07, 2024).

9. The Women's, The Royal Women's Hospital. Cool Topics 2023 Shines a Light on Neonatal Research Progress. Parkville, VIC: The Women's, The Royal Women's Hospital (2023). Available at: https://www.thewomens.org.au/news/cool-topics-2023-shines-a-light-on-neonatal-research-progress

10. Tiny Baby Collaborative Group. Tiny Baby Collaborative (2023). Available at: https://www.tinybabycollaborative.org/ (Accessed October 07, 2024).

11. Smela B, Toumi M, Swierk K, Francois C, Biernikiewicz M, Clay E, et al. Rapid literature review: definition and methodology. J Mark Access Health Policy. (2023) 11:2241234. doi: 10.1080/20016689.2023.2241234

12. Stevens A, Hersi M, Garritty C, Hartling L, Shea BJ, Stewart LA, et al. Rapid review method series: interim guidance for the reporting of rapid reviews. BMJ EBM. (2024) 30:118–23. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2024-112899

13. Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, et al. Cochrane rapid reviews methods group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. (2021) 130:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007

14. Peterson J, Graham C, Southwood G, Johnstone ED, Mahaveer A, Smith DM. PeriviAble DeLiveries: ALIgning PArental aNd PhysiCian PrioritiEs (ALLIANCE). PROSPERO (2022). Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42022300099 (Accessed October 11, 2024).

15. Booth A. Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech. (2006) 24:355–68. doi: 10.1108/07378830610692127

16. Laher S, Hassem T. Doing systematic reviews in psychology. S Afr J Psychol. (2020) 50:450–68. doi: 10.1177/0081246320956417

17. Harrison R, Jones B, Gardner P, Lawton R. Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): an appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:144. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06122-y

18. Haward MF, Lorenz JM, Janvier A, Fischhoff B. Antenatal consultation and deliberation: adapting to parental preferences. J Perinatol. (2023) 43:895–902. doi: 10.1038/s41372-023-01605-8

19. Haward MF, Lorenz JM, Janvier A, Fischhoff B. Bereaved parents: insights for the antenatal consultation. Am J Perinatol. (2021) 40:874–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731651

20. Haward MF, Payot A, Feudtner C, Janvier A. Personalized communication with parents of children born at less than 25 weeks: moving from doctor-driven to parent-personalized discussions. Semin Perinatol. (2022) 46:151551. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151551

21. Arzuaga BH, Holland E, Kulp D, Williams D, Cummings CL. Maternal preferences for approach and language use during antenatal counseling at extreme prematurity: a pilot study. J Neonatal. (2021) 35:122–30. doi: 10.1177/09732179211035125

22. Yeoh M, Rafferty S, Saw C, Beedie J, Davis JW. Fifteen-minute consultation: outcomes of the extremely preterm infant (<27 weeks): what to tell the parents. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. (2023) 108:163–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321178

23. Sullivan A, Cummings CL. Decision making at extreme prematurity: innovation in clinician education. Semin Perinatol. (2022) 46:151529. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151529

24. Sullivan A, Arzuaga B, Luff D, Young V, Schnur M, Williams D, et al. A qualitative study of parental perspectives on prenatal counseling at extreme prematurity. J Pediatr. (2022) 251:17–23.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.09.003

25. Thomas S, Asztalos E. Gestation-based viability-difficult decisions with far-reaching consequences. Children (Basel). (2021) 8:593. doi: 10.3390/children8070593

26. Peterson J, Smith DM, Johnstone ED, Mahaveer A. Perinatal optimisation for periviable birth and outcomes: a 4-year network analysis (2018–2021) across a change in national guidance. Front Pediatr. (2024) 12:1365720. doi: 10.3389/fped.2024.1365720

27. Kaemingk BD, Carroll K, Thorvilson MJ, Schaepe KS, Collura CA. Uncertainty at the limits of viability: a qualitative study of antenatal consultations. Pediatrics. (2021) 147:e20201865. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1865

28. Schneider K, Muller J, Schleusner E. German obstetrician’s self-reported attitudes and handling in threatening preterm birth at the limits of viability. J Perinat Med. (2023) 51:1097–103. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2022-0547

29. Krick JA, Feltman DM, Arnolds M. Decision-making for extremely preterm infants: a qualitative systematic review. J Pediatr. (2022) 251:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.07.017

30. British Association of Perinatal Medicine. Recognising Uncertainty: An Integrated Framework for Palliative Care in Perinatal Medicine. A BAPM Framework for Practice. British Association of Perinatal Medicine (2024). Available at: https://www.bapm.org/resources/palliative-care-in-perinatal-medicine-framework

31. Kim BH, Feltman DM, Schneider S, Herron C, Montes A, Anani UE, et al. What information do clinicians deem important for counseling parents facing extremely early deliveries?: results from an online survey. Am J Perinatol. (2021) 40:657–65. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1730430

32. Entwistle V, Watt I. Treating patients as persons: a capabilities approach to support delivery of person-centered care. Am J Bioeth. (2013) 13:29–39. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.802060

33. Benton M, Wittkowski A, Edge D, Reid HE, Quigley T, Sheikh Z, et al. Best practice recommendations for the integration of trauma-informed approaches in maternal mental health care within the context of perinatal trauma and loss: a systematic review of current guidance. Midwifery. (2024) 131:103949. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2024.103949

34. Chen P-J, Huang C-D, Yeh S-J. Impact of a narrative medicine programme on healthcare providers’ empathy scores over time. BMC Med Educ. (2017) 17. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0952-x

35. Patel P, Hancock J, Rogers M, Pollard S. Improving uncertainty tolerance in medical students: a scoping review. Med Educ. (2022) 56:1163–73. doi: 10.1111/medu.14873

36. Loy M, Kowalsky R. Narrative medicine: the power of shared stories to enhance inclusive clinical care, clinician well-being, and medical education. Perm J. (2024) 28:93–101. doi: 10.7812/TPP/23.116

37. Charon R. At the membranes of care: stories in narrative medicine. Acad Med. (2012) 87:342–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182446fbb

38. Columbia University Department of Medical Humanities and Ethics. The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine. New York, NY: Columbia University Department of Medical Humanities and Ethics (2016). Available at: https://www.mhe.cuimc.columbia.edu/narrative-medicine/principles-and-practice-narrative-medicine

39. Schuelke T, Rubenstein J. Dignity therapy in pediatrics: a case series. Palliat Med Rep. (2020) 1:156–60. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0015

40. Centre for Early Child Development, B. B. S. A Good Practice Guide to Support Implementation of Trauma-informed Care in the Perinatal Period. Centre for Early Child Development (2021). Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/BBS-TIC-V8.pdf

41. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, Gov. U. Working Definition of Trauma-informed practice. London: United Kingdom Government (2022) Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-definition-of-trauma-informed-practice/working-definition-of-trauma-informed-practice#:~:text=Trauma%2Dinformed%20practice%20is%20an,biological%2C%20psychological%20and%20social%20development

42. Ockenden D. Findings, Conclusions and Essential Actions from the Independent Review of Maternity Services. London: The Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust (2022). Available at: https://www.ockendenmaternityreview.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FINAL_INDEPENDENT_MATERNITY_REVIEW_OF_MATERNITY_SERVICES_REPORT.pdf

43. Sanders M, Hall S. Trauma-informed care in the newborn intensive care unit: promoting safety, security and connectedness. Nat Portfolio. (2017) 38:3–10. doi: 10.1038/jp.2017.124

Keywords: neonates, extreme preterm, periviable, resuscitation, counselling, trauma and maternity care

Citation: Peterson J, Graham C, Johnstone ED, Mahaveer A and Smith DM (2025) A rapid review of periviable (22 + 0 to 23 + 6 weeks) counselling practices and the need for a trauma-informed care approach. Front. Pediatr. 13:1553040. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1553040

Received: 29 December 2024; Accepted: 5 May 2025;

Published: 22 May 2025;

Corrected: 23 June 2025.

Edited by:

Fu-Sheng Chou, Loma Linda University, United StatesReviewed by:

Susanne Tippmann, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, GermanyMyuri Sivanthan (Manogaran), University of Ottawa, Canada

Copyright: © 2025 Peterson, Graham, Johnstone, Mahaveer and Smith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: J. Peterson, amVubmlmZXIucGV0ZXJzb25AaG90bWFpbC5jby51aw==

†ORCID:

E. D. Johnstone

orcid.org/0000-0001-9732-8544

J. Peterson

J. Peterson C. Graham

C. Graham E. D. Johnstone1,4,†

E. D. Johnstone1,4,† A. Mahaveer

A. Mahaveer D. M. Smith

D. M. Smith