- Department of Neonatology, The Second Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

Culler-Jones syndrome (CJS) (OMIM: 615849) is a rare genetic condition characterized by considerable phenotypic variability. This case reports a 5-day-old male neonate who presented with postaxial polydactyly, growth restriction, and recurrent epileptic seizures. A thorough clinical workup, including laboratory investigations, imaging, and genetic analysis, resulted in a confirmed diagnosis of Culler-Jones syndrome. Peripheral blood samples collected from the proband and his parents were used for DNA extraction. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) identified a heterozygous nonsense variant in the GLI2 gene, [c.2137(exon13)G>T/p.(E713,857) (NM_001374353)], which was subsequently validated by Sanger sequencing and determined to be maternally inherited. This mutation has not been previously documented in the literature. By detailing the clinical presentation, genetic findings, and relevant context, this case report aims to broaden the known phenotypic spectrum of Culler-Jones syndrome and support clinicians in early detection and diagnosis.

1 Introduction

Culler-Jones syndrome (CJS; OMIM: 615849) is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the GLI2 gene on chromosome 2q14 (1). The syndrome is characterized by incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity, resulting in significant clinical heterogeneity and frequent diagnostic uncertainty. Core clinical features include hypopituitarism, postaxial polydactyly, seizures, intellectual disability, and growth impairment. Other manifestations described in some patients include craniofacial abnormalities, such as midfacial hypoplasia, cleft lip or palate, ptosis, and microcephaly, as well as genital anomalies like micropenis and cryptorchidism (2, 3). Recent case reports from various regions have continued to broaden the recognized phenotypic spectrum of the disorder, yet many aspects of CJS remain insufficiently defined. Interpretation of GLI2 variants is further complicated by the presence of certain mutations in the general population that lack clear clinical consequences, as well as by environmental factors that influence phenotypic expression (4–6). The heterozygous GLI2 variant identified in our patient [c.2137(exon13)G>T/p.(E713,857), NM_001374353] has not been previously documented. This case contributes to the expanding clinical and genetic understanding of CJS and underscores the value of genetic testing for accurate diagnosis and early intervention.

2 Case report

The proband, a 5-day-old male neonate, was admitted to the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University in October 2024 with a two-day history of generalized jaundice affecting the skin and mucous membranes. At the time of admission, the mean transcutaneous bilirubin level measured in the obstetrics department was 315 μmol/L. He was subsequently referred to the neonatology unit and hospitalized with a preliminary diagnosis of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia.

He was the second child of healthy, non-consanguineous parents. Delivery occurred via cesarean section at 37 + 3 weeks of gestation, and his birth weight was 2.63 kg. Polydactyly of all four extremities was noted at birth. There was no history of asphyxia, cyanosis, or need for resuscitation. The mother, who was 145 cm tall, also had bilateral postaxial hexadactyly. She reported no gestational diabetes and denied exposure to teratogens, toxins, or radiation during pregnancy. The patient's older sibling had died at 6 months of age due to congenital heart disease and pneumonia (further details unavailable). The maternal aunt had experienced multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes, including two miscarriages, and several maternal relatives also had polydactyly. The father was clinically healthy and 173 cm tall.

On admission, physical examination revealed: temperature 36.7 °C, heart rate 140 bpm, respiratory rate 35 breaths/min, and SpO₂ 95%. Anthropometric measurements included length 46 cm, head circumference 34 cm, chest circumference 32 cm, and weight 2.49 kg. The infant was alert and appropriately responsive. Significant findings included diffuse jaundice, scleral icterus, and normal primitive reflexes without pathological signs. Limb tone was normal. Postaxial polydactyly was present in all four limbs, with a total of 24 digits (Figures 1A–D).

Figure 1. (A–D) Show the child's right hand, left hand, left foot, and right foot in sequence, all of which exhibited hexadactyly (six fingers/toes).

Laboratory and imaging assessments showed unremarkable results for complete blood count, arterial blood gas analysis, chest radiography, echocardiography, and abdominal ultrasonography (liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen). Liver function testing revealed total bilirubin 254.3 μmol/L, direct bilirubin 13.7 μmol/L, and indirect bilirubin 240.6 μmol/L (Table 1). Cranial ultrasound was normal. Symptomatic management was initiated, including thermal support, adequate feeding, and phototherapy. On the second day of hospitalization at 14:37, the patient experienced an episode of bradycardia with a heart rate below 60 bpm, accompanied by profound oxygen desaturation. Immediate resuscitation was initiated, and by 14:39, cardiac activity had stabilized at 105–115 bpm, with oxygen saturation improving to 93%–95%. Mechanical ventilation was commenced thereafter. Following resuscitation, the infant demonstrated weak spontaneous breathing, sluggish pupillary reactions, reduced responsiveness, involuntary limb tremors, and increased muscle tone. Despite treatment with phenobarbital and midazolam, seizure activity persisted.

The child remained in critical condition throughout a prolonged hospitalization of more than 5 months, requiring multiple episodes of intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, with no successful attempts at weaning. Neurologic function remained severely impaired, characterized by minimal responsiveness, recurrent seizures, hypertonia, and oromotor dysfunction. Because of an inability to suck or swallow, he required nasogastric feeding with preterm formula. Oral secretions were thick and abundant. Antiepileptic therapy, including levetiracetam and phenobarbital, provided only limited clinical improvement.

Serial laboratory evaluations, including haematology, infection markers, blood cultures, electrolytes, plasma ammonia, pituitary hormones (growth hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone), insulin-like growth factor-1, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, prolactin, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis, were all within normal limits (Table 1).

Electroencephalography (EEG) showed a background dominated by diffuse, low- to medium-amplitude 2–3 Hz delta activity, generally symmetric between hemispheres. These waves were not suppressed, and scattered low-amplitude fast waves were present across leads. Sleep architecture was poorly defined, with no clear sleep vertex waves or spindles, and the sleep–wake cycle was difficult to distinguish. During sleep, medium- to high-amplitude diffuse slow waves mixed with abundant spike-and-slow waves, spikes, and sharp-and-slow waves were observed, predominantly in the bilateral frontal and anterior temporal regions, with right-sided predominance. A smaller amount of epileptiform activity was also present during wakefulness. A 24-hour ambulatory EEG further demonstrated a diffuse slowing of the background. During sleep, nearly continuous discharges, including spike-and-slow waves, sharp waves, and sharp-and-slow waves, were concentrated in the bilateral anterior head regions, with greater prominence on the right (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The 24-hour ambulatory electroencephalogram (EEG) for the child exhibiting abnormal findings. The background was composed of diffuse slow waves. During sleep, continuous discharges (approaching persistent discharges) of diffuse slow waves mixed with a large number of spike-slow waves, sharp waves, and sharp-slow waves were noted, occuring primarily in the bilateral anterior head regions, with right anterior predominance.

Brain MRI revealed symmetric short T1 signals in the bilateral basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebellar peduncles, along with T1 hyperintense signals in the bilateral dentate nuclei. The pituitary gland showed normal morphology and structure (Figures 3A–F). These symmetric abnormalities in deep brain structures suggest possible deposition of metabolites or minerals. However, evaluations for hereditary metabolic diseases, including mitochondrial encephalopathies and amino acid or organic acid metabolism disorders, were unremarkable.

Figure 3. (A–C) T1-weighted axial images. (A) Symmetric slightly hyperintense signals on T1WI are noted in the bilateral basal ganglia and thalamus. (B) Symmetric slightly hyperintense signals on T1WI are observed in the cerebral peduncles. (C) Symmetric slightly hyperintense signals on T1WI are seen in the pontine brachia. (D–F) T1-weighted coronal images. Symmetric slightly hyperintense signals on T1WI in the aforementioned regions are similarly demonstrated.

Whole-exome sequencing (Figures 4A–E) identified a heterozygous nonsense variant in GLI2 [NM_001374353: c.2137(exon13)G>T/p.(E713,857)] located at chr2:121744085. Segregation analysis by Sanger sequencing confirmed maternal inheritance of the variant, while the father carried the wild-type allele. Integrating the clinical presentation, neuroimaging findings, and genetic results, the patient was diagnosed with Culler-Jones syndrome with severe neurological involvement. Given the poor prognosis and ongoing clinical decline, the family elected to discontinue intensive medical care, and the infant was discharged home.

Figure 4. A table summarizing the GLI2 mutation types and mutation sites of the child and his parents (A). The heterozygous c.2137 (exon13) G>T [p.(Glu713Ter,857)] mutation was identified in the child (B). The forward sequencing result for the patient's father (WT) (C). The forward sequencing result for the patient's mother, revealing the presence of the heterozygous c.2137 (exon13) G>T [p.(Glu713Ter,857)] mutation (D). Family pedigree and electropherogram of heterozygous c.2137 (exon13) G>T [p.(Glu713Ter,857)] mutation in the GLI2 gene. Full-black filled box indicates index case with Culler-Jones syndrome phenotype, shaded boxes indicate mother who are also heterozygous for the identical mutation with incomplete phenotype, empty box indicates father with wild type, empty box with a diagonal line indicates the deceased elder brother (E).

3 Results

Based on the clinical presentation, ancillary examinations, and molecular findings, the patient was diagnosed with Culler-Jones syndrome, accompanied by epilepsy, developmental delay, and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Whole-exome sequencing revealed a heterozygous truncating variant in the GLI2 gene: NM_001374353.1(GLI2): c.2137(exon13)G>T; p.(Glu713Ter,857). The GLI2 gene is classified as haploinsufficient in the ClinGen database. This stop-gain variant was absent from major population reference databases, including the 1000 Genomes Project and gnomAD, indicating that it is extremely rare.

Using the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria (7), this variant meets the classification of likely pathogenic (LP), supported by: PVS1 (strong evidence; a nonsense mutation in a gene where loss of function is an established disease mechanism) and PM2 (supporting evidence; extremely low population frequency). Furthermore, the variant has not been reported in gnomAD, HGMD (Human Gene Mutation Database), or ClinVar.

At the molecular level, the substitution of thymine (T) for guanine (G) at nucleotide position 2,137 converts the codon for glutamic acid (Glu) at position 713 into a premature termination codon (Ter). This change introduces an early stop, leading to the truncation of the protein by 857 amino acids before its normal endpoint. The resultant truncated product would terminate polypeptide synthesis prematurely and disrupt normal GLI2 protein function. Segregation analysis confirmed that the variant was maternally inherited and absent in the father.

4 Discussion

The GLI2 gene belongs to the gli-kruppel family of transcription factors and was first identified through its amplification in human gliomas (8). Located on chromosome 2q14, GLI2 comprises 14 exons and encodes a protein of 1,586 amino acids (1). The GLI2 protein contains a zinc-finger DNA-binding domain and functions as a transcription factor, demonstrating repressive activity at its N-terminus and activating activity at its C-terminus. Depending on species-specific and cellular contexts, GLI2 can promote or inhibit transcription and, together with GLI1, GLI3, and Shh, regulates downstream gene expression within the Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway. The Hh pathway plays a critical role in the development of the central nervous system, distal limb formation, and the pathogenesis of various tumors (9).

Despite its biological significance, GLI2 is a large and highly polymorphic gene. Functionally impactful variants have been reported in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, reflecting the incomplete penetrance of the condition (8). The considerable phenotypic variability among GLI2 mutation carriers is likely influenced by genetic background, epigenetic regulation, and modifier genes within the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway, including SHH, ZIC2, SIX3, PTCH1, GLI3, and TGIF (10–13). Clinical manifestations associated with GLI2 mutations range widely, from individuals with no apparent abnormalities to those presenting with polydactyly, craniofacial dysmorphisms, pituitary defects, Culler-Jones syndrome, and holoprosencephaly type 9 (HPE9; OMIM: 610829) (2, 14). The overall prevalence of GLI2-related disorders is estimated to be fewer than 1 per 1,000,000 individuals (6).

CJS is most commonly associated with pituitary hormone deficiencies, ectopic posterior pituitary, and postaxial polydactyly. However, other manifestations such as growth retardation, seizures, hypoglycemia, and midline structural abnormalities have also been reported (15). Database searches indicated that the variant identified in this patient represents a previously unreported GLI2 mutation (1–4, 10–12, 14–23). This truncating mutation involves a guanine-to-thymine substitution at nucleotide position 2,137 in exon 13 of the GLI2 coding region. This single-nucleotide change converts the codon for glutamic acid (Glu) at position 713 into a premature stop codon (Ter), generating a truncated protein lacking the final 857 amino acids of the normal sequence.

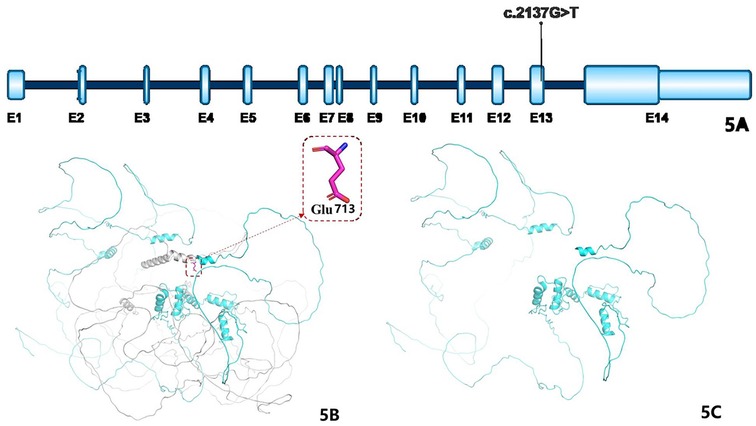

Figure 5A illustrates the GLI2 gene structure, based on mRNA transcript NM_001374353.1, which contains 14 exons; the mutation identified in this case is significant. A schematic representation of the GLI2 protein's three-dimensional structure is shown in Figures 5B,C, where the gray region in Figure 5B denotes amino acids beyond position 713 in the wild-type protein, and Figure 5C shows the truncated mutant form.

Figure 5. (A) Shows the structural diagram of the GLI2 gene: the blue parts represent exons (abbreviated as E), and the teal parts represent introns; the mRNA variant number is NM_001374353.1, which consists of 14 exons, and the marked variant sites are the cases in this study. (B) Shows the schematic diagram of the three-dimensional structure of the wild-type GLI2 protein (the gray part represents the amino acids after the 713th amino acid); (C) shows the schematic diagram of the three-dimensional structure of the mutant GLI2 protein.

In a review of 112 individuals from 65 families carrying GLI2 variants, only 37% of those with truncating mutations showed both pituitary abnormalities and polydactyly, whereas non-truncating variants were associated with isolated pituitary phenotypes in 92% of cases, reflecting incomplete penetrance (10, 16–18). To date, the ClinVar database lists 47 pathogenic and 18 likely pathogenic GLI2 variants, with truncating mutations (frameshift and nonsense variants) comprising 53.8%. Such truncating alterations typically exert substantial effects on protein structure and function, severely compromising transcriptional regulatory activity and contributing to the development of CJS (10).

The clinical features observed in this case differed from previously reported presentations, which may be explained by the incomplete penetrance and substantial phenotypic heterogeneity associated with GLI2 mutations, as well as the potential influence of specific mutation sites. Consistent with recognized features of the disorder, the child demonstrated postaxial polydactyly, growth retardation, and recurrent epileptic seizures. Whole-exome sequencing confirmed a heterozygous variant, c.2137(exon13)G>T/p.(E713,857) (NM_001374353), establishing a definitive diagnosis of CJS. To our knowledge, this particular variant has not been previously documented.

Previous studies have shown that CJS displays wide phenotypic variability both among unrelated individuals and within affected families, and no clear genotype–phenotype correlation has been identified (24). In this family, the child's mother also presented with bilateral hexadactyly and short stature, and sequencing confirmed that she carried the same heterozygous GLI2 variant. Several other maternal relatives reportedly had polydactyly, further highlighting intrafamilial variability. The family history also included other adverse outcomes: the proband's older brother died at six months of age from congenital heart disease and pneumonia (with incomplete clinical data), and the maternal aunt experienced two unexplained miscarriages. These findings illustrate the broad clinical spectrum associated with GLI2 mutations. Comprehensive segregation analysis across the maternal lineage, however, could not be completed due to practical constraints.

Existing research has not demonstrated a consistent correlation between specific GLI2 variants and clinical severity, and considerable overlap exists in the phenotypic profiles of individuals carrying different mutations. Previous studies have also shown no association between the position or length of truncating variants and resulting phenotypes (10–12, 19, 21). One possible explanation is that the transcriptional activation domain of GLI2 is located at the distal end of the protein; thus, truncating mutations typically eliminate this domain, leading to loss of activation function and resulting in similar functional consequences across most truncating variants. Furthermore, patients with microdeletions involving GLI2 are more likely to present with additional congenital anomalies, including cardiac defects, visceral heterotaxy, and genitourinary malformations (5, 12).

Mutations in GLI2 have been implicated in both Culler-Jones syndrome (CJS) and holoprosencephaly type 9 (HPE9). HPE9 encompasses a broad range of developmental brain abnormalities, which may occur with or without defects in forebrain cleavage. Because CJS and HPE9 share overlapping causative genes and clinical features, distinguishing between them is an important diagnostic challenge (10). HPE9 is considered part of the broader phenotypic spectrum of GLI2-related disorders and, like CJS, demonstrates incomplete penetrance and significant phenotypic variability. Increasing evidence suggests that CJS and HPE9 represent the milder and more severe ends of a continuous spectrum, respectively (5).

Most truncating GLI2 variants reported to date are associated with polydactyly (8). In a large cohort study of 400 individuals with holoprosencephaly, Bear et al. identified 112 carriers of GLI2 variants, including 43 with truncating mutations. Patients with truncating variants were significantly more likely to show the combination of pituitary abnormalities and postaxial polydactyly than those harboring variants of uncertain significance, suggesting that truncating GLI2 mutations generally manifest as hypopituitarism, polydactyly, and subtle craniofacial features rather than classic holoprosencephaly. The presence of polydactyly in a patient with hypopituitarism or in family members should therefore prompt consideration of a GLI2 mutation. Isolated holoprosencephaly caused by pathogenic GLI2 variants appears to be extremely rare (10).

Beyond pituitary and limb defects, GLI2-related disorders have been linked to a range of systemic abnormalities, including renal anomalies (such as agenesis or dysplasia), urethral stenosis, congenital heart defects (e.g., atrial or ventricular septal defects), and neuroanatomical abnormalities including agenesis of the corpus callosum, periventricular venous system anomalies, and cortical gyration defects (2, 14, 25). According to existing literature, GLI2 mutations commonly result in hypoglycemia, hypopituitarism, and abnormalities in neurological development (26, 27). Despite these established associations, functional characterization of the specific variant identified in this case remains lacking, as no animal model–based studies are available. More extensive basic research is needed to clarify the pathogenic mechanisms underlying this mutation's association with CJS.

In conclusion, this case reports a previously unrecognized truncating GLI2 mutation in a neonate who presented with hallmark features of Culler-Jones syndrome. Given the substantial clinical variability and the absence of a clear genotype–phenotype correlation, CJS should be considered in infants who present with postaxial polydactyly, growth delay, refractory seizures, and a suggestive family history. Early genetic evaluation is strongly recommended to facilitate timely and accurate diagnosis.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Second Hospital of Lanzhou University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

XX: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis. YW: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. YL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JuW: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. YZ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JiW: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis. FW: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Validation, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Wu Jieping Medical Foundation Special Funding Fund for Scientific Research (320.6750.2023-24-3), China; the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (23JRRA0977).

Acknowledgments

We thank the family members of the patients for providing samples. We also thank Mjeditor for scientific editing of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2025.1699082/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Demiral M, Demirbilek H, Unal E, Durmaz CD, Ceylaner S, Ozbek MN. Ectopic posterior pituitary, polydactyly, midfacial hypoplasia and multiple pituitary hormone deficiency due to a novel heterozygous IVS11-2A>C(c.1957-2A>C) mutation in the GLI2 gene. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. (2020) 12(3):319–28. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2019.2019.0142

2. Shirakawa T, Nakashima Y, Watanabe S, Harada S, Kinoshita M, Kihara T, et al. A novel heterozygous GLI2 mutation in a patient with congenital urethral stricture and renal hypoplasia/dysplasia leading to end-stage renal failure. CEN Case Rep. (2018) 7(1):94–7. doi: 10.1007/s13730-018-0302-9

3. França MM, Jorge AAL, Carvalho LRS, Costalonga EF, Vasques GA, Leite CC, et al. Novel heterozygous nonsense GLI2 mutations in patients with hypopituitarism and ectopic posterior pituitary lobe without holoprosencephaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2010) 95(11):E384–91. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1050

4. Elward C, Berg J, Oberlin JM, Rohena L. A case series of a mother and two daughters with a GLI2 gene deletion demonstrating variable xpressivity and incomplete penetrance. Clin Case Rep. (2020) 8(11):2138–44. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3085

5. Niida Y, Inoue M, Ozaki M, Takase E. Human malformation syndromes of defective GLI: opposite phenotypes of 2q14.2 (GLI2) and p14.2 (GLI3) microdeletions and a GLIA/R balance model. Cytogenet Genome Res. (2017) 153(2):56–65. doi: 10.1159/000485227

6. Martín-Rivada Á, Rodríguez-Contreras FJ, Muñoz-Calvo MT, Güemes M, González-Casado I, Del Pozo JS, et al. A novel GLI2 mutation responsible for congenital ypopituitarism and polymalformation syndrome. Growth Horm IGF Res. (2019) 44:17–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2018.12.002

7. Riggs ER, Andersen EF, Cherry AM, Kantarci S, Kearney H, Patel A, et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics (acmg) and the clinical genome resource (clingen). Genet med. (2021) 23(11):2230. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01150-9

8. Arnhold IJ, França MM, Carvalho LR, Mendonca BB, Jorge AA. Role of GLI2 in hypopituitarism phenotype. J Mol Endocrinol. (2015) 54:R141–50. doi: 10.1530/JME-15-0009

9. Briscoe J, Therond PP. The mechanisms of hedgehog signalling and its roles in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2013) 14(7):416–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm3598

10. Bear KA, Solomon BD, Antonini S, Arnhold IJ, França MM, Gerkes EH, et al. Pathogenic mutations in GLI2 cause a specific phenotype that is distinct from holoprosencephaly. J Med Genet. (2014) 51:413–8. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102249

11. Kremer Hovinga ICL, Giltay JC, van der Crabben SN, Steyls A, vander Kamp HJ, Paulussen ADC. Extreme phenotypic variability of a novel GLI2 mutation in a large family with panhypopituitarism and polydactyly: clinical implications. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). (2018) 89:378–80. doi: 10.1111/cen.13760

12. Kevelam SHG, van Harssel JJ, van der Zwaag B, Smeets HJM, Paulussen ADC, Lichtenbelt KD. A patient with a mild holoprosencephaly spectrum phenotype and heterotaxy and a 1.3 mb deletion encompassing GLI2. Am J Med Genet A. (2012) 158:166–73. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34350

13. Valenza F, Cittaro D, Stupka E, Biancolini D, Patricelli MG, Bonanomi D, et al. A novel truncating variant of GLI2 associated with culler-jones syndrome impairs hedgehog signalling. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0210097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210097

14. Kordaß U, Schröder C, Elbracht M, Soellner L, Eggermann T. A familial GLI2 deletion (2q14.2) not associated with the holoprosencephaly syndrome phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. (2015) 167:1121–4. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36972

15. Goel H, Harrison K. De novo GLI2 missense variant in a child with isolated hypopituitarism and craniofacial anomalies: expanding the phenotypic spectrum. Mol Genet Genomic. (2025) 13(9):e70136. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.70136

16. Fan YS, Ding SX, Wu JH, Qiu HY. Clinical and genetic analysis of a child with culler-jones syndrome due to variant of GLI2 gene. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. (2023) 40(2):217–21. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn511374-20210927-00779

17. Wang XW, Xu LL, Lyu WS, Sun XF, Wang YG, Xue Y. Culler-Jones syndrome caused by a new mutated GLI2 gene: a case report. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. (2023) 62(12):1472–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112138-20230322-00167

18. Zhang Y, Dong B, Xue Y, Wang Y, Yan J, Xu L. Case report: a case of culler-jones syndrome caused by a novel mutation of GLI2 gene and literature review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1133492. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1133492

19. Corder ML, Berland S, Førsvoll JA, Banerjee I, Murray P, Bratland E, et al. Truncating and zinc-finger variants in GLI2 are associated with hypopituitarism. Am J Med Genet A. (2022) 188(4):1065–74. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.62611

20. Castro-Feijoo L, Cabanas P, Barreiro J, Silva P, Couce ML, Pombo M, et al. Identification of three novel GLI2 gene variants associated with hypopituitarism. 57th Annual ESPE (ESPE 2018); 2018 Sep 27–29; Athens, Greece (2018). p. 89

21. Babu D, Fanelli A, Mellone S, Muniswamy R, Wasniewska M, Prodam F, et al. Novel GLI2 mutations identified in patients with Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency (CPHD): evidence for a pathogenic effect by functional characterization. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). (2019) 90(3):449–56. doi: 10.1111/cen.13914

22. Wada K, Kobayashi H, Moriyama A, Haneda Y, Mushimoto Y, Hasegawa Y, et al. A case of an infant with congenital combined pituitary hormone deficiency and normalized liver histology of infantile cholestasis after hormone replacement therapy. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. (2017) 26(4):251–7. doi: 10.1297/cpe.26.251

23. Yuan X, Chu S, Gu W. A case report of culler-jones syndrome with deafness carrying a novel mutation in GLI2 gene. BMC Pediatr. (2025) 25(1):878. doi: 10.1186/s12887-025-06135-0

24. Bertolacini CPD, Ribeiro-Bicudo LA, Petrin A, Richieri-Costa A, Murray JC. Clinical findings in patients with GLI2 mutations-phenotypic variability. Clin Genet. (2012) 81:70–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01606.x

25. Peng HH, Wang CJ, Wang TH, Chang SD. Prenatal diagnosis of de novo interstitial 2q14.2-2q21.3 deletion assisted by array-based comparative genomic hybridization: a case report. J Reprod Med. (2006) 51:438–42.16779995

26. Zhang Y, Dong B, Xue Y, Wang Y, Yan J, Xu L. Case report: a case of culler-jones syndrome caused by a novel mutation of GLI2 gene and literature review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1133492. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1133492

Keywords: Culler-Jones syndrome, developmental delay, epilepsy, GLI2, polydactyly, whole exome sequencing

Citation: Xie X, Wei Y, Li Y, Wang J, Zhang Y, Wu J and Wang F (2025) Case Report: A case of Culler-Jones syndrome caused by GLI2 gene mutation. Front. Pediatr. 13:1699082. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1699082

Received: 4 September 2025; Revised: 7 December 2025;

Accepted: 8 December 2025;

Published: 19 December 2025.

Edited by:

Bushra Khan, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, PakistanReviewed by:

Anshika Mishra, Naraina Medical College & Research Centre, IndiaSaira Farman, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Pakistan

Noor Shad Bibi, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Pakistan

Copyright: © 2025 Xie, Wei, Li, Wang, Zhang, Wu and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fan Wang, d2FuZ2ZhbjEwMThAc2luYS5jb20=

Xiaomei Xie

Xiaomei Xie Youfen Wei

Youfen Wei Ye Li

Ye Li Fan Wang

Fan Wang