- 1Department of Urology, Kunming Children’s Hospital (Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Kunming Medical University), Kunming, China

- 2Urology Department, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China

- 3Yunnan Province Clinical Research Center for Children’s Health and Disease, Yunnan Key Laboratory of Children’s Major Disease Research, Kunming, China

- 4Department of Dermatology, Kunming Children’s Hospital (Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Kunming Medical University), Kunming, China

Background: Pediatric penile hamartoma is extremely rare. Preoperative imaging often cannot definitively characterize the lesion, and histopathology remains the diagnostic gold standard. We report a child with penile hamartoma and torsion, discuss management, and compare outcomes with the literature.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed the clinical presentation, imaging, intraoperative findings, and pathology. Relevant reports were reviewed for comparison.

Results: Complete excision of a ventral hamartomatous appendage plus circumcision and release of a fibrous tethering band achieved immediate torsion correction in a single stage. Histopathology showed stratified squamous epithelium with proliferative fibrous and adipose tissue containing nerve bundles, ganglion cells, and focal smooth muscle—consistent with hamartoma. Recovery was uneventful; at 12 months no recurrence was observed.

Conclusion: Etiology-targeted, one-stage correction—degloving (circumcision), release of tethering bands, complete lesion excision, and simultaneous torsion repair—can be safe and effective. Long-term follow-up is advised.

Introduction

A hamartoma is a tumor-like malformation formed by disorganized overgrowth of tissue native to the involved site during development. Penile hamartomas are exceedingly rare in children and may mimic other tumors or genital anomalies (1–3). Imaging delineates extent and relationships, whereas histopathology confirms diagnosis. We describe a pediatric penile hamartoma with significant torsion and highlight an etiology-targeted, one-stage strategy.

Case report

Presentation and examination

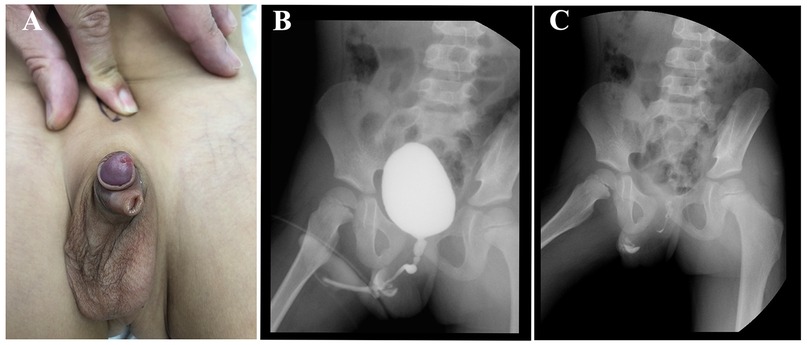

A 4-year-3-month-old boy was brought to our clinic with an abnormal penile appearance noted since early infancy (approximately 4 years in duration). The child's overall growth and development were normal. On genital examination, the penis appeared to have an excessive foreskin and was rotated about 90° counterclockwise, such that the urethral meatus was displaced laterally. An 2 cm skin-covered appendage was evident on the ventral side of the penile shaft; it was soft, lacked any palpable corpus cavernosum-like structure, and was covered with skin resembling the prepuce. Both testes were palpated within the scrotum with normal consistency, and the scrotal appearance was unremarkable (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Preoperative clinical and imaging evaluation. (A) Clinical photograph showing a ventral, skin-covered appendage and approximately 90° counterclockwise penile torsion with an eccentric meatus. (B) Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), filling/early voiding phase: normal bladder contour with opacification and a single urethral channel; no duplicated tract is seen. (C) VCUG, post-void/late-phase plain film: no secondary urethral tract or fistulous communication is demonstrated.

Investigations

The mother's prenatal exams had been normal. The patient had no history of surgery, trauma, or a family history of tumors. Laboratory tests, including serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), were all within normal ranges. Routine preoperative evaluations (chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, and cardiac ultrasound) showed no abnormalities. An excretory urography study (intravenous urogram) revealed no obvious abnormality of the bladder; both ureters were not visualized, and after removing the catheter, the patient voided normally with no evidence of a duplicated urethra on the study (Figures 1B,C). Based on the clinical and imaging findings, the provisional diagnosis was “penile torsion with penile anomaly of unclear nature (to be determined)”. No contraindications for surgery were present, so elective surgical treatment was planned.

Surgery and intraoperative findings

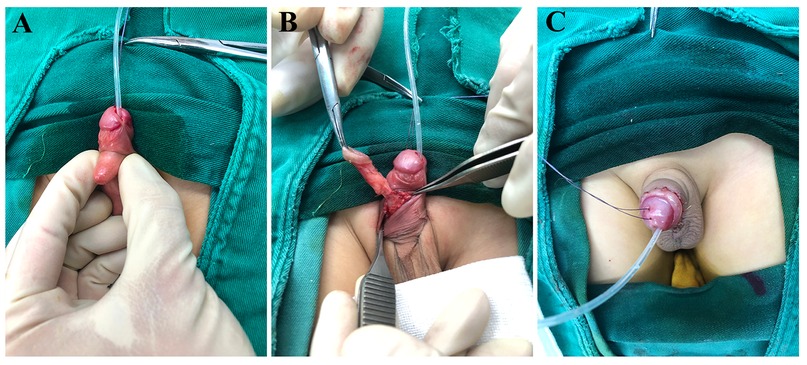

Under general anesthesia, a circumferential incision was made at the tip of the ventral appendage and dissection was carried proximally. The ventral penile appendage was found to consist of a cord-like fibrous tissue that was attached to the tunica of the corpus spongiosum; it was well demarcated from surrounding structures. The cord-like band was the apparent source of traction causing the penile torsion. The fibrous band and attached appendage were completely excised en bloc and sent for pathological examination (Figures 2A,B). Next, a circumferential degloving incision (circumcision) was made approximately 0.5 cm below the coronal sulcus, and the abnormally tethered fibrous bands in the subcutaneous tissue were carefully released. Once these traction bands were freed, the penis could be rotated back to its normal alignment and straightened without tension, and the urethra was confirmed to be intact and of normal length. A urethral catheter was left in place postoperatively and removed on postoperative day 3, after which the child voided without difficulty (Figure 2C). The surgical correction was completed in a single stage with an excellent immediate result.

Figure 2. Intraoperative course and one-stage correction. (A) After degloving (circumcision), persistent axial torsion is evident with the catheter in situ and a ventral appendage. (B) Dissection identifies a cord-like fibrous tether between the appendage and the ventral shaft/corpus spongiosum; the traction band is released and excised en bloc. (C) Final appearance after complete excision and torsion repair, showing restored alignment and a well-healed circumferential suture line.

Pathology and follow-up

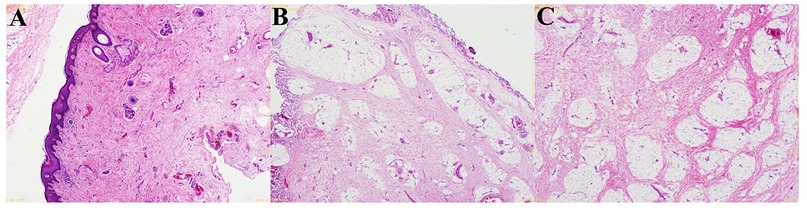

Gross examination of the excised tissue confirmed a fibrous cord tethering the ventral appendage to the penile shaft. Histopathological analysis showed that the lesion was covered by stratified squamous epithelium. Beneath the epithelium, there was an overgrowth of fibrous and adipose tissue, within which nerve bundles, ganglion cells, and blood vessels were observed; focal small bundles of smooth muscle were also present (Figures 3A–C). These features were consistent with a hamartoma of the penis. The postoperative diagnosis was finalized as “penile torsion secondary to penile hamartoma.” The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged on postoperative day 3. At the 1-year follow-up visit, no recurrence or complications had occurred. The penis appeared normal in shape, and urinary function (voiding stream and continence) was excellent.

Figure 3. Histopathology of the penile hamartoma (hematoxylin–eosin, HE). (A) Low-power view (original magnification ×40) showing a surface of stratified squamous epithelium with an underlying disorganized overgrowth of fibrous and adipose tissue. (B) Intermediate-power view (original magnification ×100) highlighting scattered nerve bundles (NB) and ganglion cells (GC) within the lesion, together with small blood vessels. (C) High-power view (original magnification ×200) demonstrating focal bundles of smooth muscle (SM) embedded in the fibrous stroma, a composition consistent with a hamartomatous lesion of the penis.

Discussion

Penile hamartomas in pediatric patients are exceptionally rare. Clinically, they usually present as an abnormal penile appearance or a localized penile mass noticed by caregivers. While imaging studies can aid in assessing the extent of the lesion and its relationship to adjacent structures, the definitive diagnosis depends on pathological examination of the excised tissue (4, 5). In our case, the pathology demonstrated the characteristic disorganized proliferation of tissues native to the penis (fibrous, adipose, nerve, vascular, and smooth muscle elements) beneath a squamous epithelial surface, and the intraoperative findings confirmed a fibrous cord-like connection between the hamartomatous appendage and the corpus spongiosum.

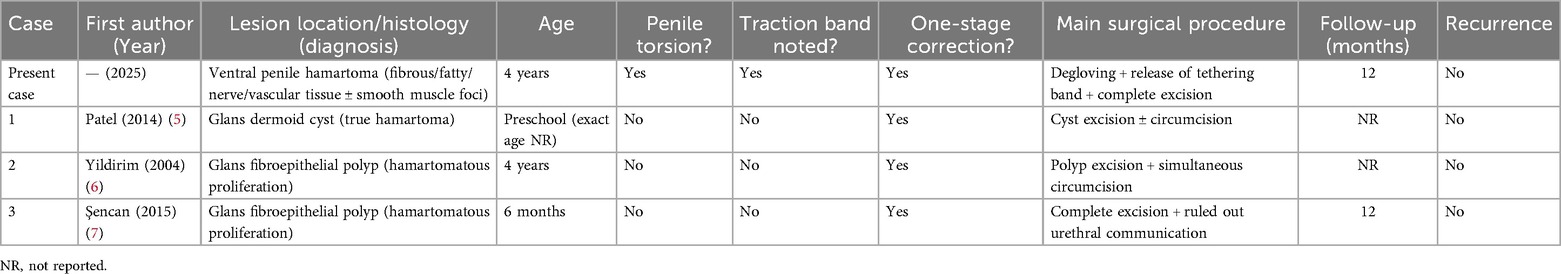

We conducted a literature search of PubMed, PMC and major journal databases up to September 18, 2025. Keywords used included combinations of terms such as “penile hamartoma”, “hamartomatous lesion”, “dermoid cyst or epidermoid cyst of the penis/scrotum”, and “fibroepithelial polyp” coupled with “child”, “infant”, or “pediatric”. Relevant articles’ references were also reviewed (snowball method). Our review focused on true hamartomas and hamartomatous lesions occurring in the penile proper (glans, shaft, base, or prepuce/penile skin) in patients under 18 years of age. This search yielded only three prior reported cases that fit these criteria (6–8), which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of the present case with previously reported pediatric penile hamartomatous lesions.

Compared to the previously reported cases, our case has several unique features and clinical implications. First, an etiological clue for the torsion was clearly identified. In prior reports, penile or peri-urethral hamartomas were generally described as “incidental masses”, and a direct cause-and-effect relationship between a tethering band and penile torsion was not well established (6). In our case, a distinct cord-like hamartomatous tissue was found to be the source of a significant 90° penile torsion. Releasing this tether and excising the lesion led to immediate torsional correction, suggesting that an etiology-targeted surgical approach (i.e., removing the traction source) is superior to simple excision of the mass alone when torsion is present. Second, our management strategy was more integrated. Most previously reported cases were managed with either staged procedures or treatment of only the localized lesion (7). In contrast, our case was managed in a one-stage operation that combined complete lesion excision, foreskin degloving/circumcision, and torsion repair concurrently. This one-stop approach achieved an optimal cosmetic and functional outcome, and no recurrence was observed at one year postoperatively. Third, our diagnostic workup provides a more replicable pathway for differentiation from other conditions. Preoperatively, we performed an excretory urography study to exclude urethral duplication (no double urethra was visualized), and we assessed whether any corpus cavernosum/urethra-like structures were present in the appendage as well as the anatomical axis deviation (2, 4, 8). These steps helped avoid misdiagnosis with conditions such as fibrous hamartoma of infancy (a benign fibrous tumor in infants, FHI), fibrolipoma, teratoma or dermoid cyst, vascular malformations, or pseudodiphallia (accessory pseudo-penis). This systematic approach reduced the risk of misidentifying the lesion, ensuring appropriate management.

In terms of surgical correction techniques for torsion, mild to moderate isolated penile torsion can often be corrected by simply degloving (circumferential skin mobilization) and realigning the skin to the proper position. However, in more severe torsion cases (>90°) or those with deeper fascial abnormalities or a tethering band, some authors have recommended additional maneuvers such as dorsal tunica albuginea plication or rotational skin/dartos flaps to prevent residual torsion (9). In our case, by precisely identifying and removing the fibrous traction band, we achieved full correction of a ∼90° torsion without the need for any dorsal plication or flap, illustrating that in a “traction-induced torsion” scenario, a simplified surgery addressing the root cause can be effective. For postoperative evaluation, we advocate documenting objective cosmetic outcomes, parental satisfaction, and voiding function parameters, which would allow comparison of results across cases and provide evidence for long-term success (10, 11).

Additionally, this case highlights the importance of a systematic risk assessment for underlying syndromes or multiple lesions. If a patient presents with multiple hamartomas, mucocutaneous abnormalities, or other features such as macrocephaly, one should consider the possibility of PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) and pursue appropriate genetic counseling and surveillance (12–14). In cases where imaging suggests deep tissue involvement or proximity to the urethra, a preoperative urethrogram or magnetic resonance urography (MRU) can be helpful to plan resection margins and reconstructive strategy. Careful preoperative planning in such complex cases can help prevent intraoperative surprises and guide safe excision while preserving function (1).

Conclusion

In conclusion, pediatric penile hamartomas are extraordinarily rare. Preoperative imaging can be valuable for delineating the lesion's extent and its relationships with surrounding structures, but a definitive diagnosis relies on histopathology. Our case demonstrates that an etiology-targeted, one-stage surgical approach — consisting of complete lesion excision, foreskin degloving (circumcision) with exposure, release of any tethering fibrous bands, and simultaneous correction of penile torsion — can achieve a safe and effective outcome. In this patient, the strategy resulted in excellent cosmetic and functional results with no recurrence during follow-up. Children presenting with multiple hamartomatous lesions or other concerning clinical features should undergo genetic evaluation (for conditions such as PHTS) and warrant long-term surveillance. Moving forward, accumulation of more cases through multi-center collaboration, along with standardized surgical techniques and quantitative outcome measures, is needed to establish stronger evidence and guidance for managing this rare condition.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by this study was approved by the ethical committee of Kunming Children's Hospital (2025-05-100-K01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ZY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NZ: Methodology, Writing – original draft. JL: Data curation, Writing – original draft. ZH: Data curation, Writing – original draft. BY: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Yunnan Education Department of Science Research Fund (No. 2023 J0295, 2024J0300), Science and Technology project of Kunming Municipal Commission of Health and Construction (No. 2024-SW(L)-07, 2024-SW(L)-21), Kunming Medical Joint Project of Yunnan Science and Technology Department (No. 202001AY070001-271, 202301AY070001-108), Research Project of Yunnan Provincial Clinical Medical Center (No. 2024YNLCYXZX0430, 2024YNLCYXZX0428, 2024YNLCYXZX0462), Health Research Project of Kunming Municipal Health Commission (No. 2023-02-05-005, 2025-04-05-015), Kunming Science and Technology Plan (2023-1-NS-015), Scientific Research Project of Yunnan Clinical Medical Center and Open Research Fund of Clinical Research Center for Children's Health and Diseases of Yunnan Province. The funding bodies played no role in the study's design and collection, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Hao Z, Zhanghuang C, Zhang K, Zhang L, Li X, Wang Y, et al. Posterior urethral hamartoma with hypospadias in a child: a case report and literature review. Front Pediatr. (2023) 11:1195900. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1195900

2. Zhanghuang C, Hang Y, Ji F, Wang J, Li Q, Liu Y, et al. Congenital giant fibroepithelial polyp of the scrotum in an infant: the first case report from China. Front Pediatr. (2023) 11:1191983. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1191983

3. Starr S, Muram-Zborovski T, Minko N, Gokhale R, Dasgupta R, Ramakrishna H, et al. Scrotal fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a case report and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. (2022) 17(10):3714–20. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2022.07.061

4. Yan H, Treacy A, Yousef G, Stewart R. Giant fibroepithelial polyp of the glans penis not associated with condom-catheter use: a case report and literature review. Can Urol Assoc J. (2013) 7(9-10):E621–4. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.506

5. Patel RV, Govani D, Qazi A, Haider N. Dermoid cyst of the glans penis in a toddler. BMJ Case Rep. (2014) 2014:bcr2014204585. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204585

6. Yildirim I, Basal S, Irkilata HC, Kose O, Keles M, Atilla MK. Fibroepithelial polyp of the glans penis in a child. Int J Urol. (2004) 11(3):187–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2003.00757.x

7. Şencan A, Şencan A, Günşar C, Çayırlı H, Neşe N. A rare cause of glans penis masses in childhood: fibroepithelial polyp. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. (2015) 20(1):42–4. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.145550

8. Bar-Yosef Y, Binyamini J, Matzkin H, Ben-Chaim J. Degloving and realignment—simple repair of isolated penile torsion. J Pediatr Surg. (2007) 42(2):e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.10.048

9. Bauer R, Kogan BA. Modern technique for penile torsion repair. J Urol. (2009) 182(1):286–90; discussion 290-1. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.133

10. Aykaç A, Balci O, Karaman MI, Demirci H, Sahin S, Ozbey I. Penile degloving and dorsal dartos flap rotation approach for the management of isolated penile torsion. Urol Ann. (2016) 8(1):84–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.164850

11. Zhang W, Yu N, Liu Z, Wang X. Pseudodiphallia: a rare kind of diphallia: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). (2020) 99(33):e21638. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021638

12. Schultz KAP, MacFarland SP, Perrino MR, Mitchell SG, Kamihara J, Nelson AT, et al. Update on pediatric surveillance recommendations for PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome, DICER1-related tumor predisposition, and tuberous sclerosis complex. Clin Cancer Res. (2025) 31(2):234–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-24-1947

13. Tischkowitz M, Colas C, Pouwels S, Hoogerbrugge N; PHTS guideline development group; European reference network GENTURIS. Cancer surveillance guideline for individuals with PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. (2020) 28(10):1387–93. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-0651-7

Keywords: penis, hamartoma, pediatric, penile torsion, surgery

Citation: Yao Z, Zhanghuang C, Zhou N, Li J, Hao Z, Yan B and Zhao H (2025) Case Report: Penile hamartoma with penile torsion in a child: etiology-targeted one-stage surgical correction and literature review. Front. Pediatr. 13:1715759. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1715759

Received: 29 September 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Pedro Lopez Pereira, University Hospital La Paz, SpainReviewed by:

Vladimir Kojovic, University of Belgrade, SerbiaSupul Hennayake, The University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Copyright: © 2025 Yao, Zhanghuang, Zhou, Li, Hao, Yan and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bing Yan, eWJ3Y3lAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Hui Zhao, emhhb2h1aWt5Znl5QDEyNi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Zhigang Yao1,2,†

Zhigang Yao1,2,† Chenghao Zhanghuang

Chenghao Zhanghuang Bing Yan

Bing Yan