Abstract

To improve long-term outcomes of therapies for chronic diseases, health promotion and lifestyle modifications are the most promising and sustainable strategies. In addition, advances in digital technologies provide new opportunities to address limitations of drug-based treatments, such as medication non-adherence, adverse effects, toxicity, drug resistance, drug shortages, affordability, and accessibility. Pharmaceutical drugs and biologics can be combined with digital health technologies, including mobile medical apps (digital therapeutics), which offer additional clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness. Promises of drug+digital combination therapies are recognized by pharmaceutical and digital health companies, opening opportunities for integrating pharmacotherapies with non-pharmacological interventions (metapharmacology). Herein we present unique features of digital health technologies which can deliver personalized self-care modalities such as breathing exercises, mindfulness meditation, yoga, physical activity, adequate sleep, listening to preferred music, forgiveness and gratitude. Clinical studies reveal how aforementioned complimentary practices may support treatments of epilepsy, chronic pain, depression, cancer, and other chronic diseases. This article also describes how digital therapies delivering “medicinal” self-care and other non-pharmacological interventions can also be personalized by accounting for: 1) genetic risks for comorbidities, 2) adverse childhood experiences, 3) increased risks for viral infections such as seasonal influenza, or COVID-19, and 4) just-in-time stressful and traumatic circumstances. Development and implementation of personalized pharmacological-behavioral combination therapies (precision metapharmacology) require aligning priorities of key stakeholders including patients, research communities, healthcare industry, regulatory and funding agencies. In conclusion, digital technologies enable integration of pharmacotherapies with self-care, lifestyle interventions and patient empowerment, while concurrently advancing patient-centered care, integrative medicine and digital health ecosystems.

Digital Health Technologies and Pharmacotherapies

Despite a significant progress in developing new therapies, there is a growing number of people in the world living with chronic diseases (Disease, 2018). At the same time, emergence of digital health technologies has coincided with growing number of studies illustrating limitations of pharmaceutical drugs and biologics for treating chronic medical conditions (Monnat, 2018; Sverdlov et al., 2018). Challenges of pharmacotherapies for chronic diseases include: 1) medication non-adherence which affects 30–50% of people living with chronic medical conditions (Brown and Bussell, 2011), 2) treatment-resistant populations of people living with epilepsy, chronic pain, depression, and cancer (Kwan et al., 2011; Borsook et al., 2018; Pandarakalam, 2018; Assaraf et al., 2019), 3) adverse effects, tolerability, toxicity, mortality (Monnat, 2018), and 4) affordability, accessibility, and shortages of medications (Kesselheim et al., 2016). All aforementioned problems contribute to decreasing therapy outcomes while increasing healthcare costs.

Digital health technologies (also known as mobile health, or mHealth) use software to deliver diverse clinical functionalities including non-pharmacological interventions for chronic diseases (Rowland et al., 2020). Digital therapeutics are mobile medical apps which intend to treat specific medical conditions and have received regulatory clearance or approval (software as medical device, SaMD) (Patel and Butte, 2020; Shuren et al., 2018; Sverdlov et al., 2018). An increasing number of studies show clinical benefits of mobile and web-based apps, or therapeutic video games, in people with diabetes, substance use, depression, anxiety, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, chronic pain, epilepsy, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer (Sverdlov et al., 2018; Chung, 2019; Sin et al., 2020). Clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness of digital interventions favor their implementation into health care (Jiang et al., 2019; Nordyke et al., 2019; Dang et al., 2020; Richards et al., 2020).

Digital therapeutics are currently prescribed by health care providers. Marketed digital therapeutics are approved or cleared as SaMD (510k or de novo pathways) by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Based on results from pivotal clinical studies (Patel and Butte, 2020). The FDA established the Software Precertification program allowing selected software companies to market lower-risk mobile apps without a regulatory review, or for higher-risk mobile medical apps after abbreviated review process (Alon et al., 2020). In addition, the FDA established Digital Health Center of Excellence, thus further emphasizing growing commitments of regulatory agencies, industry and R&D communities to support advancements in digital health technologies.

Sverdlov and colleagues described a rationale for developing combinations of digital therapeutics and pharmaceutical drugs (Sverdlov et al., 2018). Such drug+digital combinations would exhibit improved efficacy as compared to drug-alone or software-alone interventions. For example, developing drug-device combination products containing digital therapeutics offers promise for people with intractable epilepsy (Afra et al., 2018; Bulaj, 2014). The adjunct digital therapy, reSET®, has been approved in combination with buprenorphine for opioid use disorder (Patel and Butte, 2020). Mobile apps and serious video games can improve medication adherence further supporting benefits of integrating digital technologies with pharmacotherapies (Pouls et al., 2021). Pharmaceutical and biotech industries have recognized opportunities to innovate and improve treatments for chronic diseases, as illustrated by examples of collaborative partnerships between pharma and digital health companies [seeSupplementary Table S1 and the recent commentary (Patel and Butte, 2020)].

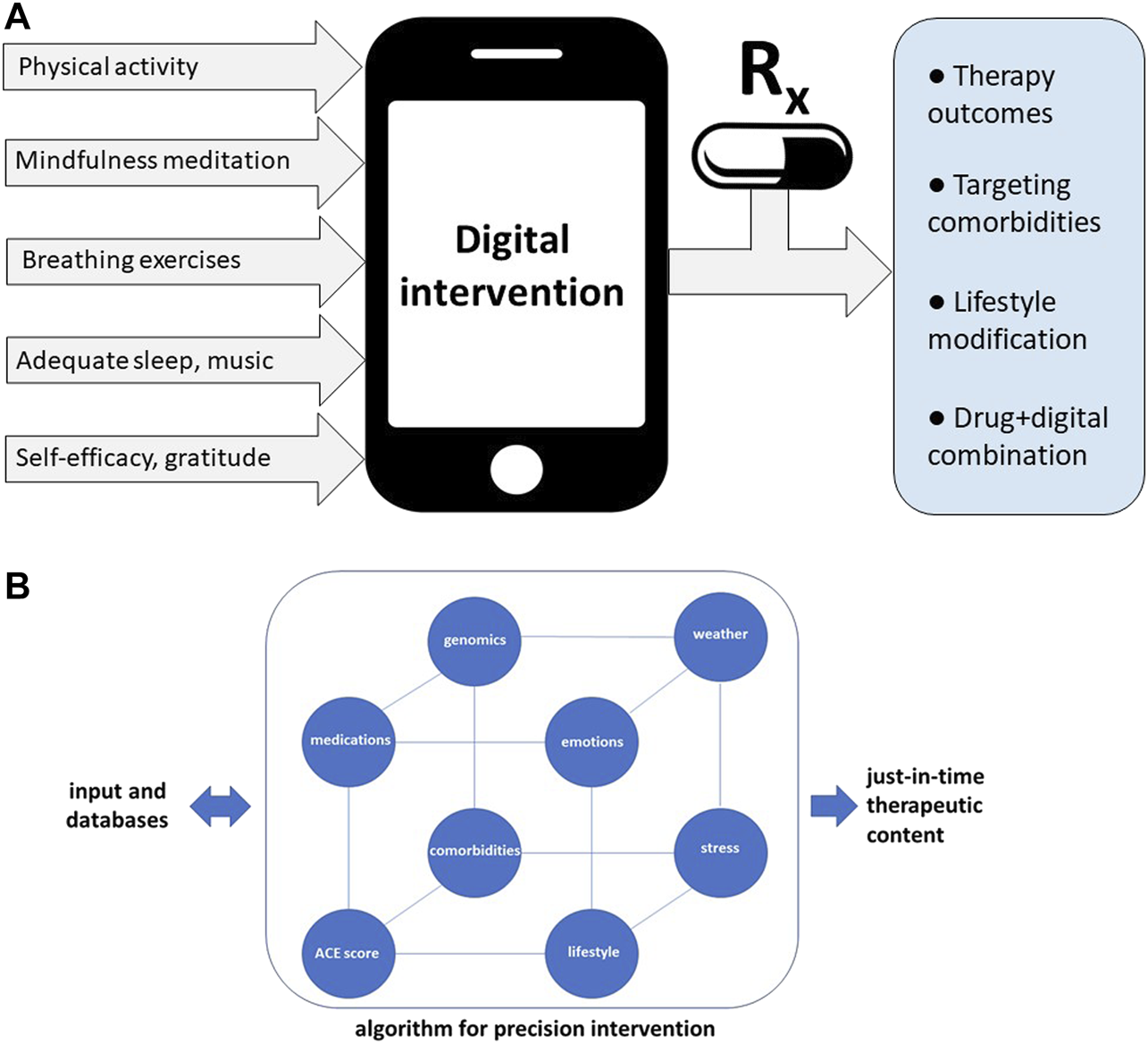

Precision metapharmacology can be defined as intervention comprising pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments, in which non-pharmacological components are tailored for individual patients (Figure 1). It is apparent that digital health technologies are empowered to deliver personalized non-pharmacological interventions, while drug+digital combination therapies can be developed using a regulatory pathway of drug-device combination products (in this case a mobile medical app is a medical device, or SaMD) (Afra et al., 2018; Bulaj, 2014). As discussed below, precision metapharmacology has an ability to deliver patient-centered care by integrating pharmacological treatments with behavioral interventions including personalized self-care practices.

FIGURE 1

Precision metapharmacology integrates pharmacotherapies with personalized, non-pharmacological interventions for chronic medical conditions including neurological, cardiovascular, metabolic, neurodegenerative, pulmonary, infectious diseases, mental disorders, and cancer. (A) Examples of diverse self-care practices delivered by digital health technologies aiming to improve therapy outcomes and lifestyle modifications. Such digital interventions can be offered via digital health ecosystems (Shegog et al., 2020), or combined with pharmacotherapies (drug+digital combination therapies) (Sverdlov et al., 2018). Integration of digital therapeutics (mobile medical apps) with prescription medications is enabled using the regulatory pathway for drug-device combination products (in this case medical device is a mobile medical app, “software as medical device”) (Bulaj, 2014). Expected outcomes of precision metapharmacology also include patient empowerment. (B) Examples of diverse factors included in algorithms optimizing delivery of just-in-time digital therapy content. For patients with higher adverse childhood experiences (ACE) scores or genetic risks for comorbidities, digital intervention can include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) combined with self-care practices which can mitigate risks for depression or anxiety. Optimization of digital content may include traumatic circumstances related to personal life, emotional state, or extreme atmospheric conditions.

Self-Care Practices Compatible With Digital Health Technologies

According to the World Health Organization, self-care is “the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and to cope with illness with or without the support of a healthcare provider” (who.int). The concept of self-care comprises self-management (the ability to manage symptoms, treatments and lifestyle changes) and self-efficacy (the level of confidence in one’s ability to practice self-care) (Richard and Shea, 2011). Promoting self-care and lifestyle interventions are particularly applicable to chronic medical conditions (Coulter et al., 2015; Riegel et al., 2017). Table 1 illustrates examples of clinical and physiological effects of self-care practices such as physical exercise, yoga, breathing exercises, mindfulness meditation, music, sleep, gratitude, and forgiveness. Noteworthy, these complimentary practices are also considered safe, non-invasive and without serious adverse effects.

TABLE 1

| Non-pharmacological modality | Examples of clinical benefits | Physiological effects and potential mechanisms of action |

|---|---|---|

| Breathing exercises | ● Reduction of depressive symptoms in MDD Sharma et al. (2017) | ● Modulation of parasympathetic nervous system and cardiac autonomic control Toschi-Dias et al., (2017); Pramanik et al. (2009) |

| ● Improvement of lifespan and HRQoL in people with lung cancer Wu et al. (2017); Liu et al. (2013) | ● Increased neuronal oscillations in the brain Bhaskar et al. (2020) | |

| ● Reduction of chronic low back pain Anderson and Bliven, (2017) | ● Reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and modulation of immune functions Zope and Zope, (2013); Twal et al. (2016) | |

| ● Reduction of epileptic seizures Haut et al. (2018) | ||

| ● Reduction of blood pressure Brandani et al. (2017) | ||

| Mindfulness/meditation | ● Improvements of anxiety, depression and pain Goyal et al. (2014) | ● Activation of anterior cingulate cortex and other brain structures involved in self-regulation of emotions and attention Tang et al. (2015) |

| ● Decrease in pain Hilton et al., (2017); Zeidan and Vago, (2016) | ● Reduced systolic blood pressure, CRP, TNFα Pascoe et al. (2017) | |

| ● Improvements in depression and anxiety, seizure frequency and HRQoL in PWE Wood et al. (2017); Tang et al. (2015) | ||

| ● Improved self-regulation Vago and Silbersweig (2012) | ||

| ● Improved sleep quality Guerra et al. (2020) | ||

| Physical activity | ● Improved cognitive functions Cai et al., (2017) | ● Modulation of the HPA and autonomous Zschucke et al. (2015); Joyner and Green (2009) |

| ● Reduction of cancer-related fatigue Jiang et al. (2020) | ● Modulation of cytokines and immune functions Nieman and Wentz (2019) | |

| ● Reduction of depressive symptoms Gujral et al. (2017) | ● Increase in brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) Dinoff et al., (2017) | |

| ● Pain relief in chronic low back pain Chou et al. (2017) | ||

| Yoga practice | ● Reduction of depressive symptoms Brinsley et al. (2020) | ● Modulation of the sympathetic nervous system and the HPA axis, reduction of cortisol, fasting blood glucose and cholesterol Pascoe et al. (2017) |

| ● Improvements in HRQoL, fatigue, immunity markers, and other physical and psychological symptoms in cancer care Agarwal and Maroko-Afek (2018); Danhauer et al. (2019) | ● Improvement of cardiovascular biomarkers Mohammad et al. (2019) | |

| ● Reduction in pain intensity for low back pain Chou et al. (2017); Nahin et al. (2016) | ● Decrease of pro-inflammatory markers IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα Falkenberg et al. (2018) | |

| ● Improved HRQoL and reduction of epileptic seizures Panebianco et al. (2017) | ||

| ● Reduction of migraine headaches Kumar et al. (2020) | ||

| Listening to music | ● Reduction of depression levels Leubner and Hinterberger (2017); Tang et al. (2020) | ● Modulation of parasympathetic nervous system Mojtabavi et al. (2020) |

| ● Lowering BP, decrease of anxiety and depressive symptoms in breast cancer patients Wang et al., (2018) | ● Modulation of the immune system Chanda and Levitin (2013) | |

| ● Reduction of cancer-related fatigue Qiu et al. (2017) | ● Modulation of dopaminergic system Salimpoor et al. (2011) | |

| ● Reduction of pain Garza-Villarreal et al. (2017); Lee (2016) | ● Modulation of opioid receptors Mallik et al. (2017) | |

| ● Reduction of epileptic seizures Yuen and Sander (2017); Rafiee et al. (2020) | ||

| Adequate sleep | ● Reduced anxiety Pires et al. (2016) | ● Improves inflammatory homeostasis and immune functions Irwin, (2019); Besedovsky et al. (2019) |

| ● Improved all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events Yin et al. (2017) | ● Modulation of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system Irwin, (2019) | |

| ● Improved memory, cognitive functions and emotional regulation Walker (2009) | ● Modulation of synaptic plasticity Raven et al. (2018) | |

| Forgiveness | ● Lower level of pain Carson et al. (2005) | ● Activation of lateral prefrontal cortex and other specific brain structures Fourie et al. (2020) |

| ● Lower levels of anxiety and depression Friedberg et al. (2009) | ● Modulation of the autonomic nervous system, heart rate and blood pressure Witvliet et al. (2001) | |

| ● Lowering blood pressure Lawler et al. (2003) | ||

| Gratitude | ● Improved mental health including symptoms of depression and anxiety Heckendorf et al. (2019); Wong et al. (2018) | ● Activation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex Balconi et al. (2019) |

| ● Improved cognitive performance Balconi et al. (2019) | ● Modulation of cardiovascular stress reactivity Ginty et al., (2020) | |

| ● Improved sleep quality Boggiss et al. (2020) |

Examples of clinically-beneficial self-care modalities and their physiological effects.

Non-pharmacological interventions and self-care practices exert clinical benefits and physiological effects via diverse mechanisms of action. As illustrated in Table 1, self-care can modulate the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system activities. Improving the parasympathetic tone can lead to such clinical outcomes as reduction of inflammation (Bonaz et al., 2018) and epileptic seizures (Sesso and Sicca, 2020; Yuen and Sander, 2017). Interestingly, pleiotropic physiological effects of self-care practices also impact cardiovascular and the immune system functions, further benefitting people who incorporate such “medicinal” self-care practices.

As illustrated in Figure 1A, non-pharmacological interventions for chronic medical conditions can be delivered via mobile and web-based apps (Whitehead and Seaton, 2016). Currently, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a commonly used “active ingredient” in digital therapeutics. Digital health technologies have been shown to deliver diverse modalities including physical exercise, yoga, breathing exercises, mindfulness meditation, music, nutrition, sleep, social support, and gratitude (examples of mobile and web-based apps delivering these modalities are listed in Supplementary Table S2). Notably, digital delivery of such non-pharmacological interventions has already shown clinical benefits for chronic pain (Shebib et al., 2019), depression and anxiety (Pine et al., 2020), cancer (Kim et al., 2018) and epilepsy (Si et al., 2020). Research on mobile and web-based apps support delivery of self-care people with chronic conditions (Supplementary Table S2).

Precision Digital Interventions for Epilepsy, Pain, Depression and Cancer

Precision digital therapies can be defined as software-delivered interventions tailored to individual patient preferences while adjusting the content based on preexisting conditions, adverse experiences and just-in-time circumstances. Noteworthy, software is compatible with just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAI) enabling changes of the therapy content in response to real-life circumstances (Nahum-Shani et al., 2018; Wang and Miller, 2019). Just-in-time adjustments can address such factors as stressful and traumatic situations, atmospheric conditions, or public health emergencies. Figure 1B illustrates diversity of factors which can be incorporated in optimizing digital content for patient-centered care. Developing algorithms which can optimize digital interventions is an exciting new frontier in medicine (Triantafyllidis and Tsanas, 2019).

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) are associated with compromised health outcomes (Bellis et al., 2019), including mental health (Kim et al., 2019) and stress response dysregulation (Jiang et al., 2019). People with ACE scores 4, or higher, are at increased risks for comorbid conditions including depression, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases (Campbell et al., 2016). ACE scores might also be associated with compromised medication non-adherence and therapy outcomes (Derefinko et al., 2019; Korhonen et al., 2015). Another subset of factors which can affect therapy outcomes comprises atmospheric conditions (air pollution, wildfires, floods, extreme weather like high temperatures) (Stewart et al., 2017), and unpredictable circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Aforementioned factors can lead to chronic-stress and inflammation thus further affecting mental and physical health. Clinical applications of genomics enable identification of genetic risks for depression (Wray et al., 2018), metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular complications (Kraja et al., 2014; Warren et al., 2017). Thus, digital content can account for genetic and epigenetic susceptibilities to comorbidities when optimizing non-pharmacological interventions.

Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3 illustrate how clinical and physiological effects of breathing exercises, mindfulness meditation, physical activity, yoga, music, sleep, forgiveness, and gratitude practice can directly benefit people living epilepsy, pain, depression, and cancer. It is important to emphasize that clinical evidence for efficacy and effectiveness of these non-pharmacological modalities vary, further emphasizing needs for large-scale RCTs. Despite knowledge gaps, we describe examples of self-care modalities which could be offered via digital interventions for specific indications. As emphasized in Supplementary Table S3, most modalities are directly applicable as adjunct therapies for epilepsy, pain, depression and cancer, while forgiveness intervention may additionally benefit patients with depression or comorbid depression. Currently, content of mobile apps for people with epilepsy, pain, depression, and cancer is designed for specific indications [e.g., self-management for epilepsy (Si et al., 2020), CBT for depression (Mantani et al., 2017), mindfulness meditation, self-management, physical exercise, education for cancer (Jongerius et al., 2019), a combination of physical therapy, CBT and education for chronic low back pain (Shebib et al., 2019)]. Creating disease-specific digital health ecosystems (Shegog et al., 2020) could expand a repertoire of available self-care modalities for each indication, further supporting more personalized digital interventions.

Epilepsy

Delivery of non-pharmacological interventions and self-care as adjunct digital therapy for people with epilepsy (PWE) was recently described (Afra et al., 2018; Shegog et al., 2020). “Active ingredients” included listening to specific music compositions which were shown to reduce epileptic seizures (Sesso and Sicca, 2020), and additional self-management practices such as adequate sleep, avoidance of seizure triggers and stress management (Afra et al., 2018). The most recent meta-analysis (Sesso and Sicca, 2020) and RCT (Rafiee et al., 2020) of music-based interventions for reduction of epileptic seizures support this “active ingredient” in digital therapeutics. As further illustrated in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3, personalized digital therapies for PWE can also include breathing exercises and engagement in physical activities (Häfele et al., 2017; Haut et al., 2018; Vancampfort et al., 2019). Such modalities could be delivered using digital ecosystems, as described for epilepsy self-management (Shegog et al., 2013; Shegog et al., 2020). Since PWE can experience depression or anxiety as comorbidities, additional self-care features could include yoga, mindfulness meditation, or gratitude journaling. The recent RCT on using a mobile app for epilepsy self-management showed reduction of seizures (Si et al., 2020). Opportunities to combine self-care with antiseizure medications to improve seizure control in people with epilepsy were previously discussed (Bulaj, 2014; Bulaj et al., 2016).

Pain

Pharmacologic treatment of chronic pain often provides inadequate relief and causes unwanted adverse effects; therefore, many individuals turn to non-pharmacological interventions. Literature supports the use of diverse self-care practices for chronic pain management since many interventions have been found to be safe, effective and offer the potential to decrease medication use (Nahin et al., 2016; Tick et al., 2018). For example, precision digital therapies for chronic pain can include a personalized combination of several modalities, such as physical exercises, yoga, meditation mindfulness, music and other non-pharmacological modalities. As shown in Supplementary Table S3, a patient which chronic pain and comorbid depression can further benefit from forgiveness and gratitude interventions. Noteworthy, a meta-analysis investigated the effects of music on pain and found that musical interventions resulted in statistically significant reductions in opioid and non-opioid intake (Lee, 2016). Positive results from testing mobile apps delivering physical therapies and mindfulness training to treat chronic back pain (Shebib et al., 2019; Huber et al., 2017; Priebe et al., 2020) support development of such precision digital technologies for pain indications.

Depression

Depression is considered an underdiagnosed and undertreated condition, treated predominantly with antidepressants and CBT. Despite established efficacy, many patients continue to experience symptoms with these treatment modalities (Cleare et al., 2015). As a result, self-care practices are increasingly being used as adjunctive treatments (Villaggi et al., 2015; van Grieken et al., 2018; Saeed et al., 2019). Digital health technologies have recently emerged as clinically effective methods to deliver self-care interventions to reduce depressive symptoms (Mantani et al., 2017; Moberg et al., 2019; Richards et al., 2020). Precision digital interventions for depression can combine CBT with additional self-care modalities such as breathing exercises (Sharma et al., 2016), listening to music (Schriewer and Bulaj, 2016; Leubner and Hinterberger, 2017), engaging in physical activities (Kvam et al., 2016), forgiveness and gratitude (Supplementary Table S3). A unique opportunity of digital interventions is their capability to adjust digital content and dosing based on ACE scores, as well as unexpected stressors and adversities (Figure 1B). For people with depression who also have higher ACE scores, algorithms can increase a daily dose of recommended physical exercise or specific type of music to enhance modulation of affective states (Fernandez-Sotos et al., 2016). Optimizing digital content can further benefit from integration of daily emotional states and weather forecast, suggesting activities adjusted for just-in-time and real-life circumstances (Figure 1B). For example, based on unfavorable weather for outdoor physical activities, precision digital intervention may instead engage a patient with indoor activities, such as breathing exercises, listening to music and gratitude journaling (Table 1).

Cancer

Integrative cancer care during and after chemotherapy and surgeries includes support for mental and physical health. Diverse non-pharmacological modalities can not only improve fatigue, sleep and HRQoL, but can also strengthen the immune system (Table 1). Digital health technologies for people with cancer include mobile apps for pain relief (Yang et al., 2019), self-management (Fjell et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2018), or videogames designed to promote physical exercise and mental empowerment in pediatric oncology patients (Bruggers et al., 2018; Govender et al., 2015). Personalized digital interventions for oncology patients can provide diverse self-care modalities such as physical exercises, yoga, mindfulness meditations, and breathing exercises (Supplementary Table S3). Since some of these modalities can improve immune system functions [e.g., listening to music or 30-min walking can increase activities of natural killer (NK) cells and lymphocytes (Chanda and Levitin, 2013; Fancourt et al., 2014; Pauwels et al., 2014; Nieman and Wentz, 2019)], such self-care practices can further support anticancer therapies. Potential benefits of these interventions also include reduced symptom distress, decreased unplanned hospitalizations, and improved medication adherence, quality of life and survival (Aapro et al., 2020).

The Immune System

As highlighted by the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, all chronically-ill patients could benefit from improved innate and adaptive immune responses to viral infections. It is timely to emphasize that several self-care modalities, such as adequate sleep, moderate-intensity exercises, breathing exercises and listening music can modulate the immune functions (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). For example, sleep has been linked to susceptibility to viral and bacterial infections and responses to vaccinations (Irwin, 2015; Irwin, 2019). When combined with nutritional interventions (Iddir et al., 2020), such self-care practices have a potential for mitigating viral infections (e.g., seasonal influenza) while also improving immune responses to vaccinations.

Given shortcomings of medication therapies for management of chronic diseases, it is becoming apparent that adjunctive treatment modalities are needed to help patients achieve optimal care outcomes and that care needs to be individualized to account for patient-specific factors and conditions. Precision digital interventions can be adjusted for stressful or traumatic events (personal and family accidents, wildfires) which could trigger additional anxiety and/or depression (Graham et al., 2019). Since atmospheric conditions can impact people with epilepsy (Xu et al., 2016; Brás et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2019), cardiovascular diseases (Stewart et al., 2017), arthritis (Savage et al., 2015), or seasonal affective disorders (Wirz-Justice, 2018), digital therapy can include algorithms which take into account weather forecast. These examples illustrate a unique potential of digital health technologies to optimize interventions based on predictability of seasonal factors and weather forecast. This article specifically highlights the benefits of precision, digital self-care interventions; however, it should be noted that many other digital technology tools exist that provide disease education, symptom tracking, remote provider management, monitoring digital biomarkers, and more.

Precision Metapharmacology: Opportunities and Limitations

Pharmaceutical industry recognizes opportunities to integrate pharmacotherapies with digital health technologies (Hird et al., 2016; Sverdlov et al., 2018) (see also Supplementary Table S1). Precision metapharmacology offers benefits for both patients and the health care systems. This concept is supported by recent developments including: 1) emerging reports on cost-effectiveness and clinical benefits of precision digital care (Jiang et al., 2019; Richards et al., 2020), 2) creating mobile apps for personalized self-management interventions through machine learning algorithms, e.g., (Mork et al., 2018; Sandal et al., 2019; Triantafyllidis and Tsanas, 2019; Miura et al., 2020; Sandal et al., 2020), 3) provider health systems starting to invest in digital health technologies (Safavi et al., 2020), 4) increasing number of studies reporting clinical benefits of “medicinal” self-care practices (Table 1), 5) increasing awareness about limitations of pharmacotherapies for chronic diseases such as medication non-adherence and tolerability/toxicity, and 6) regulatory approvals of mobile medical apps and advances to create drug+digital combination therapies (Bulaj, 2014; Afra et al., 2018; Sverdlov et al., 2018; Patel and Butte, 2020). Development of quantum computing (Arute et al., 2019) may facilitate applications of deep learning algorithms to optimize digital content using big data, internet-of-things (IoT) and biofeedback analyses coupled to just-in-time circumstances (such as atmospheric conditions) (Cianconi et al., 2020; Morganstein and Ursano, 2020).

While apparent opportunities for integrating digital health technologies with pharmacotherapies include improving therapy outcomes (Armitage et al., 2020) and medication adherence (via medication reminders) (Perez-Jover et al., 2019; Pouls et al., 2021), two underappreciated aspects are: 1) patient empowerment and engagement in the therapy (Bruggers et al., 2012; Risling et al., 2017), and 2) health promotion, lifestyle modifications and disease prevention (Naslund et al., 2017; Bonn et al., 2019; Debon et al., 2019). These two aspects can improve public health by decreasing chronic disease burden (Diseases and Injuries, 2020). Targeting lifestyle modifications may also reduce transgenerational transmission of ACE scores and risks for developing chronic medical conditions, further benefiting public health (Oral et al., 2016; Plass-Christl et al., 2017). Another benefit of empowering patients with personalized digital interventions is reducing workload in health care thus mitigating high burnout rates among physicians, physician assistants, nurses and pharmacists (Bridgeman et al., 2018).

Challenges and limitations of developing and implementation of precision digital interventions and metapharmacology have been discussed elsewhere (Hird et al., 2016; Sverdlov et al., 2018; Chung, 2019; Germine et al., 2019; AMCP Partnership Forum, 2020). In summary, these include: 1) cybersecurity and privacy concerns, 2) mismatch between rapid pace for consumer electronics and slower pace of developing therapeutic interventions, 3) regulatory pathways to approve drug+digital combination therapies, 4) patient adherence to digital interventions, 5) implementation and reimbursement, and 6) the lack of data on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of combining pharmacotherapies with digital interventions. Cybersecurity risks for mobile apps connected to the internet and networks are addressed by data encryption, authentication, code integrity, identification of vulnerabilities, and abilities to detect cybersecurity events. Another real-life challenge is patient adherence to digital interventions which may vary depending on type of delivered modalities (Baumel et al., 2019), and can be improved by personalization and gamification (Litvin et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020). While digital interventions are considered as non-invasive and relatively low-risk for patients, the safety of mobile medical apps has not been systemically studied. Implementation, adoption and scalability of digital therapeutics can vary from country to country, and depends on reimbursement policies (Powell et al., 2019; Gordon et al., 2020) and support from patients and health care providers (Sverdlov et al., 2018; AMCP Partnership Forum, 2020; Dang et al., 2020; Patel and Butte, 2020).

Given cross-disciplinary aspects of precision metapharmacology, advancing such technologies require aligning priorities of key stakeholders including research communities, patients, healthcare providers and healthcare industry, as well as regulatory and funding agencies (Varsi et al., 2019). To overcome aforementioned challenges, there are multiple incentives for key stakeholders. For patients, self-care and empowerment delivered via digital technologies offer means to improve therapy outcomes and HRQoL. Notably, since aforementioned self-care practices are complimentary, long-term implementation of these non-pharmacological interventions is not associated with more out-of-pocket expenses. For pharmaceutical and biotech industry, drug+digital combination therapies may offer strengthening intellectual property protections via copyrights of digital content and software (Bulaj, 2014). For health care insurance companies and health care systems, digital interventions offer cost savings (Jiang et al., 2019; Richards et al., 2020). For research communities, precision metapharmacology encourages preclinical and clinical discoveries on improving pharmacotherapies by combining them with non-pharmacological interventions (Metcalf et al., 2019). For governments and funding agencies, developing and delivery of lifestyle interventions offer means to reduce burden of chronic diseases and to improve public health. In summary, advancing precision metapharmacology offers win-win opportunities for health care stakeholders.

Conclusion

Digital health technologies offer new opportunities to integrate health promotion, self-care and lifestyle interventions, while simultaneously mitigating limitations of pharmacotherapies such as medication non-adherence, tolerability, or drug resistance. While we illustrate examples of integrating self-care with pharmacotherapies for epilepsy, pain, depression, and cancer, this strategy applies to diverse chronic conditions including cardiovascular, metabolic, neurodegenerative, pulmonary, infectious diseases and mental disorders. Looking forward and beyond next decade, precision metapharmacology has a potential to treat multiple chronic diseases at both individual and global levels while empowering patients and health care providers. In conclusion, delivery of personalized self-care practices using digital health technologies will innovate precision medicine and patient-centered care.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

EB, GB, JC, and ME searched and analyzed literature, and wrote the article.

Funding

This work was supported by internal funds at the University of Utah. JC and ME acknowledge financial support from internal funds at the University of Utah.

Acknowledgments

GB would like to thank Prof. Adam Kochanski for discussions related to integrating atmospheric conditions into digital health technologies.

Conflict of interest

GB is a founder and owner of OMNI Self-care, LLC, specialized in creating digital content for promoting health and well-being. GB is a co-inventor on two issued US patents 9,569,562 and 9,747,423 “Disease Therapy Game Technology” and patent-pending application “Multimodal Platform for Treating Epilepsy”. These patents are related to digital health technologies for epilepsy and cancer, and are owned by the University of Utah.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2021.612602/full#supplementary-material.

Abbreviations

ACE, adverse childhood experiences; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; HPA, the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MDD, major depressive disorder; PWE, people with epilepsy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SaMD, software as a medical device.

References

1

Aapro M. Bossi P. Dasari A. Fallowfield L. Gascón P. Geller M. et al (2020). Digital health for optimal supportive care in oncology: benefits, limits, and future perspectives. Support Care Cancer28 (10), 4589–4612. 10.1007/s00520-020-05539-1

2

Afra P. Bruggers C. S. Sweney M. Fagatele L. Alavi F. Greenwald M. et al (2018). Mobile software as a medical device (SaMD) for the treatment of epilepsy: development of digital therapeutics comprising behavioral and music-based interventions for neurological disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci.12, 171. 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00171

3

Agarwal R. P. Maroko-Afek A. (2018). Yoga into cancer care: a review of the evidence-based research. Int. J. Yoga11 (1), 3–29. 10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_42_17

4

Alon N. Stern A. D. Torous J. (2020). Assessing the Food and drug administration's risk-based framework for software precertification with top health apps in the United States: quality improvement study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth8 (10), e20482. 10.2196/20482

5

AMCP Partnership Forum (2020). Digital therapeutics-what are They and where Do They Fit in pharmacy and medical benefits?J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm.26 (5), 674–681. 10.18553/jmcp.2020.19418

6

Anderson B. E. Bliven K. C. H. (2017). The use of breathing exercises in the treatment of chronic, nonspecific low back pain. J. Sport Rehabil.26 (5), 452–458. 10.1123/jsr.2015-0199

7

Armitage L. C. Kassavou A. Sutton S. (2020). Do mobile device apps designed to support medication adherence demonstrate efficacy? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials, with meta-analysis. BMJ Open10 (1), e032045. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032045

8

Arute F. Arya K. Babbush R. Bacon D. Bardin J. C. Barends R. et al (2019). Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature574 (7779), 505–510. 10.1038/s41586-019-1666-5

9

Assaraf Y. G. Brozovic A. Gonçalves A. C. Jurkovicova D. Linē A. Machuqueiro M. et al (2019). The multi-factorial nature of clinical multidrug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist. Updates46, 100645. 10.1016/j.drup.2019.100645

10

Balconi M. Fronda G. Vanutelli M. E. (2019). A gift for gratitude and cooperative behavior: brain and cognitive effects. Soc. Cogn. Affect Neurosci.14 (12), 1317–1327. 10.1093/scan/nsaa003

11

Baumel A. Muench F. Edan S. Kane J. M. (2019). Objective user engagement with mental health apps: systematic search and panel-based usage analysis. J. Med. Internet Res.21 (9), e14567. 10.2196/14567

12

Bellis M. A. Hughes K. Ford K. Ramos Rodriguez G. Sethi D. Passmore J. (2019). Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health4 (10), e517–e528. 10.1016/s2468-2667(19)30145-8

13

Besedovsky L. Lange T. Haack M. (2019). The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol. Rev.99 (3), 1325–1380. 10.1152/physrev.00010.2018

14

Bhaskar L. Tripathi V. Kharya C. Kotabagi V. Bhatia M. Kochupillai V. (2020). High-Frequency cerebral activation and interhemispheric synchronization following sudarshan kriya yoga as global brain rhythms: the state effects. Int. J. Yoga13 (2), 130–136. 10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_25_19

15

Boggiss A. L. Consedine N. S. Brenton-Peters J. M. Hofman P. L. Serlachius A. S. (2020). A systematic review of gratitude interventions: effects on physical health and health behaviors. J. Psychosomatic Res.135, 110165. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110165

16

Bonaz B. Bazin T. Pellissier S. (2018). The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota-gut-brain Axis. Front. Neurosci.12, 49. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00049

17

Bonn S. E. Lof M. Ostenson C. G. Trolle Lagerros Y. (2019). App-technology to improve lifestyle behaviors among working adults - the Health Integrator study, a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health19 (1), 273. 10.1186/s12889-019-6595-6

18

Borsook D. Youssef A. M. Simons L. Elman I. Eccleston C. (2018). When pain gets stuck: the evolution of pain chronification and treatment resistance. Pain159 (12), 2421–2436. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001401

19

Brandani J. Z. Mizuno J. Ciolac E. G. Monteiro H. L. (2017). The hypotensive effect of Yoga's breathing exercises: a systematic review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract.28, 38–46. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.05.002

20

Brás P. C. Barros A. Vaz S. Sequeira J. Melancia D. Fernandes A. et al (2018). Influence of weather on seizure frequency - clinical experience in the emergency room of a tertiary hospital. Epilepsy Behav.86, 25–30. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.07.010

21

Bridgeman P. J. Bridgeman M. B. Barone J. (2018). Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm.75 (3), 147–152. 10.2146/ajhp170460

22

Brinsley J. Schuch F. Lederman O. Girard D. Smout M. Immink M. A. et al (2020). Effects of yoga on depressive symptoms in people with mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med.10.1136/bjsports-2019-101242

23

Brown M. T. Bussell J. K. (2011). Medication adherence: WHO cares?. Mayo Clinic Proc.86 (4), 304–314. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0575

24

Bruggers C. S. Baranowski S. Beseris M. Leonard R. Long D. Schulte E. et al (2018). A prototype exercise-empowerment mobile video game for children with cancer, and its usability assessment: developing digital empowerment interventions for pediatric diseases. Front. Pediatr.6, 69. 10.3389/fped.2018.00069

25

Bruggers C. S. Altizer R. A. Kessler R. R. Caldwell C. B. Coppersmith K. Warner L. et al (2012). Patient-empowerment interactive technologies. Sci. Translational Med.4 (152), 152ps16. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004009

26

Bulaj G. Ahern M. Kuhn A. Judkins Z. Bowen R. Chen Y. (2016). Incorporating natural products, pharmaceutical drugs, self-care and digital/mobile health technologies into molecular-behavioral combination therapies for chronic diseases. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol11 (2), 128–145. 10.2174/1574884711666160603012237

27

Bulaj G. (2014). Combining non-pharmacological treatments with pharmacotherapies for neurological disorders: a unique interface of the brain, drug-device, and intellectual property. Front. Neurol.5, 126. 10.3389/fneur.2014.00126

28

Cai H. Li G. Hua S. Liu Y. Chen L. (2017). Effect of exercise on cognitive function in chronic disease patients: a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Interv. Aging12, 773–783. 10.2147/cia.s135700

29

Campbell J. A. Walker R. J. Egede L. E. (2016). Associations between adverse childhood experiences, high-risk behaviors, and morbidity in adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med.50 (3), 344–352. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.022

30

Carson J. W. Keefe F. J. Goli V. Fras A. M. Lynch T. R. Thorp S. R. et al (2005). Forgiveness and chronic low back pain: a preliminary study examining the relationship of forgiveness to pain, anger, and psychological distress. The J. Pain6 (2), 84–91. 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.10.012

31

Chanda M. L. Levitin D. J. (2013). The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn. Sci.17 (4), 179–193. 10.1016/j.tics.2013.02.007

32

Chang K.-C. Wu T.-H. Fann J. C.-Y. Chen S. L. s. Yen A. M.-F. Chiu S. Y.-H. et al (2019). Low ambient temperature as the only meteorological risk factor of seizure occurrence: a multivariate study. Epilepsy Behav.100 (Pt A), 106283. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.04.036

33

Chou R. Deyo R. Friedly J. Skelly A. Hashimoto R. Weimer M. et al (2017). Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American college of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med.166 (7), 493–505. 10.7326/m16-2459

34

Chung J.-Y. (2019). Digital therapeutics and clinical pharmacology. Transl Clin. Pharmacol.27 (1), 6–11. 10.12793/tcp.2019.27.1.6

35

Cianconi P. Betro S. Janiri L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: a systematic descriptive review. Front. Psychiatry11, 74. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

36

Cleare A. Pariante C. Young A. Anderson I. Christmas D. Cowen P. et al (2015). Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J. Psychopharmacol.29 (5), 459–525. 10.1177/0269881115581093

37

Coulter A. Entwistle V. A. Eccles A. Ryan S. Shepperd S. Perera R. (2015). Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2015 (3), CD010523. 10.1002/14651858.CD010523.pub2

38

Dang A. Arora D. Rane P. (2020). Role of digital therapeutics and the changing future of healthcare. J. Fam. Med Prim Care9 (5), 2207–2213. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_105_20

39

Danhauer S. C. Addington E. L. Cohen L. Sohl S. J. Van Puymbroeck M. Albinati N. K. et al (2019). Yoga for symptom management in oncology: a review of the evidence base and future directions for research. Cancer125 (12), 1979–1989. 10.1002/cncr.31979

40

Debon R. Coleone J. D. Bellei E. A. De Marchi A. C. B. (2019). Mobile health applications for chronic diseases: a systematic review of features for lifestyle improvement. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev.13 (4), 2507–2512. 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.07.016

41

Derefinko K. J. Salgado García F. I. Talley K. M. Bursac Z. Johnson K. C. Murphy J. G. et al (2019). Adverse childhood experiences predict opioid relapse during treatment among rural adults. Addict. Behaviors96, 171–174. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.05.008

42

Dinoff A. Herrmann N. Swardfager W. Lanctôt K. L. (2017). The effect of acute exercise on blood concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in healthy adults: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Neurosci.46 (1), 1635–1646. 10.1111/ejn.13603

43

Disease G. B. D. (2018). Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet392 (10159), 1789–1858. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

44

Diseases G. B. D. Injuries C. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet396 (10258), 1204–1222. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

45

Falkenberg R. I. Eising C. Peters M. L. (2018). Yoga and immune system functioning: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Behav. Med.41 (4), 467–482. 10.1007/s10865-018-9914-y

46

Fancourt D. Ockelford A. Belai A. (2014). The psychoneuroimmunological effects of music: a systematic review and a new model. Brain Behav. Immun.36, 15–26. 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.014

47

Fernandez-Sotos A. Fernandez-Caballero A. Latorre J. M. (2016). Influence of tempo and rhythmic unit in musical emotion regulation. Front. Comput. Neurosci.10, 80. 10.3389/fncom.2016.00080

48

Fjell M. Langius-Eklöf A. Nilsson M. Wengström Y. Sundberg K. (2020). Reduced symptom burden with the support of an interactive app during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer - a randomized controlled trial. The Breast51, 85–93. 10.1016/j.breast.2020.03.004

49

Fourie M. M. Hortensius R. Decety J. (2020). Parsing the components of forgiveness: psychological and neural mechanisms. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Rev.112, 437–451. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.020

50

Friedberg J. P. Suchday S. Srinivas V. S. (2009). Relationship between forgiveness and psychological and physiological indices in cardiac patients. Int.J. Behav. Med.16 (3), 205–211. 10.1007/s12529-008-9016-2

51

Garza-Villarreal E. A. Pando V. Vuust P. Parsons C. (2017). Music-induced analgesia in chronic pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician20 (7), 597–610. 10.36076/ppj/2017.7.597

52

Germine L. Reinecke K. Chaytor N. S. (2019). Digital neuropsychology: challenges and opportunities at the intersection of science and software. The Clin. Neuropsychologist33 (2), 271–286. 10.1080/13854046.2018.1535662

53

Ginty A. T. Tyra A. T. Young D. A. John-Henderson N. A. Gallagher S. Tsang J.-A. C. (2020). State gratitude is associated with lower cardiovascular responses to acute psychological stress: a replication and extension. Int. J. Psychophysiology158, 238–247. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.10.005

54

Gordon W. J. Landman A. Zhang H. Bates D. W. (2020). Beyond validation: getting health apps into clinical practice. Npj Digit Med.3, 14. 10.1038/s41746-019-0212-z

55

Govender M. Bowen R. C. German M. L. Bulaj G. Bruggers C. S. (2015). Clinical and neurobiological perspectives of empowering pediatric cancer patients using videogames. Games Health J.4 (5), 362–374. 10.1089/g4h.2015.0014

56

Goyal M. Singh S. Sibinga E. M. S. Gould N. F. Rowland-Seymour A. Sharma R. et al (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med.174 (3), 357–368. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018

57

Graham H. White P. Cotton J. McManus S. (2019). Flood- and weather-damaged homes and mental health: an analysis using england's mental health survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health16 (18).325610.3390/ijerph16183256

58

Guerra P. C. Santaella D. F. D'Almeida V. Santos-Silva R. Tufik S. Len C. A. (2020). Yogic meditation improves objective and subjective sleep quality of healthcare professionals. Complement. Therapies Clin. Pract.40, 101204. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101204

59

Gujral S. Aizenstein H. Reynolds C. F. 3rd Butters M. A. Erickson K. I. (2017). Exercise effects on depression: possible neural mechanisms. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry49, 2–10. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.012

60

Häfele C. A. Freitas M. P. da Silva M. C. Rombaldi A. J. (2017). Are physical activity levels associated with better health outcomes in people with epilepsy?. Epilepsy Behav.72, 28–34. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.04.038

61

Haut S. R. Lipton R. B. Cornes S. Dwivedi A. K. Wasson R. Cotton S. et al (2018). Behavioral interventions as a treatment for epilepsy: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Neurology90 (11), e963–e970. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000005109

62

Heckendorf H. Lehr D. Ebert D. D. Freund H. (2019). Efficacy of an internet and app-based gratitude intervention in reducing repetitive negative thinking and mechanisms of change in the intervention's effect on anxiety and depression: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther.119, 103415. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103415

63

Hilton L. Hempel S. Ewing B. A. Apaydin E. Xenakis L. Newberry S. et al (2017). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Behav. Med.51 (2), 199–213. 10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2

64

Hird N. Ghosh S. Kitano H. (2016). Digital health revolution: perfect storm or perfect opportunity for pharmaceutical R&D?Drug Discov. Today21 (6), 900–911. 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.01.010

65

Huber S. Priebe J. A. Baumann K.-M. Plidschun A. Schiessl C. Tölle T. R. (2017). Treatment of low back pain with a digital multidisciplinary pain treatment app: short-term results. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol.4 (2), e11. 10.2196/rehab.9032

66

Iddir M. Brito A. Dingeo G. Fernandez Del Campo S. S. Samouda H. La Frano M. R. et al (2020). Strengthening the immune system and reducing inflammation and oxidative stress through diet and nutrition: considerations during the COVID-19 crisis. Nutrients12 (6). 156210.3390/nu12061562

67

Irwin M. R. (2019). Sleep and inflammation: partners in sickness and in health. Nat. Rev. Immunol.19 (11), 702–715. 10.1038/s41577-019-0190-z

68

Irwin M. R. (2015). Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol.66, 143–172. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115205

69

Jiang M. Ma Y. Yun B. Wang Q. Huang C. Han L. (2020). Exercise for fatigue in breast cancer patients: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Sci.7 (2), 248–254. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.03.001

70

Jiang S. Postovit L. Cattaneo A. Binder E. B. Aitchison K. J. (2019). Epigenetic modifications in stress response genes associated with childhood trauma. Front. Psychiatry10, 808. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00808

71

Jiang X. Ming W. K. You J. H. (2019). The cost-effectiveness of digital health interventions on the management of cardiovascular diseases: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res.21 (6), e13166. 10.2196/13166

72

Jongerius C. Russo S. Mazzocco K. Pravettoni G. (2019). Research-tested mobile apps for breast cancer care: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth7 (2), e10930. 10.2196/10930

73

Joyner M. J. Green D. J. (2009). Exercise protects the cardiovascular system: effects beyond traditional risk factors. J. Physiol.587 (Pt 23), 5551–5558. 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.179432

74

Kesselheim A. S. Avorn J. Sarpatwari A. (2016). The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: Origins and Prospects for Reform. JAMA316 (8), 858–871. 10.1001/jama.2016.11237

75

Kim H. J. Kim S. M. Shin H. Jang J.-S. Kim Y. I. Han D. H. (2018). A mobile game for patients with breast cancer for chemotherapy self-management and quality-of-life improvement: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res.20 (10), e273. 10.2196/jmir.9559

76

Kim Y. Kim K. Chartier K. G. Wike T. L. McDonald S. E. (2019). Adverse childhood experience patterns, major depressive disorder, and substance use disorder in older adults. Aging Ment. Health,25 (3), 484–489. 10.1080/13607863.2019.1693974

77

Korhonen M. J. Halonen J. I. Brookhart M. A. Kawachi I. Pentti J. Karlsson H. et al (2015). Childhood adversity as a predictor of non-adherence to statin therapy in adulthood. PLoS One10 (5), e0127638. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127638

78

Kraja A. T. Chasman D. I. North K. E. Reiner A. P. Yanek L. R. Kilpeläinen T. O. et al (2014). Pleiotropic genes for metabolic syndrome and inflammation. Mol. Genet. Metab.112 (4), 317–338. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.04.007

79

Kumar A. Bhatia R. Sharma G. Dhanlika D. Vishnubhatla S. Singh R. K. et al (2020). Effect of yoga as add-on therapy in migraine (CONTAIN): a randomized clinical trial. Neurology94 (21), e2203–e2212. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000009473

80

Kvam S. Kleppe C. L. Nordhus I. H. Hovland A. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis. J. Affective Disord.202, 67–86. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.063

81

Kwan P. Schachter S. C. Brodie M. J. (2011). Drug-resistant epilepsy. N. Engl. J. Med.365 (10), 919–926. 10.1056/nejmra1004418

82

Lawler K. A. Younger J. W. Piferi R. L. Billington E. Jobe R. Edmondson K. et al (2003). A change of heart: cardiovascular correlates of forgiveness in response to interpersonal conflict. J. Behav. Med.26 (5), 373–393. 10.1023/a:1025771716686

83

Lee J. H. (2016). The effects of music on pain: a meta-analysis. Jmther53 (4), 430–477. 10.1093/jmt/thw012

84

Leubner D. Hinterberger T. (2017). Reviewing the effectiveness of music interventions in treating depression. Front. Psychol.8, 1109. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01109

85

Litvin S. Saunders R. Maier M. A. Luttke S. (2020). Gamification as an approach to improve resilience and reduce attrition in mobile mental health interventions: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One15 (9), e0237220. 10.1371/journal.pone.0237220

86

Liu W. Pan Y.-L. Gao C.-X. Shang Z. Ning L.-J. Liu X. (2013). Breathing exercises improve post-operative pulmonary function and quality of life in patients with lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Exp. Ther. Med.5 (4), 1194–1200. 10.3892/etm.2013.926

87

Mallik A. Chanda M. L. Levitin D. J. (2017). Anhedonia to music and mu-opioids: evidence from the administration of naltrexone. Sci. Rep.7, 41952. 10.1038/srep41952

88

Mantani A. Kato T. Furukawa T. A. Horikoshi M. Imai H. Hiroe T. et al (2017). Smartphone cognitive behavioral therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for refractory depression: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res.19 (11), e373. 10.2196/jmir.8602

89

Metcalf C. S. Huntsman M. Garcia G. Kochanski A. K. Chikinda M. Watanabe E. et al (2019). Music-Enhanced analgesia and antiseizure activities in animal models of pain and epilepsy: toward preclinical studies supporting development of digital therapeutics and their combinations with pharmaceutical drugs. Front. Neurol.10, 277. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00277

90

Miura K. Goto S. Katsumata Y. Ikura H. Shiraishi Y. Sato K. et al (2020). Feasibility of the deep learning method for estimating the ventilatory threshold with electrocardiography data. Npj Digit Med.3 (1), 141. 10.1038/s41746-020-00348-6

91

Moberg C. Niles A. Beermann D. (2019). Guided self-help works: randomized waitlist controlled trial of pacifica, a mobile app integrating cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness for stress, anxiety, and depression. J. Med. Internet Res.21 (6), e12556. 10.2196/12556

92

Mohammad A. Thakur P. Kumar R. Kaur S. Saini R. V. Saini A. K. (2019). Biological markers for the effects of yoga as a complementary and alternative medicine. J. Complement. Integr. Med.16 (1), 1–15. 10.1515/jcim-2018-0094

93

Mojtabavi H. Saghazadeh A. Valenti V. E. Rezaei N. (2020). Can music influence cardiac autonomic system? A systematic review and narrative synthesis to evaluate its impact on heart rate variability. Complement. Therapies Clin. Pract.39, 101162. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101162

94

Monnat S. M. (2018). Factors associated with county-level differences in U.S. Drug-related mortality rates. Am. J. Prev. Med.54 (5), 611–619. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.040

95

Morganstein J. C. Ursano R. J. (2020). Ecological disasters and mental health: causes, consequences, and interventions. Front. Psychiatry11, 1. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00001

96

Mork P. J. Bach K. self B. C. (2018). A decision support system to enhance self-management of low back pain: protocol for the selfBACK project. JMIR Res. Protoc.7 (7), e167. 10.2196/resprot.9379

97

Nahin R. L. Boineau R. Khalsa P. S. Stussman B. J. Weber W. J. (2016). Evidence-based evaluation of complementary health approaches for pain management in the United States. Mayo Clinic Proc.91 (9), 1292–1306. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.007

98

Nahum-Shani I. Smith S. N. Spring B. J. Collins L. M. Witkiewitz K. Tewari A. et al (2018). Just-in-Time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Ann. Behav. Med.52 (6), 446–462. 10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8

99

Naslund J. A. Aschbrenner K. A. Araya R. Marsch L. A. Unützer J. Patel V. et al (2017). Digital technology for treating and preventing mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries: a narrative review of the literature. The Lancet Psychiatry4 (6), 486–500. 10.1016/s2215-0366(17)30096-2

100

Nieman D. C. Wentz L. M. (2019). The compelling link between physical activity and the body's defense system. J. Sport Health Sci.8 (3), 201–217. 10.1016/j.jshs.2018.09.009

101

Nordyke R. J. Appelbaum K. Berman M. A. (2019). Estimating the impact of novel digital therapeutics in type 2 diabetes and hypertension: health economic analysis. J. Med. Internet Res.21 (10), e15814. 10.2196/15814

102

Oral R. Ramirez M. Coohey C. Nakada S. Walz A. Kuntz A. et al (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and trauma informed care: the future of health care. Pediatr. Res.79 (1-2), 227–233. 10.1038/pr.2015.197

103

Pandarakalam J. P. (2018). Challenges of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiat Danub30 (3), 273–284. 10.24869/psyd.2018.273

104

Panebianco M. Sridharan K. Ramaratnam S. (2017). Yoga for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.10 (10), CD001524. 10.1002/14651858.CD001524.pub3

105

Pascoe M. C. Thompson D. R. Jenkins Z. M. Ski C. F. (2017). Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res.95, 156–178. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.004

106

Pascoe M. C. Thompson D. R. Ski C. F. (2017). Yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and stress-related physiological measures: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology86, 152–168. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.08.008

107

Patel N. A. Butte A. J. (2020). Characteristics and challenges of the clinical pipeline of digital therapeutics. Npj Digit Med.3 (1), 159. 10.1038/s41746-020-00370-8

108

Pauwels E. K. J. Volterrani D. Mariani G. Kostkiewics M. (2014). Mozart, music and medicine. Med. Princ Pract.23 (5), 403–412. 10.1159/000364873

109

Perez-Jover V. Sala-Gonzalez M. Guilabert M. Mira J. J. (2019). Mobile apps for increasing treatment adherence: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res.21 (6), e12505. 10.2196/12505

110

Pine R. Fleming T. McCallum S. Sutcliffe K. (2020). The effects of casual videogames on anxiety, depression, stress, and low mood: a systematic review. Games Health J.9 (4), 255–264. 10.1089/g4h.2019.0132

111

Pires G. N. Bezerra A. G. Tufik S. Andersen M. L. (2016). Effects of acute sleep deprivation on state anxiety levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med.24, 109–118. 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.019

112

Plass-Christl A. Haller A. C. Otto C. Barkmann C. Wiegand-Grefe S. Holling H. et al (2017). Parents with mental health problems and their children in a German population based sample: results of the BELLA study. PLoS One12 (7), e0180410. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180410

113

Pouls B. P. H. Vriezekolk J. E. Bekker C. L. Linn A. J. van Onzenoort H. A. W. Vervloet M. et al (2021). Effect of interactive eHealth interventions on improving medication adherence in adults with long-term medication: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res.23 (1), e18901. 10.2196/18901

114

Powell A. C. Bowman M. B. Harbin H. T. (2019). Reimbursement of apps for mental health: findings from interviews. JMIR Ment. Health6 (8), e14724. 10.2196/14724

115

Pramanik T. Sharma H. O. Mishra S. Mishra A. Prajapati R. Singh S. (2009). Immediate effect of slow PaceBhastrika pranayamaon blood pressure and heart rate. J. Altern. Complement. Med.15 (3), 293–295. 10.1089/acm.2008.0440

116

Priebe J. A. Haas K. K. Moreno Sanchez L. F. Schoefmann K. Utpadel-Fischler D. A. Stockert P. et al (2020). Digital treatment of back pain versus standard of care: the cluster-randomized controlled trial, rise-uP. J Pain ResVol. 13, 1823–1838. 10.2147/jpr.s260761

117

Qiu J. Jiang Y. F. Li F. Tong Q. H. Rong H. Cheng R. (2017). Effect of combined music and touch intervention on pain response and beta-endorphin and cortisol concentrations in late preterm infants. BMC Pediatr.17 (1), 38. 10.1186/s12887-016-0755-y

118

Rafiee M. Patel K. Groppe D. M. Andrade D. M. Bercovici E. Bui E. et al (2020). Daily listening to Mozart reduces seizures in individuals with epilepsy: a randomized control study. Epilepsia Open5 (2), 285–294. 10.1002/epi4.12400

119

Raven F. Van der Zee E. A. Meerlo P. Havekes R. (2018). The role of sleep in regulating structural plasticity and synaptic strength: implications for memory and cognitive function. Sleep Med. Rev.39, 3–11. 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.05.002

120

Richard A. A. Shea K. (2011). Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. J. Nurs. Scholarsh43 (3), 255–264. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01404.x

121

Richards D. Enrique A. Eilert N. Franklin M. Palacios J. Duffy D. et al (2020). A pragmatic randomized waitlist-controlled effectiveness and cost-effectiveness trial of digital interventions for depression and anxiety. Npj Digit Med.3, 85. 10.1038/s41746-020-0293-8

122

Riegel B. Moser D. K. Buck H. G. Dickson V. V. Dunbar S. B. Lee C. S. et al (2017). Self-care for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and stroke: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association. J. Am. Heart Assoc.6 (9). e00699710.1161/jaha.117.006997

123

Risling T. Martinez J. Young J. Thorp-Froslie N. (2017). Evaluating patient empowerment in association with eHealth technology: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res.19 (9), e329. 10.2196/jmir.7809

124

Rowland S. P. Fitzgerald J. E. Holme T. Powell J. McGregor A. (2020). What is the clinical value of mHealth for patients?. Npj Digit Med.3, 4. 10.1038/s41746-019-0206-x

125

Saeed S. A. Cunningham K. Bloch R. M. (2019). Depression and anxiety disorders: benefits of exercise, yoga, and meditation. Am. Fam. Physician99 (10), 620–627.

126

Safavi K. C. Cohen A. B. Ting D. Y. Chaguturu S. Rowe J. S. (2020). Health systems as venture capital investors in digital health: 2011-2019. Npj Digit Med.3, 103. 10.1038/s41746-020-00311-5

127

Salimpoor V. N. Benovoy M. Larcher K. Dagher A. Zatorre R. J. (2011). Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat. Neurosci.14 (2), 257–262. 10.1038/nn.2726

128

Sandal L. F. Overas C. K. Nordstoga A. L. Wood K. Bach K. Hartvigsen J. et al (2020). A digital decision support system (selfBACK) for improved self-management of low back pain: a pilot study with 6-week follow-up. Pilot Feasibility Stud.6, 72. 10.1186/s40814-020-00604-2

129

Sandal L. F. Stochkendahl M. J. Svendsen M. J. Wood K. Overas C. K. Nordstoga A. L. et al (2019). An app-delivered self-management program for people with low back pain: protocol for the selfBACK randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc.8 (12), e14720. 10.2196/14720

130

Savage E. M. McCormick D. McDonald S. Moore O. Stevenson M. Cairns A. P. (2015). Does rheumatoid arthritis disease activity correlate with weather conditions?. Rheumatol. Int.35 (5), 887–890. 10.1007/s00296-014-3161-5

131

Schriewer K. Bulaj G. (2016). Music streaming services as adjunct therapies for depression, anxiety, and bipolar symptoms: convergence of digital technologies, mobile apps, emotions, and global mental health. Front. Public Health4, 217. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00217

132

Sesso G. Sicca F. (2020). Safe and sound: meta-analyzing the Mozart effect on epilepsy. Clin. Neurophysiol.131 (7), 1610–1620. 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.03.039

133

Sharma A. Barrett M. S. Cucchiara A. J. Gooneratne N. S. Thase M. E. (2016). A breathing-based meditation intervention for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a randomized pilot study. J. Clin. Psychiatry78 (1), e59–e63. 10.4088/JCP.16m10819

134

Sharma A. Barrett M. S. Cucchiara A. J. Gooneratne N. S. Thase M. E. (2017). A breathing-based meditation intervention for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a randomized pilot study. J. Clin. Psychiatry78 (1), e59–e63. 10.4088/jcp.16m10819

135

Shebib R. Bailey J. F. Smittenaar P. Perez D. A. Mecklenburg G. Hunter S. (2019). Randomized controlled trial of a 12-week digital care program in improving low back pain. Npj Digit Med.21. 10.1038/s41746-018-0076-7

136

Shegog R. Bamps Y. A. Patel A. Kakacek J. Escoffery C. Johnson E. K. et al (2013). Managing epilepsy well: emerging e-tools for epilepsy self-management. Epilepsy Behav.29 (1), 133–140. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.07.002

137

Shegog R. Braverman L. Hixson J. D. (2020). Digital and technological opportunities in epilepsy: toward a digital ecosystem for enhanced epilepsy management. Epilepsy Behav.102, 106663. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.106663

138

Shuren J. Patel B. Gottlieb S. (2018). FDA regulation of mobile medical apps. JAMA320 (4), 337–338. 10.1001/jama.2018.8832

139

Si Y. Xiao X. Xia C. Guo J. Hao Q. Mo Q. et al (2020). Optimising epilepsy management with a smartphone application: a randomised controlled trial. Med. J. Aust.212 (6), 258–262. 10.5694/mja2.50520

140

Sin J. Galeazzi G. McGregor E. Collom J. Taylor A. Barrett B. et al (2020). Digital interventions for screening and treating common mental disorders or symptoms of common mental illness in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res.22 (9), e20581. 10.2196/20581

141

Stewart S. Keates A. K. Redfern A. McMurray J. J. V. (2017). Seasonal variations in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.14 (11), 654–664. 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.76

142

Sverdlov O. van Dam J. Hannesdottir K. Thornton-Wells T. (2018). Digital therapeutics: an integral component of digital innovation in drug development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.104 (1), 72–80. 10.1002/cpt.1036

143

Tang Q. Huang Z. Zhou H. Ye P. (2020). Effects of music therapy on depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One15 (11), e0240862. 10.1371/journal.pone.0240862

144

Tang V. Poon W. S. Kwan P. (2015). Mindfulness-based therapy for drug-resistant epilepsy: an assessor-blinded randomized trial. Neurology85 (13), 1100–1107. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000001967

145

Tang Y.-Y. Hölzel B. K. Posner M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.16 (4), 213–225. 10.1038/nrn3916

146

Tick H. Nielsen A. Pelletier K. R. Bonakdar R. Simmons S. Glick R. et al (2018). Evidence-based nonpharmacologic strategies for comprehensive pain care: The consortium pain task force white paper.Explore14 (3), 177–211. 10.1016/j.explore.2018.02.001

147

Toschi-Dias E. Tobaldini E. Solbiati M. Costantino G. Sanlorenzo R. Doria S. et al (2017). Sudarshan Kriya Yoga improves cardiac autonomic control in patients with anxiety-depression disorders. J. Affective Disord.214, 74–80. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.017

148

Triantafyllidis A. K. Tsanas A. (2019). Applications of machine learning in real-life digital health interventions: review of the literature. J. Med. Internet Res.21 (4), e12286. 10.2196/12286

149

Twal W. O. Wahlquist A. E. Balasubramanian S. (2016). Yogic breathing when compared to attention control reduces the levels of pro-inflammatory biomarkers in saliva: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.16, 294. 10.1186/s12906-016-1286-7

150

Vago D. R. Silbersweig D. A. (2012). Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): a framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Front. Hum. Neurosci.6, 296. 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00296

151

van Grieken R. A. van Tricht M. J. Koeter M. W. J. van den Brink W. Schene A. H. (2018). The use and helpfulness of self-management strategies for depression: the experiences of patients. PLoS One13 (10), e0206262. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206262

152

Vancampfort D. Ward P. B. Stubbs B. (2019). Physical activity and sedentary levels among people living with epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav.99, 106390. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.05.052

153

Varsi C. Solberg Nes L. Kristjansdottir O. B. Kelders S. M. Stenberg U. Zangi H. A. et al (2019). Implementation strategies to enhance the implementation of eHealth programs for patients with chronic illnesses: realist systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res.21 (9), e14255. 10.2196/14255

154

Villaggi B. Provencher H. Coulombe S. Meunier S. Radziszewski S. Hudon C. et al (2015). Self-management strategies in recovery from mood and anxiety disorders. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res.2, 2333393615606092. 10.1177/2333393615606092

155

Walker M. P. (2009). The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci.1156, 168–197. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04416.x

156

Wang L. Miller L. C. (2019). Just-in-the-Moment adaptive interventions (JITAI): a meta-analytical review. Health Commun.35 (12), 1531–1544. 10.1080/10410236.2019.1652388

157

Wang X. Zhang Y. Fan Y. Tan X.-S. Lei X. (2018). Effects of music intervention on the physical and mental status of patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Care13 (3), 183–190. 10.1159/000487073

158

Warren H. R. Evangelou E. Cabrera C. P. Gao H. Ren M. Mifsud B. et al (2017). Genome-wide association analysis identifies novel blood pressure loci and offers biological insights into cardiovascular risk. Nat. Genet.49 (3), 403–415. 10.1038/ng.3768

159

Wei Y. Zheng P. Deng H. Wang X. Li X. Fu H. (2020). Design features for improving mobile health intervention user engagement: systematic review and thematic analysis. J. Med. Internet Res.22 (12), e21687. 10.2196/21687

160

Whitehead L. Seaton P. (2016). The effectiveness of self-management mobile phone and tablet apps in long-term condition management: a systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res.18 (5), e97. 10.2196/jmir.4883

161

Wirz-Justice A. (2018). Seasonality in affective disorders. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.258, 244–249. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.07.010

162

Witvliet C. v. O. Ludwig T. E. Laan K. L. V. (2001). Granting forgiveness or harboring grudges: implications for emotion, physiology, and health. Psychol. Sci.12 (2), 117–123. 10.1111/1467-9280.00320

163

Wong Y. J. Owen J. Gabana N. T. Brown J. W. McInnis S. Toth P. et al (2018). Does gratitude writing improve the mental health of psychotherapy clients? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Res.28 (2), 192–202. 10.1080/10503307.2016.1169332

164

Wood K. Lawrence M. Jani B. Simpson R. Mercer S. W. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions in epilepsy: a systematic review. BMC Neurol.17 (1), 52. 10.1186/s12883-017-0832-3

165

Wray N. R. Ripke S. Mattheisen M. Trzaskowski M. Byrne E. M. Abdellaoui A. et al (2018). Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet.50 (5), 668–681. 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3

166

Wu W. J. Wang S. H. Ling W. Geng L. J. Zhang X. X. Yu L. et al (2017). Morning breathing exercises prolong lifespan by improving hyperventilation in people living with respiratory cancer. Medicine (Baltimore)96 (2), e5838. 10.1097/md.0000000000005838

167

Xu C. Fan Y. N. Kan H. D. Chen R. J. Liu J. H. Li Y. F. et al (2016). The novel relationship between urban air pollution and epilepsy: a time series study. PLoS One11 (8), e0161992. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161992

168

Yang J. Weng L. Chen Z. Cai H. Lin X. Hu Z. et al (2019). Development and testing of a mobile app for pain management among cancer patients discharged from hospital treatment: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth7 (5), e12542. 10.2196/12542

169

Yin J. Jin X. Shan Z. Li S. Huang H. Li P. et al (2017). Relationship of sleep duration with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc.6 (9). 10.1161/jaha.117.005947

170

Yuen A. W. C. Sander J. W. (2017). Can natural ways to stimulate the vagus nerve improve seizure control?. Epilepsy Behav.67, 105–110. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.10.039

171

Zeidan F. Vago D. R. (2016). Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: a mechanistic account. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci.1373 (1), 114–127. 10.1111/nyas.13153

172

Zope S. Zope R. (2013). Sudarshan kriya yoga: breathing for health. Int. J. Yoga6 (1), 4–10. 10.4103/0973-6131.105935

173

Zschucke E. Renneberg B. Dimeo F. Wüstenberg T. Ströhle A. (2015). The stress-buffering effect of acute exercise: evidence for HPA axis negative feedback. Psychoneuroendocrinology51, 414–425. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.019

Summary

Keywords

mHealth, prescription medications, telemedicine, machine learning, pharmacy care, internet, self-management, software as a medical device

Citation

Bulaj G, Clark J, Ebrahimi M and Bald E (2021) From Precision Metapharmacology to Patient Empowerment: Delivery of Self-Care Practices for Epilepsy, Pain, Depression and Cancer Using Digital Health Technologies. Front. Pharmacol. 12:612602. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.612602

Received

30 September 2020

Accepted

22 February 2021

Published

23 April 2021

Volume

12 - 2021

Edited by

Silvio Barberato-Filho, University of Sorocaba, Brazil

Reviewed by

Joao Massud, Independent researcher, São Paulo, Brazil

Karina Cogo Muller, University of Campinas, Brazil

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Bulaj, Clark, Ebrahimi and Bald.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Grzegorz Bulaj, bulaj@pharm.utah.edu

This article was submitted to Pharmaceutical Medicine and Outcomes Research, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pharmacology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.