Abstract

Background:

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) remains the most effective treatment for many patients with severe and/or resistant psychiatric disorders. Right unilateral (RUL) ECT, particularly when administered with titration and ultrabrief pulses, provides cognitive advantages compared with bitemporal (BT) ECT without compromising efficacy. However, some patients fail to improve and require switching to BT ECT. The present study aims to evaluate variables associated with efficacy and tolerability during RUL ECT and, when needed, after switching to BT ECT, aiming to identify factors linked to better outcomes with each placement.

Methods:

A retrospective review was conducted on 58 adult inpatients treated with RUL ECT. Patients without improvement after 4–6 sessions could be switched to BT ECT. Demographic, clinical, pharmacological, and electric seizure-related data were collected. Treatment response was classified as total, partial, or none. Tolerability was assessed based on common side effects. Group comparisons were performed between RUL and BT ECT periods, and between unswitched and switched patients. Supplementary analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between efficacy/tolerability and the studied variables.

Results:

Of the patients who began with RUL ECT, 18 (31%) were switched to BT ECT. Remission occurred in 40% with RUL ECT and reached 55% cumulatively after BT ECT. Adverse effect rates were comparable between groups. Compared to patients who continued with the RUL ECT, those requiring switching had more prior manic episodes (p < 0.05), higher current antipsychotic use (p < 0.05), and a tendency for ECT to be indicated more often for severity than for treatment resistance (p < 0.10). Within the switched subgroup, clozapine use and ECT charge increased during BT sessions compared to the RUL course (p < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Initiating treatment with RUL ECT and transitioning to BT ECT when necessary offers a pragmatic balance between tolerability and efficacy. Certain clinical variables may guide clinicians in anticipating the need for switching from a RUL to a BT setup.

1 Introduction

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) remains the most effective treatment for severe or resistant psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder (BD), psychotic disorders, and catatonia (1, 2). Safety improved early in the history of ECT with the introduction of anesthesia and muscle relaxation (3), yet the optimal protocol remains to be clarified. Bilateral (bitemporal [BT] or bifrontal) ECT is widely used and considered highly effective, producing rapid effects but carrying a higher risk of cognitive adverse effects, particularly memory disturbance (1, 2, 4). Right unilateral (RUL) ECT offers a more favorable cognitive profile and comparable efficacy when delivered at high doses, although some studies reported slower or less consistent improvement than BT (1, 5–15). Other determinants include the method for determining the electric charge (age-based method [ABM] vs. titration method [TM]) and the pulse width (ultrabrief [UBP] vs. brief [BP]) (1, 16), with best cognitive tolerability achieved combining TM, RUL, and UBP (2, 4, 7, 17–21).

Despite its efficacy, ECT remains underused due to stigma and cognitive risks, reinforcing the need for best practices to optimize acceptability and outcomes (2, 22). International guidelines (e.g., Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [CANMAT]; 1) recommend starting with RUL and switching to BT if response is insufficient. A proportion of patients ultimately require such a switch to achieve remission (11, 14, 23–25). This sequential approach balances efficacy and tolerability, though predictors of RUL non-response and optimal switching remain unclear.

In France, BT with ABM has been the usual practice (26). At Sainte Anne Hospital - the largest psychiatric hospital in Paris performing more than 2700 ECT sessions yearly (3168 in 2024) - practices shifted in September 2023 when the Institute of Neuromodulation (INM) introduced TM, RUL, and UBP (0.3 ms) instead of ABM, BT, and near-UBP (0.5 ms), in line with international recommendations (1). If no signs of clinical improvement are seen after 4–6 sessions compared to the patient’s baseline, retitration could be performed in order to continue the ECT course with BT and BP (1 ms). ABM and BT were reserved for urgent cases. Systematic charge escalation was discouraged across the sessions, except after three consecutive poor-quality seizures following a good one according to Nobler’s criteria (27). In this case a 10–20% increase is allowed. A previous INM study showed that this protocol (TM, RUL, UBP) reduced the frequency of memory disturbance by 23%, while maintaining efficacy compared with earlier practices (2).

Few studies have examined predictors of ECT outcomes (28–31), and even fewer investigated sequential response to different ECT parameters (4, 11, 32). In particular, little is known about factors predicting inadequate RUL response requiring a switch to BT ECT. The present study therefore evaluated variables associated with efficacy and tolerability during RUL ECT and, when needed, after switching to BT ECT, aiming to identify factors linked to better outcomes with each placement.

The primary objective was to assess the relationship between patient-related and ECT-related variables (clinical and sociodemographic factors, administered charge, seizure duration, PIS) and clinical outcomes (efficacy and tolerability) during RUL ECT, and after a switch to BT in non-responders. Secondary objectives were (1) to compare outcomes between RUL and BT courses in patients who underwent the RUL-BT switch, and (2) to compare variables according to treatment outcomes (efficacy and tolerability) within each course. The study thus aimed to help identify patient profiles more likely to benefit from switching and refine evidence-based strategies for optimizing electrode placement and treatment sequencing.

2 Materials and methods

This retrospective, monocentric observational study was conducted by the INM at Sainte-Anne Hospital, GHU Paris Psychiatrie & Neurosciences, Paris, France. It included patients treated with ECT under the new protocol (RUL, UBP, TM) between September 1, 2023, and June 30, 2025. Treatment procedures followed international ECT guidelines. Data collected during routine care were retrospectively reviewed and anonymized to ensure confidentiality. The study was conducted in accordance with French regulations on retrospective studies, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from patients and/or their legal representatives before treatment initiation.

2.1 Participants

The sample included 58 hospitalized patients who underwent an acute ECT course. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years and admission to the psychiatric units of the Pôle Hospitalo-Universitaire Paris 15 to receive acute ECT for a psychiatric indication using TM and RUL electrode placement. Exclusion criteria were: urgent clinical presentation requiring acute BT ECT with ABM (as determined by the referring psychiatrist), contraindication to ECT or general anesthesia (as determined by the anesthesiologist), or receipt of consolidation/maintenance rather than acute ECT.

2.2 Treatment protocol

ECT sessions were performed with the MECTA Spectrum 5000M or MECTA ∑igma (MECTA Corporation, Portland, OR, USA), delivering pulsed alternating currents (11–1152 mC; 800 mA; 20–120 Hz) with pulse widths of 0.3 or 1 ms. Anesthesia consisted of etomidate (0.15 mg/kg) or, rarely, propofol. Neuromuscular blockade was performed using suxamethonium (0.5 mg/kg). Assisted hyperventilation was performed using a balloon mask. In the first RUL course (UBP: 0.3 ms, d’Elia placement, suprathreshold dose: 6 × seizure threshold [ST]), ST was defined as the lowest dose inducing a seizure ≥20 s, determined by TM titration tables (2, 5, 8, 27, 33). Dose adjustment followed previously described procedures aimed at avoiding unnecessary escalation (2). If no signs of clinical improvement compared to the patient’s baseline – based on clinician’s judgment and reported in the medical charts – were seen after 4–6 sessions, switching to a BT course was possible after a new titration (BP: 1 ms, 1.5 × ST) using TM (2, 5, 8, 27, 33).

Treatment frequency was 2 sessions/week for treatment-resistant cases and up to 3/week for some severe cases, with the number of sessions individualized. Concomitant pharmacological adjustments followed standard recommendations (2, 34–38): antidepressants and antipsychotics were continued; clozapine was given the night before but not the morning of ECT; lithium was withheld the night before and the morning of ECT; benzodiazepines were tapered or substituted with short half-life agents and omitted the evening and morning before ECT; anticonvulsants were discontinued unless needed for epilepsy, with lamotrigine considered compatible. Patients abstained from tobacco and alcohol for at least 12 h before sessions.

Sessions were monitored with scalp electroencephalography (EEG). The INM organized regular training for physicians performing ECT sessions and interpreting EEG to ensure that readings are standardized according to Nobler’s criteria. Additionally, a physician from the INM was present during ECT sessions to supervise the readings.

According to Nobler’s criteria, a good-quality seizure induced by ECT lasts at least 20 s and consists of a generalized seizure with a characteristic electroencephalographic architecture occurring as follows: (a) an epileptic recruiting rhythm phase; (b) high-frequency spike and polyspike activity, referred to as the polyspike phase; (c) a transition to high-amplitude spike-and–slow-wave activity, known as the slow-wave phase; and (d) a subsequent decrease in the amplitude and/or frequency of the slow waves, culminating in a complete and abrupt postictal suppression (PIS) of bioelectric activity (27, 39–41). With respect to seizure termination, the endpoint may be difficult to determine or may be characterized by suppression ranging from poor, to good but progressive, to the optimal pattern of abrupt PIS (41–43).

Patients were evaluated frequently prior to, around the fourth to sixth sessions, and at the end of the ECT course (RUL vs. BT). Side effects were monitored clinically and by patient report.

Clinical and sociodemographic data (age, sex, diagnosis, illness duration since onset or diagnosis, ECT indication [severity vs. resistance], number of prior hypomanic/manic/depression/psychotic episodes, psychiatric and addictive comorbidities, treatments, current episode duration) and stimulation/seizure outcomes (number of sessions per course, charge, seizure duration, PIS) were extracted from records. Diagnoses were based on DSM-5-TR criteria (44). Δ charge was calculated as the charge difference between first and last session within each ECT course.

Clinical evaluations were conducted by the patients’ referring physicians during hospitalization and assessed both efficacy and tolerability. A categorical assessment of efficacy was performed based on clinicians’ judgment and reflected the response to treatment relative to each patient’s pre-ECT baseline (45). Consistent with prior studies, responses were defined as follows: (a) total response or remission, indicating complete symptom resolution; (b) partial response, reflecting noticeable but insufficient or incomplete clinical improvement with persistent symptoms (i.e., greater than non-response but less than total response); and (c) non-response, defined as no observable clinical improvement (46; 47; 48). Tolerability consisted of assessing the occurrence of side effects (memory disturbance, bradycardia, confusion, and headache). For the purposes of this study, in addition to analyzing each side effect, global tolerability was additionally classified as good when no side effects were reported and poor when one or more side effects occurred during treatment. All these data were documented by physicians in the patients’ medical records.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 30 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) in case of group comparisons and GraphPad Prism 10 (version 10.6.1, Boston, Massachusetts USA) in case of logistic regressions. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. As data were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used. χ² was applied for categorical comparisons (Fisher exact test applied for confirmation when appropriate). First, between-group comparisons were performed between patients who completed only the first ECT course (n=40) and those who switched to a second course (n=18) using the Mann-Whitney test. Second, within-group comparisons between the first and second courses in patients who underwent the switch (n=18) were conducted with the Wilcoxon signed-ranked test. Third, in each ECT course, exploratory supplementary analyses were performed: the study outcomes were compared according to clinical response (total vs. partial vs. non-response; Kruskal-Wallis test) and tolerability (good vs. poor; Mann-Whitney test). Effect sizes were estimated for the Mann–Whitney and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test using r =|Z|/√n and for the Kruskal–Wallis test using E2R=H/[(n2 − 1)/(n + 1)], where Z and H are the respective test statistics and n is the number of observations (49). Given the small sample size, no statistical corrections for multiple comparisons were performed. Finally, logistic regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of switching among variables that differed significantly in group comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive data

The study included 58 patients (62.1% women) with a mean age of 47.8 ± 18.6 years. Mean disease duration was 17.8 ± 14.3 years from symptom onset and 14.5 ± 13.6 years from diagnosis. Diagnoses were 32.7% psychotic episodes (schizophrenia except one patient with a schizoaffective disorder), 44.8% unipolar depression, 13.8% bipolar depression, 6.9% manic episode, and 1.7% catatonia. ECT was indicated for treatment resistance in 70.7% and for severity in 29.2%, with severity due to catatonic features (10.3%), melancholic features (10.3%), or suicidal crisis (8.6%). These data are illustrated in Figure 1. The current episode had lasted 15.6 ± 12.2 weeks at assessment. Patients had experienced a mean of 3.2 ± 3.5 prior depressive episodes, 0.7 ± 2.4 manic episodes, 0.1 ± 1.0 hypomanic episodes, and 1.2 ± 2.6 psychotic episodes. The cumulative number of mood episodes averaged 4.4 ± 4.7 and that of psychiatric episodes 5.6 ± 4.5. Patients reported a mean of 0.3 ± 0.7 psychoactive substances consumptions and 0.4 ± 0.7 psychiatric comorbidities, with the combined addictive and psychiatric comorbidities averaging 0.6 ± 0.7. Psychiatric comorbidities were documented in 19% (obsessive-compulsive disorder 8.6%, eating disorder 8.6%, borderline personality disorder 3.3%, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder 3.3%, autism spectrum disorder 1.7%). Substance consumption was reported in 24.1% (cannabis 5.2%, alcohol 12.1%, cigarettes 13.8%, benzodiazepine 1.7%). Among the initial 58 patients who started a RUL ECT, stimulation was switched to BT due to inadequate clinical response in 18 cases (31.0%).

Figure 1

Illustration of some demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort. BD: Bipolar Disorder; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder. Percentages were rounded, with the smaller category subsequently corrected to achieve a total of 100 %.

The treatment profiles during the first ECT course (n = 58) were as follows: antidepressants (56.9%), antipsychotics (65.5%), clozapine (15.5%), lithium (25.9%), anticonvulsants (13.8%), pramipexole (13.8%), sedative antihistaminic treatments (1.7%) or benzodiazepines (6.9%). Antidepressants categories were as follows: 27.6% specific serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (n=13 venlafaxine and n=3 duloxetine), 22.4% presynaptic α2-adrenoceptor antagonist (mirtazapine), 12.1% specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors (n=4 sertraline, n=2 fluoxetine, n=1 escitalopram), 10.3% vortioxetine, 3.4% tricyclic antidepressants (clomipramine), 3.4% monoamine oxidase inhibitors (n=1 phenelzine, n=1 tranylcypromine), and 1.7% tetracyclic antidepressants (maprotiline).

The treatment profiles during the second ECT course (n = 18) were as follows: antidepressants (50.0%), antipsychotics (66.7%), clozapine (55.6%), lithium (33.3%), anticonvulsants (5.6%), pramipexole (27.8%), sedative antihistaminic treatments (0.0%) or benzodiazepines (0.0%). Antidepressants categories were as follows: 11.1% specific serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (n=1 venlafaxine and n=1 duloxetine), 16.7% presynaptic α2-adrenoceptor antagonist (mirtazapine), 5.6% specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine), 11.1% vortioxetine, 5.6% tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline), and 16.7% monoamine oxidase inhibitors (n=1 phenelzine, n=1 selegiline, n=1 tranylcypromine).

During both ECT courses, no patient received a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (i.e., bupropion).

The number of ECT sessions in the RUL and BT courses were 14.3 ± 7.1 and 14.7 ± 9.7, respectively. The mean charge at the first session was 172.6 ± 99.2 mC for RUL and 152.9 ± 82.3 mC for BT, increasing to 214.4 ± 125.8 mC and 236.2 ± 238.7 mC, respectively, with Δ charge from first to last session being 41.8 ± 76.5 mC and 83.3 ± 187.5 mC, respectively. Seizure durations were as follows: first session (RUL 64.1 ± 32.9 s; BT 63.2 ± 34.7 s) and last session (RUL 47.3 ± 22.1 s; BT 50.9 ± 36.7 s). Abrupt PIS was observed in 60.3% of RUL and 66.7% of BT sessions initially, increasing to 82.8% in RUL and remaining 66.7% in BT by the last session.

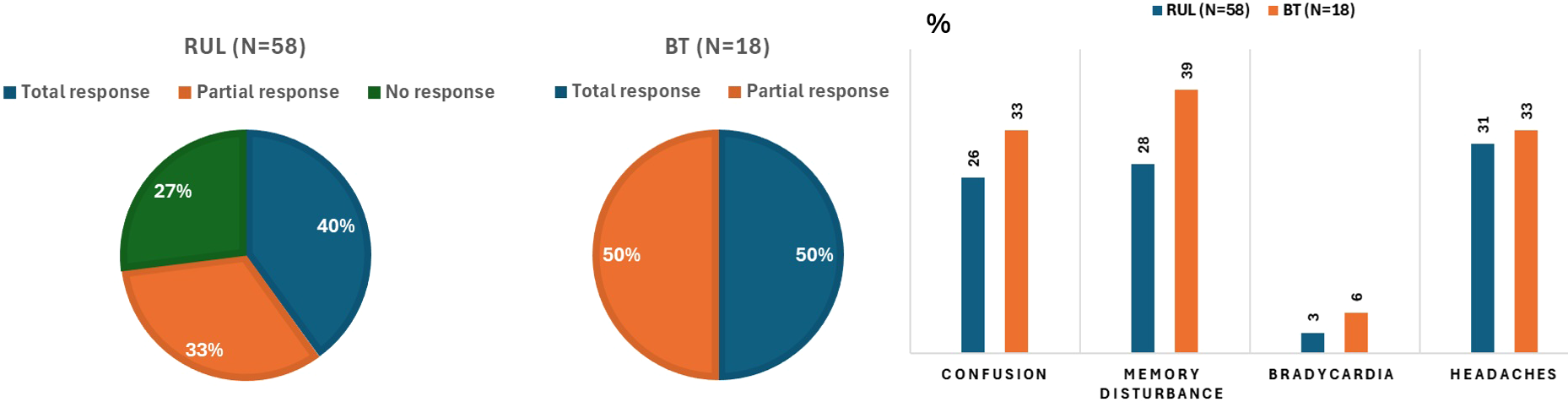

Total clinical response occurred in 39.7% of RUL patients and 50.0% of BT patients, with partial response in 32.8% (RUL) and 50.0% (BT), and no response in 27.6% (RUL) and 0.0% (BT). The cumulative clinical efficacy reached 55.2%. Good tolerability was reported in 50.0% of RUL and 44.4% of BT sessions. Memory disturbance, confusion, and headache were observed in 27.6%, 25.9%, and 31.0% of RUL sessions, and 38.9%, 33.3%, and 33.3% of BT sessions, respectively; bradycardia was rare (RUL 3.4%, BT 5.6%). Efficacy and tolerability data are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Efficacy and tolerability during the right unilateral (RUL) and bitemporal (BT) electroconvulsive therapy courses. Percentages were rounded, with the smaller category subsequently corrected to achieve a total of 100 %.

3.2 Data comparison in the unswitched vs. switched ECT group

The primary analysis pooled diagnostic groups to increase the sample size and improve the statistical power. Given the diagnostic heterogeneity, patterns of response trajectories and tolerability following RUL ECT, and subsequent switching to BT ECT by diagnostic indication category are described in Table 1 for exploratory purposes.

Table 1

| Diagnostic indication category | Clinical response following RUL, n (%) | Good tolerability following RUL, n (%) | Switch RUL→BT, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychotic episode (n=19) | 5 (26.3%) Total response 6 (31.6%) Partial response 8 (42.1%) Non-response |

9 (47.4%) | 8 (42.1%) |

| Major depressive episode (Major depressive disorder) (n=26) | 11 (42.3%) Total response 9 (34.6%) Partial response 6 (23.1%) Non-response |

15 (57.7%) | 8 (30.8%) |

| Major depressive episode (bipolar disorder) (n=8) | 3 (37.5%) Total response 3 (37.5%) Partial response 2 (25.0%) Non-response |

4 (50.0%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| Manic episode (n=4) | 3 (75.0%) Total response 1 (25.0%) Partial response |

1 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Catatonia (n=1) | 1 (100.0%) total response | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Clinical response following right unilateral (RUL) electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and switching to bilateral (BT) ECT by diagnostic indication category.

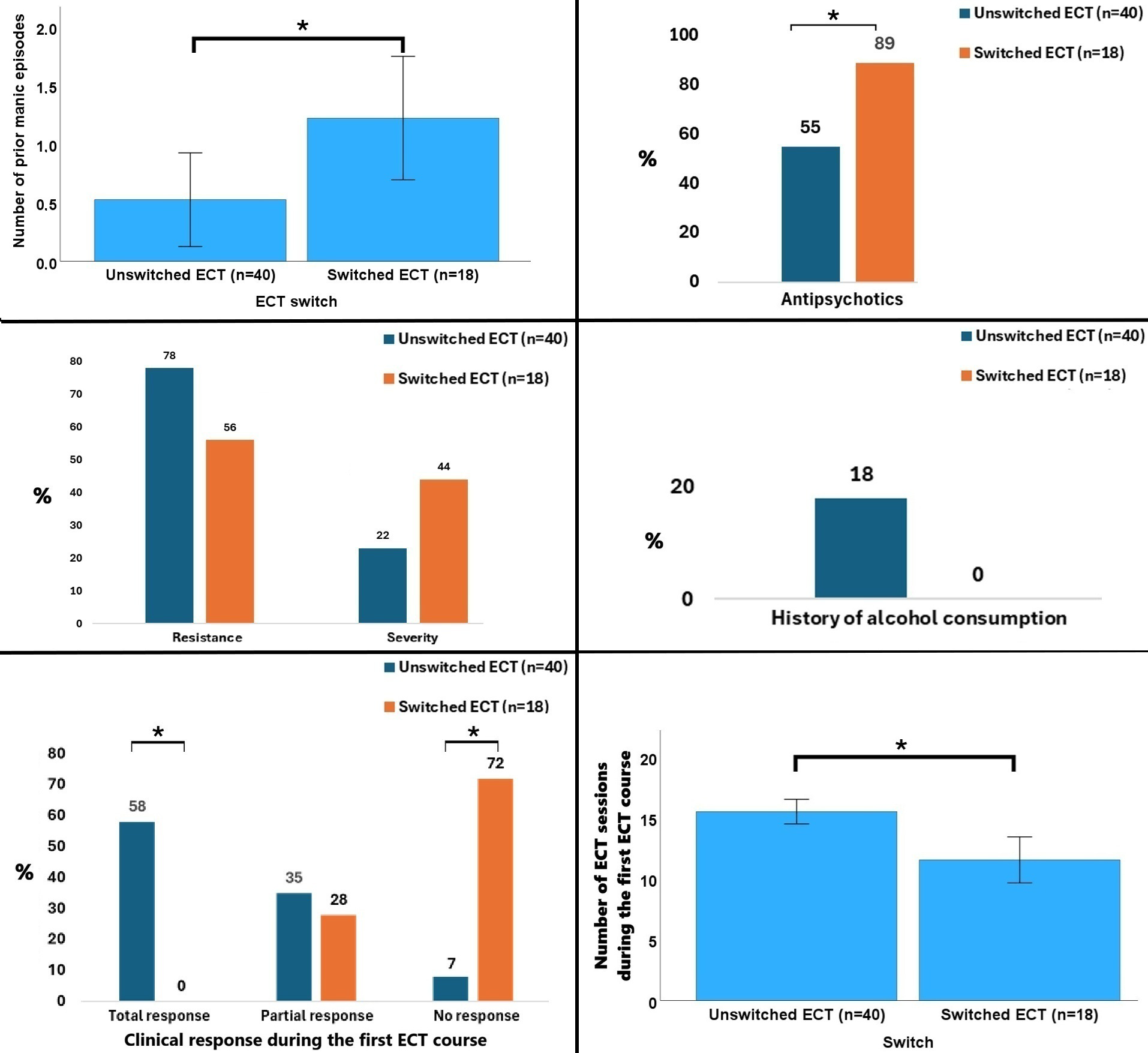

At baseline, patients who switched to the BT ECT (n = 18) had more previous manic episodes (1.2 ± 2.2 vs. 0.5 ± 2.5; p = 0.021, effect size r = 0.30) and higher antipsychotic use during RUL ECT (88.9% vs. 55.0%; p = 0.012) compared to those who pursued RUL ECT (n = 40). There was also a tendency toward higher frequency of ECT indication for severity (44.4% vs. 22.5%; p=0.089), lower frequency of ECT indication for resistance (55.6% vs. 77.5%; p = 0.089), and lower alcohol use (0.0% vs. 17.5%; p = 0.058) in the switched group. The only significant procedural difference was the number of sessions: patients who completed RUL ECT received on average 15.5 ± 6.4 sessions, whereas patients who switched to BT ECT completed 11.6 ± 8.0 sessions using the RUL setup before switching (p = 0.029, effect size r = 0.29). Regarding clinical outcomes, there were significant group differences in clinical efficacy during the first ECT course (p<0.001), with total response being significantly and exclusively observed in the unswitched group (57.5% vs. 0.0%, post hoc p<0.05) whereas non-response being significantly observed in the group who subsequently underwent the switch (7.5% vs. 72.2%, post hoc p<0.05) (Figure 3). This occurred in the lack of significant group differences in terms of sociodemographic variables, remaining clinical, stimulation/seizure and ECT-outcomes (tolerability during the RUL course, globally or individual side effects). All the data are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 3

Data that significantly differed or tended to differ between patients who remained in the right unilateral treatment vs. those switched to bitemporal treatment. *p<0.05. Percentages were rounded, with the smaller category subsequently corrected to achieve a total of 100 %.

Table 2

| Variable | RUL (n=40) | RUL→BT (n=18) | χ²/U | P | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.0 ± 20.8 | 45.1 ± 12.5 | U = 339.00 | 0.724 | 0.05 |

| Sex (females), n (%) | 24 (60.0%) | 12 (66.7%) | χ² = 0.23 | 0.628 | – |

| Diagnostic categories, n (%) | 11 (27.5%) Psychotic episode 18 (45.0%) Unipolar depression 6 (15.0%) Bipolar depression 4 (10.0%) Manic episode 1 (2.5%) Catatonia |

8 (44.4%) Psychotic episode 8 (44.4%) Unipolar depression 2 (11.1%) Bipolar depression 0 (0.0%) Manic episode 0 (0.0%) Catatonia |

χ² = 3.48 | 0.482 | – |

| Indication for ECT, n (%) | 31 (77.5%) Resistance 9 (22.5%) Severity |

10 (55.6%) Resistance 8 (44.4%) Severity |

χ² = 2.89 | 0.089 | – |

| Disease duration since first symptoms (years) | 17.7 ± 13.9 | 18.1 ± 15.3 | U = 357.50 | 0.966 | 0.01 |

| Duration of illness since diagnosis (years) | 14.5 ± 13.4 | 14.6 ± 14.5 | U = 351.50 | 0.886 | 0.02 |

| Duration of current episode (weeks) | 14.4 ± 12.1 | 18.3 ± 12.4 | U = 426.00 | 0.266 | 0.15 |

| Previous depressive episodes | 3.5 ± 3.6 | 2.7 ± 3.4 | U = 301.00 | 0.311 | 0.13 |

| Previous manic episodes | 0.5 ± 2.5 | 1.2 ± 2.2 | U = 438.00 | 0.021 | 0.30 |

| Previous hypomanic episodes | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | U = 326.50 | 0.392 | 0.11 |

| Previous psychotic episodes | 1.2 ± 2.6 | 1.1 ± 2.7 | U = 359.00 | 0.983 | 0.00 |

| Cumulative mood/psychotic episodes | 5.7 ± 4.5 | 5.2 ± 4.6 | U = 349.00 | 0.692 | 0.05 |

| Number of psychiatric and addictive comorbidities | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | U = 364.00 | 0.940 | 0.01 |

| Any psychiatric comorbidities, n (%) | 6 (15.0%) | 5 (27.8%) | χ² = 1.32 | 0.251 | – |

| Eating disorders, n (%) | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (11.1%) | χ² = 0.21 | 0.650 | – |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder, n (%) | 4 (10.0%) | 1 (5.6%) | χ² = 0.31 | 0.577 | – |

| Any substance consumption, n (%) | 11 (27.5%) | 3 (16.7%) | χ² = 0.80 | 0.372 | – |

| Cannabis consumption, n (%) | 2 (5.0%) | 1 (5.6%) | χ² = 0.01 | 0.930 | – |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 7 (17.5%) | 0 (0%) | χ² = 3.58 | 0.058 | – |

| Smoking consumption, n (%) | 6 (15%) | 2 (11.1%) | χ² = 0.16 | 0.691 | – |

| Antipsychotics, n (%) | 22 (55.0%) | 16 (88.9%) | χ² = 6.31 | 0.012 | - |

| Clozapine, n (%) | 7 (17.5%) | 2 (11.1%) | χ² = 0.39 | 0.534 | – |

| Antidepressants, n (%) | 23 (57.5%) | 10 (55.6%) | χ² = 0.02 | 0.890 | – |

| Lithium, n (%) | 11 (27.5%) | 4 (22.2%) | χ² = 0.18 | 0.671 | – |

| Anticonvulsants, n (%) | 6 (15.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | χ² = 0.16 | 0.691 | – |

| Pramipexole, n (%) | 6 (15.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | χ² = 0.16 | 0.691 | – |

| Sedative antihistaminic treatments, n (%) | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | χ² = 0.46 | 0.499 | – |

| Benzodiazepines, n (%) | 3 (7.5%) | 1 (5.6%) | χ² = 0.07 | 0.787 | – |

| Total number of sessions (number) | 15.5 ± 6.4 | 11.6 ± 8.0 | U = 230.00 | 0.029 | 0.29 |

| Δ charge first-last sessions (mC) | 40.5 ± 60.2 | 44.6 ± 106.4 | U = 300.50 | 0.302 | 0.14 |

| Charge first session (mC) | 181.0 ± 111.4 | 154.1 ± 63.3 | U = 310.50 | 0.382 | 0.11 |

| Charge last session (mC) | 221.5 ± 121.3 | 198.7 ± 137.7 | U = 286.00 | 0.206 | 0.17 |

| Seizure duration first session (s) | 61.3 ± 31.8 | 70.2 ± 35.4 | U = 427.00 | 0.260 | 0.15 |

| Seizure duration last session (s) | 46.7 ± 20.1 | 48.7 ± 26.4 | U = 374.50 | 0.807 | 0.03 |

| Postictal suppression first session, n (%) | 22 (55.0%) | 13 (72.2%) | χ² = 1.54 | 0.215 | – |

| Postictal suppression last session, n (%) | 35 (87.5%) | 13 (72.2%) | χ² = 2.03 | 0.154 | – |

| Clinical efficacy, n (%) | 23 (57.5%) Total response* 14 (35.0%) Partial response 3 (7.5%) Non-response* |

0 (0%) Total response* 5 (27.8%) Partial response 13 (72.2%) Non-response* |

χ² = 29.40 | <0.001 | - |

| Good tolerability, n (%) | 21 (52.5%) | 8 (44.4%) | χ² = 0.32 | 0.570 | – |

| Memory disturbance, n (%) | 11 (27.5%) | 5 (27.8%) | χ² = 0.00 | 0.983 | – |

| Post-ictal confusion, n (%) | 12 (30.0%) | 3 (16.7%) | χ² = 1.15 | 0.283 | – |

| Headache, n (%) | 13 (32.5%) | 5 (27.8%) | χ² = 0.13 | 0.719 | – |

| Bradycardia during the session, n (%) | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (5.6%) | χ² = 0.35 | 0.555 | – |

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, clinical outcomes and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) variables of the first ECT course in patients continuing right unilateral (RUL) ECT versus those switched to bitemporal (BT) ECT. .

Significant p values are bolded. *p< 0.05 in post-hoc tests.

Binary logistic regression was conducted to examine the association between some baseline clinical and sociodemographic variables (independent variables) and the likelihood of switching from RUL to BT ECT (dependent variable: switch yes/no). Only baseline variables that differed significantly in group comparisons were entered into the model, namely the number of previous manic episodes and the frequency of antipsychotic use. The best regression model retained only the frequency of antipsychotic use and was statistically significant, χ² (1, N = 58) = 7.12, p = 0.008. This model explained 16.3% of the variance in switching (Nagelkerke R²) and correctly classified 69.0% of cases. Patients receiving antipsychotic medication were significantly more likely to be switched from RUL to BT ECT than those not receiving antipsychotics (OR = 6.55, 95% CI [1.58, 44.94]). The number of previous manic episodes was not a significant predictor of the switching strategy.

3.3 Data comparison in the switched group during the right unilateral vs. bitemporal course

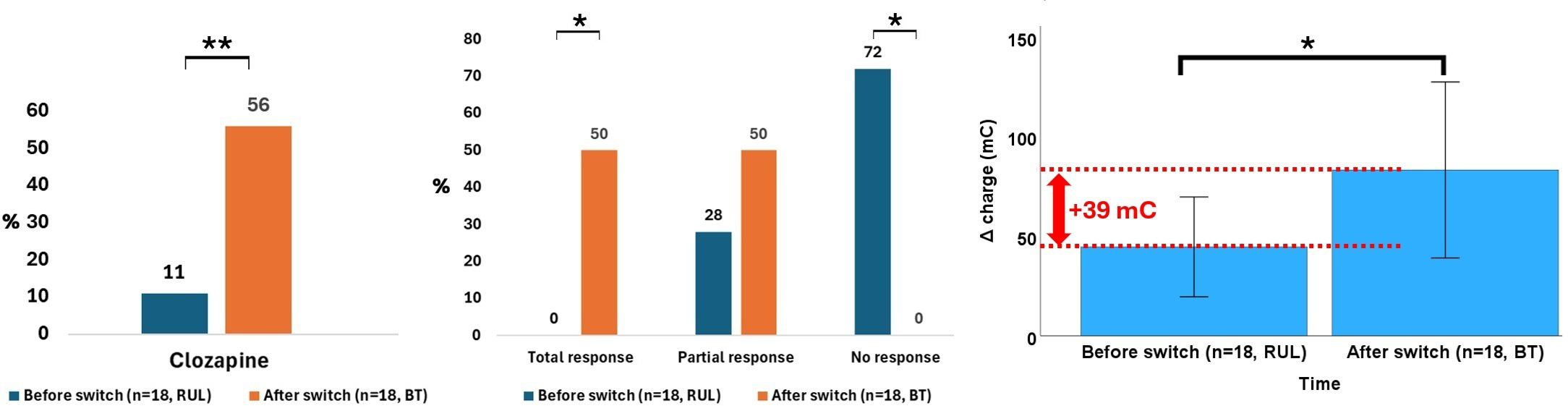

In the subgroup of patients who underwent both RUL and BT stimulation (n = 18), the Δ charge was significantly greater during BT (+ 38.7 mC, p = 0.049, effect size r = 0.46), in the absence of significant differences in the number of ECT sessions, seizure duration at the first or last session, PIS abruptness at either session, or charge at the first or last session. Regarding treatments, clozapine use increased by + 44.5% from the RUL to the BT course (p = 0.005), while other medication did not. A significant difference in efficacy emerged (p < 0.001): Total response occurred only during BT course (50.0% vs. 0.0%, post hoc p < 0.05), while non-response occurred only during RUL course (72.2% vs. 0.0%, post hoc p < 0.05). Tolerability was comparable (p > 0.999), with nonsignificant increases in confusion (+16.7%, p = 0.248), memory disturbance (+11.3%, p = 0.480), and headaches (+5.5%, p = 0.717), and no change in bradycardia (p > 0.999). The main findings are illustrated in Figure 4. The whole results of this analysis are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 4

Data that significantly differed in patients who underwent a switch from right unilateral (RUL) to bitemporal (BT) electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Table 3

| Variables | RUL ECT course (n=18) | BT ECT course (n=18) | χ²/W | P | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics, n (%) | 16 (88.9%) | 12 (66.7%) | χ² = 2.57 | 0.109 | – |

| Clozapine, n (%) | 2 (11.1%) | 10 (55.6%) | χ² = 8.00 | 0.005 | - |

| Antidepressants, n (%) | 10 (55.6%) | 9 (50.0%) | χ² = 0.11 | 0.738 | – |

| Lithium, n (%) | 4 (22.2%) | 6 (33.3%) | χ² = 0.55 | 0.457 | – |

| Anticonvulsants, n (%) | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (5.6%) | χ² = 0.36 | 0.546 | – |

| Pramipexole, n (%) | 2 (11.1%) | 5 (27.8%) | χ² = 1.60 | 0.206 | – |

| Antihistaminic, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | – | – |

| Benzodiazepines, n (%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | χ² = 1.03 | 0.310 | – |

| Total number of sessions (number) | 11.6 ± 8.0 | 14.7 ± 9.7 | W = 93.50 | 0.421 | 0.19 |

| Δ charge first-last sessions (mC) | 44.6 ± 106.4 | 83.3 ± 187.5 | W = 106.00 | 0.049 | 0.46 |

| Charge first session (mC) | 154.1 ± 63.3 | 152.9 ± 82.3 | W = 64.00 | 0.553 | 0.14 |

| Charge last session (mC) | 198.7 ± 137.7 | 236.2 ± 238.7 | W = 93.50 | 0.421 | 0.19 |

| Seizure duration first session (s) | 70.2 ± 35.4 | 63.2 ± 34.7 | W = 74.00 | 0.616 | 0.12 |

| Seizure duration last session (s) | 48.7 ± 26.4 | 50.9 ± 36.7 | W = 73.50 | 0.887 | 0.04 |

| Postictal suppression first session, n (%) | 13 (72.2%) | 12 (66.7%) | χ² = 0.13 | 0.717 | – |

| Postictal suppression last session, n (%) | 13 (72.2%) | 12 (66.7%) | χ² = 0.13 | 0.717 | – |

| Clinical efficacy, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) Total response* 5 (27.8%) Partial response 13 (72.2%) Non-response* |

9 (50.0%) Total response* 9 (50.0%) Partial response 0 (0.0%) Non-response* |

χ² = 23.14 | <0.001 | - |

| Good tolerability, n (%) | 8 (44.4%) | 8 (44.4%) | χ² = 0.00 | >0.999 | – |

| Memory disturbance, n (%) | 5 (27.8%) | 7 (38.9%) | χ² = 0.50 | 0.480 | – |

| Post-ictal confusion, n (%) | 3 (16.7%) | 6 (33.3%) | χ² = 1.33 | 0.248 | – |

| Headache, n (%) | 5 (27.8%) | 6 (33.3%) | χ² = 0.13 | 0.717 | – |

| Bradycardia during the session, n (%) | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (5.6%) | χ² = 0.00 | >0.999 | – |

Clinical characteristics, clinical outcomes and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) variables of the patients who underwent a switch from right unilateral (RUL) ECT to bitemporal (BT) ECT.

Significant p values are bolded. *p< 0.05 in post-hoc tests.

3.4 Supplementary analysis of efficacy and tolerability in each time course

Following the RUL ECT course, the number of prior manic episodes differed significantly across efficacy groups (p = 0.022, effect size E2R = 0.13). Post hoc analysis showed that non-responders had a higher number of prior manic episodes compared to partial responders (1.4 ± 2.3 vs. 0.0 ± 0.0, p = 0.020), while no differences emerged between total responders and either group. Patients with good tolerability during RUL ECT were older (53.6 ± 17.5 vs. 42.0 ± 18.1, p = 0.013, effect size r = 0.32), had longer disease duration since first symptoms (21.8 ± 14.9 vs. 13.8 ± 12.6, p = 0.031, effect size r = 0.28) and since diagnosis (17.5 ± 14.6 vs. 11.5 ± 12.1, p = 0.042, effect size r = 0.27), and had experienced more prior depressive episodes (4.4 ± 4.2 vs. 2.1 ± 2.2, p = 0.037, effect size r = 0.27) and psychiatric episodes overall (6.7 ± 4.6 vs. 4.4 ± 4.2, p = 0.028, effect size r = 0.29). Following the BT ECT course, no significant differences were observed among efficacy groups, although clozapine intake tended to be lower in total responders than partial responders (33.3% vs. 77.8%, p = 0.058). Better tolerability during BT ECT was associated with the absence of psychiatric comorbidities, both in frequency (0.0% vs. 50.0%, p = 0.019) and number (0.0 ± 0.0 vs. 0.8 ± 0.9, p = 0.083, effect size r = 0.53).

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of findings

This retrospective study examined clinical outcomes and switching strategies in titrated ECT with an initial RUL course followed by BT course in cases of insufficient response in a French cohort of adults with psychiatric disorders. About one-third of patients required a switch, with overall efficacy rates around 40% after RUL ECT and exceeding 50% when both courses were considered, while tolerability remained comparable despite a greater charge increase during BT ECT. Compared to patients who completed RUL ECT alone, those requiring BT ECT were more likely to have a history of manic episodes and to receive antipsychotic treatments, with trends toward greater severity, lower treatment resistance, and less alcohol use. Among switched patients, BT ECT was associated with a higher Δ charge and more frequent clozapine prescription. Additional analyses suggested that older age, longer illness duration, and more prior depressive episodes were associated with better tolerability in RUL, while fewer psychiatric comorbidities were associated with better tolerability in BT ECT. Regarding efficacy, fewer prior manic episodes differentiated partial from non-responders in RUL ECT, and lower clozapine prescription was found in total compared to partial responders in BT ECT.

4.2 Between-group comparison: patients completing RUL vs. patients switching to BT ECT

The switched group had a higher number of previous manic episodes, greater antipsychotic use, and a tendency toward ECT initiation for symptom severity rather than treatment resistance. Antipsychotic use was a significant predictor of switching from RUL to BT ECT. These findings highlight potential clinical factors associated with poorer RUL efficacy. While high-dose RUL ECT can sometimes approach the efficacy of BT ECT (2, 5, 8), our findings support the notion that patients with more severe or complex illness trajectories may benefit less from cognitive-sparing strategies and may ultimately require BT placement. Reviews and meta-analyses suggest that although high-dose RUL can approximate BT ECT efficacy, its effectiveness is limited in certain subgroups of patients (50; CANMAT, 1, 13). BT stimulation may achieve faster or more robust responses, whereas some patients undergoing RUL ECT experience slower or lower efficacy (1, 5–15). Consistently, in our cohort, non-responders to RUL were successfully rescued with BT stimulation. Earlier studies have linked treatment resistance to poorer ECT outcomes (51–53), and recent trials show that RUL-to-BT switching occurs more often in highly resistant patients who also seem to require more sessions (32). These findings support earlier ECT intervention in less resistant patients to reduce treatment burden and limit the need for BT switching, thereby minimizing cognitive side effects. Conversely, in one of their sequential ECT studies, Sackeim and colleagues suggest that efficacy improvements in initial non-responders may stem from prolonging treatment rather than electrode switching to a bilateral setup, since their patients improved regardless of the first ECT course (unilateral or bilateral) (4). Further, their second BT course was associated with more pronounced cognitive symptoms, highlighting the need for randomized trials to clarify the relative contributions of extended treatment versus electrode placement (4).

From a mechanistic perspective, differences in RUL and BT ECT efficacy may reflect distinct neurobiological mechanisms. Bilateral ECT could induce a stronger activation of diencephalic, hypothalamic, and prefrontal networks, which are implicated in regulating vegetative and mood symptoms (54–56), and may produce higher charge density in these regions as well as more symmetric cortical seizure patterns compared to RUL (57–59). High dose RUL can recruit broader cortical regions compared to a low dose regimen, thereby approximating the effects of bilateral electrode placement (60–64).

Interestingly, and somewhat counterintuitively, patients who required a switch in our study tended to have a lower prevalence of alcohol use compared to those who continued RUL ECT. Evidence linking substance use to ECT outcomes is limited and mixed. Some studies suggest a history of alcohol use may be associated with a better clinical response in patients with MDD or schizophrenia, potentially via modulation of the glutamatergic-GABAergic (excitatory–inhibitory) balance (65, 66), whereas others report poorer or unchanged outcomes in patients with mood disorders and comorbid alcohol or substance use disorders (67–69). In our inpatient setting, this finding could be an artifact of abstinence from alcohol, which may have partly contributed to clinical improvement and potentially reduced the need to switch to BT ECT. This was described in previous work with adolescents and young adults with depression (70).

4.3 Within-group comparison: RUL vs. BT ECT courses in patients who underwent switch

The within-patient comparison in the switched subgroup highlights the clinical value of BT ECT in initially refractory cases, with remission occurring exclusively during the BT course in half of these patients, whereas non-response was confined to the RUL course. This underscores the utility of sequential strategies to maximize efficacy while limiting exposure to the higher cognitive risks of BT. Although seizure quality and session numbers did not differ significantly, BT ECT was associated with greater Δ charge and increased clozapine use, reflecting the pharmacological complexity and severity of cases requiring optimization of neuromodulation and pharmacological protocols to achieve a clinical response. Clozapine, a marker of treatment refractoriness, illustrates the multimodal approach of combining neurostimulation and pharmacotherapy, consistent with guideline recommendations (71). Its higher use in patients undergoing BT ECT may reflect an augmentation strategy aimed at optimizing treatment outcomes.

4.4 Supplementary analysis: comparing outcomes according to efficacy and tolerability

Supplementary analyses identified clinical factors associated with ECT outcomes. However, these findings are exploratory and should be interpreted with caution. Efficacy was associated with a lower number of prior manic episodes in the RUL course, and with lower clozapine prescription in the BT course. Fewer prior manic episodes may indicate predominantly depressive illness, reflecting less severe or even less resistant disease. Similarly, clozapine prescription may reflect disease severity and treatment resistance, and the observed association should be interpreted with caution; it likely reflects a bias due to confounding by indication rather than a causal effect of the medication on ECT outcomes. As such, patients with more severe or resistant illnesses are more likely to receive clozapine. Prior studies have identified predictors of good ECT response in depression, including short episode duration (31, 72–78), absence of chronic depression or dysthymia (73), preserved insight (74), low pharmacological resistance (32, 73, 75, 77, 79), low disability burden (80), and absence of psychiatric comorbidities (79, 80). Evidence regarding bipolar depression is mixed, with efficacy reported as higher (30, 31, 79, 81), lower (74, 82), or comparable (30, 83, 84) to unipolar depression. Some studies suggest bipolar depression responds more rapidly (83, 85–87) and may require fewer sessions (30, 85, 88). Baseline symptom severity shows inconsistent associations with response (29, 77, 80, 82, 84, 89). Additional clinical correlates include psychomotor symptoms (76, 78, 90, 91), which may underlie the association between older age and efficacy in unipolar depression (76, 90), and psychotic features, generally associated with better outcomes (77, 78, 90; for reviews see 28; meta-analysis by 29) though not consistently (74, 75). Evidence regarding melancholic features is mixed (28, 29, 75). High severity of suicidality has also been highlighted as a predictor of good response (for reviews see 28). Regarding age, several studies and reviews have reported a positive association between age and ECT efficacy (28, 31, 69, 73, 78, 79, 84, 92, 93; meta-analysis by 29), whereas others found no effect (75, 76). Beyond efficacy, controversial findings concern cognitive outcomes: older adults were reported to be less likely to experience cognitive decline and more likely to exhibit cognitive improvement following ECT compared with younger patients (94). However, older age was also associated with higher rates of transient cardiac arrhythmia during treatment (93, 95), and in other studies, it was associated with more cognitive side effects (95, 96).

Tolerability during the RUL course was associated with older age, longer illness duration and a higher recurrence rate of psychiatric episodes. This latter finding may reflect the familiarity with and acceptance of psychiatric interventions, consistent with evidence on the influence of patients’ expectations on ECT outcomes (97). Repeated exposure to interventions throughout a chronic illness could mitigate anxiety and uncertainty, enabling patients to approach ECT with greater composure. Moreover, individuals with more severe or recurrent illness may perceive ECT as necessary and effective, which may further enhance tolerability. During the BT course, tolerability was higher in patients with fewer psychiatric comorbidities, suggesting that clinical complexity contributes not only to treatment resistance but also to vulnerability to side effects. Supporting this, patients with comorbid personality disorders or traits have been reported to show higher rates of side effects and relapse following ECT compared with those without such comorbidities (98). Additionally, polypharmacy - common among patients with multiple comorbidities - may further increase the risk of adverse reactions.

4.5 Study strengths, limitations, and future perspectives

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size - particularly in the switched group - may have reduced statistical power and may limit the generalizability of the findings. For the same reason, despite the numerous outcomes assessed, no statistical correction for multiple testing was applied, which may increase the risk of type I error (i.e., false positives). Similarly, stratified analyses were not conducted. Second, the absence of long-term follow-up prevents conclusions regarding relapse risk and remission durability. Third, outcomes relied on chart reviews without systematic neuropsychological, neuroimaging, or neurophysiological assessments. The absence of validated symptom severity scales to characterize the study cohort (e.g., Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for depression, Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale for schizophrenia) limits the comparability of the present findings with previous studies. Additionally, clinical efficacy was categorized based on treating clinicians’ judgment which may introduce inter-rater variability and may carry potential misclassification risk inherent to chart-based categorical outcomes. Assessments were also performed by the treating clinicians rather than independently, reflecting real-world practice but potentially introducing another source of bias. In addition, symptom dimensions were not analyzed, although some work suggests specific symptom domains predict ECT response in depression (99, 100). Moreover, these limitations also apply to tolerability, which was dichotomized based on subjective complaints or clinician assessment rather than graded by severity using standardized tools (e.g., neuropsychological testing for cognitive side effects such as the ElectroConvulsive therapy Cognitive Assessment tool; 101). This approach may have obscured clinically meaningful differences in the severity or persistence of side effects. Furthermore, concerning the seizure quality induced by ECT, despite regular training and supervision to ensure EEG readings are standardized, clinician bias cannot be entirely excluded. Future research would benefit from incorporating standardized, validated rating instruments and independent evaluations to improve reliability and comparability.

The current findings underscore the need for multimodal approaches integrating clinical, biological, neurophysiological and neuroimaging predictors to improve patient stratification and guide personalized ECT strategies in large, prospective, controlled cohorts with a long-term follow-up. Increasing interest in biological predictors includes microRNA signatures linked to inflammatory pathways (102), baseline inflammatory markers (103), and kynurenine pathway metabolites (104). Other promising markers involve brain functional connectivity patterns or metabolites, plasma homovanillic acid and Tumor necrosis factor-α, and specific genetic polymorphisms (28, 105), although current methods remain below translational thresholds.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Treatment procedures followed international ECT guidelines. Patients and/or their legal representatives gave informed consent before ECT initiation. Data collected during routine care were retrospectively reviewed and anonymized. This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Author contributions

ES: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Investigation, Writing – original draft. LF: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. FP: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MA: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. PDM: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. RG: Validation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Validation. FV: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CS: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. FT: Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Writing – original draft. PD: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MC: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients who took part in this work, Karim Benhamada (ECT coordinator nurse), the referring physicians, the anesthesia and INM team, and the editor and reviewers who helped improve the quality of this article.

Conflict of interest

RG has received compensation as a member of the scientific advisory board of Janssen, Lundbeck, Roche, SOBI, and Takeda. He has served as a consultant and/or speaker for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pierre Fabre, Lilly, Lundbeck, LVMH, MAPREG, Novartis, Otsuka, Pileje, SANOFI, and Servier and received compensation. He has also received research support from Servier. None of these interests are related to this work. FV has been invited to scientific meetings, consulted and/or served as a speaker, and received compensation from Lundbeck, Servier, Recordati, Janssen, Otsuka, LivaNova, and Chiesi. He has received research support from Lundbeck. PD reports a relationship with LivaNova PLC, Janssen and Biopharma that includes: speaking and lecture fees and travel reimbursements, as well as consulting fees for Boston Scientific. PD holds warrants from Callyope®. MC declares having received compensation from Janssen, Exoneural Network AB, and Ottobock.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author MC declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Lam RW Kennedy SH Adams C Bahji A Beaulieu S Bhat V et al . Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 update on clinical guidelines for management of major depressive disorder in adults. Can J Psychiatry. (2024) 69:641–87. doi: 10.1177/07067437241245384

2

Zrelli M Souabni K De Maricourt P Amagat M Gaillard R Smadja S et al . Evolving electroconvulsive therapy practices at a French psychiatric hospital: a retrospective analysis. L’Encephale. (2025) S0013-7006(25)00194-0. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2025.09.007

3

Gazdag G Ungvari GS . Electroconvulsive therapy: 80 years old and still going strong. World J Psychiatry. (2019) 9:1–6. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v9.i1.1

4

Sackeim HA Prudic J Devanand DP Nobler MS Haskett RF Mulsant BH et al . The benefits and costs of changing treatment technique in electroconvulsive therapy due to insufficient improvement of a major depressive episode. Brain Stimul. (2020) 13:1284–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.06.016

5

Sackeim HA Prudic J Devanand DP Nobler MS Lisanby SH Peyser S et al . A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bilateral and right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at different stimulus intensities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2000) 57:425–34. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.425

6

Sackeim HA Prudic J Fuller R Keilp J Lavori PW Olfson M . The cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy in community settings. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2007) 32:244–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301180

7

Sackeim HA Prudic J Nobler MS Fitzsimons L Lisanby SH Payne N et al . Effects of pulse width and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. Brain Stimul. (2008) 1:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.03.001

8

Sackeim HA Dillingham EM Prudic J Cooper T McCall WV Rosenquist P et al . Effect of concomitant pharmacotherapy on electroconvulsive therapy outcomes: short-term efficacy and adverse effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2009) 66:729–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.75

9

Lisanby SH Maddox JH Prudic J Devanand DP Sackeim HA . The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2000) 57:581–90. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.581

10

McCall WV Dunn A Rosenquist PB Hughes D . Markedly suprathreshold right unilateral ECT versus minimally suprathreshold bilateral ECT: antidepressant and memory effects. J ECT. (2002) 18:126–9. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200209000-00003

11

Tew JD Mulsant BH Haskett RF Dolata D Hixson L Mann JJ . A randomized comparison of high-charge right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy and bilateral electroconvulsive therapy in older depressed patients who failed to respond to 5 to 8 moderate-charge right unilateral treatments. J Clin Psychiatry. (2002) 63:1102–5. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v63n1203

12

Perera TD Luber B Nobler MS Prudic J Anderson C Sackeim HA . Seizure expression during electroconvulsive therapy: relationships with clinical outcome and cognitive side effects. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2004) 29:813–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300377

13

Kellner CH Tobias KG Wiegand J . Electrode placement in electroconvulsive therapy: a review of the literature. J ECT. (2010) 26:175–80. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181e48154

14

Fink M . What was learned: studies by the consortium for research in ECT (CORE) 1997-2011. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2014) 129:417–26. doi: 10.1111/acps.12251

15

Su L Jia Y Liang S Shi S Mellor D Xu Y . Multicenter randomized controlled trial of bifrontal, bitemporal, and right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2019) 73:636–41. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12907

16

Sackeim H Decina P Prohovnik I Malitz S . Seizure threshold in electroconvulsive therapy: effects of sex, age, electrode placement, and number of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1987) 44:355–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800160067009

17

Loo CK Sainsbury K Sheehan P Lyndon B . A comparison of RUL ultrabrief pulse (0.3 ms) ECT and standard RUL ECT. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2008) 11:883–90. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009292

18

Mayur P Byth K Harris A . Autobiographical and subjective memory with right unilateral high-dose 0.3-millisecond ultrabrief-pulse and 1-millisecond brief-pulse electroconvulsive therapy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J ECT. (2013) 29:277–82. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3182941baf

19

Loo CK Katalinic N Smith DJ Ingram A Dowling N Martin D et al . A randomized controlled trial of brief and ultrabrief pulse right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2014) 18:pyu045. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu045

20

Tor PC Bautovich A Wang MJ Martin D Harvey SB Loo C . A systematic review and meta-analysis of brief versus ultrabrief right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for depression. J Clin Psychiatry. (2015) 76:e1092–1098. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14r09145

21

Martin DM Bakir AA Lin F Francis-Taylor R Alduraywish A Bai S et al . Effects of modifying the electrode placement and pulse width on cognitive side effects with unilateral ECT: a pilot randomized controlled study with computational modelling. Brain Stimul. (2021) 14:1489–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2021.09.014

22

Sackeim HA . Modern electroconvulsive therapy: vastly improved yet greatly underused. JAMA Psychiatry. (2017) 74:779–80. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1670

23

Abrams R Taylor MA Faber R Ts'o TO Williams RA Almy G . Bilateral versus unilateral electroconvulsive therapy: efficacy in melancholia. Am J Psychiatry. (1983) 140:463–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.4.463

24

Eda M Matsuki R . When to switch from bilateral to unilateral electroconvulsive therapy: a simple way to elicit seizures in high seizure threshold cases. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. (2019) 39:36–40. doi: 10.1002/npr2.12039

25

Wada K Masuda Y Itagaki K Fujii A Ishikawa R Sangawa H et al . Effectiveness of switching to right unilateral from bilateral stimulation in patients with inadequate seizures during acute electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. (2025) 41:89–92. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000001051

26

Lemasson M Rochette L Galvão F Poulet E Lacroix A Lecompte M et al . Pertinence of titration and age-based dosing methods for electroconvulsive therapy: an international retrospective multicenter study. J ECT. (2018) 34:220–6. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000508

27

Nobler MS Sackeim HA Solomou M Luber B Devanand DP Prudic J . EEG manifestations during ECT: effects of electrode placement and stimulus intensity. Biol Psychiatry. (1993) 34:321–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90089-V

28

Pinna M Manchia M Oppo R Scano F Pillai G Loche AP et al . Clinical and biological predictors of response to electroconvulsive therapy: a review. Neurosci Lett. (2018) 669:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.10.047

29

van Diermen L van den Ameele S Kamperman AM Sabbe BCG Vermeulen T Schrijvers D et al . Prediction of electroconvulsive therapy response and remission in major depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. (2018) 212:71–80. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2017.28

30

Bahji A Hawken ER Sepehry AA Cabrera CA Vazquez G . ECT beyond unipolar major depression: systematic review and meta-analysis of electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2019) 139:214–26. doi: 10.1111/acps.12994

31

Gurel SC Mutlu E Başar K Yazıcı MK . Bi-temporal electroconvulsive therapy efficacy in bipolar and unipolar depression: a retrospective comparison. Asian J Psychiatr. (2021) 55:102503. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102503

32

Rovers JJE Vissers P Loef D van Waarde JA Verdijk JPAJ Broekman BFP et al . The impact of treatment resistance on outcome and course of electroconvulsive therapy in major depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2023) 147:570–80. doi: 10.1111/acps.13550

33

Salik I Marwaha R . Electroconvulsive Therapy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. (2022).

34

Rasmussen K . The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging (second edition). J ECT. (2002) 18:58–9. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200203000-00015

35

Penland HR Ostroff RB . Combined use of lamotrigine and electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar depression: a case series. J ECT. (2006) 22:142–7. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200606000-00013

36

Sienaert P Roelens Y Demunter H Vansteelandt K Peuskens J Van Heeringen C . Concurrent use of lamotrigine and electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. (2011) 27:148–52. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181e63318

37

Zolezzi M . Medication management during electroconvulsant therapy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2016) 12:931–9. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S100908

38

Quiles C Dewitte A Thomas P Nunes F Verdoux H Amad A . Electroconvulsive therapy in combination with psychotropic and non-psychotropic pharmacological treatments: review of the literature and practical recommendations. Encephale. (2020) 46:283–92. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.01.002

39

Nobler MS Luber B Moeller JR Katzman GP Prudic J Devanand DP et al . Quantitative EEG during seizures induced by electroconvulsive therapy: relations to treatment modality and clinical features. I. Global analyses. J ECT. (2000) 16:211–28. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200009000-00002

40

American Psychiatric Association . The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2001).

41

Azuma H Fujita A Otsuki K Nakano Y Kamao T Nakamura C et al . Ictal electroencephalographic correlates of posttreatment neuropsychological changes in electroconvulsive therapy: a hypothesis-generation study. J ECT. (2007) 23:163–8. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31807a2a94

42

Weiner RD Krystal AD . EEG monitoring and manage mentofelectrically induced seizures. In: CoffeyCE, editor. The Clinical Science of ECT. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC (1993). p. 93–109.

43

McCall WV Robinette GD Hardesty D . Relationship of seizure morphology to the convulsive threshold. Convuls Ther. (1996) 12:147–51.

44

American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA, United States: American Psychiatric Association (2022), Text Revision (DSM-5-TR).

45

Hasan A Falkai P Wobrock T Lieberman J Glenthøj B Gattaz WF et al . World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia - a short version for primary care. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. (2017) 21:82–90. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2017.1291839

46

Nierenberg AA DeCecco LM . Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. (2001) 62 Suppl 16:5–9.

47

Howes OD McCutcheon R Agid O de Bartolomeis A van Beveren NJ Birnbaum ML et al . Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: treatment response and resistance in psychosis (TRRIP) working group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and terminology. Am J Psychiatry. (2017) 174:216–29. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050503

48

Mora F Ramos-Quiroga JA Baca-García E Crespo JM Gutiérrez-Rojas L Madrazo A et al . Treatment-resistant depression and intranasal esketamine: Spanish consensus on theoretical aspects. Front Psychiatry. (2025) 16:1623659. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1623659

49

Tomczak M Tomczak E . The need to report effect size estimates revisited. Trends Sport Sci. (2014) 1:19–25.

50

UK ECT Review Group . Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2003) 361:799–808. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12705-5

51

Devanand DP Sackeim HA Prudic J . Electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment-resistant patient. Psychiatr Clin North Am. (1991) 14:905–23. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30275-2

52

Prudic J Haskett RF Mulsant B Malone KM Pettinati HM Stephens S et al . Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ECT. Am J Psychiatry. (1996) 153:985–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.985

53

Pluijms EM Birkenhäger TK Huijbrechts IP Moleman P . Influence of resistance to antidepressant pharmacotherapy on short-term response to electroconvulsive therapy. J Affect Disord. (2002) 69:93–9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00378-5

54

Singh A Kar SK . How electroconvulsive therapy works?: understanding the neurobiological mechanisms. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. (2017) 15:210–21. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2017.15.3.210

55

Kritzer MD Peterchev AV Camprodon JA . Electroconvulsive therapy: mechanisms of action, clinical considerations, and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. (2023) 31:101–13. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000365

56

Fetahovic E Janjic V Muric M Jovicic N Radmanovic B Rosic G et al . Neurobiological mechanisms of electroconvulsive therapy: molecular perspectives of brain stimulation. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:5905. doi: 10.3390/ijms26125905

57

Weaver L Williams R Rush S . Current density in bilateral and unilateral ECT. Biol Psychiatry. (1976) 11:303–12.

58

Weiner RD Coffey CE . Minimizing therapeutic differences between bilateral and unilateral nondominant ECT. Convuls Ther. (1986) 2:261–5.

59

Sackeim HA Luber B Katzman GP Moeller JR Prudic J Devanand DP et al . The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on quantitative electroencephalograms. Relationship to Clin outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1996) 53:814–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830090060009

60

Sackeim HA Mukherjee S . Neurophysiological variability in the effects of the ECT stimulus. Convuls Ther. (1986) 2:267–76.

61

Nobler MS Sackeim HA Prohovnik I Moeller JR Mukherjee S Schnur DB et al . Regional cerebral blood flow in mood disorders, III. Treatment and clinical response. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1994) 51:884–97. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110044007

62

Sackeim HA Long J Luber B Moeller JR Prohovnik I Devanand DP et al . Physical properties and quantification of the ECT stimulus: I. Basic principles. Convuls Ther. (1994) 10:93–123

63

Sackeim HA . The anticonvulsant hypothesis of the mechanisms of action of ECT: current status. J ECT. (1999) 15:5–26. doi: 10.1097/00124509-199903000-00003

64

Lee WH Deng ZD Kim TS Laine AF Lisanby SH Peterchev AV . Regional electric field induced by electroconvulsive therapy in a realistic finite element head model: influence of white matter anisotropic conductivity. Neuroimage. (2012) 59:2110–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.029

65

Aksay SS Hambsch M Janke C Bumb JM Kranaster L Sartorius A . Alcohol use disorder as a possible predictor of electroconvulsive therapy response. J ECT. (2017) 33:117–21. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000366

66

Xie H Ma R Yu M Wang T Chen J Liang J et al . History of tobacco smoking and alcohol use can predict the effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy in individuals with schizophrenia: a multicenter clinical trial. J Psychiatr Res. (2024) 180:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.09.045

67

Moss L Vaidya N . Does comorbid alcohol and substance abuse affect electroconvulsive therapy outcome in the treatment of mood disorders? J ECT. (2014) 30:22–5. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31829aaeb8

68

Brus O Cao Y Gustafsson E Hultén M Landen M Lundberg J et al . Self-assessed remission rates after electroconvulsive therapy of depressive disorders. Eur Psychiatry. (2017) 45:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.06.015

69

Nordenskjöld A von Knorring L Engström I . Predictors of the short-term responder rate of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders--a population based study. BMC Psychiatry. (2012) 12:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-115

70

Benson NM Seiner SJ Bolton P Fitzmaurice G Meisner RC Pierce C et al . Acute course treatment outcomes of electroconvulsive therapy in adolescents and young adults. J ECT. (2019) 35:178–83. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000562

71

Nucifora FC Jr Woznica E Lee BJ Cascella N Sawa A . Treatment resistant schizophrenia: clinical, biological, and therapeutic perspectives. Neurobiol Dis. (2019) 131:104257. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.08.016

72

Kho KH Zwinderman AH Blansjaar BA . Predictors for the efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy: chart review of a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. (2005) 66:894–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0712

73

Dombrovski AY Mulsant BH Haskett RF Prudic J Begley AE Sackeim HA . Predictors of remission after electroconvulsive therapy in unipolar major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. (2005) 66:1043–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0813

74

Medda P Mauri M Toni C Mariani MG Rizzato S Miniati M et al . Predictors of remission in 208 drug-resistant depressive patients treated with electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. (2014) 30:292–7. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000119

75

Haq AU Sitzmann AF Goldman ML Maixner DF Mickey BJ . Response of depression to electroconvulsive therapy: a meta-analysis of clinical predictors. J Clin Psychiatry. (2015) 76:1374–84. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14r09528

76

van Diermen L Poljac E van der Mast R Plasmans K Van den Ameele S Heijnen W et al . Toward targeted ECT: the interdependence of predictors of treatment response in depression further explained. J Clin Psychiatry. (2020) 82:20m13287. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13287

77

Mickey BJ Ginsburg Y Jensen E Maixner DF . Distinct predictors of short- versus long-term depression outcomes following electroconvulsive therapy. J Psychiatr Res. (2022) 145:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.12.028

78

Jelovac A Landau S Beeley P McCaffrey C Finnegan M Gusciute G et al . Why is electroconvulsive therapy for depression more effective in older age? A causal mediation analysis. A causal mediation analysis. Psychol Med. (2025) 55:e110. doi: 10.1017/S0033291725000807

79

Popiolek K Bejerot S Brus O Hammar Å. Landén M Lundberg J et al . Electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar depression: effectiveness and prognostic factors. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2019) 140:196–204. doi: 10.1111/acps.13075

80

Goegan SA Hasey GM King JP Losier BJ Bieling PJ McKinnon MC et al . Naturalistic study on the effects of electroconvulsive therapy on depressive symptoms. Can J Psychiatry. (2022) 67:351–60. doi: 10.1177/07067437211064020

81

Medda P Perugi G Zanello S Ciuffa M Cassano GB . Response to ECT in bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. (2009) 118:55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.014

82

Perugi G Medda P Zanello S Toni C Cassano GB . Episode length and mixed features as predictors of ECT nonresponse in patients with medication-resistant major depression. Brain Stimul. (2012) 5:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.02.003

83

Sienaert P Vansteelandt K Demyttenaere K Peuskens J . Ultra-brief pulse ECT in bipolar and unipolar depressive disorder: differences in speed of response. Bipolar Disord. (2009) 11:418–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00702.x

84

Hart KL McCoy TH Henry ME Seiner SJ Luccarelli J . Factors associated with early and late response to electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2023) 147:322–32. doi: 10.1111/acps.13537

85

Daly JJ Prudic J Devanand DP Nobler MS Lisanby SH Peyser S et al . ECT in bipolar and unipolar depression: differences in speed of response. Bipolar Disord. (2001) 3:95–104. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030208.x

86

Agarkar S Hurt SW Young RC . Speed of antidepressant response to electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar disorder vs. major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 265:355–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.048

87

Scheepstra KWF van Doorn JB Scheepens DS de Haan A Schukking N Zantvoord JB et al . Rapid speed of response to ECT in bipolar depression: a chart review. J Psychiatr Res. (2022) 147:34–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.008

88

Agarkar S Hurt S Lisanby S Young RC . ECT use in unipolar and bipolar depression. J ECT. (2012) 28:e39–40. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e318255a552

89

Kellner CH Husain MM Knapp RG McCall WV Petrides G Rudorfer MV et al . CORE/PRIDE Work Group. Right Unilateral Ultrabrief Pulse ECT in Geriatric Depression: Phase 1 of the PRIDE Study. Am J Psychiatry. (2016) 173:1101–1109. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15081101

90

Heijnen WTCJ Kamperman AM Tjokrodipo LD Hoogendijk JG van den Broek WW Birkenhager TK . Influence of age on ECT efficacy in depression and the mediating role of psychomotor retardation and psychotic features. J Psychiatr Res. (2019) 109:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.11.014

91

van Diermen L Vanmarcke S Walther S Moens H Veltman E Fransen E et al . Can psychomotor disturbance predict ECT outcome in depression? J Psychiatr Res. (2019) 117:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.07.009

92

O'Connor MK Knapp R Husain M Rummans TA Petrides G Smith G et al . The influence of age on the response of major depression to electroconvulsive therapy: a C.O.R.E. Report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2001) 9:382–90

93

Dominiak M Antosik-Wójcińska AZ Wojnar M Mierzejewski P . Electroconvulsive therapy and age: effectiveness, safety and tolerability in the treatment of major depression among patients under and over 65 years of age. Pharm (Basel). (2021) 14:582. doi: 10.3390/ph14060582

94

Sarma S Zeng Y Barreiros AR Dong V Massaneda-Tuneu C Cao TV et al . Clinical outcomes of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression in older old people relative to other age groups across the adult life span: a CARE Network study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2024) 39:e6133. doi: 10.1002/gps.6133

95

Damm J Eser D Schüle C Obermeier M Möller HJ Rupprecht R et al . Influence of age on effectiveness and tolerability of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. (2010) 26:282–8. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181cadbf5

96

Martin JL Strawbridge RJ Christmas D Fleming M Kelly S Varveris D et al . Electroconvulsive therapy: a Scotland-wide naturalistic study of 4826 treatment episodes. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. (2024) 5:100434. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsgos.2024.100434

97

Krech L Belz M Besse M Methfessel I Wedekind D Zilles D . Influence of depressed patients’ expectations prior to electroconvulsive therapy on its effectiveness and tolerability (Exp-ECT): a prospective study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2018) 268:809–17. doi: 10.1007/s00406-017-0840-8

98

Ferrea S Petrides G Ehrt-Schäfer Y Angst J Seifritz E Olbrich S et al . Outcomes of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with depressive symptoms with versus without comorbid personality disorders/traits: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2024) 149:18–32. doi: 10.1111/acps.13631

99

Carstens L Hartling C Stippl A Domke AK Herrera-Mendelez AL Aust S et al . A symptom-based approach in predicting ECT outcome in depressed patients employing MADRS single items. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2021) 271:1275–84. doi: 10.1007/s00406-021-01301-8

100

Blanken TF Kok R Obbels J Lambrichts S Sienaert P Verwijk E . Prediction of electroconvulsive therapy outcome: a network analysis approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2025) 151:521–8. doi: 10.1111/acps.13770

101

Hermida AP Goldstein FC Loring DW McClintock SM Weiner RD Reti IM et al . ElectroConvulsive therapy Cognitive Assessment (ECCA) tool: A new instrument to monitor cognitive function in patients undergoing ECT. J Affect Disord. (2020) 269:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.010

102

Kaurani L Besse M Methfessel I Methi A Zhou J Pradhan R et al . Baseline levels of miR-223-3p correlate with the effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with major depression. Transl Psychiatry. (2023) 13:294. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02582-4

103

Dellink A Vanderhaegen G Coppens V Ryan KM McLoughlin DM Kruse J et al . Inflammatory markers associated with electroconvulsive therapy response in patients with depression: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2025) 170:106060. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106060

104

Zeng QB Huang XB Xu R Shang DW Huang SQ Huang X et al . Kynurenine pathway metabolites predict antianhedonic effects of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. (2025) 379:764–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.03.041

105

Sun H Jiang R Qi S Narr KL Wade BS Upston J et al . Preliminary prediction of individual response to electroconvulsive therapy using whole-brain functional magnetic resonance imaging data. NeuroImage Clin. (2020) 26:102080. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102080

Summary

Keywords

bitemporal, electroconvulsive therapy, seizure threshold, titration, ultrabrief pulse, unilateral

Citation

Sordo E, Fuet L, Porpiglia F, Zrelli M, Amagat M, De Maricourt P, Gaillard R, Smadja S, Vinckier F, Schimpf C, Tomberli F, Mazeraud A, Domenech P and Chalah MA (2026) Variables associated with clinical outcomes and switching from unilateral to bitemporal electroconvulsive therapy: a retrospective study. Front. Psychiatry 16:1758353. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1758353

Received

01 December 2025

Revised

21 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Ming D. Li, Zhejiang University, China

Reviewed by

Shalini Naik, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), India

Aneesh Rahangdale, University of Central Florida, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Sordo, Fuet, Porpiglia, Zrelli, Amagat, De Maricourt, Gaillard, Smadja, Vinckier, Schimpf, Tomberli, Mazeraud, Domenech and Chalah.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Moussa A. Chalah, moussachalah@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.