- School of Management, Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, China

High-level willingness to participate in WHPPs (Workplace Health Promotion Programs) can not only benefit employers and employees, but also can produce many positive social effects. In order to expand the existing body of research, the effects of subject cognition, interpersonal trust, political trust, and occupational safety and health concerns were explored. We surveyed 680 Chinese migrant workers who were in charge of participation decisions in their households (2,500 residents involved) from the three typical provinces. The association of social-economic determinants with the willingness to participate and the participating behavior was studied by logistic regression analysis. We find that almost all of workers show relatively high levels of willingness to participate, while nearly seventy percent of the migrant workers had not engaged in actual participation behavior. Regression analyses revealed that subject cognition, interpersonal trust, political trust, and concern for occupational safety and health were factors significantly influencing participating subjects' willingness to engage in WHPPs. Furthermore, mediation analyses demonstrated that the influence of subject cognition was partially mediated by political trust. The influence of subject cognition was partially mediated by political trust. We discuss why political trust may impact the influence of subject cognition on the willingness to participate. Our results provided important insights for both academic and practical application.

Introduction

Migrant workers, who migrate from rural areas of their original residence to urban areas for work-seeking, are a unique group appearing in developing countries when experiencing economic transformation. Among these developing countries, China has the largest population, and wherein, has produced the largest human migration in history (1, 2). It was reported that there had been 168 million internal labor migrants (i.e., persons working outside of their home regions for at least 6 months) in 2015, more than 10% of its population (3). Furthermore, existing literature illustrated that In China, migrant workers have suffered the highest incidences of occupational diseases among various types of labor forces (4–6), mainly due to their exposure to poor working conditions (high concentration dust), occupational hazard (heavy metal pollution, occupational radiation) and long working hours (7, 8). In order to successfully manage occupational safety and health, strengthening citizen participation is an increasingly important aspect. In terms of occupational safety and social health governance, existing studies generally conducted meticulous and effective analyses from the perspective of the role and functions of government organizations, behavioral characteristics of participation subjects, and the occurrence mechanisms of social governance (9–11). By contrast, these studies paid less attention to the most fundamental subject: the participation of migrant workers in their own occupational safety and health governance. Most frequently, migrant workers were incorporated into the analyses as the targets of governance rather than the participating subjects of governance. As a result, there were few scholars placing emphasis on diversity of subjects (11, 12), the individual willingness and objective behaviors of migrant workers never obtained enough attention, and moreover, willingness of participation is integral to the success of occupational safety and social health programs. Therefore, OSH (Occupational Safety and Health) governance cannot achieve successful development without the participation of the migrant workers. The purpose of this research is to gain that understanding and explore the factors that influence migrant workers' decision to engage in OSH programs.

Workplace health promotion (WHP) is defined as preventing, minimizing and eliminating health hazards, and maintaining and promoting work ability. Wherein workers' health and wellness depends on various kinds of elements, such as physical and mental condition, social functions, healthy habits, energy and vitality. The healthy and productive workforce can bring economic benefits and citizen health (13). The concept WHP emerged as a popular strategy for improving health while providing cost benefits (14, 15). This type of program should remain prominent because of its ability to address workers' health rights and promote safe working environments (16). Workplace health promotion programs (WHPPs) aim to improve workers' overall health and well-being (17), including mental health, e.g., by reducing depression and anxiety (18, 19). These programs have provided positive work-related outcomes (14), such as reducing sickness-related absences (20), while increasing work productivity and attendance (13). Scholars have concluded that it is necessary to change health care spending from purchasing services for the passive treatment of occupational diseases to actively engaging in WHPPs (21). Various WHPPs have employed qualitative methods in their measurements (22, 23), analyzed the concept at organizational levels (17, 23), or emphasized the political framework (24, 25). Recently, Niessen et al. (26) analyzed whether individual characteristics and work-related determinants were associated with participation in a WHPPs. However, quantitative research regarding migrant workers' participation is relatively rare. There is a lack of research regarding individuals' attitudes toward WHPPs, and their willingness to participate in the programs. Consequently, research has not identified the factors that influence the decision to volunteer for WHPPs, or to invest time or money in such programs.

To address this gap in the research, our study investigated citizens' willingness to participate in WHPPs in terms of voluntary action and financial response behaviors. We focused on a subject's concern for occupational safety and health (OSH concern), cognitive consideration of the OSH governance participation (subject cognition), and interpersonal and political trust as the main factors that can influence willingness to participate in WHPPs. Specifically, social cognition models proposed that the participating behavior was derived from overall evaluation of the purpose, modes and effects of WHPPs (27–30). Self-cognition is also significant dimension, which can enable participants deal with confidence in individuals' knowledge and capabilities required to participate in WHPPs (31–33). Therefore, subject cognition should be considered to be an important factor influencing the willingness to participate in WHPPs. Additionally, in terms of trust, individuals with high levels of trusting tend to have more positive participation attitudes in political activities. Specifically, these people usually have more interest in communicating, cooperating and jointly participating in socially initiated activities (34). Except for these two factors, occupational safety and health concern is another significant element indicating how integrated one's interest in health is with one's daily activities, which also suggests an individual is health-oriented and has a positive attitude toward behaviors such as participating in WHPPs (27, 28, 35). We also considered the gap between actual participation behavior and behavior intentions (willingness to participate), because the concrete action is a step closer to civic engagement. Since the extent of the influence of these determinants on migrant workers' participation in WHPPs remains unknown, we proposed that a subject cognition, OSH concern, and interpersonal and political trust are the main factors influencing the willingness to participate. Understanding these determinants can provide better insights into the promotion of civic engagement in WHPPs. In turn, this research can highlight the steps needed to develop effective strategies to encourage migrant workers toward active participation and personal investment in WHPPs. In line with these goals, the current study addressed the following questions:

(1) Are migrant workers willing to participate in WHPPs?

(2) How does a subject cognition affect his/her willingness to participate in WHPPs?

(3) How do interpersonal trust and political trust influence a subject's willingness to participate in WHPPs?

(4) How do concerns about OSH influence a subject's willingness to participate in WHPPs?

To answer these questions, our study analyzed data from Chinese migrant workers, and employed multiple regression analyses and mediation analyses to examine the determinants of the willingness to participate in WHPPs. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section Literature Review reviews the related literature and proposes the hypotheses. Section Data and Methods presents our data and methods, while Section Results provides our results. In Section Discussion, we discuss the results, and Section Conclusions offers our conclusions, with our comments about the limitations of this paper and considerations for future work.

Literature Review

High-level willingness to participate in WHPPs can produce many positive effects in the field of public health promotion. Kim and Kim (36) found that it is necessary to develop an intervention program to improve college students' health. Richmond and McCracken (37) proposed that health promotion programs are worthwhile activities for elderly people. Employers, one of the benefits from participating WHPPs, is the improvement in morale and job satisfaction among employees (38). For employees, workplace health is considered vital method of health promotion, because the major people aged 18 to 64 would possibly spend a large amount of time there. Furthermore, such a healthier habitat at workplace can improve lifestyle in persons' daily life and the public health in the whole society. Therefore, in order to realize the aim to improve the participation in WHPPs, this research proposes the following hypotheses.

Subject Cognition

Social cognition models can predict the health related behavior. One prominent model based on individual health cognitions is the planned behavior theory. In detail this theory proposed that behavior, for instance the participation in WHPPs, is mainly influenced be behavioral intentions (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control) (39). Specifically, attitudes arise of individuals' beliefs about the positive or negative consequences or an overall evaluation of the situation (40). This concept description of attitude can provide the theoretical foundation for sense of acceptance, which can be viewed as participants' overall evaluation of the procedures, modes and effects of WHPPs. Additionally, perceived behavior control is conceptually related to concept of self-efficacy, that deals with confidence in one's knowledge or skills required to accomplish a given task (e.g., participating to WHPPs). In the research of teachers' participating workplace health promotion program, Farokhzadian et al. (41) proved that the health promotion training program correlates positively with the self-efficacy for health practices. Therefore, participants' self-cognition has the positive effects on their participating decision in WHPPs. Except for this, within the scope of social governance participation, this field developed around two models: socioeconomic status and rational choice. Wherein the former model measures an individual's socioeconomic status by using factors including income, education level, occupation, and family background (31, 42), but it hardly ensures the universality and consistency due to social and cultural diversity, and further weakens the explanatory power of the socioeconomic status model (43).

The rational choice model supplements the socioeconomic status model to some extent. The rational choice model stresses that individuals have the motivation to participate in governance activities only as long as the gains resulting from individual political participation exceed the costs (44). Based on this, Chytil et al. (45) described human behavior toward health preservation, and further pointed that passive consumerism care should be excluded from the perspective of rational choice. This approach explains individual behavioral decision-making in participating to health promotion program to a large extent. Some research focused on various aspects of migrant workers' participation in WHPPs is also a sub-specialty within the study of citizen engagement in political participation (30). Verba et al. (42) proposed that political participation refers to those activities that can affect the decision making of the government personnel or the choices made by them. Riker (46) stressed that the concept of political participation has three defining constituents: citizens with meaningful opinions over government; these preferences are presented through a presentation system; and are considered to be fixed to democratic process. For example, Noehammer et al. (47) almost exclusively deals with decision making of the government personnel, when exploring determinants of the participation rates in WHPPs, and Linnan et al. (48) stressed citizens' direct and immediate involvement can enhance the power to decide local issues in workplace health participation. Thus, the point is to make citizens more involved in solving WHPPs, even if this take place within a larger framework of a representative political engagement activity.

However, both the socioeconomic status model and rational choice model have apparent shortcomings in their respective explanations of individual behavior. While the former explores the restriction on behavior imposed by individual socioeconomic status, and the latter observes the influence of individual rational considerations on behavior, both ignore the influence of social structure that can be described as the perception of individuals' own interactions, and the interactions between all others in multi-agent participation (49). Our research explored migrant workers' willingness to participate in WHPPs by combining individual subject cognition with the objective restrictions of social structure. According to the socialization theory, during the process when individuals transform from “living beings” into “social being,” i.e., during the process when individuals learn social norms and internalize social values, civic engagement can exert socialization effects. Such engagement enables participants to develop a more pro-social value pattern because of their interaction with like-minded others (50). Once individuals internalize social identification norms and values as part of their personal cognitive processing, they unconsciously conform to these norms and values in their behavioral practices. This essential part of their world view encourages them to participate in relevant social governance, thereby forming willingness to participate in social governance, with associated preferences in behavioral choices.

Our research rested on the following three perspectives used to measure the variable of subjective cognition. (a) Social governance participation: The willingness of migrant workers to participate, and the degree of actual participation, have an intimate connection with their personal opinions about rights and obligations. John (51) proved that citizens have several means to influence the public decisions, and similarly, policy makers can fine-tune their interventions to reach more groups of people. During this two-way interaction process, Nakayama (52) proposed that individuals could not only participate in a political decision-making process, but also show “participation action” after acquiring full, precise, and correct cognition about personal rights and obligations. (b) Sense of responsibility: For individuals, sense of responsibility constitutes self-monitoring of personal behavior. A sense of responsibility demands that the individual's actions meet the expectations of society under specific conditions. Behavioral game theory emphasizes that a sense of responsibility can stimulate individuals to make decisions by stimulating self-presentation motivation. A higher sense of responsibility and higher sense of self-monitoring will result more easily in individual behaviors that match up to social norms and expectations (53). For WHPP social governance, migrant workers who have a stronger sense of responsibility with respect to social governance are likely to play a positive part in relevant governance affairs. (c) Sense of acceptance for social governance: Society regulates goals, corresponding goal achievement, and institutional norms for every member of society as part of the entire cultural system. If individuals agree with such norms, and believe they can realize expected goals by complying with these norms, they are likely to adhere to the standards (54). From the perspective of migrant workers, the existing social governance model provides the norms that affect their social governance, identifying their rights and obligations to participate in social governance. In this sense, individuals who have a stronger sense of acceptance of social governance will increase the possibility of joining in social governance.

Hypothesis 1.1: Migrant workers with greater subject cognition have greater willingness to participate in WHP programs.

Trust

Recently, a growing body of literature has been directed toward the concept of trust (55, 56), and this topic has been included in the research on political participation (29, 32, 33). In academic circles, there is a divergence of opinion about the conceptual definition and connotation of trust. One view regards trust as having certain expectations of others. Deutsch defined trust as “the expectation for a future time” and pointed out that such expectations would produce an impact on public decision-making behaviors (57). Sgro et al. (58) deemed trust to be certain psychological feelings whereby trustors are usually in the passive role and responsible for taking certain risks. Others viewed trust as a certain type of behavior. Messick and Kramer (59) indicated that trust refers to individual feedback behaviors based on judgments about the moral influences on others. Obviously, trust is a fundamental concept of interpersonal relationships and collaboration (60, 61). Luhmann (62) divided trust measurement into two dimensions: interpersonal trust and institutional trust. The former takes the affection among people as the bond that often exists in primary groups (such as families) and secondary groups (such as neighbors). Characterized by the intimacy of relationships, this bond leads to the intensity of trust. For instance, individuals have a stronger sense of trust in relatives than in neighbors (63). Political trust can be understood as citizens' confidence in political institutions, and this confidence can reflect their evaluations of the political environment (64). The decline in political trust can lead to a unique trend of political skepticism and civic disengagement that ultimately may affect the citizens' engagement in political activities (65).

There is little doubt that citizens who participate actively in political life display higher levels of political trust than passive citizens (66–68). This relationship between trust and civil engagement is complex. Trust demonstrates a positive correlation with volunteering activities (69) and financial investments in economic decision-making (70). Bäck and Christensen (71) found that generalized social trust is significant for the development for political participation, and argued that trust relates positively to citizens' propensity to become politically active. Dias and De Brito (23) emphasized the significance of trust for family health programs. Interpersonal trust can be considered as a kind of attitude toward others, or, perhaps, can best be conceptualized as how “trusting” an individual is (72). More trusting individuals will be more likely to commit themselves to community activities (e.g., health promotion program). It stands to reason that individuals with high levels of interpersonal trusting tend to have more positive participation attitudes in political activities. Specifically, these people usually have more interest in communicating, cooperating and jointly participating in socially initiated activities (34). However, the existing literature has neglected the analysis of different levels of interpersonal and political trust within the context of occupational health. The literature review above leads us to the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 2: Interpersonal trust has a positive influence on the willingness to participate in WHPPs.

Hypothesis 3: Political trust has a positive influence on the willingness to participate in WHPPs.

In addition to the direct effect of trust on the willingness to participate in political projects, our research proposed the interaction of subjects' cognition with interpersonal and political trust. Trust exists in relationships with peers and especially with friends (73), and also with political institutions (74). Hence, migrant workers' beliefs about themselves play a significant role in whether they participate in social governance, such the governance of a community. Their subjective cognition may affect trust at the individual and collective levels. We expect that for individuals, higher levels of subject cognition positively correlate with higher levels of trust. For these reasons, we considered that subject cognition has an association with a workers' participation behavior through changes in trust, and we proposed the following hypotheses

Hypothesis 1.2: Interpersonal trust mediates the effect of subject cognition on willingness to participate in WHPPs.

Hypothesis 1.3: Political trust mediates the effect of subject cognition on willingness to participate in WHPPs.

OSH Concern

It is of great significance to examine health cognition and perception in order to increase health promotion behaviors (75). Occupational safety and health concern is concept indicating how integrated one's interest in health is with one's daily activities, which also suggests an individual is health-oriented and has a positive attitude toward behaviors such as participating in WHPPs. Many researchers argued that workers' attitudes or concerns toward occupational safety and health can influence decision-making (27, 28). Lingard (35) argued that higher levels of concern about occupational health positively affect workplace health promotion behavior. Health-related attitudes have been found to be among the motivations for health promotion action (76, 77). Furthermore, Riley (78) demonstrated that occupational health awareness has a positive association with the willingness to support programs that promote workplace health. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: OSH concerns have a positive effect on the willingness to participate in WHPPs.

Conceptual Model

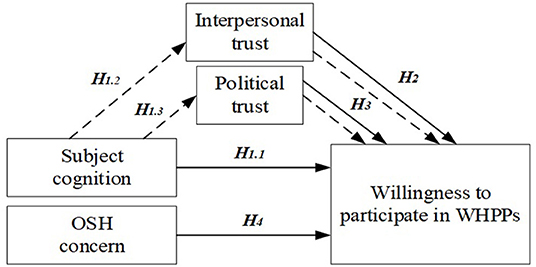

Based on the hypotheses, our study proposed a conceptual model that can test and examine determinants influencing the willingness to participate in WHPPs. This model emphasizes the analysis of specific factors derived from the relevant literature, and contains three main components: subject cognition, OSH concerns, and trust (interpersonal and political trust) in Figure 1. In addition, the model also includes social-demographic determinants, because the empirical evidence demonstrated that such factors have an effect on civic engagement in political activities (79, 80). Literature review and identification of the real problems were the basis for addressing research hypotheses and for building the conceptual model, listed below.

- The subject cognition has s a direct, positive and statistically significant effect on the willingness to participate in WHPPs (H1.1).

- Interpersonal trust mediates the effect of subject cognition on willingness to participate in WHPPs (H1.2).

- Political trust mediates the effect of subject cognition on willingness to participate in WHPPs (H1.3).

- There is a direct, positive and statistically significant relationship between the interpersonal trust and willingness to participate in WHPPs (H2).

- There is a direct, positive and statistically significant relationship between the political trust and willingness to participate in WHPPs (H3).

- There is a direct, positive and statistically significant relationship between the OSH concern and willingness to participate in WHPPs (H4).

To summarize, the theoretical model for the determinants of the willingness to participate in WHPPs integrates determinants from the theory of planned behavior, rational choice and the concept of political participation from political theories (39, 40, 81). The benefit of this model is that it identifies the important factors relevant in evaluating the subject cognition and OSH concern and their relationships with the willingness to participate in WHPPs. Additionally, the model assists researchers in determining what constituent parts might be relevant in the study of a particular phenomenon. This aligns with our intention of proposing a conceptual model which aids the researcher in the study of workplace health promotion and sustainable development.

Data and Methods

Data

To determine whether interpersonal trust and institutional trust have an impact on migrant workers' willingness to participate in workplace health promotion programs, we used field investigation data gathered by research groups in Anhui, Henan, Shanxi, and Shanxi Provinces. The research sample involved more than 2,500 residents in ~750 households. Using a random sampling approach, the investigation selected 750 rural households from Huaibei City in Anhui Province, Xuzhou City in Jiangsu Province, Xi'an City in Shanxi Province, and Taiyuan City in Shanxi Province. The researchers chose one family member who was familiar with family production and operation conditions as the respondent. Field investigation work in Huaibei, Taiyuan, and Xuzhou City proceeded from March through May 2017, while field work in Xi'an City took place in November 2017. There were 680 questionnaires altogether. It is worth mentioning here that for obtaining more precise investigation results, members in the research group donated small gifts worth about 20 RMB to every respondent prior to beginning formal questioning.

Model Selection

The main goal of our work was to explore the influence of trust on migrant workers' willingness to participate in WHP programs. Therefore, the explained variable of the research is migrant workers' participation willingness for WHP programs. This variable is defined as discrete (0-1) to avoid reflection problems in identification. In a linear model, personal characteristics would affect the explained variable in a linear manner (82) and accordingly lead to reflection problems. As demonstrated by the research of Brock and Durlauf (83), in Probit, Logit, and other non-linear models, reflection problems can be avoided. According to model fitting effects, in our research we selected the binary logistic model on the individual level to analyze the key influential factors of migrant workers' willingness to participate in WHPPs.

Suppose migrant workers' participation willingness is determined by the following formula:

Wherein the subscript i means the investigated. The explained variable “willingness” is the 0-1 variable about peasant participation willingness for WHP programs. If migrant workers are willing to participate in WHP programs, the value should be 1, or otherwise 0.

Measures

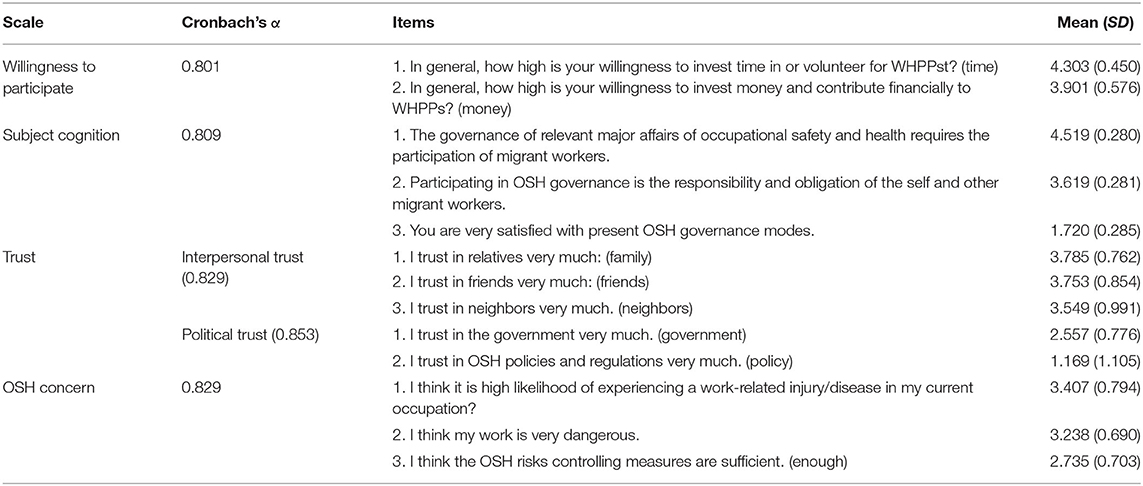

The face-to-face interviews included questions designed to reveal the subjects' interpersonal trust and political trust, subject cognition, and OSH concerns (Table 1). The main constructs were measured as follows.

Attitudes Toward OSH

The research measured migrant workers' attitudes toward OSH based on workplace health promotion. For example: (a). I would like to be offered a workplace program that promotes health. (b) I think that I would benefit from these OSH projects. Responses were assessed on a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) based on Röttger et al. (40). Other questions included workplace context, for example: If an OSH project was initiated by the government in your work place, with the goal of promoting migrant workers' workplace health status, in general, what would be your attitude toward this project? Responses to questions regarding attitude toward an OSH project promoting workplace health were measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive).

Willingness to Participate

We used three questions to measure migrant workers' willingness to participate in OSH projects. Are you willing to volunteer for an OSH project with the objective of calling attention to occupational disease groups and raising awareness of occupational hazards prevention? [In general, how high is your willingness to invest time in, or volunteer for, an OSH project (84)?] Are you willing to invest financial resources in an OSH project? (In general, how high is your willingness to invest money and contribute financially to an OSH project?) Each of these two items was rated using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high). The two items were significantly correlated with each other (Spearman's rho = 0.801). Therefore, we used the average score for these two items to represent willingness to participate in this research.

Subject Cognition

For this research, we chose three variables to reflect migrant workers' subjective cognition: cognition of rights and obligation, cognition of responsibility, and acceptance of social governance. For evaluation, we used the scale employed by Zhang and Li (85). The three response items were assessed using a 5-point, Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The three items formed an internally consistent scale (Cronbach's alpha = 0.809). For example, For example, (a) The governance of relevant major affairs of occupational safety and health requires the participation of migrant workers; (b) Participating in OSH governance is the responsibility and obligation of the self and other migrant workers; (c) You are very satisfied with present OSH governance modes.

Trust

Based on data from the European Social Survey (42) regarding the general measurement of trust, we further specified the objects that can be trusted. With the combination of social norms defined by Fugas et al. (86), we adjusted these five trust scale, extending it further to include peer influence on the willingness to participate in OSH projects. Hence, the concept of trust studied in our research was not trust in a general sense. Instead, we looked at migrant workers' actual rational behavioral expectations or effective identity with others up to personal interests in OSH governance. In our investigative process, we considered migrant workers' comprehension ability and acceptance, and transformed the five types of trust above into the following five research questions: (a) “I trust in relatives very much; (b) “I trust in friends very much; (c) “I trust in the government very much; (d) “I trust in OSH policies and regulations very much.”

OSH Concerns

To measure the degree of OSH concerns, we employed the scale applied by Lingard (35). It contained three question items, such as the following. (1) I think there is a high likelihood of experiencing a work-related injury or illness in my current occupation. (2) I think my work is very dangerous. (3) I think the measures taken by OSH to control risks are sufficient (enough). These items were measured on a 5-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The mean of the items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.829) was employed to represent the OSH concerns.

Control Variables

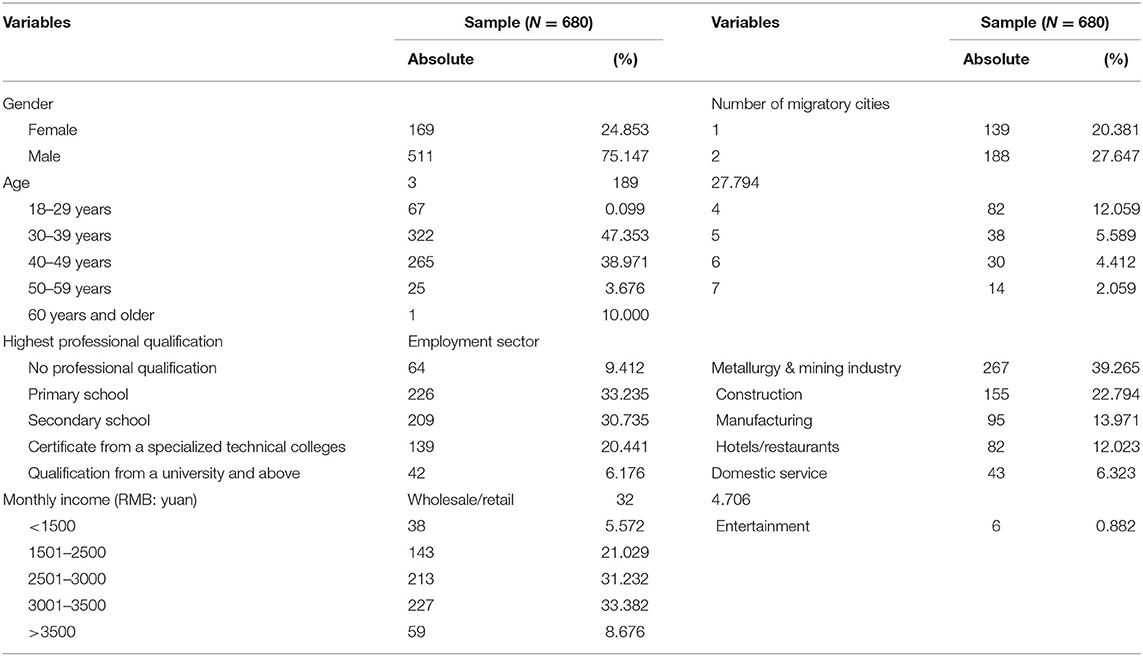

Regarding the selection of control variables (Table 2), “individual” is the individual characteristic vector that affects migrant workers' participation willingness. As proved by existing studies, gender, age, and education level all have significant impact on the participation rates in WHPPs (79–81). Consequently, personal characteristic variables chosen in our research included gender, age, education level, Number of migratory cities (the number of cities which workers migrate to in search of work), and employment sector. “Household” is the family characteristic vector that affects participation willingness, including net household income. The influence of these variables on WHPPs participation willingness has been proven (87). Therefore, family characteristic variable selected for this research included is family monthly income (measured by the monthly income in the family from a single source).

Results

To test our hypotheses, binary logistic regression and multiple regression analyses and mediation analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version. 23). First, we tested hypotheses H1.1, H2, and H3, represented as continuous lines in the conceptual model. In the next step, we tested the mediation effect of H1.2 and H1.3 using PROCESS software, employing a practice used in prior research (88).

Descriptive Statistics

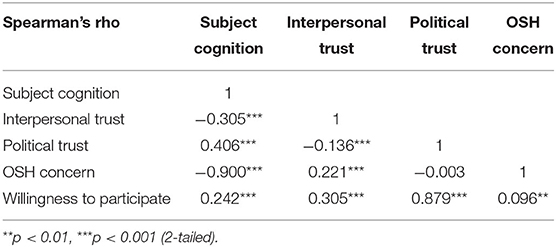

As is reported in Figure 2, the means of political trust (trust 4 and trust 5) is far below than interpersonal trust (trust 1, trust 2, trust 3). Specifically, the means of trust 1 (the trust to family) is highest (mean = 3.785, SD= 0.762; 5-point scale), followed by trust 2 (the trust to friends) (mean = 3.753, SD= 0.855; 5-point scale), while the means of trust 5 (the trust to policies) is lowest (mean = 1.169, SD= 1.105; 5-point scale). Specifically, each trust dimension was divided into low, medium, and high categories, obviously showing that the percentage of individuals, who had participated in WHPPs, represents an upward trend with the increasing degree of trust. A point should be noted that the percentage of actual participating behavior is similar among medium and high profiles of respondents.

According to Table 3, all the determinants in our study are found to be positively and significantly related to willingness to participate. There is a positive correlation between political trust and subject cognition, OSH concern and interpersonal trust. On the contrary, we found a positive correlation between interpersonal trust and subject cognition, political trust and interpersonal trust, OSH concern and subject cognition. Hence, except for the relationship between OSH concern and political trust, we find significant associations between subject cognition, trust and OSH concern.

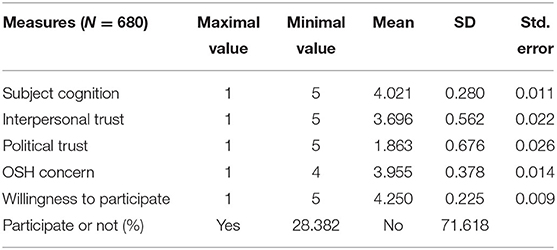

Table 4 summarizes the all the variables' descriptive statistics used in our conceptual model. As is shown that the mean of subject cognition (mean = 4.021; SD= 0.280; 5-point scale) is highest among exploratory variables, followed by OSH concern (mean = 3.955; SD= 0.378; 5-point scale), and interpersonal trust (mean = 3.702, SD= 0.562; 5-point scale). Each participants showed relatively high willingness to participate, but there is still exceed 70 percent of Chinese migrant workers failing to participate in WHPPs.

Regression Analyses

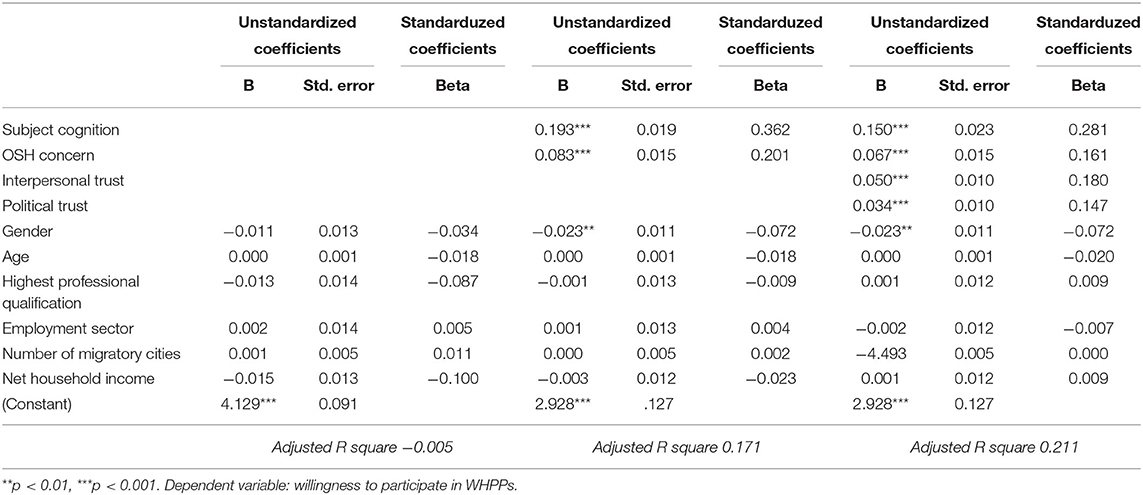

As is shown in Table 5, the model including all variables explains a substantial proportion of the dependent variable according to Adjusted R square, increasing from 0.005 to 0.211. The analysis presents that subject cognition (B = 0.281, p < 0.001), OSH concern (B = 0.161, p < 0.001), interpersonal trust (B = 0.180, p < 0.001), political trust (B = 0.147, p < 0.001), and gender (B = −0.072, p < 0.001) significantly correlate with the willingness to participate in WHPPs. Hence, the aforementioned results offer support for H1.1, H2, H3, H4. A point should be noted, females is found to be higher participation rates than males, which means that gender has predictive value for willingness to participate. Overall, subject cognition are found to have the highest effect on willingness to participate in WHPPs, followed by interpersonal trust, OSH concern, and political trust.

Mediation Analyses

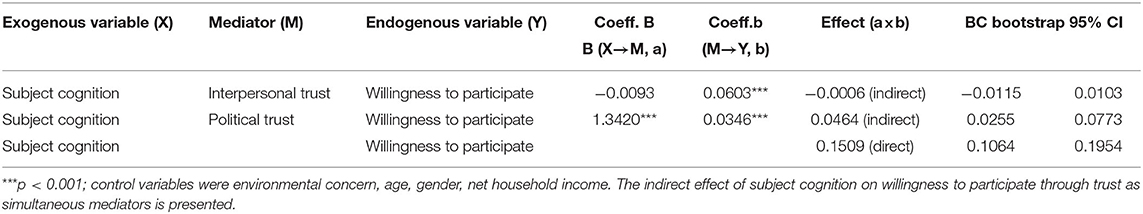

In order to test whether the influence of subject cognition is mediated be changes in interpersonal trust and political trust. We tested the mediation through using PROCESS macro, which is similar to Preacher and Hayes (89)'s research. The bootstrapping teats reported in Table 6 shows that the indirect effect of subject cognition on willingness to engage in WHPPs through interpersonal trust is non-significant (indirect effect = −0.0006, 95% CI = [−0.0115, 0.0103], on the precondition that the socio-demographic determinants are controlled. On the contrary, the indirect effect through political trust is positive and significant (indirect effect = 0.0464, 95% CI = [0.0255, 0.0773]. The direct effect was found to be positive and significant (indirect effect = 0.1509, 95% CI = [0.1064, 0.1954]) when mediators had been included in the model. Therefore, as we hypothesized, subject cognition affects willingness to participate in WHPPs, and this effect can be influenced through changes of political trust rather than interpersonal trust. That is, H1.3 are supported. The results reveals that political trust can partially mediate the relationship between subject cognition and willingness to participate.

Discussion

Our findings revealed that all migrant workers showed relatively high levels of willingness to participate in WHPPs, but almost 70 percent of the respondents failed to engage in actual participation behavior. This finding was in line with prior opinions (90) that a gap exists between behavior intention and actual behavior. Pai and Edington (90) proposed that behavior intention (i.e., willingness to participate in programs) can produce a positive effect on conducting actual behavior. Hence, our work further demonstrated that various types of barriers prevent participants from engaging in political activities. Our study proposed that these barriers can be identified as the subject cognition, OSH concern, and trust. With regards to subject cognition, although workers believe that, as an indispensable part of social governance, they have responsibility and obligation to take part in WHPPs, they showed rather unsatisfied with current OSH governance modes. That is, current governance mode is hardly acceptable for workers, which could act as a barrier for them to engage in political activities. On the one hand, migrant workers, as the governed object, could possibly feel less confidence in their knowledge, capacity required in participating to WHPPs, and further accomplishing the goal of health promotion. The main reason could be explained that they are socially less desirable group with lower socioeconomic status (91) and lower educational level (92). In terms of trust, the means of political trust was far lower than for interpersonal trust. Specifically, among the dimensions of trust, the individual's trust of family was the highest form of interpersonal trust, but the trust of OSH policies was lowest. Compared with political trust, interpersonal trust was often understood as a “cultural feature” that is closer to the degree of an individuals' general trust (93). This can be explained that individuals who have a greater propensity toward trusting other people are more likely to show higher levels of interpersonal trust in terms of different personalities (94). Our study showed that migrant workers with higher levels of interpersonal trust while relatively lower levels of political trust, in particular lowest trust in OSH policies. This finding may serve as an alert that policy makers and related institutions should pay more attention to the citizens' attitudes toward the government and its policies.

Among sonic-demographic variables, gender, monthly household income, and educational background have predictive value for willingness to participate to WHPPs, which is also examined in the research on the participation rates of African Americans recruited to a health promotion program (95). Specifically, females were found to have higher participation rates than males. These findings were in accordance with the research on gender differences in participation rates by Bernstein (96), who argued that women workers are more politically interested and active than their male counterparts. These findings highlighted the need to move toward a revised view of women engaging in political activities (97). Feminist research on women workers' higher participation rates proved empirically that females are significantly more politically active than men. For example, in terms of private activism, females are more likely to sign petitions, and boycott or buy products for political reasons. This private individualistic behavior is incorporated into their political participation more easily (97–99). Migrant workers' with lower household incomes or lower educational levels were more likely to have experience participating, which is in line with the findings of Cicatiello et al. (100)'s research. In that work, Cicatiello et al. argued that political involvement is positively affected by income, mainly because political activities are costly and require the investment of personal resources (e.g., money, skills). Our study held the opinion that migrant workers tend to work in urban areas to increase their income. Hence, they have more knowledge of occupational safety and health, and are more likely to participate in WHPPs. In addition, individuals with lower educational levels are persuaded easily to participate in collective activities, and therefore, they are more likely to participate in WHPPs. This result is similar to the findings of prior research indicating a link between and political participation (101–103). These scholars argued that education offers citizens the skills and resources needed to participate in political activities.

Therefore, in order to better design the program for promoting migrant worker's health, some insights can be gained from the results as follows: (1) the program is relatively feasible from theory significance, but the additional effort required is very high. The external policy advocacy and additional political education lessons are necessary. (2) The government and the relevant governing institutions should actively deliver the policy-oriented values to citizens and effectively enable migrant workers know the benefits of various policies. At the same time, it is necessary to re-establish and strengthen the trust bond between the migrant workers and the government, as well as the perception of the existence, obligation and utility perceived by them in the participating process of political activities. (3) Another important point is the investigation of participants' knowledge, acceptance and satisfaction toward programs, which is part of the program design. The participants should be divided according to the characteristics of population variables (e.g., education, income level). Based on this, the government should formulate targeted policies with regard to different groups, aiming to maximize the willingness to participate in WHPPs.

Conclusions

This study aimed to provide a better understanding of civic engagement in political activities by studying Chinese migrant workers' willingness to participate in WHPPs. We proposed and tested hypotheses based on a conceptual model that focused on subject cognition, interpersonal and political trust, and OSH concerns. All the interviewed Chinese migrant workers had the intention to engage in WHPPs. However, almost seventy percent of the participants did not actually participate in WHPPs, as measured in terms of their workplace health promotion behavior. Our analyses revealed that subject cognition, interpersonal trust, political trust, and OSH concerns were positively associated with the willingness to participate. Subject cognition and OSH concern were the most strongly positively associated with the willingness to participate, followed by interpersonal trust, and political trust. In our study, gender was the only one of the social-demographic variables that could predict the willingness to participate in WHPPs. Interpersonal and political trust demonstrated a partial mediation effect through subject cognition on the willingness to participate. From the viewpoint of all dimensions, male migrant workers' participation rates did not correlate significantly with their trust in their neighbors (trust 3). Likewise, the participation rates of migrant workers with a high-education level did not demonstrate significant correlation with trust in families (trust 2), neighbors (trust 3), or policies (trust 5). However, interpersonal and political trust, and their five dimensions, showed significant correlation with gender, income, and education levels.

This paper highlighted the need for research regarding interpersonal and political trust as measured in terms of workplace health promotion. In so doing, we aimed to contribute to the academic research on workplace health promotion and related political participation. Our study can enlarge the scope of social-psychological research into workers' intentions and behavior regarding programs that promote workplace health. Certain individual characteristics, such as trust, can be used as indicators to determine willingness to participate. Furthermore, the gap between intention and behavior is also addressed in our study. The data regarding actual behavior can advance the relevant research on civic engagement in WHPPs. Furthermore, our findings can help improve the initiation and smooth operation of WHPPs through consideration of the effects of trust, subject cognition, and OSH concern. This approach can improve related policy planning and increase citizens' responses. The high levels of willingness to participate in our study revealed that the policy makers should establish an appropriate management framework that could help migrant workers to form sustained participation in WHPPs. Meanwhile, related OSH policies should pay more attention to lowering the costs and barriers for workers' participation rates in WHPPs, with the aim of improving OSH management. Specifically, raising health-care consciousness at workplaces may offer a foundation for active participation. Consciousness-raising can be accomplished through OSH-related education and training programs aimed at informing employees of the individual personal benefits they can achieve. In this way, an increasing rate of civic engagement in WHPPs in China could improve the management of the national occupational safety and health scheme.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by China University of Mining and Technology. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

XH: Conceptualization, Data Collection, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, and Writing- review and editing.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the long-term social assistance recipients in Jiangsu, Shanxi, and Anhui provinces for field data collection. We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for revising the English draft.

References

1. Luo H, Yang H, Xu X, Yun L, Chen R, Chen Y, et al. Relationship between occupational stress and job burnout among rural-to-urban migrant workers in Dongguan, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e012597. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012597

2. Li M. Protection for migrant workers under evolving occupational health and safety regimes in China. Relat Industrielles. (2017) 72:56. doi: 10.7202/1039590ar

3. National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2012 National Report On Migrant Workers of China. (2013) Available Online at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201305/t20130527_12978.html (accessed May 27, 2013).

4. Zhang X, Wang Z, Li T. The current status of occupational health in China. Environ Health Prev Med. (2010) 15:263–70. doi: 10.1007/s12199-010-0145-2

5. Wang H, Tao L. Current situations and challenges of occupational disease prevention and control in China. Ind Health. (2012) 50:73–9. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.MS1341

6. Sun L, Liu T. Occupational diseases and migrant workers' compensation claiming in China: an unheeded social risk in asymmetrical employment relationships. Health Sociol Rev. (2016) 25:122–36. doi: 10.1080/14461242.2015.1099113

7. National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2011 National Report On Migrant Workers of China. (2012) Available Online at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/ztjc/ztfx/fxbg/201204/t20120427_16154.html (accessed April 27, 2012).

8. Han L, Shi L, Lu L, Ling L. Work ability of Chinese migrant workers: the influence of migration characteristics. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-353

9. Yacuzzi E, Minguillón RF. Design of An Indicator for Health and Safety Governance, Cema Working Papers Serie Documentos De Trabajo, Serie Documentos de Trabajo, No. 399. Toronto: Universidad del CEMA (2009).

10. Lo D. OHS stewardship - integration of OHS in corporate governance. Procedia Eng. (2012) 45:174–9. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2012.08.139

11. Shammi M, Hasan N, Rahman MM, Begum K, Sikder MT, Bhuiyan MH, et al. Sustainable pesticide governance in Bangladesh: socio-economic and legal status interlinking environment, occupational health and food safety. Environ Syst Decis. (2017) 37:243–60. doi: 10.1007/s10669-017-9628-7

12. Tepe S, Haslett T. Occupational health and safety systems, corporate governance and viable systems diagnosis: an action research approach. Syst Pract Action Res. (2002) 15:509–22. doi: 10.1023/A:1021064704360

13. Cancelliere C, Cassidy JD, Ammendolia C, Côté P. Are workplace health promotion programs effective at improving presenteeism in workers? A systematic review and best evidence synthesis of the literature. BMC Public Health. (2011) 11:395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-395

14. Holmqvist M. Corporate social responsibility as corporate social control: the case of work-site health promotion. Scand J Manag. (2009) 25:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2008.08.001

15. World Economic Forum. The Workplace Wellness Alliance—Making the Right Investment: Employee Health and the Power of Metrics. (2018) Available Online at: https://www.weforum.org/reports/workplace-wellness-alliance-making-right-investment-employee-(accessed March 8, 2018).

16. Hodgins M, Battel-Kirk B, Asgeirsdottir AG. Building capacity in workplace health promotion: the case of the healthy together e-learning project. Glob Health Promot. (2010) 17:60–8. doi: 10.1177/1757975909356629

17. Groeneveld IF, Proper KI, van der Beek AJ, Hildebrandt VH, van Mechelen W. Lifestyle-focused interventions at the workplace to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease – a systematic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2010) 36:202–15. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2891

18. Kuoppala J, Lamminpää A, Husman P. Work health promotion, job well-being, and sickness absences—a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Occup Environ Med. (2008) 50:1216–27. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31818dbf92

19. Martin A, Sanderson K, Cocker F. Meta-analysis of the effects of health promotion intervention in the workplace on depression and anxiety symptoms. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2009) 35:7–18. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1295

20. Chapman LS. Meta-evaluation of worksite health promotion economic return studies: 2012 update. Am J Health Promot. (2012) 26: TAHP1–2. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.26.4.tahp

21. Byrne DW, Goetzel RZ, McGown PW, Holmes MC, Beckowski MS, Tabrizi MJ, et al. Seven-year trends in employee health habits from a comprehensive workplace health promotion program at Vanderbilt University. J Occup Environ Med. (2011) 53:1372–81. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318237a19c

22. Dellve L, Skagert K, Vilhelmsson R. Leadership in workplace health promotion projects: 1- and 2-year effects on long-term work attendance. Eur J Public Health. (2007) 17:471–6. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm004

23. Dias L, De Brito M. (2012). Stress management programs as an occupational health promotion project in a Portuguese organizational setting. In: Proceedings of 5th International Scientific Conference—Quality Health Care Treatment in the Framework of Education, Research and Multi Professional Collaboration—Towards the Health of Individuals and Society (Ljubljana). p. 41–52.

24. Hickel S, Palkovich T. Workplace health promotion in domiciliary care — an Austrian project. J Integr Care. (2005) 13:26–33. doi: 10.1108/14769018200500030

25. Li S, Li T, Li CL, Wang C. Intervention strategies for the national project of workplace health promotion in China. Biomed Environ Sci. (2015) 28:396–400. doi: 10.3967/bes2015.046

26. Niessen MAJ, Laan EL, Robroek SJW, Essink-Bot M-L, Peek N, Kraaijenhagen RA, et al. Determinants of participation in a web-based health risk assessment and consequences for health promotion programs. J Med Internet Res. (2013) 15:e151. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2387

27. Franco G. Evidence-based decision making in occupational health. Occup Med. (2005) 55:1–2. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh118

28. Kamuzora P. Non-decision making in occupational health policies in developing countries. Int J Occup Environ Health. (2006) 12:65–71. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2006.12.1.65

29. Hu R, Sun IY, Wu Y. Chinese trust in the police: the impact of political efficacy and participation. Soc Sci Quart. (2015) 96:1012–26. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12196

30. Sjoberg FM, Mellon J, Peixoto T. The Effect of Government Responsiveness on Future Political Participation, Working Paper #1. Washington, DC: World Bank (2015).

31. Holbrook AL, Sterrett D, Johnson TP, Krysan M. Racial disparities in political participation across issues: the role of issue-specific motivators. Polit Behav. (2016) 38:1–32. doi: 10.1007/s11109-015-9299-3

32. Tseng LM, Wu JY. The relationship between political trust and participation in the national pension program: a case study of Taiwan. J Soc Serv Res. (2016) 42:610–21. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2016.1216916

33. Ardèvol-Abreu A, Hooker CM, Gil de Zúñiga H. Online news creation, trust in the media, and political participation: direct and moderating effects over time. Journalism. (2018) 19:611–31. doi: 10.1177/1464884917700447

34. Hoell RC. The effect of interpersonal trust and participativeness on union member commitment. J Bus. Paychol. (2004) 19:161–77. doi: 10.1007/s10869-004-0546-6

35. Lingard H. The effect of first aid training on Australian construction workers' occupational health and safety motivation and risk control behavior. J Safety Res. (2002) 33:209–30. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4375(02)00013-0

36. Kim MY, Kim YJ. What causes health promotion behaviors in college students? Open Nurs J. (2018) 12:106–15. doi: 10.2174/1874434601812010106

37. Richmond D, McCracken H. Health promotion and education for the elderly: experience in an academic department of geriatric medicine. Austalian J Ageing. (1996) 15:18–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.1996.tb00194.x

38. Allegrante JP, Michela JL. Impact of a school-based workplace health promotion program on morale of inner-city teachers. J School Health. (1990) 60:25–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1990.tb04772.x

39. Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press (2010).

40. Röttger S, Maier J, Krex-Brinkmann L, Kowalski JT, Krick A, Felfe J, et al. Social cognitive aspects of the participation in workplace health promotion as revealed by the theory of planned behavior. Prev Med. (2017) 105:104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.09.004

41. Farokhzadian J, Sabzi A, Shahrbabaki PM. Improving the self-efficacy of teachers in schools: results of health promotion program. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2018) 10:1–9. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2017-0170

42. Verba S, Nie NH, Kim JO. Participation and Political Equality: A Seven-Nation Comparison. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (1978).

43. Davis CL. Political regimes and the socioeconomic resource model of political mobilization: some Venezuelan and Mexican data. J Politics. (1983) 45:422–48. doi: 10.2307/2130133

44. Bäck H, Teorell J, Westholm A. Explaining modes of participation: a dynamic test of alternative rational choice models. Scan Polit Stud. (2011) 34:74–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2011.00262.x

45. Chytil Z, Klesla A, Kosička T. Economic interpretation of human behaviour in terms of health promotion. Prague Econ Papers. (2015) 24:371–85. doi: 10.18267/j.pep.542

46. Riker W. Liberalism Against Populism:A Confrontation Between the Theory of Democracy and the Theory of Social Choice. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press (1982).

47. Noehammer E, Schusterschitz C, Stummer H. Determinants of employee participation in workplace health promotion. Int J Workplace Health Manage. (2010) 3:97–110. doi: 10.1108/17538351011055005

48. Linnan L, Sorensen G, Colditz G, Emmons K. Using theory to understand the multiple determinants of low participation in worksite health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav. (2001) 28:591–607. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800506

49. Heald M, Contractor N, Koehly L, Wasserman S. Formal and emergent predictors of coworkers' perceptual congruenceon an organization's social structure. Hum Commun Res. (1998) 24:536–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1998.tb00430.x

50. Quintelier E, Hooghe M. Political attitudes and political participation: a panel study on socialization and self-selection effects among late adolescents. Int Pol Sci Rev. (2012) 33:63–81. doi: 10.1177/0192512111412632

51. John P. Can citizen governance redress the representative bias of political participation? Public Adm Rev. (2009) 69:494–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.01995.x

52. Nakayama C. The acceptance of democracy and political participation: a quantitative analysis of political consciousness among the kinki area electorates. Kyoto J Sociol. (2001) 9:39–54. doi: 10.1007/s10869-2433/192614

53. Shefrin H. Behavioral decision making, forecasting, game theory, and role-play. Int J Forecast. (2002) 18:375–82. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2070(02)00021-3

54. Soma K, Haggett C. Enhancing social acceptance in marine governance in Europe. Ocean Coast Manag. (2015) 117:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.11.001

55. De Almeida MMK, Marins FAS, Salgado AMP, Santos FCA, da Silva SL. Mitigation of the bullwhip effect considering trust and collaboration in supply chain management: a literature review. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. (2015) 77:495–513. doi: 10.1007/s00170-014-6444-9

56. Østergaard LR. Trust matters: a narrative literature review of the role of trust in health care systems in sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Public Health. (2015) 10:1046–59. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1019538

57. Deutsch M. Trust and suspicion. J Conflict Resolut. (1958) 2:265–79. doi: 10.1177/002200275800200401

58. Sgro JA, Worchel P, Pence EC, Orban JA. Perceived leader behavior as a function of the leader's interpersonal trust orientation. Acad Manage J. (1980) 23:161–5. doi: 10.5465/255504

59. Messick DM, Kramer RM. Trust as a form of shallow morality. In: Cook KS, ed. Trust in Society. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation (2001). p. 89–118.

60. Misztal BA. Trust in Modern Societies: The Search for the Bases of Social Order. New York, NY: Polity Press (1996).

61. Declerck CH, Boone C, Emonds G. When do people cooperate? The neuroeconomics of prosocial decision making. Brain Cogn. (2013) 81:95–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2012.09.009

63. Portes A, Sensenbrenner J. Embeddedness and immigration: notes on the social determinants of economic action. Am J Sociol. (1993) 98:1320–50. doi: 10.1086/230191

64. Catterberg G, Moreno A. The individual bases of political trust: trends in new and established democracies. Int J Public Opin Res. (2006) 18:31–48. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edh081

65. Putnam RD. Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2002).

66. Almond GA, Verba S. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton, CA: Princeton University Press (1963).

67. Barnes SH, Allerbeck KR, Farah BG, Heunks FJ, Inglehart RF, Jennings MK, et al. Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies. Beverly Hill, CA: Sage (1979).

68. Van Deth JW, Montero JR, Westholm A. Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis. London: Routledge (2007).

69. Welzel C. How selfish are self-expression values? A civicness test. J Cross Cult Psychol. (2010) 41:152–74. doi: 10.1177/0022022109354378

70. Ding Z, Au K, Chiang F. Social trust and angel investors' decisions: a multilevel analysis across nations. J Bus Ventur. (2015) 30:307–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.08.003

71. Bäck M, Christensen HS. When trust matters—a multilevel analysis of the effect of generalized trust on political participation in 25 European democracies. J Civ Soc. (2016) 12:178–97. doi: 10.1080/17448689.2016.1176730

72. Zaheer A, McEvily B, Perrone V. Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organ Sci. (1998) 9:141–59. doi: 10.1287/orsc.9.2.141

73. Flanagan C. Trust, identity, and civic hope. Appl Dev Sci. (2003) 7:165–71. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_7

74. Verhaegen S, Hooghe M, Quintelier E. The effect of political trust and trust in European citizens on European identity. Eur Polit Sci Rev. (2017) 9:161–81. doi: 10.1017/S1755773915000314

75. Chen M, Wang J. The effectiveness and barriers of implementing a workplace health promotion program to improve metabolic disorders in older workers in Taiwan. Glob Health Promot. (2014) 23:447–79. doi: 10.1177/1757975914555341

76. Morgan PP, Shephard RJ, Finucane R, Schimmelfing L, Jazmaji V. Health beliefs and exercise habits in an employee fitness programme. Can J Appl Sport Sci. (1984) 9:87–93.

77. Ho WY, Sung CY, Yu QH, Chan CC. Effectiveness of computerized risk assessment system on enhancing workers' occupational health and attitudes towards occupational health. Work. (2014) 48:471–84. doi: 10.3233/WOR-141916

78. Riley MM. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Occupational Health Nurses to Health Promotion at the Work Place and Implications for Control of Lifestyle Diseases. (Doctoral Dissertation), University of the West Indies, Kingston (Jamaica) (1994).

79. Gaviria A, Panizza U, Seddon Wallack J. Economic, social and demographic determinants of political participation in Latin America: evidence from the 1990s. Rev Latinoam Desarrollo Econ. (2004) 151–82. doi: 10.35319/lajed.20043279

80. Wan Mohd Nor WA, Abdul Gapor S, Abu Bakar ZM, Harun Z. (2011). Some socio-demographic determinants of political participation. In: Proceedings of 2011 International Conference on Humanities, Society and Culture (Singapore). p. 69–73.

81. Tolbert CJ, McNeal RS. Unraveling the effects of the Internet on political participation? Polit Res Q. (2003) 56:175–85. doi: 10.1177/106591290305600206

82. Furnham A, Petrides KV, Tsaousis I, Pappas K, Garrod D. A cross-cultural investigation into the relationships between personality traits and work values. J Psychol. (2005) 139:5–32. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.139.1.5-32

83. Brock WA, Durlauf SN. Identification of binary choice models with social interactions. J Econom. (2007) 140:52–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2006.09.002

84. Kalkbrenner BJ, Roosen J. Citizens' willingness to participate in local renewable energy projects: the role of community and trust in Germany. Energy Res Soc Sci. (2016) 13:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.006

85. Zhang CE, Li YM. Subject cognition, situational restrictions and farmers' willingness to participate: an emipirical analysis on 5 provinces in Shandong. China Rural Surv. (2015) 69–80. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(82)90035-2

86. Fugas CS, Meliá JL, Silva SA. The “is” and the “ought”: how do perceived social norms influence safety behaviors at work? J Occup Health Psychol. (2011) 16:67–9. doi: 10.1037/a0021731

87. Crespo NC, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Worksite physical activity policies and environments in relation to employee physical activity. Am J Health Promot. (2011) 25:264–71. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.081112-QUAN-280

88. Tremblay J, Abi-Zeid I. Value-based argumentation for policy decision analysis: methodology and an exploratory case study of a hydroelectric project in Québec. Ann Oper Res. (2016) 236:233–53. doi: 10.1007/s10479-014-1774-4

89. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. (2008) 40:879–91. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

90. Pai CW, Edington DW. Association between behavioral intention and actual change for physical activity, smoking, and body weight among an employed population. J Occup Environ Med. (2008) 50:1077–83. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31817d0795

91. Ortega MI, Sabo S, Aranda Gallegos P, De Zapien JEG, Zapien A, Portillo Abril GE, et al. Agribusiness, corporate social responsibility, and health of agricultural migrant workers. Front Public Health. (2016) 4:54. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00054

92. Bhandari P, Kim M. Predictors of the health-promoting behaviors of Nepalese migrant workers. J Nurs Res. (2016) 24:232–9. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000120

93. Hwang I. D. (2017). Which type of trust matters? interpersonal vs. institutional vs. political trust, WP 2017-15. In: The Bank of Korea. Seoul: Economic Research Institute.

94. Mooradian T, Renzl B, Matzler K. Who trusts? Personality, trust and knowledge sharing. Manag Learn. (2006) 37:523–40. doi: 10.1177/1350507606073424

95. Halbert C, Kumanyika S, Bowman M, Bellamy S, Briggs V, Brown S, et al. Participation rates and representativeness of African Americans recruited to a health promotion program. Health Educ Res. (2009) 25:6–13. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp057

96. Bernstein AG. The private roots of public action: gender, equality, and political participation (review). Rhetoric Public Aff. (2002) 5:548–9. doi: 10.1353/rap.2002.0046

97. Coffé H, Bolzendahl C. Same game, different rules? Gender differences in political participation. Sex Roles. (2010) 62:318–33. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9729-y

98. Siim B. Gender and Citizenship: Politics and Agency in France, Britain and Denmark. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2000).

99. Harrison L, Munn J. “Gendered (non) participants? What constructions of citizenship tell us about democratic governance in the twenty-first century. Parliam Aff. (2007) 60:426–36. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsm016

100. Cicatiello L, Ercolano S, Gaeta GL. Income distribution and political participation: a multilevel analysis. Empirica. (2015) 42:447–79. doi: 10.1007/s10663-015-9292-4

101. Schlozman KL. Citizen participation in America: what do we know? Why do we care?. In: I Katznelson, HV Milner, editors. Political Science: State of Discipline. New York, NY: W W Norton & Company (2002). p. 433–61.

102. Hillygus DS. The missing link: exploring the relationship between higher education and political engagement. Polit Behav. (2005) 27:25–47. doi: 10.1007/s11109-005-3075-8

Keywords: workplace health promotion programs, interpersonal trust, political trust, subject cognition, health concern, political participation

Citation: Huang X (2020) Migrant Workers' Willingness to Participate in Workplace Health Promotion Programs: The Role of Interpersonal and Political Trust in China. Front. Public Health 8:306. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00306

Received: 06 November 2019; Accepted: 05 June 2020;

Published: 14 July 2020.

Edited by:

Vesna Bjegovic-Mikanovic, University of Belgrade, SerbiaReviewed by:

Harald Stummer, UMIT - Private Universität Für Gesundheitswissenschaften, AustriaMuyi Yang, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

Copyright © 2020 Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinru Huang, aHhyODgxMDAzQDE2My5jb20=

Xinru Huang

Xinru Huang