- 1National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente Muñiz, Directorate of Epidemiological and Psychosocial Research, Mexico City, Mexico

- 2KEDGE Business School, Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development, Department of Strategy, Marseille, France

- 3National Institute of Public Health, Health Systems Research Center, Cuernavaca, Mexico

- 4Medical Sciences, National Institute of Public Health, Health Systems Research Center, Cuernavaca, Mexico

The COVID-19 pandemic has become the greatest burden of disease worldwide and in Mexico, affecting more vulnerable groups in society, such as people with mental disorders (MD). This research aims to analyze the governance processes in the formulation of healthcare policies for people with MD in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. An analytical qualitative study, based on semi-structured interviews with key informants in the healthcare system was conducted in 2020. The study followed the theoretical-methodological principles of the Governance Analytical Framework (GAF). The software ATLAS.ti-V.9 was used for inductive thematic analysis, classifying themes and their categories. To ensure the proper interpretation of the data, a process of triangulation among the researchers was carried out. The findings revealed that in Mexico, the federal Secretary of Health issued guidelines for mental healthcare, but there is no defined national policy. Decision-making involved multiple actors, with different strategies and scopes, depending on the type of key-actor and their level of influence. Majority of informants described a problem of implementation in which infection control policies in the psychiatric population were the same as in the general populations which decreased the percentage of access to healthcare during the pandemic, without specific measures to address this vulnerable population. The results suggest that there is a lack of specific policies and measures to address the needs of people with mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. It also highlights the importance of considering the role of different actors and their level of influence in the decision-making process.

1. Introduction

Currently, the pandemic due to the new coronavirus COVID-19 is the cause of the greatest burden of the disease worldwide as well as in Mexico (1). Due to the characteristics of its spread and the health measures for its control, it can increase the vulnerability of people with mental disorders (MD). Different measures of social isolation can affect the mood of these people with the consequent aggravation of their different psychopathological conditions. Consequently, the families and institutions that are protected by these people must offer specific assistance and monitoring to each of them (2). Governments in all countries have formulated various policies in health systems to address the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) due to COVID-19, but responsiveness has represented a global challenge (3). This situation highlighted the lack of cohesion that exists between the institutions of the Mexican National Health System (NHS). The Mexican NHS is composed and financed by both the public and private sectors. The public sector provides care to (1) people affiliated with social security (who receive a formal salary) through the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS—from now on acronyms are in Spanish), the Institute of Security and Social Services of State Workers (ISSSTE), the Armed Forces (SEDENA and SEMAR) and the Mexican Petroleum (PEMEX). This represents 48.3 million people funded by employers, workers and the federal government; and (2) people without social security (who do not have a formal salary) who receive care from the Secretary of Health, Federal (SSA) or States' (SESA), and which are the object of this study. Up until the year 2019, the healthcare of these 58 million people had been financed in two ways, (1) by the federal government and the state governments through the System of Social Protection of Health and its program “Popular Insurance” (“Seguro Popular”), and/or (2) the out-of-pocket expenses of the user at the point of service (4).

At that time, when the COVID-19 pandemic was declared (March 2020), the NHS was implementing a new scheme for the provision of health services to the population without social security. This has implied stagnation in the programmed implementation of the reform strategies for the period 2019–2024, and instead, the mitigation of the pandemic was established as a priority programmatic axis (5). As a central strategy of the response, a process called “hospital reconversion” was carried out, which prioritized COVID-19 care first, without defining or informing users of procedures for monitoring the routine demand for medical services in general.

In addition, half of the people who receive medical care due to some MD, especially severe, do so in psychiatric hospitals, which suffer from low budget and resources to provide quality care (6, 7), furthermore, in a pandemic context people with mental pathology have a greater probability of getting sick with another chronic pathology than the general population (8–10). In consequence, the Mexican NHS has two challenges to guaranteeing care in psychiatric hospitals. On one hand, there are long-stay psychiatric hospitals with a confined population. On the other hand, psychiatric hospitals with functioning like that of a general hospital. First, patients are more vulnerable to being infected; in such a situation, measures should be taken to prevent contagion in a gated community (11), in the latter, they must also ensure the continuity of psychiatric care that allows treatment adherence, especially for serious conditions, monitoring the risk of aggressiveness toward oneself or others, as well as detecting symptoms associated with living in quarantine such as stress, anxiety or depression due to the current pandemic (12).

Several studies have reported strategies to ensure the medical care of the mentally ill during the epidemic with measures such as reducing the length of stay, reducing visits to admitted patients, reducing outpatient care and in hospitalized patients, timely detection of high-risk or suspected COVID-19 patients and isolation of positive patients (12–14). In Mexico, the strategy of offering psychosocial support was aimed at the general population that does not have COVID-19, people with COVID-19 who are isolated at home and/or in hospital, the population that referred COVID-19, relatives and caregivers of patients with COVID-19, health personnel and lifeguards before the emergency; it included psychological first aid and crisis intervention, as well as emotional support. This strategy considers it essential to try to have a telephone number for psychological or psychiatric emergencies and to provide care to mental health personnel (15). But it is unknown what the scope of this national strategy has been within the country, how decision makers adopted it or formulated new policies for the protection and care of people with MD on the understanding that comprehensive mental health policies must be implemented to respond to the daily healthcare needs of the people with MD, while still responding in the same way, to health emergencies, such as the current pandemic (7, 16, 17).

One way to address and support policy decision-making is through strengthening health system governance (18–20). Globally, governance in healthcare refers to the implementation of policies and practices that promote equitable health systems (21, 22). Other international organizations equate the concept of governance with stewardship, or co-management, to refer to concerted actions that promote and protect public health (23), or with an intersectoral governance approach, that refers to the coordination of multiple sectors to address health problems (24, 25). These definitions have a normative approach. In this research an approach to governance as an intermediate analytical variable is proposed, a generalizable concept, which refers to the process of agreement in decision-making, in which all the actors of the health system, suppliers and consumers intervene, with well-defined roles, to meet the demands of mental healthcare, with the focus of patient-centered care based on evidence, responsibility and accountability (25, 26). Incorporating this governance approach poses challenges for health systems in their communities, providing essential services both in the short term (after a disaster or pandemic, for example, the COVID-19) and in the long term in terms of public health. The role and critical nature of healthcare facilities means that they have significant impacts on communities, and the decisions affect the natural system in which we all live and have an impact on the future environmental. These impacts do not affect communities in the same way. Vulnerable populations such as people with MD suffer the effects on the environment due to factors such as access to resources and social determinants of health that influence health risks and outcomes. Populations with MD are less able to deal with the consequences for human health. In this sense, the approach of the Governance Analytical Framework (GAF) in the field of public health, visualizes governance as a social fact, endowed with analyzable and interpretable characteristics: the problem from a governance approach, the actors, social norms, the process, and the nodal points (27). Therefore, it will be the approach that we used.

The objective of this research is to analyze the governance process implemented in the formulation of policies for healthcare of people with mental disorders in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and methods

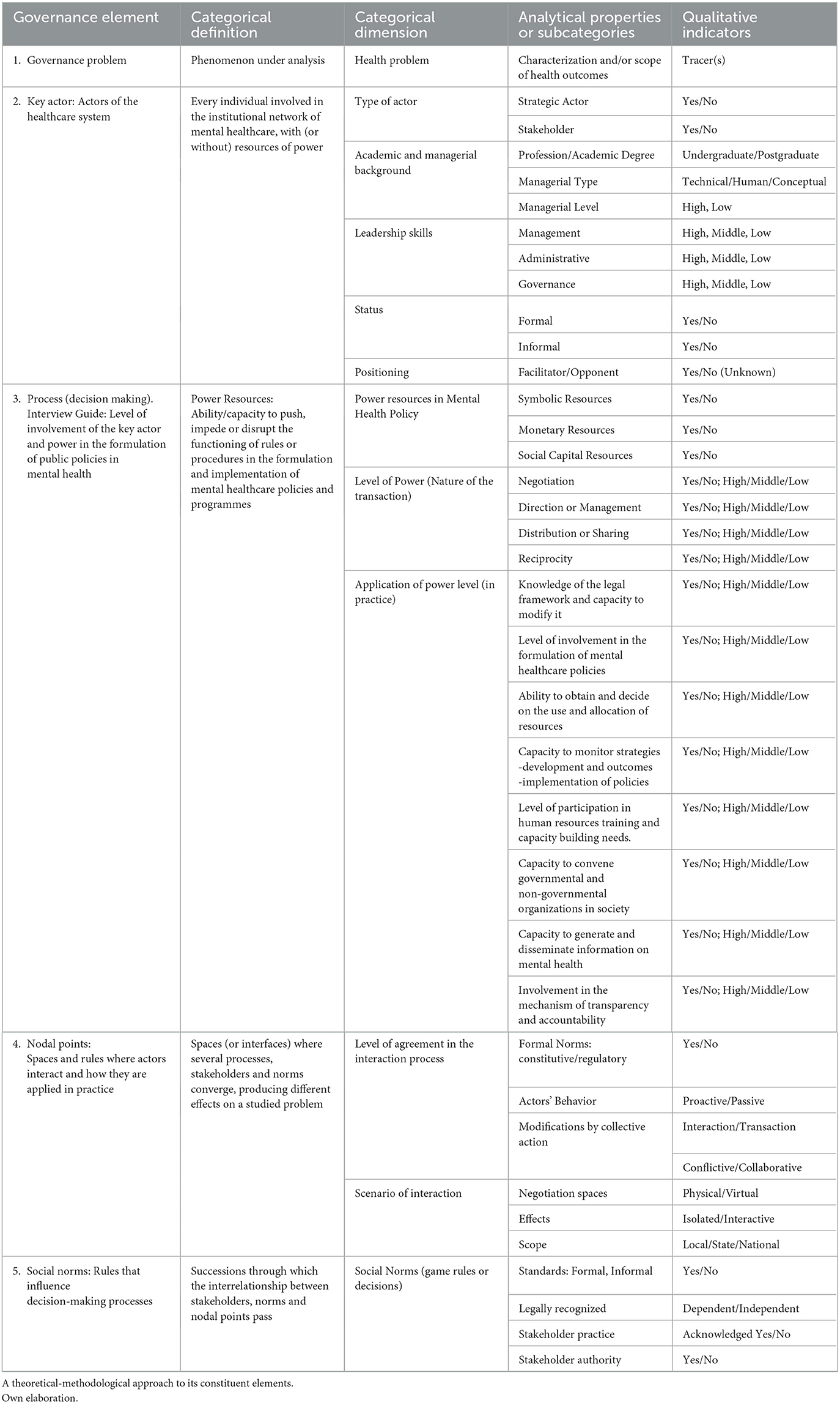

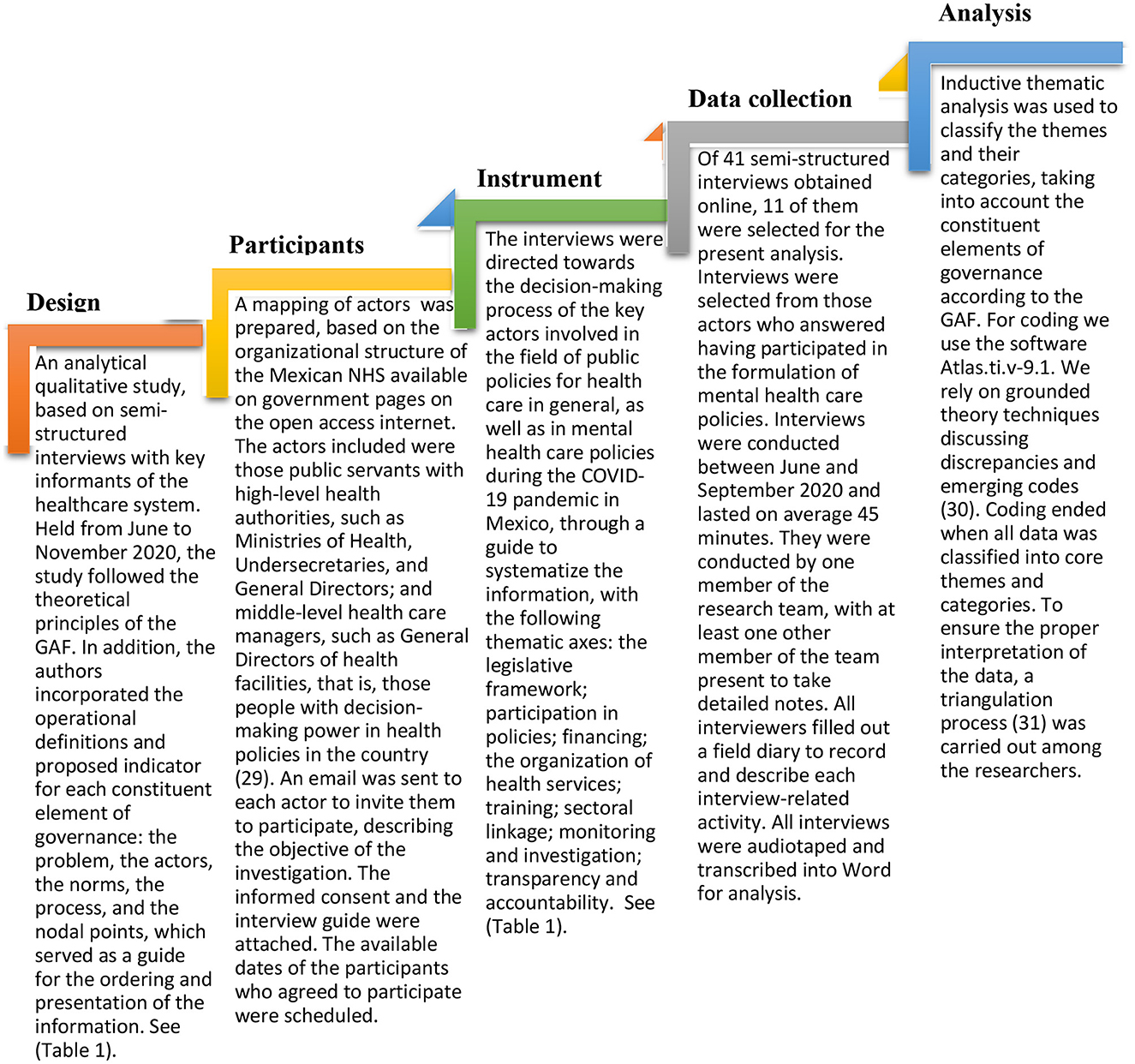

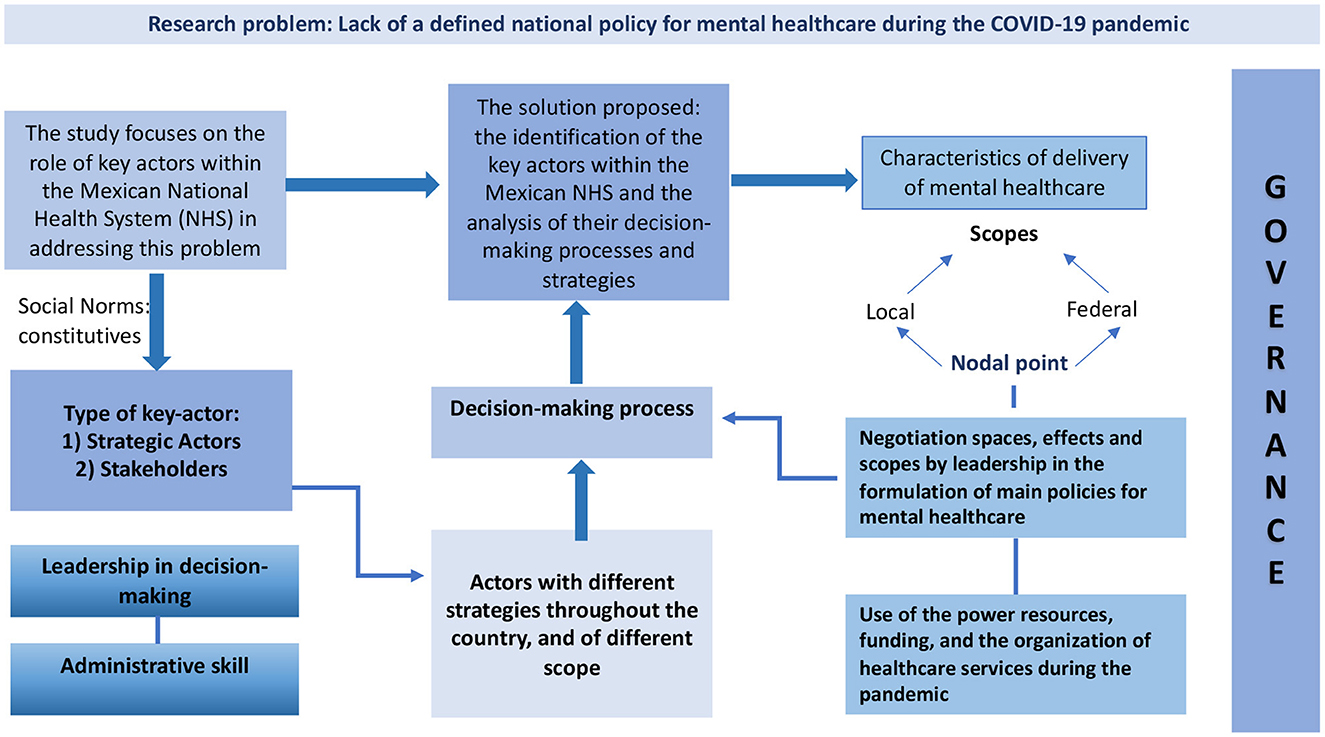

A qualitative research methodology used since the 1960s, is proposed. It is a systemic and essentially critical methodology in all its phases, from its data collection instruments to the quality criteria, such as classic validity and reliability. Given the intricate web of variables (antecedents, intervening and interacting), a critical analysis is essential throughout the research process (28). By applying this methodology, precise information is obtained on how the different social actors perceive, interact and make decisions in the formulation of policies for the care of people with MD, according to the thematic categories of analysis proposed in the GAF: the problem, the actors, the social norms, the process, and the nodal point, (see Table 1), with the method described in the Figure 1.

3. Societal benefits of the research

The results of this article allow us to observe, beyond its initial objective, some key aspects that may be of marked interest for the future responses to certain societal challenges in the field of Governance and Global Mental Health:

First, we have realized the importance of developing a comprehensive holistic model (although adaptable to the characteristics of each territory) of Global Health, encompassing a global vision of planetary challenges (32). This requires the integration of interactions between multiple actors, from both bottom-up and top-down perspectives, anchored in an integrative governance framework and supported by an interdisciplinary and intersectoral approach (33, 34).

Secondly, through this article we realize that new, more inclusive (35) and reflexive (36) governance models are necessary to face the complexity of contemporary Global Health challenges. On the one hand, inequalities affect the health and wellbeing of populations at global, regional, and national levels. An inclusive approach to governance in Global Health is a potential way to include all key actors and thus reduce inequalities (33, 35).

Finally, in a multi-actor and multi-scale environment, it is imperative to establish the foundations of a methodological framework in empirical bioethics that can serve as a starting point for building a reflective governance model in the field of Global Health. This process of ongoing critical thinking involves “mapping, framing and shaping” the dynamics of interests and perspectives that could jeopardize a collaborative scenario (36). Finally, the conclusion of this article clearly shows us the need to develop governance models in the field of Global Health with clearly defined social purposes, allowing key actors to collectively build sustainable decision-making processes, more adapted to the needs of populations and our planet.

4. Results

4.1. The problem from a governance approach

In Mexico, the SSA, as the sole governing body of the NHS, issued guidelines and recommendations for mental healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. They recommended providing continuous healthcare for the mentally ill, but no defined national policy or specific actions for such care were issued. The mental healthcare scenario included multiple actors with different strategies throughout the country, and of different scopes, depending on both the type of key actor and the characteristics that accompany their decision-making, as shown in the analysis of the interviews, according to the analytical categories.

4.2. The key actors of the Mexican NHS

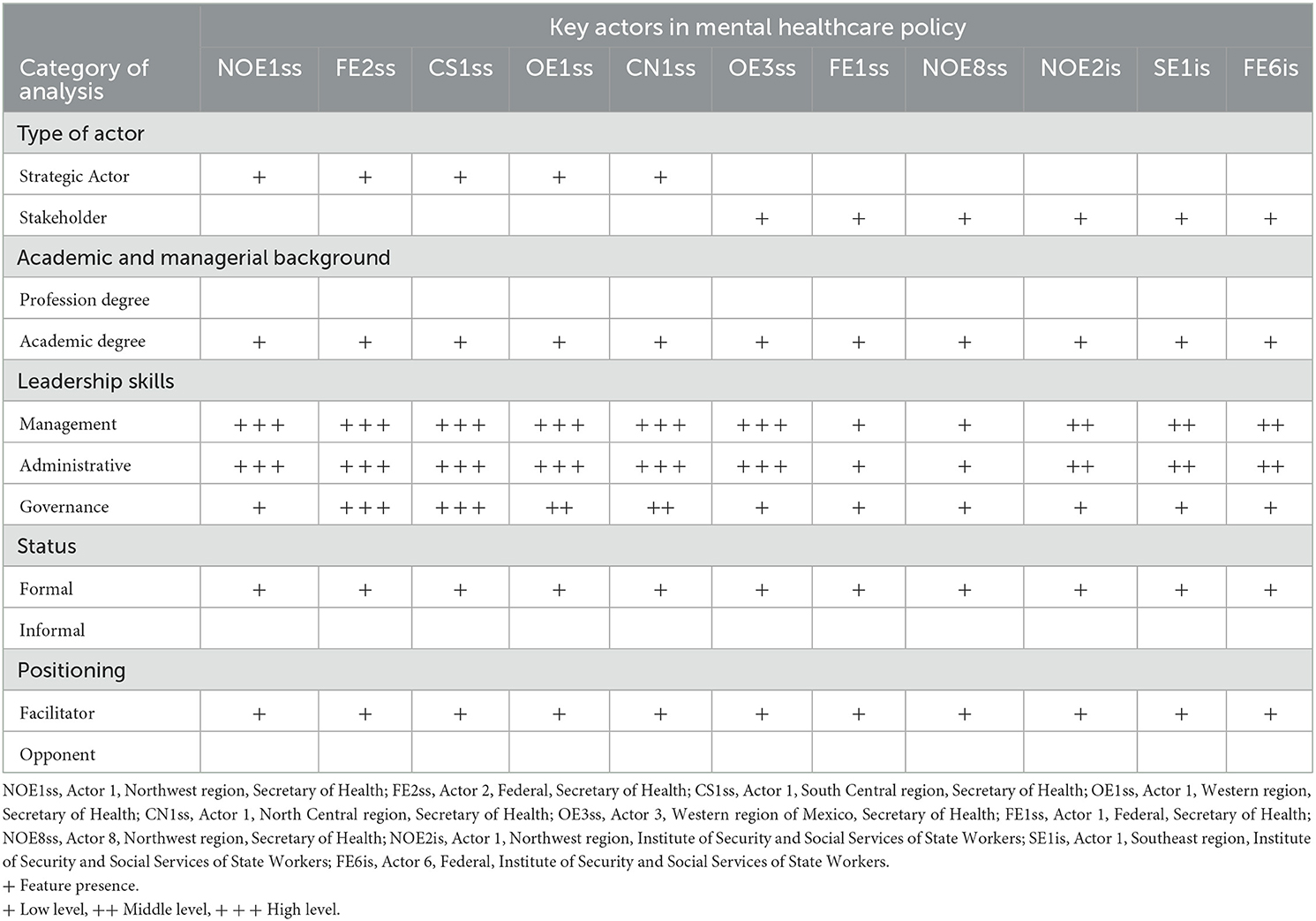

Eleven key actors of the NHS, three participants from the federal level (27%) and eight from the state level (73%), according to the other geographical regions of the country (37). The stakeholder mapping included six actors from the SESA, three actors from the ISSSTE and two actors from the SSA.

According to his position in the Mexican NHS, four actors were Ministries of Health, one Undersecretary, two General Directors, two Medical Directors, and two Medical Subdelegates. The state and federal high-level health authorities are those who participate in the policymaking. The participation of local or municipal actors was not found. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the participants.

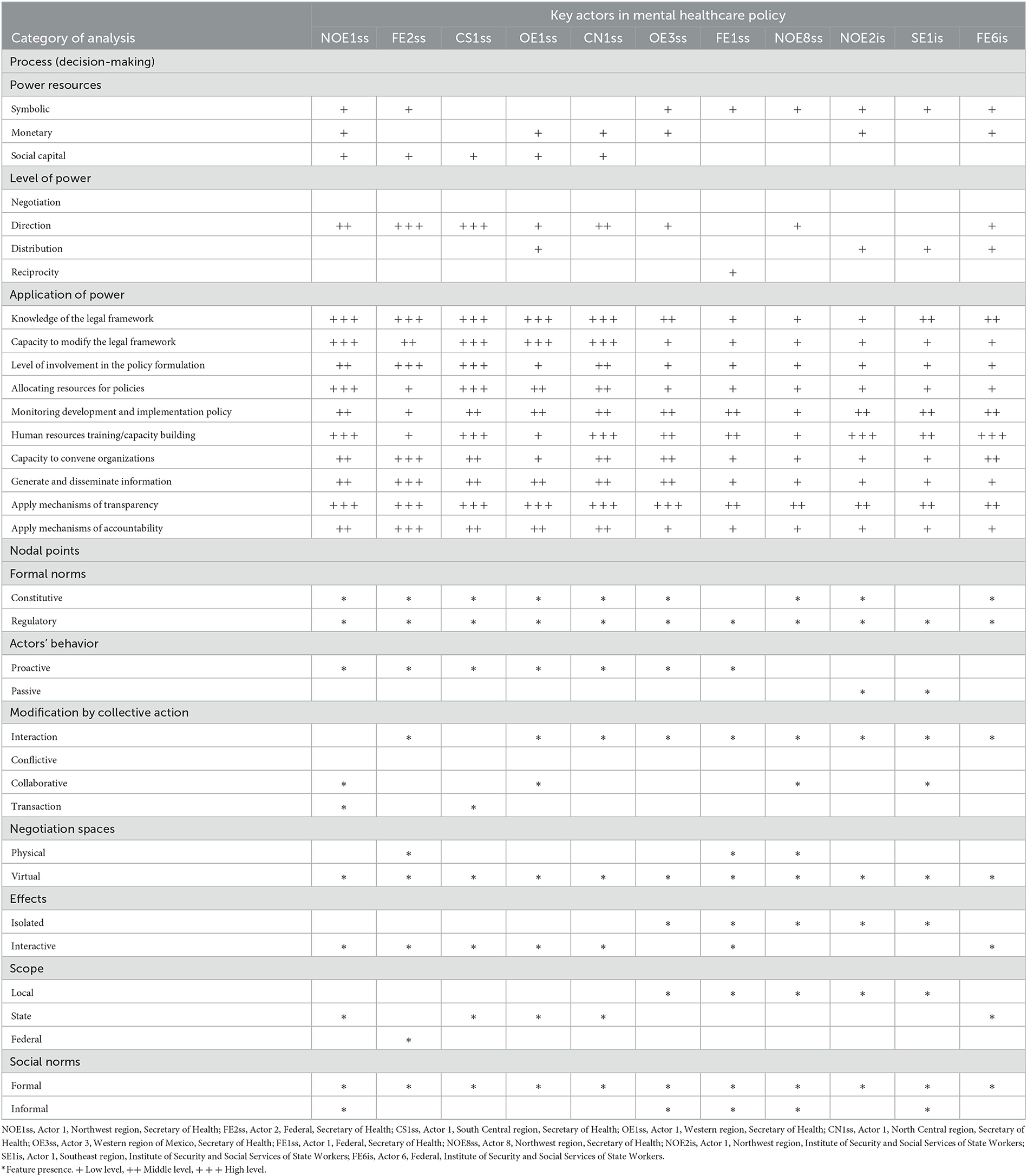

The actors recognized having leadership in the formulation of main policies. The Ministries and Undersecretaries acknowledged leadership in decision-making and in managerial skills, concerning the direction of policies in their field of competence. Directors and Medical Subdelegates, administrative skills for the development and implementation of policies were identified (see Table 3). Although all actors positioned themselves as facilitators of federal policies on mental health, it was discerned that two actors remained passive, regardless of decisions.

4.3. Decision-making process, social norms, and nodal points

The constitutive norms are the basis for the decisions of most stakeholders, who can interact and agree on the overall health decision-making process, as they are state and federal health authorities. Table 3 shows the characteristics of the actors according to the interactive decision-making process, and excerpts of interviews are presented as evidence. The Ministries identified themselves as responsible for the formulation of policies for the protection and care of people with MD and considered them within the vulnerable population group. While the directors, mentioned their actions in a more local scenario of concern, participating in internal regulations such as protocols of specific attention to COVID-19 in specialized mental health institutions:

“The regulations emanate mainly from the Mexican Constitution. Hence derived the Constitution of the State of..., the Federal Health Law, the State Health Law and the Health Sector Plan which is where we take all the elements... to be able to implement the different policies... of this secretariat.” Actor-CS1ss

“... a protocol for COVID, we were the first to do it. And yes, in that sense we are a bit of a reference. Those are the public policies to face Covid, and well, there is a national policy of restructuring the National Mental Health Program that is to invest more in primary healthcare, make the second level and we are the third level of care.” Actor-FE1ss

Decision-makers adopted different measures using power resources through transactions of different natures and scopes, targeting different population groups (see Table 3).

“... concerning mental disorders, although we have taken action, we have fallen short because of the confinement in which the population has been. We try to push some programs through health services... they have a specific area that has to do with mental health to support them through video claims...” Actor-CS1ss

“... the Health Caravans, which are mobile medical units that go to those rural communities which do not have quick access to a Health Center, and through them all those vulnerable, disabled people and those you mentioned are promoted and monitored.” Actor-OE1ss

About funding, seven of the actors expressed having the power to decide the use and allocation of resources (see Table 3).

“... here we also had to redistribute the budgets of all the items that arrive.., make a redistribution of all those funds, of the economics, to allocate them to priority actions that were going to have to do with the care of COVID and of course from the epidemiology area of each of the health regions of the hospitals' local care protocols were established to be able to define the treatment strategy...” Actor-OE3ss

Regarding the organization of healthcare services during the pandemic, to support the guidelines for action in mental health issued by the Federal Ministry of Health, most of the actors involved reported actions under a proactive and interactive behavior but of local scope:

“In the hospital we made a protocol for the management of this pandemic, among the things we required was the protective equipment for the staff, modify any of the facilities of the hospital; from toilets at the entrance to inside hospital areas, such as two special offices for potential COVID patients; we decreased the admission to 30%, and the flow of outpatient patients and made calls, that is, consultations by video call,... basically it is the follow-up of patients through electronic methods to prevent them from entering, respiratory and psychiatric triage, our two lines of attention to the public and COVID people...” Actor-FE1ss

Regarding the capacity for education and intersectoral action, some actors described high levels of participation of various sectors of activity in mental health policy formulation:

“... the National Committee for Health Safety, is a collegiate body that was established in 2002 and whose... attributions or functions are precisely to coordinate the preparation and response to phenomena... that can produce threats to health security, I have coordinated the different working groups that depend directly on me which are eight general directors... who work in coordination with us the National Center for Blood Transfusion and... Psychiatric Care Services,... and the... National Commission Against Addictions.” Actor-FE2ss

“... they gave us the task of coordinating the other institutions of the state: the IMSS, the ISSSTE, the private hospitals, the National Defense Secretariat so that through... we concentrate this information and make a report; from the clinical area we pass it to epidemiology of the Ministry of Health and... all this is the final report that is taken to the cabinet and to the office of the secretary or the governor where the decisions of public policies are made.” Actor-OE3ss

In terms of research, most actors exercised their power in capacities to control the development and implementation of health policies in general:

“We rely a lot on expert people like people from the National Institute of Public Health, people from UNAM who are developing models at the national level, we are making measurements daily to see our trends in hospital occupancy, our trends of increase in cases, lethality, mortality.” Actor-OE3ss

However, only one actor mentioned the ability to generate and disseminate mental health information:

“... we are, as a psychiatric hospital, the largest in the country and in that sense our voice is heard; we are... reference for the other hospitals, and... for... vulnerable groups, we are always in contact, they come to us here... Indigenous... beaten women, the people who are,... in street situation and patients living with... HIV, people living with these psychosocial conditions.” Actor-FE1ss

In regard to transparency and accountability, all actors expressed transparency mechanisms:

“As for the Secretariat, there are messages from the governor, from the Ministry of Health in different media, including social networks, and already in the hospital there are many posters and this kind of thing.... I don't know at the level of the Secretary of Health; I know they have a very strict level of control of resources and transparency, but I don't know if they implemented new strategies.” Actor-NOE8ss

Figure 2 summarizes the findings, explaining the research problem, the solution, and the theoretical contribution of the present study.

Figure 2. Theoretical contribution of the research: examination of the governance approach to mental healthcare during a pandemic, México, 2020.

5. Discussion

The results of this study show the heterogeneity in decision-making for the protection and care of people with mental disorders in the context of a health emergency such as the current COVID-19 pandemic. A legislative framework lacking a General Mental Health Law at the national level in Mexico, makes it unclear what actions should be taken to guarantee healthcare access for people with mental disorders, as dictated by the Magna Carta [Const.], 2021 (38). The World Health Organization, in its reports called “Mental Health Atlas”, has stated on more than one occasion the need to address the problem of mental health in a comprehensive manner (with public policies, legislation and financing). In these reports, the region made up of the United States and Canada leads the way with improved scores for the indicators regarding the enactment and updating of laws and the implementation of public policy on mental health (39).

The fact that the Mexican NHS is fragmented in terms of the structure and function of healthcare services, further intensified the problem and limited the responsiveness of decision-makers to decentralize guidelines to state and local contexts. This resulted in the implementation of diverse strategies across the country, and of varying scope, depending mainly on the resources that key actors put at stake, but generally showing a local scope of their actions with little connectivity between the different NHS settings.

Concerning mental healthcare strategies, as reported in the literature, they were more focused on clinical care in the context of the pandemic, i.e., for the population presenting symptoms associated with lockdown and social distancing (40–42), while healthcare services for people with specific MD decreased during the pandemic. Healthcare institutions found it necessary to reduce inpatient and outpatient care processes to implement processes for the detection, monitoring and surveillance of COVID-19 cases. The decline in care for people with MD conflicts with strategies recommended in the scientific literature (43, 44). Leaving these people in a scenario of increased vulnerability, as they may develop greater disease awareness and greater exposure to infectious diseases, such as COVID-19 (45), and less access to available healthcare services, may intensify pre-existing inequality (6, 9, 43).

Thus, the COVID-19 health crisis has shown that the health system in Mexico, as in most countries, was not sufficiently prepared to respond in a reliable and timely manner to the problem (46), and in the case of mental healthcare for people with MD, the problem was even more evident because the access to services became more difficult, and the alternative use of digital/telephonic services was not sufficient (9, 43, 47). Furthermore, those most in need of mental healthcare are those whose livelihoods have been made even more precarious because of social disparities, in turn, few of them will seek help because their basic needs are not met by the mental healthcare systems (9). In contrast, a study in Brazil reported that, the reorganization of healthcare services integrating mental care is necessary to provide care access and continuity of care for people with MD (42).

The fragility of governance in decision-making for the protection and care of people with MD in health crisis scenarios, is partly due to the absence of a specific legislative framework. Indeed, although mental healthcare is included in the Magna Carta, it does not make a clear reference to this type of problem. Mental healthcare service mentions that the Law will define the bases and modalities for access to health services [GLH] (48), which highlights the urgent need for such a law (49).

In the current scenario and concerning the care of people with MD, we found no evidence of any call for decision-makers to interact in decision-making spaces, much less those responsible for mental healthcare. Another aspect to consider in this pandemic context is the fact that to provide continuity of clinical care, the healthcare system could resort to telematic services, but the bill to provide legal protection to health professionals and users of these services has been canceled in Mexico (50). This absence of a legal regulatory framework can also be observed in the countries of the European Union (51–53).

On the other hand, despite the decentralization of healthcare services in Mexico, unilateral and centralized decision-making enforced during the pandemic, diminished proactive interest in participating in the actions described in the policies (54). While the NHS follows—according to key informant actors—official constitutive-regulatory norms, our analyses show leadership capacity as an essential characteristic of the decision-maker to undertake the formulated actions and a key element to strengthening healthcare system governance (55–57). Further, it is mandatory that all levels of government invest in mental healthcare, not only to offset the pandemic but also to support thriving in the future for people with MD (9, 58–60).

Strengthening governance in healthcare systems involves knowing, convening, and agreeing to make proactive decisions in the formulation of comprehensive and equitable policies, including care for the most vulnerable groups in society, such as those with MD (61). A process that requires leading decision makers with strong social values (62) to design suitable strategies to overcome the barriers to access to mental healthcare services (63). It is evident that, the sectoral and multi-scalar healthcare structure of the NHS in Mexico gives greater complexity to the analysis of the decision-making process in the field of mental healthcare, due to the interaction of multiple actors with differing interests, roles and levels of responsibility. To adapt the healthcare services to the care needs of the population in the absence of a national policy of mental healthcare, decision-makers must create an adaptative team management, with cohesion, collaboration, leadership, guidance and direction from management in providing sustained, efficient, and equitable delivery of mental healthcare for people with MD during a sanitary emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic (41).

In summary, the study shows that the lack of a national mental health law in Mexico and the fragmented structure of the healthcare system have made it difficult for decision-makers to provide adequate care for people with mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus of mental healthcare strategies has been primarily on addressing symptoms associated with lockdown and social distancing, rather than on providing care for people with specific mental disorders. This has led to a decline in access to care for people with mental disorders, which has made them more vulnerable to the pandemic. The study also highlights the need for a specific legislative framework to guide decision-making in the protection and care of people with mental disorders during health crises. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of leadership capacity and proactive decision-making in strengthening governance in the healthcare system and investing in mental healthcare to support the wellbeing of people with mental disorders in the future.

The limitations of this study include: (1) a limited sample size of key-actors, which could restrict the generalizability of the findings to the larger population of Mexico. (2) The fact that it was based on self-reported data, which could be subject to bias or inaccuracies in the recall. (3) The study only focuses on one specific aspect of governance, which may not fully capture the complexity and nuances of decision-making in the health system. (4) It is possible that the study only considered the perspectives of certain groups of actors and not others, which could limit the scope of the findings. (5) It is a qualitative study, which makes it difficult to generalize the findings. (6) The study only analyzes the situation of a particular health emergency, which makes it difficult to generalize the findings to other types of emergencies. Despite these limitations, the results of the study can be considered reliable in terms of reflecting the way decisions are typically made in the health system in Mexico.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to the informed consent with the participants, in which it was agreed that their data would not be shared apart from the research team.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Investigation of the National Institute of Psychiatry (Mexico), 17 June 2020. Protocol code CEI/C/017/2020. All participants provided valid informed consent to get involved in the study, verbally, which was recorded at the time of the interviews.

Author contributions

LDC contributed to the design, data analysis, and interpretation and writing of the first and subsequent drafts of the paper. JCSH contributed to the data analysis and interpretation and writing of the first and subsequent drafts of the paper. OOGR, EON, and MSSD contributed to the interpretation and writing of subsequent drafts of the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

We declare that the development of the research received financial support from the Consejo de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), Mexico, as part of the research project Gobernanza en políticas de salud frente a la pandemia por COVID-19 en México (Project # 313274).

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to our colleague Dr. Armando Arredondo who passed away in December 2021. Dr. Arredondo will be remembered as a remarkable pioneering researcher in health governance, an excellent professor and human being.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Palacio-Mejía LS, Wheatley-Fernández JL, Ordóñez-Hernández I, López-Ridaura R, López Gatell-Ramírez H, Hernández-Ávila M, et al. All-cause excess mortality during the Covid-19 pandemic in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. (2021) 63:211–24. doi: 10.21149/12225

2. Gallegos M, Zalaquett C, Sánchez SEL, Mazo-Zea R, Ortiz-Torres B, Penagos-Corzo JC, et al. Coping with the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the Americas: recommendations and guidelines for mental health. Interam J Psychol. (2020) 54:e1304. doi: 10.30849/ripijp.v54i1.1304

3. Coronado Martínez ME. Global health governance and the limitations of expert networks in the response to the Covid-19 outbreak in Mexico. Foro Int. (2021) 61:469–505. doi: 10.24201/fi.v61i2.2836

4. Diaz-Castro L, Cabello-Rangel H, Pineda-Antúnez C, Pérez de. León A. Incidence of catastrophic healthcare expenditure and its main determinants in Mexican households caring for a person with a mental disorder. Glob Ment Health. (2021) 8:E2. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2020.29

5. Reyes-Morales H, Dreser-Mansilla A, Arredondo-López A, Bautista-Arredondo S, Ávila-Burgos L. Análisis y reflexiones sobre la iniciativa de reforma a la Ley General de Salud de México 2019. Salud Publica Mex. (2019) 61:685–91. doi: 10.21149/10894

6. Díaz-Castro L, Cabello-Rangel H, Medina-Mora ME, Berenzon-Gorn S, Robles-García R. Madrigal-de León EÁ. Mental health care needs and use of services in Mexican population with serious mental disorders. Salud Publica Mex. (2020) 62:72–9. doi: 10.21149/10323

7. Iemmi V. Motivation and methods of external organisations investing in mental health in low-income and middle-income countries: a qualitative study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2021) 8:630–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30511-3

8. Brown LF, Kroenke K, Theobald DE, Wu J, Tu W. The association of depression and anxiety with health-related quality of life in cancer patients with depression and/or pain. Psychooncology. (2010) 19:734–41. doi: 10.1002/pon.1627

9. Cénat JM, Dalexis RD, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Mukunzi JN, Rousseau C. Social inequalities and collateral damages of the COVID-19 pandemic: when basic needs challenge mental health care. Int J Public Health. (2020) 65:717–18. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01426-y

10. Díaz de. León-Martínez L, de la Sierra-de la Vega L, Palacios-Ramírez A, Rodriguez-Aguilar M, Flores-Ramírez R. Critical review of social, environmental and health risk factors in the Mexican indigenous population and their capacity to respond to the COVID-19. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 733:139357. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139357

11. Shao Y, Shao Y, Fei JM. Psychiatry hospital management facing COVID-19: from medical staff to patients. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:947. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.018

12. Antiporta DA, Bruni A. Emerging mental health challenges, strategies, and opportunities in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives from South American decision-makers. Rev Panam Salud Publica. (2020) 44:e154. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.154

13. Fiorillo A, Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 63:e32. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35

14. Xiang YT, Zhao YJ, Liu ZH Li XH, Zhao N, Cheung T, et al. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: managing challenges through mental health service reform. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1741–44. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45072

15. de Secretaría S. Guidelines for Response and Action in Mental Health and Addictions for Psychosocial Support During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico. (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Lineamientos_Salud_Mental_COVID-19.pdf (accessed April 20, 2020).

16. Tediosi F, Lönnroth K, Pablos-Méndez A, Raviglione M. Build back stronger universal health coverage systems after the COVID-19 pandemic: the need for better governance and linkage with universal social protection. BMJ Glob Health. (2020) 5:e004020. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004020

17. Lee Y, Lui LMW, Chen-Li D, Liao Y, Mansur RB, Brietzke E, et al. Government response moderates the mental health impact of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of depression outcomes across countries. J Affect Disord. (2021) 290:364–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.050

18. AlKhaldi M, Kaloti R, Shella D, Al Basuoni A, Meghari H. Health system's response to the COVID-19 pandemic in conflict settings: policy reflections from Palestine. Glob Public Health. (2020) 15:1244–56. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1781914

19. Maor M, Howlett M. Explaining variations in state COVID-19 responses: psychological, institutional, and strategic factors in governance and public policy-making. Policy Design Practice. (2020) 3:228–41. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2020.1824379

20. World Health Organization. Strengthening Health Systems Resilience: Key Concepts and Strategies. (2020). Available online at: http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest (accessed January 25, 2023).

21. Meads G, Russell G, Lees A. Community governance in primary health care: towards an international Ideal Type. Int J Health Plann Manage. (2017) 32:554–74. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2360

22. van de Bovenkamp HM, Stoopendaal A, Bal R. Working with layers: the governance and regulation of healthcare quality in an institutionally layered system. Public Policy Adm. (2017) 32:45–65. doi: 10.1177/0952076716652934

23. Pearson B. The clinical governance of multidisciplinary care. Int J Health Governance. (2017) 22:246–50. doi: 10.1108/IJHG-03-2017-0007

24. de Leeuw E. Engagement of Sectors Other than Health in Integrated Health Governance, Policy, and Action. Ann Rev Public Health. (2017) 38:329–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044309

25. Lin X, Yang H, Wu Y, Zheng X, Xie L, Shen Z, et al. Research on international cooperative governance of the COVID-19. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:566499. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.566499

26. Díaz-Castro L, Arredondo A, Pelcastre-Villafuerte BE, Hufty M. Governance and mental health: contributions for public policy approach. Rev Saude Publica. (2017) 51:4. doi: 10.1590/s1518-8787.2017051006991

27. Hufty M. Báscolo E, Bazzani R. Gobernanza en salud: un aporte conceptual y analítico para la investigación [Governance in health: a conceptual and analytical approach to research]. Cad Saúde Pública. (2006) 22:S35–S45. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2006001300013

28. Martínez Miguelés M. Validez y confiabilidad en la metodología cualitativa. Paradigma. (2006) 27:7–33.

29. Secretaría de Gobernación. Manual of perceptions of public servants of the dependencies entities of the Federal Public Administration. (2020). Available online at: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5594049&fecha=29/05/2020 (accessed July 9, 2020).

30. Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. (2018) 24:9–18. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

31. Flick U, Kardorff E, von and Steinke I. A companion to qualitative research. London; Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications (2004).

32. Laaser U, Bjegovic-Mikanovic V, Seifman R, Senkubuge F, Stamenkovic Z. Editorial: One health, environmental health, global health, and inclusive governance: What can we do? Front Public Health. (2022) 10:932922. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.932922

33. Buss PM. De pandemias, desenvolvimento e multilateralismo. Le Monde Diplomatique. (2020). Available online at: https://diplomatique.org.br/de-pandemias-desenvolvimento-e-multilateralismo/ (accessed January 20, 2023).

34. Suarez-Herrera JC, Hartz Z, Marques da Cruz M. “Alianzas estratégicas en Salud Global: perspectivas innovadoras para una Epidemiología del Desarrollo Sostenible,” In Abeldaño-Zúñiga A, Moyado-Flores S, ed, Epidemiología del desarrollo sostenible. Córdoba: Creative Commons de Acceso Abierto (2021). p. 179–214.

35. Eliakimu ES, Mans L. Addressing inequalities toward inclusive governance for achieving one health: a rapid review. Front Public Health. (2022) 9:755285. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.755285

36. Boudreau LeBlanc A, Williams-Jones B, Aenishaenslin C. Bio-ethics and one health: a case study approach to building reflexive governance. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:648593. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.648593

37. Fouquet A. “Diferencias regionales en México: una herencia geográfica y política,” In Guzmán N, ed. Sociedad y Desarrollo en México. Monterrey: Ediciones Castillo/ITESM (2002). p. 385–402.

38. Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Articles 4 and 73. Mexico DOF. (2021). Available online at: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/CPEUM.pdf (accessed May 28, 2021).

39. World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas. (2020). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345946 (accessed December 16, 2022).

40. Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH, Zhao YJ, Zhang Q, Zhang L, et al. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1732–8. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45120

41. Cogan N, Archbold H, Deakin K, Griffith B, Sáez Berruga I, Smith S, et al. What have we learned about what works in sustaining mental health care and support services during a pandemic? Transferable insights from the COVID-19 response within the NHS Scottish context. Int J Ment Health. (2022) 51:164–88. doi: 10.1080/00207411.2022.2056386

42. Nascimento Monteiro C, Freire Sousa AA, Teles de Andrade A, Eshriqui I, Moscoso Teixeira de Mendonça J, do Lago Favaro J, et al. Organization of mental health services to face COVID19 in Brazil. Eur J Public Health. (2021) 31:iii566. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckab165.601

43. Chevance A, Gourion D, Hoertel N, Llorca PM, Thomas P, Bocher R, et al. Assurer les soins aux patients souffrant de troubles psychiques en France pendant l'épidémie à SARS-CoV-2 [Ensuring mental health care during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in France: a narrative review]. Encephale. (2020) 46:S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.03.001

44. Corruble E. A Viewpoint from Paris on the COVID-19 pandemic: a necessary turn to telepsychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. (2020) 81:20com13361. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20com13361

45. Hoşgelen EI, Alptekin K. Letter to the editor: the impact of the covid-19 pandemic on schizophrenia patients. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. (2021) 32:219–21. doi: 10.5080/u26175

46. McMahon M, Nadigel J, Thompson E, Glazier RH. Informing Canada's health system response to COVID-19: priorities for health services and policy research. Healthc Policy. (2020) 16:112–24. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2020.26249

47. Duden GS, Gersdorf S, Trautmann K, Steinhart I, Riedel-Heller S. Stengler K. LeiP#netz 20: mapping COVID-19-related changes in mental health services in the German city of Leipzig. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2022) 57:1531–41. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02274-2

48. Ley General de Salud [LGS]. Article 73. Mexico City. DOF (2021). Available online at: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5635916&fecha=22/11/2021#gsc.tab=0 (accessed November 22, 2021).

49. Becerra-Partida OF. Mental health in Mexico, a historical, legal and bioethical perspective. Person Bioethics. (2014) 18:238–53. doi: 10.5294/pebi.2014.18.2.12

50. Secretaría de Gobernación. Notice of Cancellation of the Draft Mexican Official Standard PROY-NOM-036-SSA3-2015. (2018). Available online at: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5521060&fecha=27/04/2018 (accessed April 27, 2018).

51. Gil Membrado C, Barrios V, Cosín-Sales J, Gámez JM. Telemedicine, ethics, and law in times of COVID-19. A look towards the future. Rev Clin Esp. (2021) 221:408–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rceng.2021.03.002

52. Parimbelli E, Bottalico B, Losiouk E, et al. Trusting telemedicine: A discussion on risks, safety, legal implications and liability of involved stakeholders. Int J Med Inform. (2018) 112:90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.01.012

53. Raposo VL. Telemedicine: The legal framework (or the lack of it) in Europe. GMS Health Technol Assess. (2016) 12:Doc03. doi: 10.3205/hta000126

54. Greer SL, Wismar M, Figueras J. Strengthening Health System Governance. Better policies, stronger performance. London: Open University Press McGraw-Hill Education. (2016).

55. Connolly J. The “wicked problems” of governing UK health security disaster prevention: the case of pandemic influenza. Disaster Prev Manag. (2015) 24:369–82. doi: 10.1108/DPM-09-2014-0196

56. Machado de. Freitas C, Vida Mefano e Silva I, da Cunha Cidade N. Debating ideas: The COVID-19 epoch: Interdisciplinary research towards a new just and sustainable ethics. Ambient Soc. (2020) 23:1–12. doi: 10.1590/1809-4422asoceditorialvu2020l3ed

57. Moon MJ. Fighting COVID-19 with agility, transparency, and participation: wicked policy problems and new governance challenges. Public Adm Rev. (2020) 80:651–6. doi: 10.1111/puar.13214

58. Palmer AN, Small E. COVID-19 and disconnected youth: lessons and opportunities from OECD countries. Scand J Public Health. (2021) 49:779–89. doi: 10.1177/14034948211017017

59. Nhamo L, Ndlela B. Nexus planning as a pathway towards sustainable environmental and human health post Covid-19. Environ Res. (2021) 192:110376. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110376

60. Wang Y, Hao H, Platt LS. Examining risk and crisis communications of government agencies and stakeholders during early-stages of COVID-19 on Twitter. Comput Human Behav. (2021) 114:106568. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106568

61. Vilar-Compte M. Hernández-F M, Gaitán-Rossi P, Pérez V, Teruel G. Associations of the COVID-19 pandemic with social well-being indicators in Mexico. Int J Equity Health. (2022) 21:74. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01658-9

62. Plamondon KM, Pemberton J. Blending integrated knowledge translation with global health governance: an approach for advancing action on a wicked problem. Health Res Policy Syst. (2019) 17:24. doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0424-3

63. Fauk NK, Ziersch A, Gesesew H, Ward P, Green E, Oudih E, et al. Migrants and service providers' perspectives of barriers to accessing mental health services in South Australia: a case of African migrants with a refugee background in South Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:8906. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18178906

Keywords: governance, policy-makers, mental disorders, decision-making, public policy

Citation: Diaz-Castro L, Suarez-Herrera JC, Gonzalez-Ruiz OO, Orozco-Nunez E and Sanchez-Dominguez MS (2023) Governance in mental healthcare policies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Front. Public Health 11:1017483. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1017483

Received: 12 August 2022; Accepted: 13 February 2023;

Published: 06 March 2023.

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Babatunde Akinwunmi, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United StatesVishal Dagar, Great Lakes Institute of Management, India

Copyright © 2023 Diaz-Castro, Suarez-Herrera, Gonzalez-Ruiz, Orozco-Nunez and Sanchez-Dominguez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lina Diaz-Castro, ZHJhbGFpbmRpYXoubGRAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: Lina Diaz-Castro orcid.org/0000-0002-9123-8641

Lina Diaz-Castro

Lina Diaz-Castro Jose Carlos Suarez-Herrera2

Jose Carlos Suarez-Herrera2 Oscar Omar Gonzalez-Ruiz

Oscar Omar Gonzalez-Ruiz Emanuel Orozco-Nunez

Emanuel Orozco-Nunez Mario Salvador Sanchez-Dominguez

Mario Salvador Sanchez-Dominguez