- 1College of Health Sciences, University of Michigan-Flint, Flint, MI, United States

- 2Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 3Department of Behavioral Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Michigan-Flint, Flint, MI, United States

Objective: To review satisfaction with telehealth among children and adolescents based on their own opinions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: In the PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Embase databases, we searched for peer-reviewed studies in English on satisfaction with telehealth among children and adolescents (rather than parents). Both observational studies and interventions were eligible. The review was categorized as a mini review because it focused on the limited time frame of the COVID-19 pandemic. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Reviewers extracted information from each study and assessed risk of bias.

Results: A total of 14 studies were eligible. Studies were conducted in Australia, Canada, Italy, Israel, Poland, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They focused on a variety of health conditions. Two of the 14 studies were interventions. Participants expressed high satisfaction with video and telephone visits and home telemonitoring while also preferring a combination of in-person visits and telehealth services. Factors associated with higher satisfaction with telehealth included greater distance from the medical center, older age, and lower anxiety when using telehealth. In qualitative studies, preferred telehealth features among participants included: a stable Internet connection and anonymity and privacy during telehealth visits.

Conclusion: Telehealth services received favorable satisfaction ratings by children and adolescents. Randomized-controlled trials on the effectiveness of pediatric telehealth services compared to non-telehealth services may assess improvements in satisfaction and health outcomes.

1. Introduction

The use of telehealth increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (1). One telehealth definition is “the delivery of healthcare services, where distance is a critical factor, by all healthcare professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, and treatment and prevention of disease” (2). Synchronous telehealth care involves a live visit with a medical provider using video conferencing or a telephone call (3). Asynchronous telehealth includes the use of email, text messaging, and patient portals for the exchange of information (3). Remote monitoring involves receiving vitals and photographs from a patient for a certain health condition thus allowing for diagnosis and treatment (3, 4).

In pediatric care, telehealth was delivered through video and/or telephone consultations (5). It involved remote patient monitoring such as performing a bilateral smartphone otoscopy for the child at home (6) and measuring blood glucose levels at home and reporting the readings on a mobile application (7). Present-day Internet bandwidth (i.e., Internet speed/capacity) allows for video visits and remote monitoring without technological issues. Limited access to high-speed Internet for rural residents and those of lower socio-economic status, however, may increase barriers to quality remote healthcare (8).

Prior research focused on satisfaction with telehealth among adult patients and/or parents. In these studies of adult patients or parents, participants indicated technological issues such as the lack of a stable/fast Internet connection (9), lack of in-person interaction with the medical provider (10, 11), and lower empathy in care (11) as areas of concern. Parents who received care through in-person visits were more satisfied in the area of emotional support compared to those who received remote consultations (p = 0.039) (12).

In surveys, adolescents viewed themselves as technologically savvy and expressed a preference for technologically-enhanced interaction and learning (13). Telehealth may offer young people opportunities for enhanced medical experiences through telehealth. Understanding satisfaction with telehealth among young people (i.e., children and adolescents) can help develop healthcare improvements that meet the needs of youth.

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review assessed satisfaction with telehealth among children and/or adolescents who offered their own opinions during the COVID-19 pandemic. A systematic review on randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) discovered high satisfaction with telehealth among parents and patients combined prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (14).

Our study conducted a systematic literature review on the satisfaction with telehealth among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic. It included studies where children and/or adolescents, rather than parents, answered questions on their satisfaction with telehealth. We classified the study as a mini review because it focused on a defined period of time (the COVID-19 pandemic), sought to provide succinct findings, offered recommendations for medical providers and healthcare administrators on preferred features of telehealth according to the suggestions by adolescents, and provided suggestions for future research.

2. Methods

2.1. Research question, review design, and eligibility criteria

The review question was: What is the satisfaction of young people (i.e., children and adolescents) with telehealth? We sought to follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 (15) for this registered review (16). The PI (E) COS structure was:

• Outcome: Satisfaction.

• Participants: Pediatric participants who could answer items on their own, i.e., primarily adolescents. Younger children who answered questions on their own were also included. Studies that mixed children/adolescents and young adults in one category were included.

• Intervention/Exposure: Telehealth.

• Comparison group: Not required.

• Time frame: COVID-19 pandemic.

2.1.1. Language

The inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed studies with full-text in English.

2.1.2. Study designs

Due to the limited number of studies, we did not place restrictions on study design. The PRISMA guidelines describe: “PRISMA primarily focuses on the reporting of reviews evaluating the effects of interventions, but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews with objectives other than evaluating interventions” (15). All intervention designs were included. Observational cross-sectional, cohort, and case–control studies involving surveys and interviews were included. If the study did not specifically list the type of design used, decisions were made on the type of design based on descriptions in the article.

2.1.3. Health conditions

Participants could be receiving services for and/or have any physical or mental health condition in this review.

2.1.4. Time frame

Given that search words for the COVID-19 pandemic were utilized, the search was not restricted by date. The search was performed on December 15, 2022. Any studies, therefore, meeting the inclusion published by December 15, 2022 were included. The study had to specify that it focused on the period of the COVID-19 pandemic to be included.

2.1.5. Participants

Keywords related to the participants in the search in the databased included pediatrics, pediatric, child, adolescent, and teen.

2.1.6. Intervention/Exposure

No restriction on the type of telehealth was placed. Synonyms for the exposure in the search in the databases included: telehealth, telemedicine, remote consultation, and video consultation.

2.1.7. Intervention/Exposure comparator

There was no requirement that the study should have a comparison group for in-person or other medical services.

2.1.8. Outcome

Synonyms of the outcome in the search included satisfaction, attitudes, and perceptions. Studies that developed their own measurements and those with reliable and/or valid and/or other measurements on satisfaction were included.

2.1.9. Databases, search strategy, synonyms of keywords

The literature review was performed in the PubMed, CINAHL (housed in EBSCO), EMBASE, and PsycINFO (housed in EBSCO) databases. It is recommended that to ensure search strings are reproducible, researchers collaborate with librarians (17). The search strings were developed with the guidance of a librarian from the University of Michigan library whose name was included in the Acknowledgments. In each database, the sets of words in Supplementary file S1 were used. Several of the search words (i.e., patient satisfaction, pediatrics, child, adolescent, telemedicine, remote consultation, and COVID-19) were entered as MeSH words in the PubMed database meaning that the database included its own associated synonyms. For example, the word telemedicine has the following synonyms as a MeSH term: telehealth, mobile health, tele-ICU, tele-intensive care, tele-referral, virtual medicine, eHealth, and mHealth.

2.2. Data extraction and synthesis

All resulting articles were uploaded into EndNote where automated removal of duplicates took place. The authors removed any remaining duplicates in Excel. Two authors (GDK and TC) reviewed all remaining titles and abstracts for inclusion in the review. The two reviewers resolved disagreements on inclusion after discussing the full-text of the article.

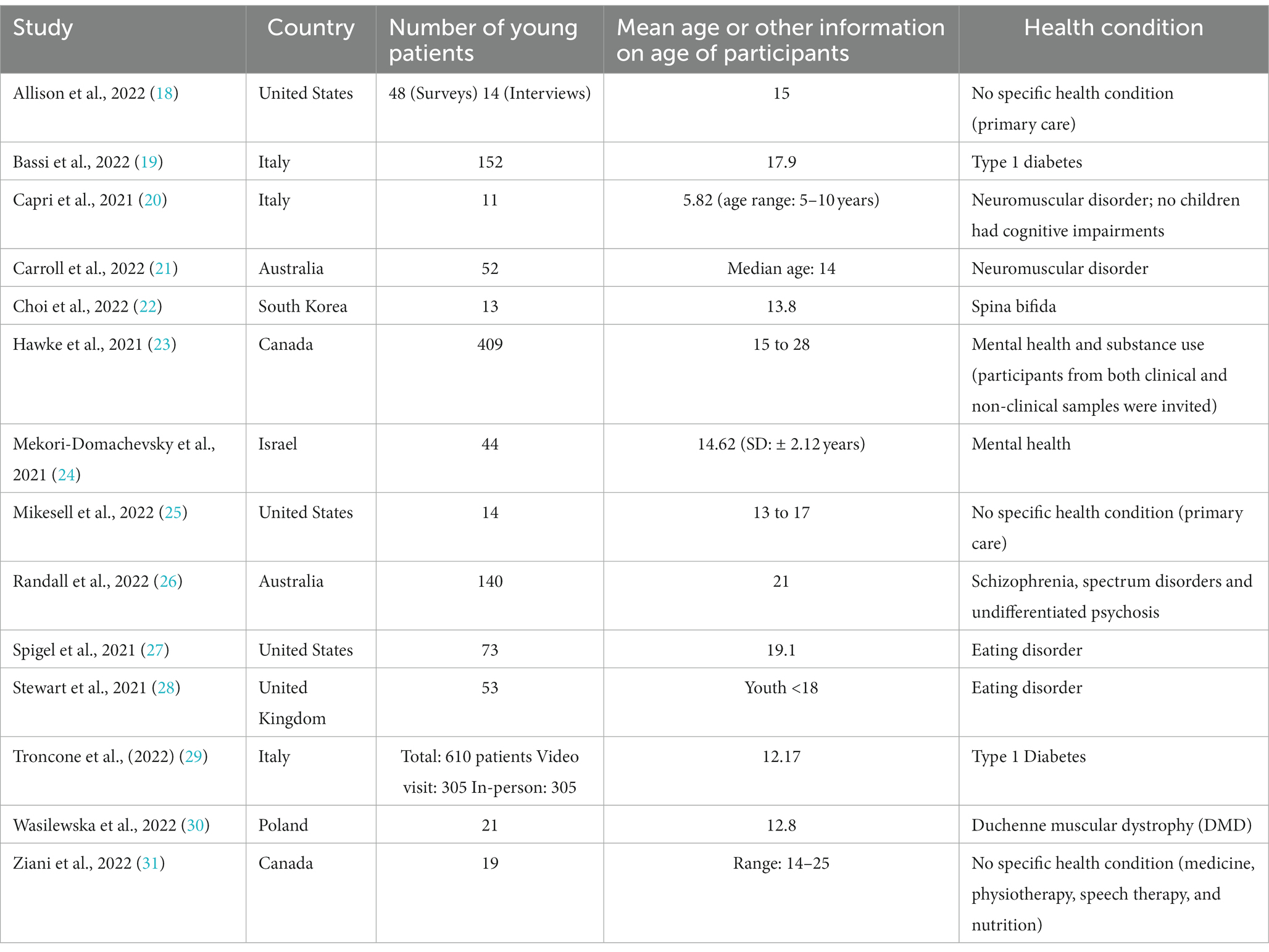

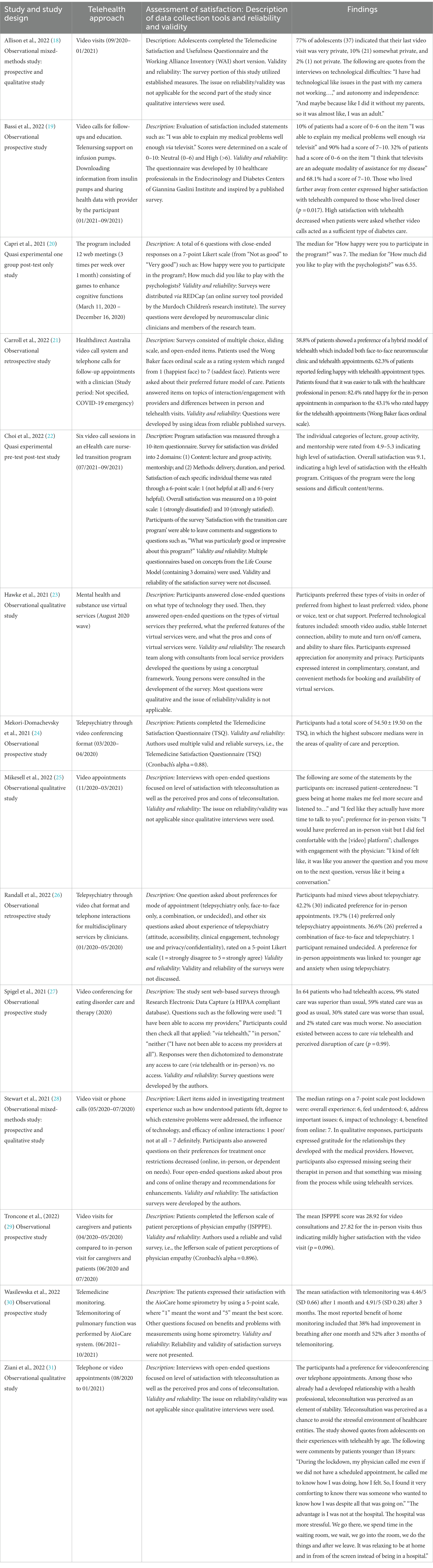

Characteristics of each included study were extracted in Tables 1, 2. Results that represented the overall study findings were extracted. BK and SA performed the data extraction in tables. GDK reviewed the data extraction. BK, SA, and GDK then all reviewed the extracted data and resolved disagreements through consensus.

Table 1. Location, number, age, and condition among participants in the 14 included studies on satisfaction with telehealth among children and adolescents based on their own opinions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2. Telehealth approach, assessment of satisfaction, and findings in the 14 included studies on satisfaction with telehealth among children and adolescents based on their own opinions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.3. Quality of evidence/risk of bias

The JBI critical appraisal tools (32) aided in assessing the quality of evidence in studies.

To assess particular limitations of studies, the review involved answering questions across study type based on JBI forms (32). Reviewers used separate forms to answer the following JBI questions:

• Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined?

• Were the socio-demographic characteristics of participants described in detail?

• Was the time period (such as months and years) for telehealth services clearly defined?

• Were satisfaction measures valid and reliable?

• Were appropriate statistical/qualitative analyses used?

BK and SA first separately assigned risk of bias scores. GDK reviewed the scores, and BK, SA, and GDK resolved disagreements through consensus. A score of 1 indicated Yes, a score of 0.5 indicated Partially, and a score of 0 meant No or Unclear on the JBI form questions. Higher total scores meant lower risk of bias and lower total scores meant elevated risk of bias.

3. Results

3.1. Literature search

The Supplementary file S2 Figure illustrates the flow of selecting articles. The number of final studies included in this review was 14 (18–31). An example of a study that was excluded during the full-text review was the study of Elbin et al., 2022 (33) on the satisfaction with telehealth among adolescents prior to the pandemic. Another example of an excluded study during the full-text review included the study of Graziano et al., 2021 (34) where satisfaction of participants was presented together without differentiating between satisfaction between youth and parents.

3.2. Study characteristics

Studies were conducted in Italy (19, 20, 29), the United States. (18, 25, 27), Australia (21, 26), and Canada (23, 31) (Table 1). In addition, one study was conducted in each of these nations: South Korea (22), Israel (24), the United Kingdom (28), and Poland (30). Studies focused on a variety of health conditions such as general medicine, eating disorder, type 1 diabetes, mental health, and speech impairment (Table 1).

3.3. Quality and risk of bias assessment

3.3.1. Study design

Among the 14 studies, there were 2 interventions (20, 22) (Table 2). Five were prospective cohort investigations where investigators classified individuals as participating in telehealth services and then followed them over time to assess their satisfaction (19, 24, 27, 29, 30). Two studies used retrospective analyses where answers to satisfaction surveys among individuals participating in telehealth at certain time periods in the past were assessed (21, 26). Three studies were observational qualitative (23, 25, 31). Two observational mixed-methods studies utilized both satisfaction surveys and qualitative interviews (18, 28).

3.3.2. Outcome variable (i.e., satisfaction) reliability/validity

The authors used reliable and valid surveys (Table 2), such as the Jefferson scale of patient perceptions of physician empathy (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.896) (29). The Telemedicine Satisfaction Questionnaire (TSQ) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88) and the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92 for the long version; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89 for the WAI short version) were utilized (18, 24). Other authors developed the surveys themselves with or without the collaboration of consultants specializing in telehealth (19, 20, 22, 23, 27, 28).

3.3.3. Quality of evidence scores based on JBI critical assessment tool common questions

Total scores among the 14 studies were distributed as follows: three had the highest quality of evidence score of 5 out of 5, two had a score of 4.5, five had a score of 4, three had a score of 3.5, and one had a score of 3 (Supplementary Table S2). Reasons for decreased scores included: limited description of the socio-demographic characteristics of the subjects and lack of valid and reliable measures of satisfaction.

3.4. Satisfaction with telehealth

3.4.1. High satisfaction overall and factors associated with higher satisfaction

Participants tended to express high satisfaction with telehealth. For example, 85% of participants were able to relay their medical problems comfortably and felt that they received appropriate attention from the healthcare professionals during video visits in the study of Bassi et al. (19). In one study, for participants, who already had a relationship with a health professional, teleconsultation was perceived as a chance to circumvent the more stressful setting of healthcare entities (31). In the study of Troncone et al. (29), the mean Jefferson Scale of Perceptions of Physician Empathy (JSPPPE) score was 28.92 for video consultations and 27.82 for the in-person visits demonstrating slightly higher satisfaction with the video visit which was not statistically significant (p = 0.096) (30). Factors associated with higher satisfaction with telehealth included: longer distance from the health center (19), older age (26), and lower anxiety when using telehealth (26).

3.4.2. Advantages of telehealth

Advantages of telehealth according to the participants included being comforting and less stressful, according to the findings of a qualitative study (31). Participants noted an increase in person-centeredness, specifically in their providers’ attentiveness and eye contact during their visit (25). The following were positive statements by adolescent patients on increased patient-centeredness through video visits: “I guess being at home makes me feel more secure and listened to” and “I feel like they actually have more time to talk to you” (25).

3.4.3. Preferred telehealth features

In order of highest to least preferred, participants favored: video, phone, or voice, text, or chat support (23). Preferred technological features among participants included: stable Internet connection, ability to mute and turn on/off camera, and ability to share files. Participants expressed appreciation for anonymity and privacy. They preferred convenient methods for booking and increased availability of virtual services (23). Some participants wanted a combination of in-person and telehealth care. Specifically, 58.8% of participants demonstrated a preference of a hybrid model of telehealth which included both in-person and telehealth appointments (21).

3.4.4. Surveying of very young patients

Investigators were able to survey participants as young as 5 (age range 5 to 10 years) by asking simple questions that included the use of a scale of happy faces. The median for “How much did you like to play with the psychologists?” was 6.55 (out of 7) (20).

3.4.5. Challenges with telehealth

In some studies, participants expressed that it was easier to communicate with the medical provider during in-person compared to telehealth appointments because of being able to develop better rapport with the physician when in the same room. In the study of Carroll et al., 2021, using the Wong Baker faces ordinal scale, 82.4% rated happy for the in-person appointments in comparison to the 43.1% who rated happy for the telehealth appointments (21). In another study, 42.2% of participants indicated a preference for in-person appointments (26). Using qualitative responses, participants expressed missing seeing their therapist in person (28). In yet another qualitative investigation, the following were statements by adolescent patients on the preference for in-person visits: “I would have preferred an in-person visit but I did feel comfortable with the [video] platform” and the challenges with engaging the physician during video visits: “… It was like you answer the question and you move on to the next question, versus like it being a conversation” (25). Another quote by a young patient relating to the preference for in-person visits was: “… I prefer face-to-face because I find that it is always more concrete personally. And I think it’s always easier when it’s in person. … I think there’s a human side to it too because I think at the moment we are a bit lacking because of the COVID” (31).

Technological problems also made telehealth appointments challenging. Participants stated: “It’s different, of course, the sound quality. … Because you do not hear as well as on Zoom as you do in an in-person session. So I find it a disadvantage” (31) and “I have had technological like issues in the past with my camera not working ….” (18).

4. Discussion

4.1. Primary findings

The reviewed studies in this literature review presented the satisfaction of children and/or adolescents separately/distinctly from parents. Studies primarily included adolescents (either exclusively or combined with young adults) but one included patients as young as 5 years (20). They focused on a variety of pediatric care needs and specialties. Studies usually defined telehealth as video/telephone consultations/educational sessions or home telemonitoring. Two of the 14 studies were interventions (20, 22). In the current review, a trend of overall high satisfaction with telehealth existed although participants also expressed a preference for a mixture of in-person and virtual visits. Prior literature reviews did not explicitly focus on satisfaction with telehealth among children and/or adolescents (35–39).

In most studies in this review, participants answered questions on their experience with telehealth without comparing it to their experience with in-person visits. In one study, the authors did compare telehealth to in-person visits and discovered higher satisfaction with video visits compared to in-person visits among adolescents which was not statistically significant (27). The trend for superior satisfaction with telehealth encounters compared to in-person appointments was similar to the results of a pre-pandemic RCT (33). In the pre-pandemic RCT, 93% of adolescents rated the telehealth visit as enjoyable compared to 86% of adolescents in the in-person visit (33). The pandemic study (29) included in this review and the pre-pandemic study (33) did not assess potential reasons for adolescents’ preferences.

4.2. Limitations of the reviewed studies

A non-randomized design, small sample size, limited generalizability, convenience sampling, sampling from both clinical and non-clinical populations without presenting separate findings for the two, limited information on socio-demographic characteristics among participants, and lack of reliable and valid satisfaction assessment tools were limitations. Another limitation was that because the number of adolescents who could answer questions on their own was small, results for young adults aged 18–28 and adolescents were sometimes mixed. Most studies examined satisfaction with video conferencing.

4.3. Limitations of this review

Only peer-reviewed articles written in English were included. Additional manuscripts may have been published after the search date. Articles housed only in other databases would not be included in this review. Although MeSH terms (library terms that also search for main synonyms) were used as part of the search, additional synonyms of keywords may have resulted in more eligible studies. The results may not be applicable to developing countries. Yet another limitation is that the different study designs and measurements did not allow for the conduct of a meta-analysis.

4.4. Implications for practice

Participants preferred in-person appointments in some of the studies. In prior research, parents believed that a physical examination resulted in enhanced treatment adherence (12). To address the concern related to the lack of a physical examination, use of virtual stethoscopes, pulse oximeters, and home spirometry devices may complement a virtual visit (40). A program where patients can loan these devices to aid physical examinations may reduce socio-economic disparities in telehealth treatment outcomes among patients (41).

In qualitative responses, participants expressed a preference for virtual appointments without technological problems. Providers should seek to eliminate any technical issues on their end. Technological problems may be due to the slower Internet speed among youth of lower incomes. Disparities in access to and quality of telehealth exist (42–48). In the 2021 National Survey Trends in Telehealth Use in the United States, where 33.1% of participants were parents/caregivers, among telehealth users, the highest share of visits that used video took place among those earning at least $100,000 (68.8%) and non-Latino White individuals (61.9%). Video visits were lowest among those without a high school diploma, non-Latino Asian, and non-Latino Black individuals (42). In a study of pediatric telehealth in Chicago, incomplete video visit rates were associated with lower broadband access (43). To enhance satisfaction, increasing access to reliable Internet services and technological devices will be valuable. The Connected Care Pilot Program in the United States. is one example that seeks to cover expenses related to broadband connectivity and network equipment in selected pilot locations to decrease inequities in access to technology (49).

In a qualitative study of patients as young as 15 years, participants expressed appreciation for anonymity and privacy during telehealth appointments (23). Anonymity and privacy can be especially important to adolescents who are starting to have their own remote visits and spend time alone with the healthcare provider. In large households, anonymity and privacy can be problematic when participating in virtual appointments. Strategies to promote anonymity and privacy include medical providers asking adolescents to move to a private space or type questions and answers and asking others to leave the room (50). Independent telehealth use (without the presence of a parent) was conceptualized by referring to the “Conceptual framework of early adolescence” (51) as a strategy to help adolescents develop self-efficacy and thoughtful decision-making abilities (18).

4.5. Implications for future research

Much research focused on satisfaction with telehealth among parents and medical providers (34, 52–61). Research on satisfaction with telehealth among children and adolescents, especially per country, is very limited. Even younger patients as young as 5 (median age 5 to 10 years) can be interviewed through asking simple questions (20). Future research may assess reasons why young patients prefer certain characteristics of telehealth or in-person visits. Investigating differences in satisfaction among socio-demographic, cultural, and linguistic groups of children and adolescents is another needed area of study. Future studies may compare satisfaction among children and adolescents based on residence in rural and urban areas with a special emphasis on whether a fast/stable Internet connection is available. They may assess the effectiveness of telehealth compared to in-person services on satisfaction, quality of life, and health outcomes among youth. Parents expressed a preference of using video compared to in-person consultations for their children and adolescents due to the fear of contracting COVID-19 in past qualitative research during the pandemic (62). Future interviews with adolescents may ask regarding preferences for using remote compared to in-person care following the COVID-19 pandemic when fear of contracting a virus may not be as elevated. Based on the “Conceptual framework of early adolescence (18, 51),” an innovative area of research is to investigate how independent telehealth use affects adolescent’s self-efficacy.

4.6. Conclusion

Young people expressed high levels of satisfaction with telehealth while also preferring a combination of in-person and telehealth services. They realized the benefit of being in the same room with the medical provider. The systematic review offered recommendations for improving telehealth services specifically using video visits instead of telephone visits, enhancing technology connectivity quality, increasing availability of telehealth appointments, and ensuring anonymity and privacy for adolescents during telehealth appointments. Future RCTs, developed with the suggestions by children and adolescents, may improve satisfaction with telehealth and health outcomes.

Author contributions

GDK conceived and designed the study. TC searched databases and removed duplicates. GDK, TC, SA, and BK reviewed abstracts and full-text articles. GDK, BK, and SA extracted data. GDK, BK, and SA performed risk of bias analysis. GDK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GDK, TC, BK, and SA reviewed and modified manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The GDK received the Frances Willson Thomson Fellowship by the University of Michigan-Flint to conduct research in the area of pediatric telehealth.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to Emily Newberry, Senior Associate Librarian, University of Michigan-Flint for guiding the development of the search strings for the four databases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1145486/full#supplementary-material

References

1.Koonin, LM, Hoots, B, Tsang, CA, Leroy, Z, Farris, K, Jolly, T, et al. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January–March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2020) 69:1595–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a3

2.WHO Group Consultation on Health Telematics. (1997) Geneva, Switzerland: A health telematics policy in support of WHO's health-for-all strategy for global health development: Report of the WHO Group consultation on health telematics, 11–16 December, Geneva, 1997. World Health Organization. (1998). Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63857 (Accessed December 15, 2022).

3.Mechanic, OJ, Persaud, Y, and Kimball, AB. (2021). Telehealth systems. StatPearls Publishing. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459384/?report=classic (Accessed December 15, 2022).

4.de Farias, FAC, Dagostini, CM, de Bicca, YA, Falavigna, VF, and Falavigna, A. Remote patient monitoring: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. (2020) 26:576–83. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0066

5.Fleischman, A, Hourigan, SE, Lyon, HN, Landry, MG, Reynolds, J, Steltz, SK, et al. Creating an integrated care model for childhood obesity: a randomized pilot study utilizing telehealth in a community primary care setting. Clin Obes. (2016) 6:380–8. doi: 10.1111/cob.12166

6.Erkkola-Anttinen, N, Irjala, H, Laine, MK, Tähtinen, PA, Löyttyniemi, E, and Ruohola, A. Smartphone otoscopy performed by parents. Telemed J E Health. (2019) 25:477–84. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0062

7.Di Bartolo, P, Nicolucci, A, Cherubini, V, Iafusco, D, Scardapane, M, and Rossi, MC. Young patients with type 1 diabetes poorly controlled and poorly compliant with self-monitoring of blood glucose: can technology help? Results of the i-NewTrend randomized clinical trial. Acta Diabetol. (2017) 54:393–402. doi: 10.1007/s00592-017-0963-4

8.Tomines, A. Pediatric telehealth: approaches by specialty and implications for general pediatric care. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis. (2019) 66:55–85. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2019.04.005

9.Owen, N. Feasibility and acceptability of using telehealth for early intervention parent counselling. Adv Ment Health. (2020) 18:39–49. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2019.1679026

10.Carrillo de Albornoz, S, Sia, KL, and Harris, A. The effectiveness of teleconsultations in primary care: systematic review. Fam Pract. (2021) 39:168–82. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmab077

11.Taddei, M, and Bulgheroni, S. Facing the real time challenges of the COVID-19 emergency for child neuropsychology service in Milan. Res Dev Disabil. (2020) 107:103786. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103786

12.Ragamin, A, de Wijs, LEM, Hijnen, DJ, Arends, NJT, Schuttelaar, MLA, Pasmans, SGMA, et al. Care for children with atopic dermatitis in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from the first wave and implications for the future. J Dermatol. (2021) 48:1863–70. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16130

13.Greenhow, C, Walker, JD, and Kim, S. Millennial learners and net-savvy teens? Examining internet use among low-income students. J Comput Teacher Educ. (2009) 26:63–8.

14.Shah, AC, and Badawy, SM. Telemedicine in pediatrics: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Pediatr and Parent. (2021) 4:e22696. doi: 10.2196/22696

15.PRISMA. Transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Available at: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (Accessed December 15, 2022)

16.Kodjebacheva, GD, Culinski, T, Kawser, B, and Amin, S. Satisfaction with pediatric telehealth services according to the opinions of young patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of the literature. Inplasy Protocol. (2022) 1–4. doi: 10.37766/inplasy2022.12.0116

17.Rethlefsen, ML, Kirtley, S, Waffenschmidt, S, Ayala, AP, Moher, D, Page, MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. J Med Libr Assoc. (2021) 109:174–200. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2021.962

18.Allison, BA, Rea, S, Mikesell, L, and Perry, MF. Adolescent and parent perceptions of telehealth visits: a mixed methods study. J Adolesc Health. (2022) 70:403–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.028

19.Bassi, M, Strati, MF, Parodi, S, Lightwood, S, Rebora, C, Rizza, F, et al. Patient satisfaction of telemedicine in pediatric and young adult type 1 diabetes patients during Covid-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:857561. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.857561

20.Caprì, T, Gugliandolo, C, Faraone, C, La Foresta, S, Vita, G, Cuzzocrea, F, et al. The eHealth well-being service for patients with SMA and other neuromuscular disorders during the COVID-19 emergency. Life Span Disabil. (2021):155.

21.Carroll, K, Adams, J, de Valle, K, Forbes, R, Kennedy, RA, Kornberg, AJ, et al. Delivering multidisciplinary neuromuscular care for children via telehealth. Muscle Nerve. (2022) 66:31–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.27557

22.Choi, EK, Bae, E, and Yun, H. Nurse-led eHealth transition care program for adolescents with spina bifida: a feasibility and acceptability study. J Pediatr Nurs. (2022) 67:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2022.07.004

23.Hawke, LD, Sheikhan, NY, MacCon, K, and Henderson, J. Going virtual: youth attitudes toward and experiences of virtual mental health and substance use services during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:340. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06321-7

24.Mekori-Domachevsky, E, Matalon, N, Mayer, Y, Shiffman, N, Lurie, I, Gothelf, D, et al. Internalizing symptoms impede adolescents’ ability to transition from in-person to online mental health services during the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic. J Telemed Telecare. (2021) 30:1357633X2110212. doi: 10.1177/1357633x211021293

25.Mikesell, L, Rea, S, Cuddihy, C, Perry, M, and Allison, B. Exploring the connectivity paradox: how the Sociophysical environment of telehealth shapes adolescent patients’ and parents’ perceptions of the patient-clinician relationship. Health Commun. (2022) 14:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2124056

26.Randall, LA, Raisin, C, Waters, F, Williams, C, Shymko, G, and Davis, D. Implementing telepsychiatry in an early psychosis service during COVID-19: experiences of young people and clinicians and changes in service utilization. Early Interv Psychiatry. (2022) 1–8. doi: 10.1111/eip.13342

27.Spigel, R, Lin, JA, Milliren, CE, Freizinger, M, Vitagliano, JA, Woods, ER, et al. Access to care and worsening eating disorder symptomatology in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eat Disord. (2021) 9:69. doi: 10.1186/s40337-021-00421-9

28.Stewart, C, Konstantellou, A, Kassamali, F, McLaughlin, N, Cutinha, D, Bryant-Waugh, R, et al. Is this the ‘new normal’? A mixed method investigation of young person, parent and clinician experience of online eating disorder treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eat Disord. (2021) 9:78. doi: 10.1186/s40337-021-00429-1

29.Troncone, A, Cascella, C, Chianese, A, Zanfardino, A, Casaburo, F, Piscopo, A, et al. Doctor-patient relationship in synchronous/real-time video-consultations and in-person visits: an investigation of the perceptions of young people with type 1 diabetes and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Behav. (2022) 29:638–47. doi: 10.1007/s12529-021-10047-5

30.Wasilewska, E, Sobierajska-Rek, A, Małgorzewicz, S, Soliński, M, and Jassem, E. Benefits of telemonitoring of pulmonary function-3-month follow-up of home electronic spirometry in patients with duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Clin Med. (2022) 11:856. doi: 10.3390/jcm11030856

31.Ziani, M, Trépanier, E, and Goyette, M. Voices of teens and young adults on the subject of teleconsultation in the COVID-19 context. J Patient Exp. (2022) 9:23743735221092565. doi: 10.1177/23743735221092565

32.Moola, S, Munn, Z, Tufanaru, C, Aromataris, E, Sears, K, Sfetcu, R, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk In: E Aromataris and Z Munn, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. (2020).

33.Elbin, RJ, Stephenson, K, Lipinski, D, Maxey, K, Womble, MN, Reynolds, E, et al. In-person versus telehealth for concussion clinical care in adolescents: a pilot study of therapeutic alliance and patient satisfaction. J Head Trauma Rehabil. (2022) 37:213–9. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000707

34.Graziano, S, Boldrini, F, Righelli, D, Milo, F, Lucidi, V, Quittner, A, et al. Psychological interventions during COVID pandemic: telehealth for individuals with cystic fibrosis and caregivers. Pediatr Pulmonol. (2021) 56:1976–84. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25413

35.Andrews, E, Berghofer, K, Long, J, Prescott, A, and Caboral-Stevens, M. Satisfaction with the use of telehealth during COVID-19: an integrative review. Int J Nurse Stud Adv. (2020) 2:100008. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2020.100008

36.Cunningham, NR, Ely, SL, Barber Garcia, BN, and Bowden, J. Addressing pediatric mental health using telehealth during coronavirus disease-2019 and beyond: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. (2021) 21:1108–17. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.06.002

37.Seron, P, Oliveros, MJ, Gutierrez-Arias, R, Fuentes-Aspe, R, Torres-Castro, RC, Merino-Osorio, C, et al. Effectiveness of telerehabilitation in physical therapy: a rapid overview. Phys Ther. (2021) 101:101. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzab053

38.Bucki, FM, Clay, MB, Tobiczyk, H, and Green, BN. Scoping review of telehealth for musculoskeletal disorders: applications for the COVID-19 pandemic. J Manip Physiol Ther. (2021) 44:558–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2021.12.003

39.Chaudhry, H, Nadeem, S, and Mundi, R. How satisfied are patients and surgeons with telemedicine in orthopaedic care during the COVID-19 pandemic? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2020) 479:47–56. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001494

40.Davis, J, Gordon, R, Hammond, A, Perkins, R, Flanagan, F, Rabinowitz, E, et al. Rapid implementation of telehealth services in a pediatric pulmonary clinic during COVID-19. Pediatrics. (2021) 148:148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-030494

41.Madubuonwu, J, and Mehta, P. How telehealth can be used to improve maternal and child health outcomes: a population approach. Clin Obstet Gynecol. (2021) 64:398–406. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000610

42.Karimi, M, Lee, EC, Couture, SJ, Gonzales, A, Grigorescu, V, Smith, SR, et al. (2022). National survey trends in telehealth use in 2021: Disparities in utilization and audio vs. video services. Office of Health Policy: Assistant secretary of planning and evaluation. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/4e1853c0b4885112b2994680a58af9ed/telehealth-hps-ib.pdf (Accessed February 10, 2023)

43.Kronforst, K, Barrera, L, Casale, M, Smith, TL, Schinasi, D, and Macy, ML. Pediatric telehealth access and utilization in Chicago during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. (2023). doi: 10.1089/tmj.2022.0481

44.Clare, CA. Telehealth and the digital divide as a social determinant of health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Netw Model Anal Health Inform Bioinform. (2021) 10:26. doi: 10.1007/s13721-021-00300-y

45.Ortega, G, Rodriguez, JA, Maurer, LR, Witt, EE, Perez, N, Reich, A, et al. Telemedicine, COVID-19, and disparities: policy implications. Health Policy Technol. (2020) 9:368–71. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.001

46.Nadkarni, A, Hasler, V, AhnAllen, CG, Amonoo, HL, Green, DW, Levy-Carrick, NC, et al. Telehealth during COVID-19-does everyone have equal access? Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:1093–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060867

47.Rodriguez, JA, Clark, CR, and Bates, DW. Digital health equity as a necessity in the 21st century cures act era. JAMA. (2020) 323:2381–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7858

48.Blundell, AR, Kroshinsky, D, Hawryluk, EB, and Das, S. Disparities in telemedicine access for Spanish-speaking patients during the COVID-19 crisis. Pediatr Dermatol. (2021) 38:947–9. doi: 10.1111/pde.14489

49.Federal Communications Commission. Connected care pilot program. Federal Communications Commission. Available at: (2020). https://www.fcc.gov/wireline-competition/telecommunications-access-policy-division/connected-care-pilot-program (Accessed December 15, 2022)

50.Curfman, AL, Hackell, JM, Herendeen, NE, Alexander, JJ, Marcin, JP, Moskowitz, WB, et al. Telehealth: improving access to and quality of pediatric health care. Pediatrics. (2021) 148:e2021053129. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053129

51.Blum, RW, Astone, NM, Decker, MR, and Mouli, VC. A conceptual framework for early adolescence: a platform for research. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2014) 26:321–31. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2013-0327

52.Capusan, KY, and Fenster, T. Patient satisfaction with telehealth during the COVID19 pandemic in a pediatric pulmonary clinic. J Pediatr Health Care. (2021) 35:587–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.07.014

53.Dempsey, CM, Serino-Cipoletta, JM, Marinaccio, BD, O'Malley, KA, Goldberg, NE, Dolan, CM, et al. Determining factors that influence parents’ perceptions of telehealth provided in a pediatric gastroenterological practice: a quality improvement project. J Pediatr Nursing. (2022) 62:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.11.023

54.Jaclyn, D, Andrew, N, Ryan, P, Julianna, B, Christopher, S, Nauman, C, et al. Patient and family perceptions of telehealth as part of the cystic fibrosis care model during COVID-19. J Cyst Fibros. (2021) 20:e23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.03.009

55.Knaus, ME, Ahmad, H, Metzger, GA, Beyene, TJ, Thomas, JL, Weaver, LJ, et al. Outcomes of a telemedicine bowel management program during COVID19. J Pediatr Surg. (2022) 57:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.09.012

56.Shanok, NA, Lozott, EB, Sotelo, M, and Bearss, K. Community-based parent-training for disruptive behaviors in children with ASD using synchronous telehealth services: a pilot study. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2021) 88:101861. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101861

57.Cook, A, Bragg, J, and Reay, RE. Pivot to telehealth: narrative reflections on circle of security parenting groups during COVID19. Austr N Z J Fam Ther. (2021) 42:106–14. doi: 10.1002/anzf.1443

58.Staffieri, SE, Mathew, AA, Sheth, SJ, Ruddle, JB, and Elder, JE. Parent satisfaction and acceptability of telehealth consultations in pediatric ophthalmology: initial experience during the COVID19 pandemic. J AAPOS. (2021) 25:104–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.12.003

59.Panda, PK, Dawman, L, Panda, P, and Sharawat, IK. Feasibility and effectiveness of teleconsultation in children with epilepsy amidst the ongoing COVID19 pandemic in a resourcelimited country. Seizure. (2020) 81:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.07.013

60.Johnson, C, Taff, K, Lee, BR, and Montalbano, A. The rapid increase in telemedicine visits during COVID-19. Patient Exp J. (2020) 7:72–9. doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1475

61.Wood, SM, Pickel, J, Phillips, AW, Baber, K, Chuo, J, Maleki, P, et al. Acceptability, feasibility, and quality of telehealth for adolescent health care delivery during the COVID19 pandemic: cross sectional study of patient and family experiences. JMIR Pediatr Parent. (2021) 4:e32708. doi: 10.2196/32708

Keywords: telehealth, telemedicine, adolescents, teenagers, children, attitudes, perceptions, satisfaction

Citation: Kodjebacheva GD, Culinski T, Kawser B and Amin S (2023) Satisfaction with pediatric telehealth according to the opinions of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. Front. Public Health. 11:1145486. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1145486

Edited by:

Janet Michel, University Hospital Bern, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Charles R. Doarn, University of Cincinnati, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Kodjebacheva, Culinski, Kawser and Amin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gergana Damianova Kodjebacheva Z2VyZ2FuYUB1bWljaC5lZHU=

Gergana Damianova Kodjebacheva

Gergana Damianova Kodjebacheva Taylor Culinski

Taylor Culinski Bushra Kawser1

Bushra Kawser1 Saman Amin

Saman Amin