- Office of Public Health Studies, Thompson School of Social Work & Public Health, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, United States

Loneliness in older persons is a major risk factor for adverse health outcomes. Before the COVID-19 pandemic led to unprecedented isolation and hampered programs aimed at preventing or reducing loneliness, many interventions were developed and evaluated. However, previous reviews provide limited or conflicting summaries of intervention effectiveness. This systematic review aimed to assess previous review quality and bias, as well as to summarize key findings into an overarching narrative on intervention efficacy. The authors searched nine electronic databases and indices to identify systematic reviews of interventions to reduce loneliness in older people prior to the COVID-19 pandemic; 6,925 records were found initially. Of these, 19 reviews met inclusion criteria; these encompassed 101 unique primary intervention studies that varied in research design, sample size, intervention setting, and measures of loneliness across 21 nations. While 42% of reviews had minimal risk of bias, only 8% of primary studies appraised similarly. Among the 101 unique articles reviewed, 63% of tested interventions were deemed by article author(s) as effective or partially effective. Generally, interventions that included animals, psychological therapies, and skill-building activities were more successful than interventions focused on social facilitation or health promotion. However, interventions that targeted multiple objectives aimed at reducing loneliness (e.g., improving social skills, enhancing social support, increasing social opportunities, and changing maladaptive social cognition) were more effective than single-objective interventions. Future programs should incorporate multiple approaches, and these interventions should be rigorously tested.

1 Introduction

Reported prevalence of loneliness among older adults varies widely, with estimates from 7 to 63%, while many reports estimate a point prevalence around 20% (1–14). Incidence may be increasing throughout the world (1, 15–17). Some explanations for the increases in rates of loneliness are associated with increased longevity, greater years lived with disability, and degradation of social support over time (4, 18–21). An increase in single living and delayed marriage, along with a decrease in fertility rates and ability to spend time with loved ones due to delayed retirement, may also play significant roles (14, 19, 21–26). In the early 2020s, the COVID pandemic increased social isolation for all, which likely increased prevalence of loneliness among older adults.

Although the terms loneliness and social isolation have been used interchangeably, they are different constructs. Loneliness is an unwelcomed feeling of being removed from people and communities (3, 9, 16, 20, 27, 28). Social isolation refers to an objective lack of integration with others who would otherwise supply structural or functional social support. While analytic studies show an overlap of the terms as resulting in similar negative health consequences in older people (2, 8, 10–13, 17, 19, 29–34), the concepts are distinct (2, 8, 16, 17, 30, 31, 35–38). Moreover, the presence of one does not necessitate the presence of the other (10, 17, 39). This review spotlights loneliness only, as it is unequivocally unwanted, whereas some older adults may seek out social isolation.

Loneliness is commonly identified as a risk factor for adverse health outcomes, such as mental illness, cardiovascular disease, and early death (2, 5–7, 15, 16, 18, 23, 27, 29, 40, 41). Chronic loneliness is also associated with increased inpatient admissions, inpatient stay lengths, and emergency care visits (8, 22, 28). Many researchers compare the effects of chronic loneliness to those of cigarette smoking, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and persistent hypertension (7, 15, 35, 42–44).

Researchers across disciplines have tested interventions to increase interpersonal engagement and combat loneliness (5, 8, 20, 28, 30, 36, 40, 41, 45, 46). Masi et al. categorized intervention objectives or aims into four area—improving social skills, enhancing social support, increasing social opportunities, and changing maladaptive social cognition (20, 35, 41). A thematic analysis by Gardiner et al. (30) described six main types of interventions: social facilitation, psychological therapies, health and social care provision, animal assistance activities, befriending programs, and leisure or skill-development activities.

The overall effectiveness of interventions is difficult to summarize. Numerous narrative and meta-analytic reviews have been published, but many focus on one type of intervention, including a review of reviews by Chipps et al. focused on information-community technology (ICT) interventions (47). Overall, the reviews provide inconsistent or conflicting summaries regarding effectiveness of individual approaches or types of approaches to combat loneliness (12, 13, 15). Also, while review authors have assessed the quality of the included studies, there has been limited reflection of quality of these reviews.

Thus, the purpose of this systematic review is to synthesize previously completed reviews. This overview is unique in that it focuses only on loneliness as an outcome. Moreover, it fills important research gaps by assessing the quality of each review article and summarizing key findings and data of previous reviews into a comprehensive narrative on intervention effectiveness.

2 Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis for Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 guidelines (48) were followed, but the protocol was unregistered.

2.1 Search methods

Under the guidance of a medical information specialist, search terms in the five PICOS categories were selected for Population (older adults, as defined by authors), Interventions to reduce loneliness, Comparator (any), Outcomes (loneliness), and Study design (systematic review). The authors tailored queries with associated controlled vocabulary per database (Appendix A). Nine electronic databases and indices were searched for systematic reviews written between January 1970 and July 2020. The authors investigated dissertations and gray literature for qualified refereed reviews published elsewhere. Upon recommendation of subject experts, the authors hand-searched The Gerontologist and The Journals of Gerontology. Citation tracking of included reviews discovered supplementary reviews to aid in narrative development.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Reviews must have summarized finding from the testing of interventions to alleviate loneliness as a primary or secondary goal among older adults (49). Reviews must have been peer-reviewed and systematic and presented quantitative or qualitative evidence detailing the effectiveness of interventions to prevent or reduce loneliness. The authors included reviews that examined interventions targeting corollary constructs, like social isolation and social participation, if one or more embedded studies aimed to reduce loneliness.

2.3 Article selection

After citations were found using the search strategy above, duplicates were removed. The Zotero 5 software suite was used to collect, manage, and cite sources (50). The authors identified prospective reviews from searches by scanning titles, then abstracts, and finally, full-text articles. Consensus was used to resolve eligibility concerns. The authors extracted review information in accordance with the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group (EPOC) using a modified form for systematic reviews of reviews (51, 52).

2.4 Categorization of interventions

Interventions were categorized by the authors into one of the four intervention objectives or aims identified by Masi et al.—improving social skills, enhancing social support, increasing social opportunities, and changing maladaptive social cognition (46). They also were categorized by type of intervention as outlined by Gardiner et al.—social facilitation, psychological therapies, health and social care provision, animal assistance activities, befriending programs, and leisure or skill development activities (23).

2.5 Risk of bias analysis

Systematic reviews were assessed for risk of bias via A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2) (53). Appraisal of critical and non-critical items (as defined by the tool) established summary ratings of High, Moderate, Low, and Critically Low. Due to the heterogeneity of approaches, interventions, populations, and outcomes, the authors did not conduct a meta-analysis of underlying studies (51, 54).

3 Results

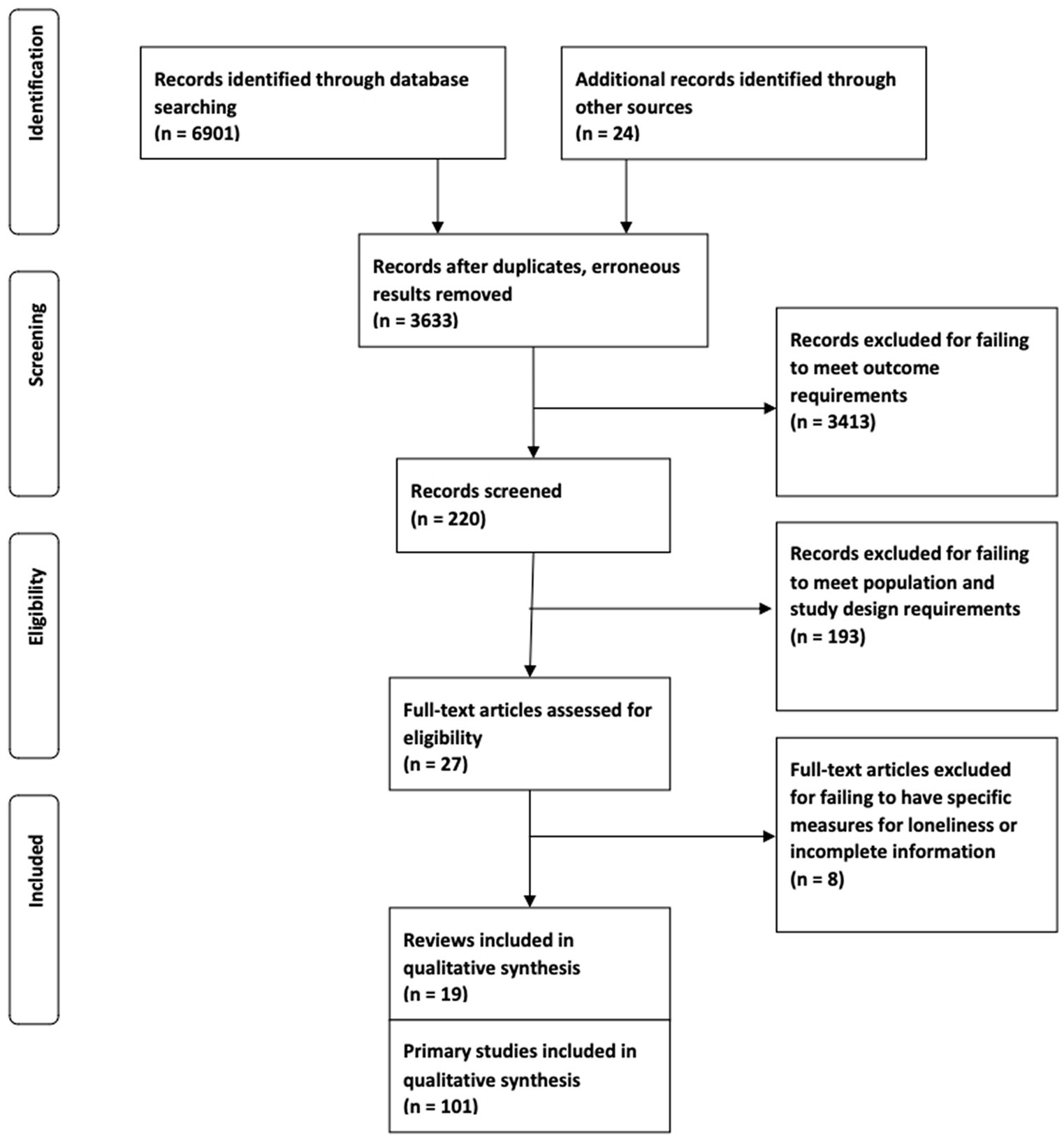

A search conducted in August 2020 yielded 6,901 records, and another 24 records were identified through citation chasing. Of the 6,925 total records, titles of 6,705 clearly indicated that they were not relevant to this review and were eliminated. The abstracts of the 220 remaining records were screened, and 193 more were excluded. The remaining 27 reviews were read in full. Eight of these held incomplete information or failed to include explicit measures for loneliness. Thus, 19 systematic reviews were included. These encompassed 212 primary research studies, of which 101 (47%) were unique (Figure 1).

3.1 Characteristics

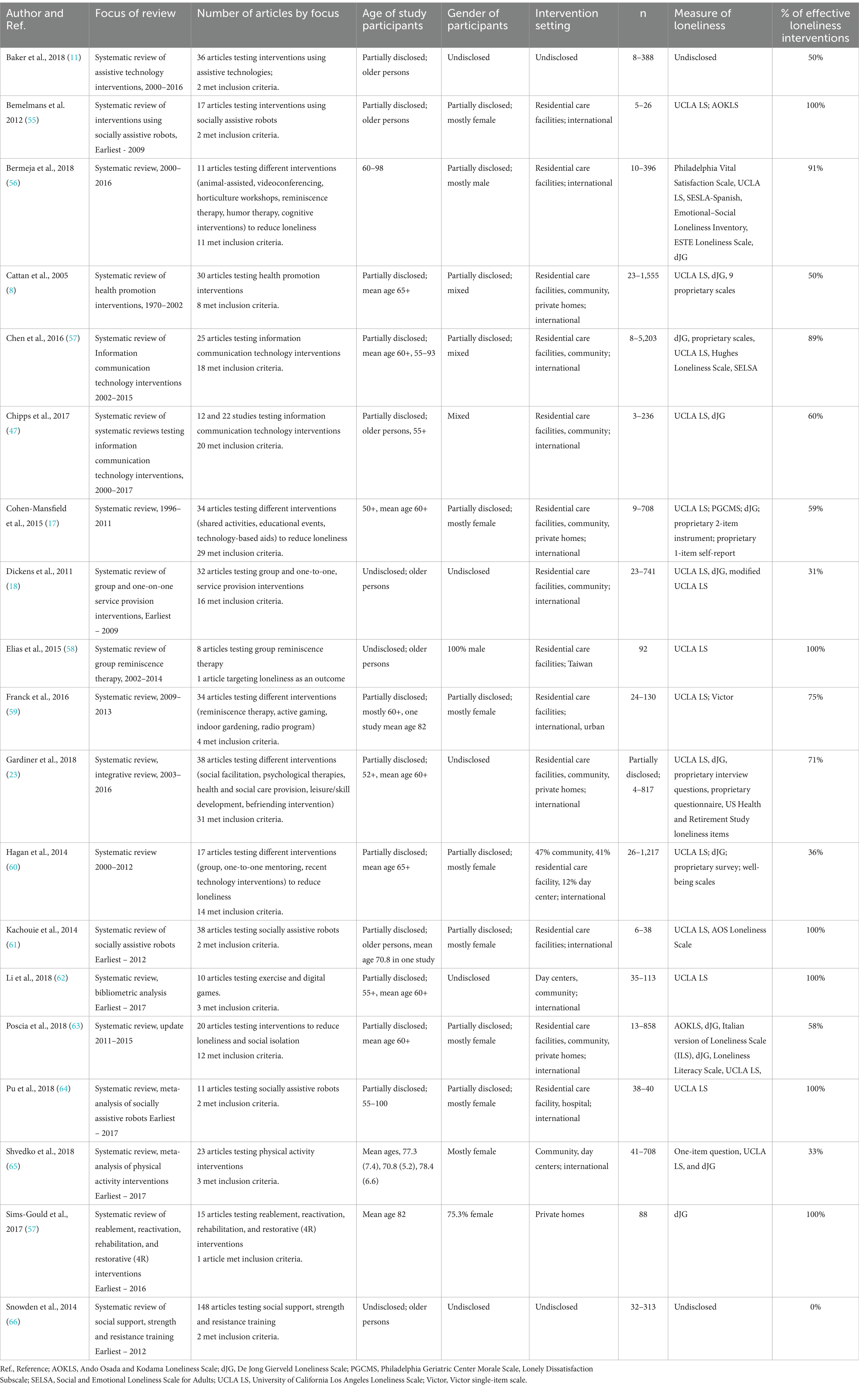

The characteristics of the 19 reviews are shown in Table 1. The median year of publication is 2016, with only one review published prior to 2010. Of the 19, two systematic reviews provided meta-analyses (67, 68), and one was the aforementioned review of systematic reviews of ICT of interventions (47). Eight reviews (42%) were general in nature (30, 40, 41, 69–73), while seven (37%) focused on technological interventions (11, 47, 68, 74–77), and four (21%) focused on physical or mental health promotion activities (8, 67, 78, 79).

Only three of the reviews limited their study to articles expressly testing intervention impact on loneliness (17, 56, 60), while the other 16 reviews included a subset of articles testing an intervention’s impact on loneliness. For example, Elias et al. reviewed eight articles testing the impact of group reminiscence therapy on alleviating depression, anxiety, and loneliness, with only one article targeting loneliness as an outcome (58).

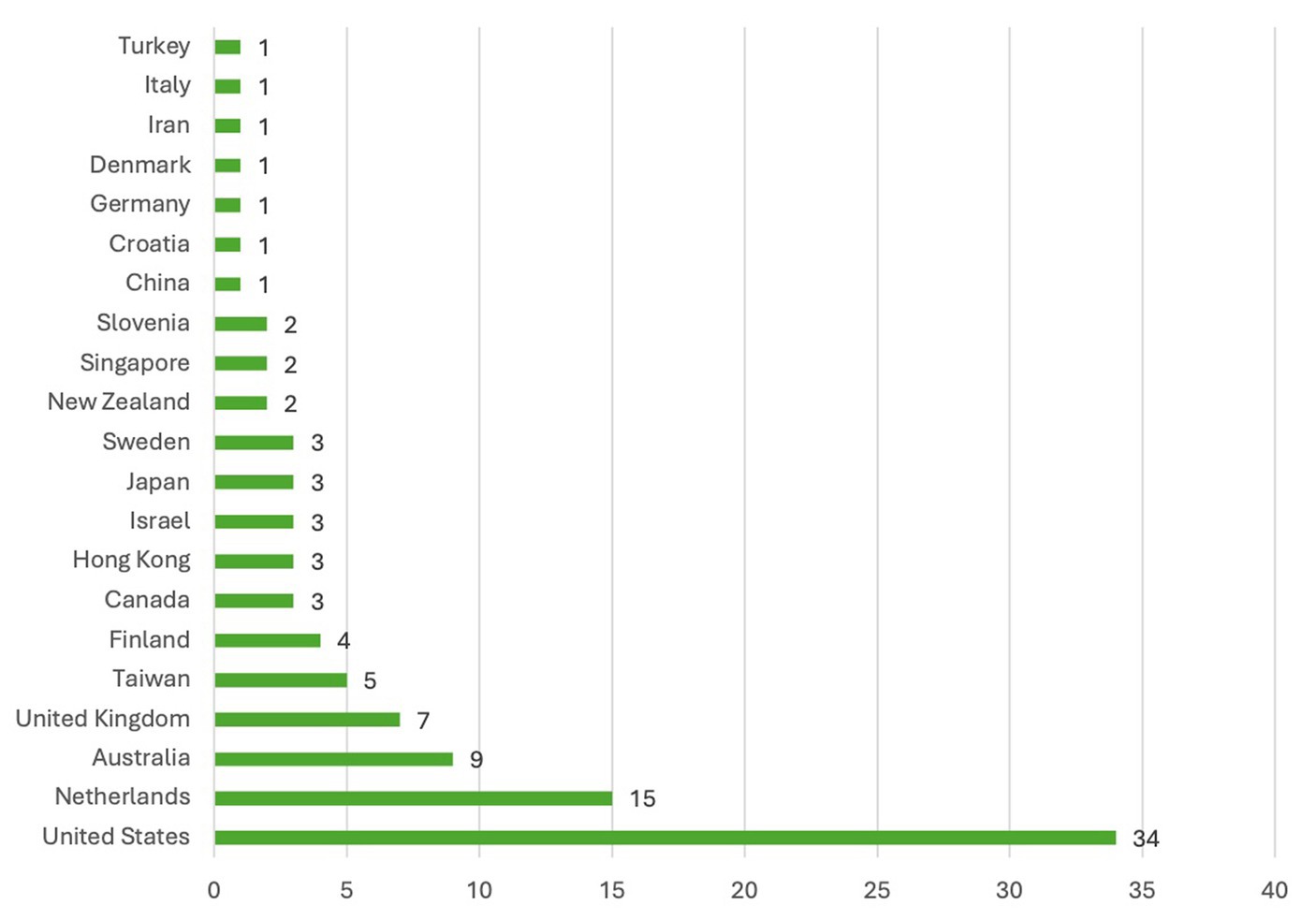

Characteristics of the 101 primary studies (including only one of the eight in the Elias et al. review) are shown in Table 2. About half (52) of the 101 primary studies were published after 2010. While 69 (68%) of the articles were included in only one of the 19 review articles, 42 were included in two or more of the review articles. Overall, studies sampled populations from 21 nations (Figure 2); including 35 in Europe and the United Kingdom, 34 in the United States, 14 in Asia, 11 in Australia/New Zealand, five in Middle Eastern countries, and three in Canada.

Studies tested interventions using assorted designs, including controlled trial, clustered controlled trial, quasi-experimental design, pre-experimental (before-and-after) design, cross-sectional, and mixed-method types. Samples ranged from 3 to 5,203 subjects. Interventions occurred in residential care facilities, community day centers, and private homes. While some subjects were as young as 52 years old, the mean age of subjects in each study was above 60 years. Only some studies disclosed full gender characteristics. Six different measures were used across the 101 studies to measure loneliness.

Intervention types per Gardiner et al. (first column), activities (fifth column), and objectives per Masi et al. (last four columns) also are shown in Table 2. In terms of intervention objectives, only 10 of the 101 studies had a single objective, while 50 had two, 28 had 3, and 13 aimed to target all 4 areas. Thus, 91 of the 101 studies had an objective to enhance social support, 91 aimed to increase social opportunities, 46 strove to improve social skills, and 18 were designed to change maladaptive social cognition.

In terms of intervention type, 39 of the 101 studies tested interventions offering leisure or skill-building activities, 17 evaluated psychological therapies, 17 tested social facilitation interventions, 14 evaluated health promotion interventions, eight (8%) gaged animal-assisted interventions, and six (6%) assessed multi-category programs. While 88% of the psychological therapies and 67% of the multi-category interventions had three or more intervention objectives (e.g., to enhance social support, improve social skills and change maladaptive behavior), health promotion programs and leisure and skill-building activities tended to have fewer intervention objectives.

3.2 Effectiveness

Table 1 recaps included systematic reviews. Review authors gaged interventions to be mostly of mixed effectiveness when aiming to reduce loneliness in older persons. Most reviews found some support for both group and individual-targeted interventions; however, at least one general and one health intervention review found group interventions to be more effective (8, 41) and at least one general review found the converse (70).

Six (75%) of eight general reviews obtained mixed results, while one (13%) concluded interventions to be mostly effective (30), and one (13%) avoided a conclusion due to insufficient evidence (73). Regarding reviews appraising technological interventions, five (71%) of seven reviews summarized this type to be mostly effective, while one (14%) review found mixed efficacy for some assistive technology interventions such as social networking services (11), and one (14%) review could not provide a conclusive evaluation due to the limitations of underlying studies (47). Reviews focused on physical and mental health promotions stated ambiguous results of their effectiveness: one (25%) of four reviews provided evidence that group reminiscence therapy approaches are effective (78), while two (50%) reviews found no overarching proof of programmatic efficacy (67, 79). One (25%) review by Cattan et al. relayed assorted results of interventions combatting loneliness (8).

Regarding intervention objective, researchers found 14 (78%) of 18 interventions focused on changing maladaptive social cognition, 31 (67%) of 46 on improving social skills, 59 (65%) of 91 on enhancing social support, and 57 (63%) of 91 on increasing social opportunities to be effective or partially effective. Five (50%) of 10 of uni-objective intervention, 32 (64%) of 50 bi-objective interventions, 16 (57%) of 28 of tri-objective interventions, and 11 (85%) of 13 complete, quad-objective studies were effective or partially effective.

3.3 Quality

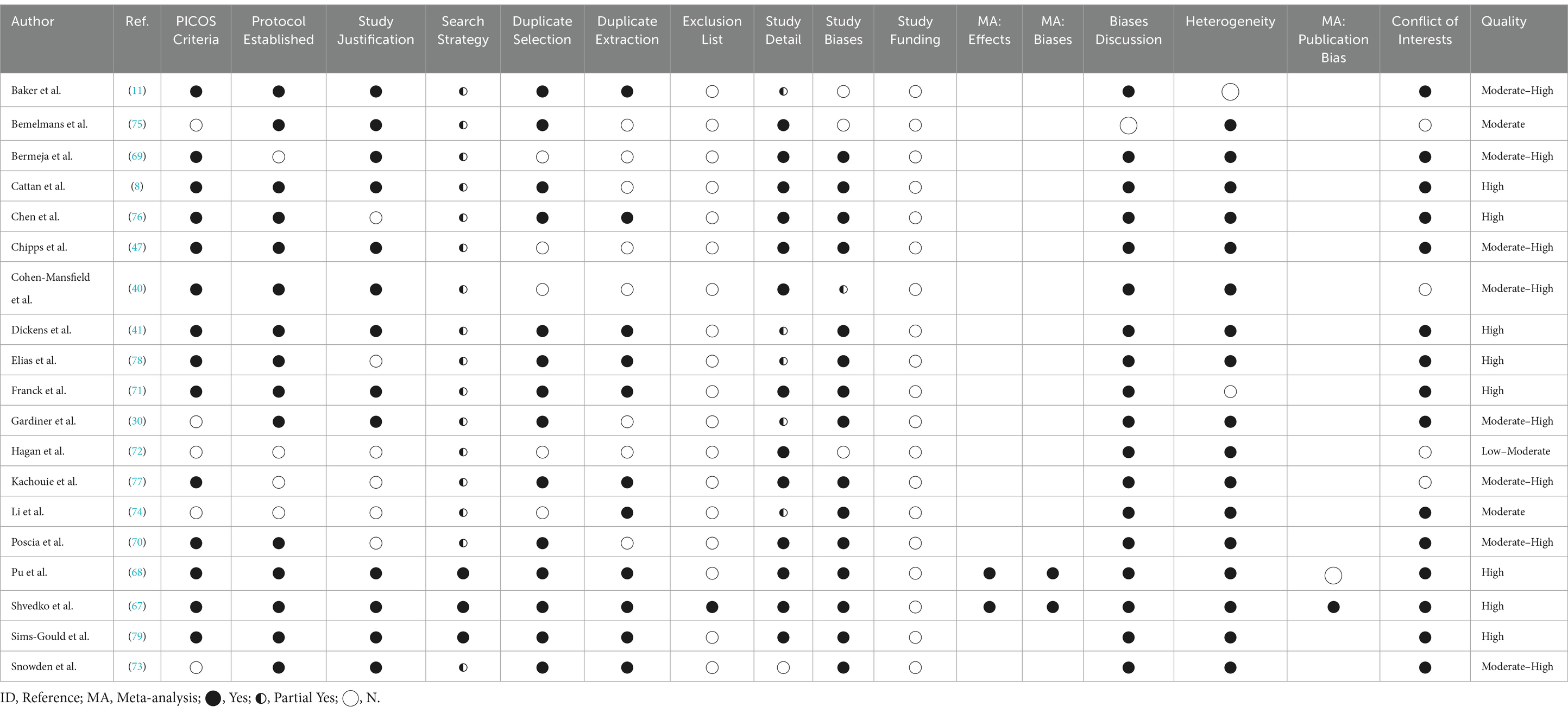

Table 3 details estimates of study quality of each systematic review. The authors appraised 8 (42%) of 19 reviews to be of high quality (8, 41, 67, 68, 71, 76, 78, 79), with another eight (42%) being of moderate-high quality. These reviews displayed a minimal risk of bias. Two reviews (11%) were assessed as of moderate quality, and one (5%) was deemed low-moderate quality. Every health promotion review was high-quality. In contrast, only two (29%) of seven reviews appraising technology-based interventions and two (25%) of eight general intervention reviews were of high quality.

In accordance with the AMSTAR 2 guidelines (53), the authors accounted for the following three criteria when developing a summary of review quality. No reviews fully disclosed information regarding primary study funding per Item 10. Most reviews failed to provide a comprehensive list of excluded studies per Item 7. Only 24 studies (24%) employed randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs. Only two studies provided a meta-analysis (67, 68); hence, these were the only ones subject to Items 11, 12, and 15.

Table 2 also lists quality assessment, including grading criteria, for each of the 101 studies within the 19 reviews. The authors found only eight (8%) of the 101 studies to be of high quality (58, 82, 84, 91, 98, 105, 108, 161). Eight (8%) were between medium and high quality, 42 (42%) were of medium quality, 20 (20%) between low and medium quality, and 23 (23%) were of low quality. High-quality investigations were rare across intervention objectives, e.g., only two (4%) of 46 intervention that aimed to improve social skills, 7 (8%) of 91 interventions that aimed to enhance social support, 8 (9%) of the 91 that aimed to increase social opportunities, and 3 (17%) of 18 that aimed to change maladaptive social cognition to be of high quality.

Additionally, Table 2 lists the efficacy of each intervention, as noted by the reviews and studies themselves. Of the 101 underlying studies, primary investigators concluded 64 (63%) to be effective or partially effective. However, this varied by study designs, e.g., only 12 of the 24 programs tested through RCT were found to be effective. Irrespective of study methodology, all eight (100%) animal-assisted interventions, five (83%) of six multi-category programs, 13 (76%) of 17 psychological therapies, 26 (67%) of 39 leisure or skill-building activities, 6 (43%) of 14 health promotions, and 6 (35%) of 17 social facilitations were effective or partially effective.

4 Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review of reviews of interventions to combat loneliness in older people. Nineteen systematic reviews amassed the findings of 101 unique studies of interventions. While 42% of the reviews were of the highest quality and contained minimal risk of bias, only 8% of primary studies were of the highest quality according to reviewers.

Regarding usefulness, the authors deducted that 63% of all interventions were effective or possibly effective at combatting loneliness. Multi-category interventions were above-par, along with programs featuring reminiscence therapies (88, 92, 93) and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (96). All animal-assisted approaches were efficacious in combatting loneliness, including living (64, 65, 100, 102, 103), robotic (63, 101, 102), and virtual pet companionship (62). In addition, key findings support interventions with multiple objectives, as 85% of interventions with four objectives (improving social skills, enhancing social support, increasing social opportunities, and changing maladaptive social cognition) alleviated loneliness. The most successful single-objective interventions were those targeting maladaptive social cognition (55–57, 59, 60, 66, 81, 82, 84, 88, 92, 93, 96, 98), presumably to help lonely older adults develop more stable interpersonal relationships and perpetuate social opportunities. This finding is consistent with the hallmark meta-analysis by Masi et al. (35) on subjects of any age.

4.1 Limitations

Various considerations tempered the conclusions of this research. First, the authors limited the search to the pre-COVID years. Second, the included systematic reviews had differing foci and scopes, and this heterogeneity hindered comparisons across reviews. Many systematic reviews included were of moderate-high and high quality, but some displayed an elevated risk of bias (72, 75). Likewise, many of the studies testing a single intervention exhibited moderate-to-high risk of bias as a product of poor study design.

This systematic review of reviews compiled studies that utilized a variety of loneliness-related outcome measures. While some (i.e., UCLA Loneliness Scale, De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale) were well-tested with older people and psychometrically sound (61, 167–169), others were single-item measures or instruments of disputed reliability and validity (8). Also, this review provided a dichotomous summary statistic of effectiveness in its analyses, which reduced complex findings into manageable figures for easy comparison. Binning of interventions by intervention objective is a highly subjective task. Scholars should exercise caution when reducing constructs as complex as loneliness and social isolation into crude metrics, especially together, at the risk of misinterpreting primary study authors’ conclusions (29, 170).

4.2 Recommendations

Three findings stand out. First, allied health professions should develop broad interventions. A multi-objective approach aptly targets the multi-dimensional issue of loneliness (69, 76, 171, 172). Some participants of such interventions may find certain components useful, while other participants would find distinct parts worthwhile. Increasing the number of strategies can target the widest range of participants. This explains the above-average effectiveness ratings of integrated approaches to combating loneliness. The Dutch Geriatric Intervention Program (82) and Finnish psychosocial group rehabilitation intervention (59) are illustrative of this approach. Conclusions here are consistent with the best practices of robust health promotion initiatives targeting a variety of outcomes (173, 174).

Second, interventions should become more purpose-driven (67, 71) to stem the losses of identity many lonely older adults feel (78, 175). Shvedko et al. remarked that the theory of active engagement explains loneliness reduction through a productive lifestyle that generates a sense of purpose (67, 176). Effective programs provide more than aimless social opportunities (30, 132), and more than friendly health and social care visitations, as Cattan et al. found (8). Prime examples of purpose-driven approaches are horticulture-learning experiences (60, 149, 155) and fitness-improving “exergames” (144, 145, 161). The authors also observed specific, purposeful technology trainings to be effective in reducing loneliness, including programs utilizing mobile phones (135), electronic pen pals (163), and videoconferencing software (147, 151, 152).

Third, specific types of interventions proved to be more promising than others. Psychotherapeutic interventions utilized the highly effective strategy of modifying maladaptive social cognition—specifically engaging the theoretical mechanism of action noted by Cacioppo and others (5, 15). Animal-assisted interventions were helpful in providing purpose, delivering skills training, and increasing social opportunities for older people (62–65, 100–103), a finding that Banks et al. consistently espoused (65, 102, 103). Finally, technological interventions exhibited potential even as multiple reviews found inconclusive evidence (11, 47, 149). Chen et al. wrote “the older adults employment of [ICT] reduces their social isolation through the following mechanisms: connecting to the outside world, gaining social support, engaging in activities of interest, and boosting self-confidence” (76). Simple interventions, with little-to-no expert training or sharing were not effective (71), but approaches that demonstrated technology as a tool to encourage mobility, communication, or education exhibited high value (68, 74, 177).

Further studies of interventions to combat loneliness are needed. The authors request more individual or cluster RCTs to ensure a high-quality body of primary research not limited by risks of bias. Research scientists should heed the differences between social isolation and loneliness, lest phenomenological conclusions become confounded. Lastly, the authors concur with others who note plausible cultural moderators of intervention efficacy (8, 30, 40, 74, 75, 77) and encourage further examination of culture in perceptions of loneliness and ways to combat it.

5 Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated quarantine orders further exacerbated the loneliness faced by many older adults (178). As health policies combatting loneliness quickly develop—like the national effort in the United Kingdom (179–181) or the health service company-led strategies in the United States (182–185)—researchers must begin to decipher years of equivocal findings and offer actionable recommendations. This report’s value lies in being the first systematic overview of the evidence base on loneliness interventions targeting older people in an attempt to help answer the question “What does an effective intervention look like?” Our findings suggest that interventions utilizing multiple strategies while incorporating purposeful activities are vital in disrupting loneliness and its deleterious effects in older adults.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

UP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Although this study was not conducted under a specific funding mechanism, the senior author is funded to support junior faculty through grant number 2U54MD007601–36 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and grant number U54GM138062 from the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by graduate faculty in the Office of Public Health Studies and the librarians at the John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1427605/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Victor, CR, Scambler, SJ, Bowling, A, and Bond, J. The prevalence of, and risk factors for, loneliness in later life: a survey of older people in Great Britain. Ageing Soc. (2005) 25:357–75. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X04003332

2. AARP FoundationElder, K, and Retrum, J. Isolation framework. (2012). Washington, DC US: AARP Foundation.

3. Dykstra, PA . Older adult loneliness: myths and realities. Eur J Ageing. (2009) 6:91–100. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0110-3

4. Nicolaisen, M, and Thorsen, K. Loneliness among men and women – a five-year follow-up study. Aging Ment Health. (2014) 18:194–206. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.821457

5. Ong, AD, Uchino, BN, and Wethington, E. Loneliness and health in older adults: a Mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology. (2016) 62:443–9. doi: 10.1159/000441651

6. Dias, M, Silva, C, Dias, R, and Oliveira, H. Intervention in the loneliness of the elderly—what strategies, Challenges and Rewards? J Health Sci. (2015) 3:71–80. doi: 10.17265/2328-7136/2015.02.003

7. Luo, Y, and Waite, LJ. Loneliness and mortality among older adults in China. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2014) 69:633–45. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu007

8. Cattan, M, White, M, Bond, J, and Learmouth, A. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing Soc. (2005) 25:41–67. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X04002594

9. Stessman, J, Rottenberg, Y, Shimshilashvili, I, Ein-Mor, E, and Jacobs, JM. Loneliness, health, and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2014) 69:744–50. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt147

10. Grenade, L, and Boldy, D. Social isolation and loneliness among older people: issues and future challenges in community and residential settings. Aust Health Rev. (2008) 32:468–78. doi: 10.1071/AH080468

11. Baker, S, Warburton, J, Waycott, J, Batchelor, F, Hoang, T, Dow, B, et al. Combatting social isolation and increasing social participation of older adults through the use of technology: a systematic review of existing evidence. Australas J Ageing. (2018) 37:184–93. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12572

12. Cattan, M, Newell, C, Bond, J, and White, M. Alleviating social isolation and loneliness among older people. Int J Ment Health Promot. (2003) 5:20–30. doi: 10.1080/14623730.2003.9721909

13. Valtorta, N, and Hanratty, B. Loneliness, isolation and the health of older adults: do we need a new research agenda? J R Soc Med. (2012) 105:518–22. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2012.120128

14. Pinquart, M, and Sorensen, S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: a Meta-analysis. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. (2001) 23:245–66. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2304_2

15. Cacioppo, S, Grippo, AJ, London, S, Goossens, L, and Cacioppo, JT. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2015) 10:238–49. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616

16. Perissinotto, CM, Stijacic Cenzer, I, and Covinsky, KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. (2012) 172:1078–83. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993

17. Wright-St Clair, VA, Neville, S, Forsyth, V, White, L, and Napier, S. Integrative review of older adult loneliness and social isolation in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Australas J Ageing. (2017) 36:114–23. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12379

18. Aylaz, R, Aktürk, Ü, Erci, B, Öztürk, H, and Aslan, H. Relationship between depression and loneliness in elderly and examination of influential factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2012) 55:548–54. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.03.006

19. Wenger, GC, and Burholt, V. Changes in levels of social isolation and loneliness among older people in a rural area: a twenty-year longitudinal study. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. (2004) 23:115–27. doi: 10.1353/cja.2004.0028

20. Andersson, L . Loneliness research and interventions: a review of the literature. Aging Ment Health. (1998) 2:264–74. doi: 10.1080/13607869856506

21. Tomaka, J, Thompson, S, and Palacios, R. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. J Aging Health. (2006) 18:359–84. doi: 10.1177/0898264305280993

22. Gerst-Emerson, K, and Jayawardhana, J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health. (2015) 105:1013–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302427

23. Leah, V . Feelings of loneliness and living alone as predictors of mortality in the elderly: the PAQUID study. Nurs Older People. (2017) 29:13–3. doi: 10.7748/nop.29.1.13.s17

24. Mullins, LC, and Elston, CH. Social determinants of loneliness among older Americans. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. (1996) 122:455.

25. Green, LR, Richardson, DS, Lago, T, and Schatten-Jones, EC. Network correlates of social and emotional loneliness in young and older adults. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. (2001) 27:281–8. doi: 10.1177/0146167201273002

26. Pinquart, M . Loneliness in married, widowed, divorced, and never-married older adults. J Soc Pers Relat. (2003) 20:31–53. doi: 10.1177/02654075030201002

27. Sabir, M, Wethington, E, Breckman, R, Meador, R, Reid, MC, and Pillemer, K. A community-based participatory critique of social isolation intervention research for community-dwelling older adults. J Appl Gerontol. (2009) 28:218–34. doi: 10.1177/0733464808326004

28. Elkan, R, Kendrick, D, Dewey, M, Hewitt, M, Robinson, J, Blair, M, et al. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2001) 323:719–25. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.719

29. Coyle, CE, and Dugan, E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. (2012) 24:1346–63. doi: 10.1177/0898264312460275

30. Gardiner, C, Geldenhuys, G, and Gott, M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Community. (2018) 26:147–57. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12367

31. Steptoe, A, Shankar, A, Demakakos, P, and Wardle, J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2013) 110:5797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110

32. Shankar, A, McMunn, A, Banks, J, and Steptoe, A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. (2011) 30:377–85. doi: 10.1037/a0022826

33. Dugan, E, and Kivett, VR. The importance of emotional and social isolation to loneliness among very old rural adults. The Gerontologist. (1994) 34:340–6. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.3.340

34. Findlay, RA . Interventions to reduce social isolation amongst older people: where is the evidence? Ageing Soc. (2003) 23:647–58. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X03001296

35. Masi, CM, Chen, HY, Hawkley, LC, and Cacioppo, JT. A Meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personal Soc Psychol Rev Off J Soc Personal Soc Psychol Inc. (2011) 15, 219–66. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394

36. Landeiro, F, Barrows, P, Nuttall Musson, E, Gray, AM, and Leal, J. Reducing social isolation and loneliness in older people: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013778. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013778

37. Adams, KB, Sanders, S, and Auth, EA. Loneliness and depression in independent living retirement communities: risk and resilience factors. Aging Ment Health. (2004) 8:475–85. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001725054

38. Cotterell, N, Buffel, T, and Phillipson, C. Preventing social isolation in older people. Maturitas. (2018) 113:80–4. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.04.014

39. Weiss, RS . Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press (1973). 236 p.

40. Cohen-Mansfield, J, and Perach, R. Interventions for alleviating loneliness among older persons: a critical review. Am J Health Promot. (2015) 29:e109–25. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130418-LIT-182

41. Dickens, AP, Richards, SH, Greaves, CJ, and Campbell, JL. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2011) 11:1–22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-647

42. Cacioppo, JT, Hawkley, LC, Crawford, LE, Ernst, JM, Burleson, MH, Kowalewski, RB, et al. Loneliness and health: potential mechanisms. Psychosom Med. (2002) 64:407–17. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005

43. Hawkley, LC, Burleson, MH, Berntson, GG, and Cacioppo, JT. Loneliness in everyday life: cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2003) 85:105–20. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.105

44. Miller, G . Why loneliness is hazardous to your health. Science. (2011) 331:138–40. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6014.138

45. Leigh-Hunt, N, Bagguley, D, Bash, K, Turner, V, Turnbull, S, Valtorta, N, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. (2017) 152:157–71. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

46. Nicholson, NR . A review of social isolation: an important but Underassessed condition in older adults. J Prim Prev. (2012) 33:137–52. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2

47. Chipps, J, Jarvis, MA, and Ramlall, S. The effectiveness of e-interventions on reducing social isolation in older persons: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Telemed Telecare. (2017) 23:817–27. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17733773

48. Shamseer, L, Moher, D, Clarke, M, Ghersi, D, Liberati, A, Petticrew, M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. (2015) 349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647

49. United Nations, DESA, Population Divison. World population prospects: The 2017 revision, key findings and advance tables. New York, USA: United Nations (2017). 47 p.

50. Corporation for Digital Scholarship. Zotero. Vienna, VA US: Corporation for Digital Scholarship (2024).

51. Littell, JH, Corcoran, J, and Pillai, V. Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis. Pocket ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press (2008). 216 p.

52. Higgins, JP, and Green, S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, vol. 4 The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex England: John Wiley & Sons (2011).

53. Shea, BJ, Reeves, BC, Wells, G, Thuku, M, Hamel, C, Moran, J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. (2017) 358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008

54. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD’s guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews, vol. 2n. York, UK: NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2001).

55. Chan, AW, Yu, DS, and Choi, K. Effects of tai chi qigong on psychosocial well-being among hidden elderly, using elderly neighborhood volunteer approach: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging. (2017) 12:85–96. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S124604

56. Saito, T, Kai, I, and Takizawa, A. Effects of a program to prevent social isolation on loneliness, depression, and subjective well-being of older adults: a randomized trial among older migrants in Japan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2012) 55:539–47. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.04.002

57. Alaviani, M, Khosravan, S, Alami, A, and Moshki, M. The effect of a multi-strategy program on developing social behaviors based on Pender’s health promotion model to prevent loneliness of old women referred to Gonabad urban health centers. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. (2015) 3:132–40.

58. Hopman-Rock, M, Westhoff, MH, and Chodzko-Zajko, WJ. Development and evaluation of “aging well and healthily”: a health-education and exercise program for community-living older adults. J Aging Phys Act. (2002) 10:364–81. doi: 10.1123/japa.10.4.364

59. Savikko, N, Routasalo, P, Tilvis, R, and Pitkälä, K. Psychosocial group rehabilitation for lonely older people: favourable processes and mediating factors of the intervention leading to alleviated loneliness. Int J Older People Nursing. (2010) 5:16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2009.00191.x

60. Tse, MMY, Lo, APK, Cheng, TLY, Chan, EKK, Chan, AHY, and Chung, HSW. Humor therapy: relieving chronic pain and enhancing happiness for older adults. J Aging Res. (2010) 2010:1–9. doi: 10.4061/2010/343574

61. De Jong, GJ, and Van Tilburg, T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur J Ageing. (2010) 7:121–30. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6

62. Machesney, D, Wexler, SS, Chen, T, and Coppola, JF. Gerontechnology companion: Virutal pets for dementia patients. In: IEEE Long Island Systems, Applications and Technology (LISAT) Conference 2014. (2014). p. 1–3.

63. Kanamori, M, Suzuki, M, Oshiro, H, Tanaka, M, Inoguchi, T, Takasugi, H, et al. Pilot study on improvement of quality of life among elderly using a pet-type robot. In: Proceedings 2003 IEEE International Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation for the New Millennium (Cat No03EX694). (2003). p. 107–112 vol.1.

64. Krause-Parello, CA . Pet ownership and older women: the relationships among loneliness, pet attachment support, human social support, and depressed mood. Geriatr Nur (Lond). (2012) 33:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2011.12.005

65. Banks, MR, and Banks, WA. The effects of group and individual animal-assisted therapy on loneliness in residents of long-term care facilities. Anthrozoös. (2005) 18:396–408. doi: 10.2752/089279305785593983

66. Kremers, IP, Steverink, N, Albersnagel, FA, and Slaets, JPJ. Improved self-management ability and well-being in older women after a short group intervention. Aging Ment Health. (2006) 10:476–84. doi: 10.1080/13607860600841206

67. Shvedko, A, Whittaker, AC, Thompson, JL, and Greig, CA. Physical activity interventions for treatment of social isolation, loneliness or low social support in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2018) 34:128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.10.003

68. Pu, L, Moyle, W, Jones, C, and Todorovic, M. The effectiveness of social robots for older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. The Gerontologist. (2018) 59:e37–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny046

69. Bermeja, AI, and Ausín, B. Programas para combatir la soledad en las personas mayores en el ámbito institucionalizado: una revisión de la literatura científica. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. (2018) 53:155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.regg.2017.05.006

70. Poscia, A, Stojanovic, J, la Milia, DI, Duplaga, M, Grysztar, M, Moscato, U, et al. Interventions targeting loneliness and social isolation among the older people: an update systematic review. Exp Gerontol. (2018) 102:133–44. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.11.017

71. Franck, L, Molyneux, N, Parkinson, L, and Franck, L. Systematic review of interventions addressing social isolation and depression in aged care clients. Qual Life Res. (2016) 25:1395–407. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1197-y

72. Hagan, R, Manktelow, R, Taylor, BJ, and Mallett, J. Reducing loneliness amongst older people: a systematic search and narrative review. Aging Ment Health. (2014) 18:683–93. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.875122

73. Snowden, MB, Steinman, LE, Carlson, WL, Mochan, KN, Abraido-Lanza, AF, Bryant, LL, et al. Effect of physical activity, social support, and skills training on late-life emotional health: a systematic literature review and implications for public health research. Front Public Health. (2014) 2:213. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00213

74. Li, J, Erdt, M, Chen, L, Cao, Y, Lee, SQ, and Theng, YL. The social effects of Exergames on older adults: systematic review and metric analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2018) 20:e10486. doi: 10.2196/10486

75. Bemelmans, R, Gelderblom, GJ, Jonker, P, and de Witte, L. Socially assistive robots in elderly care: a systematic review into effects and effectiveness. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2012) 13:114–120.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.10.002

76. Chen, YRR, and Schulz, PJ. The effect of information communication technology interventions on reducing social isolation in the elderly: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2016) 18:e18. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4596

77. Kachouie, R, Sedighadeli, S, Khosla, R, and Chu, MT. Socially assistive robots in elderly care: a mixed-method systematic literature review. Int J Hum-Comput Interact. (2014) 30:369–93. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2013.873278

78. Syed Elias, SM, Neville, C, and Scott, T. The effectiveness of group reminiscence therapy for loneliness, anxiety and depression in older adults in long-term care: a systematic review. Geriatr Nurs (New York). (2015) 36:372–80. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.05.004

79. Sims-Gould, J, Tong, CE, Wallis-Mayer, L, and Ashe, MC. Reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation and restorative interventions with older adults in receipt of home care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2017) 18:653–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.070

80. Ollonqvist, K, Palkeinen, H, Aaltonen, T, Pohjolainen, T, Puukka, P, Hinkka, K, et al. Alleviating loneliness among frail older people – findings from a randomised controlled trial. Int J Ment Health Promot. (2008) 10:26–34. doi: 10.1080/14623730.2008.9721760

81. Fukui, S, Koike, M, Ooba, A, and Uchitomi, Y. The effect of a psychosocial group intervention on loneliness and social support for Japanese women with primary breast Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. (2003) 30:823–30. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.823-830

82. Melis, RJF, van Eijken, MIJ, Teerenstra, S, van Achterberg, T, Parker, SG, Borm, GF, et al. Multidimensional geriatric assessment: Back to the future a randomized study of a multidisciplinary program to intervene on geriatric syndromes in vulnerable older people who live at home (Dutch EASYcare study). J Gerontol Ser A. (2008) 63:283–90. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.3.283

83. van der Heide, LA, Willems, CG, Spreeuwenberg, MD, Rietman, J, and de Witte, LP. Implementation of CareTV in care for the elderly: the effects on feelings of loneliness and safety and future challenges. Technol Disabil. (2012) 24:283–91. doi: 10.3233/TAD-120359

84. Arnetz, BB, Theorell, T, and Arnetz, BB. Psychological, sociological and health behaviour aspects of a long term activation programme for institutionalized elderly people. Soc Sci Med. (1983) 17:449–56. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90050-3

85. Stewart, M, Mann, K, Jackson, S, Downe-Wamboldt, B, Bayers, L, Slater, M, et al. Telephone support groups for seniors with disabilities. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. (2001) 20:47–72. doi: 10.1017/S0714980800012137

86. Stewart, M, Craig, D, MacPherson, K, and Alexander, S. Promoting positive affect and diminishing loneliness of widowed seniors through a support intervention. Public Health Nurs. (2001) 18:54–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00054.x

87. Routasalo, PE, Tilvis, RS, Kautiainen, H, and Pitkala, KH. Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on social functioning, loneliness and well-being of lonely, older people: randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. (2009) 65:297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04837.x

88. Gaggioli, A, Morganti, L, Bonfiglio, S, Scaratti, C, Cipresso, P, Serino, S, et al. Intergenerational group reminiscence: a potentially effective intervention to enhance elderly psychosocial wellbeing and to improve Children’s perception of aging. Educ Gerontol. (2014) 40:486–98. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2013.844042

89. Honigh-de Vlaming, R, Haveman-Nies, A, and Heinrich, J. Effect evaluation of a two-year complex intervention to reduce loneliness in non-institutionalised elderly Dutch people. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:984. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-984

90. Savelkoul, M, and De, WLP. Mutual support groups in rheumatic diseases: effects and participants’ perceptions. Arthritis Care Res. (2004) 51:605–8. doi: 10.1002/art.20538

91. Andersson, L . Intervention against loneliness in a group of elderly women: an impact evaluation. Soc Sci Med. (1985) 20:355–64. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90010-3

92. Chiang, KJ, Chu, H, Chang, HJ, Chung, MH, Chen, CH, Chiou, HY, et al. The effects of reminiscence therapy on psychological well-being, depression, and loneliness among the institutionalized aged. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2010) 25:380–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.2350

93. Liu, S, Lin, C, Chen, Y, and Huang, X. The effects of reminiscence group therapy on self-esteem, depression, loneliness and life satisfaction of elderly people living alone. -Taiwan. J Med. (2007) 12:133–42. doi: 10.6558/MTJM.2007.12(3).2

94. Collins, CC, and Benedict, J. Evaluation of a community-based health promotion program for the elderly: lessons from seniors CAN. Am J Health Promot. (2006) 21:45–8. doi: 10.1177/089011710602100108

95. Cox, EO, Green, KE, Hobart, K, Jang, LJ, and Seo, H. Strengthening the late-life care process: effects of two forms of a care-receiver efficacy intervention. The Gerontologist. (2007) 47:388–97. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.3.388

96. Creswell, JD, Irwin, MR, Burklund, LJ, Lieberman, MD, Arevalo, JMG, Ma, J, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults: a small randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. (2012) 26:1095–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.006

97. Evans, RL, and Jaureguy, BM. Phone therapy outreach for blind elderly. The Gerontologist. (1982) 22:32–5. doi: 10.1093/geront/22.1.32

98. Rosen, CE, and Rosen, S. Evaluating an intervention program for the elderly. Community Ment Health J. (1982) 18:21–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00757109

99. Winningham, RG, and Pike, NL. A cognitive intervention to enhance institutionalized older adults’ social support networks and decrease loneliness. Aging Ment Health. (2007) 11:716–21. doi: 10.1080/13607860701366228

100. Vrbanac, Z, Zečević, I, Ljubić, M, Belić, M, Stanin, D, Brkljača Bottegaro, N, et al. Animal assisted therapy and perception of loneliness in geriatric nursing home residents. Coll Antropol. (2013) 37:973–6.

101. Robinson, H, MacDonald, B, Kerse, N, and Broadbent, E. The psychosocial effects of a companion robot: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2013) 14:661–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.02.007

102. Banks, MR, Willoughby, LM, and Banks, WA. Animal-assisted therapy and loneliness in nursing homes: use of robotic versus living dogs. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2008) 9:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.11.007

103. Banks, MR, and Banks, WA. The effects of animal-assisted therapy on loneliness in an elderly population in long-term care facilities. J Gerontol Ser A. (2002) 57:M428–32. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.7.M428

104. Tesch-Römer, C . Psychological effects of hearing aid use in older adults. J Gerontol Ser B. (1997) 52B:P127–38. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52B.3.P127

105. Sørensen, KD, Hendriksen, C, and Strømgård, E. Cooperation concerning admission to and discharge of elderly people from the hospital. 3. Functional capacity, self-assessed health and quality of life. Ugeskr Laeger. (1989) 151:1609–12.

106. Tse, MMY, Tang, SK, Wan, VTC, and Vong, SKS. The effectiveness of physical exercise training in pain, mobility, and psychological well-being of older persons living in nursing homes. Pain Manag Nurs. (2014) 15:778–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2013.08.003

107. de Craen, AJM, Gussekloo, J, Blauw, GJ, Willems, CG, and Westendorp, RGJ. Randomised controlled trial of unsolicited occupational therapy in community-dwelling elderly people: the LOTIS trial. PLoS Clin Trials. (2006) 1:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010002

108. van Rossum, E, Frederiks, CM, Philipsen, H, Portengen, K, Wiskerke, J, and Knipschild, P. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people. BMJ. (1993) 307:27–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6895.27

109. Dhillon, JS, Ramos, C, Wünsche, BC, and Lutteroth, C. Designing a web-based telehealth system for elderly people: an interview study in New Zealand. In: 2011 24th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS). (2011). p. 1–6.

110. Clarke, M, Clarke, SJ, and Jagger, C. Social intervention and the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Epidemiol. (1992) 136:1517–23. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116473

111. Mutrie, N, Doolin, O, Fitzsimons, CF, Grant, PM, Granat, M, Grealy, M, et al. Increasing older adults’ walking through primary care: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Fam Pract. (2012) 29:633–42. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms038

112. Bickmore, TW, Caruso, L, Clough-Gorr, K, and Heeren, T. ‘It’s just like you talk to a friend’ relational agents for older adults. Interact Comput. (2005) 17:711–35. doi: 10.1016/j.intcom.2005.09.002

113. Jette, AM, Harris, BA, Sleeper, L, Lachman, ME, Heislein, D, Giorgetti, M, et al. A home-based exercise program for nondisabled older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. (1996) 44:644–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01825.x

114. McAuley, E, Blissmer, B, Marquez, DX, Jerome, GJ, Kramer, AF, and Katula, J. Social relations, physical activity, and well-being in older adults. Prev Med. (2000) 31:608–17. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0740

115. Bartlett, H, Warburton, J, Lui, CW, Peach, L, and Carroll, M. Preventing social isolation in later life: findings and insights from a pilot Queensland intervention study. Ageing Soc. (2013) 33:1167–89. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X12000463

116. Davidson, JW, McNamara, B, Rosenwax, L, Lange, A, Jenkins, S, and Lewin, G. Evaluating the potential of group singing to enhance the well-being of older people. Australas J Ageing. (2014) 33:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00645.x

117. Iecovich, E, and Biderman, A. Attendance in adult day care centers and its relation to loneliness among frail older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. (2012) 24:439–48. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001840

118. Martina, C, and Stevens, NL. Breaking the cycle of loneliness? Psychological effects of a friendship enrichment program for older women. Aging Ment Health. (2006) 10:467–75. doi: 10.1080/13607860600637893

119. Stevens, NL, Martina, CMS, and Westerhof, GJ. Meeting the need to belong: predicting effects of a friendship enrichment program for older women. The Gerontologist. (2006) 46:495–502. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.495

120. Cattan, M, Kime, N, and Bagnall, AM. The use of telephone befriending in low level support for socially isolated older people – an evaluation. Health Soc Care Community. (2011) 19:198–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00967.x

121. Dickens, AP, Richards, SH, Hawton, A, Taylor, RS, Greaves, CJ, Green, C, et al. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a community mentoring service for socially isolated older people: a controlled trial. BMC Public Health. (2011) 11:218. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-218

122. Hemingway, A, and Jack, E. Reducing social isolation and promoting well being in older people. Qual Ageing Older Adults. (2013) 14:25–35. doi: 10.1108/14717791311311085

123. Kime, N, Bagnall, A, and Cattan, M. The delivery and management of telephone befriending services – whose needs are being met? Qual Ageing Older Adults. (2012) 13:231–40. doi: 10.1108/14717791211264278

124. Bergman-Evans, B . Beyond the basics: effects of the Eden alternative model on quality of life issues. J Gerontol Nurs. (2004) 30:27–34. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20040601-07

125. Butler, SS . Evaluating the senior companion program: a mixed-method approach. J Gerontol Soc Work. (2006) 47:45–70. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n01_05

126. Heller, K, Thompson, MG, Trueba, PE, Hogg, JR, and Vlachos-Weber, I. Peer support telephone dyads for elderly women: was this the wrong intervention? Am J Community Psychol. (1991) 19:53–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00942253

127. Ring, L, Barry, B, Totzke, K, and Bickmore, T. Addressing loneliness and isolation in older adults proactive affective agents provide better support. Geneva, Switzerland: IEEE (2013).

128. Rook, KS, and Sorkin, DH. Fostering social ties through a volunteer role: implications for older-adults’ psychological health. Int J Aging Hum Dev. (2003) 57:313–37. doi: 10.2190/NBBN-EU3H-4Q1N-UXHR

129. Anstadt, SP, and Byster, D. Intergenerational groups: rediscovering our legacy. Adv Soc Work. (2009) 10:39–50. doi: 10.18060/177

130. Ballantyne, A, Trenwith, L, Zubrinich, S, and Corlis, M. ‘I feel less lonely’: what older people say about participating in a social networking website. Qual Ageing Older Adults. (2010) 11:25–35. doi: 10.5042/qiaoa.2010.0526

131. Low, LF, Baker, JR, Harrison, F, Jeon, YH, Haertsch, M, Camp, C, et al. The lifestyle engagement activity program (LEAP): implementing social and recreational activity into case-managed home care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2015) 16:1069–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.07.002

132. Pettigrew, S, and Roberts, M. Addressing loneliness in later life. Aging Ment Health. (2008) 12:302–9. doi: 10.1080/13607860802121084

133. Sum, S, Mathews, RM, Hughes, I, and Campbell, A. Internet Use and Loneliness in Older Adults. CyberPsychol Behav. (2008) 11:208–11. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0010

134. Travers, C, and Bartlett, HP. Silver memories: implementation and evaluation of a unique radio program for older people. Aging Ment Health. (2011) 15:169–77. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.508774

135. Karimi, A, and Neustaedter, C. From high connectivity to social isolation: communication practices of older adults in the digital age In: Proceedings of the ACM 2012 conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work Companion (CSCW '12). New York, NY US: Association for Computing Machinery. (2012). 127–30.

136. Blažun, H, Saranto, K, and Rissanen, S. Impact of computer training courses on reduction of loneliness of older people in Finland and Slovenia. Comput Hum Behav. (2012) 28:1202–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.02.004

137. Khvorostianov, N, Elias, N, and Nimrod, G. ‘Without it I am nothing’: the internet in the lives of older immigrants. New Media Soc. (2012) 14:583–99. doi: 10.1177/1461444811421599

138. Shapira, N, Barak, A, and Gal, I. Promoting older adults’ well-being through internet training and use. Aging Ment Health. (2007) 11:477–84. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086546

139. Aarts, S, Peek, STM, and Wouters, EJM. The relation between social network site usage and loneliness and mental health in community-dwelling older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2015) 30:942–9. doi: 10.1002/gps.4241

140. Fokkema, T, and Knipscheer, K. Escape loneliness by going digital: a quantitative and qualitative evaluation of a Dutch experiment in using ECT to overcome loneliness among older adults. Aging Ment Health. (2007) 11:496–504. doi: 10.1080/13607860701366129

141. Slegers, K, van Boxtel, MPJ, and Jolles, J. Effects of computer training and internet usage on the well-being and quality of life of older adults: a randomized, Controlled Study. J Gerontol Ser B. (2008) 63:P176–84. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.3.P176

142. Toepoel, V . Ageing, leisure, and social connectedness: how could leisure help reduce social isolation of older people? Soc Indic Res. (2013) 113:355–72. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0097-6

143. Jones, RB, Ashurst, EJ, Atkey, J, and Duffy, B. Older people going online: its value and before-after evaluation of volunteer support. J Med Internet Res. (2015) 17:e122. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3943

144. Jung, Y, Li, KJ, Janissa, NS, Gladys, WLC, and Lee, KM. Games for a better life: effects of playing Wii games on the well-being of seniors in a long-term care facility. In: Proceedings of the Sixth Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment. New York, NY, USA: ACM; (2009). p. 5:1–5:6.

145. Xu, X, Li, J, Pham, TP, Salmon, CT, and Theng, YL. Improving psychosocial well-being of older adults through exergaming: the moderation effects of intergenerational communication and age cohorts. Games Health J. (2016) 5:389–97. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2016.0060

146. Vošner, HB, Bobek, S, Kokol, P, and Krečič, MJ. Attitudes of active older internet users towards online social networking. Comput Hum Behav. (2016) 55:230–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.014

147. Savolainen, L, Hanson, E, Magnusson, L, and Gustavsson, T. An internet-based videoconferencing system for supporting frail elderly people and their carers. J Telemed Telecare. (2008) 14:79–82. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2007.070601

148. Şar, AH, Göktürk, GY, Tura, G, and Kazaz, N. Is the internet use an effective method to cope with elderly loneliness and decrease loneliness symptom? Procedia Soc Behav Sci. (2012) 55:1053–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.597

149. Chen, YM, and Ji, JY. Effects of horticultural therapy on psychosocial health in older nursing home residents: a preliminary study. J Nurs Res JNR. (2015) 23:167–71. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000063

150. Tse, MMY . Therapeutic effects of an indoor gardening programme for older people living in nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. (2010) 19:949–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02803.x

151. Tsai, HH, Tsai, YF, Wang, HH, Chang, YC, and Chu, HH. Videoconference program enhances social support, loneliness, and depressive status of elderly nursing home residents. Aging Ment Health. (2010) 14:947–54. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.501057

152. Tsai, HH, and Tsai, YF. Changes in depressive symptoms, social support, and loneliness over 1 year after a minimum 3-month videoconference program for older nursing home residents. J Med Internet Res. (2011) 13:e93. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1678

153. Bell, CS, Fain, E, Daub, J, Warren, SH, Howell, SH, Southard, KS, et al. Effects of Nintendo Wii on quality of life, social relationships, and confidence to prevent falls. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. (2011) 29:213–21. doi: 10.3109/02703181.2011.559307

154. Bell, C, Fausset, C, Farmer, S, Nguyen, J, Harley, L, and Fain, WB. Examining social media use among older adults. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media. New York, NY, USA: ACM; (2013). p. 158–63.

155. Brown, VM, Allen, AC, Dwozan, M, Mercer, I, and Warren, K. Indoor gardening and older adults: effects on socialization, activities of daily living, and loneliness. J Gerontol Nurs. (2004) 30:34–42. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20041001-10

156. Clark, DJ . Older adults living through and with their computers. Comput Inform Nurs CIN. (2002) 20:117–24.

157. Cohen, GD, Perlstein, S, Chapline, J, Kelly, J, Firth, KM, and Simmens, S. The impact of professionally conducted cultural programs on the physical health, mental health, and social functioning of older adults. The Gerontologist. (2006) 46:726–34. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.726

158. Cotten, SR, Anderson, WA, and McCullough, BM. Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults: cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2013) 15:e39. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2306

159. Heo, J, Chun, S, Lee, S, Lee, KH, and Kim, J. Internet Use and Well-Being in Older Adults. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2015) 18:268–72. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0549

160. James, BD, Boyle, PA, Yu, L, and Bennett, DA. Internet use and decision making in community-based older adults. Front Psychol. (2013) 4:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00605

161. Kahlbaugh, PE, Sperandio, AJ, Carlson, AL, and Hauselt, J. Effects of playing Wii on well-being in the elderly: physical activity, loneliness, and mood. Act Adapt Aging. (2011) 35:331–44. doi: 10.1080/01924788.2011.625218

162. Meyer, D, Marx, T, and Ball-Seiter, V. Social isolation and telecommunication in the nursing home: a pilot study. Gerontologie. (2011) 10:51–8. doi: 10.4017/gt.2011.10.01.004.00

163. Moses, BJ . Technology as a means of reducing loneliness in the elderly. (2003). This is a dissertation from Walden University, Minneapolis, MN US. ProQuest is distributing the document.

164. White, H, McConnell, E, Clipp, E, Branch, LG, Sloane, R, Pieper, C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the psychosocial impact of providing internet training and access to older adults. Aging Ment Health. (2002) 6:213–21. doi: 10.1080/13607860220142422

165. White, H, McConnell, E, Clipp, E, Bynum, L, Teague, C, Navas, L, et al. Surfing the net in later life: a review of the literature and pilot study of computer use and quality of life. J Appl Gerontol. (1999) 18:358–78. doi: 10.1177/073346489901800306

166. Woodward, AT, Freddolino, PP, Blaschke-Thompson, CM, Wishart, DJ, Bakk, L, Kobayashi, R, et al. Technology and aging project: training outcomes and efficacy from a randomized field trial. Ageing Int. (2011) 36:46–65. doi: 10.1007/s12126-010-9074-z

167. De Jong, GJ, and Van Tilburg, T. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: confirmatory tests on survey data. Res Aging. (2006) 28:582–98. doi: 10.1177/0164027506289723

168. Russell, DW . UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. (1996) 66:20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

169. Neto, F . Psychometric analysis of the short-form UCLA loneliness scale (ULS-6) in older adults. Eur J Ageing. (2014) 11:313–9. doi: 10.1007/s10433-014-0312-1

170. Taylor, HO, Taylor, RJ, Nguyen, AW, and Chatters, L. Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. J Aging Health. (2018) 30:229–46. doi: 10.1177/0898264316673511

171. Weiss, RS . Reflections on the present state of loneliness research. J Soc Behav Pers. (1987) 2:1.

172. DiTommaso, E, and Spinner, B. Social and emotional loneliness: a re-examination of weiss’ typology of loneliness. Personal Individ Differ. (1997) 22:417–27. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00204-8

173. World Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion. Health Promot. (1986) 1:405–v. doi: 10.1093/heapro/1.4.405

174. WHO European Working Group on Health Promotion Evaluation. Health promotion evaluation: Recommendations to policy-makers. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Euorpe (1998).

175. Saunders, JC, and Heliker, D. Lessons learned from 5 women as they transition into assisted living. Geriatr Nur (Lond). (2008) 29:369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.10.018

176. Rowe, JW, and Kahn, RL. Successful aging. The Gerontologist. (1997) 37:433–40. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433

177. Czaja, SJ . The role of Technology in Supporting Social Engagement among Older Adults. Public Policy Aging Rep. (2017) 27:145–8. doi: 10.1093/ppar/prx034

178. Su, Y, Rao, W, Li, M, Caron, G, D’Arcy, C, and Meng, X. Prevalence of loneliness and social isolation among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. (2023) 35:229–41. doi: 10.1017/S1041610222000199

179. Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. A connected society: A strategy for tackling loneliness HM Government. London, UK (2018). 84 p.

180. Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness. A call to action: combatting loneliness one conversation at a time (2017). 22 p.

181. Yeginsu, C. Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness. A call to action: Combatting loneliness one conversation at a time. Batley, West Yorkshire, UK: Jo Cox Foundation (2017) p. 1–22.

182. Humana: population health. Population Health (2018). Humana, Louisville, KY US. Available from: http://populationhealth.humana.com/

184. Cigna. New Cigna study reveals loneliness at epidemic levels in America. Cigna Newsroom; (2018). Available from: https://www.cigna.com/newsroom/news-releases/2018/new-cigna-study-reveals-loneliness-at-epidemic-levels-in-america

185. Cigna. Are you feeling lonely? (2018). Available from: https://www.cigna.com/about-us/newsroom/studies-and-reports/loneliness-questionnaire

Keywords: aging, older adults, loneliness, social isolation, systematic review

Citation: Patil U and Braun KL (2024) Interventions for loneliness in older adults: a systematic review of reviews. Front. Public Health. 12:1427605. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1427605

Edited by:

Lenard Kaye, University of Maine, United StatesReviewed by:

Chakra Budhathoki, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesAntonio Guaita, Fondazione Golgi Cenci, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Patil and Braun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Uday Patil, dWRheUBoYXdhaWkuZWR1

Uday Patil

Uday Patil Kathryn L. Braun

Kathryn L. Braun