- 1Department of Pharmacy, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 2College of Pharmacy, University of Sargodha, Sargodha, Pakistan

- 3Department of Pharmacy, The First Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China

- 4Department of Pharmacy Administration and Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Health Science Center, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China

- 5Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology, RAK College of Pharmacy, RAK Medical and Health Sciences University, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates

- 6Institute of Pharmacy, Gulab Devi Educational Complex, Lahore, Pakistan

- 7Department of Clinical Pharmacy & Pharmacotherapeutics, Dubai Pharmacy College, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- 8Department of Pharmacy, Iqra University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Background: Primary dysmenorrhea (PD) is a global public health problem affecting the quality of life of menstruating women. This study aimed to assess the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of female students experiencing PD.

Methodology: This cross-sectional study included 484 female students (aged 16–31 years) from different educational institutes in Sargodha, Pakistan from October 2021 to November 2022. Demographic and menstrual characteristics were collected through interviews using a purpose-developed data collection form, whereas HRQoL was evaluated using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire. Data were analyzed using either Mann–Whitney tests or Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance with SPSS version 23.

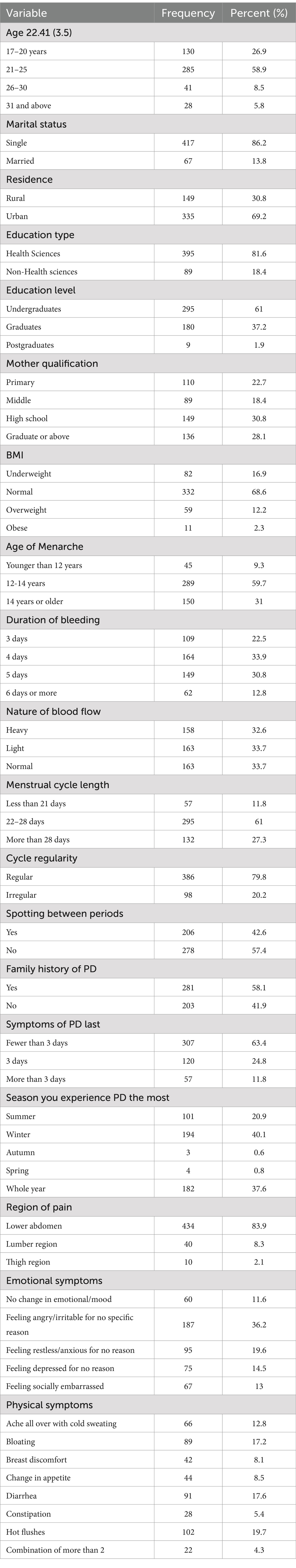

Results: The mean age (SD) of the participants was 22.41 (3.5) years. The majority of participants were aged 21–25 years (58.9%), unmarried (86.2%), had a normal BMI (68.6%), had a family history of PD (58.1%), experienced a regular menstrual cycle (79.8%), and exhibited moderate PD (48.9%). Statistically significant differences in participants’ EQ-5D index scores were observed based on the bleeding duration (p = 0.015), the length of the menstrual cycle (p = 0.004), cycle regularity (p = 0.022), family history (p = 0.027) how long the PD symptoms last (p < 0.001), and the season in which the PD pain is experienced the most (p < 0.001). Moreover, the EQ-VAS score also showed statistically significant differences based on the length of the menstrual cycle (p = 0.007), how long the PD symptoms last (p < 0.001), and the season in which the PD pain is experienced the most (p < 0.001). 51.7% of participants preferred heat application among the various lifestyle modifications to manage PD.

Conclusion: This study indicated that Primary dysmenorrhea (PD) negatively impacts health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Therefore, it is essential to explore effective interventions while raising awareness and improving access to medical care in Pakistan to enhance the HRQoL and well-being of women.

1 Introduction

Millions of women of reproductive age face various challenges related to their menstrual cycles, including pain, discomfort, anxiety, feelings of shame, and a sense of isolation (1). The term dysmenorrhea is defined as a condition of menstruation-associated pelvic pain (2). It is classified into two types: primary and secondary dysmenorrhea (3). Primary dysmenorrhea (PD) is defined as spasmodic and painful cramps in the lower abdomen that begin shortly before or at the onset of menses in the absence of any pelvic pathology and radiate to the inguinal area and buttocks (4, 5). Secondary dysmenorrhea is caused by menstrual pain in the presence of underlying organic disease. It could be of either gynecological origin such as endometriosis, myometrial pathologies such as adenomyosis and fibroids, postoperative adhesion syndrome, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ovarian cyst, or non-gynecological causes where the pain often results from gastrointestinal diseases or urinary tract diseases (6). PD is more common in adolescent girls and usually appears 6 to 12 months after menarche (3, 7). The severe pelvic pain and cramps in PD are accompanied by headache, vomiting, anorexia, nervousness, breast tenderness, and mood swings before or during periods (8, 9). The precise mechanism of PD remains unknown, but recent studies related it with the increased production and release of prostaglandin and a decrease in the progesterone in the luteal phase resulting in increased contractility of myometrium, uterine muscles ischemia, and decreased pain threshold (10–12). Previous studies reported that high-intensity pain and associated complications in patients with PD negatively affect quality of life resulting in higher rates of absenteeism from educational and professional settings leading to poor performance and productivity compared to their male counterparts (13–16). These challenges related to menstruation are evident as “gender-based obstacles” that result in early low retirement savings (17, 18).

Previous studies demonstrated that PD is a widespread gynecologic problem in young and adult women with a global prevalence of 60–93% (19, 20). However, the prevalence varies due to sociocultural, ethnic, or biological factors in various populations (21). Women afflicted with dysmenorrhea often refrain from seeking medical assistance, and when left unaddressed, it is prone to impede their work performance (10). The higher prevalence percentage in developed countries like Japan and Australia is believed to be linked to poor menstrual literacy (22, 23). In contrast, lower-middle-income countries like Ghana, Nigeria (24), and Pakistan considers menstruation a cultural taboo and a shameful burden (25). Similar neglectful and cultural stigma exists in high-income Asian countries like India and China (26). The countries that include menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) in their health and education agenda seem to focus primarily on period poverty but often neglect serious issues such as debilitating menstrual pain, a decline in mental health, disrupted physical activity, and inability to perform effectively in the workplace (27). So, to conclude despite being a primary health issue of every other menstruating female dysmenorrhea is unaddressed in most countries around the globe.

Some studies have focused on lifestyle modifications (28), MHH (29), pain intensity, and poor academic performance (30). A previous study demonstrated differences in pain severity by 23.5% from severe pain requiring pharmacological intervention to mild and moderate pain categories 23. Similarly, a study investigating lifestyle-focused approaches reported that nutrition, physical activity, Body Mass Index (BMI), herbs, essential oils, and medical plants help manage PD (31). Although Pakistan is the world’s fifth most populated country, no such health-related quality of life (HRQoL) study among menstruating university students has been conducted, even though dysmenorrhea affects almost 78% of these women (32). Furthermore, this age group population is critical to investigate because most of them experience this condition and symptoms at the onset or during their reproductive age. Recognizing the impact of primary dysmenorrhea (PD) on health, quality of life, and daily activities; is crucial (33). Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the HRQoL of PD menstruating university students, as well as the lifestyle modification approaches used to manage PD.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted between October 2021 and November 2022 to assess the HRQoL of female students experiencing PD in Sargodha, Pakistan. Participants were recruited from three educational institutions: The University of Sargodha (UoS main campus), Niazi Medical and Dental College, Sargodha, and Doctors Institute of Health Sciences, Sargodha.

2.2 Study population

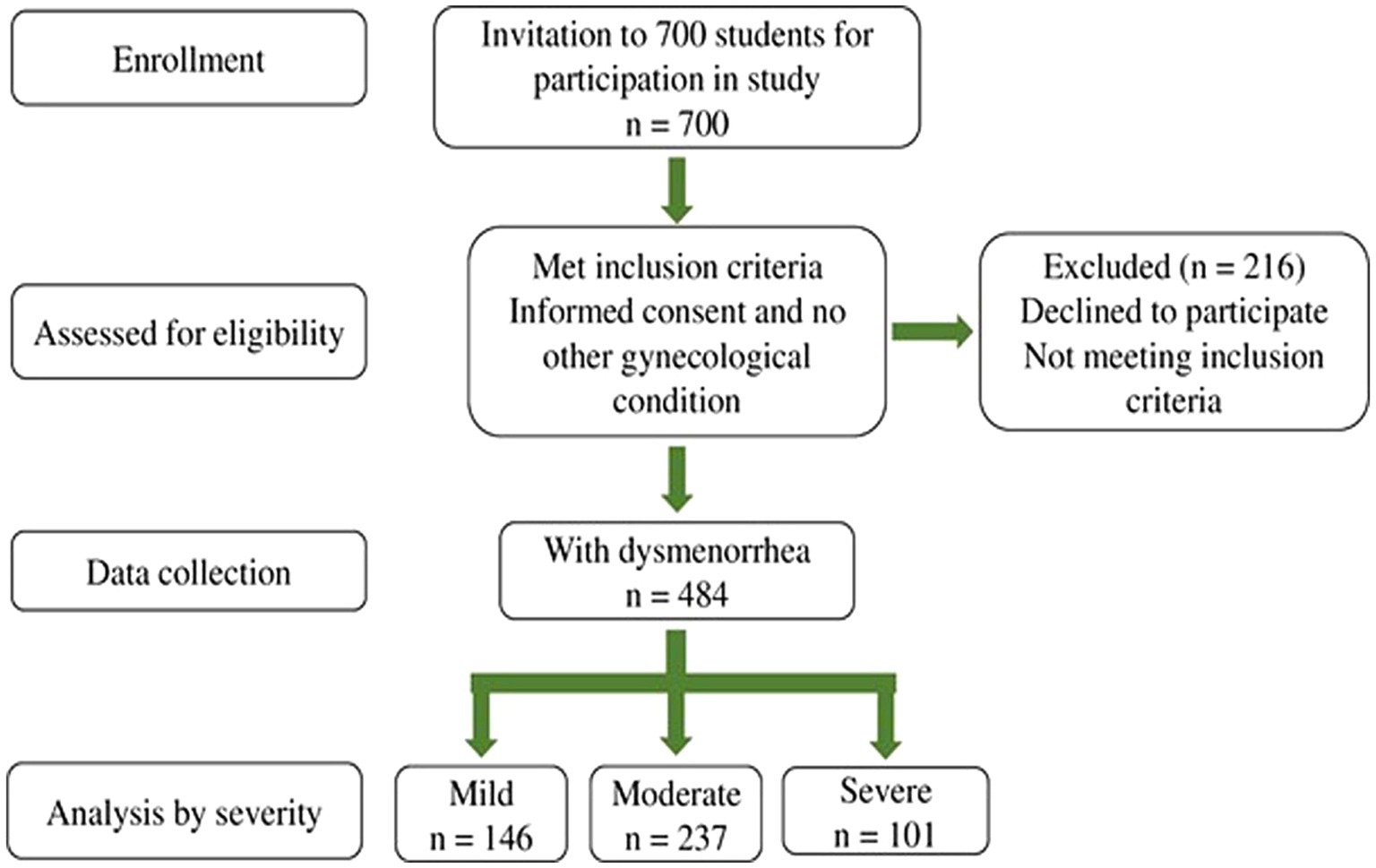

A total of 700 students were contacted to participate in the study. Among them, 484 students met the inclusion criteria: (i) young adult Pakistani females between the ages of 17 and 31 and experiencing PD; (ii) enrolled in either graduation or post-graduation programs; and (iii) with regular menstrual cycles and no gynecological comorbidities. The exclusion criteria included: (i) students who were in academic exchange programs; (ii) students with irregular menstruation or a history of psychological or gynecological illnesses, such as ovarian or cervical cancer, endometriosis, polycystic ovaries, uterine fibroids, or those on hormonal replacement therapy; and (iii) students who did not agree to participate. The subjects who consented to be part of the study but had any diagnosed gynecological pathology or suggestive conditions related to endometriosis, including early menarche, familial history of endometriosis, painful symptoms resisting empirical medical treatment, heavy menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal and genitourinary symptoms, as well as associated symptoms including nausea, fatigue, and effects on daily activities were excluded from the study. All participants signed a written informed consent form before data collection commenced. A flow chart illustrating the criteria for this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of screening, selection, and methodology used for the participants.

2.3 Participants enrollment and study tools

We used a convenient sampling technique to enroll participants. Of the 700 participants who consented to the study, 484 students met the inclusion criteria. The sampling techniques used were a combination of convenient sampling and simple random sampling. A numerical pain-related scale (NPRS) for pain and visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) and EQ-5D-5L, were administered to all participants to accurately assess their levels of pain and HRQoL, respectively, (34, 35).

The first part of the questionnaire included demographic information such as age, BMI, place of residence, family history of dysmenorrhea, menstrual cycle regularity, personal feelings about blood flow, and the duration of symptoms of PD. Participants were asked about the season in which they are more vulnerable to pain, the age of menarche, their education level and their subject specialty, and the remedies they use to cope with their menstrual pain. Participants were asked to rate their level of pain using a numerical pain-related scale (NPRS) that ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain). The NPRS is a widely used 11-digit numeric scale for quantifying pain from 0–10. 0 shows no pain, 1–3 for mild pain, 4–6 for moderate pain, and 7–10 shows the worst pain (33).

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire evaluated the participants’ HRQoL. This questionnaire provides a single index value for health status and a descriptive profile. Using “Euro QoL 5D 5 L,” the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with primary dysmenorrhea was determined. Participants in the study documented their answers on the visual analogue scale and descriptive section. In the descriptive component, the study participants are asked to choose one level from a set of following five domains—mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression (henceforth M, SC, UA, PD, and AD) which best reflects their current state of health. Level 1 is “no problem,” Level 2 is “slight problem,” Level 3 is “moderate problem,” Level 4 is “severe problem,” and Level 5 is “extreme problem/unable to do.” We obtained EQ-5D-5L health states directly from the respondent’s self-reported questionnaire. The EQ-5D-5L measures health states. As a result, EQ-5D-5L has 3,125 potential health states. An EQ-5D-5L score of “11,111″ indicates perfect health, while a score of “55,555” signifies the worst health. The EQ-5D index utility score is derived from England’s EQ-5D-5L value set, as a value set specific to Pakistan was not available (36, 37). The UK value set can be accessed through a link on the EuroQol website1 (38). According to the scoring guidelines, an EQ-5D index value of 1 represents the best possible health status, whereas a value of −0.594 indicates the worst health status.

The study participants also selected one point from the 20 cm long visual analogue scale (VAS) to report their perceived health. This scale’s two endpoints are “best imaginable health” and “Worst imaginable health.” The scale has 10 readings from “0” to “100” and the study participants are asked to rate their current health states on this scale (39). If any participant did not understand a question, assistance was provided, and participants were encouraged to answer all questions. The questionnaire took approximately 10–15 min to complete.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The initial data sheets were checked, coded, and prepared into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. The data was then exported to IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM SPSSR Statistics for Windows, version 23.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) for analysis. The HRQoL utility scores (index values) were calculated using the original 1995 UK population data due to a lack of utility score data from the Pakistani population. Our data was not normally distributed after its normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Hence, we performed non-parametric tests. Mann Whitney U and Kruskal Wallis tests wherever applicable were used to evaluate the difference between participants’ EQ-5D-5L and EQ-VAS scores based on their sociodemographic and PD-related characteristics. Findings with a p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Sociodemographic, menstrual, and PD-related characteristics of the study participants

The sociodemographic, menstrual, and PD-related characteristics of study participants are given in Table 1. The mean age (SD) of the study participants was 22.41 (3.5) years. The majority of them were 21–25 years old (58.9%), unmarried (86.2%), urban residents (69.2%), undergraduate students (61%), had a normal BMI (68.6%), family history of PD (58.1%), and regular menstrual cycle (79.8%). According to the WHO standards, Cut-off values for BMI are underweight <18.5, normal 18.50–24.99, overweight ≥25, and obese ≥30.

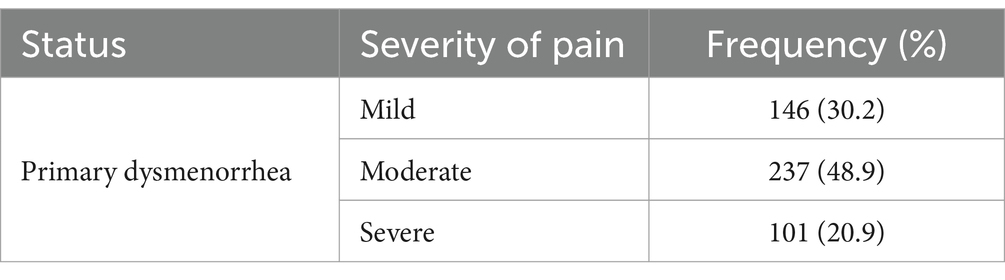

Moreover, 63.4% of them experienced menstrual pain for less than 3 days, and 32.6% of participants had heavy periods. Interestingly, 59.7% had their first period at 12–14 years. The Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) was used for pain assessment. On this scale, 30.2% (n = 146) had mild PD, whereas 48.9% (n = 237) had moderate PD, and 20.9% (n = 101) had severe PD, as mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea mild, moderate, and severe among study populations according to numerical pain-related scale (NPRS).

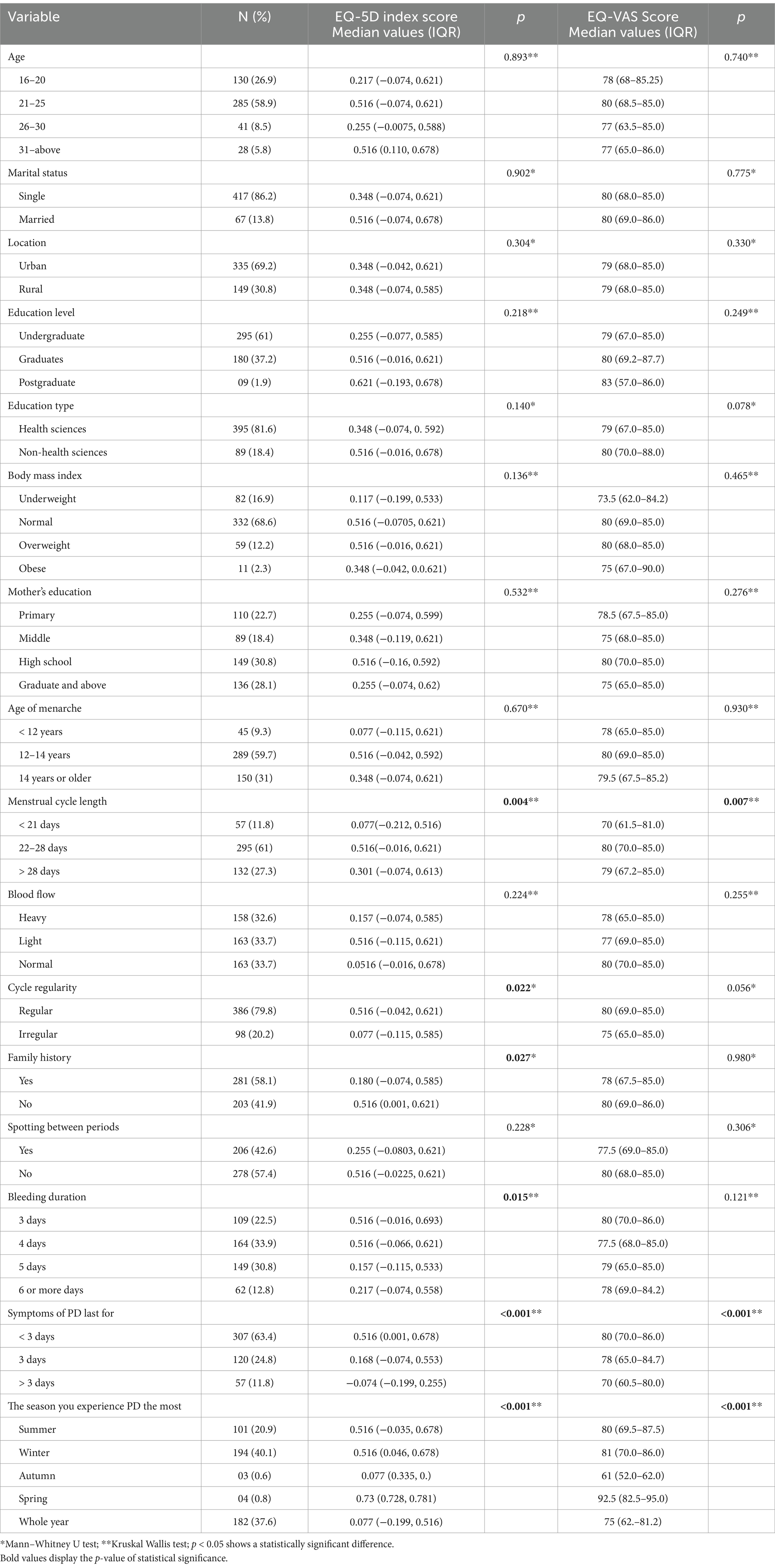

3.2 EQ-5D health status and EQ-VAS score

We observed statistically significant differences in participants’ EQ-5D index scores based on the bleeding duration (p = 0.015), the length of the menstrual cycle (p = 0.004), cycle regularity (p = 0.022), family history (p = 0.027), how long the PD symptoms last (p < 0.001), and the season in which the PD pain is experienced the most (p < 0.001). Moreover, the EQ-VAS score also showed statistically significant differences based on the length of the menstrual cycle (p = 0.007), how long the PD symptoms last (p < 0.001), and the season in which the PD pain is experienced the most (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

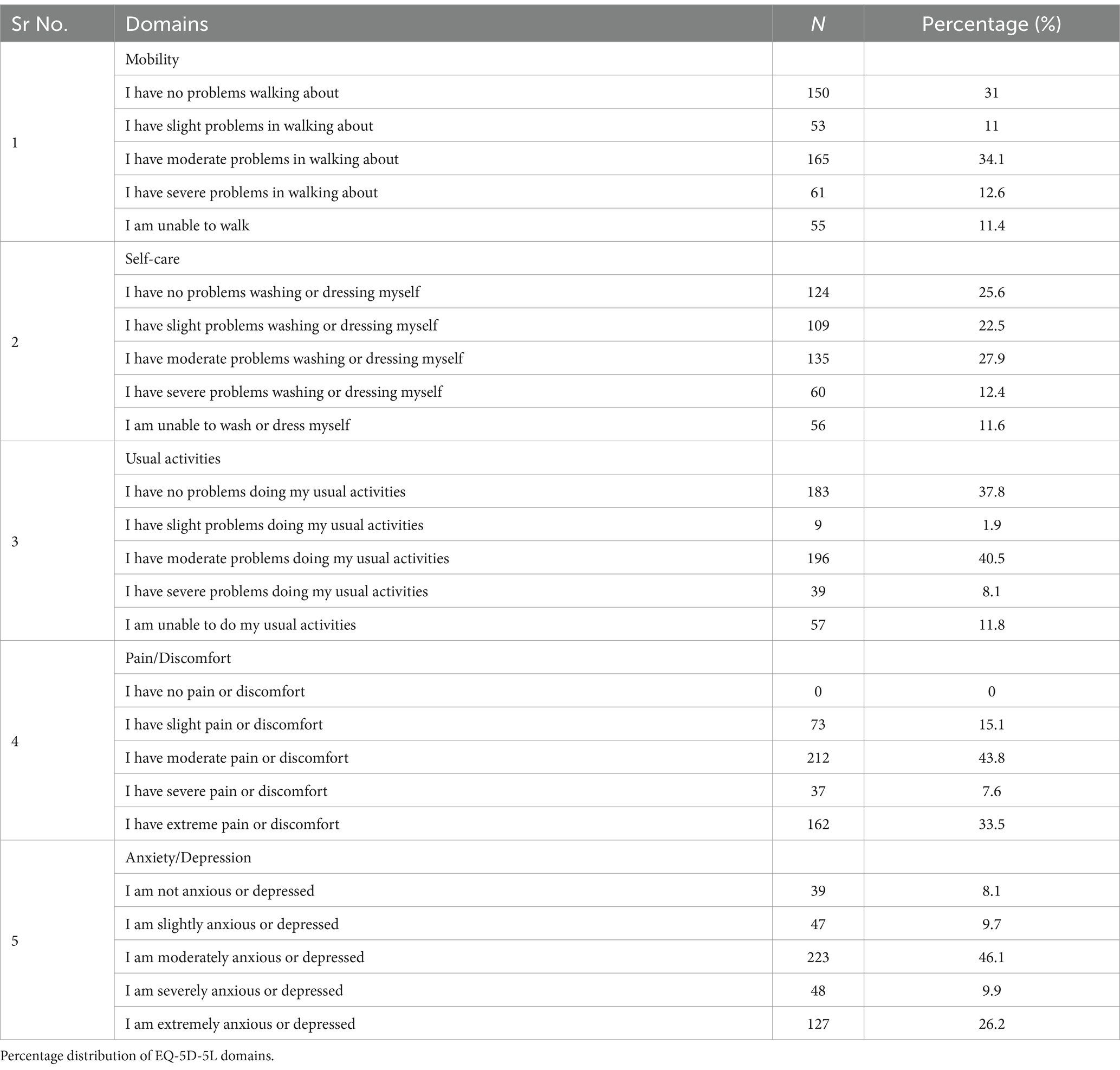

3.3 EQ-5D-5L dimensions

Table 4 presents the percentage distribution of five health dimensions among PD participants. Our study found that the most frequently reported issue among these dimensions was with usual activities, where approximately 40.9% of females experienced moderate problems. In addition, 34.1% reported moderate impairment in mobility, and 27.9% faced moderate issues with self-care. Notably, 33.5% of participants reported experiencing extreme pain or discomfort, while 26.2% indicated being extremely anxious or depressed, as illustrated in Table 4.

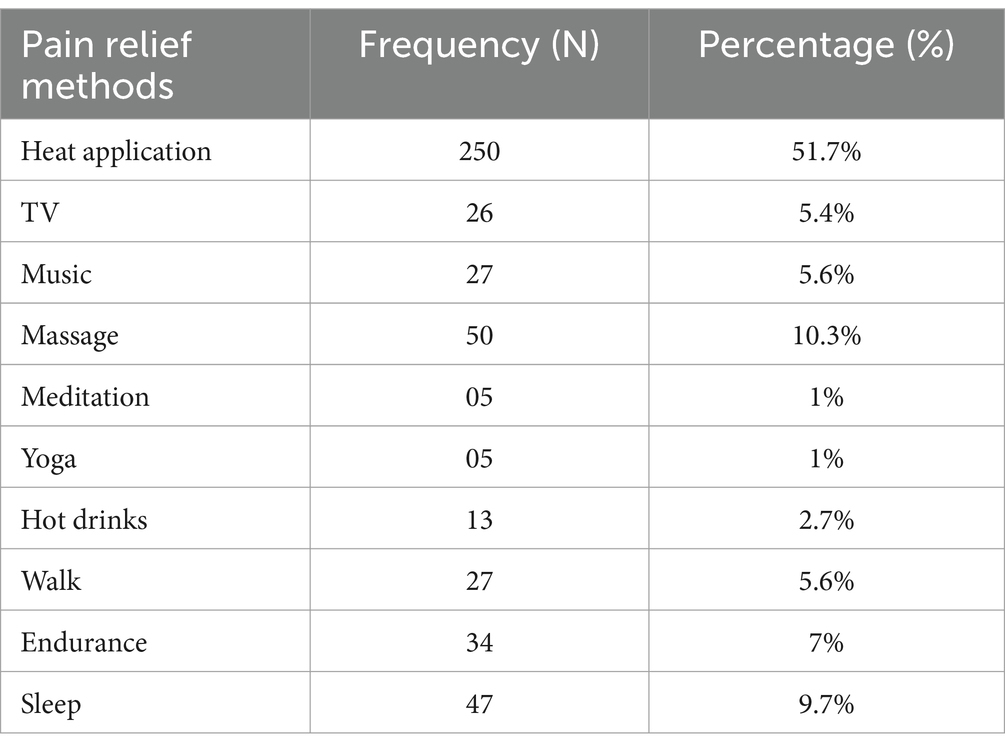

3.4 Measures adopted for pain management

Different lifestyle modification methods were employed for relieving menstrual pain in females. This study revealed that among all participants 51.7% (n = 250) were using heat application method either via hot water bottle or heating patches to relieve their pain, whereas 5.4% (n = 26) tried to divert their attention by watching television and 5.6% (n = 27) listening to music. 10.3% (n = 50) opted for a massage to relieve the pain. Only 1% (n = 05) considered meditation and yoga while hot tea was used by 2.7% (n = 13) females. Moreover, 5.6% (n = 27) chose walking as a pain relief strategy, and 7% % (n = 34) preferred endurance. The remaining 9.7% (n = 47) use sleep as a coping strategy to get comfort during dysmenorrhea as shown in Table 5.

4 Discussion

The objective of this study is to examine how the severity of dysmenorrhea affects the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among female university students in Pakistan. The study reveals a strikingly high prevalence of PD, which may be attributed to a lack of menstrual literacy. This contributes to the baseline data, shedding light on the emotional and physical challenges that Pakistani women face every month, resulting in poor HRQoL across all five domains of EQ-5D-5L: mobility, self-care, usual activities, depression/anxiety, and pain/discomfort. Through the exploration of the relationship between PD and HRQoL of female university attendees, this study uncovers notably a high prevalence of dysmenorrhea, reaching 91.5% which closely aligns with findings from a previous study conducted in a university in Ireland (40), and is comparable to rates observed in King Saud University (80.1%) and females in Nigeria (69.8%) (41, 42). Similarly, the prevalence of PD among Brazilian women was found to be 90.7% in the last menstrual cycle considering mild moderate, and severe pain levels (43). The mean age of the students selected for this study was 22.4 ± 3.5 years, almost similar to an Indian study where the mean age was India (21.99 ± 3.75 years) (44) as Pakistan and India share a close culture and ethnicity. Though Pakistan also shares a close boundary with China the mean age (19.0 ± 1.2 years) was quite different from our study results (20).

From the EQ-5D-5L dimensions, 34.1% experienced moderate impairment in mobility. At the same time, 27.9% reported having moderate problems with self-care. It is worth noting that about 40.9% of females reported moderate problems with usual activities 33.5% of the participants reported extreme pain or discomfort, and 26.2% reported being extremely anxious/depressed, as shown in Table 4.

Regarding pain severity, 30.2% of women in our study reported mild pain, which aligns closely with the reported prevalence among Japanese adult females (33.1%) (13). However, for moderate and severe pain, our study revealed 48.9% moderate and 20.8% reporting severe pain closely following a Saudia study where participants were having moderate 50%, and severe pain 27%, respectively, (41). Overall, the findings from our study suggested that dysmenorrhea significantly impacts the quality of life, affecting not only physical aspects such as mobility and self-care but also influencing usual activities and contributing to pain, discomfort, anxiety, and depression. Additionally, the p-value revealed that EQ-5D index scores were significantly associated with the family history (p = 0.027), cycle regularity (0.022), bleeding duration (0.015), the length of the menstrual cycle (0.004), how long PD symptoms last (< 0.001), and the season in which you experience pain the most (< 0.001). These results were consistent with previously reported literature (3) (see Table 5).

In our study, the prevalence rates of challenges reported in mobility (67.9%), personal care (70.7%), and daily activities (60.3%) among participants. Another study conducted by Fernández-Martínez et al. (45), reported mobility problems (3%), personal care problems (0.7%), manifested problems regarding daily activities, (5.3%) discomfort/pain (16.5%), and 24.2% had problems related to anxiety/depression. Statistical significance was noted between these dimensions and dysmenorrhea in our study, with a p-value of <0.001 for all dimensions of the HRQol scale. The findings of a Spanish study revealed significant differences regarding problems in the dimension of pain and discomfort in women with dysmenorrhea (p = 0.036). However, for the remaining dimensions, statistically significant differences were not found (45). In Jordanian women, dysmenorrhea was found to adversely affect university performance and social attitudes toward family and friends (46). Most female medical students in Saudia Arabia suffer from PD, which adversely affects their quality of life and academic performance (41).

The study further disclosed that 51.7% of females experiencing severe pain use heat application as a method for pain relief, consistent with findings in Ireland (79%) and Spain (68.6%) (45). The same practice of sleep and the application of warm objects on the abdomen was used by midwife trainees and nurses in Ghana to reduce pain (47).

In contrast, a notable 41.8% of Nigerians use the hot water bottle method (42), hot tea was common among Japanese females with severe pain (13). Among other non-pharmacological pain-relieving methods, massage was selected by (10.3%) of our study respondents, whereas 25.9% were reported by a Nigerian study (42). Additionally, only 1% preferred yoga as compared to 5.2% of Spanish females who opted for yoga (45). Interestingly Japanese females seem not inclined toward yoga (13).

Numerous studies reveal that Engaging in exercise, which encompasses endurance and various physical activities, has been recognized as beneficial in managing menstrual pain. In our study, 7% of participants chose endurance, and 9.7% preferred sleep, while in another study almost 8% of individuals experiencing severe and moderate pain utilized mind–body medicine, such as endurance activities and 11% of those with moderate pain addressed their discomfort through sleep (48).

For females who prefer to use analgesics, medical treatment with NSAIDs is advised as the first-line therapy (49–51). They should be started one to 2 days before menstruation, taken with meals to reduce gastrointestinal side effects, followed on a regular dosage schedule, and continued for the first 2 to 3 days of bleeding to achieve the best possible treatment efficacy and safety (50–52). Acetaminophen is a safe analgesic alternative with manageable gastrointestinal side effects; it decreases prostaglandin synthesis and has a mild COX inhibitory action (53). Therefore, acetaminophen is only recommended for mild to moderate dysmenorrheic pain (4). Female patients who do not respond to NSAIDs, hormone-based therapies, or non-pharmacological treatments are considered (54). Levonorgestrel intrauterine systems, subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, combined oral contraceptives (COCs), contraceptive transdermal patches or vaginal rings, and other hormonal therapy methods are effective in treating PD (4).

We employed the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire to assess the impact of dysmenorrhea on QoL among female university attendees, the same instrument was used in a study conducted in Spain (45). The validated questionnaire was selected because it provides a standardized method for assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) across different health conditions (55). Also, there is a substantial body of research supporting the validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, making it a trusted tool in health outcomes research (56). Other investigations have utilized various questionnaires such as the quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire (Q-LES-Q-SF) (57), Short Form-36 (SF-36) (58), and health-related QoL questionnaire WHO/QOL-26 (59). Regardless of the specific scale used, findings consistently indicate a significant impairment in the HRQoL of females experiencing issues with dysmenorrhea across all or certain dimensions of the respective scales.

Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) is a socially taboo topic in Pakistan. Students and teachers have limited access to information about it, MHM (menstrual health and hygiene) is not covered in the curriculum, and Pakistan’s educational system lacks policy guidelines for MHM practices (60). PD should not be seen as a barrier; instead, it can serve as an incentive to research effective solutions for this complaint. This includes exploring both individual treatments and combinations with therapies that have already been validated in scientific studies. In this regard, researchers should aim for consensus while planning their investigations and use reliable methods to improve quality of life.

5 Conclusion

The current study found that PD negatively impacts the overall health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of university students, adversely affecting both their mental and physical health. This research marks the very first attempt in Pakistan to evaluate the HRQoL of females who had complaints of PD, acknowledging the significant influence of lifestyle and cultural background on women’s health and perception of pain.

5.1 Limitations of study

There are certain limitations of the study which should be considered. Although, it is the first study to find the relationship between dysmenorrhea and HRQoL in a group of Pakistani university students, however, we recommend that more research should be conducted in diverse study settings. The study followed a cross-sectional design, implying that the time of the month when participants were asked to complete the questionnaire could potentially influence their results. A numerical pain-related scale (NPRS) has been used to identify the extent of pain and thereby, the classification of pain as mild, moderate, or severe, was solely based on the patient’s understanding of the severity of pain. Despite these limitations, our study is the first to investigate the HRQoL of Pakistani university students. These findings contribute to the development of knowledge on how young women with PD struggle.

5.2 Future recommendations and implications for research

The current study’s strength is that it is the first to evaluate the health-related quality of PD patients. It will assist governments and policymakers in implementing MHH and gaining a profound understanding of the significance of women’s suffering. Researchers should prioritize the need for effective interventions, along with promoting awareness, establishing new accessible treatment options, and facilitating access to medical attention in Pakistan to alleviate the effects of PD and enhance the well-being of women. It is crucial to acknowledge the physical and emotional challenges faced by Pakistani females with dysmenorrhea, recognizing these as gender-based obstacles contributing to poor occupational and economic loss due to women’s absenteeism at work. It necessitates a deep understanding of the significance of MHH by governments and policymakers. In Pakistan to achieve sustainable goals in health, wellbeing, education, and gender equality it requires addressing the gap in MHH. By emphasizing the need for comprehensive policies that address educational and societal aspects related to menstruation to counter menstrual taboo and stigma and improve the overall well-being of women facing menstrual health challenges.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical Review Board of Quaid-i-Azam University (BEC-FBS-QAU2021-265A), Pakistan. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AK: Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing. AA: Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AJ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MH: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. GK: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

1. Harrison, ME, Davies, S, Tyson, N, Swartzendruber, A, Grubb, LK, and Alderman, EM. NASPAG position statement: eliminating period poverty in adolescents and young adults living in North America. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. (2022) 35:609–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2022.07.011

2. Kulkarni, A, and Deb, S. Dysmenorrhoea. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med. (2019) 29:286–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ogrm.2019.06.002

3. Ju, H, Jones, M, and Mishra, G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. (2014) 36:104–13. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxt009

4. Itani, R, Soubra, L, Karout, S, Rahme, D, Karout, L, and Khojah, HM. Primary dysmenorrhea: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment updates. Korean J Fam Med. (2022) 43:101–8. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.21.0103

5. Aktaş, D, Külcü, DP, and Şahin, E. The relationships between primary dysmenorrhea with body mass index and nutritional habits in young women. J Educ Res Nurs. (2023) 20:143–9. doi: 10.14744/jern.2021.93151

6. Martire, FG, Piccione, E, Exacoustos, C, and Zupi, E. Endometriosis and adolescence: the impact of dysmenorrhea. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:5624. doi: 10.3390/jcm12175624

7. Gebeyehu, MB, Mekuria, AB, Tefera, YG, Andarge, DA, Debay, YB, Bejiga, GS, et al. Prevalence, impact, and management practice of dysmenorrhea among University of Gondar Students, northwestern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Med. (2017) 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/3208276

8. Rogers, SK, Ahamadeen, N, Chen, CX, Mosher, CE, Stewart, JC, and Rand, KL. Dysmenorrhea and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2023) 26:719–35. doi: 10.1007/s00737-023-01365-6

9. Rafique, N, and Al-Sheikh, MH. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea and its relationship with body mass index. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. (2018) 44:1773–8. doi: 10.1111/jog.13697

10. Guimarães, I, and Póvoa, AM. Primary dysmenorrhea: assessment and treatment. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. (2020) 42:501–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1712131

11. Iacovides, S, Avidon, I, and Baker, FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update. (2015) 21:762–78. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv039

12. Ferries-Rowe, E, Corey, E, and Archer, JS. Primary dysmenorrhea: diagnosis and therapy. Obstet Gynecol. (2020) 136:1047–58. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004096

13. Mizuta, R, Maeda, N, Tashiro, T, Suzuki, Y, Oda, S, Komiya, M, et al. Quality of life by dysmenorrhea severity in young and adult Japanese females: a web-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0283130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283130

14. Popova-Dobreva, D, Tomova, T, Ivanova, S, and Dakova-Velichkova, T. Relationship between menstrual pain and quality of life. Curr Trends Nat Sci. (2023) 12:241–6. doi: 10.47068/ctns.2023.v12i23.027

15. Armour, M, Parry, K, Manohar, N, Holmes, K, Ferfolja, T, Curry, C, et al. The prevalence and academic impact of dysmenorrhea in 21, 573 young women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Women's Health. (2019) 28:1161–71. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7615

16. Fooladi, E, Bell, RJ, Robinson, PJ, Skiba, M, and Davis, SR. Dysmenorrhea, workability, and absenteeism in Australian women. J Women's Health. (2023) 32:1249–56. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2023.0199

17. Feng, J, Gerrans, P, Moulang, C, Whiteside, N, and Strydom, M. Why women have lower retirement savings: the Australian case. Fem Econ. (2019) 25:145–73. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2018.1533250

18. Hennegan, J, Ola Olorun, FM, Oumarou, S, Alzouma, S, Guiella, G, Omoluabi, E, et al. School and work absenteeism due to menstruation in three west African countries: findings from PMA2020 surveys. Sex Reprod Health Matters. (2021) 29:409–24. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2021.1915940

19. Gutman, G, Nunez, AT, and Fisher, M. Dysmenorrhea in adolescents. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2022) 52:101186. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2022.101186

20. Hu, Z, Tang, L, Chen, L, Kaminga, AC, and Xu, H. Prevalence and risk factors associated with primary dysmenorrhea among Chinese female university students: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. (2020) 33:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.09.004

21. Grandi, G, Ferrari, S, Xholli, A, Cannoletta, M, Palma, F, Romani, C, et al. Prevalence of menstrual pain in young women: what is dysmenorrhea? J Pain Res. (2012) 5:169–74. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S30602

22. Nakao, M, Ishibashi, Y, Hino, Y, Yamauchi, K, and Kuwaki, K. Relationship between menstruation-related experiences and health-related quality of life of Japanese high school students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. (2023) 23:620. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02777-3

23. Curry, C, Ferfolja, T, Holmes, K, Parry, K, Sherry, M, and Armour, M. Menstrual health education in Australian schools. Curr Stud Health Phys Educ. (2023) 14:223–36. doi: 10.1080/25742981.2022.2060119

24. Osonuga, A, and Ekor, M. Risk factors for dysmenorrhea among Ghanaian undergraduate students. Afr Health Sci. (2019) 19:2993–3000. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v19i4.20

25. DeMaria, AL, Delay, C, Sundstrom, B, Wakefield, AL, Naoum, Z, Ramos-Ortiz, J, et al. “My mama told me it would happen”: menarche and menstruation experiences across generations. Women Health. (2020) 60:87–98. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2019.1610827

26. Babbar, K, and Sivakami, M. Promoting menstrual health: towards sexual and reproductive health for all. Obs Res Found. (2023) 613:1–13.

27. Stokes, R, Mikocka-Walus, A, Dowding, C, Druitt, M, and Evans, S. “It’s just another unfortunate part of being female”: a qualitative study on dysmenorrhea severity and quality of life. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. (2023) 30:628–35. doi: 10.1007/s10880-022-09930-4

28. Rasool, S, Tariq, S, Razzak, L, Shabbir, R, Shoaib, N, and Hamid, K. Effect of lifestyle modification upon dysmenorrhea and pain severity in university students of Karachi-prospective study. Pak J Med Health Sci. (2023) 17:51–3. doi: 10.53350/pjmhs202317351

29. Malik, M, Hashmi, A, Hussain, A, Khan, W, Jahangir, N, Malik, A, et al. Experiences, awareness, perceptions and attitudes of women and girls towards menstrual hygiene management and safe menstrual products in Pakistan. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1242169. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1242169

30. Jamil, A, Sheraz, M, Ashraf, S, and Akram, S. Association of Dysmenorrhea with mental health and academic performance among university students. J Univ Coll Med Dent. (2024) 3:13–7. doi: 10.51846/jucmd.v3i1.2752

31. Tsonis, O, Gkrozou, F, Barmpalia, Z, Makopoulou, A, and Siafaka, V. Integrating lifestyle focused approaches into the management of primary dysmenorrhea: impact on quality of life. International. J Women's Health. (2021) 13:327–36. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S264023

32. Gulzar, S, Khan, S, Abbas, K, Arif, S, Husain, SS, Imran, H, et al. Prevalence, perceptions and effects of dysmenorrhea in school going female adolescents of Karachi, Pakistan. Int J Innov Res Dev. (2015) 4:235–40.

33. Yacubovich, Y, Cohen, N, Tene, L, and Kalichman, L. The prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea among students and its association with musculoskeletal and myofascial pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2019) 23:785–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2019.05.006

34. Firdous, S, Mehta, Z, Fernandez, C, Behm, B, and Davis, M. A comparison of numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) and the visual analog scale (VAS) in patients with chronic cancer-associated pain. J Clin Oncol. (2017). 35:217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.31_suppl.217

35. Liu, F, Liu, L, and Zheng, J. Expression of annexin A2 in adenomyosis and dysmenorrhea. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2019) 300:711–6. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05205-w

36. Saleem, F, Hassali, MA, and Shafie, AA. A cross-sectional assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among hypertensive patients in Pakistan. Health Expect. (2014) 17:388–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00765.x

37. Aslam, N, Shoaib, MH, Bushra, R, Asif, S, and Shafique, Y. Evaluating the socio-demographic, economic and clinical (SDEC) factors on health related quality of life (HRQoL) of hypertensive patients using EQ-5D-5L scoring algorithm. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0270587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270587

38. Devlin, NJ, Shah, KK, Feng, Y, Mulhern, B, and Van Hout, B. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5 D-5 L value set for England. Health Econ. (2018) 27:7–22. doi: 10.1002/hec.3564

39. Oppe, M, Devlin, NJ, van Hout, B, Krabbe, PF, and de Charro, F. A program of methodological research to arrive at the new international EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. (2014) 17:445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.04.002

40. Durand, H, Monahan, K, and McGuire, BE. Prevalence and impact of dysmenorrhea among university students in Ireland. Pain Med. (2021) 22:2835–45. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab122

41. Hashim, RT, Alkhalifah, SS, Alsalman, AA, Alfaris, DM, Alhussaini, MA, Qasim, RS, et al. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea and its effect on the quality of life amongst female medical students at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi Med J. (2020) 41:283–9. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.3.24988

42. Esan, DT, Ariyo, SA, Akinlolu, EF, Akingbade, O, Olabisi, OI, Olawade, DB, et al. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and its effect on the quality of life of female undergraduate students in Nigeria. J Endometr Uterine Disord. (2024) 5:100059. doi: 10.1016/j.jeud.2024.100059

43. Barbosa-Silva, J, Avila, MA, de Oliveira, RF, Dedicação, AC, Godoy, AG, Rodrigues, JC, et al. Prevalence, pain intensity and symptoms associated with primary dysmenorrhea: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. (2024) 24:92. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02878-z

44. Unnisa, H, Annam, P, Gubba, NC, Begum, A, and Thatikonda, K. Assessment of quality of life and effect of non-pharmacological management in dysmenorrhea. Ann Med Surg. (2022) 81:104407. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104407

45. Fernández-Martínez, E, Onieva-Zafra, MD, and Parra-Fernández, ML. The impact of dysmenorrhea on quality of life among Spanish female university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:713. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050713

46. Al-Jefout, M, Seham, A-F, Jameel, H, Randa, A-Q, and Luscombe, G. Dysmenorrhea: prevalence and impact on quality of life among young adult Jordanian females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. (2015) 28:173–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.07.005

47. Wuni, A, Abena Nyarko, B, Mohammed Ibrahim, M, Abdulai Baako, I, Mohammed, IS, and Buunaaisie, C. Prevalence, management, and impact of dysmenorrhea on the lives of nurse and midwife trainees in northern Ghana. Obstet Gynecol Int. (2023) 2023:8823525. doi: 10.1155/2023/8823525

48. Samba Conney, C, Akwo Kretchy, I, Asiedu-Danso, M, and Allotey-Babington, GL. Complementary and alternative medicine use for primary dysmenorrhea among senior high school students in the western region of Ghana. Obstet Gynecol Int. (2019) 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2019/8059471

49. Osayande, AS, and Mehulic, S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. (2014) 89:341–6.

50. Burnett, M, and Lemyre, M. No. 345-primary dysmenorrhea consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. (2017) 39:585–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.12.023

51. Hewitt, GD, and Gerancher, KR. ACOG Committee opinion no. 760: dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in the adolescent. Obstet Gynecol. (2018) 132:e249–58. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002978

52. Duggan, KC, Walters, MJ, Musee, J, Harp, JM, Kiefer, JR, Oates, JA, et al. Molecular basis for cyclooxygenase inhibition by the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug naproxen. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:34950–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162982

53. Hinz, B, and Brune, K. Paracetamol and cyclooxygenase inhibition: is there a cause for concern? Ann Rheum Dis. (2012) 71:20–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.200087

54. Oladosu, FA, Tu, FF, and Hellman, KM. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug resistance in dysmenorrhea: epidemiology, causes, and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2018) 218:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.108

55. Liu, X, Chan, WW, Tang, EH, Suen, AH, Fung, MM, Woo, YC, et al. Psychometric properties of EQ-5D-5L for use in patients with graves’ disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2023) 21:90. doi: 10.1186/s12955-023-02177-z

56. Devlin, N, Pickard, S, and Busschbach, J. The development of the EQ-5D-5L and its value sets In: Value sets for eq-5d-5l: A compendium, comparative review & user guide. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology (2022). 1–12.

57. Quick, F, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S, and Mirghafourvand, M. Primary dysmenorrhea with and without premenstrual syndrome: variation in quality of life over menstrual phases. Qual Life Res. (2019) 28:99–107. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1999-9

58. Ozder, A, and Salduz, Z. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea and its effects on female university students’ quality of life: what can we do in primary care. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2020) 13:6496–505. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-89289-0_1

59. Yilmaz, FA, and Dilek, A. Effect of dysmenorrhea on quality of life in university students: a case-control study. Çukurova Med J. (2020) 45:648–55. doi: 10.17826/cumj.659813

Keywords: primary dysmenorrhea, health-related quality of life, university students, cross-sectional study, Pakistan

Citation: Dar M, Khan A, Shah SS, Aleem A, Jaber AAS, Hussain M and Khan GM (2025) Evaluation of health-related quality of life of female students suffering from primary dysmenorrhea: findings of a cross-sectional study from Pakistan. Front. Public Health. 13:1467377. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1467377

Edited by:

Juan Diego Ramos-Pichardo, University of Huelva, SpainReviewed by:

Pentti Nieminen, University of Oulu, FinlandAkmal El-Mazny, Cairo University, Egypt

Francesco Giuseppe Martire, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy

Ario Danianto, University of Mataram, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Dar, Khan, Shah, Aleem, Jaber, Hussain and Khan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gul Majid Khan, Z21raGFuQHFhdS5lZHUucGs=; Amjad Khan, YW1qYWRraGFuQHFhdS5lZHUucGs=

Mamoona Dar

Mamoona Dar Amjad Khan

Amjad Khan Syed Sikandar Shah5

Syed Sikandar Shah5 Ayesha Aleem

Ayesha Aleem Ammar Ali Saleh Jaber

Ammar Ali Saleh Jaber Mulazim Hussain

Mulazim Hussain Gul Majid Khan

Gul Majid Khan