- 1Rocky Mountain MIRECC for Veteran Suicide Prevention, Aurora, CO, United States

- 2Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

- 3Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

- 4VA Brain Health Coordinating Center, VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Aurora, CO, United States

The population of Guam is comprised of a high proportion of Asian and/or Pacific Islander individuals, many of whom have served in the military. Minoritized community membership and military service are associated with increased suicide risk. This mixed-methods study was conducted to increase understanding regarding the community context, factors associated with suicide risk among Guamanians, and implementation barriers and facilitators for a community-based suicide prevention program, Together with Veterans (TWV). For this convergent parallel mixed-methods study, data were collected from twelve individuals. Qualitative data were analyzed via a rapid analysis approach. Themes were organized using a socio-ecological model framework, then integrated with quantitative data. Emergent themes by socio-ecological levels included: intrapersonal (e.g., identities, mental health stigma); social-interpersonal (e.g., perceptions of Veterans); social community (e.g., access to care); social organizational (e.g., hope for raising awareness); social public policy (e.g., part of, yet isolated from, the mainland); and chronosystem (i.e., geopolitical history). Quantitative data yielded convergent and divergent findings. Findings highlight unique risk and protective factors faced by those living in Guam, as well as the utility of structured community-based suicide prevention strategies to make change among those living in island communities that are geographically distant from the mainland.

1 Introduction and context

1.1 Guam

Guam is an island of 209 square miles located in the Western Pacific; nearly 3,700 miles southwest of Hawaii, the closest United States (US) land mass (1). Most residents of Guam identify as Asian and/or Pacific Islander [AAPI; (2)]; specifically, Chamorro or CHamoru, who are indigenous to the Mariana Islands (3), Chuukese, from Chuuk State in Micronesia (4), Filipino, or from other Micronesian communities. Like in other AAPI communities across the US, suicide rates are elevated and rising in Guam (5–7).

Following more than 300 years of Spanish rule, including integration of Catholicism, Guam came under American control in 1898. Guam was governed by the US until 1941, when it was seized by Japan during World War II, and occupied until Allied forces retook the island in 1944. The island served as a vital air and naval base for the US until the end of World War II, and remains an important strategic location for the US military (8).

Guam has a population of 153,836 (9) and is home to a growing number of US military members and Veterans, due to its strategic military location (8, 10). There are approximately 9,700 service members stationed across several bases (11), with an additional 5,000 Marines expected to arrive following the recent reactivation of a Marine Corps base on the island (12). Guamanians have high rates of military service, with 10.5% of the adult population being Veterans (11,927 people), compared to 6.8% at the national level (13).

1.2 Suicide rates

While most Guamanians identify as AAPI, the US Veteran population is comprised of a relatively small percentage of AAPI individuals [i.e., approximately 2%; (14)]. The age- and sex- adjusted suicide rate among Veterans in 2020 was 57% higher than among non-Veteran adults (15). When disaggregated by race, the unadjusted suicide rate among AAPI Veterans was the second highest rate across all racial groups (15), at 30.2 per 100,000 in 2020 (15). Of further concern, the suicide rate among AAPI Veterans increased 167% between 2001 and 2020, a larger increase than among any other racial and ethnic group (15). Another recent analysis of suicide rates among AAPI Veterans also noted high and increasing suicide rates in this population, with suicide rates among those ages 18–34 exceeding those of similarly aged Veterans (16). In addition to elevated and increasing suicide rates among AAPI Veterans, regional differences have been noted (17).

Suicide rates among members of the general population on Guam are also high, with age-adjusted suicide rates of 30.0 and 21.2 per 100,000 in 2020 and 2021 (5). Suicide rates in Guam are further elevated among those who identify as Pacific Islanders, specifically Chuukese or Chamorro, with suicide rates of 50.4 and 23.8, per 100,000, respectively (5). While the overall rate of suicide across the general US has decreased (6), Guam’s rate increased from 2010 to 2020 (5); highlighting the need for increased understanding of factors influencing risk among those living on the island (7).

1.3 Veteran community-based suicide prevention

Suicide prevention is a priority area for the VA, as reflected in the VA National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide, which outlines a public health approach (18). Community-based interventions play a pivotal role in reaching Veterans where they live (18), and implementation often requires leveraging multiple partners and methods. For example, current VA community-based efforts include the Governors’ and Mayor’s Challenges, which engage local and state government and community partners to facilitate interagency suicide prevention planning. VA has also prioritized hiring Community Engagement and Partnership Coordinators, who expand on the work of Suicide Prevention Coordinators by partnering with communities to implement evidence-based suicide prevention strategies (19).

1.4 Together with Veterans

Initially funded in 2015, TWV is a community-based suicide prevention approach for individuals residing in rural settings. Communities receive funding, technical assistance, and coaching support for 36 months to implement evidence-based suicide prevention strategies [i.e., provide suicide prevention training; enhance primary care suicide prevention; promote connectedness and help seeking; improve communication across Veteran-serving programs; enhance behavioral health suicide prevention; promote lethal means safety; (20)] in a manner consistent with the needs of their communities. Thirty-eight communities across 26 US states and territories have implemented TWV. For more information regarding TWV, see Kreisel et al. (21) and Monteith et al. (22).

1.5 Present study

As Guam is unique in many ways, the decision was made to analyze qualitative and quantitative data from this community separately from other TWV communities. Specifically, the present study aimed to increase understanding regarding the community context, and factors associated with suicide risk among those living in Guam, as well as initial considerations regarding barriers and facilitators to implementing TWV. Qualitative themes were organized by socio-ecological model (SEM) framework domains, in which health behaviors are viewed within the context of multiple levels of influence (23, 24). This model has been used to evaluate a wide range of health promotion efforts (24, 25).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants and procedures

Data collection was approved by local review boards. Three members of the study team traveled to Guam in September 2022. All are women, and had previous experience conducting qualitative interviews. None are part of the Guamanian community or identified as AAPI or Veterans. One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of 12 individuals, which included members of the Guam TWV team and other community members who were selected by the TWV community’s leadership team and who were colleagues and peers from various community agencies/groups and were familiar with both the community and the work of TWV, and who agreed to be contacted by our interview team. All participants had indirect or direct community roles related to suicide prevention or associated topics (see demographic details in Table 1). Interviews were conducted in private rooms at a public-serving facility. Members of the study team had been professionally introduced to a few interviewees prior to the visit, and additional interviewees were identified via these contacts, or through the TWV coach.

2.2 Data collected

Interviewers employed an interview guide, which included questions about the experience of living in Guam and community members’ perceptions regarding mental health and suicide prevention. Questions were open-ended, and probes were used as needed to clarify responses (see Supplementary material A1). Interviews (durations ranged from 30 to 90 min) were recorded with permission, and transcribed by a professional transcription service. Informants also completed a demographics questionnaire and three quantitative scales collected using REDCap (26). The Communal Mastery Scale assessed individuals’ beliefs in their ability to attain goals secondary to being interconnected with others (27). Possible total scores ranged from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher communal mastery. The Collective Efficacy Scale (adapted) was administered to obtain information regarding individual beliefs about the capacity of their community to achieve specific goals (28). The possible total score range is 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating belief in the capacity of the community to achieve goals. The TWV Implementation Questionnaire (TWV-IQ) includes questions covering five domains [Planning and Implementation (3 questions); Leadership (5 questions); Community Involvement in the Coalition (6 questions); Progress and Outcome (4 questions)], and Overall Approval (1 question); with two additional binary questions regarding TWV impact on the community and sustainment (see Supplementary Table A2).

2.3 Data analysis

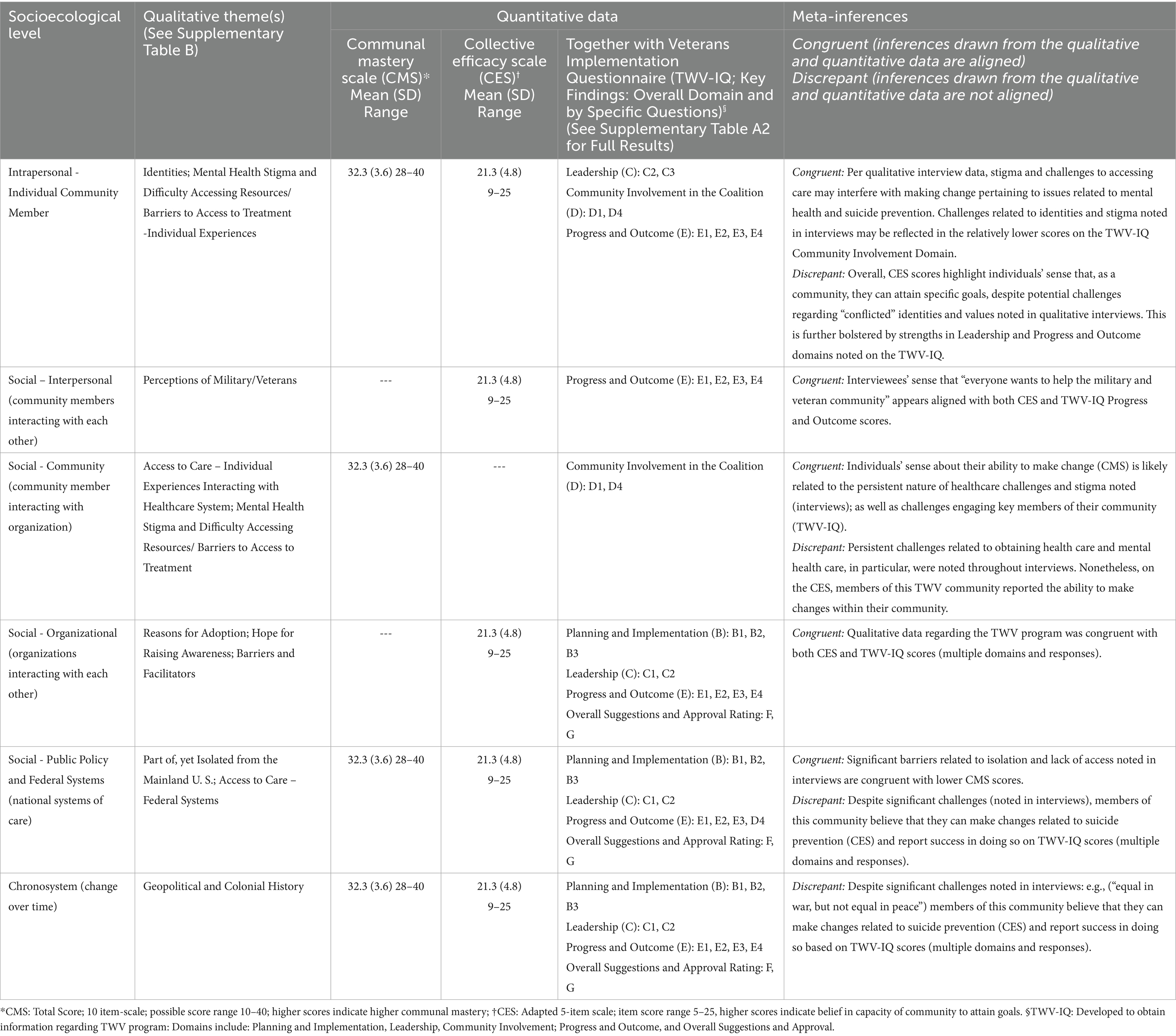

Consistent with best practices for convergent mixed-methods analyses, quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed separately, then synthesized into meta-inferences in a joint display table. Meta-inferences were identified as congruent when inferences were drawn from qualitative and quantitative data that aligned and discrepant when inferences were drawn from data that were not aligned. Following the analysis, qualitative themes, quantitative results, and congruent and discrepant findings are reported (Table 2). For more information regarding mixed-methods employed, see pages 68–77, Creswell and Clark (29). For quantitative data, mean, standard deviation, range, median, and 25th and 75th percentile values were calculated. Frequencies were tabulated for the two binary questions.

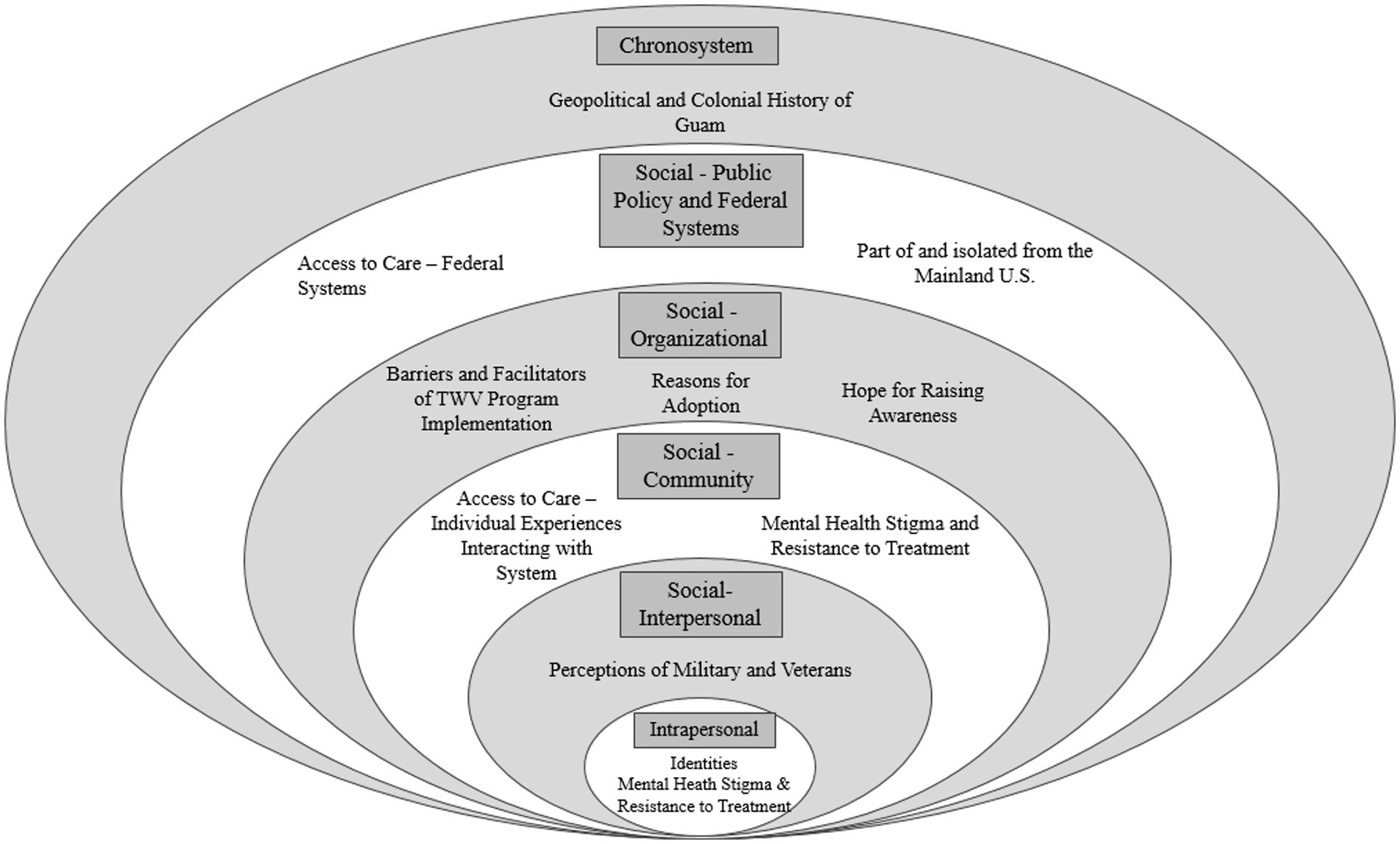

Qualitative interviews were analyzed using an approach developed for health services efforts to obtain actionable, targeted data over a shorter period of time than usually required to process such information (30, 31). All four female analysts, none of whom were Guamanian or identified as AAPI or Veterans, had attained a master’s level education or higher and underwent training in qualitative methods. Each interview was analyzed independently by two individuals. Analysts first organized interview content by questions from the interview guide, extracting quotes and summarizing information into a summary template using neutral domain names and a designated section for additional observations. Each analyst independently reviewed a set of transcripts and associated audio recordings as primary or secondary reviewers and summarized information using the template. The team regularly met during analysis to review emergent themes, ensuring investigator triangulation (32). Themes were derived consensually from interview summaries, and emblematic quotes were selected across interviews. A matrix (33) was then used to further organize themes by SEM framework domains (25, 51) including: intrapersonal; social-interpersonal; social-community; social organizational; social-public policy and federal systems; and chronosystem (see Table 2; Figure 1). More specifically, within the SEM, health behaviors are viewed within the context of multiple levels of influence (24) [e.g., individual behaviors, characteristics of the environment (23). The model has been used to evaluate a wide range of health promotion efforts (24, 25)].

Figure 1. Sociological levels and themes. This figure contains levels including: Intrapersonal: Individual community member. Social-interpersonal: Community members interacting with each other. Social-community: Community members interacting with organization. Social-organizations: Organizations interacting with each other. Social-public policy and federal systems: National systems of care. Chronosystem: Change over time.

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative data

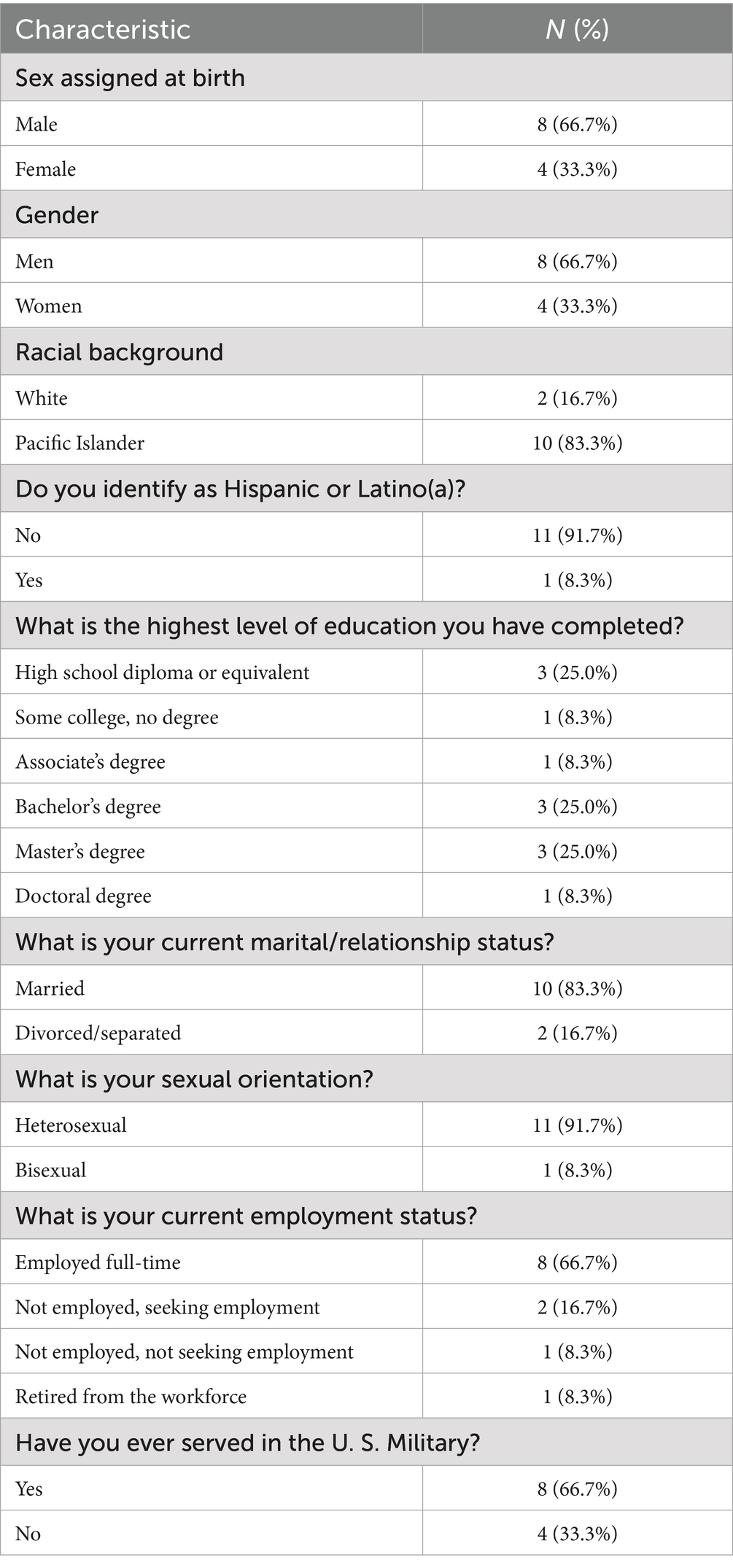

Demographic characteristics for the 12 interviewees are presented in Table 1. Two-thirds (66.7%) of interviewees were male. The majority identified as Pacific Islander (83.3%), and most (66.7%) had served in the US military.

Results [mean (standard deviation)] from surveys were as follows: Communal Mastery Scale, 32.3 [3.6], and Collective Efficacy Scale 21.3 [4.8] (Table 2). TWV-IQ Planning and Implementation, Leadership, and Progress and Outcome domain scores each exceeded 4 on a 5-point scale. Items regarding satisfaction with community involvement were rated the lowest, with a mean of 3.8 [0.8] points (see Table 2; Supplementary Table A2).

3.2 Qualitative data

3.2.1 Intrapersonal-individual (community member)

Two themes emerged within the intrapersonal-individual sphere: (1) internal conflicts experienced by those who identified as both being from Guam and having served in the US military; and (2) internalized mental health stigma and beliefs about seeking treatment. Specifically, interviewees noted shared beliefs and norms between military and Guamanian cultures, which may deter mental health help-seeking behaviors (see Supplementary Table B for illustrative quotes).

3.2.2 Social-interpersonal

This second sphere contained a single theme: (1) perceptions of military servicemembers and Veterans in Guam. Interviewees shared that military service is common among Guamanians and, due to the interconnectedness of the community, most residents know at least one Veteran. Military service is often multigenerational, and Veterans tend to be viewed with pride and respect by the community.

3.2.3 Social-community (community member interacting with organization)

The third sphere included two themes: (1) access to care. Interviewees described frustration Guamanian Veterans experienced when accessing care on the island due to systemic barriers, such as lack of specialty care and residential treatment programs, difficulty navigating care systems, and high provider turnover; and (2) mental health stigma. Interviewees highlighted concerns that seeking mental health care could negatively impact careers. They also noted the prevalence of Catholicism on the island and cited religious beliefs as a contributing factor for stigma around mental health and suicide. Interviewees underscored that mental health stigma was not unique to Guam, but representative of a larger societal phenomenon. Nonetheless, they posited that effective mental health treatment needs to be informed by and responsive to Chamorro culture.

3.2.4 Social-organizational (organization to organization)

Three themes related to the TWV program were noted: (1) reasons for adopting the TWV program; (2) hope for raising awareness regarding suicide prevention and, (3) barriers and facilitators to implementing the TWV program. Interviewees described the community’s desire to foster additional connections with organizations, businesses, and community healthcare. Several interviewees noted the disconnected nature of Veteran services on the island and shared their vision for building partnerships into a web of support for Veterans living in Guam.

3.2.5 Social-public policy and federal systems

Two themes emerged in the Social-Public Policy sphere: (1) dissonance between being part of and separate from the US. In talking about their experiences living in Guam, interviewees contrasted the island’s patriotism and pride in military service with the reality of geographical and cultural isolation from the mainland; and (2) difficulty accessing federal systems of care, including mistrust of government agencies, particularly VA and Department of Defense, as barriers to suicide prevention.

3.2.6 Chronosystem

The Chronosystem encompassed historical events, shifts in sovereign power, and cultural values that have shaped the development of Guam as a community. Interviewees reflected on the impact of their island’s history, culture, and relationship with the US government as part of their experience living in Guam.

3.3 Synthesized data

Meta-inferences drawn from the synthesis of quantitative and qualitative results revealed areas of congruence (inferences drawn from the qualitative and quantitative data are aligned) and discrepancy (inferences drawn from the qualitative and quantitative data are not aligned). Information regarding specific data (qualitative, quantitative) by SEM domains used to make such inferences are presented in Table 2 (Joint Display Table for Mixed-Methods Findings). Overall, results indicated that despite significant challenges, the 12 TWV community members who were interviewed reported the ability to make positive changes within their community, which are expected to help prevent suicide.

4 Discussion

In terms of suicide prevention, those living in Guam face unique needs that arise from a range of socio-ecological factors. Due to limited resources in Guam and persistent barriers to increasing the local mental health workforce, community-based approaches, including culturally tailored suicide prevention efforts that address both individual factors and cultural characteristics (23) are essential to help meet the needs of Guam’s Veterans. Our findings provide initial insights regarding unique cultural considerations for suicide prevention among members of this community. Addressing Guam’s elevated suicide rates will require consideration of the complex identities that Guamanian Veterans experience, drawing on strength and resilience, while addressing stigma and barriers to help-seeking. Stigma related to seeking help may be influenced by military culture (34) and Guamanians’ historical identity of being “warriors” and “fighters”.

Further, membership in community and/or religious organizations may complicate individuals’ beliefs and behaviors regarding suicide. Roman Catholicism is traditionally associated with religious opposition to suicide (35), yet the influence of religion on suicide-related beliefs and behaviors is complex and can vary by individual, group, and country characteristics (36). Nonetheless, those interviewed noted shared community awareness that suicide is a problem and conveyed hope for being able to make a difference in preventing Veteran suicide through TWV. Valuing interconnectedness and a shared sense regarding the community’s ability to facilitate change seemed to be important in terms of individuals’ reported progress toward meeting TWV program outcomes.

A vital component of community-based suicide prevention is identification of those at increased risk for suicide and referral to appropriate levels of care. Moreover, lack of access to care is a known risk factor for suicide (37, 38). Therefore, challenges related to accessing healthcare noted by interviewees were concerning. In terms of VA resources, there is a Community Based Outpatient Clinic on the island; however, the nearest Veterans Administration Medical Center (VAMC) is in Honolulu, Hawaii. For Guamanian Veterans in need of the higher level of care offered at a VAMC, the trip to Honolulu requires approximately 8 h of air travel. Further, continuity of care, including longer term relationships with staff, and working with culturally aware and integrated staff are essential to mental health care (39–41).

To meet the growing demand for mental health services in Guam, increased access to resources (e.g., providers) is needed. However, work by Watanabe-Galloway et al. (42) suggests that providers who have limited experience living in Guam are less likely to be culturally aware of the unique population they serve and are unlikely to stay in the community. As such, novel strategies to train Guamanians in mental health fields or incentivize Guamanians to return home after training in other parts of the world should be explored. One such program, enacted with the passage of the 2022 Biråda Act, offers tuition support to Guamanian graduates of programs leading to health profession degrees who agree to return to Guam as part of a service commitment (43, 44).

Additionally, since the pandemic, VA has made an even greater investment in both telehealth and regionally-available suicide prevention services (45). For example, via the Suicide Prevention 2.0 program, VA providers can refer Veterans for specialized suicide prevention services, including Advanced Safety Planning and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention (19, 46). Nonetheless, many of the individuals providing such services are on the mainland, and internet service is necessary. Continued efforts are needed to overcome such barriers.

Like all studies, the present study has limitations. Data were obtained from a small group of community members, resulting in possible selection bias. Findings are not expected to be generalizable; however, results may be transferable to other community-based suicide prevention efforts (47). Further, interviewers, analysts, and co-authors are not part of the Guam community and could have missed culturally relevant statements and contexts. Finally, due to limited variability of responses on both the CMS and CES, interpretation of these measures is limited. We are also unable to compare our data to other communities because there is a lack of established norms or a categorization scheme for such comparisons.

There are areas of import to explore that were not necessarily the focus of the interview questions. Religion plays a strong role on the island. Catholicism is the majority religious affiliation in Guam (48). Although religious faith is a well-established protective factor for suicide (49), this can vary by race, ethnicity, and gender (36, 50). Future research could further assess the role of religion in suicide risk and prevention in Guam.

The present study provides important insights into the unique mental health and suicide prevention needs of Veterans on Guam, as well as initial feedback regarding implementation of TWV. Additional efforts are needed to foster cultural understanding between the rest of the US and Guam to address intrapersonal, social, and chronosystem-related factors. At the same time, qualitative and quantitative findings support the assertion that, even when significant barriers are identified, belief in community capacity coupled with structured community-based strategies result in the individual perception that change is possible.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the Veterans Health Administration has rules about data security that aim to protect the privacy of Veteran health information. Thus, the data used for this study cannot be made publicly available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bGlzYS5icmVubmVyQHZhLmdvdg==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) at the University of Colorado Denver (UC Denver). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS-Y: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded through an Enterprise Wide Initiative of the VA Office of Rural Health in partnership with the VA Office of Suicide Prevention.

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this manuscript would not be possible without the efforts and contributions of local Veterans and community partners in Guam. We would like to acknowledge the Guam Together with Veterans team for their commitment and efforts to lead their program and providing data for this manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge the team members at the Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) for Suicide Prevention, Alexandra Schneider, Christin Miller, Meghan Barnhart, and Linda Sajbel. Thank you to Natalie Purcell for consulting on qualitative methodology and to Kyle J. Self for editorial assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

This presentation is based on work supported, in part, by the Department of Veterans Affairs, but does not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1469973/full#supplementary-material

References

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. III.B. Overview of the state - Guam - 2021 [WWW document]. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. (2021). Available online at: https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/Narratives/Overview/08312f4f-d1b8-4988-a861-b6aa9678a13e (Accessed October 7, 2023).

2. US Census Bureau. (2022). DECIA Guam demographic profile [WWW document]. Available online at: https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALDPGU2020.DP1?g=040XX00US66&d=DECIA+Guam+Demographic+Profile (Accessed August 11, 2023).

3. Perez, MP. Colonialism, Americanization, and indigenous identity: a research note on Chamorro identity in Guam. Sociol Spectr. (2005) 25:571–91. doi: 10.1080/02732170500176138

4. Diaz, MED. The geopolitical context of Chamorro cultural preservation in Guam, U.S.a. Ethnic Stud Rev. (2012) 35:101–20. doi: 10.1525/esr.2012.35.1.101

5. David, AM. Guam state epidemiological outcomes workgroup, suicide in Guam, 2021. Guam Behavioral Health and Wellness Center. (2022).

6. Ehlman, DC, Yard, E, Stone, DM, Jones, CM, and Mack, KA. Changes in suicide rates - United States, 2019 and 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2022) 71:306–12. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7108a5

7. Monteith, LL, Holliday, R, Iglesias, CD, Sherrill, A, Brenner, LA, and Hoffmire, CA. Suicide risk and prevention in Guam: clinical and research considerations and a call to action. Asian J Psychiatr. (2023) 83:546. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103546

8. US Navy. History [WWW document]. Naval Base Guam. (2023). Available online at: https://jrm.cnic.navy.mil/Installations/NAVBASE-Guam/About/History/ (Accessed October 7, 2023).

9. US Census Bureau. 2020 island areas censuses data on demographic, social, economic and housing characteristics now available for Guam (press release no. CB22-CN.21). (2020).

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. State/territories summary reports - Guam [WWW document]. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. (2017). Available online at: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/stateSummaries.asp (Accessed June 7, 2023).

11. Cagurangan, MV. Military size on Guam quietly grows ahead of the marines’ influx [WWW document]. Pacific Island times. (2022). Available online at: https://www.pacificislandtimes.com/post/military-size-on-guam-quietly-grows-ahead-of-the-marines-influx (Accessed June 7, 2023).

12. Lendon, B. Us marines officially opens first new base in 70 years on island of Guam [www document]. CNN. (2023). Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2023/01/27/asia/new-us-marine-corps-base-guam-intl-hnk-ml/index.html (Accessed November 7, 2023).

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. State summaries Guam [WWW Document]. Open Data. (2019). Available online at: https://www.data.va.gov/stories/s/State-Summaries_Guam/jmm5-cgfz/ (Accessed February 10, 2023).

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran population, population tables - the nation: Race/ethnicity, national center for veterans analysis and statistics [WWW document]. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. (2022). Available online at: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp (Accessed November 7, 2023).

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran suicide data and reporting (National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report: Data appendix). Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. (2022).

16. Monteith, LL, Kittel, JA, Schneider, AL, Miller, CN, Gaeddert, LA, Holliday, R, et al. Suicide among Asian American, native Hawaiian, and Pacific islander veterans: rates and methods, 2005-2019. Am J Prev Med. (2023) 66:243–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.09.006

17. Monteith, LL, Kittel, J, Miller, C, Schneider, AL, Holliday, R, Gaeddert, LA, et al. Identifying U.S. regions with the highest suicide rates and examining differences in suicide methods among Asian American, native Hawaiian, and Pacific islander veterans. Asian J Psychiatr. (2023) 89:103797. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103797

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National strategy for preventing veteran suicide 2018–2028. Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention (2018).

19. Carroll, D, Kearney, LK, and Miller, MA. Addressing suicide in the veteran population: engaging a public health approach. Front Psych. (2020) 11:69. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569069

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Together with veterans (TWV) [WWW document]. MIRECC / CoE. (2023). Available online at: https://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn19/togetherwithveterans/ (Accessed September 20, 2023).

21. Kreisel, CJ, Wilson, LK, Schneider, AL, Mohatt, NV, and Spark, TL. Reducing rural veteran suicides: navigating geospatial and community contexts for scaling up a national veterans affairs program. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2021) 51:344–51. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12710

22. Monteith, LL, Wendleton, L, Bahraini, NH, Matarazzo, BB, Brimner, G, and Mohatt, NV. Together with veterans: VA national strategy alignment and lessons learned from community-based suicide prevention for rural veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2020) 50:588–600. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12613

23. Garney, W, Wilson, K, Ajayi, KV, Panjwani, S, Love, SM, Flores, S, et al. Social-ecological barriers to access to healthcare for adolescents: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:4138. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084138

24. McLeroy, KR, Bibeau, D, Steckler, A, and Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. (1988) 15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401

25. Tyokighir, D, Hervey, AM, Schunn, C, Clifford, D, and Ahlers-Schmidt, CR. Qualitative assessment of access to perinatal mental health care: a social-ecological framework of barriers. Kans J Med. (2022) 15:48–54. doi: 10.17161/kjm.vol15.15853

26. Harris, PA, Taylor, R, Thielke, R, Payne, J, Gonzalez, N, and Conde, JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. (2009) 42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

27. Hobfoll, SE, Schröder, KEE, Wells, M, and Malek, M. Communal versus individualistic construction of sense of mastery in facing life challenges. J Soc Clin Psychol. (2002) 21:362–99. doi: 10.1521/jscp.21.4.362.22596

28. Carroll, JM, Rosson, MB, and Zhou, J. Collective efficacy as a measure of community. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1–10. (2005).

29. Creswell, JW, and Clark, VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications (2017).

31. Lewinski, AA, Crowley, MJ, Miller, C, Bosworth, HB, Jackson, GL, Steinhauser, K, et al. Applied rapid qualitative analysis to develop a contextually appropriate intervention and increase the likelihood of uptake. Med Care. (2021) 59:S242–51. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001553

32. Moon, MD. Triangulation: a method to increase validity, reliability, and legitimation in clinical research. J Emerg Nurs. (2019) 45:103–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2018.11.004

33. Averill, JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. (2002) 12:855–66. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200611

34. Hernandez, SHA, Morgan, BJ, and Parshall, MB. A concept analysis of stigma perceived by military service members who seek mental health services. Nurs Forum. (2017) 52:188–95. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12187

35. Barry, R. The development of the Roman Catholic teachings on suicide. Notre Dame J L Ethics Pub Pol'y. (1995) 9:449.

36. Gearing, RE, and Alonzo, D. Religion and suicide: new findings. J Relig Health. (2018) 57:2478–99. doi: 10.1007/s10943-018-0629-8

37. Tadmon, D, and Bearman, PS. Differential spatial-social accessibility to mental health care and suicide. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2023) 120:e2301304120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2301304120

38. Tondo, L, Albert, MJ, and Baldessarini, RJ. Suicide rates in relation to health care access in the United States: an ecological study. J Clin Psychiatry. (2006) 67:517–23. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0402

39. McGregor, B, Belton, A, Henry, TL, Wrenn, G, and Holden, KB. Improving behavioral health equity through cultural competence training of health care providers. Ethn Dis. (2019) 29:359–64. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.S2.359

40. Waibel, S, Henao, D, Aller, M-B, Vargas, I, and Vázquez, M-L. What do we know about patients’ perceptions of continuity of care? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Qual Health Care. (2012) 24:39–48. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr068

41. Weaver, N, Coffey, M, and Hewitt, J. Concepts, models and measurement of continuity of care in mental health services: a systematic appraisal of the literature. J Psychiatry Ment Health Nurs. (2017) 24:431–50. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12387

42. Watanabe-Galloway, S, Madison, L, Watkins, KL, Nguyen, AT, and Chen, L-W. Recruitment and retention of mental health care providers in rural Nebraska: perceptions of providers and administrators. Rural Remote Health. (2015) 15:3392. Available at: https://www.rrh.org.au/

43. Guam Legislature Archives. 36th Guam legislature [WWW document]. Public law pp. 36–88. (2023). Available online at: https://guamlegislature.com/36th_Guam_Legislature/36th_public_laws_content.htm (Accessed February 10, 2023).

44. Western Interstate Commission of Higher Education. Guam community college opens WICHE PSEP office [WWW document]. Resources. (2023). Available online at: https://www.wiche.edu/resources/guam-community-college-opens-wiche-psep-office/ (Accessed February 10, 2023).

45. Heyworth, L, Kirsh, S, Zulman, D, Ferguson, J, and Kizer, K. Expanding access through virtual care: the VA’S early experience with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. (2020) 1:11. doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0327

46. Gujral, K, Van Campen, J, Jacobs, J, Kimerling, R, Blonigen, D, and Zulman, DM. Mental health service use, suicide behavior, and emergency department visits among rural US veterans who received video-enabled tablets during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e226250. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.6250

47. Konradsen, H, Kirkevold, M, and Olson, K. Recognizability: a strategy for assessing external validity and for facilitating knowledge transfer in qualitative research. Adv Nurs Sci. (2013) 36:66–76. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e318290209d

48. The Association of Religion Data Archives. World religion [WWW document]. National regional profiles - Guam. (2023). Available online at: https://www.thearda.com/world-religion/national-profiles?u=97c# (Accessed December 7, 2023).

49. Ullman, K, Landsteiner, A, Linskens, E, MacDonald, R, McKenzie, L, Murdoch, M, et al. Risk and protective factors across socioecological levels of risk for suicide: An evidence map (no. #09–009). Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. (2021).

50. Barranco, RE. Suicide, religion, and Latinos: a macrolevel study of U.S. Latino suicide rates. Sociol Q. (2016) 57:256–81. doi: 10.1111/tsq.12110

Keywords: Guam, Asian, native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Veteran, suicide prevention, community-based, rural

Citation: Sells JR, Stearns-Yoder KA, Penzenik ME, Bahraini NH, Sullan MJ, Cruz S, Monteith LL and Brenner LA (2025) The “tyranny of distance”: community-based veteran suicide prevention in Guam. Front. Public Health. 13:1469973. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1469973

Edited by:

Tingzhong Yang, Zhejiang University, ChinaReviewed by:

Anthony R. Carlini, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesRichard Greggory Johnson III, University of San Francisco, United States

Copyright © 2025 Sells, Stearns-Yoder, Penzenik, Bahraini, Sullan, Cruz, Monteith and Brenner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joanna R. Sells, Sm9hbm5hLnNlbGxzQHZhLmdvdg==

Joanna R. Sells

Joanna R. Sells Kelly A. Stearns-Yoder

Kelly A. Stearns-Yoder Molly E. Penzenik

Molly E. Penzenik Nazanin H. Bahraini

Nazanin H. Bahraini Molly J. Sullan1,2,4

Molly J. Sullan1,2,4 Lisa A. Brenner

Lisa A. Brenner