- Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Cancer Center, Chongqing University Cancer Hospital, Chongqing, China

Introduction: Although negative workplace behavior as a key factor in healthcare staff turnover intention was well established, the mechanisms by which negative workplace behavior affects turnover intention are unclear. Extending the affective event theory, we aimed to (a) identify the interrelationships between negative workplace behavior, job insecurity, psychological resilience, and turnover intention in the healthcare setting and (b) clarify the mechanism among these variables.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted in China from February to April 2023 utilizing a quota sampling method. The Chinese version of the negative behaviors in health care survey, the workplace insecurity scale, the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, and the turnover intention scale were used to investigate.

Results: The survey resulted in 1,180 valid responses. Results were consistent with our hypothesized framework in which healthcare workers' turnover intention was significantly and positively influenced by negative workplace behavior (β = 0.251, p < 0.01) and job insecurity (β = 0.322, p < 0.01). Job insecurity partly mediated the association between negative workplace behavior and turnover intention, which were significantly moderated by psychological resilience (β = −0.041, p < 0.05).

Conclusions: Negative workplace behavior is critical in turnover intention among healthcare workers. One important consideration for hospital administrators and health policymakers is creating a peaceful and harmonious workplace to reduce the risk of unfavorable workplace conduct and turnover intention toward healthcare personnel. An essential psychological resilience-improving program should be developed to reduce the damage of negative workplace behavior and job insecurity against healthcare workers.

1 Introduction

The shortage of healthcare workers is a serious and complex issue faced by the global healthcare system (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) noted that 12.9 million healthcare professionals will be short worldwide by 2035 (2). It has been observed that hospital nurses in various countries (such as Jordan, China) experience elevated levels of job burnout, heavy workloads, and a propensity to consider leaving their positions (3, 4). According to a survey from American Nurses Foundation indicated that 23% registered nurses intended to leave their position and 29% were considering leaving their current position within the next 6 months attributed to the pandemic, high job demands and burnout (5, 6). Turnover intention, defined as a conscious and deliberate willingness to leave the organization, is one of the major factors contributing to employee resignations and the strongest indicator that can predict an individual's turnover behavior (7). Studies confirmed that the high turnover rate of healthcare professionals increase costs and contribute to instability in the work environment owing to healthcare worker shortages (7, 8). The cost of employee turnover is thought to be associated with a minimum of 5% of the annual revenue loss (9). Research showing the high cost of turnover and recruitment reflects the importance of employment stability. Turnover intentions of healthcare workers may predict turnover behavior which deserves further attention and investigation.

1.1 Internal relationships between negative workplace behavior and turnover intention

A growing body of studies highlighted that one vital factor affecting the turnover intention of healthcare staff is the work environment (1). Workplace violence by patients or family members has received wide attention, but negative workplace behavior within the organization has been generally ignored. Negative workplace behavior involves psychological and physical hostility within the work environment that is pervasive and far-reaching for both the organization and its members (10). It can be divided into horizontal aggression between peers and vertical aggression between a leader and follower according to the directionality of the behavior (11). Due to the potential conflicts of interest and high-pressure work environments, negative behaviors within organizations can lead to endless stress and sustained pain for medical staff, which is no less harmful in the long run than bullying or violence from patients and family members (12). The unfavorable consequences of negative workplace behavior on turnover intention are well documented in past research (13). Previous studies have found that negative workplace behavior resulted in destroyed the harmonious atmosphere of the hospital (12), hindered healthcare workers' teamwork (14), and ultimately affected the safety of patients (15).

Although there is growing evidence that workplace incivility is an important predictor of various types of turnover intention, little is known about the association between negative workplace behavior and turnover intention among healthcare workers (16). Affective events theory (AET) can provide valuable insights for understanding the relationship between negative workplace behavior and turnover intention, which assumes that the work environment indirectly alters work attitudes by influencing work events (17). Negative workplace behavior from peers or leaders can impact healthcare professionals' working attitudes increasing the probability of turnover. Therefore, we attempt to explore the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Negative workplace behavior has a positive association with healthcare workers' turnover intention.

1.2 The mediating role of job insecurity

Job insecurity refers to an individual's beliefs about the degree to which they fear losing their current job and the necessity of maintaining employment stability (18). The degree to which workers feel their employment is in jeopardy is reflected in their level of job insecurity (19). According to Hellgren et al. (20), there are two types of work insecurity: qualitative job insecurity, which refers to feelings of loss of important employment qualities, and quantitative job insecurity, which is based on subjective evaluations of the possibility of losing one's job. Previous study found that negative workplace behavior is a risk factor for job insecurity (21). Aisha Sarwar's study also revealed the link between job insecurity linking workplace bullying and nurse's deviant work behavior (13). Moreover, some scholars confirmed that workplace violence was positively related to healthcare workers' job insecurity. Few research, nevertheless, have looked at the possible mediating mechanisms that underlie the links between negative workplace behavior and turnover intention through job insecurity.

AET assumes that the work environment indirectly alters work attitudes by influencing work events, which subsequently trigger affective experiences (17). It offers a framework for investigating how job insecurity plays a significant role in mediating the relationship between negative workplace behavior and turnover intention (17). Events that occur to people in work environments and elicit feelings are referred to as work events (such as negative workplace behavior). Affective experiences are the feelings—whether favorable or unfavorable—that arise from work-related situations (such as job insecurity). Workplace attitudes (such as turnover intention) are directly impacted by the affective experience. Wu et al. (22) tested AET in a sample of 1,517 hospital nurses in China and found work environment was related to job satisfaction and intention to leave both directly and indirectly through two mediators: workplace violence and burnout. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2: Job insecurity mediates the association between negative workplace behavior and turnover intention.

1.3 The moderating effect of psychological resilience

Psychological resilience is a psychological resource and stable personality trait that helps people deal with and overcome failure or adversity (23). A complicated and dynamic process, resilience involves nurses developing coping mechanisms to reduce psychological discomfort and problem-solving techniques to deal with occupational adversity (24). AET holds that personal traits can regulate the relationship between work events and affective experience (17). Healthcare professionals that possess psychological resilience are more likely to handle work-related stressors and experience personal development owing to they are more likely to mobilize internal modifications and utilize external resources (25). Furthermore, previous studies confirmed that the psychological health of emergency nurses may suffer from high rates of workplace violence, whereas resilience can help them lessen negative effects (26). Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3: Psychological resilience moderates the association between negative workplace behavior and job insecurity such that this positive relationship is stronger when the victim's psychological resilience is low.

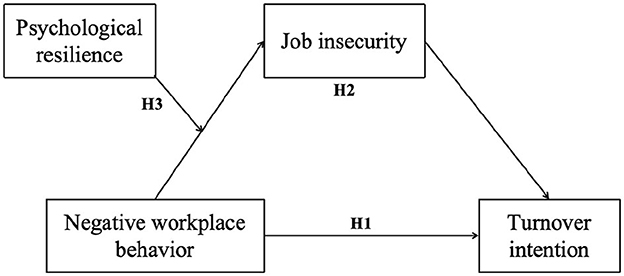

Based on the above literature review, the purpose of this study was to examine whether negative workplace behavior would have both direct and indirect effects on turnover intention through job insecurity and whether psychological resilience, as a positive resource, plays a moderating role in the process of negative workplace behaviors affecting job insecurity (Figure 1).

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and procedures

We used a quota sampling method to collect data, 1,108 healthcare workers were recruited between February and April 2023 from three tertiary hospitals in Hunan Province, China. According to data from the China Statistical Yearbook 2020, the ratio of medical personnel (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, technicians) was 1:1.52:0.12:0.13 (27). Therefore, we recruited 400 doctors, 608 nurses, 48 pharmacists, and 52 technicians. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) medical personnel with relevant qualifications; (2) working time of more than 3 months; (3) signed informed consent and were voluntarily willing to participate in this study. Trainees, interns, and those who could not cooperate in completing this study were excluded. The head of nursing at three hospitals sends other nurses a link to our self-administered questionnaire via Wenjuanxing (a professional online questionnaire platform in China, https://www.wjx.cn/). On the front page of self-administered questionnaires, they were then clearly informed of the goal and relevance of this study, and their participation was kindly requested.

The required sample size was calculated using the formula . The type I error α was set as 0.05, the Zα/2 was set as 1.96, and the absolute error δ was set as 0.03. π = 50% was set for calculation in order to ensure sufficient size for cross-sectional study (28). A sample size of 961 was derived, and a minimum sample size of 1,057 was required given a 10% of invalid responses. Thus, 1,108individuals were recruited, which was sufficient to satisfy the cross-sectional survey's sample size requirements.

2.2 Variables and measurements

2.2.1 General information questionnaire

The general information questionnaire was designed by looking through relevant research and the researchers' clinical expertise. Healthcare workers' demographic characteristics were collected. The information included age, gender, working years, marital status, education, and field.

2.2.2 Negative workplace behavior

This study used the Chinese version of the NBHC questionnaire developed by Layne et al. (11). It was a specific tool designed to measure the negative workplace behaviors among healthcare professionals. The Chinese version of the scale included 23 items in 4 dimensions and 2 open-ended questions, including contributing factors (7 items), frequency of aggression (7 items), the severity of aggression (6 items), fear of retaliation (3 items), and 2 open-ended questions to describe medical staff's experience of negative behavior and suggestions for reducing negative behavior in the workplace. The dimensions of contributing factors and fear of retaliation were scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”). The attack frequency dimension was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“every day”). The attack severity dimension was scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not serious”) to 4 (“very serious”). The score of each dimension is the average score of all items in this dimension. The higher the score, the more serious the problem of negative behavior in the workplace. In this study, Cronbach's α of the total scale was 0.92.

2.2.3 Job insecurity

The workplace insecurity scale (WIS) was developed by Hellgren et al. (20) and measures employees' fears about losing their jobs and their perceptions of threats to the quality of the employment relationship. It consists of 7 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), with total scores ranging from 7 to 35. A higher score represented higher levels of job insecurity experienced by the individual. The reliability of the Chinese version of the WIS was acceptable for the subscales (Cronbach's α = 0.949–0.903), and construct validity was good (29). The Cronbach's α was 0.96 for the total scale and 0.79–0.93 for five subscales in the present study.

2.2.4 Psychological resilience

The 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) is a self-report measure designed for measuring resilience (30). The Chinese 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale was used in this study, which consists of 10 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not true at all”) to 4 (“true nearly all the time”) (31). The CD-RISC-10 generates total scores from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating a greater ability to cope with adversity (32). This scale reported a good internal consistency (33). In this study, Cronbach's α of the total scale was 0.92.

2.2.5 Turnover intention

Mobley developed the turnover intention scale in 1978 (34). The Chinese version of the turnover intention scale was used, which contains 4 items and uses the Likert-5 scale ranging from 1 (“completely inconsistent”) to 5 (“completely consistent”), with total scores ranging from 4 to 20 (35). A higher score indicated greater turnover intention. In this study, Cronbach's α of the total scale was 0.97.

2.3 Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 and PROCESS. The correlation between the research variables was calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The impact of this model was to be assessed by multiple linear regression analyses. Based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples, this study calculated the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI). A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for all variables.

2.4 Ethics approval

The study complied with acknowledged ethical guidelines, as stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study received ethical approval from the Behavioral Medicine and Nursing Research Ethics Review Committee of Central South University (No. E E202217). Before starting data collection, electronic informed consent was obtained.

3 Results

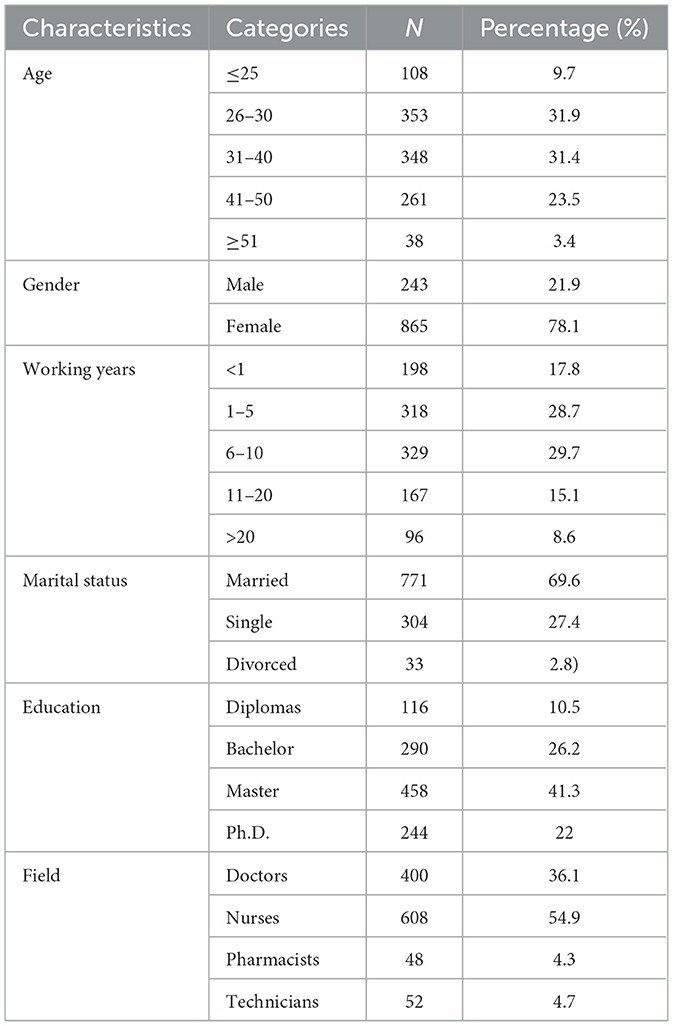

3.1 Healthcare workers' demographic information

The majority of the participants (78.1%) were female, 26–30 years (31.9%). Most of the healthcare professionals had master's degrees (41.3%), followed by bachelor's degrees (26.2%), doctor's degrees (22.0%) and diplomas (10.5%). The present professional categories of the samples were nursing (54.9%), medicine (36.1%), pharmacy (4.3%), and technic (4.7%). The rest of the general data information is detailed in Table 1.

3.2 Correlations between study variables

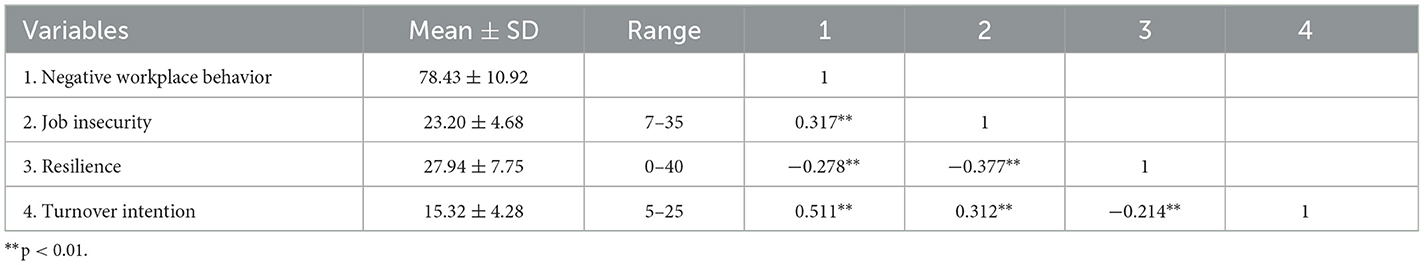

The descriptive statistical analysis results are shown in Table 2. Negative workplace behavior is significantly positively correlated with job insecurity (r = 0.317, p < 0.01). Job insecurity was positively correlated with turnover intention (r = 0.312, p < 0.01). There was a significant positive correlation between workplace negative behavior and turnover intention (r = 0.511, p < 0.01). This provides preliminary support for the hypothesis of this study.

3.3 Multiple hierarchical linear regression models

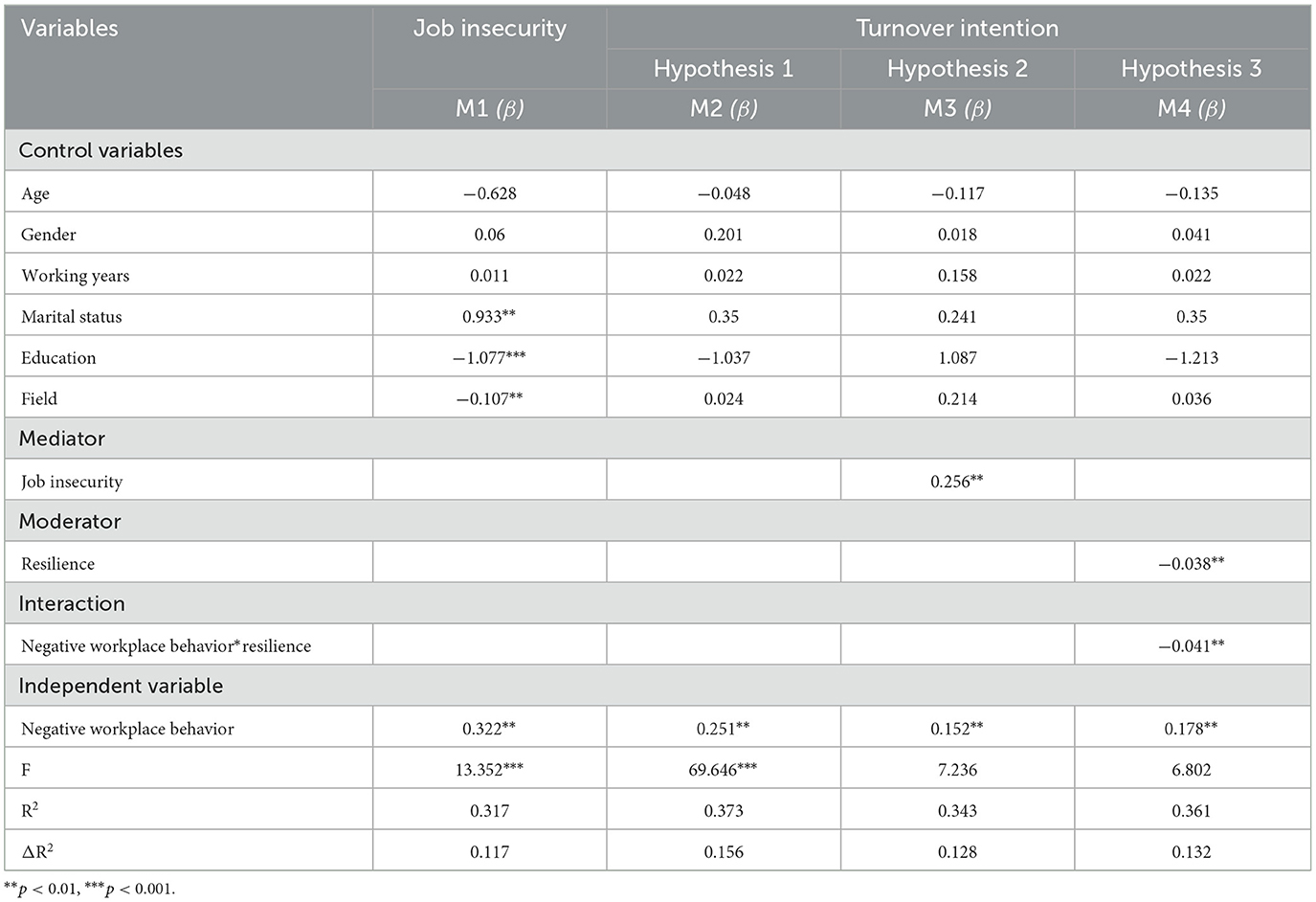

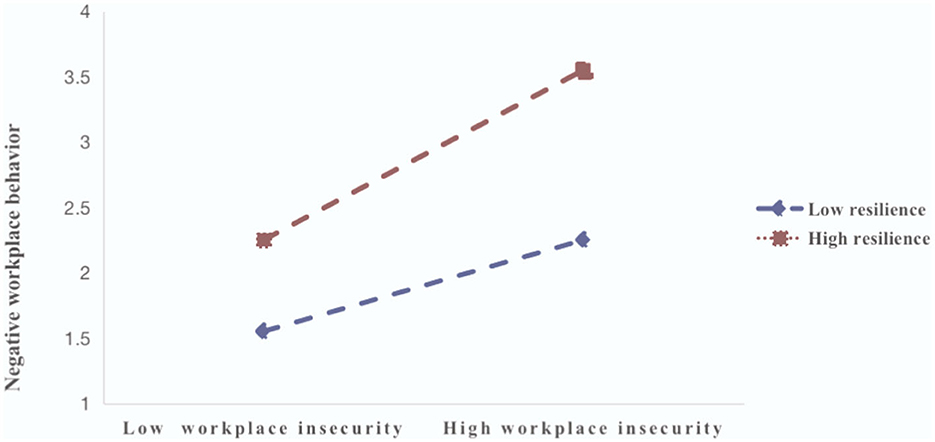

We performed multiple linear regression analyses to examine our hypotheses, testing the associations between negative workplace behavior, job insecurity, psychological resilience, and turnover intention, after adjusting for gender, age, marital status, education, and working year. Such variables were regarded as the control variables. Job insecurity was tested as a potential mediator of the association between negative workplace behavior and turnover intention. We tested the mediator via the PROCESS procedure for SPSS 22.0 by calculating bias-corrected 95% confidence using bootstrapping with n = 5,000 resamples. Negative workplace behavior was positively associated with job insecurity (β = 0.322, p < 0.01) and turnover intention (β = 0.251, p < 0.01); H1 and H2 were supported, as shown in Table 3. It showed that resilience significantly moderated the association between negative workplace behavior and work insecurity in Table 3 and Figure 2, so H3 was confirmed.

Figure 2. Moderated effect of resilience on the association between negative workplace behavior and job insecurity.

4 Discussion

The study results support the hypothesized model. Negative workplace behaviors positively influence Chinese healthcare professionals' turnover intention and job insecurity mediates their relationship. Furthermore, our research confirmed that psychological resilience moderates the association of negative workplace behaviors with job insecurity. Our research findings increase the understanding of how negative workplace behaviors influence turnover intention. A better understanding of this mechanism could provide a scientific basis for the prediction of nurse turnover intention and possible preventive measures.

As shown in our results, high negative workplace behaviors were related to increased turnover intention. This is consistent with previous research results, suggesting better work environment standards (e.g., true collaboration, authentic leadership) are associated with decreased turnover intention and improved employee satisfaction (36, 37). According to the theory of general aggression model, a person experiencing aggressiveness will go through three main stages: cognitive, physiological arousal, and emotional traits (38). This suggests that when healthcare workers experience negative workplace behaviors, they will engage in cognitive processing, which could result in emotional reactions like resentment and fear and eventually evolve into turnover intention (1). Preventing negative workplace behaviors is a potential strategy to reduce healthcare professionals' turnover intention. Therefore, it is recommended that hospitals set up psychological supervisory teams and form mental health departments for medical workers to reduce work stress and negative emotions by helping medical staff to channel their emotions. Our results add evidence to the importance of preventing negative workplace behaviors for reducing nurses' turnover intention.

Although the effect of negative workplace behaviors on turnover intention has been previously examined, little is known about the underlying mechanisms by which negative workplace behaviors cause their victims to intend to leave. We found evidence in favor of job insecurity as one of the mediators explaining how healthcare personnel's negative workplace behaviors develop and lead to them engaging in turnover intention. The inclination to leave the job rises in healthcare professionals who experience negative workplace behaviors as their perception of job security correspondingly declines. This is consistent with recent meta-analysis research on job insecurity that highlights the multilevel antecedents and consequences of job insecurity (39). Employing the AET theory, job insecurity, as a negative affective experience, is a key point in understanding how events occurring in the work environment affect the behavior of employees. Additionally, the conservation of resource theory states that nurses would devote significant psychological, physiological, and emotional resources to preserving and safeguarding their work, which is inherently important to them if they perceive a threat to the stability or continuity of their employment. But if their efforts are in vain, they will get emotionally weary (18). Negative workplace behaviors, particularly vertical aggression from superiors, can cause medical personnel to worry about job security, future career development, and job rewards when these issues are not handled, they are more likely to quit their job.

Moderation analysis supported the moderation effect of resilience among the negative relationship between negative workplace behaviors and job insecurity. The findings of this study in concert with findings from previous studies demonstrated that medical staff's resilience lessened the detrimental effects of negative workplace behaviors (23). In addition to actively resisting the negative affective experience, healthcare workers who engaged in negative workplace behaviors also actively mobilized their psychological capital and personality resources to counteract the negative affective experience (40). This provided the theoretical foundation for the development of prevention and intervention strategies aimed at halting the detrimental effects of negative workplace behaviors on healthcare workers.

High turnover among healthcare workers impairs patient and worker outcomes and incurs significant financial costs; therefore, nurse managers and organizations should actively investigate factors influencing turnover and develop strategies to prevent turnover. Our study highlighted the adverse outcomes of negative workplace behaviors in the healthcare workplace, including a mechanism to break the vicious circle of high turnover intention among healthcare workers. Mitigating negative workplace behaviors is a key factor in preventing job insecurity, and ultimately reducing the turnover rate of medical staff. Hospital administrator and nurse managers are encouraged to actively engage in the development and enforcement of negative workplace behavior prevention protocols and the building of a harmonious working environment involves the harmonious relationship between colleagues, the superior, and the subordinate. Furthermore, managers should also pay attention to the key role of psychological resilience as a moderator in preventing job insecurity among medical staff, by organizing positive psychology knowledge lectures to help them cultivate confidence and positive attitudes and improve their ability to self-regulate their emotional state.

4.1 Limitation

The current study, like all studies, is not free from limitations. First, due to its cross-sectional nature, we were unable to draw causal relationships among negative workplace behaviors, job insecurity, resilience, and turnover intention. To validate and expand upon our findings, longitudinal data are required. Second, self-reports were used to gather all data, a process that incurs unavoidable reporting or recall bias. Future research with more objective data, including hospital turnover rates, might help confirm the results. Third, the participants were recruited from three tertiary hospitals and the sample size was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should consider broadening the sample's geographical scope.

5 Conclusion

Our research revealed that negative workplace behaviors are important factors contributing to employee turnover intention. Job insecurity mediates the relationship between negative workplace behaviors and turnover intention, which indicates reducing healthcare workers' job insecurity is vital to preventing high turnover intention among medical staff. Additionally, psychological resilience moderates the association between negative workplace behaviors and job insecurity.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study received ethical approval from the Behavioral Medicine and Nursing Research Ethics Review Committee of Central South University (No. E E202217). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JZo: Writing – original draft. YY: Writing – review & editing. LC: Writing – review & editing. YB: Writing – review & editing. NL: Writing – review & editing. QL: Writing – original draft. JZh: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Chongqing Science and Health Joint Medical Scientific Research Project Youth Project (2025QNXM032), Technological Innovation Project of Chongqing Shapingba District (2024135), and the Chinese Nursing Association 2023 Research Program (ZHKY202311).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the participants and researchers involved in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Liang L, Wang Z, Hu Y, Yuan T, Fei J, Mei S. Does workplace violence affect healthcare workers' turnover intention? Jpn J Nurs Sci. (2023) 20:e12543. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12543

2. The World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030. (2024). Available online at: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-07/global-strategy-on-hrh-english.pdf (accessed March 11, 2024).

3. Alzoubi MM, Al-Mugheed K, Oweidat I, Alrahbeni T, Alnaeem MM, Alabdullah AAS, et al. Moderating role of relationships between workloads, job burnout, turnover intention, and healthcare quality among nurses. BMC Psychol. (2024) 12:495–501. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-01891-7

4. Li Y, Zheng X, Yang Z, Yan W, Li Q, Liu Y, Wang A. The mediating effect of job burnout on the relationship between practice environment and workplace deviance behavior of nurses in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. (2025) 24:19–28. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-02663-9

5. American Nurses Foundation. COVID-19 Impact Assessment Survey—The Second Year. (2015). Available online at: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/covid-19-impact-assessment-survey—the-second-year/ (accessed January 20, 2015).

6. Woodward KF, Willgerodt M. A systematic review of registered nurse turnover and retention in the United States. Nurs Outlook. (2022) 70:664–78. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2022.04.005

7. Yildiz B, Yildiz H, Ayaz Arda O. Relationship between work-family conflict and turnover intention in nurses: a meta-analytic review. J Adv Nurs. (2021) 77:3317–30. doi: 10.1111/jan.14846

8. Berger S, Grzonka P, Frei AI, Hunziker S, Baumann SM, Amacher SA, et al. Violence against healthcare professionals in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis of frequency, risk factors, interventions, and preventive measures. Crit Care. (2024) 28:61–74. doi: 10.1186/s13054-024-04844-z

9. Waldman JD, Kelly F, Arora S, Smith HL. The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Manage Rev. (2010) 35:206–12. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181e3940e

10. Verschuren CM, Tims M, de Lange AH. A systematic review of negative work behavior: toward an integrated definition. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:726973. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.726973

11. Layne DM, Nemeth LS, Mueller M, Wallston KA. The negative behaviors in healthcare survey: instrument development and validation. J Nurs Meas. (2019) 27:221–33. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.27.2.221

12. Hawkins N, Jeong S, Smith T. New graduate registered nurses' exposure to negative workplace behaviour in the acute care setting: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2019) 93:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.09.020

13. Sarwar A, Naseer S, Zhong JY. Effects of bullying on job insecurity and deviant behaviors in nurses: roles of resilience and support. J Nurs Manag. (2020) 28:267–76. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12917

14. Schwappach D, Richard A. Speak up-related climate and its association with healthcare workers' speaking up and withholding voice behaviours: a cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. BMJ Qual Saf. (2018) 27:827–35. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007388

15. Layne DM, Nemeth LS, Mueller M, Martin M. Negative behaviors among healthcare professionals: relationship with patient safety culture. Healthcare. (2019) 7:1–11. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7010023

16. Namin BH, Øgaard T, Røislien J. Workplace incivility and turnover intention in organizations: a meta-analytic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 19:25. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010025

17. Weiss HM, Cropanzano R. Affective events theory: a theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In:Staw BM, Cummings LL, edit, , ed. Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press (1996). p. 1–74.

18. Liu Y, Yang C, Zou G. Self-esteem, job insecurity, and psychological distress among Chinese nurses. BMC Nurs. (2021) 20:141. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00665-5

19. Jia X, Liao S, Yin W. Job insecurity, emotional exhaustion, and workplace deviance: The role of corporate social responsibility. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1000628. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1000628

20. Hellgren J, Sverke M, Isaksson K. A two-dimensional approach to job insecurity: consequences for employee attitudes and well-being. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. (1999) 8:179–95. doi: 10.1080/135943299398311

21. Yam KC, Tang PM, Jackson JC, Su R, Gray K. The rise of robots increases job insecurity and maladaptive workplace behaviors: Multimethod evidence. J Appl Psychol. (2023) 108:850–70. doi: 10.1037/apl0001045

22. Wu Y, Wang J, Liu J, Zheng J, Liu K, Baggs JG, et al. The impact of work environment on workplace violence, burnout and work attitudes for hospital nurses: A structural equation modelling analysis. J Nurs Manag. (2020) 28:495–503. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12947

23. Li L, Liao X, Ni J. A cross-sectional survey on the relationship between workplace psychological violence and empathy among Chinese nurses: the mediation role of resilience. BMC Nurs. (2024) 23:85–92. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-01734-1

24. Cooper AL, Brown JA, Rees CS, Leslie GD. Nurse resilience: a concept analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 29:553–75. doi: 10.1111/inm.12721

25. Huang H, Su Y, Liao L, Li R, Wang L. Perceived organizational support, self-efficacy and cognitive reappraisal on resilience in emergency nurses who sustained workplace violence: a mediation analysis. J Adv Nurs. (2024) 80:2379–91. doi: 10.1111/jan.16006

26. Liao L, Wu Q, Su Y, Li R, Wang L. Coping styles mediated the association between perceived organizational support and resilience in emergency nurses exposed to workplace violence: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Health Sci. (2025) 27:e70018. doi: 10.1111/nhs.70018

27. Chinese National Bureau of Statistics. Main data of the 7th National Population Census in 2020. (2024). Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/d7c/202303/P020230301403217959330.pdf (accessed March 12, 2024).

28. Li Z, Liu Y. Research Methods in Nursing: People's Medical Publishing House. Beijing, BJ: Basic Books. (2018).

29. Wang HQ, Wang SY, Liu DM. An empirical study on the relationship between job insecurity and work engagement towards nurses in different forms in tertiary hospital. Chin Hosp Manage. (2016) 36:74–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn221370-20210713-00243

30. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. (2007) 20:1019–28. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271

31. Wang L, Shi Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Z. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale in Chinese earthquake victims. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2010) 64:499–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02130.x

32. Tu Z, He J, Wang Z, Song M, Tian J, Wang C, et al. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale in Chinese military personnel. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1163382. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1163382

33. Cheng C, Dong D, He J, Zhong X, Yao S. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) in Chinese undergraduates and depressive patients. J Affect Disord. (2020) 261:211–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.018

34. Mobley WH, Griffeth RW, Hand HH, Meglino BM. A review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychol Bull. (1979) 86:493–522. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.3.493

35. Zi FY, Zhu XY, Meng W, Cai YC. An investigation of the relationship between compulsory citizenship behavior and turnover intention. Hu Li Xue Za Zhi. (2023) 38:69–73. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2023.22.069

36. Kavakli BD, Yildirim N. The relationship between workplace incivility and turnover intention in nurses: a cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag. (2022) 30:1235–42. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13594

37. Bruyneel A, Bouckaert N, Maertens de Noordhout C, Detollenaere J, Kohn L, Pirson M, et al. Association of burnout and intention-to-leave the profession with work environment: a nationwide cross-sectional study among Belgian intensive care nurses after two years of pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud. (2023) 137:104385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104385

38. Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Annual re psy. (2002) 53:27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231

39. Jiang L, Xu X, Wang HJ. A resources-demands approach to sources of job insecurity: a multilevel meta-analytic investigation. J Occup Health Psychol. (2021) 26:108–26. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000267

Keywords: negative workplace behavior, cross-sectional study, mediator, moderator, healthcare workers

Citation: Zou J, Yang Y, Chen L, Bi Y, Li N, Luo Q and Zhang J (2025) Effects of negative workplace behavior on job insecurity and turnover intention in healthcare workers: roles of psychological resilience. Front. Public Health 13:1493964. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1493964

Received: 10 September 2024; Accepted: 24 March 2025;

Published: 23 May 2025.

Edited by:

Biljana Filipovic, University of Applied Health Sciences, CroatiaReviewed by:

Ren Chen, Anhui Medical University, ChinaLuis Dias Martins, University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE), Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Zou, Yang, Chen, Bi, Li, Luo and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jin Zhang, MzY1MTk4NTdAcXEuY29t; Qin Luo, NTkxMzQ2NDAxQHFxLmNvbQ==

Jie Zou

Jie Zou Yanhong Yang

Yanhong Yang