- 1Family and Adolescent Clinical Technology & Science, Partnership to End Addiction, New York, NY, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX, United States

Introduction: Research, clinical wisdom, and government policy recommend family involvement in services for young adult (YA) opioid use disorder (OUD) to improve treatment outcomes. Moreover, research suggests YAs believe that family involvement is essential to OUD treatment and prefer greater involvement of their concerned significant others (CSOs), such as family members, romantic partners, and family-of-choice members in their care. Yet, CSOs are not routinely involved in OUD services for YAs. The main aim of this qualitative study is to learn from CSOs and YAs directly about their thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and experiences with family-involved services.

Method: We used convenience sampling to recruit 10 YAs (ages 24–36 years) who were in treatment for OUD and their CSOs (5 mothers, 2 grandmothers, 2 partners, 1 aunt) from two urban treatment centers. Using semi-structured interview guides, we conducted qualitative interviews with YAs and their CSOs to explore their experiences, feelings, and attitudes toward family involvement in services. Thematic content analysis started with deductive-dominant group consensus coding followed by matrix analysis to analyze themes in the context of CSO-YA dyads.

Results: We identified five main themes: (1) CSO-YA relationships were resilient and motivated treatment and recovery, (2) CSOs believed in the importance of family involvement in services and experienced personal benefits by participating, (3) CSO involvement occurred on a continuum from facilitating treatment entry to systemic family therapy, (4) YAs identified CSOs who were supportive and encouraging of treatment even in the face of CSO barriers and challenges, and (5) YAs held accurate perceptions of their CSOs' MOUD attitudes and beliefs.

Discussion: In this qualitative study we learned from YAs and CSOs themselves about the individual and relational benefits of family integration in services and replicated findings from previous research highlighting preferences for greater family involvement in OUD services. Clinical implications and recommendations for challenging barriers to relationship-oriented services and recovery planning for OUD are discussed.

Introduction

Rates of opioid use among adolescents and young adults (YAs) remain high despite the known risks associated with opioid use and national efforts to increase prevention and treatment. Among YAs, rates of past year opioid use have been found to be as high as 32%, with rates of subsequent opioid misuse around 8% (1). Moreover, lethal overdoses related to opioids among this population have increased 268% from 1999 to 2016 (2), and up to two-thirds of overdose deaths among YAs involve opioids (3).

YAs are notoriously difficult to engage in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), and they tend to have worse outcomes compared to mature adults (4). Recent studies have shown that fewer than one-third of YAs currently receive adequate treatment (5, 6). Furthermore, although medication for OUD (MOUD) is the standard of care for youth OUD (7, 8), MOUD remains vastly underutilized in this age group (9, 10). For youth who do access MOUD treatment, most struggle with adherence, retention, and premature treatment termination (9, 11, 12).

Involvement of concerned significant others (CSOs) is a key indicator of high-quality substance use services of all kinds including OUD and MOUD (13, 14). In practice, CSOs of YAs often tend to be caregivers [e.g., (15, 16)]; however, they may also be other loved ones and family-of-choice members like friends and partners. CSOs can be involved in substance use services across the treatment services continuum, from learning about services and facilitating treatment entry, to attending family groups and sessions to learn psychoeducation and new family-oriented behavioral skills (14, 17). Moreover, CSOs can be engaged in services to meet their own needs including self-care and coping with the emotional burden of caring for loved ones struggling with addiction (16, 18). Research indicates CSO involvement in substance use services is associated with greater treatment engagement (16), reduced rates of drop out (41), increased length of sobriety (19), increased MOUD adherence (20, 21), and decreased number of relapses (22). Furthermore, new research suggests YAs may actually prefer greater involvement of their CSOs in their treatment (23). Unfortunately, family and CSO involvement in OUD services is inconsistent (24, 25), a significant problem that research is only beginning to address.

Barriers to CSO involvement in services

Barriers to family and CSO involvement in services exist across ecological systems. A 2024 scoping review by Tham and Solomon (26) of barriers to family involvement in behavioral services for severe mental illness identified barriers embedded in organizational culture and structure, societal attitudes, provider training and education, and relationship dynamics among patients, their families, and providers. Little is known about the barriers to family and CSO involvement in services for YA OUD specifically, although the scant research to date suggests barriers may be similar.

Limited training opportunities for providers to learn techniques to collaborate with family members, along with lack of administrative priorities for providing family services, have plagued behavioral health services (26) and may also impact family involvement in YA OUD services. In one study, YA OUD providers reported inadequate training, education, and experience engaging and collaborating with families, as well as concerns about confidentiality (25). These barriers coincide with programmatic limitations including scarce opportunities for family members to participate in services, lack of provider time for family outreach, limited staff for family groups, and restrictions on holding counseling sessions that involve family members, as well as administrative barriers related to appointment scheduling (25).

Societal attitudes and stigma are other known barriers to family members seeking services and participating in services for their loved ones (27, 28). This is especially true for family members of individuals struggling with OUD. Family members are reluctant to pursue supportive services due to experiences of stigma and shame (29). Concurrently, stigmatized clients and patients are reluctant to invite their family members to participate in services for the same reasons (30).

Even more concerning is evidence that providers may hold negative attitudes and perceptions about family members and the efficacy of family involvement in services, curbing the extent to which they pursue opportunities to collaborate with CSOs. In one study exploring attitudes among YA OUD providers, providers reported seeing less value in collaborating with families for patients over the age of 18 related to assumptions about lower reliance on the family system among this age group (31). Another study assessing experiences of family members found that not only were family members dissatisfied with their involvement in services, but also they felt dismissed and patronized by providers (29).

Finally, poor access to care is a longstanding problem for behavioral health treatment that persists for YA OUD services. Family members experience challenges navigating the treatment system, in particular understanding the available services to support their loved one (29). The emotional toll of caring for family members struggling with OUD (32) and lack of knowledge about services available to support themselves (29) further impairs access to care for CSOs.

Current study

The extant research on family and CSO involvement in OUD services for YAs focuses on experiences reported by YA OUD providers and YA patients. There are only a handful of studies seeking the perspectives of CSOs themselves (e.g., 29). The main aim of this qualitative study is to learn from CSOs and YAs directly about their thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and experiences with family-involved services. This qualitative study has two main innovations. First, it is among the first to interview CSOs about navigating OUD services and their opinions about the role of CSOs in YA OUD services and recovery processes. Learning from stakeholders who are the target of services—in this case, family-focused interventions—is directly relevant to developing training and implementation strategies to improve intervention uptake. Second, this study is located in supporting relationship-oriented approaches and highlights the value of the social context in treatment and recovery planning for YAs. Supportive family relationships and social support are key forms of recovery capital for YAs that help to mitigate their unique developmental vulnerabilities and risk factors (6).

Method

Study design and population

We conducted qualitative interviews with YAs and their CSOs. YAs were recruited from two OUD treatment centers housed under one drug and alcohol treatment program in a large metropolitan area. Both treatment clinics offered opportunities for CSO participation in family education and support groups, check-ins with the treatment team, and family sessions when patients expressed desire to have family members involved and provided consent for counselors to contact them. All study protocols were approved by the governing IRB.

Eligibility and recruitment

We used convenience sampling to recruit 25 YAs over a 13-month period (November 2022 to December 2023). At each treatment center, an in-house research assistant identified and referred to the study team patients between the ages of 18 and 30 who were currently or previously enrolled in the center's MOUD treatment program. Patients were required to be able to speak and understand English and provide informed consent. YAs who consented to participate completed a brief demographic and opioid use history survey via Qualtrics and an in-person qualitative interview during a subsequent site visit by the research team. At the end of each interview, YAs were asked for permission to contact their CSO whose role in treatment had been discussed as part of the interview. CSOs were contacted by and interviewed over a 14-month period (December 2022 to January 2024). Twenty of the 25 YA participants gave permission to contact their CSO for a follow-up interview and provided contact information. We were unable to reach 12 CSOs using the contact information provided by the YA. Because the YA's participation in the study had ended, we did not recontact YAs for new or additional contact information for their CSO. Thirteen CSOs (65%) were reached by telephone and expressed interest in participating in the study, however 3 CSOs were subsequently unable to be reached for consent and enrollment. The 10 remaining CSOs consented to participate, completed a brief demographic and substance use and treatment history questionnaire via Qualtrics, and were interviewed via video conference. All YA and CSO interviews were conducted by the same two trained research assistants (authors SD and MW). Interviews lasted ~45 min and YAs and CSOs each received a $40 Amazon gift card voucher as compensation for interview completion.

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured interview guides were used for qualitative interviews for both YAs and CSOs (see Appendix A for CSO sample). The interview guides consisted of open-ended questions and prompts designed to lead the interviewer and participant through different topics and content areas while allowing each participant space to tell their unique story. Questions explored domains relevant to OUD services and common barriers to family involvement in behavioral services: (1) past and current treatment experiences, (2) perspectives on treatment goals including MOUD treatment, (3) attitudes and beliefs about family involvement in services and recovery planning for YA OUD, (4) family relationships and dynamics including the relationship between CSOs and YAs, and (5) barriers to family participation in services. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by the study team. All identifiers were removed prior to coding. For this study we used a random name generator of the most common names in the United States to create gendered pseudonyms for participants to conceal identifiers (e.g., race/ethnicity).

We used mixed deductive-inductive qualitative content analysis procedures (33) with team-based codebook refinement (34). The coder cohort consisted of 6 co-authors. Four identified as White, and two as Multirace. Four identified as cisgender female, one as cisgender male, and one as non-binary. Three had master's degrees and one had a doctoral degree. The lead qualitative interviewer (author SD) created deductive codebooks based on the questions asked and responses commonly collected during interviews. The study team reviewed the proposed codebooks and engaged in an iterative process to refine codes and definitions for clarity and precision before beginning to code.

Coding started with group consensus coding, whereby each member of the coding team independently coded a study transcript and participated in a live coding group to discuss codes and reach agreement. Next, we double-coded study transcripts and continued live coding groups to reach agreement. During live meetings, coders completed a detailed segment-by-segment review of the entire transcript as well as the application of codes in each segment. We continued iterative refinement of existing codes and definitions while also using inductive qualitative content analysis procedures to add new codes and definitions to the codebooks to reflect unanticipated emerging themes. After intercoder reliability was established, coding continued independently with weekly coding meetings to maintain reliability. All coding was conducted using ATLAS.ti software version 24 (35). Matrix analysis was used as a complementary strategy to synthesize and interpret coding results using a grid that listed interview participants along the x-axis and concepts along the y-axis to show which concepts emerged in each interview as well as the frequency of each concept across the study sample (36). To analyze CSO data in the context of YA data, each column represented a CSO-YA dyad rather than an individual participant. With these analytic procedures, we learned about CSO past and current experiences accessing and participating in services for their loved ones in the context of YA experiences and opinions on related topics.

Techniques to enhance coding trustworthiness and reflexivity

Coding reliability was focused on internal reliability and the quality, authenticity, and truthfulness of our findings (42). Therefore, we favored techniques to enhance coding trustworthiness rather than quantitative measures of inter-coder agreement, consistent with current recommendations (37). The coding team mitigated potential coding bias during thematic analysis to enhance trustworthiness and credibility in four main ways. First, coders received training on qualitative data analysis. Second, as described above, 20% of transcripts were coded by two or more coders to enhance reliability. Third, two members of the authorship team who were not involved in coding and thematic analysis independently reviewed all themes and supporting quotations. Finally, we followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research [SRQR; (38)].

The coding and authorship teams engaged in team-reflexive discussions to understand each person's position within the research, experiences and beliefs about the content matter, experiences and orientation toward qualitative research, and favored data analysis procedures throughout the design, execution, and reporting of this qualitative study (39).

Results

Participants

Participants were 10 YA-CSO dyads. YAs were on average 27 years old (SD = 4.1, range = 20–36; 70% age 20 to 30). Self-identified race was 50% Black or African American (n = 5), 30% White (n = 3), 20% Multirace or another race (n = 2). Twenty percent (n = 2) identified as Latino/a/x, Spanish, or Hispanic. Participants were predominantly male (60%; n = 6). CSOs were five mothers, two grandmothers, two partners, and one aunt. Self-identified race and ethnicity was 50% White (n = 5), 30% Black or African American (n = 3), and 20% Latino/a/x, Spanish, or Hispanic. Participants were predominantly female (80%; n = 8). Three CSOs (30%) reported a history of substance use disorder and of those 2 reported receiving substance use disorder treatment. Demographic data were missing for 2 CSOs.

We identified five main themes related to study aims. Each theme is described below along with exemplar statements drawn from interviews and organized in rows by dyad.

Theme 1: CSO-YA relationships are resilient and a source of strength and motivation for treatment and recovery

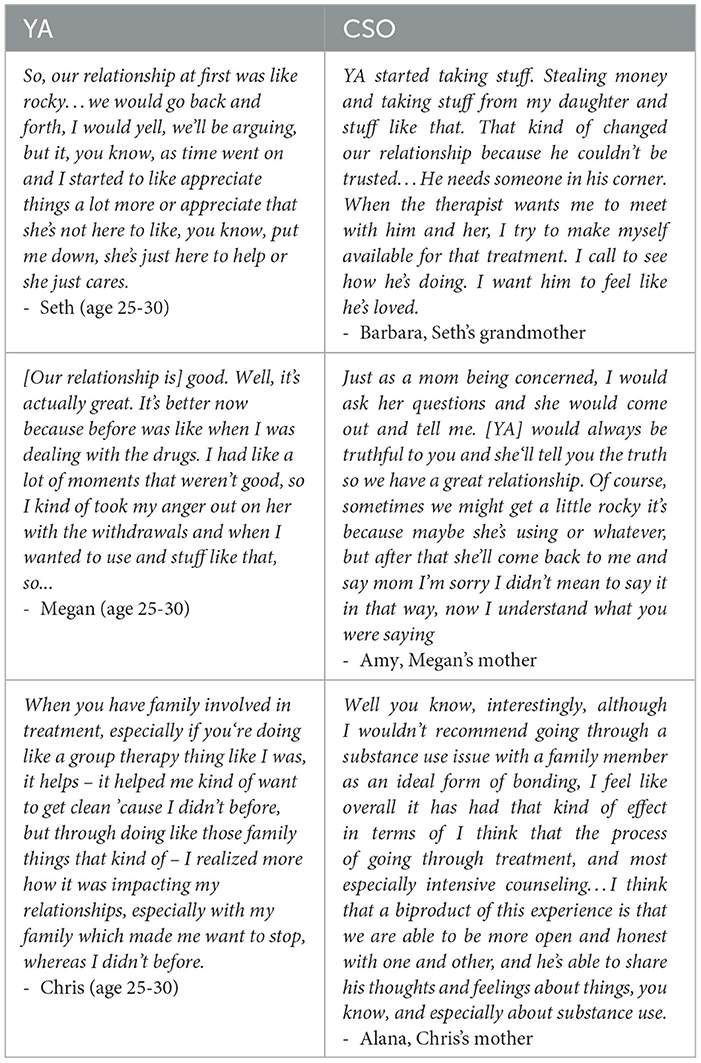

Among the 10 CSO-YA dyads, 8 dyads shared stories centered on the resiliency of their relationship, describing their connection as one that has withstood conflict and challenges associated with substance use and relapse (e.g., stealing; Seth and Barbara, fighting; Megan and Amy). Many YAs and CSOs described feeling more connected with one another having navigated and overcome difficult experiences together (Table 1).

Eight YAs described ways in which family relationships, and particularly the relationship with their CSOs, was a source of motivation for pursing abstinence and recovery goals. These YAs all had CSOs who held compassion for how difficult addiction can be and believed that supporting their loved one was crucial to their treatment and recovery (Table 2).

Theme 2: CSOs believed in the importance of family involvement in services and experienced personal benefits from participating in services for their loved one

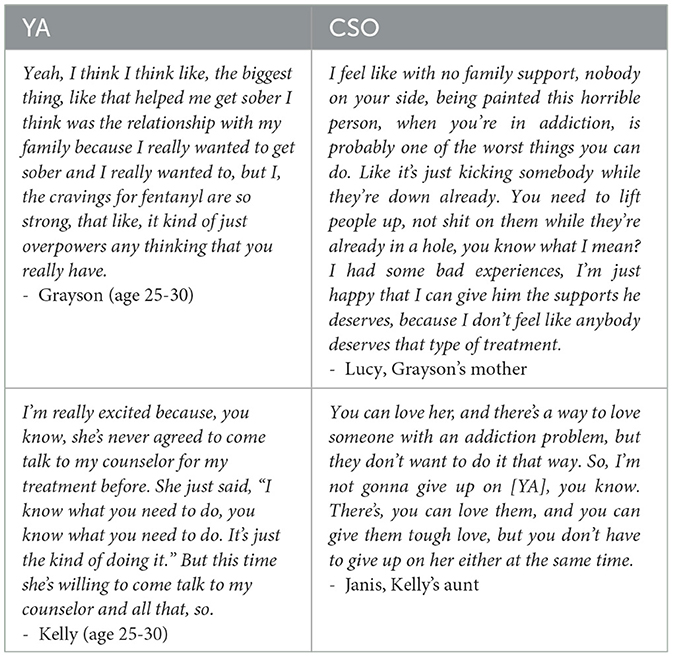

Every CSO believed family involvement in services for YAs is essential to OUD treatment. When asked, 8 out of 10 CSOs endorsed that families have a responsibility to help and support their loved one in treatment and recovery. Four CSOs elaborated on what it might be like for someone in treatment without family support, speaking to potential YA isolation and hopelessness (Table 3).

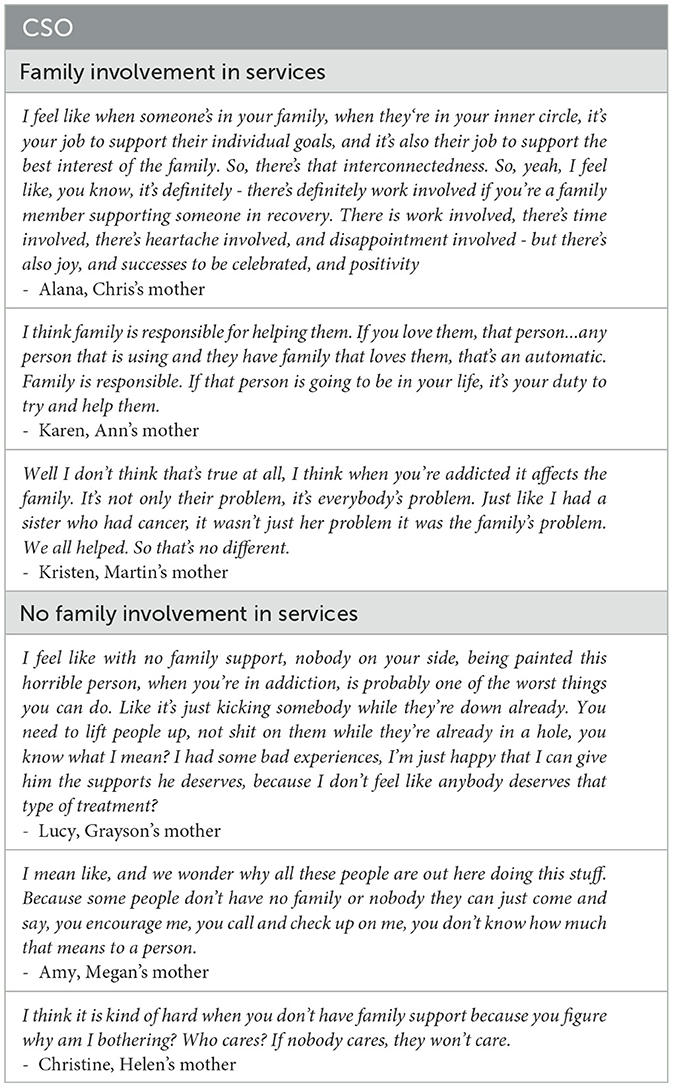

Every CSO described personal and relational benefits from participating in their loved one's services and supporting their recovery journey. CSOs shared about experiencing reassurance and relief from receiving updates on treatment progress by participating in family sessions and check-ins with the treatment team (n = 3; e.g., Barbara). Others reflected on achieving more open family communication (n = 3; e.g., Alana and Caitlin) and about personal growth like better understanding addiction, shame, and stigma (n = 3; e.g., Alana). Two CSOs disclosed their own lived experience with addiction and described the mutual benefits to their loved one's recovery and their own (e.g., Janis) (Table 4).

Theme 3: CSO involvement can occur on a continuum from facilitating treatment entry to systemic family therapy

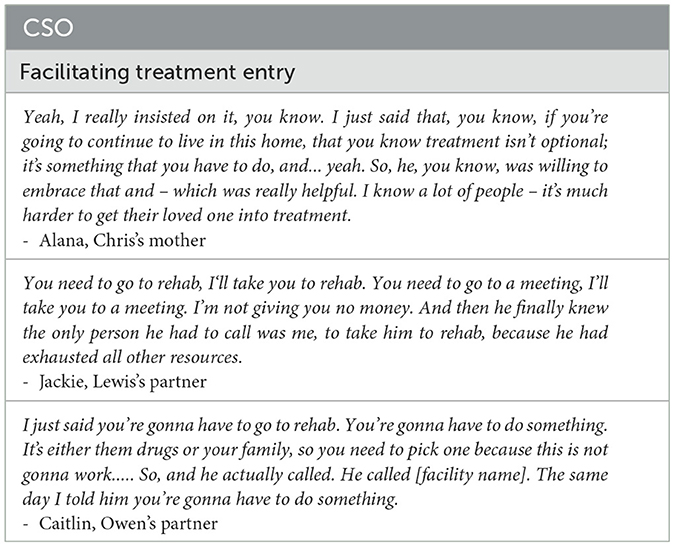

CSO involvement in services and a family approach in general can be conceptualized as a continuum of family involvement interventions with an array of complementary treatment goals (13). CSOs were involved in supporting YAs entering treatment (n = 8) and also further along the continuum (n = 9), participating in individual YA treatment sessions and also family therapy sessions. Facilitating treatment included expressing the importance, urgency, and necessity of attending treatment as well as specific facilitative actions such as bringing the YA to treatment and allowing natural consequences (e.g., withholding money from a YA not attending treatment) (Table 5).

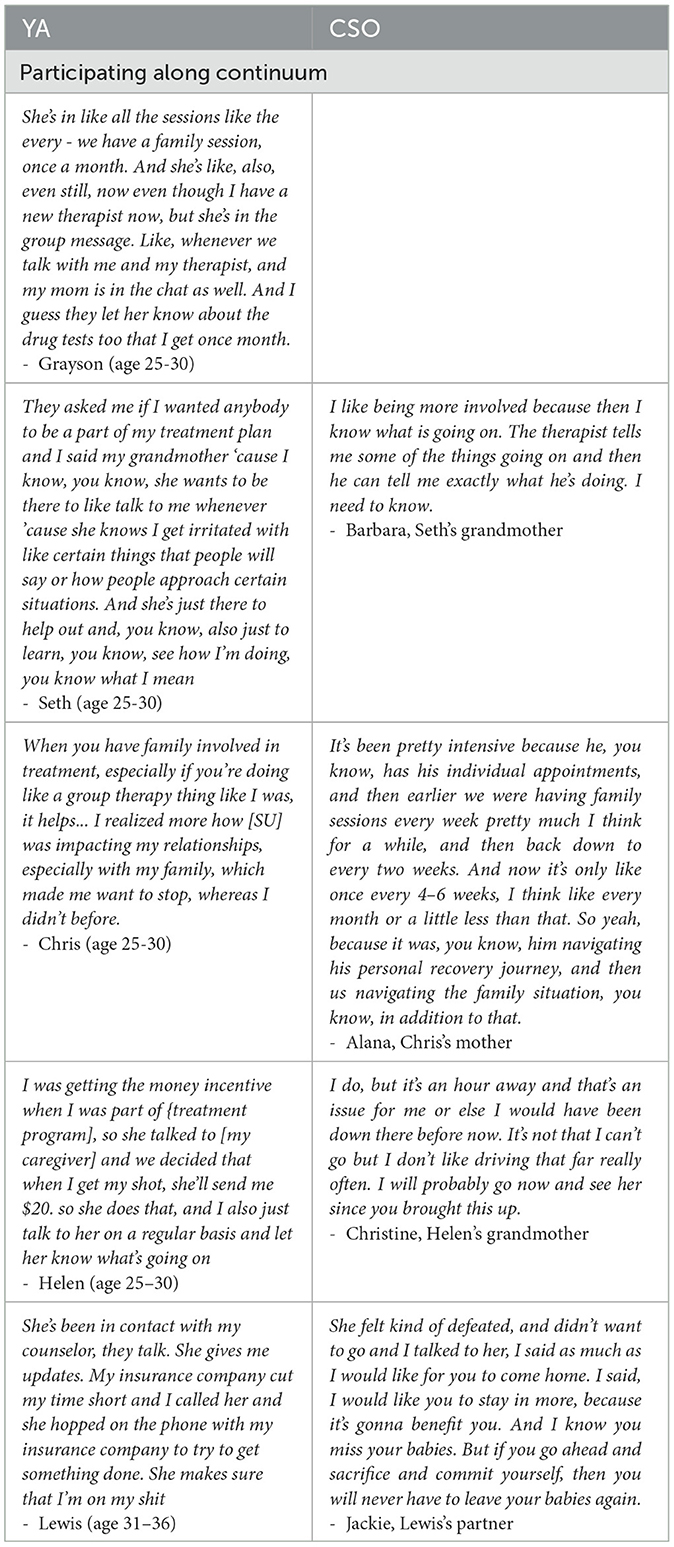

In addition to facilitating treatment, some CSOs participated with YAs in treatment. While only one dyad participated in regular (weekly) family therapy sessions in which relationship dynamics were addressed in addition to individual treatment goals, nine family members participated in the YA's treatment in meaningful ways. Importantly, YAs valued the ways that CSO participation included communication with their therapists or other treatment providers, as this open and bidirectional communication provided accountability, positive reinforcement for treatment adherence, and advocacy when encountering roadblocks. Just as CSOs played important and unique roles in facilitating YA treatment entry, ongoing CSO participation supported ongoing YA treatment attendance and treatment outcomes (Table 6).

Theme 4: YAs can identify CSOs who are supportive and encouraging of treatment and treatment goals even in the face of CSO barriers and challenges

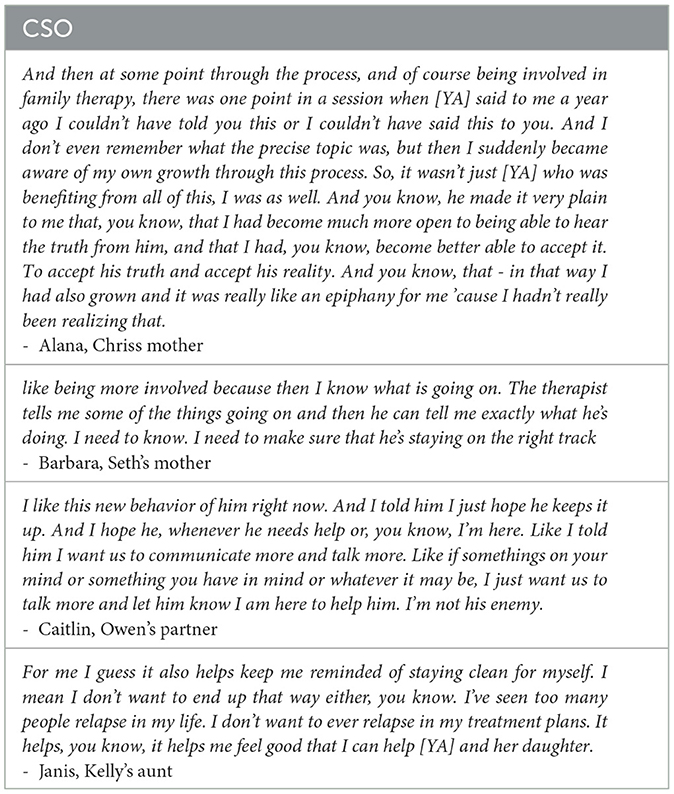

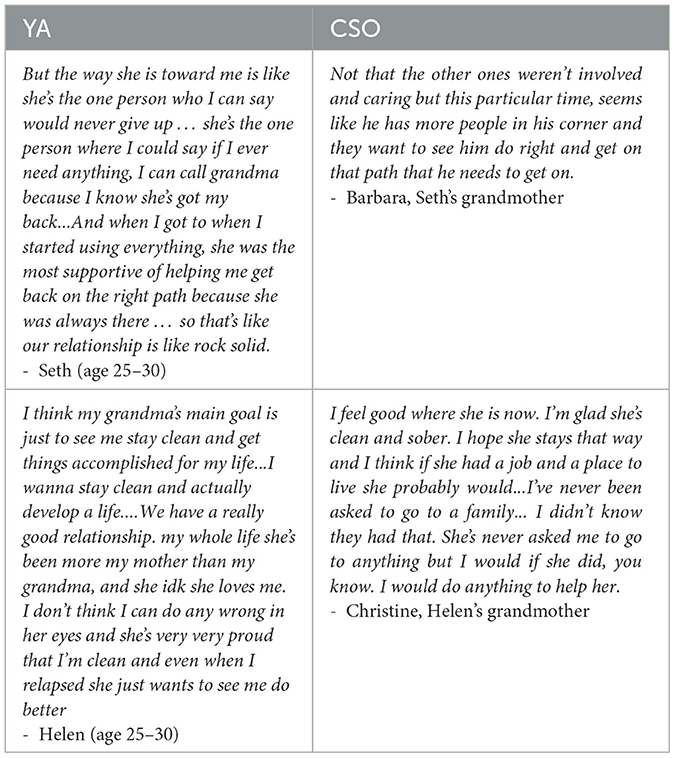

All 10 YAs reported being in alignment with their CSOs on treatment goals. Treatment goals most commonly included self-sufficiency and long-term recovery (n = 5, e.g., Helen and Christine). Other goals related to childcare and custody (n = 1), medication as treatment for OUD (n = 1), and housing stability (n = 1) (Table 7).

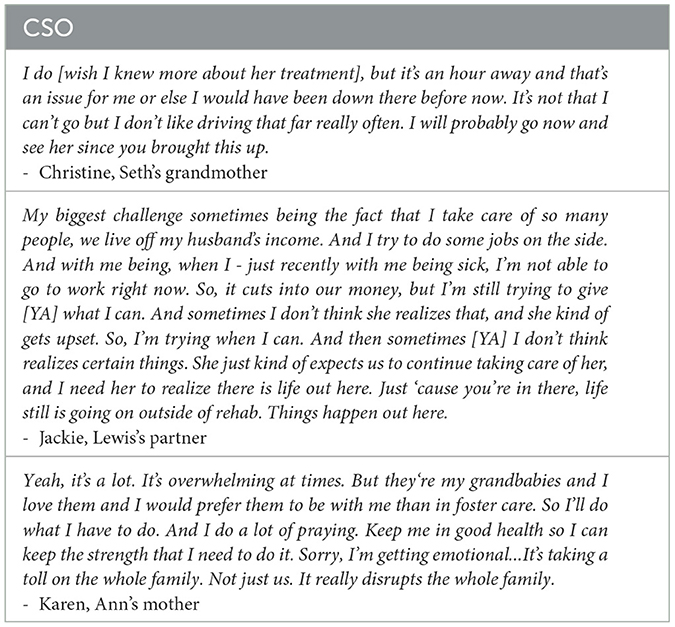

Despite all CSOs being supportive of treatment, seven mentioned significant challenges or barriers to being involved with their YA's treatment. Barriers included logistical constraints such as having a too-busy daily schedule (n = 4; e.g., Jackie), the treatment center being far away (n = 1; e.g., Christine), and their own physical health issues that made traveling for visits difficult (n = 1; e.g., Karen). CSOs also mentioned emotional challenges such as feeling burnt out in their caregiving role (n = 3; e.g., Jackie), believing that their YA was rejecting the treatment being offered (n = 1), and feeling disappointed and angry in their loved one (n = 1). One CSO mentioned their own lack of knowledge about addiction and the treatment system as a barrier to their involvement (Table 8).

Theme 5: YAs hold accurate perceptions of their CSOs' MOUD attitudes and beliefs

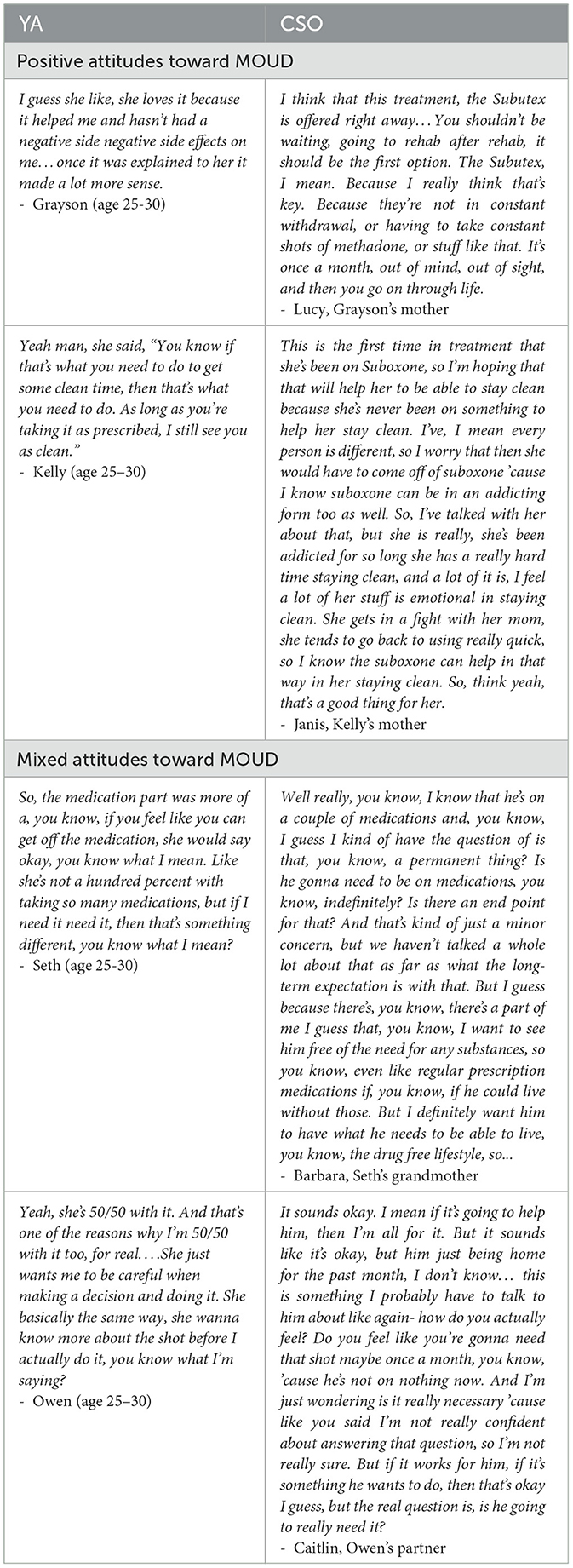

YAs understood their CSOs' feelings and opinions about MOUD treatment, which were either positive or mixed though generally positive. We previously reported on MOUD goal alignment as perceived by YAs themselves, finding that most YAs believed their CSO felt similarly about MOUD as they did (23). Here we provide evidence that YAs perceptions were accurate, even when CSOs held more complex mixed views about MOUD. Nine YAs accurately described their CSO's attitudes toward MOUD; one CSO was not asked about this. For four dyads, CSOs confirmed positive opinions about MOUD. The most cited positive benefit of MOUD by both YAs and CSOs was relieving cravings and withdrawal symptoms to facilitate reducing and stopping opioid use. The remaining five CSOs confirmed mixed feelings about MOUD. These CSOs recognized the positive benefits of MOUD in general and for their YA specifically while holding concerns and worries. YAs were able to identify CSO concerns about MOUD, which were often rooted in unknowns about long-term use, addictive properties of MOUD, and importance to recovery (Table 9).

Table 9. Exemplars for Theme 5: YAs hold accurate perceptions of their CSO's MOUD attitudes and beliefs.

Discussion

Through identifying qualitative themes, we learned lessons that can be leveraged to improve rates of CSO involvement in OUD treatment for YAs. In this sample, YAs identified CSOs who were encouraging and supportive of their treatment and treatment goals, with relationships described by both YAs and CSOs as connected and motivating. CSOs valued participating in services along the treatment services continuum from facilitating treatment entry to participating in systemic family therapy sessions. Moreover, CSOs identified family involvement in services as essential and experienced personally meaningful benefits from participating. Nonetheless, even in this sample of motivated and engaged CSOs, barriers to participating in services for their loved one persisted, consistent with barriers experienced by CSOs documented in the literature (29, 32).

It is encouraging that when providers collaborated with patients to identify CSOs to participate in treatment, and those CSOs were engaged in services, patients and CSOs alike identified positive individual and relational outcomes. This is not surprising given the vast literature on the effectiveness of family therapy and family involved treatments for substance use disorders (14, 40). YAs reported feeling more motivated for treatment and CSOs described both feeling relieved to be informed of their loved one's treatment and invested in learning about addiction and stigma to better support them. Moreover, greater connection and more open and nonjudgemental communication were identified by YAs and CSOs alike as an outcome of CSO supporting and participating in services.

Yet, our findings extend our previous research indicating there is ample room to grow in leveraging relationships to support OUD treatment engagement and retention for YAs. We previously reported on findings suggesting YAs value family involvement in services and preferred greater CSO involvement in their own OUD treatment (23). Results of the current study indicate CSOs hold similar beliefs. CSOs described family responsibility to support loved ones in treatment, yet very few were targeted by providers for interventions like family therapy or family recovery planning. This is an unfortunate trend (24) reflecting ongoing barriers to family involvement (25, 29).

The current findings may reflect provider reluctance to engage family members in services for YAs. Previous research describes hesitations among providers to collaborate with family members for YAs due to misinformed assumptions about developmental needs [e.g., (25, 31)]. Despite recruiting from treatment programs that value family involvement in services, only one dyad reported family members participating in family therapy sessions despite all 10 CSOs being invested to support their loved one. In order to increase CSO involvement in services, providers must see the benefit to CSO collaboration and possess the knowledge, skills, and confidence to use family therapy interventions.

These findings advocate for routine CSO involvement in services and recovery planning, and highlight the ongoing need for provider, patient, and family-facing resources to increase the availability and accessibility of evidence-based family interventions (25). Efforts to disseminate existing evidence-based pragmatic provider training resources designed to enhance competence and confidence in collaborating with CSOs and inviting their participation in treatment must be prioritized (e.g., https://drugfree.org/clinical-training-academy/). Furthermore, CSOs in this sample suggested the treatment services were difficult to access for a number of personal and logistical reasons. Better disseminating family-facing supports designed to provide education on navigating the treatment system and advocating for family involved care is essential (e.g., https://drugfree.org/article/navigating-the-treatment-system/).

Study strengths and limitations

The strength of this qualitative study lies foremost in the rigorous data collection and analysis procedures. With the vulnerabilities of the participant population and the sensitive nature of the interview topics in mind, interviewers were afforded flexibility to build rapport while the structure of the interview guide ensured all important topics were covered. Data collection was followed by innovative analysis procedures that blended traditional thematic content analysis with matrix analysis, allowing for analysis of key themes and the frequency with which themes and subthemes emerged across family members and dyads.

A main study limitation is possible self-selection bias influencing emerging themes. More than half of the CSOs who were contacted to participate in the current study were unreachable or declined to participate. Is it possible, if not likely, that CSOs who agreed to participate in the study were fundamentally different with respect to their level of involvement in their Yas' treatment and beliefs about the importance of family involvement in treatment.

Future directions

Future directions include developing and disseminating (1) training resources designed to enhance provider knowledge, skill, and confidence collaborating with family members and inviting their participation in treatment; and (2) family-facing resources on navigating the substance use disorder treatment system. Future research should also prioritize learning more from YA OUD providers about their attitudes, beliefs, and experiences offering services to CSOs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Solutions Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Preparation of this article was supported in part by the Family Involvement in Recovery Support and Treatment (FIRST) Research Network, which is co-funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R24DA051946; PI: Hogue) and grant number 1H79TI085588-02 from SAMHSA.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our deepest gratitude and appreciation to those who shared their stories with us.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The content and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1512529/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Hudgins JD, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Bourgeois FT. Prescription opioid use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the United States: A national survey study. PLoS Med. (2019) 16:e1002922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922

2. Gaither JR, Shabanova V, Leventhal JM. US national trends in pediatric deaths from prescription and illicit opioids, 1999-2016. JAMA Netw Open. (2018) 1:e186558–e186558. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6558

3. Scholl L. Drug opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. (2019) 67:52e1. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1

4. Fishman M, Wenzel K, Scodes J, Pavlicova M, Lee JD, Rotrosen J, et al. Young adults have worse outcomes than older adults: Secondary analysis of a medication trial for opioid use disorder. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 67:778–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.038

5. Hadland SE, Wharam JF, Schuster MA, Zhang F, Samet JH, Larochelle MR. Trends in receipt of buprenorphine and naltrexone for opioid use disorder among adolescents and young adults, 2001-2014. JAMA Pediatr. (2017) 171:747–55. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0745

6. Silverstein M, Hadland SE, Hallett E, Botticelli M. Principles of care for young adults with substance use disorders. Pediatrics. (2021) S195–203. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-023523B

7. Levy S, Ryan SA, Gonzalez PK, Patrick SW, Quigley J, Siqueira L, et al. Medication-assisted treatment of adolescents with opioid use disorders. Pediatrics. (2016) 138:3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1893

8. Volkow D, Emily B, Jones, Emily B, Einstein, Wargo EM. Prevention and treatment of opioid misuse and addiction: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 76:208–16. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3126

9. Hadland SE, Bagley SM, Rodean J, Silverstein M, Levy S, Larochelle MR, et al. Receipt of timely addiction treatment and association of early medication treatment with retention in care among youths with opioid use disorder. JAMA Pediatr. (2018) 172:1029–37. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2143

10. Nayak SM, Huhn AS, Bergeria CL, Strain EC, Dunn KE. Familial perceptions of appropriate treatment types and goals for a family member who has opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2021) 221:108649. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108649

11. Peavy KM, Banta-Green C. Understanding and supporting adolescents with an opioid use disorder. In: Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute. (2021). p. 1–8.

12. Viera A, Bromberg DJ, Whittaker S, Refsland BM, Stanojlović M, Nyhan K, et al. Adherence to and retention in medications for opioid use disorder among adolescents and young adults. Epidemiol Rev. (2020) 42:41–56. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxaa001

13. Bobek M, Hogue A, Porter N, MacLean A, Daleiden E, Cromley T, et al. Core competencies in family therapy for adolescent behavior problems: systemic stance and systemic skills. Contemp Family Therapy. (2025) 47:158–74. doi: 10.1007/s10591-024-09720-0

14. Hogue A, Schumm JA, MacLean A, Bobek M. Couple and family therapy for substance use disorders: Evidence-based update 2010–2019. J Marital Fam Ther. (2022) 48:178–203. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12546

15. Meyers RJ, Miller WR, Hill DE, Tonigan JS. Community reinforcement and family training (CRAFT): engaging unmotivated drug users in treatment. J Subst Abuse. (1998) 10:291–308. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(99)00003-6

16. Siljeholm O, Edvardsson K, Bergström M, Hammarberg A. Community Reinforcement and Family Training versus counseling for parents of treatment-refusing young adults with hazardous substance use: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. (2024) 119:915–27. doi: 10.1111/add.16429

17. Hornberger S, Smith SL. Family involvement in adolescent substance abuse treatment and recovery: What do we know? What lies ahead? Children Youth Serv Rev. (2011) 33S70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.06.016

18. Daley DC. Family and social aspects of substance use disorders and treatment. J Food Drug Analysis. (2013) 21:S73–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2013.09.038

19. Ariss T, Fairbairn CE. The effect of significant other involvement in treatment for substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2020) 88:526. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000495

20. Fishman M, Wenzel K, Vo H, Wildberger J, Burgower R. A pilot randomized controlled trial of assertive treatment including family involvement and home delivery of medication for young adults with opioid use disorder. Addiction. (2021) 116:548–57. doi: 10.1111/add.15181

21. Wenzel K, Fishman M, Wildberger J, Vo H, Burgower R. An assertive outreach intervention for treatment of opioid use disorder in young adults. Heroin Addict Related Clinical Prob. (2021) 23:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2024.02.007

22. Steinglass P. Systemic-motivational therapy for substance abuse disorders: an integrative model. J Fam Ther. (2009) 31:155–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2009.00460.x

23. Porter NP, Dunnsue S, Hammond C., MacLean A, Bobek M, Watkins M, et al. “I need as much support as I can get”: A qualitative study of young adult perspectives on family involvement in treatment for opioid use disorder. J Subst Use Addict Treatm. (2024). 167:209512. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209512

24. Bagley SM, Ventura AS, Lasser KE, Muench F. Engaging the family in the care of young adults with substance use disorders. Pediatrics. (2021) 147:S215–S219. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-023523C

25. Pielech M, Modrowski C, Yeh J, Clark MA, Marshall BD, Beaudoin FL, et al. Provider perceptions of systems-level barriers and facilitators to utilizing family-based treatment approaches in adolescent and young adult opioid use disorder treatment. Addict Sci Clin Pract. (2024) 19:20. doi: 10.1186/s13722-024-00437-x

26. Tham SS and Solomon P. Family involvement in routine services for individuals with severe mental illness: scoping review of barriers and strategies. Psychiatric Servi. (2024) 2024:e1–22. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.20230452

27. Corrigan PW, Miller FE. Shame, blame, and contamination: a review of the impact of mental illness stigma on family members. J Mental Health. (2004) 13:537–48. doi: 10.1080/09638230400017004

28. Goldberg JO, McKeag SA, Rose AL, Lumsden-Ruegg H, Flett GL. Too close for comfort: stigma by association in family members who live with relatives with mental illness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:5209. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20065209

29. Khan F, Lynn M, Porter K, Kongnetiman L, Haines-Saah R. “There's no supports for people in addiction, but there's no supports for everyone else around them as well”: a qualitative study with parents and other family members supporting youth and young adults. Can J Addict. (2022) 13:S72–82. doi: 10.1097/CXA.0000000000000149

30. Bagley SM, Schoenberger SF, Lunze K, Barron K, Hadland SE, Park TW. An exploration of young adults with opioid use disorder and how their perceptions of family members' beliefs affects medication treatment. J Addict Med. (2022) 16:689–94. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001001

31. Buchholz C, Bell LA, Adatia S, Bagley SM, Wilens TE, Nurani A, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder for youth: patient, caregiver, clinician perspectives. Journal of Adolescent Health. (2024) 74:320–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.08.047

32. Ludwig A, Monico LB, Lertch E, Schwartz RP, Fishman M, Mitchell SG. Until there's nothing left: Caregiver resource provision to youth with opioid use disorders. Substance Abuse. (2021) 42:990–7. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2021.1901178

33. Armat MR, Assarroudi A, Rad M. Inductive and deductive: Ambiguous labels in qualitative content analysis. Qualitat Report. (2018) 23:1. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2018.2872

34. MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cam J. (1998) 10:31–6. doi: 10.1177/1525822X980100020301

35. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development Gmb H. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software (version 23.2.1). ATLAS.ti (2023).

36. Averill JB, De Chesney M. Qualitative data analysis. In:Chesnay MD, , editor. Nursing Research Using Data Analysis: Qualitative Designs and Methods in Nursing. (2014). p. 1–10.

37. Halpin SN. Inter-coder agreement in qualitative coding: Considerations for its use. Am J Qualitat Res. (2024) 8:23–43. doi: 10.29333/ajqr/14887

38. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Med. (2014) 89:1245–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

39. Olmos-Vega FM, Stalmeijer RE, Varpio L, Kahlke R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Medical Teacher. (2023) 45:241–51. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

40. Hogue A, Henderson CE, Becker SJ, Knight DK. Evidence base on outpatient behavioral treatments for adolescent substance use, 2014–2017: Outcomes, treatment delivery, promising horizons. J Clini Child Adolesc Psychol. (2018) 47:499–526. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1466307

41. Al Ghafri H, Hasan N, Elarabi HF, Radwan D, Shawky M, Al Mamari S, et al. The impact of family engagement in opioid assisted treatment: results from a randomised controlled trial. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2022) 68:166–70. doi: 10.1177/0020764020979026

Keywords: young adult, concerned significant other, family, opioid use disorder, family involvement

Citation: Porter NP, Dunnsue S, Hammond C, Bobek M, MacLean A, Watkins M, Henderson CE and Hogue A (2025) Lessons learned from concerned significant others: a qualitative analysis on involvement in services for young adult opioid use disorder. Front. Public Health 13:1512529. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1512529

Received: 16 October 2024; Accepted: 26 June 2025;

Published: 17 July 2025.

Edited by:

Mark Gold, Washington University in St. Louis, United StatesReviewed by:

Kishan Kariippanon, The University of Sydney, AustraliaPV AshaRani, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

Copyright © 2025 Porter, Dunnsue, Hammond, Bobek, MacLean, Watkins, Henderson and Hogue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicole P. Porter, bnBvcnRlckB0b2VuZGFkZGljdGlvbi5vcmc=

Nicole P. Porter

Nicole P. Porter Sean Dunnsue1

Sean Dunnsue1 Craig E. Henderson

Craig E. Henderson