- 1The W. Maurice Young Centre for Applied Ethics, School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 2European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO European Centre for Health Policy, Brussels, Belgium

- 3Special Programme on Primary Health Care, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

- 4Department of Health Financing and Economics, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

- 5Takemi Program in International Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, Boston, MA, United States

- 6Department of Global Health and Primary Care, Bergen Centre for Ethics and Priority Setting, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

Background: Calls for investing in essential public health functions (EPHFs) and common goods for health (CGH) are numerous, but it is often unclear to policymakers how such investments lead to health system improvements.

Objectives: To showcase plausible pathways between actions taken to improve specific health system functions—in other words, investments in EPHFs and CGH—and their impact on health system performance, the health systems performance assessment framework for Universal Health Coverage is used. We draw on three examples—community engagement and social participation, taxes and subsidies, and public health surveillance and monitoring—to demonstrate how action in these areas can improve health systems.

Conclusions: This conceptual mapping also points to the crucial role of good governance and demonstrates how investing in multiple EPHFs and CGH can trigger a chain reaction to spur broader health system improvement.

Introduction

Calls for governments to invest in essential public health functions (EPHFs) and common goods for health (CGH) are numerous (1–8), yet investments are often lacking. It is often unclear to policymakers how investments in EPHFs and CGH can lead to health system improvements ex-ante (9, 10). Thus, this article sketches plausible pathways to demonstrate how investing in EPHFs and CGH can improve health system performance. Our narrative elucidates the chain of events linking investments in EPHFs and CGHs to improvements in health system performance through “pathways”.

EPHFs and CGH have a similar list of key interventions and functions needed for resilient, primary health care (PHC)-focused health systems—meaning systems that empower people and communities, foster multi-sectoral policy and action, and ensure integrated service delivery. Yet, they arise from different underlying theoretical arguments. CGH are population-level, collective action areas required for public health and use economic theory about market and government failures around public goods to make the case for investment in these areas. An overview of CGH categories is provided in Box 1 and the original source for a comprehensive list can be found in (11). CGH include surveillance, legislative and regulatory systems, and environmental protection measures, across sub-national, national, and international levels (11). EPHFs are normative and include a set of fundamental, interlinked, and interdependent activities within and beyond the health sector to advance public health objectives. The list of EPHFs is provided in Box 2 of this article, but for explanatory details please see (12). EPHFs include actions relevant to national, sub-national, and local levels and those that contribute to large-scale efforts to establish CGH (12–14). For example, monitoring and surveillance activities include both individual-level detection and reporting as well as population-level synthesis and are aggregated at the global level.

Box 1 Categories of CGH.

1. Policy and coordination (e.g., disease control policies and strategies).

2. Regulations and legislation (e.g., environmental regulations and guidelines).

3. Taxes and subsidies (e.g., taxes on products with impacts on health to create market signals leading to behavior change).

4. Information collection, analysis, and communication (e.g., surveillance systems).

5. Population services (e.g., medical and solid waste management).

Drawn from (11).

Box 2 List of EPHFs.

1. Public health surveillance and monitoring.

2. Public health emergency management.

3. Public health stewardship.

4. Multisectoral planning, financing, and management for public health.

5. Health protection.

6. Disease prevention and early detection.

7. Health promotion.

8. Community engagement and social participation.

9. Public health workforce development.

10. Health service quality and equity.

11. Public health research, evaluation, and knowledge.

12. Access to and utilization of health products, supplies, equipment, and technologies.

Drawn from (13).

To showcase plausible pathways between actions taken in specific EPHFs and CGH to improve health system performance, the health systems performance assessment (HSPA) framework for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is used. The HSPA framework not only provides a conceptual basis to orient analyses of health system data, but it also links inputs made within health system “functions” to broader health system goals (15). It is conceptual in nature and not intended to guarantee definitive outcomes, given that policy contexts will inevitably vary.

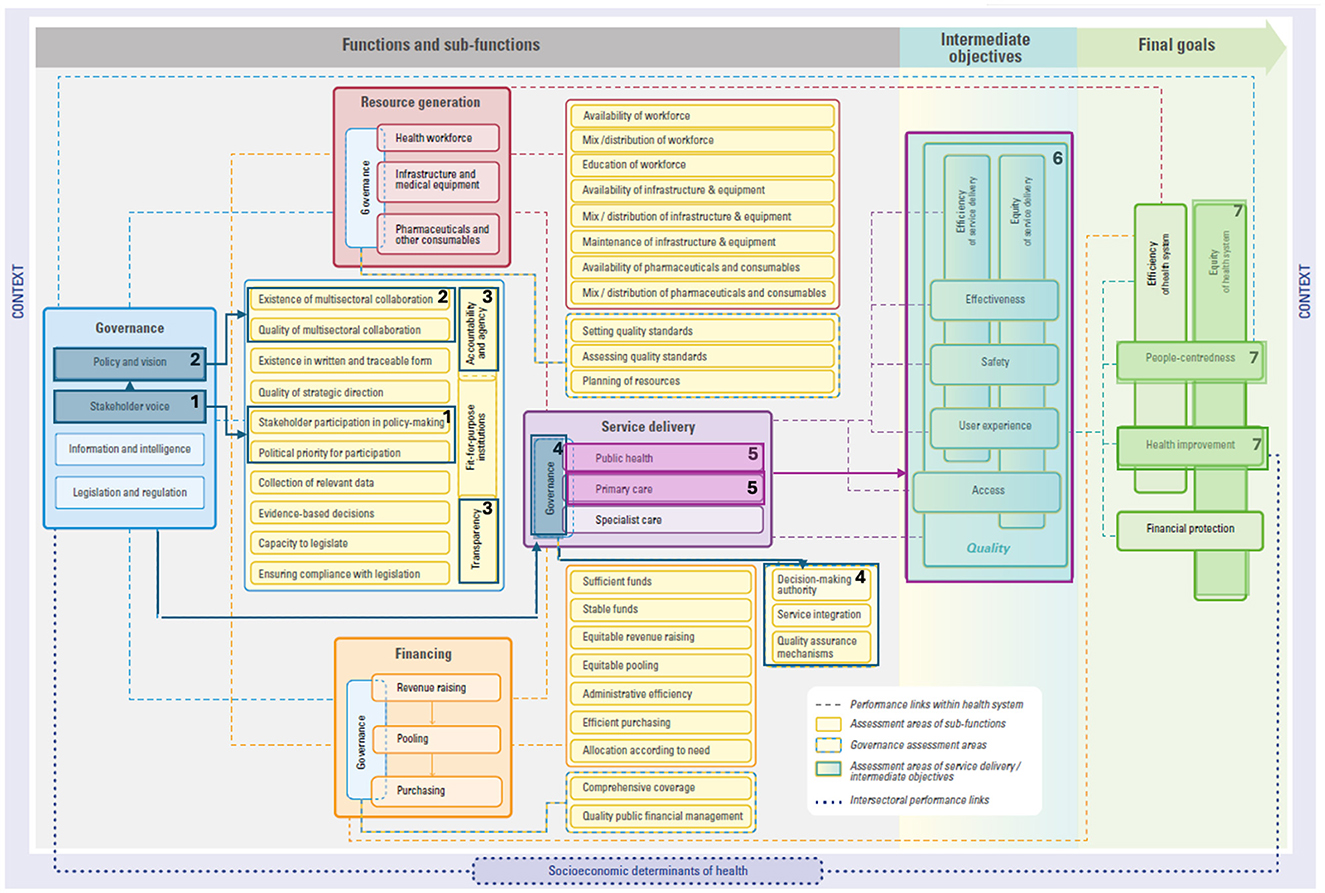

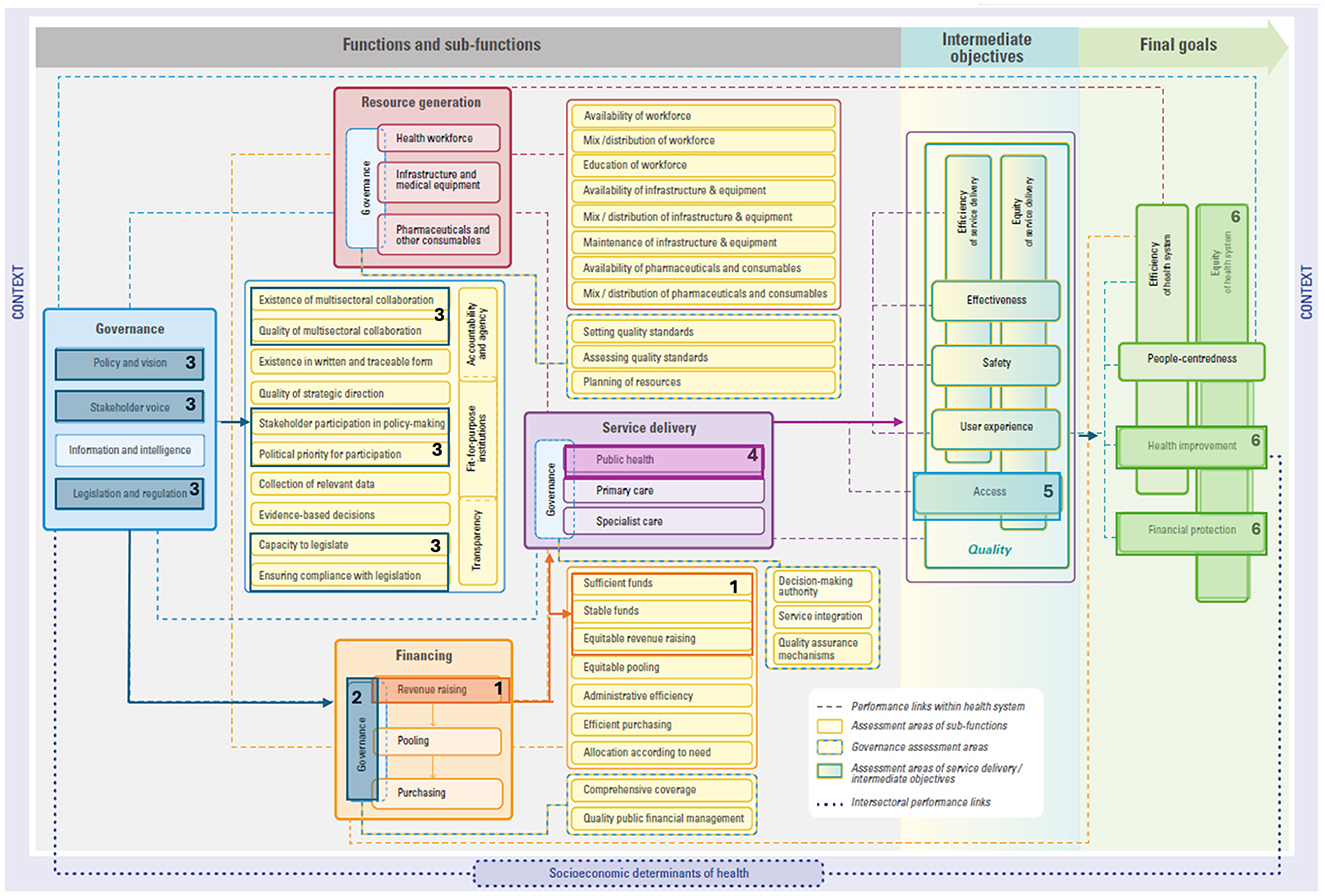

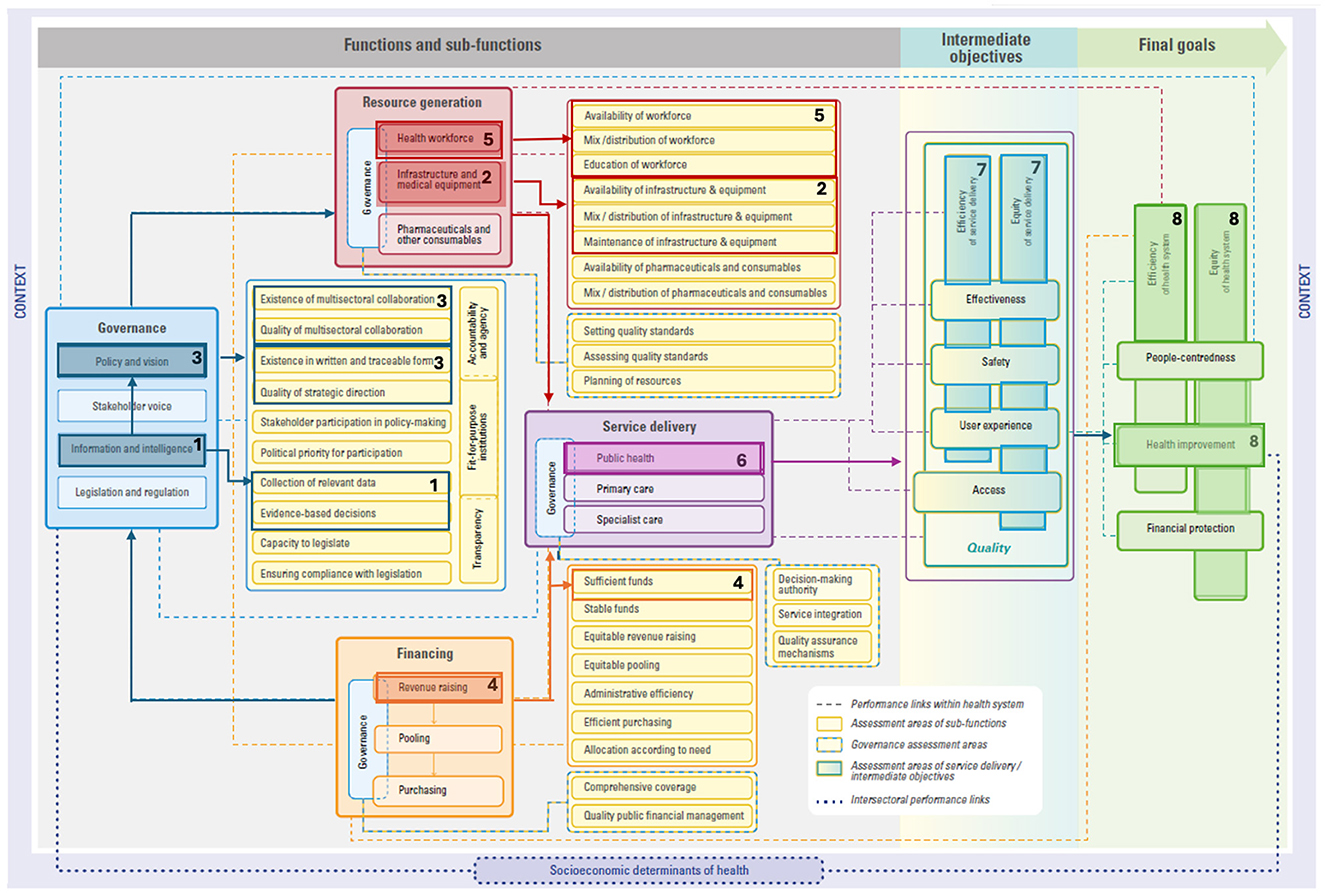

We draw on three examples embedded within both EPHF and CGH frameworks to demonstrate how investing in these areas impacts health system performance, per the HSPA framework. These examples are: (i) community engagement and social participation, (ii) taxes and subsidies, and (iii) public health surveillance and monitoring. These described links are all drawn in each respective figure to guide understandings (Figures 1–3) and details on the mechanics of the HSPA framework are provided in Box 3.

Figure 1. Linking community engagement and social participation to the HSPA framework. Please see (15) for the original figure.

Box 3 Mechanics of the HSPA framework.

Within the HSPA framework, possible links between functions, sub-functions, and assessment areas are drawn with a dotted line.

Functions are the foundations of a health system. These functions are governance, resource generation, financing, and service delivery. Each of these functions are illustrated in the example figures (Figures 1–3), whereby governance is in a blue box, resource generation is in a red box, financing is in an orange box, and service delivery is in a purple box.

Sub-functions are specific actions or necessary elements that are conducive to achieving the function's objectives. In other words, sub-functions are key pieces or processes that are needed for each function. For example, within the governance function, there are four sub-functions (policy and vision, stakeholder voice, information and intelligence, and legislation and regulation). Evidently, each of these pieces are needed for ‘good' governance.

Assessment areas are areas that allow for examining the performance of the sub-functions. In other words, assessment areas provide the opportunity to determine how well sub-functions are performing. For example, in the case of the policy and vision sub-function of governance, assessment areas include the existence of documents in written and traceable form, quality of strategic direction, and existence and quality of multisectoral collaboration.

This conceptual mapping can be used to advance policymaker understandings of the potential pathways between EPHFs and CGH and improved health system performance. Improved understandings can help with political prioritization of and investments in EPHFs and CGH. To the best of our knowledge, this article is the first of its kind to draw conceptual links between EPHFs and CGH and health systems outcomes using the HSPA framework.

Example 1: community engagement and social participation

In this example, we begin with community engagement and social participation. We demonstrate that by making governance processes more participatory and inclusive, public health and primary care can be improved to reach the health system goals of equity and people-centeredness, as well as improving population health.

Our first pathway example focuses on community engagement and social participation (12, 16). This refers to strengthening meaningful engagement with people, communities, and civil society in strategic decision-making and service delivery (see Box 4). We start from the governance function within the HSPA framework to illustrate how investing in and prioritizing community engagement and social participation can improve health system performance, as shown in Figure 1.

Box 4 Community engagement and social participation.

Community engagement and social participation refers to strengthening community engagement, participation, and social mobilization for health and wellbeing (12). More specifically, social participation includes amplifying people's voices in public policy decision-making processes, whereas community engagement narrows in on service delivery and program design (e.g., health promotion and health literacy campaigns).

The meaningful engagement of people, communities, and civil society in decision-making processes that affect their health and wellbeing is a key sub-function of governance and labeled as stakeholder voice in the HSPA framework. Investing in community engagement and social participation means investing in the stakeholder voice sub-function of health system governance.

Although there is no single definition of “good governance” (17, 18), almost all governance frameworks include stakeholder participation and voice in policy development and implementation as a prominent, integral element (19–21). Ensuring an inclusive culture of participation starts with making participation a political priority (see #1 in Figure 1). This means not only planning for adequate resources to be devoted to social participation, but also building government capacity to design spaces for participants, particularly those with unheard voices and less power to influence debates and policy-making (stakeholder participation in policy-making) (22) (see #1 in Figure 1). Consequently, the stakeholder voice sub-function is closely linked to policy and vision (see #2 in Figure 1), to ensure policies, strategies, and plans are more responsive to population needs.

Governance that purposefully seeks to be responsive to people's needs and expectations is at the heart of accountability; linked to this is respecting and increasing people's agency for their own health (18). Accountability here refers to government accountability to the public who will be affected by policy decisions (19). A well-designed participatory process also emphasizes transparency in objectives, roles and mandates, and selection criteria for participants (see #3 in Figure 1). An example of this pathway segment is seen in the Tunisian Societal Dialogue for Health. The Societal Dialogue is a civil society-initiated and government-supported partnership that organized a series of large consultative meetings (23). These meetings engaged the government, civil society organizations, and citizens to not only co-design the first post-2011 revolution national health policy, but also empower individuals and communities (23, 24). Despite challenges linked to fluctuating political commitment toward participation, the Societal Dialogue has increased trust among actors and improved policy formulation by taking diverse population needs and views into account (24).

Strong governance requires the inclusion of stakeholder voices and clear policy and vision, which drives excellence across the health system. In other words, collating population views, demands, and needs to guide policies, strategies, and plans is a core aspect of better governance. Better governance has repercussions across other functions, namely financing, resource generation, and service delivery.

“Good” governance, one of the functions within the HSPA framework, enables the service delivery function of health systems performance. The need for good governance is demonstrated by the emphasis placed on community empowerment within the PHC paradigm (25). By strengthening community engagement initiatives, governance of service delivery is enhanced. For example, in Brazil, community representation in local health councils influences service integration and/or quality standards (see #4 in Figure 1) (26). The presence of a strong community voice will positively influence public health and primary care sub-functions of service delivery (see #5 in Figure 1)—both encompassed in the PHC approach (27).

Service delivery is assessed through indicators of access and quality of care (28). Studies demonstrate that the quality of care dimensions of effectiveness (29, 30), safety (28), and user experience (31–35) improve when PHC is implemented as per the principles laid out in the Astana Declaration (36), where a commitment to empowering individuals and communities is outlined (37). Additionally, many of the strategies applied to improve quality of care also aim to improve equity and efficiency. For example, efficiency may be improved through the early management of health problems (i.e., avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations), appropriate prescribing practices, and enhanced care coordination (28) (see #6 in Figure 1).

Ultimately, providing care that is effective, safe, and satisfies users (i.e., high-quality care) leads to various health improvements, such as reduced morbidity and mortality (28), and satisfying users can improve people-centeredness. And in fact, community-oriented primary health care has been found to substantially positively impact the health of underserved populations (28, 38, 39), entailing improvements in equity (see #7 in Figure 1).

Example 2: taxes and subsidies

In this second example, we begin with taxes and subsidies. We demonstrate how taxes and subsidies can positively impact the health system goals of health improvement, equity, and financial protection by strengthening the revenue raising sub-function of financing and the public health sub-function of service delivery.

Taxes and subsidies influence individual behavior (40) and can shape markets through the provision of positive and negative financial incentives (41). For these population-level fiscal instruments to work effectively, mechanisms to collect, pool, and distribute revenue are needed, which are generally within the purview of national governments (42).

As an illustrative example, the Government of Thailand introduced alcohol and tobacco excise taxes. By introducing these excise taxes, the revenue raising sub-function of financing is enhanced (see #1 in Figure 2), contributing to sufficient and stable funds as part of overall government spending devoted to health.

Figure 2. Linking taxes and subsidies to the HSPA framework. Please see (15) for the original figure.

For these fiscal instruments to work effectively, governance of health financing arrangements must be established, including public financial management (see #2 in Figure 2). Additionally, making decisions regarding the introduction of health taxes requires a strong governance function throughout the process, particularly in areas related to policy and vision, multisectoral collaboration between ministries of health and finance alongside other stakeholders, as well as legislation and regulation (see #3 in Figure 2).

Excise taxes can also create market signals for health promotion (43)—a core aspect of the public health sub-function of service delivery (see #4 in Figure 2). In Thailand, the excise tax was used to create ThaiHealth, a health promotion agency with a broad mandate. ThaiHealth's activities encompass addressing noncommunicable diseases, health protection, disease prevention, and early detection (44, 45).

The funds raised through these taxes are part of overall tax revenues that form the basis of public financing for UHC. These funds can lead to more and better-quality public health services which improves access, an intermediate HSPA framework objective (see #5 in Figure 2), and financial protection, a HSPA framework final goal (see #7 in Figure 2). In other words, improving access to quality health services based on need and not ability to pay, which is a core tenant of UHC. As stressed in the World Health Report 2010, public spending is needed to effectively expand coverage and move toward UHC (46). This requires an adequate tax base, which can come from a range of instruments, including health taxes and subsidies. Ultimately, by improving financial protection, we can expect improvements to health given that user fees largely deter health system use (47), which is another HSPA framework final goal (see #6 in Figure 2). Additionally, equity in the health system may be improved given that most health financing mechanisms have an equity aspect (48), which is an overarching HSPA framework final goal (see #6 in Figure 2). Similarly, a greater influx of taxes and subsidies can support more equitable health financing by improving financial protection against the risk of ill health [i.e., ensuring access to services without financial hardship (49)]. This is especially important given that the COVID-19 pandemic has afforded recognition of the problem of heightened inequity (50) and resulted in those paying out of pocket being more likely to experience worsened financial hardship (51).

Levying health taxes and ensuring equitable health financing moves a health system closer to not only the system goal of equity—recognizing that many approaches to health equity exist (52–55)—but also financial protection. In the case of ThaiHealth that targets noncommunicable diseases, there are ties to financial protection, as socioeconomic differences are linked to differing outcomes (56).

Example 3: public health surveillance and monitoring

In this final example, we delve into the links between public health surveillance and monitoring and the health systems goals of access and health improvement. In drawing this link, we explain how public health surveillance and monitoring, such as through investing in data governance, infrastructure, and interoperable digital platforms, is crucial for both governance and resource generation.

Investing in public health surveillance and monitoring involves strengthening capacities of health authorities to collect, research, analyze, monitor, and evaluate data on a regular basis and understand how to use that evidence to undertake informed decisions (57). Prioritizing this area requires investing in data governance, represented in the information and intelligence sub-function of the health system governance function (see #1 in Figure 3). Further, investing in public health surveillance and monitoring also requires data infrastructure to support interoperability of digital platforms. Infrastructure needs to be supported at the community level (e.g., within primary care) to the national level. Such efforts are represented in the infrastructure and equipment sub-function of resource generation (see #2 in Figure 3).

Figure 3. Linking public health surveillance and monitoring to the HSPA framework. Please see (15) for the original figure.

A strong information and intelligence sub-function is closely linked with the policy and vision sub-function (see #3 in Figure 3). Evidently, timely and disaggregated data on population health status, risk, protective and promotive factors, threats to health and health system performance, and service utilization can guide policymakers to understand causes of poor health, track progress, and adjust decision-making and implementation strategies (58, 59). Further, disease surveillance and response requires strong leadership and strategic direction to address gaps (e.g., cold chain challenges) and ensure an effective response. The importance of governance is particularly clear when considering that epidemics can proliferate in the absence of sufficient responses, as was the case for the Ebola virus disease outbreak in western Africa in 2014 when it was declared a public health emergency of international concern (60). However, since then, numerous actions have been taken around public health surveillance and monitoring. In the case of Liberia, although the integrated disease surveillance and response strategy was adopted in 2004, it did not allow for an effective response to the Ebola epidemic from 2014 to 2016 due to not securing resources and an abundance of vertical programs (61). Ultimately, after Liberia actively implemented the strategy in 2015 (62), this led to successes and lessons learned around the importance of strong governance, namely around multisectoral collaboration (see #3 in Figure 3), partnership, local ownership, and promoting the PHC approach (63). Moreover, disease surveillance and monitoring also requires the development and implementation of coordination platforms and systems, as well as sectoral and sub-sectoral policies and strategies.

Disease surveillance and monitoring requires adequate resources to support continued efforts and the implementation of response measures. In fact, non-sustainable financial resources was identified across 33 studies as a main issue in implementing the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response System, an approach that uses one system to collect data about multiple diseases or behaviors (64). Funds need to be allocated for collecting, analyzing, and disseminating data (65). Additionally, disease surveillance and monitoring requires enough trained and competent health workers to carry out the necessary activities, as inadequately trained staff and staff turnover can pose a challenge for disease surveillance (64). Evidently, these activities are linked to financing (e.g., revenue raising, see #4 in Figure 3) and resource generation (e.g., health workforce, see #5 in Figure 3). Ultimately, undertaking public health surveillance and monitoring requires governance, financing, resource generation, and service delivery, particularly in public health (see #6 in Figure 3). Through a more targeted public health surveillance approach, outreach activities can improve equity by better reaching at risk populations while generating efficiency gains to avoid disease spread (see #7 in Figure 3). Thus, improving equity, efficiency, and health within the health system (see #8 in Figure 3). An example of this pathway is demonstrated in Lesotho. When handling the COVID-19 pandemic, rising comorbidities and excess mortality was observed as resulting from both communicable and noncommunicable diseases (66). The government was able to use this data to make the evidence-based decision to scale-up interventions to better target susceptible populations and improve health security (66).

Conclusion

Drawing a direct pathway from one action taken to a final health system objective is difficult. However, via three examples—community engagement and social participation, taxes and subsidies, and public health surveillance and monitoring—we demonstrate how actions in these areas can improve health system performance. By exploring these links, the chain of events to improved health system performance is traced. Our intention is not to provide a prescriptive formula for bringing about particular changes but rather to offer a conceptual mapping that visualizes connections between actions taken and broader impacts on health system goals. Future analyses can also explore drawing conceptual links across additional frameworks or concepts employed by other major institutions (e.g., the European Commission, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the World Bank). Additionally, future investigations can measure how specific precursors influence outputs and outcomes, including potential unintended consequences and how they can be mitigated.

Notably, this conceptual mapping also points to the crucial nature of “good governance” which appeared in all three examples. Per the World Bank, good governance “is synonymous with sound development management” (67). Although there is no single definition, different sources outline various key principles. One set of principles include openness, participation, accountability, effectiveness, and coherence (68). Another identifies strategic vision, participation and consensus orientation, rule of law, transparency, responsiveness, equity and inclusiveness, effectiveness and efficiency, and ethics (69). And another, equity, participation, organizational arrangements, accountability, integrity, and transparency (70). Good governance is particularly essential due to the very nature of EPHFs and CGH, as both involve addressing collective action failures among health and non-health stakeholders. Governance anchored in inclusive decision-making with strong coordination across stakeholders is key and can improve financing, resource generation, and service delivery functions to lead to various performance objectives. In fact, participation is thought to be a necessary condition for the other four principles in the first set of good governance principles mentioned above (71).

Although we assessed how specific actions impact health system performance, it is not enough to act in only one area. Investing in multiple EPHFs and CGH can trigger a chain reaction to bring about broader system change. To achieve health system goals, various EPHFs and CGH should be invested in, strengthened, and politically prioritized. Policymakers can not only use our conceptual mapping to improve understandings of interlinkages between frameworks, but to negotiate for increased investments.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DR: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AE: Writing – review & editing. SPS: Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing. JB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the World Health Organization, with funding from the Government of Canada, which enabled this work.

Acknowledgments

MA would like to acknowledge the donors to the Mary and Maurice Young Professorship in Applied Ethics.

Conflict of interest

MA reports short-term instances of consulting for the World Health Organization and membership with the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Knowledge Translation and Health Technology Assessment in Health Equity. DR, KK, AE, SPS, and SS are employed by the World Health Organization. YZ is consulting with the World Health Organization. JB reports short-term instances of consulting for the World Health Organization.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

Some of the authors are staff members of the World Health Organization. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the World Health Organization.

References

1. Yazbeck AS, Soucat A. When both markets and governments fail health. Health syst. (2019) 5:268–79. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1660756

2. Lo S, Gaudin S, Corvalan C, Earle AJ, Hanssen O, Prüss-Ustun A, et al. The case for public financing of environmental common goods for health. Health syst. (2019) 5:366–81. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1669948

3. Gómez-Dantés O, Frenk J. Financing common goods: the mexican system for social protection in health agenda. Health syst. (2019) 5:382–6. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1648736

4. Earle AJ, Sparkes SP. Financing common goods for health in liberia post-ebola: interview with honorable Cllr. Tolbert Nyenswah Health syst. (2019) 5:387–90. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1649949

5. Shah A, Sapatnekar S, Kaur H, Roy S. Financing common goods for health: a public administration perspective from India. Health syst. (2019) 5:391–6. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1652461

6. Abeykoon P. Financing common goods for health: Sri Lanka. Health syst. (2019) 5:397–401. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1655358

7. Mataria A, Brennan R, Rashidian A, Hutin Y, Hammerich A, El-Adawy M, et al. 'Health for all by all' during a pandemic: 'protect everyone' and 'keep the promise' of universal health coverage in the Eastern Mediterranean region. East Mediterr Health J. (2020) 26:1436–9. doi: 10.26719/2020.26.12.1436

8. Soucat A. Financing common goods for health: fundamental for health, the foundation for UHC. Health syst. (2019) 5:263–7. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1671125

9. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, European European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Rechel B, Jakubowski E, McKee M., et al. Organization and Financing of Public Health Services in Europe. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe (2018).

10. Regional Committee for the Western Policies. Transitioning to Integrated Financing of Priority Public Health Services (Resolution). Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific (2017).

11. World Health Organization. Financing Common Goods for Health (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034204 (accessed November 8, 2024).

12. World Health Organization. 21st Century Health Challenges: Can the Essential Public Health Functions Make a Difference? Discussion Paper 2021. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/351510 (accessed November 8, 2024).

13. World Health Organization. Application of the Essential Public Health Functions: an Integrated and Comprehensive Approach to Public Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2023).

14. Neil S, Richard G, Olaa M-A, Bjorn Gunnar I, Anders T, Angela F, et al. Essential public health functions: the key to resilient health systems. BMJ Global Health. (2023) 8:e013136. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013136

15. Papanicolas I, Rajan D, Karanikolos M, Soucat A, Figueras J, editors. Health system performance assessment: a framework for policy analysis. Health Policy Series, No. 57. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

16. The Essential Public Health Functions in the Americas: A Renewal for the 21st Century. Conceptual Framework and Description. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization (2020).

17. Pomeranz EF, Stedman RC. Measuring good governance: piloting an instrument for evaluating good governance principles. J Environm Policy Plann. (2020) 22:428–40. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2020.1753181

18. van Doeveren V. Rethinking good governance. Public Integrity. (2011) 13:301–18. doi: 10.2753/PIN1099-9922130401

19. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. What is Good Governance? (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/good-governance.pdf (accessed February 10, 2025).

20. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. About Good Governance (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/good-governance/about-good-governance

21. Barbazza E, Tello JE, A. review of health governance: definitions, dimensions and tools to govern. Health Policy. (2014) 116:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.01.007

22. World Health Organization. Voice, Agency, Empowerment - Handbook on Social Participation for Universal Health Coverage. (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027794 (accessed November 8, 2024).

23. Ben Mesmia H, Rajan D, Bouhafa Chtioui R, Koch K, Jaouadi I, Aboutaleb H, et al. The Tunisian experience of participatory health governance: the Societal Dialogue for Health (a qualitative study). Health Res Policy Syst. (2023) 21:84. doi: 10.1186/s12961-023-00996-6

24. World Health Organization. Tunisia Citizens and Civil Society Engage in Health Policy. (n.d.). Available online at: https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/tunisia/stories_from_the_field_issue1_tunisia.pdf (accessed November 8, 2024).

25. Kraef C, Kallestrup P. After the Astana declaration: is comprehensive primary health care set for success this time? BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e001871. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001871

26. Coelho V. What did we learn about citizen involvement in the health policy process: lessons from Brazil. J Public Deliberat. (2013) 9:1. doi: 10.16997/jdd.161

27. Rajan D, Koch, K., Rohrer, K., Soucat, A. Governance. In:Papanicolas I, Rajan D, Karanikolos M, Soucat A, Figueras J, , editors. Health System Performance Assessment: A Framework for Policy Analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022). p. 43–77.

28. Dheepa Rajan KR, Winkelmann J, Kringos D, Jakab M, Khalid F. Implementing the Primary Health Care Approach: a Primer. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2023).

29. Gulliford M, Figueroa-Munoz J, Morgan M, Hughes D, Gibson B, Beech R, et al. What does 'access to health care' mean? J Health Serv Res Policy. (2002) 7:186–8. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082517

30. Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Aff. (2010) 29:766–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025

31. Guanais F, Regalia F, Perez-cuevas R, Anaya M. From the Patient's Perspective: Experiences with Primary Health Care in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank (2018).

32. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care. Paris: OECD Publishing (2020).

33. Levine DM, Landon BE, Linder J. A quality and experience of outpatient care in the united states for adults with or without primary care. JAMA Intern Med. (2019) 179:363–72. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6716

34. Baxter S, Johnson M, Chambers D, Sutton A, Goyder E, Booth A. The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Services Res. (2018) 18:350. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3161-3

35. Li M, Tang H, Liu X. Primary care team and its association with quality of care for people with multimorbidity: a systematic review. BMC Prim Care. (2023) 24:20. doi: 10.1186/s12875-023-01968-z

36. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in A. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). (2001).

37. Global Conference on Primary Health Care. Declaration of Astana: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf (accessed November 8, 2024).

38. Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y, Cartier T, Dedeu T, Hasvold T, et al. The strength of primary care in Europe: an international comparative study. Br J Gen Pract. (2013) 63:e742–50. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X674422

39. Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Alma-Ata 40: Primary Health Care at 40 years of Alma Ata, Situation in the Americas Washington, DC. (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health-care-conference/phc-regional-report-americas.pdf?sfvrsn=4afe25c7_2 (accessed November 8, 2024).

40. Ghebreyesus TA, Clark H. Health taxes for healthier lives: an opportunity for all governments. BMJ Global Health. (2023) 8:e013761. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013761

41. Paraje GR, Jha P, Savedoff W, Fuchs A. Taxation of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages: reviewing the evidence and dispelling the myths. BMJ Global Health. (2023) 8:e011866. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-011866

42. Bump JB, Reddiar SK, Soucat A. When do governments support common goods for health? Four cases on surveillance, traffic congestion, road safety, and air pollution. Health Syst Reform. (2019) 5:293–306. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1661212

43. Thamarangsi T. The “triangle that moves the mountain” and thai alcohol policy development: four case studies. Contemp Drug Probl. (2009) 36:245–81. doi: 10.1177/009145090903600112

44. Adulyanon S. Funding health promotion and disease prevention programmes: an innovative financing experience from Thailand. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. (2012) 1:201–7. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.206932

45. Pongutta S, Suphanchaimat R, Patcharanarumol W, Tangcharoensathien V. Lessons from the Thai health promotion foundation. Bull World Health Organ. (2019) 97:213–20. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.220277

46. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2010–2012. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564021

47. Palmer N, Mueller DH, Gilson L, Mills A, Haines A. Health financing to promote access in low income settings—how much do we know? Lancet. (2004) 364:1365–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17195-X

48. Ensor T, Ronoh J. Effective financing of maternal health services: A review of the literature. Health Policy. (2005) 75:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.02.002

49. World Health Organization. Universal health coverage (UHC). (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) (accessed February 26, 2025).

50. Amri MM, Logan D. Policy responses to COVID-19 present a window of opportunity for a paradigm shift in global health policy: an application of the Multiple Streams Framework as a heuristic. Glob Public Health. (2021) 16:1187–97. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1925942

51. United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022. New York: United Nations. (2022).

52. Amri M, Mohamood L, Mansilla C, Barrett K, Bump JB. Conceptual approaches in combating health inequity: a scoping review protocol. PLoS ONE. (2023) 18:e0282858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0282858

53. Amri MM, Jessiman-Perreault G, Siddiqi A, O'Campo P, Enright T, Di Ruggiero E. Scoping review of the World Health Organization's underlying equity discourses: apparent ambiguities, inadequacy, and contradictions. Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:70. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01400-x

54. Amri M, Enright T, O'Campo P, Di Ruggiero E, Siddiqi A, Bump JB. Health promotion, the social determinants of health, and urban health: what does a critical discourse analysis of World Health Organization texts reveal about health equity? BMC Global and Public Health. (2023) 1:25. doi: 10.1186/s44263-023-00023-4

55. Amri M, Enright T, O'Campo P, Di Ruggiero E, Siddiqi A, Bump JB. Investigating inconsistencies regarding health equity in select World Health Organization texts: a critical discourse analysis of health promotion, social determinants of health, and urban health texts, 2008–2016. BMC Global Public Health. 2:81. doi: 10.1186/s44263-024-00106-w

56. Sommer I, Griebler U, Mahlknecht P, Thaler K, Bouskill K, Gartlehner G, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in non-communicable diseases and their risk factors: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:914. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2227-y

57. World Health Organization. Financing Common Goods for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

58. Williams GA, Ulla Díez SM, Figueras J, Lessof S. Translating evidence into policy during the COVID-19 pandemic: bridging science and policy (and politics). Eurohealth. (2020) 26:2. Available online at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/336293/Eurohealth-26-2-29-33-eng.pdf

59. Amri MM, Drummond D. Punctuating the equilibrium: an application of policy theory to COVID-19. Policy Design Pract. (2021) 4:33–43. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2020.1841397

60. Kieny MP, Evans DB, Schmets G, Kadandale S. Health-system resilience: reflections on the Ebola crisis in western Africa. Bull World Health Organ. (2014) 92:850. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.149278

61. Nyenswah TG, Skrip L, Stone M, Schue JL, Peters DH, Brieger WR. Documenting the development, adoption and pre-ebola implementation of Liberia's integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) strategy. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:2093. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-17006-7

62. Nagbe T, Naiene JD, Rude JM, Mahmoud N, Kromah M, Sesay J, et al. The implementation of integrated disease surveillance and response in Liberia after Ebola virus disease outbreak 2015-2017. Pan Afr Med J. (2019) 33:3. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2019.33.2.16820

63. Ako-Egbe L, Seifeldin R, Saikat S, Wesseh SC, Bolongei MB, Ngormbu BJ, et al. Liberia health system's journey to long-term recovery and resilience post-Ebola: a case study of an exemplary multi-year collaboration. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1137865. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1137865

64. Phalkey RK, Yamamoto S, Awate P, Marx M. Challenges with the implementation of an Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system: systematic review of the lessons learned. Health Policy Plan. (2013) 30:131–43. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt097

65. M'ikanatha NM, Lynfield R, Julian KG, Van Beneden CA, Valk Hd. Infectious disease surveillance: a cornerstone for prevention and control. Infect Dis Surveill. (2013) 2013:1–20. doi: 10.1002/9781118543504.ch1

66. Karamagi H, Titi-Ofei R, Amri M, Zombre S, Kipruto H, Binetou-Wahebine Seydi A, et al. Cross country lessons sharing on practices, challenges and innovation in primary health care revitalization and universal health coverage implementation among 18 countries in the WHO African Region. PAMJ. (2022) 41:159. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2022.41.159.28913

67. World Bank Group. Governance and Development. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. (1992). Available online at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/604951468739447676/pdf/Governance-and-development.pdf (accessed February 10, 2025).

68. Commission of the European Communities. European Governance: a White Paper. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities (2001). Available online at: https://www.ab.gov.tr/files/ardb/evt/1_avrupa_birligi/1_6_raporlar/1_1_white_papers/com2001_white_paper_european_governance.pdf (accessed February 10, 2025).

69. Siddiqi S, Masud TI, Nishtar S, Peters DH, Sabri B, Bile KM, et al. Framework for assessing governance of the health system in developing countries: gateway to good governance. Health Policy. (2009) 90:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.08.005

70. Council of Europe. Recommendation CM/Rec(2012)8 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the Implementation of Good Governance Principles in Health Systems. Strasbourg: Council of Europe (2012).

71. Bertrand E. The European Commission's white paper on European Governance (2001) In: Encyclopédie d'histoire numérique de l'Europe. (2020). Available online at: https://ehne.fr/en/node/12261 (accessed February 10, 2025).

Keywords: health system, good governance, health system performance assessment, essential public health functions, common goods for health, global health, health system performance, international health

Citation: Amri M, Rajan D, Koch K, Earle AJ, Sparkes SP, Zhang Y, Saikat S and Bump JB (2025) Conceptually mapping how investing in essential public health functions (EPHFs) and common goods for health (CGH) can improve health system performance. Front. Public Health 13:1531837. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1531837

Received: 21 November 2024; Accepted: 24 February 2025;

Published: 19 September 2025.

Edited by:

Sam Agatre Okuonzi, Ministry of Health, UgandaReviewed by:

Alexandre Morais Nunes, University of Lisbon, PortugalJolem Mwanje, African Centre for Health Social and Economic Research, South Sudan

Copyright © World Health Organization 2025. Licensee Frontiers Media SA. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution IGO License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, adaptation (including derivative works), distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In any reproduction or adaptation of this article there should not be any suggestion that WHO or this article endorse any specific organisation or products. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. This notice should be preserved along with the article's original URL.

*Correspondence: Michelle Amri, bWljaGVsbGUuYW1yaUB1YmMuY2E=

†ORCID: Michelle Amri orcid.org/0000-0001-6692-3340

Dheepa Rajan orcid.org/0000-0001-8733-0560

Kira Koch orcid.org/0000-0002-3592-0574

Alexandra J. Earle orcid.org/0000-0001-9594-7210

Susan P. Sparkes orcid.org/0000-0003-3289-5745

Yu Zhang orcid.org/0000-0003-3708-2321

Sohel Saikat orcid.org/0000-0003-0952-6036

Jesse B. Bump orcid.org/0000-0003-1014-0456

Michelle Amri

Michelle Amri Dheepa Rajan2†

Dheepa Rajan2† Yu Zhang

Yu Zhang Sohel Saikat

Sohel Saikat