- 1Chongqing Blood Center, Chongqing, China

- 2Working Party on Hemovigilance of the Chinese Society of Blood Transfusion, Chongqing, China

- 3Fujian Blood Center, Fuzhou, China

- 4Shanghai Red Cross Blood Center, Shanghai, China

- 5Anhui Blood Center, Hefei, China

Background: While international cooperation in blood donor safety surveillance is growing, data from China’s national network remains unpublished. We have established a national donor hemovigilance system to collect data and analyze the current state of blood donor safety in China.

Materials and methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study on donor hemovigilance data reported to the national network from 2020 to 2022 in China. Demographic information and data on adverse donor reactions (ADRs) among blood donors were collected from 85 Blood Services. R software (version 4.2.3) was used for all statistical analyses. Frequency and composition rates were used to describe the data of total donation, as well as data on the different types of ADRs. The Chi-square test was used to analyze risk factors for Vasovagal reactions (VVRs) and inter-group comparisons of VVRs stratified by age (18–22; 23–29; 30–39; 40–49; 50–60), gender (female/male), donation history (first time/repeat), and blood donation volume (200 mL/300 mL/400 mL), type of collection site (fixed site/blood collection shelter/blood collection vehicle/others) and donor source (individual/social group/high school). Lastly, risk factors for blood donation-related syncope were explored.

Results: Between 2020 and 2022, 32,523 cases of ADRs were reported, among which VVRs accounted for 96.8% of all reactions. The overall reported incidence of ADRs was 12.577%. Notably, the incidence of VVRs decreased with increasing donor age. Additionally, the estimated incidences of VVRs were higher among female donors (13.600%) and first-time donors (18.536%) compared to male donors (11.205%) or repeat donors (5.819%). Moreover, 1,120 VVRs with syncope were recorded, accounting for 3.56% of total VVR cases. Finally, donors from outdoor blood collection sites (0.590%) and groups (1.073%) were at a significantly higher risk of syncope compared to those from indoor blood donation sites (0.438%) and individual donors (0.174%).

Conclusion: The reported incidence rate of ADRs related to blood donation was very low. The higher prevalence of VVR and syncope in young, females, first-time donors, college students, and donating in mobile vehicles.

Introduction

Recently, the reporting, treatment, and prevention of adverse donor reactions (ADRs) have garnered extensive attention (1, 2). These activities form the core of donor hemovigilance (DHV), which refers to the systematic surveillance of ADRs and incidents throughout the whole blood donation process to enhance quality and safety for blood donors (3). Blood donation is a generally safe procedure well-accepted by donors. Nevertheless, a minority of donors may experience undesired ADRs of variable severity during or following blood donation (4). While the majority of blood donors rapidly recover from ADRs with supportive management, even experienced donors are less likely to return following mild complications (5). In recent years, numerous studies have identified risk factors of adverse reactions related blood donation and demonstrated the effectiveness of intervention measures (1, 5, 6).

The International Hemovigilance Network (IHN) developed a system for the annual collection of national aggregate hemovigilance data in 2006 (7), with over 30 national hemovigilance systems globally participating in the program and 24 having reported ADR data to IHN by 2016. However, the latest IHN publication did not include data on ADRs in China (8). In 2021, IHN published a large dataset of ADRs reports over 11 years (2006–2016), covering 138 countries and 155 million blood donors. The overall reported incidence rate of ADRs was 6%, with a median of 3.2% (IQR 1. 1 ~ 10. 1). The average incidence rate of DRVR was 4.6%, with a median incidence rate of 3.1% (IQR 0.6–7.7). The median incidence rates of adverse reactions related to venipuncture (hematoma) were 0.39% (IQR 0.31–1.2) for whole blood donation and 4.2% (IQR 0.69–5.6) for apheresis platelet donation. A recent meta-analysis documented that the incidence of ADRs during or after whole blood donation was 13.6% in China (9). Despite several studies investigating ADRs in the Chinese population, large-scale surveys remain limited.

To compare and benchmark ADR rates across Blood Services and regions, the Chinese Society of Blood Transfusion (CSBT) established a national hemovigilance working party in 2017 and implemented nationwide ADR surveillance in China. A previous article detailed the establishment and development of a national blood donor hemovigilance system in China (10). Between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2022, formal ADR data collection was conducted using a web-based management system. In this paper, the collected ADR data were analyzed to characterize the profile of blood donors who experienced ADRs in China and promote data utilization and visibility across China.

Materials and methods

Study population

All blood donors from 85 Blood Services between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2022 were included in the study. These accounted for 18.8% of all Blood Services in China. From 2020 to 2022, more than 8.5 million blood donors from the Blood Services participating in this study, accounting for 17.8% of the total number of all blood donors in China during this period. Donors met the standard blood donor eligibility for whole blood and component donations established by the China Ministry of Health (11). Healthy individuals aged 18–55 years are eligible for blood donation for the first time, and repeat donors who met the blood donor criteria with no previous ADRs are eligible up to the age of 60 years. The minimum body weight and hemoglobin level were 50 kg and ≥120 g/L for male donors and 45 kg and ≥115 g/L for female donors, respectively. The minimum interval between two whole blood donations was 6 months, and 14 days for apheresis platelets. After registration and physical examination pre-donation, donors received counseling from professional staff and could choose to donate 200 mL, 300 mL, or 400 mL for whole blood and a single or double treatment dose for apheresis platelets. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Blood Center (No. 2021-04-26).

ADR classification criteria and definition

The definition and imputability for ADRs used in this study was proposed by the Working Group on Donor Vigilance of the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) Working Party on Hemovigilance, in collaboration with IHN and the AABB Donor Hemovigilance Working Group in 2014 (12). Primary ADRs were classified into four major types: complications with predominantly local symptoms, generalized symptoms (vasovagal reactions, VVRs), complications related to apheresis, and other complications related to blood donation. To enhance specificity, the four major ADR categories were subdivided into additional subcategories. We include and exclude the received data based on this criterion.

ADR and denominator data collection

For consistency, a standardized data collection form, the ADRs report form, was designed and issued to Blood Services for collecting ADR data. For each reaction, donor demographic information (age, gender, weight, height, collection site, and donation history), signs and symptoms, interventions, follow-up information, and reaction type were collected. All reactions, irrespective of severity, were recorded and reported to CSBT. Multiple types of ADRs in a single blood donor were individually recorded and reported. The collected information was registered and audited in a dedicated database. A specific online system was designed for data entry, submission, analysis, and storage. Blood Services reported the collected ADR data monthly via a dedicated web platform1 by liaison officers (10). Denominator data were collected using a uniform data collection form from early 2021 to 2023. Donations were classified by age group, donation history, gender, blood donation volume, and type of blood donation site were collected.

Statistical analysis

All ADR datasets were subjected to standardized data preprocessing. To mitigate the impact of missing data, data were supplemented by contacting liaison officers from Blood Services. Frequency and composition rates were used to describe the data of total donation, as well as data on the different types of ADRs. The Chi-square test was used to analyze risk factors for Vasovagal reactions (VVRs) and inter-group comparisons of VVRs stratified by age (18–22; 23–29; 30–39; 40–49; 50–60), gender (female/male), donation history (first time/repeat), and blood donation volume (200 mL/300 mL/400 mL), type of collection site (fixed site/blood collection shelter/blood collection vehicle/others) and donor source (individual/social group/high school). The same stratified analysis was further conducted on blood donors who experienced syncope to determine the risk factors. R software (version 4.2.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, New Zealand) was employed for statistical analyses (13). The Odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated to compare the reported incidence of VVR with different characteristics, p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, and all p values were tested using a bilateral test.

Results

Donor characteristics

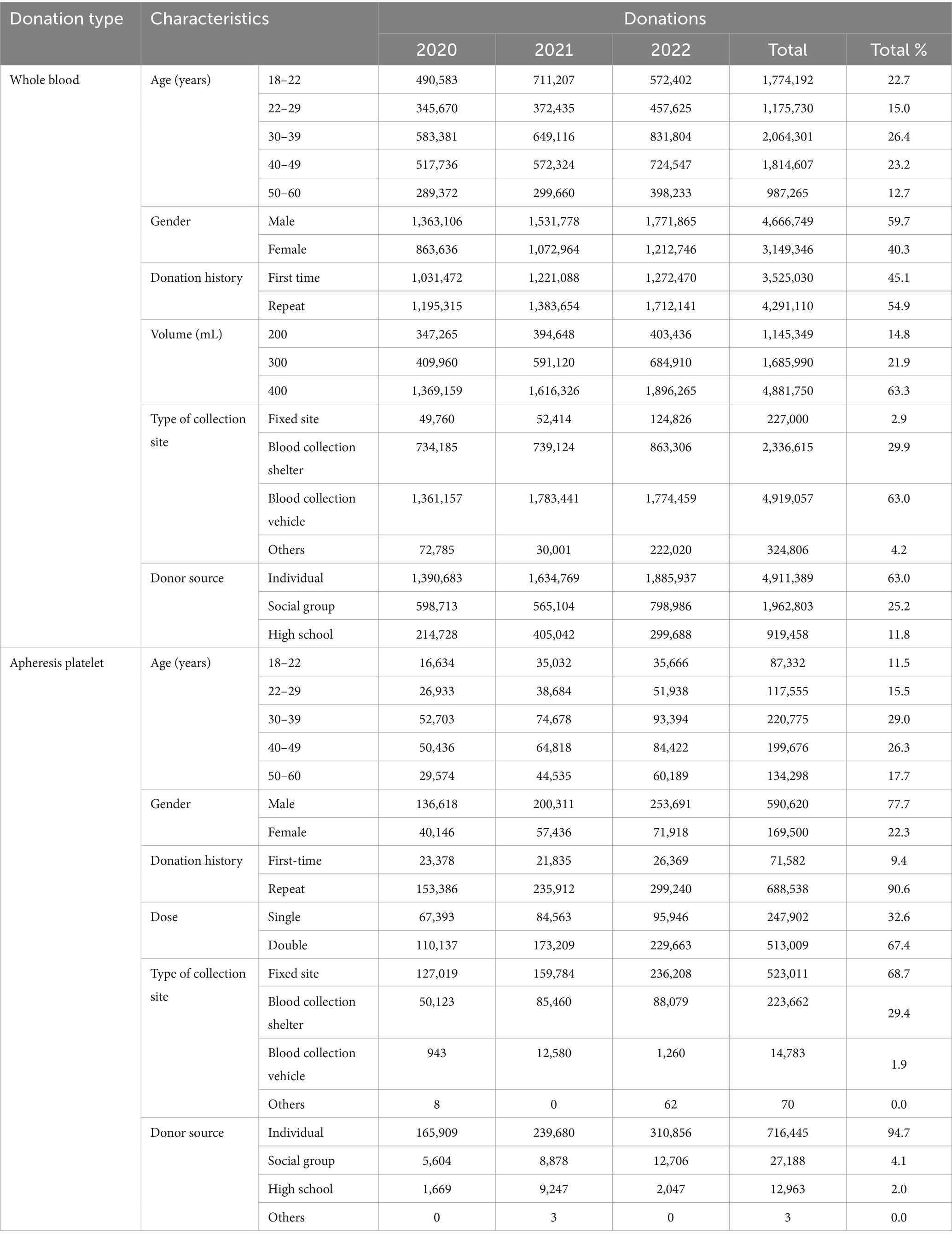

A total of 8,575,731 blood donations, comprising 7,816,095 whole blood donations and 759,636 apheresis platelet donations, were registered at Blood Services during the study period. The general donor characteristics for the study population are listed in Table 1. The analysis of the characteristics of whole blood donors showed that, donors aged 30–39 (26.4%), 40–49 (23.2%), and 18–22 (22.7%) account for 72.3% of the total whole blood donors. Male donors (59.7%) outnumber female donors (40.3%). Repeat donors (54.9%) were more than first-time donors. The majority of donors contributed 400 mL of blood (63.3%). Blood collection from mobile blood donation vehicles was the most common (63.0%). Individual donors (63.0%) far exceed those from social and university groups.

Among apheresis platelet donors, those aged 30–39 (29.0%) and 40–49 (26.3%) accounted for 55.3% of the total apheresis platelet donors. Male donors (77.7%) were more than female donors (22.3%). Repeat donors (90.6%) were significantly more than first-time donors. The majority of donors contributed two therapeutic doses of platelets (67.4%). Donations were mainly made at fixed donation sites (68.7%). At the same time, individual donors were the main source (94.69%).

Classification of ADRs

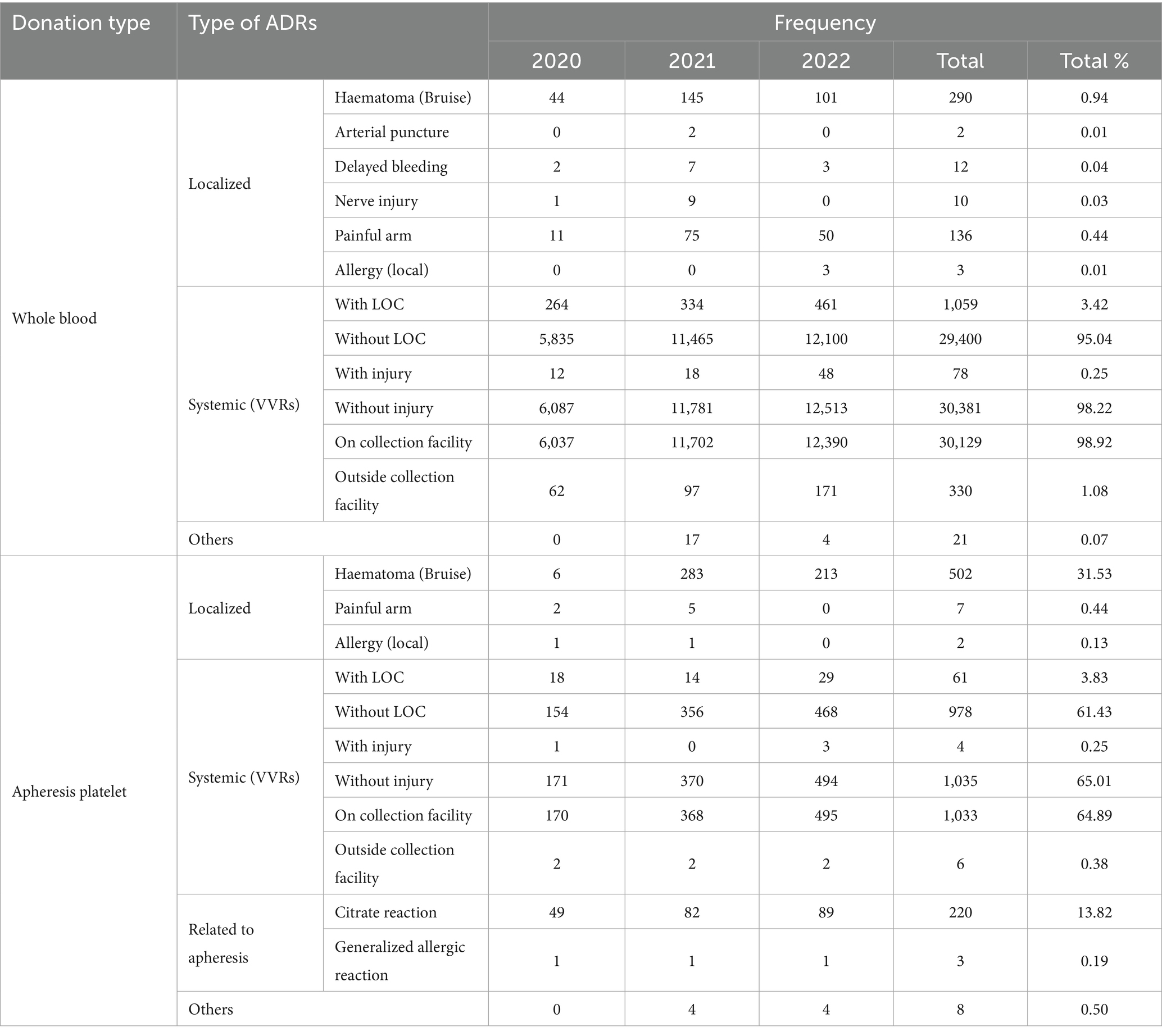

A total of 32,523 donations with ADRs were reported in Blood Services, among which 191 cases experienced two types of ADRs during the same donation from 2020 to 2022. Of these ADRs, 30,933 ADRs were related to whole blood donors, and the remaining 1,781 ADRs were associated with apheresis platelet donors. VVRs (31,498; 96.32%) were the most prevalent type of ADRs in blood donors, followed by hematoma (792; 2.56%). Next, the three VVR subclusters were subdivided according to the pre-defined grouping criteria. Among the 31,498 donors who experienced VVRs, loss of consciousness (LOC) was reported in 1,120 (3.36%). When ADRs could not be classified into the existing categories, they will be classified under the “Other” category. For example, a blood donor has a fever after donating blood (Table 2).

Incidence of ADRs

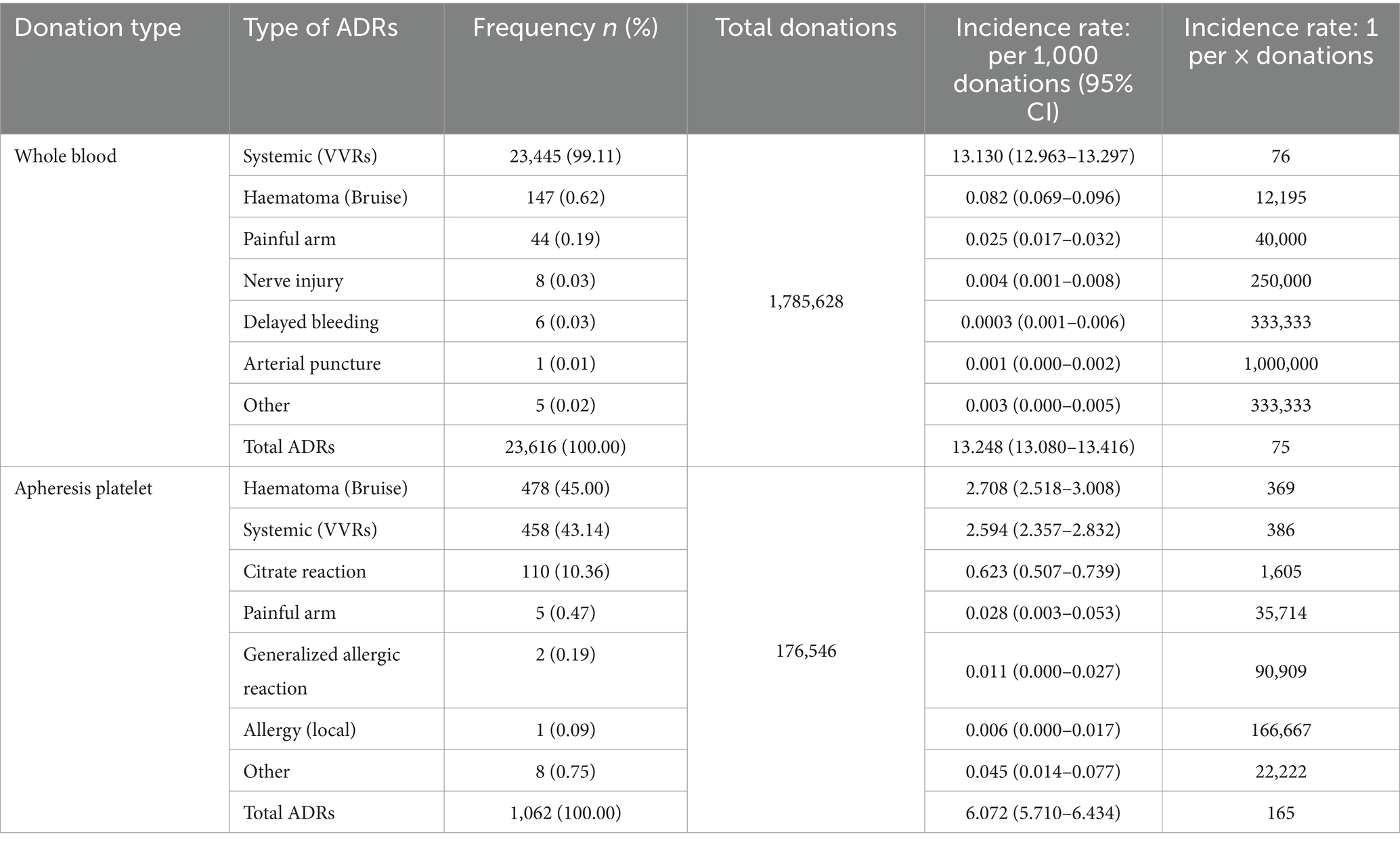

The reported ADR incidence was 12.577% (24,678/1,962,174) between 2020 and 2022. In whole-blood donors, the incidence of ADRs was 13.248% (23,655/1,785,628), which was significantly higher than the 6.015% (1,062/176,546) observed in apheresis platelet donors (p = 0.0013). The frequency and incidence of each ADR category are detailed in Table 3.

Risk factors for VVRs

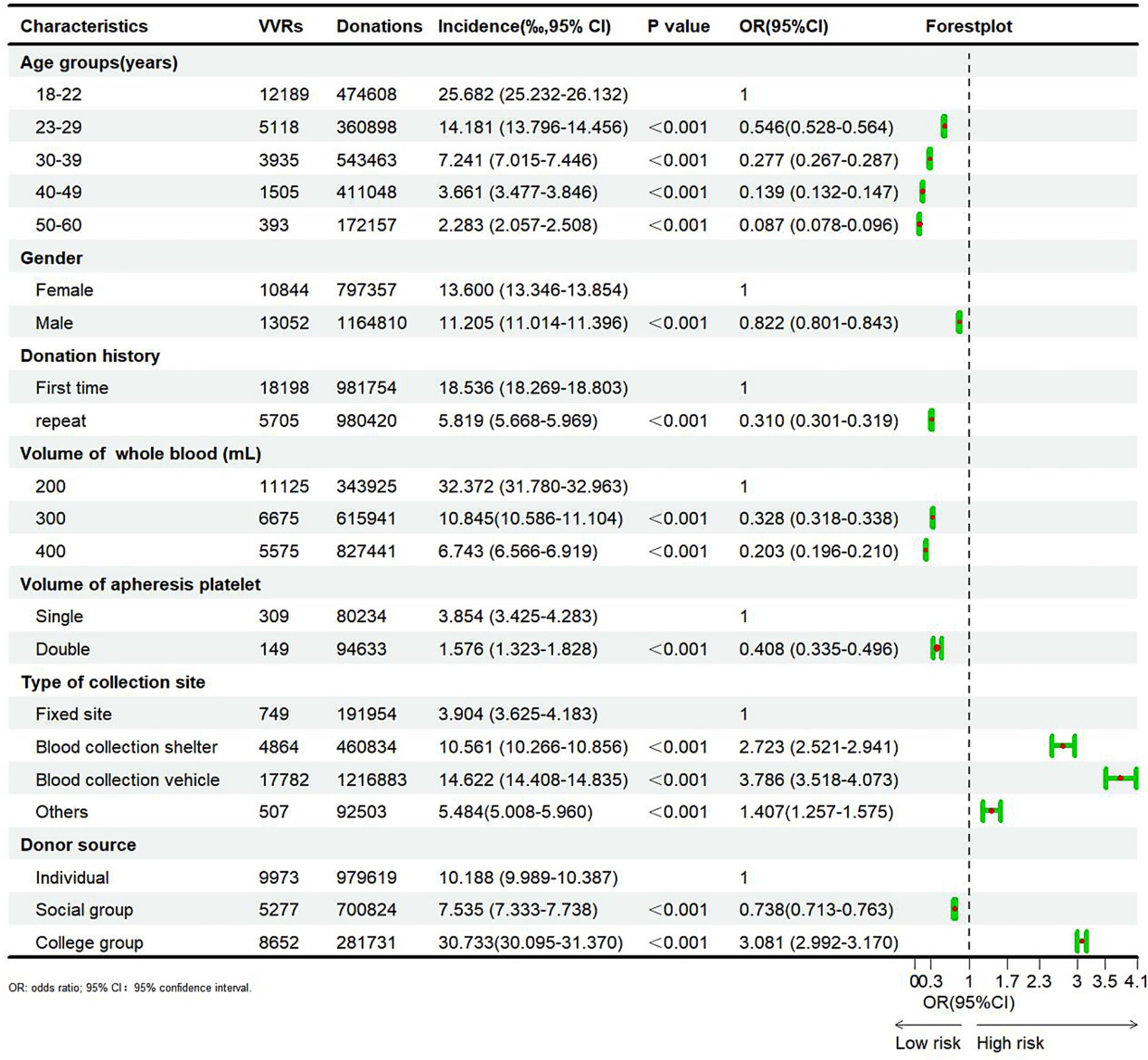

The results of the chi-square test regarding risk factors for VVRs are illustrated in Figure 1. Of note, the incidence of VVRs decreased with advancing age (p < 0.01). It was highest in the 18–22 (25.682%) age group and lowest in the 50–60 age group (2.283%). Compared with the 18–22 age group, the odds ratios (OR) for VVR were 0.546, 0.277, 0.139, and 0.087 in the 22–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50–60 age groups, respectively.

The incidence of VVRs in male blood donors (11.205%) was significantly lower than that in females (13.600%) (p < 0.01, OR = 0.822). Likewise, the incidence of VVRs was significantly lower than in repeat donors (5.819%) compared to first-time donors (18.536%) (p < 0.01, OR = 0.310).

The incidence of VVRs decreased with the increasing blood donation volume. Among whole blood donors, the incidence of VVRs (32.372%) was significantly higher among those donating 200 mL compared to those donating 300 mL (10.845%) and 400 mL (6.743%) (p < 0.01). The same trend was observed for apheresis platelet donors. Additionally, the incidence of VVRs was significantly lower at fixed blood donation sites compared to other blood donation sites (p < 0.01). Compared with individual blood donors (10.188%), the incidence of VVRs was significantly lower in social group donors (7.535%) and significantly higher in college group donors (30.733%) (p < 0.01, OR = 0.738 and 3.081).

Risk factors for syncope

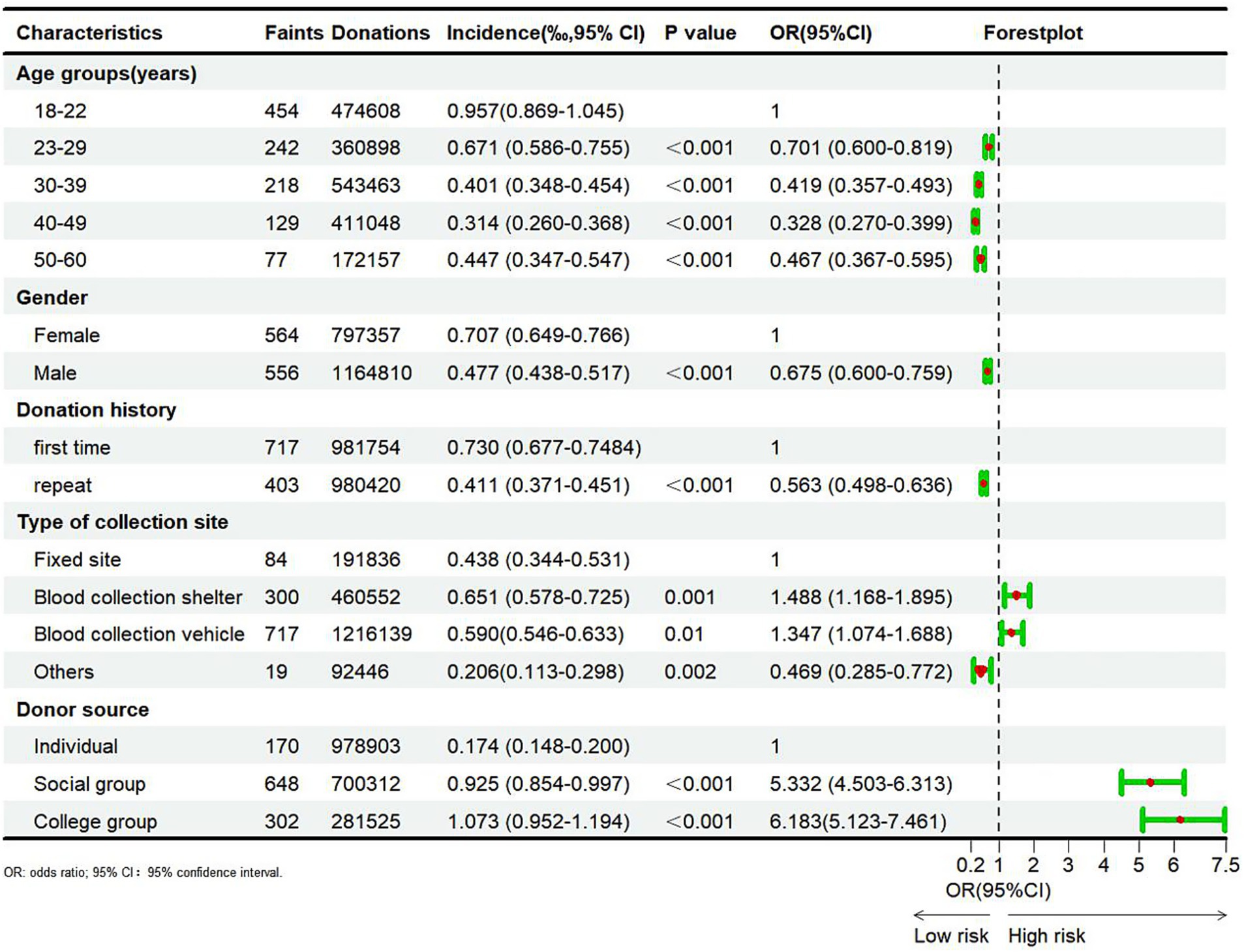

A total of 1,120 VVRs with syncope were reported across sentinel Blood Services from 2020 to 2022, accounting for 3.56% of all total VVR cases (1,120/31,498). The results of the chi-square and Cochran-Armitage tests regarding risk factors for syncope are listed in Figure 2. Significant correlations were noted between the incidence of syncope and age, gender, donation history, type of collection site, and donor source (p < 0.05). The incidence of syncope decreased with advancing age (p < 0.001). Specifically, the incidence of syncope was highest in the 18–22 (0.957%) age group and lowest in the 40–49 (0.314%) age group. Compared with the 18–22 age group, the odds ratios (OR) for syncope in the 22–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50–60 age groups were 0.701, 0. 419, 0.328, and 0.467, respectively. Furthermore, the incidence of syncope was significantly lower in male donors (0.477%) compared to female donors (0.707%) (p < 0.001, OR = 0.675). Similarly, the incidence of syncope was significantly lower in repeat donors (0.411%) compared to first-time donors (0.730%) (p < 0.001, OR = 0.563). Differences in the incidence of syncope across blood donation sites were statistically significant, with its incidence being lower in fixed blood donation sites compared to blood donation vehicles or shelters. Finally, the incidence of syncope in social group donors (0.925%) and university donors (1.073%) was significantly higher compared to individual donors (0.174%) (p < 0.001, OR = 5.332 and 6.183).

Discussion

VVRs accounted for 98.47% and 58.34% of all ADRs in whole blood and apheresis platelet donors from 2020 to 2022 in China, respectively. It is worthwhile emphasizing that the rate of VVRs in whole blood donors was higher than that reported in Italy from 2016 to 2019 (93.3%) (14), IHN (83%) (15), and the 2023 European Commission SARE report (82%) (16). The rate of VVRs among apheresis platelet donors was lower than that recorded in Italy (70.3%) from 2016 to 2019 and comparable with that of IHN (57%) and the 2023 European Commission SARE report (77%). Among whole blood donors, local ADRs such as hematoma following blood donation accounted for only 0.94% of all ADRs, which was markedly lower than the 18.69% reported by IHN (8), given that whole blood donors often discover hematomas after leaving the blood collection site and may not inform Blood Services of the adverse reaction. However, the longer process of apheresis platelet collection increases the likelihood of on-site diagnosis, and the proportion of hematomas recorded in apheresis platelet donors was higher at 31.53%.

According to earlier studies, Blood Services did not always collect and report all ADR data (10). To mitigate this bias and reflect the real rate of ADRs, data from Blood Services with a reported incidence of over 5% were used to calculate the incidence of ADRs to capture a more accurate representation of blood donor safety in China. These Blood Services accounted for 20% of the total number of participating Blood Services, thereby presenting a more reliable basis for assessing adverse associated with ADRs following blood donation in China.

The total reported incidence of whole blood ADRs was 13.248%. The result was consistent with the results of a meta-analysis published in 2021 that investigated the incidence of ADRs in Chinese whole blood donors across 36 studies, revealing a combined reported incidence of 13.6% (9). Compared with whole blood donors, the overall reported incidence of ADRs in platelet donors was lower (6.072%). These results are lower than those reported in a meta-analysis examining the incidence of ADRs in platelet apheresis donors published in 2024 (including 91 articles), which reported a combined incidence of 2.65% in China (17). The incidence of ADRs reported by apheresis platelet donors is strongly correlated with awareness and reporting practices. The results of an analysis from Denmark’s donor hemovigilance system demonstrated that the reported incidence of citrate reaction ranges from 0% to 45.8% (18), attributable to differences in information systems, methods of detection, passive reception, reporting personnel, and the possibility of under reporting based on donor feedback.

Considering that VVRs were the most prevalent ADRs, risk factors of VVRs were explored among Chinese blood donors, focusing on age, gender, blood donation history, blood donation site, and donor source. In terms of age groups, the risk of VVRs was highest in blood donors aged 18–22 years and decreased with increasing age, consistent with the AABB reports between 2012 and 2017 (19). The 18–22 age group largely consisted of college students, mostly first-time blood donors. Their limited knowledge of blood donation and social adaptability, could easily lead to mental tension during blood donation, resulting in VVRs (20). Regarding gender, female blood donors were at a higher risk for VVRs herein, attributable to their lower body weight (21). Moreover, first-time blood donors were approximately three times more likely to experience VVRs compared to repeat blood donors, highlighting the need for education and support for first-time blood donors. Interestingly, contrary to our expectations, the incidence of VVRs was highest in blood donors who donated 200 mL of whole blood. The incidence of VVRs in apheresis platelet donors was also higher in those who donated single unit compared with those who donated double units, indicating that in China, donations of up to 400 mL of whole blood and two treatment doses of platelets are not significant risk factors for inducing VVRs (22). Of course, this is related to the conditions of blood donors, first-time, young, female blood donors often choose to donate smaller volume of blood. As many countries do not practice whole blood volume diversity, this point would merit further investigation. The incidence of VVRs also varied across blood donation sites. Specifically, the incidence of VVRs was highest in blood donation vehicles, followed by the fixed blood donation house, whilst the incidence of VVRs was lowest in blood donation stations. It is worth noting that the confined space and higher personnel density in blood donation vehicles, as well as the elevated noise levels and poor air circulation, may contribute to discomfort among donors, thus increasing the incidence of VVRs (23). Blood donors in China can originate from individuals, social groups, and college groups. The incidence of VVRs in college groups was substantially higher than that of blood donors from other sources due to their age and blood donation history (24, 25).

Blood donation-related vasovagal syncope may lead to severe complications such as fractures, dental injuries, and even death (26). Among the 1,120 cases of syncope recorded in this study, 677 cases occurred during blood collection, whereas 371 cases occurred during the rest period after blood donation, highlighting the need to monitor donors after blood donation and before allowing them to leave the blood collection site. Herein, risk factors for syncope were investigated. Age groups at risk of syncope were similar to those observed with VVRs. Nonetheless, the risk of syncope in the 50–60 age group was higher than that in the 30–49 age group, with the majority of blood donors in China being repeat blood donors, indicating that the risk of syncope after blood donation in the older population warrants increased attention. Although previous studies have established that repeat blood donors remain at risk for syncope (27), the results of this study demonstrated that repeat blood donors had a significantly lower risk of syncope compared to first-time blood donors. Inconsistent with the findings for VVRs, the risk of syncope among social group and college group donors was 5–6 times higher than that of individual donors, which may be related to the group dynamics associated with VVRs (28).

Some limitations of this study cannot be overlooked. Firstly, given the lack of connectivity between the blood donor management information system among participating blood stations, detailed information on all blood donors was not obtained. Therefore, the multivariate analysis method was not employed to examine risk factors for ADRs, and only univariate analyses were conducted. Secondly, at the beginning of this project, a new evaluation tool for rating the severity rating of ADRs had not been published; consequently, it was not used for analysis. Finally, rare, severe, long-term ADRs were not explored and may be addressed in future studies using the BEST methods in multi-center studies (29).

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first large-scale analysis of national donor hemovigilance, providing an initial reflection of the current state of blood donor safety in China. The incidence of ADRs was low and consistent with the rates reported by other national haemovigilance systems. Among donors experiencing VVRs and syncope, the risk was higher in first-time females, those donating on blood donation mobiles, and college groups.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Chongqing Blood Center. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JY: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation. WZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation. DX: Writing – review & editing. QX: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. XG: Writing – review & editing. JZ: Writing – review & editing. YX: Writing – review & editing. XH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Chongqing Science and Health Research Fund (2022ZDXM031).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating sites for their input, as well as everyone who has provided feedback data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1567370/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Storch, EK. Donor hemovigilance: a call to arms. Transfusion. (2020) 60:1115–7. doi: 10.1111/trf.15854

2. Wood, EM, Whitaker, BI, Townsend, M, and Narayan, S. How we forecast tomorrow’s haemovigilance. Transfus Clin Biol. (2024) 31:114–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2024.03.001

3. Wiersum-Osselton, JC, Marijt-van der Kreek, T, and de Kort, WL. Donor vigilance: what are we doing about it? Biologicals. (2012) 40:176–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2011.12.003

4. Goldman, M, Land, K, Robillard, P, and Wiersum-Osselton, J. Development of standard definitions for surveillance of complications related to blood donation. Vox Sang. (2016) 110:185–8. doi: 10.1111/vox.12323

5. Thijsen, A, Thorpe, R, Davison, TE, Nguyen, L, and Masser, B. The vasovagal reaction experience among blood donors: a qualitative study of factors that affect donor return. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 282:114142. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114142

6. Sun, LY, Yu, Q, He, CM, and Wang, SX. Sociodemographic factors related to adverse donor reactions in Shenzhen. Int J Gen Med. (2023) 16:5493–9. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S443682

7. Politis, C, Wiersum-Osselton, J, Richardson, C, Grouzi, E, Sandid, I, Marano, G, et al. Adverse reactions following transfusion of blood components, with a focus on some rare reactions: reports to the international Haemovigilance network database (ISTARE) in 2012-2016. Transfus Clin Biol. (2022) 29:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2022.03.005

8. Wiersum-Osselton, JC, Politis, C, Richardson, C, Goto, N, Grouzi, E, Marano, G, et al. Complications of blood donation reported to haemovigilance systems: analysis of eleven years of international surveillance. Vox Sang. (2021) 116:628–36. doi: 10.1111/vox.13048

9. Yang, J, Chen, M, He, T, and Huang, X. Incidence of adverse reactions to whole blood donation in China: a meta-analysis. Chin J Blood Transfus. (2021) 34:376–81. doi: 10.13303/j.cjbt.issn.1004-549x.2021.04.013

10. Yang, J, Fan, D, Xie, D, Guo, X, Zhu, W, He, T, et al. First donor haemovigilance system at a national level in China: establishment and improvement. Vox Sang. (2023) 118:357–66. doi: 10.1111/vox.13421

11. China’s Ministry of Health. Whole blood and component donor selection requirements (GB 18467-2011). Available online at: https://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/s9493/201207/55286/files/1739782056847_28303.pdf. (Accessed December 29, 2023).

12. ISBT working party on haemovigilance in collaboration with the International Haemovigilance Network and the AABB Donor Haemovigilance Working Group. Standard for surveillance of complications related to blood donation. Available online at: https://isbtweb.org/isbt-working-parties/haemovigilance/resources.html. (Accessed April 11, 2024).

13. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2022).

14. Piccinini, V, Marano, G, Catalano, L, Pati, I, Veropalumbo, E, de Waure, C, et al. Vasovagal reactions in whole blood and apheresis donors: a cross-sectional study on donor haemovigilance data from 2016 to 2019 in Italy. Blood Transfus. (2022) 20:281–91. doi: 10.2450/2021.0114-21

15. Politis, C, Wiersum, JC, Richardson, C, Robillard, P, Jorgensen, J, Renaudier, P, et al. The international haemovigilance network database for the surveillance of adverse reactions and events in donors and recipients of blood components: technical issues and results. Vox Sang. (2016) 111:409–17. doi: 10.1111/vox.12447

16. European Commission. Summary of the 2023 annual reporting of serious adverse reactions and events for blood and blood components. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/blood_tissues_organs/docs/2023_sare_blood_summary_en.pdf. (Accessed April 11, 2024).

17. Shen, L, Feng, H, Niu, D, and Huang, X. Reported incidence of adverse reactions in plateletapheresis donors in China: a meta-analysis. Chin J Blood Transfus. (2024) 37:223–37. doi: 10.13303/j.cjbt.issn.1004-549x.2024.02.017

18. Mikkelsen, C, Paarup, HM, Bruun, MT, Pedersen, LØ, Hasslund, S, Larsen, R, et al. The new donor vigilance system in Denmark reveals regional differences in adverse reactions supposedly caused by variation in the registration. Vox Sang. (2022) 117:321–7. doi: 10.1111/vox.13202

19. AABB Donor Hemovigilance Working Group. 2012–2017 AABB donor Hemovigilance highlights. Available online at: https://www.aabb.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/resources/2012-2017-aabb-donor-hemovigilance-highlights.pdf. (Accessed October 20, 2020).

20. Eder, AF, Hillyer, CD, Dy, BA, Notari, EP 4th, and Benjamin, RJ. Adverse reactions to allogeneic whole blood donation by 16- and 17-year-olds. JAMA. (2008) 299:2279–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.19.2279

21. Orru’, S, Poetzsch, K, Hoffelner, M, Heiden, M, Funk, MB, Keller-Stanislawski, B, et al. Blood donation-related adverse reactions: results of an online survey among donors in Germany (2018). Transfus Med Hemother. (2021) 48:272–83. doi: 10.1159/000516049

22. Wiersum-Osselton, J, Romeijn, B, van den Brekel, E, van Dongen, A, Hermans, F, Bokhorst, A, et al. Can we prevent vasovagal reactions in young inexperienced whole blood donors? A placebo controlled study comparing effects of a 330 vs 500 mL water drink prior to donation. Transfusion. (2019) 59:555–65. doi: 10.1111/trf.15065

23. Hashizume, T, Kondo, G, Ishimaru, F, Ikeda, Y, Kagawa, K, Kunii, N, et al. Development and validation of a scoring system to predict vasovagal reaction upon whole-blood donation. Vox Sang. (2024) 119:300–7. doi: 10.1111/vox.13579

24. France, CR, France, JL, Himawan, LK, Lux, P, and McCullough, J. Donation related fears predict vasovagal reactions and donor attrition among high school donors. Transfusion. (2021) 61:102–7. doi: 10.1111/trf.16099

25. Paalvast, Y, Díaz Padilla, N, Bruijns, S, Wiersum-Osselton, J, and Molenaar, T. Donor complication rates in whole blood, plasma and platelet donors: age versus experience. Transfusion. (2024) 64:854–65. doi: 10.1111/trf.17759

26. SHOT. Annual SHOT report 2021. https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/ff51e2d1-796b-426f-a941-db6cb53cd0bc_en?filename=2023_sare_blood_summary_en.pdf. (Accessed October 13, 2023).

27. Morand, C, Coudurier, N, Rolland, C, Thoret, S, Legrand, D, Tiberghien, P, et al. Prevention of syncopal-type reactions after whole blood donation: a cluster-randomized trial assessing hydration and muscle tension exercise. Transfusion. (2016) 56:2412–21. doi: 10.1111/trf.13716

28. Ditto, B, Byrne, N, Holly, C, and Balegh, S. Social contagion of vasovagal reactions in the blood collection clinic: a possible example of mass psychogenic illness. Health Psychol. (2014) 33:639–45. doi: 10.1037/hea0000053

Keywords: adverse reaction, donor hemovigilance, syncope, vasovagal reaction, risk factor

Citation: Yang J, Zhu W, Xie D, Xu Q, Guo X, Zeng J, Xu Y and Huang X (2025) Profile and risk factors of blood donors who experienced adverse reactions: a cross-sectional study on donor hemovigilance data reported to the national network from 2020 to 2022 in China. Front. Public Health. 13:1567370. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1567370

Edited by:

Jessica Christanti, Soegijapranata Catholic University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Michele Santodirocco, Home for Relief of Suffering (IRCCS), ItalyYared Paalvast, Sanquin Diagnostic Services, Netherlands

Copyright © 2025 Yang, Zhu, Xie, Xu, Guo, Zeng, Xu and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongzhu Xu, Y3FiY3h5ekAxNjMuY29t; Xia Huang, Y3NidGh2QGNzYnQub3JnLmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

Junhong Yang

Junhong Yang Wenqin Zhu3†

Wenqin Zhu3† Xia Huang

Xia Huang