- 1UFR de Médecine, Université de Picardie Jules Verne, Rue des Louvels, Amiens, France

- 2School of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, Jounieh, Lebanon

- 3Department of Infectious Disease, Bellevue Medical Center, Mansourieh, Lebanon

- 4Department of Infectious Disease, Notre Dame des Secours, University Hospital Center, Byblos, Lebanon

- 5College of Pharmacy, Gulf Medical University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates

- 6Department of Biomedical Sciences, School of Arts and Sciences, Lebanese International University, Bekaa, Lebanon

- 7Center for Applied Mathematics and Bioinformatics (CAMB), Gulf University for Science and Technology (GUST), Hawally, Kuwait

- 8Department of Social and Education Sciences, School of Arts and Sciences, Lebanese American University, Jbeil, Lebanon

- 9Department of Psychiatry "Ibn Omrane", The Tunisian Center of Early Intervention in Psychosis, Razi Hospital, Maouba, Tunisia

- 10Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, Tunis El Manar University, Tunis, Tunisia

- 11Department of Psychology, College of Humanities, Effat University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 12Applied Science Research Center, Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan

Background: The current study aimed to investigate the factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Arabic adaptation of the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale, and to examine a newly developed single-item measure of financial stress, the Single-Item Financial Stress scale (SIFiS), in a sample of Lebanese adults.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, 403 participants completed an Arabic-translated version of the IFDFW scale via an online survey. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to validate the scale.

Results: A one-factor structure was supported by the analysis. Internal reliability was excellent, with very high omega and alpha coefficients for the IFDFW scale (ω = 0.95, α = 0.95). A significantly lower mean IFDFW score was found in males compared to females. On the other hand, no significant differences were found between males and females on the SIFiS scores. Greater financial burden was significantly associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Conclusion: The findings confirm that the Arabic versions of the IFDFW scale and the SIFiS are valid and reliable. Their use is therefore recommended in various settings among Arabic-speaking adults. These simple and straightforward measurement tools may improve cross-cultural studies on financial well-being.

Background

Financial wellness has gained increasing attention among policymakers, economists, and mental health professionals. It is commonly defined as “the perception of being able to sustain current and anticipated desired living standards and financial freedom” (1). However, financial well-being is susceptible to financial distress, which refers to the perceived financial strain and negative emotional responses to one’s financial situation, such as stress, worry about expenses, and dissatisfaction with financial stability (2). Financial well-being is shaped by the interaction of personal, contextual, and behavioral factors that influence an individual’s financial experiences. These include one’s income (3), education (4), and employment stability (5), as well as behavioral financial practices like saving, budgeting (6), and credit management (7), which are associated with satisfaction. In contrast, impulsive spending and overborrowing have been linked to increased financial stress (8, 9). Contextual elements, such as economic conditions and inflation, also affect one’s ability to manage finances competently (10). Beyond its economic implications, financial stress is closely linked to mental health, as it can worsen anxiety and depression, and is increasingly recognized as a key social determinant of health influencing both psychological and physical outcomes (11–13).

Financial well-being is commonly assessed using both objective indicators (income, savings, debt) and subjective perceptions, such as control, security, and satisfaction. Recent research (1, 14, 15) suggests that subjective measures often outperform traditional metrics as they better reflect individuals’ lived experiences. These perceptions vary widely, even among those in similar financial situations. For instance, a high-income individual with heavy expenses may feel less financially secure than someone with modest means but greater stability. This growing emphasis on subjective assessment reflects the need for tools that capture the complexity and personal nature of financial well-being across diverse contexts.

The InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being (IFDFW) Scale (16), developed by Prawitz et al. through a Delphi study and rigorous statistical testing, is a widely used tool for assessing financial well-being. It consists of eight self-report items rated on a 10-point Likert scale continuum, measuring both financial stress and satisfaction. Higher scores indicate better perceived control and well-being, while lower scores reflect financial distress and insecurity. Example items include: “How do you feel about your current financial situation?” and “How frequently are you concerned about whether you can pay for customary monthly living expenses?.” The original validation paper supported a one-factor structure, with strong item loadings (0.83–0.93) and excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.95).

To ensure its cross-cultural relevance, the IFDFW Scale has been adapted into several languages, including Malay (17), Brazilian Portuguese (18), German, Italian, Dutch, Slovenian, and Spanish (19). These adaptations consistently supported the original one-factor structure and demonstrated strong psychometric properties. Internal consistency was excellent across most versions (Cronbach’s α > 0.90). Fit indices such as the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were consistently excellent, while the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ranged from acceptable to excellent. However, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) values varied: they were excellent in Slovenia, the United Kingdom, and the United States; good in Spain, but less satisfactory in Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands. Despite these variations, the scale demonstrated overall validity and reliability across diverse cultural contexts.

The IFDFW Scale has been widely applied in research across disciplines, particularly in psychology and health, to examine associations between financial well-being and outcomes like mental health (20–22) and quality of life (23). It is valued for being time-efficient, easy to administer, and adaptable to diverse populations and settings. A recent systematic review (24) highlighted the IFDFW among the top financial well-being instruments based on its robust psychometric properties. Its strong internal consistency and structural validity have been consistently supported in multiple studies (2, 17, 19). Validating the IFDFW Scale in Arabic within the Lebanese context is particularly important given the severity of financial stress in this region. Between 2012 and 2022, the proportion of individuals living below the poverty line in Lebanon rose from 12 to 44% (25). Inflation reached a historic high of 221.3% in 2023 (26), and the Lebanese pound has lost over 98% of its value since 2019 (27), making it one of the world’s weakest currencies. These conditions have intensified financial strain and its psychological consequences. Despite the scale’s frequent use in Lebanese studies (28–32), no comprehensive psychometric validation of the IFDFW has been conducted in Arabic. Addressing this research gap is essential to ensure the scale’s conceptual equivalence, cultural relevance, and measurement accuracy in Arabic-speaking populations.

In addition to validating the Arabic version of the IFDFW, the second objective of this study was to develop and validate a single-item measure of financial stress, which we named the Single-Item Financial Stress Scale (SIFiS). Single-item self-report tools offer significant practical advantages: they are brief, easy to administer and cost-effective. Such measures are particularly valuable in large-scale field research or time-constrained environments, where reducing participant burden and overall study expenses is essential. Beyond their practicality, single-item scales have shown good validity and reliability and are increasingly recognized in recent guidelines (33, 34).

Single-item tools have already been successfully used in various psychological and health domains, including job satisfaction (35), social identity (36), and financial toxicity (37). Likewise, they have been applied in financial well-being studies. A US-based study on homeowners (38) used a single question to assess financial satisfaction, and an Australian study (39) conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic followed a similar approach. An Italian investigation (40) on emerging adults employed single-item measures to assess both financial well-being and stress. For this study, we adapted item 8 from the IFDFW Scale, which measures general financial stress, as the basis for the SIFiS. This choice is supported by the Italian study (40), which demonstrated that daily objective financial stress—unlike daily objective financial well-being—significantly impacts both subjective financial well-being and subjective financial stress. This is due to negativity bias (41, 42), whereby economic losses weigh more heavily on perceptions than economic gains. Moreover, the Italian study (40) emphasized that the choice between measures of financial stress and financial satisfaction should be context-specific. Given Lebanon’s prolonged economic crisis and the mental health focus of this study, we prioritized financial stress as a more appropriate and sensitive marker. The most comparable precedent to our SIFiS is a US college study (43), where participants were asked “How stressed do you feel about your personal finances?” and responded using a 10-point scale. By validating a similar single-item measure in Arabic, we aim to fill a key research gap in the availability of brief, culturally adapted tools to assess financial stress in Arabic-speaking populations.

Therefore, the aim of this study was two-fold: (1) to translate and validate the Arabic version of the IFDFW Scale within a sample of Arabic-speaking Lebanese adults, and (2) to develop and test the psychometric properties of a single-item scale measuring financial stress (i.e., the SIFiS). We hypothesized that the Arabic version of the IFDFW scale would demonstrate: (1) strong internal consistency, (2) a well-fitting factor structure, (3) measurement invariance across sex, and (4) convergent validity, evidenced by correlations between the IFDFW score and depression, anxiety, and stress scores. We also anticipated that the SIFiS would demonstrate similar psychometric patterns, supporting its utility as a brief measure of financial stress.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted between September and October 2021 using an anonymous online questionnaire created on Google Forms and disseminated to a sample of Lebanese adults from across the country. Eligible participants were Lebanese citizens aged 18 or older who gave consent to participate. Participants were recruited via snowball sampling through online platforms and social media applications. Prior to participation, the survey’s objectives and general instructions were clearly explained.

The survey was prepared in Arabic and consisted of three sections. The first section consisted of an online consent checkpoint to ensure voluntary participation, and attention to ethical concerns, such as confidentiality and anonymity of responses. This section also provided an introduction to the study and instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. The second section collected sociodemographic information, such as sex, age and socioeconomic status (SES); the latter was assessed through the household crowding index (HCI), calculated by dividing the number of persons by that of the rooms in the house without the kitchen and bathrooms (44). In the third section, validated measures were introduced, as outlined in the following details.

Measures

Incharge’s financial distress/financial well-being scale

This scale was designed to measure a person’s sense of security or distress regarding their financial situation (2). It consists of 8 items rated on a scale from 1 to 10. A higher score indicates lower perceived pressure and an improved state of personal financial wellness. Written permission for its use has been obtained from the original authors. The current Cronbach’s alpha is 0.95.

The single-item financial stress scale

Item 8 of the IFDFW was selected and analyzed separately as a potential standalone measure for assessing financial stress. The item is worded as follows: “How stressed do you feel about your personal finances in general?” (2). Responses are rated on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (“Overwhelming Stress”) to 10 (“No Stress at All”).

Lebanese anxiety scale (LAS-10)

This 10-item instrument (45) was specifically developed to assess symptoms of anxiety within a Lebanese setting. The first seven questions are rated from 1 to 10, and the last three questions are based on the frequency of symptom manifestation, rated from 1 to 4. Higher total scores indicate higher anxiety. The current Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.89.

Beirut distress scale (BDS-10)

This scale was developed and validated in the Lebanese context using a 10-item questionnaire measuring psychological distress (46). The response format is a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always), where higher scores reflect greater psychological distress. The current Cronbach’s alpha is 0.90.

Patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9)

This scale is among the most widely used and validated tools for assessing depression (47). It is a 9-item self-administered questionnaire, already validated in Lebanon (48). Each item is rated from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”). Higher scores indicate greater levels of depression. The current Cronbach’s alpha is 0.90.

Translation procedure

Forward and backward translations were performed to achieve a valid Arabic translation of the IFDFW. First, an independent Lebanese translator translated the English version of the IFDFW into Arabic. Then, a Lebanese academic with proficiency in both languages back-translated the Arabic version into English. A bilingual expert panel—composed of the research team and two professional translators—carefully reviewed and compared the original and back-translated English versions to evaluate both conceptual and linguistic accuracy. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus to ensure equivalence. Finally, the clarity and comprehensibility of the items were assessed in a pilot study with 30 participants, which confirmed that no further modifications were necessary.

Minimal sample size calculation

We calculated a minimum sample size of 160 participants, following the guideline of 20 participants per item in the scale (49).

Analytic strategy

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using SPSS AMOS, version 28. Parameter estimation was based on the maximum likelihood method. Several fit indices were calculated: the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.08), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR ≤ 0.05), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI; both ≥ 0.90) (50). For convergent validity, the average extracted variance (AVE) was considered for which the threshold value is ≥ 0.50 (51). Since multivariate normality was not supported at the beginning based on Bollen-Stine bootstrap p = 0.002, non-parametric bootstrapping approach was conducted.

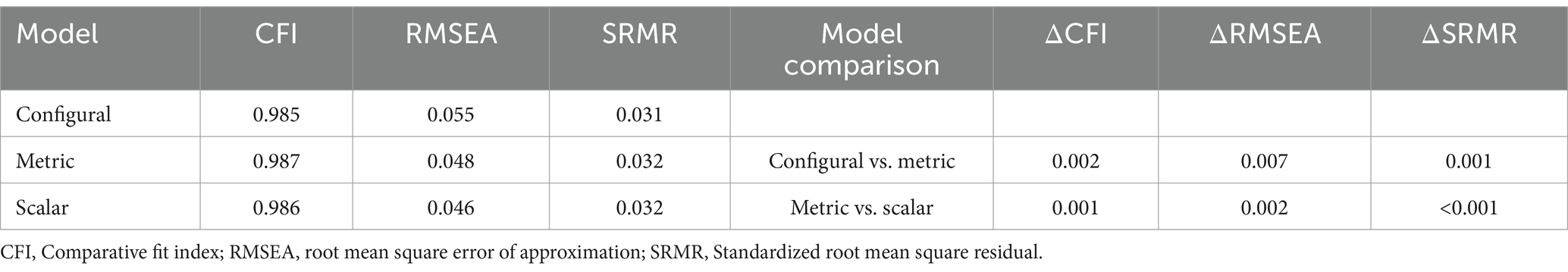

Measurement invariance across gender of the IFDFW scores was tested through multi-group CFA (52), at configural, metric and scalar invariance levels (53). Evidence of invariance was supported when ΔCFI ≤ 0.010 and ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015 or ΔSRMR ≤ 0.010 (52, 54). Comparisons of IFDFW and SIFiS scores across sexes were tested using the Student t-test.

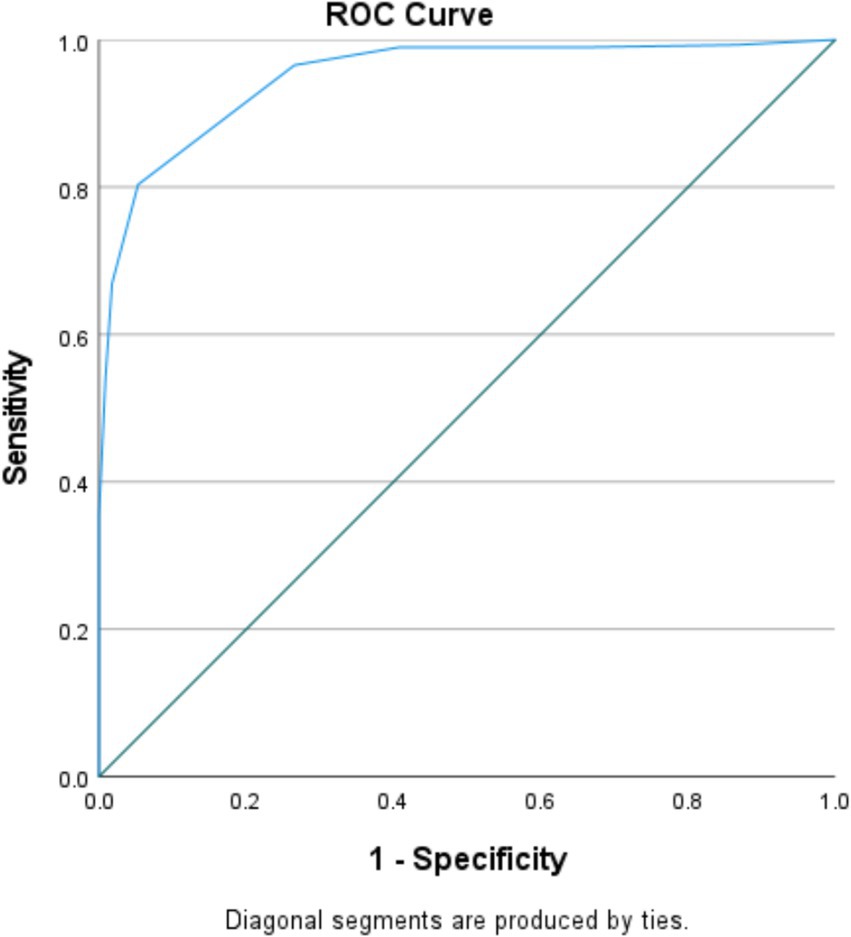

SPSS v.27 software was used to conduct the remaining analysis. Composite reliability was determined using McDonald’s ω and Cronbach’s α, with >0.70 being considered acceptable reliability (55, 56). Skewness and kurtosis values between −1 and +1 indicated that SIFis scores were normally distributed (57). Associations between IFDFW and SIFiS scores and other variables were evaluated using the Pearson correlation test. We conducted a Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis to confirm the suitability of the SIFiS as a standalone measure, by dichotomizing the total IFDFW score, using ≤ 40 as a threshold to define high financial stress cases. Criterion validity was evaluated via the calculation of the sensitivity and specificity values.

Results

Participants

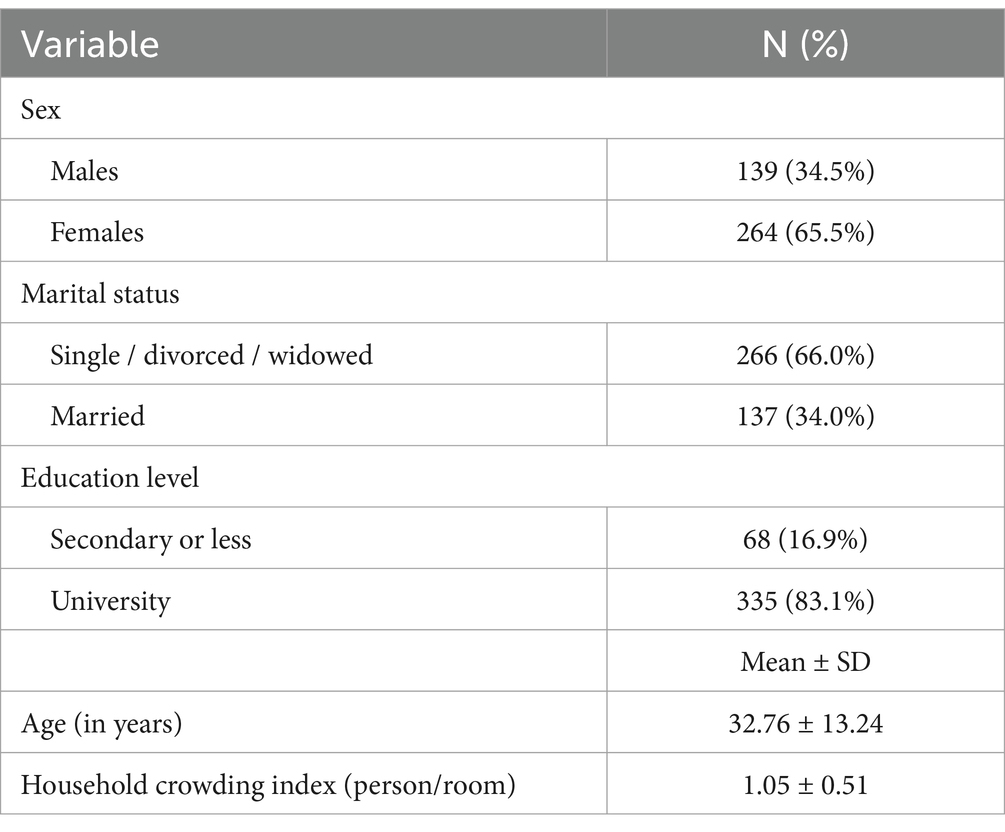

A total of 403 participants were enrolled in this study, with a mean age of 32.76 ± 13.24 years, and 65.5% were females. Additional demographic details are presented in Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis

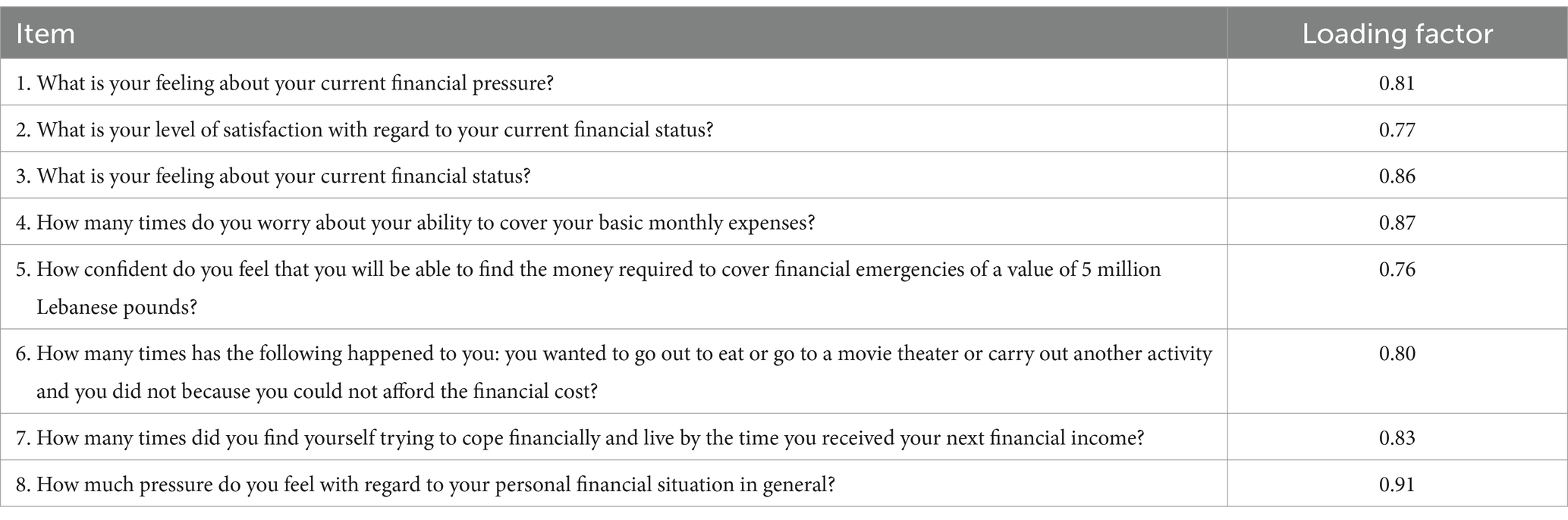

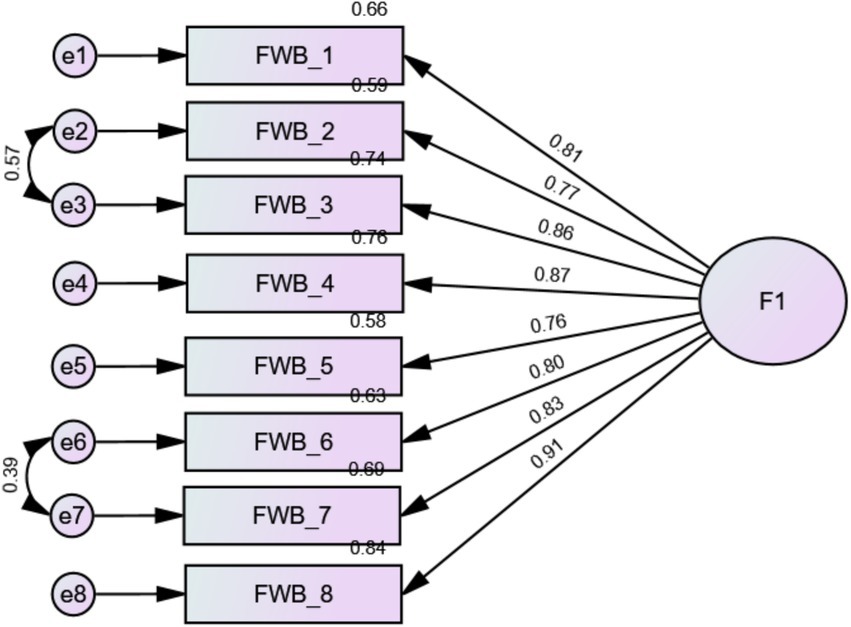

The fit indices were acceptable [RMSEA = 0.164 (90% CI 0.146, 0.183), SRMR = 0.039, CFI = 0.926, TLI = 0.897] but improved after adding correlations between items 2–3 and 6–7 due to high modification indices [RMSEA = 0.063 (90% CI 0.041, 0.085), SRMR = 0.020, CFI = 0.990, TLI = 0.985]. The Bollen-Stine bootstrap p-value of the final model was 0.106. All standardized factor loadings were adequate (Table 2; Figure 1). Internal reliability was excellent (ω = 0.95/α = 0.95).

Table 2. Standardized loading factors deriving from the confirmatory factor analysis of the incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale.

Figure 1. Standardized loading factors deriving from the confirmatory factor analysis of the incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale.

Gender invariance

Invariance was demonstrated at the metric and scalar levels in terms of genders (Table 3). A significantly lower mean IFDFW score was found in males compared to females (47.94 ± 18.98 vs. 52.33 ± 19.39; p = 0.030, Cohen’s d = 0.228). When considering IFDFW item 8, no significant difference was found between males and females in terms of financial wellbeing (6.01 ± 2.67 vs. 6.53 ± 2.66; p = 0.062, Cohen’s d = 0.196; Figure 2).

Table 3. Measurement invariance of the incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale across sex.

Figure 2. ROC curve of the single-item financial stress scale (SIFiS). Patients with high vs. low financial stress were analyzed (at a cutoff value of 40). Area under the curve of the SIFiS scale = 0.950 [0.929–0.971] (p < 0.001); at value = 4.50, Se = 96.6% and Sp = 73.5% and at value = 5.50, Se = 80.3% and Sp = 94.7%.

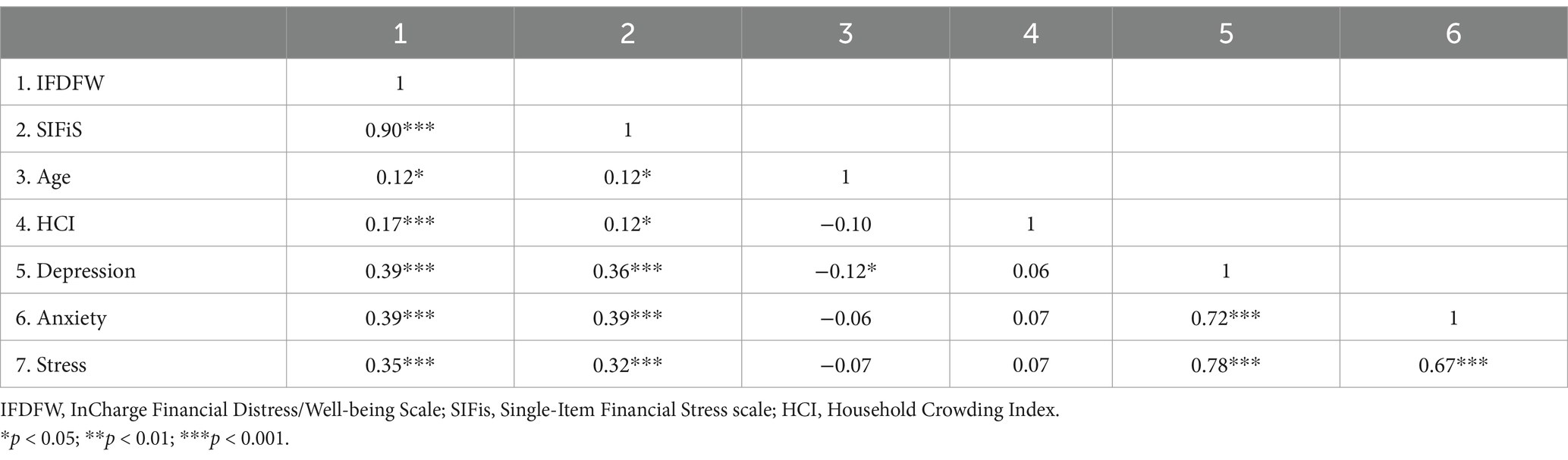

Concurrent validity

Higher IFDFW scores were significantly associated with higher depression (r = 0.39; p < 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.39; p < 0.001), distress (r = 0.35; p < 0.001), age (r = 0.12; p = 0.017) and HCI (r = 0.17; p < 0.001). In addition, higher scores on the SIFiS were significantly associated with depression (r = 0.36; p < 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.39; p < 0.001), distress (r = 0.32; p < 0.001), age (r = 0.12; p = 0.021) and HCI (r = 0.12; p = 0.017; Table 4).

ROC analysis of the SIFiS

The area under the curve (AUC) of the SIFiS was 0.950 [95% CI 0.929; 0.971] (p < 0.001). At a cutoff value of 4.50, sensitivity and specificity values were 0.966 and 0.735 respectively, whereas at a cutoff value of 5.50, they were 0.803 and 0.947, respectively.

Discussion

The validation of the Arabic versions of the IFDFW scale and the SIFiS marks a significant advancement in assessing personal financial well-being in Arabic-speaking countries. Our analysis demonstrated strong psychometric properties for both measures, along with satisfactory concurrent validity, underscoring their robustness and reliability for use in both research and applied settings.

The Arabic translation of the IFDFW scale demonstrated that it fits the one-factor structure, as was also found in other validations (2, 17–19). This means that the scale effectively measures a unified construct of financial well-being, encompassing major subjective aspects of financial stress and satisfaction. These findings suggest that the Arabic version preserves both the theoretical and empirical integrity of the scale, supporting its application among Arabic-speaking populations. Although Robert Nielsen’s research (58) proposed a two-factor model that separates subjective (feelings about financial condition) and objective (the ability to meet expenses) financial strain, such models have generally failed to demonstrate statistical superiority or clear theoretical justification. Notably, they have been limited by issues such as low eigenvalues for the “objective” factor and the inherently subjective nature of all items within the scale. Thus, the one-factor structure remains more parsimonious and empirically robust for representing financial well-being, as further supported by our Arabic validation. A notable observation was the close relationship between Item 2 and Item 3 on one hand, and Item 6 and 7 on the other. This likely stems from semantic overlap, as each pair addresses similar themes, making them appear nearly identical to respondents and resulting in strong inter-item correlations. One could also argue that this pattern echoes the two-factor model explored by Nielsen (58), which tentatively classifies Items 1, 2, 3, and 8 under subjective financial well-being, and Items 4, 5, 6, and 7 under objective financial well-being. Furthermore, a cross-national study involving seven countries (19) highlights the multidimensional nature of financial stress in the IFDFW scale, indicating that while all items assess subjective financial stress, they may also share additional internal commonalities not fully captured by a strict one-factor model. This multidimensionality introduces measurement-related variance into single-factor models. The authors therefore recommended modified one-factor models allowing correlated errors between items—an adjustment that improved model fit in their analyses and parallels the results of our own investigation.

The Arabic version of the IFDFW had an excellent internal consistency, with both Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients at 0.95. Although a Cronbach’s alpha in the range of 0.8 to 0.9 is generally considered ideal for a short-scale measure (59), a coefficient above this range further confirms the strong psychometric properties of the scale. For context, the original IFDFW construction paper reported an identical alpha coefficient of 0.95 (2), which was also observed in a subsequent US study (19). In a multi-country validation study, the German, Italian, Dutch, Slovenian, and Spanish versions reported alpha values of 0.92, 0.91, 0.91, 0.93, and 0.93, respectively (19). In comparison, the Brazilian Portuguese version reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (18). Such cross-cultural comparisons further underscore the high reliability of the Arabic version and suggest that future studies should explore potential cultural differences in the internal consistency of the scale.

Our findings indicate that men report relatively lower levels of financial well-being and, therefore, higher levels of distress than women. These results are inconsistent with previous research, where men generally demonstrate higher financial wellbeing than women, largely due to disparities in income and financial literacy (60–62). However, several contextual factors may explain the differences observed in our findings, particularly within the Lebanese setting.

First, men are more affected by unemployment and income losses during economic crises (63). Research suggests that men tend to equate financial well-being more directly with income, while women derive financial stability from financial behaviors and self-regulatory practices (64). Additionally, in most societies—including Lebanon—men bear the major responsibility for ensuring financial stability for their families, a societal expectation that increases their vulnerability to economic stress. This supports Gaunt and Benjamin’s findings (65), which show that traditional men experience higher job insecurity and greater levels of stress in response to financial challenges compared to traditional women, whose sense of identity is more strongly rooted in family roles and may thus be somewhat protected from economic strain.

These combined pressures, rooted in societal roles and compounded by Lebanon’s economic crisis, intensify the challenges faced by men in maintaining financial well-being.

Moreover, the SIFiS, as a single-item measure, showed no significant gender differences. This may indicate that it captures a broader, more generalized experience of financial stress, in which male and female perceptions do not significantly diverge. Alternatively, it may suggest that the SIFiS lacks the sensitivity and specificity needed to detect gender-based nuances in financial well-being influenced by cultural expectations or individual economic stressors. Further research is needed to deepen our understanding of gender differences as captured by both single-item and multi-item financial well-being measures.

Furthermore, our findings showed that higher levels of financial distress were associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress, supporting the concurrent validity of our study. This was demonstrated for both the total IFDFW and the SIFiS scores. Indeed, financial strain is widely recognized as one of the major predictors of mental health problems (66). A recent systematic review (13) summarized consistent evidence of the association between financial distress and adverse mental health outcomes, including heightened anxiety, depression, and stress, which may impair decision-making and reduce quality of life. This aligns with social causation theory (12, 67–69), which suggests that stressful financial circumstances, including inadequate living conditions, malnutrition, poor health behaviors, loss of social capital, and social isolation, can contribute to the onset of new depressive symptoms or prolong existing ones. Notably, subjective financial stressors appear to weigh more than the objective measures, as the latter influence depression indirectly through an individual’s perception of financial strain (12).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sample was skewed toward younger participants and females, and the use of snowball sampling may have introduced selection bias, limiting representativeness and generalizability of the findings. This method also tends to produce more homogeneous samples, as participants often recruit others from similar social circles, and it provides limited control over the recruitment process. Moreover, while the scale demonstrated strong internal consistency and structural validity, other psychometric properties were not assessed (such as test–retest reliability). Finally, this validation was conducted solely in Lebanon, underscoring the need for future studies in other Arabic-speaking populations to examine cross-cultural validity and further evaluate the scale’s psychometric properties.

Practical implications

The Arabic IFDFW Scale has the potential to become an effective tool in research, community-based programs, and healthcare settings due to its efficiency and speed in screening for financial distress. Policymakers can utilize the scale to design targeted interventions that address financial hardship, thereby enhancing mental health and economic resilience among vulnerable populations in Arabic-speaking regions. Its adoption could support data-driven social policies, resource allocation, and population-level monitoring efforts in the Arab world, especially in contexts affected by economic instability or humanitarian crises.

Additionally, the SIFiS offers a concise and practical means of assessing financial stress, especially in settings where time and resources are limited. It demonstrated strong concurrent validity, comparable to the IFDFW. Single-item measures like the SIFiS are best suited for specific contexts, as they may be more prone to bias. They are particularly valuable when financial stress is a confounding variable or when it is important to include financial assessments without overburdening respondents. Importantly, the SIFiS is not intended to replace comprehensive tools like the IFDFW, but rather to complement them—serving as an initial screening instrument that can guide the need for more in-depth evaluation. It is especially well-suited for large-scale deployment, where time, staffing, or logistical constraints limit the feasibility of administering longer instruments. Moreover, the SIFiS may serve as a rapid screening tool in public health, humanitarian, or economic support settings, where it can be quickly deployed in large-scale assessments or triage processes to identify individuals in need of immediate support or referral.

Future public health programs across the MENA region could integrate these tools into routine data collection or rapid needs assessments, providing culturally adapted measures for identifying at-risk populations and informing targeted interventions.

Conclusion

The Arabic version of both the IFDFW scale and the SIFiS demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, including high reliability and validity within our sample of Lebanese adults. The one-factor structure of the IFDFW supports theoretical expectations and aligns with previous validations in other languages, further confirming its value as a valid instrument for measuring financial well-being among Arabic-speaking populations. The adaptation of both measures opens the door for comparative cross-cultural studies that can deepen our understanding of how financial well-being influences societies, mental health, and quality of life worldwide.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Psychiatric Hospital of the Cross (HPC-040-2021). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

C-JZ: Writing – original draft. AC: Writing – original draft. RH: Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – review & editing. SK: Writing – review & editing. AN: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SO: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. FF-R: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Brüggen, EC, Hogreve, J, Holmlund, M, Kabadayi, S, and Löfgren, M. Financial well-being: a conceptualization and research agenda. J Bus Res. (2017) 79:228–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013

2. Prawitz, AD, Garman, ET, Sorhaindo, B, O’Neill, B, Kim, J, and Drentea, P. Incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. Financ Couns Plann. (2006) 17:34–50. doi: 10.1037/t60365-000

3. West, T, Cull, M, and Johnson, D. Income more important than financial literacy for improving wellbeing. FSR. (2021) 29:187–207. doi: 10.61190/fsr.v29i3.3456

4. Taft, MK, Hosein, ZZ, and Mehrizi, SMT. The relation between financial literacy, financial wellbeing and financial concerns. IJBM. (2013) 8:63. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v8n11p63

5. Buchler, S, Haynes, M, and Baxter, J. Casual employment in Australia: the influence of employment contract on financial well-being. J Sociol. (2009) 45:271–89. doi: 10.1177/1440783309335648

6. Gutter, M, and Copur, Z. Financial behaviors and financial well-being of college students: evidence from a national survey. J Fam Econ Iss. (2011) 32:699–714. doi: 10.1007/s10834-011-9255-2

7. Bai, R. Impact of financial literacy, mental budgeting and self control on financial wellbeing: mediating impact of investment decision making. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0294466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294466

8. Archuleta, KL, Dale, A, and Spann, SM. College students and financial distress: exploring debt, financial satisfaction, and financial anxiety. J Financ Couns Plan. (2013) 24:50–62.

9. Cappelli, T, Banks, AP, and Gardner, B. Understanding money-management behaviour and its potential determinants among undergraduate students: a scoping review. Kálmán BG, editor. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0307137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0307137

10. Friedline, T, Chen, Z, and Morrow, S. Families’ financial stress & well-being: the importance of the economy and economic environments. J Fam Econ Iss. (2021) 42:34–51. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09694-9

11. Weida, EB, Phojanakong, P, Patel, F, and Chilton, M. Financial health as a measurable social determinant of health. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0233359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233359

12. Guan, N, Guariglia, A, Moore, P, Xu, F, and Al-Janabi, H. Financial stress and depression in adults: a systematic review Magalhaes PVDS, editor. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0264041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264041

13. Hassan, MF, Mohd Hassan, N, Kassim, ES, and Utoh Said, YM. Financial wellbeing and mental health: a systematic review. eEarth. (2021) 39. doi: 10.25115/eea.v39i4.4590

14. Panos, GA, and Wilson, JOS. Financial literacy and responsible finance in the fin tech era: capabilities and challenges. Eur J Financ. (2020) 26:297–301. doi: 10.1080/1351847X.2020.1717569

15. Nanda, AP, and Banerjee, R. Consumer’s subjective financial well-being: a systematic review and research agenda. Int J Consum Stud. (2021) 45:750–76. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12668

16. Prawitz, AD, Garman, ET, Sorhaindo, B, O’Neill, B, Kim, J, and Drentea, P Incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale. Financial Counseling and Planning, (2006) 17:34–50.

17. Kamaluddin, MR, Nasir, R, Sulaiman, WSW, Hafidz, SWM, Abdullah, JM@NA, Khairudin, R, et al. Validity and reliability of Malay version financial well-being scale among Malaysian employees. Akademika. (2018) 88:109–20.

18. Carvalho, CDVSD, Kosminsky, M, Nascimento, MGD, and Lyra, AMVDC. Tradução e validação preliminar da “Incharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale” para o português brasileiro. RSD. (2021) 10:e40210713453. doi: 10.33448/rsd-v10i7.13453

19. Buabang, EK, Ashcroft-Jones, S, Esteban Serna, C, Kastelic, K, Kveder, J, Lambertus, A, et al. Validation and measurement invariance of the personal financial wellness scale: a multinational study in 7 countries. Eur J Psychol Assess. (2022) 38:476–86. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000750

20. Starkey, AJ, Keane, CR, Terry, MA, Marx, JH, and Ricci, EM. Financial distress and depressive symptoms among African American women: identifying financial priorities and needs and why it matters for mental health. J Urban Health. (2013) 90:83–100. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9755-x

21. Oswald, TK, Rumbold, AR, Kedzior, SGE, Kohler, M, and Moore, VM. Mental health of young Australians during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the roles of employment Precarity, screen time, and contact with nature. IJERPH. (2021) 18:5630. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115630

22. Meeker, CR, Geynisman, DM, Egleston, BL, Hall, MJ, Mechanic, KY, Bilusic, M, et al. Relationships among financial distress, emotional distress, and overall distress in insured patients with cancer. JOP. (2016) 12:e755. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.011049

23. Karam, J, Haddad, C, Sacre, H, Serhan, M, Salameh, P, and Jomaa, L. Financial wellbeing and quality of life among a sample of the Lebanese population: the mediating effect of food insecurity. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:906646. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.906646

24. de Oliveira Cardoso, N, Markus, J, de Lara Machado, W, and Guilherme, AA. Measuring financial well-being: a systematic review of psychometric instruments. J Happiness Stud. (2023) 24:2913–39. doi: 10.1007/s10902-023-00697-5

25. Bank W. Lebanon Poverty and Equity Assessment (2024). Weathering a protracted crisis. World Bank. Available online at: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099052224104516741/P1766511325da10a71ab6b1ae97816dd20c (Accessed December 13, 2024).

26. World Bank Open Data. World Bank Open Data. (2023). Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org (Accessed December 13, 2024).

27. World Bank. Lebanon: New World Bank Project to Restore Basic Fiscal Management Functions in Support of Public Service Delivery. (2024). Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/02/15/lebanon-new-world-bank-project-to-restore-basic-fiscal-management-functions-in-support-of-public-service-delivery (Accessed December 13, 2024).

28. Mhanna, M, El Zouki, CJ, Chahine, A, Obeid, S, and Hallit, S. Dissociative experiences among Lebanese university students: association with mental health issues, the economic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Beirut port explosion. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0277883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277883

29. El Zouki, CJ, Chahine, A, Mhanna, M, Obeid, S, and Hallit, S. Rate and correlates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following the Beirut blast and the economic crisis among Lebanese University students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:532. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04180-y

30. Younes, S, Hallit, S, Mohammed, I, El Khatib, S, Brytek-Matera, A, Eze, SC, et al. Moderating effect of work fatigue on the association between resilience and posttraumatic stress symptoms: a cross-sectional multi-country study among pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biopsychosoc Med. (2024) 18:4. doi: 10.1186/s13030-024-00300-0

31. Salameh, P, Hajj, A, Badro, DA, Abou Selwan, C, Aoun, R, and Sacre, H. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic and a collapsing economy: perspectives from a developing country. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 294:113520. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113520

32. Nasr, N, Swaidan, E, Karam, J, Haddad, C, and Nasr, R. Validation of the Arabic parental stress scale among Lebanese parents facing multiple crises. Discov Public Health. (2024) 21:89. doi: 10.1186/s12982-024-00220-y

33. Diamantopoulos, A, Sarstedt, M, Fuchs, C, Wilczynski, P, and Kaiser, S. Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: a predictive validity perspective. J Acad Mark Sci. (2012) 40:434–49. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3

34. Carifio, J, and Perla, RJ. Ten common misunderstandings, misconceptions, persistent myths and urban legends about Likert scales and Likert response formats and their antidotes. J Soc Sci. (2007) 3:106–16. doi: 10.3844/jssp.2007.106.116

35. Nagy, MS. Using a single-item approach to measure facet job satisfaction. J Occupat & Organ Psyc. (2002) 75:77–86. doi: 10.1348/096317902167658

36. Postmes, T, Haslam, SA, and Jans, L. A single-item measure of social identification: reliability, validity, and utility. Br J Soc Psychol. (2013) 52:597–617. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12006

37. Armache, M, Gharzai, LA, Mady, L, Sadigh, G, Sun, Z, Jagsi, R, et al. Correlation of a single-item measure of financial toxicity with overall score. JCO Oncol Pract. (2024) 20:351–1. doi: 10.1200/OP.2024.20.10_suppl.351

38. Manturuk, K, Riley, S, and Ratcliffe, J. Perception vs. reality: the relationship between low-income homeownership, perceived financial stress, and financial hardship. Soc Sci Res. (2012) 41:276–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.11.006

39. Botha, F, Butterworth, P, and Wilkins, R. Protecting mental health during periods of financial stress: evidence from the Australian coronavirus supplement income support payment. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 306:115158. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115158

40. Sorgente, A, Zambelli, M, and Lanz, M. Are financial well-being and financial stress the same construct? Insights from an intensive longitudinal study. Soc Indic Res. (2023) 169:553–73. doi: 10.1007/s11205-023-03171-0

41. Kahneman, D, and Tversky, A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. (1979) 47:263.

42. Baumeister, RF, Bratslavsky, E, Finkenauer, C, and Vohs, KD. Bad is stronger than good. Rev Gen Psychol. (2001) 5:323–70. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

43. Britt, SL, Canale, A, Fernatt, F, Stutz, K, and Tibbetts, R. Financial stress and financial counseling: helping college students. J Financ Couns Plan. (2015) 26:172–86. doi: 10.1891/1052-3073.26.2.172

44. Melki, IS. Household crowding index: a correlate of socioeconomic status and inter-pregnancy spacing in an urban setting. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2004) 58:476–80. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.012690

45. Hallit, S, Obeid, S, Haddad, C, Hallit, R, Akel, M, Haddad, G, et al. Construction of the Lebanese anxiety scale (LAS-10): a new scale to assess anxiety in adult patients. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. (2020) 24:270–7. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2020.1744662

46. Malaeb, D, Farchakh, Y, Haddad, C, Sacre, H, Obeid, S, Hallit, S, et al. Validation of the Beirut distress scale (BDS-10), a short version of BDS-22, to assess psychological distress among the Lebanese population. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2022) 58:304–13. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12787

47. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, and Williams, JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

48. Sawaya, H, Atoui, M, Hamadeh, A, Zeinoun, P, and Nahas, Z. Adaptation and initial validation of the patient health questionnaire −9 (PHQ-9) and the generalized anxiety disorder −7 questionnaire (GAD-7) in an Arabic speaking Lebanese psychiatric outpatient sample. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 239:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.030

49. Mundfrom, DJ, Shaw, DG, and Ke, TL. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. Int J Test. (2005) 5:159–68. doi: 10.1207/s15327574ijt0502_4

50. Hu, L, and Bentler, PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. (1999) 6:1–55.

51. Malhotra, NK. Marketing research: An applied orientation. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall (2010). 897 p.

52. Chen, FF. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model. (2007) 14:464–504. doi: 10.1080/10705510701301834

53. Vandenberg, RJ, and Lance, CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ Res Methods. (2000) 3:4–70. doi: 10.1177/109442810031002

54. Cheung, GW, and Rensvold, RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model. (2002) 9:233–55. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

55. Dunn, TJ, Baguley, T, and Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol. (2014) 105:399–412. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12046

56. McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychol Methods. (2018) 23:412–33. doi: 10.1037/met0000144

57. Hair, JF. Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Second ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE (2024). 236 p.

58. Nielsen, RB. Assessing financial wellness via computer-assisted telephone interviews. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network (2010).

59. Morgado, FFR, Meireles, JFF, Neves, CM, Amaral, ACS, and Ferreira, MEC. Scale development: ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicol Refl Crít. (2018) 30:3. doi: 10.1186/s41155-016-0057-1

60. Falahati, L, and Fazli Sabri, M. An exploratory study of personal financial wellbeing determinants: examining the moderating effect of gender. Assessment. (2015) 11:33. doi: 10.5539/ass.v11n4p33

61. Bağci, H, and Kahraman, YE. The effect of gender on financial literacy. Finans Ekonomi ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi. (2020); Available online at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/doi/10.29106/fesa.615866 (Accessed December 13, 2024).

62. Gerrans, P, Speelman, C, and Campitelli, G. The relationship between personal financial wellness and financial wellbeing: a structural equation modelling approach. J Fam Econ Iss. (2014) 35:145–60. doi: 10.1007/s10834-013-9358-z

63. Périvier, H. Men and women during the economic crisis: employment trends in eight European countries. Rev OFCE. (2014) 133:41–84.

64. Zyphur, MJ, Li, WD, Zhang, Z, Arvey, RD, and Barsky, AP. Income, personality, and subjective financial well-being: the role of gender in their genetic and environmental relationships. Front Psychol. (2015) 6:1493. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01493/abstract

65. Gaunt, R, and Benjamin, O. Job insecurity, stress and gender: the moderating role of gender ideology. Community Work Fam. (2007) 10:341–55. doi: 10.1080/13668800701456336

66. Selenko, E, and Batinic, B. Beyond debt. A moderator analysis of the relationship between perceived financial strain and mental health. Soc Sci Med. (2011) 73:1725–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.022

67. Lund, C. Poverty and mental health: a review of practice and policies. Neuropsychiatry. (2012) 2:213–9. doi: 10.2217/npy.12.24

68. Lund, C, and Cois, A. Simultaneous social causation and social drift: longitudinal analysis of depression and poverty in South Africa. J Affect Disord. (2018) 229:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.050

Keywords: incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale, financial stress, Arabic, factor analysis, validation

Citation: El Zouki C-J, Chahine A, Hallit R, Malaeb D, El Khatib S, Nehme A, Obeid S, Fekih-Romdhane F and Hallit S (2025) Arabic validation of the incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale and the new single-item financial stress scale. Front. Public Health. 13:1570404. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1570404

Edited by:

Xiaozhen Lai, Peking University, ChinaReviewed by:

Gesti Memarista, Widya Mandala Catholic University Surabaya, IndonesiaRamona Nasr, Modern University for Business and Science, Lebanon

Copyright © 2025 El Zouki, Chahine, Hallit, Malaeb, El Khatib, Nehme, Obeid, Fekih-Romdhane and Hallit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feten Fekih-Romdhane, ZmV0ZW4uZmVraWhAZ21haWwuY29t; Souheil Hallit, c291aGVpbGhhbGxpdEB1c2VrLmVkdS5sYg==; Diana Malaeb, ZHIuZGlhbmFAZ211LmFjLmFl

†These authors share last authorship

Christian-Joseph El Zouki1

Christian-Joseph El Zouki1 Abdallah Chahine

Abdallah Chahine Rabih Hallit

Rabih Hallit Diana Malaeb

Diana Malaeb Sami El Khatib

Sami El Khatib Sahar Obeid

Sahar Obeid Feten Fekih-Romdhane

Feten Fekih-Romdhane Souheil Hallit

Souheil Hallit