- 1Chestnut Health Systems, Bloomington, IL, United States

- 2ServeMinnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, United States

- 4Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, RI, United States

- 5Rhode Island Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals, Cranston, RI, United States

- 6Center on Drugs and Addiction Research, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

- 7Recovery Research Institute, Center of Addiction Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 8Partnership to End Addiction, New York, NY, United States

- 9The Phoenix, Boston, MA, United States

- 10East Tennessee State University, Addiction Science Center, College of Public Health, Johnson City, TN, United States

- 11University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States

- 12Department of Community & Family Medicine, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, United States

- 13The Dartmouth Institute of Health Policy, Giesel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, United States

- 14The Dartmouth Institute of Health Policy & Clinical Practice, Giesel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College, Lebanon, PA, United States

- 15Department of Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States

This narrative review explores the evolving role of linkage facilitation (LF) in supporting persons with opioid use disorder (OUD) including both the organizational strategies to initiate and sustain LF services and strategies to support the LF workforce. Drawing on expert consensus and iterative review by an interdisciplinary author team, we synthesized relevant literature from diverse fields using a narrative review approach. Organizational strategies include: ensure leadership support, engage community partners and tailor services, consult with those already delivering LF services, provide adequate pay and career advancement opportunities, establish role clarification, and create official documentation of LF services. Strategies to support the LF workforce include: ensure comprehensive training and continuing education, provide robust supervision, encourage self-care, and establish quality/fidelity standards. Recommendations for advancing the profession include enhancing training for both LFs and supervisors, establishing centralized resource libraries, and tailoring support for diverse OUD-affected populations. This review advocates for the development of best practice guidelines, practical evaluation tools, and a collaborative resource-sharing hub to ensure long-term LF workforce sustainability and improved outcomes for those served.

1 Introduction

This narrative review examines the research and practice literature pertaining to supporting people delivering linkage facilitation (LF) for persons with opioid use disorder (OUD). Opioid misuse remains a national healthcare problem, with alarming rates of OUD and lethal opioid overdoses across demographic groups (1, 2). LF—also called service linkage or linkage to care—encompasses a range of services to help people access appropriate treatment, harm reduction, and support interventions, maintain medication and treatment adherence, and obtain resources that assist immediate and long-term recovery goals (3). LF may be especially helpful to persons looking to start medications for the treatment of OUD (MOUD) given the considerable barriers to treatment access and initiation (4). LF for MOUD service uptake is employed in various settings including primary care, emergency departments, behavioral health, perinatal care, the criminal legal system, and harm reduction facilities (3). Recent empirical reviews suggest LF can foster MOUD initiation and adherence, promoting access to and engagement in other supportive behavioral and social services (5–7).

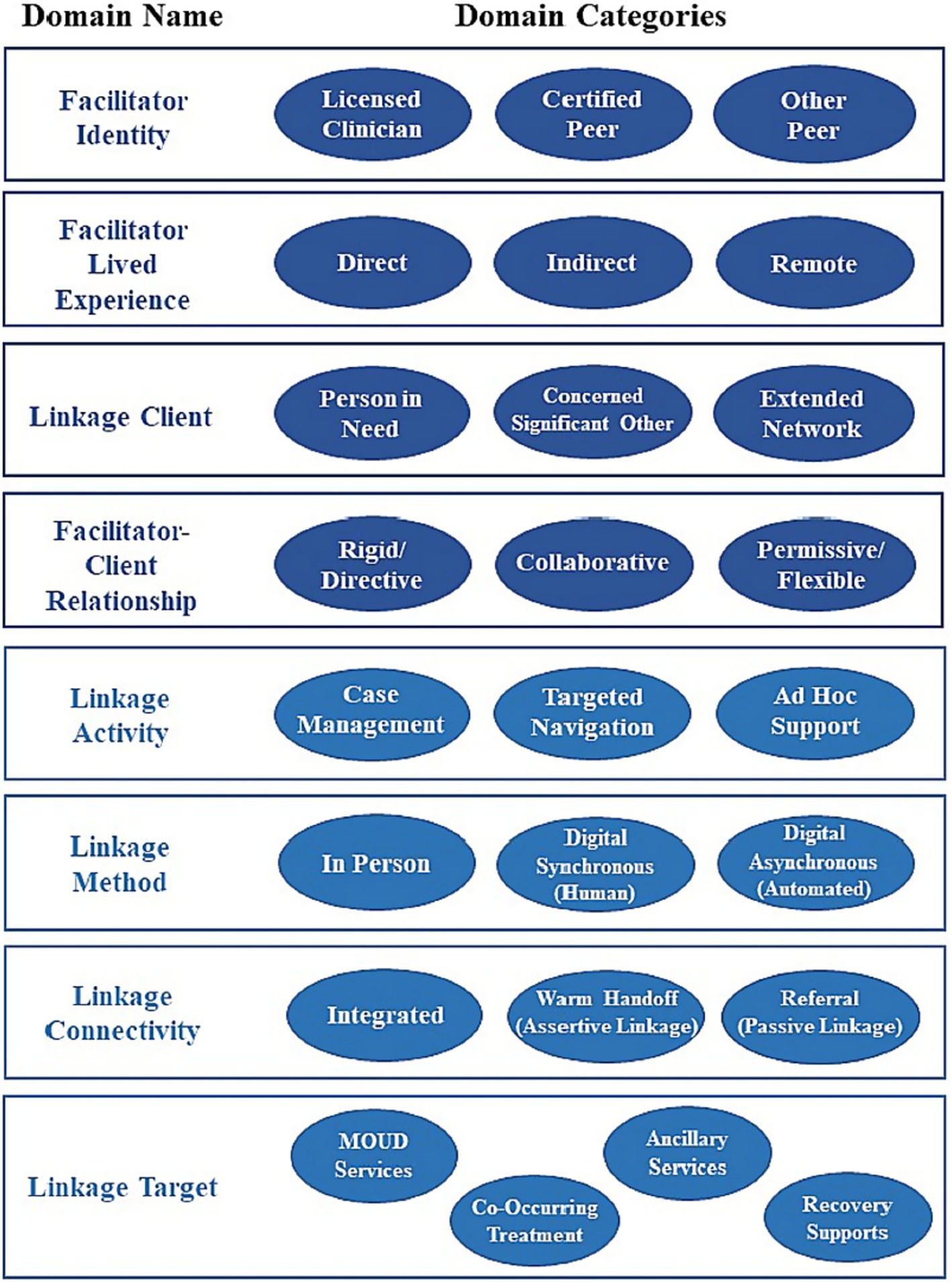

LF can be delivered by an array of practitioners, aims to achieve a host of linkage goals, and consists of multifaceted linkage activities. To promote consistent communication about standards and practices, Hogue et al. (8) describe a taxonomy of LF services for persons with OUD that contains eight dimensions (see Figure 1): facilitator identity; facilitator lived experience; linkage client; facilitator-client relationship; linkage activity; linkage method; linkage connectivity; and linkage goal.

Figure 1. Taxonomy of linkage facilitation for OUD services from Hogue et al. (8).

LF for people with OUD is becoming increasingly commonplace (3), and the LF workforce is becoming larger and more diverse. As such, linkage facilitators represent various professions including social workers, nurses, case managers, health navigators, community health workers (CHW), and peer recovery support specialists (PRSS). Therefore, workforce retention must consider such factors as facilitator professional identity, potential experience with substance misuse and recovery, and contextual factors within the workplace (9).

Linkage facilitators face multiple challenges in deploying their services, including others’ stigma toward clients (and, at times, toward facilitators with lived experience of recovery), inadequate supervision, role ambiguity, and a lack of integration within healthcare teams (10–12). These issues, compounded by the scarcity of resources to connect individuals with OUD to appropriate services, often lead to burnout and turnover, particularly among professionals like health navigators, CHWs, and PRSS (13–15). Additionally, poor integration into healthcare teams and being assigned duties beyond their scope further contribute to role dissatisfaction (16–20). Linkage facilitators also face financial instability due to inadequate compensation and limited career advancement opportunities, which can create financial fragility and increase turnover rates (19, 21). Combined with stressors such as vicarious trauma and unsupportive work environments, these factors heighten vulnerability to stress and burnout (19, 22). Addressing these challenges is essential to ensuring this vital workforce is supported and retained. Building upon the critical need for supporting linkage facilitators outlined in the introduction, this paper now details the systematic approach taken to review the existing literature and identify key strategies for their sustained effectiveness.

2 Methods

We conducted this review as a collaboration among researchers associated with two large initiatives supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Consortium on Addiction Recovery Science (CoARS) and the Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (JCOIN). We determined a narrative review as the most appropriate approach because of the nascent state of empirical literature spread across various disciplines that is directly related to LF practice for persons with OUD that would be necessary to conduct a systematic review (23–26). Although narrative reviews are sometimes critiqued for lacking rigor, it is important to recognize their strength in providing extensive coverage of literature and flexibility to emerging knowledge and concepts (27). A key outcome of narrative reviews is a more in-depth understanding of the topic of focus (28).

All review authors are highly engaged practitioners and researchers in the area of LF services and this review drew primarily on their knowledge of the disparate LF literature. We met approximately monthly via Zoom and conversed through frequent email correspondence over 12 months to prioritize the review goals, identify critical themes in the field, assign specific subtopic writing responsibilities, and review and co-edit through an iterative revision process. After all authors agreed on an outline through consensus and selected subtopics to complete initial drafts based on interest and expertise, authors identified articles through online searches in research literature databases and using their expertise and knowledge related to specific content areas within the review’s aim. In drafting the review, we were guided by Ferrari (29) to select articles that include linkage facilitation services as described in Hogue et al. (8). Authors within subtopics worked together to select appropriate references. After the initial draft all authors reviewed the paper in its entirety, suggesting additional references as appropriate. While all authors revised and approved the final manuscript, the first and second author were responsible for the final review of the text and selection of the literature supporting the key recommendations. While narrative reviews are subjective, as is all research, they add meaningful contributions to the literature (30). Having established the methodology employed in this narrative review, we now present the findings, categorizing them into key strategies for organizational support and workforce development that emerged from the literature.

3 Results

We first discuss approaches for supporting linkage facilitators working with persons with OUD and end with how the field can advance quickly to support this rapidly growing workforce. Due to the current state of the literature on LF to MOUD and our expertise in this area, many of our examples are framed from the perspective of professionals, such as PRSS and CHWs. To better understand how the field can support and grow the LF workforce, we first examine organizational-level strategies that facilitate the successful initiation, implementation, and sustainment of LF services for individuals with OUD.

3.1 Organizational strategies to initiate and sustain LF services

Organizational strategies to support initiation and sustainment of LF services for those working with persons with OUD include leadership engagement, flexible work environments (31), learning collaboratives, external facilitation, didactic webinars (32, 33), and full-time employment (34). Similarly, enablers of adoption and delivery include government-supported programs that create LF positions within organizations (31), strategic plans for employing linkage facilitators (35), and Executive Orders assigning linkage facilitators to primary care sites (36). Work with PRSS linkage facilitators has shown that these workers may not become integral to services if stakeholders are unwilling to integrate them into existing practice (11). A systematic review suggests incorporating linkage facilitators into systems is enhanced by linkage facilitators having a peer network and organizational resources (e.g., internet access), preparing staff through training (e.g., how to interact with linkage facilitators) and role clarification, and attending to staff attitudes towards linkage facilitators (11). This is particularly important given that lack of role clarity has been found to lead to feelings of exclusion, tokenism, and stigmatization among PRSS linkage facilitators within another review (37). Implementing and maintaining LF services for working with persons with OUD requires comprehensive strategies that address organizational needs and overcome barriers.

3.1.1 Ensure organizational leadership support

The literature indicates commitment of organizational leadership as vital to supporting linkage facilitator activities (11) and is especially germane when clarifying the need, importance, and practices of linkage facilitators and initiating policy changes to support them (38). Early evidence points toward transparent backing from organizational leadership as an essential element for fostering the integration of LF services by openly advocating for their adoption within the organization, and securing formal endorsement from leadership and their active involvement in decision-making processes as a critical factor for garnering organizational support (39, 40). For example, such support may be critical for creating pathways to employing LFs with lived experience and for reaching patients with disproportionately high risk of limited access to MOUD (e.g., during incarceration) and fatal overdose (e.g., upon reentry) (41). While lived experience enhances the impact of linkage facilitation, LFs with misdemeanor or felony histories may be unemployable without changing an organization’s hiring policies (124). Likewise, leader-to-leader advocacy may be needed to establish cross-system policies and agreements to allow PRSS or other LFs with lived experience to contact clients during incarceration or community supervision (125, 126).

3.1.2 Engage community partners and tailor services

Once there is support from organizational leadership regarding LF service provision, involving key community partners (e.g., representatives from organizations to which linkage is being facilitated to, staff and team leaders, as well as consumers who have received or may benefit from LF services), in the design and implementation of those LF services fosters buy-in and encourages collaboration. Customizing LF services to align with requirements of the organization looking to deliver LF services, such as defining tasks, schedules, and workflows, is instrumental in achieving successful integration (42). As this can vary greatly from setting to setting, particularly given the range of treatment options and LF locations for those working with persons with OUD, involving community partners can be essential for successful LF program implementation and linkage facilitator integration within the organization and community. Further, engaging community partners can expand the available resource network for an organization, thereby reducing concerns associated with resources shortages with clients.

3.1.3 Consult with those already delivering LF services for people with OUD

Organizations who want to provide LF services to people with OUD should decide if the LF services will be a stand-alone role or if the services will be added to an existing role, as well as whether LF services occur internally or in collaboration with an outside agency. Financial considerations, along with considering adding burden to systems that may already be operating at maximum capacity, as well as decisions of each domain of the LF taxonomy [see Figure 1 (8)], ought to guide organizations. To manage these multiple decision points, utilizing outside LF organizations or consultants (e.g., community and lived-experience advisory boards) can assist agencies in LF program development by collaborating on developing policies, training programs, and standards to support facilitator integration. These initiatives should focus on the strategies highlighted above including defining roles, procedures, boundaries, and resource allocation to ensure successful implementation (40, 43). Ideally, consultants will include individuals who have LF experience. Additionally, for programs looking to create LF programs to assist persons with OUD, hiring and working with consultants that have expertise working with that specific focus would be exemplary.

3.1.4 Provide adequate pay and career advancement opportunities

While many linkage facilitators are generally satisfied with their work, common areas of dissatisfaction include low pay and limited opportunities for advancement (19, 44). Higher pay for such workers has been positively associated with job satisfaction, therefore it is imperative that organizational support includes adequate pay and benefits and opportunities for career advancement for linkage facilitators. Research on mental health peer workers suggests that these same factors contribute to workers leaving the field to pursue other careers (13) and similar dynamics may be present among SUD peer workers (45).

Medicaid billing and reimbursement processes can be overly complicated and pay for only selected services (46). Thus, the evidence suggests it is important for agencies that provide LF services to be proactive and intentional about fiscal sustainability for these cost-effective services (47) and the LF workforce. Linkage facilitators often work in positions that cannot financially support them long-term as one residential treatment administrator explains, “… we are asking these people to impact our communities for the better yet we are not giving them a wage that can support a life or raising a family” (48). Setting specific role clarification and ongoing documentation of LF outcomes can lead to a more equitable and sustainable career pathway for the LF workforce.

3.1.5 Establish role clarification

Linkage facilitators often operate in environments where their roles and responsibilities may be poorly defined (37) which can result in a variety of challenges in providing services (49), such as other staff members not understanding the linkage facilitator role, questioning linkage facilitator credibility, and devaluing LF services (20). Additionally, a clash in philosophies between a medical model, where an expert knows best, versus experiential knowledge and client self-determination may preclude integration of some linkage facilitators within systems (38). The need for clarity in roles and responsibilities has been indicated as an essential factor influencing effective implementation into existing systems (40, 50). Preparing staff for the introduction of new LF roles can help with integration. Clarification can be accomplished in part via staff training so that linkage facilitators and other staff have a common understanding of purpose, roles, and activities of linkage facilitators (51, 52).

3.1.6 Create official documentation of LF services

As LF services are being established, it is important to formalize the commitment to initiate and maintain LF services through written policies and procedures, which ensure clarity and accountability. Official documentation also helps to define and formalize facilitator roles that can guide them in their work. Developing comprehensive documents that outline decisions, policies, and procedures in collaboration with leadership facilitates transparency and consistency (40, 43), helping to support both the services being provided and the linkage facilitator workforce.

3.2 Strategies to support the linkage facilitation workforce

While establishing robust organizational strategies is fundamental for the successful implementation of LF services, equally crucial are direct approaches aimed at nurturing and sustaining the individual linkage facilitation workforce. In this section, we highlight several strategies that would be beneficial for supporting linkage facilitators to improve workforce retention and other outcomes. Many of the strategies presented are also approaches to supporting LF service implementation more broadly (53), as well-implemented programs should result in more supportive work environments for linkage facilitators.

3.2.1 Ensure comprehensive training and continuing education

Training for linkage facilitators varies by organization and is often tailored to facilitator identity, lived experience, client needs, and available resources (8). Many linkage facilitators come from professions such as licensed clinicians, certified PRSS, or CHWs, each with state-specific training standards. Coordination with credentialing bodies may ensure consistency in basic knowledge and training requirements. Specific to working with persons with OUD, training should address MOUD, opioid withdrawal, harm reduction strategies, available community resources, and the intersecting risks and systems (e.g., criminal legal systems, child welfare systems) that impact care access, continuity, and outcomes. Linkage facilitators work within a client-centered framework, meaning they support clients without imposing change, using techniques like motivational interviewing to meet clients where they are in the behavior change process (54, 55). Training that includes specific treatment models or work settings, such as primary care, can further ensure linkage facilitators are prepared for success (56). Additionally, experienced linkage facilitators should have a key role in developing and revising training programs, as recommended in PRSS standards (57). It is important to recognize that in some settings, access to training and certification represents barriers to becoming a linkage facilitator and can further exacerbate health inequities that already exist at a systemic level (58). Scholarships (as noted below) may in part offset such barriers but will likely not eliminate them. Systems must be mindful of such inequities and how best to address them for a skilled, diverse, and representative workforce.

Ethical considerations are also vital in LF training. Most LF professions have established codes of ethics, such as NAADAC’s (Association for Addiction Professionals) guidelines, that can provide a foundation for those lacking ethics training in their specific field (59). Linkage facilitators should be able to identify fraud and abuse within referral organizations and recognize ethical dilemmas within their own organizations, such as being pressured to make internal referrals that may not benefit clients (60). Additionally, they should be aware of their own biases regarding recovery pathways, including MOUD and harm reduction (61). Younger linkage facilitators with lived experience may face unique challenges in setting boundaries, which can increase stress and require additional support (62, 63). Ethical training is essential for maintaining professional boundaries, avoiding burnout, and empowering clients rather than fostering dependency.

Training should also prepare LFs to navigate ethical and legal challenges specific to subpopulations with OUD. For example, pregnant and postpartum patients face elevated risks of medicalized stigma, criminalization, and loss of parental rights (127, 128). Some states even require automatic report of child abuse when prescribed MOUD is taken during pregnancy (129). LFs supporting this population need clear guidance on their jurisdiction’s reporting requirements—and a strong understanding of their limits—to ensure they protect patients’ privacy rights to the fullest extent allowed by law.

Additionally, continuing education (CE) is a crucial component of ongoing support for linkage facilitators and has been emphasized for over a decade within the PRSS workforce (64). CE requirements vary by state (65), but SAMHSA (57) recommends annual CE on ethical standards, with provisions for offsetting costs, such as scholarships. CE should also cover recent research in mental health, trauma, MOUD, and unique considerations for serving subpopulations while providing opportunities for mentoring, skill development, and peer learning (64). A program support team should oversee the development and delivery of CE (64). Additionally, several studies indicate that regular CE helps linkage facilitators integrate more effectively into healthcare settings, enhancing their legitimacy and reducing their experience of stigma and discrimination (38, 40, 66). Certification and ongoing professional development can clarify LF roles within teams, improving job satisfaction and workforce retention.

3.2.2 Provide robust supervision

Ongoing supervision and debriefing are crucial for the successful implementation of linkage facilitators, particularly for those working with individuals with OUD (11, 67). However, literature suggests that LF supervisors may not provide adequate support, either due to insufficient supervision or lack of knowledge and skills (12, 52, 68). Despite these challenges, regular supervision remains essential to addressing issues like burnout and promoting job satisfaction and success among linkage facilitators (22, 31, 69). Adequate supervision may also promote linkage facilitator resiliency in the face of work-related stressors (22, 46). Young linkage facilitators working with youth may encounter difficulties, for example, in role clarification and boundaries; however, provision of supervision, particularly emotionally supportive supervision can enhance success (70, 71). Supervisors who are responsive, flexible, and encourage autonomy can reduce professional isolation, help establish role clarity and signal the value of linkage facilitators within their organizations, especially when adopting trauma-informed approaches that account for the lived experiences of linkage facilitators (15, 72). Feeling respected and supported by supervisors enhances job satisfaction (73), and regular, constructive feedback is recommended to sustain effective supervision, supported by organizational policy and financial resources (74). Various guidelines, including those from SAMHSA and the National Association of Peer Supporters (NAPS), provide frameworks for effective LF supervision (75–77). Supervisors should also model self-care and boundary-setting, support personal and professional growth, and have knowledge of local OUD services and harm reduction strategies (76, 78).

Supervision should also account for the varied types of lived experience among linkage facilitators, which range from direct, indirect, and remote lived experiences (8). Direct lived experience can positively impact professional roles but may also result in stigma, especially when disclosed (12, 79–83). Indirect and remote lived experiences present different challenges that require tailored supervisory support to help linkage facilitators navigate their roles and client relationships. Supervisors with direct lived experience can offer unique integration and role clarity benefits for linkage facilitators who share similar backgrounds (12, 84).

3.2.3 Encourage self-care

As most linkage facilitators working with persons with OUD support high-acuity populations, many while maintaining their own recovery, their work can be challenging (85). Indeed, a unique aspect of LF is that workers can be chosen specifically for their lived experience, with potentially relapsing conditions, and yet ironically self-care (including taking time off) to manage conditions is recognized by some linkage facilitators as jeopardizing employment (12).

Research with PRSS linkage facilitators has identified that self-care routines are important to mitigating burnout and improving resiliency against chronic work stressors (86, 87), findings which likely have broad applicability to others in linkage facilitator roles. Self-care can be promoted through professional development opportunities (e.g., trainings) and funding structures (46), as well as organizational policies promoting flexible scheduling and mental/emotional support. Self-care is enhanced by a sense of community, self-awareness (e.g., of triggers), boundaries between work and home, and ongoing training and supervision (12, 88). For example, for LGBTQ+ linkage facilitators, self-care is supported when organizations build partnerships with affirming providers, ensure access to evidence-based, gender-affirming care, and recruit staff with relevant lived experience and cultural competence (89, 90). However, it should be noted that the assumption that linkage facilitators are particularly vulnerable to stress is largely untested (87). Finally, while employee-level self-care practices are essential, workplaces must avoid precluding them. Supervisors and organizations working with linkage facilitators should be educated on the occupational hazards of the linkage facilitator role (e.g., vicarious trauma, burnout) and adopt a trauma stewardship approach [i.e., policies and practices that prioritize the well-being, resilience, and sustainable self-care of employees in psychologically hazardous roles (91)].

Of note, particularly for linkage facilitators with direct lived experience, a potential point of conflict exists if the resources that a linkage facilitator uses to support their own recovery as part of their self-care routine overlaps with the resources that the client is using (92). This potential underexplored challenge may exist more in areas with limited resources, such as rural areas, and has not been sufficiently studied to date. Organizations supporting linkage facilitators should have ways to address this challenge, including comprehensive supervision as noted above and provide the infrastructure and support to access other forms of support, such as attending online support groups that could be located outside of the local recovery support network.

3.2.4 Establish quality/fidelity standards

Establishment of quality standards for LF would help define processes and expected outcomes for the field that could help linkage facilitators better clarify their role within their organization and their identities as related to the LF profession. A good place to start establishing such standards is through the identification of LF fidelity guidelines. The most important dimensions of fidelity have been defined as adherence (the specific content or quantity of interventions delivered) and competence [the technical skill or quality of delivery (93)]. Fidelity includes knowledge of client issues, intervention appropriateness and timing, and degree of responsiveness to client behaviors (94, 95). Formalizing LF fidelity standards will require detailed descriptions of development activities beyond what is captured in the current LF literature [(e.g., 96–98)]. More rigorous evaluation of LF fidelity tools and procedures in clinical settings is needed to support consistent, high-quality LF delivery that conforms to the procedures and goals of LF models over time. Three principles should govern LF fidelity advances. First, tools and procedures used to evaluate fidelity should reflect the multiple domains that constitute LF for OUD [(8); see Figure 1] and the core tasks of the specific LF model (99). For example, one of the authors (REDACTED) developed a fidelity tool for an intervention in which PRSS linkage facilitators collaboratively link adults with OUD to recovery support services. Because the facilitator-client relationship is deemed “Collaborative” by tool developers, the tool includes coding criteria regarding the facilitator’s consideration of patients’ desires/concerns, while supporting the goal of service linkage. Second, behavioral protocols should articulate procedures for training and monitoring practitioners in how to use companion fidelity tools. Well-established methods for successful practitioner training [e.g., behavioral rehearsal with active feedback, ongoing expert consultation (100)] should be repurposed for fidelity training to support the LF workforce. Third, LF fidelity methods need to be pragmatic, that is, practitioner-friendly, compatible and integrated with routine services, minimize missing data, and facilitate user-reactivity tracking (101). Note there are documented advantages and burdens associated with each of the primary fidelity evaluation methods: independent-observer or supervisor report, practitioner or client self-report, and case record review (102).

Creating quality fidelity guidelines can then support providing feedback to linkage facilitators and lead to continuous improvement in services. Performance feedback and evaluation play pivotal roles supporting linkage facilitators by improving implementation and maintenance of LF services. By setting up regular feedback mechanisms, organizations can effectively monitor progress, pinpoint challenges, and adapt as needed. Consistent evaluation of LF services, encompassing tasks such as monitoring daily activities and evaluating their effectiveness, is fundamental for ensuring their long-term sustainability (50).

4 Discussion: promising avenues for advancing the profession of linkage facilitation for OUD

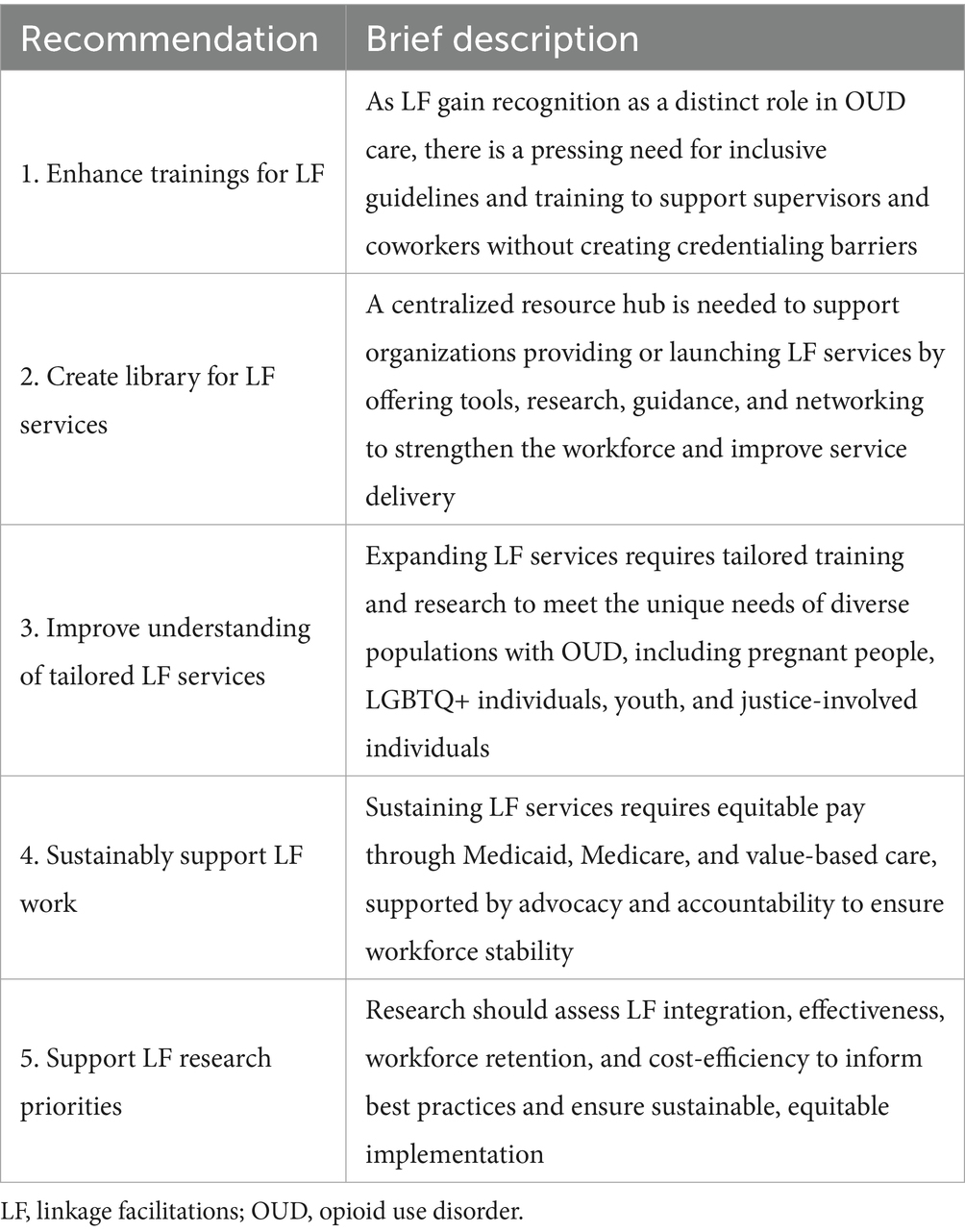

Drawing from the comprehensive findings on effective strategies for supporting linkage facilitators, this discussion synthesizes these insights and outlines promising future directions for advancing the profession of linkage facilitation for opioid use disorder. The successful initiation and sustainability of LF services require a multifaceted approach that involves professional development and growth opportunities, external facilitation, leadership support, stakeholder engagement, feedback mechanisms, and documentation. This rapidly maturing field can build upon these components as it prepares the future LF workforce and the settings in which they are called upon to contribute their skills to support individuals with OUD. Below, we offer some recommendations for facilitating that progress in the coming years (see Table 1).

4.1 Enhance training guides for linkage facilitators, and critically, for supervisors of linkage facilitators and other staff working at agencies with LF programs

Only recently has the position of “linkage facilitator” been acknowledged as a unique and independent role for professionals serving individuals with OUD (8, 41). The LF field would benefit from cross-cutting guidelines that could serve as best practices. However, such guidelines must be developed to not conflict with the standards of the wide swath of professional backgrounds from which linkage facilitators may originate (e.g., certified PRSS, CHW, licensed clinicians). Given the current shortage in the behavioral health workforce, standards should avoid creating unnecessary barriers for professionals to work as linkage facilitators, such as requiring higher-level certifications or licenses for LF roles. Perhaps more urgently, however, there is a need for development of trainings and resources for both supervisors and coworkers of those performing LF for people with OUD. Robust, responsive, and compassionate supervision has been identified as a critical aspect of supporting successful linkage facilitators (11, 67, 74, 77). Furthermore, research has documented challenges arising from other agency staff, including stigma, philosophical clashes, and lack of role clarity (37, 38, 61). Leadership within each organization delivering LF would be well-positioned to equip supervisors and coworkers with resources and knowledge to respect and support linkage facilitators, but development of training guides would facilitate this process much more effectively. To translate these insights into actionable strategies, we organize the discussion around five key areas where targeted investment, research, and infrastructure can advance the field of linkage facilitation for OUD.

4.2 Develop an accessible resource library for organizations providing LF or interested in initiating LF services

While the expansion and synthesis of trainings materials is an important initial step in supporting the growing LF workforce, dissemination of these and other LF-related resources is urgently needed. We recommend that the field invest in a centralized resource-sharing hub where organizations who offer LF for persons with OUD, or are interested in initiating LF services, can access up-to-date information and relevant tools. For example, organizations considering hiring linkage facilitators may wish to read about recent research findings, particularly service delivery models, that could aid in development of an approach tailored to their program (and which, backed by evidence, may be more compelling for leadership, stakeholders, and funding agencies). Those organizations that offer LF could benefit from access to tools for measurement of fidelity, examples of official documentation (e.g., standard operating procedures), or recommendations for career advancement that would support the LF workforce, but which may be underutilized. Guidance on how organizations can address hiring restrictions based on lived experience (e.g., history of incarceration, drug offenses) would also be helpful. Additionally, this type of central hub would allow for networking between linkage facilitators, organizations providing LF services, researchers, and others interested in LF who may hope to connect or consult with practitioners and other experts. Although initiation of this type of resource center would be an investment of time, energy, and resources, it would pay dividends towards supporting the future LF workforce—both specifically related to OUD services and more broadly.

4.3 Improve understanding of populations who may require uniquely tailored LF services in addition to support related to OUD

As the need for LF services for people with OUD continues to grow, and the LF workforce expands to meet it, the diversity of individuals with OUD becomes an increasingly important consideration for linkage facilitator training and education. For example, pregnant and postpartum people may require linkage to specialized medical services and assistance navigating disparate systems (e.g., child welfare, social agencies). Individuals with OUD and criminal legal system (CLS) involvement can experience difficulty accessing employment or safe/supportive housing and may face stigma, discouragement, or denial from CLS staff related to some types of OUD treatment, particularly MOUD (41). LGBTQ+ individuals may experience mistreatment within health settings, leaving them underserved and isolated from quality health care (103–105), which could be a key opportunity for linkage facilitators to engage in knowledge translation and advocacy.

Furthermore, youth and emerging adults with OUD represent a unique demographic with rising rates of overdose (106), yet LF for this population—including defining who is best-positioned to provide LF services—remains understudied. There is a distinct need for research related to LF for these and other unique populations of individuals with OUD to better understand best practices for advocacy, communication, and tailored service needs. Additionally, given that some LF models include linkage facilitators with direct lived experience (e.g., PRSS), work is direly needed to expand understanding and develop recommendations for supervisors and organizations employing linkage facilitators who themselves identify as members of these populations. This will more fully support the LF workforce to provide quality tailored services to diverse individuals with OUD who may have unique needs related to their identities and circumstances.

4.4 Find ways to sustainably support LF work

Sustainably supporting LF services will require payment structures that prioritize equitable compensation, as financial instability and inadequate pay contribute to high turnover in this essential workforce (19, 21). Better aligning compensation models with Medicaid, Medicare, and value-based care models presents a solution, recognizing the importance of linkage facilitators in improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare costs. While Medicare has integrated care billing mechanisms that could support LF services, they are rarely utilized (107, 108). Medicaid varies from state to state, but growing trends in covering peer and CHW services [(e.g., 109)] provide a potential route to supporting LF (77, 110). Value-based care can support linkage facilitators by aligning financial incentives with patient outcomes, ensuring that the essential work of linkage facilitators in connecting individuals with care is recognized and adequately compensated, while also improving healthcare efficiency and patient recovery outcomes through integrated care models (111, 112). Ensuring payment structures are available and equitable across the nation will likely require coordinated advocacy (107, 113). Additionally, accountability structures (e.g., the proposed central LF workforce hub in section 4.2) may need to be instituted to ensure that organizations equitably reflect the provisions of such payment structures in their linkage facilitators’ compensation. This combination of equitable pay and policy reform is essential for maintaining a stable LF workforce, thereby enhancing care continuity and promoting long-term recovery for individuals with OUD.

4.5 Research priorities

Studies are needed that examine the general integration of LF services for OUD across different contexts and with diverse populations. Observational research can help map how LF is implemented across various healthcare, community, and legal settings. Such research can compare existing LF models to identify best practices, challenges, and potential service delivery gaps (8, 114). Moreover, the diversity of linkage facilitator backgrounds (e.g., peers, CHWs, licensed clinicians) requires comparative research on how different types of LF professionals function within these settings and with varying patient populations.

Clinical trials aimed at identifying the effectiveness of specified OUD LF interventions would help optimize the impact of LF on both individual and system-level outcomes. Such trials should prioritize identifying the causal mechanisms of effectiveness—whether through increasing treatment engagement, reducing relapse rates, or promoting long-term recovery (114). This type of research is crucial to optimizing the impact of LF on both individual and system-level outcomes. Hybrid studies that are also focused on implementation can develop fidelity standards and identify best strategies for LF implementation, leading to more rapid research translation (115). This will also ensure consistency in delivering LF services, thereby enhancing the reliability of the research and the quality of care provided in real-world settings.

There is a need for research focused on LF workforce outcomes and the identification of factors that prevent linkage facilitator burnout and support retention. Given the high turnover rates in the behavioral health workforce, it is essential to explore the protective factors that can enhance job satisfaction, reduce stress, and promote long-term workforce stability (116). Research informed by existing occupational health theories, such as the Job Demands-Resources model (117) or the Conservation of Resources theory (118), could offer valuable frameworks for understanding how to balance the demands placed on LF workers with the resources available to them. This line of research should examine factors such as workload, role clarity, access to professional development, and support from colleagues, all of which can play a role in either mitigating or exacerbating burnout. Within this broader focus, understanding effective leadership and supervision models is particularly important. Leadership approaches that foster a positive, supportive work environment, promote autonomy, and provide trauma-informed supervision are likely to enhance job satisfaction and retention. Research that explores how different leadership and supervisory styles impact burnout, job satisfaction, and overall workforce retention will be essential to optimizing LF service delivery and ensuring a sustainable, resilient workforce (72, 119, 120).

Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses of LF models will help quantify both the direct and indirect financial impacts of these interventions. By establishing the costs associated with implementing LF, as well as the long-term savings generated through improved patient outcomes—such as reductions in hospitalizations, relapses, and criminal legal involvement—these evaluations can provide a strong case for integrating LF services into reimbursement structures (121, 122). Importantly, economic evaluations can also inform equitable pay for linkage facilitators by showing the economic value of their contributions to the healthcare system and patient recovery to inform development of fair compensation models, reducing workforce turnover and contributing to workforce sustainability.

4.5.1 Strengths and limitations

This narrative review offers a timely synthesis of the fragmented literature on linkage facilitation for individuals with OUD, providing practical insights for workforce development and organizational support. A key strength lies in the interdisciplinary expertise of the authorship team, which allowed for integrative insights drawn from practice and various research methods across the field (24), behavioral health, and community-based systems. However, the review is limited by the subjective nature of narrative synthesis and the absence of a systematic search protocol, which may have introduced selection bias (123). Additionally, the current evidence base on LF and OUD practices remains nascent, with limited high-quality, empirical studies directly examining workforce experiences, intervention effectiveness, or implementation strategies. Future research should prioritize rigorous, longitudinal, and implementation-focused studies to build a more robust evidence base and inform scalable models for supporting this emerging workforce (8, 114).

Author contributions

TD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC-L: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AMH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article was supported by funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (K23DA048161 [PI: Drazdowski], R34DA057639 [PI: Drazdowski], K01DA055768 [PI: Hoffman], R24DA051950 [MPIs: Sheidow & McCart], R24DA051973 [MPIS: Stack & Horn], R24DA051946-01S1 [PI: Hogue], R24DA057632 [PI: Zajac], U01DA050442 [PI:Martin], UG1DA050069 [PI: Staton], UG1DA050065 [MPIs: Dennisa & Grella], L30DA056979 [PI: Satcher], R25DA037190 [PI: Bekwith], R25DA035163 [PI: Masson & St Helen], UG1DA050077-04 [MPIs: Gordon & Mitchell]; the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (T32AA018108 [PI: Witkiewitz]), and the Health Resources and Services Administration (T32HP32520 [PI: Brunette]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NIH and other funders.

Acknowledgments

We would firstly like to thank Dr. Shannon Gwin Mitchell for her assistance in conceptualizing, writing, and reviewing the paper. Additionally, we would also like to thank Ms. Danielle Weedman, and Ms. Emily Rains for their assistance with the references, formatting and editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Blavatnik Institute for Health Care Policy . Evidence based strategies for abatement of harms from the opioid epidemic. Boston, MA: Harvard Medical School (2020).

2. Townsend, T, Kline, D, Rivera-Aguirre, A, Bunting, AM, Mauro, PM, Marshall, BD, et al. Racial/ethnic and geographic trends in combined stimulant/opioid overdoses, 2007–2019. Am J Epidemiol. (2022) 191:599–612. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab290

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2022). Linking people with opioid use disorder to medication treatment: a technical package of policy, programs, and practices. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/media/pdfs/OD2A_EvalProfile_LinkageToCareInitiatives_508.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

4. Crotty, K, Freedman, KI, and Kampman, KM. Executive summary of the focused update of the ASAM national practice guideline for the treatment of opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. (2020) 14:99–112. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000635

5. Chan, B, Gean, E, Arkhipova-Jenkins, I, Gilbert, J, Hilgart, J, Fiordalisi, C, et al. Retention strategies for medications for opioid use disorder in adults: a rapid evidence review. J Addict Med. (2021) 15:74–84. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000739

6. Grella, CE, Ostlie, E, Watson, DP, Scott, CK, Carnevale, J, and Dennis, ML. Scoping review of interventions to link individuals to substance use services at discharge from jail. J Subst Abus Treat. (2022) 138:108718. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108718

7. Lagisetty, P, Klasa, K, Bush, C, Heisler, M, Chopra, V, and Bohnert, A. Primary care models for treating opioid use disorders: what actually works? A systematic review. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0186315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186315

8. Hogue, A, Satcher, MF, Drazdowski, TK, Hagaman, A, Hibbard, PF, Sheidow, AJ, et al. Linkage facilitation services for opioid use disorder: taxonomy of facilitation practitioners, goals, and activities. J Subst Use Addict Treat. (2024) 157:209217. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209217

9. Hogue, A, Bobek, M, Porter, N, Dauber, S, Southam-Gerow, MA, McLeod, BD, et al. Core elements of family therapy for adolescent behavioral health problems: validity generalization in community settings. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2023) 52:490–502. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2021.1969939

10. Bassuk, EL, Hanson, J, Greene, RN, Richard, M, and Laudet, A. Peer-delivered recovery support services for addictions in the United States: a systematic review. J Subst Abus Treat. (2016) 63:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.003

11. Ibrahim, N, Thompson, D, Nixdorf, R, Kalha, J, Mpango, R, Moran, G, et al. A systematic review of influences on implementation of peer support work for adults with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2020) 55:285–93. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01739-1

12. Tate, MC, Roy, A, Pinchinat, M, Lund, E, Fox, JB, Cottrill, S, et al. Impact of being a peer recovery specialist on work and personal life: implications for training and supervision. Community Ment Health J. (2022) 58:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s10597-021-00811-y

13. Jones, N, Kosyluk, K, Gius, B, Wolf, J, and Rosen, C. Investigating the mobility of the peer specialist workforce in the United States: findings from a national survey. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2020) 43:179–88. doi: 10.1037/prj0000395

14. Smithwick, J, Nance, J, Covington-Kolb, S, Rodriguez, A, and Young, M. “Community health workers bring value and deserve to be valued too:” key considerations in improving CHW career advancement opportunities. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1036481. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1036481

15. Stefancic, A, Bochicchio, L, Tuda, D, Harris, Y, DeSomma, K, and Cabassa, LJ. Strategies and lessons learned for supporting and supervising peer specialists. Psychiatr Serv. (2021) 72:606–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000515

16. Almeida, M, Day, A, Smith, B, Bianco, C, and Fortuna, K. Actionable items to address challenges incorporating peer support specialists within an integrated mental health and substance use disorder system: co-designed qualitative study. J Particip Med. (2020) 12:e17053. doi: 10.2196/17053

17. Gaiser, MG, Buche, JL, Wayment, CC, Schoebel, V, Smith, JE, Chapman, SA, et al. A systematic review of the roles and contributions of peer providers in the behavioral health workforce. Am J Prev Med. (2021) 61:e203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.03.025

18. Garfield, C, and Kangovi, S. Integrating community health workers into health care teams without coopting them. Health Aff Forefront. (2019). doi: 10.1377/forefront.20190507.746358

19. Hagaman, A, Foster, K, Kidd, M, and Pack, R. An examination of peer recovery support specialist work roles and activities within the recovery ecosystems of central Appalachia. Addict Res Theory. (2023) 31:328–34. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2022.2163387

20. Scannell, C . Voices of hope: substance use peer support in a system of care. Subst Abuse. (2021) 15:11782218211050360. doi: 10.1177/11782218211050360

21. Schmit, CD, Washburn, DJ, LaFleur, M, Martinez, D, Thompson, E, and Callaghan, T. Community health worker sustainability: funding, payment, and reimbursement laws in the United States. Public Health Rep. (2022) 137:597–603. doi: 10.1177/00333549211006072

22. Abraham, KM, Erickson, PS, Sata, MJ, and Lewis, SB. Job satisfaction and burnout among peer support specialists: the contributions of supervisory mentorship, recovery-oriented workplaces, and role clarity. Adv Ment Health. (2022) 20:38–50. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2021.1977667

23. Munn, Z, Stern, C, Aromataris, E, Lockwood, C, and Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2018) 18:5. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

24. Siddaway, AP, Wood, AM, and Hedges, LV. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. (2019) 70:747–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

25. Smith, SA, and Duncan, AA. Systematic and scoping reviews: a comparison and overview. Semin Vasc Surg. (2022) 35:464–9. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2022.09.001

26. Snyder, H . Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. (2019) 104:333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

27. Byrne, JA . Improving the peer review of narrative literature reviews. Res Integr Peer Rev. (2016) 1:12. doi: 10.1186/s41073-016-0019-2

28. Greenhalgh, T, Thorne, S, and Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur J Clin Investig. (2018) 48:e12931. doi: 10.1111/eci.12931

29. Ferrari, R . Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med Write. (2015) 24:230–5. doi: 10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

30. Sukhera, J . Narrative reviews: flexible, rigorous, and practical. J Grad Med Educ. (2022) 14:414–7. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-22-00480.1

31. Mutschler, C, Bellamy, C, Davidson, L, Lichtenstein, S, and Kidd, S. Implementation of peer support in mental health services: a systematic review of the literature. Psychol Serv. (2022) 19:360–74. doi: 10.1037/ser0000531

32. Cheng, H, McGovern, MP, Garneau, HC, Hurley, B, Fisher, T, Copeland, M, et al. Expanding access to medications for opioid use disorder in primary care clinics: an evaluation of common implementation strategies and outcomes. Implement Sci Commun. (2022) 3:72. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00306-1

33. Louie, E, Barrett, EL, Baillie, A, Haber, P, and Morley, KC. A systematic review of evidence-based practice implementation in drug and alcohol settings: applying the consolidated framework for implementation research framework. Implement Sci. (2021) 16:22. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01090-7

34. Liebling, EJ, Perez, JJS, Litterer, MM, and Greene, C. Implementing hospital-based peer recovery support services for substance use disorder. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2021) 47:229–37. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2020.1841218

35. Gray, M, Davies, K, and Butcher, L. Finding the right connections: peer support within a community-based mental health service. Int J Soc Welfare. (2017) 26:188–96. doi: 10.1111/ijsw.12222

36. Shepardson, RL, Johnson, EM, Possemato, K, Arigo, D, and Funderburk, JS. Perceived barriers and facilitators to implementation of peer support in Veterans Health Administration Primary Care-Mental Health Integration settings. Psychol Serv. (2019) 16:433–44. doi: 10.1037/ser0000242

37. du Plessis, C, Whitaker, L, and Hurley, J. Peer support workers in substance abuse treatment services: a systematic review of the literature. J Subst Use. (2020) 25:225–30. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2019.1677794

38. Mirbahaeddin, E, and Chreim, S. A narrative review of factors influencing peer support role implementation in mental health systems: implications for research, policy, and practice. Admin Pol Ment Health. (2020) 49:596–612. doi: 10.1007/s10488-021-01186-8

39. Chinman, M, Shoai, R, and Cohen, A. Using organizational change strategies to guide peer support technician implementation in the veterans administration. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2010) 33:269–77. doi: 10.2975/33.4.2010.269.277

40. Mancini, MA . An exploration of factors that affect implementation of peer support services in community mental health settings. Community Ment Health J. (2018) 54:127–37. doi: 10.1007/s10597-017-0145-4

41. Satcher, MF, Belenko, S, Coetzer-Liversage, A, Wilson, KJ, McCart, MR, Drazdowski, TK, et al. Linkage facilitation for opioid use disorder in criminal legal system contexts: a primer for researchers, clinicians, and legal practitioners. Health Justice. (2024) 12:36. doi: 10.1186/s40352-024-00291-8

42. Kokorelias, KM, Shiers-Hanely, JE, Rios, J, Knoepfil, A, and Hitzig, SL. Factors influencing implementation of patient navigation programs for adults with complex needs: a scoping review of the literature. Health Serv Insights. (2021) 14:11786329211033267. doi: 10.1177/11786329211033267

43. Franke, CCD, Paton, BC, and Gassner, L-AJ. Implementing mental health peer support: a South Australian experience. Aust J Prim Health. (2010) 16:179–86. doi: 10.1071/PY09067

44. Mowbray, O, Campbell, RD, Disney, L, Lee, M, Fatehi, M, and Scheyett, A. Peer support provision and job satisfaction among certified peer specialists. Soc Work Ment Health. (2021) 19:126–40. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2021.1885090

45. Castedo de Martell, S, Wilkerson, JM, Howell, J, Brown, HS III, Ranjit, N, Holleran Steiker, L, et al. The peer to career pipeline: an observational study of peer worker trainee characteristics and training completion likelihood. J Subst Use Addict Treat. (2024) 159:209287. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209287

46. Stack, E, Hildebran, C, Leichtling, G, Waddell, EN, Leahy, JM, Martin, E, et al. Peer recovery support services across the continuum: in community, hospital, corrections, and treatment and recovery agency settings—a narrative review. J Addict Med. (2022) 16:93–100. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000810

47. Castedo de Martell, S, Moore, M, Wang, H, Holleran Steiker, L, Wilkerson, JM, Ranjit, N, et al. Cost-effectiveness of long-term post-treatment peer recovery support services in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2024) 51:180–90. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2024.2406251

48. Wallis, R, Signorelli, M, Linn, H, Bias, T, Allen, L, and Davis, SM. Lessons learned from employing Medicaid-funded peer recovery support specialists in residential substance use treatment settings: an exploratory analysis. J Subst Use Addict Treat. (2023) 154:209136. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209136

49. Weikel, K, Tomer, A, Davis, L, and Sieke, R. Recovery and self-efficacy of a newly trained certified peer specialist following supplemental weekly group supervision: a case-based time-series analysis. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2017) 20:1–15. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2016.1267051

50. Valaitis, RK, Carter, N, Lam, A, Nicholl, J, Feather, J, and Cleghorn, L. Implementation and maintenance of patient navigation programs: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17:116. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2046-1

51. Clossey, L, Solomon, P, Hu, C, Gillen, J, and Zinn, M. Predicting job satisfaction of mental health peer support workers (PSWs). Soc Work Ment Health. (2018) 16:682–95. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2018.1483463

52. Kemp, VB, and Henderson, AR. Challenges faced by mental health peer support workers: peer support from the peer supporter’s point of view. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2012) 35:337–40. doi: 10.2975/35.4.2012.337.340

53. Powell, BJ, Waltz, TJ, Chinman, MJ, Damschroder, LJ, Smith, JL, Matthieu, MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

54. Miller, WR, and Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change and grow. 4th ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2023).

55. Prochaska, JO, Wright, JA, and Velicer, WF. Evaluating theories of health behavior change: a hierarchy of criteria applied to the transtheoretical model. Appl Psychol. (2008) 57:561–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00345.x

56. Harris, RA, Campbell, K, Calderbank, T, Dooley, P, Aspero, H, Maginnis, J, et al. Integrating peer support services into primary care-based OUD treatment: lessons from the Penn integrated model. Healthcare. (2022) 10:100641. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2022.100641

57. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . (2023) SAMHSA’s national model standards for peer support certification (HHS Publication No. PEP23-10-01-001). Available online at: https://www.samhsa.gov/about-us/who-we-are/offices-centers/or/model-standards (Accessed February 11, 2025).

58. Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts . (2023). Supporting and building the peer recovery workforce: lessons from the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts 2023 survey of peer recovery coaches. Available online at: https://forefdn.org/supporting-and-building-the-peer-recovery-workforce-lessons-from-the-foundation-for-opioid-response-efforts-2023-survey-of-peer-recovery-coaches/ (Accessed February 11, 2025).

59. NAADAC, the Association for Addiction Professionals . (2021). NAADAC/NCC AP code of ethics. Available online at: https://www.naadac.org/assets/2416/naadac_code_of_ethics_112021.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

60. Rothenberg, Z . (2018). Trends in combating fraud and abuse in substance use disorder treatment. J Health Care Compliance, 20: 13–20. Available online at: https://www.nelsonhardiman.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/HCCJ_0910_18_Rothenberg.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

61. Pasman, E, Lee, G, Singer, S, Burson, N, Agius, E, and Resko, SM. Attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder among peer recovery specialists. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2024) 50:391–400. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2024.2332597

62. Chen, Y, Yuan, Y, and Reed, BG. Experiences of peer work in drug use service settings: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Int J Drug Policy. (2023) 120:104182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104182

63. Collier, C, Hilliker, R, and Onwuegbuzie, A. Alternative peer group: a model for youth recovery. J Groups Addict Recover. (2014) 9:40–53. doi: 10.1080/1556035X.2013.836899

64. Daniels, AS, Bergeson, S, Fricks, L, Ashenden, P, and Powell, I. Pillars of peer support: advancing the role of peer support specialists in promoting recovery. J Ment Health Train Educ Pract. (2012) 7:60–9. doi: 10.1108/17556221211236457

65. Anvari, MS, Kleinman, MB, Dean, D, Rose, AL, Bradley, VD, Hines, AC, et al. A pilot study of training peer recovery specialists in behavioral activation in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:3902. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20053902

66. Schleiff, M, Aitken, I, Alam, MA, Damtew, ZA, and Perry, HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new area: 6. Recruitment, training, and continuing education. Health Res Policy Syst. (2021) 19:113. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00757-3

67. Powell, KG, Treitler, P, Peterson, NA, Borys, S, and Hallcom, D. Promoting opioid overdose prevention and recovery: an exploratory study of an innovative intervention model to address opioid abuse. Int J Drug Policy. (2019) 64:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.12.004

68. Gillard, S, Gibson, SL, Holley, J, and Lucock, M. Developing a change model for peer worker interventions in mental health services: a qualitative research study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2015) 24:435–45. doi: 10.1017/S2045796014000407

69. Eisen, SV, Mueller, LN, Chang, BH, Resnick, SG, Schultz, MR, and Clark, JA. Mental health and quality of life among veterans employed as peer and vocational rehabilitation specialists. Psychiatr Serv. (2015) 66:381–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400105

70. Delman, J, and Klodnick, V. Factors supporting the employment of young adult peer providers. Community Ment Health J. (2017) 53:811–22. doi: 10.1007/s10597-016-0059-6

71. Tisdale, C, Snowdon, N, Allan, J, Hides, L, Williams, P, and de Andra, D. Youth mental health peer support work: a qualitative study exploring the impacts and challenges of operating in a peer support role. Adolescents. (2021) 1:400–11. doi: 10.3390/adolescents1040030

72. Forbes, J, Pratt, C, and Cronise, R. Experiences of peer support specialists supervised by nonpeer supervisors. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2022) 45:54–60. doi: 10.1037/prj0000475

73. Cronise, R, Teixeira, C, Rogers, ES, and Harrington, S. The peer support workforce: results of a national survey. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2016) 39:211–21. doi: 10.1037/prj0000222

74. Deussom, R, Mwarey, D, Bayu, M, Abdullah, SS, and Marcus, R. Systemic review of performance-enhancing health worker supervision. Hum Resour Health. (2022) 20:2. doi: 10.1186/s12960-021-00692-y

75. Daniels, AS, Tunner, TP, Powell, I, Fricks, L, and Ashenden, P. (2015). Pillars of peer support services summit six: peer specialist supervision. Available online at: https://peerrecoverynow.org/wp-content/uploads/Pillars-of-PeerSupport-2014.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

76. National Association of Peer Supporters (NAPS) . (2019). National practice guidelines for peer specialists and supervisors. Available online at: https://www.peersupportworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/National-Practice-Guidelines-for-Peer-Specialists-and-Supervisors-1.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

77. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . (2024). Financing peer recovery support: opportunities to enhance the substance use disorder peer workforce (HHS Publication No. PEP23-06-07-003). Available online at: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/financing-peer-recovery-report-pep23-06-07-003.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

78. Foglesong, D, Knowles, K, Cronise, R, Wolf, J, and Edwards, JP. National practice guidelines for peer support specialists and supervisors. Psychiatr Serv. (2022) 73:215–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000901

79. Dugdale, S, Elison, S, Davies, G, Ward, J, and Dalton, M. Using the transtheoretical model to explore the impact of peer mentoring on peer mentors’ own recovery from substance misuse. J Groups Addict Recovery. (2016) 11:166–81. doi: 10.1080/1556035X.2016.1177769

80. Kelly, JF, and Westerhoff, CM. Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. Int J Drug Policy. (2010) 21:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.10.010

81. Logan, RI . Not a duty but an opportunity: exploring the lived experiences of community health workers in Indiana through photovoice. Qual Res Med Healthc. (2018) 2:132–44. doi: 10.4081/qrmh.2018.7816

82. Mackay, T . Lived experience in social work: an underutilised expertise. Br J Soc Work. (2023) 53:1833–40. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcad028

83. Salzer, MS, and Shear, SL. Identifying consumer-provider benefits in evaluations of consumer-delivered services. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2002) 25:281–8. doi: 10.1037/h0095014

84. Byrne, L, Roennfeldt, H, Wolf, J, Linfoot, A, Foglesong, D, Davidson, L, et al. Effective peer employment within multidisciplinary organizations: model for best practice. Admin Pol Ment Health. (2022) 49:283–97. doi: 10.1007/s10488-021-01162-2

85. Pasman, E, O’Shay, S, Brown, S, Madden, EF, Agius, E, and Resko, SM. Ambivalence and contingencies: a qualitative examination of peer recovery coaches’ attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder. J Subst Use Addict Treat. (2023) 155:209121. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209121

86. Brady, LA, Wozniak, ML, Brimmer, MJ, Terranova, E, Moore, C, Kahn, L, et al. Coping strategies and workplace supports for peers with substance use disorders. Subst Use Misuse. (2022) 57:1772–8. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2022.2112228

87. Hayes, SL, and Skeem, JL. Testing assumptions about peer support specialists’ susceptibility to stress. Psychol Serv. (2022) 19:783–95. doi: 10.1037/ser0000589

88. Williams, C . To help others, we must care for ourselves: the importance of self-care for peer support workers in substance use recovery. J Addict Addict Disord. (2021) 8:071. doi: 10.24966/AAD-7276/100071

89. Kuper, LE, Cooper, MB, and Mooney, MA. Supporting and advocating for transgender and gender diverse youth and their families within the sociopolitical context of widespread discriminatory legislation and policies. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. (2022) 10:336–45. doi: 10.1037/cpp0000456

90. Zeeman, L, Sherriff, N, Browne, K, McGlynn, N, Mirandola, M, Gios, L, et al. A review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex health and healthcare inequalities. Eur J Pub Health. (2019) 29:974–80. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky226

91. van Dernoot Lipsky, L, and Burk, C. Trauma stewardship: an everyday guide to caring for self while caring for others. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers (2009).

92. Reamer, FG . (2015). Eye on ethics: the challenge of peer support programs. Soc Work Today. 15:10. Available online at: https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/072115p10.shtml

93. Waltz, J, Addis, ME, Koerner, K, and Jacobson, NS. Testing the integrity of a psychotherapy protocol: assessment of adherence and competence. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1993) 61:620–30. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.4.620

94. Scott, CK, and Dennis, ML. Recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users In: JF Kelly and WL White, editors. Addiction recovery management: theory, research and practice. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press (2011). 87–101.

95. Stiles, WB, Honos-Webb, L, and Surko, M. Responsiveness in psychotherapy. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. (1998) 5:439–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00166.x

96. Anvari, MS, Belus, JM, Kleinman, MB, Seitz-Brown, CJ, Felton, JW, Dean, D, et al. How to incorporate lived experience into evidence-based interventions: assessing fidelity for peer-delivered substance use interventions in local and global resource-limited settings. Transl Iss Psychol Sci. (2022) 8:153–63. doi: 10.1037/tps0000305

97. Elkington, KS, Nunes, E, Schachar, A, Ryan, ME, Garcia, A, Van DeVelde, K, et al. Stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial of a novel opioid court to improve identification of need and linkage to medications for opioid use disorder treatment for court-involved adults. J Subst Abus Treat. (2021) 128:108277. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108277

98. Metsch, LR, Feaster, DJ, Gooden, LK, Masson, C, Perlman, DC, Jain, MK, et al. Care facilitation advances movement along the hepatitis C care continuum for persons with human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C, and substance use: a randomized clinical trial (CTN-0064). Open Forum Infect Dis. (2021) 8:ofab334. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab334

99. Chinman, M, McCarthy, S, Mitchell-Miland, C, Daniels, K, Youk, A, and Edelen, M. Early stages of development of a peer specialist fidelity measure. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2016) 39:256–65. doi: 10.1037/prj0000209

100. Frank, HE, Becker-Haimes, EM, and Kendall, PC. Therapist training in evidence-based interventions for mental health: a systematic review of training approaches and outcomes. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. (2020) 27. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12330

101. Hogue, A . Behavioral intervention fidelity in routine practice: pragmatism moves to head of the class. Sch Ment Health. (2022) 14:103–9. doi: 10.1007/s12310-021-09488-w

102. McLeod, BD, Porter, N, Hogue, A, Becker-Haimes, EM, and Jensen-Doss, A. What is the status of multi-informant treatment fidelity research? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2023) 52:74–94. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2022.2151713

103. Davis, G, Dewey, JM, and Murphy, EL. Giving sex: deconstructing intersex and trans medicalization practices. Gend Soc. (2015) 30:490–514. doi: 10.1177/0891243215602102

104. Dewey, JM . Knowledge legitimacy: how trans-patient behavior supports and challenges current medical knowledge. Qual Health Res. (2008) 18:1345–55. doi: 10.1177/1049732308324247

105. Sileo, KM, Baldwin, A, Huynh, TA, Olfers, A, Woo, J, Greene, SL, et al. Assessing LGBTQ+ stigma among healthcare professionals: an application of the health stigma and discrimination framework in a qualitative, community-based participatory research study. J Health Psychol. (2022) 27:2181–96. doi: 10.1177/13591053211027652

106. Lee, H, and Singh, GK. Monthly trends in drug overdose mortality among youth aged 15–34 years in the United States, 2018–2021: measuring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Matern Child Health AIDS. (2022) 11:e583. doi: 10.21106/ijma.583

107. Basu, S, Patel, SY, Robinson, K, and Baum, A. Financing thresholds for sustainability of community health worker programs for patients receiving Medicaid across the United States. J Community Health. (2024) 49:606–34. doi: 10.1007/s10900-023-01290-w

108. Medicare Learning Network . (2023). Resources and training. Available online at: https://www.cms.gov/training-education/medicare-learning-network/resources-training (Accessed February 11, 2025).

109. Tsai, D (2023). Opportunities to test transition-related strategies to support community reentry and improve care transitions for individuals who are incarcerated (SMD 23-003). Available online at: https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd23003.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

110. Knowles, M, Crowley, AP, Vasan, A, and Kangovi, S. Community health worker integration with and effectiveness in health care and public health in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. (2023) 44:363–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-071521-031648

111. Navathe, AS, Chandrashekar, P, and Chen, C. Making value-based payment work for federally qualified health centers. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:1811–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.8285

112. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . (2023). Exploring value-based payment for substance use disorder services in the United States (HHS Publication No. PEP23-06-07-001). Available online at: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep23-06-07-001.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

113. Gunter, KE, Ellingson, MK, Nieto, M, Jankowski, R, and Tanumihardjo, JP. Barriers and strategies to operationalize Medicaid reimbursement for CHW services in the state of Minnesota: a case study. J Gen Intern Med. (2023) 38:70–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07925-3

114. Grella, CE, Ostlie, E, Scott, CK, Dennis, M, and Carnavale, J. A scoping review of barriers and facilitators to implementation of medications for treatment of opioid use disorder within the criminal justice system. Int J Drug Policy. (2020) 81:102768. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102768

115. Landes, SJ, McBain, SA, and Curran, GM. Reprint of: an introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 283:112630. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112630

116. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . (2022). Addressing burnout in the behavioral health workforce through organizational strategies (HHS Publication No. PEP22-06-02-005). Available online at: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep22-06-02-005.pdf (Accessed February 11, 2025).

117. Bakker, AB, and Demerouti, E. Job demands-resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol. (2017) 22:273–85. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056

118. Hobfoll, SE . Conservation of resources theory: its implication for stress, health, and resilience In: S Folkman , editor. The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping. Oxford: Oxford Academic (2011). 127–47.

119. Brown, O, Kangovi, S, Wiggins, N, and Alvarado, CS. Supervision strategies and community health worker effectiveness in health care settings. NAM Perspect. (2020). doi: 10.31478/202003c

120. Specchia, ML, Cozzolino, MR, Carini, E, Di Pilla, A, Galletti, C, Ricciardi, W, et al. Leadership styles and nurses’ job satisfaction. Results of a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1552. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041552

121. Orwat, J, Kumaria, S, and Dentato, MP. Financing and delivery of behavioral health in the United States In: C Moniz and S Gorin, editors. Behavioral and mental health care policy and practice. New York: Routledge (2018). 78–102.

122. Shmerling, AC, Gold, SB, Gilchrist, EC, and Miller, BF. Integrating behavioral health and primary care: a qualitative analysis of financial barriers and solutions. Transl Behav Med. (2020) 10:648–56. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz026

123. Baumeister, RF, and Leary, MR. Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev Gen Psychol. (1997) 1:311–20. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.1.3.311

124. Adams, WE, and Lincoln, AK. Barriers and faciltators of implementing peer support services for criminal justice-involved individuals. Psychiatr Serv. (2021) 72:626–632. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900627

125. McCrary, H, Etwaroo, R, Marshall, L, Burden, E, St Pierre, M, Berkebile, B, et al. Peer recovery support services in correctional settings. Bureau of Justice Assistance Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulant, and Substance Abuse Program (COSSAP) Training and Technical Assistance (TTA) Center on Peer Recovery Support Services. (2022)

126. Corrigan, PW, Rüsch, N, Watson, AC, Kosyluk, K, and Sheehan, L. Principles and practice of psychiatric rehabiliatation: Promoting recovery and self-determination. Ed 3. Guildford Press. (2024).

127. O’Rourke-Suchoff, D, Sobel, L, Holland, E, Perkins, R, Saia, K, and Bell, S. The labor and birth experience of women with opioid use disorder: A quakitative study. Women and Birth, (2020) 33, 592–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.01.006

128. Stone, R. Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health and Justice, (2015) 3, 1–5. doi: 10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5

Keywords: linkage facilitation, opioid use disorder, medication for opioid use disorder, workforce support, professional standards

Citation: Drazdowski TK, Coetzer-Liversage AP, Stein LAR, Tilson M, Watson DP, Hoffman LA, Hogue A, Castedo de Martell S, Hagaman AM, Greene RN, Satcher MF, Hibbard PF, Dewey JM, Sheidow AJ and Vest N (2025) Supporting linkage facilitators working with persons with opioid use disorder: challenges, advances, and future directions. Front. Public Health. 13:1587101. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1587101

Edited by:

Julia Dickson-Gomez, Medical College of Wisconsin, United StatesReviewed by:

Olaniyi Olayinka, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, United StatesElizabeth O. Obekpa, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, United States