- 1Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Brain Hospital, Liuzhou, China

- 2Liuzhou Liujiang District Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Liuzhou, China

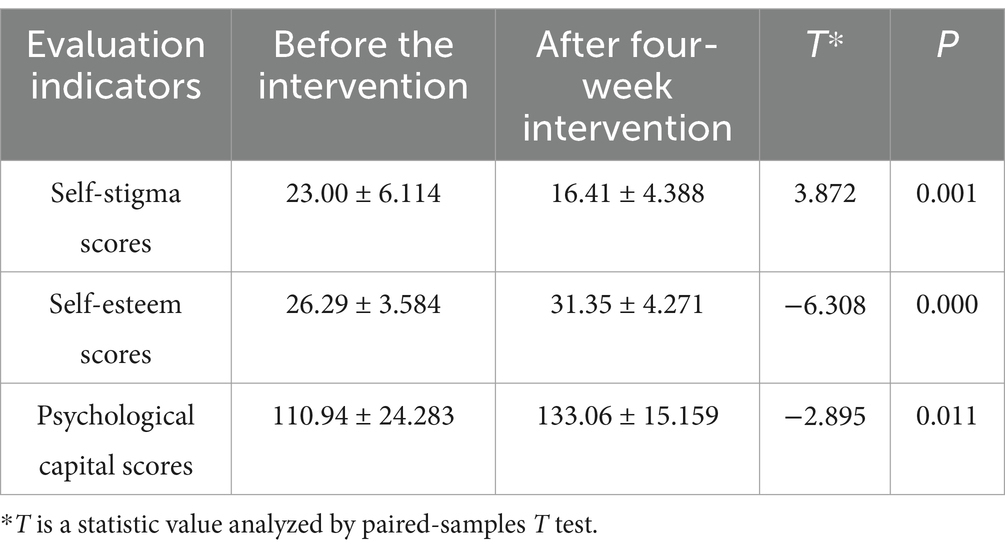

Self-stigma has been consistently cited as a major obstacle to recovery-related outcomes among patients with schizophrenia. To examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the group-based narrative intervention for improving self-stigma, self-esteem and psychological capital in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia, a case-series study was conducted from March to May 2023 in a closed psychiatric ward of a specialized hospital in mainland China. Feasibility was assessed by examining rates of recruitment, retention, and protocol adherence. Acceptability was assessed through the therapist’s and patients’ feedback about the intervention. Changes in the levels of self-stigma, self-esteem, and psychological capital perceived by patients were measured before and after 4 weeks of intervention. Rates of enrolment (85%) and completion of intervention sessions and study procedures (100%) were excellent, demonstrating high rates of feasibility among these patients in the local setting. The feedback from participants and the therapist about satisfaction, helpfulness, and difficulty of the intervention was largely positive, demonstrating high rates of acceptability. And the results indicated significant improvements in patients’ self-reported self-stigma, self-esteem, and psychological capital (change in T = 3.872, p = 0.001; T = −6.308, p < 0.001; T = −2.895, p = 0.011, respectively). The study provided a structured intervention program for clinical care to reduce self-stigma and promote positive recovery outcomes for inpatients with schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia, characterized by profound disruptions in an individual’s thinking, perception, speech, and behavior causes psychosis and is associated with considerable disability (1). Schizophrenia significantly contributes to the global burden of disease, affecting approximately 1% of the global population, and is one of the top 10 causes of disability worldwide (2). Stigma, defined as the devaluation of a group or individual on the basis of a characteristic that is discredited by society, is highly prevalent among people with schizophrenia and has been consistently cited as a major obstacle to recovery and quality of life among those people (3, 4). A systematic review with over 25,000 participants reported that 35% of persons diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders overall demonstrated elevated self-stigma (5).

Public stigma refers to negative stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination against individuals by the outside world, whereas self-stigma occurs when individuals agree with and internalize these negative stereotypes and prejudices about their devalued conditions and suffer numerous negative consequences as a result (6–8). With respect to illness and pathologies, biomedical discourse, and public stigma, people with schizophrenia often perceive themselves as “dangerous,” “incompetent,” as well as “worthless” and believe that they have become a burden on their family and society (9, 10). This may lead to the idea that their inner self is the cause of the problem, which could result in negative self-identity (11). The public stigma embedded in the Chinese-dominant culture further causes negative self-identity among people with schizophrenia (11, 12), resulting in the internalization of negative stereotypes, self-stigma and its adverse effects (6, 13).

Stigma has been implicated in worsening outcomes for people with schizophrenia (13, 14). Patients who experience self-stigma are unable to maintain positive self-identity, resulting in reduced self-esteem, self-efficacy, and self-worth (15, 16). Hence, patients tend to adopt negative coping strategies such as avoidance and withdrawal, which are associated with reduced treatment compliance and diminished social functioning and quality of life, and even make patients feel hopeless and increase the risk of suicide (13, 17, 18). Despite the substantial evidence for the negative effects of self-stigma, the development of anti-stigma interventions is a relatively limited area of research (3, 11, 19). As a result, there has been a shift in interest toward developing interventions to address and ameliorate self-stigma.

The evidence on the effectiveness of narrative therapy among patients with serious mental illness is promising but limited (10, 20–22). The primary focus of narrative therapy is people’s expression of their experiences, which focuses on meaning-making and transforming one’s life story from a more positive and appreciative perspective (23), instead of focusing on the disabilities and limitations from the traditional problem-focused model (24). It holds that problems separate from the individual could be solved through therapeutic conversations, and assumes that everyone has inner resources, skills, and competencies to accommodate transitions and challenges in their lives (24). During therapeutic conversations, therapists help participants to deconstruct their problem-saturated story from the illness experience, coconstruct their inner strengths and beliefs from previous life challenges, and reconstruct their positive identity (24). In group practice, the narrative process allows participants to gain supportive feedback and experiences, skills, and knowledge from peers and provides ongoing outsider witnesses to strengthen individual positive self-identity (18, 25, 26). Despite the limited evidence, it has been demonstrated that group-based narrative interventions could improve self-esteem in patients with severe mental illness and reduce their self-stigma (9, 10, 19, 25). In addition, the targeted interventions were also supposed to focus on improving psychological capital (e.g., self-esteem, self-efficacy, resilience, hope and optimism), which were found to positively influence stigma resistance and counteract internalized stigma (11, 12, 27).

Given the negative consequences of self-stigma in the recovery process among patients with schizophrenia, there seems to be a need to expand the current evidence concerning narrative intervention. To date, there has been no attempt to apply a group-based narrative intervention among hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in the Chinese mainland (20, 28). Therefore, the aim of the current study was to pilot examining the feasibility and acceptability of a group-based narrative intervention consisting of eight sessions for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia. We also evaluated the preliminary efficacy in reducing self-stigma and improving the self-esteem and psychological capital of patients.

Methods

Design

A case series study was employed, as the first stage of piloting within the process of intervention development, informed by the Medical Research Council recommendation framework for the development of complex interventions (29). Ethical approval was obtained from the Committee of Ethics at the Hospital before the study procedures began (No. 2022-021). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All methods were performed in accordance with the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Setting

The study was performed in the closed psychiatric ward which only admits female patients with mental disorders in the local specialized hospital. It is the largest specialized hospital for mental and psychological disorders in Liuzhou, a city in southern China. The study hospital, with medical treatment, teaching, scientific research, prevention, rehabilitation, and medical identification, offers advanced health services for people with mental and psychological disorders from regional and surrounding areas (30). The psychiatry department consists of 15 psychiatric wards, which service an average of 700 hospitalized patients per day, seven of which are under closed management. The ward in which the study was conducted has a capacity of approximately 70 beds per ward, servicing more than 60 hospitalized patients per day.

Participants

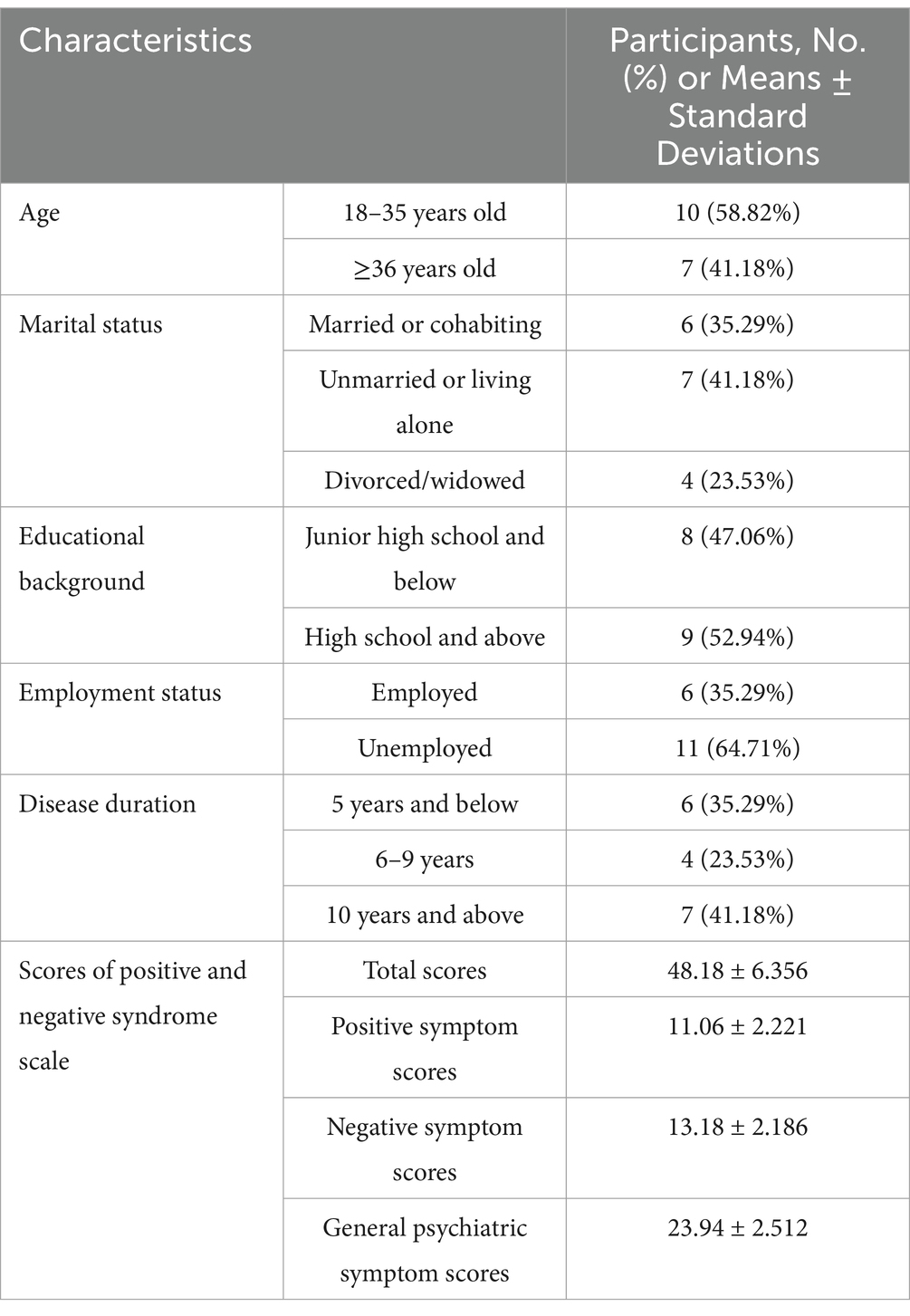

A convenience sample of hospitalized patients in the closed psychiatric ward from March to May 2023, where a total of 17 eligible patients were employed, was used. The inclusion criteria for selecting the subjects were as follows: (1) diagnosed with schizophrenia who scored 60 points and below on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); (2) aged 18–60 years; (3) had sufficient cognitive and communicative ability to participate; and (4) provided informed consent and volunteered to participate in the study. Patients were excluded if they (1) were co-diagnosed with other mental disorders; (2) had a serious physical illness; (3) had severe cognitive impairment or symptoms such as excited impulsivity, suicidal ideation with intent or plan, or reported recent self-harm; or (4) had poor compliance or withdrawal.

Procedures

The research team was established to implement the procedures successfully.

The principal researcher (QZ), experienced in individual narrative and group counseling and two advanced clinical consultant psychologists (YW and ZH) were involved in the development of the intervention. The principal researcher carried out the program training of the intervention and techniques to the other researchers and assessed them for quality. The narrative therapist (XW) certified with psychological consultation delivered the intervention, which was supervised by the advanced clinical consultant psychologists (ZH and YZ). The other two researchers (LW and DH) who did not work in the ward were assigned to complete the screening and organize the distribution and collection of questionnaires, which aimed to maintain the rights of the participants to not consent to the study.

Potential participants were first screened via the electronic medical records of the hospitalized patients. If eligible on the basis of this screening, they were invited for interview screening. Following the interview screening, eligible participants were invited for the research project. The written questionnaires, together with a cover letter of informed consent that assured the confidentiality of information and autonomy of the participants who anonymously participated, were distributed to the eligible participants. Additionally, a five-minute long WeChat video, which illustrated the background, purpose and significance of the study, which aimed to arouse the interest and resonance of patients, was delivered to each eligible participant. Moreover, it explained the meanings of the questionnaires with instructions on how they should be completed and how to manage the information and data of the participants.

Intervention

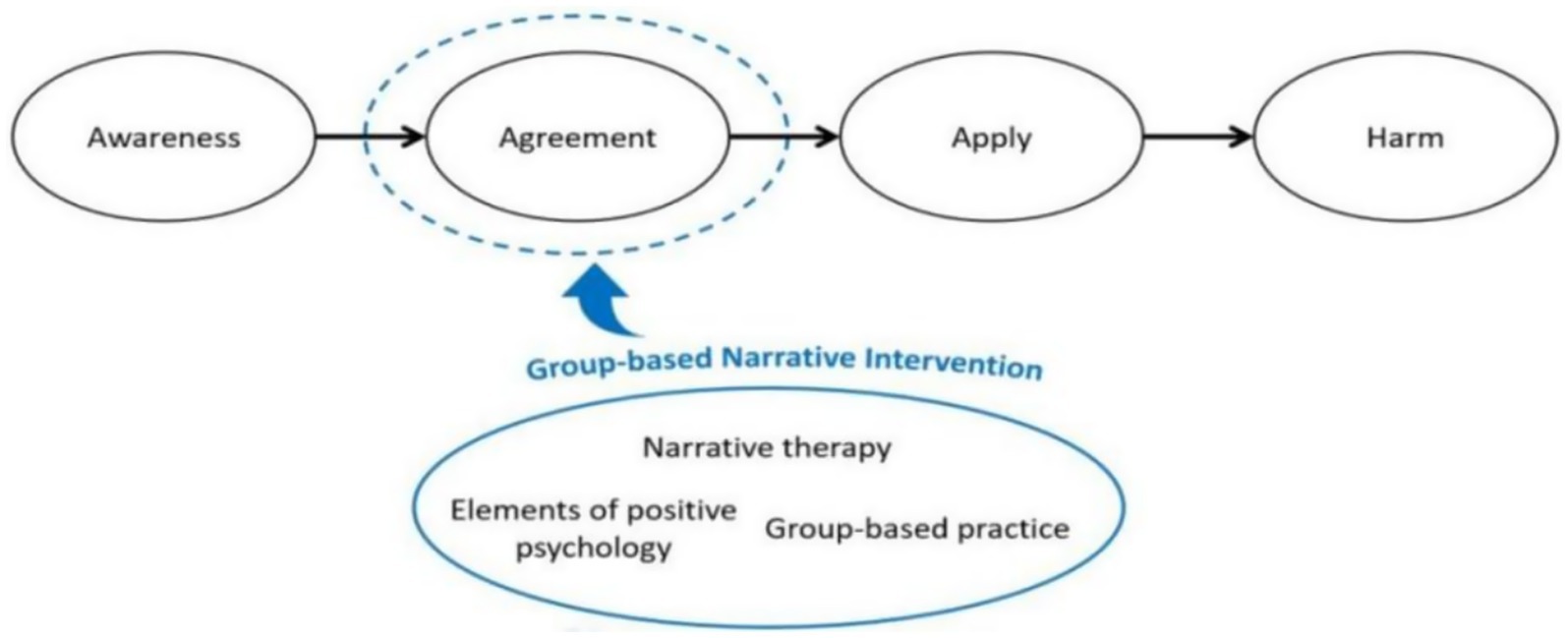

The theoretical framework of the narrative intervention was developed by the stage model of self-stigma and relevant evidence (6, 11, 12, 27, 31–34), as shown in Figure 1. According to Corrigan’s model (6), the formation and influence process of self-stigma includes four stages: awareness, agreement, application and harm. When people perceive and identify with the public negative stereotype about their disease, the negative stereotype is then internalized to be self-prejudiced and self-discriminated, ultimately resulting in negative emotional reactions and behavioral responses. Therefore, the agreement of negative stereotypes plays a key role in the formation of self-stigma, which the current intervention focuses on. Narrative intervention contributes to the reconstruction of their positive identity. Additionally, it was based on group psychotherapy, where the other participants were regarded as outsider witnesses used to strengthen their preferred identity. Moreover, the intervention also targeted to improve the elements of positive psychology, such as self-esteem and positive psychological capital, which have been shown to be protective factors for reducing patients’ self-stigma and enhancing resistance to stigma.

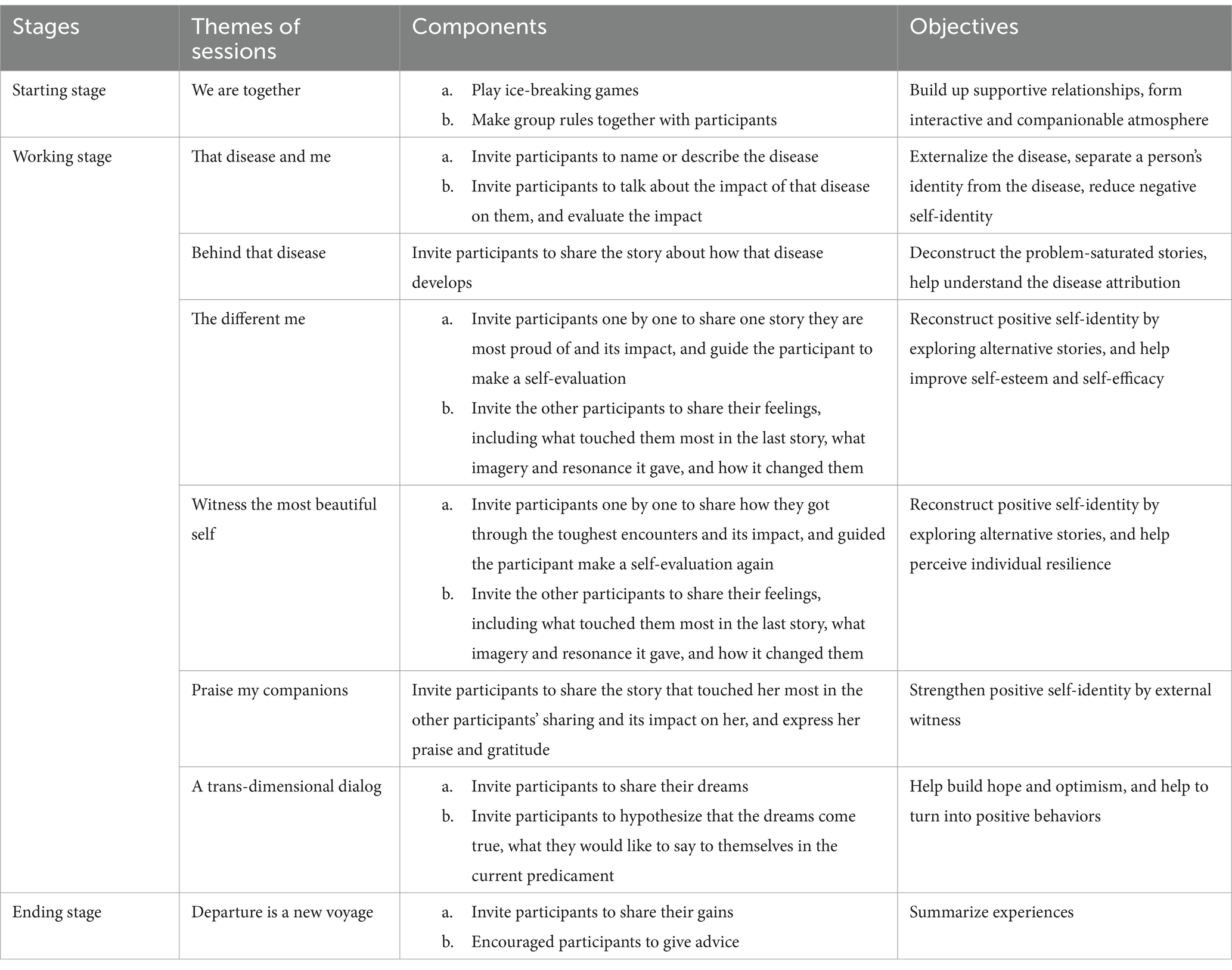

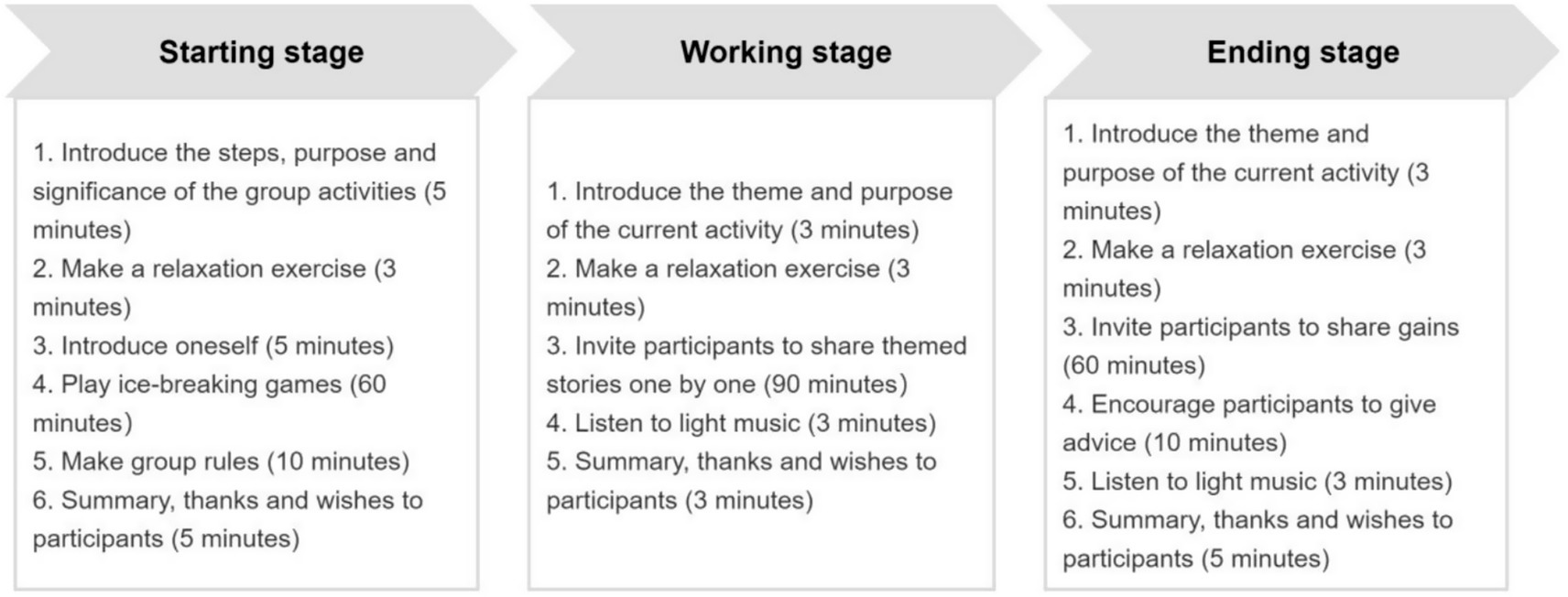

The group-based narrative intervention was composed of three stages, for a total of eight sessions, and the components of the intervention are shown in Table 1. The operation procedure of each stage is shown in Figure 2. The sessions were implemented by the narrative therapist in a separate psychotherapy room, where the outside door had a sign that read “Be quiet, meeting in process,” approximately 90 min each session, twice a week, and lasted for 4 weeks. During each session of the working stage, participants were invited to share thematic stories guided by the therapist, with the principle of being voluntary, nonjudgmental, respectful, and confidential.

Feasibility and acceptability objectives

Feasibility was assessed by examining rates of recruitment, retention, and protocol adherence. Acceptability was assessed through participants’ feedback.

Fidelity

Each session was audio-recorded and listened to by the therapist’s supervisors to assess fidelity, which guarantees that the intervention could be delivered adequately by the therapist. Session recordings were rated a dichotomous yes/no score for whether the therapist adhered to the session protocol. Protocol violations were recorded, and were fed back to the therapist.

Measures

Demographic data questionnaire and the standardized scales were completed at pre-intervention. The levels of self-stigma, self-esteem, and psychological capital perceived by patients were reevaluated after 4 weeks of intervention.

Demographic data questionnaire. Demographic information included age, marital status, educational background, employment status, and disease duration.

Self-Stigma Scale-Short Form (SSS-S). The scale consists of 9 items with a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). It contains three subscales: self-stigmatizing cognitions, self-stigmatizing affect, and self-stigmatizing behaviors. The higher the score is, the greater the level of self-stigma perceived. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the total scale and dimensions ranged from 0.80 to 0.91 (35).

Self-Esteem Scale (SES). The scale was used to assess overall feelings about self-worth and self-acceptance. It contains 10 items with a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree), of which five items provide a negative statement and are reverse scored. The total scores range from 10 to 40. Higher scores indicate greater levels of self-esteem perceived by patients. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the total scale was 0.88 (36).

Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PPQ). The questionnaire contains 26 items divided into four domains: self-efficacy, resilience, optimism, and hope. Each item is scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a higher level of psychological capital. The total scores range from 26 to 182. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the total scale and dimensions ranged from 0.76 to 0.90 (37).

Feedback

Qualitative feedback was collected from the participants, therapist, and supervisors after intervention delivery was completed, with open-ended questions about the content, process, and usefulness of the intervention. During the interviews, the principal researcher maintained a neutral attitude and did not express personal judgments, beliefs, or understanding.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed via the Statistical Program for Social Sciences version 22.0. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data. The count data are presented as frequencies and composition ratios. The measurement data conforming to normal distribution or approximate normal distribution were reported as means and standard deviations. A paired-samples t test was performed to compare the measured data before and after the intervention. Statistical significance was specified at 95% confidence intervals and two-tailed p values of less than 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 17 patients were enrolled in the study and completed the intervention. Table 2 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of all the participants.

Feasibility

The recruitment target was reached in a two-week period with two researchers working part-time. The researchers attempted to reach 20 patients for the study, while 17 of those (85%) assessed were deemed eligible and enrolled in the study. The retention rate was high, with no sample lost during the intervention, and all participants completed the intervention and measures. All participants completed the questionnaires fully before and after the intervention.

Acceptability

In the feedback interviews, all the participants expressed that the intervention was helpful and satisfactory. Most participants (15 patients [88.24%]) found 8 sessions to be the right length and found the intervention to contain the right amount of information. In addition, 14 patients (82.35%) indicated that the content of the intervention was easy to understand, whereas 3 participants (17.65%) who reported some degree of difficulty did not specify the aspects that were difficult to understand. Moreover, approximately half of the participants reported that they would like to participate in more sessions, such as this, during their hospitalization. Additionally, the feedback from the therapist about the experience of delivering the intervention was positive, particularly for the modular structure, enabling sessions to be delivered flexibly.

Fidelity

For the fidelity of the intervention, 100% consistency in the pacing, introduction to purpose of intervention and the delivery of intervention components were observed, meeting the benchmarks for treatment fidelity.

Changes in measures

A total of 17 patients were enrolled and completed final measures and feedback. There were significant improvements in self-stigma, self-esteem, and psychological capital from pre- to post-intervention (change in T = 3.872, p = 0.001; T = −6.308, p < 0.001; T = −2.895, p = 0.011, respectively). Reliable improvements in self-stigma were made by 13 participants (76.47%) at post-intervention. Reliable recovery in self-esteem was found for 15 participants (88.24%) at post-intervention. With respect to psychological capital, 12 participants (70.59%) made reliable improvements at post-intervention. The results of the statistical analysis of the pre- and post-operative changes in the outcomes via standardized questionnaire scores are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. The self-stigma, self-esteem and psychological capital scores of patients before and after the intervention (means±standard deviations).

Discussion

In the context of this case series study, we examined the feasibility, acceptability, fidelity, and preliminary efficacy of the group-based narrative intervention composed of eight sessions, which was the first attempt to develop and apply a group-based narrative intervention for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in mainland China. Randomization was not included because the purpose of the current study was to undertake primary data collection related to the feasibility and acceptability of the novel intervention. The results suggested that the group-based narrative intervention and its procedures were feasible, acceptable, had high rates of intervention fidelity, and demonstrated potential efficacy at improving targeted outcomes. The rates of enrolment (85%) and completion of intervention sessions and study procedures (100%) were outstanding, demonstrating high rates of feasibility among these patients in the local setting. The feedback from the participants and the therapist about the level of satisfaction, helpfulness, and difficulty of the intervention was largely positive, demonstrating high rates of acceptability. Additionally, some participants hoped that there were more activities like it to participate in.

Most promising, the study results indicated significant improvements in participants’ self-reported self-stigma, self-esteem, and psychological capital, which suggested that the group-based narrative intervention might be an effective intervention at improving self-stigma and the related outcomes for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia. These findings were consistent with those of previous studies supporting the effectiveness of group-based narrative intervention (9, 10, 19, 25). It appeared that the narrative intervention process affirms and reconstructs a self-identity of participants that was possibly troubled by its problem, improving their self-perceived cognitive about the disease and rejecting a negative self-identity due to public stigma (38). Therefore, the internalization of perceived stigma was reduced. Simultaneously, on the basis of group practices, positive self-identity was further strengthened by ongoing external witnesses with other participants. Additionally, its effectiveness was enhanced by intervening with elements of positive psychology, increasing the resistance of public stigma (11, 27, 39, 40).

For the process of the intervention, sessions 2 and 3 were performed to help participants understand the attribution of the disease and reduce negative self-attribution about the disease and the problem-saturated identity. This study provides a new perspective for participants in understanding disease and its effects instead of providing a view of their disabilities and limitations. By exploring alternative stories during sessions 4–6, it focused on developing self-esteem, self-efficacy, and resilience and reconstructing the positive self-identity of participants as opposed to the negative self-identity. In addition, session 7 further focused on increasing the hope level of participants to regain the power to move closer to their hopes and dreams, which helped to turn their positive self-identity into positive behaviors to cope with present difficult situations. By exploring narratives from participants’ past experiences, the patients in the study had the opportunity to appreciate their strengths, resources, and capabilities and develop problem-solving skills to overcome challenges. Hence, the participants’ perceptions of their efficiency and worthiness were greatly increased. This narrative intervention poses an alternative methodology to counteract negative stereotypes, providing participants with restructuring cognitive and adaptive coping tools.

Limitations

Despite promising results, there are limitations that must be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this study. First, this finding is only reflective of the practice among hospitalized female patients with schizophrenia in the local setting from southern China. As a result, it is unclear whether the intervention is applicable to male patients and other regions. Second, the sample size and pre-post design limit the ability to examine the efficacy of the group-based narrative intervention. It is not possible to conclude that the observed changes in the measures were associated with the intervention. Finally, the feasibility of therapists new to the intervention being able to deliver it adequately in real-world settings, including less intense supervision, requires investigation.

Future research

In future research, the next stage of investigation should include randomization and blinded researchers to provide a more reliable estimate of the effect size associated with the intervention. Further investigations should examine the feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of the intervention in the multiple-spot context with multiple samples. A longer follow-up investigation post-intervention would enable exploration of the longer-term effects of the intervention.

Conclusion

Preliminary evidence from this case series study revealed that the group-based narrative intervention was feasible and acceptable in mainland China. Furthermore, significant improvements were observed in reducing self-stigma and improving self-esteem and psychological capital among these patients. However, these findings indicated the need for further investigations in future research. Even so, a pilot study of group-based narrative practices proposed a viable perspective to improve self-stigma and its potentially negative consequences for people with schizophrenia.

Relevance for clinical practice

This was the clinical practice to carry out a pilot study of a group-based narrative intervention tailored for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in mainland China, aiming to improve their perceived self-stigma, self-esteem, and psychological capital. On the one hand, the study method provided a perspective for the development of complex interventions based on the Medical Research Council recommendation framework in the clinical care of patients with mental illness. On the other hand, this study provided a structured intervention program for clinical care to reduce self-stigma and promote positive recovery outcomes for inpatients with mental illness.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: aggregated data is provided within the manuscript, while individual data is unavailable due to ethical restrictions. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Yuting Huo, NzU3NTE0OTEzQHFxLmNvbQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Medical Ethics Committee, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Brain Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

QZ: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YW: Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation, Conceptualization. ZH: Project administration, Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. SQ: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XW: Investigation, Writing – original draft. LW: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation. DH: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation. MQ: Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. FQ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. YH: Writing – review & editing, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study were funded by Guangxi medical and health appropriate technology development and application project (Nos. S2022040 and S2023047), Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Brain Hospital cultivation project (No. 2022GXNKYY-003) and self-funded scientific research project of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Traditional Chinese Medicine Administration (No. GXZYB20240286).

Acknowledgments

The authors especially thanks to all the participants who have contributed in developing knowledge and sharing their experience in the intervention.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. WHO. Schizophrenia. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia (2022).

2. Velligan, DI, and Rao, S. The epidemiology and global burden of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. (2023) 84:MS21078COM5. doi: 10.4088/jcp.Ms21078com5

3. Pescosolido, BA, Halpern-Manners, A, Luo, L, and Perry, B. Trends in public stigma of mental illness in the US, 1996-2018. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2140202. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40202

4. Oexle, N, Müller, M, Kawohl, W, Xu, Z, Viering, S, Wyss, C, et al. Self-stigma as a barrier to recovery: a longitudinal study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2018) 268:209–12. doi: 10.1007/s00406-017-0773-2

5. Dubreucq, J, Plasse, J, and Franck, N. Self-stigma in serious mental illness: a systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophr Bull. (2021) 47:1261–87. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa181

6. Corrigan, PW, and Rao, D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can J Psychiatr. (2012) 57:464–9. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700804

7. Corrigan, PW, and Watson, AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. (2002) 1:16–20.

8. Corrigan, PW, Druss, BG, and Perlick, DA. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychol Sci Public Interest. (2014) 15:37–70. doi: 10.1177/1529100614531398

9. Yanos, PT, Lucksted, A, Drapalski, AL, Roe, D, and Lysaker, P. Interventions targeting mental health self-stigma: a review and comparison. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2015) 38:171–8. doi: 10.1037/prj0000100

10. Roe, D, and Yamin, A. Narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy: a group intervention to reduce self-stigma in people with severe mental illness. Vertex. (2017) 28:384–90.

11. Shi, X, Sun, X, Zhang, C, and Li, Z. Individual stigma in people with severe mental illness: associations with public stigma, psychological capital, cognitive appraisal and coping orientations. Compr Psychiatry. (2024) 132:152474. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2024.152474

12. Young, DK, and Ng, PY. The prevalence and predictors of self-stigma of individuals with mental health illness in two Chinese cities. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2016) 62:176–85. doi: 10.1177/0020764015614596

13. Szcześniak, D, Kobyłko, A, Wojciechowska, I, Kłapciński, M, and Rymaszewska, J. Internalized stigma and its correlates among patients with severe mental illness. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2018) 14:2599–608. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S169051

14. Livingston, JD, and Boyd, JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 71:2150–61. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030

15. Corrigan, PW, Larson, JE, and Rüsch, N. Self-stigma and the "why try" effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry. (2009) 8:75–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x

16. Langford, K, McMullen, K, Bridge, L, Rai, L, Smith, P, and Rimes, KA. A cognitive behavioural intervention for low self-esteem in young people who have experienced stigma, prejudice, or discrimination: an uncontrolled acceptability and feasibility study. Psychol Psychother. (2022) 95:34–56. doi: 10.1111/papt.12361

17. Yanos, PT, DeLuca, JS, Roe, D, and Lysaker, PH. The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112950. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112950

18. Yanos, PT, Lysaker, PH, Silverstein, SM, Vayshenker, B, Gonzales, L, West, ML, et al. A randomized-controlled trial of treatment for self-stigma among persons diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2019) 54:1363–78. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01702-0

19. Hansson, L, Lexén, A, and Holmén, J. The effectiveness of narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy: a randomized controlled study of a self-stigma intervention. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2017) 52:1415–23. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1385-x

20. Jagan, S, Mohd Daud, TI, Chia, LC, Saini, SM, Midin, M, Eng-Teng, N, et al. Evidence for the effectiveness of psychological interventions for internalized stigma among adults with schizophrenia Spectrum disorders: a systematic review and Meta-analyses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:5570. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20085570

21. Huang, LT, Liu, CY, and Yang, CY. Narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy for perceived stigma of chronic schizophrenia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2023) 44:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2023.04.004

22. Oudejans, S, de Winter, L, van Weeghel, J, Sanches, S, and Hasson-Ohayon, I. Feasibility and outcomes of narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy (NECT) for reducing self-stigma among people with severe mental illness in the Netherlands: a pilot study. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2022) 45:255–65. doi: 10.1037/prj0000526

23. Frank, AW. What is narrative therapy and how can it help health humanities? J Med Humanit. (2018) 39:553–63. doi: 10.1007/s10912-018-9507-3

24. Chow, EO. Narrative therapy an evaluated intervention to improve stroke survivors' social and emotional adaptation. Clin Rehabil. (2015) 29:315–26. doi: 10.1177/0269215514544039

25. Yanos, PT, Roe, D, and Lysaker, PH. Narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy: a new group-based treatment for internalized stigma among persons with severe mental illness. Int J Group Psychother. (2011) 61:577–95. doi: 10.1521/ijgp.2011.61.4.576

26. Firmin, RL, Luther, L, Lysaker, PH, Minor, KS, McGrew, JH, Cornwell, MN, et al. Stigma resistance at the personal, peer, and public levels: a new conceptual model. Stigma Health. (2017) 2:182–94. doi: 10.1037/sah0000054

27. Na, Y, Xiaohong, G, and Yan, Z. Influencing factors of self shame and shame resistance in schizophrenics and the analysis of nursing effect based on the theory of positive psychology. J Changchun Univ Chin Med. (2020) 36:1282–5. doi: 10.13463/j.cnki.cczyy.2020.06.054

28. Xu, Z, Huang, F, Kösters, M, and Rüsch, N. Challenging mental health related stigma in China: systematic review and meta-analysis. II. Interventions among people with mental illness. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 255:457–64. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.002

29. O'Cathain, A, Croot, L, Duncan, E, Rousseau, N, Sworn, K, Turner, KM, et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e029954. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029954

30. Hospital TGZARB. Hospital profile. Available online at: http://www.gxnkyy.com/yyjj.aspx (2024).

31. Xiaolin, T, Li, W, Bingxiang, Y, Xiaoqin, W, Ziwei, W, and Yu, Y. Effects of a group self-assertiveness training intervention on stigma of patients with schizophrenia. Chin J Nurs. (2018) 53:1168–73. doi: 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2018.10.003

32. Liu, Z. Effect of group system self-affirmation intervention on self-esteem and stigma of patients with schizophrenia. Nurs Pract Res. (2020) 17:153–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-9676.2020.16.058

33. Huang, B, and Chen, Y. Application of life tree narrative therapy in alleviating stigma among long-term hospitalized patients with chronic stable schizophrenia. Chin Med Ethics. (2023) 36:83–8. doi: 10.12026/j.issn.1001-8565.2023.01.15

34. Yanqi, X, Qingnian, H, Fen, M, Caiyun, W, Juhong, Z, Sufang, L, et al. Effect of narrative therapy on stigma and self-esteem in patients with schizophrenia. J Nurs Sci. (2024) 39:84–7. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2024.01.084

35. Mak, WW, and Cheung, RY. Self-stigma among concealable minorities in Hong Kong: conceptualization and unified measurement. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (2010) 80:267–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01030.x

36. Tian, L. Shortcoming and merits of Chinese version of Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale. Psychol Explor. (2006) 26:89–92. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-5184.2006.02.020

37. Kuo, Z, Sai, Z, and Yinghong, D. Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with mental health. Stud Psychol Behav. (2010) 8:58–64.

38. Shin, YJ, Joo, YH, and Kim, JH. Self-perceived cognitive deficits and their relationship with internalized stigma and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2016) 12:1411–7. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S108537

39. Kao, YC, Lien, YJ, Chang, HA, Tzeng, NS, Yeh, CB, and Loh, CH. Stigma resistance in stable schizophrenia: the relative contributions of stereotype endorsement, self-reflection, self-esteem, and coping styles. Can J Psychiatr. (2017) 62:735–44. doi: 10.1177/0706743717730827

Keywords: self-esteem, psychological capital, schizophrenia, narrative nursing, self-stigma

Citation: Zhou Q, Wei Y, Huang Z, Zhao Y, Qin S, Wei X, Wei L, Huang D, Qin M, Zeng L, Qin F and Huo Y (2025) A pilot short-term study of feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of 3-stage 8-session 4-week group therapy-based narrative intervention in 17 improved hospitalized female schizophrenia patients in southern China. Front. Public Health. 13:1594471. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1594471

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité University Medicine Berlin, GermanyCopyright © 2025 Zhou, Wei, Huang, Zhao, Qin, Wei, Wei, Huang, Qin, Zeng, Qin and Huo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fengqiong Qin, MTA2MjY3MTk0MkBxcS5jb20=; Yuting Huo, NzU3NTE0OTEzQHFxLmNvbQ==

Qian Zhou1

Qian Zhou1 Yuting Huo

Yuting Huo