- 1School of Health Sciences, Polytechnic University of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal

- 2Centre for Innovative Care and Health Technology (ciTechCare), Polytechnic University of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal

- 3Comprehensive Health Research Centre (CHRC), University of Évora, Évora, Portugal

- 4Applied Psychology Research Centre Capabilities & Inclusion, ISPA – Universitary Institute, Lisbon, Portugal

- 5Universidad Internacional La Rioja, La Rioja, Spain

- 6Universidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia

- 7Internal Medicine and Intensive Care Department, Hospital da Luz – Arrábida, Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal

- 8RISE-Health, Nursing School of Porto (ESEP), Porto, Portugal

Background: In palliative care (PC), family caregivers (FCs) play an important role in managing patient symptoms and addressing patient needs. In end-of-life (EoL), FCs frequently experience distress that exacerbates emotional strain and complicates grieving. Training FCs to care for palliative patients should be implemented urgently, enhancing their preparation, reducing their burden, and assuring Quality of Life (QoL) throughout illness progression. Recent research has highlighted a global shift toward death in the community, in line with patient preferences. In contrast, the Portuguese reality reveals a tendency to die in hospitals and an absence of community PC and support for FCs, a model that might not be sustainable in the future.

Aims: The overall aim of this study is to comprehensively assess the unmet needs of FCs in home-based PC settings and their experiences interacting with PC services, and to propose strategies and recommendations for FC advocacy in PC.

Methods: A multi-stage mixed-methods design will be used, divided into four main phases. Phase I will identify unmet needs and profile FCs through a quantitative cross-sectional analysis of a nationally representative sample. Phase II will develop a qualitative study to understand the role and impact of FCs providing PC and their experiences with support from PC services. This will help generate ideas for more accessible and sustainable PC-in-place. Phase III will comprise a multi-phased, consensus-based approach to identify priority areas of need, as decided by FCs and professionals, and develop a short Caregivers Assessment Tool (CAT). Lastly, phase IV will synthesize the results and produce a white book for FC advocacy in PC.

Discussion: The project will enrich community PC while optimizing social welfare activities. By identifying the unmet requirements of FCs of PC patients, the initiative will enhance the QoL and well-being of the care recipients, respecting their preferences, while improving the health and competence of FCs, and minimizing the consumption of hospital resources. Lastly, FC engagement should be coordinated and sustainably executed through the participation of relevant all stakeholders.

1 Introduction

In Portugal, as in other European nations, palliative care (PC) is acknowledged as a human right. The Basic Law for Palliative Care (Law No. 52/2012) established the National Network for Palliative Care (NNCP) to deliver active and comprehensive support to patients with severe ill conditions and their families. The NNCO encompasses several specialized PC units/teams, in hospitals, the community, or at home (1, 2).

There has been a recent uptick in providing PC patients with in-home care services, perhaps driven by the rising number of people who prefer being cared for and dying in the comfort of their own home rather than in a hospital or nursing home (3, 4). Evidence demonstrates that home death is unlikely without family caregivers (FCs) (5), highlighting their importance in enabling end-of-life (EoL) care at home. Promoting home-based care is economically advantageous for healthcare systems, decreasing emergency room visits and hospitalizations, while alleviating inequities in access to PC (1, 2). Nonetheless, the progress of home-based PC necessitates the fulfillment of specific criteria. There must be a family member capable of assisting the patient in the absence of social and healthcare professionals tasked with home-based care. Therefore, the implementation of home-based PC programs might be difficult, particularly in cases involving individuals who reside alone or together with older people (1, 2). Alongside the challenges posed by families’ social contexts, systemic deficiencies within the healthcare framework, including resource limitations and shortages in professional training—especially in generalist PC—impede the evolution of this practice, despite the existence of established legal rights.

Caring for someone at the EoL can be arduous and demanding: one in ten FCs attending to a patient at EoL encounters a care-related burden (6–8). In a home environment, this burden can be especially significant, as the patient increasingly relies on FC assistance. Additionally, FCs may suffer anticipatory grief of their relative’s approaching death (6, 9). Among at-home FCs, the probability of significant burden rises from 32% in the second and third months prior to death to 66% one week before death (10). Burden may lead to physical and psychological morbidity, limitations on the caregiver’s life, and a burden on financial resources (11–13). Older individuals relying on family caregivers are particularly vulnerable to physical and psychological health complications during EoL care (14, 15). The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the need to acknowledge frontline FCs (16). FCs must secure timely help to avert overload and improve their caregiving capacity. This may also pertain to the quality of life and, eventually, the quality of the patient’s final days. Healthcare providers possess multiple methods to assist FCs. Generally, these can be categorized into two domains: (1) empowering FCs in delivering care (as “co-workers”) (17), which includes practical aid with caregiving tasks, care coordination, information provision (18–21), and support in symptom management or medication administration (18, 22, 23); and (2) providing psychosocial support designed to enhance the wellbeing of the FC (as “co-client”) (13), encompassing respite care (e.g., day-care programs for temporary relief) (24), emotional support, and addressing social needs (18–21).

Research has identified several primary support needs, including increased time off, clear expectations for the future, practical assistance at home, health-related support, and guidance in managing emotions and concerns (8, 25). Many of these support needs involve providing the FCs with specific assistance rather than support aimed at enhancing their caregiving capacities, suggesting that FCs should be seen as co-clients and care partners (25). Nevertheless, healthcare practitioners typically adopt a more client-centered approach, prioritizing the patient’s demands, which may result in neglect of the FC’s needs for support (25, 26). Consequently, despite the endeavors of healthcare professionals, the support requirements of family caregivers frequently go unaddressed (15, 21, 27). Nonetheless, the specific unmet support needs may differ significantly among FCs and fluctuate over time. Currently, the perspectives on preferred support and burden-related experiences, positive encounters, challenges, and assistance to carers of EoL patients remain ambiguous. Previous research on family caregivers’ assistance at the EoL has predominantly focused on certain disease categories (12, 20–22, 25, 28–30) or support alternatives (24, 31). Furthermore, assistance needs and experiences about the care situation are frequently evaluated by a quantitative methodology, predominantly yielding a numerical representation of the majority’s support preferences and experiences. Nonetheless, most perspectives fail to represent the diversity in support requirements and experiences among FCs. In turn, the disparities among FCs regarding their specific assistance needs and caregiving experiences remain overlooked. In Portugal, few studies have utilized a mixed-method approach, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative approaches, to analyse this complex phenomenon from a multidimensional stance. Mixed methods research is an advantageous technique that helps strengthen the evidence in PC and EoL research. As previously stated, FCs may experience an escalating burden that jeopardizes their physical and psychological well-being, hence impairing their caregiving capabilities. Comprehending the methods to mitigate these stressors is essential for fulfilling the growing requirements for home-based care. Primary care personnel require assistance in recognizing at-risk caregivers, providing them with support and thereby preventing unnecessary hospital stays for patients. Given the growing older population, routinely evaluating caregivers’ demands is essential to identify crisis situations and notify personnel of the escalating demands on carers (32). Considering the increasing demands on community health and private agency personnel, along with the financial ramifications of prolonged examinations, any screening instrument must be straightforward to administer, concise, and, crucially, encompass priority areas for regular evaluation with FCs. Therefore, screening and triaging based on needs should be an essential component of the assessment process. Former research has highlighted the global changes in where people die, shifting toward death in the community, in line with patients’ preferences (33). In contrast, the Portuguese reality reveals a tendency to die in hospitals and lack of community PC and FCs support, a model that might not be sustainable in the future (33). Despite the extensive international evidence on the demands of caregivers, from both the caregiver and professional viewpoints (34–36), so far there is no known research from Portugal investigating the prioritization of caregiver needs in the context of EoL care from these perspectives.

Therefore, the overall aim of this study is to comprehensively assess the unmet needs of FCs in home-based PC settings and their experiences interacting with PC services, and then propose strategies and recommendations for FC advocacy in PC and foster the design of person-centered supportive interventions. The specific objectives are to:

a) characterize unmet needs of FCs of palliative patients who are cared for at home, tracking care needs, health literacy levels, social support, FC burden and risk of prolonged grief;

b) explore the profile of Portuguese FCs who care for palliative patients in a home setting, distinguishing their support needs and experiences with caregiving;

c) understand the role, impact, and support of FCs of palliative patients when interacting with PC services;

d) identify the priority indicators for inclusion in an alert assessment tool for FCs who are caring for a person who is dying at home;

e) synthesize the evidenced-based recommendations for FC advocacy in PC.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

This study will employ a multi-stage mixed-methods design (37). This methodology entails the concurrent gathering of quantitative and qualitative data within a singular investigation. This approach was chosen as it gathers diverse data to comprehend participant experiences with home-based PC. The quantitative aspect comprises a cross-sectional survey, while the qualitative part uses a descriptive qualitative method with open-ended questions to elucidate FC experiences and gather expert opinion through the Delphi method. Data integration through embedding will occur when data collection and analysis are linked at multiple points. Data from phases I and II will be used to develop a CAT measurement tool in phase III.

2.2 Study development

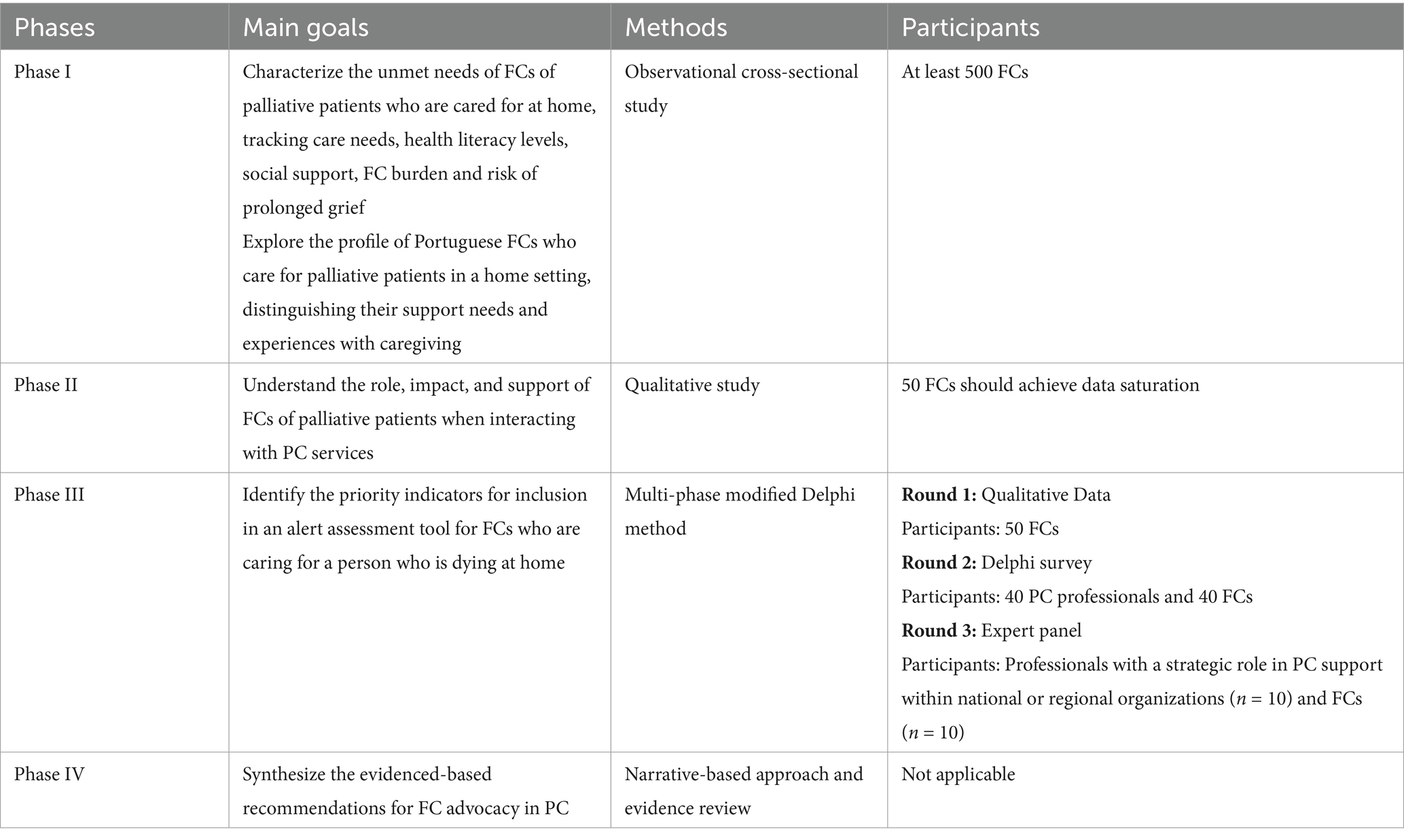

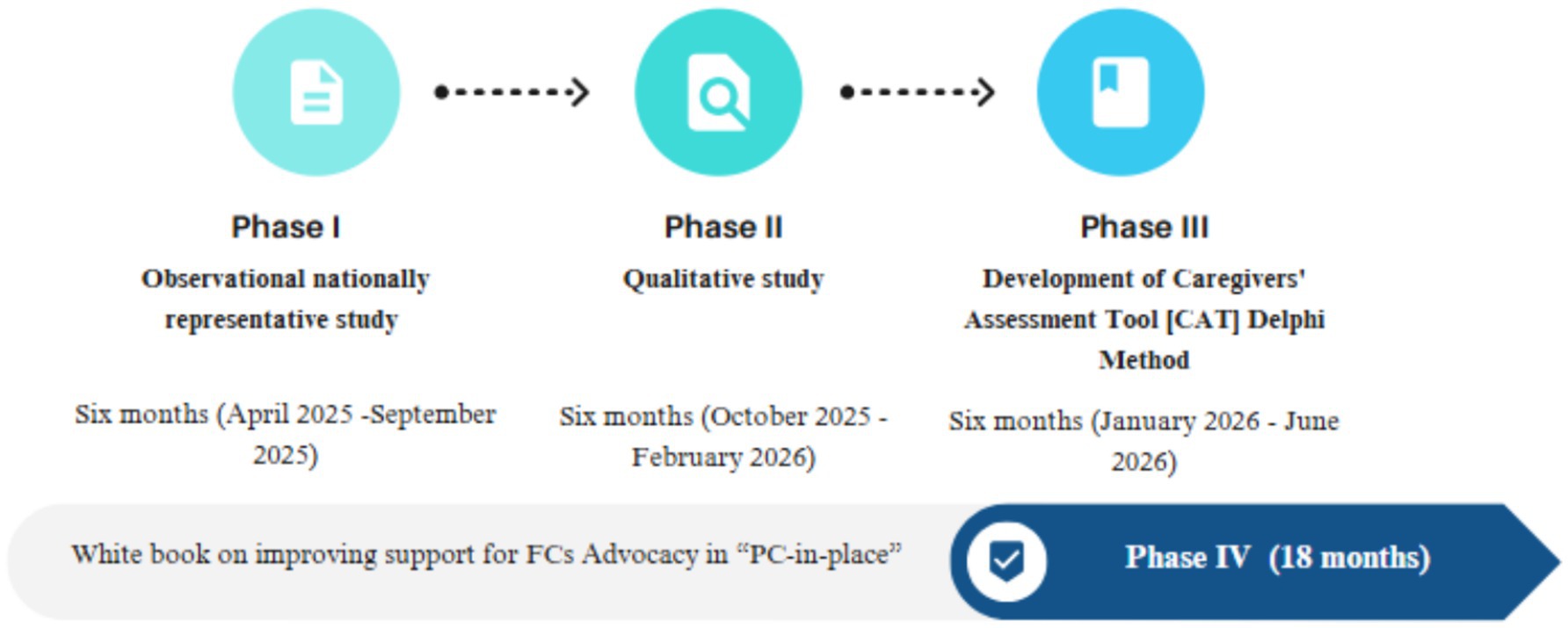

This study will be conducted in four major phases over a period of one and a half years, commencing from the date of execution in Portugal (Table 1). The research team possesses expertise in both qualitative and quantitative methodologies and holds graduate degrees in nursing (CL, AQ, and MD), psychology (AC), social work (CR), and medicine (RC). The four phases are (I) assessing FC needs and profiles; (II) assessing interactions with and access to PC services; (III) developing Caregivers’ Assessment Tool; and (IV) producing white book on improving support for FCs advocacy in “PC-in-place” (see Figure 1).

2.2.1 Phase I—observational nationally representative study (FCs’ needs and profiles)

This study will use a cross-sectional survey through telephone and in-person interviews with a large, nationally representative sample, to capture the unmet needs of users and to identify FC profiles. Inclusion criteria for the sample will be as follows: being primary FC; receiving home-based PC services; being ≥18 years old; and understanding Portuguese. FCs will be excluded if they have cognitive impairments that compromise their participation. Recruitment will be conducted according to the service list of the community support teams in PC from the Portuguese Observatory of PC. The surveys will utilize a random stratified sample of palliative family caregivers, categorized by gender, age range, and geographical area. The Strategic Development Plan for PC (2023–2024 biennium) estimates that 100,000 individuals require PC; they are supported by 64 community teams with regional coverage (38). Before data collection, a priori power analysis was performed using G*Power version 3.1.9.7 to ascertain the minimal sample size necessary for identifying a medium effect size (r = 0.30) with a two-tailed test, an α of 0.05, and a power of 0.95. This analysis revealed that at least 500 FCs are required for this study. Data will be gathered utilizing a structured questionnaire comprising six sections: (I) Sociodemographic details of the caregiver and the health status of the care recipient, including (i) the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale-revised to evaluate the severity of nine common symptoms in PC patients (39); and (ii) the Performance Palliative Scale (PPS) to estimate the survival duration of PC patients (40); (II) Health literacy levels of carers (41); (III) “Family Inventory of Needs” to measure the importance of care needs of families (42); (IV) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Support to measure the perceived adequacy of social support from three sources: family, friends and significant others (43); (V) Caregiver Burden Scale to evaluate both the objective and subjective burdens of informal caregiving, gathering data on health, social life, personal life, financial status, emotional well-being, and the nature of the caregiver’s relationship (44); (VI) Marwit Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory Short-Form to evaluate pre-death grieving (45). In terms of data analysis, we will utilize descriptive, inferential, and predictive statistics to summarize data, test hypotheses and forecast future outcomes, respectively. Data will be analyzed utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0. The STROBE checklist (46) will be utilized.

2.2.2 Phase II—qualitative study (interaction and access to PC services)

This qualitative study will explore the role, impact, and support of FCs of PC patients when interacting with PC providers. Furthermore, it is essential to identify the most effective methods for utilizing patient-level data in the creation and provision of PC. Caregiver participants will be purposively sampled (n = 50 should achieve data saturation) for face-to-face interviews. Inclusion criteria will be: (a) being primary FC; (b) receiving home-based PC services; (c) being ≥18 years old; and, (d) understanding Portuguese. Participants from the cross-sectional survey (phase 1) who provide consent will be asked to engage in a qualitative interview. Topic guides will focus on the experience of caregiving for individuals with palliative needs, existing engagement with and access to PC services, and expected clinical responses from health services, whether through in-person communication or digital technology. All interviews will be stored and analyzed via WebQDA software. A thematic analysis will be performed to delineate the conceptual framework of the principal topics derived from the interviews (47).

Some strategies will be implemented to guarantee qualitative rigor. Firstly, researcher reflexivity will be addressed throughout the research process by composing a reflective document on the researcher’s positionality that will be revisited at each study phase. Secondly, WebQDA software enhances transparency in analysis by allowing summaries or interpretations to be readily connected to the raw data. Thirdly, data from other sources will be compared to ascertain whether divergent findings emerge. Ultimately, a “thick description” will be incorporated into the final report, featuring instances of raw data (i.e., direct quotations from study participants) alongside pertinent contextual information regarding the participants (48). The research will adhere to the COREQ checklist (49).

2.2.3 Phase III—development of caregivers’ assessment tool

This phase will design an assessment instrument to ascertain caregivers’ needs during routine practice by identifying and reaching consensus on the critical areas of need. Results from phases I and II will guide the creation of an initial Caregivers’ Assessment Tool (CAT), which will be enhanced through a multi-phase modified Delphi method (50) to achieve consensus among caregivers and professionals on a prioritized list of caregiver needs. This will inform the development of an assessment tool designed for the regular evaluation of caregiver needs, while addressing practical considerations for its practical implementation. A purposive sampling technique will be employed to recruit participants at each stage of the study, consisting of existing or bereaved caregivers, as well as professionals experienced in helping caregivers throughout the study phases. All volunteers must be at least 18 years old and capable of providing consent to participate in the study. Participant experiences are crucial to guarantee a diverse array of opinions on the primary demands impacting caregivers delivering end-of-life care to those dying at home. The initial phase (R1) will concentrate on generating items for the survey, utilizing thematic analysis of data obtained from semi-structured interviews and a focus group involving a target sample of 50 adult family caregivers selected from participants of phase 1. The outcomes from phases I and II will facilitate item production. The second round (R2) will employ a systematic method to analyse data gathered from online surveys with PC professionals and FCs. Round 2 survey will comprise 40 professionals and 40 caregivers (n = 80). A third round (R3) will analyse data gathered from two groups: professionals with a strategic role in PC support within national or regional organizations (n = 10) and FCs (n = 10). This data will be utilized to further refine the final elements for inclusion in the CAT. We will employ triangulation methods to synthesize qualitative and quantitative data (51). Findings will be integrated into feedback reports, emphasizing areas of agreement and disagreement among participants. To ensure thorough reporting, we will synchronize qualitative codes with quantitative items, authenticate quantitative themes through qualitative data, and conduct contextual analysis to clarify the rationale behind quantitative ratings. We will also comprehensively document the triangulation process, including decision-making rationales and integration procedures, to enhance trustworthiness.

2.2.4 Phase IV—white book on improving support for FCs advocacy in “PC-in-place”

A White Book will be developed to synthesize evidence-based suggestions for FCs Advocacy in “PC-in-place,” drawing on outcomes from prior assignments and a vast research literature. This book will assess the contributions of FCs to home-based care and elucidate the significance of their work as a crucial resource in PC. We will delineate the problems confronting the FCs of patients with primary care needs and propose best strategies for service providers, stakeholders, and decision-makers to collaborate with these carers.

3 Discussion

A critical policy issue pertains to the establishment of egalitarian societies, wherein robustly supported access to healthcare and social systems empowers individuals and communities to actively participate in their own development and influence the 2030 Agenda through local, national, and global actions. The paucity of research on effective home-based PC has limited our ability to identify the most effective avenues for future policy and practice. To ensure QoL for palliative patients and their caregivers, compassionate-friendly care services are needed (52). By offering novel data on FC needs and the critical aspects faced when caring, the project will yield important insights about how to foster a more inclusive society. Consequently, new strategies should be developed to comprehensively assess the unmet care needs of FCs before designing and providing tailored PC services, to ensure QoL in PC.

The project’s outcomes will enrich the community’s PC while optimizing social welfare procedures. Moreover, by identifying the unmet requirements of FCs, the initiative will enhance the QoL and well-being of care recipients. Addressing the needs of FCs should improve their health and competence to care, minimizing the consumption of hospital health resources, while attending to patient preferences. Current understanding of significant FC engagement will be harmonized and sustainably executed through the participation of pertinent stakeholders. The project will provide an innovative network platform and essential resources to enhance the present welfare system response to the requirements of palliative patients and their FCs. Furthermore, it will include knowledge-driven suggestions for FC advocacy, guidance on FC educational interventions, accessible resources to be mobilized in the territory, and strategies to streamline and integrate the caregiving process. This will also diminish the waste of health and social resources. Finally, this study could be the first step in the development of a “PC-in-place” barometer that responds to concerns regarding the culture of political correctness in the practice setting and its influence on the experiences of patients, family caregivers, and staff. It will also facilitate a deeper exploration and encourage discourse around personnel matters, particularly at the team level.

The study’s main asset is that it will be the first research undertaken at the national level with representative sampling. To our knowledge, no prior research has utilized such rigorous methods, especially targeting family caregivers—a frequently neglected group. A drawback of this study is that its cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of causation regarding the relationships. Furthermore, additional environments such as nursing homes will fall outside the study scope, constraining the findings’ representativeness and transferability. Another possible limitation of the research is that it might not be applicable to locations outside of Portugal. Considering the possible impact of location-specific elements is vital when evaluating and applying the study’s conclusions. In addition, to make the most of the study’s relevance and applicability, future research should investigate how to adapt and use the findings in other contexts and cultures. Another anticipated limitation is that interview-based research relies on self-reported actions and attitudes, which can be influenced by recall and social desirability biases. To reduce social desirability bias, we will assure participants that their data will remain anonymous. Lastly, potential selection bias or logistical challenges in conducting face-to-face interviews could affect the validity and reliability of the collected data.

4 Ethics and dissemination

This study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Leiria (CE/IPLEIRIA/11/2025). Any substantial changes to the ongoing protocol will be submitted as an amendment for approval. All research members agree to adhere to the Guidelines for the Responsible Conduct of Practice according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants will be assured that all information will be kept secure and anonymous, that participation is voluntary, and that it may be retracted at any time without repercussions. Informed consent will be acquired at every stage. Volunteers will receive no compensation for their participation. Coded information will be employed in data management to provide privacy protection. Data will be preserved safely and confidentially, in compliance with institutional laws for data storage. The consent forms, data collection forms, and full transcripts will be preserved for a period of 5 years.

The key findings will be communicated via pertinent social media platforms, websites, and succinct reports to relevant entities and stakeholders. Scholarly articles will be submitted to relevant peer-reviewed journals. Additionally, public presentations will be presented at relevant national and international conferences.

5 Conclusion

This study protocol delineates strategies for collecting ample information on the needs of FCs, thereby addressing shortfalls in PC research. The study findings will provide policymakers and stakeholders with essential insights into family caregiving issues that should be prioritized in Portugal’s current strategic plan for PC development. The project has the potential to empower FCs to become relevant key stakeholders in their communities. Furthermore, it will offer knowledge-based suggestions for FC advocacy, guidance on FC educational interventions, accessible resources to be mobilized at the country level, and enhance the caregiving process to be more cohesive and less disjointed. By producing a White Book on improving support for FCs advocacy in “PC-in-place,” the project can target different publics to improve support for family carers in PC.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Leiria (CE/IPLEIRIA/11/2025). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MD: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AC: Writing – review & editing. CR: Writing – review & editing. RC: Writing – review & editing. AQ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study has received funding under the project 2023.15123.PEX “ALL ABOARD: Access family caregiving needs as a bridge for palliative care-in-place,” funded by FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. It was also supported by FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia I.P. (UIDB/05704/2020 and UIDP/05704/2020); and by the Scientific Employment Stimulus—Institutional Call—(https://doi.org/10.54499/CEECINST/00051/2018/CP1566/CT0012, accessed on 20 April 2025). The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rolão, C, and Reis-Pina, P. Palliative Care in Portugal: are we “choosing wisely”? Acta Med Port. (2024) 37:671–2. doi: 10.20344/amp.21838

2. da Silva, MM, Telles, AC, Baixinho, CL, Sá, E, Costa, A, and Henriques, M. Analyzing innovative policies and practices for palliative care in Portugal: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. (2024) 23:225. doi: 10.1186/s12904-024-01556-7

3. Ali, M, Capel, M, Jones, G, and Gazi, T. The importance of identifying preferred place of death. BMJ Support Palliat Care. (2019) 9:84–91. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000878

4. Nilsson, J, Holgersson, G, Ullenhag, G, Holmgren, M, Axelsson, B, Carlsson, T, et al. Socioeconomy as a prognostic factor for location of death in Swedish palliative cancer patients. BMC Palliat Care. (2021) 20:43. doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00736-z

5. Nysaeter, TM, Olsson, C, Sandsdalen, T, Hov, R, and Larsson, M. Family caregivers’ preferences for support when caring for a family member with cancer in late palliative phase who wish to die at home – a grounded theory study. BMC Palliat Care. (2024) 23:15. doi: 10.1186/s12904-024-01350-5

6. Ahn, S, Romo, RD, and Campbell, CL. A systematic review of interventions for family caregivers who care for patients with advanced cancer at home. Patient Educ Couns. (2020) 103:1518–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.012

7. Caetano, P, Querido, A, and Laranjeira, C. Preparedness for caregiving role and telehealth use to provide informal palliative home Care in Portugal: a qualitative study. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). (2024) 12:1915. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12191915

8. Marrazes, V, Gonçalves, L, Querido, A, and Laranjeira, C. Informal palliative Care at Home: a focus group study among professionals working in palliative Care in Portugal. Healthcare. (2025) 13:978. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13090978

9. Guerriere, D, Husain, A, Zagorski, B, Marshall, D, Seow, H, Brazil, K, et al. Predictors of caregiver burden across the home-based palliative care trajectory in Ontario, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. (2016) 24:428–38. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12219

10. De Korte-Verhoef, MC, Pasman, HRW, Schweitzer, BP, Francke, AL, Onwuteaka Philipsen, BD, and Deliens, L. Burden for family carers at the end of life; a mixed-method study of the perspectives of family carers and GPs. BMC Palliat Care. (2014) 13:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-16

11. Rumpold, T, Schur, S, Amering, M, Kirchheiner, K, Masel, E, Watzke, H, et al. Informal caregivers of advanced-stage cancer patients: every second is at risk for psychiatric morbidity. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24:1975–82. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2987-z

12. Sklenarova, H, Krümpelmann, A, Haun, MW, Friederich, HC, Huber, J, Thomas, M, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer. (2015) 121:1513–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29223

13. Bijnsdorp, FM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, BD, Boot, CRL, van der Beek, AJ, and Pasman, HRW. Caregiver’s burden at the end of life of their loved one: insights from a longitudinal qualitative study among working family caregivers. BMC Palliat Care. (2022) 21:142. doi: 10.1186/s12904-022-01031-1

14. Ateş, G, Ebenau, AF, Busa, C, Csikos, Á, Hasselaar, J, Jaspers, B, et al. “Never at ease”–family carers within integrated palliative care: a multinational, mixed method study. BMC Palliat Care. (2018) 17:39. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0291-7

15. Ornstein, KA, Kelley, AS, Bollens-Lund, E, and Wolff, JL. A national profile of end-of-life caregiving in the United States. Health Aff. (2017) 36:1184–92. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0134

16. Kent, EE, Ornstein, KA, and Dionne-Odom, JN. The family caregiving crisis meets an actual pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2020) 60:e66–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.006

17. Ewing, G, Brundle, C, Payne, S, and Grande, G. The Carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: a validation study. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2013) 46:395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.008

18. Ewing, G, and Grande, G. Development of a Carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) for end-of-life care practice at home: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. (2013) 27:244–56. doi: 10.1177/0269216312440607

19. Peterie, M, and Broom, A. Conceptualising care: critical perspectives on informal care and inequality. Soc Theory Health. (2024) 22:53–70. doi: 10.1057/s41285-023-00200-3

20. Plöthner, M, Schmidt, K, de Jong, L, Zeidler, J, and Damm, K. Needs and preferences of informal caregivers regarding outpatient care for the elderly: a systematic literature review. BMC Geriatr. (2019) 19:82. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1068-4

21. Chen, S-C, Chiou, S-C, Yu, C-J, Lee, Y-H, Liao, W-Y, Hsieh, P-Y, et al. The unmet supportive care needs—what advanced lung cancer patients’ caregivers need and related factors. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24:2999–3009. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3096-3

22. Teixeira, MJC, Abreu, W, Costa, N, and Maddocks, M. Understanding family caregivers’ needs to support relatives with advanced progressive disease at home: an ethnographic study in rural Portugal. BMC Palliat Care. (2020) 19:73. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00583-4

23. Joyce, BT, Berman, R, and Lau, DT. Formal and informal support of family caregivers managing medications for patients who receive end-of-life care at home: a cross-sectional survey of caregivers. Palliat Med. (2014) 28:1146–55. doi: 10.1177/0269216314535963

24. Guets, W, and Perrier, L. Determinants of the need for respite according to the characteristics of informal carers of elderly people at home: results from the 2015 French national survey. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:995. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06935-x

25. Aoun, SM, Toye, C, Slatyer, S, Robinson, A, and Beattie, E. A person-centred approach to family carer needs assessment and support in dementia community care in Western Australia. Health Soc Care Commun. (2018) 26:e578–86. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12575

26. Aoun, S, Deas, K, Toye, C, Ewing, G, Grande, G, and Stajduhar, K. Supporting family caregivers to identify their own needs in end-of-life care: qualitative findings from a stepped wedge cluster trial. Palliat Med. (2015) 29:508–17. doi: 10.1177/0269216314566061

27. Hashemi, M, Irajpour, A, and Taleghani, F. Caregivers needing care: the unmet needs of the family caregivers of end-of-life cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. (2018) 26:759–66. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3886-2

28. Kusi, G, Boamah Mensah, AB, Boamah Mensah, K, Dzomeku, VM, Apiribu, F, Duodu, PA, et al. The experiences of family caregivers living with breast cancer patients in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Syst Rev. (2020) 9:165. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01408-4

29. Lindeza, P, Rodrigues, M, Costa, J, Guerreiro, M, and Rosa, MM. Impact of dementia on informal care: a systematic review of family caregivers' perceptions. BMJ Support Palliat Care. (2020). doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242

30. Whitlatch, CJ, and Orsulic-Jeras, S. Meeting the informational, educational, and psychosocial support needs of persons living with dementia and their family caregivers. Gerontologist. (2018) 58:S58–73. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx162

31. Dikkers, MF, Dunning, T, and Savage, S. Information needs of family carers of people with diabetes at the end of life: a literature review. J Palliat Med. (2013) 16:1617–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0265

32. Atoyebi, O, Eng, JJ, Routhier, F, Bird, ML, and Mortenson, WB. A systematic review of systematic reviews of needs of family caregivers of older adults with dementia. Eur J Ageing. (2022) 19:381–96. doi: 10.1007/s10433-021-00680-0

33. Gomes, B, Pinheiro, MJ, Lopes, S, de Brito, M, Sarmento, VP, Lopes Ferreira, P, et al. Risk factors for hospital death in conditions needing palliative care: Nationwide population-based death certificate study. Palliat Med. (2018) 32:891–901. doi: 10.1177/0269216317743961

34. Zhu, S, Zhu, H, Zhang, X, Liu, K, Chen, Z, Yang, X, et al. Care needs of dying patients and their family caregivers in hospice and palliative care in mainland China: a meta-synthesis of qualitative and quantitative studies. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e051717. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051717

35. Ashrafizadeh, H, Gheibizadeh, M, Rassouli, M, Hajibabaee, F, and Rostami, S. Explaining Caregivers' perceptions of palliative care unmet needs in Iranian Alzheimer's patients: a qualitative study. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:707913. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.707913

36. Hasson, F, Nicholson, E, Muldrew, D, Bamidele, O, Payne, S, and McIlfatrick, S. International PC research priorities: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. (2020) 19:16. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-0520-8

37. Creswell, JW. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications (2014).

38. Comissão Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos. Strategic development plan for PC (2023–2024 biennium). Ministério da Saúde: Lisboa (2023).

39. Chang, VT, Hwang, SS, and Feuerman, M. Validation of the Edmonton symptom assessment scale. Cancer. (2000) 88:2164–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2164::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-5

40. Victoria Hospice Society (2016). Palliative performance scale (PPSv2) version 2. Victoria, BC: Victoria Hospice Society. Available online at: http://victoriahospice.com/files/attachments/2Ba1PalliativePerformanceScaleENGLISHPPS.pdf.

41. Chew, LD, Bradley, KA, and Boyko, EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. (2004) 36:588–94.

42. Areia, N, Major, S, and Relvas, A. Inventário das Necessidades Familiares (FIN – versão portuguesa) In: AP Relvas, editor. Avaliação Familiar – Vulnerabilidade, Stress e Adaptação, vol. II. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra (2016). 105–24.

43. Carvalho, S, Pinto-Gouveia, J, Pimentel, P, Maia, D, and Mota-Pereira, J. Características psicométricas da versão portuguesa da Escala Multidimensional de Suporte Social Percebido (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support - MSPSS). Psychologica. (2011) 54:331–57. doi: 10.14195/1647-8606_54_13

44. Sequeira, C. Adaptação e Validação da Escala de Sobrecarga do Cuidador de Zarit. Revista Referência II. (2010) 12:9–16.

45. Areia, N, Major, S, and Relvas, A. Inventário do Luto para os Cuidadores de Marwit-Meuser - Forma Reduzida (MMCGI-SF) In: AP Relvas, editor. Avaliação Familiar – Vulnerabilidade, Stress e Adaptação, vol. II. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra (2016). 126–45.

46. Von Elm, E, Altman, DG, Egger, M, Pocock, SJ, Gøtzsche, PC, and Vandenbroucke, JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. (2008) 61:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

47. Braun, V, and Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

48. Ponterotto, JG. Brief note on the origins, evolution, and meaning of the qualitative research concept thick description. Qual Rep. (2006) 11:538–49. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2006.1666

49. Tong, A, Sainsbury, P, and Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

50. Nasa, P, Jain, R, and Juneja, D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: how to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. (2021) 11:116–29. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.116

51. Jonsen, K, and Jehn, KA. Using triangulation to validate themes in qualitative studies. Qual Res Organ Manag. (2009) 4:123–50. doi: 10.1108/17465640910978391

Keywords: family caregivers, palliative care, needs assessment, advocacy, community support, mixed methods, Portugal

Citation: Laranjeira C, Dixe MdA, Coelho A, Reigada C, Carneiro R and Querido A (2025) The needs of family caregivers providing palliative home care in Portugal: a multi-stage mixed methods study protocol. Front. Public Health. 13:1596657. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1596657

Edited by:

Ana Pires, Universidade Atlântica, PortugalReviewed by:

María Cantero-García, Universidad a Distancia de Madrid, SpainMaria João Almeida Santos, Atlântica University, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Laranjeira, Dixe, Coelho, Reigada, Carneiro and Querido. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carlos Laranjeira, Y2FybG9zLmxhcmFuamVpcmFAaXBsZWlyaWEucHQ=

Carlos Laranjeira

Carlos Laranjeira Maria dos Anjos Dixe

Maria dos Anjos Dixe Alexandra Coelho4

Alexandra Coelho4 Ana Querido

Ana Querido