- Duke Global Health Innovation Center, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States

Market shaping activities have been increasingly used to improve access to health products, such as the advance market commitments used to increase access to the pneumococcal vaccine and COVID-19 vaccines. This paper reviewed the progress and impacts, and identified enablers and barriers of market shaping activities in the past decade. We conducted a systematic review using a structured searching strategy across five academic databases and key actors' websites for gray and white literature published in English since 2012. Two researchers independently performed screening, data extraction, and analysis. Following independent screening, 97 out of 3,006 articles were eligible for analysis. The majority of the articles were qualitative studies and published within the past 5 years. Rapid access to new products, improved availability, and reduced product cost were the most reported impacts. Barriers of market shaping were the disconnection between market shaping interventions and downstream factors, fragmentation and lack of transparency in regulatory processes, and failure to incentivize manufacturers. Enablers included taking end-to-end approaches, coordination across different actors, particularly the national stakeholders and private sector, creating transparent and predictable demand, longer time span, and flexible funding. While market shaping interventions have contributed to the improvement of access to health products, future research should generate additional quantitative evidence, comprehensive impact evaluation, and in-depth studies on the negative impacts of market shaping. Market shaping actors need to adopt definitions and frameworks, apply an ecosystem-wide lens, engage with diverse stakeholders, consider service delivery, and strengthen key capabilities.

Systematic review registration: PROSPERO: CRD42023471098, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023471098

1 Introduction

Market dynamics impact the ability of people to receive high-quality, low-cost health products and services, which ultimately affect public health outcomes. All factors involved in the supply and demand for products (the market), including manufacturing, distribution, regulatory, and provider and patient awareness, play a role in determining these outcomes. In many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), markets are insufficient and inefficient. Consequently, access to effective health products, such as vaccines, drugs, diagnostics, and devices, may be out of reach of those who need them most (1). Various market shaping interventions have been implemented to address market failures. Market shaping refers to using an intervention to address a market failure or shortcoming that compromises health outcomes such as inhibiting access to desired or essential health products and services. Several types of interventions are encompassed by the term market shaping, one example is advanced market commitments (AMCs). In an AMC, donors commit funds to guarantee the price of a health product once it is developed to provide an incentive to manufacturers to invest in research and expansion of capacity for access in LMICs. Volume guarantees are another common type of market shaping intervention where a guarantor enters into an agreement with a manufacturer and agrees to purchase a set quantity of a health product over a period of time, and in return the manufacturer lowers the price. These interventions have been used across the health sector, and across product classes, to bring new suppliers to market, lower the cost of health products, and pool demand and procurement. For example, advanced market commitments, pooled procurement, and other market shaping interventions have been deployed to accelerate access to COVID-19 commodities globally. However, this unprecedented effort has had mixed outcomes, with many of the commodities remaining inaccessible or unaffordable for many low-and-middle income countries (2). For instance, when GeneXpert (a diagnostic platform for infectious diseases) came to market, the cost was much higher than conventional testing approaches (3). Meanwhile, LMICs could not finance a switch to a new testing algorithm and modality, and with uncertain demand, manufacturers were unable to help with scale-up (3). These market failures were addressed when Unitaid and other partners negotiated an upfront payment to lower the price without waiting for sufficient volumes to lead to a price decrease (3).

While there is no consistent definition or a single widely used framework in market shaping yet, several features of market shaping have been summarized to provide a broad picture.

USAID defines market shaping as the act of intervening in a health product market to address market shortcomings such as demand and supply imbalances, and high transaction costs in low-and-middle-income countries (1). Linksbridge's Foundations of Market Shaping, describes that market shaping interventions are needed when a market shortcoming or distortion compromises health outcomes such as when market dynamics between buyers and suppliers inhibits access to desired or essential health products and services (4). Some examples of this include information asymmetry between buyers and suppliers, a lack of innovation drivers, and unequal resource distribution (4). Health product markets can fall short across different characteristics, such as information asymmetry between buyers and suppliers or a lack of innovation drivers, and market shaping interventions can span the product lifecycle (1, 4). While there is growing interest in and applications of market shaping, there is limited evidence on its impact. There is even less evidence to identify shared lessons and learnings across different products and health concerns, and from different local contexts. This paper aims to identify trends and patterns of market shaping in LMICs, assess the impacts of market shaping, and better understand the lessons, enablers, and barriers of market shaping in the past decade to inform future market shaping efforts.

2 Materials and methods

Review protocol has been registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023471098).

2.1 Scope and search strategy

There is no consensus on the definition or framework of market shaping. As described in the introduction section, we used the USAID definition as our working definition of market shaping for this study (11). Our primary focus of this study are market shaping interventions led by global or regional actors that benefit multiple countries. We acknowledge that there are market shaping interventions that have been applied at the national or subnational levels, such as pooled procurement mechanisms led by national governments, but these are not currently considered in our study. To support our research aims, we have three specific objectives for this review: objective 1—identify trends and patterns of market shaping in LMICs; objective 2—assess impacts of market shaping; and objective 3—understand lessons, enablers and barriers of market shaping.

Initial systematic search was conducted in May 2023, for both journal articles and gray literature, with an updated search performed in May 2024. The search included articles published between 2012 and 2024, a period when the majority of market shaping activities have occurred. We limited our search to English language. Additionally, we performed a cross check on the references of included articles, and we obtained articles through internal references.

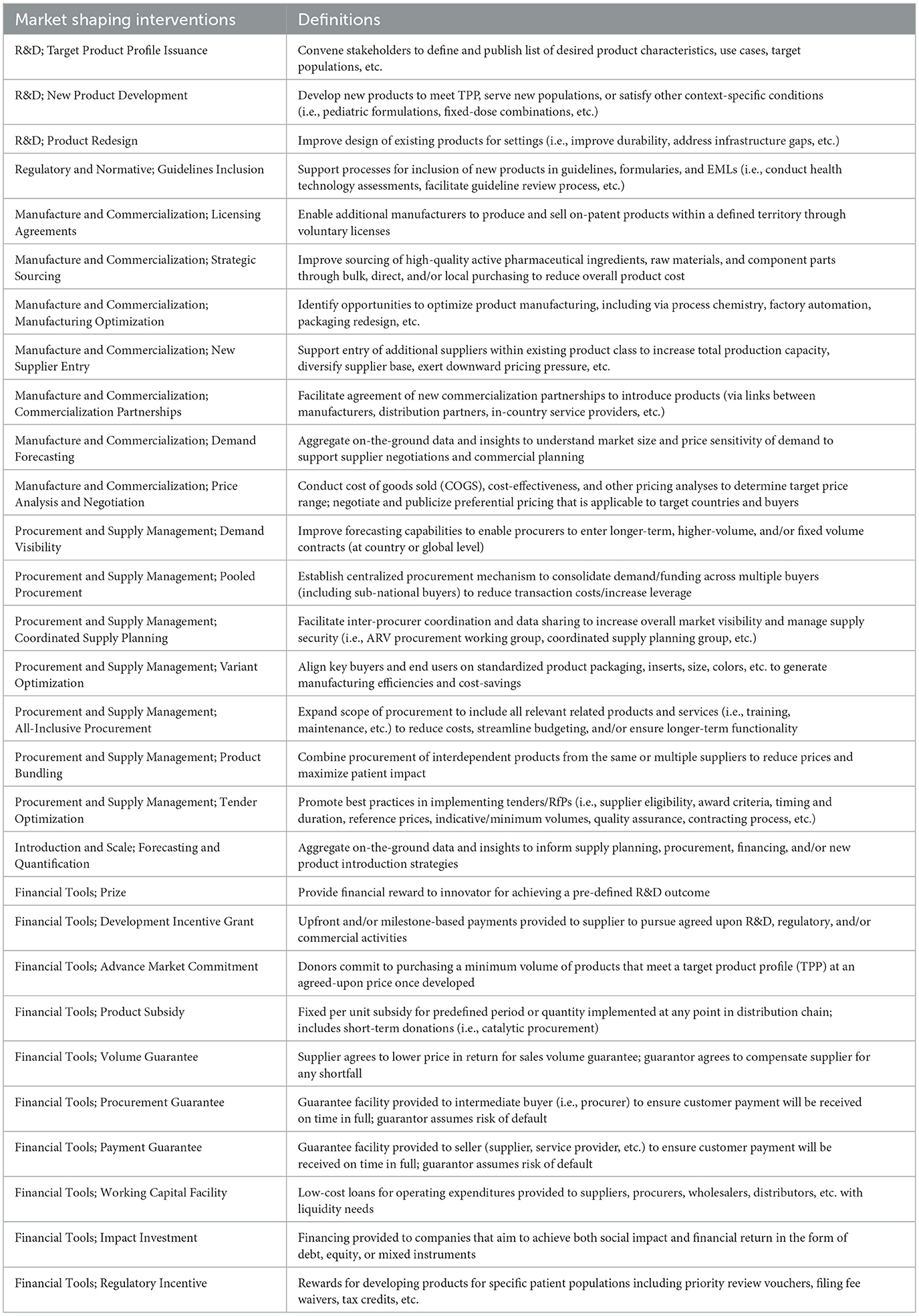

For journal articles, we performed searches in PubMed, Cochrane, EMBASE, Scopus, and Global Health databases. Databases were decided with input from a librarian specialized in global health. Our search strategy used a series of key terms clustered around three areas in title/abstract/keywords: (1) market shaping (Table 1 provides examples and definitions of specific interventions that are fall under the field of market shaping), (2) health products, and (3) progress. Search string was created using Boolean operators, such that all terms within a given area are connected by an “OR” operator, and areas are connected to one another with an “AND” operator (full searching strategy and examples in Supplementary material S1). We performed a pilot search in PubMed to refine our searching string.

Table 1. Examples of different market shaping interventions (5).

We searched gray literature with Google advance search (https://www.google.com/advanced_search). We first identified a list of key actors involved in market shaping. We then ran an advanced search on all key market shaping organizations using market shaping-related strings adapted from academic database searching to identify PDF files, including major market shaping reports and other published materials (see Supplementary material S1). We manually screened and included up to five relevant documents from each organization (key market shaping organization list and searching results in Supplementary material S2).

2.2 Study selection

Search results were imported into Covidence for independent screening by two reviewers. First, the title and abstract were screened and the full-text followed. Excluded articles were recorded with an explanation for exclusion. Any inconsistencies among the reviewers were settled by discussion and resolved with final consensus.

Inclusion criteria are: (1) Population: human; no age limit; in specific LMIC(s), or LMIC(s) is included as part of a global or multiple countries study; (2) Intervention: market shaping activities including but not limited to those listed in Table 1; (3) Outcome: cost; availability/supply; uptake/demand; quality; sustainability; unintended consequence; health outputs; health impact; quality data, analytics and institutional capacity to support effective market performance, strategy planning and execution; innovation; domestic manufacture; (4) Study type: observational/experimental/qualitative/systematic review; for systematic review, references were checked to avoid duplicate and evaluate if any of the cited articles were eligible to be included; and (5) Address at least one of our research questions. LMICs were defined based on the World Bank Income Classification list.

Exclusion criteria are: (1) Does not address any of our research questions; (2) Not a market shaping intervention; (3) National, subnational study; (4) Incorrect study design (clinical trial, cross-sectional survey, etc.); and (5) Not drug, device, diagnostic or vaccine. As mentioned earlier, there is no clear, widely accepted boundary between global market shaping interventions and those at a national level. To operationalize this review, the scope was limited to the global and regional level.

2.3 Quality assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 was used for quality assessment. The MMAT can be used to appraise the quality of empirical studies, which encompasses the majority of study methodologies included in this review. The MMAT features seven questions that allows the appraisal of most common types of study methodologies and design in a comparable way. Studies are scored out of five based on specific criteria for each study type. A score of 5/5 represents 100% of quality criteria have been met, 4/5 represents 80% of quality criteria have been met, and so on.

2.4 Data synthesis and analysis

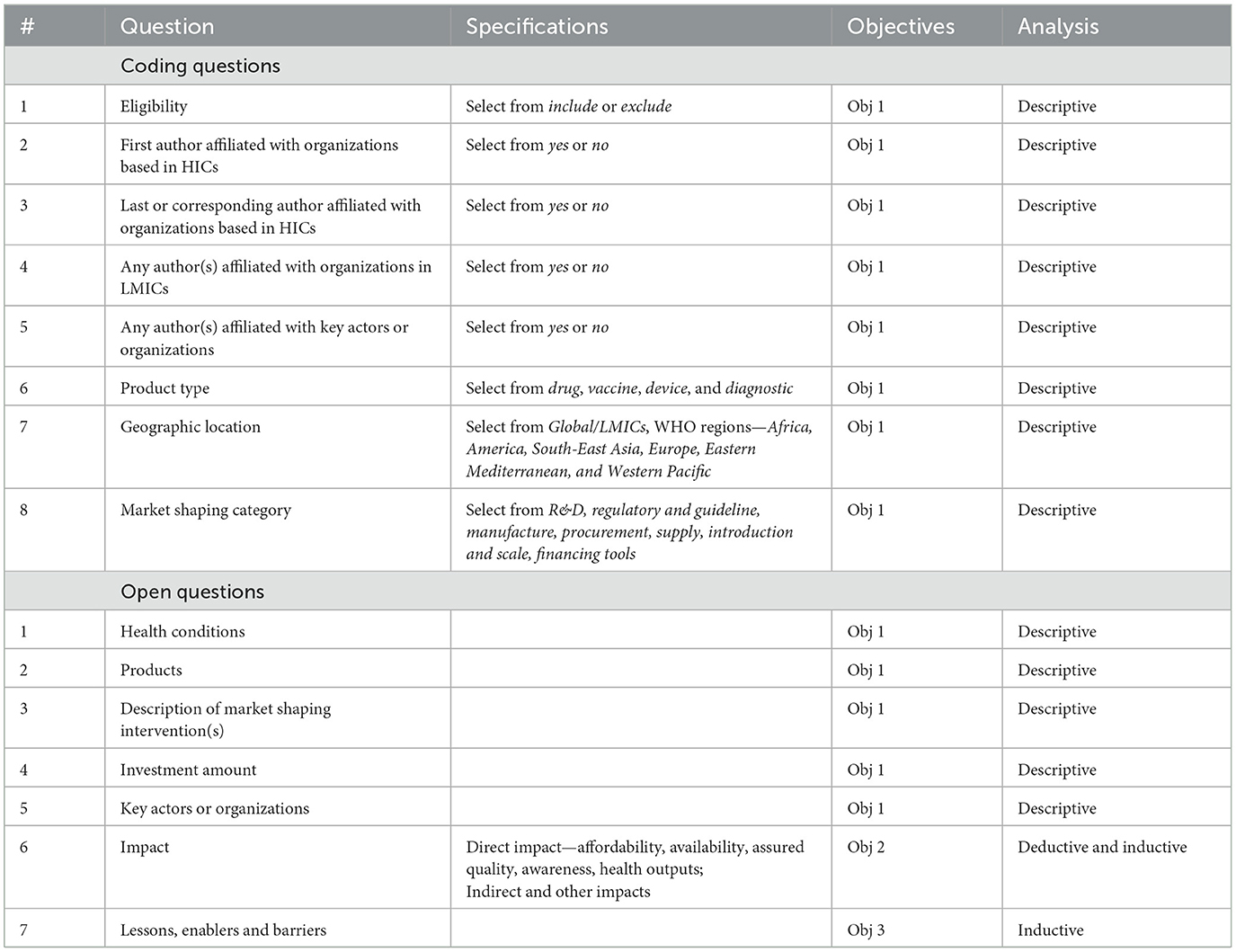

Included articles were exported from Covidence and two researchers performed data extraction with a structured data extraction template consisting of 7 coding questions and 7 descriptive questions to aid analysis (Table 2).

Descriptive analysis was applied to all questions addressing objective 1. For objective 2, we attempted to organize impact into several categories where deductive analysis was performed. However, under each impact category, we performed inductive analysis to capture the emerging themes and patterns from the literature. For objective 3, we performed inductive content analysis which enables the analysis to be driven by the emerging themes and concepts from the literature. When developing the codebook, one experienced researcher developed the first round of the codebook which was then iterated on with the larger research team. A second reviewer then coded the articles, and discussed any challenges with the team. The majority of articles included were qualitative or mixed methods, and missing data was not a concern with this study.

3 Results

3.1 Description of included articles

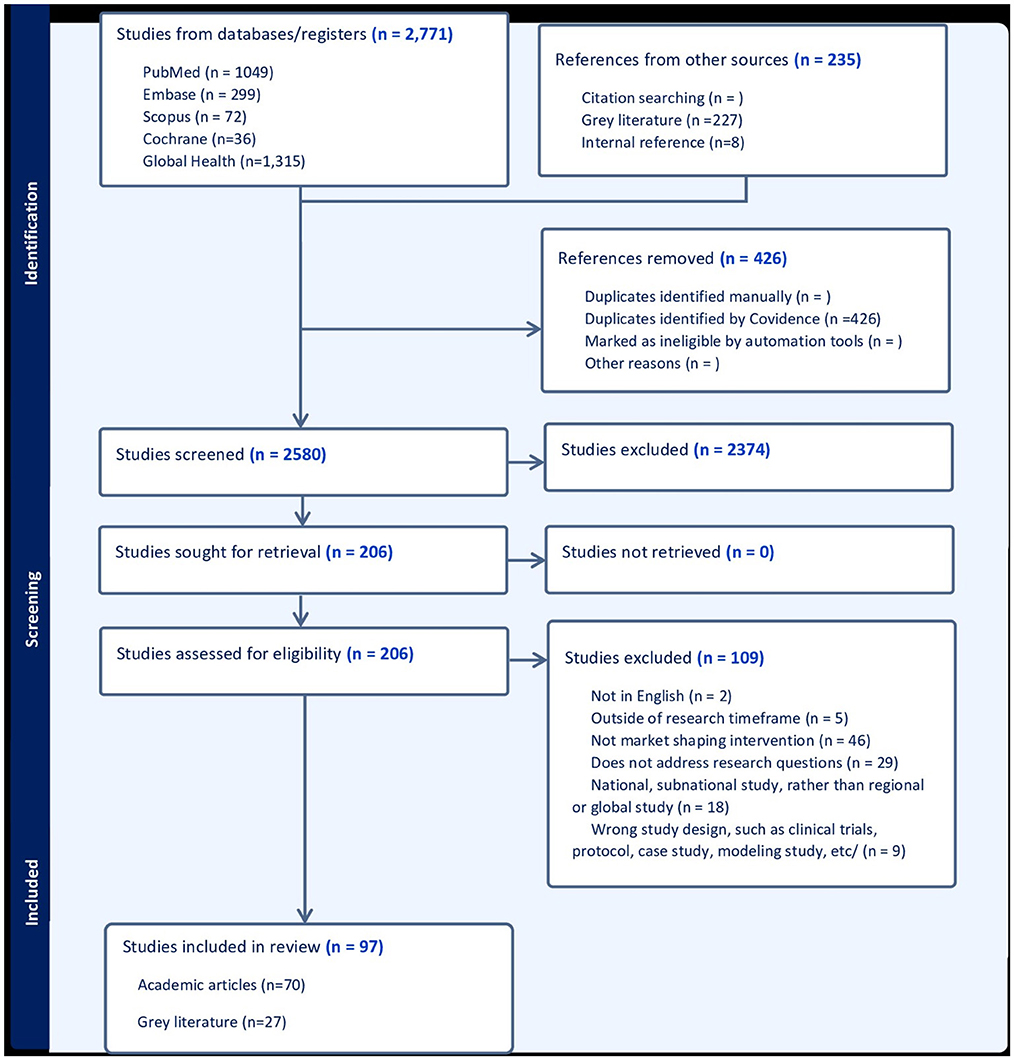

The search yielded 3,006 articles and following independent screening, 97 eligible studies were included into the analysis, among which 70 were published articles and 27 were gray literature (Figure 1) (1, 5–100). Of the included studies, there were 62 qualitative studies, 20 quantitative articles, 14 mixed methods studies, and one systematic review. The 70 journal articles were published by 50 different journals, and the most frequently used included five from Vaccines and four from BMJ Global Health, and four from the American Journal of Tropical Medicine. The gray literature documents spanned various organizations including Unitaid, PATH, Gavi and the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI).

Two-thirds of the included articles were published in or after 2018 (Supplementary Figure S1a). A majority of the authors were affiliated with institutions based in high-income countries; only 21 out of 70 (30%) academic articles, and three out of the 27 (11.1%) gray literature documents have authors from LMICs. The key market shaping organizations (see Supplementary material S2 for full list of key organizations) contributed to 14 (20%) academic and 26 (96.3%) gray literature articles. Ninety six articles are assessed with MMAT while MMAT is not able to assess one systematic review. The quality assessment for each article can be found in Supplementary material S4. The 62 qualitative studies averagely scored 4.03 (out of 5). The 20 quantitative articles had an average quality score of 4.80/5, and the average quality scores of the 14 mixed methods studies were 4.54/5. The high quality of included articles helped to guide the descriptive synthesis of results and strengthen the reliability of these findings.

3.2 Trends and patterns of market shaping in LMICs in the past decade

Almost half of the market shaping literature focused on drugs (Supplementary Figure S1b). A majority (72/97, 74.2%) of the studies reported market shaping at global level, followed by 16 (16.5%) articles solely from the Africa region, and seven (7.2%) from Southeast Asia (Supplementary Figure S1c). Market shaping interventions addressing manufacturing (33), R&D (23), and procurement (25) were the most reported in articles (Supplementary Figure S1d). Infectious diseases (69/97, 71.1%), were the most reported health conditions receiving market shaping (Supplementary Figure S1e), with malaria, HIV, TB, and neglected tropical diseases (excluding malaria) as the top reported diseases (Supplementary Figure S1f).

We identified the following 11 key market shaping actors or organizations, that have been actively included in the design, implementation, and evaluation of market shaping interventions. These key actors were mentioned in two-thirds of the included articles (64/97, 66%): World Health Organization (WHO), Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (US FDA), Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Unitaid, Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), The Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), PATH, Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) and Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

3.3 The impact of market shaping on global health

3.3.1 Impact measurement

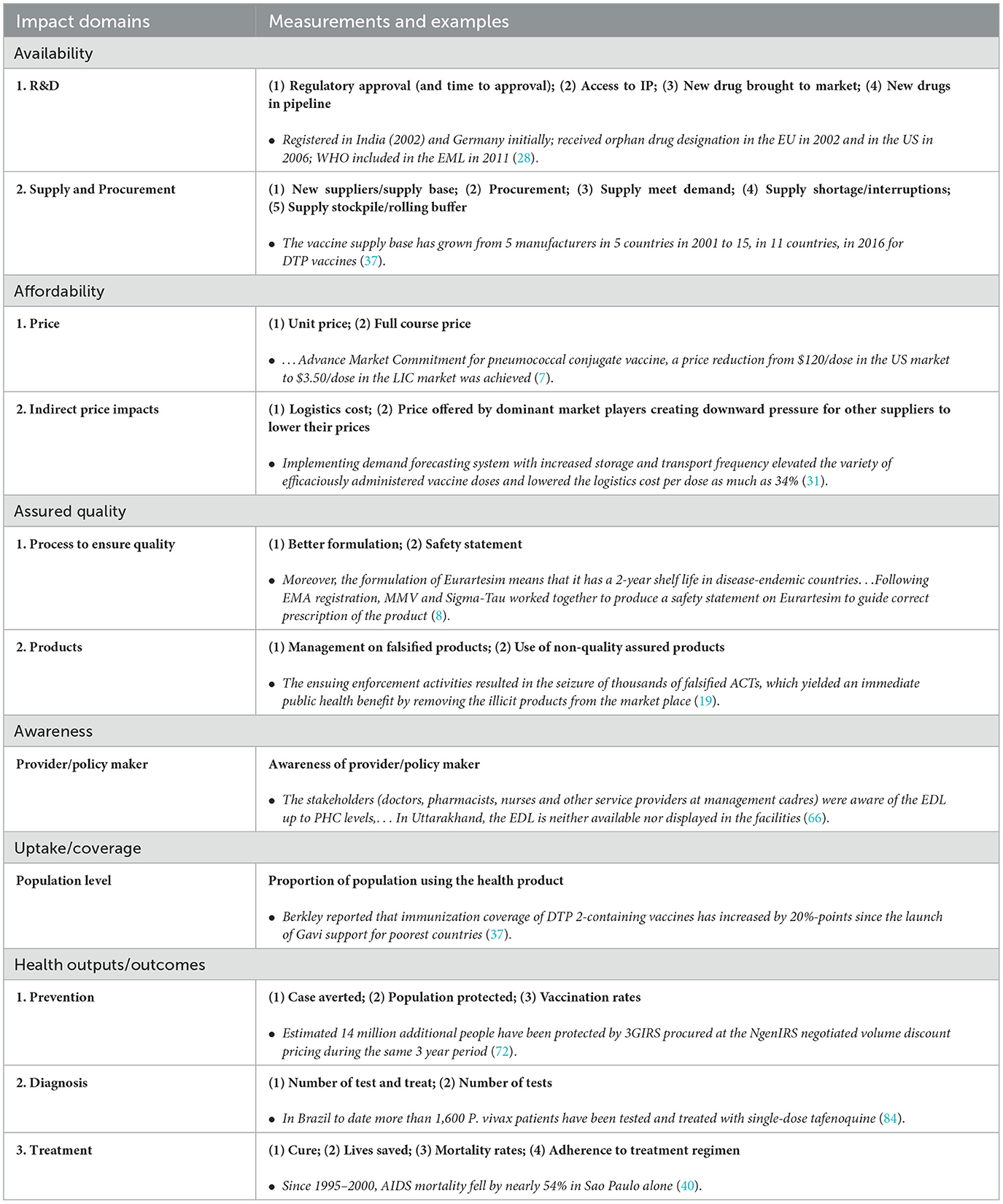

The aim of the impact measurement section is to provide an overall assessment and highlight gaps in evaluation and indicators used. Various impact measurements have been used in literature. The most frequently reported impact domains are availability (53/97, 54.6%) and affordability (24/83, 24.7%). There was less focus on quality (9), awareness (7) or uptake/coverage (7). Among all 97 articles, only 15 (15.5%) articles reported three or more impact domains.

However, a variety of measurements are used even under the same impact domain (Table 3). For example, when articles reported “availability”-related impact, they measured R&D/regulatory aspects, i.e., new products brought to market and additional products in the R&D pipeline, and the supply and procurement level availabilities, i.e., number of suppliers, quantity of procurement or purchase (32, 72). No retail level availability, such as at pharmacies or the final point of service, has been reported. The most reported indicator for affordability was unit price, which was normally compared with the price before market shaping to illustrate the change (7, 54). Only one article reported the full course cost of treatment, and compared the cost across different countries (9). However, no article links price with capacity to pay (such as GDP, salary, etc.).

For less- reported impact domains, the measurement of impact is less comprehensive. For example, a few articles measure the impact of market shaping on the awareness of providers and policy makers but only one article has reported on the awareness of patients or end users (27, 43, 66, 91). In contrast, service coverage/uptake was mostly measured at the patient level, while only one article reported policy coverage (37, 85, 86, 100).

Indirect impacts were also reported in various ways, including reduced vaccine wastage as an impact of market shaping for cold chain equipment, south-south technology transfer, and capacity building (10, 23, 36).

3.3.2 Observed impact of different market shaping interventions

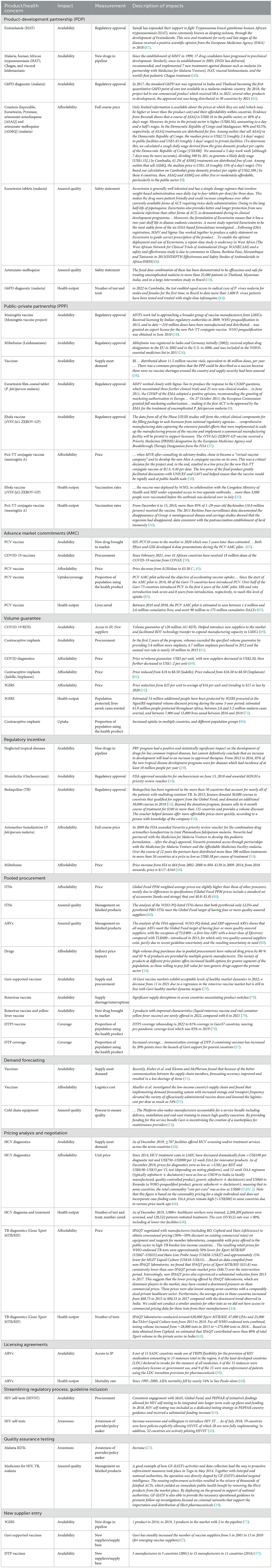

Table 4 lists the specific impact metrics of market shaping interventions that were reported across all included articles. The reported impact metrics have been organized based on the type of market shaping intervention, such as those highlighted below.

Product Development and Public-Private Partnerships have been reported to increase new drugs in the pipeline, facilitate regulatory approval of new health products, reduce prices, and improve health outcomes (Table 4).

Volume Guarantees have been observed to increase the number of manufacturers in the market and purchase quantities, and reduce price (Table 4).

Pooled Procurement was found to increase the number of vaccine manufacturers, create markets where supply meets demand, reduce price, and increase vaccination coverage (Table 4). Other impacts observed from pooled procurement mechanisms include an increased unit price due to required item specifications, creation of a maintenance marketplace for quality assurance of cold-chain equipment, and meeting a sufficient number of quality-assured suppliers (Table 4).

Advance Market Commitments (AMC) increased vaccine doses available to countries and enabled price reductions (Table 4). An external evaluation of the Gavi pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) AMC found insufficient evidence of accelerating R&D and ineffectiveness at driving price competition, but determined success at driving presentation innovation with the introduction of multi-dose vials, increasing supply due to predictable demand, and increasing vaccine uptake and coverage (Table 4) (85).

Regulatory Incentives, such as the priority review voucher, were found to facilitate new drug registrations, new drug approvals, and price reductions, though one article reported a price increase (Table 4) (28).

4 Lessons, enablers, and barriers

4.1 Key barriers affecting market shaping interventions

Many articles mentioned downstream factors as a barrier to market shaping, including health service delivery (both in public and private sector) and health seeking behavior of target population, as they have often been disconnected from market shaping efforts. Health system capacities must be built to ensure access to health products and services provided through market shaping. One article referenced challenges around country political decisions and capability, “targets were developed with the assumption that the country had the ability and the capacity to implement the vaccination plan without commensurate support and resources…political considerations often overshadowed the supply chain considerations.” (92). One article discussed how health staff capacity is a barrier, “as VL [visceral leishmaniasis] usually clusters in a few and generally remote regions of a country, policy-makers in the capital lack awareness of the disease…Clinical and diagnostic skills are equally concentrated in towns and not freely available in the VL affected areas. Capacity strengthening is jeopardized by the high turnover of health staff, both in clinical duties and in control programs.” (45). Another article discussed health system barriers at multiple levels that has limited uptake, “several barriers limit expanded use of GRT in LMICs, including high capital investment and test costs, limited molecular laboratory infrastructure, lack of skilled staff, and need for complex cold-chain sample logistics.” (22).

Another important downstream factor is the private sector which contributes substantially to the service delivery in many LMICs. One article referenced “the inclusion of private and public sector facilities in DSF schemes is one mechanism to encourage market competition and improve institutional capacity to deliver drugs…Another consideration is the sustainability of DSF programs reliant on donors for user incentives. Market segmenting can develop the total market by shifting paying customers to the private sector. For example, marketing campaigns could encourage private facility utilization among women, developing the total market and aiding in long term sustainability.” (16). The private sector also needs to be considered for market shaping as they can be another point where substandard or falsified products enter the market particularly in health systems where end-users often choose between the private and public sectors for care.

Fragmentation and lack of transparency in regulatory processes have also been identified as key barriers for market shaping. Registering products in multiple countries is often time-intensive, and costly for manufacturers to submit registration dossiers to individual countries that may take years to be approved. WHO PQ can be beneficial for improving access to products, but it does not replace regional and national regulatory processes. One article described, “Despite this progress toward international approvals, manufacturers remain concerned that in some countries the regulatory process remains opaque, the responsible authorities for the registration of HIVST products are still unclear, and even with WHO PQ, in-country validation and registration are still required. These complications add to the cost of doing business for manufacturers and threaten the sustainability of affordable prices for HIVST.” (43). Harmonization of regulation procedures across countries and more transparency of the process would help decrease the cost of registration requirements.

Additionally, access to intellectual property is another hurdle to market shaping and can impede R&D, innovation, access to certain products, and create monopolies in the market. Investing in and facilitating technology transfer and the licensing of intellectual property, through voluntary licensing or other means, would enable generic manufacturers to enter the market and provide low-cost products to LMICs.

A lack of understanding of commercial partners' incentives and what they view as barriers to market entry was another critical barrier. For market shaping to be successful, competitive markets with multiple product manufacturers would enable sustainable supply and lowered prices. However, introducing new manufacturers may impact financial sustainability amongst the commercial actors due to limited resources. Commercial partners can have challenges prioritizing product candidates for development and products with lower profit margins, which are often the target of market shaping. These products may require additional interventions to be feasible as reported in one article, “the low-cost design of the FTS was unique to its product line and required its own production run. With competition from other, much higher volume tests for infections such as influenza and HIV, Alere struggled to schedule production of low volume, one-off orders of the FTS, leading to long delays. In addition, the BinaxNOW card test was still available and being used by LF programs. A solution was needed to facilitate the transition to the FTS in country programs and streamline the ordering, production, and shipment process at Alere.” (67). Market shaping interventions would be more effective through creating sustainable incentives to attract and retain multiple and diverse manufacturers.

4.2 Key enablers for effective market shaping

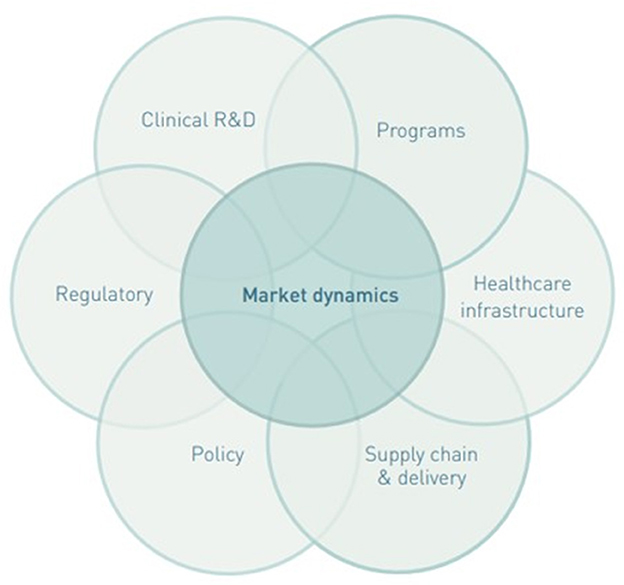

Taking an ecosystem approach to market shaping, by focusing on the continuum across the product and delivery value chain, was an important lesson learned across several articles. A product needs to go through the value chain from R&D, regulatory approval, market entry, procurement, and delivery, to reach the target population (1). The market shaping ecosystem consists of numerous actors from private manufacturers and market shaping organizations to national governments leading to an expanded field of practitioners with overlapping scope along the value chain (Figure 2) (4). To achieve impacts and create a healthy market, actors needed to have vision along the value chain as highlighted in one article, “wrongfully assumed that the transition would be smooth: just replacing the card test with the FTS in LF programs did not ensure rapid uptake by country LF programs. These programs were not familiar with the new FTS and they were reluctant to change to a diagnostic with different performance characteristics.” (22). Therefore, additional funding for in-country interventions, such as demand generation activities, may be needed to ensure uptake of health products by the end-user. One article found that “multifaceted demand generation approaches probably improve adoption, coverage, and sustainability of modern methods used…the success of implementing these strategies include users knowledge about family planning methods, the availability of modern methods, and the accessibility to services.” (91). For bundled products, like those used in test-and-treat activities such as malaria diagnostics and subsequent treatment, market shaping needs to consider both products to be effective. One article described “a unique agreement whereby drug-donating companies agreed to support purchase of the diagnostic tests needed to monitor and evaluate the programs they support through their drug donations and other contributions,” highlighting the importance of understanding bundled products when implementing a market shaping intervention (67).

Figure 2. Factors in several overlapping systems that can affect product access (4).

Within the whole ecosystem, market shaping interventions implemented for some products might affect others due to limited funding and competing priorities. For example, for countries with limited resources, they might choose to provide insulin rather than test strips. Without addressing the overall budget limitation, market shaping interventions on the test strips would not succeed.

Partnerships and coordination across different organizations such as multilateral organizations, government agencies, academic institutions, and private sector actors, are key enablers for all spectrum of market shaping efforts. Coordinating efforts across all partners involved in market shaping can identify market failures where market shaping is needed, mobilize different resources and capacity, limit duplicated efforts and improve efficiency. One article notes, “Siloed introduction efforts may also contribute to product introduction fatigue among stakeholders at the country level. Moving forward, a key question is how to balance cross-method coordination with method-specific considerations.” (68). Similarly, at disease or therapeutic area levels, engagement across global, regional, and national stakeholders early in planning can further help with aligning all partners to feasible strategic goals. One article reported, “this experience demonstrated the value of a public–private partnership for product development of new public health tools with little to no commercial or private market because it was driven by champions from the disease community, the commercial partner, and external donors. The partnership…successfully brought together disease expertise with technical diagnostic development expertise to produce a new monitoring tool which met the performance and field-ready characteristics needed to support LF elimination efforts.” (67). Regular communication between all partners involved in a market shaping interventions is key for aligning partners on their roles and responsibilities, and addressing challenges as they arise.

Transparent and predictable demand is a pre-condition for many market shaping interventions such as pooled procurement and volume guarantees. By pooling demand from fragmented country markets, demand becomes more predictable and stable. With predictable demand, manufacturers are encouraged to enter markets and limit stockouts, which could help lower prices for commodities and accelerate uptake of new products. One article highlighted a plan to develop two types of demand forecasts for better transparency between market actors, “Gavi helps improve demand visibility for manufacturers…This increased information transparency is critical for manufacturers to understand growth expectations and desired products to plan production,” and how both short-term and long-term demand forecasts should be regularly communicated to manufacturers so they can better understand growth expectations to better plan production which is critical to creating a healthy market (23). Another determinant of predictable demand is the capacity of the health system to provide access to the product. One article highlighted “A further limitation requires that payers be able to accurately predict the number of patients likely to engage in treatment to determine a price point. This requires resources and infrastructure not available in most low-income countries.” (58).

Longer strategic planning cycles for market shaping activities can enable greater awareness of the time needed to see impact from market shaping interventions, which may be longer than expected. One article touches on the slow progress from approval of a new vaccine to uptake in three countries, “following phase 3 trial results in 2014, the European Medicines Agency issued a positive scientific opinion for RTS,S malaria vaccine in 2015 and WHO recommended pilot implementation to assess the feasibility of administering four doses of required vaccine in children… It took, however, four years for the world's first malaria vaccine from the demonstration of RTS,S partial protection against malaria in young children before implementation in three sub-Saharan African countries.” (61).

In cases where market shaping interventions have succeeded, there has been flexible funding or significant contributions from global donors. One article reported on the significant investments by Unitaid, BMGF, and other partners that enabled the price of OraSure to be reduced to US$2 (43). Another article reported on donor funding that extended beyond commodity procurement and allowed for free or heavily subsidized delivery of contraceptive implants (85).

5 Discussion

This systematic review aims to describe the evolving pattern and impact of market shaping over the last decade, to identify enablers and barriers to effective market shaping, drawing insights from an extensive collection of published articles and gray literature. However, the majority of articles were published in recent years making it difficult to evaluate larger trends in the field over the last decade. To our best knowledge, this is the only study that synthesis the evidence of a wide range of market shaping interventions on different types of products. Market shaping is an emerging area of interest with various research gaps. Most existing studies generated qualitative evidence, underscoring a pressing need for more quantitative research. Notably, the landscape of market shaping research at global and regional level is currently dominated by actors from high-income countries and a select group of organizations. Many market shaping interventions in the past decade have been driven by donor organization priorities, including priority geographies, which may explain some of the underrepresentation of some global regions. Strikingly, LMICs, the primary target clients and beneficiaries of most market shaping activities, have been largely absent in the market shaping research. This trend reflects broader epistemic imbalances where research in LMICs is often led by global organizations or research institutions in high-income countries. Research on market shaping should be more inclusive, channeling and amplifying voices from LMICs, and explore the impact of market shaping at the national and subnational levels. The included studies disproportionally concentrated on products like drugs and vaccines, predominantly addressing infectious diseases. Other critical areas with different market dynamics call for more evidence such as non-communicable diseases, diagnostic tests, and medical devices, which were underrepresented in the included literature. For example, large upfront investment is needed for medical devices, which is distinct compared to drugs or vaccines. Accordingly, the market shaping for devices might apply different market mechanisms and strategies. Similarly, certain health conditions, such as reproductive and family planning, are intrinsically linked to users' preferences and behavior changes. Addressing market issues in those areas call for additional considerations in the design, implementation and evaluation of market shaping interventions.

The progress of market shaping has been impeded by challenges in impact evaluation and lack of evidence. Currently, impact is not comprehensively or systematically measured, or consistently reported in public domains. Moreover, proxies or intermediary measurements are widely used, while the impact on end-users remains markedly underreported. Existing measurements or approaches are unable to reflect the market dynamics and the evolution of market shaping over the longer term. Herein, it is challenging to attribute outcomes directly to market shaping efforts. Additionally, the majority of included articles were qualitative or descriptive, further limiting the strength of evidence for causal impact. The lack of rigorous quantitative data and causal evaluations in this field should be addressed to enable more critical appraisal of both the positive and unintended impacts of market shaping. A standardized approach to effectively illustrate the value of market shaping is missing, which is much needed to advocate for increased investment and support for such endeavors. A holistic approach should be developed and applied to guide impact evaluation, comprehensively revealing the short-term and long-term impacts of market shaping. Furthermore, in-depth studies examining potential negative impacts and deriving valuable lessons are vital. Market shaping actors are strongly encouraged to enhance knowledge sharing in public domains. Improving the evidence and evaluation could identify and prioritize the most effective and efficient interventions, and potentially unlock more resources for market shaping.

Moving forward, we draw several key recommendations from the existing evidence. First, there is an imperative need to adopt a shared market shaping framework across organizations that implement market shaping interventions. It could serve as foundation and common language for consistent and comparable data and insights, enhance collaborations and partnerships, and align the efforts and strategic goals of diverse stakeholders. Measuring affordability before and after an intervention, and changes in availability of health products could be used as priority benchmarks for evaluation efforts as both of these metrics were reported by a majority of included articles. Standardizing the metrics tracked (e.g., all interventions track unit price before and after) would provide a better opportunity to compare across a variety of market shaping interventions. Addressing enduring bottlenecks to market shaping across product categories and disease areas is crucial, underpinned by access to intellectual property and technology transfer, regulatory support, review and authorization, sustainable incentives for manufacturers, and improvements in demand and supply predictability and coordination. The design and implementation of market shaping initiatives should incorporate end-to-end planning, coordination and capacity building.

Early engagement from market shaping organizations with country ministries of health and diverse local private sector actors could better inform the design and implementation of market shaping interventions. Downstream factors, such as service delivery and health seeking behaviors, are pivotal for access to health products yet unfortunately are too often disconnected from many market shaping interventions. More efforts, including information on service uptake and engagement with health systems and providers, should be placed to market shaping efforts. Finally, creating an enabling environment, characterized by proper time frames and sustainable funding, will be instrumental in ensuring the success and sustainability of market shaping endeavors.

It is important to acknowledge and address several limitations inherent in our study. First, market shaping is a relatively nascent field lacking a clear and consistent definition, established framework, theory, or standardized terminology. Despite our searching strategy involving inputs from a librarian, global health researchers, and market shaping stakeholders, it is likely that some relevant articles may have been missed including those that may have been written in languages other than English. Second, our search of gray literature was limited to up to five articles per organization, and operationalized based on a set of organizations actively involved in market shaping, potentially overlooking emerging, non-traditional, or narrowly specialized actors. Third, our study is susceptible to publication bias, given that nearly all reported impacts of market shaping were positive. Lastly, we acknowledge that published articles and gray literature represent only a fraction of existing market shaping evidence. Potential valuable insights from grant reports, project evaluations, and other non-public domains were not included in this study. Additionally, COVID-19 has likely influenced the field, and at the time of the literature search there were limited evaluation studies examining market shaping's role in pandemic response. Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable evidence shedding light on the practice of market shaping.

6 Conclusion

Market shaping interventions have had many positive impacts on access to health products across availability, affordability, awareness, assured quality, and uptake and coverage. In some instances, health outcomes were able to be seen as a result of market shaping interventions such as the estimated lives saved resulting from the pneumococcal vaccine advance market commitment. However, across all market shaping interventions examined in this review, impact was inconsistently measured using a number of metrics such as unit price, new regulatory approval, and number of suppliers among many others which makes it difficult to compare across interventions. Future research should incorporate inputs from authors in low- and middle-income countries and consist of comprehensive program and impact evaluation, cost evaluations, and in-depth studies on the negative impacts of market shaping to better inform the development and implementation of market shaping interventions.

To enhance market shaping in the future, key stakeholders need to adopt shared definitions and frameworks for market shaping to align efforts of various actors; market shaping design and implementation should apply an ecosystem-wide lens, engage with countries and diverse local private sector actors earlier, and put more considerations on service delivery and health seeking behaviors. Key capabilities for market shaping, such as demand forecasting and others, need to be strengthened. Streamlined regulatory processes and stronger enabling environments are needed to ensure the success and sustainability of market shaping endeavors.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

WM: Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. KO: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. EU: Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. KU: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This paper was part of the project “Foundations of Market Shaping” funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our appreciation to Hannah Rozear (Duke Librarian) in providing advice for the searching strategy. We appreciate Linksbridge, CHAI, and the project's Advisory Council for their support in conceptualizing and providing feedback on the analysis. We acknowledge the contribution of Sathvika Gandavarapu (Duke undergraduate student) in performing the original literature search, and Victoria Hsiung and Rianna Cooke for data extraction.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1614471/full#supplementary-material

References

2. World Health Organization. The ACT-Accelerator: Two Years of Impact (2022). Available online at: file:///C:/Users/keo25/Downloads/The-ACT-Accelerator-Two-years-of-impact.pdf (Accessed July 24, 2025).

3. Dalberg. UNITAID End-of-Project Evaluation: TB GeneXpert—Scaling Up Access to Contemporary Diagnostics for TB (2017). Available online at: https://unitaid.org/assets/TB-Xpert-Evaluation_Report-_Final.pdf (Accessed July 24, 2025).

4. Linksbridge. Foundations of Market Shaping: Fundamental Concepts and Best Practices for Successful Global Health Market Shaping (2024). Available online at: https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/a5339b60-f80c-4866-beaf-021709171daf/20240403_FMS_online%20version.pdf (Accessed October 17, 2024).

5. Clinton Health Access Initiative. CHAI Market Shaping Framework (2024). Available online at: https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/CHAI-Market-Shaping-Framework-Feb2024.pdf (Accessed March 1, 2024).

6. Camponeschi G, Fast J, Gauval M, Guerra K, Moore M, Ravinutala S, et al. An overview of the antiretroviral market. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. (2013) 8:535–43. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000012

7. Gilchrist SA, Nanni A. Lessons learned in shaping vaccine markets in low-income countries: a review of the vaccine market segment supported by the GAVI Alliance. Health Policy Plan. (2013) 28:838–46. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs123

8. Ubben D, Poll EM. MMV in partnership: the Eurartesim® experience. Malar J. (2013) 12:211. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-211

9. Pratt B, Loff B. Linking research to global health equity: the contribution of product development partnerships to access to medicines and research capacity building. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:1968–78. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301341

10. Wells S, Diap G, Kiechel JR. The story of artesunate-mefloquine (ASMQ), innovative partnerships in drug development: case study. Malar J. (2013) 12:68. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-68

11. Nakakeeto ON, Elliott BV. Antiretrovirals for low income countries: an analysis of the commercial viability of a highly competitive market. Glob Health. (2013) 9:6. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-9-6

12. Sachs-Barrable K, Conway J, Gershkovich P, Ibrahim F, Wasan KM. The use of the United States FDA programs as a strategy to advance the development of drug products for neglected tropical diseases. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. (2014) 40:1429–34. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2014.884132

13. Speizer IS, Corroon M, Calhoun L, Lance P, Montana L, Nanda P, et al. Demand generation activities and modern contraceptive use in urban areas of four countries: a longitudinal evaluation. Glob Health Sci Pr. (2014) 2:410–26. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00109

14. Kaddar M, Milstien J, Schmitt S. Impact of BRICS' investment in vaccine development on the global vaccine market. Bull World Health Organ. (2014) 92:436–46. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.133298

15. Kesselheim AS, Maggs LR, Sarpatwari A. Experience with the priority review voucher program for drug development. JAMA. (2015) 314:1687–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11845

16. McCarthy K, Ramarao S, Taboada H. New dialogue for the way forward in maternal health: addressing market inefficiencies. Matern Child Health J. (2015) 19:1173–8. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1636-3

17. Usherenko I, Roy UB, Mazlish S, Liu S, Benkoscki L, Coutts D, et al. Pediatric tuberculosis drug market: an insider perspective on challenges and solutions. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. (2015) 19:S23–31. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0479

18. Aguado MT, Jodar L, Granoff D, Rabinovich R, Ceccarini C, Perkin GW. From epidemic meningitis vaccines for Africa to the meningitis vaccine project. Clin Infect Dis. (2015) 61:S391–5. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ593

19. Cinnamond M, Woods T. The Joint Interagency Task Force and the global steering committee for the quality assurance of health products: two new and proactive approaches promoting access to safe and effective medicines. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2015) 92:133–6. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0208

20. Meghani A, Basu S, A. review of innovative international financing mechanisms to address noncommunicable diseases. Health Aff. (2015) 34:1546–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0352

21. Berdud M, Towse A, Kettler H. Fostering incentives for research, development, and delivery of interventions for neglected tropical diseases: lessons from malaria. Oxf Rev Econ Policy. (2016) 32:64–87. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grv039

22. Inzaule SC, Ondoa P, Peter T, Mugyenyi PN, Stevens WS, Wit TFR de, et al. Affordable HIV drug-resistance testing for monitoring of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. (2016) 16:e267–75. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30118-9

23. Azimi T, Franzel L, Probst N. Seizing market shaping opportunities for vaccine cold chain equipment. Vaccine. (2017) 35:2260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.073

24. Ridley DB. Priorities for the Priority Review Voucher. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2017) 96:14–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0600

25. Berman J, Radhakrishna T. The tropical disease priority review voucher: a game-changer for tropical disease products. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2017) 96:11–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0099

26. Jain N, Hwang T, Franklin JM, Kesselheim AS. Association of the priority review voucher with neglected tropical disease drug and vaccine development. JAMA. (2017) 318:388–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7467

27. Incardona S, Serra-Casas E, Champouillon N, Nsanzabana C, Cunningham J, González IJ. Global survey of malaria rapid diagnostic test (RDT) sales, procurement and lot verification practices: assessing the use of the WHO-FIND Malaria RDT Evaluation Programme (2011-2014). Malar J. (2017) 16:196. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1850-8

28. Sunyoto T, Potet J, Boelaert M. Why miltefosine-a life-saving drug for leishmaniasis-is unavailable to people who need it the most. BMJ Glob Health. (2018) 3:e000709. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000709

29. Kerr KW, Henry TC, Miller KL. Is the priority review voucher program stimulating new drug development for tropical diseases? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2018) 12:e0006695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006695

30. Preston S, Gasser RB. Working towards new drugs against parasitic worms in a public-development partnership. Trends Parasitol. (2018) 34:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.07.005

31. Chandra D, Kumar D, A. fuzzy MICMAC analysis for improving supply chain performance of basic vaccines in developing countries. Expert Rev Vaccines. (2018) 17:263–81. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1403322

32. Cernuschi T, Malvolti S, Nickels E, Friede M. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine: A global assessment of demand and supply balance. Vaccine. (2018) 36:498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.010

33. Wang O. Buying and selling prioritized regulatory review: the market for priority review vouchers as quasi-intellectual property. Food Drug Law J. (2018) 73:383–404. Available online at: https://www.fdli.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/FDLI-Journal-73-3-Wang.pdf

34. Olliaro PL, Kuesel AC, Halleux CM, Sullivan M, Reeder JC. Creative use of the priority review voucher by public and not-for-profit actors delivers the first new FDA-approved treatment for river blindness in 20 years. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2018) 12:e0006837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006837

35. Gupta SB, Coller BA, Feinberg M. Unprecedented pace and partnerships: the story of and lessons learned from one Ebola vaccine program. Expert Rev Vaccines. (2018) 17:913–23. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1527692

36. LaForce FM, Djingarey M, Viviani S, Preziosi MP. Lessons from the meningitis vaccine project. Viral Immunol. (2018) 31:109–13. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0120

37. Pagliusi S, DCVMN AGM Organizing Committee, Dennehy M, Hun K. Vaccines, inspiring innovation in health. Vaccine. (2018) 36:7430–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.035

38. Walwyn DR, Nkolele AT. An evaluation of South Africa's public-private partnership for the localisation of vaccine research, manufacture and distribution. Health Res Policy Syst. (2018) 16:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0303-3

39. 't Hoen EFM, Kujinga T, Boulet P. Patent challenges in the procurement and supply of generic new essential medicines and lessons from HIV in the southern African Development Community (SADC) region. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2018) 11:31. doi: 10.1186/s40545-018-0157-7

40. Pandey E, Paul SB. Affordability versus innovation: Is compulsory licensing the solution? Int J Risk Saf Med. (2019) 30:233–47. doi: 10.3233/JRS-195007

41. Han FV, Weiss K. Regulatory trends in drug development in Asia Pacific. Ther Innov Regul Sci. (2019) 53:497–501. doi: 10.1177/2168479018791539

42. Bottazzi ME, Hotez PJ. “Running the Gauntlet”: Formidable challenges in advancing neglected tropical diseases vaccines from development through licensure, and a “Call to Action”. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2019) 15:2235–42. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1629254

43. Ingold H, Mwerinde O, Ross AL, Leach R, Corbett EL, Hatzold K, et al. The Self-Testing AfRica (STAR) Initiative: accelerating global access and scale-up of HIV self-testing. J Int AIDS Soc. (2019) 22:e25249. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25249

44. Dabas H, Deo S, Sabharwal M, Pal A, Salim S, Nair L, et al. Initiative for Promoting Affordable and Quality Tuberculosis Tests (IPAQT): a market-shaping intervention in India. BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e001539. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001539

45. Sunyoto T, Potet J, den Boer M, Ritmeijer K, Postigo JAR, Ravinetto R, et al. Exploring global and country-level barriers to an effective supply of leishmaniasis medicines and diagnostics in eastern Africa: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e029141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029141

46. Klatman EL, Jenkins AJ, Ahmedani MY, Ogle GD. Blood glucose meters and test strips: global market and challenges to access in low-resource settings. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2019) 7:150–60. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30074-3

47. Kaddar M, Saxenian H, Senouci K, Mohsni E, Sadr-Azodi N. Vaccine procurement in the Middle East and North Africa region: challenges and ways of improving program efficiency and fiscal space. Vaccine. (2019) 37:3520–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.029

48. Boeke CE, Adesigbin C, Agwuocha C, Anartati A, Aung HT, Aung KS, et al. Initial success from a public health approach to hepatitis C testing, treatment and cure in seven countries: the road to elimination. BMJ Glob Health. (2020) 5:e003767. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003767

49. Bastani P, Imanieh MH, Dorosti H, Abbasi R, Dashti SA, Keshavarz K. Lessons from one year experience of pooled procurement of pharmaceuticals: exploration of indicators and assessing pharmacies‘ performance. Daru. (2020) 28:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s40199-018-0228-y

50. Barofsky J, Xu J, Schneider J, Manne-Goehler J. Increasing private sector investment in neglected tropical disease (NTD) research and development: a mixed methods study. Open Forum Infect Dis. (2020) 7:S636–7. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa439.1419

51. Usher AD. COVID-19 vaccines for all? Lancet Br Ed. (2020) 395:1822–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31354-4

52. Miller M. Establishing the value and strategies for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) control: the European RSV consortium (RESCEU). J Infect Dis. (2020) 222:S561–2. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa551

53. Stevenson M, A. situation analysis of the state of supply of in vitro diagnostics in low-income countries. Glob Public Health. (2020) 15:1836–46. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1801791

54. Ridley DB, Ganapathy P, Kettler HE. US tropical disease priority review vouchers: lessons in promoting drug development and access. Health Aff Millwood. (2021) 40:1243–51. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02273

55. Choi H, Jain S, Postigo JAR, Borisch B, Dagne DA. The global procurement landscape of leishmaniasis medicines. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2021) 15:e0009181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009181

56. Vogler S, Haasis MA, Ham R. van den, Humbert T, Garner S, Sulemand F. European collaborations on medicine and vaccine procurement. Bull World Health Organ. (2021) 99:715–21. doi: 10.2471/BLT.21.285761

57. Nusrat S, Pandey AK, Samir Malhotra, Holmes A, Mendelson M, Malpani R, et al. Shortage of essential antimicrobials: a major challenge to global health security. BMJ Glob Health (2021) 6:e006961. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006961

58. Cherla A, Howard N, Mossialos E. The “Netflix plus model”: can subscription financing improve access to medicines in low- and middle-income countries? Health Econ Policy Law. (2021) 16:113–23. doi: 10.1017/S1744133120000031

59. Williams V, Edem B, Calnan M, Otwombe K, Okeahalam C. Considerations for establishing successful coronavirus disease vaccination programs in Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:2009–16. doi: 10.3201/eid2708.203870

60. Malvolti S, Pecenka C, Mantel CF, Malhame M, Lambach P, A. financial and global demand analysis to inform decisions for funding and clinical development of group B Streptococcus vaccines for pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 74:S70–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab782

61. Excler JL, Privor-Dumm L, Kim JH. Supply and delivery of vaccines for global health. Curr Opin Immunol. (2021) 71:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2021.03.009

62. Bernhard S, Kaiser M, Burri C, Mäser P. Fexinidazole for human African trypanosomiasis, the fruit of a successful public-private partnership. Diseases. (2022) 10:97. doi: 10.3390/diseases10040090

63. Abou-Nader A, Heffelfinger JD, Amarasinghe A, Nelson EAS. Assessing perceptions of establishing a vaccine pooled procurement mechanism for the Western Pacific Region. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2022) 2:e0000801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000801

64. Berman D, Chandy SJ, Cansdell O, Moodley K, Veeraraghavan B, Essack SY. Global access to existing and future antimicrobials and diagnostics: antimicrobial subscription and pooled procurement. Lancet Glob Health. (2022) 10:e293–7. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00463-0

65. Hayman B, Suri RK, Downham M. Sustainable vaccine manufacturing in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. (2022) 40:7288–304. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.10.044

66. Sahu S, Shyama N, Chokshi M, Mokashi T, Dash S, Sharma T, et al. Effectiveness of supply chain planning in ensuring availability of CD/NCD drugs in non-metropolitan and rural public health system. J Health Manag. (2022) 24:132–45. doi: 10.1177/09720634221078064

67. Pantelias A, King JD, Lammie P, Weil GJ. Development and introduction of the filariasis test strip: a new diagnostic test for the global program to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2022) 106:56–60. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0990

68. Rademacher KH, Sripipatana T, Danna K, Sitrin D, Brunie A, Williams KM, et al. What have we learned? Implementation of a shared learning agenda and access strategy for the hormonal intrauterine device. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2022) 10:e2100789. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00789

69. FIND. Democratizing Access to Testing (2022). Available online at: https://www.finddx.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/20221210_rep_democratizing_testing_FV_EN.pdf (Accessed August 8, 2025).

70. Medicines Patent Pool World Health Organization. WHO-MPP-Forecasts-March-2016.pdf (2016). Available online at: https://medicinespatentpool.org/uploads/2017/07/WHO-MPP-Forecasts-March-2016.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

71. Juneja S, Gupta A, Moon S, Resch S. Projected savings through public health voluntary licences of HIV drugs negotiated by the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP). PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0177770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177770

72. Fornadel C. Market Access Initiatives: NgenIRS and the New Nets Project. Paddington: Build Partnersh (2019).

73. Dalberg Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition. Market Shaping for Family Planning: An Analysis of Current Activities and Future Opportunities to Improve the Effectiveness of Family Planning Markets (2014). Available online at: https://www.rhsupplies.org/uploads/tx_rhscpublications/Market_Shaping_for_Family_Planning.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

74. UNITAID. Global Malaria Diagnostic and Artemisinin Treatment Commodities Demand Forecast 2016–2019 (2016). Available online at: https://unitaid.org/assets/ACT-and-RDT-Policy-Brief-2016-2019.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

75. UNITAID. Global Malaria Diagnostic and Artemisinin Treatment Commodities Demand Forecast 2017–2020 (2017). Available online at: https://unitaid.org/assets/Unitaid-Policy-Brief-ACT-Forecasting_Report-5_May-2017.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

76. UNITAID. Global Malaria Diagnostic and Artemisinin Treatment Commodities Demand Forecast 2017–2021 (2018). Available online at: https://unitaid.org/assets/Global-malaria-diagnostic-and-artemisinin-treatment-commodities-demand-forecast-2017-%E2%80%93-2021-Policy-brief-May-2018.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

77. UNITAID. Global Malaria Diagnostic and Artemisinin Treatment Commodities Demand Forecast 2015–2018 (2016). Available online at: https://unitaid.org/assets/Global_malaria_diagnostic_and_artemisinin_treatment_commodities_demand_forecast_policy_brief-1.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

78. UNITAID. Policy Brief: ACT Demand Forecast, 2012–2013. 2012. Available online at: http://www.unitaid.org/assets/PolicyBriefACTForecasting_FINAL_7-May-2012final.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

79. Baker E. Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance: Strategic Updates (2023). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/supply/media/19616/file/UNICEF_-_VIC2023_-_session_03_-_Gavi_update_-2023.pdf (Accessed August 8, 2025).

80. The Global Fund. Technical Evaluation Reference Group: Market Shaping Strategy Mid-Term Review Position Paper (2019). Available online at: https://archive.theglobalfund.org/media/9235/archive_terg-market-shaping-strategy-mid-term_review_en.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

81. Clinton Health Access Initiative. Case Study: Expanding Global Access to Contraceptive Implants (2015). Available online at: https://clintonhealthaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Case-Study_LARC.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

82. Clinton Health Access Initiative. CHAI Annual Report 2021 (2021). Available online at: https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CHAI-Annual-Report-2021.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

83. PATH. How Portfolio-Based Product Development can Accelerate Progress in Global Health (2021). Available online at: https://media.path.org/documents/G6PD_PDP_report_Dec2021.pdf?_gl=1*91u6zr*_gcl_au*NzI5MjYxNDQwLjE2ODM1Njc1MjM.*_ga*NjY3MzY5NDUuMTY3Mzk3NjI4OQ..*_ga_YBSE7ZKDQM*MTY4ODAxNjQ5My4xMi4xLjE2ODgwMTY0OTguNTUuMC4w (Accessed March 12, 2025).

84. PATH. G6PD Diagnostics: Improving Health Outcomes and Breaking the Cycle of Malaria Transmission (2022). Available online at: https://www.path.org/case-studies/malaria-diagnostics-g6pd-deficiency/ (Accessed March 12, 2025).

85. Dalberg, G. Gavi PCV AMC Pilot: 2nd Outcomes and Impact Evaluation (2021). Available online at: https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/evaluations/Gavi-PCV-AMC-pilot-2nd-Outcomes-and-impact-evaluation-Final-report.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

86. Jacobstein R. Liftoff: the blossoming of contraceptive implant use in Africa. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2018) 6:17–39. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00396

87. IFPMA. Collaborating to End Neglected Tropical Diseases: Catalyzing Innovation and Partnerships (2023) Available online at: https://www.ifpma.org/publications/collaborating-to-end-neglected-tropical-diseases-catalyzing-innovation-and-partnerships/ (Accessed August 8, 2025).

88. Kourouklis D, Berdud M, Jofre-Bonet M, Towse A. Alternative funding models for medical innovation: the role of product development partnerships in product innovation for infectious diseases. Appl Econ Lett. (2023) 30:2195–9. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2022.2095335

89. Parmaksiz K, Van De Bovenkamp H, Bal R. Does structural form matter? A comparative analysis of pooled procurement mechanisms for health commodities. Glob Health. (2023) 19:90. doi: 10.1186/s12992-023-00974-1

90. Nunes C, McKee M, Howard N. The role of global health partnerships in vaccine equity: a scoping review. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2024) 4:e0002834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002834

91. Nabhan A, Kabra R, Ashraf A, Elghamry F, Kiarie J. Family Planning Research Collaborators, et al. Implementation strategies, facilitators, and barriers to scaling up and sustaining demand generation in family planning, a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Womens Health. (2023) 23:574. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02735-z

92. Akhlaghi L, Prosser W, Rakotomanga A, Makena J, Azubike T, Bello Y, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine collaborative supply planning: is this the next frontier for routine immunization supply chains? Glob Health Sci Pract. (2024) 12:e2300150. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-23-00150

93. Parmaksiz K, Bal R, Van De Bovenkamp H, Kok MO. From promise to practice: a guide to developing pooled procurement mechanisms for medicines and vaccines. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2023) 16:73. doi: 10.1186/s40545-023-00574-9

94. Mease C, Miller KL, Fermaglich LJ, Best J, Liu G, Torjusen E. Analysis of the first ten years of FDA's rare pediatric disease priority review voucher program: designations, diseases, and drug development. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2024) 19:86. doi: 10.1186/s13023-024-03097-x

95. Medicines Patent Pool. Transformative Partnership Between the Medicines Patent Pool and ViiV Healthcare Enables 24 Million People in Low- and Middle-Income Countries to Access Innovative HIV Treatment. Available online at: https://medicinespatentpool.org/news-publications-post/transformative-partnership-between-the-medicines-patent-pool-and-viiv-healthcare (Accessed March 12, 2025).

96. Innovative Vector Control Consortium. IVCC Annual Report 2022-2023 (2023). Available online at: https://www.ivcc.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/4523_AnnualReport_22-23_Rollout_A_Access.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

97. ACT-A Tracking & Monitoring Task Force. Update on the Rollout of COVID-19 Tools (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/update-on-the-rollout-of-covid-19-tools–a-report-from-the-act-a-tracking—monitoring-task-force—15-february-2023 (Accessed March 12, 2025).

98. Nepomnyashchiy L. Discerning Demand: A Guide to Scale-Driven Product Development and Introduction (2023). Available from: https://beamexchange.org/media/filer_public/9d/2a/9d2a7601-cf16-4aed-a635-0e02f203c4b9/2303_discerning-demand_a-guide-to-scale-driven-product-development-and-introduction.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

99. Sequeira FP, Pereira J, France J, Hehman L, Gobin S, Bettine Y. Evaluation of Unitaid's Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Optimisation Portfolio. Available online at: https://unitaid.org/uploads/Antiretroviral-Therapy-ART-Optimization-End-of-Grant-Evaluation-Executive-Summary.pdf (Accessed March 12, 2025).

Keywords: market shaping, market dynamics, pooled procurement, advance market commitment, product development partnership, demand forecasting, demand generation, systematic review

Citation: Mao W, Olson K, Urli Hodges E and Udayakumar K (2025) Progress, impacts and lessons from market shaping in the past decade: a systematic review. Front. Public Health 13:1614471. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1614471

Received: 18 April 2025; Accepted: 07 July 2025;

Published: 21 August 2025.

Edited by:

Jing Yuan, Fudan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Rui Cruz, European University of Lisbon, PortugalLe Khanh Ngan Nguyen, University of Strathclyde, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Mao, Olson, Urli Hodges and Udayakumar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenhui Mao, V2VuaHVpLm1hb0BkdWtlLmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Wenhui Mao

Wenhui Mao Katharine Olson

Katharine Olson Elina Urli Hodges

Elina Urli Hodges Krishna Udayakumar

Krishna Udayakumar