- 1Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Toronto East Health Network – Michael Garron Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3The Wilson Centre, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 4Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation (IHPME), Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 5Unity Health – St. Michaels Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada

Background: Climate change is the greatest threat to human health of this century, yet limited formal curriculum exists within postgraduate family medicine (FM) programs across Canada. As outlined by The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) Guides for Improvement of Family Medicine Training (GIFT) report, learners have called for planetary health (including climate change) education and recommended a curriculum framework. This study aimed to understand University of Toronto Department of Family Medicine faculty attitudes around implementing a planetary health curriculum within the FM residency program.

Methods: This study used a qualitative descriptive design. Thirty faculty members from various teaching, curriculum, and leadership positions were invited to participate in virtual semi-structured video interviews. Data was collected and analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results: Thirteen interviews were conducted between May–September 2022. Participants perceived planetary health was relevant to FM, but most were unfamiliar with the term. Four overarching themes were developed from the data: (1) curriculum implementation, (2) curriculum development, (3) barriers, and (4) attitudes. Barriers to integrating PH learning objectives include a lack of faculty knowledge and skills, burnout, and an already saturated FM curriculum.

Conclusion: To address the climate crisis, there is need for a planetary health curriculum, yet faculty have a limited understanding of this topic. This knowledge gap is one of multiple barriers to curriculum implementation this study identified. This study provides insight and suggestions for tools that may aid planetary health curriculum development and implementation.

Introduction

The global community is reported to be facing a triple planetary crisis, encompassing the inter-related challenges of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss, all of which pose a significant threat to public health (1). Planetary health is defined by the Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission as ‘the health of human civilization and the state of the natural systems on which it depends’ (2). It is a transdisciplinary field which not only focuses on human health impacts, but also calls for urgent action to combat the extensive degradation of our planet for human advancement (2). Although similar to One health and Eco Health, planetary health emphasizes the interconnected relationship between climate change, biodiversity loss, environmental degradation, and its profound impact on human health and well-being (3). Furthermore, planetary health calls for a comprehensive systemic response, integrating societal, political, and economic strategies (i.e., the involvement of stakeholders across disciplines and fields) to address global health challenges (3, 4). The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared climate change as the greatest health threat of this century and it is already affecting the health of Canadians (5, 6). Climate change is a threat multiplier, affecting human health both directly and indirectly (e.g., physical and mental health), undermining many of the social determinants for good health, creating new public health challenges (5, 7). Although climate change impacts everyone, vulnerable and marginalized groups, such as children, older adults, Indigenous communities, racialized populations, individuals with low income, and the politically marginalized, are disproportionally affected (5, 8). Moreover, if the healthcare sector were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter on the planet (9), accounting for 4.6% of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions (10). As the foundation of medical care in Canada, family physicians (FPs) serve a crucial role in educating their patients and communities about emerging public health issues and risks in order to mitigate harm. Multiple calls to action have urged FPs to take stronger steps to address the climate crisis (11–18). Mitigating climate change is both an issue of social accountability for FPs, and an opportunity to counsel patients on the many health co-benefits of climate action (19).

As family medicine training programs have a distinct responsibility to prepare FPs to respond to and advocate for the health needs of society (20), calls to educators have been made to incorporate planetary health concepts into training programs (15–24). The 2020 Guide to Improving Family Medicine Training highlighted the need to incorporate planetary health concepts into FM residency training in Canada (22). However, prior studies have identified that a lack of faculty knowledge, bandwidth, and comfort are common barriers to curriculum development and implementation (23, 24). The purpose of this study was to explore the University of Toronto’s (UofT) Department of Family & Community Medicine (DFCM) faculty perspectives toward planetary health education within the FM residency program.

Methods

This study used a qualitative descriptive design (25) and received approval from the UofT Research Ethics Board. Using a purposive sampling method (26), 30 DFCM faculty, consisting of clinician teachers, residency program directors, curriculum leads, and senior leadership, were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews. After written consent was retrieved, interviews were recorded, transcribed, and de-identified. Three research team members (EAR, RA, AM) performed independent thematic analysis (27–32). Two team members (KL and SG) served as triangulators to reduce intrinsic biases, prejudice, and perceptions (27–32). Using NVivo 11 and Microsoft Excel, themes and codes were logged, reviewed, and refined. Thematic saturation was believed to have been achieved based on repeated data patterns in themes and subthemes (33).

Results

From May–September 2022, 13 DFCM faculty participated in semi-structured video interviews lasting approximately 45 to 60 min. All participants expressed the importance of planetary health in FM. Most indicated a lack of knowledge and skills to deliver a planetary health curriculum and noted the need for improved understanding of planetary health and teaching methods among faculty.

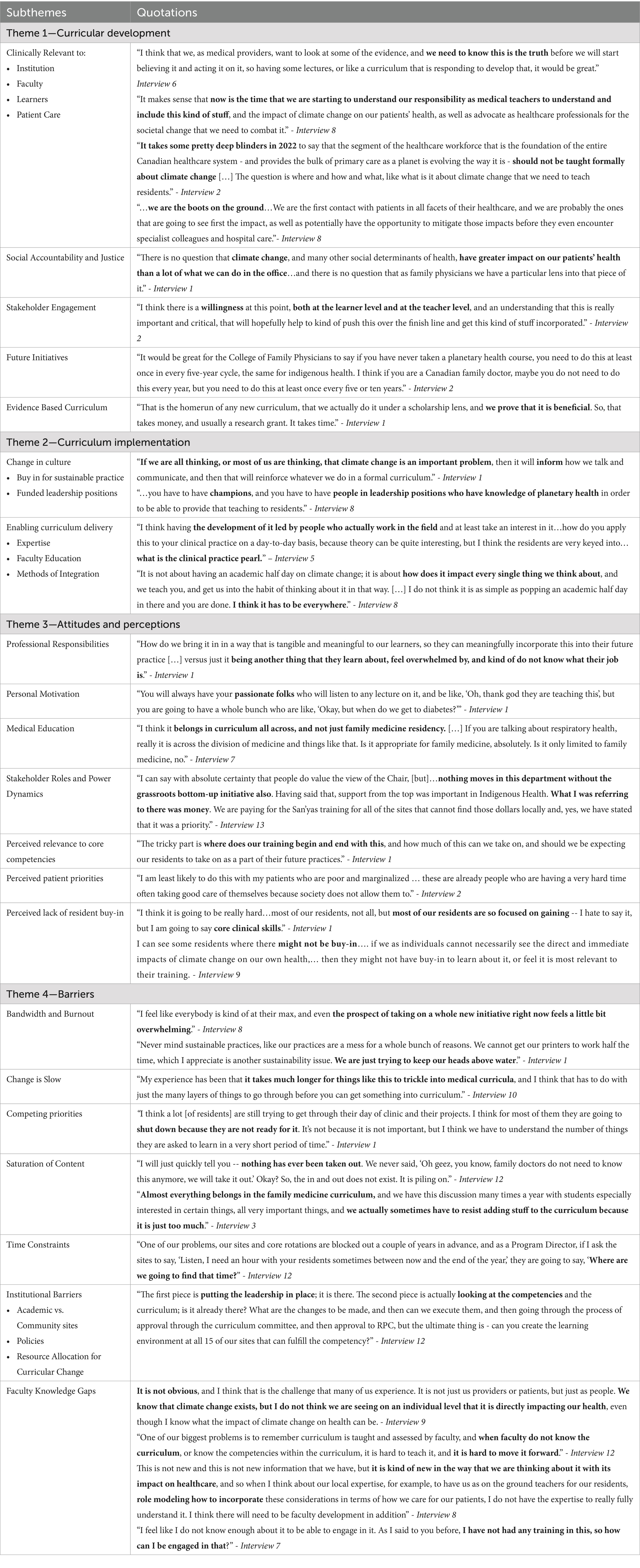

Four overarching themes and several subthemes developed (see Table 1).

1. Curriculum Development focused on a need for evidence-based curriculum, that is relevant to all parties, which incorporates social accountability, and faculty role modeling.

2. Curriculum Implementation including expert training to both undergraduate and postgraduate faculty, and culture change with the application of a planetary health lens to all aspects of clinical practice.

3. Attitudes and Perceptions were highlighted for resident and faculty buy-in, coupled with the need for support from local and general leadership.

4. Barriers included pervasive faculty burnout along with an already saturated curriculum, time constraints, and lack of resources including knowledge.

Discussion

Despite multiple calls to integrate planetary health into FM education curricula, minimal planetary health content has been implemented in the UofT FM program. With new planetary health objectives being integrated into CanMEDS 2025 (21), and evidence that medical learners are interested in planetary health (22–24, 34–38), there is a need for curriculum development in post graduate medical education (21, 24).

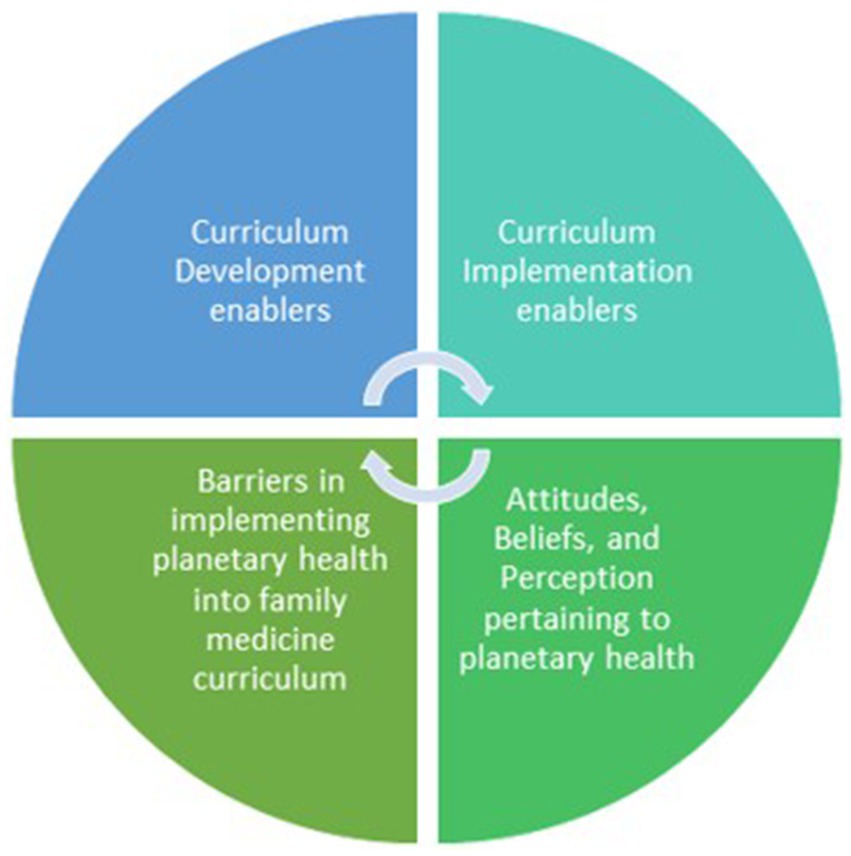

Participants cited many barriers to implementing a planetary health curriculum, including personal (e.g., expertise, bandwidth, time), and institutional barriers (e.g., saturated curriculum, lack of expertise, lack of time in residency program), in keeping with prior studies (23). These findings align with Luo et al., who reported two significant barriers to integrating universal planetary health medical curricula in Canada: (1) limited curricular space for new content and (2) a lack of faculty expertise for teaching and role-modeling (35). Faculty attitudes and beliefs may also be indirect barriers to implementing planetary health content in FM residency programs. Understanding such challenges will help facilitate and enable planetary health curriculum development and implementation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Faculty’s attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions may be indirect barriers in implementing planetary health into family medicine, which informs of potential enablers that would facilitate planetary health curriculum development and implementation at the DFCM.

As most faculty expressed a lack of knowledge in planetary health concepts, using adaptive and transformational learning approaches would likely be best suited for the clinical challenges of planetary health. Adaptive experts are skilled at innovative problem solving in response to novel practice challenges and are prepared to remain curious and engaged in learning to meet the changing needs of their future practice (39). Transformative Learning is an educational theory that drives “dramatic, fundamental change in the way we see ourselves and the world in which we live” (40). The outcome of transformative learning is the development of a more open and inclusive worldview (41) that may lead to more lasting individual or systems change (42).

Practice-based learning and improvement has been proposed as a possible Transformative Learning method in health professional education (43). Through critical reflection on a disorienting dilemma, learners may improve their own clinical practice, recognize injustices in the health care system, and learn to intervene at the micro, meso, and macro levels (43).

To address faculty knowledge development while balancing burnout concerns, educational tools must be directed at faculty (44). Faculty development efforts must be offered in acceptable, interesting, and approachable ways (44). Moreover, as expressed by participants, addressing faculty development needs—especially in areas of support, expertise development, and confidence—is crucial for overcoming barriers to planetary health FM curriculum implementations. As such, the use of planetary health education leadership such as co-ordinators (4) or directors (45), may effectively mitigate these challenges. Additionally, blended learning, a combination of face-to-face and e-learning, has been found to be superior to traditional learning on knowledge outcomes (46).

We propose the following as methods for faculty development:

1. Brief 10-min presentations on select, clinically relevant planetary health topics to FM residency training sites for review at team/teachers’ meetings.

2. An asynchronous e-module on planetary health developed by local experts that is easily accessible by both faculty and residents Refer to Feldman et al. https://rise.articulate.com/share/DcYCoaIt75885kj403ISZbneuu3sFrbd#/ as an example (47).

3. Incorporation of planetary health teaching into existing curriculum, such as Quality Improvement (QI) programs, to provide both transformative and adaptive learning opportunities.

4. An asynchronous case-based learning module, which both residents and faculty could complete together. There is precedent for learner-led curriculum development and learner/faculty co-education in planetary health (48), and these ideas are likely applicable to residency education. This would be clinically meaningful and relevant and would enable faculty and residents to learn about planetary health together, with minimal local expertise. Using the module as a facilitator of interaction between learners and teachers, in a setting conducive to planetary health reflection, would provide benefits beyond educational needs.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating perceptions of FM faculty toward a planetary heath curriculum in Canada. As this study was conducted only at a single university, and given the challenges in implementing planetary health curricula, generalizability may be limited. However, findings from this study may be transferable and relevant to other medical disciplines and health professional training contexts.

Conclusion

A planetary health curriculum in FM postgraduate training is critical to equipping future FPs with the necessary knowledge and skills to face the health impacts of climate change and other ecological crises. FM faculty development, provided in a way that is sensitive to burnout and time constraints, is required to teach planetary health objectives. Using adaptive and transformational learning techniques, faculty development can be done in a multi-modal way to improve efficiency and uptake. Incorporating a planetary health lens into existing curriculum would reduce time burden into a busy curriculum.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to confidentiality and is to be destroyed after 5 years. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to a2l0c2hhbi5sZWVAdXRvcm9udG8uY2E=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Toronto Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KL: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Resources, Project administration, Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision. E-AR: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Software, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Visualization. SG: Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Funding acquisition, Resources, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Project administration. RA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis. AM: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Art of Possible Education Scholarship Grant, from the Office of Education Scholarship, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants in the study, along with Dr. Risa Bordman and Dr. Joyce Nyhof-Young for their ongoing support of this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Ihsan, FR, Bloomfield, JG, and Monrouxe, LV. Triple planetary crisis: why healthcare professionals should care. Front Med. (2024) 11:1465662. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1465662

2. Lancet Planet Health. Welcome to the lancet planetary health. Lancet Planet Health. (2017) 1:e1. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30013-X

3. Halonen, JI, Erhola, M, Furman, E, Haahtela, T, Jousilahti, P, Barouki, R, et al. A call for urgent action to safeguard our planet and our health in line with the Helsinki declaration. Environ Res. (2021) 193:110600. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110600

4. Grieco, F, Parisi, S, Simmenroth, A, Eichinger, M, Zirkel, J, König, S, et al. Planetary health education in undergraduate medical education in Germany: results from structured interviews and an online survey within the national PlanetMedEd project. Front Med. (2025) 11:1507515. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1507515

5. World Health Organization. Climate change and health. (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (Accessed Jun 12, 2025).

6. Canadian Medical Association. (2019). The 2019 Lancet countdown on health and climate change: policy brief for Canada. Available online at: https://policybase.cma.ca/viewer?file=%2Fmedia%2FPolicyPDF%2FPD20-06.pdf#page=1 (Accessed Jun 12, 2025).

7. Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization. Climate change and health. Climate Change and Health (2020). Available online at: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52930 (Accessed Jun 12, 2025).

8. Costello, A, Abbas, M, Allen, A, Ball, S, Bell, S, Bellamy, R, et al. Managing the health effects of climate change: lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet. (2009) 373:1693–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1

9. Karliner, J, Slotterback, S, Boyd, R, Ashby, B, and Steele, KHealth Care Without Harm. Health careʼs climate footprint: how the health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action; (2019). Available online at: https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documentsfiles/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_092319.pdf (Accessed Jun 12, 2025).

10. Eckelman, MJ, Sherman, JD, and MacNeill, AJ. Life cycle environmental emissions and health damages from the Canadian healthcare system: an economic-environmental-epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med. (2018) 15:e1002623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002623

11. College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC). (2019). Call to action on climate change and health; Available online at: https://www.cfpc.ca/CFPC/media/PDF/Call-to-Action-Full-logos-updated-EN-June-25-2019.pdf (Accessed Jun 12, 2025).

12. Temerty Faculty of Medicine University of Toronto. Climate change is a health education crisis. (2022). Available online at: https://temertymedicine.utoronto.ca/news/climate-change-health-education-crisis (Accessed Jun 12, 2025).

13. Fraser, S. Climate change is a health issue. Can Fam Physician. (2021) 67:719. doi: 10.46747/cfp.6710719

14. Salas, RN, and Solomon, CG. The climate crisis - health and care delivery. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381:e13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1906035

15. Wellbery, CE. Climate change health impacts: a role for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. (2019) 100:602–3.

16. Goshua, A, Gomez, J, Erny, B, Burke, M, Luby, S, Sokolow, S, et al. Addressing climate change and its effects on human health: a call to action for medical schools. Acad Med. (2021) 96:324–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003861

17. Hackett, A, Letourneau, S, Cohen, A, and Kitching, G, Canadian Federation of Medical Students (CFMS). Health and Environment Adaptive Response Task Force. (2025). Available online at: https://www.cfms.org/what-we-do/global-health/heart.html (Accessed Jun 12, 2025).

18. Maxwell, J, and Blashki, G. Teaching about climate change in medical education: an opportunity. J Public Health Res. (2016) 5:673. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2016.673

19. Wang, H, and Horton, R. Tackling climate change: the greatest opportunity for global health. Lancet. (2015) 386:1798–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60931-X

20. Frenk, J, Chen, L, Bhutta, ZA, Cohen, J, Crisp, N, Evans, T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. (2010) 376:1923–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5

21. Green, S, Labine, N, and Luo, OD. Planetary health in CanMEDS 2025. Canadian Med Educ J. (2023) 14:46–9. doi: 10.36834/cmej.75438

22. Bouka, A, Belanger, P, Thibault, A, and Saleh, ZCollege of Family Physicians of Canada. Guide to integrating planetary health in family medicine training. (2021). Available online at: https://www.cfpc.ca/CFPC/media/Resources/Education/GIFT-Planetary-Health-one-pager-ENG.pdf (Accessed Jun 12, 2025).

23. Blanchard, OA, Greenwald, LM, and Sheffield, PE. The climate change conversation: understanding Nationwide medical education efforts. Yale J Biol Med. (2023) 96:171–84. doi: 10.59249/PYIW9718

24. Philipsborn, RP, Sheffield, P, White, A, Osta, A, Anderson, MS, and Bernstein, A. Climate change and the practice of medicine: essentials for resident education. Acad Med. (2021) 96:355–67. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003719

25. Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. (2010) 33:77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362

26. Palinkas, LA, Horwitz, SM, Green, CA, Wisdom, JP, Duan, N, and Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. (2015) 42:533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

27. Braun, V, and Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

28. Braun, V, and Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns Psychother Res. (2021) 21:37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360

29. Kiger, ME, and Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide no. 131. Med Teach. (2020) 42:846–54. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

30. Denzin, NK, and Lincoln, YS. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE (2011).

31. Percy, WH, Kostere, K, and Kostere, S. Generic qualitative research in psychology. Qual Rep. (2015) 20:76–85. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2097

32. Nowell, LS, Norris, JM, White, DE, and Moules, NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. (2017) 16:1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

33. Guest, G, Namey, E, and Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0232076–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

34. Mercer, C. Medical students call for more education on climate change. CMAJ. (2019) 191:E291–2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5717

35. Luo, OD, Wang, H, Velauthapillai, K, and Walker, C. An approach to implementing planetary health teaching in medical curricula. Can Med Educ J. (2022) 13:98–100. doi: 10.36834/cmej.75514

36. Omrani, OE, Dafallah, A, Paniello Castillo, B, Amaro, BQRC, Taneja, S, Amzil, M, et al. Envisioning planetary health in every medical curriculum: an international medical student organization's perspective. Med Teach. (2020) 42:1107–11. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1796949

37. Létourneau, S, Roshan, A, Kitching, GT, Robson, J, Walker, C, Xu, C, et al. Climate change and health in medical school curricula: a national survey of medical students’ experiences, attitudes and interests. J Clim Chang Health. (2023) 11:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joclim.2023.100226

38. Kotcher, J, Maibach, E, Miller, J, Campbell, E, Alqodmani, L, Maiero, M, et al. Views of health professionals on climate change and health: a multinational survey study. Lancet Planet Health. (2021) 5:e316–23. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00053-X

39. Edje, L, and Price, DW. Training future family physicians to become master adaptive learners. Fam Med. (2021) 53:559–66. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.192268

40. Mylopoulos, M, and Regehr, G. Cognitive metaphors of expertise and knowledge: prospects and limitations for medical education. Med Educ. (2007) 41:1159–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02912.x

41. Merriam, SB, and Baumgartner, LM. Learning in adulthood: A comprehensive guide. San Francisco, USA: John Wiley & Sons (2020).

42. Regehr, G, and Mylopoulos, M. Maintaining competence in the field: learning about practice, through practice, in practice. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. (2008) 28:S19–23. doi: 10.1002/chp.203

43. Wittich, CM, Reed, DA, McDonald, FS, Varkey, P, and Beckman, TJ. Perspective: transformative learning: a framework using critical reflection to link the improvement competencies in graduate medical education. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1790–3. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f54eed

44. Lee, KS, Ramdawar, EA, and Adilman, R. Exploring faculty attitudes and knowledge regarding curriculum implementation of planetary health at the Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM). Montreal, Quebec, Canada: University of Toronto (2023).

45. Moloo, H, Gaudreau-Simard, M, Kendall, C, Best, G, Seguin, N, Jasmin, BJ, et al. Revitalising medical governance for a healthier world: the urgent case for a director of planetary health in every faculty of medicine. Lancet Planetary Health. (2024) 8:e135–7. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00009-3

46. Vallée, A, Blacher, J, Cariou, A, and Sorbets, E. Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical education: systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e16504. doi: 10.2196/16504

47. Feldman, L, Vinegar, M, Yu, K, Green, S, and Lee, KS. Planetary health for family medicine residents and teachers. Articulate Rise. (2025). Available online at: https://rise.articulate.com/share/DcYCoaIt75885kj403ISZbneuu3sFrbd#/

Keywords: medical education, curriculum development, community health/public health, faculty development, planetary health, family medicine

Citation: Lee KS, Ramdawar E-A, Green S, Adilman R and Mangalji A (2025) Exploring faculty perspectives toward developing a planetary health curriculum for family medicine residents at the University of Toronto. Front. Public Health. 13:1614872. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1614872

Edited by:

Paulo Hilario Nascimento Saldiva, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Rohini Rowena Roopnarine, St. George’s University, GrenadaGustavo J. Nagy, Universidad de la República, Uruguay

Copyright © 2025 Lee, Ramdawar, Green, Adilman and Mangalji. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: KitShan Lee, a2l0c2hhbi5sZWVAdXRvcm9udG8uY2E=

†ORCID: Elisabeth-Abigail Ramdawar, orcid.org/0009-0009-0914-2527

KitShan Lee

KitShan Lee Elisabeth-Abigail Ramdawar

Elisabeth-Abigail Ramdawar Samantha Green1,5

Samantha Green1,5