- 1School of Public Health, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 2BOLD Public Health Center of Excellence on Dementia Caregiving, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 3Alzheimer’s Association, Chicago, IL, United States

- 4BOLD Public Health Center of Excellence on Dementia Risk Reduction, Alzheimer’s Association, Chicago, IL, United States

- 5Division of Geriatric Medicine and Palliative Care, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

- 6BOLD Public Health Center of Excellence on Early Detection of Dementia, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

- 7Division of Health and Behavior, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

- 8Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Community Health Workers (CHWs) are a growing part of the healthcare workforce. Trusted in their communities, CHWs can provide essential health education and connection with culturally responsive health and support resources and programs. Despite their demonstrated effectiveness in improving outcomes in other chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, HIV, and pediatric asthma, CHWs have been underutilized in dementia-related efforts. Properly equipped with education and skills, CHWs can fill important gaps throughout the dementia care continuum, strengthening public health efforts to support people with dementia and their families, especially in populations at higher risk such as African American, Latino and American Indian/Alaska Native groups. We outline key roles CHWs can play throughout the continuum of dementia care, improving brain health and reducing dementia risk at all life stages, such as improving early detection of cognitive impairment and helping caregivers navigate the daily challenges of dementia care in the community setting. Finally, we highlight key actions public health can lead to support the development of a dementia-capable workforce nationwide.

1 Introduction

In the United States (U.S.), 129 million people over the age of 18 have at least one chronic condition, and chronic diseases account for 90% of all health expenditures in the U.S (1). Environmental and socioeconomic conditions, such as the built environment, healthy food, and employment status influence health and risk of disease more than genetic factors or access to healthcare services (2). Recognizing the need to address nonmedical influences on health and consider non-traditional ways of delivering care, the U.S. healthcare and public health systems have embraced a more holistic and collaborative approach, integrating medical with community-based social care to promote community-clinical linkages. Supporting cross-sector coordination among healthcare systems, social services, and community organizations, this evolving concept of care recognizes that each sector has a role in addressing social determinants of health and improving the community’s health. This holistic view of health is also at the core of the World Health Organization’s growing Age-Friendly Cities and Communities movement. Age-friendly communities are environments designed to support the autonomy, inclusion and contribution of older adults (3). A related U.S. initiative, Dementia Friendly America, focuses specifically on promoting inclusion and quality of life for people with dementia and their care partners (4). Both age-and dementia-friendly community movements emphasize the social dimensions of health and rely on a variety of community partners and care roles to facilitate coordination of health and social care across settings for older adults and their care partners (5).

Among chronic diseases, dementia presents a compelling case for integrated care. Dementia, a broad category of brain disorders that affect cognitive function, causes difficulties with memory, thinking, and other skills that interfere with daily life and the person’s ability to interact with others (6). Dementia is a significant cause of disability and dependence. These effects extend beyond the individual to families that provide care and the communities where individuals and families live. The needs of people living with dementia call for a flexible social support network able to assist not only immediate family but also friends, community members, and organized service providers. Research has established that lower educational attainment and many forms of social disadvantage are associated with a higher likelihood of dementia and are concentrated in ethnically-and racially-minoritized groups, including African American, Hispanic, American Indian, and some Asian American subgroups. Gaps in the dementia care continuum disproportionately affect these groups and are patterned by social, educational, and economic disadvantage (7). Dementia also carries substantial societal financial costs, especially in publicly funded health and social care. In 2024 alone, the cost of all healthcare and long-term care for people with dementia was estimated to be $360 billion (6). These monetary costs are just one aspect of the total cost of dementia; unpaid family caregivers in the community provide over 80% of all dementia care (8). Finally, dementia is a complex, long-term chronic condition that affects the co-morbidity and management of other chronic conditions. As the person loses the capacity to make independent decisions and direct their own care, managing co-occurring chronic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, depression, and frailty can become more challenging (9) and requires changes in the roles and interactions of clinicians and family members. As many as 90% of people with dementia also have at least one other chronic disease (7), and the majority have several. Caring for someone with dementia ultimately entails managing functional, behavioral, medical, financial, social, and legal aspects of the person’s life, and requires extensive coordination between clinicians, others on the healthcare team, community services, and family.

It is now widely understood that our healthcare, public health, and social systems are not well prepared to respond to the extent and complexities of dementia care management. The size of our professional dementia-capable healthcare and social services workforce is insufficient to meet current and future demand for dementia care (for an analysis of this topic, see The Alzheimer’s Association, 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures report). Addressing the many social and economic health needs of people with dementia falls outside of the expertise and boundaries of traditional healthcare, often leaving family caregivers to take on full responsibility for coordinating services (9). The realities of dementia care call for developing a more diverse array of healthcare workers to bridge dementia care across settings. At this intersection of healthcare delivery, community care, and public health, Community Health Workers (CHW) emerge as one part of the solution that can align and advance the goals of all sectors. The goal of this paper is to illustrate the potential roles of CHWs in dementia risk reduction, detection and care, and how nationally recognized CHW core competencies can be applied to help fill gaps in the dementia care continuum.

2 Community health workers: a key part of the public health workforce

The American Public Health Association (10) defines Community Health Workers (CHWs) as “frontline public health workers who are trusted members of and/or have an unusually close understanding of the community served. This trusting relationship enables CHWs to serve as a liaison/link/intermediary between health/social services and the community to facilitate access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery. CHWs also build individual and community capacity by increasing health knowledge and self-sufficiency through a range of activities such as outreach, community education, informal counseling, social support and advocacy.”

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics identifies 67,200 CHWs in the U.S. in 2022, and the Bureau projects this number to grow by about 14% by 2032 (11). CHWs may hold many job titles within their employing organizations, including peer navigators, lay health workers, community health advocates, community health representatives, peer educators, promotor de salud, and outreach specialists (12–14), and can perform various essential and complementary functions.

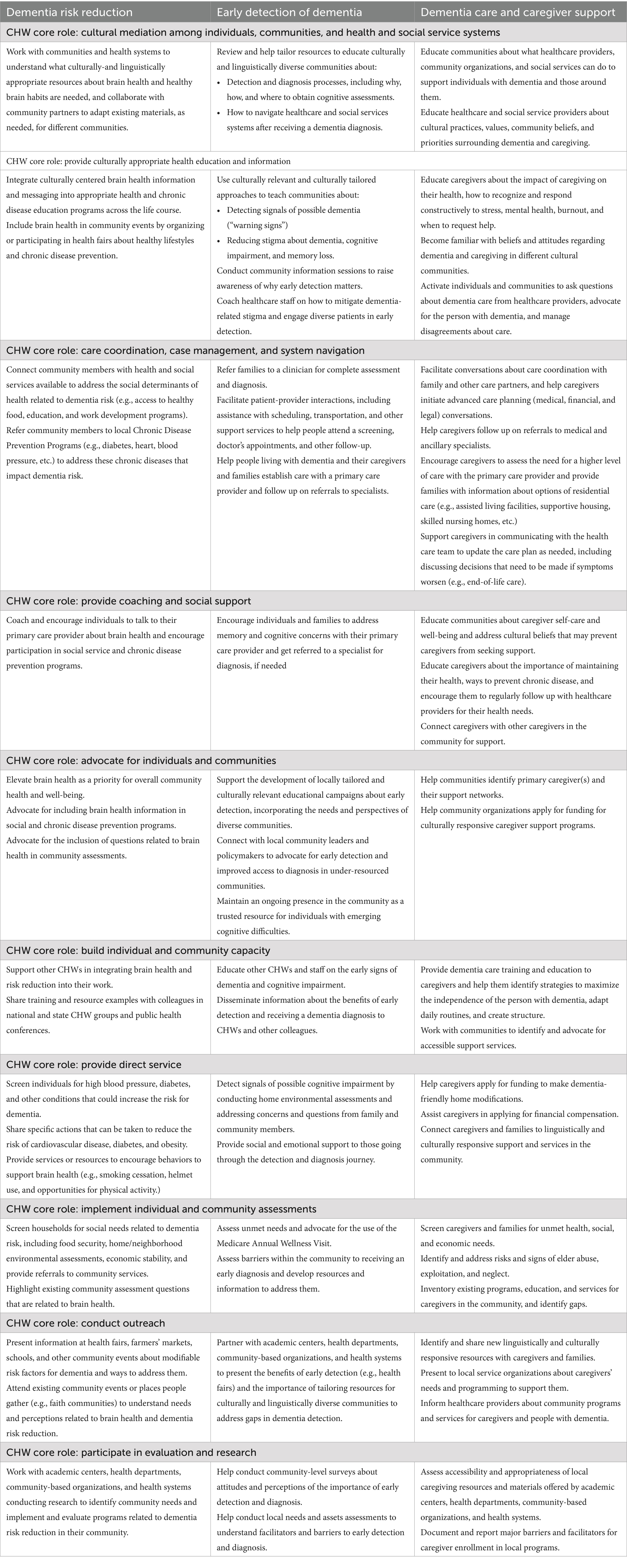

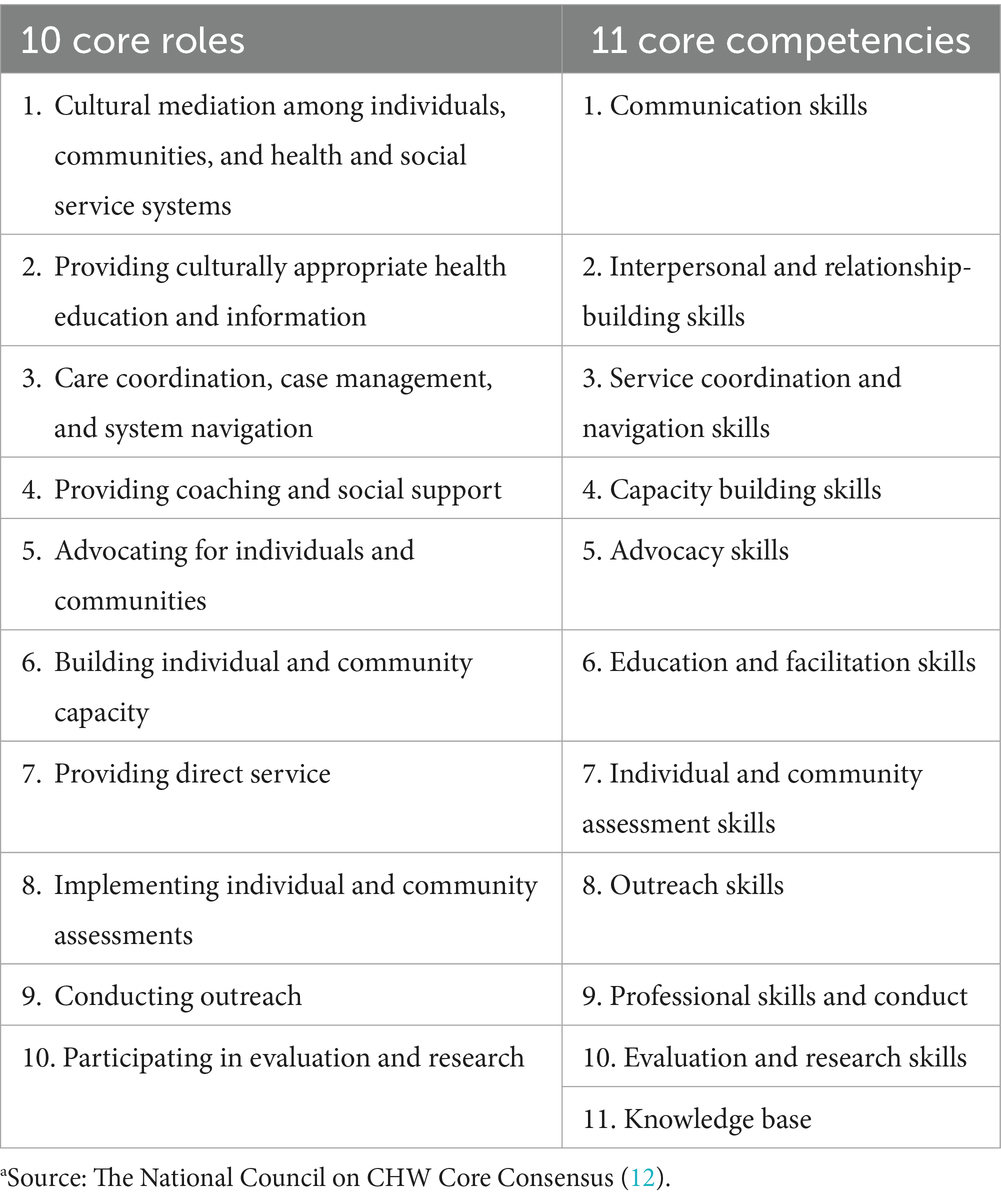

Recognizing the potential contribution of CHWs to addressing healthcare delivery shortfalls, various efforts are underway to define professional standards and competencies for the growing CHW workforce and integrate them into healthcare. Within the CHW profession, the National Council on CHW Core Consensus (C3) Standards, formerly the C3 Project, is a national initiative that aims to provide cohesion to the field and increase visibility and understanding of the full potential of CHWs. The National C3 Council has developed a single set of core roles and competencies for CHWs, regardless of their work setting (Table 1) (15). Together, the core roles and competencies define the scope of work, skills, and qualities for CHWs, and serve as a foundational framework to develop training and improve policies to strengthen and expand the CHW workforce.

Table 1. Core roles and competencies of community health workersa.

At the state level, there has been increased action to standardize and formalize the CHW workforce by implementing certification programs for CHWs (16) and identifying stable funding sources to sustain the CHW workforce (17). At the federal level, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services launched the Community Health Worker Training Program in 2022, which aimed to increase the number of CHWs and support training and apprenticeship programs nationwide (18).

Many chronic disease interventions have incorporated CHWs because of their potential to improve chronic disease outcomes in low-income, underserved, and minoritized communities (19). CHWs have been essential in rural areas providing health services, education, and support where other services and resources may be limited (20). CHWs have also been involved in dementia programming, although to a lesser extent than in other chronic conditions. Promising programs exist in California (21), Minnesota (22) and Missouri (23), among others. However, they remain localized success stories, and their learnings have not broadly informed recommendations for dementia-specific training and development initiatives for CHWs. Additionally, without a coordinated effort to inventory CHW-led programs, the full scope and extent of CHWs’ work in dementia-related programming is unknown, and research on their contributions to dementia services and care is still limited (24).

Given CHWs’ success in managing and improving outcomes for other chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease (25), diabetes (26), and HIV (27), CHWs, if properly prepared, can effectively address dementia. CHWs can increase awareness of dementia risk factors, facilitate care transitions from community to primary to specialty care, and help caregivers and people with dementia find and access community resources (24). Thanks to their work in the healthcare, community, and social service settings and their deep knowledge of and trusted role within the community, CHWs are ideally positioned to support people with dementia and their caregivers throughout the continuum of dementia care.

3 National momentum to transform dementia care: opportunities to engage CHWs

Two important national-level initiatives that aim to transform dementia care are underway: a healthcare-centered initiative to link medical and social care, and the creation of a national public health infrastructure dedicated to brain health and cognitive decline and dementia. CHWs can play vital roles in both.

In the healthcare sector, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation is testing a new payment mechanism for comprehensive dementia care, initiated in summer 2024. The Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE) Model (28) integrates social care into the delivery of healthcare and provides support for both people with dementia (care planning and coordination) and their caregivers (connections to evidence-based education, training, and community-based services). GUIDE’s innovations are two-pronged: it creates a dementia-specific alternative payment model and defines a new role—that of care navigator (29). Care navigators are specifically trained for the role of coordinating care and support services for people with dementia and their caregivers across health and social care settings, a role that is well suited for CHWs.

In the U. S., the 2018 Building Our Largest Dementia Infrastructure for Alzheimer’s Act (BOLD Act) (Public Law 155–406) consolidated more than a decade of dementia advocacy efforts after Congress first appropriated public health funding for Alzheimer’s Disease in 2005 (30). The BOLD Act empowers the Centers for Disease Control to build a national public health infrastructure to promote dementia risk reduction, improve early detection and diagnosis of dementia, and support dementia caregivers. BOLD supports three national Public Health Centers of Excellence, each Center addressing one of these three dimensions of public health prevention; currently, 43 state, local, territorial, and tribal health organizations also receive BOLD funding to support their own public health efforts. Implementation of the BOLD Act is driven nationally by the Healthy Brain Initiative Road Map for State and Local Public Health (Road Map) (31). The Road Map provides direction and suggests actions for state and local health departments to improve brain health in their communities. An important domain of public health action the Road Map prioritizes is the development of a diverse and skilled workforce, recognizing the urgent need to diversify and grow the current healthcare and social services workforce to support the growing population affected by dementia.

CHWs can play fundamental roles in assuring the success of both BOLD and the GUIDE Model. When positioned at the intersection of public health, clinical care, and community services, CHWs and other direct care workers can connect all three sectors in service to individuals and care partners and augment each sector’s workforce capacity. Properly trained in the subject matter of dementia, dementia care, and social needs, they could extend to dementia their long-valued roles in other areas of public and community health practice.

4 Roles of CHW across the dementia care continuum

CHWs’ work is applicable throughout the continuum of dementia care and across settings where they may work to help care for people with dementia. Table 2 provides examples of dementia-related activities that CHWs can do to support people with dementia and their families throughout the disease continuum, aligned with the 10 Core Professional CHW Roles.

5 Integrating CHWs in dementia efforts: opportunities for public health leadership

5.1 Adopt a life-course approach to brain health and dementia in CHW training

CHWs work with community members in different life stages for programs spanning from maternal and early childhood health to adolescent and young adulthood, to older adulthood, and therefore have opportunities to engage multi-generational households to improve brain health and quality of life for people of all ages and at all stages of dementia. Prior to dementia diagnosis, CHWs can promote brain health and address dementia risk factors. To improve access to diagnosis and quality care, CHWs can provide education, connect community members with primary and specialty medical care, and foster collaboration between community and healthcare organizations. After a diagnosis of dementia, CHWs can play a key role in building a support network for people with dementia and family caregivers within the community. In addition, integrating dementia education into CHW training for other chronic disease efforts can further support the life-course approach to brain health. Because CHWs can work with people within their home and community settings, they can bring a uniquely grounded insight into the challenges individuals face in preventing and managing dementia-related issues and other chronic conditions. They can also provide individualized support and interventions tailored to their unique circumstances, needs, and strengths. Integrating education about brain health, dementia, and the opportunities for intervention across the life course into training and education curricula for CHWs can better prepare them to support overall health, advance equity in brain health, and improve the quality of life for people with dementia and caregivers of all ages. In the Annual Workforce Survey conducted by the National Association of CHWs in 2021, respondents rated “additional CHW training, including continuing education and specialties,” as the most valued influence on their career growth (32).

Many state and local governments are recognizing the potential for CHWs to work in new areas of health and care (17). Content about dementia and caregiving is now being integrated into many education and training programs for CHWs, including a comprehensive program developed in Oklahoma (33). Public health should inventory such promising training curricula, identify strengths and gaps of each, and recommend a set of competencies and scope of practice related to dementia for CHWs nationally. A standard dementia-specific training curriculum aligned with CHW professional roles to support the activities and roles outlined in Table 2 above would establish dementia as a chronic disease for CHW focus and solidify CHWs’ role in broader public health efforts to address dementia. Recommendations for a national dementia-specific curriculum are currently under development by a collaborative group of public health and professional organizations working with CHWs in the U.S. The curriculum will have a core set of dementia-related content and will be flexibly designed to allow for tailoring to the requirements and regulations of local CHW ecosystems (e.g., at the state and organizational levels). Modifications could include different modes of delivery (e.g., virtual, in-person, hybrid), adaptations for varying levels of professional experience of CHWs (e.g., training needs of experienced CHWs who are new to dementia work as opposed to those who are entirely new to working as a CHW), the setting in which CHWs are employed (e.g., hospital-based, CBO-based, health department-based), among others.

5.2 Support CHW certification

States and other entities are actively developing certification standards for CHWs to encourage sustained employment and garner support from policymakers. As of March 2024, 23 states have certification programs for CHWs (16). Stable funding sources for the CHW workforce are essential. Medicaid (34) and, more recently, Medicare (35) will reimburse CHW services if recognized by the state where they work. However, CHW certification is state-dependent and not available everywhere. Public health could provide policy leadership and guidance to states around CHW certification so that all certified CHWs are reimbursed in the states where they live and work. Tiered systems for CHW certification that recognize focused education and experience, like the one in South Carolina, can serve as a model for other states looking to create advancement pathways and reimbursement options for CHWs (36).

Public health can further facilitate this process by clarifying the terminology used to describe the CHW role and how it differs from and complements other comprehensive care coordination and medical case management roles (e.g., Care Coordinator, Care Navigator, Social Worker, Dementia Care Specialist, etc.). Finally, public health can encourage dialogue and consensus-building among professional CHW associations and interest groups across states towards a national set of competencies and certification standards adaptable to different state regulations and legislative ecosystems.

In addition to advancements in certification, related structural changes are needed to support and sustain a dementia-capable CHW workforce. Here, public health can help develop safety protocols to protect the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of CHWs working in the field and establish transparent patient-focused standards (e.g., receiving clinical supervision, managing caseloads to account for catchment area and case complexity, navigating complex cases, etc.).

6 Conclusion

The need for dementia care is on track to outpace the capacity of the available professional dementia workforce and family caregivers in the coming decades (6). New models of dementia care are emerging from programs like GUIDE, but these programs are pilots, not available to everyone and may focus on the later stages of disease management. CHWs should become an essential part of a national infrastructure for comprehensive dementia care, by both expanding the capacity of a dementia-capable workforce across the life course and facilitating access to comprehensive dementia care for millions of people with dementia and their caregivers. As they do in other chronic diseases, CHWs can play essential roles throughout the continuum of dementia care, increasing education and awareness about risk reduction strategies, supporting early detection in the community setting, and facilitating care transitions and continued support between healthcare, community, and home settings. With their reach across sectors and within communities, CHWs can support the development of both age-friendly and dementia friendly communities in the U.S.

Supporting the development of dementia-specific training for CHWs and creating consistency among state certifications are two important ways public health can strengthen this critical segment of the public health workforce. By strengthening today’s dementia-capable CHW workforce, we can build the collective capacity to improve brain health and dementia care for all.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

EJ: Visualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MiL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AN: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MaL: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization. SR: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. JG: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. SB: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authorship of this article is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of three financial assistance awards totaling $8,931,822 with 100 percent funded by CDC/HHS. The contents are those of the presenters and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, CDC/HHS, or the U.S. Government.

Acknowledgments

Co-author Mickal Lewis is a certified Community Health Worker (CHW). All authors are members of a working group dedicated to supporting and expanding the roles of CHWs in dementia risk reduction, detection, and care.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fast facts: health and economic costs of chronic conditions. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/data-research/facts-stats/index.html (Accessed April 11, 2025).

2. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (Sdoh). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/about/priorities/why-is-addressing-sdoh-important.html (Accessed April 11, 2025).

3. World Health Organization. National programmes for age-friendly cities and communities: a guide (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240068698 (Accessed May 22, 2025).

4. Dementia Friendly America. About DFA. Available online at: https://dfamerica.org/about/ (Accessed May 22, 2025).

5. Turner, N., and Morken, L. Better together: a comparative analysis of age-friendly and dementia friendly communities. AARP International Affairs. (2016). Available online at: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/livable-communities/livable-documents/documents-2016/Better-Together-Research-Report.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2025)

6. Alzheimers Association (2024) Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Available online at: https://www.alz.org/getmedia/76e51bb6-c003-4d84-8019-e0779d8c4e8d/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf (Accessed April 11, 2025).

7. Manly, JJ, Jones, RN, Langa, KM, Ryan, LH, Levine, DA, McCammon, R, et al. Estimating the prevalence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in the US: the 2016 health and retirement study harmonized cognitive assessment protocol project. JAMA Neurol. (2022) 79:1242–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.3543

8. Friedman, EM, Shih, RA, Langa, KM, and Hurd, MD. US prevalence and predictors of informal caregiving for dementia. Health Aff. (2015) 34:1637–41. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0510

9. Reuben, D, Epstein-Lubow, G, Evertson, L, and Jennings, L. Chronic disease management: why dementia care is different. Am J Manag Care. (2022) 28:e452–4. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2022.89258

10. American Public Health Association. Support for community health workers to increase health access and to reduce health inequities. (2009). Available online at: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/09/14/19/support-for-community-health-workers-to-increase-health-access-and-to-reduce-health-inequities (Accessed April 11, 2025).

11. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Community health workers. (2024). Available online at: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/community-and-social-service/community-health-workers.htm (Accessed April 11, 2025).

12. Sabo, S, Allen, CG, Sutkowi, K, and Wennerstrom, A. Community health workers in the United States: challenges in identifying, surveying, and supporting the workforce. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107:1964–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304096

13. Olaniran, A, Smith, H, Unkels, R, Bar-Zeev, S, and Van Den Broek, N. Who is a community health worker? A systematic review of definitions. Glob Health Action. (2017) 10:1272223. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1272223

14. Kaalund, K, Phillips, E, Farrar, B, Perreira, K, Taylor, M, Wellman, M, et al. Opportunities to enhance health equity by integrating community health workers into payment and care delivery reforms. Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy. May 23, (2023). Available online at: https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/publications/opportunities-enhance-health-equity-integrating-community-health-workers-payment (Accessed April 11, 2025).

15. Rosenthal, EL, Menking, P, St John, J, Fox, D, Holderby-Fox, LR, Redondo, F, et al. The national council on CHW core consensus (C3) standards reports and website. Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso. 2014–2024. Available online at: https://www.C3Council.org/ (Accessed April 11, 2025).

16. Association of State and Health Territorial Health Officials. State approaches to community health worker certification (2024). Available online at: https://www.astho.org/topic/brief/state-approaches-to-community-health-worker-certification/ (Accessed April 11, 2025).

17. Gorman, B. State policies bolster investment in community health workers. Association of State and Health Territorial Health Officials (2023). Available online at: https://www.astho.org/communications/blog/state-policies-bolster-investment-in-chw/ (Accessed April 11, 2025).

18. U.S. Department of Health and Human services. HHS announces $226.5 million to launch community health worker training program. (2022). Archived HHS content. Available online at: https://public3.pagefreezer.com/browse/HHS.gov/01-01-2023T06:35/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/04/15/hhs-announces-226-million-launch-community-health-worker-training-program.html (Accessed April 11, 2025).

19. Kim, K, Choi, JS, Choi, E, Nieman, CL, Joo, JH, Lin, FR, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:e3–e28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987

20. Zionts, A. Community health workers spread across the US, even in rural areas. KFF Health News (2024). Available online at: https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/community-health-workers-rural-america/ (Accessed April 11, 2025).

21. Askari, N, Bilbrey, AC, Garcia Ruiz, I, Humber, MB, and Gallagher-Thompson, D. Dementia awareness campaign in the Latino community: a novel community engagement pilot training program with promotoras. Clin Gerontol. (2018) 41:200–8. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1398799

22. Roth, E, and Atkeson, A Community health workers and oral health: improving access to care across the lifespan in Minnesota. National Academy For State Health Policy. (2022). Available online at: https://nashp.org/community-health-workers-and-oral-health-improving-access-to-care-across-the-lifespan-in-minnesota/ (Accessed April 11, 2025).

23. Alzheimer’s Association. Community health workers: a resource for healthy aging and addressing dementia. (2021). Available online at: https://www.alz.org/getmedia/01534d07-e0fb-470d-b2d3-747f6afcfda2/community-health-workers-a-resource-for-healthy-aging-and-addressing-dementia.pdf (Accessed April 11, 2025).

24. Alam, RB, Ashrafi, SA, Pionke, JJ, and Schwingel, A. Role of community health workers in addressing dementia: a scoping review and global perspective. J Appl Gerontol. (2021) 40:1881–92. doi: 10.1177/07334648211001190

25. Krantz, MJ, Coronel, SM, Whitley, EM, Dale, R, Yost, J, and Estacio, RO. Effectiveness of a community health worker cardiovascular risk reduction program in public health and health care settings. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:e19–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301068

26. Spencer, MS, Rosland, AM, Kieffer, EC, Sinco, BR, Valerio, M, Palmisano, G, et al. Effectiveness of a community health worker intervention among African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:2253–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300106

27. Kenya, S, Jones, J, Arheart, K, Kobetz, E, Chida, N, Baer, S, et al. Using community health workers to improve clinical outcomes among people living with hiv: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. (2013) 17:2927–34. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0440-1

28. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Guiding an improved dementia experience (GUIDE) model. Available online at: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/guide (Accessed April 11, 2025).

29. Kallmyer, BA, Bass, D, Baumgart, M, Callahan, CM, Dulaney, S, Evertson, LC, et al. Dementia care navigation: building toward a common definition, key principles, and outcomes. Alzheimers Dement. (2023) 9:e12408. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12408

30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BOLD infrastructure for Alzheimer’s act. Alzheimer’s disease program. (2024). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/aging-programs/php/bold/index.html (Accessed April 11, 2025).

31. Alzheimers Association and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National healthy brain initiative state and local road map for public health, 2023–2027. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/aging-programs/media/pdfs/2024/06/HBI-State-and-Local-Road-Map-for-Public-Health-2023-2027-508-compliant.pdf (Accessed April 11, 2025)

32. Smithwick, J, Nance, J, Covington-Kolb, S, Rodriguez, A, and Young, M. Community health workers bring value and deserve to be valued too: key considerations in improving CHW career opportunities. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1036481–1. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1036481

33. Reinschmidt, KM, Philip, TJ, Alhay, ZA, Braxton, T, and Jennings, LA. Training community health workers to address disparities in dementia care: a case study from Oklahoma with national implications. J Ambulatory Care Manage. (2023) 46:272–83. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000470

34. Haldar, S, and Hinton, E State policies for expanding Medicaid coverage of community health worker (CHW) services. KFF. (2023). Available online at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-policies-for-expanding-medicaid-coverage-of-community-health-worker-chw-services/ (Accessed April 11, 2025).

35. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS finalizes physician payment rule that advances health equity. November 2, (2023). Available online at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-finalizes-physician-payment-rule-advances-health-equity (Accessed April 11, 2025).

36. South Carolina Community Health Worker Association. CCHW recertification. Available online at: https://www.scchwa.org/recertification-and-tiers (Accessed April 11, 2025).

Keywords: chronic disease, community health workers, dementia, public health, workforce, social determinants of health

Citation: Johnson E, Lewis M, Nordyke A, Lee M, Roberts S, Gaugler JE and Borson S (2025) Community health workers: developing roles in public health dementia efforts in the United States. Front. Public Health. 13:1616404. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1616404

Edited by:

Christiane Stock, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Zeina Chemali, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Johnson, Lewis, Nordyke, Lee, Roberts, Gaugler and Borson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elma Johnson, ZWxtYWJqQHVtbi5lZHU=

Elma Johnson

Elma Johnson Mickal Lewis

Mickal Lewis Alexandra Nordyke

Alexandra Nordyke Matthew Lee

Matthew Lee Shelby Roberts

Shelby Roberts Joseph E. Gaugler

Joseph E. Gaugler Soo Borson

Soo Borson