- Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Environmental Health, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Introduction: The World Health Organization African Region (WHOAFRO) Transformation Agenda initiated in 2015 has emerged as an important health leadership strengthening initiative in pursuing the 2030 health Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and universal health coverage. However, there remains need for research narrating health policy lessons from implementing it with a focus on Pro-Results Values, Smart Technical Focus, Responsive Strategic Operations, and Effective Communications and Partnerships, for just and sustainable public health systems in pursuing universal health coverage.

Aim: This study explored health policy lessons from the implementation of WHOAFRO Transformation from 2020 to 2023, and how this may help reinforce health systems governance on the continent.

Methods: This paper is generated from a wider study commissioned by WHOAFRO. The study design used was exploratory and qualitative. Secondary data were collected from publicly available purposively selected WHO documents. Narratives were first generated from the data, followed by coding and then thematic analysis.

Results: Training and mentorship helped strengthen skills levels amongst health leaders which helped contribute efficiently toward Pro-Results Values. Interventions were directed to align with continental health system leadership goals for Smart Technical Focus. Leadership structures and systems were streamlined to strengthen organizational functions for the delivery of desired outcomes to achieve Responsive Strategic Operations. Collaboration with donors and health system governance partners at all levels helped broaden the resource base, which was complemented by the adoption of digital tools and hybrid work arrangements for Effective Partnerships and Communication.

Discussion and conclusion: Transforming health leadership in the Africa Region requires sustained effort to train health leaders to help strengthen health systems governance toward meeting the healthcare needs of the population. There is need for continued reinforcement of ethics values amongst health leadership to maintain a high moral standards for health workforce protection. There is also a need to sustain innovativeness in incorporating digital tools and hybrid work models into health governance for effective and efficient communication in health system leadership work. Strengthening partnerships between actors at all health governance levels helps contribute toward resource mobilization required for health system functioning for just and sustained pursuit of universal health coverage.

1 Introduction

Transformation of the World Health Organization (WHO) Secretariat in the African Region, is a health leadership strengthening initiative launched by the WHO Africa Regional Director in 2015, and endorsed by the Sixty-fifth session of the Regional Committee for Africa. The aim of this health governance capacity strengthening intervention is to help reinforce healthcare systems across the continent in pursuing the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with a particular focus on Goal 3, and toward the realization of universal health coverage (1). The vision behind transformation is the emergence of a capacitated, adequately resourced, appropriately equipped, foresighted, results-driven, effective, efficient, transparent and accountable WHO that staff and stakeholders want, and one that is a primary leader in the preparation for and response to Public Health Emergencies of International Concern, and in delivering its mandate to strengthen country-level health systems on the continent toward meeting the healthcare needs and expectations of the population in a just and sustainable manner (2–4).

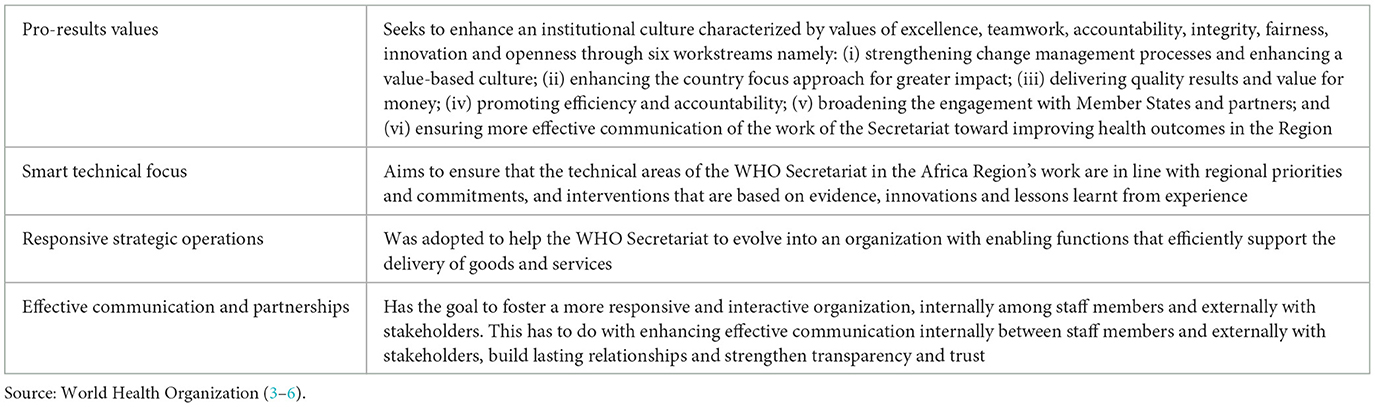

There has so far been four phases through which Transformation of the WHO Regional Office for Africa has been implemented. In the initial phase, implemented between 2015 and 2018, the focus was on creating the WHO that stakeholders want and deserve (5, 6). This was followed by a second phase, from 2018 to 2020, which focused on placing people, staff and populations in Member States at the center of change with the aim of transforming the Secretariat's organizational culture for country-level impact. In phase three (2021 to date), the aim is to consolidate the transformation through institutionalization of change (1, 3, 7). These three phases resulted in the formulation of four integrally connected focus areas within which progress in the transformation process was to be made. These four focus areas, outlined in Table 1, include Pro-Results Values, Smart Technical Focus, Responsive Strategic Operations, and Effective Communications and Partnerships (3–6).

However, whilst transforming the WHO Secretariat in Africa has made considerable progress, the outbreak of the Coronavirus Disease of 2019 (COVID-19), declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by WHO on 30 January 2020, and a pandemic on 11 March 2020 affected implementation (3, 7). Even though the WHO Director General through the 15th meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic held on 4 May 2023 ended the WHO PHEIC declaration, taking effect from 5 May 2023, there remains room for research exploring the health policy lessons from the implementation of WHO Transformation during public health emergencies of international concern with a particular focus on the Africa Region Secretariat (2020–2023) and how this may help in health leadership strengthening in pursuing healthcare system goals (7, 8). In this regard, this paper explores the emerging health policy lessons focusing on the four focus areas of the WHO Transformation Agenda, and how this may help reinforce health systems in pursuing Sustainable Development Goal 3, Good Health and Well-Being, to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages, and universal health coverage. For this purpose, health policy is defined as purposive course of action and interventions undertaken by health leadership with the goal to enable health systems strengthening and functioning so as to achieve desired health outcomes. Health governance in the context of this paper is defined as health systems leadership to enable the strengthening and functioning of the healthcare system, structure and processes for the achievement of health goals (3).

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

An exploratory qualitative research design was used. In this, the aim was to explore the health policy lessons which emerged in the four focus areas from the implementation of the Transformation Agenda of the WHO Africa Secretariat (9).

2.2 Research setting

This paper is generated from a study commissioned by the WHO Regional Office for Africa titled “The Transformation Agenda of the WHO Secretariat in the African Region 2020–2023: Reflecting on health policy lessons from COVID-19 toward reinforcing health system strengthening for achieving universal health coverage by 2030.”

2.3 Units of analysis and data collection

Secondary data were sourced from a publicly available dataset accessed from the Transformation Section of the WHO Regional Office for Africa website (10, 11). In this, the units of study were WHO Africa policy documents, annual reports and committee reports narrating the implementation of the Transformation Agenda by the WHO Regional Office for Africa between 2020 and 2023 (11). These policy documents were purposively selected for this study. Thereafter, a documentary search was carried out to establish the health policy lessons which emerged from implementation and how they may help reinforce health governance for the realization of healthcare system strengthening in the WHO Africa Region and beyond (9).

2.4 Presentation and analysis of data

Narratives of the qualitative data collected were first generated manually before being coded. Thereafter, the coded narratives were then subjected to interpretive thematic analysis. However, we established that there were quantitative figures in the dataset and we used these to support qualitative narratives (9, 10).

3 Results

3.1 Pro-results values

It was established that the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) initiative was implemented during this period (2020–2023). DEI implementation resulted in the number of Female Team Leads, Heads of Country Offices and Directors increasing by 6.6% from 24.2% in 2020 to 30.8% at the beginning of 2022. Additionally, a second exclusive female staff cohort of the WHO Africa Pathways to Leadership Programme, an intensive 3-month programme launched toward the end of 2021 to help strengthen leadership skills for teamwork, communication and coaching, and enabling the trainees to create a leadership vision aligned with WHO or ministries of health values, outlined in Table 2, resulted in an increased percentage of female staff equipped with the requisite leadership competencies to effectively transform Africa's health from 38% in 2019 to 48% in 2022 (12). In 2023, this Pathways to Leadership for Health Transformation Programme was also extended to other regions of the WHO and health ministries. In that, a cohort of 20 senior staff from the European Region, a joint WHO Africa/Europe Cohort of 23 senior staff, and another joint Africa/Europe Cohort of 20 WHO Representatives (WRs) and staff on their roster were trained. Benin also launched its first Cohort of Directors during the same period whilst WHO Ghana devoted its fourth cohort to women thereby resulting in an all-female cohort for the leadership programme at country-level with the goal. In this, Ghana sought to enhance the leadership skills of women in the health sector and to align its interventions with the agenda of the Ministry of Health in order to allocate 60% of leadership training opportunities to women (13).

Furthermore, the Women in Leadership Speaker Series launched during the same period enabled women to interact with female leaders in global development and to acquire skills to handle professional and other leadership challenges. We also noted that the Women in Leadership Speaker Series helped bring together WHO staff, regardless of their gender, and high-ranking African female leaders who worked in the health and development to engage in candid career advancement and leadership development conversations. Feedback from participants of the three sessions of this series conducted between November 2021 and April 2022 revealed improvements in female staff confidence levels and a growing sense of belonging. We also established that the Mentorship Programme launched its third cohort during the same period, a new milestone for this intervention. This programme was also acknowledged within WHO globally as one of the best initiatives that supported staff in building their capacity based on their professional and career development needs. From this, 300 Mentees from the WHO African Region and 140 Mentors from across all WHO major offices including WHO headquarters were successfully matched and achieved the key outcomes of the Mentorship Programme by 2022 (12). To further strengthen this intervention, the WHO Africa Mentorship Programme, along with the WHO in Africa Team Performance Programme were, in 2023, incorporated into staff development and learning activities through an approach that emphasized the need to streamline and integrate training through a one-tool, one-concept and one-mentor strategy. In the same year, the Mentorship Programme launched its Fourth Cohort, with 99 Mentees and 37 Mentors. To consolidate awareness and a culture of feedback among managers, a second round of 360-Degree Feedback was conducted among WHO Country Representatives and Operations Officers. Eleven Regional Office units and three countries conducted the team performance feedback sessions to identify ways and means of consolidating change achievements (13).

Transformation during the 2020–2023 period also showed the need to uphold WHO values and ethics standards. In this, the Prevention and Response to Sexual Exploitation, Abuse and Harassment (PRSEAH) was initiated to help prevent and address harassment and abuse of authority. An Ombudsman and a Regional Coordinator were recruited in the first quarter of 2022 to help reinforce the implementation of PRSEAH (12). A total of 253 training sessions with staff and 1021 sessions with communities were also carried out since 2021, resulting in more awareness and meaningful conversations on this challenge and incorporation into operational processes for staff wellbeing (5). To further protect workers, WHO introduced workplace mental health initiatives to protect the mental wellbeing of staff members in order to sustain and improve their productivity during COVID-19 and cope with the shift to virtual and hybrid working. Two Staff Counselors and a Staff Development and Learning Officer were recruited to help support both staff and managers in their mental welfare (12). Good transformation practices were also shared within WHO through meetings and communication, and Cross-Functional Teams. This brought together staff from different departments and locations to share perspectives, skills and experiences. Furthermore, we established that these practices influenced global transformation and are being replicated across WHO, while the WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region has gone on to provide leadership training for staff from other WHO regions (5).

3.2 Smart technical focus

It was established that the COVID-19 pandemic showed the importance of close partnership between the WHO Secretariat and its country offices to fast-track country-level transformation initiatives and to enhance WHO country presence and health sector leadership. In pursuing this, progress was made through the completion of functional reviews across the 47 country offices and Regional Office clusters as outlined in Table 2. Efforts to bring timely, high-quality technical support closer to countries culminated in the establishment of 11 Multi-Country Assignment Teams who brought specialized technical experts to work closely with the country offices to scale up technical support across eight critical health areas during this period. The WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region also used the COVID-19 pandemic data and experiences of 2019–2023 to fast-track the strengthening of national public health security capacities required for the preparation for and response to the region's extensive public health emergencies (12). On this, it was established that by April 2022, all the 47 Member States had Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) laboratory capacity for confirming COVID-19 whilst 39 Member States with the exception of Angola, Burundi, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Comoros, Eritrea, Liberia and South Sudan, had sequencing capacity for identifying circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants. In addition, the Secretariat strengthened COVID-19 preparedness, readiness and response capacities, including developing and providing access to authoritative case management guidance, deployment of 809 experts and training of 200,000 community health workers in risk communication across the Region. Consequently, this resulted in a drop in case fatality ratios by one percentage point by the end of 2021, a figure which was closer to the 1.4% global average (12).

Significant progress was also made from interventions to end all forms of Polio in the WHO Africa Region with over 139,703,101 children under 15 years of age in nine Member States vaccinated against potential outbreak and circulation of Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Type 2 (cVDPV2). In August 2020, the independent Africa Regional Certification Commission (ARCC) officially declared the WHO African Region free of indigenous wild poliovirus. This achievement was attributed to the leadership of Member States, effective collaboration among polio partners, and the adoption of innovative approaches, such as the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to strengthen surveillance (5, 12). The WHO Regional Office for Africa also responded to the Ebola outbreak in Guinea, and supported the vaccination of 11,000 people which helped curtail the spread of the disease. In addition, the WHO Secretariat deployed 40 Programme Management Officers (PMOs) and 33 External Relations Officers (EXOs) to 47 WHO Country Offices which helped strengthen technical assistance and empowered WHO Country Teams to deliver country-level impact (12).

The WHO Regional Office for Africa also established three flagship programmes, namely Promoting Resilience of Systems for Emergencies (PROSE), Transforming Africa's Surveillance System (TASS), and Strengthening and Utilizing Response Groups for Emergencies (SURGE), to help respond to emergencies as part of its Smart Technical Focus. During 2022, seven dedicated National Emergency Response Teams were trained on different emergency response modules and equipped with the necessary response resources and technology. This enabled them to respond in a timely and effective manner to the emergency outbreaks of Rift Valley Fever in Mauritania, Polio in Botswana, Cholera in Niger and Meningitis in Togo. In addition, the WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region conducted risk assessments and contingency planning exercises in 19 countries in anticipation of and preparation for potential emergencies. Furthermore, the WHO Regional Office for Africa also launched the Mwele Malecela Mentorship Programme for Women in Neglected Tropical Diseases in October 2022, to strengthen the professional growth of individuals in the field of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs). This programme provided mentees with the opportunity to work with experienced mentors and receive guidance, advice and support in their careers for skills development, exposure to new ideas and perspectives, and relationship building within the NTD community. The overall aim was to provide them with the resources and support they required to succeed in their careers, become influential leaders and make a positive impact toward the prevention and control of NTDs in Africa. The WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region also recorded how country offices, in collaboration with partners continued to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic in West and Central Africa, and monitored Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) coverage in the Region throughout the time between 2020 and 2023. From this, it was established that although several countries in West and Central Africa achieved 90% coverage for ART, progress in the control of the HIV/AIDS epidemic was hindered by insufficient political commitment, health system weaknesses and serious health challenges such as the outbreak of COVID-19 and Ebola (13).

3.3 Responsive strategic operations

During the 2020-23 period of the COVID-19 outbreak, the WHO Regional Office for Africa responded to the growing demand from Member States to strengthen leadership and change management competencies by expanding the Pathways to Leadership for Health Transformation Blended Programme, outlined in Table 2. This blended programme was piloted in Congo, and to senior ministry of health officials in Ghana, Lesotho and Niger. From this, 100 health ministry participants were trained and applied their newly acquired skills in strengths-based leadership and systems thinking to lead health system recovery efforts and address some of the core health challenges which affected their population. In addition, digital tools such as Microsoft Teams helped facilitate organizational agility, remote work and enhanced efficiency by helping WHO teams to remain connected and focused during the COVID-19 lockdown. This was complemented by the introduction of a new Translation Management System (TMS) which led to efficiencies in the processing of translation requests. Furthermore, digital solutions were rapidly scaled up across the Secretariat's operations thereby resulting in over 350,000 field workers and more than 200,000 polio campaign workers across 16 Member States moving from cash to digital payments. In turn, this resulted in improved cost effectiveness, reduced lag time in financial reporting and reduced inequities through financial inclusion of the rural poor. In addition, diligence in enhancing internal accountability, demonstrating value for money and tracking the immediate gains of health interventions along with the Secretariat's efforts to secure long-term agreements and broaden the supplier base which resulted in the generation of approximately US$ 1.6 million and contributed to a strengthened WHO supply chain in the African Region by the end of 2021 (12).

To further enhance internal accountability so as to ensure value for money, the WHO Africa Secretariat introduced the Mid-term Review Tool, defined performance metrics and goals for health interventions, and regular monitoring and evaluation of progress against these metrics. In addition, the Secretariat's robust financial management systems and processes, including budgeting, forecasting and reporting, helped ensure effective resource allocation and use. In this, risk, compliance, administrative reviews and internal audits were conducted in 14 countries to promote a culture of transparency and accountability and ensure compliance with policies and procedures. Furthermore, a follow-up of the 14 internal and four external audit report recommendations of the previous year corroborated the implementation of appropriate actions to address the identified issues and internal control gaps. Risk management briefings and training sessions for multiple and targeted budget center personnel to strengthen and create a regional risk culture complemented the assurance activities conducted in 26 budget centers (5, 13).

The WHO Regional Office for Africa also fostered stakeholder feedback to teams in six dimensions: WHO values; effectiveness; quality; cost consciousness; agility and change management; and collaboration, all as part of the efforts to effectively consolidate the change initiated under the Transformation Agenda. The objective was to enhance team effectiveness by highlighting strengths and growth areas, improving communication through constructive comments and increasing motivation and engagement. The feedback from this enabled teams to fully understand where they stood in terms of implementing change, locating transformation challenges and focusing on the most impactful actions. Twelve units and two clusters in the Regional Office and four WHO country offices (Benin, Sao Tome, Algeria, and South Sudan) used lessons learnt from the feedback to tackle collective performance challenges. To address COVID-19 pandemic-related needs amongst staff, the WHO Regional Office for Africa apart from promoting mental health, it fostered a healthy work environment by supporting its staff and their dependants through providing counseling and psychological services, and through the establishment of clinical sites for testing and vaccination against the disease. The convenient locations of the vaccination sites resulted in high levels of staff vaccination coverage, reaching over 95% by 2022. Collaboration tools to facilitate hybrid meetings were also introduced to help cope with the COVID-19 lockdown. All this helped improve staff productivity and flexibility in work arrangements. In addition, the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines in the WHO Africa Region resulted in the need for improvements in vaccine regulatory capabilities and capacities of Member States. The Secretariat initiated consultations with the African Vaccine Regulatory Forum (AVAREF) comprising of national regulatory authorities of all Member States. As a result, AVAREF endorsed an emergency joint review process and shortened timeline to accelerate the development of COVID-19 diagnostics, vaccines and medicines (13).

3.4 Effective partnerships and communications

It was established that transforming the approach to partnerships and resource mobilization focused on scaling-up the region-wide roll-out of the Digital Contributor Engagement Management System (DCEMS), outlined in Table 2. This system provided an added opportunity through which to access pipeline financing information, leverage different funding sources and investments and diversify the WHO funding base, thereby contributing to an increase in diversified funding from a broad range of philanthropic and new donors. More than 200 staff were trained in the use of the Contributor Engagement throughout 2022 (12). The WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region strengthened partnerships for the COVID-19 response. These included traditional partners, and governments of countries such as Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Japan, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the European Commission, Rotary International, the African Development Bank and the World Bank. WHO also worked closely with the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), through the Africa Taskforce for Coronavirus (AFTCOR), the African Vaccine Delivery Alliance (AVDA) and the African COVID-19 Vaccine Readiness and Deployment Taskforce (ACREDT), to support coordination of the pandemic response (5, 12–14).

Partnerships were also strengthened with member organizations of the Harmonization for Health in Africa (HHA) mechanism through the new Framework for Better Collaboration and Greater Impact at Country Level 2022–2023. Furthermore, the HHA mechanism undertook a mapping exercise in 39 countries to assess the effectiveness of partner coordination and collaboration at country level, address coordination and harmonization challenges and define workable solutions for COVID-19 response. These partner transformation efforts resulted in the mobilization of over 30% (US$ 622 million) of the allocated budget for the 2020–2021 biennium for the Region (US$ 1.7 billion) directly by the WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region (12). Partnerships also resulted in the mobilization of over US$ 3.5 million toward COVID 19 pandemic support to Member States in 2021. In addition, partnerships and resource mobilization capacities of the Secretariat resulted in US$ 331.8 million mobilized for the WHO pandemic response in the African Region. This represented 72.8% of the overall budget of US$ 455.9 million in the same year. The WHO in Africa Regional Office also increased collaboration with non-State actors, signing 112 agreements worth over US$ 60 million for efficient strategy implementation. Partnerships were forged with civil society organizations and NGOs to reach the most vulnerable and remote populations (12, 15).

To help ensure effective communication of the WHO goal toward improved health outcomes since the onset of the pandemic, over 50 virtual press conferences and more than 450 media interviews involving 270 global media outlets and over 70 regional and national media organizations were delivered by the WHO Secretariat for the Africa Region. This enabled the sharing of life saving information, enhanced stakeholder engagement and demonstrated the WHO Africa Region Secretariat's health leadership. The WHO Regional Office for Africa also experienced a significant increase in followers across its social media platforms throughout the pandemic with Facebook followers increasing by 1.5 million. Visitors to the WHO Regional Office for Africa's secretariat website also increased by 283% from 1.2 million in 2019 to 4.6 million visitors in 2020. Cross-cutting internal communications on the Transformation Agenda and change management efforts also increased through the monthly “Change Management Highlights,” internal newsletters and the WHO Africa Regional Director's Townhall Meetings (5). The WHO Secretariat in Africa Region also advocated for the addressing of pressing issues such as COVID-19 vaccine equity by targeting a range of key influencers with different communication products. It also promoted healthy COVID-19 practices such as wearing of face masks, and proper hand washing, and disseminated over 200 videos. More than 90 of these videos received at least one million views on the WHO Regional Office for Africa's social media platforms, mainly Facebook and Twitter. These platforms grew by 1.129 million followers compared to the annual target of 600,000. Thirty-two newsletters showcasing key elements of the pandemic response were disseminated to ministries of health, United Nations agencies and donors with a unique open rate of nearly 40%, representing a 10% increase from the previous year. In a bid to fight COVID-19 misinformation and complement public health awareness and community engagement in the WHO Africa Region, the African Infodemic Response Alliance (AIRA) was launched by the WHO Regional Office for Africa in 2020. AIRA immediately grew in membership from 13 to 1,514. The Viral Facts Initiative which emerged from this was used as a communication tool to dispel myths, misconceptions and disseminate trustworthy COVID-19 messages (12). In this, the AIRA COVID-19 social content hub produced and disseminated over 100 different pieces of digital content countering damaging public health misinformation in Africa in multiple languages, and in the process generated over 95 million views. In addition, the WHO Secretariat for the Africa Region bolstered its external communication through a significant improvement of its online presence and brand image by revamping its website with new theme-focused pages to diversify content. This resulted in an increase in the average time spent on the website by 27%. The WHO Regional Office for Africa also launched a micro-website on the achievements of the Transformation Agenda, and increased its social media presence and engagement, which also enabled it to reach an audience of over 150 million through 29 media campaigns and better connection with its stakeholders and partners (12, 13).

To enhance accountability and transparency in its communication with donor partner, the WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region shared donor-focused communication products across various external platforms, including social media and the WHO Regional Office for the Africa Region website, in 2022. A total of 24 donors were acknowledged, and close to 250 communication products were published, including human interest stories, press releases and videos, as well as posts on Facebook and Twitter. These efforts reached a broad audience of over 6 million people, including donors and partners, the media and the general public. In addition, WHO Secretariat for the Africa Region recruited eight External Relations Officers, who leveraged their expertise to identify funding opportunities and developed proposals aligned with the needs of Member States. The increased focus on strengthening accountability and reinforcing trust with donor partners helped to further the WHO Regional Office for Africa's mission toward improved health outcomes for the continent during this period, 2020–2023. In 2022, the WHO Secretariat in Africa introduced a regular reporting and feedback mechanisms and organized over 60 partner briefings to foster a better understanding of its work, and collaborations. This resulted in the mobilization of new funding which amounted to US$422 at the country levels. To sustain leadership development among managers in health ministries and to expand and sustain the Leadership for Health Transformation Programme, the WHO Secretariat for the Africa Region partnered with academic institutions which included the Ashesi University in Ghana and the University of Pretoria in South Africa. Furthermore, the Secretariat increased collaboration with other United Nations agencies by entering into 31 agreements, joint programmes for synergistic actions and leveraging each agency's comparative advantage toward improving health outcomes in the region (13).

4 Discussion

The implementation of the Transformation of the WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region during the 2020–2023 period provides important lessons which may help reinforce the pursuit of the goals of Pro-Results Values, Smart Technical Focus, Responsive Strategic Operations, and Effective Partnerships and Communications (8). Health governance transformation is central to improving health system performance, in preparing and responding to public health emergencies, and in pursuing SDG 3, and universal health coverage in the Africa Region and beyond (16, 17). The first theme emerging from in discussion is that achieving Pro-Results Values of the WHO Transformation in the Africa Region requires a well-trained healthcare workforce, to lead the strengthening of country-level health systems so as to ensure the delivery of healthcare services to the population (18). In this regard, health leadership transformation equips health system leaders with knowledge and skills in organizational, team and personal management, enhance strategic and analytical capacity, and help them gain greater understanding of the complex issues encountered in governing health systems at all levels (7). However, studies on this area also emphasize the importance of training relevant to purpose, based on an understanding that there is a chain that links effective learning to high-quality services and thus to improved health. In this regard, it is important to continually and systematically examine the training of the WHO Secretariat in Africa to help ensure that it remains fit-for-purpose (18).

In addition, the study of WHO Africa Transformation (2020–2023) shows the importance of complementing basic training with mentorship programmes. Mentorship helps bridge the gap between the knowledge and skills acquired through training and practice in health leadership. However, there is need to ensure that mentorship programmes and mentoring expectations are clear and understood by both mentees and mentors. This can be achieved through discussions, learning contracts outlining mentorship outcomes and individualized development plans. Another challenge involves the establishment and maintenance of rapport between the mentors and mentees. This can be addressed through increased frequency of virtual meetings during public health emergencies of international concern. Virtual training and mentorship may however be affected by logistical challenges which may include unreliable, and often unavailable electricity supply, and unstable internet connections in some parts of Africa, and other resource limited settings around the world. One way to get around these challenges is to provide access to downloadable presentations and modules that can be viewed asynchronously, while simultaneously participating verbally through low bandwidth applications, such as WhatsApp. Internet-based training may also mitigate challenges such as cost, delay and/or inability to obtain visas to travel abroad for training, which can be amplified by the closure of country borders and embassies granting travel visas during the outbreak of diseases constituting public health emergencies of international concern. Another challenge that can be encountered in mentorship programmes is meeting the needs of trainees with different levels of technical capacity at the outset and with varied competency needs, while at the same time ensuring a diversity of trainee backgrounds, sustainability of training, and harmonization of the trainee's research and practice activities with the needs and priorities of the country where they work. This challenge can be addressed through involving local mentors in the recruitment and selection of trainees, mentoring activities and management of the program (19). Finally, training for Pro-Results Values needs to mainstream gender by reinforcing diversity, equity and inclusion with a particular focus to increase the number of women receiving training in health governance to help and ensure that more women occupy higher-level healthcare leadership positions at the WHO Regional Office in Africa, and in country offices (7). This aligns with Resolution WHA74.14 titled, Protecting, safeguarding and investing in the health and care workforce adopted at the Seventy-third World Health Assembly (WHA) of 2021, prescribing the creation of opportunities for women in the health workforce, that support their full and meaningful participation and representation, including in senior leadership and decision-making roles (20).

Our second theme is that WHO Transformation, particularly in the Africa region, needs to sustain the instilling of ethics values and standards into health leadership to help maintain a high moral and ethical standard of work for health workforce protection in line with Resolution WHA74.14 of 2021 for Pro-Results Values. Resolution WHA74.14 of 2021 calls for the safeguarding and protection healthcare workers through equitable distribution and access to PPE, therapeutics, vaccines, diagnostics, effective infection prevention, control and occupational safety and health measures within a safe and enabling work environment that is free from racial and all other forms of discrimination. In addition, this resolution also called for the prevention of violence, discrimination and harassment, including sexual harassment against healthcare workers, the majority of whom (almost 70%) are women (20). This is also in line with Resolution WHA74.14 of 2021 prescribing member states to take measures for their protection in the workspace. The implementation of the Transformation Agenda by the WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region shows the importance of creating and promoting a healthy work environment through workplace interventions which include the establishment of clinical sites providing workplace health initiatives and equipped with specialist healthcare professionals to provide counseling and psychosocial services for mental wellbeing, and testing, vaccination and if possible treatment or referral to health facilities (2, 21, 22). Furthermore, protection against discrimination, racism, tribalism, harassment, sexual exploitation and violence can be reinforced through awareness creation and meaningful conversations about the challenge amongst staff within the WHO Africa Secretariat and with stakeholders at regional, country and community levels to cultivate culture-specific, action-oriented and results-focused solutions for harmony. These can then be transformed into ethics standards, operating guidelines, protocols and regulations, for implementation in the workplace at WHO Secretariat level, in country offices, and health establishments to help protect all healthcare workers (20–22).

Theme three is that transformation of the WHO Secretariat needs to be proactive in adopting and sustaining digital tools, and in applying need-based hybrid work arrangements into health governance for Responsive Strategic Operations. The implementation of the Transformation Agenda by the WHO Regional Office for Africa between 2020 and 2023 shows that adoption of computer-based communication software such as Microsoft Teams, along with assistive Translation Software Systems, facilitate the continuation of normal day to day office communication through a digital platform for virtual meetings, broadcast of live video streams, and quick sharing of data and information during the outbreak of public health diseases of international concern which may have resulted in lockdowns, necessitating members of the Secretariat to working either in isolation from home or through a hybrid work model for productivity (12, 13). Studies suggest that Microsoft Teams has been a radical approach to digital implementation in healthcare which has so far proved effective in delivering a cost effective and rapid communication tool during the outbreak of global pandemics of public health concern (23).

Furthermore, digital tools also help facilitate connection and presence of the WHO Regional Office for Africa in society and communication with donor, partners and the world. For example, websites and social media accounts are not only information platforms but also a means through which to maintain connection with the society through followers, subscribers and interaction, through for example live virtual discussions on Facebook and Spaces on X (Twitter) for WHO presence in society. Social media platforms complement mainstream media platforms for wider delivery of information through press conferences (virtual or in-person), media interviews, and healthcare programme specific interventions. In turn this effective communication also helps complement interventions such as the Viral Facts Initiative in countering misinformation which may under otherwise undermine effective implementation of donor-focused communication products and health interventions, such as COVID-19 vaccines (12). Digital tools also help facilitate the generation of accurate, reliable, complete, consistent and timely health data to help inform effective planning and resource management in the WHO Transformation process. For instance, the transition to digital payments to healthcare workers helping the WHO Regional Office for Africa to pay community-level healthcare workers implementing interventions in different locations in the region in a timely, cost effective but also a transparent and accountable manner which in turn is also making it easy to track gains and value for money from the healthcare initiatives being implemented in the region, which in turn also helps in audits, reviews, monitoring and evaluation, and makes it easy to provide stakeholders feedback to help maintain and expand the donor base. Mobile money technology can also be used to generate heathcare data such as for monitoring and evaluation from Community Health Workers which could be integrated with Health Information Systems (HIS) within countries for improved efficiency (12, 13).

Our last theme is that transforming health governance needs to maintain and reinforce the principal-agent relationship and expand partnerships with society, governments and donor community for resource sharing and mobilization to strengthen Smart Technical Focus, and for Effective Partnerships and Communication. The principal-agent relationship between the WHO Secretariat in the African Region and in-country offices, including ministries of health, their partner ministries within countries and health governance structures therein down to the individual level within households level need to be maintained and reinforced. One main way through which to achieve this is through maintaining WHO presence for the provision of timely, responsive and relevant technical support to all health system leadership levels and ensuring community involvement and inclusion through wide decision space for responsiveness and acceptability of health interventions (12, 24). On this, a qualitative study in Kenya revealed that Community Health Committees (CHCs) are a mechanism through which communities can voluntarily participate in making decisions and providing oversight of the delivery of local healthcare services. This study however noted that for CHCs to succeed, health leadership needs to implement policies that promote wider decision space for community participation (25). This can be further reinforced by expanding collaborations with the community, governments and partnerships for resource mobilization and sharing. Partnerships with the society helps to mitigate health workforce shortages, a key health system challenge in health systems in the Africa Region. For example, a cross-sectional study carried out in Dhaka, Bangladesh, showed that household testing for SARS-CoV-2 detection by community health workers in low-resource settings is an inexpensive approach that can increase testing capacity, accessibility and the effectiveness of control measures through immediately actionable results (26). In addition, a qualitative study of Epworth, Zimbabwe reported that, despite resource constraints, community health volunteers remain an important resource through which to help complement health professionals in resource limited peri-urban areas (27). Resource constraints in transforming health systems can be mitigated by engaging and collaborations between governments and the donor community. On this, Development Assistance for Health (DAH) remains an important mechanism for funding and technical support from bilateral donors, centrally funded mechanisms, and philanthropic foundations for implementing health programmes in to lower-income countries. However, the donor-recipient dichotomy may at times create power imbalances which may result in the misalignment of priorities, short-term and often complex funding structures and processes, and a fly-in fly-out approach which can undermine aid effectiveness, WHO capacity strengthening efforts and sustainability. Call for reforming development assistance are not new to the global health community and have resulted in the formulation of aid effectiveness initiatives which include the International Health Partnership plus (2007), the Accra Agenda for Action (2008), the Busan Partnership for Effective Cooperation (2011), the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (2011), the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (2015), the Universal Health Coverage 2030 Global Compact (2017), and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which also underscores the need for a better aid model. Despite these global efforts, there has been little progress toward a more sustainable and effective model for delivering development assistance in the health sector. In this regard, the Transformation Agenda of the WHO Secretariat in the Africa Region presents an opportunity to reinforce ongoing efforts to address this challenge, toward a sustainable and effective model through which development assistance for health can be delivered in pursuing systematic and outcome-oriented health governance for strengthening of health systems in the preparation for and response to public health emergencies of international concern, and programme specific healthcare interventions for the achievement of universal health coverage and Goal 3 of the Sustainable Development Agenda in particular (28).

5 Conclusions

Implementing the Transformation of the WHO with a particular focus on the Secretariat in the Africa Region requires sustained effort to train healthcare personnel to lead health system reform in the region. In addition, the enforcement of standard operating norms and ethics values need to be sustained so as to protect the health workforce from violence, discrimination, harassment and harm. To complement this, there is need to sustain digital tools and hybrid work arrangements into the health leadership transformation process. In addition, it is also important to strengthen the role of women in leadership and mentoring in the region so as to help enhance and strengthen women leadership, participation and representation in decision making to help strengthen the caregiver role often played by women within families and society, and for responsive health policy interventions which help contribute toward meeting the healthcare needs of women, the family and the community. This can be further reinforced by maintaining in-country and in-community WHO presence for technical assistance, and collaboration with communities, governments and development assistance for health partners for resource mobilization and sharing to capacitate the WHO Secretariat for the realization of the health system strengthening goal of good health, equity, responsiveness in line with SDG 3, and for sustainability in pursuing universal health coverage.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

BT: Software, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Data curation.

Funding

The author declares that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This paper was generated from a research project titled “The Transformation Agenda of the WHO Secretariat in the African Region 2020–2023: Reflecting on health policy lessons from COVID-19 toward reinforcing health system strengthening for achieving universal health coverage by 2030,” which was commissioned and funded by the Transformation Implementation Unit (TAI) in the Office of the Regional Director (ORD) of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa (WHOAFRO).

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the WHO Regional Office for Africa for funding the project titled “The Transformation Agenda of the WHO Secretariat in the African Region 2020–2023: Reflecting on health policy lessons from COVID-19 toward reinforcing health system strengthening for achieving universal health coverage by 2030,” from which this research article was generated. In this, gratitude is also extended to the Transformation Implementation Unit (TAI) in the Office of the Regional Director (ORD) of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa (WHOAFRO) for commissioning this project. I also wish to thank the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, for the Department of Higher Education Training (DHET) University Capacity Development Grant (2024) and the Accelerated Mentorship Programme (AMP), which helped finance the participation and presentation of the research paper, from which this article was developed, at the 8th Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2024) held from the 18th to the 22nd of November 2024 at the Dejima Messe Conference Center in Nagasaki, Japan.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organisation (WHO). Fifth Progress Report on the Implementation of the Transformation Agenda of the World Health Organisation Secretariat in the African Region (2015-2020). Brazzaville: World Health Organisation, Africa RCf (2020). Report No.: AFR/RC70/4.

2. World Health Organisation (WHO). The Transformation Agenda of the World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO. Secretariat: Strategic Alignment in the African Region (2015-2023). Brazzaville: World Health Organisation (2023).

3. World Health Organisation (WHO). The Transformation Agenda of the World Health Organization Secretariat in the African Region 2015-2020. Brazzaville: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa (2015).

4. World Health Organisation (WHO). The Transformation Agenda of the WHO Secretariat in the African Region, 2015–2020 – Highlights of the Journey so Far. Geneva: WHO (2020).

5. World Health Organisation (WHO). Sixth Progress Report on the Implementation of the Transformation Agenda of the World Health Organisation Secretariat in the African Region. Brazzaville: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa (2021). Report No.: AFR/RC71/4.

6. World Health Organisation (WHO). The Transformation Agenda of the World Health Organization Secretariat in the African Region Phase 2: Putting People at the Centre of Change. Brazzaville: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa (2017). p. 1–35.

7. World Health Organisation (WHO). Transformation Agenda. Brazzaville: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa (2015). Available online at: https://www.afro.who.int/regional-director/transformation-agenda/about (Accessed October 13, 2023).

8. World Health Organisation (WHO). Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Brazzaville: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (Accessed October 21, 2023).

9. Jacobsen K. Introduction to Health Research Methods: A Practical Guide, 3rd Edn. Burlington: Jones and Bartlett Learning (2020).

10. Bowling A. Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health and Health Services, 4th Edn. Maidenhead, GB: Open University Press (2014).

11. Liamputtong P. Research Methods in Health: Foundations For Evidence-based Practice, 3rd Edn. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press (2010).

12. World Health Organisation (WHO). Seventh Progress Report on the Implementation of the Transformation Agenda of the World Health Organisation Secretariat in the African Region. Lome, Togo: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa, Africa RCf (2022).

13. World Health Organisation (WHO). Eighth Progress Report on the Implementation of the Transformation Agenda of the World Health Organisation. Gaborone, Botswana: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa, Africa RCf (2023).

14. World Health Organisation (WHO). Report on the Strategic Response to COVID-19 in the WHO African Region February–December 2020. Brazzaville (2020).

15. World Health Organisation (WHO). The Work of the World Health Organization in the African Region: Report of the Regional Director, 1 July 2019–30 June 2020. Brazzaville (2020).

16. Fryatt R, Bennett S, Soucat A. Health sector governance: should we be investing more? BMJ Glob Health. (2017) 2:e000343. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000343

17. Assefa Y, Gilks CF, van de Pas R, Reid S, Gete DG, Van Damme W. Reimagining global health systems for the 21st century: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. (2021) 6:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004882

18. Couper I, Ray S, Blaauw D. Ng'wena G, Muchiri L, Oyungu E, et al. Curriculum and training needs of mid-level health workers in Africa: a situational review from Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:553. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3362-9

19. Rodriguez DC, Jessani NS, Zunt J, Ardila-Gomez S, Muwanguzi PA, Atanga SN, et al. Experiential learning and mentorship in global health leadership programs: capturing lessons from across the globe. Ann Glob Health. (2021) 87:61. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3194

20. Assembly WH. Protecting, Safeguarding and Investing in the Health and Care Workforce (WHA74.14). The Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation (2021). p. 1–8.

21. Assembly WH. Seventy-third World Health Assembly: Resolutions and Decisions (WHA73/2020/REC/1). Seventy-third World Health Assembly 2020. Geneva: World Health Organisation (2020). p. 3-9.

22. World Health Organisation (WHO). Global Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery 2021-2025. Geneva: World Health Organisation (2021).

23. Mehta J, Yates T, Smith P, Henderson D, Winteringham G, Burns A. Rapid implementation of Microsoft Teams in response to COVID-19: one acute healthcare organisation's experience. BMJ Health Care Inform. (2020) 27:e100209. doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2020-100209

24. Taderera BH. Do national human resources for health policy interventions impact successfully on local human resources for health systems: a case study of Epworth, Zimbabwe. Glob Health Action. (2019) 12:1646037. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1646037

25. Taderera BH, Hendricks SJH, Pillay Y. Human resource for health policy interventions towards health sector reform in a Zimbabwean peri-urban community: a decision space approach. Int J Healthcare Man. (2018) 11:289–97. doi: 10.1080/20479700.2017.1407523

26. Sania A, Alam AN, Alamgir ASM, Andrecka J, Brum E, Chadwick F, et al. Rapid antigen testing by community health workers for detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e060832. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-060832

27. Roy S, Kennedy S, Hossain S, Warren CE, Sripad P. Examining roles, support, and experiences of community health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in bangladesh: a mixed methods study. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2022) 10:e2100761. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00761

Keywords: transformation, WHO Africa Region, health policy, lessons, just and sustainable, health systems

Citation: Taderera BH (2025) Transformation of the WHO Africa Region Secretariat: an exploratory study of the health policy lessons from health governance strengthening interventions for just and sustainable health systems. Front. Public Health 13:1616655. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1616655

Received: 23 April 2025; Accepted: 20 June 2025;

Published: 24 July 2025.

Edited by:

Olushayo Oluseun Olu, World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa, Republic of CongoReviewed by:

Mselenge Hamaton Mdegela, University of Greenwich, United KingdomHasanain A. J. Gharban, Wasit University, Iraq

Copyright © 2025 Taderera. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bernard Hope Taderera, YnRhZGVyZXJhQHVqLmFjLnph

Bernard Hope Taderera

Bernard Hope Taderera