- 1Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health, Virginia Tech, Roanoke, VA, United States

- 2Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise, Blacksburg, VA, United States

Introduction: Community health educators (CHE) translate empirical health evidence into actionable information to improve the health and wellbeing of communities, including underserved populations. However, the wellbeing of CHE themselves is threatened by chronic work-related stress. One understudied CHE cohort are employees of the federal Cooperative Extension System (herein: Cooperative Extension). The objective of this present study was to co-create a wellness intervention that is feasible and acceptable to CHE of Cooperative Extension.

Methods: Applying a co-creation method, we first gathered formative data from an ongoing integrated research-practice partnership (IRPP) with CHE of Cooperative Extension to guide adaptations on intervention content, dose, and delivery. IRPP members shared key intervention considerations which informed a sequential exploratory mixed-methods approach. To garner contextual considerations and phenomena, we conducted four focus group sessions with CHE from nine different states (N=21, n=4 to 6 per session). We built a follow up survey based on qualitative findings to inform intervention delivery.

Results: Members of the IRPP preferred holistic wellbeing, i.e., flourishing, as a comprehensive target for a CHE wellness intervention. Eighty-one percent (n=17) of focus group participants (90% Female, 62% White) completed the follow up survey. Focus group findings demonstrated a desire for a multi-component intervention (e.g., education, accessible group yoga practices) to address the multiple domains of flourishing and provided guidance on imagery and messaging of recruitment materials. Notably, participants emphasized scheduling as the greatest barrier to overcome. One participant shared that “I think there are probably solutions for this, but it may take a lot of patience while figuring it out.” Survey data elucidated intervention delivery preferences including timing for the intervention (47% preferring a Jan-Mar launch), time of day (early morning ranked highest); facilitator (52% yoga teachers, 24% peer CHE, 0% administrators); as well as the order of content delivery in intervention sessions.

Discussion: Data from co-creation methods with CHE captured often overlooked nuance important for implementation, particularly tailoring the timing of intervention delivery. Beginning with the end in mind and taking careful consideration of contextual factors may improve feasibility and acceptability of intervention characteristics and ultimately increase reach, representativeness, and efficacy.

Introduction

Lay health educators, agents, promotoras, and community health workers of the United States, have the passion and skills to deliver public health interventions as trusted individuals in their communities (1–3). In fact, prior to administrative funding changes in 2025, the National Institute of Health funded over 2,000 projects related to community health workers and educators in 2024 alone (4). However, these community health educators (CHE), especially those from or working with historically underserved communities, represent a target population themselves. CHE face chronic work-related stress and burnout from their people-oriented and emotionally charged work (5). The personal and professional health of CHE must be attended to, or they will not be able to effectively translate empirical health evidence into actionable information to address the most disparate health threats (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and health inequity) (6–9), especially in underserved communities (10–12).

According to extant literature, workplace wellness interventions continue to demonstrate small (13) to modest (14) effects in terms of mental health, sedentary behavior, weight management, and self-reported well-being. The lack of large, robust impacts is, in part, due to heterogeneity in modality (e.g., digital versus in person), varied theoretical underpinnings, and which core elements of the intervention are included [e.g., behavior change techniques (15)]. That is, there is no one-size-fits-all workplace wellness promotion intervention—especially not when considering the variety of workplace types and demands. In the case of CHE, they, too, are not a monolith. However, because CHE often work in dispersed, nontraditional workplaces, there is a general need for accessible, adaptable, and equitable practices that can be implemented in a variety of settings and activities—such as programs offered synchronously or in a self-paced format (16). Virtual interventions are particularly promising for improving CHE health and wellbeing (17). Specifically, meta-analyses of virtual workplace wellness interventions tout improvements in psychological well-being and work effectiveness (18). While virtual worksite wellness interventions have predominantly focused on work productivity, psychological (e.g., anxiety, stress, burnout) and anthropometric (e.g., weight, blood pressure) measures (18, 19), holistic measures that align intervention outcomes with outputs that participants value most (20) may improve intervention uptake.

For millennia, scholars such as Aristotle have been promoting holistic wellbeing or “flourishing” (21). More recently, psychology and positive health researchers have advocated for a shift toward promotion of wellbeing instead of prevention of disease (22–25). Interestingly, a recent randomized controlled trial (26) demonstrated large effects on self-reported outcomes and preliminary data to support compliance with more objective measures (i.e., saliva) in a “happiness intervention” group (i.e., a 7 week intervention focused on promoting joy across various domains of community, work, pleasure, bliss). Essentially, this positive psychology approach to workplace wellness is on the rise (26) and may have more robust outcomes, even in a short protocol period. Flourishing has emerged as a psychometrically validated holistic wellbeing measure across cultures and worksites (20, 27, 28), encompassing outputs such as whether a person is happy, has fulfilling relationships, and feels that they are a “good” person. The promotion of flourishing aligns with the philosophy, art, practice, and science of yoga (29–32). Yoga is a biopsychosocial-spiritual system that originated from India based in ancient and modern yoga principles including mental, physical, and breath practices (33–36). Yoga principles for public health have positively impacted myriad populations and outcomes and align with scientific rigor across fields including physiology, psychology, and neuroscience (37–40).

In alignment with scientific evidence on yoga, CHE of one state system in Cooperative Extension perceived personal yoga practices as beneficial for improved relaxation, overall wellness, mental health, physical health, and self-care (41). In this prior survey-based participatory work, CHE also expressed interest in yoga practices not only for themselves but also for the communities they serve. Additionally, prior phases of a 9-week virtual wellbeing program for CHE of Virginia Cooperative Extension demonstrated improved CHE flourishing and promising feasibility and acceptability of group yoga-based programs in CHE settings (42, 43). However, these prior phases had high scheduling burden on participants. In other words, while previous wellbeing program core functions (i.e., the key ingredients or purposes of the intervention) are promising, the program forms (i.e., the strategies to bring about core functions) are suboptimal (44–46). Therefore, a gap persists in the implementation of an employee wellness intervention for CHE of Cooperative Extension. Using co-creation and mixed methods with participatory community implementation strategies (47, 48) at the pre-implementation phase to adapt existing core functions of a wellness program for CHE has potential to enrich the translation of yoga principles. The aim of this work is not only so that CHE flourish, but that, through their lived experiences, they and the people they serve live long, healthy, and purpose-filled lives (49, 50). Thus, the primary objective of this pre-implementation study was to co-create a tailored wellness intervention that is feasible and acceptable to CHE of the federal Cooperative Extension System.

Materials and methods

Research design overview

An existing and ongoing integrated research-practice partnership (IRPP) (51, 52) with CHE of one particular state system of Cooperative Extension served in an advisory capacity to co-create program content, dose, and delivery. IRPP members are from across each district of the state (100% female, average age 44, age range 25–65 year; 50% with 8 + years working in Cooperative Extension). This included, but was not limited to, language suggestions (e.g., do not describe program as “self-care”) as well as potential scheduling of the program. When asked about workplace wellness interventions, IRPP members expressed the potential ease of adapting previous wellbeing programs for CHE (41–43). Members of the IRPP did not want a program that focused only on one health behavior or one component of overall health (e.g., only relaxation practice or only education on physical activity practices). Instead, members of the IRPP preferred holistic wellbeing, i.e., flourishing, as a comprehensive target for a CHE wellness intervention and expressed interest in multiple yoga principles (movement, breath, and mindfulness) for both personal practice and community translation. This IRPP advisory discussion informed our exploratory mixed-methods (i.e., qualitative followed by quantitative) approach of inviting CHE from a national sample to participate in a focus group and then a follow-up survey. The IRPP members, focus group participants, and follow-up survey participants completed research activities and were not provided additional compensation. This study was IRB exempt as it was considered quality assessment.

Intervention description

The Flourishing in Extension (FLEX) program is a virtual 9-week work-based wellness program with weekly asynchronous emailed newsletters and weekly synchronous 60-min sessions. FLEX is comprised of adapted core functions from prior phases (42, 43) that include journal reflections (53–55), behavior change techniques (e.g., group-dynamics, social support, goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback, and education) (15, 56), experiential learning (57), and yoga principles of meditation and moment-to-moment awareness (dhyana and smrti/sati), breathwork (pranayama), and postures (asana) (29, 35) (See Supplementary file 1 for initial week-by-week guide). The intervention is designed to target flourishing in CHE and to also provide skills in translating intervention components for downstream flourishing of CHE workplaces and communities (42, 43, 58).

Focus groups

After initial design and adaptations of the FLEX program, we invited a purposive sample of CHE of different state Cooperative Extension Systems. State specialists distributed emails to CHE with information for pre-scheduled focus groups using a Qualtrics sign up form (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, May 2024). Aside from questions on sample characteristics, the sign-up form included validated metrics on flourishing (27) and burnout (59). Focus groups were facilitated by a female doctoral candidate and graduate research assistant (MCF) who was trained in qualitative data collection. The facilitator created brief participant engagement-related field notes after each focus group session. No previous partnership or research collaboration existed with invited CHE except for those who might have been previously trained to deliver a community-based program in Virginia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina. Focus group participants were aware that the facilitator (MCF) was working to adapt the FLEX intervention based on their input. No specific characteristics of the facilitator were reported to participants. Focus groups were 60 minutes in duration, conducted and audio-recorded on Zoom, consisted of only the facilitator and focus group participants, and included prompts on wellbeing, flourishing, yoga principles, as well as ‘think-aloud’ sessions on samples of recruitment and program materials (60, 61). Prompts were not previously pilot tested, and no focus group session was repeated. We used Zoom software to auto-generate the focus group transcripts. Two researchers (MCF and MJP) reviewed and edited focus group transcripts to match audio files. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. Although we did not seek data saturation a priori as part of this pre-implementation study, our sample size and data saturation are consistent with prior findings (62, 63). Opt-in consent was presented and obtained at the start of the sign up form and verbal consent was obtained at the start of each focus group. We used the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist for focus group reporting (64).

Follow-up survey

Focus group input informed a follow up survey for gathering clarifying information to guide adaptations of intervention delivery and materials. We emailed the CHE who participated in the focus groups with a Qualtrics follow-up survey link. The follow-up survey included questions on program delivery (time of year, day of the week, national scheduling, start time, and program facilitator), program materials (weekly session order-of-events, colors), interest in pilot program, and preference on pilot start date. Survey participants also had an open-ended option to leave comments at the end of the survey. Participants completed surveys with median time of 6 min. Opt-in consent was presented and obtained at the start of the follow-up survey.

Data analysis

We analyzed quantitative data for descriptive purposes only. For the follow-up survey, we calculated ranking scores by weighing each ranking level for each survey item option. For the qualitative data, we used an inductive approach and thematic analysis (65). Two researchers, both of whom have previously worked with Cooperative Extension CHE, were familiar with flourishing theoretical underpinnings (26, 28), and are registered yoga teachers (MCF and MJP), used Excel Microsoft to independently code the qualitative data from the focus groups before meeting to resolve discrepancies. A third reviewer with similar experience, familiarity, and yoga training (SMH) provided final resolution on unresolved discrepancies as needed. We determined major emergent themes, subthemes, and categories by quantitatively examining the data by number of focus groups and MU for each code using Microsoft Excel. Ultimately, this led to the following thresholds for major emergent codes: (1) spanned three or more of the focus groups (≥75% of focus groups), or (2) included five or more meaning units (MU) in at least two focus groups (≥5 MU and ≥50%). Focus group participants did not provide additional feedback after qualitative analysis.

Cocreated intervention updates

We co-created intervention updates by integrating focus group “think aloud” input and follow up survey data to guide decision-making for intervention materials and factors. For the focus group input, two independent researchers (MJP and MCF) wrote notes on their reflections on CHE focus group data related to the recruitment materials in Microsoft Excel. Researchers met to discuss notes and grouped data into actionable updates to materials. The two researchers, who each have yoga teacher training and experience in yoga principles for public health and health equity, independently created mock-up recruitment materials that met all focus group input on recruitment materials. Mockups and notated data were presented to the primary investigator (SMH) before a qualitative data-informed decision was collectively reached.

Results

Sample characteristics

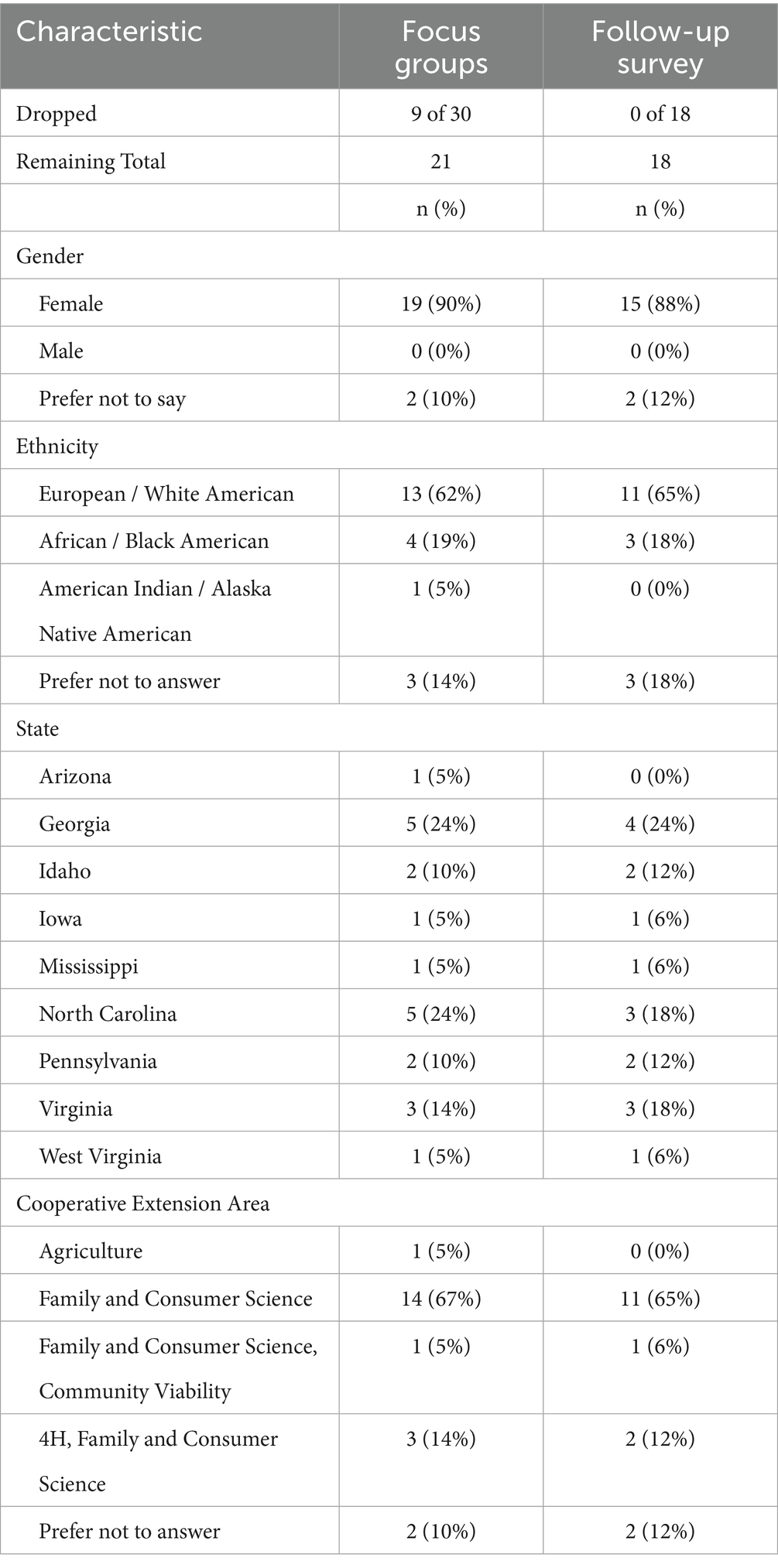

Of the 222 CHE whom we emailed the focus group sign-up form, 30 emails bounced, and 30 CHE signed up to participate in the four focus group sessions (16%). Four participants later declined (3 had scheduling conflicts, 1 unspecified). Of the remaining 26, 21 CHE participated in the focus group sessions (81% of initial interested, 4 to 6 CHE per session, 76% with no previous research collaboration, see Table 1 for full sample characteristics). Of the 21 CHE whom we emailed, 17 CHE completed the follow-up survey (81% of focus group participants). Focus group participants had an average burnout score of 4.3 of 8 (standard deviation: 1.1, low score indicates no burnout whereas high score indicates complete burnout) and had average flourishing scores of 7.3 of 10 (standard deviation: 1.0, high scores indicate greater flourishing). Follow-up survey participants had an average burnout score of 3.78 (standard deviation: 1.06).

Focus group findings

Transcripts from the focus group sessions resulted in 389 MU total. We present the data in three parts: (1) perspectives on wellbeing, flourishing, yoga principles, and wellbeing program (169 MU subtotal); (2) program materials input (125 MU subtotal); and (3) recruitment materials input (90 MU subtotal). For qualitative analysis, inter-rater reliability between the two coding researchers was 99%.

Perspectives on wellbeing, flourishing, yoga principles, and wellbeing program

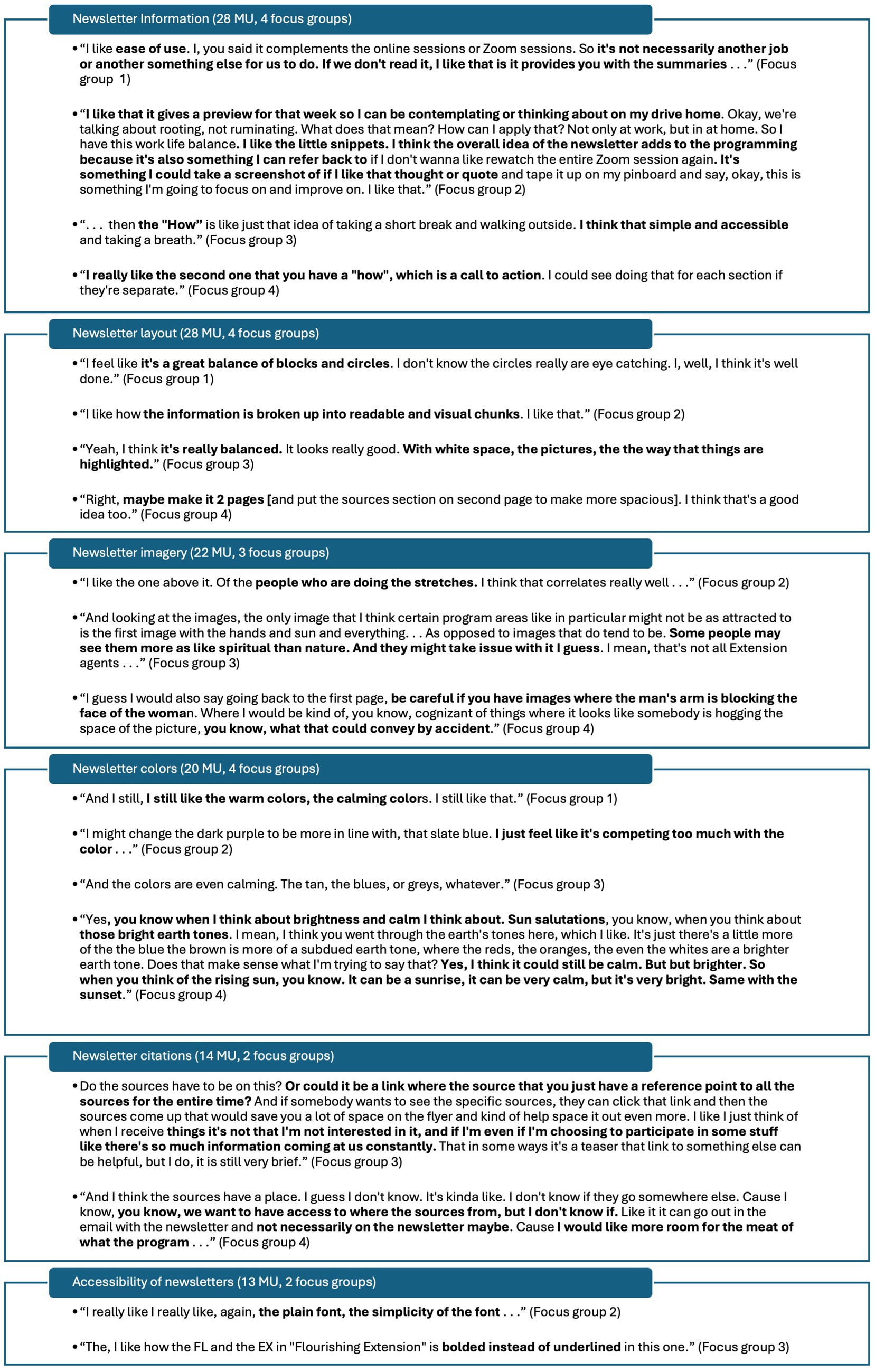

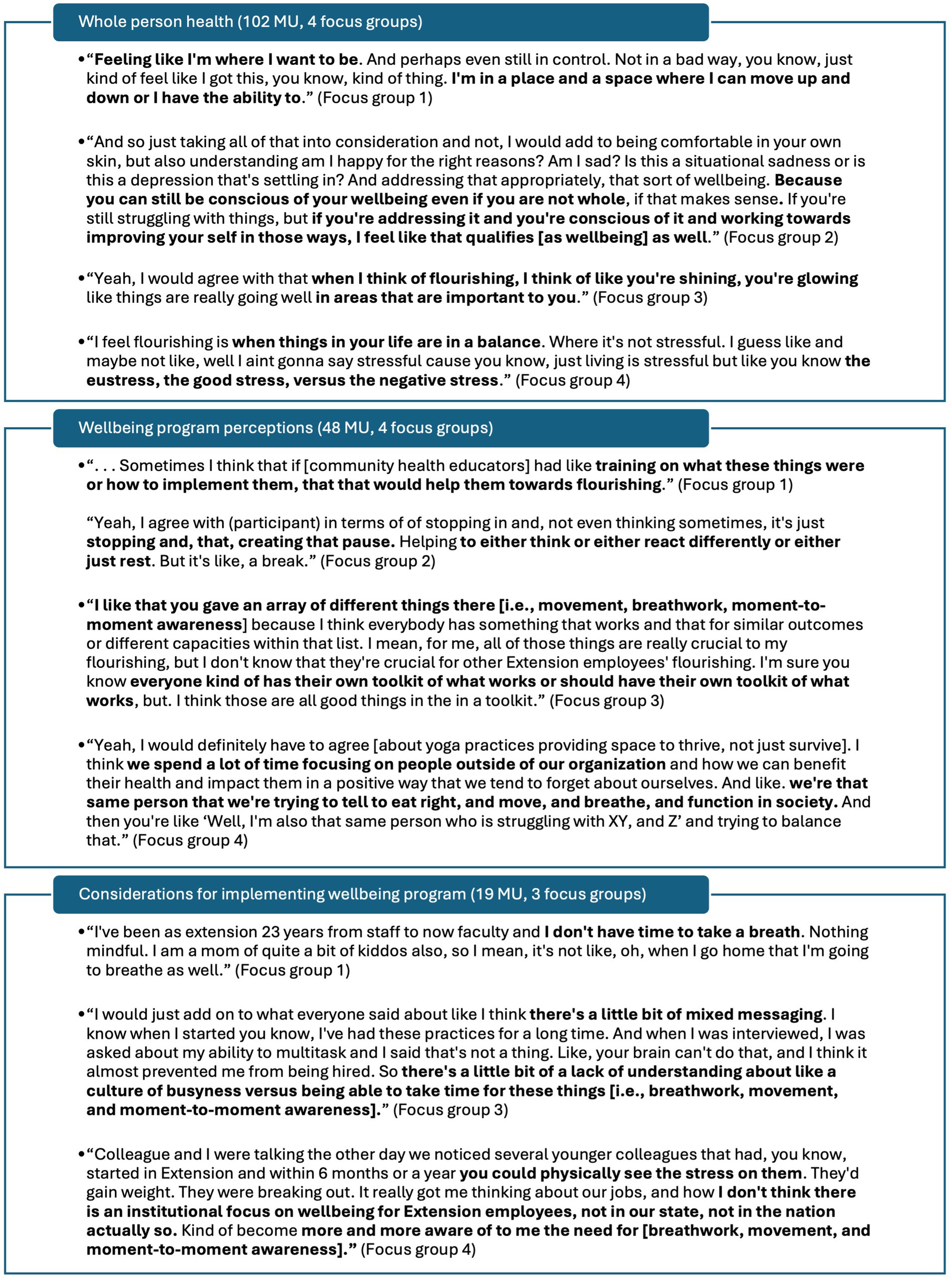

Focus group participants described their perspective in response to prompts on wellbeing, flourishing, and yoga principles, from which three major emergent themes, nine major emergent subthemes, and 13 major categories arose (See Figure 1 for full details). Participants described feelings and multiple dimensions of wellbeing and flourishing as well as perceptions of and considerations for implementing the FLEX program (Figure 2). See Supplementary file 2 for full codebook with all MU.

Figure 1. Major emergent themes, subthemes, and categories of focus group data on perspectives of wellbeing, flourishing, yoga principles, and wellbeing program. MU, meaning units. FLEX, Flourishing in Extension. Number of focus groups indicated by ‘n’/4.

Figure 2. Exemplar meaning units under whole person health, wellbeing program perceptions, and considerations for implementing wellbeing program themes. MU, meaning unit.

No minor subthemes emerged under the theme whole person health. Under subtheme dimensions of wellbeing, four minor categories emerged including social wellbeing (2 MU, 2 focus groups), nutritional wellbeing (2 MU, 2 focus groups), taking care of oneself (1 MU, 1 focus group), and enjoying hobbies (1 MU, 1 focus group). Under subtheme feelings of flourishing, 10 minor categories emerged including feeling energy or ease in daily life (2 MU, 2 focus groups), feeling completely balanced (2 MU, 1 focus group), feelings of overcoming difficulties in life (2 MU, 1 focus group), and other categories such as feeling creative, feeling mentally spacious, feeling that there is time for family, feeling well from nourishing foods, feelings of productivity or functioning, still flourishing even if working on bettering different areas of flourishing, and reciprocally radiating complete balance in to others (each 1 MU). Under subtheme holistic wellbeing, two minor categories emerged including Flourishing Index domains as a model for flourishing (4 MU, 2 focus groups) and ways of being (3 MU, 2 focus groups). Under subtheme feelings of wellbeing, four minor categories emerged including feeling healthy (2 MU, 2 focus groups), feeling comfortable with oneself (2 MU, 1 focus group), feeling happy (1 MU), and feeling energy and vitality (1 MU). Under subtheme key domain of flourishing, four while minor categories emerged including financial and material stability (3 MU, 2 focus groups), close social relationships (3 MU, 2 focus groups), happiness and life satisfaction (2 MU, 2 focus groups), and mental and physical health (2 MU, 2 focus groups).

No minor subthemes emerged under the theme wellbeing program perceptions. Under perceptions about yoga principles, five minor categories emerged including pausing or breathwork perceived as important (4 MU, 2 focus groups), yoga principles as part of toolkit toward mutual flourishing or Extension programming for diverse contexts (4 MU, 1 focus group), movement important for feeling well (3 MU, 2 focus groups), yoga practices perceived as beneficial for home setting, not just work setting (2 MU, 2 focus groups), and yoga practice perceived as accessible (1 MU). Remaining major emergent subthemes only included minor emergent categories. Under subtheme suggestions for FLEX program, minor emergent categories included reminders to do yoga practices/integration of yoga practices into work schedule (4 MU, 1 focus group), inclusion of play or prizes into programming (2 MU, 2 focus groups), inclusion of specific strategies for integrating FLEX practices (2 MU, 2 focus groups), and other categories such as inclusion of setting boundaries, hybrid asynchronous lectures with synchronous activity, inclusion of short, accessible videos, and partnering with community resources (each 1 MU). Under subtheme FLEX program is desirable, minor emergent categories included need for employee wellness program (3 MU, 2 focus groups) and desire to receive training to support implementation of personal flourishing practices (3 MU, 1 focus group).

Under considerations for implementing wellbeing program, three minor subthemes emerged including interpersonal barriers to participating in yoga or wellbeing practices (4 MU, 2 focus groups), individual barriers to participating in yoga or wellbeing practices (2 MU, 2 focus groups), and system-level support for participating in yoga practices (2 MU, 1 focus group). Under major emergent subtheme system barriers to participating in yoga or wellbeing practices, two minor categories emerged including safe and accessible spaces in which to practice movement (2 MU, 2 focus groups) and yoga practices are poorly understood (1 MU). Minor emergent categories under subtheme interpersonal barriers to participating in yoga or wellbeing practices include perception of generational influence on work culture (3 MU, 2 focus groups) and false perception that agents have it altogether or are already balanced (1 MU). One minor category emerged under subtheme individual barriers to participating in yoga or wellbeing practices as resistant views to pausing or taking a break for self-care (2 MU, 2 focus groups). One minor category also emerged under subtheme system-level support for participating in yoga or wellbeing practices as office culture of taking breaks for movement (2 MU, 1 focus group).

Program materials input

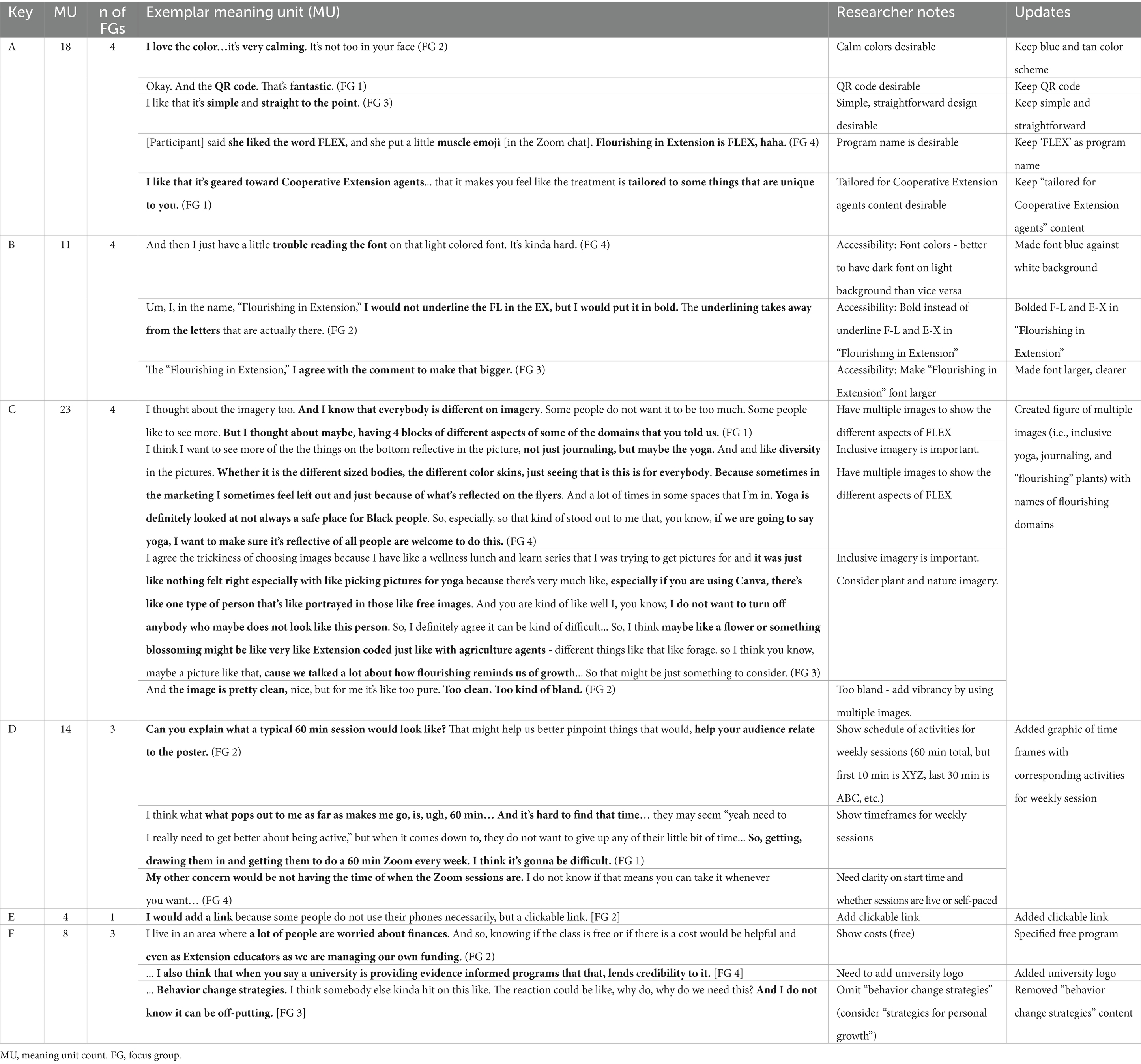

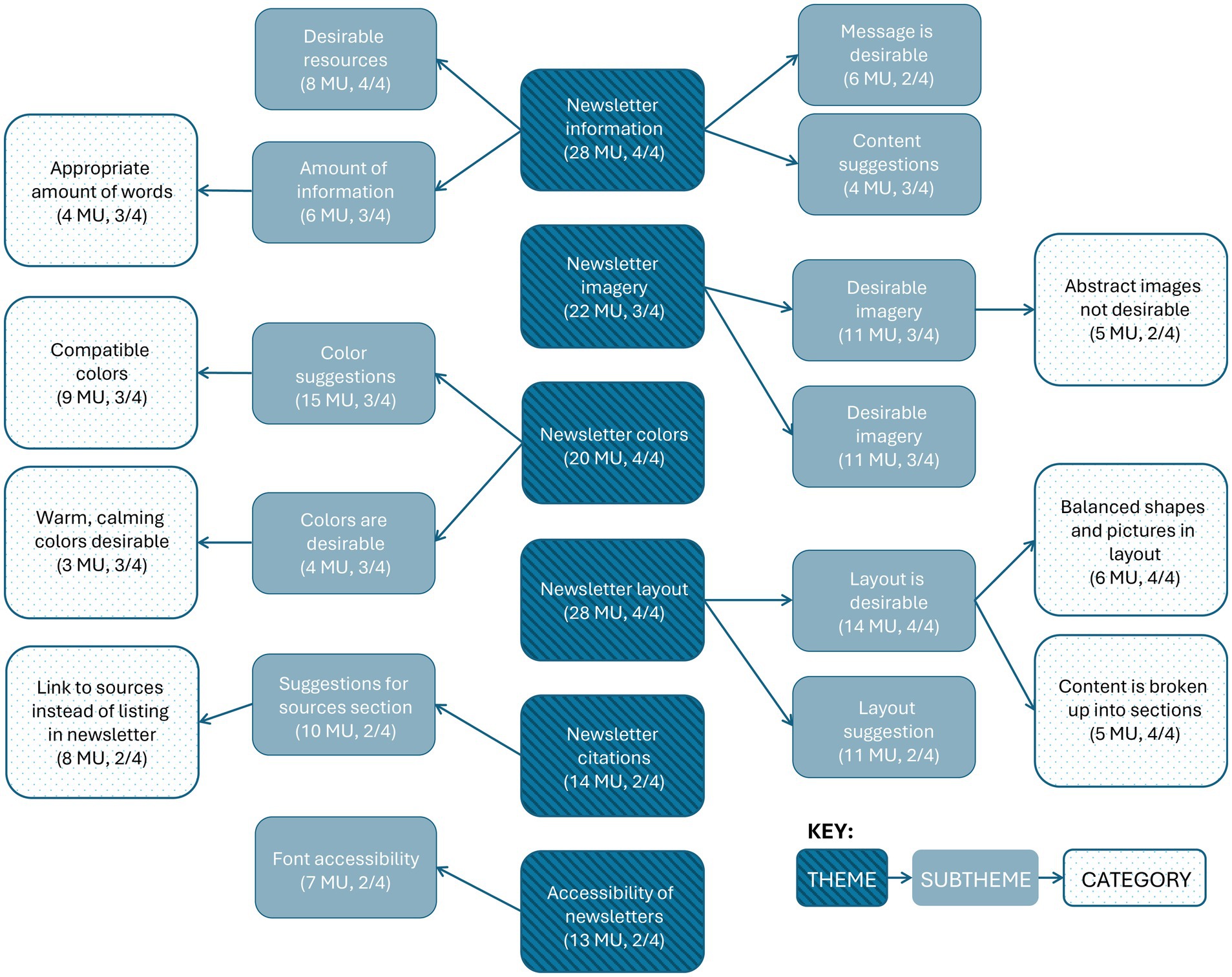

During the think alouds for the program materials (i.e., weekly newsletters), focus group participants provided input for future updates, from which six major emergent themes, 12 major emergent subthemes, and seven major categories arose (See Figure 3 for full details). Participants generally noted appreciation for newsletter information, layout, and colors while also providing suggestions for newsletter imagery, citations, and accessibility (Figure 4). See Supplementary file 2 for full codebook with all MU.

Figure 3. Major emergent themes, subthemes, and categories related to input on program materials. MU, meaning units.

Under the theme newsletter information, one minor subtheme emerged as Cooperative Extension content (4 MU, 2 focus groups). Under major subtheme amount of information, one minor category emerged as too many words (2 MU, 2 focus groups). Under major subtheme desirable resources, minor emergent categories included information on simple, accessible practices is desirable (4 MU, 2 focus groups), link or QR code to more resources is desirable (2 MU, 2 focus groups), and newsletters as not an addition but a takeaway to complement weekly sessions are desirable (2 MU, 2 focus groups). Under major emergent subtheme message is desirable, minor emergent categories include flourishing themes and yoga concepts in general (3 MU, 1 focus group), “rooting, not ruminating” (2 MU, 2 focus groups), and “subtle anatomy” (1 MU). Under subtheme content suggestions, minor emergent categories include removal of yoga chakras content (2 MU, 1 focus group), inclusion of weekly session reminder (1 MU), and clarity that newsletter is an educational resource (1 MU). Under subtheme Cooperative Extension content, minor emergent categories include Virginia Cooperative Extension no-discrimination statement comments (3 MU, 2 focus groups) and logos perceived as important (1 MU).

Under major theme newsletter layout, one minor subtheme emerged as font layout (3 MU, 2 focus groups). Under major emergent subtheme layout is desirable, minor emergent categories include one page is desirable (2 MU, 1 focus group) and layout is generally desirable (1 MU). Under major emergent subtheme layout suggestions, two minor categories emerged as make circular images the same size (2 MU, 1 focus group) and make space for information to be more spread out (1 MU). Under major emergent subtheme font layout, minor emergent categories included justify and format font to create uniform paragraph blocks, curve font headings around images, make bolding of in-text key words consistent (each 1 MU).

No minor subthemes emerged under major theme newsletter imagery. Only minor categories emerged under major emergent subtheme desirable imagery, including imagery of people doing yoga is desirable (4 MU, 2 focus groups), nature imagery is desirable (3 MU, 2 focus groups), inclusive is imagery desirable (2 MU, 1 focus group), imagery of people in groups is desirable (1 MU), and specific image of hands with sun (1 MU). Under major emergent subtheme undesirable imagery, minor emergent categories included specific imagery of hands with sun not desirable (2 MU, 2 focus groups), specific imagery of feet not desirable (2 MU, 2 focus groups), cartoon graphics not desirable (1 MU), and fewer images as an option (1 MU). No minor subthemes emerged under major theme newsletter colors. Under major emergent subtheme color suggestions, one minor category emerged as brighter colors more desirable (6 MU, 1 focus group). Under major emergent subtheme colors are desirable, one minor category emerged as colors are generally desirable (1 MU).

Under major emergent theme newsletter citations, two minor subthemes emerged as in-text citations suggestions (3 MU, 2 focus groups) and Cooperative Extensions as audience (1 MU). Under major emergent subtheme suggestions for sources section, one minor category emerged as link a list of sources all in one place for all newsletters each week (2 MU, 2 focus groups). Under subtheme minor emergent subtheme in-text citations suggestions, two minor categories emerged as use superscript instead of parentheses (2 MU, 1 focus group) and do not bold in-text citations (1 MU). The one minor emergent category under minor emergent subtheme Cooperative Extension as audience is scholarly, research-based information okay for agents as audience (1 MU). Additionally, under major emergent theme accessibility of newsletters, two minor subthemes emerged as considerations for emailing newsletters (3 MU, 2 focus groups) and colors contrast (2 MU, 1 focus group). Under major emergent subtheme font accessibility, minor emergent categories include bold instead of underline FL EX in Flourishing in Extension (3 MU, 2 focus groups), accessible font with font hierarchy is desirable (3 MU, 1 focus group), and justify font left instead of center (1 MU). Under minor emergent subtheme considerations for emailing newsletters, minor emergent categories include too many images will make pdfs too large for some computers, emails will block images in email body and add link in addition to QR code (each 1 MU). Under colors contrast, one minor category emerged as use blues instead of brown (1 MU).

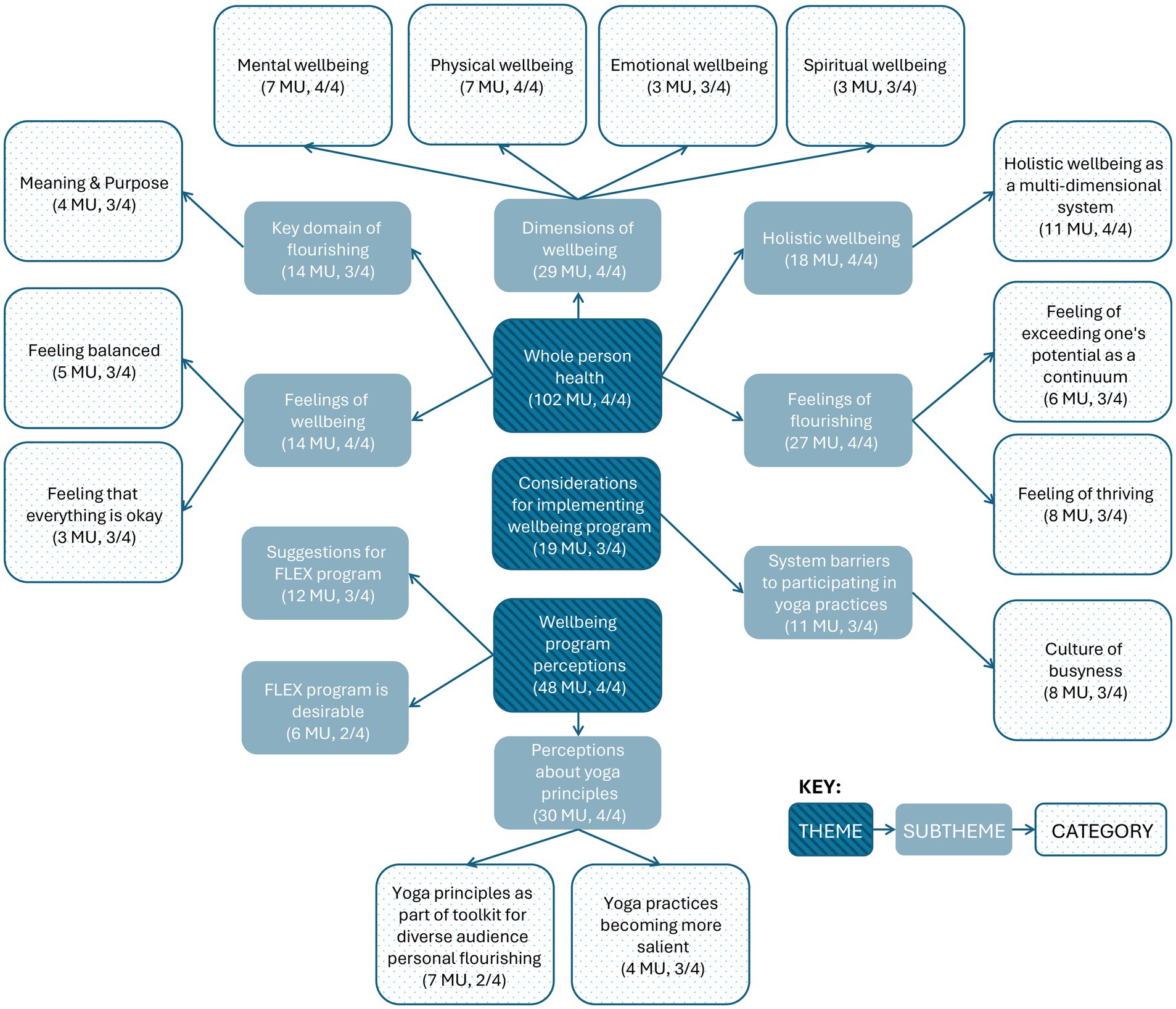

Recruitment materials input and adaptations

During the think alouds for the recruitment flyer, focus group participants provided input for future updates (Figure 5; Table 2). Input included (A) desirable flyer aspects including calm colors, QR code, simple and straightforward design, program name, and accessible font (18 MU, 4 focus groups); (B) suggestions to improve font accessibility including using dark font on a light background, bolding instead of underlining, and making the text larger and more clear (11 MU, 4 focus groups); (C) suggestions to make the central figure more reflective of the FLEX program by including multiple images to show the different aspects of FLEX such as yoga, breath, journaling, flourishing domains, etc., as well as make imagery inclusive with different sized bodies and different skin colors (23 MU, 4 focus groups); (D) suggestions to add information about “drop in” time frames for weekly session activities (14 MU, 3 focus groups); (E) suggestions on providing clarity such as specifying that the program is free, which university the program is from, and that sessions are via Zoom (8 MU, 3 focus groups); and (F) suggestions to use a short link in addition to the QR code (5 MU, 2 focus groups).

Figure 5. Comparison of intervention newsletter before and after data-driven adaptations. (A) Kept desirable components (e.g., kept QR code); (B) improved font accessibility (e.g., dark font against light background); (C) created figure to illustrate program components and desired imagery (e.g., included multiple, inclusive images of yoga practices and journaling); (D) added graphic of time frames with corresponding activities for weekly session; (E) added clickable link; (F) changed language and added university logo to provide better clarity and credibility.

Follow-up survey findings

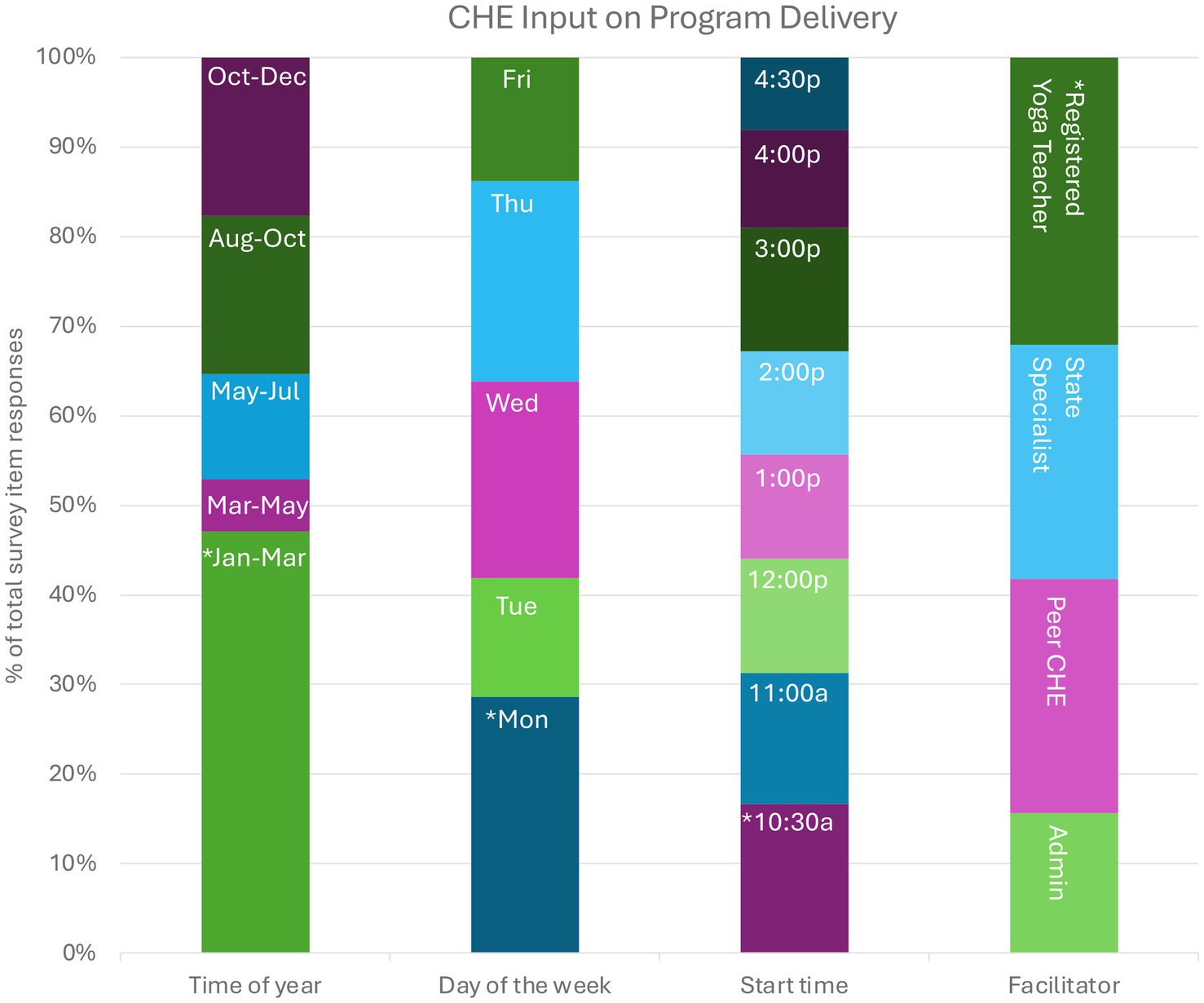

Participants who completed the follow-up survey represented four time zones: 1 in Pacific Time (6%), 2 in Mountain Time (12%), 3 in Central Time (18%), and 11 in Eastern Time (65%). For intervention delivery, CHE overall preferred program weekly session to be during January–March on Monday mornings and facilitated by a registered yoga teacher (Figure 6). In response to the program facilitator prompt, two participants selected the “other” open-ended option, writing that a facilitator could be “anyone certified in workplace wellness, yoga, stress management, etc.” and that it “depends on their level of personal practice and experience.”

Figure 6. Follow-up survey findings based on input for program delivery factors. *Asterisk indicates greatest proportion of participant selection. Months and weekdays are abbreviated using the first three letters of names. Start times were controlled for different time zones and are represented here using Eastern Time. CHE, community health educators. ‘p’ indicates PM. ‘a’ indicates AM.

In response to prompts on program materials, participants ranked color palettes and options for weekly sessions order-of-events according to preference. In one focus group, a participant used the chat feature to upload a photo that demonstrated their preferred hues and colors. Color palettes based on this photo were then created and shared for direct feedback in the remaining focus groups. Of the color palettes, participants ranked the ‘bright, muted’ highest (Figure 7). Of the options for weekly sessions order-of-events, participants ranked highest the following order-of-events: 10-min journal prompt, 20-min education with discussion, and 35-min guided yoga practice.

Figure 7. Color palette options provided in follow-up survey. *Asterisk indicates greatest proportion of participant selection.

In response to prompts on interest in participating in a pilot program of FLEX, 15 survey participants selected ‘yes’ (88%), one survey participant selected ‘no’, and one survey participant selected the ‘other’ option (6%), noting that: “I am [interested] but I’m not sure if my schedule will allow it.” When those interested were asked whether they preferred to participate in the pilot program in June 2024 versus September 2024, 8 participants selected September (53%) and 4 selected ‘other’ (27%), noting that summer and fall times are busy months and that November–February would be best. Two participants (12%) provided additional information in response to an optional prompt at the end of the survey, with one participant corroborating the previous statements that summer and fall times were busy times. The other participant, stated:

I really like the FLEX idea and would really enjoy participating. I did find over the last number of weeks that there was ALWAYS something that came up that I couldn't avoid. I would imagine that is the case for many agents. I think there are probably solutions for this, but it may take a lot of patience while figuring it out.

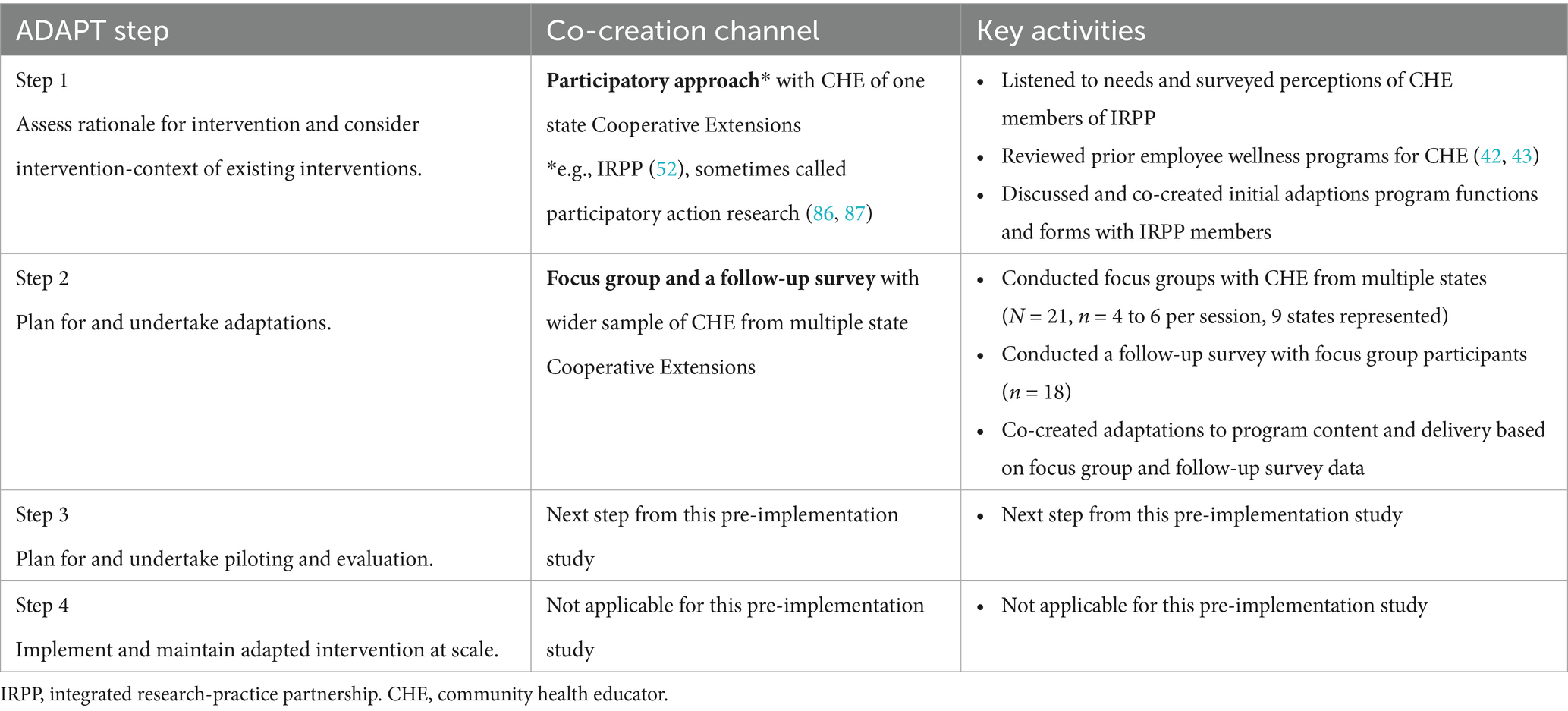

Data-informed program adaptations

Mixed methods data from IRPP members and national CHE focus group sessions with a follow-up survey informed several adaptations (Table 3). First, the national launch of the 9-week pilot FLEX program was rescheduled for January 2025 with weekly sessions on Monday mornings to align with CHE input on scheduling. Additionally, the recruitment flyer was updated based on data from focus group think-alouds (Figure 5). FLEX program materials were also updated based on data from both focus groups and follow-up survey findings (Figure 8).

Table 3. Pre-implementation process for capturing contextual, co-created intervention adaptations, mapped to the ADAPT framework (71, 72).

Discussion

In this sequential mixed-methods pre-implementation study of an employee wellness behavioral intervention for CHE of the federal Cooperative Extension System, we provide three key findings. First, we describe CHE perceptions on wellbeing, flourishing, and yoga principles to inform the future development and implementation of employee wellness intervention core functions. Second, we demonstrate specific input-driven adaptations to preexisting wellness program core functions and forms for Cooperative Extension, resulting in the FLEX program. Lastly, we share insights for the process of contextually tailoring employee wellness interventions for populations at risk for or experiencing burnout such as CHE.

With the exception of previous phases of FLEX (42), prior peer-reviewed research on worksite wellbeing programs for CHE of Cooperative Extension, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, do not exist. However, a systematic review of virtual worksite mental health interventions for knowledge sector employees (i.e., business, communication, education, finance, and information-related research) demonstrated small positive effects for improved psychological wellbeing (e.g., anxiety, depression, and stress) and work effectiveness (i.e., productivity and engagement) (18). Although use of participatory methods and facilitation costs were not analyzed in the reviewed interventions (mean duration 7.6 weeks), over half were reported to be self-paced while the remaining were mostly guided by a therapist or coach (18). Notably, more than half of the interventions used a cognitive behavioral therapy approach which demonstrated small effects for psychological wellbeing compared to the medium effects of psychological approaches of other studies, one of which used positive psychology (e.g., happiness) (66). One reason for these small effects of worksite interventions is that the functions of these intervention may not align with the nuances of what employees need and value most for flourishing in the workplace (26). One systematic review on job flourishing research specifies that more dynamic functions of worksite interventions may serve beyond short-term organizational (e.g., burnout prevention) toward more humanistic goals, such as community embeddedness and health (67). In fact, in our focus group data, CHE of Cooperative Extension described a whole person health of which holistic wellbeing encompasses a multi-dimensional system, including the mental, physical, emotional, spiritual, and social dimensions. CHE descriptions of whole person health and wellbeing align with the biopsychosocial-spiritual model (68) and flourishing index (20, 27). CHE further described key domains of flourishing, particularly meaning and purpose, as well as feelings of flourishing, particularly feelings of thriving and of exceeding one’s potential as a continuum. These data demonstrate target positive responses (i.e., internal affect) for future intervention behavioral change mechanisms (69). Additionally, CHE perceptions of yoga principles were overall positive and demonstrated the desire for yoga principles as a part of a toolkit for diverse audiences to use toward their personal flourishing. As the health behaviors of CHE can influence the health of the people they serve (49, 50), future CHE employee wellness interventions may consider how the provision of core functions based in a biopsychosocial-spiritual wellness approach for CHE would build their confidence and competence to facilitate the same practices toward flourishing for the communities they serve (e.g., offering journal prompts or breathwork in workplaces).

To align with input from triangulated participatory, qualitative, and quantitative findings (47), we made needs-based, data-driven adaptations to the core functions and forms of the FLEX program, particularly regarding the schedule of delivery and program materials. While we initially prepared to deliver the program in the summer or fall of 2024, we adapted our approach based on overwhelming data that the winter months would be best for CHE busy schedules. We instead scheduled delivery of the program for January 2025 after winter holidays based on CHE data. Additionally, we adapted program materials to align with CHE input based on major emergent themes. For example, several participants noted the need to see a timetable or graphic on the recruitment flyer so that it was clear what FLEX weekly sessions entailed to inform CHE decisions on whether to sign up. Two participants from two different focus groups also noted that specifying whether the FLEX program was free provided important clarity for recruitment. For program materials (i.e., emailed newsletters), participants noted sufficient information but suggested using more clearly relevant imagery instead of imagery perceived as abstract or unclear. Additionally, we made adaptations based on minor emergent themes of low effort and possible high impact, such as adding clickable links to recruitment and program materials and making shapes and font consistent. We also incorporated feedback on content and accessibility of program materials. As examples, CHE provided key insights into use of imagery, such as using multiple images to demonstrate inclusivity and provide clarity on the multiple program components, as well as suggested improvements for accessibility, including color contrast and using accessible font. Furthermore, CHE provided valuable insights into implementing a wellbeing program by naming barriers at multiple levels, most notably system barriers to participating in yoga practices. As CHE described a culture of busyness as a barrier to participating in personal flourishing practices, future CHE employee wellness intervention adaptations and development may consider tailoring intervention forms for hierarchal key decision-makers in CHE systems, such as regional administrators of Cooperative Extension Systems. Overall, these co-created adaptations provided rich insights for tailoring the intervention and also served as a reminder of the patience required in facilitating participatory work (47). These findings further corroborate prior work on methods for understanding end-user needs and contextual factors and intervention core functions and forms to ultimately improve intervention-context fit (45, 46).

This process of capturing contextual adaptations can be replicated by others to improve intervention acceptability and sustainability (70–72). Notably, this process can be applied at the pre-implementation phase as well as iteratively after intervention delivery. Crucial to this adaptation and tailoring process is co-creation: the participatory, collaborative, and iterative approach with intervention decision-makers and end-users to design and problem-solve at all levels of intervention research (73, 74). Based on mixed methods for co-creation (75), this study outlines collaborating with participatory partners to adapt existing intervention core components and functions and then using focus groups with user-centered think alouds and a follow-up survey with a wider sample to collect input on program forms (i.e., characteristics, delivery, and materials) to inform adaptations for improved reach and acceptability. This qualitative process may be bolstered by using models to guide pre-implementation data collection including premortem brainwriting (76); the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment model (77, 78); and the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (79, 80). While co-creation is a valuable practice for all stages of intervention development and testing, we found that garnering end-user input at the pre-implementation stage may not only improve fit of program characteristics, delivery, and materials but also reveal crucial nuance to program scheduling and delivery, especially for burnout populations already experiencing high burden and time scarcity (5, 81, 82). Beginning and adapting wellbeing interventions with the end-user in mind (83, 84) is thus integral for contextually competent dissemination and implementation. This approach overall aims for interventions to reach and resonate with those who would benefit from them most, like how one focus group participant shared: “[It] makes you feel like that the program is designed by people that have you in mind.”

Strengths and limitations

One prominent strength of this study is the use of rigorous participatory and mixed methods to co-create an adapted intervention at the pre-implementation context. Another strength of this study is the focus of an understudied employee population with inclusion of community health educators from multiples states. An additional strength of this study is the use of an existing IRPP of over 10 years (51). For investigators that do not have an already established partnership, many methods from engagement research, community based participatory research, and dissemination and implementation science (47, 48) could be applied to begin building partnerships, such as identifying key decision-makers and developing goals and role clarity. Additionally, we took a novel approach to major and minor emergent qualitative analysis by allowing quantitative divides in the data to determine thresholds. This study also contains limitations. First, the study lacks a guiding implementation model or framework for qualitative analysis. Second, while the knowledge of the coding researchers about CHE, flourishing, and yoga may serve as a strength, this positionality may also unconsciously contribute to bias. However, both coding researchers completed training in inductive qualitative analysis and were instructed to stay as close to the source material as possible to mitigate possible bias. Additionally, our findings may not be generalizable to wider populations as our study samples are small and predominantly female and White. However, these sample characteristics may be representative of the CHE population according to other studies (85) although there is a lack of national statistics to verify this. Furthermore, sample recruitment may be subject to potential selection bias. Lastly, our study does not include pilot testing validation of the focus group prompts.

Future directions

Future methods include assessing if adapted materials meet preferences and expectations of participants as well as testing potential reach and acceptability of these materials with prospective participants who did not contribute to this formative work. Future directions of this work also include launching a mixed methods feasibility pilot study of the adapted, co-created FLEX program to test the acceptability of program characteristics and implementation.

Conclusion

This mixed methods pre-implementation study captured often overlooked contextual factors important for intervention feasibility, acceptability, and implementation. We learned that collecting input and feedback from target burnout populations may serve as an important implementation strategy for improving future recruitment and retention. By collecting target population-specific data, especially from underrepresented, burnout, and other hard to reach and retain populations, valuable input can inform co-creation and adaptations of behavioral health intervention characteristics and delivery and ultimately increase accessibility, representativeness, and efficacy.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The Virginia Tech Human Research Protection Program determined study protocol met the criteria for exemption from IRB review under 45 CFR 46.104(d) category(ies) 2(ii). The studies involving humans were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. However, opt-in consent and verbal consent was obtained.

Author contributions

MF: Visualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Software, Conceptualization. SH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Validation, Formal analysis, Software, Funding acquisition, Resources. MP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was partly funded by Virginia Tech Center for Future Work Places and Practices (VT CFWPP 2024 Student Summer Research Award).

Acknowledgments

The authors are incredibly grateful for the insight and support of the members of our integrated research-practice partnership at Virginia Cooperative Extension. We would also like to thank all the community health educators and agents of numerous Cooperative Extension programs for their input and engagement.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1634264/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CHE, community health educators; IRPP, integrated research-practice partnership; FLEX, Flourishing in Extension; COREQ, COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research; MU, meaning unit.

References

1. Ferrer, RL, Schlenker, CG, Cruz, I, Noël, PH, Palmer, RF, Poursani, R, et al. Community health workers as trust builders and healers: a cohort study in primary care. Ann Fam Med. (2022) 20:438–45. doi: 10.1370/afm.2848

2. Sommers, IJ, Gunter, KE, McGrath, KJ, Wilkinson, CM, Kuther, SM, Peek, ME, et al. Trust dynamics of community health workers in frontier food banks and pantries: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. (2023) 38:18–24. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07921-7

3. Miller, NP, Ardestani, FB, Dini, HS, Shafique, F, and Zunong, N. Community health workers in humanitarian settings: scoping review. J Glob Health. (2020) 10:020602. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020602

4. NIH. RePORTER > “community health worker”. Available online at: https://reporter.nih.gov/search/xqhjoELw502vR1SSOQ6sDQ/projects/charts?fy=2024 (Accessed April 03, 2025).

5. Russell, M, Attoh, P, Chase, T, Gong, T, Kim, J, and Liggans, G. Burnout and extension educators: where we are and implications for future research. J Hum Sci Ext. (2019) 7, 195–211.

6. Jeet, G, Thakur, JS, Prinja, S, and Singh, M. Community health workers for non-communicable diseases prevention and control in developing countries: evidence and implications. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0180640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180640

7. Brook, RD, Levy, PD, Brook, AJ, and Opara, IN. Community health workers as key allies in the global Battle against hypertension: current roles and future possibilities. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2023) 16:e009900. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.123.009900

8. Zare, H, Delgado, P, Spencer, M, Thorpe, RJ, Thomas, L, Gaskin, DJ, et al. Using community health workers to address barriers to participation and retention in diabetes prevention program: a concept paper. J Prim Care Community Health. (2022) 13:21501319221134563. doi: 10.1177/21501319221134563

9. Valeriani, G, Sarajlic Vukovic, I, Bersani, FS, Sadeghzadeh Diman, A, Ghorbani, A, and Mollica, R. Tackling ethnic health disparities through community health worker programs: a scoping review on their utilization during the COVID-19 outbreak. Popul Health Manag. (2022) 25:517–26. doi: 10.1089/pop.2021.0364

10. Buys, DR, and Rennekamp, R. Cooperative extension as a force for healthy, rural communities: historical perspectives and future directions. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:1300–3. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305767

11. Meendering, JR, McCormack, L, Moore, L, and Stluka, S. Facilitating nutrition and physical activity-focused policy, systems, and environmental change in rural areas: a methodological approach using community wellness coalitions and cooperative extension. Health Promot Pract. (2023) 24:68S–79S. doi: 10.1177/15248399221144976

12. Strayer, TE, Balis, LE, and Harden, SM. Partnering for successful dissemination: how to improve public health with the National Cooperative Extension System. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2020) 26:184–6. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001025

13. Shiri, R, Nikunlaakso, R, and Laitinen, J. Effectiveness of workplace interventions to improve health and well-being of health and social service workers: a narrative review of randomised controlled trials. Healthcare (Basel). (2023) 11:1792. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11121792

14. Peñalvo, JL, Sagastume, D, Mertens, E, Uzhova, I, Smith, J, Wu, JHY, et al. Effectiveness of workplace wellness programmes for dietary habits, overweight, and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2021) 6:e648–60. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00140-7

15. Abraham, C, and Michie, S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. (2008) 27:379–87. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379

16. Harden, S, Balis, L, Strayer, T, Prosch, N, Carlson, B, Lindsay, A, et al. Strengths, challenges, and opportunities for physical activity promotion in the century-old National Cooperative Extension System. J Hum Sci Extens. (2020) 8, 104–124.

17. Howarth, A, Quesada, J, Silva, J, Judycki, S, and Mills, PR. The impact of digital health interventions on health-related outcomes in the workplace: a systematic review. Digit Health. (2018) 4:2055207618770861. doi: 10.1177/2055207618770861

18. Carolan, S, Harris, PR, and Cavanagh, K. Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: systematic review and Meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e271. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7583

19. Hilton, LG, Marshall, NJ, Motala, A, Taylor, SL, Miake-Lye, IM, Baxi, S, et al. Mindfulness meditation for workplace wellness: an evidence map. Work. (2019) 63:205–18. doi: 10.3233/WOR-192922

20. Vander Weele, TJ, McNeely, E, and Koh, HK. Reimagining health—flourishing. JAMA. (2019) 321:1667–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3035

21. Sauvé Meyer, S. How to flourish: an ancient guide to living well. Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (2023). 328 p.

22. Weziak-Bialowolska, D, Bialowolski, P, Vander Weele, TJ, and McNeely, E. Character strengths involving an orientation to promote good can help your health and well-being. Evidence from two longitudinal studies. Am J Health Promot. (2021) 35:388–98. doi: 10.1177/0890117120964083

23. Seligman, M, Peterson, C, Barsky, A, Boehm, J, Kubzansky, L, Park, N, et al. Positive health and health assets: re-analysis of longitudinal datasets. Psychol Faculty Articles Res. (2013)

24. Seligman, MEP, Steen, TA, Park, N, and Peterson, C. Positive psychology Progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol. (2005) 60:410–21. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

25. VanderWeele, TJ, Chen, Y, Long, K, Kim, ES, Trudel-Fitzgerald, C, and Kubzansky, LD. Positive epidemiology? Epidemiology. (2020) 31:189–93. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001147

26. Verma, R, Sekar, S, and Mukhopadhyay, S. Unlocking flourishing at workplace: an integrative review and framework. Appl Psychol. (2025) 74:e12591. doi: 10.1111/apps.12591

27. Weziak-Bialowolska, D, McNeely, E, and VanderWeele, TJ. Flourish index and secure flourish index–validation in workplace settings. Cogent Psychol. (2019) 6:1598926. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2019.1598926

28. Weziak-Bialowolska, D, Bialowolski, P, Lee, MT, Chen, Y, VanderWeele, TJ, and McNeely, E. Psychometric properties of flourishing scales from a comprehensive well-being assessment. Front Psychol. (2021) 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.652209

29. Hartfiel, N, Havenhand, J, Khalsa, SB, Clarke, G, and Krayer, A. The effectiveness of yoga for the improvement of well-being and resilience to stress in the workplace. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2011) 37:70–6. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2916

30. Broad, WJ. The science of yoga: The risks and the rewards. Riverside, NJ: Simon & Schuster (2012). 352 p.

31. Cochrane Library Special Collection: Yoga for improving health and well-being. (2018). Available online at: https://www.cochrane.org/news/cochrane-library-special-collection-yoga-improving-health-and-well-being (Accessed January 05, 2023).

33. Shaw, A, and Kaytaz, ES. Yoga bodies, yoga minds: contextualising the health discourses and practices of modern postural yoga. Anthropol Med. (2021) 28:279–96. doi: 10.1080/13648470.2021.1949943

34. Michalsen, A, and Kessler, C. Science-based yoga - stretching mind, body, and soul. Forsch Komplementmed. (2013) 20:176–8. doi: 10.1159/000353542

35. Smith, BH, Lyons, MD, and Esat, G. Yoga kernels: a public health model for developing and disseminating evidence-based yoga practices. Int J Yoga Therap. (2019) 29:119–26. doi: 10.17761/2019-00024

36. Frazier, MC, Remskar, M, Harden, SM, Barley, KS, David, DE, Guillen, MZ, et al. How is yoga defined and described in the context of mental health and wellbeing interventions? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. BMC Complement Med Ther. (2025).

37. Gothe, NP, and McAuley, E. Yoga and cognition: a meta-analysis of chronic and acute effects. Psychosom Med. (2015) 77:784–97. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000218

38. Mohammad, A, Thakur, P, Kumar, R, Kaur, S, Saini, RV, and Saini, AK. Biological markers for the effects of yoga as a complementary and alternative medicine. J Complement Integr Med. (2019) 16. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2018-0094

39. Birdee, GS, Ayala, SG, and Wallston, KA. Cross-sectional analysis of health-related quality of life and elements of yoga practice. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2017) 17:83. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1599-1

40. McCall, MC, Ward, A, Roberts, NW, and Heneghan, C. Overview of systematic reviews: yoga as a therapeutic intervention for adults with acute and chronic health conditions. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2013) 2013:945895. doi: 10.1155/2013/945895

41. Frazier, MC, and Harden, SM. “Perspectives on yoga principles to promote holistic well-being among community health educators.” Poster presentation presented at: International Society of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity; Uppsala, Sweden. (2023)

42. Dysart, A, and Harden, SM. Mindfulness and understanding of self-Care for Leaders of extension: promoting well-being for health educators and their clients. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:862366. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.862366

43. Gregg, M, and Harden, SM. Pilot feasibility of a yoga and Ayurveda-based virtual group health coaching program to increase flourishing in Cooperative Extension employees of one state system. Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Tech. (2022). Available at: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/110427

44. Wiltsey Stirman, S, Baumann, AA, and Miller, CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:58. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y

45. Rabin, BA, Cain, KL, and Glasgow, RE. Adapting public health and health services interventions in diverse, real-world settings: documentation and iterative guidance of adaptations. (2024). Available online at: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-071321-041652 (Accessed December 16, 2024).

46. Pérez Jolles, M, Lengnick-Hall, R, and Mittman, BS. Core functions and forms of complex health interventions: a patient-centered medical home illustration. J Gen Intern Med. (2019) 34:1032–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4818-7

47. Balis, LE, Houghtaling, B, and Harden, SM. Using implementation strategies in community settings: an introduction to the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) compilation and future directions. Transl Behav Med. (2022) 12:ibac 061. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibac061

48. Powell, BJ, Waltz, TJ, Chinman, MJ, Damschroder, LJ, Smith, JL, Matthieu, MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

49. Ramalingam, NS. Exploration of training as an implementation strategy to promote physical activity within community settings: research, theory, and practice. (2018). Available online at: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/95051 (Accessed September 21, 2023).

50. Glass, TA, and McAtee, MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med. (2006) 62:1650–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044

51. Frazier, MC, Balis, LE, Armbruster, SD, Estabrooks, PA, and Harden, SM. Adaptations to a statewide walking program: use of iterative feedback cycles between research and delivery systems improves fit for over 10 years. Transl Behav Med. (2023) 14:ibad 052. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibad052

52. Estabrooks, PA, Harden, SM, Almeida, FA, Hill, JL, Johnson, SB, Porter, GC, et al. Using integrated research-practice partnerships to move evidence-based principles into practice. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. (2019) 47:176–87. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000194

53. Horton, AG, Gibson, KB, and Curington, AM. Exploring reflective journaling as a learning tool: an interdisciplinary approach. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2021) 35:195–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.09.009

54. Kim-Godwin, YS, Kim, SS, and Gil, M. Journaling for self-care and coping in mothers of troubled children in the community. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2020) 34:50–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.02.005

55. Ullrich, PM, and Lutgendorf, SK. Journaling about stressful events: effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Ann Behav Med. (2002) 24:244–50. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_10

56. Michie, S, van Stralen, MM, and West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. (2011) 6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

57. Yardley, S, Teunissen, PW, and Dornan, T. Experiential learning: transforming theory into practice. Med Teach. (2012) 34:161–4. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.643264

58. Dysart, A, Balis, LE, Daniels, BT, and Harden, SM. Health educator participation in virtual Micro-credentialing increases physical activity in public health competencies. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:780618. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.780618

59. Muir (Zapata), CP, Calderwood, C, and Boncoeur, OD. Matches measure: a visual scale of job burnout. J Appl Psychol. (2023) 108:977–1000. doi: 10.1037/apl0001053

60. Tracy, SJ. Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons (2019). 442 p.

61. Eccles, DW, and Arsal, G. The think aloud method: what is it and how do I use it? Qual Res Sport, Exerc Health. (2017) 9:514–31. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2017.1331501

62. Guest, G, Namey, E, and Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0232076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

63. Hennink, M, and Kaiser, BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

64. Tong, A, Sainsbury, P, and Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

65. Castro, FG, Kellison, JG, Boyd, SJ, and Kopak, A. A methodology for conducting integrative mixed methods research and data analyses. Journal of mixed methods. Research. (2010) 1:342–60. doi: 10.1177/1558689810382916

66. Feicht, T, Wittmann, M, Jose, G, Mock, A, von Hirschhausen, E, and Esch, T. Evaluation of a seven-week web-based happiness training to improve psychological well-being, reduce stress, and enhance mindfulness and flourishing: a randomized controlled occupational health study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2013) 2013:676953. doi: 10.1155/2013/676953

67. A’yuninnisa, RN, Carminati, L, and Wilderom, CPM. Job flourishing research: a systematic literature review. Curr Psychol. (2023) 43:4482–504. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-04618-w

68. Saad, M, de Medeiros, R, and Mosini, AC. Are we ready for a true biopsychosocial-spiritual model? The many meanings of “spiritual”. Medicines (Basel). (2017) 4:79. doi: 10.3390/medicines4040079

69. Michaelsen, MM, and Esch, T. Understanding health behavior change by motivation and reward mechanisms: a review of the literature. Front Behav Neurosci. (2023) 17. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1151918/full

70. Walker, TJ, Are, F, Heredia, NI, Onadeko, K, Saving, EE, Kang, E, et al. Identifying mechanisms of action for implementation strategies using a retrospective implementation mapping logic model approach. Prev Sci. (2025) 26:161–74. doi: 10.1007/s11121-025-01790-2

71. Vanderkruik, R, Woodworth, EC, Frisch, CM, Nelson, S, Dunk, MM, Freeman, MP, et al. Application of implementation science frameworks to inform the adaptation process of an evidence-based eating disorder prevention program for high-risk perinatal individuals. Implementation Res Practice. (2025) 6:26334895251319811. doi: 10.1177/26334895251319811

72. Moore, G, Campbell, M, Copeland, L, Craig, P, Movsisyan, A, Hoddinott, P, et al. Adapting interventions to new contexts—the ADAPT guidance. BMJ. (2021) 374:n1679. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1679

73. Longworth, GR, Goh, K, Agnello, DM, Messiha, K, Beeckman, M, Zapata-Restrepo, JR, et al. A review of implementation and evaluation frameworks for public health interventions to inform co-creation: a health CASCADE study. Health Res Policy Syst. (2024) 22:39. doi: 10.1186/s12961-024-01126-6

74. Morales-Garzón, S, Parker, LA, Hernández-Aguado, I, González-Moro Tolosana, M, Pastor-Valero, M, and Chilet-Rosell, E. Addressing health disparities through community participation: a scoping review of co-creation in public health. Healthcare (Basel). (2023) 11:1034. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11071034

75. Agnello, DM, Balaskas, G, Steiner, A, and Chastin, S. Methods used in co-creation within the health CASCADE co-creation database and gray literature: systematic methods overview. Interact J Med Res. (2024) 13:e59772. doi: 10.2196/59772

76. Gilmartin, H, Lawrence, E, Leonard, C, McCreight, M, Kelley, L, Lippmann, B, et al. Brainwriting Premortem: a novel focus group method to engage stakeholders and identify Preimplementation barriers. J Nurs Care Qual. (2019) 34:94–100. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000360

77. Moullin, JC, Dickson, KS, Stadnick, NA, Rabin, B, and Aarons, GA. Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:1. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6

78. Houghtaling, B, Misyak, S, Serrano, E, Dombrowski, RD, Holston, D, Singleton, CR, et al. Using the exploration, preparation, implementation, and sustainment (EPIS) framework to advance the science and practice of healthy food retail. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2023) 55:245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2022.10.002

79. McCreight, MS, Rabin, BA, Glasgow, RE, Ayele, RA, Leonard, CA, Gilmartin, HM, et al. Using the practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) to qualitatively assess multilevel contextual factors to help plan, implement, evaluate, and disseminate health services programs. Transl Behav Med. (2019) 9:1002–11. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz085

80. Feldstein, AC, and Glasgow, RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. (2008) 34:228–43. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34030-6

81. Powell, T, and Yuma-Guerrero, P. Supporting community health workers after a disaster: findings from a mixed-methods pilot evaluation study of a psychoeducational intervention. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2016) 10:754–61. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.40

82. Stupplebeen, DA, Sentell, TL, Pirkle, CM, Juan, B, Barnett-Sherrill, AT, Humphry, JW, et al. Community health workers in action: community-clinical linkages for diabetes prevention and hypertension management at 3 community health centers. Hawaii J Med Public Health. (2019) 78:15–22.

83. Klesges, LM, Estabrooks, PA, Dzewaltowski, DA, Bull, SS, and Glasgow, RE. Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med. (2005) 29:66–75. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_10

84. Balis, LE, Strayer, TE, Ramalingam, N, and Harden, SM. Beginning with the end in mind: contextual considerations for scaling-out a community-based intervention. Front Public Health. (2018) 6:357. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00357

85. Harris, CV. “The extension service is not an integration agency”: the idea of race in the cooperative extension service. Agric Hist. (2008) 82:193–219. doi: 10.3098/ah.2008.82.2.193

86. Baum, F, Mac Dougall, C, and Smith, D. Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2006) 60:854–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028662

Keywords: co-creation, flourishing, wellbeing, holistic, yoga, adaptation, implementation, dissemination

Citation: Frazier MC, Pullin MJ and Harden SM (2025) Patience is a virtue: lessons from a participatory approach to contextually tailor and co-create an employee wellness intervention for community health educators. Front. Public Health. 13:1634264. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1634264

Edited by:

Marília Silva Paulo, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, PortugalReviewed by:

Zhiyong Han, Anhui University of Finance and Economics, ChinaBogusława Serzysko, Higher School of Applied Sciences in Ruda Śląska, Poland

Syed Sajid Husain Kazmi, Amity University, India

Copyright © 2025 Frazier, Pullin and Harden. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mary C. Frazier, bWNmNzEyQHZ0LmVkdQ==

Mary C. Frazier

Mary C. Frazier Megan J. Pullin

Megan J. Pullin Samantha M. Harden

Samantha M. Harden