- 1Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences, Tongji Shanxi Hospital, Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

- 2College of Digital Arts, Communication University of Shanxi, Taiyuan, China

- 3Faculty of Foreign Languages, Zhejiang Wanli University, Ningbo, China

Background: Short videos that popularize health science have become essential for disseminating health information and enhancing public health literacy. However, previous research has primarily focused on health information content, with a significant gap in assessing the quality of health science popularization in short videos.

Methods: This study developed a quality assessment scale for the popularization of health science short videos based on multimodal theory, utilizing literature analysis and the creation of custom measurement items. Data were collected from scales completed by 796 residents through online surveys conducted on mobile devices. Both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were employed to evaluate the quality of mobile health science popularized short videos.

Results: The results revealed that the quality scale for health science popularization in short videos could be divided into seven dimensions and 22 indicators, each a significant determinant of video quality.

Conclusion: This research provides a more intuitive, reliable, and standardized tool for assessing the quality of health science popularization in short videos. Also, it offers essential guidance for the future design, development, and promotion of short health science popularization videos.

Introduction

With the increasing prevalence of mobile social media, short mobile videos have become a vital tool for disseminating health-related scientific information around the world (1). According to the “Digital 2023 Global Overview Report,” TikTok, YouTube Shorts, and Instagram Reels have over 2.5 billion monthly active users, and the number of views for health-related content on these platforms alone reaches hundreds of billions (2, 3). People can use these platforms to search for and obtain relevant information and guidance on health, thereby improving their health literacy (4–6). Although short videos have greatly facilitated people’s access to health knowledge, there are still some limitations, such as the authenticity and quality of health information, which influence users’ intentions (7, 8).

In China, short videos have also become an important medium for health education. According to the “2019 Health Science Popularization Videos Insight Report,” among more than 9,000 survey participants, 92.1% indicated that they had watched videos about health science, and 55.3% used these videos to engage with healthy lifestyles (9). This finding highlights the importance of short mobile videos for spreading health knowledge. They change how the public accesses health information, deepen their understanding of health knowledge, and enhance public health literacy (10). Similarly, in the “Guidelines on Establishing a Comprehensive All-Media Health Science Knowledge Publication and Dissemination Mechanism” released in May 2022, the National Health Commission emphasized that various entities, including health departments, internet platforms, and media organizations, should work together to enhance the supply of high-quality health science knowledge to meet the growing health needs of the public (11). These trends demonstrate that the high-quality development and effective dissemination of health science information are highly valued at corporate, societal, and national levels.

Short mobile videos have become a significant platform for disseminating health science information, establishing an interactive bridge between users and this information. However, the quality of short video content for health science popularization varies significantly at this stage because there is a lack of adequate regulatory bodies and scientific evaluation standards. Misleading or false information can even harm users, thus disrupting the usual channels for disseminating health science information and damaging the standard supply and demand relationship between users and health information (12–14). In response to these challenges, some scholars have conducted research from multiple perspectives, including the paths and mechanisms of disseminating health science information (15, 16), users’ needs perception and its impact (17, 18), and the design elements of health science videos (19, 20). Similarly, some scholars have used methods such as DISCERN, JAMA Benchmark, Global Quality Score (GQS), and PEMAT (A/V) to assess the quality of health science popularization short videos (21–23). However, these assessment scales were originally applied to textual materials or long videos, and they lack specificity for 15–60-s multimodal short videos. Some scholars have also used large language models (LLMs) to assess the quality of medical information on short-video platforms, but the technique is still in the experimental stage and has not yet developed into an industry solution that can be directly applied (24). Although these studies have, to some extent, promoted the development of the field, current research lacks dedicated and standardized tools to assess the health science popularization short videos. Furthermore, existing scales lack systematic reliability and validity tests (1, 17). Specifically, the unique ecosystem of short videos presents a theoretically complex definition of quality. This leads to potential discrepancies between evaluation results and users’ actual needs (25), which in turn affects whether the content of health science popularization short videos can meet the core needs of users and limits the potential for high-quality development of health science popularization short videos.

Health science popularization short videos as comprehensive carriers of health information, primarily involving topics, content, presentation forms, and dissemination methods (16). In contrast to legacy media and text-centric formats, health science popularized short videos are marked by fragmented narrative units, high-intensity audiovisual cues, and algorithmically mediated circulation, together producing a complex, reciprocal interactional ecology. While established frameworks such as source credibility, cognitive-load theory, and the Health Belief Model provide a sound conceptual substrate, they are, in isolation, inadequate for apprehending the multidimensionality of user experience in this format. Therefore, this study adopts multimodal theory to investigate how multiple semiotic modes—such as visuals, text, and audio—interact to influence users’ perceptions of video quality (26, 27). In summary, this study aims to systematically develop and validate a multidimensional scale that reflects users’ overall assessment of the quality of short videos focused on health science popularization within this dynamic, multimodal environment. This scale not only provides a theoretical framework grounded in multimodal discourse but also offers a user-centered assessment tool to support the high-quality development of digital health communication and enhance public health literacy in China.

Literature review

Evaluation of the quality of short videos on health science

Health science popularization short videos are public health educational videos disseminated through mobile internet platforms to convey scientific health knowledge to the general public. These videos embody authority, rigor, accessibility, and interactivity among users. The quality of the content can significantly impact its dissemination effectiveness (28). Existing research indicates that the quality of health information can affect users’ perceptions and emotional responses to health science videos, influencing their continued usage intentions (17, 20). Thus, the quality of health information plays a crucial role in videos that popularize health science. Evaluation is one of the essential methods for screening health information quality and can play a significant role in the evaluation system (12, 29). Current research on evaluating health information quality primarily focuses on two aspects. On one hand, professional medical personnel discuss the quality of health information and the tools for its evaluation (21). In contrast, the general public assesses the quality of health information (30). Although both approaches evaluate the quality of health information, there is a fundamental difference between them. Medical professionals evaluate and classify health information from a professional medical perspective. This professional assessment and classification can cause cognitive barriers for non-professional, ordinary users, leading to various adverse consequences and impacts (31). Similarly, due to ordinary users’ own circumstances and differences, they may also have different opinions on the quality of health information (25, 30). However, the general public represents the core user group for health science popularization in short videos. Evaluating user experiences with health information directly reflects the quality of videos that popularize health science. Therefore, user evaluations are a critical factor in assessing the quality of health science videos.

Short videos serve as effective carriers for disseminating health information, fulfilling both the application and communicative functions of this information (32). Previous research has explored the impact of health science popularization in short videos in various dimensions, including social behavior (33), security and privacy (34), and artistic and technical aspects (19), uncovering their potential mechanisms of influence. Although these studies have positively contributed to the development of short videos for health science popularization, research on tools for evaluating the quality of these videos has not received sufficient attention. However, the quality of health science popularized in short videos directly affects users’ perception of health information and subsequent usage behaviors (17). Therefore, a practical evaluation of the quality of health science popularization through short videos plays a vital role in developing health education initiatives in our country and enhancing public health literacy.

Evaluation dimensions of the quality of short videos of health science popularization

Health science popularization short videos are a comprehensive format for presenting health science information involving multiple evaluation dimensions. In past research, scholars have primarily evaluated health information based on three aspects: information characteristics (25), platform design (20, 25), and individual emotions (35). While these dimensions have been effective in assessing health information and have been widely recognized and applied by scholars, there remain issues in evaluating the quality of health information in streaming and short video applications, demonstrating the limitations of a single aspect of the evaluation dimension (12, 36). Given that the quality of health science popularization short videos is an umbrella-like concept involving health information, health services, video design, content format, and user experience, multimodal theory can provide a robust theoretical framework. The rationale for utilizing this theory lies in its ability to elucidate how multiple symbolic resources (such as text, images, sound, and interaction) collaborate to construct a multi-dimensional evaluation system through interaction (26, 27, 37). Compared with prior models that rely on textual criteria or single-mode evaluation tools (such as DISCERN, JAMA Benchmark, and GQS), multimodal theory enables a more nuanced and realistic analysis of how users perceive and evaluate video-based health information (36, 38). Therefore, we utilize a multidimensional perspective to measure and assess quality, taking into account the interdependent coupling effects and configurational relationships among various variables (19, 39). This approach will improve both the accuracy and effectiveness of measuring the quality of short videos that promote health science.

Though existing studies have explored and researched health science popularization information using different theoretical models; however, due to the limitations inherent in each theoretical model, these studies do not comprehensively reflect the quality of health science popularization of short video information (20, 39). To address this issue, this research plans to use multimodal theory as a foundation to delve into different types of literature and explore the dimensions of health science popularization, short video quality from the user perspective, including aspects such as the health blogger’s image, professionalism, video content, interaction, safety, emotion, and practicality.

Method

Measure the generation of items

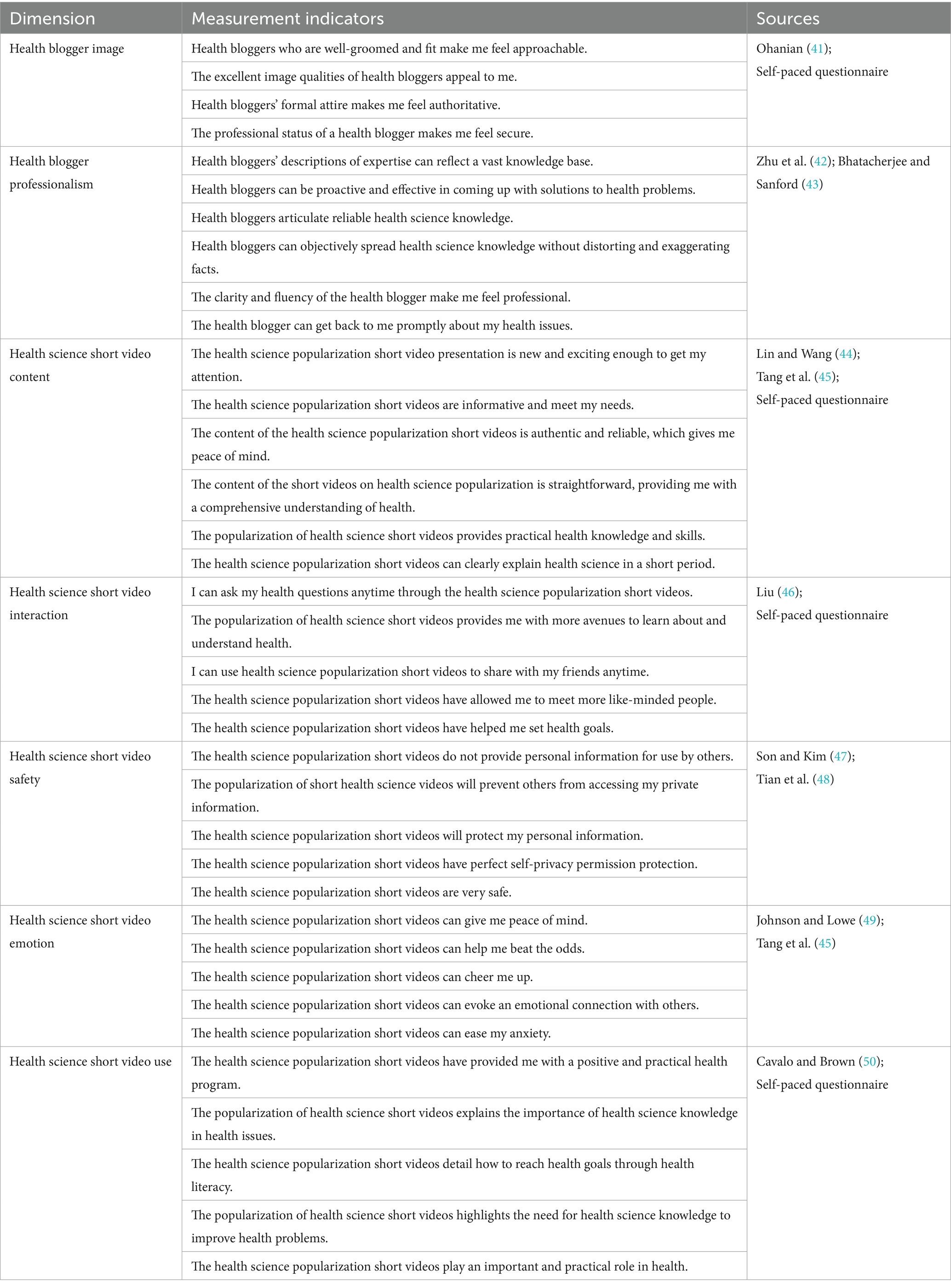

According to the three-step scale development procedure suggested by Churchill and Iacobucci (40), we conducted a systematic review of existing literature covering areas such as health information quality, online community user experience, and short video engagement. Measurement indicators are defined based on the content of the measurement subject and specific domestic conditions. Established scales are used, with appropriate modifications made according to the research context. Drawing from the studies by Ohanian (41), Zhu et al. (42), Bhattacharjee and Sanford (43), Lin and Wang (44), Tang et al. (45), Liu (46), Son and Kim (47), Tian et al. (48), Johnson and Lowe (49), and Cavalo and Brown (50), a scale was developed to measure the quality of mobile health science popularization short videos in China. The scale items cover dimensions related to the health vlogger’s image, professionalism, and information content.

To ensure that the measurement items of the scale adequately cover the measurement factors, this study is based on both theoretical and empirical foundations. A panel of six experts, comprising three professors specializing in digital media within communication studies and three chief physicians experienced in public health education, was convened to assess and enhance the measurement items of the scale. They evaluated each item based on three criteria: relevance (Is the item pertinent to the construct?), clarity (Is the item articulated clearly and without ambiguity?), and comprehensiveness (Does the item pool sufficiently encompass the dimension?). Based on their quantitative ratings and qualitative feedback, some items were either removed due to ambiguity or merged due to conceptual overlap. Guided by the theories of source credibility (41), cognitive load (51), social support (52), and the health belief model (53), six additional items were incorporated: “The professional status of a health blogger makes me feel secure.”; “The clarity and fluency of the health blogger made me feel professional.”; “The health science popularization short videos can clearly explain health science in a short period.”; “The health science popularization short videos have allowed me to meet more like-minded people.”; “The health science popularization short videos are very safe.”; and “The health science popularization short videos play an important and practical role in health.” This represents professionalism, safety, utility, and interactivity, which are essential to addressing the gaps in measurement factors. Finally, the scale items will be reviewed and refined to ensure the correct use of terminology, clarity of language, completeness of content, and the absence of any repetition or omissions. Meanwhile, the bilingual translation-back translation method was performed by two Chinese-English bilingual experts with doctoral degrees to reduce semantic bias, to enhance the consistency of the cross-cultural measurements, and to ensure the applicability of the scales in this study.

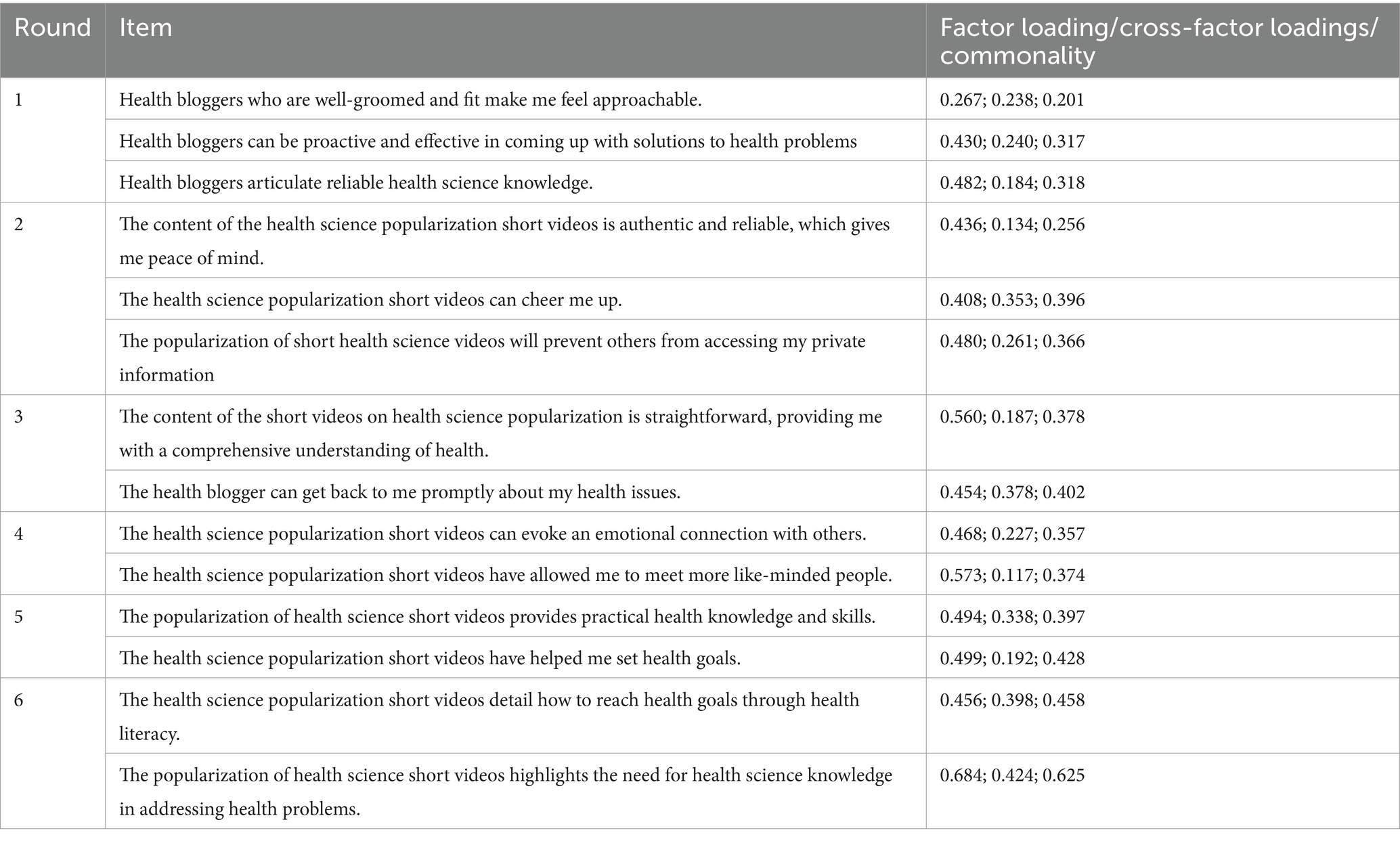

Based on the information above, a preliminary scale of 36 items has been developed to assess the quality of mobile health science popularization short videos. A convenience sampling method was used to conduct a pilot survey with 50 residents who regularly watch health science popularization short videos to enhance the scale’s measurement reliability and content validity. The results indicated a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.845. Additionally, five experts with backgrounds in communication and medicine were invited to assess the scale, yielding an Inter-Objective Consistency Index (IOC) of approximately 1 (54). These results demonstrate that the scale possesses excellent reliability and validity, thereby warranting the distribution of the formal questionnaire (Table 1).

Table 1. Indicators for measuring the quality of short health science videos and literature sources.

The formal questionnaire is divided into two parts. The first part collects sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, occupation, and income. The second part consists of the measurement items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “strongly disagree,” 2 represents “disagree,” 3 represents “neutral,” 4 represents “agree,” and 5 represents “strongly agree.”

Data collection and sample characteristics

This study’s survey was created using the Questionnaire Star system and distributed via mobile phones. Online distribution offers several advantages, such as not being limited to a single geographical location, low costs, and rapid data collection (55). To increase participants’ willingness to engage, those who completed the survey were randomly rewarded with red envelopes containing monetary rewards ranging from 2 to 5 yuan. Currently, second- and third-tier cities in China are the centers of city development and population flow (56). To consider the universality of the sample and the issues arising from regional differences (such as information literacy and health literacy), all of our respondents are from second- and third-tier cities. The survey collected 870 responses, of which 74 were excluded due to respondents not watching health science popularization short videos or completing the survey in less than 3 min, leaving 796 valid responses, yielding a validity rate of 91.4%. The sample size has fully reached the standard of 10 times the number of observational indicators ( ) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)-based power analysis for exploratory and confirmatory analyses allowing for statistical analysis to be conducted (57, 58). The total sample (S = 796) was randomly divided into two parts: Sample 1 (S1 = 398) was used for exploratory factor analysis, and Sample 2 (S2 = 398) for confirmatory factor analysis.

In terms of demographic characteristics of the sample, males accounted for 48.2%, and females 51.8%. The age distribution was as follows: 18–35 years old represented 23.5%, 36–50 years old represented 40.3%, 50–65 years old represented 27.4%, and over 65 years old represented 8.8%. Professionally, the sample was predominantly composed of students, private sector employees, self-employed individuals, civil servants, and public sector employees, accounting for 66.4%. A high school diploma or college degree was the most common regarding educational attainment, representing 69.7% of the sample. As for income, most respondents earned between 3,001 and 7,000 renminbi (RMB), accounting for 52.3% of the analysis.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis and results

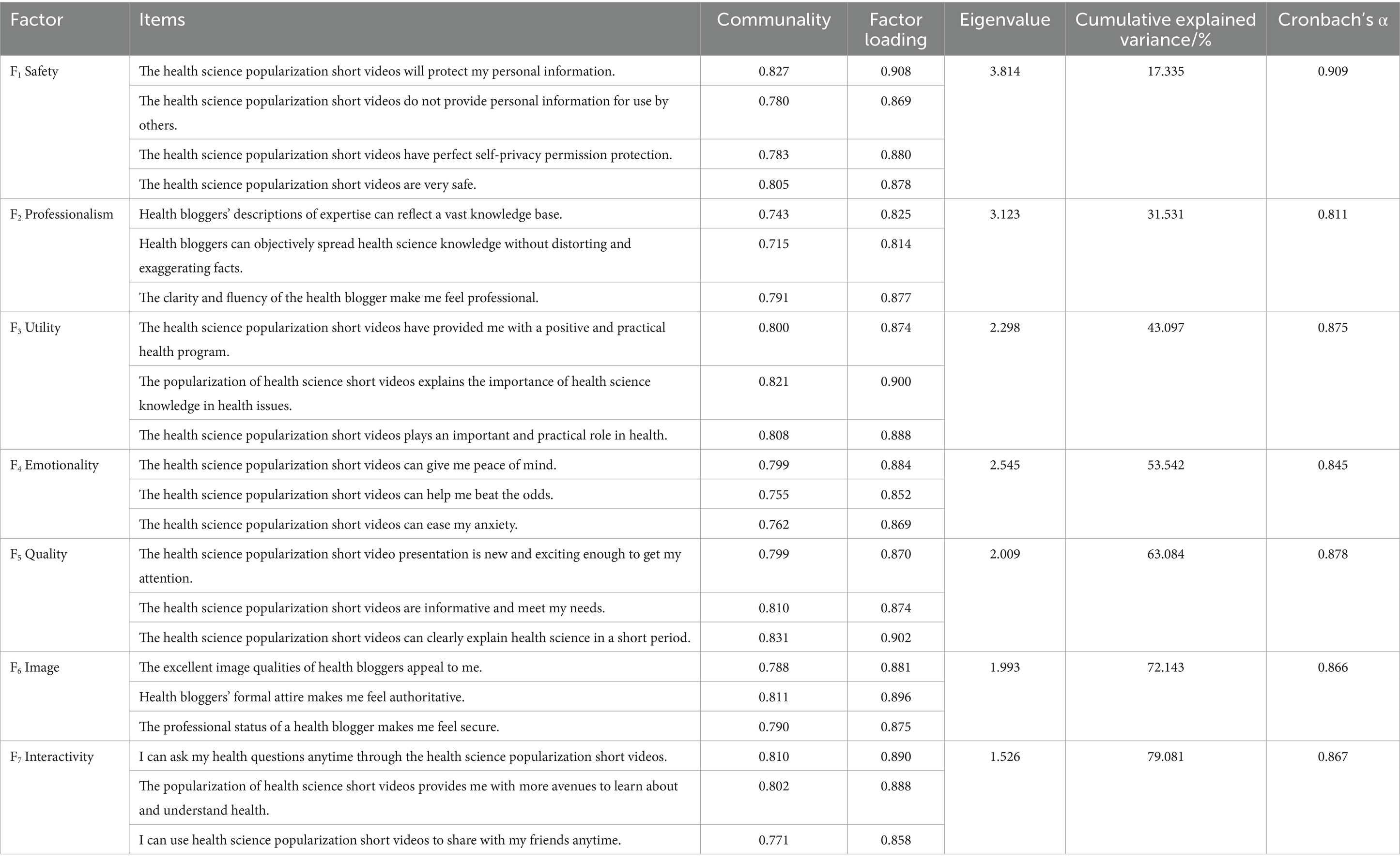

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the initial scale items to explore the structural dimensions of health science popularization of short video quality. Using Sample 1 (S1 = 398), the 36 scale items were subjected to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The results indicated a KMO value of 0.818, more than the acceptable threshold of 0.70, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity resulted in p < 0.001, which is less than 0.05, suggesting that the items are suitable for factor analysis. Principal component analysis and varimax rotation were used to obtain factor loadings, with eigenvalues greater than 1 as the criterion for factor extraction. Items with commonalities less than 0.5 (40), factor loadings below 0.5 (57), cross-loadings greater than 0.4 (59), and inconsistent with the meaning of the associated factor were excluded. Additionally, a Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) was conducted to screen the items, and items with a CITC coefficient less than 0.4 were removed (40). Using the item-by-item deletion method, first delete items with low factor loadings, high cross-factor loadings, or low commonality, and then gradually optimize the model structure (60). Through six rounds of factor analysis, 14 items that did not meet the requirements were eliminated (Table 2), leaving 22 items. These extracted seven factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining 79.08% of the total variance, which exceeds the 60% standard (61), indicating that these factors adequately represent most of the information of the items. The reliability test results indicated that Cronbach’s α coefficients for the seven factors were above 0.70 (62), which is considered acceptable. Overall, the scale’s reliability is reliable, and its dimensional structure is relatively stable (Table 3).

Based on the content and characteristics of the items encompassed by the seven aggregated factors, the seven aggregated factors are named as follows: F1 Safety, F2 Professionalism, F3 Utility, F4 Emotionality, F5 Quality, F6 Image, and F7 Interactivity. Specifically, F1 Safety includes four items that reflect the ability of health science popularization short videos to protect users’ personal privacy and safety. F2 Professionalism comprises three items that capture the professional attributes of health vloggers within health science popularization short videos. F3 Utility contains three items designed to measure the practicality and importance of popularizing short videos among users of health science. F4 Emotionality includes three items that demonstrate how health science popularization short videos meet users’ emotional needs. F5 Quality consists of three items that assess the impact of the content quality of health science popularization short videos on users. F6 Image encompasses three items that reflect the influence of the image and demeanor of health vloggers on users of health science popularization short videos. F7 Interactivity includes three items that illustrate the effect of health science popularization and short videos on user information and social interaction.

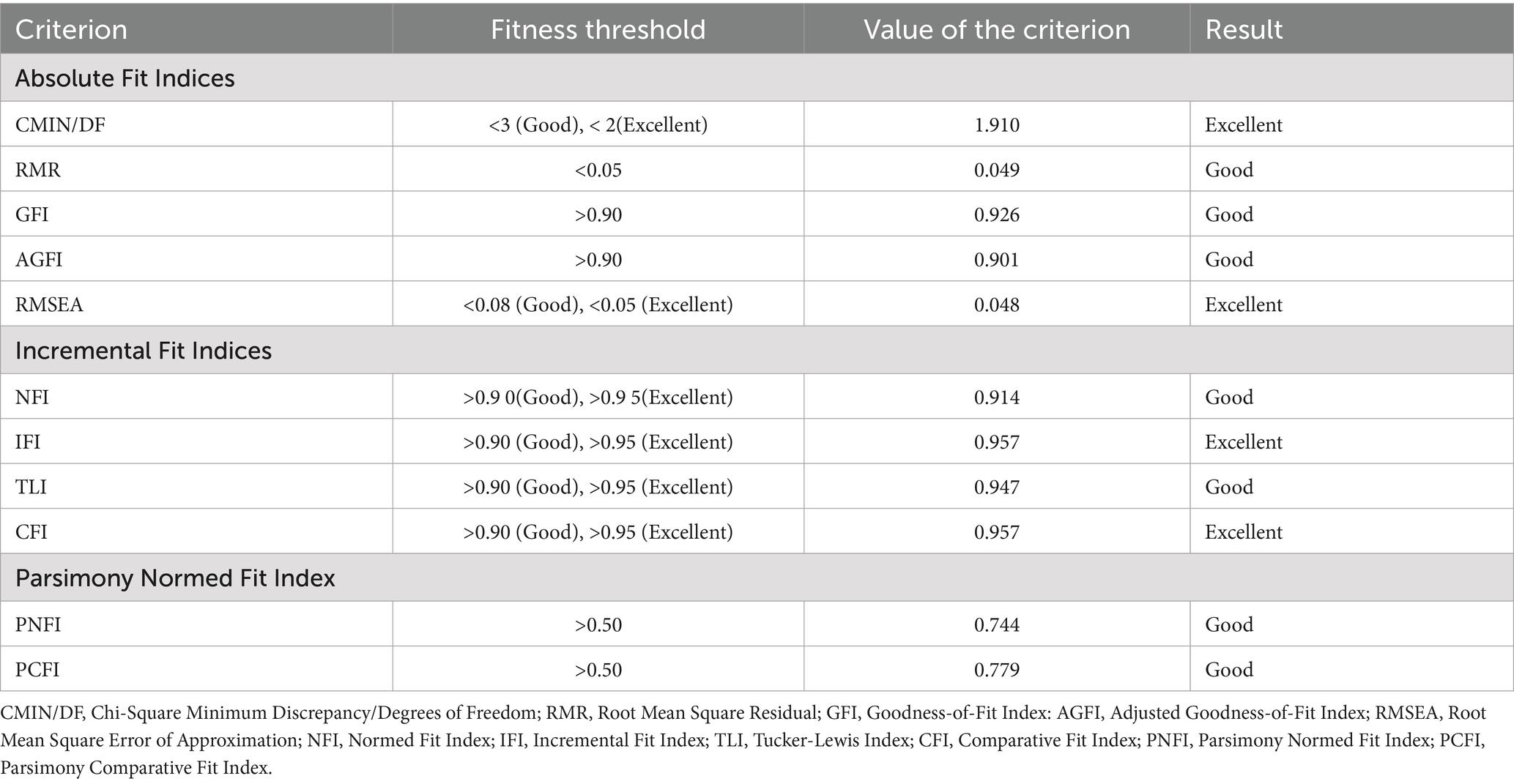

Confirmatory factor analysis and results

The Amos 23.0 software was utilized to conduct confirmatory factor analysis on the data from Sample 2 (S2 = 398), primarily because this software is known for reducing bias in estimations and providing more accurate computational results within structural equation modeling. The model’s fit was assessed using various indices to determine how well the model developed through exploratory factor analysis matches the observed data. Following the recommendations of Hair et al. (62), this study selected the fit indices and criteria shown in Table 4 for evaluation. Global fit was satisfactory (Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.957; RMSEA = 0.048). Consistent with parsimony guidelines, we inspected modification indices (MI) and found no values exceeding 15 (maximum = 12.75). This indicates negligible local misfit; therefore, the theorized factor structure remained unchanged in accordance with parsimony recommendations (63). The results indicate that the model meets the established criteria, demonstrating satisfactory model fit.

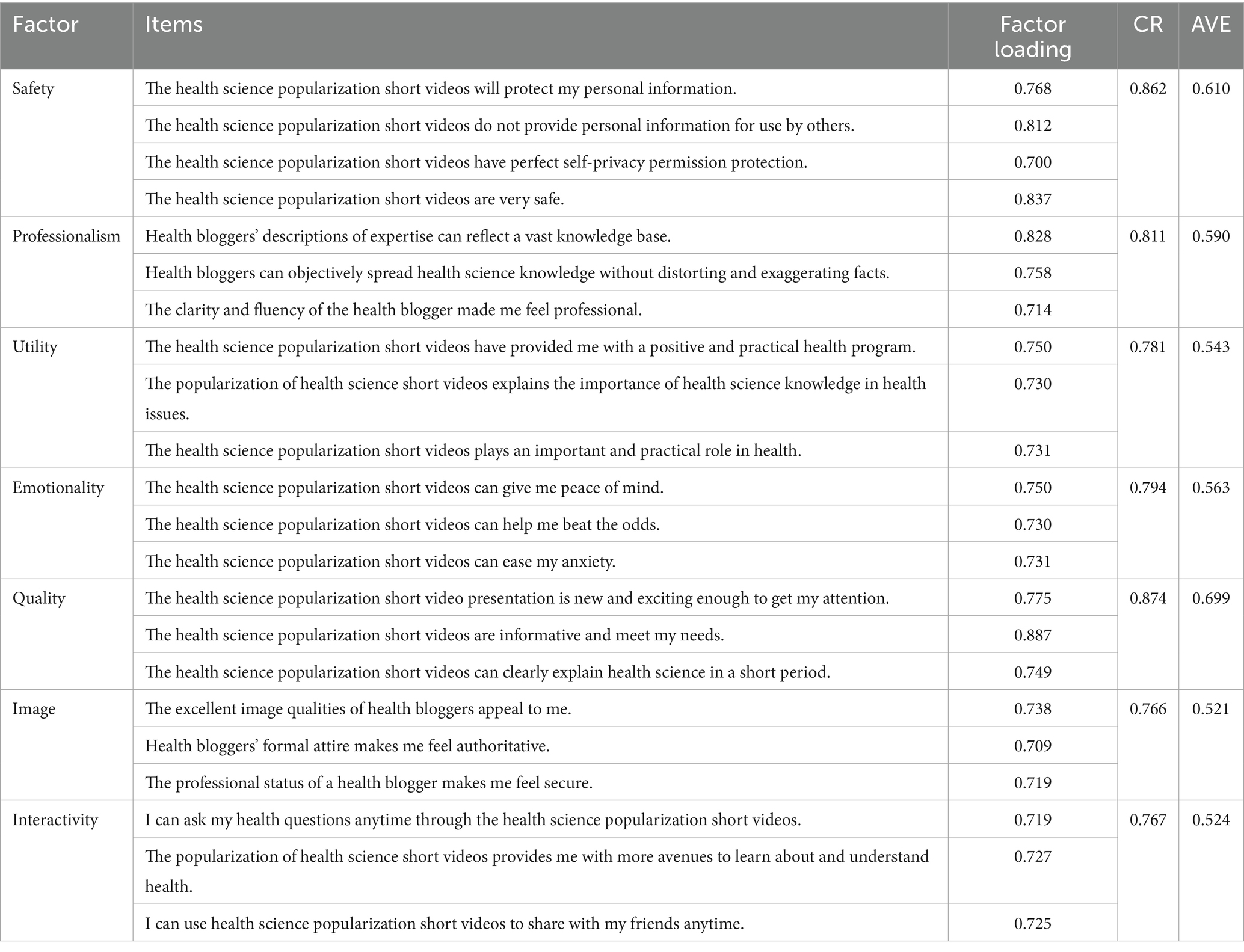

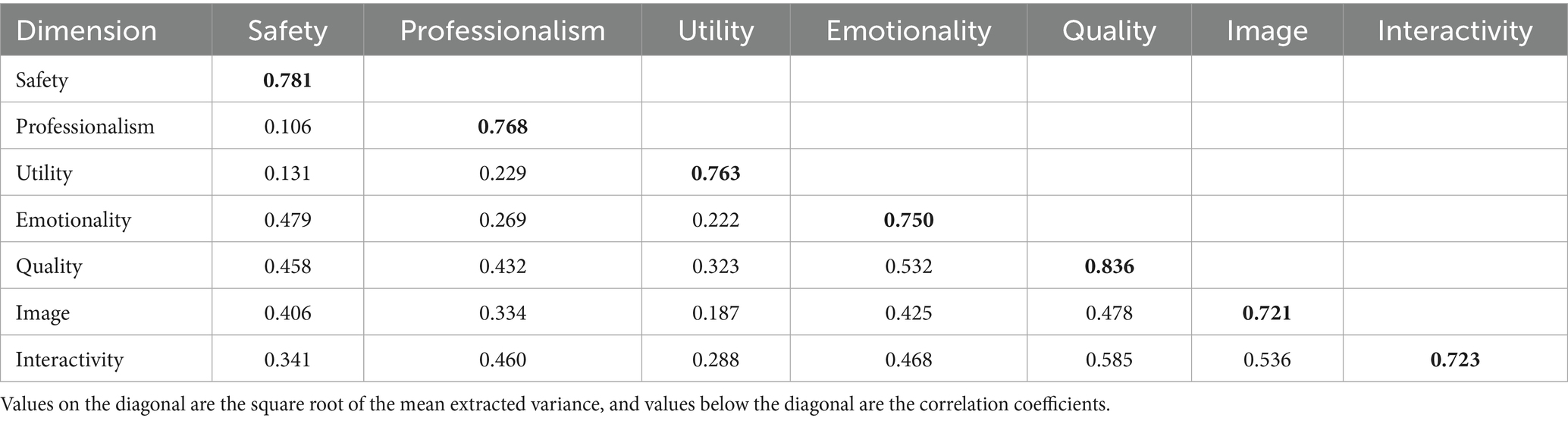

This study conducted a reliability and validity test of the scale, including composite reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and criterion validity. In this study, the composite reliability for the seven factors of the scale ranged from 0.766 to 0.874, all above the 0.70 threshold, indicating strong reliability of the scale (64). The evaluation of convergent validity primarily considered the following criteria: standardized factor loadings greater than 0.50 (65); composite reliability (CR) greater than 0.70 (64); and average variance extracted (AVE) greater than 0.50 (66). Meeting these conditions suggests good convergent validity for the scale. The results from the confirmatory factor analysis (Table 5) show that the standardized factor loadings for the seven factors in this study’s scale are all above 0.70, with their composite reliability values also exceeding 0.70, and the AVE values are all above 0.50, indicating excellent convergent validity.

If the correlation coefficient between a factor and all other factors is less than the square root of its AVE, then the discriminant validity is considered satisfactory (66). As shown in Table 6, the square root of the AVE values for the seven factors in this scale is higher than the correlation coefficients between each factor and all other factors. Therefore, the scale exhibits excellent discriminant validity.

Predictive validity analysis and results

Predictive validity is used to assess the extent to which a scale can predict outcomes related or unrelated to the measured construct (67). In the study of short videos, empirical evidence demonstrates that users’ evaluations of content, interaction, entertainment, and privacy security can influence their satisfaction and willingness to continue using the platform (68–70). Similarly, health science popularization short videos, as a type of short video, encompass inherent characteristics of short videos (71). Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that users’ perceptions of various factors, such as content and format, in health science popularization short videos will also affect their satisfaction and willingness to continue using them. Additionally, health science information is a primary method and crucial pathway for enhancing public health literacy (72). Xuan et al. (73) argue that the content of health science information influences people’s perceptions of health knowledge, trust, and willingness to continue using it. Similarly, the quality of health science information directly impacts people’s satisfaction, thereby affecting their usage intentions (33, 74). It is evident that users’ perceptions of health science popularization short videos are fundamentally perceptions of health information content and quality, which influence users’ emotional responses and usage intentions.

In summary, this study selects user satisfaction and continued usage intention as criterion variables for correlational validity (75). The aforementioned correlation criteria were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “strongly disagree,” 2 represents “disagree,” 3 represents “neutral,” 4 represents “agree,” and 5 represents “strongly agree.” The questionnaire content was adapted to align with Chinese linguistic expressions and the specific context of this study. A total of 302 questionnaires were distributed both online and offline, with 54 incomplete or invalid responses excluded. The final sample consisted of 248 valid questionnaires used for criterion validity analysis. All items in the questionnaire had Cronbach’s α coefficients greater than 0.70.

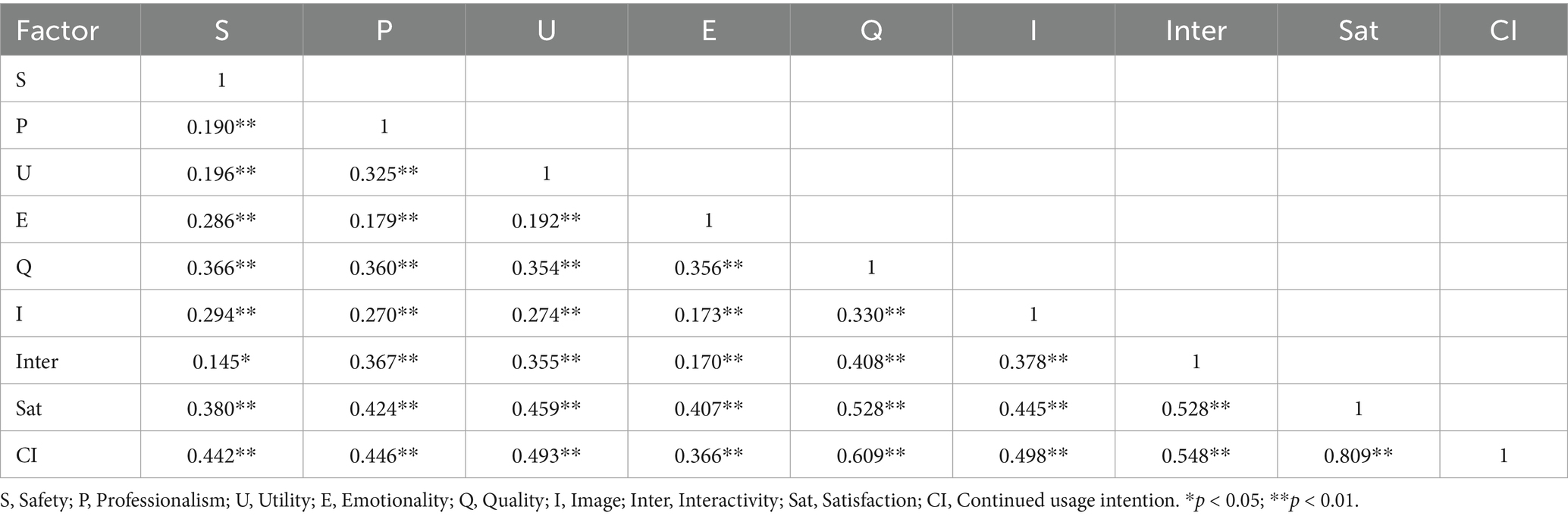

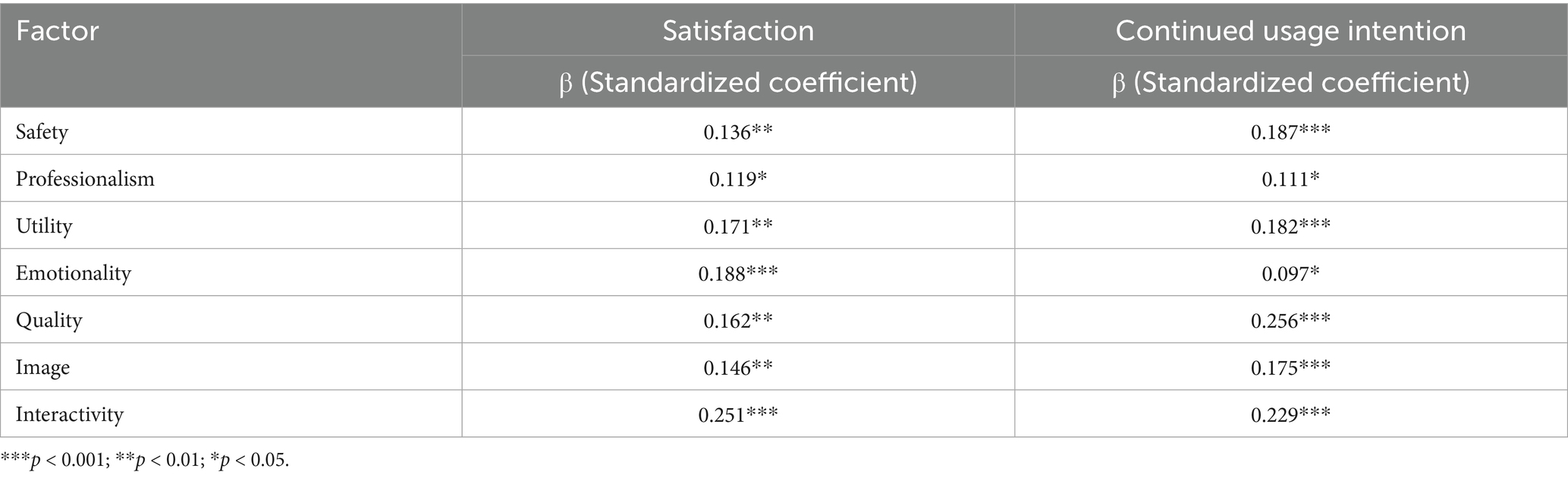

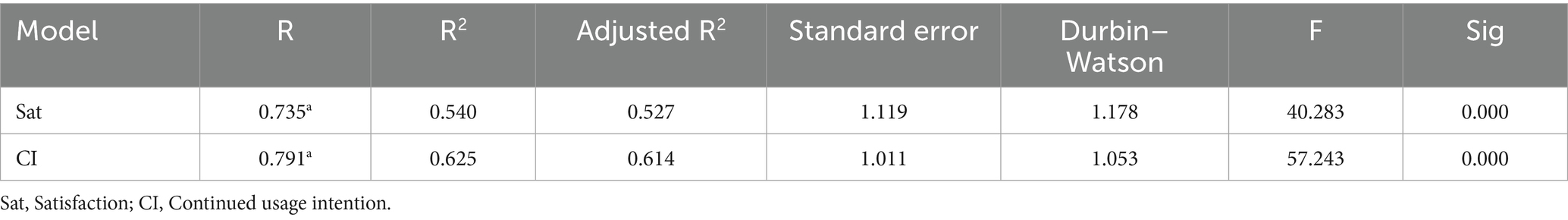

This study employed correlation and regression analyses to further assess the criterion-related validity of the health science popularization short video quality scale. The correlation analysis results indicated that the seven dimensions of the health science popularization short video quality scale positively correlate with two criterion constructs: user satisfaction and continued usage intention (p < 0.05). All pairwise correlation coefficients between variables were greater than 0. (Table 7). The regression analysis used factors affecting the quality of health science popularized short videos as independent variables, while the two criterion constructs served as dependent variables. The results of Table 8 showed that the regression models for the impact factors on user satisfaction [R2 = 0.540, F(7, 390) = 40.283, p < 0.001] and continued usage intention [R2 = 0.625, F(7, 390) = 57.243, p < 0.001] were statistically significant, both indicating adequate explanatory power with R2 values exceeding 50%. Notably, the scale measuring the quality of health science popularization in short videos demonstrates stronger explanatory power for users’ continued usage intentions. Additionally, the Durbin–Watson values for satisfaction (1.178) and continued usage intention (1.053) suggest positive autocorrelation in the residuals, which clears the potential issue with the model. In all, based on the above indices, these two regression models demonstrate acceptable model fit. Besides, all the VIF values of the seven predictors were less than 5, indicating no multicollinearity issues among the independent variables (76).

Table 8. The results of regression model statistics for user satisfaction and continued usage intention.

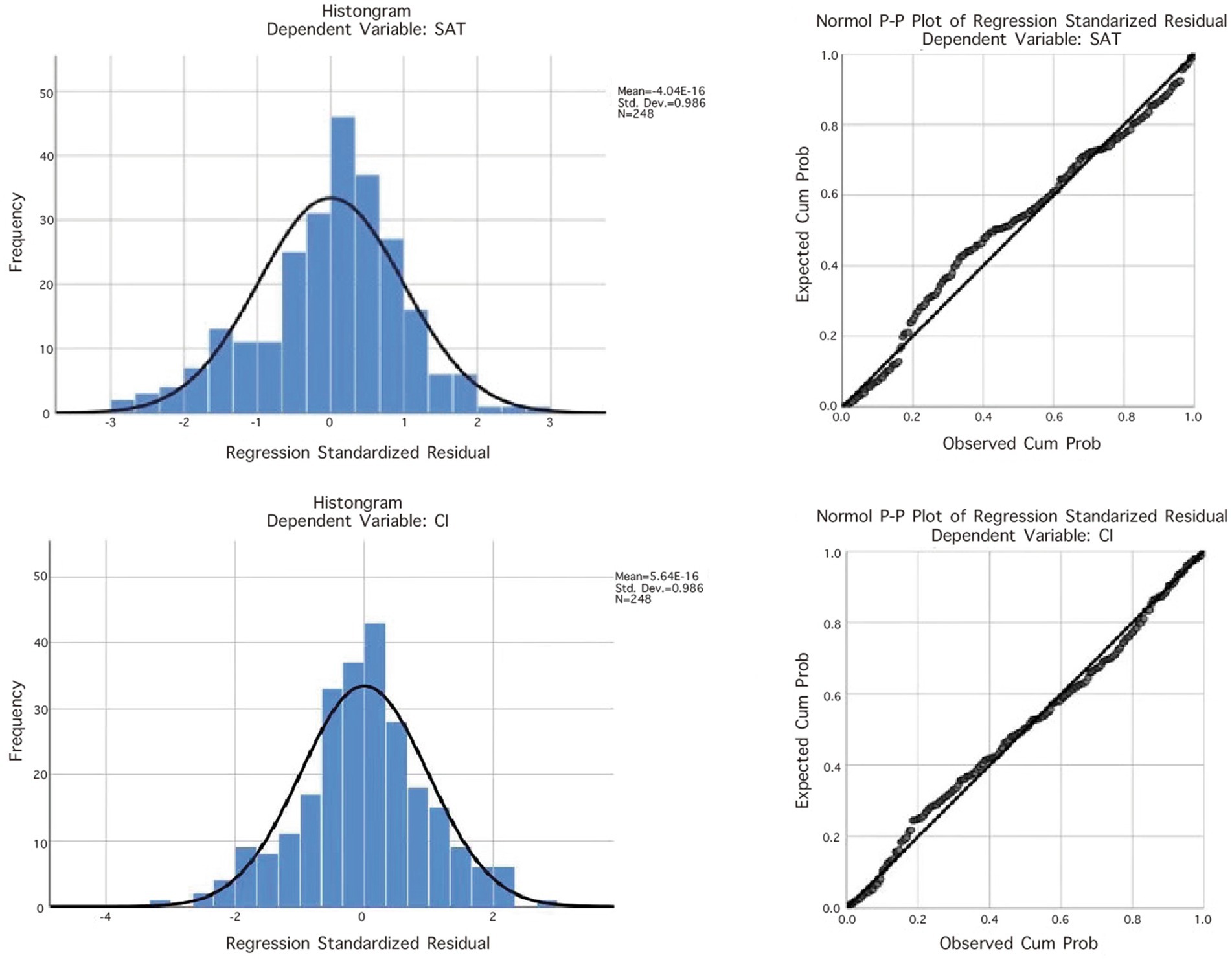

The regression models for each dimension of the quality of health science popularization short videos on user satisfaction and continued usage intention are all significant and positively influence these variables (Table 9). Analysis of the residual histograms and residual plots for the models of user satisfaction and continued usage intention shows that the mean residuals are close to zero, with standard deviations close to one. The standardized residuals are distributed around the zero value, exhibiting a roughly symmetrical pattern above and below the zero line, indicating that the linear regression meets the normality condition, and the homoscedasticity and independence conditions of the data are met (Figure 1). To further validate the robustness of the models, the interaction effects of the seven factors of the quality of health science popularization short videos on user satisfaction and continued usage intention were examined. The results indicate that the interaction terms of the seven dimensions significantly influence user satisfaction (β = 0.615, t = 12.218, p < 0.01) and continued usage intention (β = 0.670, t = 14.161, p < 0.01). Therefore, the health science short popularization video quality scale demonstrates good predictive validity.

In summary, after rigorous steps in scale development and validation, a scale for assessing the quality of health science popularization short videos has been established. Additionally, through a series of reliability and validity tests, the reliability, stability, and scientific validity of this scale have been ensured.

Discussion

Based on a literature review and grounded in multimodal theory, this study developed a scale to assess the quality of health science popularization short videos in China. This paper provides significant theoretical insights into the study of health science popularization short video quality and offers practical guidance for the design, innovation, and development of health science popularization short videos.

Theoretical implications

First, this study operationalizes the abstract concept of health science by popularizing short videos for quantitative measurement. The project has expanded the scope of related research in this field with new research scenarios. Specifically, the research developed and validated a scale for assessing the quality of health science popularization short videos, categorizing and summarizing the various factors influencing their quality. It more accurately delineates the dimensions of health science popularization, short video quality, and their interrelations, effectively supporting and supplementing existing research on it. For instance, in assessing the quality of health science popularization short videos, it is necessary not only to evaluate aspects such as the content, quality, and interaction (16, 17, 19), but also to assess the portrayal of characters, their traits, and their professional performance within the videos. In particular, integrating seven dimensions to assess the relationship between user behavior and the quality of health education videos extends existing research frameworks and integrates theory. This approach allows for a more comprehensive interpretation of video quality. Consequently, the scale constructed can measure and reflect the quality of health science popularization short videos more intuitively and reliably, providing a theoretical framework and measurement tools for subsequent related research.

Second, based on multimodal theory, this study precisely categorizes the content of health science popularization short videos, expanding into various modalities such as characters, emotions, safety, and interaction. This approach enhances the application of multimodal theory in health science popularization short videos, strengthens the structural relationship between theory and practice, and provides scientific theoretical guidance for practical applications. Additionally, the research confirms the importance of different independent informational modalities in the construction and transmission process of health science popularization short videos. It also highlights the significance of interaction and integration between different modalities in enhancing the quality of information. Specifically, the factors that affect the quality of health science popularization include short video information, the positive image of health vloggers, and their professionalism, all of which can effectively attract audiences. Safe and practical health information provides users with a positive emotional experience, security, and practicality. Effective interaction and sharing can enhance communication among users and between users and health vloggers, not only fulfilling the social needs of the user community but also efficiently spreading health information and promoting the improvement of public health literacy (33, 74). It is evident that relatively independent factors in health science popularization short videos can significantly influence the quality of the videos and user engagement. The interplay and superposition of these factors not only play a crucial role in determining the quality of health science popularization short videos but also have a lasting impact on users’ emotions and willingness to use such content. Therefore, research has confirmed that in the new media environment, information is inextricably linked to its presentation and the medium itself, further confirming the importance of multimodality. Meanwhile, the research results emphasize the necessity of transcending text-centric assessment models and highlight the importance of interactions between different symbolic modes in shaping user perceptions and subsequent intentions. The interactive relationships among these factors can provide a more objective and accurate reflection of the quality of short videos focused on health science popularization. In summary, these findings further enrich the implications of multimodal theory in assessing the popularity of short video quality in health science.

Practical implications

The instrument validated here operationalizes the elusive construct of quality, converting it into implementable tactics for stakeholders across the health science popularization short video ecosystem. For digital health content creators, the seven dimensions schema functions as an empirically anchored resource for diagnostic self-assessment and for tuning content-optimization workflows. By attending—systematically—to facets spanning professional behavior and utility through to user emotional resonance and interactive affordances, creators can more credibly create video information and magnify the translational reach of their messages. For platform operators and policymakers, the scale furnishes a shared standard for quality assurance and for iteratively refining content and promotion algorithms. It specifies empirical criteria for elevating content that scores highly on professionalism and safety, thereby stabilizing the information environment and underpinning sectoral guidelines aimed at curbing misinformation. Additionally, for public-health educators and researchers, the scale operates as a standardized instrument for evidence-based curation and for executing large-scale empirical design of the digital-health media landscape. Applied in practice, the instrument can steer the design of targeted public-health interventions and dissemination strategies. Taken together, these uses advance a multi-stakeholder, system-level approach to improving systematically the quality and effectiveness of digital health communication within today’s media ecology.

Research limitations and perspectives

The chief limitation of this study concerns the representativeness of its sampling frame. Empirical evidence was drawn mainly from residents of China’s second- and third-tier municipalities. As a result, perspectives from first-tier megacities and extensive rural constituencies are underrepresented—contexts in which media-use ecologies, health-information access, and health-literacy profiles plausibly differ substantially. Future studies should undertake multi-site, demographically diverse sampling to re-examine the scale’s properties and strengthen external validity and generalizability. Second, the research design was exclusively quantitative. While appropriate for building a psychometrically reliable instrument, this strategy obscures the subtleties of user experience in specific scenarios. Accordingly, subsequent inquiries would benefit from a mixed-methods design that integrates the current scale with targeted qualitative exploration. Finally, instrument development and validation were conducted within a specifically Chinese cultural milieu. The instrument’s cross-cultural applicability remains empirically unresolved. Future research should adapt and revalidate the instrument across varied cultural contexts to assess its global utility.

Conclusion

This study targets a long-standing lacuna in health communication by constructing and validating a purpose-built, comprehensive scale for evaluating health science popularity in short videos. Research indicates that the quality of health science popularization short videos is structured along 7 principal dimensions and 22 indicators—spanning safety, professionalism, practicality, emotional appeal, content integrity, visual presentation, and interactivity. Taken in the round, the research result yields a more rigorous, standardized evaluative rubric for effectiveness—and, no less importantly, delineates implementable levers through which creators, platform operators, and regulators can lift video quality and deepen user engagement. Accordingly, the validated instrument functions as a cornerstone for systematic quality assurance, a spur to content innovation, and an anchor for digital health-education benchmarks—thereby advancing public-health literacy and amplifying the beneficial reach of online health information in today’s digital environment.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author KT, MTcwMjIyNjYzQHFxLmNvbQ==.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shanxi Bethune Hospital with reference number: YXLL-2022-021. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

WX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft. KT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. LH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Basic Research Plan Project in Shanxi Province from Shanxi Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant number: 202103021223417).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff who participated in this study and the authors who contributed to this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Li, B, Liu, M, Liu, J, Zhang, Y, Yang, W, and Xie, L. Quality assessment of health science-related short videos on TikTok: a scoping review. Int J Med Inform. (2024) 186:105426. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105426

2. Kemp, S. (2023). Digital 2023: global overview report. DataReportal. 2023; we are Social & Meltwater. Available online at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-reportdatareportal.com (Accessed January 26, 2023).

3. Comp, G, Dyer, S, and Gottlieb, M. Is TikTok the next social media frontier for medicine? AEM Educ Train. (2020) 5:10–1002. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10532

4. Kirkpatrick, CE, and Lawrie, LRL. Can videos on TikTok improve pap smear attitudes and intentions? Effects of source and autonomy support in short-form health videos. Health Commun. (2024) 39:2066–78. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2023.2254962

5. Song, S, Xue, X, Zhao, YC, Li, J, Zhu, Q, and Zhao, M. Short-video apps as a health information source for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: information quality assessment of TikTok videos. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e28318. doi: 10.2196/28318

6. Fitzpatrick, PJ. Improving health literacy using the power of digital communications to achieve better health outcomes for patients and practitioners. Front Digit Health. (2023) 5:1264780. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1264780

7. Kirkpatrick, CE, and Lawrie, LRL. TikTok as a source of health information and misinformation for young women in the United States: survey study. JMIR Infodemiol. (2024) 4:e54663. doi: 10.2196/54663

8. Sharevski, F, Vander Loop, J, Jachim, P, Devine, A, and Das, S. 'Debunk-it-yourself': health professionals strategies for responding to misinformation on TikTok. Proc New Secur Paradigms Workshop. (2024):35–55. doi: 10.1145/3703465.3703469

9. Health China New Media Platform Work Committee. Health education video insight report. 2019; internet health China conference. Beijing: (2019).

10. Ziebland, SUE, and Wyke, S. Health and illness in a connected world: how might sharing experiences on the internet affect people's health? Milbank Q. (2012) 90:219–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00662.x

11. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. (2022). Guidance on establishing a comprehensive media mechanism for disseminating health science knowledge. Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/s3581/202205/1c67c12c86b44fd2afb8e424a2477091.shtml.2022-5-31 (Accessed May 31, 2022).

12. Zheng, DX, Ning, AY, Levoska, MA, Xiang, L, Wong, C, and Scott, JF. Acne and social media: a cross-sectional study of content quality on TikTok. Pediatr Dermatol. (2021) 38:336–8. doi: 10.1111/pde.14471

13. Wang, R, He, Y, Xu, J, and Zhang, H. Fake news or bad news? Toward an emotion-driven cognitive dissonance model of misinformation diffusion. Asian J Commun. (2020) 30:317–42. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2020.1811737

14. Walter, N, Brooks, JJ, Saucier, CJ, and Suresh, S. We are evaluating the impact of attempts to correct health misinformation on social media: a meta-analysis. Health Commun. (2021) 36:1776–84. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1794553

15. Alvarez-Galvez, J, Suarez-Lledo, V, and Rojas-Garcia, A. Determinants of infodemics during disease outbreaks: a systematic review. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:603603. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.603603

16. Suarez-Lledo, V, and Alvarez-Galvez, J. Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e17187. doi: 10.2196/17187

17. Morahan-Martin, JM. How internet users find, evaluate, and use online health information: a cross-cultural review. CyberPsychol Behav. (2004) 7:497–510. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.497

18. Gabarron, E, Fernandez-Luque, L, Armayones, M, and Lau, AY. We are identifying measures for assessing the quality of YouTube videos with patient health information: a review of current literature—interactive. J Med Res. (2013) 2:e2465. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.2465

19. Adam, M, McMahon, SA, Prober, C, and Bärnighausen, T. Human-centered design of video-based health education: an iterative, collaborative, community-based approach. J Med Internet Res. (2019) 21:e12128. doi: 10.2196/12128

20. Brox, E, Fernandez-Luque, L, and Tøllefsen, T. Healthy gaming–a video game designed to promote health. Appl Clin Inform. (2011) 2:128–42. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2010-10-R-0060

21. Kong, W, Song, S, Zhao, YC, Zhu, Q, and Sha, L. TikTok as a health information source: assessment of the quality of information in diabetes-related videos. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e30409. doi: 10.2196/30409

22. Vasistha, S, Kanchibhatla, A, Blanchette, JE, Rieke, J, and Hughes, AS. The sugar-coated truth: the quality of diabetes health information on TikTok. Clin Diabetes. (2025) 43:53–8. doi: 10.2337/cd24-0042

23. Bulut, M, Reyhan, AH, and Reyhan, AH. A quality assessment of YouTube videos on Chalazia: implications for patient education and healthcare professional involvement. Cureus. (2025) 17:e78043. doi: 10.7759/cureus.78043

24. Khalil, M, Mohamed, F, and Shoufan, A. Evaluating the quality of medical content on YouTube using large language models. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:9906. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-94208-6

25. Zhang, Y, Sun, Y, and Xie, B. Quality of health information for consumers on the web: a systematic review of indicators, criteria, tools, and evaluation results. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. (2015) 66:2071–84. doi: 10.1002/asi.23311

26. Kress, GR, and Van Leeuwen, T. Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Arnold (2001).

28. Xiao, L, Min, H, Wu, Y, Zhang, J, Ning, Y, Long, L, et al. Public’s preferences for health science popularization short videos in China: a discrete choice experiment. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1160629. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1160629

29. Eysenbach, G, Powell, J, Kuss, O, and Sa, ER. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the world wide web: a systematic review. JAMA. (2002) 287:2691–700. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2691

30. Sun, Y, Zhang, Y, Gwizdka, J, and Trace, CB. Consumer evaluation of the quality of online health information: a systematic literature review of relevant criteria and indicators. J Med Internet Res. (2019) 21:e12522. doi: 10.2196/12522

31. Nutbeam, D, and Lloyd, JE. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. (2021) 42:159–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529

32. Zhu, H, Wei, H, and Wei, J. Understanding users’ information dissemination behaviors on Douyin, a short video mobile application in China. Multimed Tools Appl. (2023) 83:58225–43. doi: 10.1007/s11042-023-17831-3

33. Tian, K, Hao, L, Xuan, W, Phongsatha, T, Hao, R, and Wei, W. The impact of perceived value and affection on Chinese residents' continuous use intention of mobile health science information: an empirical study—frontiers in public. Health. (2023) 11:1034231. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1034231

34. Zhang, X, Liu, S, Chen, X, Wang, L, Gao, B, and Zhu, Q. Health information privacy concerns, antecedents, and information disclosure intention in online health communities. Inf Manag. (2018) 55:482–93. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2017.11.003

35. Wendy Nga Man, W, Samuel Kai Wah, C, Hong, H, and Miu Yan, H. Cross-cultural quality comparison of online health information for elderly care on yahoo! Answers. Proc Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. (2014) 51:1–10. doi: 10.1002/meet.2014.14505101055

36. Tao, D, LeRouge, C, Smith, KJ, and De Leo, G. Defining information quality into health websites: a conceptual framework for information quality for educated young adults. JMIR Hum Factors. (2017) 4:e6455. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.6455

37. Bezemer, J, and Kress, G. Multimodality, learning and communication: A social semiotic frame Routledge (2015).

38. O'Halloran, K, and Smith, BA. Multimodal studies: Exploring issues and domains Routledge (2012).

39. Langford, A, and Loeb, S. Perceived patient-provider communication quality and sociodemographic factors associated with watching health-related videos on YouTube: a cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2019) 21:e13512. doi: 10.2196/13512

40. Churchill, GA, and Iacobucci, D. Marketing research: Methodological foundations. New York: Dryden Press (2006).

41. Ohanian, R. The impact of celebrity spokespersons' perceived image on consumer's intention to purchase. J Advert Res. (1991) 31:46–54. doi: 10.1080/00218499.1991.12466759

42. Zhu, DH, Chang, YP, and Luo, JJ. Understanding the influence of C2C communication on purchase decision in online communities from a perspective of information adoption model. Telematics Inform. (2016) 33:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2015.06.001

43. Bhattacharjee, A, and Sanford, C. Influence processes for information technology acceptance: an elaboration likelihood model. MIS Q. (2006) 30:805–25. doi: 10.2307/25148755

44. Lin, HH, and Wang, YS. An examination of the determinants of customer loyalty in mobile commerce contexts. Inf Manag. (2006) 43:271–82. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2005.08.001

45. Tang, XL, Zhang, B, and Zhang, Y. Explore users’ information adoption intention in online health communities: a health literacy and trust perspective. J Inform Resour Manag. (2024) 8:102–12. doi: 10.13365/jj.irm.2018.03.102

46. Liu, Y. Developing a scale to measure the interactivity of websites. J Advert Res. (2003) 43:207–16. doi: 10.2501/jar-43-2-207-216

47. Son, JY, and Kim, SS. Internet users' information privacy-protective responses: a taxonomy and a nomological model. MIS Q. (2008) 32:503–29. doi: 10.2307/25148854

48. Tian, XH, Bi, XH, Yang, YH, and Tang, XJ. The inverted U-shape relationship between personalized recommendation and intention to use short video. J Modern Inform. (2024) 44:81–92. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0821.2024.03.008

49. Johnson, DS, and Lowe, B. Emotional support, perceived corporate ownership, and skepticism toward out-groups in virtual communities. J Interact Mark. (2015) 29:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2014.07.002

50. Cavallo, DN, Brown, JD, Tate, DF, DeVellis, RF, Zimmer, C, and Ammerman, AS. The role of companionship, esteem, and informational support in explaining physical activity among young women in an online social network intervention. J Behav Med. (2014) 37:955–66. doi: 10.1007/s10865013-9534-5

51. Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory. Psychology of learning and motivation. Academic Press, (2011). 37–76.

52. Lakey, B, and Cohen, S. Social support theory and measurement. Soc Support Measur Intervent. (2000) 2952:2. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780195126709.003.0002

53. Rosenstock, IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. (1974) 2:328–35. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200403

54. Tongprasert, S, Rapipong, J, and Buntragulpoontawee, M. The cross-cultural adaptation of the DASH questionnaire in Thai (DASH-TH). J Hand Ther. (2014) 27:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2013.08.020

55. Tan, M, and Teo, TS. Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking. J Assoc Inf Syst. (2000) 1:1–44. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00005

56. Chen, L, Mu, T, Li, X, and Dong, J. Population prediction of Chinese prefecture-level cities based on multiplemodels. Sustainability. (2022) 14:4844. doi: 10.3390/su14084844

57. Hair, JF Jr, Hult, GTM, Ringle, CM, Sarstedt, M, Danks, NP, and Ray, S. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook Springer Nature (2021).

58. MacCallum, RC, Browne, MW, and Sugawara, HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. (1996) 1:130–49. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

60. Lloret-Segura, S, Ferreres-Traver, A, Hernandez-Baeza, A, and Tomas-Marco, I. Exploratory item factor analysis: a practical guide revised and updated. Anales de psicología. (2014) 30:1151–69. doi: 10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361

61. Churchill, GA Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J Mark Res. (1979) 16:64–73. doi: 10.1177/002224377901600110

62. Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., and Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective: 7.

64. Bagozzi, RP, and Kimmel, SK. A comparison of leading theories for the prediction of goal-directed behaviors. Br J Soc Psychol. (1995) 34:437–61. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01076.x

65. Bailey, R, and Ball, S. An exploration of the meanings of hotel brand equity. Serv Ind J. (2006) 26:15–38. doi: 10.1080/02642060500358761

66. Fornell, C, and Larcker, DF. I am evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement errors. J Mark Res. (1981) 18:39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

67. Tull, DS, and Hawkins, DI. Marketing research: measurement and method: a text with cases. NewYork, NY: Macmillan (1980).

68. Lin, B, Chen, Y, and Zhang, L. Research on the factors influencing the re-purchase intention on short video platforms: a case of China. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0265090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265090

69. Yang, Q, and Lee, YC. What drives mobile short-form video shop's digital customer experience and customer loyalty? Evidence from douyin (TikTok). Sustainability. (2022) 14:10890. doi: 10.3390/su141710890

70. Gu, C, Lin, S, Sun, J, Yang, C, Chen, J, Jiang, Q, et al. What do users care about? Research on user behavior of mobile interactive video advertising. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e10910. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10910

71. Kim, AJ, and Johnson, KK. Power of consumers using social media: examining the influences of brand-related user-generated content on Facebook. Comput Hum Behav. (2016) 58:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.047

72. Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. (2000) 15:259–67. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259

73. Xuan, W, Phongsatha, T, Hao, L, and Tian, K. Impact of health science popularization videos on user perceived value and continuous usage intention: based on the CAC and ECM model framework. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1382687. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1382687

74. Dang, Q, Luo, Z, Ouyang, C, and Wang, L. First systematic review on health communication using the CiteSpace software in China: exploring its research hotspots and frontiers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:13008. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413008

75. Huang, L, Dong, X, Yuan, H, and Wang, L. Enabling and inhibiting factors of the continuous use of mobile short video APP: satisfaction and fatigue as mediating variables, respectively. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2023) 16:3001–17. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S411337

Keywords: health science popularization short videos, short video quality, scale development, scale validation, multimodal theory, exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis

Citation: Xuan W, Tian K and Hao L (2025) Quality assessment of short videos on health science popularization in China: scale development and validation. Front. Public Health. 13:1640105. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1640105

Edited by:

Lei Shi, Guangzhou Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Limei Jing, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaAnne Namatsi Lutomia, Purdue University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Xuan, Tian and Hao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenxia Xuan, eHVhbndlbnhpYUBzeGJxZWguY29tLmNu; Kun Tian, MTcwMjIyNjYzQHFxLmNvbQ==

Wenxia Xuan

Wenxia Xuan Kun Tian

Kun Tian Lijie Hao

Lijie Hao