- 1Alameda Health System, Oakland, CA, United States

- 2Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, United States

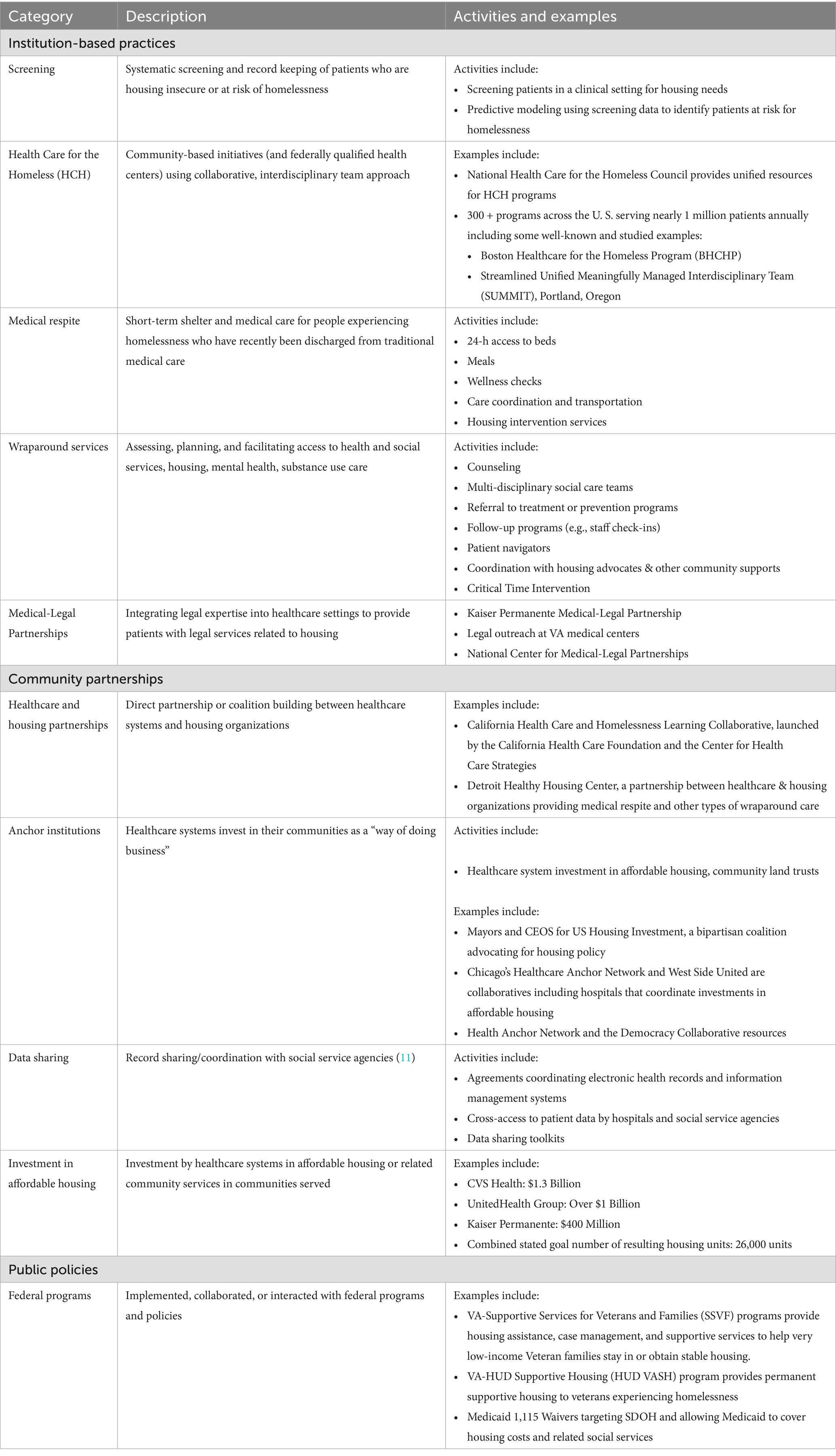

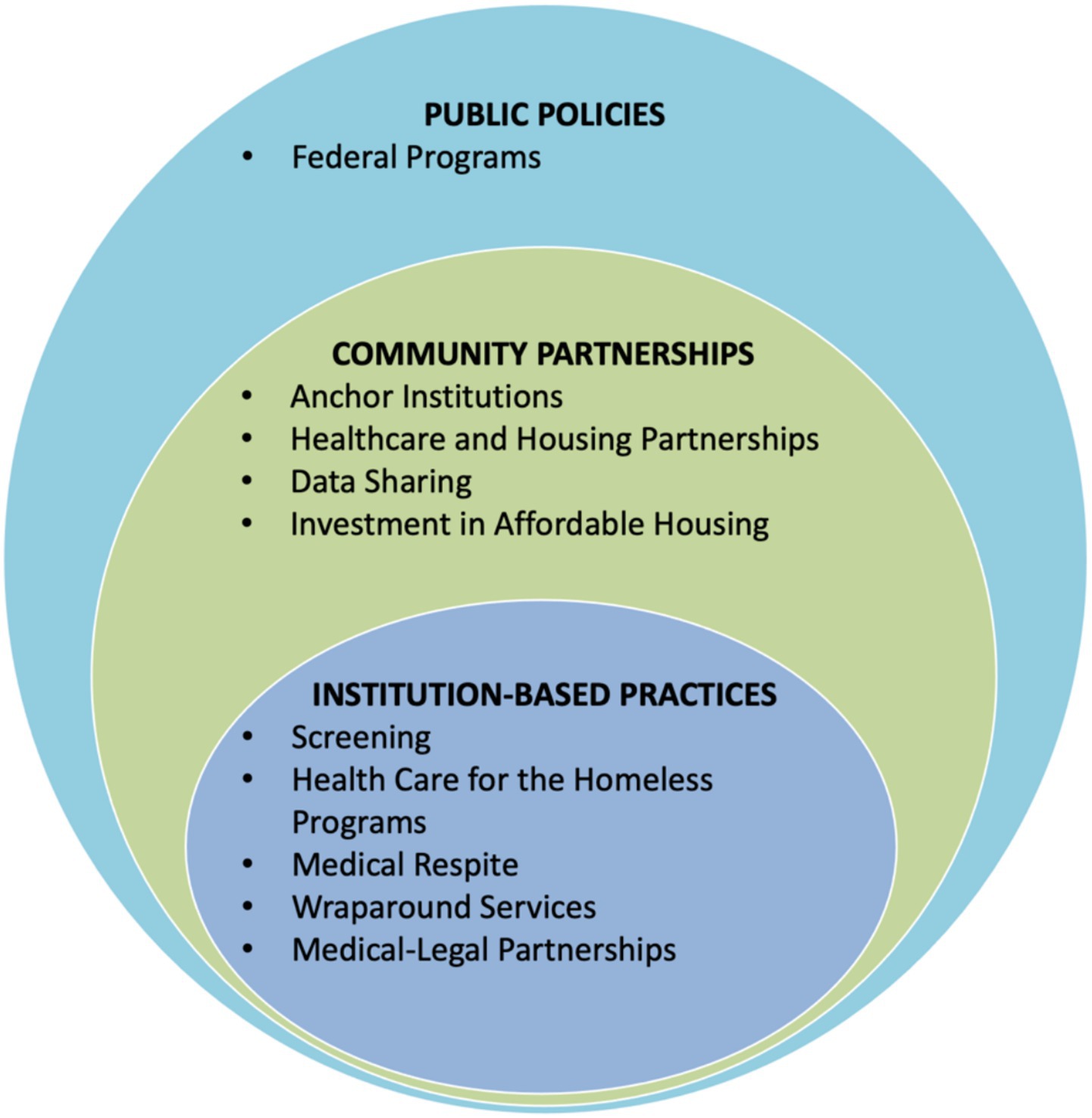

While healthcare systems have long attempted various strategies to care for unhoused patients, the rising complexity and severity of the homelessness crisis have underscored the urgent need for systemic approaches. Such efforts are critical as current federal policies push more responsibility for homelessness prevention and response to states and localities. Few studies have identified frameworks that healthcare systems can use to guide unified responses to the homelessness. In particular, support is needed to address how healthcare systems can operate across levels beyond individual care to improve patient health. To assess current and potential best practices, we conducted a literature search on healthcare system involvement in homelessness and conducted key informant interviews with experts from healthcare systems and national and local homelessness organizations. We grouped a wide spectrum of health-system responses into ten categories: screening, Health Care for the Homeless programs, medical respite, wraparound services, medical-legal partnerships, investment in affordable housing, healthcare and housing partnerships, data sharing, anchor institutions, and implementation of federal programs. Drawing on the socioecological model, this typology provides a framework that presents the ten categories for homelessness interventions on three interconnected levels—institution-based practices, community partnerships, and public policy. It also provides a foundation for further research, financial impact analysis, and program evaluation.

Introduction

Homelessness is an acute public health and humanitarian crisis in the United States, yet overall response from healthcare systems nationwide has been fragmented. While dedicated healthcare professionals have, over decades, offered street outreach and related services to unhoused people, the complexity and severity of the crisis now demands that all hospital and health systems adopt more systematic approaches to care, treatment, and prevention (1, 2).

Multiple factors drive this need. First, homelessness has increased; 2024 point-in-time count numbers are at their highest levels since national tracking started in 2007 (3). Those affected endure severe health inequities, as exemplified by a Massachusetts study finding all-cause mortality rates for people experiencing homelessness up to 10 times that of the general population (4). The heightened risk is driven by high burdens of chronic conditions (e.g., heart disease and cancer), infectious diseases (e.g., TB, HIV, chronic hepatitis), and mental health and substance use disorders (5–11). Second, rates of hospitalization and emergency department (ED) visits for unhoused patients greatly exceed those of the general population (12, 13). Third, healthcare systems increasingly recognize the urgency of addressing housing insecurity and other social determinants of health (SDOH) while also searching for potential cost savings (1, 14, 15).

Several recent articles document evolving healthcare system strategies to address housing insecurity and homelessness for their patients. In 2020, one of us (HK) co-authored an analysis of health-related anchor institutions, focusing on the commitment of some healthcare systems to address housing and other SDOH as part of their business strategy (16). In 2024, Garcia et al. analyzed specific hospital and health system interventions, including medical respite, screening for social needs, Housing First initiatives, and financing innovations (1). A 2025 study noted that over half of the 100 largest US health systems have some level of homelessness mitigation programs that include, for example, housing, shelter-based medical care, and coordinated services (14). Meanwhile, national non-profits working on homelessness have coordinated with healthcare systems in multiple communities (17, 18).

In 2024, the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) released federal guidance for hospitals and healthcare systems (authored by JCL and JO). The guidance offers six best practice strategies, including delivering care outside traditional medical facilities, partnering with non-health organizations, improving data systems and data sharing on housing and homelessness, promoting supportive and affordable housing, preventing homelessness, and advancing health equity (2). Less than a year later, however, a new presidential administration has ushered in uncertainty regarding the future of federal homelessness policy (19). It is already clear that responsibility to address the homelessness crisis will fall more heavily on states and localities.

This article offers, to our knowledge, the first framework for how healthcare systems can respond comprehensively to the homelessness crisis. Based on the best publicly available data, it offers a vision of how health care organizations can employ a broad array of strategies and interventions to identify levels of engagement and unify diverse approaches. The framework can also help organize future research efforts for evaluation.

Methods

To identify the most promising interventions, we first identified relevant articles in the peer-reviewed literature. Using individual search terms and combinations of terms (e.g., “housing instability,” “homelessness,” “healthcare systems,” “hospitals,” “housing first,” “affordable housing”), two reviewers (JL and CR) searched databases including PubMed, Google Scholar, Policy File, Policy Commons, and Think Tank Search for published articles (January 2000–March 2025) relating to any healthcare system’s activity addressing homelessness. We then conducted extensive internet searches of the substantial “grey literature” outside of academic databases, employing key items like “homelessness” and “health care systems” and “housing first” and “affordable housing.” that described American healthcare organizations engaged in activities related to homelessness. Finally, we also conducted 12 key informant interviews with recognized healthcare leaders and local and government partners across the country on perceived reasons for involvement, best practices, and potential areas for increased involvement in addressing homelessness. The 30-min interviews deployed a semi-structured interview guide using snowball sampling.

Synthesizing over 180 items from the white and grey literature as well as information from key informant interviews, we grouped each item into at least one of ten categories (Table 1). The categories represent the building blocks of a broader three-level framework of health system involvement (Figure 1).

Results

Based on results from the literature reviews and key informant interviews, we developed a framework through which hospitals and healthcare systems can create a more unified and comprehensive response to homelessness. Building on the socioecological model, the framework presented in Figure 1 encourages coordinated change at three levels—institution-based practices, community partnerships, and public policy (20). By highlighting the inherent links between these layers, this framework illustrates how healthcare systems can operate across levels beyond individual care to improve patient health. It gives health care systems a blueprint for building a comprehensive response, starting with activities closest to the central activity of patient care and then expanding outward to organizational collaboration (institutions and communities) and policy change.

Institution-based practices

We identified various forms of team-based practices that hospitals and other healthcare systems have used to address homelessness. With the addition of data linking each intervention to specific health or housing outcomes, these represent initial steps healthcare systems can use to build a comprehensive response to homelessness.

Screening

Some healthcare systems have used screening protocols to identify patients who are housing insecure or homeless and provide them with necessary support and services. At present, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has had the most experience with developing, and testing a standardized instrument—the Homelessness Screening Clinical Tool—that identifies veteran families experiencing housing instability and at risk of homelessness (21, 22). Montgomery et al. found that when the VA’s national Homelessness Screening Clinical Reminder launched, between October 1, 2012 and January 10, 2013, 1,422,038 veterans were presented with the screener, with 2.1% of viable respondents screening “positively” for a risk of homelessness (21). Since then, Byrne et al. tested predictive modeling using medical record data to further hone the VA screener process (22). At the community level, Houston’s Ben Taub Hospital has screened for, and flagged, heavy emergency department utilizers to help address social, including housing, need, connecting identified patients with community organizations and community health workers or social workers prior to discharge (23).

Legislation in California in 2019 prompted hospitals to screen patients for homelessness, keep records of discharge planning, and offer food, clothing, and appropriate referrals (24). After this legislative change, qualitative studies found that staff reported increased consistency in documentation and service delivery—although they also expressed concerns regarding accuracy and insufficient availability of resources to respond to patient needs (25–27). Patients have generally responded positively to being asked about housing in the ED, even if many had not initially considered the ED a place to receive help with housing (28).

Health Care for the Homeless (HCH)

Established in 1985, the HCH program involves a collaborative, interdisciplinary team-based approach for patients experiencing homelessness. The National Healthcare for the Homeless Council (NHCHC), founded in 1986, coordinates, convenes, and supports HCH projects across the country, which today number over 300 sites serving 940,000 patients each year (29).

In one example, the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) provides essential services for 11,000 + individuals in settings including street medicine, primary care, subspecialty care, and post-acute care. A recent study found that adding patient navigators to standard-of-care lung cancer screening for BHCHP patients increased low-dose CT scans 4.7-fold (30). Similarly, a randomized controlled study involving SUMMIT, the Streamlined Unified Meaningfully Managed Interdisciplinary Team, a federally qualified health center team in Portland, Oregon, found that interdisciplinary team care increased primary care use and improved patient wellbeing, although it did not meaningfully change hospital or ED use (31, 32). Shared decision-making, continuity of care, integration of social services, and services that reach beyond traditional primary care clinics positively impact patient experience (33, 34). Many HCHs remain free-standing programs that could have broader impact through closer collaboration with hospitals and health systems (35).

Medical respite

Some healthcare systems offer short-term housing and medical care for unhoused patients too ill to be on the streets or in traditional shelters but not ill enough to require hospitalization. It bridges the gap between hospital care and shelters or provide recovery space for unsheltered people such programs could reduce future hospital admissions, readmissions, and inpatient days (36–39). Facility type varies from transitional housing to standalone facilities; common features include 24-h access to beds, three daily meals, wellness checks, care coordination, and transportation to medical appointments (40). BHCHP opened the first medical respite facility in 1985 which currently includes over 100 beds (41). Today, there are over 150 medical respite sites in the U.S (1).

Multiple studies demonstrate cost savings from medical respite programs, with average daily expenses an estimated $2,282 less per day than inpatient hospital care (42, 43). A randomized study at two large Chicago hospitals involving 470 adults with chronic diseases, two respite sites, and 10 housing agencies, found patients connected to medical respite (through hospital case managers) used the ED 24% less than other patients experiencing homelessness (44). Doran et al. also associated medical respite with improved housing outcomes, health status, and access to primary care (45).

Wraparound services

These services typically facilitate access to health and social services commonly centered on housing, mental health, and substance use (46, 47). Interventions are varied and include different models of case management [standard, intensive, clinical, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), and Critical Time Intervention (CTI)], housing navigation, and care coordination. Preliminary evidence suggests that such wraparound services can decrease hospital days and ED visits, benefit housing stability, ameliorate drug and alcohol use disorders, and reduce days of homelessness (44, 48, 49).

Critical Time Intervention (CTI) is a time-limited case management model that provides support during challenging life transitions, including from a hospital into the community. A systematic review of CTI found positive impacts on housing and service engagement use outcomes (50). One randomized trial of family CTI for mothers experiencing homelessness found those who received CTI were more likely to be rapidly rehoused compared to those receiving usual services (51).

Medical-legal partnerships (MLPs)

MLPs integrate legal expertise into medical settings by embedding lawyers into healthcare teams to provide patients with legal services related to housing, landlord-tenant disputes, evictions, and discrimination (52). Funding generally comes from healthcare organizations, philanthropy, and legal volunteers (53). A VA study showed that participants’ legal goals were achieved in 712 out of 1,384 issues raised one such MLP (54). Veterans whose legal needs were addressed had significantly fewer symptoms of hostility, paranoia, and generalized anxiety disorder, and social outcomes—including housing status (54). However, one study noted that of 48 homeless service sites across 48 states, only 10% had MLPs despite the fact that 90% reported that their patients had civil legal needs (55).

Community partnerships

Beyond providing direct care, individual hospitals and health systems have addressed homelessness by forming partnerships with other organizations in their communities. There remains a pressing need for additional data on their effects on patient care and best partnership practices.

Healthcare and housing partnerships

Several promising examples of direct partnership and building coalitions can align healthcare systems and the Continuum of Care — locally or regionally organized groups that coordinate housing and services for people experiencing homelessness. The California Health Care and Homelessness Learning Collaborative (launched in 2022) promotes cross-sector collaboration between the California Health Care Foundation and the Center for Health Care Strategies (56). In Detroit, Michigan, an integrated health and social services agency partnered with nonprofit, healthcare partners, and housing organizations (2023) to form the “Detroit Healthy Housing Center,” offering medical respite beds to 165 patients experiencing homelessness annually (57). In 2020, non-profit organizations Community Solutions and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched a health care and homelessness pilot that unified major health systems in five US communities: Kaiser Permanente (KP), Providence Health, Common Spirit, Sutter Health, and U.C. Davis Health (58). These organizations engage in cross-sector case conferencing, coordinating post-discharge care, and sharing data between healthcare and housing systems (59).

Data sharing

Hospitals and healthcare systems can unify patient care for unhoused patients by sharing data with social service agencies. In Washington County, Oregon, and Sacramento County California, numerous organizations, including KP have entered data sharing agreements across the medical system and social services continuum of care. The aim is to ensure that EHRs and the Homeless Information Management System (HMIS) collect similar data and that hospital navigators have access to HMIS systems (60). Community Solutions has developed a data sharing toolkit based on these pilot projects (60).

Anchor institutions

Some hospitals and health systems have committed to addressing SDOH, including housing insecurity, as part of their business mission. Such “anchor institutions” are major, place-based health institutions that commit significant financial, human, and intellectual resources to addressing social challenges. Anchor medical institutions may, for example, invest in affordable housing and community land trusts (16). Nonprofit hospitals can achieve federal, and often state, tax-exempt status by assessing community health needs and ensuring community engagement in strategies targeting social needs like housing.

As part of their anchor strategy, KP joined a bipartisan advocacy coalition—Mayors and CEOS for US Housing Investment—to advocate for housing policy (16, 61). Rush University in Chicago similarly joined the think tank Democracy Collaborative and the Civic Consulting Alliance in 2017 to develop the Healthcare Anchor Network, a national collaboration of over 75 healthcare systems investing in affordable housing in local communities (62). In 2018, Rush joined with five other hospitals to develop the West Side United collaborative focused on racial equity and coordinating affordable housing investments (62).

Investment in affordable housing

Healthcare systems directly invest into local housing markets. A 2020 study estimated that healthcare systems spent $1.6 billion (from 2017 to 2019) on housing-focused interventions, including affordable housing (15). The largest investors appear to be CVS Health (over $1.3 billion), UnitedHealth Group (over $800 million), and KP ($400 million) with a stated overall goal of over 26,000 new housing units across the country, including 7,000 new housing units over the last 5 years (63–65). These investments should be evaluated further by researchers and public health practitioners through analysis of publicly available impact data.

Public policies

Healthcare systems have implemented, collaborated on, or interacted with federal programs and policies to increase affordable housing and related needs. For example, in 1992, the VA partnered with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to establish the HUD-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program, providing veterans rental subsidy vouchers, case management, and other wraparound services. A 2003 randomized control study found that HUD-VASH veterans, compared to those receiving case management only or standard care, had 16 and 25% more days housed, respectively (66). HUD-VASH expanded dramatically after 2008, and has been linked to reducing veteran homelessness by 55% (67, 68). The VA’s related Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) program has been used to rapidly rehouse not only veterans but also their families, often through partnerships with community-based non-profit organizations (69).

Through Medicaid, states have had the opportunity to submit 1,115 waivers, giving them flexibility for states to reimburse for costs related to housing support and other health-related social services (not exceeding 3% of total annual Medicaid spending) (70). Most waivers were narrow in scope until the 1990s, but have since expanded and now nearly one-third target homelessness (14, 71, 72). One such pilot program in North Carolina reduced overall Medicaid spending as a result of the waiver (73).

Other comprehensive responses

The nation has seen some examples of comprehensive responses to homelessness through healthcare systems. The most prominent ones relate to the VA through HUD-VASH and SSVF, as noted above. Outside the VA, the Harris Health System, a Texas safety-net provider serving approximately 4.7 million patients offers wraparound services for unhoused patients who frequently use EDs. Harris also partners with the Coalition for the Homeless of Houston/Harris County and community service agencies to coordinate care and provide emergency housing assistance (74). KP, an integrated healthcare system serving over 12 million patients in eight states (and the District of Columbia), has over the last decade invested in medical respite and medical-legal partnerships. Efforts include a 2021 launch of medical-legal partnerships with five medical centers across four states, with 330 closed cases during 2022–2023, 91 of them related to housing and/or utilities (75). And as noted above, KP has also joined coalition partnerships focused on housing and invested over $400 million in affordable housing (16, 61, 65).

Conclusion

This article offers a vision for a more strategic and comprehensive approach to caring for people experiencing homelessness. In particular, it offers healthcare systems ways to operate across levels beyond individual care to improve patient health. Our multi-level intervention framework rooted in the socioecological model synthesizes existing practices into a blueprint versatile enough for application across locations, policy landscapes, and healthcare systems. The framework organizes an array of concrete opportunities for hospitals and healthcare systems to expand their role as population-health change agents at a time when federal and many state governments are stepping back from commitments to addressing housing and other SDOH.

The framework also builds upon and formalizes the previous federal guidance from USICH, offering a roadmap for hospitals and health systems to operationalize it. While we offer here a consolidation of diverse actions into one framework, relatively few services have been rigorously evaluated. As more healthcare systems engage in this work, they should generate rigorous, publicly available research on health and housing outcomes. Specific pressing and high-yield questions include: What is the return on investment for monetary commitment in affordable housing? Are there significant differences in housing outcomes after establishing healthcare and housing partnerships? What is the best way to measure and monitor outcomes? How can individual care interventions be designed to improve specific health outcomes? Since this article was informed by an initial review of current literature, we encourage a more detailed systematic review on the literature and its quality.

Healthcare researchers, policymakers, and leaders are well-positioned to begin answering these questions, as well as to create guidelines, toolkits, and other resources for continued development and learning. Further commitment will be critical to ensure a future society where no patient experiences the tragedy of homelessness.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

JL: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft. CR: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Formal analysis, Methodology. JO: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. EL: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. HK: Formal analysis, Supervision, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Garcia, C, Doran, K, and Kushel, M. Homelessness and health: factors, evidence, innovations that work, and policy recommendations. Health Aff (Millwood). (2024) 43:164–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01049

2. United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. USICH releases guidance for health systems and hospitals. (2024). Available online at: https://usich.gov/news-events/news/usich-releases-guidance-health-systems-and-hospitals (Accessed May 16, 2024).

3. Tanya, S, and Meghan, H. The 2024 annual homelessness assessment report (AHAR to congress) part 1: point-in-time estimates of homelessness, December 2024. Available online at: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2024-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

4. Roncarati, JS, Baggett, TP, O’Connell, JJ, Hwang, SW, Cook, EF, Krieger, N, et al. Mortality among unsheltered homeless adults in Boston, Massachusetts, 2000-2009. JAMA Intern Med. (2018) 178:1242–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2924

5. Funk, AM, Greene, RN, Dill, K, and Valvassori, P. The impact of homelessness on mortality of individuals living in the United States: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2022) 33:457–77. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2022.0035

6. Mosites, E, Lobelo, EE, Hughes, L, and Butler, JC. Public health and homelessness: a framework. J Infect Dis. (2022) 15:S372–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac353

7. Liu, CY, Chai, SJ, and Watt, JP. Communicable disease among people experiencing homelessness in California. Epidemiol Infect. (2024) 148:e85. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820000722

8. Valenciano, SJ, Onukwube, J, Spiller, MW, Thomas, A, Como-Sabetti, K, Schaffner, W, et al. Invasive group a streptococcal infections among people who inject drugs and people experiencing homelessness in the United States, 2010-2017. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. (2021) 73:e3718–26. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa787

9. Holowatyj, AN, Heath, EI, Pappas, LM, Ruterbusch, JJ, Gorski, DH, Triest, JA, et al. The epidemiology of Cancer among homeless adults in metropolitan Detroit. JNCI Cancer Spectr. (2019) 3:pkz006. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkz006

10. Manhapra, A, Stefanovics, E, and Rosenheck, R. The association of opioid use disorder and homelessness nationally in the veterans health administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2021) 223:108714. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108714

11. Barry, R, Anderson, J, Tran, L, Bahji, A, Dimitropoulos, G, Ghosh, SM, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among individuals experiencing homelessness: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. (2024) 81:691–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0426

12. Hwang, SW, Chambers, C, Chiu, S, Katic, M, Kiss, A, Redelmeier, DA, et al. A comprehensive assessment of health care utilization among homeless adults under a system of universal health insurance. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:S294–301. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301369

13. Kushel, MB, Perry, S, Bangsberg, D, Clark, R, and Moss, AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. (2002) 92:778–84. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.778

14. Willison, CE, Unwala, NA, and Klasa, K. Entrenched opportunity: Medicaid, health systems, and solutions to homelessness. J Health Polit Policy Law. (2025) 50:307–36. doi: 10.1215/03616878-11567700

15. Horwitz, LI, Chang, C, Arcilla, HN, and Knickman, JR. Quantifying health systems’ investment in social determinants of health, by sector, 2017–19. Health Aff Millwood. (2020) 39:192–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01246

16. Koh, HK, Bantham, A, Geller, AC, Rukavina, MA, Emmons, KM, Yatsko, P, et al. Anchor institutions: best practices to address social needs and social determinants of health. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:309–16. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305472

17. Anna, GHealth Care Is Key to Coordinating Homelessness Solutions. Community solutions. (2022). Available online at: https://community.solutions/case-studies/health-care-is-key-to-coordinating-homelessness-solutions/

18. HCH Clinicians’ Network. National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (2019). Available online at: https://nhchc.org/clinical-practice/hch-clinicians-network/

19. Ludden, J. Trump administration has gutted an agency that coordinates homelessness policy. NPR (2025); Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2025/04/16/nx-s1-5366865/trump-doge-homelessness-veterans-interagency-council-on-homelessness-staff-doge

20. Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. (1977) 32:513–31. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

21. Montgomery, AE, Fargo, JD, Byrne, TH, Kane, VR, and Culhane, DP. Universal screening for homelessness and risk for homelessness in the veterans health administration. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:S210–1. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301398

22. Byrne, T, Montgomery, AE, and Fargo, JD. Predictive modeling of housing instability and homelessness in the veterans health administration. Health Serv Res. (2019) 54:75–85. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13050

23. Tuller, D. A new way to support frequent emergency department visitors. Health Aff (Millwood). (2022) 41:934–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00680

24. SB-1152 Hospital patient discharge process: homeless patients. (2018). Available online at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB1152

25. Taira, BR, Kim, H, Prodigue, KT, Gutierrez-Palominos, L, Aleman, A, Steinberg, L, et al. A mixed methods evaluation of interventions to meet the requirements of California senate bill 1152 in the emergency departments of a public hospital system. Milbank Q. (2022) 100:464–91. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12563

26. Aridomi, H, Cartier, Y, Taira, B, Kim, HH, Yadav, K, and Gottlieb, L. Implementation and impacts of California senate bill 1152 on homeless discharge protocols. West J Emerg Med. (2023) 24:1104–16. doi: 10.5811/WESTJEM.60853

27. McConville, S, Kanzaria, H, Hsia, R, Raven, M, Kushel, M, and Barton, S. How hospital discharge data can inform state homelessness policy. UC Berkeley: California Policy Lab. (2022). Available from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6g18v5xm

28. Kelly, A, Fazio, D, Padgett, D, Ran, Z, Castelblanco, DG, Kumar, D, et al. Patient views on emergency department screening and interventions related to housing. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. (2022) 29:589–97. doi: 10.1111/acem.14442

29. The Health Care for the Homeless Program Fact Sheet. (2021) Available online at: https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/HCH-Fact-Sheet_2021.pdf

30. Baggett, TP, Sporn, N, Barbosa Teixeira, J, Rodriguez, EC, Anandakugan, N, Critchley, N, et al. Patient navigation for lung cancer screening at a health care for the homeless program: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. (2024) 184:892–902. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.1662

31. Chan, B, Edwards, ST, Srikanth, P, Mitchell, M, Devoe, M, Nicolaidis, C, et al. Ambulatory intensive Care for Medically Complex Patients at a health Care Clinic for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness: the SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2023) 6:e2342012. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.42012

32. Chan, B, Hulen, E, Edwards, ST, Geduldig, A, Devoe, M, Nicolaidis, C, et al. Perceptions of medically complex patients enrolled in an ambulatory intensive care unit at a healthcare-for-the-homeless clinic. J Am Board Fam Med. (2025) 37:888–99. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2023.230403R1

33. Kertesz, SG, deRussy, AJ, Hoge, AE, Varley, AL, Holmes, SK, Riggs, KR, et al. Organizational and patient factors associated with positive primary care experiences for veterans with current or recent homelessness. Health Serv Res. (2024) 59:e14359. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14359

34. Ramirez, J, Petruzzi, LJ, Mercer, T, Gulbas, LE, Sebastian, KR, and Jacobs, EA. Understanding the primary health care experiences of individuals who are homeless in non-traditional clinic settings. BMC Prim Care. (2022) 23:338. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01932-3

35. Rabell, L. How to start a health Care for the Homeless Program. National Health Care for the homeless council. (2021). Available online at: https://nhchc.org/how-to-start-a-health-care-for-the-homeless-program/

36. Biederman, DJ, Gamble, J, Wilson, S, Douglas, C, and Feigal, J. Health care utilization following a homeless medical respite pilot program. Public Health Nurs. (2019) 36:296–302. doi: 10.1111/phn.12589

37. Hoang, P, Naeem, I, Grewal, EK, Ghali, W, and Tang, K. Evaluation of the implementation of a medical respite program for persons with lived experience of homelessness. J Soc Distress Homelessness. (2024) 33:425–37. doi: 10.1080/10530789.2023.2229993

38. Biederman, DJ, Gamble, J, Manson, M, and Taylor, D. Assessing the need for a medical respite: perceptions of service providers and homeless persons. J Community Health Nurs. (2014) 31:145–56. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2014.926675

39. Shetler, D, and Shepard, DS. Medical respite for people experiencing homelessness: financial impacts with alternative levels of Medicaid coverage. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2018) 29:801–13. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0059

40. Medical Respite. National Health Care for the homeless council. (2020). Available online at: https://nhchc.org/medical-respite/

41. O’Connell, JJ, Oppenheimer, SC, Judge, CM, Taube, RL, Blanchfield, BB, Swain, SE, et al. The Boston health Care for the Homeless Program: a public health framework. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100:1400–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173609

42. McCarthy, D, and Waugh, L. (2021). How a medical respite care program offers a pathway to health and housing for people experiencing homelessness. Available online at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/case-study/2021/aug/how-medical-respite-care-program-offers-pathway-health-housing

43. Walton, MT, Mackie, J, Todd, D, and Duncan, B. Delivering the right care, at the right time, in the right place, from the right pocket: how the wrong pocket problem stymies medical respite Care for the Homeless and What can be Done about it. Med Care. (2024) 62:376–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001998

44. Sadowski, LS, Kee, RA, VanderWeele, TJ, and Buchanan, D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. (2009) 301:1771–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.561

45. Doran, KM, Ragins, KT, Gross, CP, and Zerger, S. Medical respite programs for homeless patients: a systematic review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2013) 24:499–524. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0053

46. Moledina, A, Magwood, O, Agbata, E, Hung, J, Saad, A, Thavorn, K, et al. A comprehensive review of prioritised interventions to improve the health and wellbeing of persons with lived experience of homelessness. Campbell Syst Rev. (2021) 17:e1154. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1154

47. Luchenski, SA, Dawes, J, Aldridge, RW, Stevenson, F, Tariq, S, Hewett, N, et al. Hospital-based preventative interventions for people experiencing homelessness in high-income countries: a systematic review. eClinicalMedicine. (2022) 54:101657. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101657

48. Fazio, D, Zuiderveen, S, Guyet, D, Reid, A, Lalane, M, McCormack, RP, et al. ED-home: pilot feasibility study of a targeted homelessness prevention intervention for emergency department patients with drug or unhealthy alcohol use. Acad Emerg Med. (2022) 29:1453–65. doi: 10.1111/acem.14610

49. Arbour, M, Fico, P, Yu, N, Hur, L, Srinivasan, M, and Gitomer, RS. Redesign of a primary care–based housing intervention to address upstream housing needs. NEJM Catal. (2023) 4. doi: 10.1056/CAT.22.0403

50. Manuel, JI, Nizza, M, Herman, DB, Conover, S, Esquivel, L, Yuan, Y, et al. Supporting vulnerable people during challenging transitions: a systematic review of critical time intervention. Admin Pol Ment Health. (2023) 50:100–13. doi: 10.1007/s10488-022-01224-z

51. Samuels, J, Fowler, PJ, Ault-Brutus, A, Tang, DI, and Marcal, K. Time-limited case management for homeless mothers with mental health problems: effects on maternal mental health. J Soc Soc Work Res. (2015) 6:515–39. doi: 10.1086/684122

52. Fact sheet: Homelessness, health and medical-legal partnerships. Medical-legal partnership. Available online at: https://medical-legalpartnership.org/mlp-resources/homelessness-and-health/ (Accessed October 10, 2018).

53. Trott, J, Peterson, A, and Regenstein, M. Financing medical-legal partnerships. The National Center for medical-legal Partnership at the George Washington University. Washington, DC: The National Center for Medical Legal Partnership (2019). Available online at: https://medical-legalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Financing-MLPs-View-from-the-Field.pdf

54. Tsai, J, Middleton, M, Villegas, J, Johnson, C, Retkin, R, Seidman, A, et al. Medical-legal partnerships at veterans affairs medical centers improved housing and psychosocial outcomes for vets. Health Aff (Millwood). (2017) 36:2195–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0759

55. Tsai, J, Jenkins, D, and Lawton, E. Civil legal services and medical-legal partnerships needed by the homeless population: a National Survey. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107:398–401. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303596

56. Center for Health Care Strategies. Partnerships for action: California Health Care & Homelessness Learning Collaborative. (2022). Available online at: https://www.chcs.org/project/partnerships-for-action-california-health-care-homelessness-learning-collaborative/

57. Carrig, D. Detroit’s comprehensive medical respite program for homeless secures multi-sector investment. Kresge Foundation. (2023). Available online at: https://kresge.org/news-views/detroits-comprehensive-medical-respite-program-for-homeless-secures-multi-sector-investment/

58. Community Solutions. Health care and homelessness. Available online at: https://community.solutions/health-care-and-homelessness/

59. Davis, V, Sandor, B, Arsenault, M, Chimowitz, H, and Hardin, L. Health care’s role in ending homelessness. (2024). Available online at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20240523.243875/full/ (Accessed May 24, 2024).

60. Andi, B, Ben, B, and Meghan, A. Learning brief: data-sharing between homelessness and health systems. Community Solutions. (2023). Available online at: https://community.solutions/research-posts/learning-brief-data-sharing-between-homelessness-and-health-systems/ (Accessed September 6, 2023).

61. Mayors & CEOs. Mayors and CEOs for U.S. housing investment. Available online at: https://housinginvestment.org/mayors-and-ceos/

62. Ansell, DA, Fruin, K, Holman, R, Jaco, A, Pham, BH, and Zuckerman, D. The anchor strategy — a place-based business approach for health equity. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:97–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2213465

63. CVS Health and Fresno housing collaborate to address affordable housing crisis and provide healthy homes in Fresno County. (2022). Available online at: https://www.cvshealth.com/news/community/cvs-health-and-fresno-housing-collaborate-to-address-affordable.html (Accessed June 22, 2022).

64. Additional $100 Million Investment in Housing Bolsters UnitedHealth Group’s Efforts to Address Social Determinants and Achieve Better Health Outcomes. Available online at: https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/newsroom/2022/additional-housing-investment-bolsters-uhg-efforts.html

65. Healthcare Finance News. Kaiser Permanente is spending $400 million on affordable housing initiatives. (2022). Available online at: https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/kaiser-permanente-spending-400-million-affordable-housing-initiatives (Accessed April 19, 2022).

66. Rosenheck, R, Kasprow, W, Frisman, L, and Liu-Mares, W. Cost-effectiveness of supported housing for homeless persons with mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2003) 60:940–51. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.940

67. Evans, WN, Kroeger, S, Palmer, C, and Pohl, E. Housing and urban development-veterans affairs supportive housing vouchers and veterans’ homelessness, 2007-2017. Am J Public Health. (2019) 109:1440–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305231

68. VA announces goal to house 38,000+ veterans experiencing homelessness in 2023 - VA news. (2023). Available online at: https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-announces-goal-to-house-38000-veterans-experiencing-homelessness-in-2023/ (Accessed March 15, 2023).

69. Wilkinson, R, Byrne, T, Cowden, RG, Long, KNG, Kuhn, JH, Koh, HK, et al. First decade of supportive Services for Veteran Families Program and Homelessness, 2012-2022. Am J Public Health. (2024) 114:610–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2024.307625

70. Hinton, E, and Diana, A. Section 1115 Medicaid waiver watch: a closer look at recent approvals to address health-related social needs (HRSN). KFF. (2024). Available online at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/section-1115-medicaid-waiver-watch-a-closer-look-at-recent-approvals-to-address-health-related-social-needs-hrsn/

71. Hinton, E, and Diana, A. Medicaid section 1115 waivers: the basics. KFF. (2025). Available online at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-section-1115-waivers-the-basics/

72. Published: Medicaid waiver tracker: approved and pending section 1115 waivers by state. KFF. (2025). Available online at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/

73. Berkowitz, SA, Archibald, J, Yu, Z, LaPoint, M, Ali, S, Vu, MB, et al. Medicaid spending and health-related social needs in the North Carolina healthy opportunities pilots program. JAMA. (2025) 333:1041–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.1042

74. Ma, ZB, Khatri, RP, Buehler, G, Boutwell, A, Roeber, JF, and Tseng, K. Transforming care delivery and outcomes for multivisit patients. NEJM Catal. (2023) 4:23.0073. doi: 10.1056/CAT.23.0073

Keywords: healthcare, homelessness, framework, public health, hospitals

Citation: Liu JC, Ryan CJ, Olivet J, Lazowy EE and Koh HK (2025) Homelessness response: a framework for action by hospitals and healthcare systems. Front. Public Health. 13:1642073. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1642073

Edited by:

Francesco Puccio, President of the free voluntary Association "UN MEDICO X TE", ItalyReviewed by:

Evasio Pasini, University of Brescia, ItalyGiovanni Corsetti, University of Brescia, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Ryan, Olivet, Lazowy and Koh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joy C. Liu, am95bGl1QGFsYW1lZGFoZWFsdGhzeXN0ZW0ub3Jn

Joy C. Liu

Joy C. Liu Catherine J. Ryan

Catherine J. Ryan Jeff Olivet

Jeff Olivet Emily E. Lazowy

Emily E. Lazowy Howard K. Koh

Howard K. Koh