- 1Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech), Blacksburg, VA, United States

- 2School of Public and International Affairs, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, United States

- 3Department of Nutritional Sciences, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, United States

Introduction: Public policy plays an important role in shaping how infants are fed. The Global Breastfeeding Collective (GBC) provides a set of policy priorities for countries to promote, protect and support breastfeeding. The GBC uses scorecards to document progress toward meeting those priorities. The purpose of this study was to assess recent United States (U.S.) federal infant feeding policy changes against the GBC's policy priorities to identify areas of alignment and gaps for policies supporting optimal infant feeding.

Methods: Changes in U.S. federal infant feeding legislation, regulation, and presidential documents between 2014 and 2023 were compared with and coded into GBC priority categories. Policy changes not aligned with GBC priorities were coded into additional non-GBC topic categories that were developed inductively.

Results: Fifty-seven federal infant feeding policies were adopted or substantively modified within the study period. Of these, only 17 aligned with at least one of the GBC policy priorities. Forty-nine policies included changes that did not match GBC policy priorities. Policy changes that did not align with GBC priorities addressed infant formula manufacturing, lactation spaces, and breastfeeding supplies, among other topics.

Conclusion: Although most recent federal infant feeding policy changes in the U.S. did not align with the breastfeeding policy priorities established by the GBC, opportunities to promote and protect breastfeeding were identified. Some U.S. breastfeeding policy changes outside of GBC priorities have potential to strengthen breastfeeding.

1 Introduction

Despite known benefits, breastfeeding rates in the United States (U.S.) fall short of the U.S. Government's Healthy People 2030 objectives, which include increasing the percent of infants exclusively breastfed to at least six months of age to 42.4% and increasing the percentage of infants who are breastfed at 1 year to at least 54.1% (1–3). In 2025, U.S. rates are 27.7% for exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months and 39.5% for continued breastfeeding through 12 months (4). Factors contributing to the U.S. not meeting breastfeeding objectives include the effects of unrestricted infant formula marketing, the absence of comprehensive paid maternity leave and workplace lactation policies, and social norms that do not encourage breastfeeding, which are underscored by ethnic, racial, income, and educational disparities (3, 5–7).

Public health nutrition experts endorse public policies that support and promote optimal feeding of infants and young children (0–24 months) in the U.S. and globally (5, 8–10). Increasing breastfeeding behaviors would contribute to reaching both Healthy People 2030 national public health aims in the U.S. and the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (11, 12). The SDGs are a set of global priorities to improve health and education, increase economic growth, and reduce inequalities.

In 2017, the Global Breastfeeding Collective (GBC), a global partnership of agencies, including the US Agency for International Development and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), was launched by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund to speed global progress toward the achievement of breastfeeding targets by coalescing around shared policy priorities in the WHO's Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding (10, 13–15). The aim of the GBC is to increase the adoption, implementation, and enforcement of recommended policy priorities that protect, promote, and support breastfeeding. The GBC calls on governments to (1) increase funding to raise breastfeeding rates; (2) fully implement the International Code for Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (“the Code”), a set of legal guidelines aimed to restrict the promotion of infant formula by industry to protect breastfeeding, which the U.S. has not formally adopted (16–18); (3) enact paid family leave and workplace policies; (4) implement the “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding” in maternity facilities, a package of health care programs and policies in support of breastfeeding and to follow the Code in facilities designated as Baby-Friendly (19, 20); (5) improve access to skilled breastfeeding counseling; (6) strengthen links between health facilities and communities; (7) strengthen monitoring systems that track the progress of [breastfeeding] policies, programs and funding; and [expand]; (8) infant and young child support in emergencies (13). These policy priorities are recommended for all countries, developed and developing.

The GBC uses data sources, including from the CDC and the World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi), to track country-level implementation and performance across recommended policy priorities to monitor and assess progress toward the targets in the Global Breastfeeding Scorecard (10, 21–23). The WBTi, which is a collaborative network, follows country-level progress toward global targets to assess, monitor, and publicly display infant and young child feeding programs and policy progress using standardized metrics, and it compiles country reports that are used to update the GBC Scorecards (21–24). Based on 2019 data, the most recently available, the U.S. scored 40.5 on a 100-point scale, ranking it in the bottom quintile of countries, underscoring the need for improvements (15, 25).

Most U.S. infants are fed infant formula in the first year of life for part or all of their nutrients and infant diets globally are moving to formula feeding (26, 27). For families feeding infants with infant formula, it is an essential food (28). The COVID-19 pandemic and 2022 infant formula shortage (henceforth, “shortage”) in the U.S. affected infant formula supply chains, shifted breastfeeding and formula feeding practices, and affirmed infant formula as a critical food source to be protected (28–31). The shortage highlighted systematic inequalities, as populations with low incomes and from racial and ethnic minority groups were more likely to have to take on negative coping behaviors in response to the shortage (32–34). In light of the shortage, policymakers called for action to maintain and protect infant formula supply and public health nutrition experts urged policy responses that would support breastfeeding, in addition to protecting infant formula supply over the long-term (28, 29, 32, 35, 36).

The purpose of this study was to determine how federal U.S. infant feeding policy changes compare to the GBC policy area priorities. The extent to which U.S. federal policies, which tend to be stable and resistant to change (37), were adopted and substantively modified indicates attention to infant feeding as a public policy issue (38). A comparison of policy changes to GBC policy priorities identified through a policy scan assessing the timing and content of changes can be used to identify priorities and gaps in U.S. infant feeding policies and opportunities to enhance U.S. infant feeding policies within the highly connected and rapidly changing global food system (14, 39, 40).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

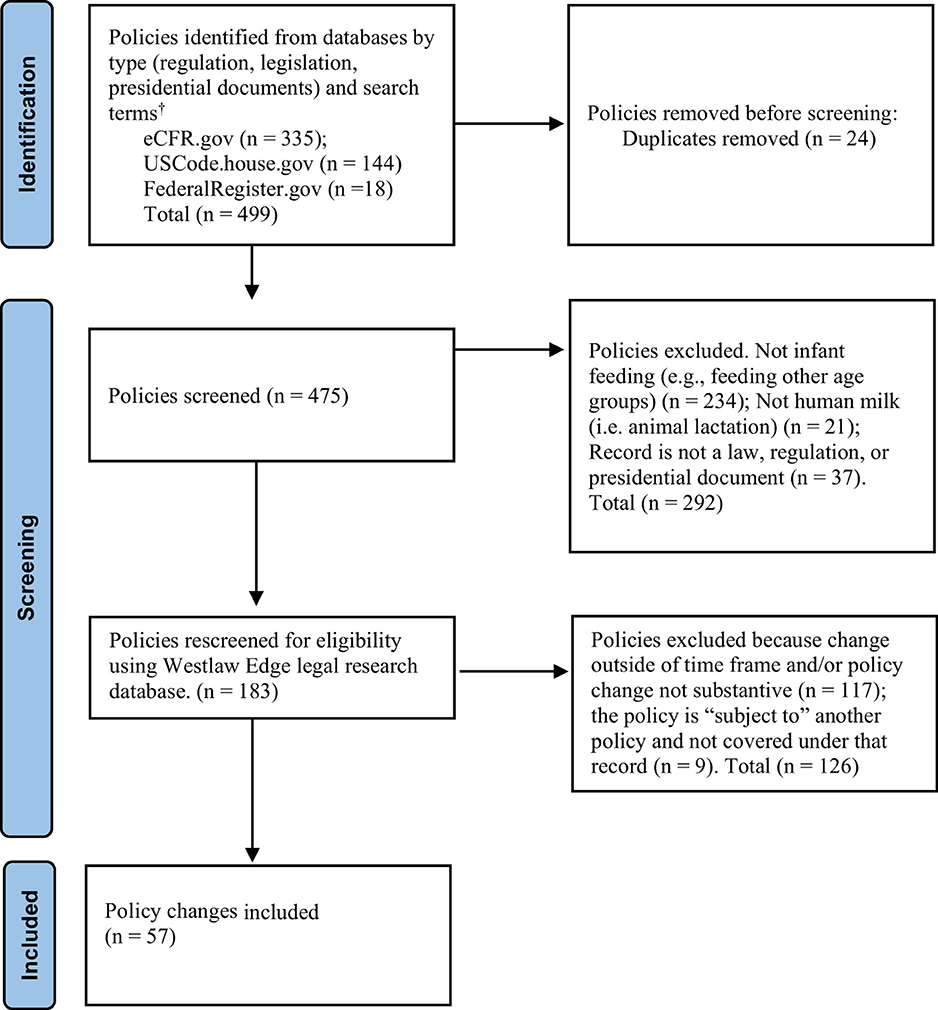

This study was part of a larger policy scan of U.S. infant feeding policy changes (41). Three online government policy databases—USCODE.house.gov, eCFR.gov, and federalregister.gov—and one legal research database, Westlaw Edge, were used to identify changes in federal infant feeding legislation, regulation, and presidential document policies between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2023 (42–45). Federal level legislative, regulatory and executive policies were selected because they are visible reflections of policymaker attention (46). An example of a legislative policy is 42 USC §1786, the law that covers the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). A regulatory policy example is 21 CFR §106.91, which regulates infant formula quality control processes. An example of a presidential document is 79 FR 36625, which is a presidential memorandum entitled Enhancing Workplace Flexibilities and Work-Life Programs that enhances support for lactation in workplaces. Presidential documents refer to policies that are issued to guide the executive branch of government, including executive orders and memorandums. Policy changes over a 10-year period were included in the study to provide an adequate timespan to compare changes over time and is consistent with other public health nutrition policy scans (47, 48).

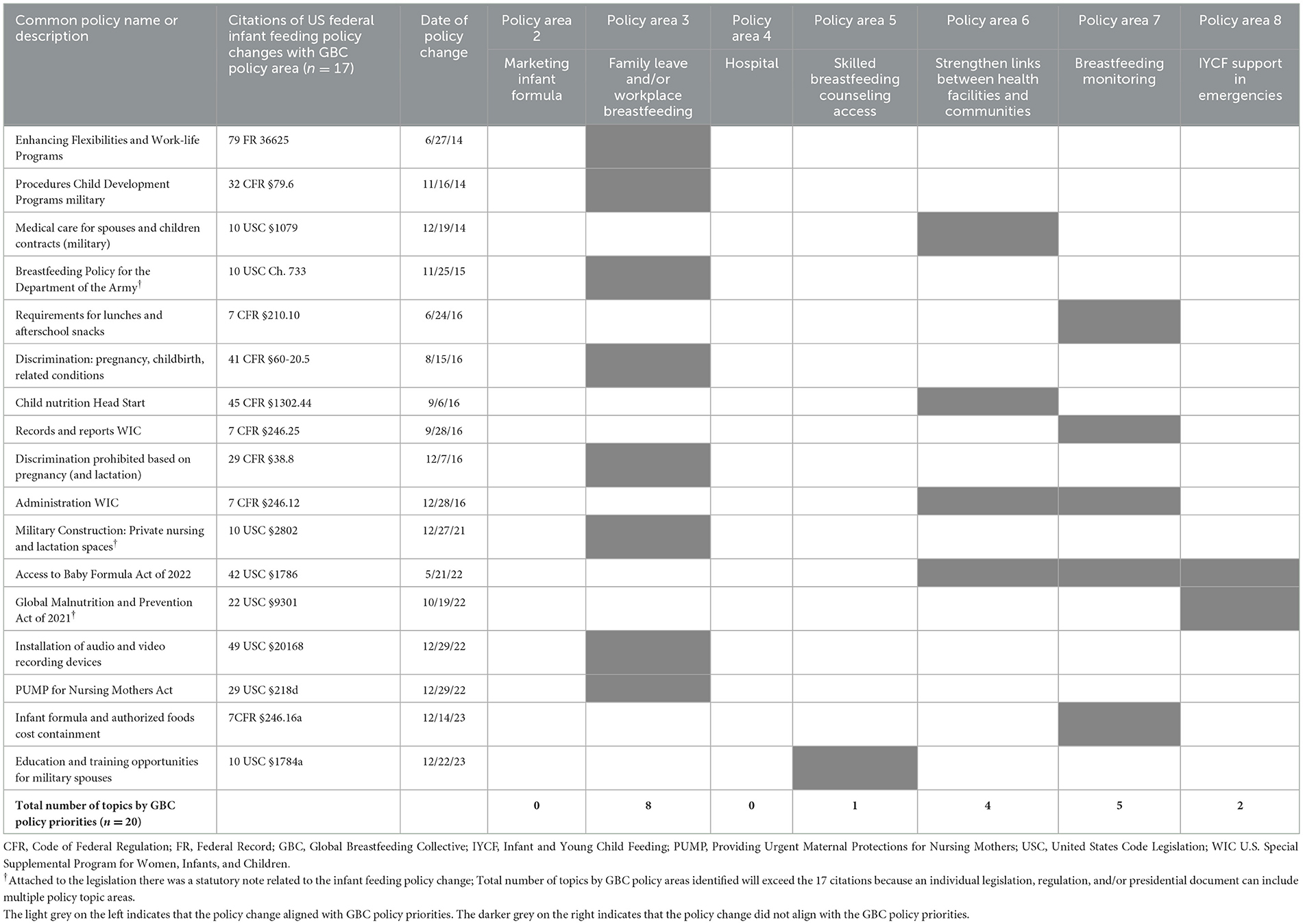

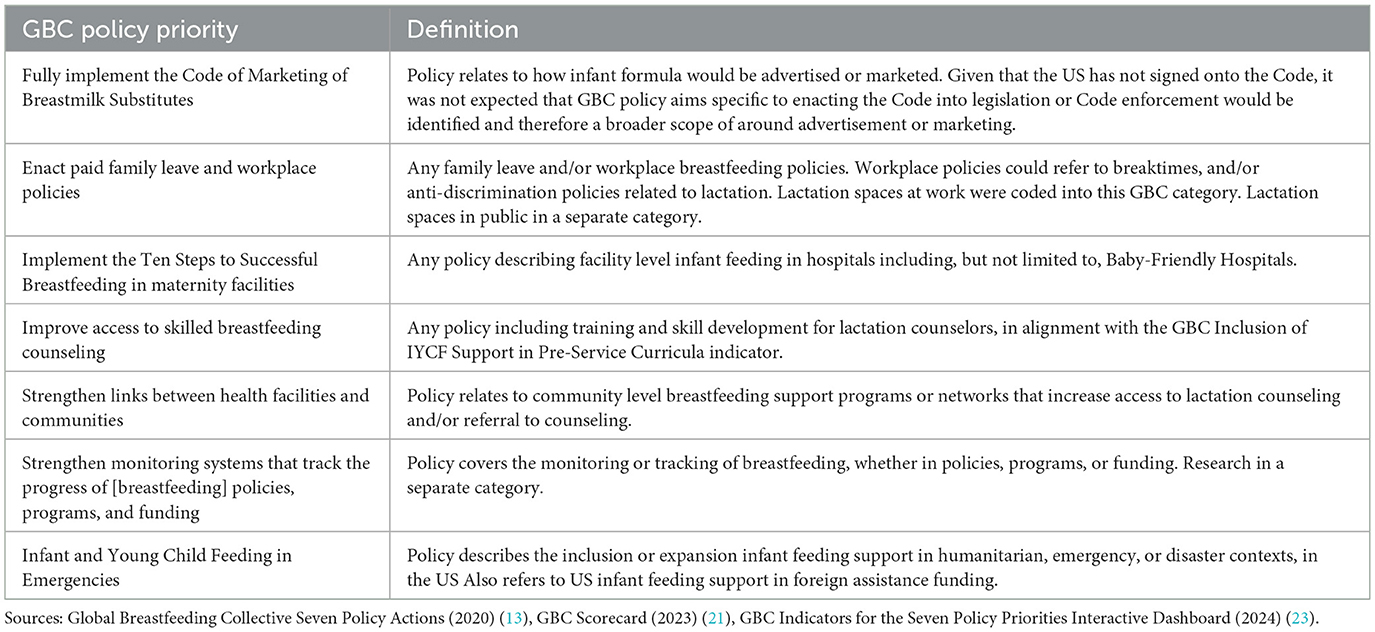

The study protocol, which was adapted from policy scanning processes used in previous research, involved (1) searching, identifying and screening infant feeding policies followed by reviewing verifying and extracting policy changes for inclusion in the study; and (2) analyzing, interpreting, and comparing relevant infant feeding policy changes (49–51), against recommended GBC breastfeeding policy priorities. The analysis followed seven policy area recommendations prioritized by the GBC (Table 1). The GBC recommendation to “Increase funding to raise breastfeeding rates from birth to 2-years” was outside of the scope of the analysis of infant feeding policies and thus not included, because funding levels are determined through separate appropriation procedures, not within the policy itself.

Table 1. Definitions for categorization of U.S. federal infant feeding policy changes according to Global Breastfeeding Collective (GBC) policy priorities in a U.S. context.

2.2 Policy screening, verification, extraction

The preliminary search for all federal-level infant feeding policies in the U.S. was carried out using the key search terms of “baby formula,” “breast*,” “infant feeding,” “infant formula,” “infant nutrition,” and “lactation.” The search strategy is presented in Figure 1. Two researchers separately scanned each of the full-text records that the search yielded and identified policies for inclusion by ensuring that the policies related to human infant feeding (PH, TK). Any disputes on inclusion were resolved in consultation with a third researcher (SM). After the preliminary screening, two researchers used the Westlaw Edge legal research database to review the policy language in each of the screened records a second time to verify that the policy change occurred within the designated time frame of the search and that the change was substantive (42). Policy change was determined by checking if the policy was new or substantively modified during the study window. Modifications were assessed by comparing the most recent language against previous versions of the policy in the history and credits section of Westlaw Edge for each record using the key search terms. A change was deemed substantive if the policy language differed from previous versions and was relevant to infant feeding. Amendments involving only nomenclature changes were not included. Any discrepancies were resolved in consultation between two researchers (PH, SM).

Figure 1. PRISMA style workflow diagram for identification of U.S. infant feeding policy changes from 2014 through 2023.†Search terms by regulations; breast* (n = 189); lactation (n = 32); “infant formula” (n = 105); “baby formula” (n = 1); “infant feeding” (n = 7); “infant nutrition” (n = 1); legislations; breast*(n = 110); lactation (n = 10); “infant formula” (n = 17); “baby formula” (n = 3); “infant feeding” (n = 3); “infant nutrition” (n = 1); presidential documents; breast*(n = 18); lactation (n = 1); “infant formula” (n = 1); “baby formula” (n = 0); “infant feeding” (n = 0); “infant nutrition” (n = 0).

Infant feeding policy changes that met inclusion criteria were put in a spreadsheet organized by U.S. policy citation, which describes the policy by title, type of policy (e.g., legislation, regulation, presidential document) and section designation. The common names of the policy, date of policy change, whether the policy was new or amended, the infant feeding topic areas addressed in the policy changed, and whether those topic areas aligned with GBC and/or non-GBC policy areas were recorded.

2.3 Policy changes compared against GBC policy recommendations

Two researchers (PH, SM) iteratively compared and sorted the identified policy changes into topic areas matching GBC policy priorities (21, 23). U.S. infant feeding policy changes that fell outside of GBC priorities were coded and sorted by the two researchers into non-GBC categories by topic area (e.g., lactation in public or infant formula supply) that were created inductively and informed by a review of the infant feeding policy literature. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion by the two researchers.

3 Results

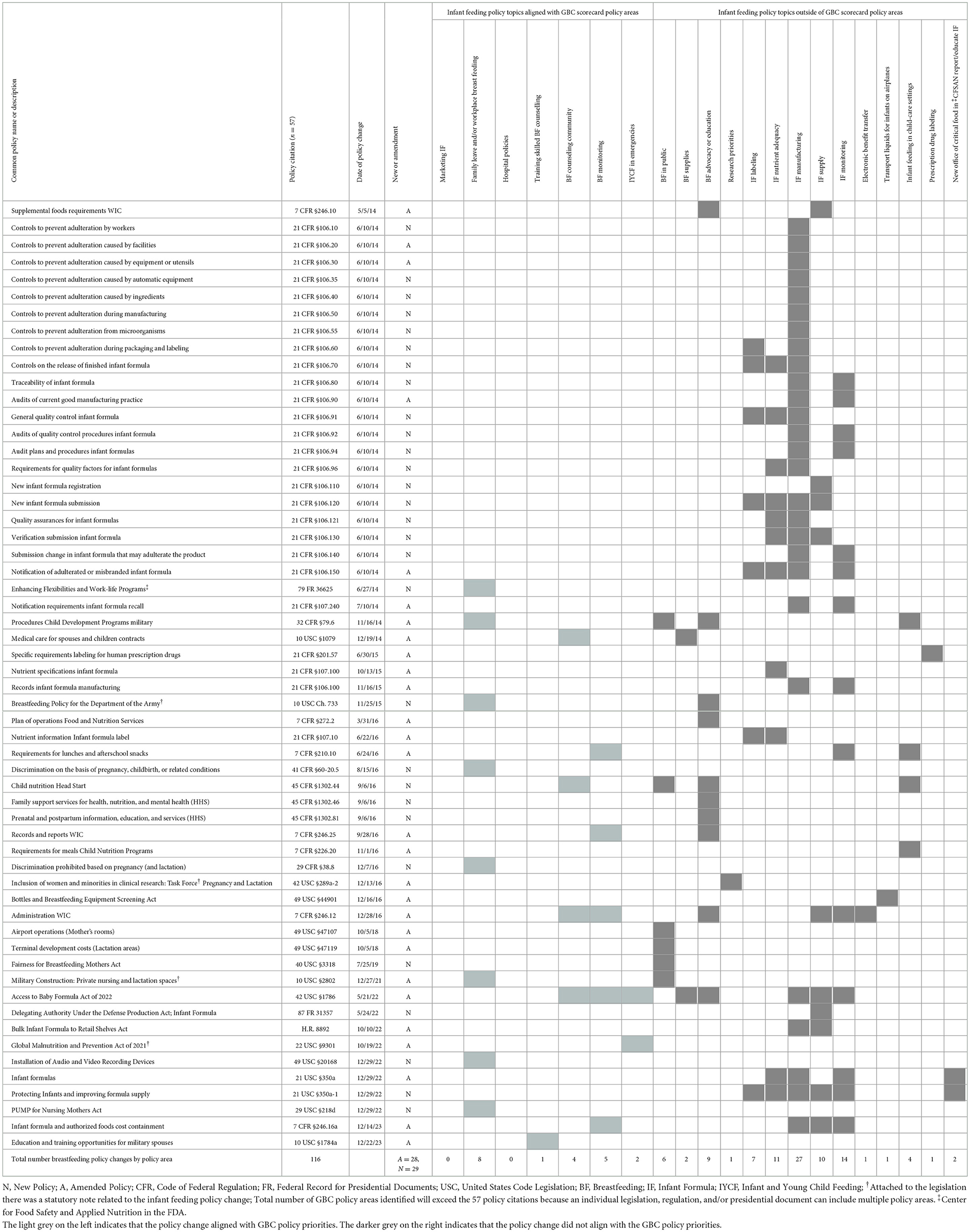

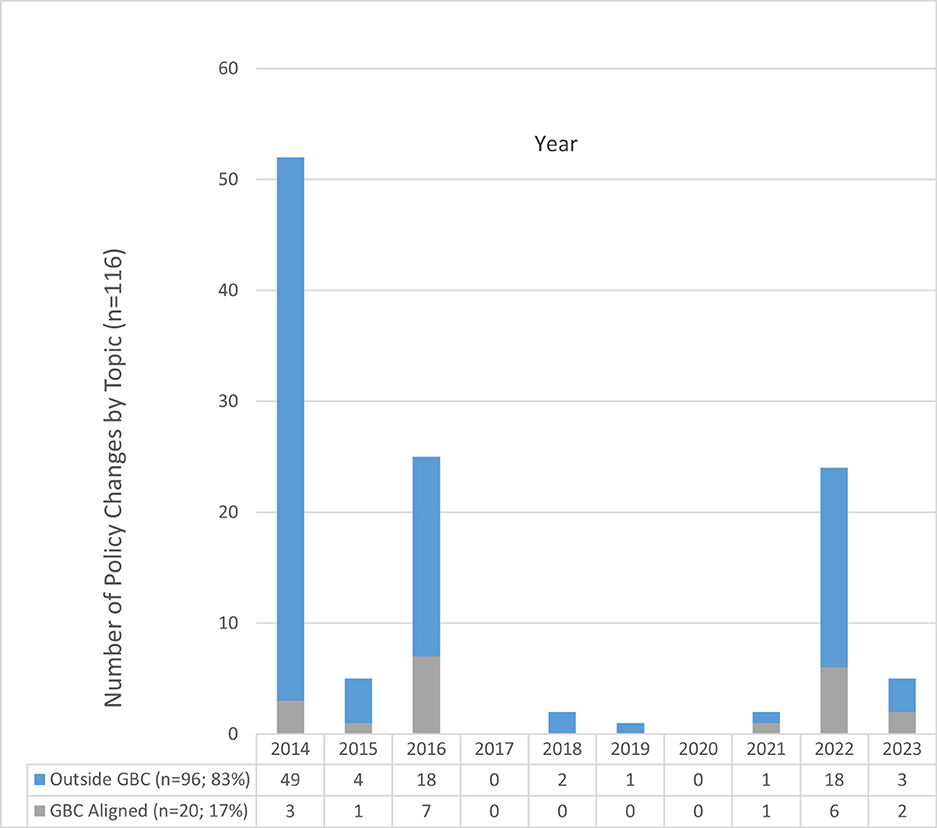

Fifty-seven new or substantively modified U.S. federal infant feeding policies were identified (Table 3). Twenty-nine of the 57 policies (51%) addressed more than one infant feeding policy topic area. Seventeen of the 57 policies (30%) aligned with at least one of the seven GBC policy areas−15 with a single policy priority, one with two policy topic priorities, and one with three GBC priorities (Table 2). In total, the 57 new or substantively changed policies covered 116 topics coded into GBC and non-GBC policy areas; 10 of the 57 policies (18%) addressed both GBC and non-GBC policy areas. Of the 116 topics addressed, 20 (17%) aligned with the seven GBC policy priorities and 96 (83%) topics were outside of GBC policy priorities (Figure 2; Table 3).

Figure 2. Chart of U.S. policy changes 2014 through 2023 by topic aligned or not aligned with Global Breastfeeding Collective policy priorities by year.

3.1 Policy changes aligned with GBC policy priorities

No policies adopted or substantively modified during the study window aligned with the infant formula marketing and hospital-level breastfeeding GBC recommendations. Eight policies addressed unpaid family leave and/or workplace accommodations for breastfeeding. Examples were the 2014 Enhancing Flexibilities and Work-Life Programs presidential memo, which called for private places to breastfeed and unpaid leave time to enhance work-life balance in the workforce, and the 2022 Providing Urgent Maternal Protections for Nursing Mothers (PUMP) Act, which mandated workplace lactation accommodations. Other policies provided increased privacy for breastfeeding military service members and transport workers, seeking to minimize lactation-based discrimination at work.

One policy met the GBC's aim of improving access to skilled breastfeeding counseling, by providing training for military spouses to be certified as doulas or Internationally Board-Certified Lactation Consultants. Four policies covered community-level breastfeeding counseling and/or referrals to counseling. Five policies addressed breastfeeding monitoring.

Two policies aligned with infant and young child support in emergencies. The first was the 2022 Access to Baby Formula Act, an amendment to WIC legislation, which waives administrative procedures for infant formula during U.S. emergencies. The Global Malnutrition Prevention Act (2022), which supported breastfeeding as part of U.S. foreign assistance development aid, also aligned with infant and young child support in emergencies.

3.2 Policy changes not aligned with GBC policy priorities

Forty-nine of the 57 policies included topics that did not align with the GBC policy priorities (Table 3). Infant feeding policy topics outside of the GBC priorities included breastfeeding lactation spaces outside the workplace, breastfeeding supplies, breastfeeding education, breastfeeding research, infant formula labeling, infant formula nutrients, infant formula manufacturing, infant formula supply, infant formula monitoring, electronic benefit transfers, the transport of liquids for infants on airplanes, and prescription drug labeling. Changes to Food and Drug Administration operations to oversee infant formula manufacturing and supplies and inform the public about infant formula were made.

Among the non-GBC changes related to breastfeeding, six policies classified under breastfeeding in public aimed to support breastfeeding outside of the home. The 2019 Fairness for Breastfeeding Mothers Act mandated that lactation rooms be made available to visitors in federal buildings. Other policies required providing lactation spaces in airports, military posts, and in child nutrition program sites, such as Head Start. Two policies supported access to breastfeeding supplies (e.g., breast pumps and/or milk storage bags), the 2022 Access to Baby Formula Act amendment to WIC and in 2014 military legislation. Four policies promoted breastfeeding and/or standards governing infant feeding, including procedures to properly store and handle breast milk in child-care programs. Nine policies included breastfeeding education. One modified policy promoted clinical research with protections for pregnant and lactating women.

Policies addressing the manufacturing of infant formula were the most frequent. Fourteen addressed the monitoring of infant formula, including quality control in manufacturing. Separate policies related to infant formula labeling and nutrients in infant formula. None of the policies identified included language on health claims about infant formula, which is recommended in Article 9 of the Code.

Ten policies included changes addressing infant formula supply; six of these 10 were put in place after the 2022 shortage. Those six policies included rules governing administration of the WIC program through the 2022 Access to Baby Formula Act; a 2022 presidential memo delegating executive level authority to ensure and control ingredients under the Defense Production Act; the 2022 Bulk Infant Formula to Retail Shelves Act, which waived duties on infant formula base imported into the U.S.; and an amendment to the regulation guiding WIC in 2023. In 2022, existing infant formula legislation was amended, including outlining new requirements for the Secretary of Health and Human Services to report to Congress and actions to undertake in the event of a future shortage, such as waiving import barriers for specialty infant formulas. Also in 2022, a new section of the infant formula legislation, entitled Protecting Infants and Improving Infant Formula Supply, was added. The new section specified Food and Drug Administration reporting and public communication actions and directed the Food and Drug Administration to develop a National Strategy on Infant Formula to protect infant formula, incentivize increased supply, and mitigate future shortages.

Three other policy topics did not align with GBC priorities: Changes to the WIC program were made to expand the use of electronic benefit transfers for the purchasing of infant formula. The “Bottles and Breastfeeding Equipment Screening Act” in 2016 specified exemptions to the “3–1–1 Liquids Rule” restricting the quantity of breastmilk, infant formula, or other liquids for infants allowed on airplanes. Regulatory changes on the labeling of prescription drugs addressed possible transmission of medicine or drugs through breastmilk to infants and when use of a drug is contraindicated during breastfeeding.

4 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore how changes in U.S. federal infant feeding policies compared to recommendations in the GBC policy priorities. It complements existing state and national assessments of U.S. breastfeeding policy implementation by examining changes across breastfeeding and infant formula policies and alignment with global priorities (52–57). While 17 of the 57 (30%) policies examined aligned with at least one of the GBC policy priorities, the other 70% did not align with any and the majority (49 out of 57, 86%) included changes outside the scope of the GBC priorities. Although U.S. and global progress for exclusive breastfeeding to the age of 6 months is increasing in comparison to past assessments, progress remains short of targets across multiple breastfeeding indicators (4, 22, 58). The lack of alignment between U.S. and GBC policy priorities suggests missed opportunities and challenges to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding in the U.S., which are consequential because misaligned policies can hinder the achievement of intended outcomes (59, 60). Furthermore, the GBC reported in 2025 that among 106 countries, 75 countries, including the U.S., reported increases in breastfeeding rates since 2017, but 29 countries reported decreases in breastfeeding (22).

Increasing funding to raise breastfeeding rates from birth to 2 years of age is an important GBC priority that was not compared against U.S. federal spending in this study. Assessment of funding was outside the scope and U.S. federal breastfeeding appropriations to agencies and programs is tracked by the United States Breastfeeding Collaborative, a breastfeeding support coalition (61). Modeling estimates of the costs of not breastfeeding in the U.S. document racial/ethnic breastfeeding disparities and that substantial health care costs could be prevented by improved breastfeeding rates (7, 62). A 2024 review concluded that total costs of not breastfeeding were typically calculated to be greater than approximately U.S.$100 billion in the U.S. and U.S.$300 billion globally each year, despite a diverse range of approaches and methods used (62). However, funding estimates to implement breastfeeding strategies vary and may be conservative, in part because the costs focused on health care approaches (e.g., lactation counseling) and other costs such as maternal time and/or social policies (e.g., paid leave) to protect breastfeeding were not adequately incorporated (62, 63).

Moreover, the GBC funding indicator is limited to the percentage of countries achieving a target of at least $5 USD per birth based on donor funding, a metric based on recommendations from the World Health Assembly to reach global exclusive breastfeeding targets (22). According to the 2024 GBC Scorecard report, which highlighted the need for accelerated government and donor commitments for breastfeeding, only 4% of countries globally met the GBC funding metric and already insufficient donor breastfeeding development aid contributions were dropping (22). No U.S. data was provided on the GBC funding indicator in the online GBC Scorecard (23). To help meet the GBC call to accelerate in-country and foreign-assistance donor commitments for breastfeeding worldwide, including medium and high-income countries, harmonization with and additional measures that assess progress toward funding targets across a range of GBC policy priorities, including from the Nutrition Accountability Framework of the Global Nutrition Report that monitors donor commitments (58), is warranted.

No policy changes identified in this study related to the marketing of infant formula. In the absence of Code implementation in the U.S., policies allow for the unrestrained marketing of infant formula and industry self-regulation, impeding breastfeeding and beneficial maternal, infant, and child health outcomes (3, 64–66). Researchers have identified federal policy actions that could be enacted across multiple agencies and levels to protect against deceptive infant formula marketing and health claims to align U.S. policies more closely with the Code, without formal endorsement (64, 67). Examples include ensuring that FDA infant formula labeling regulations follow those in the Code, mandating that infant formula manufacturers with WIC contracts adhere to provisions in the Code, and disallowing the distribution of free infant formula in hospital settings (17, 64, 67). Such policy changes were not identified in this study, but represent a future opportunities for research and policy.

Laws protecting workplace breastfeeding, including the provision of break times and paid maternity leave are associated with improved breastfeeding initiation and increased breastfeeding at 6 months (53, 68–70). The eight breastfeeding and work accommodation policies identified in this study suggest progress in closing the gap between U.S. and global policy priorities related to leave, breaktimes, lactation facilities, and privacy protections (23, 71). However, the U.S. policy of 12 weeks unpaid leave time falls far short on the paid family leave target in the GBC scorecard of 18 weeks of paid maternity leave, which was informed by International Labor Organization recommendations (and additionally fall short of 12-week paid family and medical leave recommendations endorsed by the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee) (23, 72, 73). This is consistent with other studies finding that the U.S. lacks comparable federal family leave policies and workplace breastfeeding protections to other high- and-middle-income countries (56, 69, 72, 74). The U.S. falls behind the number of weeks of leave benefits that are legislated in countries including the United Kingdom (52 weeks of which 39 weeks are paid), every country in Europe and Central Asia (ranging between 14 and 58 weeks), and either behind or on par with countries in the Americas (e.g., Canada has 17 weeks of leave; Uruguay 14 weeks, Jamaica and Mexico each have 12 weeks) (71).

The only policy change that specifically referenced unpaid leave policies and included language about breastfeeding support was the 2014 presidential memo to enhance workplace flexibilities and balance for families. While the 2022 PUMP Act extended breastfeeding privacy and the provision of “reasonable” break periods to a greater range of employee types, including home care workers, drivers, teachers, nurses, and agriculture workers, the PUMP Act does not require paid breaks and does not apply to all employee types (75). This highlights inequalities and persistent policy gaps in U.S. breastfeeding support.

No policy changes related to infant feeding in hospitals or supported the GBC aim to “Implement the Ten Steps to successful breastfeeding in maternity facilities”. According to the CDC, 29% of U.S. live births occur in Baby-Friendly designated hospitals, which falls short of GBC indicator target that >50% of births occur in Baby-Friendly facilities (22, 76). In comparison, the GBC reports from country-level data that none (0%) of the delivery facilities in France and 43% of facilities in Mexico are reported as Baby-Friendly, which raises country level considerations (22). In the U.S., unique factors including the absence of a nationalized health system and the fact that hospital policies are regulated and monitored at the state level may account for not meeting the GBC Ten Steps implementation goal. A 2023 review of Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative implementation in Mexico found uneven monitoring of Baby-Friendly Hospitals and monitoring of the Ten Steps in facilities (77). Overall, following previous recommendations, these findings highlight the importance of considering country specific contexts and need for timely, publicly available, and transparent data to assess progress, enhance comparability, and evaluate possible replicability of approaches across different settings (14, 56).

Only one policy corresponded to the GBC skilled breastfeeding counseling policy, which was the 2023 amendment to military law aimed to support military spouses to become Internationally Board-Certified Lactation Consultants or doulas, indicating an opportunity for increased training and skill development. Policies that provided community-level lactation counseling included 2016 and 2022 WIC policy changes, 2014 modifications to medical benefits for military families, and 2016 lactation counseling referral changes in Head Start program services. The WIC policy changes were consistent with findings in a review by Anstey et al. (2016) that documented the redoubling of efforts by WIC to improve and expand breastfeeding counseling and address breastfeeding inequalities following the 2011 U.S. Surgeon General's Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding (5, 74). Increasing access to lactation counseling in military benefits likely reflected the influence of the 2014 TRICARE Moms Improvement Act, which was enacted to extend Affordable Care Act breastfeeding counseling and breastfeeding supplies to military members and families (78). The TRICARE program provides benefits to personnel in the U.S. Armed Forces, military retirees, and their dependents.

The GBC policy priority of infant and young child feeding support in emergencies, such as public health emergencies or disasters caused by natural catastrophes, is an overlooked but emerging U.S. policy priority (54, 72). Breastmilk is the safest source of nutrition for infants during emergencies, as infant formula supplies can be disrupted and infant formula donations can be disorganized (72, 79). The 2022 Access to Baby Formula Act included new language waiving administrative procedures during U.S. emergencies or disasters for infant formula, but breastfeeding support was not included, indicating a policy gap to promote and safeguard breastfeeding during emergencies.

Breastfeeding-forward policy changes outside of the scope of GBC policy priorities that could contribute to the achievement of breastfeeding objectives in the U.S., and possibly in other countries, were identified. A promising non-GBC policy that can promote breastfeeding was ensuring lactation spaces outside of the home in work and public spaces. Many mothers have reported feeling embarrassed to breastfeed away from home, are not universally protected from being asked to leave public spaces when lactating, and need support to breastfeed outside of the home (5, 52, 56, 74). Specific to public spaces, six policies were put in place to support breastfeeding outside of the home, including a mandate to provide lactation spaces in airports and in child care program settings. While no U.S. federal policy allows breastfeeding in all private and public locations, some local and state level policies do (52, 56).

Increasing access to breastfeeding supplies is a non-GBC policy with the potential to support breastfeeding. Two changes included language about the provision of breastfeeding supplies to improve breastfeeding outcomes. Breast pumps have been widely used to initiate and maintain breastfeeding (80). Nardella et al. (81) found that breast pump use among mothers enrolled in Medicaid was associated with an average of over 20 more weeks of breastfeeding compared to mothers not using breast pumps, with the strongest associations found among Black and Native American respondents. This suggests a potential for policies that increase breastfeeding supplies to minimize breastfeeding disparities.

This study has limitations. It focused exclusively on U.S. federal-level policy change to assess national attention to infant feeding from policymakers. While the authors cast a wide net to capture policy change across a range of infant feeding topics across GBC and non-GBC topics to detect patterns and interpret policymaker attention, there are gaps in the comprehensiveness and depth in the results. Existing federal policies that were in place but did not change within the 10-year period studied were excluded from the study design. One example is the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, which includes prenatal health and workplace protections (57, 72). Formal amendments have not been made to the ACA law, and any changes in rules guiding the implementation of the ACA would have occurred at levels not included in this study. The findings in this study complement but do not replace the findings in other studies assessing the implementation or impacts of topic-specific infant feeding policies (52–54, 56, 57). Future studies could include static infant feeding policies that have been in effect with policy changes for a more complete assessment. In addition, while the focus on federal policy change allowed for an assessment of federal policy priorities, it did not account for state level changes Infant feeding laws have been shown to be variable across different states (52). In agreement with past recommendations, it is important to assess infant feeding policy implementation and changes at the state, global and other levels to determine policy coherence across multiple levels (52, 53, 59, 60, 64).

An additional limitation is that the policies included in the study were each given the same weight when they vary in scope, enforcement mechanisms, and potential for public health impact. For example, passage of the 2022 PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act (29 USC §218d)—an amendment to the 2010 Break Time for Nursing Mothers law in the Fair Labor Standards Act, which made important rule changes expanding workplace accommodations to pump breastmilk—is more significant and broader than a specific rule change in 2014 to enhance the traceability of infant formula (21 CFR §106.80). This comparison demonstrates the challenges of equating the weight the policy changes but also demonstrates the range of U.S. infant feeding policies and the stated commitment of U.S. policy makers to specific topics in infant feeding.

The GBC aim is to increase the adoption, implementation and enforcement of recommended policies to protect, promote and support breastfeeding worldwide (13). The emphasis of this study was on the adoption of U.S. infant feeding policies, by focusing on the identification of policy changes at the federal level over a 10 year period. In line with other studies calling for increased investment in implementation research and evaluation (14, 56, 77), future research should explore in more depth the implementation, enforcement, scope and effectiveness of U.S. infant feeding policies, over more time and at multiple levels to identify patterns, including when there are changes in political priorities.

Future assessment of how U.S. policies align with public health nutrition recommendations in both breastfeeding and infant formula feeding domains is needed. Given the frequent use of infant formula in the U.S., and growing transition to infant formula globally in infant diets (26, 27), there is a justification to explore breastfeeding and infant formula policies together and more comprehensively to assess policy activity, political considerations, as well as determinants and impacts using systematic and robust qualitative and quantitative methods that minimize potential bias and allow for greater comparability over time. Building on past recommendations, future research should highlight which populations benefit the most (and least) from infant feeding policies and consider implications within the global food system and for GBC adaptations (35, 39, 64, 70). To support caregivers working outside of the home in the U.S. and in other countries when appropriate, research that explores and compares the applicability of promising policies that are not GBC priorities but with the potential to support breastfeeding, such as increasing access to breastfeeding supplies, and the impacts of those policies, in various settings should be carried out.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PBH: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. TS: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SLV: Writing – review & editing. VEH: Writing – review & editing. TK: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SAM: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Margaret Hepler Fellowship awarded by the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise, at Virginia Tech.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030. Infants (2025). Available online at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/infants (Accessed August, 6, 2025).

2. Raju TNK. Achieving Healthy People 2030 breastfeeding targets in the United States: challenges and opportunities. J Perinatol. (2023) 43:74–80. doi: 10.1038/s41372-022-01535-x

3. Meek JY, Noble L. Technical Report: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics (2022) 150:e2022057989. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057989

4. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC's Early Childhood Nutrition Report: Data to Support Healthy Growth and Development for Children 5 Years and Younger (2025). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/media/pdfs/2025/06/CDC-EarlyChildhoodReport-6-2025-508.pdf (Accessed July 6, 2025).

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding (2011). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK52682/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK52682.pdf (Accessed August 6, 2025).

6. Tomori C. Overcoming barriers to breastfeeding. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2022) 83:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2022.01.010

7. Bartick MC, Jegier BJ, Green BD, Schwarz EB, Reinhold AG, Stuebe AM. Disparities in breastfeeding: impact on maternal and child health outcomes and costs. J Pediatr. (2017) 181:49-55.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.028

8. Barraza L, Lebedevitch C, Stuebe A. The Role of Law and Policy in Assisting Families to Reach Healthy People's Maternal, Infant, and Child Health Breastfeeding Goals in the United States, Supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the CDC Foundation through a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services (May 4, 2020). Available online at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/law-and-health-policy/topic/maternal-infantchild-health (Accessed February 15, 2025).

9. Pérez-Escamilla R, Tomori C, Hernández-Cordero S, Baker P, Barros AJ, Bégin F, et al. Breastfeeding: crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet. (2023) 401:472–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01932-8

10. World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding (2003). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241562218 (Accessed July 10, 2025).

11. Noiman A, Kim C, Chen J, Elam-Evans LD, Hamner HC, Li R. Gains needed to achieve Healthy People 2030 breastfeeding targets. Pediatrics (2024) 154:e2024066219. doi: 10.1542/peds.2024-066219

12. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goals: The 17 goals. Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (Accessed July 7, 2025).

13. World Health Organization United Nations Children's Fund. The Global Breastfeeding Collective: A Call to Action, Our Seven Policy Asks (2020). Available online at: https://www.globalbreastfeedingcollective.org (Accessed July 5, 2025).

14. Bégin F, Lapping K, Clark D, Taqi I, Rudert C, Mathisen R, et al. Real-time evaluation can inform global and regional efforts to improve breastfeeding policies and programmes. Maternal Child Nutr. (2019) 15:e12774. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12774

15. Gupta A, Suri S, Dadhich JP, Trejos M, Nalubanga B. The World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative: implementation of the Global strategy for infant and Young Child Feeding in 84 countries. J Public Health Policy. (2019) 40:35–65. doi: 10.1057/s41271-018-0153-9

16. World Health Organization. Thirty-Fourth World Health Assembly, World Health Organization (WHO), International code of marketing of breastmilk substitutes at 13, Res. WHA34.22. Geneva: WHO (1981). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241541601 (Accessed June 1, 2024).

17. World Health Organization. Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes: National Implementation of the International Code, Status Report. Geneva:WHO (2020). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240006010 (Accessed June 19, 2025).

18. Pomeranz JL. United States: protecting commercial speech under the first amendment. J Law Med Ethics. (2022) 50:265–75. doi: 10.1017/jme.2022.50

19. Baby Friendly USA. Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative: about us (n.d). Available online at: https://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/ (Accessed August 27, 2025).

20. World Health Organization. Implementation Guidance: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services—The Revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Geneva: WHO (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513807 (Accessed June 1, 2025).

21. Global Breastfeeding Collective. Global Breastfeeding Scorecard 2023: Rates of Breastfeeding Increase Around the World Through Improved Protection and Support (2023). Available online at: https://www.globalbreastfeedingcollective.org/global-breastfeeding-scorecard-0 (Accessed July 10, 2025).

22. Global Breastfeeding Collective. Global Breastfeeding Scorecard 2024: Meeting the Global Target for Breastfeeding Requires Bold Commitments and Accelerated Action by Governments and Donors (2025). Available online at: https://www.globalbreastfeedingcollective.org/media/2856/file (Accessed August 6, 2025).

23. Global Breastfeeding Collective. Global Breastfeeding Scorecard 2024: Interactive Dashboard. Available online at: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNWIwNTI1ZmItMzg3MS00ODAxLTgyMTItYTgxMTFjMGU4OGJiIiwidCI6Ijc3NDEwMTk1LTE0ZTEtNGZiOC05MDRiLWFiMTg5MjAyMzY2NyIsImMiOjh9. (Accessed July 15, 2025).

24. World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative. Available online at: https://www.worldbreastfeedingtrends.org/ (Accessed July 14, 2025).

25. World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative. United States Report. Available online at: https://www.worldbreastfeedingtrends.org/wbti-country-report.php2019 (Accessed July 14, 2025).

26. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Report Card (2022). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm (Accessed June 18, 2025).

27. Baker P, Santos T, Neves PA, Machado P, Smith J, Piwoz E, et al. First-food systems transformations and the ultra-processing of infant and young child diets: the determinants, dynamics and consequences of the global rise in commercial milk formula consumption. Matern Child Nutr. (2021) 17:e13097. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13097

28. Abrams SA. Making sense of the infant formula shortage: moving from short-term blame to long-term solutions. Nutr Today. (2023) 58:195–200. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000599

29. Abrams SA, Duggan CP. Infant and child formula shortages: now is the time to prevent recurrences. Am J Clin Nutr. (2022) 116:289–92. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac149

30. Imboden A, Sobczak B, Kurilla NA. Impact of the infant formula shortage on breastfeeding rates. J Pediatr Health Care. (2023) 37:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2022.11.006

31. Marino JA, Meraz K, Dhaliwal M, Payán DD, Wright T, Hahn-Holbrook J. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on infant feeding practices in the United States: food insecurity, supply shortages and deleterious formula-feeding practices. Matern Child Nutr. (2023) 19:e13498. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13498

32. Wang RY, Anand NS, Douglas KE, Gregory JC, Lu N, Pottorff AE, et al. Formula for a crisis: systemic inequities highlighted by the US infant formula shortage. Pediatrics (2024) 153:e2023061910 doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-061910

33. Toossi S, Todd JE, Hodges L, Tiehen L. Responses to the 2022 infant formula shortage in the US by race and ethnicity. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2025) 57:232–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2024.12.005

34. Keeve C FA, Berkley J. How parents coped with the infant formula shortage: about 20% of families reported difficulties in getting infant formula in summer 2023, down from 35% in fall 2022. In: U.S. Census Bureau. Available online at: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2024/04/infant-formula-shortage.html (Accessed April 6, 2025).

35. Pérez-Escamilla R. What will it take to improve breastfeeding outcomes in the United States without leaving anyone behind? Am J Public Health. (2022) 112:S766–S9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.307057

36. Doherty T, Coutsoudis A, McCoy D, Lake L, Pereira-Kotze C, Goldhagen J, et al. Is the US infant formula shortage an avoidable crisis? Lancet (2022) 400:83–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00984-9

37. Nielson AL. Sticky Regulations. U Chicago Law Rev. (2018) 85:85–143. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol85/iss1/3

38. True JL, Jones BD, Baumgartner FR. Punctuated-equilibrium theory: explaining stability and change in public policymaking. In:Sabatier PA, editor. Theories of the Policy Process, Second Edition. London: Routledge (2019). p. 155–87.

39. Food and Agriculture Organization. High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition on the Committee of World Food Security. Nutrition and food systems. Rome. (2017). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/39441a97-3237-46d3-91d9-ed1d13130420. (Accessed July 11, 2025).

40. Burris S, Ashe M, Levin D, Penn M, Larkin M, A. transdisciplinary approach to public health law: the emerging practice of legal epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health. (2016) 37:135–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021841

41. Harrigan P, Misyak S, Hedrick V, Volpe SL, Kim M, Zheng S, et al. Policy Changes to U.S. federal infant feeding laws and regulations from 2014-2023: evidence that the 2022 infant formula shortage had narrow policy impact. Health Aff Scholar (2025) 3:qxaf096. doi: 10.1093/haschl/qxaf096

42. Thompson Reuters. Westlaw Edge (2025). Available online at: https://training.thomsonreuters.com/legal-westlaw-edge (Accessed August 19, 2025).

43. U.S. House of Representatives. United States Code: Office of the Law Revision Counsel (n.d.). Available online at: https://uscode.house.gov/ (Accessed September 5, 2025).

44. National Archives. Code of Federal Regulations: A point in time eCFR system (2025). Available online at: https://www.ecfr.gov/ (Accessed July 14, 2025).

45. National Archives. Federal Register: A daily journal of the United States Government (2025). Available online at: https://www.federalregister.gov/ (Accessed July 14, 2025).

46. Birkland TA. An Introduction to the Policy Process: Theories, Concepts, and Models of Public Policy Making. 5th Edn. New York: Routeledge (2020). p. 250.

47. Sabatier PA. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci. (1988) 21:129–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00136406

48. Cleveland LP, Grummon AH, Konieczynski E, Mancini S, Rao A, Simon D, et al. Obesity prevention across the US: a review of state-level policies from 2009 to 2019. Obes Sci Pract. (2023) 9:95–102. doi: 10.1002/osp4.621

49. Ortiz K, Mellard D, Deschaine ME, Rice MF, Lancaster S. Providing special education services in fully online statewide virtual schools: a policy scan. J Spec Educ Leadersh. (2020) 33:3–13.

50. Cox T. The Policy Scan in 10 Steps, A 10 Step Guide Based on the Connecticut Chronic Disease Policy Scan. Hartford, CT: Connecticut Department of Public Health (2014).

51. Pomeranz JL, Mande JR, Mozaffarian DUS. policies addressing ultraprocessed foods, 1980-2022. Am J Prev Med. (2023) 65:1134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.07.006

52. Nguyen TT, Hawkins SS. Current state of US breastfeeding laws. Matern Child Nutr (2013) 9:350–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00392.x

53. Smith-Gagen J, Hollen R, Tashiro S, Cook DM, Yang W. The association of state law to breastfeeding practices in the US. Matern Child Health J (2014) 18:2034–43. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1449-4

54. Cadwell K, Turner-Maffei C, Blair A, Brimdyr K, O'Connor B. How does the United States rank according to the World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative? J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. (2018) 32:127–35. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000318

55. Tomori C, Hernández-Cordero S, Busath N, Menon P, Pérez-Escamilla R. What works to protect, promote and support breastfeeding on a large scale: a review of reviews. Matern Child Nutr. (2022) 18:e13344. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13344

56. Hernández-Cordero S, Pérez-Escamilla R, Zambrano P, Michaud-Létourneau I, Lara-Mejía V, Franco-Lares B. Countries' experiences scaling up national breastfeeding, protection, promotion and support programmes: comparative case studies analysis. Matern Child Nutr. (2022) 18:e13358. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13358

57. Hawkins SS. Affordable Care Act and breastfeeding. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2023) 52:339–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2023.08.004

58. PATH. Global Nutrition Report (2025). Available online at: https://globalnutritionreport.org/ (Accessed July 13, 2025).

59. May PJ, Sapotichne J, Workman S. Policy coherence and policy domains. Policy Stud J (2006) 34:381–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2006.00178.x

60. Nilsson M, Vijge MJ, Alva IL, Bornemann B, Fernando K, Hickmann T, et al. Interlinkages, integration and coherence. In:Biermann F, Hickmann T, Sénit C-A, editors. The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2022). p. 92–115. doi: 10.1017/9781009082945.005

61. U.S. Breastfeeding Committee. Federal Appropriations for Breastfeeding (2024). Available online at: https://www.usbreastfeeding.org/federal-appropriations-for-breastfeeding.html2024 (Accessed August 19, 2025).

62. Jegier BJ, Smith JP, Bartick MC. The economic cost consequences of suboptimal infant and young child feeding practices: a scoping review. Health Policy Plan. (2024) 39:916–45. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czae069

63. Shekar M, Kakietek J, Eberwein JD, Walters D. An Investment Framework for Nutrition: Reaching the Global Targets for Stunting, Anemia, Breastfeeding, and Wasting. Washington (DC): World Bank Publications (2017).

64. Harris JL, Pomeranz JL. Infant formula and toddler milk marketing: opportunities to address harmful practices and improve young children's diets. Nutr Rev. (2020) 78:866–83. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz095

65. Pomeranz JL, Harris JL. Federal regulation of infant and toddler food and drink marketing and labeling. Am J Law Med. (2019) 45:32–56. doi: 10.1177/0098858819849991

66. Piwoz EG, Huffman SL. The impact of marketing of breast-milk substitutes on WHO-recommended breastfeeding practices. Food Nutr Bull. (2015) 36:373–86. doi: 10.1177/0379572115602174

67. Soldavini J, Taillie LS. Recommendations for adopting the international code of marketing of breast-milk substitutes into US policy. J Hum Lact. (2017) 33:582–7. doi: 10.1177/0890334417703063

68. Vilar-Compte M, Hernández-Cordero S, Ancira-Moreno M, Burrola-Méndez S, Ferre-Eguiluz I, Omaña I, et al. Breastfeeding at the workplace: a systematic review of interventions to improve workplace environments to facilitate breastfeeding among working women. Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:110. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01432-3

69. Goodman JM, Williams C, Dow WH. Racial/ethnic inequities in paid parental leave access. Health Equity. (2021) 5:738–49. doi: 10.1089/heq.2021.0001

70. Segura-Pérez S, Hromi-Fiedler A, Adnew M, Nyhan K, Pérez-Escamilla R. Impact of breastfeeding interventions among United States minority women on breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:72. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01388-4

71. International Labor Organization. Care at Work: Investing in Care Leave and Services for a More Gender Equal World of Work. Geneva: ILO (2022). Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_838653.pdf (Accessed August 7, 2025).

72. U.S. Breastfeeding Committee. Policies and Actions. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Breastfeeding Committee (2025). Available online at: https://www.usbreastfeeding.org (Accessed July 11, 2025).

73. U.S. Department of Labor. Family and Medical Leave Act. Available online at: https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmlan.d (Accessed July 12, 2025).

74. Anstey EH, MacGowan CA, Allen JA. Five-year progress update on the Surgeon General's call to action to support breastfeeding. J Womens Health. (2016) 25:768–76. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5990

75. Stein C. The PUMP Act: legislation for working mothers. Am Bar Assoc. (2023) 51:8–10. Available online at: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/labor_law/resources/magazine/archive/pump-act-legislation-working-mothers/

76. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity Data Trends and Maps: Breastfeeding: Births Occurring at “Baby-Friendly” Hospitals (2021). Available online at: https://nccd.cdc.gov/dnpao_dtm/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=DNPAO_DTM.ExploreByTopic&islClass=BF&islTopic=BF2&islIndicators=Q016&go=GO (Accessed July 11, 2025).

77. Bueno AK, Vilar-Compte M, Cruz-Villalba V, Rovelo-Velázquez N, Rhodes EC, Pérez-Escamilla R. Implementation of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative in Mexico: a systematic literature review using the RE-AIM framework. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1251981. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1251981

78. U.S. Breastfeeding Committee. TRICARE Moms Improvement Act. Available online at: https://www.usbreastfeeding.org/existing-legislation.html (Accessed July 11, 2025).

79. Piovanetti Y, Calderon C, Budet Z, Aparicio RJ, Rivera Rios MV. Breastfeeding, a vital response in emergencies. Pediatrics (2022) 149:277. Available online at: https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/149/1%20Meeting%20Abstracts%20February%202022/277/186120 (Accessed August 7, 2025).

80. Rasmussen KM, Geraghty SR. The quiet revolution: breastfeeding transformed with the use of breast pumps. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:1356–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300136

Keywords: breastfeeding, Global Breastfeeding Collective, infant feeding, infant formula, policy

Citation: Harrigan PB, Schenk T, Volpe SL, Hedrick VE, Khan T and Misyak SA (2025) A comparison of U.S. infant feeding policy changes to Global Breastfeeding Collective policy priorities. Front. Public Health 13:1653377. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1653377

Received: 24 June 2025; Accepted: 14 August 2025;

Published: 17 September 2025.

Edited by:

Matilda Aberese-Ako, University of Health and Allied Sciences, GhanaReviewed by:

Kimielle Silva, Government of the State of São Paulo, BrazilHaeril Amir, Universitas Muslim Indonesia, Indonesia

Rochelle Embling, Public Health Wales NHS Trust, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Harrigan, Schenk, Volpe, Hedrick, Khan and Misyak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah A. Misyak, c21pc3lha0B2dC5lZHU=

†ORCID: Sarah A. Misyak orcid.org/0000-0002-4715-3464

Paige B. Harrigan

Paige B. Harrigan Todd Schenk

Todd Schenk Stella L. Volpe

Stella L. Volpe Valisa E. Hedrick1

Valisa E. Hedrick1 Tuba Khan

Tuba Khan