- 1Department of Interdisciplinary Social Science, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2Fetzer Institute, Kalamazoo, MI, United States

- 3Department of Social Policy and Intervention, Global Reference Group for Children Affected by Crisis, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 5Department of Social Policy and Intervention Evaluation, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 6University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

Child maltreatment remains a pervasive global issue with profound impacts on health, development, and societal well-being. While evidence-based strategies for violence prevention have expanded, the role of spirituality as a protective and rehabilitative factor remains underexplored in mainstream policy and practice. This perspective article examines how nurturing spiritual values across the life course—such as empathy, emotional regulation, and ethical decision-making—can contribute to violence prevention and resilience building. Drawing on recent empirical findings and global policy examples, the paper argues for the integration of positive spirituality into child protection and faith-based initiatives across home, school, and community settings. The article outlines actionable strategies for practitioners and policymakers, highlights culturally responsive measurement tools, and calls for strengthened collaboration between child protection and faith-based sectors. By advancing a holistic and values-based approach to caregiving, this perspective contributes to ongoing efforts to disrupt intergenerational cycles of violence and promote children’s well-being in low-, middle-, and high-income countries worldwide.

1 Introduction

Child maltreatment is a major global public health issue, affecting about 1 in 2 children aged 2–17 each year (1, 2). It includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, as well as neglect, and can be perpetrated by parents, peers, teachers, intimate partners, or others. These harms occur in various settings, including the home, schools, online spaces, communities, and institutions. Research is complicated by underreporting and varying definitions across countries (3). Yet, global estimates remain alarming: 12.7% of children experience sexual abuse, 22.6% physical abuse, 36.3% emotional abuse, 16.3% physical neglect, and 18.4% emotional neglect (4). Girls are more likely to experience sexual violence—around 20%, compared to 10% of boys—especially in school settings, while boys are more frequently subjected to physical violence such as corporal punishment (5). Child maltreatment is linked to a range of direct and indirect adverse outcomes, such as injury and death (6, 7) as well as unintended pregnancy, mental illness, substance abuse and premature mortality (8–11). Economically, its burden is substantial, accounting for up to 4.3% of annual global GDP (12). Violence often extends across generations; however, intergenerational transmission is not inevitable. Not all maltreated individuals go on to perpetrate abuse, as outcomes are mediated by broader ecological factors (13).

Over the past decade, initiatives to prevent violence against children have grown substantially, partly driven by the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Target 16.2 and the publication of the INSPIRE Framework, which outlines seven core strategies to prevent such violence (14). Using an acronym, the INSPIRE strategies are Implementation and enforcement of laws; Norms and values; Safe environments; Parent and caregiver support; Income and economic strengthening; Response and support services; and Education and life skills. Building on the INSPIRE framework and existing research on spirituality and health, this perspective article examines the potential of strengthening spirituality as a means of preventing child maltreatment and supporting the rehabilitation of survivors. In doing so, it defines spirituality as distinct from organized religion, recognizing it as a broader, more inclusive dimension of human experience. While religion refers to structured systems of beliefs and practices aimed at connecting with the transcendent (15), spirituality is broader and may exist outside formal religious affiliation. Some individuals identify as spiritual without belonging to a specific religion, although spirituality can also be expressed through various religious traditions, including Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Indigenous belief systems (16). This article focuses on nurturing positive spiritual development in children—an approach that transcends religious boundaries and applies across cultures and belief systems (17). Specifically, it proposes avenues through which policy makers, parents, faith leaders, educators, and child protection professionals can integrate spirituality into caregiving relationships through informed policies and practices. The central thesis posits that fostering spiritual development cultivates key life skills—including, for example, empathy, emotional regulation, critical reflection, and conflict resolution—which are essential for reducing the likelihood of violence in caregiving contexts. When nurtured in and by parents and caregivers, these spiritual competencies can enhance stress management and promote nonviolent, nurturing environments. In turn, children exposed to these values may internalize them, contributing to a disruption in the cycle of intergenerational violence and fostering community norms anchored in solidarity and compassion. The target audience for this perspective article is policymakers and professionals working on the prevention of violence against children (i.e., social service, health, education, and justice professionals) as well as faith leaders. Elucidating the relationship between the cultivation of spiritual values in childhood and their role as a protective factor for both perpetrators and victims of violence may enable the expansion of evidence-based initiatives within homes, schools, and communities, as well as contribute to the advancement of research in this domain.

The paper proceeds by defining and reporting key measures of positive spirituality and resilience, reviewing the empirical evidence supporting spirituality as a protective and rehabilitative factor, outlining actionable strategies for policymakers and professionals, and concluding with a discussion on next steps for integrating faith-based and child protection sectors to advance child well-being.

2 Defining and measuring positive spirituality and resilience

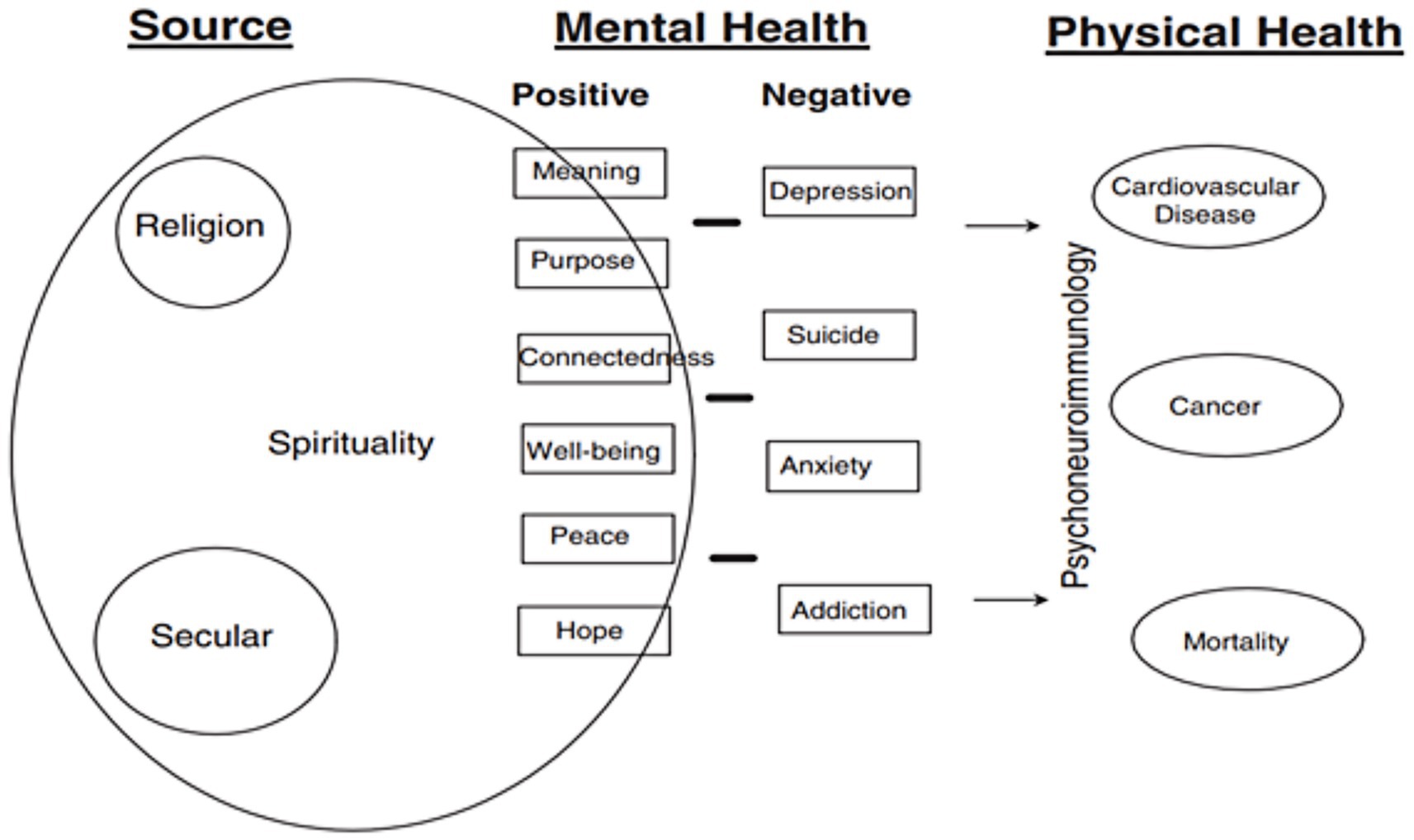

As of 2020, about 75.8% of the global population identifies with a religious or spiritual tradition; this estimate is based on data from the Pew Research Center, which includes over 2,700 censuses and surveys from 230 countries (18). Positive spirituality is broadly defined as the quest for meaning, purpose, and transcendence (19) and is increasingly recognized as an important internal resource that underpins psychological resilience (20, 21). Spiritual development is both globally relevant and culturally diverse, occurring both within and beyond the confines of organized religion (15, 16). As outlined by Koenig (22) in Figure 1, spirituality is increasingly linked to mental and physical health. However, its definition has broadened to include not only deeply religious individuals but also secular seekers of well-being. Modern tools for transmitting and measuring spirituality often incorporate traits such as optimism, gratitude, and purpose, which are also recognized as indicators of good mental health (22).

Figure 1. Definition of spirituality and its relationship to mental and physical health (22).

Before further defining it, it is important to note that spiritual development is neither linear nor universally positive. While it can foster values such as moral integrity, emotional well-being, and resilience, it can also, under certain conditions, engender intolerance, discrimination, or reinforce harmful norms and practices (23–27). Acknowledging these complexities and potential negative outcomes, the current discussion focuses on the positive contributions that child protection professionals and spiritual leaders can make in cultivating nonviolent, nurturing environments for children.

Drawing on the work of the Consortium on Nurturing Values and Spirituality in Early Childhood, along with established social–emotional learning frameworks (28) and recent literature reviews (29), five key domains of spiritual values and capacities have been identified below. When nurtured, these domains may support mental health, strengthen resilience, and help reduce violence. The categories are not rigid divisions; many of these values and capacities are interrelated. For example, a child, youth, or adult who has developed self-awareness and relationship skills may devise an alternative option to resolve a conflict rather than resorting to violence.

1. Self-awareness: This involves recognizing personal emotions and understanding the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Related concepts include mindfulness, self-discipline, purposefulness, and mastery of self.

2. Self-management: This encompasses adaptive behaviors such as relaxation techniques, positive self-talk, goal-setting, and intentional focus. Keywords associated with this domain include determination, detachment, self-regulation, and intentionality.

3. Social awareness: Refers to the ability to empathize, appreciate diversity, and engage with others from a place of compassion and curiosity. Keywords include wonder, gentleness, and imagination.

4. Responsible decision-making: Involves ethical problem-solving and discernment. Key values include respect, justice, peacefulness, and truthfulness.

5. Relationship skills: Reflect capacities for trust-building, altruism, and cooperation. Concepts include generosity, humility, community-mindedness, and gratitude.

Measuring spirituality, while inherently complex due to its subjective and culturally embedded nature, is increasingly feasible. Tools such as the Psycho-Spiritual Wellbeing Scale (P-SWBS) assess various dimensions, including connectedness, compassion, and transcendence (30). Spirituality-specific tools include the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale [DSES; (31)], the Spiritual Transcendence Index (32), and the Expressions of Spirituality Inventory (33). Contextually adapted instruments like the Wicozani Instrument, developed for Indigenous populations, further reflect the diversity in spiritual expression (34, 35). For adolescents, the Adolescent Spiritual Health Scale—validated across 12 countries—assesses spiritual connectedness and has demonstrated associations with positive mental health (36, 37). In clinical settings, the FICA Spiritual History Tool is also adapted for youth to evaluate spiritual identity, values, community involvement, and relevance to care (38).

3 Spirituality as a protective and rehabilitative factor

In a recently published article on the link between spirituality and health care, 166 articles were analyzed, revealing 24 commonly cited dimensions of spirituality, primarily related to connectedness and life meaning (39). Based on this, a framework was developed to quantify spirituality, supporting its relevance in healthcare research and practice (39). In complement to this research and framework, and building on the definitions of violence and spirituality, this section synthesizes empirical findings on the protective and rehabilitative roles of spirituality specifically in the context of child maltreatment. Drawing on a public health framework, the summary below is organized according to the three levels of prevention: primary (preventing onset), secondary (early intervention), and tertiary (rehabilitation) (2).

3.1 Primary prevention

Recent meta-analytic evidence reveals a consistent inverse association between spiritual or religious involvement and violent behaviors. Gonçalves et al. (40) found that over half (55.4%) of 101 outcomes across 269,910 individuals demonstrated that spirituality or religion significantly reduced the likelihood of physical and sexual aggression. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of 60 empirical studies found that religious beliefs and behaviors exert a deterrent effect on criminal behavior, including violence (41) and broad reviews of over 350 physical health and 850 mental health studies show that spiritual engagement is linked with lower levels of anxiety and depression—two key risk factors for violent behavior (42–44).

3.2 Secondary prevention

Spirituality also plays a crucial role in fostering resilience and promoting recovery following exposure to violence. Schwalm et al. (20) report a statistically significant positive correlation between spiritual engagement and resilience. Cultivating spiritual beliefs has been shown to moderate emotional responses to trauma, potentially interrupting intergenerational cycles of abuse (45, 46). Among survivors of sexual violence, those who experienced spiritual growth post-trauma demonstrated enhanced psychological recovery (47). Similarly, spiritual beliefs were found to enhance resilience and reduce trauma-related symptoms among survivors of violent trauma in an extensive community study (48).

3.3 Tertiary prevention

Engagement in religious communities and volunteerism has been associated with improved purpose and healing (49, 50). In humanitarian crises, spiritual support has been shown to alleviate stress and reduce the risk of violence among displaced populations (51–53), and in conflict-affected regions, spiritual resources have been linked to improved parenting capacity and reduced use of violent discipline (54–57).

4 Actionable strategies for practitioners and policymakers

Children’s development of spiritual values and capacities does not occur in isolation. Three foundational conditions are essential for nurturing these elements: a safe, nonviolent, and respectful environment; caring and positive relationships with parents, caregivers, and educators; and opportunities for children to practice and internalize their own spiritual development (58). Building on the growing evidence base that highlights spirituality as a valuable tool in violence prevention and response, this section presents practical, evidence-based strategies for integrating spiritual values and capacities at various levels, ranging from the policy level to family, education, child protection, and religious institutions.

Evidence suggests that, in the broader realm of child and family support, policies have consistently demonstrated an impact in promoting child well-being (59). While regional trends are challenging to identify, several countries provide illustrative examples of how spirituality can be integrated into child-focused frameworks. For instance, Malaysia’s Child Act mandates the inclusion of moral and spiritual considerations in child welfare policy (60), and Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness framework integrates spiritual values across multiple sectors (61, 77). Educational reforms in other nations have followed similar trends: Bolivia promotes Indigenous spiritual values in curricula (62), Kenya incorporates spiritual knowledge into school readiness assessments (63), and countries such as Malawi, Mauritius, and the Solomon Islands explicitly include spiritual development in early childhood education (64–66). Given the likelihood that policies will translate into legislation or codes of practice (67), these examples provide interesting case studies for aligning national policies with the spiritual dimensions of child well-being.

Shifting from policy to relationships, the role of the child’s immediate environment becomes central. When children are treated as spiritual beings—through safe, loving relationships that affirm their agency and sense of purpose—they are more likely to thrive (50). Thriving children are better equipped to make sound decisions, treat others with respect, and develop a strong sense of social responsibility (50). To effectively nurture spirituality in children, adults must also engage in their own spiritual growth (i.e., the metaphor of filling one’s own cup before pouring into others). In 2021, the World Health Organization commissioned two systematic reviews on parenting interventions, covering 435 randomized controlled trials across 65 countries (68). The findings showed that providing support to parents consistently leads to reductions in negative parenting behaviors, including maltreatment, and improvements in nurturing practices across all regions and types of interventions. The “Toolkit on Nurturing the Spiritual Development of Children in the Early Years” provides practical resources such as a “Learning Program for Adults” and an “Activities for Children” booklet to support this dual development (58).

Faith communities also play a powerful role. A scoping review of 172 sources on faith-based initiatives found that religious leaders are uniquely positioned to reinterpret harmful doctrines and instead promote beliefs that protect children and encourage responsive caregiving (69). The importance of this role was underscored during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the WHO advocated for the inclusion of faith actors in emergency response efforts due to their wide-reaching influence (70). While unstructured, everyday interactions are crucial for the development of spiritual values and capacities, structured strategies are also vital for preventing intentional violence. Evidence from socioemotional learning programmes—especially those implemented in schools using the Strengths Approach, a social justice-oriented framework (71)—demonstrates their potential to promote nonviolent behavior and reduce violence when caregivers and communities are actively involved (72–75). Effective programmes typically include five key components: (1) diverse learning tools such as videos, games, discussions, and visual aids; (2) repeated exposure through multiple lessons and ongoing reinforcement; (3) interactive peer activities like role-plays to encourage positive norms; (4) whole-school engagement, including leadership participation; and (5) active parental involvement through take-home materials rather than passive information sessions (29). By intentionally combining spiritual values, developmentally supportive relationships, and evidence-based programme structures, child protection practitioners can more effectively prevent violence and support recovery for affected children.

5 Discussion

The practical implications of this perspective, suggested below, are evidence-informed and multifaceted. On the research front, efforts should focus on developing validated and unified metrics that can meaningfully capture spiritual dimensions, distinct from indicators of religious attendance or mental health (e.g., the key domains outlined in Section Two: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, responsible decision-making, and relationship skills). Greater investment is then needed in longitudinal and quasi-experimental research to explore how spiritual values and capacities are most effectively transmitted, and how they contribute to reducing violence over time (20, 40). At the policy level, global and regional initiatives should be strengthened to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and best practices for integrating spirituality into policy frameworks. At the family level, parenting and caregiver support programmes—shown to be effective across diverse regions (68)—should intentionally include the transmission of spiritual values and capacities, such as empathy and emotional regulation, which were identified in Section 2 as protective factors. Likewise, faith leaders—who research shows can shift harmful norms and promote nurturing beliefs (69)—should collaborate with educators and child protection workers through structured and culturally grounded initiatives such as camps, sermons, and school-based programmes that promote positive values and capabilities, contributing to the protection and well-being of children.

In line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which calls for global peace, justice, and strong institutions (76), it is essential to engage both governments and grassroots actors—parents, caregivers, educators, and faith leaders—in this shared mission. Fostering spiritual values and capacities is not only a means of preventing violence against children and upholding their rights but also a vital foundation for building societies rooted in peace, empathy, and shared responsibility.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SV: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. KA: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SH: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. ST: Writing – review & editing. XL: Writing – review & editing. MS: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Hillis, S, Mercy, J, Amobi, A, and Kress, H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: a systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics. (2016) 137:e20154079. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4079

2. Krug, EG, Mercy, JA, Dahlberg, LL, and Zwi, AB. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2002).

3. UNICEF. Hidden in plain sight: A statistical analysis of violence against children. New York: UNICEF (2014).

4. Stoltenborgh, M, Bakermans-Kranenburg, MJ, Alink, LR, and van IJzendoorn, MH. The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Rev. (2015) 24:37–50. doi: 10.1002/car.2353

5. Devries, K, Knight, L, Petzold, M, Merrill, KG, Maxwell, L, Williams, A, et al. Who perpetrates violence against children? A systematic analysis of age-specific and sex-specific data. BMJ Paediatr Open. (2018) 2:e000180. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000180

6. Gilbert, R, Widom, CS, Browne, K, Fergusson, D, Webb, E, and Janson, S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. (2009) 373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7

7. Jenny, C, and Isaac, R. The relation between child death and child maltreatment. Arch Dis Child. (2006) 91:265–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.066696

8. Berger, R, Dalton, E, and Miller, E. How much more data do we need? Making the case for investing in our children. Pediatrics. (2021) 147:e2020031963. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-031963

9. Hughes, K, Bellis, MA, Hardcastle, KA, Sethi, D, Butchart, A, Mikton, C, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2017) 2:e356–66. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

10. Petruccelli, K, Davis, J, and Berman, T. Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. (2019) 97:104127. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127

11. Van der Ende, K, Chiang, L, Mercy, J, Shawa, M, Hamela, J, Maksud, N, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and HIV sexual risk-taking behaviors among young adults in Malawi. J Interpers Violence. (2018) 33, 1710–1730. doi: 10.1177/0886260517752153

12. Fang, X, Zheng, X, Fry, DA, Ganz, G, Casey, T, Hsiao, C, et al. The economic burden of violence against children in South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:1431. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111431

13. Narayan, A, Lieberman, A, and Masten, A. Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Clin Psychol Rev. (2021) 85:101997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101997

14. World Health Organization. INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. Washington, DC: World Health Organization (2016).

15. Koenig, HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry. (2012) 2012:278730. doi: 10.5402/2012/278730

16. Holland, JC, Kash, KM, Passik, S, Gronert, MK, Sison, A, Lederberg, M, et al. A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness. Psycho-Oncology. (1998) 7:460–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199811/12)7:6<460::AID-PON328>3.0.CO;2-R

17. Neky, A. (2022). Founding coordinator of the United Nations sustainable development platform, Personal Communications.

18. Hackett, C., Stonawski, M, Tong, Y, Kramer, S, Shi, A, Fahmy, D, et al., (2025). How the global religious landscape changed from 2010 to 2020, Pew Research Center. United States of America. Available online at: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/7s4s9yk (Accessed July 26, 2025)

19. Sajja, A, and Puchalski, C. Training physicians as healers. AMA J Ethics. (2018) 20:655–E663. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2018.655

20. Schwalm, FD, Zandavalli, RB, de Castro Filho, ED, and Lucchetti, G. Is there a relationship between spirituality/religiosity and resilience? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Health Psychol. (2022) 27:1218–32. doi: 10.1177/1359105320984537

21. Smith, BW, Ortiz, JA, Wiggins, KT, Bernard, JF, and Dalen, J. Spirituality, resilience, and positive emotions In: L. J. Miller (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Psychology and Spirituality (2013). 437–454. Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199729920.013.0028

22. Koenig, HG. Concerns about measuring “spirituality” in research. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2008) 196:349–55. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816ff796

23. Estrada, C, Lomboy, M, Gregorio, E, Amalia, E, Leynes, C, Quizon, R, et al. Religious education can contribute to adolescent mental health in school settings. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2019). 13:28. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0286-7

24. Rodriguez, C. And Henderson, R. (2010). Who spares the rod? Religious orientation, social conformity, and child abuse potential. Child Abuse Negl, 34, Pages 84–94, doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.002

25. Tomkins, A, Duff, J, Fitzgibbon, A, Karam, A, Mills, EJ, Munnings, K, et al. Controversies in faith and health care. Lancet. (2015) 386:1776–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60252-5

26. Woessmann, L., Zierow, L., and Arold, B. (2022). Religious education in school affects students’ lives in the long run. Cent Econ Pol Res Publ. Available online at: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/religious-education-school-affects-students-lives-long-run (Accessed June 20, 2025).

27. Wolf, J, and Kepple, N. Individual- and county-level religious participation, corporal punishment, and physical abuse of children: an exploratory study. J Interpers Violence. (2019) 34:3983–94. doi: 10.1177/0886260516674197

28. Lawson, GM, McKenzie, ME, Becker, KD, Selby, L, and Hoover, SA. The core components of evidence-based social emotional learning programs. Prev Sci. (2019) 20:457–67. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0953-y

29. Finkelhor, D, Walsh, K, Jones, L, Sutton, S, and Opuda, E. (2022). What works to prevent violence against children online? Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240062061 (Accessed January 10, 2025).

30. Egunjobi, JP, Habimana, P, and Onye, JN. Development, reliability, and validity of psycho-spiritual wellbeing scale (P-SWBS). Int J Res Innov Soc Sci. (2023) VII:926–39. doi: 10.47772/IJRISS.2023.7011071

31. Underwood, LG, and Teresi, JA. The daily spiritual experience scale: development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann Behav Med. (2002) 24:22–33. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04

32. Seidlitz, L, Abernethy, AD, Duberstein, PR, Evinger, JS, Chang, TH, and Lewis, BBL. Development of the spiritual transcendence index. J Sci Study Relig. (2002) 41:439–53. doi: 10.1111/1468-5906.00129

33. Lazar, A. The expressions of spirituality inventory (ESI): a multidimensional measure for expression of multi-domain spirituality. In A. I. Ai, P. Wink, R. F. Paloutzian, & K. I. Harris (Eds.), Assessing spirituality in a diverse world. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. (2021). 271–95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-52140-0_14

34. Fleming, J, and Ledogar, RJ. Resilience and indigenous spirituality: a literature review. Pimatisiwin. (2008) 6:47.

35. Peters, HJ, and Peterson, TRDakota Wicohan Community. Developing an indigenous measure of overall health and well-being: the Wicozani instrument. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (2019) 26:96–122. doi: 10.5820/aian.2602.2019.96

36. Government of Canada (2022), The health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study in Canada. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/child-infant-health/school-health/health-behaviour-school-aged-children.html (Accessed February 10, 2025).

37. Michaelson, V, Šmigelskas, K, King, N, Inchley, J, Malinowska-Cieślik, M, Pickett, W, et al. Domains of spirituality and their importance to the health of 75,533 adolescents in 12 countries. Health Promot Int. (2023) 38:daab185. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daab185

38. Borneman, T, Ferrell, B, and Puchalski, CM. Evaluation of the FICA tool for spiritual assessment. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2010) 40:163–73.

39. de Brito Sena, MA, Damiano, RF, Lucchetti, G, and Peres, MFP. Defining spirituality in healthcare: a systematic review and conceptual framework. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:756080. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.756080

40. Gonçalves, JPDB, Lucchetti, G, Maraldi, EDO, Fernandez, PEL, Menezes, PR, and Vallada, H. The role of religiosity and spirituality in interpersonal violence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry. (2023) 45:162–81. doi: 10.47626/1516-4446-2022-2832

41. Baier, CJ, and Wright, BRE. “If you love me, keep my commandments”: a meta-analysis of the effect of religion on crime. J Res Crime Delinq. (2001) 38:3–21. doi: 10.1177/0022427801038001001

42. Mueller, PS, Plevak, DJ, and Rummans, TA. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clinic Proc. (2001) 76:1225–35. doi: 10.4065/76.12.1225

43. Puchalski, CM, Blatt, B, Kogan, M, and Butler, A. Spirituality and health: the development of a field. Acad Med. (2014) 89:10–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000083

44. Riggs, DS, Caulfield, MB, and Street, AE. Risk for domestic violence: factors associated with perpetration and victimization. J Clin Psychol. (2000) 56:1289–316. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200010)56:10<1289::AID-JCLP4>3.0.CO;2-Z

45. Culliford, L. Spirituality and clinical care. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). (2002) 325:1434–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1434

46. Lucchetti, G, Koenig, HG, and Lucchetti, ALG. Spirituality, religiousness, and mental health: a review of the current scientific evidence. World J Clin Cases. (2021) 9:7620-7631. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7620

47. Kennedy, JE, Davis, RC, and Taylor, BG. Changes in spirituality and wellbeing among victims of sexual assault. J Sci Study Relig. (1998) 37:322–8. doi: 10.2307/1387531

48. Connor, KM, Davidson, JR, and Lee, LC. Spirituality, resilience, and anger in survivors of violent trauma: a community survey. J Trauma Stress. (2003) 16:487–94. doi: 10.1023/A:1025762512279

49. Brewer-Smyth, K, and Koenig, HG. Could spirituality and religion promote stress resilience in survivors of childhood trauma? Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2014) 35:251–6. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2013.873101

50. Hamby, S, Taylor, E, Mitchell, K, Jones, L, and Newlin, C. Poly-victimization, trauma, and resilience: exploring strengths that promote thriving after adversity. J Trauma Dissociation. (2020) 21:376–95. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2020.1719261

51. Hillis, S, Tucker, S, Baldonado, N, Taradaika, E, Bryn, L, Kharchenko, S, et al. The effectiveness of hope groups, a mental health, parenting support, and violence prevention program for families affected by the war in Ukraine: findings from a pre-post study. J Migr Health. (2024) 10:100251. doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2024.100251

52. Schafer, A, and Ndogoni, L. Mental health and spiritual well-being in humanitarian crises: the role of faith communities providing spiritual and psychosocial support during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Int Humanit Action. (2022) 7:21. doi: 10.1186/s41018-022-00127-w

53. Vinueza, MA. The role of spirituality in building up the resilience of migrant children in Central America: bridging the gap between needs and responses. Int J Childrens Spirit. (2017) 22:84–101. doi: 10.1080/1364436X.2016.1278359

54. Ismailbekova, A. Single mothers in Osh: well-being and coping strategies of women in the aftermath of the 2010 conflict in Kyrgyzstan. Focaal. (2015) 2015:114–27. doi: 10.3167/fcl.2015.710110

55. Pavlish, C. Action responses of Congolese refugee women. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2005) 37:10–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00010.x

56. Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. Liberating voices: the political implications of Palestinian mothers narrating their loss. Women's Stud Int Forum. (2003) 26:391–407. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2003.08.007

57. Sousa, CA, Akesson, B, and Siddiqi, M. Parental resilience in contexts of political violence: a systematic scoping review of 45 years of research. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2025) 26:41–57. doi: 10.1177/15248380241270048

58. Consortium on Nurturing Values and Spirituality in Early Childhood for the Prevention of Violence. Toolkit: nurturing the spiritual development of children in the early years: a contribution to the protection of children from violence and the promotion of their holistic wellbeing. (2022). Available online at: https://childspiritualdevelopment.org/2022/11/17/toolkit/ (Accessed July 20, 2024).

59. Engster, D, and Stensöta, HO. Do family policy regimes matter for children's well being? Soc Polit. (2011) 18:82–124. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxr006

60. Government of Malaysia. Laws of Malaysia child act. (2001). Available online at: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/child-act-2001-249784220/249784220 (Accessed February 10, 2025).

61. Kingdom of Bhutan. (2008). National Assembly of Bhutan. Constitution of Bhutan. Available online at: https://www.rcsc.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Constitution-of-Bhutan-Eng-2008.pdf (Accessed February 10, 2025).

62. Ministerio de Educacion, Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, Educacion Inicial en Familia Comunitaria Escolarizada, ViceMinisterio de Educacion Regular. (2014). Early childhood development early learning and development standards for children from 0-6 years. Available online at: https://www.minedu.gob.bo/files/publicaciones/ver/dgep/2021/Planes_y_Programas_Inicial_2021.pdf (Accessed February 10, 2025).

63. Government of Kenya Ministry of Education of State Department of Learning. School Readiness Tool (2022) and National Early Childhood Development Policy Framework (2006). Available online at: https://www.education.go.ke/sites/default/files/2022-12/Assessors%20guide.pdf; https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ressources/kenyaecdpolicyframework.pdf (Accessed February 10, 2025).

64. Government of Malawi, Ministry of Gender Children and Community Development (2009) National Strategic Plan for early childhood development 2009 – 2014. Available online at: https://www.medbox.org/document/national-strategic-plan-for-early-childhood-development-malawi-2009-2014 (Accessed February 10, 2025).

65. Government of Mauritius. Promoting early moral development through play. (2007). Available online at: https://openlab.bmcc.cuny.edu/ece-110-lecture/wp-content/uploads/sites/98/2019/11/Promoting-Moral-Development-through-play-during-early-childhood_1.pdf (Accessed February 10, 2025).

66. Government of Solomon Islands. Pre-primary year syllabus. (2018). Available online at: https://mehrd.gov.sb/documents?view=download&format=raw&fileId=17 (Accessed February 10, 2025).

67. Schopper, D, Lormand, JD, and Waxweiler, R. (Eds.). Developing policies to prevent injuries and violence: Guidelines for policy-makers and planners. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. (2006).

68. Backhaus, S, Leijten, P, Jochim, J, Melendez-Torres, GJ, and Gardner, F. Effects over time of parenting interventions to reduce physical and emotional violence against children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. (2023) 60:102003. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102003

69. Palm, S, and Eyber, C. Why faith? Engaging the mechanisms of faith to end violence against children. Learning brief (joint learning initiative on faith and local communities EVAC hub), (2019) p. 2.

70. Hess, S, Smith, S, and Umachandran, S. Faith as a complex system: Engaging with the faith sector for strengthened health emergency preparedness and response. Lancet Global Health. (2024) 12:e1750–1. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(24)00317-6

71. Bone, J, and Fenton, A. Spirituality and child protection in early childhood education: a strengths approach. Int J Children's Spirituality. (2015) 20:86–99. doi: 10.1080/1364436X.2015.1030594

72. Doty, JL, Girón, K, Mehari, KR, Sharma, D, Smith, SJ, Su, YW, et al. The dosage, context, and modality of interventions to prevent cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: a systematic review. Prev Sci. (2022) 23:523–37. doi: 10.1007/s11121-021-01314-8

73. Gaffney, H, Ttofi, MM, and Farrington, DP. Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: an updated meta-analytical review. Aggress Violent Behav. (2019) 45:111–33. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.001

74. Jones, LM, Mitchell, KJ, and Walsh, WA. A systematic review of effective youth prevention education: Implications for internet safety education. Durham, NH: Crimes Against Children Research Center (CCRC), University of New Hampshire (2014).

75. Lester, S, Lawrence, C, and Ward, CL. What do we know about preventing school violence? A systematic review of systematic reviews. Psychol Health Med. (2017) 22:187–223. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2017.1282616

76. United Nations General Assembly. Seventieth session. Agenda items 15 and 116 Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on Sept 25, 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development; (2015).

Keywords: positive spirituality, violence prevention, resilience, faith-based approaches, child maltreament

Citation: Van Tuyll Van Serooskerken Rakotomalala S, Anis K, Hillis S, Tucker S, Li X and Stok M (2025) The role of positive spirituality in preventing child maltreatment and promoting resilience: a perspective on policy and practice. Front. Public Health. 13:1656760. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1656760

Edited by:

Lisa K. Anderson-Shaw, Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University Chicago, United StatesReviewed by:

Emma Louise Giles, Teesside University, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Van Tuyll Van Serooskerken Rakotomalala, Anis, Hillis, Tucker, Li and Stok. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sabine Van Tuyll Van Serooskerken Rakotomalala, c2FiaW5ldkB3aG8uaW50

Sabine Van Tuyll Van Serooskerken Rakotomalala

Sabine Van Tuyll Van Serooskerken Rakotomalala Katy Anis2

Katy Anis2 Marijn Stok

Marijn Stok