- 1Department of Pediatric Infectious, Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 3Ministry of Education-Shanghai Key Laboratory of Children’s Environmental Health, Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 4Center for Reproductive Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Background: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposure is associated with various health risks. However, limited research has explored their potential connection with congenital heart disease (CHD).

Objective: This study aimed to investigate the relationship between different types of PFAS and childhood CHD using a mixed analysis approach.

Methods: A hospital-based case–control study was conducted involving 282 children with CHD and 282 control participants. Plasma samples were analyzed for 19 PFAS congeners. Logistic regression, Bayesian kernel-machine regression (BKMR), and weighted quantile sum (WQS) models were employed to assess the association between individual PFAS and PFAS mixtures with CHD risk.

Results: Analysis of 564 subjects revealed higher plasma concentrations of various PFAS compounds in the CHD-group. Logistic regression identified significant associations between CHD risk and specific PFAS, notably 6:2 Chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acid (6:2 Cl-PFESA) (OR = 1.65; 95%CI: 1.40–1.94), 8:2 8:2 Cl-PFESA (OR = 1.69; 95%CI: 1.69–2.19), Perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) (OR = 2.68; 95%CI: 2.28–3.15), Perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) (OR = 2.38; 95%CI: 1.77–3.22), Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) (OR = 2.62; 95%CI: 1.99–3.45), and Perfluorotetradecanoic acid (PFTeDA) (OR = 2.18; 95%CI: 1.81–2.63). BKMR analysis confirmed these findings. WQS analysis emphasized PFBA, 8:2 Cl-PFESA, PFHxA, and PFTeDA as key contributors to the association between PFAS mixture exposure and CHD risk.

Conclusion: Exposure to PFAS mixtures was associated with an increased risk of CHD in children, with 6:2 Cl-PFESA, 8:2 ClPFESA, PFBA, PFHxA, and PFTeDA playing significant roles.

1 Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) stand out among synthetic chemicals for their unique properties, including resistance to water and grease (1, 2). These characteristics have made them essential in a wide range of industrial and consumer products (1, 3). However, the pervasive use of PFAS has led to their widespread presence in the environment, sparking concerns over their persistence, tendency for bioaccumulation, and the potential for adverse health effects (4–7). Emerging research underscores associations between PFAS exposure and various health risks, encompassing cancer, immune dysfunction, reproductive disorders, liver damage, endocrine disruption, and developmental effects (4, 7–10). Additionally, evidence highlights PFAS’s link to cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adults (11, 12), yet further investigation is needed to discern its impact, particularly on congenital heart disease (CHD) in children.

CHD encompasses a spectrum of structural heart anomalies present from birth, affecting approximately 1% of newborns worldwide (13, 14). The ramifications of CHD are significant, impacting not only patients but also their families and healthcare systems (15). The condition often necessitates surgical and long-term medical interventions and is associated with numerous comorbidities. Identifying environmental contributors to CHD is imperative for crafting effective prevention and public health measures. PFAS, as environmental endocrine disruptors, may interfere with normal endocrine function, particularly during crucial stages of fetal heart development, potentially resulting in structural and congenital heart anomalies (12, 16, 17). Mechanisms may involve alterations in hormonal pathways, disruption of cellular signaling, and changes in gene expression crucial for heart development (17–19).

While existing research has provided valuable insights into the association between PFAS exposure and CVD in adults, there remains a substantial gap in understanding the impact of PFAS on childhood CHD (12, 20, 21). Prior studies have predominantly focused on legacy PFAS compounds, employing simplistic regression analysis methods that fail to comprehensively explore the complex mixture of PFAS exposure (22–24). Moreover, the existing research has largely overlooked the potential distinct or heightened effects of newer alternatives and branched isomers of PFAS. This oversight is concerning given the evolving landscape of PFAS usage, where traditional compounds are being phased out in favor of alternatives with yet-to-be-fully-understood long-term health impacts (25, 26).

Recognizing these limitations, there is an urgent need for more comprehensive investigations into the broad spectrum of PFAS compounds and their roles in influencing childhood CHD. Therefore, this study aims to address this gap through a hospital-based case–control design, employing innovative statistical methods to explore mixed exposure to PFAS. By elucidating the main contributors to these associations, our study seeks to uncover the environmental determinants of childhood CHD, providing insights crucial for informing future preventive strategies and public health interventions.

2 Methods and materials

2.1 Study population

Our research focused on children diagnosed with CHD and matched controls without CHD, recruited from Xinhua Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China. The CHD group was recruited from cases that underwent cardiac surgery in our pediatric heart center between June 2021 and September 2023. The recruitment process and blood collection were done before the cardiac surgery to avoid the perioperative impact on samples, such as blood transfusion. The inclusion criteria for the CHD group were all types of congenital heart defects, excluding cases associated with other malformations or known chromosomal abnormalities.

The control group was recruited from the outpatient for children’s healthcare during the same period. The inclusion criteria for the control group were healthy children without known systemic diseases or chromosomal abnormalities. The cardiac evaluation was determined by transthoracic echocardiography in a tertiary hospital. Nearly twice the number of the control group was recruited to ensure a sufficient number for matching the case group. After recruitment, an equal number of participants were matched to balance the case and control groups based on key demographic factors (age, sex and race). Supplementary Figure S1 outlines the recruitment process.

A total of 282 children with CHD and an equal number of controls were selected through rigorous screening and clinical evaluations, ensuring demographic (age and sex) compatibility to strengthen the study’s validity. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Xinhua Hospital (Approval no. XHEC-NSFC-2022-070).

2.2 PFAS measurements

Upon enrollment, blood samples were collected and immediately processed, then stored at −80 °C to maintain integrity and prevent degradation. We analyzed these samples for a panel of 19 PFAS congeners, including traditional and emerging PFAS, using ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) paired with triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). This method provided the sensitivity and specificity required for precise PFAS quantification. Reference standards for all PFAS were sourced from Wellington Laboratories to ensure measurement accuracy (see Table 1).

2.3 Pretreatment of PFAS

Before assessing PFAS levels, we implemented a detailed pretreatment protocol. Briefly, a 0.1 mL plasma was spiked with 2 ng internal standard mixture, then 1 mL of 0.1 M formic acid was used. Sample extraction and cleanup were performed using Oasis-HLB cartridges (3 mL/150 mg; Waters Inc., Milford, MA, USA). Before sample loading, the solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges were conditioned with 1 mL MeOH followed by 1 mL of 0.1 M formic acid. The plasma samples were then loaded onto cartridges, rinsed with 1 mL of 0.1 M formic, 3 mL 0.1 M formic acid/MeOH (4:1, v/v) and 0.5 mL water (1% ammonium acetate). After 30 min of vacuum dried, the target substances were eluted with 1.8 mL of ACN (1% ammonium acetate). The final eluent was collected, concentrated and then reconstituted with 0.1 mL MeOH/water (7:3; v/v) for ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) analysis. This procedure, validated by calibration curves showing excellent linearity (R2 > 0.99), ensured the removal of impurities, enhancing subsequent PFAS measurement accuracy and reliability. The obtained matrix spiked recoveries ranged from 81.5% (PFDS) to 116% (N-EtFOSAA). The limits of detection (LODs) ranged from 0.0005 for Σ3,4,5 m-PFOS to 0.012 ng/mL for PFHpA.

2.4 Instrument analysis

Instrumental analysis employed UPLC-MS/MS, specifically the Agilent 1,290 Infinity Series HPLC system paired with the Agilent 6,495 C triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Operated in electrospray ionization (ESI) negative ion mode, this setup optimized sensitivity and precision. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a ZORBAX RRHD Eclipse Plus C18 column, complemented by a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 guard column, with conditions maintained at 40 °C. A precise injection volume of 0.005 mL and a gradient elution program involving milli-Q water with ammonium acetate and methanol facilitated efficient separation of PFAS congeners. The source temperature was set at 375 °C and flow of the sheath gas15 L min−1. The nebulizer gas was set at 35 psi and the capillary voltage was −3,500 V. The mass spectrometer was performed in the electrospray ionization (ESI) negative ion multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode.

2.5 Quality assurance and quality control

Our study maintained rigorous quality assurance and control (QA/QC) protocols to ensure analytical accuracy. We regularly introduced solvent blanks and analyzed control samples to monitor instrument impurity and background contamination. For every 21 samples, one procedural blank (ultrapure water), one matrix blank (sheep plasma) and two matrix spiked controls (1 ng/mL and 10 ng/mL) were checked. The final concentration of PFAS was determined by subtracting the level of matrix blanks. Quality control samples at low and high spiked levels were periodically analyzed to assess method stability. Comprehensive precautions, including the use of methanol-rinsed polypropylene tubes and continuous solvent injection, minimized potential contamination. We established strict inclusion criteria for PFAS congeners based on detection rates and set precise limits of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ), ensuring reliable concentration estimates for PFAS analysis. The LODs for PFAS ranged from 0.0003 to 0.015 ng/mL. Recoveries for all target compounds were within 82.0–118.2%, and relative standard deviations (RSDs) were < 20%. These exhaustive QA/QC measures reinforced the study’s analytical integrity, contributing to the generation of high-quality data for informed scientific conclusions.

2.6 Statistical analysis

In our study, we employed standard statistical methodologies to explore the intricate relationships between PFAS exposure and the risk of CHD in children. Initially, we conducted descriptive statistical analysis, presenting continuous variables as medians with interquartile ranges and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Differences in PFAS levels across groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, while categorical variables underwent analysis using the chi-square test. To ensure data comparability and account for potential non-linear relationships, PFAS concentration data were transformed using a logarithmic scale. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were then utilized to assess correlations among log-transformed PFAS concentrations.

To investigate the association between individual PFAS exposures and the risk of CHD, logistic regression analysis was employed, adjusting for age and sex. Given the potential for non-linear associations, we utilized restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis with three strategically placed nodes. This approach allows for flexible modeling of non-linear relationships by fitting cubic polynomial functions within defined intervals of the predictor variable range (27). By incorporating logistic regression and RCS analysis, we conducted a comprehensive examination of the complex dynamics between PFAS exposure and CHD risk, adjusting for relevant covariates to ensure statistical robustness.

We applied the Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR) model to assess the health impacts of mixed PFAS exposures. BKMR is adept at elucidating individual and combined effects of multiple pollutants on health outcomes, capturing potentially non-linear and interactive exposure relationships using a kernel function (28). The BKMR model’s reliability was ensured through the use of 20,000 MCMC iterations, which serve as an internal cross-validation mechanism, assessing the stability and consistency of our findings. PFAS data were log-transformed and standardized (z-score normalization) to ensure comparability. The BKMR model, adjusted for covariates such as age and sex, utilized the Posterior Inclusion Probability (PIP) criterion to determine the significance of specific PFAS compounds in relation to CHD risk, with parameter estimation achieved through 20,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations.

Furthermore, we explored the Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) regression method to examine the collective impact of mixed exposures. By categorizing PFAS concentrations into quartiles and assigning weights to each exposure within a WQS index, this method quantified each compound’s contribution to CHD risk (29). The reliability of estimated weights was validated through 200 bootstrap samples, each subjected to regression analysis to discern the WQS index’s association with CHD risk. Adjustments for covariates such as age and sex were made to provide insights into the cumulative effect of PFAS exposure on CHD risk.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software, with the “rms,” “bkmr,” and “gWQS” packages utilized for model implementations. Statistical significance was established at a p-value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed), ensuring the scientific rigor and reliability of our findings.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive analysis

A total of 564 subjects were included in this study, consisting of 282 individuals in the CHD group and 282 in the control group (Supplementary Table S1). The mean age of the population was 7.3 years (±2.3), with a slightly lower mean age observed in the CHD group (7.1 ± 2.5 years) compared to the control group (7.5 ± 2.1 years). Gender distribution was comparable between both groups, with 62.1% boys and 37.9% girls overall, and nearly equal proportions within each group: 63.1% boys and 36.9% girls in the CHD group, compared to 61.0% boys and 39.0% girls in the control group. This demographic balance minimizes potential confounding variables related to age and sex, providing a robust foundation for subsequent exposure risk assessment. Some PFAS concentrations exhibited significant correlations with each other, with Spearman correlation coefficients ranging from −0.09 to 0.93 (Supplementary Figure S2).

Table 2 presents a comprehensive comparison of plasma PFAS levels between CHD cases and controls. Significant differences between the two groups are apparent for several PFAS compounds. For instance, 6:2 Cl-PFESA levels are notably higher in the CHD group (p < 0.001), with a mean of 2.789 ng/mL compared to 1.091 ng/mL in controls. Similarly, PFBA shows a pronounced disparity, with a CHD group mean of 0.223 ng/mL against a mean of 0.024 ng/mL in the control group (p < 0.001). This trend of higher PFAS concentrations in the CHD group is also evident with 8:2 ClPFESA (p < 0.001), PFBS (p < 0.001), PFHxA (p < 0.001), PFPeA (Perfluoropentanoic acid) (p < 0.001), and PFTeDA (p < 0.001), among others, all exhibiting statistically significant differences. Conversely, certain compounds such as PFDA (Perfluorodecanoic acid)(p = 0.197), n-PFHxS (Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid) (p = 0.810), PFNA (Perfluorononanoic acid) (p = 0.220), n-PFOS (Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid) (p = 0.095), PFUdA (Perfluoroundecanoic acid) (p = 0.761), 6 m-PFOS (6-mono-perfluorooctane sulfonic acid) (p = 0.187), 345 m-PFOS (3,4,5-mono-perfluorooctane sulfonic acid) (p = 0.958), and 1 m-PFOS (1-mono-perfluorooctane sulfonic acid) (p = 0.030) did not show statistically significant differences between the CHD group and controls.

3.2 Logistic regression analysis

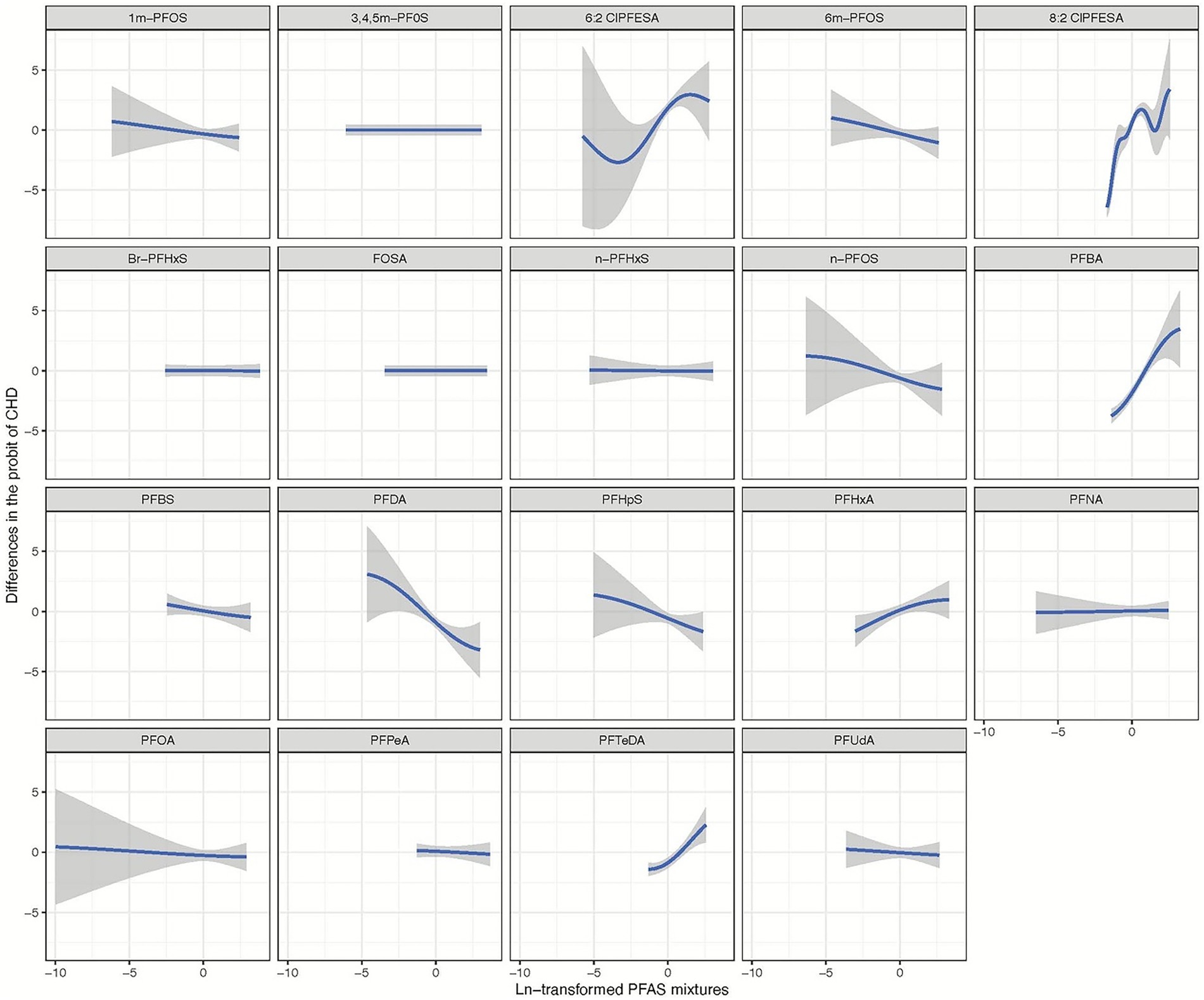

Logistic regression identified significant associations between CHD risk and specific PFAS. For instance, the odds ratio (OR) for 6:2 Cl-PFESA is 1.65 (95% CI: 1.40, 1.94), indicating a 65% increase in CHD risk for each unit increase in the ln-transformed concentration of this compound. Similarly, 8:2 Cl-PFESA shows an OR of 1.92 (95% CI: 1.69, 2.19), representing a 92% increase in risk. PFBA, PFBS, PFHxA, and PFTeDA exhibit substantial ORs of 2.68, 2.38, 2.62, and 2.18, respectively, indicating strong associations with CHD risk (p < 0.001). Conversely, PFDA, PFUdA, 6 m-PFOS, 345 m-PFOS, and 1 m-PFOS demonstrate ORs close to 1 and non-significant p-values, suggesting no strong evidence of an association with CHD risk for these compounds (Table 3). Furthermore, the RCS curve depicted in Figure 1 illustrates a nonlinear relationship between PFOS and the risk of heart disease. Notably, these curves predominantly display an approximately linear shape or an inverted J-shaped pattern, signifying a notable escalation in the risk of heart disease with increasing concentrations of the compound.

Table 3. Associations of ln-transformed PFAS with the risk of congenital heart disease in logistic regression model (n = 564).

Figure 1. RCS curve analysis of the association between various PFAS compounds (ln-transformed) and the risk of congenital heart disease. The graph presents restricted cubic spline (RCS) curves illustrating the association between a range of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and the risk of congenital heart disease. Each subplot represents a different PFAS compound, with the x-axis showing the log-transformed concentration of PFAS in plasma, and the y-axis displaying the odds ratio (OR) for congenital heart disease risk along with its 95% confidence interval (CI). The red shaded area indicates the range of the confidence interval. These curves reveal the nonlinear relationships between plasma PFAS concentrations and congenital heart disease risk.

3.3 Bayesian kernel machine regression analysis

Figure 2 illustrates the comprehensive joint associations of PFAS mixture exposure with the risk of CHD as evaluated by BKMR. This trend suggests that higher levels of PFAS mixture exposure are significantly associated with an increased risk of CHD. Additionally, The BKMR model identified significant contributors to the overall association, including 6:2 Cl-PFESA, 8:2 Cl-PFESA, PFBA, PFHxA, and PFTeDA, all with PIPs of 1.00. A PIP of 1.00 indicates that these variables were consistently included in all iterations of the model, suggesting their strong and reliable association with CHD risk (refer to Figure 3; Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2. Comprehensive joint associations of PFAS mixture (ln-transformed) with the risk of congenital heart disease, evaluated via Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR) (n = 564). All estimates adjusted for age (continuous) and sex (categorical). This figure illustrates the estimated difference in the probit of congenital heart disease across specific exposure percentiles (x-axis) compared to when all exposures are at the 50th percentile.

Figure 3. Univariate exposure-response relationship of individual ln-transformed PFAS with the risk of congenital heart disease, estimated by Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR) for each PFAS, with the other pollutants fixed at the median (n = 943). All estimates were adjusted for age (continuous), sex (categorical). The boundaries of the gray areas represent the 95% CIs of the exposure-response relationship.

3.4 Weighted quantile sum regression

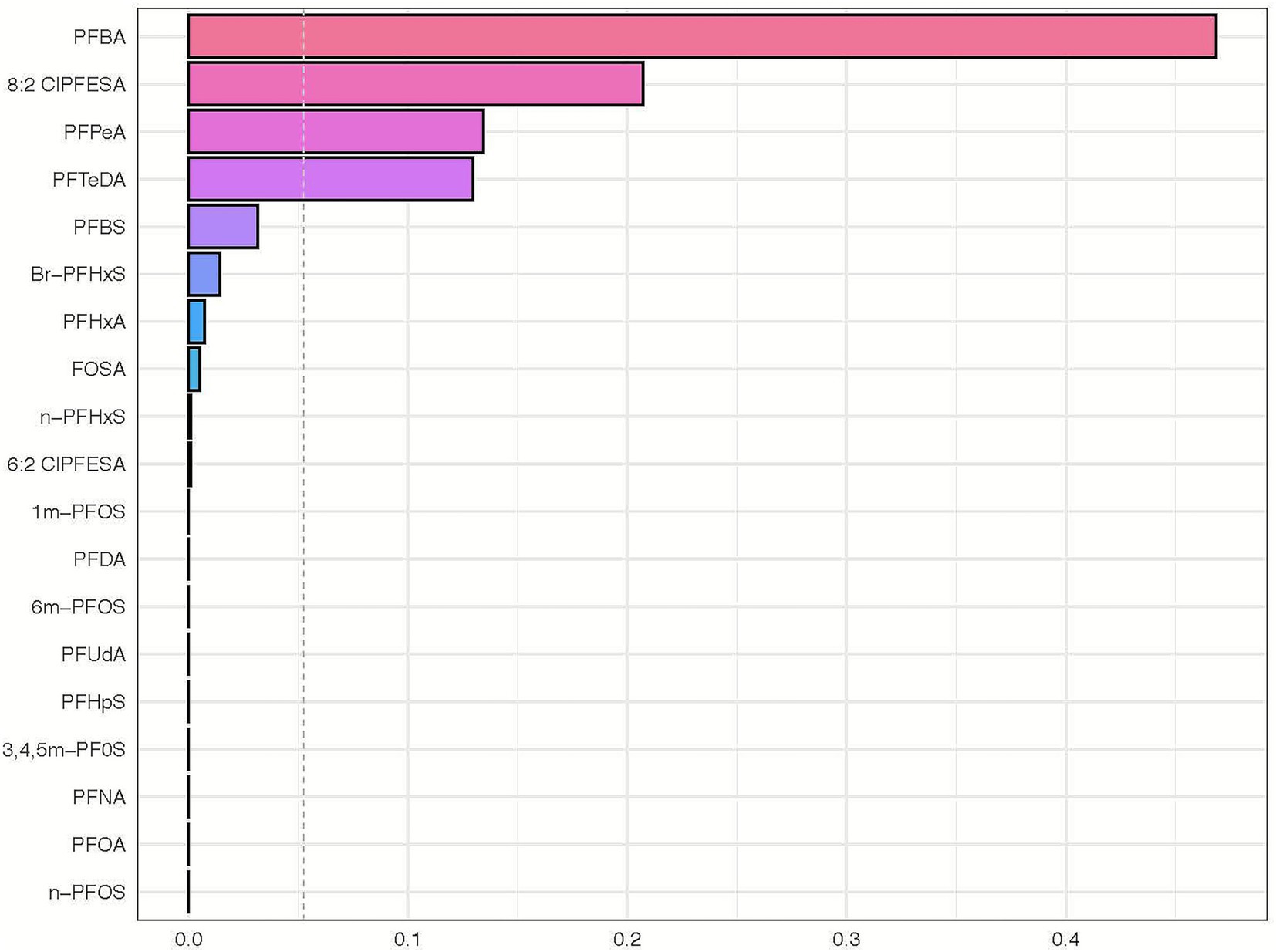

The results of the WQS analysis are presented in Figure 4. Overall, PFAS mixture exposure was associated with an increased risk of CHD, with an odds ratio of 3.49 (Standard Error: 0.25, q < 0.001) for each quantile of PFAS concentration. In our WQS regression analysis, the OR of 3.49 represents the increase in the odds of CHD associated with a one-quartile increase in the weighted sum of PFAS exposures. Specifically, this means that for each quartile increase in the overall PFAS mixture exposure (as quantified by the WQS index), the odds of CHD increase by 249% (OR-1 = 2.49, or 249%), after adjusting for covariates. The weights assigned to each PFAS compound in the WQS model represent their relative importance in the mixture’s association with CHD risk. These weights were consistently distributed across quantiles, with PFBA consistently receiving the highest weight (mean weight: 0.436), followed by 8:2 Cl-PFESA (0.256), PFTeDA (0.123), and PFHxA (0.101). This distribution remained stable across bootstrap iterations, suggesting a robust pattern of relative importance among the PFAS compounds. (refer to Figure 4; Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 4. Weighted quantile sum regression analysis of PFAS mixture exposure and its association with congenital heart disease. This horizontal bar chart represents the weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression analysis outcomes of various perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in relation to the risk of congenital heart disease. Each bar corresponds to a specific PFAS compound, with the length of the bar indicating the weight in the WQS index. The chart reveals the relative contribution of each PFAS compound to the overall risk of congenital heart disease as determined by the gWQS regression technique. Compounds with longer bars have a higher weighted impact in the model, suggesting a more significant association with the risk of congenital heart disease.

4 Discussion

This investigation underscores the association of various PFAS compounds, including traditional and emerging ones, with CHD incidence in children. Specifically, 6:2 Cl-PFESA, 8:2 Cl-PFESA, PFBA, PFHxA, and PFTeDA emerged as significant factors in this association. These findings highlight the importance of considering the full range of PFAS compounds to fully understand the health effects of environmental exposure. The strength of our study lies in its constructed hospital-based case–control design. While multiple PFAS compounds were analyzed using advanced statistical methods, our analyses enhance understanding of their potential health effects. These insights represent a crucial addition to the growing body of evidence linking PFAS exposure to harmful cardiovascular effects, providing valuable guidance for developing public health policies and initiatives aimed at reducing exposure and preventing CHD in children.

Our study expands upon existing research by investigating the association between PFAS exposure and cardiovascular disease, specifically focusing on CHD in children. While previous studies concentrated on traditional PFAS, our research broadens the scope to include emerging compounds, enhancing understanding of their impact on cardiovascular health, particularly childhood CHD. We conducted a hospital-based case–control study involving 282 children with CHD and an equal number of controls, meticulously analyzing plasma samples for 19 PFAS compounds, encompassing long-chain and short-chain PFAS, as well as emerging alternatives and branched-chain isomers. Utilizing two multi-pollutant models (WQS and BKMR), we assessed the association between individual PFAS and PFAS mixtures with CHD. Both models consistently indicated a positive correlation, suggesting that exposure to a combination of PFAS compounds may increase CHD risk in children. After adjusting for other PFAS congeners, five specific compounds, 6:2 Cl-PFESA, 8:2 Cl-PFESA, PFBA, PFHxA, and PFTeDA, emerged as major contributors to the association between PFAS mixtures and CHD, implying significant roles for these compounds in CHD development.

Our findings are consistent with previous research, including two Chinese studies suggesting that gestational exposure to most PFAS is associated with a higher risk of CHD (20, 23). However, a comparison of the specific PFAS species involved reveals important differences. The studies by Li et al. (20) and Ou et al. (23) primarily identified long-chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs), whereas our study, in addition to some long-chain compounds (PFTeDA), identified significant roles for emerging alternatives (e.g., 6:2 and 8:2 Cl-PFESA) and short-chain PFAS (e.g., PFBA, PFHxA). The widespread presence of PFAS in the environment, detectable in air, water, soil, and human blood, underscores their bioaccumulative potential and raises significant public health concerns regarding their long-term impact. This study reinforces the association between PFAS exposure and cardiovascular pathology and underscores the urgent need for a comprehensive investigation into the impact of a broader range of PFAS compounds, especially on vulnerable groups such as children.

The mechanisms through which PFAS contribute to CHD development remain unclear but may involve several potential pathways. One notable mechanism is endocrine disruption, where PFAS interfere with critical hormone regulation, such as thyroid hormones essential for heart development (17, 30, 31). Disruptions in thyroid hormone levels during fetal development stages could lead to structural heart abnormalities, increasing CHD risk (32, 33). Another proposed pathway involves oxidative stress and inflammation (9, 34, 35). PFAS trigger oxidative stress by disrupting the balance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and the body’s antioxidative defenses, leading to cellular and tissue damage, including in the developing heart (9, 36). Additionally, PFAS can activate inflammatory pathways, exacerbating tissue damage and hindering normal heart formation (19, 37). PFAS are also implicated in altering lipid metabolism, leading to dyslipidemia—a recognized risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including CHD (38, 39). Furthermore, disturbances in calcium homeostasis, crucial for cardiac muscle function, may result from PFAS exposure, potentially leading to abnormal heart rhythms and compromised cardiac function, further increasing CHD risk (12, 19). PFAS exposure has also been associated with changes in the expression of genes crucial for cardiac development, potentially directly contributing to structural heart abnormalities and elevated CHD risk (23, 40–42) 6:2 Cl-PFESA.

These mechanisms are likely interrelated and may collectively influence CHD development. Additionally, the impact of specific PFAS compounds and the timing of exposure during developmental stages may dictate the extent and nature of these effects. In summary, PFAS contribute to childhood CHD development through multiple intertwined pathways. Legacy long-chain PFASs contributed mostly to endocrine disruption, and short-chain PFASs were more strongly linked to its potential to induce oxidative stress and disrupt mitochondrial function. While the chlorinated PFASs (6:2 and 8:2 Cl-PFESA) are likely related to endocrine disruption, the disruption of calcium homeostasis and gene expression changes. Further research is essential to elucidate these complex interactions and their implications for child health.

Our study findings have significant implications for both public health policy and clinical practice. The established association between PFAS exposure and increased CHD risk in children calls for a reassessment of public health strategies and regulatory measures to limit environmental exposure to these substances, especially among vulnerable groups like children. Additionally, our findings emphasize the need for comprehensive risk assessments and regulatory policies covering the full spectrum of PFAS chemicals. By identifying specific contributors, we offer actionable insights for crafting targeted public health interventions aimed at reducing environmental exposure to these chemicals and mitigating associated pediatric cardiovascular risk. In the clinical domain, our findings are equally important. Healthcare practitioners should integrate our insights into their risk assessment protocols and patient care strategies, recognizing the potential impact of PFAS exposure on pediatric cardiac development. Enhanced understanding of how environmental factors like PFAS contribute to CHD can inform clinical decision-making and patient management, leading to improved outcomes for affected individuals. It is imperative for healthcare providers to consider environmental determinants of CHD to facilitate early detection and intervention, ensuring optimal care provision for children with or at risk of this condition. Furthermore, our study lays the foundation for future research to investigate the mechanisms underlying PFAS exposure’s effects on cardiovascular health and its long-term implications. This knowledge is crucial for refining risk assessment methodologies and developing precise preventive measures, thereby enhancing public health strategies and individual patient care on a broader scale.

While our study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design restricts our ability to establish a causal relationship between PFAS exposure and CHD onset. Prospective longitudinal studies are necessary to validate our findings and determine causality. Secondly, our research focused on a specific population within China, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results to other geographical areas and demographic groups. Additionally, our study encountered limitations regarding data availability, particularly in assessing other influential factors such as genetic predispositions or concurrent environmental exposures that could influence the PFAS-CHD relationship. Furthermore, data on potential confounders like maternal exposures during pregnancy, specific dietary patterns, and detailed family socioeconomic status were not available. These unexplored confounders may impact the observed associations, underscoring the importance of comprehensive data collection in future investigations. Finally, the intricate mechanisms by which PFAS exposure affects childhood CHD development remain incompletely understood. Future research should strive to elucidate these mechanisms, providing a clearer understanding of the biological basis of PFAS-related cardiac anomalies.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, our study underscores the observed association between PFAS exposure and increased CHD risk in children, with specific focus on the impact of 6:2 Cl-PFESA, 8:2 Cl-PFESA, PFBA, PFHxA, and PFTeDA. Utilizing advanced statistical methods, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of various PFAS compounds, identifying key contributors and providing suggestive evidence for this critical association. These findings underscore the urgency of implementing stringent regulations on PFAS to safeguard public health. Moving forward, research efforts should prioritize unraveling the mechanisms linking PFAS exposure to CHD, enabling the development of targeted interventions aimed at reducing exposure and preventing adverse health outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics committee of Xinhua Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

XJ: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. LZ: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. YX: Writing – original draft, Data curation. JG: Validation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. WT: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. YW: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. LY: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JH: Resources, Writing – review & editing. YG: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. KS: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. SC: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773411 and No. 82300269), the project of cultivation for multidisciplinary treatment in critical illness by Shanghai health commission (No. Z155080000004).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1657168/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Gluge, J, Scheringer, M, Cousins, IT, DeWitt, JC, Goldenman, G, Herzke, D, et al. An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ Sci Process Impacts. (2020) 22:2345–73. doi: 10.1039/D0EM00291G

2. Kotthoff, M, Muller, J, Jurling, H, Schlummer, M, and Fiedler, D. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in consumer products. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2015) 22:14546–59. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4202-7

3. Dhore, R, and Murthy, GS. Per/polyfluoroalkyl substances production, applications and environmental impacts. Bioresour Technol. (2021) 341:125808. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125808

4. Fenton, SE, Ducatman, A, Boobis, A, DeWitt, JC, Lau, C, Ng, C, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance toxicity and human health review: current state of knowledge and strategies for informing future research. Environ Toxicol Chem. (2021) 40:606–30. doi: 10.1002/etc.4890

5. Maddela, NR, Ramakrishnan, B, Kakarla, D, Venkateswarlu, K, and Megharaj, M. Major contaminants of emerging concern in soils: a perspective on potential health risks. RSC Adv. (2022) 12:12396–415. doi: 10.1039/D1RA09072K

6. Ojo, AF, Peng, C, and Ng, JC. Assessing the human health risks of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: a need for greater focus on their interactions as mixtures. J Hazard Mater. (2021) 407:124863. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124863

7. Sunderland, EM, Hu, XC, Dassuncao, C, Tokranov, AK, Wagner, CC, and Allen, JG. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. (2019) 29:131–47. doi: 10.1038/s41370-018-0094-1

8. Blake, BE, and Fenton, SE. Early life exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and latent health outcomes: a review including the placenta as a target tissue and possible driver of peri- and postnatal effects. Toxicology. (2020) 443:152565. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2020.152565

9. Bonato, M, Corra, F, Bellio, M, Guidolin, L, Tallandini, L, Irato, P, et al. PFAS environmental pollution and antioxidant responses: an overview of the impact on human field. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:8020. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218020

10. Zeng, Z, Song, B, Xiao, R, Zeng, G, Gong, J, Chen, M, et al. Assessing the human health risks of perfluorooctane sulfonate by in vivo and in vitro studies. Environ Int. (2019) 126:598–610. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.002

11. Lind, PM, and Lind, L. Are persistent organic pollutants linked to lipid abnormalities, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease? A review. J Lipid Atheroscler. (2020) 9:334–48. doi: 10.12997/jla.2020.9.3.334

12. Meneguzzi, A, Fava, C, Castelli, M, and Minuz, P. Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl chemicals and cardiovascular disease: experimental and epidemiological evidence. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2021) 12:706352. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.706352

13. Liu, Y, Chen, S, Zuhlke, L, Black, GC, Choy, MK, Li, N, et al. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970-2017: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int J Epidemiol. (2019) 48:455–63. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz009

14. van der Linde, D, Konings, EE, Slager, MA, Witsenburg, M, Helbing, WA, Takkenberg, JJ, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 58:2241–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025

15. Hoffman, J. The global burden of congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc J Afr. (2013) 24:141–5. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2013-028

16. Basak, S, Das, MK, and Duttaroy, AK. Plastics derived endocrine-disrupting compounds and their effects on early development. Birth Defects Res. (2020) 112:1308–25. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1741

17. Hall, JM, and Greco, CW. Perturbation of nuclear hormone receptors by endocrine disrupting chemicals: mechanisms and pathological consequences of exposure. Cells. (2019) 9:13. doi: 10.3390/cells9010013

18. Kim, S, Thapar, I, and Brooks, BW. Epigenetic changes by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ Pollut. (2021) 279:116929. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116929

19. Wen, ZJ, Wei, YJ, Zhang, YF, and Zhang, YF. A review of cardiovascular effects and underlying mechanisms of legacy and emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Arch Toxicol. (2023) 97:1195–245. doi: 10.1007/s00204-023-03477-5

20. Li, S, Wang, C, Yang, C, Chen, Y, Cheng, Q, Liu, J, et al. Prenatal exposure to poly/perfluoroalkyl substances and risk for congenital heart disease in offspring. J Hazard Mater. (2024) 469:134008. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.134008

21. Mattsson, K, Rignell-Hydbom, A, Holmberg, S, Thelin, A, Jonsson, BA, Lindh, CH, et al. Levels of perfluoroalkyl substances and risk of coronary heart disease: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Environ Res. (2015) 142:148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.06.033

22. Gaston, SA, Birnbaum, LS, and Jackson, CL. Synthetic chemicals and Cardiometabolic health across the life course among vulnerable populations: a review of the literature from 2018 to 2019. Curr Environ Health Rep. (2020) 7:30–47. doi: 10.1007/s40572-020-00265-6

23. Ou, Y, Zeng, X, Lin, S, Bloom, MS, Han, F, Xiao, X, et al. Gestational exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and congenital heart defects: a nested case-control pilot study. Environ Int. (2021) 154:106567. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106567

24. Rappazzo, KM, Coffman, E, and Hines, EP. Exposure to perfluorinated alkyl substances and health outcomes in children: a systematic review of the epidemiologic literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:691. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070691

25. Ateia, M, Maroli, A, Tharayil, N, and Karanfil, T. The overlooked short- and ultrashort-chain poly- and perfluorinated substances: a review. Chemosphere. (2019) 220:866–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.186

26. Guelfo, JL, Korzeniowski, S, Mills, MA, Anderson, J, Anderson, RH, Arblaster, JA, et al. Environmental sources, chemistry, fate, and transport of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl substances: state of the science, key knowledge gaps, and recommendations presented at the august 2019 SETAC focus topic meeting. Environ Toxicol Chem. (2021) 40:3234–60. doi: 10.1002/etc.5182

27. Desquilbet, L, and Mariotti, F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. (2010) 29:1037–57. doi: 10.1002/sim.3841

28. Bobb, JF, Claus Henn, B, Valeri, L, and Coull, BA. Statistical software for analyzing the health effects of multiple concurrent exposures via Bayesian kernel machine regression. Environ Health. (2018) 17:67. doi: 10.1186/s12940-018-0413-y

29. Carrico, C, Gennings, C, Wheeler, DC, and Factor-Litvak, P. Characterization of weighted quantile sum regression for highly correlated data in a risk analysis setting. J Agric Biol Environ Stat. (2015) 20:100–20. doi: 10.1007/s13253-014-0180-3

30. Coperchini, F, Croce, L, Ricci, G, Magri, F, Rotondi, M, Imbriani, M, et al. Thyroid disrupting effects of old and new generation PFAS. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2020) 11:612320. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.612320

31. Mokra, K. Endocrine disruptor potential of short- and Long-chain Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)-a synthesis of current knowledge with proposal of molecular mechanism. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:2148. doi: 10.3390/ijms22042148

32. Razvi, S, Jabbar, A, Pingitore, A, Danzi, S, Biondi, B, Klein, I, et al. Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular function and diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 71:1781–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.045

33. von Hafe, M, Neves, JS, Vale, C, Borges-Canha, M, and Leite-Moreira, A. The impact of thyroid hormone dysfunction on ischemic heart disease. Endocr Connect. (2019) 8:R76–90. doi: 10.1530/EC-19-0096

34. Chen, JC, Baumert, BO, Li, Y, Li, Y, Pan, S, Robinson, S, et al. Associations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides, and polybrominated diphenyl ethers with oxidative stress markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. (2023) 239:117308. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.117308

35. Iqubal, A, Ahmed, M, Ahmad, S, Sahoo, CR, Iqubal, MK, and Haque, SE. Environmental neurotoxic pollutants: review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2020) 27:41175–98. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10539-z

36. Omoike, OE, Pack, RP, Mamudu, HM, Liu, Y, Strasser, S, Zheng, S, et al. Association between per and polyfluoroalkyl substances and markers of inflammation and oxidative stress. Environ Res. (2021) 196:110361. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110361

37. Wielsoe, M, Long, M, Ghisari, M, and Bonefeld-Jorgensen, EC. Perfluoroalkylated substances (PFAS) affect oxidative stress biomarkers in vitro. Chemosphere. (2015) 129:239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.10.014

38. Liu, B, Zhu, L, Wang, M, and Sun, Q. Associations between per- and Polyfluoroalkyl substances exposures and blood lipid levels among adults-a Meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect. (2023) 131:56001. doi: 10.1289/EHP11840

39. Wu, B, Pan, Y, Li, Z, Wang, J, Ji, S, Zhao, F, et al. Serum per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and abnormal lipid metabolism: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Environ Int. (2023) 172:107779. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2023.107779

40. Dunder, L, Salihovic, S, Lind, PM, Elmstahl, S, and Lind, L. Plasma levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are associated with altered levels of proteins previously linked to inflammation, metabolism and cardiovascular disease. Environ Int. (2023) 177:107979. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2023.107979

41. Starling, AP, Liu, C, Shen, G, Yang, IV, Kechris, K, Borengasser, SJ, et al. Prenatal exposure to per- and Polyfluoroalkyl substances, umbilical cord blood DNA methylation, and cardio-metabolic indicators in newborns: the healthy start study. Environ Health Perspect. (2020) 128:127014. doi: 10.1289/EHP6888

Keywords: per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, congenital heart disease, mixed analysis, Bayesian kernel-machine regression, weighted quantile sum

Citation: Jiao X, Zhao L, Xu Y, Gao J, Tang W, Wu Y, Yang L, Huang J, Guo Y, Sun K and Chen S (2025) Environmental exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and childhood congenital heart disease: a mixed analysis. Front. Public Health. 13:1657168. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1657168

Edited by:

Xinming Wang, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Pramita Sharma, University of Burdwan, IndiaZicheng Su, The University of Queensland, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Jiao, Zhao, Xu, Gao, Tang, Wu, Yang, Huang, Guo, Sun and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sun Chen, Y2hlbnN1bkB4aW5odWFtZWQuY29tLmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

Xianting Jiao

Xianting Jiao Liqing Zhao

Liqing Zhao Yuejuan Xu2†

Yuejuan Xu2† Yi Guo

Yi Guo Kun Sun

Kun Sun Sun Chen

Sun Chen