- 1Prevention Research Center, School of Public Health, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 2Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 3Department of Health Systems and Population Health, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, WA, United States

- 4Center for Dissemination and Implementation in the Institute for Public Health, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 5Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center and Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States

Introduction: Chronic diseases are a leading public health concern in the Americas, and physical inactivity contributes significantly to their burden. Open streets program—community initiatives that temporarily close urban streets to vehicles—promote physical activity and community engagement, demonstrating positive health and social impacts. Effective implementation depends on identifying suitable strategies and frameworks. The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy, developed for clinical/healthcare contexts, has not been widely assessed for community-based interventions such as Open Streets. Implementation strategies could lead to specific outcomes (e.g., adoption, sustainability) that differ from program outcomes (e.g., PA levels, chronic disease prevalence). This scoping review focuses on the strategies that influence implementation outcomes. The primary aims of this review were to (1) identify implementation strategies for Open Streets programs and (2) identify opportunities for Open Streets programs to promote chronic disease prevention and physical activity, specifically in the Americas.

Methods: A scoping review was conducted using Joanna Briggs Institute methodology and PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Six databases (PubMed, Scopus, Scielo, Web of Science, TRIS, and LILACS) were searched for studies on Open Streets programs in the Americas (January 2004–April 2024). Three reviewers independently screened studies in Rayyan. Strategies were extracted and coded according to the 73 ERIC taxonomy strategies. Quality appraisal used MMAT for empirical studies, AMSTAR-2 for reviews, and AACODS for gray literature.

Results: Fifty-nine studies met the inclusion criteria, yielding 63 distinct implementation strategies for Open Streets programs. All 63 strategies were classified within the ERIC taxonomy. Frequently aligned ERIC strategies included building coalitions, capturing local knowledge, conducting needs assessments, and fostering stakeholder engagement. Open Streets strategies emphasized multisectoral collaboration, cultural adaptation, equity, and sustainability.

Discussion: Among the 63 identified Open Streets strategies, many aligned with ERIC, providing a foundation in stakeholder engagement, coalition building, and flexible, context-sensitive implementation. However, several ERIC strategies were not relevant to Open Streets, underscoring that while many ERIC strategies were applicable, not all suited this setting. Open Streets programs may require supplemental approaches to address equity, cultural competence, and multisectoral collaboration. Findings present opportunities to tailor, test, and scale strategies that maximize the population health impact of Open Streets and similar community-based programs.

1 Introduction

Chronic diseases are a significant public health concern, responsible for approximately 81% of all deaths in the Americas region, equivalent to 5.8 million deaths annually (1, 2). The age-standardized mortality rate is 411.5 per 100,000 population, with variation between countries, ranging from 301.5 in Canada to 838.7 in Haiti (1, 2). The leading causes of death are cardiovascular disease (34.8%), cancer (23.4%), chronic respiratory diseases (9.2%), and diabetes (4.9%) (1–3). Premature mortality is increasingly concerning, as over one-third of chronic disease deaths occur in individuals under 70 years old, many of which are preventable (1). Modifiable risk factors such as tobacco use, unhealthy diets, obesity, and physical inactivity contribute to the chronic disease burden and are disproportionately distributed across the region (1). While some progress has been made in reducing mortality rates, current efforts remain insufficient to meet global health targets (2). Challenges, such as slow policy implementation, health system disruptions (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic), and inequitable access to diagnosis and treatment, continue to exacerbate the chronic disease crisis in the Americas (1, 3). As inequities persist, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of enhancing both the uptake and effectiveness of evidence-based chronic disease prevention interventions in Latin America, given that many chronic disease deaths are preventable through such programs (4–6).

The current body of literature has demonstrated that engaging in physical activity (PA) is beneficial against numerous chronic diseases, including various cancers and premature mortality (7, 8). The WHO recommends that people aged 19–64 perform 150–300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic PA per week, or at least 75–150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic PA per week. However, the global prevalence of physical inactivity has increased from 26.4% in 2010 to 31.3% in 2022, with Latin America and the Caribbean having the highest prevalence of physical inactivity among adults at 36.6% (9, 10). Various PA interventions have been introduced in Latin American cities to increase PA levels, including community-based initiatives such as Open Streets programs (11, 12).

These programs, known as Ciclovías Recreativas or Ciclopaseos in Spanish, Ruas de Lazer or Ciclofaixas de Lazer in Portuguese, and Open Streets programs in English —the term we will use in this paper— involve temporarily closing at least 1 km of city streets, transforming them into car-free zones for several hours a day (13–15). Such programs create safe and accessible areas for pedestrians, runners, skaters, and cyclists, encouraging leisure activities (15, 16) Additionally, community activities are organized alongside Open Streets to promote PA, foster civic engagement, stimulate local economic growth, support community development, revitalize public spaces, and advocate for walking and cycling as transportation alternatives (17, 18).

Since their inception in the 1960s, Open Streets programs have expanded to 400 locations globally (12), including Latin American cities such as Bogotá—the original site of implementation for the program Ciclovía (18)—as well as Quito, Santiago, São Paulo, and others. These programs have been instrumental in motivating urban residents to utilize public spaces, increase PA, and embrace active transportation (16). Furthermore, in addition to increasing PA among its participants, the programs have demonstrated multiple co-benefits, including increased social cohesion, reduced noise pollution, and improved air quality (15–18).

Open Streets programs offer positive health and economic benefits related to PA due to their low implementation costs and broad reach (15, 17). These programs are positive for health promotion and chronic disease prevention, particularly in areas with high rates of physical inactivity (16). However, increasing the speed and quality of evidence-based chronic disease prevention interventions in the Americas will require identifying effective implementation strategies. Implementation strategies are methods or techniques used to improve the adoption, implementation, sustainment, or scale-up of interventions, constituting the practical “how-to” aspect of transforming healthcare practices (19, 20). To address inconsistent language and insufficient descriptions of implementation strategies in the existing literature, the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy was developed to enhance clarity and consistency in defining these strategies (20, 21).

ERIC provides a comprehensive array of implementation strategies that can be tailored and applied to specific contexts and barriers (20). The effective implementation of evidence-based chronic disease prevention interventions depends partly on selecting and deploying strategies that address key implementation barriers. This matching depends on understanding how and why strategies work or fail, which means identifying the mechanisms through which they operate. A misalignment between strategies and barriers can often result in suboptimal implementation without identifying the mechanisms (20, 22, 23). Proctor et al. (19) proposed recommendations for naming, defining, and operationalizing strategies across seven dimensions: actors, actions, action targets, temporality, dose, outcomes affected, and justification for the strategy’s use (19). These guidelines promote the clear operationalization of these strategies, uncover potential implementation mechanisms through which they work, and may help surface strategies and mechanisms that are particularly relevant to low-resource settings. ERIC strategies are appropriate because they offer adaptable approaches that could help maximize limited resources, engage local stakeholders, and address contextual barriers to the implementation of health promotion interventions (24). For example, the ERIC strategy “build a coalition” could support health promotion in a low-resource setting by bringing together community leaders, local organizations, and public health practitioners to collaboratively plan and implement PA programs using shared resources (24).

Understanding implementation mechanisms, particularly those related to policy-based programs for PA, is crucial for low-resource settings domestically and internationally. This knowledge enables the development of the most efficient and resource-sensitive implementation approaches (25, 26). Foundational work is needed to document commonly used strategies and the putative mechanisms for implementing evidence-based PA programs in the Americas. We conducted a scoping review to better understand the opportunities that exist within widely used implementation science frameworks, such as ERIC and Open Streets programs, across the Americas. Implementation strategies could lead to specific outcomes (e.g., adoption, sustainability) that differ from program outcomes (e.g., PA levels, chronic disease prevalence). This scoping review focuses on the strategies that influence implementation outcomes. The primary aims of this review were to (1) identify implementation strategies across the literature on Open Streets programs and (2) identify opportunities where Open Streets strategies align or misalign with ERIC strategies, to promote chronic disease prevention and PA in the context of the Americas.

2 Methods

We conducted a scoping review on previously published research on Open Streets programs. We followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews and the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting (27, 28).

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Following JBI guidelines (28), we applied the Population, Concept, and Context framework for scoping reviews to define eligibility criteria:

• Population: We included studies with a population of any demographic or clinical background. No specific population characteristics were excluded.

• Concept: Studies focused on Open Streets programs were included. The outcomes measured included physical activity behavior, aerobic capacity, chronic disease outcomes, and the societal, economic, and environmental impacts of Open Streets programs. Exposure variables included health-promoting environmental (often in the built environment) factors, such as green spaces, walkability, access to public transportation, and health facilities.

• Context: We included only studies conducted in the Americas that focused on Open Streets programs.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As seen in Table 1, we included peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2004 and 2024 in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Studies employing a variety of designs were considered, including quantitative empirical studies, qualitative studies, observational research, mixed-methods studies, and reviews (narrative, rapid, umbrella, scoping, systematic, and mixed-methods reviews). There were no restrictions on the population studied, and eligible studies were required to be conducted in community settings (e.g., schools or workplaces) but not in healthcare settings where interventions involved one-on-one advice or counseling. Studies with outcomes evaluating physical activity behavior, aerobic capacity, chronic disease outcomes, or the societal, economic, and environmental impacts of Open Streets or Ciclovia programs were included. Exposures included, but were not limited to, quantitative indicators of health-promoting environmental characteristics, such as green spaces, walkability, access to amenities, public transportation, or health facilities. We only included studies conducted in the Americas, and they had to provide sufficient details about the intervention, particularly concerning Open Streets or Ciclovia programs.

Studies were excluded if they were magazine articles, books, book chapters, book reviews, posters, conference abstracts, study protocols, or dissertations. Studies conducted in exercise laboratories, clinical or hospital settings, or those that used physical activity as a therapeutic intervention or for rehabilitation were also excluded. Additionally, studies that did not specifically mention Ciclovia Recreativa, Open Streets, or similar programs (e.g., Play Streets) or were conducted outside the Americas were excluded.

2.3 Search strategy

The search strategy was conducted in May 2024 with the assistance of a librarian, and it included articles published from January 2004 to May 2024, spanning the last 20 years, to capture recent program developments. Six electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Scielo, Lilacs, and Transportation Information Services (TRIS)) were systematically searched. PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and TRIS were searched in Spanish and Portuguese with translations of the keywords. Scielo and Lilacs were searched using English and Spanish keywords. We selected keywords based on five types of search terms, including “physical activity”, “chronic disease”, “built environment”, “policy” and “Open streets” terms. The search incorporated combinations of these keywords, outlined in Table 2 (for the complete search strategy, see Supplementary Table 1).

We adopted the three-step search strategy proposed by JBI. First, we performed an initial limited search in selected databases and analyzed the titles, abstracts, and index terms of retrieved papers to identify relevant keywords. In the second step, we conducted a comprehensive search across all databases using the identified keywords and index terms. The third and final step focused on references from studies that have been selected for full-text inclusion in the review.

2.4 Study selection

One reviewer conducted systematic database searches (RGR) and imported the results into Rayyan (29), a web-based system for screening blind literature reviews. Two independent reviewers (RGR, FP) removed duplicate entries and screened titles and abstracts against predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine study eligibility. Three independent reviewers (RGR, MFS, FP) screened the full texts of potentially relevant articles and documented reasons for exclusion. To ensure inter-rater reliability, in both the title/abstract and full-text phases of the screening, each article was assessed independently and blinded. The three reviewers resolved disagreements during the screening through consensus meetings.

2.5 Data extraction, data analysis, and synthesis

Data extraction was performed independently by three of the authors (RGR, MFS, FP). Data extraction was completed using a template developed by the authors in Microsoft Excel. The extraction document included multiple fields divided into descriptive and result extraction fields. Descriptive extraction fields included study characteristics, strategies of Open Streets programs, and identified gaps and opportunities in the articles (see data extraction codebook in Supplementary Table 2). During the data extraction phase, we analyzed the settings in which the included articles were conducted, enabling us to assess the frequency of these articles by country within the Americas. To accomplish this, we compiled the frequency of articles by country and city and then developed a map using Microsoft Excel to represent the data visually. This was developed to identify the countries with the highest representation and to discern whether the articles were based in the Global North or the Global South.

Our extraction approach comprised five key steps. For step 1, three independent reviewers (RGR, MFS, FP) extracted potential implementation strategies from the studies included in the review. In step 2, each extracted Open Streets strategy was matched to the list of 73 ERIC strategies (19). Strategies were coded as “1” if they matched an ERIC strategy and “0” if they did not. This process was divided equally for two reviewers (RGR, MFS) and was reviewed by two additional reviewers (DP, FP) to ensure inter-rater reliability. This process enabled us to systematically assess which Open Streets strategies aligned with ERIC strategies.

In step 3, a deductive thematic analysis approach (30) was employed to identify themes, informed by the feasibility and importance of ERIC strategies in grouping the strategies (31). Color coding was used to organize the Open Streets strategies under each theme and subtheme (see Supplementary Table 3). This strategy enabled the data to be connected to nine themes and 52 sub-themes, allowing flexibility to facilitate the categorization process of the Open Streets strategies (see Supplementary Table 4). For step 4, we calculated the frequencies and percentages for the number of times Open Streets strategies matched the ERIC strategies. Using the frequencies and percentages, strategies were grouped under relevant themes and sub-themes. One reviewer (RGR) initially performed this categorization, and then it was reviewed by three additional team members (DP, MFS, FP) to ensure accuracy and consistency. The final step involved refining the list of Open Streets strategies. Team members independently reviewed each identified strategy to determine whether to include or exclude it, and a consensus meeting was conducted to finalize the list. At the end of the data extraction process, a narrative synthesis was prepared by three members (RGR, MFS, FP) of the research team, which included the frequencies of locations (countries and cities of study) and a narrative synthesis of the study characteristics.

2.6 Assessment of methodological quality

We appraised each study with a tool that matched its design: the MMAT (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) 2018 for empirical studies (ranging from qualitative, quantitative randomized controlled trials, quantitative non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed method studies), recording item-by-item judgments (“Yes/No/Cannot tell”) with brief evidence notes (32). For reviews/evidence syntheses, we applied the AMSTAR-2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews, version 2) tool to evaluate the methodological rigor recording, and item-by-item judgments were recorded (“Yes/No/Partial”) (33). For gray literature, technical manuals, and commentaries/conceptual papers, we used the AACODS checklist (Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance), and item-by-item judgments were recorded (“Yes/No/Partial”) (34). All appraisals were logged in an Excel template for MMAT, AMSTAR-2, and AACODS to ensure consistency and to contextualize findings in the synthesis. One member of the team (RGR) appraised all the articles, and two other members (DP and MFS) verified the appraisal for accuracy.

3 Results

Overall, we identified 201 articles, and after excluding 74 duplicates, 127 were screened for titles and abstracts. Full-text assessment was performed on a total of 87 studies, and after eligibility assessment, 59 studies were included in this review (see Figure 1). The main reasons for exclusion were incorrect outcome (n = 22) or background article (n = 6).

3.1 Narrative synthesis of study designs, settings, similarities, and differences of key findings

The 59 studies included in this review (see Table 3) were published between 2005 and 2024, spanning nearly two decades on Open Streets programs. Cross-sectional designs and observational methods were the most common, such as intercept surveys of participants (35) and systematic observation counts using SOPARC protocols (36, 37). Several studies incorporated accelerometry (38), GIS (39), or spatial analyses to assess equity in access to Ciclovia (40). Mixed-methods (18, 41) and qualitative (42–44) approaches highlighted program sustainability, community engagement, and policy processes, while participatory and CBPR (Community-Based Participatory Research) designs emphasized advocacy and local ownership as essential factors of Open Streets events (38, 45–47). Economic analysis and natural experiments quantified causal effects and cost-effectiveness, with cost–benefit ratios ranging from 1.02 to 4.26 across different cities (48), and substantial improvements in air quality during Open Streets events (49).

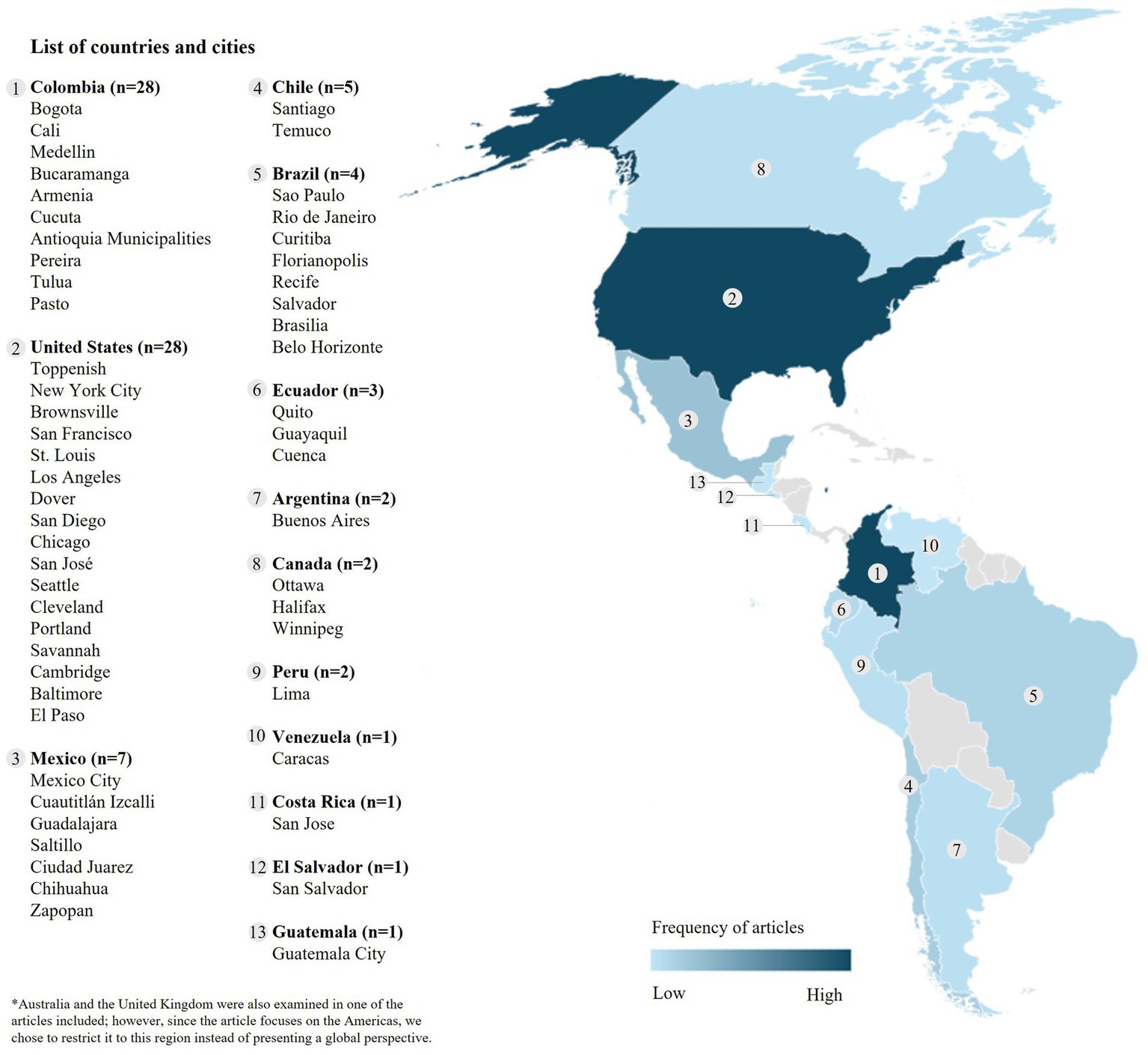

The distribution of articles in this review demonstrates that Colombia and the US dominate the evidence base (see Figure 2), each contributing 28 studies, reflecting the long-standing Ciclovia in Bogota and the rapid expansion of Open Streets in US cities. Mexico (n = 7), Chile (n = 5), and Brazil (n = 4) also had notable representation, while several other Latin American countries and Canada contributed fewer studies (1–3 each). It is essential to note that the total number of articles exceeds 59 in the map, as many articles encompass multiple countries in their studies. Most of the studies were set in urban Latin America, particularly Bogotá, Colombia. Bogota’s programs alone attract approximately 400,000 weekly participants, with route lengths exceeding 117 km (50). Other Latin American sites included Mexico City, where Muévete en Bici averages approximately 21,800 participants weekly across a 55-km route (51), as well as Santiago de Chile (17), Cali (52), Quito (18), Saõ Paulo (53), Saltillo (54), and multiple other Latin American cities. In the US, evaluations focused on single events or city initiatives, such as CicLAvia in Los Angeles, which engages approximately 36,800 to 54,700 participants in one event and generates176,000–263,000 MET-hours of PA (55), Summer Streets in New York City, with approximately 50,000 participants in a single day (56), and Viva CalleSJ in San José, with attendance estimates up to 125,000 (57). Rural settings were less common, with only one rural town in this review, Toppenish, Washington, reaching approximately 200–394 participants per hour, which presented 2–4% of the town’s population (45, 46).

Figure 2. Map of the Distribution of Countries and Cities Represented in the Studies included in this Scoping Review.

Across contexts, Open Streets consistently promoted PA and social connectedness. Participants frequently met or exceeded daily or weekly PA guidelines during events. In Mexico City, 88.4% of users met the 150 min/week recommendation during the Muévete en Bici event, adding approximately 71 min of MVPA weekly (51). In Los Angeles, 45% of CicLAvia attendees reported they would have otherwise been sedentary (55), while in San Diego, 97% met the 30-min/day threshold and 39% met the 150-min/week guideline during CicloSDias (22). Open streets fostered equity and inclusion, with essential differences in context. In Bogotá and Santiago de Cali, Ciclovía participants crossed neighborhoods of varying socioeconomic status, supporting social inclusion (17). Yet inequities in geographic access are even more evident: in Bogotá, the median distance to Ciclovía was 2,938 meters for the lowest socioeconomic status, compared to 482 meters for the highest socioeconomic status, a six-fold disparity (58). In contrast, US programs were smaller and often attracted disproportionately white, higher-income participants, as seen in St. Louis, where attendees were primarily white and college-educated despite the city’s demographics (35). However, targeted outreach and community-led adoption were successful in a rural Open Streets event in Toppenish, Washington, where attendance at the event grew and participants from Hispanic/Latino and American Indian backgrounds were engaged (45, 46).

Findings varied by subpopulations, among children in Bogotá, frequent Ciclovia users engaged in more MVPA on Sundays; however, they had higher BMI z-scores compared with non-users (59). Recreovía increased PA among women in Bogotá, with 75% meeting MVPA guidelines compared with 61% in non-program parks (60). During the COVID-19 pandemic, adaptations such as virtual and balcony-based sessions enabled 72–79% of older adults to meet WHO PA guidelines (61). Environmental factors, such as infrastructure quality, safety, and political support, are consistently linked to sustainability and scalability (12, 40, 42, 62). For example, Diaz del Castillo et al. identified flexibility, instructor training, public funding, and community champions as key to maintaining programs that reached more than 1,455 communities in Colombia (41). Similarly, economic evaluations demonstrated that Ciclovia’s were highly cost-effective in Latin America, with cost–benefit ratios exceeding 3.0 in Bogotá, while US programs had higher per-capita costs (48).

3.2 Qualitative results

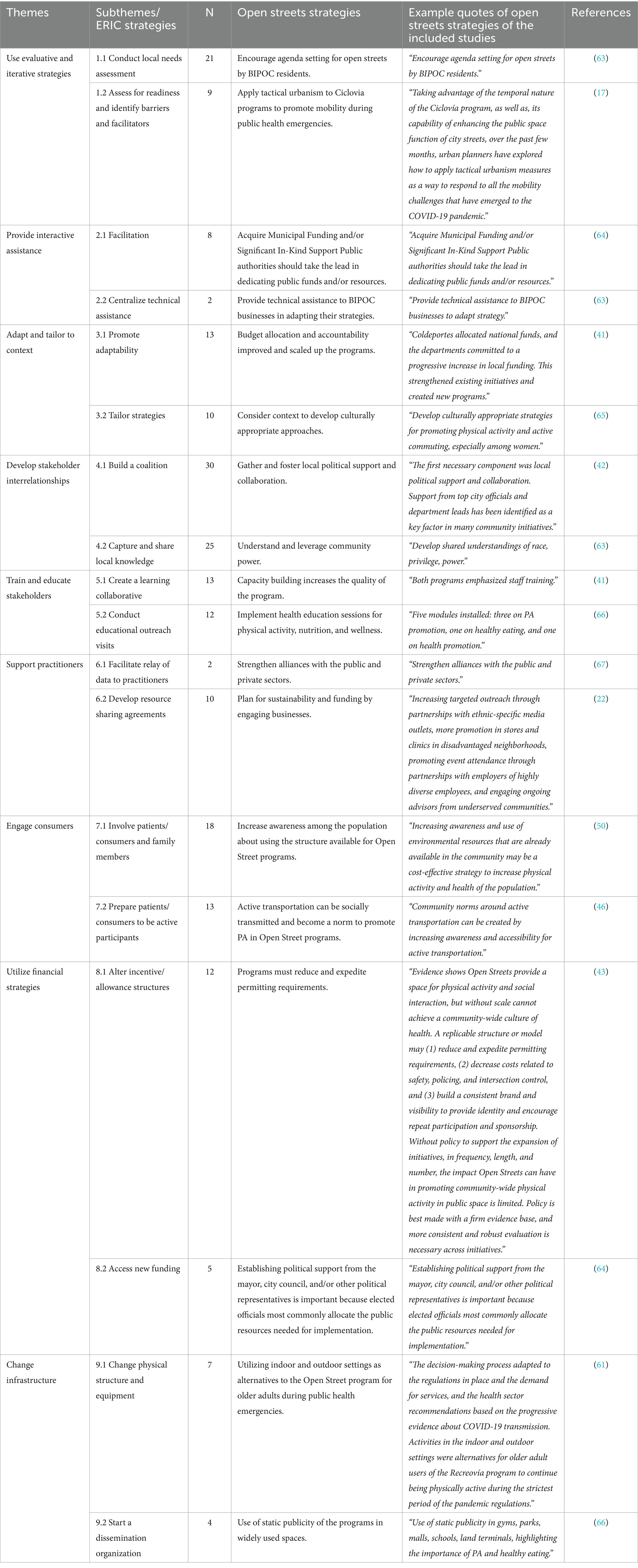

We identified 63 strategies for Open Streets programs from the 59 studies reviewed in this analysis (see Supplementary Table 8). The identified Open Street strategies were matched with 52 ERIC strategies.

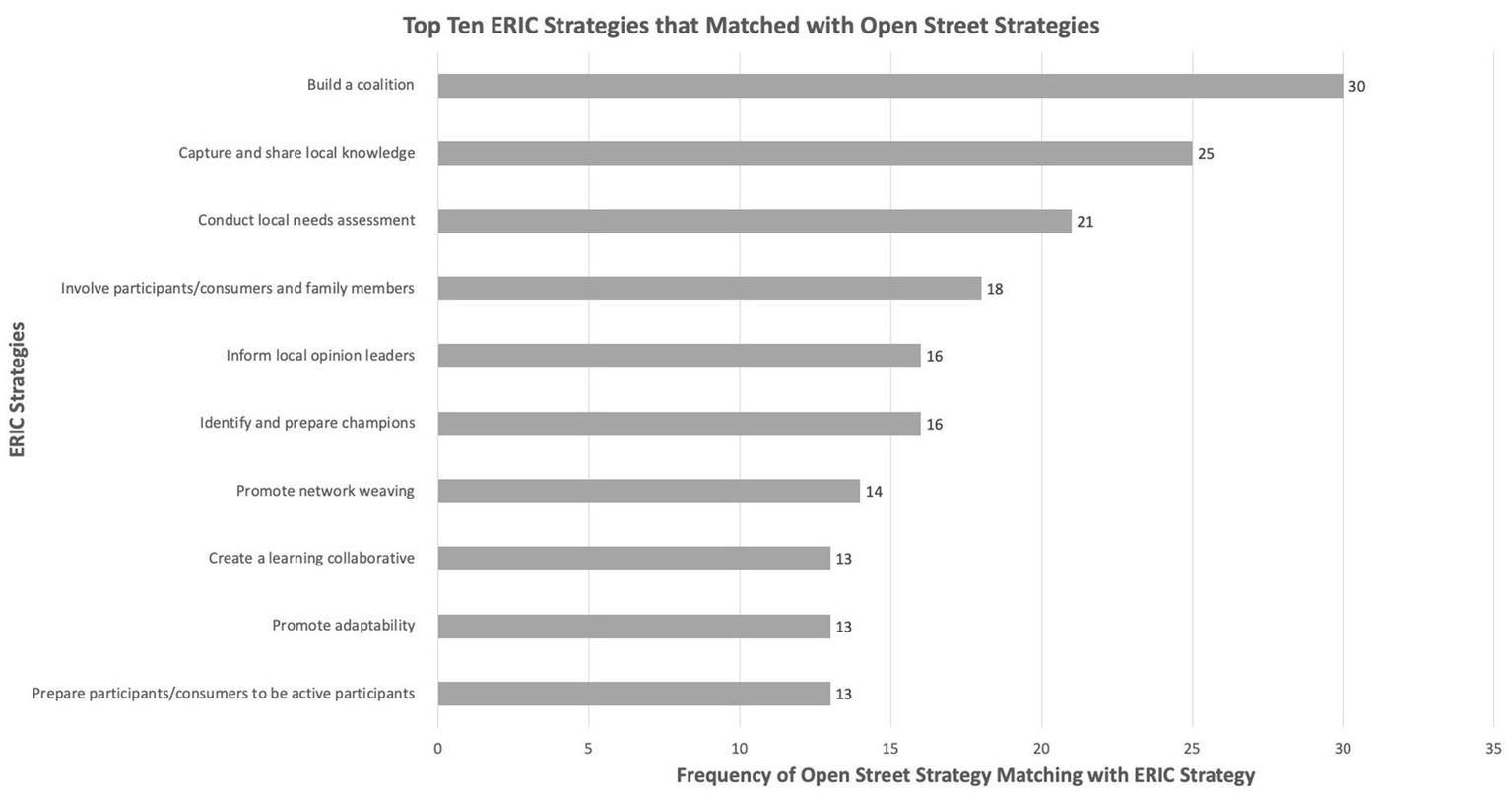

Figure 3 presents the top ten ERIC strategies matched with the Open Streets strategies identified in this review. The most aligned ERIC strategy identified was “Build a coalition” (n = 30), followed by “Capture and share local knowledge” (n = 25), and “Conduct a local needs assessment” (n = 21). Other frequently matched strategies included “Involve participants/consumers and family members’ (n = 18), followed by “Identify and prepare champions” and “Inform opinion leaders’ (n = 16 each). Additionally, the strategies “Promote network weaving” (n = 14), “Prepare participants/consumers to be active participants,” “Promote adaptability,” and “Create a learning collaborative” were each matched with 13 Open Streets strategies. Using the thematic analysis approach, we categorized the identified Open Streets strategies into nine themes and 52 sub-themes (see Supplementary Table 5). Table 4 presents example quotes from Open Streets strategies in studies included in the review, organized by theme and the two most prevalent sub-themes.

3.2.1 Theme 1: use evaluative and iterative strategies

This theme emphasizes the development of evaluative and iterative strategies for the Open Streets program, including planning and responding to public health emergencies. The Open Street strategy, “Encourage agenda setting for open streets by BIPOC residents,” is presented in a conceptual paper by Slabaugh et al. as a part of the “partnerships” category. The authors stress the following: “planners build reciprocal partnerships with racial and environmental justice organizations” and conduct engagement with BIPOC residents, particularly “at the agenda-setting stage for open streets” (63). This shift in decision-making power for BIPOC communities, not just city officials, to define the priorities and purposes of open streets, could ensure interventions reflect the lived experiences and local needs (63). This relates directly to the ERIC strategy of “Conducting local needs assessments” (sub-theme 1.1); both strategies center BIPOC expertise and context-specific knowledge: agenda setting empowers residents to shape the vision of Open Street events, while needs assessments could provide the evidence base for what priorities should be, thereby aligning planning and community-defined needs rather than imposing external agendas.

The next Open Street strategy, “Apply tactical urbanism to Open Street programs to promote mobility in time of health emergencies,” is presented in a study by Mejia-Arbelaez et al., in the context of how Ciclovia programs can temporarily transform streets into democratic, flexible spaces that respond to crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic by allowing safe mobility and recreation. This translates to using low-cost, rapid, and adaptable interventions (e.g., pop-up bike lanes, temporary road closures) to sustain access to physical activity and social inclusion during emergencies (17). This relates to the ERIC strategy, “Assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators” (sub-theme 1.2), because before deploying tactical urbanism, cities must evaluate community capacity, political will, and logistical obstacles to ensure that emergency responses are both feasible and effective.

3.2.2 Theme 2: provide interactive assistance

Interactive assistance between public authorities, the community, event organizers, and participants is essential for implementing and sustaining Open Streets programs. The Open Street strategy, “Acquire Municipal Funding and/or Significant In-Kind Support from Public authorities should lead in dedicating public funds and/or resources,” is in the Open Streets Guide developed by the Alliance for Biking and Walking. It is presented in the guide as a “best practice” to help ensure program sustainability, highlighting that when cities commit budgetary resources or staff time, it signals institutional support and could allow initiatives to grow beyond pilot phases (64). Municipalities should not only permit Open Street events but also actively invest in them, for example, through direct funding, police and staff time, or logistical support (64). This aligns with the ERIC strategy of “Facilitation” (sub-theme 2.1) because public agencies’ in-kind resources (e.g., traffic control, permits, staffing) directly facilitate the safe and consistent operation of open streets, which can lower barriers for community partners and aid in implementation (64). The next Open Street strategy, “Provide technical assistance to BIPOC businesses in adapting their strategies,” is presented in a conceptual paper by Slabaugh et al., in the context of programmatic responses that help navigate paradoxes such as displacement and safety by supporting BIPOC-owned businesses to participate in and benefit from Open Streets (e.g., permitting for outdoor dining, materials support) (63). Offering resources and guidance to BIPOC businesses could help in adjusting to new street uses rather than being excluded or displaced (63). This relates to the ERIC strategy “Centralized Technical Assistance” (sub-theme 2.2) because while centralized creates a broader support system, targeted assistance to BIPOC businesses ensures equity by addressing specific inequities and barriers they face within that system.

3.2.3 Theme 3: adapt and tailor to context

Adapting Open Streets programs to local contexts could help increase their relevance, accessibility, and sustainability across different localities. The Open Street strategy, “Budget allocation and accountability to improve and scale up program,” is presented in the results of a study by Díaz Del Castillo et al., as a part of the continuation and growth of Colombia’s HEVS (Healthy Habits and Lifestyles) program, where a co-funding scheme launched in 2008 allowed national and local governments to dedicate resources, hire trained personnel, and require accountability of program guidelines and goals (41). Providing financial resources and connecting them with clear responsibilities transformed policies from paper commitments into sustained, concrete actions (41). This relates to the ERIC strategy of “Promoting Adaptability” (sub-theme 3.1) because stable funding and accountability mechanisms give the programs the flexibility to adjust to changing conditions while ensuring they continue scaling up effectively.

The next Open Street strategy, “Consider context to develop culturally appropriate approaches,” is presented in a study by Gómez et al., where the authors emphasize that differences in gender, socioeconomic status, and neighborhood terrain (flat vs. hilly) affect walking and bicycling behaviors in Bogotá (65). Interventions should be designed with sensitivity to local cultural, social, and environmental conditions rather than relying on models from high-income countries (65). This relates directly to “Tailor Strategies” (sub-theme 3.2), because tailoring requires adapting interventions to these contextual differences to ensure effectiveness and equity in promoting active transport in Open Street events.

3.2.4 Theme 4: develop stakeholder interrelationships

Theme four emphasizes building strong networks and stakeholder collaborations to support physical activity promotion programs. The Open Street strategy, “Gather and foster local political support and collaboration,” is presented in a study by Eyler et al. as a necessary foundation for Open Streets success, since strong backing from city officials and interdepartmental collaboration reduced costs and helped embed initiatives into broader agendas such as transportation and sustainability (42). Engaging elected leaders and agencies to champion and sustain Open Streets through advocacy, visibility, and shared resources (42). This is related to the ERIC strategy “Build a Coalition” (sub-theme 4.1), because political support becomes more effective when connected to coalitions of community groups, businesses, and health advocates working together toward long-term sustainability. The next Open Street strategy, “Understand and leverage community power,” is presented in a conceptual paper by Slabaugh et al., in the section on partnerships and institutional culture, using tools such as the City of Austin’s (Texas) equity assessment that grew out of grassroots organizing (63). Recognizing the influence and expertise that communities, particularly BIPOC residents, bring, and using that power to reshape policies and planning processes toward justice (63). This is related to the ERIC strategy “Capture and share local knowledge” (sub-theme 4.2), as both strategies center on community expertise, with one emphasizing power as a lever in decision-making and the other emphasizing knowledge as a resource to inform and transform planning of programs such as Open Streets.

3.2.5 Theme 5: train and educate stakeholders

This theme focuses on training and educating stakeholders to promote Open Streets programs, supporting collaboration and capacity building. The Open Street strategy, “Encouraging capacity building increases the quality of the program,” is presented in the results of a study by Díaz Del Castillo et al., as part of the continuation and growth strategies for Recreovía and HEVS, where investment in staff training and better working conditions was essential to ensure skilled instructors who could attract and retain participants (41). Prioritizing human resources and professional development could strengthen program delivery and sustainability (41). This connects to the ERIC strategy “Create a learning collaborative” (sub-theme 5.1), because both emphasize continuous learning; capacity building improves individual and organizational quality, while a learning collaborative fosters a shared knowledge and collective improvement across Open Street programs. The next Open Street strategy, “Implement health education sessions for physical activity, nutrition, and wellness,” is presented in a technical report by the Ministry of Health of Peru in 2015, as a part of the required modules of Ciclovia Recreativa, which include three physical activity modules, one on healthy eating, and one on general health promotion (66). This integration of structured educational content into the program enables participants to engage not only in physical activity but also to learn about healthy lifestyles (66). This relates to the ERIC strategy “Conduct educational outreach visits” (sub-theme 5.2), since both focus on extending health knowledge, and sessions provide on-site learning during the Ciclovia, while outreach visits expand this education into neighborhoods, schools, or workplaces to reinforce the program’s impact.

3.2.6 Theme 6: support clinicians/stakeholders

This theme focuses on supporting stakeholders/practitioners and facilitating collaboration across sectors to promote physical activity. The Open Street strategy, “Strengthen alliances with the public and private sectors,” is presented in the term results of the Recreovía logic model by Ríos et al. emphasizing the role of multi-sector partnerships in sustaining program delivery, expanding resources, and increasing visibility (67). Building collaborative networks with government agencies, companies, and civil society could reinforce program impact and reach (67). This relates to the ERIC strategy “Facilitate relay of data to stakeholders” (sub-theme 6.1), because effective alliances depend on transparent communication, sharing program results and data ensures accountability, maintains trust, and could help partners see the value of continued investment. The next Open Street strategy, “Plan for sustainability and funding by engaging businesses,” is presented as a recommendation for improving Open Street events in an evaluation study by Engelberg et al. of San Diego’s first Open Street initiative (CicloSDias) (22). Actively cultivating business engagement to secure ongoing resources could help sustain the program beyond one-time events (22). This aligns with the ERIC strategy “Develop resource-sharing agreements” (sub-theme 6.2), because both focus on creating structured partnerships, business engagement brings in funding or sponsorship, while resource-sharing agreements formalize contributions (e.g., staff, equipment, services) to ensure sustainability and reduce reliance on a single funding stream (22).

3.2.7 Theme 7: engage consumers

Theme seven focuses on actively involving participants, community members, and diverse groups in Open Streets programs to maximize the co-benefits of the program. The Open Street strategy, “increased awareness among the population about using the structure available for Open Street programs,” is presented in a paper by Parra et al., where the authors emphasize that despite significant investments in Ciclovía, Ciclorutas, and parks, their health impact depends on people knowing about and using them (50). This means that communication, education, and engagement efforts are needed so residents take advantage of these infrastructures for physical activity (50). This relates to the ERIC strategy “Involving participants/family members” (sub-theme 7.1), because raising awareness is more cost-effective when families and communities are directly engaged, creating social support networks that reinforce participation and regular use of the available structures.

The next Open Street strategy, “Active transportation can be socially transmitted and become a norm to promote PA in Open Street programs,” is presented in a study by Ko et al., where the authors note that children and adults in rural ciclovias began adopting bicycling and walking when opportunities and visibility increased, demonstrating how behaviors can be spread through social learning and community modeling (46). When people see others regularly engaging in active transportation, it normalizes the behavior and could encourage broader participation (46). This aligns with the ERIC strategy “Prepare participants/consumers to be active participants” (sub-theme 7.2), as equipping community members with the skills, resources, and confidence can enhance their ability to join in and reinforce these emerging social norms.

3.2.8 Theme 8: utilize financial strategies

This theme emphasizes the use of financial approaches to sustain and scale up Open Streets programs. The Open Street strategy, which states that “programs must reduce and expedite permitting requirements,” is presented in a study by Hipp et al. The authors argue that burdensome and inconsistent permitting processes remain a key barrier to scaling Open Streets in the US. Streamlining or creating dedicated permitting pathways can make it easier, cheaper, and faster for organizers to host events (43). This aligns with the ERIC strategy “Alter incentive/allowance structures” (sub-theme 8.1), because both strategies address systemic barriers, such as reducing permitting obstacles and adjusting incentives to create an enabling environment that encourages municipalities and communities to hold more frequent and sustainable Open Street programs (43). The next Open Street strategy: “Establishing political support from the mayor, city council, and/or other political representatives is important because elected officials most commonly allocate the public resources needed for implementation.” It is presented in the Open Streets Guide developed by the Alliance for Biking and Walking, as a part of the lessons on securing sustainability and legitimacy, emphasizing that high-level political champions are often decisive in dedicating funds, staff, and institutional backing (64). Cultivating visible support from elected officials could improve access to the municipal budgets and resources required to run and expand programs (64). This aligns with the ERIC strategy, “Accessing New Funding” (sub-theme 8.2), as political support can provide access to public resources and position programs to pursue new and diversified funding streams with stronger credibility and institutional endorsement.

3.2.9 Theme 9: change infrastructure

Theme nine focuses on changing infrastructure to promote physical activity through various strategies. The Open Street strategy: “Utilizing indoor and outdoor settings as alternatives to the Open Street program for older adults during public health emergencies.” It is presented in a study by Gónzalez et al., where the authors describe how the Recreovía adapted during the COVID-19 pandemic with virtual sessions, window-based classes, and socially distanced park activities to maintain physical activity opportunities (61). Creating flexible delivery models, particularly for older adults, to enable them to remain active despite lockdowns or social distancing conditions (61). This relates to the ERIC strategy “Changing physical structures and equipment” (sub-theme 9.1), since both focus on adaptation. Providing safe alternative venues complements the modification of physical spaces and tools to ensure continuity of physical activity during public health emergencies (61).

The next Open Street strategy, “Use of static publicity of the programs in widely used spaces” is presented in a technical report by the Ministry of Health of Peru in 2015, as a part of the promotion and communication activities for Ciclovia Recreativa, where municipalities are instructed to place posters and signage in gyms, parks, schools, and transportation terminants to raise awareness and participation (66). This means leveraging visible, everyday community spaces to keep the program in the public eye and encourage consistent engagement (66). This relates to the ERIC strategy, “Start a Dissemination Organization” (sub-theme 9.2), because a dedicated dissemination organization would formalize and expand these efforts, coordinating broader communication campaigns and sustaining outreach across regions.

3.3 Assessment of methodological quality of studies

In the studies appraised with the MMAT-Qualitative (section 1) studies (n = 11), most demonstrated clear questions, appropriate case-study or interview designs, and clear linkages between data and interpretations. Limitations commonly included small purposive samples, limited reflexivity/positionality reporting, and sparse detail coding inter-reliability, which could constrain transferability. For the MMAT-Quantitative non-randomized (section 3) studies (n = 13), validated measures and multivariable analyses were common strengths, while cross-sectional designs, residual confounding, and self-report biases constrained causal inference and external validity. In the MMAT-Quantitative descriptive (section 4) studies (n = 20) were the most common, methods fit the event-day description (counts, intercept surveys, SOPARC protocol). However, representativeness was often uncertain due to convenience sampling, single-day data collection, and unreported nonresponse. For MMAT-Mixed methods (section 5) studies (n = 8), most provided a clear rationale and triangulated surveys, interviews, and administrative data to yield actionable insights, and treatment of quantitative-qualitative divergences was limited.

Across reviews (n = 3) appraised with the AMSTAR-2 tool, multiple critical domains (a priori protocol, comprehensive search, duplicate selection/extraction, and risk-of-bias assessment) were frequently unmet, yielding critically low confidence ratings. Even where eligibility criteria and search procedures were described, syntheses were primarily narrative with limited incorporation of study quality into conclusions; findings are best interpreted as contextual rather than effects. For gray-literature items assessed with the AACODS checklist (n = 4), Authority and Significance were high (governmental/sector sources with strong implementation detail), and procedures were clearly specified. Objectivity was often partial and coverage context-bounded; accordingly, these sources are used to describe standards, processes, and implementation context, not to infer intervention effectiveness. See Supplementary Table 6 for the methodological appraisal of the studies.

4 Discussion

This scoping review identified Open Street strategies in the literature across the Americas and examined their alignment with the ERIC taxonomy. We identified 63 strategies (see Supplementary Table 8) from 59 studies, all of which aligned within the ERIC taxonomy, however, there were approximately 21 ERIC strategies (see Supplementary Table 7) that were not relevant to Open Streets, underscoring that while many ERIC strategies were applicable, not all suited this setting. These findings illustrate that while ERIC provides a strong foundation, adaptations are needed to capture strategies specific to community-based, non-clinical interventions.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that incorporating physical activity is crucial for preventing chronic diseases (7, 8, 21, 26–34, 38, 45, 59). A robust literature exists describing how Open Streets programs promote physical activity, many of which are included in this review. To date, there has been sparse information on Open Streets implementation strategies. The implementation of this program can improve the health of populations, particularly those with the lowest prevalence of physical activity in the Americas (9, 10). We found that Open Street programs consistently foster physical activity and social connectedness across diverse settings, with participants frequently meeting or exceeding PA guidelines during events (17). However, the reach and equity of these programs vary by context. For example, in Bogotá and Santiago de Cali, Ciclovia facilitated cross-neighborhood mobility across socioeconomic divides (17, 18). However, geographic access remained highly unequal, with low-SES residents facing significantly longer distances to travel on these routes (58). In contrast, US programs were smaller in scale and often attracted disproportionately white, higher-income participants in urban areas (35). Conversely, targeted outreach in rural towns was successful in engaging with Hispanic/Latino and American Indian communities (45, 46). These contextual disparities underscore the importance of tailoring strategies to local demographics and built environment conditions.

The strategies we identified clustered around planning promotion, evaluation, and sustainability, with coalition-building emerging as the most common ERIC-aligned strategy. This is consistent with prior literature, fostering multisectoral partnerships (68), political support (48), and community engagement (66) were essential for program adoption and long-term sustainability (18, 41, 46). Strategies unique to Open Streets included applying tactical urbanism to reimagine street use during emergencies (17), leveraging family cohesion to motivate child/adolescent participation (59), and rapidly adapting programs to virtual or balcony formats during the COVID-19 pandemic (61). These innovations illustrate the adaptability of Open Streets to evolving public health challenges (e.g., infectious diseases, climate change, physical inactivity) (15, 69–71).

Despite promising evidence, several gaps remain. First, while strategies were well-documented, few studies have evaluated their effectiveness across contexts or over time. For example, we cannot yet determine which strategies are most effective for reaching underserved groups, sustaining funding, or scaling programs. Second, most studies came from Colombia and the US, limiting generalizability to other parts of the Americas or globally. Additionally, rural contexts remained remarkably underexplored. Third, social inclusion and equity were evident in multiple studies reviewed (17, 62); however, the systematic assessment of implementation mechanisms, such as how strategies reduce inequities in access or outcomes, was not explored. Offering equitable access and inviting the community as a whole to participate in the program is especially important for promoting physical activity and improving public health (48). Participation in the Open Streets should be voluntary and welcoming to all socioeconomic levels, races, ethnicities, abilities, ages, and genders to reduce inequities (41, 58, 72). For example, Open Street strategies such as targeted outreach, partnerships with local organizations (e.g., non-profits, businesses, and local government), and transportation support could help engage low-socioeconomic-status, rural, and indigenous communities (45, 46, 57). Additionally, adapting program activities to cultural preferences and ensuring representation in the planning processes could foster inclusivity and more participation in Open Streets (64, 65). Examples of operationalizing Open Street Strategies with local governments and non-profits include integrating these programs into existing health promotion plans, allocating dedicated funding for equity-focused outreach, and forming cross-sector coalitions to coordinate resources and community engagement (44, 73).

A strength of this review is that it is the first study to identify strategies from Open Streets programs in diverse countries and compare them to the ERIC strategies, exposing several unique comparisons that are useful for the program’s implementation. Some of the Open Street’s strategies obtained from this review carry specific steps for upscaling the program and can provide useful techniques for implementers (see Supplementary Table 7). This is not surprising, given that ERIC was initially developed for healthcare interventions. However, our review indicates that most Open Streets strategies align well with ERIC strategies, particularly those emphasizing coalition-building, context adaptation, stakeholder engagement, and interactive evaluation. These findings highlight that while specific ERIC strategies are not directly transferable to non-clinical, community-based interventions, the taxonomy’s core principles are highly relevant and serve as a valuable foundation for adapting existing taxonomies or frameworks to new settings. Additionally, our use of ERIC highlights the similarities between established implementation strategies in healthcare and those effective in public health initiatives, such as Open Streets. While our review identifies strategies being used, we cannot mention which strategies are most effective in various contexts. This reveals more areas of overlap than differences, suggesting that adapting existing taxonomies, rather than introducing new ones, could be feasible and advantageous.

Future opportunities include testing strategies in controlled or quasi-experimental designs, assessing their transferability across diverse socio-political contexts, and adapting the ERIC strategies to be more explicit for community and public-space interventions. Particular attention should be given to implementation mechanisms in low-resource and culturally diverse settings, ensuring that Open Streets expand access equitably. Programs could also benefit from embedding evaluation processes that track sustainability, costs, and co-benefits such as environmental quality, social cohesion, and local economic activity. There is an excellent opportunity for future studies to continue bridging the gap between the disciplines of physical activity and implementation science, testing, adapting, and scaling up implementation strategies to strengthen the population health impact of Open Streets and similar programs (74–76). While this review concentrated on classifying the identified Open Street strategies to ERIC to highlight areas of alignment and misalignment, this is only the first paper in a planned series of studies. In our follow-up work, we aim to specify and refine the strategies identified in this review, guided by the recommendations of Proctor et al. (19).

There are several limitations of this review; first, not all countries in the Americas were included in the studies or documented these initiatives, which decreases its generalizability to the rest of the world. Second, due to our focus on the Americas only and considering the cultural differences with other parts of the world, modifications may be necessary for implementation. Third, we only included a limited number of gray literature; future studies should systematically examine the gray literature to get a broader context on Open Street programs. Fourth, we decided to focus our search on English, Spanish, and Portuguese; however, future studies should examine if there is gray literature in the indigenous languages of the Americas, particularly in Latin America, which are spoken by millions of individuals (77).

5 Conclusion

This scoping review presents the first systematic classification of Open Streets implementation strategies in relation to the ERIC taxonomy of strategies. While substantial alignment exists, Open Streets also introduces unique approaches that highlight the value of adapting healthcare-driven frameworks for community-based health promotion programs. The dissemination and replication of Open Streets programs into other cities and rural areas are essential for public health, both locally and globally, in low and middle-income countries. They are crucial to reducing chronic disease disparities and increasing access to and equity in physical activity. Future research should focus on implementation mechanisms for low-resourced domestic and international settings to inform the most parsimonious and resource-sensitive approaches to Open Streets programs.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

RG-R: Visualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Project administration, Validation, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MF: Software, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology. FP: Resources, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation, Visualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. BW: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. BP: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Validation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. RB: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Validation. DP: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Writing – original draft, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Diana C. Parra was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA262325. Raul D. Gierbolini-Rivera was supported by Grant No. T32 HL130357 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health. The content was solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1667559/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Luciani, S, Nederveen, L, Martinez, R, Caixeta, R, Chavez, C, Sandoval, RC, et al. Noncommunicable diseases in the Americas: a review of the Pan American health organization's 25-year program of work. Rev Panam Salud Publica. (2023) 47:e13. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2023.13

2. Luciani, S, Agurto, I, Caixeta, R, and Hennis, A. Prioritizing noncommunicable diseases in the Americas region in the era of COVID-19. Rev Panam Salud Publica. (2022) 46:e83. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2022.83

3. Curado, MP, and de Souza, DL. Cancer burden in Latin America and the Caribbean. Ann Glob Health. (2014) 80:370–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.09.009

4. Colditz, GA, and Wei, EK. Preventability of Cancer: the relative contributions of biologic and social and physical environmental determinants of Cancer mortality. Annu Rev Public Health. (2012) 33:137–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124627

5. Colditz, GA, Wolin, KY, and Gehlert, S. Applying what we know to accelerate cancer prevention. Sci Transl Med. (2012) 4:127rv4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003218

6. American Cancer Society, Institute of Medicine. Fulfilling the potential of cancer prevention and early detection: an American Cancer Society and Institute of Medicine Symposium. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2004). Available online at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10941

7. Warburton, DER, and Bredin, SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: a systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr Opin Cardiol. (2017) 32:541–56. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000437

8. McTiernan, A, Friedenreich, CM, Katzmarzyk, PT, Powell, KE, Macko, R, Buchner, D, et al. Physical activity in Cancer prevention and survival: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2019) 51:1252–61. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001937

9. Guthold, R, Stevens, GA, Riley, LM, and Bull, FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet glob. Health. (2018) 6:e1077–86. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7

10. Strain, T, Flaxman, S, Guthold, R, Semenova, E, Cowan, M, Riley, LM, et al. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. (2024) 12:e1232–43. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(24)00150-5

11. Galaviz, KI, Harden, SM, Smith, E, Blackman, KC, Berrey, LM, Mama, SK, et al. Physical activity promotion in Latin American populations: a systematic review on issues of internal and external validity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2014) 11:77. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-77

12. Zieff, SG, Musselman, EA, Sarmiento, OL, Gonzalez, SA, Aguilar-Farias, N, Winter, SJ, et al. Talking the walk: perceptions of neighborhood characteristics from users of open streets programs in Latin America and the USA. J Urban Health. (2018) 95:899–912. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0262-6

13. Ciclovías Recreativas de las Américas. Ciclovías Recreativas de las Américas. (2019). Available online at: https://cicloviasrecreativas.org/

14. Sá, T, Garcia, L, and Andrade, D. Reflexões sobre os benefícios da integração dos programas Ruas de Lazer e Ciclofaixas de Lazer em São Paulo. Rev Bras Ativ Fis Saude. (2017) 22:5–12. doi: 10.12820/rbafs.v.22n1p5-12

15. Velázquez-Cortés, D, Nieuwenhuijsen, MJ, Jerrett, M, and Rojas-Rueda, D. Health benefits of open streets programmes in Latin America: a quantitative health impact assessment. Lancet Planet Health. (2023) 7:e590–9. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00109-2

16. Bird, A, Díaz del Castillo, A, Hipp, A, et al. Open streets: trends and opportunities. (2017). Available online at: https://www.880cities.org/images/880tools/openstreets-policy-brief-english.pdf

17. Mejia-Arbelaez, C, Sarmiento, OL, Mora Vega, R, Flores Castillo, M, Truffello, R, Martínez, L, et al. Social inclusion and physical activity in Ciclovía Recreativa programs in Latin America. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:655. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020655

18. Sarmiento, OL, Díaz Del Castillo, A, Triana, CA, Acevedo, MJ, Gonzalez, SA, and Pratt, M. Reclaiming the streets for people: insights from Ciclovías Recreativas in Latin America. Prev Med. (2017) 103:S34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.028

19. Proctor, EK, Powell, BJ, and McMillen, JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

20. Powell, BJ, Waltz, TJ, Chinman, MJ, Damschroder, LJ, Smith, JL, Matthieu, MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

21. Castro Torres, AF, and Alburez-Gutierrez, D. North and south: naming practices and the hidden dimension of global disparities in knowledge production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2022) 119:e2119373119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2119373119

22. Engelberg, JK, Carlson, JA, Black, ML, Ryan, S, and Sallis, JF. Ciclovía participation and impacts in San Diego, CA: the first CicloSDias. Prev Med. (2014) 69:S66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.005

23. Paez, DC, Reis, RS, Parra, DC, Hoehner, CM, Sarmiento, OL, Barros, M, et al. Bridging the gap between research and practice: an assessment of external validity of community-based physical activity programs in Bogotá, Colombia, and Recife, Brazil. Transl Behav Med. (2015) 5:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0275-y

24. Gomez-Feliciano, L, McCreary, LL, Sadowsky, R, Peterson, S, Hernandez, A, McElmurry, BJ, et al. Active living Logan Square. Am J Prev Med. (2009) 37:S361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.003

25. Lawrence, RS. Diffusion of the U.S. preventive services task force recommendations into practice. J Gen Intern Med. (1990) 5:S99–S103. doi: 10.1007/BF02600852

26. Woolf, SH, DiGuiseppi, CG, Atkins, D, and Kamerow, DB. Developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: lessons learned by the US preventive services task force. Annu Rev Public Health. (1996) 17:511–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.002455

27. Peters, MDJ, Marnie, C, Colquhoun, H, Garritty, CM, Hempel, S, Horsley, T, et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:263. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

28. Tricco, AC, Lillie, E, Zarin, W, O’Brien, KK, Colquhoun, H, Levac, D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

29. Ouzzani, M, Hammady, H, Fedorowicz, Z, and Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

30. Fife, ST, and Gossner, JD. Deductive qualitative analysis: evaluating, expanding, and refining theory. Int J Qual Methods. (2024) 23:1–12. doi: 10.1177/16094069241244856

31. Waltz, TJ, Powell, BJ, Matthieu, MM, Damschroder, LJ, Chinman, MJ, Smith, JL, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0

32. Hong, QN, Pluye, P, Fàbregues, S, Bartlett, G, Boardman, F, Cargo, M, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. (2018).

33. Shea, BJ, Reeves, BC, Wells, G, Thuku, M, Hamel, C, Moran, J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. (2017) 358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008

34. Tyndall, J. AACODS Checklist Flinders University (2010). Available online at: https://fac.flinders.edu.au/dspace/api/core/bitstreams/e94a96eb-0334-4300-8880-c836d4d9a676/content

35. Hipp, JA, Eyler, AA, and Kuhlberg, JA. Target population involvement in urban ciclovias: a preliminary evaluation of St. Louis open streets. J Urban Health. (2012) 90:1010–5. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9759-6

36. Salazar-Collier, CL, Reininger, B, Gowen, R, Rodriguez, A, and Wilkinson, A. Evaluation of event physical activity engagement at an open streets initiative within a Texas-Mexico border town. J Phys Act Health. (2018) 15:605–12. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2017-0112

37. Prada, ETP, Camargo-Lemos, DM, and Férmino, RC. Participation and physical activity in recreovia of Bucaramanga, Colombia. J Phys Act Health. (2021) 18:1277–85. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2021-0047

38. Rubio, MA, Triana, C, King, AC, Rosas, LG, Banchoff, AW, Rubiano, O, et al. Engaging citizen scientists to build healthy park environments in Colombia. Health Promot Int. (2021) 36:223–34. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaa031

39. Cervero, R, Sarmiento, OL, Jacoby, E, Gomez, LF, and Neiman, A. Influences of built environments on walking and cycling: lessons from Bogotá. Int J Sustain Transp. (2009) 3:203–26. doi: 10.1080/15568310802178314

40. Teunissen, T, Sarmiento, O, Zuidgeest, M, and Brussel, M. Mapping equality in access: the case of Bogotá’s sustainable transportation initiatives. Int J Sustain Transp. (2015) 9:457–67. doi: 10.1080/15568318.2013.808388

41. Díaz Del Castillo, A, González, SA, Ríos, AP, Páez, DC, Torres, A, Díaz, MP, et al. Start small, dream big: experiences of physical activity in public spaces in Colombia. Prev Med. (2017) 103:S41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.028

42. Eyler, AA, Hipp, JA, and Lokuta, J. Moving the barricades to physical activity: a qualitative analysis of open streets initiatives across the United States. Am J Health Promot. (2015) 30:e50–8. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.131212-QUAL-633

43. Hipp, JA, Bird, A, Van Bakergem, M, and Yarnall, E. Moving targets: promoting physical activity in public spaces via open streets in the US. Prev Med. (2017) 103:S15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.014

44. Díaz Del Castillo, A, Sarmiento, OL, Reis, RS, and Brownson, RC. Translating evidence to policy: urban interventions and physical activity promotion in Bogotá, Colombia and Curitiba. Brazil Behav Med Pract Policy Res. (2011) 1:350–60. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0038-y

45. Perry, CK, Ko, LK, Hernandez, L, Ortiz, R, and Linde, S. Ciclovia in a rural Latino community: results and lessons learned. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2017) 23:360–3. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000555

46. Montes, F, Jaramillo, AM, Sarmiento, OL, Ríos, AP, García, L, Rubiano, O, et al. Community engagement of a rural community in Ciclovía: progressing from research intervention to community adoption. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1964. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11980-6

47. Rubio, MA, Guevara-Aladino, P, Urbano, M, Cabas, S, Mejia-Arbelaez, C, Rodriguez Espinosa, P, et al. Innovative participatory evaluation methodologies to assess and sustain multilevel impacts of two community-based physical activity programs for women in Colombia. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:771. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13180-2

48. Montes, F, Sarmiento, OL, Zarama, R, Pratt, M, Wang, G, Jacoby, E, et al. Do health benefits outweigh the costs of mass recreational programs? An economic analysis of four Ciclovía programs. J Urban Health. (2012) 89:153–70. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9628-8

49. Shu, S, Batteate, C, Cole, B, Froines, J, and Zhu, Y. Air quality impacts of a CicLAvia event in downtown Los Angeles, CA. Environ Pollut. (2016) 208:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.09.010

50. Parra, D, Gomez, L, Pratt, M, Sarmiento, OL, Mosquera, J, and Triche, E. Policy and built environment changes in Bogotá and their importance in health promotion. Indoor Built Environ. (2007) 16:344–8. doi: 10.1177/1420326X07080462

51. Medina, C, Romero-Martinez, M, Bautista-Arredondo, S, Barquera, S, and Janssen, I. Move on bikes program: a community-based physical activity strategy in Mexico City. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:1685. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101685

52. Gómez, LF, Mosquera, J, Gómez, OL, Parra, DC, Rodríguez, DA, Sarmiento, OL, et al. Social conditions and urban environment associated with participation in the Ciclovia program among adults from Cali, Colombia. Cad Saude Publica. (2015) 31:257–66. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00086814

53. Rodrigues, EQ, Garcia, LMT, Ribeiro, EHC, Barrozo, LV, Bernal, RTI, Andrade, DR, et al. Use of an elevated avenue for leisure-time physical activity by adults from downtown São Paulo, Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5581. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095581

54. De La Peña-de, LA, Amezcua Núñez, JB, and Hernández-Bonilla, A. La promoción de estilos de vida saludable aprovechando los espacios públicos. Horizonte Sanitario. (2017) 16:201–210. doi: 10.19136/hs.a16n3.1878

55. Cohen, D, Han, B, Derose, KP, Williamson, S, Paley, A, and Batteate, C. CicLAvia: evaluation of participation, physical activity and cost of an open streets event in Los Angeles. Prev Med. (2016) 90:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.009

56. Wolf, SA, Grimshaw, VE, Sacks, R, Maguire, T, Matera, C, and Lee, KK. The impact of a temporary recurrent street closure on physical activity in new York City. J Urban Health. (2015) 92:230–41. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9925-0

57. Douglas, G, Agrawal, AW, Currin-Percival, M, Cushing, K, and DeHaan, J. Community benefits and lessons for local engagement in a California open streets event: a mixed-methods assessment of Viva CalleSJ 2018. San José, CA: Mineta Transportation Institute (2019).

58. Parra, DC, Adlakha, D, Pinzon, JD, Van Zandt, A, Brownson, RC, and Gomez, LF. Geographic distribution of the Ciclovia and Recreovia programs by neighborhood SES in Bogotá: how unequal is the geographic access assessed via distance-based measures? J Urban Health. (2021) 98:101–10. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00496-w

59. Triana, CA, Sarmiento, OL, Bravo-Balado, A, González, SA, Bolívar, MA, Lemoine, P, et al. Active streets for children: the case of the Bogotá Ciclovía. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0207791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207791

60. Sarmiento, OL, Rios, AP, Paez, DC, Quijano, K, and Fermino, RC. The Recreovía of Bogotá, a community-based physical activity program to promote physical activity among women: baseline results of the natural experiment Al Ritmo de las Comunidades. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:633. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060633

61. González, SA, Adlakha, D, Cabas, S, Sánchez-Franco, SC, Rubio, MA, Ossa, N, et al. Adaptation of the Recreovía during COVID-19 lockdowns: making physical activity accessible to older adults in Bogotá, Colombia. J Aging Phys Act. (2024) 32:91–106. doi: 10.1123/japa.2022-0236

62. Torres, A, Sarmiento, OL, Stauber, C, and Zarama, R. The ciclovia and cicloruta programs: promising interventions to promote physical activity and social capital in Bogotá, Colombia. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:e23–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301142

63. Slabaugh, D, Németh, J, and Rigolon, A. Open streets for whom?: toward a just livability revolution. J Am Plan Assoc. (2022) 88:253–61. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2021.1955735

64. Alliance for Biking and Walking. The open streets guide. Available online at: https://bikeleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/OpenStreetsGuide.pdf

65. Gómez, LF, Sarmiento, OL, Lucumí, DI, Espinosa, G, Forero, R, and Bauman, A. Prevalence and factors associated with walking and bicycling for transport among young adults in two low-income localities of Bogotá, Colombia. J Phys Act Health. (2005) 2:445–59. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2.4.445

66. Ministerio de Salud de Perú (2015) Criterios técnicos - implementacion de una ciclovía recreativa

67. Rios, A, Paez, D, Pinzón, E, Fermino, R, and Sarmiento, O. Logic model of the Recreovía: a community program to promote physical activity in Bogota. Rev Bras Ativ Fis Saude. (2017) 22:206–11. doi: 10.12820/rbafs.v.22n2p206-211

68. Pérez-Escamilla, R, Vilar-Compte, M, Rhodes, E, Safdie, M, Grajeda, R, Ibarra, L, et al. Implementation of childhood obesity prevention and control policies in the United States and Latin America: lessons for cross-border research and practice. Obes Rev. (2021) 22:e13247. doi: 10.1111/obr.13247

69. Mora, C, McKenzie, T, Gaw, IM, Dean, JM, von Hammerstein, H, Knudson, TA, et al. Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nat Clim Chang. (2022) 12:869–75. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01426-1

70. Rocque, RJ, Beaudoin, C, Ndjaboue, R, Cameron, L, Poirier-Bergeron, L, Poulin-Rheault, RA, et al. Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e046333. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046333

71. Franco Silva, M, Favarão Leão, AL, O'Connor, Á, Hallal, PC, Ding, D, Hinckson, E, et al. Understanding the relationships between physical activity and climate change: an umbrella review. J Phys Act Health. (2024) 21:1263–75. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2024-0284

72. Pérez-Escamilla, R, Lutter, CK, Rabadan-Diehl, C, Rubinstein, A, Calvillo, A, Corvalán, C, et al. Prevention of childhood obesity and food policies in Latin America: from research to practice. Obes Rev. (2017) 18:28–38. doi: 10.1111/obr.12574

73. Meisel, JD, Sarmiento, OL, Montes, F, Martinez, EO, Cepeda, M, Rodríguez, DA, et al. Network analysis of Bogotá's Ciclovía Recreativa, a self-organized multisectorial community program to promote physical activity in a middle-income country. Am J Health Promot. (2014) 28:e127–36. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120912-QUAN-443

74. Wensing, M, and Grol, R. Knowledge translation in health: how implementation science could contribute more. BMC Med. (2019) 17:88. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1322-9

75. Bosch, M, Van Der Weijden, T, Wensing, M, and Grol, R. Tailoring quality improvement interventions to identified barriers: a multiple case analysis. Eval Clin Pract. (2007) 13:161–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00660.x

76. Lovero, KL, Kemp, CG, Wagenaar, BH, Giusto, A, Greene, MC, Powell, BJ, et al. Application of the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) compilation of strategies to health intervention implementation in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2023) 18:56. doi: 10.1186/s13012-023-01310-2

77. The World Bank. Indigenous Latin America in the twenty-first century. Latin America & Caribbean Region; (2023). Available online at: World Bank website. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/lac/brief/indigenous-latin-america-in-the-twenty-first-century-brief-report-page

78. Jaramillo, AM, Montes, F, Sarmiento, OL, Ríos, AP, Rosas, LG, Hunter, RF, et al. Social cohesion emerging from a community-based physical activity program: a temporal network analysis. Netw Sci. (2021) 9:35–48. doi: 10.1017/nws.2020.31

79. Kuhlberg, JA, Hipp, JA, Eyler, A, and Chang, G. Open streets initiatives in the United States: closed to traffic, open to physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 11:1468–74. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0376

80. Barradas, SC, Finck Barboza, C, and Sarmiento, OL. Differences between leisure-time physical activity, health-related quality of life and life satisfaction: Al Ritmo de las Comunidades, a natural experiment from Colombia. Glob Health Promot. (2019) 26:5–14. doi: 10.1177/1757975917703303

81. Sarmiento, O, Torres, A, Jacoby, E, Pratt, M, Schmid, TL, and Stierling, G. The Ciclovía-Recreativa: a mass-recreational program with public health potential. J Phys Act Health. (2010) 7:S163–80. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s163

82. Benavides, J, Rowland, ST, Do, V, Goldsmith, J, and Kioumourtzoglou, MA. Unintended impacts of the open streets program on noise complaints in new York City. Environ Res. (2023) 224:115501. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.115501

83. Zieff, SG, Kim, MS, Wilson, J, and Tierney, P. A “Ciclovia” in San Francisco: characteristics and physical activity behavior of Sunday streets participants. J Phys Act Health. (2014) 11:249–55. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2011-0290

84. Bridges, CN, Prochnow, TM, Wilkins, EC, Porter, KMP, and Meyer, MRU. Examining the implementation of play streets: a systematic review of the Grey literature. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2020) 26:E1–E10. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001015

85. Suminski, RR, Jackson-Short, C, Duckworth, N, Plautz, E, Speakman, K, Landgraf, R, et al. Dover Micro open street events: evaluation results and implications for community-based physical activity programming. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:356. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00356