- 1Département de Microbiologie-Infectiologie et d’Immunologie, Institut de Biologie Intégrative et des Systèmes, Université Laval, Quebec, QC, Canada

- 2National Microbiology Laboratory, Public Health Agency of Canada, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

- 3Food Science Department, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

- 4Advanced Symbolics Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada

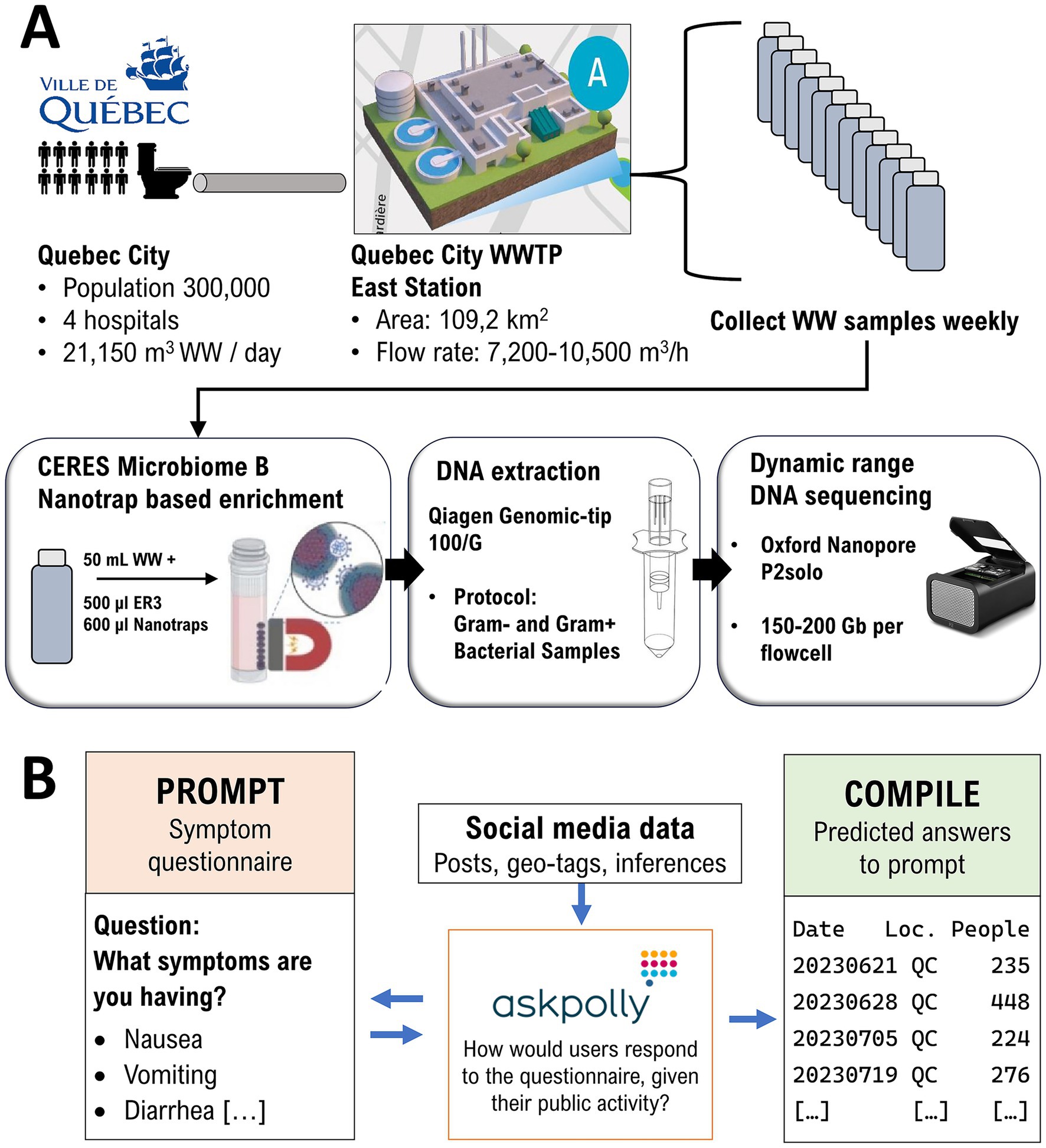

Foodborne enteric infections are a major public health and economical burden, yet their surveillance often relies on latent indicators that delay containment efforts by several days and weeks. Conversely, whole metagenome shotgun sequencing of communal wastewater allows continuous monitoring of enteric pathogens. Spikes in abundance can be observed several weeks before the first case reports emerge. In addition, AI-driven social media mining, already in use for public opinion analytics, could be repurposed for predicting outbreaks at the community level by predicting the number of people experiencing symptoms in the population given their social media activity. Here we report how AI-driven community analytics and high-throughput long-read metagenomic surveillance of communal wastewater microbiota were combined to monitor non-typhoidal salmonellosis in Quebec City, Canada, from August 2023 to February 2024. Both approaches indicated similar fluctuations over time for: (i) people experiencing salmonellosis symptoms, and (ii) Salmonella enterica relative abundance in wastewater, with predicted cases leading metagenomic peaks by a week. Moreover, both approaches detected a maximum around September 13th, 2023, 5 weeks before a Salmonella food recall for the Quebec and Ontario provinces was made by the Public Health Agency of Canada. We therefore suggest that continuous AI-driven analytics and wastewater metagenomics monitoring could become part of a nationwide surveillance pipeline from the community scale to the molecular level.

Introduction

Enteric infections related to foodborne illnesses are a global public health burden, with estimates reaching ~1,5 million annual deaths and 1,020 disability-adjusted life-years per 100,000 population (1), while also costing billions of dollars in healthcare and food recalls (2). Salmonella spp. are estimated to account for causing roughly 155,000 deaths worldwide (3). Pathogen surveillance is therefore critical to prevent and control outbreaks. However, conventional monitoring methods often rely on latent indicators, such as case reports from hospitals and samples from infected individuals to both identify the causative agent and its prevalence. This process requires days, even weeks, before mitigating efforts can be deployed (2). Conversely, whole metagenome shotgun sequencing allows the sampling of all genetic material in a sample (4).

In parallel, several initiatives revealed the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance diagnostics, drug discovery and tailoring treatments based on personal genomics data (5). While useful at the patient level, the use of AI for public health (especially monitoring outbreaks) raises ethical questions. Notably, there are concerns regarding data privacy and the accuracy of predictions made by generative pre-trained transformer models (6). For these reasons, any AI-driven community data mining for predicting outbreaks should remain broad in scope and aimed at a maximal extent at public data. Social media provides such a data pool where public posts, engagements and inferences can be sourced to predict a response at the community level. This approach, already in use for marketing sentiment and response analysis (7) could be repurposed to predict, for instance, the number of cases of an outbreak, given a social media user’s inferred symptom.

If continuously monitored, social media mining could serve conjointly with metagenomic-based surveillance to identify any pathogens matching the outbreak inferred from social media data. We proceeded as such during a two-year metagenomic survey of Quebec City’s wastewater treatment influent. We compiled taxonomic profiles across weekly samples, both, respectively, indicating a surge in abundance for Salmonella enterica and a matching increase in predicted numbers of people experiencing salmonellosis symptoms.

A maximum abundance peak (first detected September 13th, 2023) was ultimately found among a subset of 17 samples collected between from September 2023 to January 2024 for whom AI-driven community analytics data was available and matching Salmonella enterica abundance fluctuations. Furthermore, we could reconstruct a strain-level assembly by re-assembling reads assigned to Salmonella enterica during the Sep 13th 2023 abundance peak. The pre-assembly read selection ultimately increased genome completeness and reduced contamination while also improving taxonomic assignment compared to a simple de novo binned assembly without sub-setting reads. We were also able to match its MLST profile to the one of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, further confirming the presence of virulent non-typhoidal Salmonella in this abundance peak.

Methods

AI-driven community analytics

AskPolly (8) is an AI driven, public opinion research platform, that was used to gather community analytics from X (formerly Twitter), Reddit, Tik Tok, BlueSky, and Mastodon (including Facebook Threads). A simplified schematic flowchart is included in Figure 1. AskPolly starts with an independent panel (9) across Canada. Posts from the individuals in the panel are collected and stored in a lexical and vector data lake. Data retrieval is based on a community level questionnaire, using the format of yes/no questions and possible symptoms a person could be experiencing (see Supplementary material for the full questionnaire). Exclusionary symptoms were also included to distinguish salmonellosis from other foodborne infections with a similar presentation such as botulism, hepatitis, listeriosis and staphylococcosis.

Figure 1. Joint workflow for continuous wastewater metagenome nanopore sequencing (A) and community-based AI-driven inferences (B). WW, Raw wastewater; WWTP, Wastewater treatment plant; P2solo, Oxford Nanopore PromethION 2 solo portable DNA sequences.

This questionnaire was repeated in French and English. All possible posts that could match the questionnaire were retrieved. Stances [32] were assigned by AskPolly to each post as Experiencing or Not Experiencing. Only posts classified as Experiencing were kept. The data was subset to Quebec City using a combination of self-disclosed information, geo-tags and inferences [33]. The output of this workflow is a count of people in Quebec City predicted as “Experiencing” non-typhoidal salmonellosis (Figure 1). AskPolly does not report counts below 100 at any given time to guarantee the anonymity of “Experiencing” social media users.

Wastewater sampling procedure

From September 2023 to January 2024, weekly samples of 63 mL raw sewage water (SW) were collected from the Quebec City Wastewater Treatment East Station, which covers a population of 300,000 including 4 hospitals (Figure 1). Samples were taken directly from the WWTP’s influent intake pool with 100 mL Nalgene bottles strapped on long-handled tongs. Closed bottles were disinfected with Oxivir TB disinfectant spray, then stored in an isothermal cooler box to be transported to the laboratory within 1 h post-sampling. Immediately upon arrival, samples were transferred to a biocontainment level 2 cabinet, where total bacterial biomass was enriched by treatment with 600 μL NanoTrap Microbiome B magnetic beads per 50 mL SW (Ceres Nanosciences, Inc.).

DNA extraction and quantification

Genomic DNA was extracted from cell pellets using the QIAGEN Genomic Tip 100/G kit with the manufacturer’s recommended protocol for Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. DNA extracts were then size selected with the PacBio Short Read Eliminator XS (SREXS) magnetic beads, which completely excludes fragments below 5 kb to favor sequencing longer fragments. Size distribution was assessed before and after SREXS treatments with the FemtoPulse automated PFGE platform (Agilent Technologies). Final processed extracts were quantified with the Qubit dsDNA BR method (Thermo Fisher).

Oxford nanopore long read sequencing

Throughout the monitoring timeline, samples were sequenced using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)‘s PromethION 2 solo platform. Briefly, 1 μg input DNA was processed with the Ligation Sequencing Kit v14 (SQK-LSK114) as recommended by the manufacturer’s protocol with a few minor adjustments (see Supplementary material). Prepared libraries were then sequenced on FLO-PRO002 (P2solo) and basecalled in real-time with MinKNOW v22.04, ONT’s proprietary firmware for sequencing. Base calling was performed using a minimum read length of 300 nt and a minimum Phred score of Q9.

Taxonomic assignment and baseline monitoring

Reads from the SENTINEL time points were classified with Kraken2 v2.1.2 (10), using the pre-built NCBI Nucleotide k-mer index (761 GB, version 2023-05-22) built by Langmead et al. (https://benlangmead.github.io/aws-indexes/k2). Kraken2 reports were concatenated with the addition of a sample name column for further analysis with R (11) and RStudio (12).

By default, Kraken2 reports percent abundances by the total number of reads per time point. By doing so, reads that could not be classified due to poor quality or length remain included in the calculation. To circumvent this issue, which is more prevalent with Nanopore sequencing given its higher error rate relative to short read technologies (13), percent abundances were recalculated over reads that could be classified minimally to the domain level. We postulate that reads of sufficient quality should at least be recognizable as belonging to the known tree of life.

In addition, Kraken2 does not consider abundance cutoffs to report taxa, meaning that one spurious taxon from one single read could be reported. To avoid considering false positives, every count below 100 reads was discarded. As a further sanity check, the abundances should fluctuate over the time series, i.e., taxa should not appear and disappear completely. Therefore, taxa that were reported in less than 75% of the data points were discarded.

De novo metagenome assembly

Nanopore reads from the SW2023-09-13 sample were quality filtered with chopper v0.7.01 with minimum Phred score of 12 and minimum read length of 4,000 bp. Then, sequencing adapters were trimmed with PoreChop-ABI v0.5.0 (14). Pre-processed reads were then assembled de novo with Flye v2.9.5 (15) with the “—meta” flag to account for uneven contig coverage given the metagenomic nature of the sample. Finally, the draft assembly was polished with Medaka v2.0.12 using pre-processed reads as input bases.

Reference-guided genome reconstruction

If a known pathogen is present at sufficiently high levels in a SW sample, then it should be possible to reconstruct its genome sequence, or an approximate consensus of it, using a reference-guided assembly. We therefore pre-selected reads that were identified by Kraken2 as belonging to the same species. Then, only those reads were used for assembly. Briefly, seqtk3 was used to subset reads, in conjunction with grep over the Kraken2 reports to extract the list of read IDs. Then, those reads were aligned to a reference using minimap v2.28 (16) using profile “map-ont.” RefSeq genome accession GCF_000006945.2 was used for nontyphoid Salmonella enterica, respectively. After alignment, a draft consensus sequence was generated with racon v1.5.0 (17). A final polishing step was done with medaka v1.11.3 (see text footnote 2, respectively) to correct errors intrinsic to Nanopore sequencing. The resulting sequences were evaluated with CheckM v1.2.2 (18) to assess genome completeness in comparison with the reference used. Genome maps were produced with the ProkSee web annotation server (19). Classical MLST analysis was performed on reconstructed genomes along with the reference genome with PyMLST v2.1.6 (20) using the “claMLST command” and the PubMLST dataset for Salmonella enterica.4

Results and discussion

Taxonomic assignment and baseline monitoring

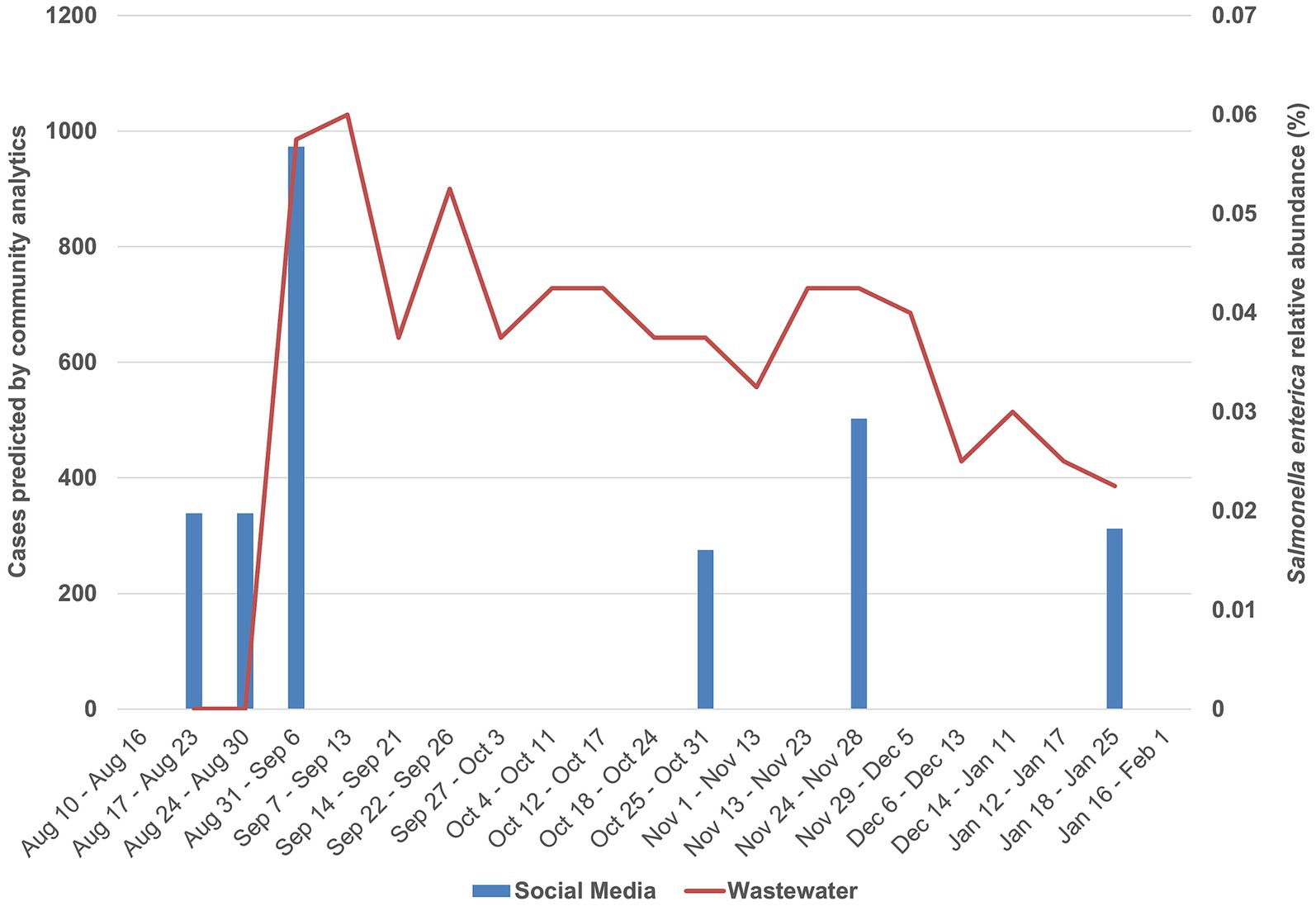

From September 2023 to January 2024, 2,796 species were assigned to metagenomic reads throughout the time series (Supplementary Table 1). From those, S. enterica accounted for 0.03–0.04% of all classified reads (95% confidence interval, N = 18), making it 245th among detected species. Interestingly, this species reached a maximum abundance peak on September 13th, 2023, significantly above the upper confidence limit (0.05% respectively), indicating a surge in bacterial load above baseline fluctuations (Supplementary Figure 1). This peak, at the summer–fall transition, coincides with a surge in predicted counts of people experiencing symptoms reported by AskPolly (Figure 2), while also being in agreement with previous studies that reported a higher incidence of Salmonella cases in the food production chain during this period (21).

Figure 2. AI-driven community analytics for Salmonella symptoms overlap with metagenomic tracking of Salmonella enterica. Blue bars indicate community analytics with number of people reporting symptoms on the left axis. Missing blue bars are points below 100, which were considered too few to guarantee “Experiencing” social media users’ anonymity and were not reported by AskPolly. These can be interpreted as “less than 100”. The red line indicates wastewater pathogen measurement (expressed as percentage of all sample read counts), with relative abundance on the right axis.

Of special interest, concerning Salmonella, the maximum abundance peak also coincides with two public health notices emitted by Canada’s health regulatory agency, which, respectively, reported surges of salmonellosis linked to cantaloupes, raw pet food and cattle in six provinces, including Quebec where this study took place (22, 23). Both notices were first emitted in October 2023, 1 month after the detected abundance peak. This indicates not only the concordance with clinical/epidemiological observations but also reinforces metagenomic monitoring and AI-driven community analytics as an early indicator of potential outbreaks.

The intrinsic design of ONT sequencing technology makes it more vulnerable to nucleotide mismatches and homopolymer indels, which may influence Kraken2’s ability to classify reads, as it does rely on exact k-mer matching. Nevertheless, the use of R10.4.1 flow cells with SQK-LSK114 chemistry helps bring reads to a median Phred score of Q15 (~3% per-nucleotide error rate) instead of the Q9-10 (~10–15% error rate) previously obtained with R9.4.1 flow cells with SQK-LSK109 chemistry. The longer reads (300 bp to several kbp) also help increase the number of k-mer matches with respect to 150–300 bp Illumina reads.

AI-driven community analytics

Community data was collected from Salmonella symptoms across Canada from August 2023 through January 2024. The Salmonella questionnaire was run in both English and French. People reporting having symptoms in Quebec City are reported compared to the wastewater data from the same period (Figure 2). Community-reported symptoms consistently led the wastewater peaks by a week, suggesting that community data is a leading indicator of outbreaks, maybe even more so than metagenomic-based monitoring.

Nonetheless, the output of the symptom questionnaire is by any means insufficient per se for appropriate identification of a pathogen causing an outbreak, which is why we consider these approaches as complementary: AI to detect potential outbreaks; metagenomics to identify potential causative agents. It can also put public health stakeholders on alert by triggering them to increase their monitoring effort. The advantage of both social media data and wastewater metagenomic data is that both can be monitored and archived continuously, with further analysis in the event of an outbreak.

Whole metagenome shotgun assembly

Read-based metagenomic surveillance helped track S. enterica at the species level. However, non-virulent conspecific strains could also contribute to the abundance peak, given the variable accuracy of read classifiers at the species level (24). Kraken2 is particularly affected by Nanopore sequence error rates as its algorithm performs exact k-mer matches to classify sequences (10). Therefore, we attempted to de novo assemble the whole metagenome shotgun sequence for the 2023-09-13 sample to further increase taxonomic resolution. Given enough sequencing depth, metagenome-assembled genomes can be reconstructed (25, 26). For instance, MaxBin and MetaBAT2 regroup contigs having similar G-C content, depth of coverage, and tetranucleotide usage statistics, assuming that contigs should share these properties if belonging to the same source organism (25, 26). However, difficulties arise when co-occurring organisms share these properties, or when the organism of interest is in low abundance among a large set of reads (27).

As expected, this assembly did not recover any contigs classified as S. enterica, even though Flye was run with the –meta flag to allow for uneven coverage across contigs (15). This could be attributable to the very low abundance of those enteric pathogens within the sample (less than 0.5% of all reads). Indeed, reads from the SW2023-09-13 sample revealed that it was largely populated by bacteria (75% of all read counts), among which Pseudomonadota, the phylum comprising S. enterica., accounted for 43% of all bacterial reads (Supplementary Figure 2). The Enterobacteriaceae family represented 5% of all Pseudomonadota within this sample (Supplementary Figure 2). S. enterica reads, regardless of strains, accounted for 1%, respectively, of all Enterobacteriaceae reads (Supplementary Figure 2), thereby illustrating a case where most of the dataset does not represent the genomic target of interest.

We then proceeded to assemble only reads that were assigned as S. enterica using the same de novo assembly approach. This approach seemed viable as there were 10,574 reads (87,590,049 bp) assigned to S. enterica. This subassembly would have had an expected coverage of 17.5x coverage assuming 5 Mb genome size. However, this subassembly was suboptimal for both species. The S. enterica subassembly yielded 166 contigs totalling 3,72 Mbp with 9x coverage (less than the expected genome size of 5 Mb for S. enterica). Given that SW2023-09-13 was the time point linked with an abundance peak for the whole time series, we do not expect de novo subassemblies to perform better on other samples. In addition, human (host) reads accounted for 1.56% of total counts in metagenomic reads from the 2023-09-13 abundance peak (6th most abundant). This indicates that the CERES Microbiome B Nanotrap-based microbial enrichment retained some non-target biomass. A possible solution would be to use Oxford Nanopore sequencing in adaptive sampling mode, where an input genome sequence can be provided to reject host DNA reads in real time (and therefore enrich microbial metagenomic reads further).

Instead of using de novo assembly, we attempted to reconstruct genome sequences by reference-guided assembly using the genome of type strain S. enterica subsp. enterica sv. Typhimurium LT2 and reads from the 2023-09-13 abundance peak as input.

Reference-guided genome reconstruction

Given the large size of this read set (125 gigabases) and that S. enterica reads account for 0.04% of all reads (Supplementary Table 2), we obtained an incomplete assembly with abnormal feature counts with respect to their reference (Supplementary Table 3). However, when only considering reads assigned to these species, we obtained 6.5X coverage, enough to re-attempt a reference-based assembly. This assembly was 95% complete (Supplementary Table 3) and agreed with the main characteristics of their respective reference (Supplementary Figure 3).

Furthermore, classical MLST was performed to assess the possibility of typing reference-based assemblies (Supplementary Table 4). In both cases, when all reads from the sample are used to map against the reference, 0/7 MLST loci were identified. In the assembly with S. enterica reads only, 5 loci out of 7 match the profile of type strain S. enterica subsp. enterica strain LT2 (serovar Typhimurium), suggesting high relatedness to other enteropathogenic non-typhoidal strains. We do agree, however, that the degree of representativeness and chimerism in genome reconstruction is a key challenge in metagenomics (28) that can impact the meaningfulness of strain typing on MAGs.

Nevertheless, the final reference-guided assembly had 0.1% contamination and 0% strain heterogeneity (Supplementary Table 3), suggesting this assembly is not a chimeric consensus of various strains. However, closer investigation into the classical MLST profile of S. enterica SW2023-09-13 MAG revealed 2 of 7 alleles identified were unidentifiable. Those could indeed be a consensus of reads from multiple alleles beyond recognition by the used MLST scheme or the result of mis-assembly in those loci. There does exist software for deconvoluting multiallelic profiles (i.e., haplotype phasing), though these are usually designed for polyploid eukaryotic genomes (29). A similar approach, which would phase the resulting consensus assembly, could further allow strain-level inference.

Limitations and perspectives

Even though AI-driven social media analytics and whole metagenome monitoring could be combined as part of a pathogen surveillance workflow, several limitations remained to be addressed for such a program to be deployed at the nationwide level. For instance, this workflow relies heavily on social media data, whereas social media users are not a random sample of the population (30). Even though 90% of Canadians are social media users (31), there is substantial variation in usage by age, gender, socio-economic status and geographical location (8).

Furthermore, social media users do not typically report nominal healthy states, which could lead to some form of survivorship bias in the data used by AskPolly. This is not unlike longitudinal mental health surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic, where people affected by mental health conditions were more likely to self-report in such studies (9). Even though the AskPolly prompt questionnaires include exclusionary symptoms, the capacity to differentiate salmonellosis from other similar questions remains uncertain, as the AskPolly-assigned stances (Experiencing vs. Not experiencing) ultimately depend on how social media users accurately report their symptoms without formal medical knowledge. Finally, the “below 100” anonymity threshold, while preventing user traceback, creates discontinuities in time series that may limit the assessment of common trends between social media analytics and metagenomic monitoring.

Conclusion

In this study, AI-driven community analytics and high-throughput long-read metagenomic surveillance of Quebec City’s wastewater microbiome both indicated similar fluctuations of predicted salmonellosis cases and Salmonella enterica relative abundance in wastewater. Moreover, both approaches detected a maximum on September 13th, 2023, 1 month before a nationwide Salmonella food recall by Canadian health authorities. Binned-read reference-based assembly further confirmed the presence of non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica in the wastewater influent during this period. Moreover, community indicators led the metagenomic peaks by a week. We believe that AI-driven community analytics and wastewater metagenomics monitoring could become part of a nationwide surveillance pipeline for health authorities in the short-medium term. Though promising, several technical and methodogical improvements remain to be achieved to improve both the reliability of AI-driven community analytics and characterization of the causative pathogen to the strain level via metagenomic tracking and genomic reconstruction.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. IK-I: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. BC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. RL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by grants from: Genome Canada’s Genomics Applied Partnership Program (to RL and LG), from Genome Quebec (to RL and KW), and from Ontario Genomics (to LG and KW).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Francis Bellavance and Sara Mountir from Managium for project management, Denis Dufour for technical support at the Quebec wastewater facility treatment plant, Matthew Loose (DeepSeq, University of Liverpool) for training team members and for his support and encouragement in using the Oxford Nanopore dynamic sequencing technology. We also thank Quebec City’s Wastewater Treatment Service for allowing us to take weekly samples as well as Genome Canada and Genome Quebec for funding (to RL and KW). We also wish to thank reviewers for their insightful and constructive review of our manuscript.

Conflict of interest

KW and BC were employed by Advanced Symbolics Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1675080/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Li, T, Qiang, N, Bao, Y, Li, Y, Zhao, S, Chong, KC, et al. Global burden of enteric infections related foodborne diseases, 1990–2021: findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. Sci One Health. (2024) 3:100075. doi: 10.1016/j.soh.2024.100075

2. Buzby, JC, and Roberts, T. The economics of enteric infections: human foodborne disease costs. Gastroenterology. (2009) 136:1851–62. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.074

3. Lamichhane, B, Mawad, AMM, Saleh, M, Kelley, WG, Harrington, PJ, Lovestad, CW, et al. Salmonellosis: an overview of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and innovative approaches to mitigate the antimicrobial resistant infections. Antibiotics. (2024) 13:76. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13010076

4. Joseph, TA, and Pe’er, I. An introduction to whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing studies. Methods Mol Biol. (2021) 2243:107–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1103-6_6

5. Tornimbene, B, Leiva Rioja, ZB, Brownstein, J, Dunn, A, Faye, S, Kong, J, et al. Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence for disease-surveillance purposes. BMC Proc. (2025) 19:7. doi: 10.1186/s12919-025-00320-w

6. Gundogmusler, A, Bayindiroglu, F, and Karakucukoglu, M. Mathematical foundations of hallucination in transformer-based large language models for improvisation. TechRxiv. (2024) 2024:486. doi: 10.36227/techrxiv.171925719.97800486/v1

7. Zachlod, C, Samuel, O, Ochsner, A, and Werthmüller, S. Analytics of social media data – state of characteristics and application. J Bus Res. (2022) 144:1064–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.02.016

8. Schimmele, C, Fonberg, J, and Schellenberg, G. Canadians’ assessments of social media in their lives. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

9. Czeisler, MÉ, Wiley, JF, Czeisler, CA, Rajaratnam, SMW, and Howard, ME. Uncovering survivorship bias in longitudinal mental health surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2021) 30:e45. doi: 10.1017/S204579602100038X

10. Wood, DE, Lu, J, and Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with kraken 2. Genome Biol. (2019) 20:257. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0

11. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2019).

12. RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, Inc. (2016).

13. Zhang, T, Li, H, Jiang, M, Hou, H, Gao, Y, Li, Y, et al. Nanopore sequencing: flourishing in its teenage years. J Genet Genomics. (2024) 51:1361–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2024.09.007

14. Bonenfant, Q, Noé, L, and Touzet, H. Porechop_ABI: discovering unknown adapters in Oxford nanopore technology sequencing reads for downstream trimming. Bioinform Adv. (2023) 3:vbac085. doi: 10.1093/bioadv/vbac085

15. Kolmogorov, M, Yuan, J, Lin, Y, and Pevzner, PA. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol. (2019) 37:540–6. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8

16. Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. (2018) 34:3094–100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191

17. Vaser, R, Sović, I, Nagarajan, N, and Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. (2017) 27:737–46. doi: 10.1101/gr.214270.116

18. Parks, DH, Imelfort, M, Skennerton, CT, Hugenholtz, P, and Tyson, GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. (2015) 25:1043–55. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114

19. Grant, JR, Enns, E, Marinier, E, Mandal, A, Herman, EK, Chen, CY, et al. Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. (2023) 51:W484–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad326

20. Biguenet, A, Bordy, A, Atchon, A, Hocquet, D, and Valot, B. Introduction and benchmarking of pyMLST: open-source software for assessing bacterial clonality using core genome MLST. Microb Genom. (2023) 9:001126. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.001126

21. Flores Monter, YM, Chaves, A, Arellano-Reynoso, B, López-Pérez, AM, Suzán-Azpiri, H, and Suzán, G. Edaphoclimatic seasonal trends and variations of the Salmonella spp. infection in northwestern Mexico. Infect Dis Model. (2021) 6:805–19. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2021.05.002

22. Public Health Agency of Canada. Public health notice: outbreak of Salmonella infections linked to Malichita and Rudy brand cantaloupes. (2023). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/public-health-notices/2023/outbreak-salmonella-infections-malichita-cantaloupes.html (Accessed July 9, 2024).

23. Public Health Agency of Canada. Public health notice: outbreak of extensively drug-resistant Salmonella infections linked to raw pet food and contact with cattle. (2024). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/public-health-notices/2023/outbreak-salmonella-infections-under-investigation.html (Accessed July 9, 2024).

24. Van Uffelen, A, Posadas, A, Roosens, NHC, Marchal, K, De Keersmaecker, SCJ, and Vanneste, K. Benchmarking bacterial taxonomic classification using nanopore metagenomics data of several mock communities. Sci Data. (2024) 11:864. doi: 10.1038/s41597-024-03672-8

25. Wu, Y-W, Simmons, BA, and Singer, SW. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. (2016) 32:605–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv638

26. Kang, DD, Li, F, Kirton, E, Thomas, A, Egan, R, An, H, et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ. (2019) 7:e7359. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7359

27. Vosloo, S, Huo, L, Anderson, CL, Dai, Z, Sevillano, M, and Pinto, A. Evaluating de novo assembly and binning strategies for time series drinking water metagenomes. Microbiol Spectr. 9:e01434–21. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.01434-21

28. Chang, T, Gavelis, GS, Brown, JM, and Stepanauskas, R. Genomic representativeness and chimerism in large collections of SAGs and MAGs of marine prokaryoplankton. Microbiome. (2024) 12:126. doi: 10.1186/s40168-024-01848-3

29. Vences, M, Patmanidis, S, Schmidt, J-C, Matschiner, M, Miralles, A, and Renner, SS. Hapsolutely: a user-friendly tool integrating haplotype phasing, network construction, and haploweb calculation. Bioinformatics Adv. (2024) 4:vbae083. doi: 10.1093/bioadv/vbae083

30. Mai, P. The state of social Media in Canada 2022. Social Media Lab. (2022). Available online at: https://socialmedialab.ca/2022/09/14/survey-finds-canadians-are-spending-less-time-on-social-media-but-tiktok-is-the-exception/ (Accessed October 22, 2025).

31. Denham, B. Trends: social Media in Canada. Environics Research. (2024). Available online at: https://environics.ca/insights/articles/2024-trends-social-media-in-canada/ (Accessed October 22, 2025).

Keywords: metagenomics, artificial intelligence, Salmonella , pathogen surveillance, Oxford nanopore sequencing

Citation: Gauthier J, Mohammadi S, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, Boyle B, Landgraff C, Goodridge L, White K, Chapman B and Levesque RC (2025) Leveraging artificial intelligence community analytics and nanopore metagenomic surveillance to monitor early enteropathogen outbreaks. Front. Public Health. 13:1675080. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1675080

Edited by:

Marc Jean Struelens, Université libre de Bruxelles, BelgiumReviewed by:

E. Ernestina Godoy-Lozano, National Institute of Public Health (Mexico), MexicoCopyright © 2025 Gauthier, Mohammadi, Kukavica-Ibrulj, Boyle, Landgraff, Goodridge, White, Chapman and Levesque. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roger C. Levesque, cmNsZXZlc3FAaWJpcy51bGF2YWwuY2E=; Jeff Gauthier, amVmZi5nYXV0aGllci4xQHVsYXZhbC5jYQ==

Jeff Gauthier

Jeff Gauthier Sima Mohammadi1

Sima Mohammadi1 Irena Kukavica-Ibrulj

Irena Kukavica-Ibrulj Brian Boyle

Brian Boyle Chrystal Landgraff

Chrystal Landgraff Lawrence Goodridge

Lawrence Goodridge Roger C. Levesque

Roger C. Levesque